Land Use and Land Cover Dynamics and Their Association with Fire in Indigenous Territories of Maranhão, Brazil (1985–2023)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Temporal Scope

2.3. Computational Environment, Projections, and Preprocessing

2.4. Fire Recurrence over Stable Vegetation

2.5. Critical Fire Years and Quantification of Burned Areas

2.6. Natural-Vegetation Trajectories and Critical Years of Net Loss

2.7. CO2 Emission Estimates from Deforestation and Fire

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fire Recurrence in Indigenous Territories of Maranhão State (1985–2023)

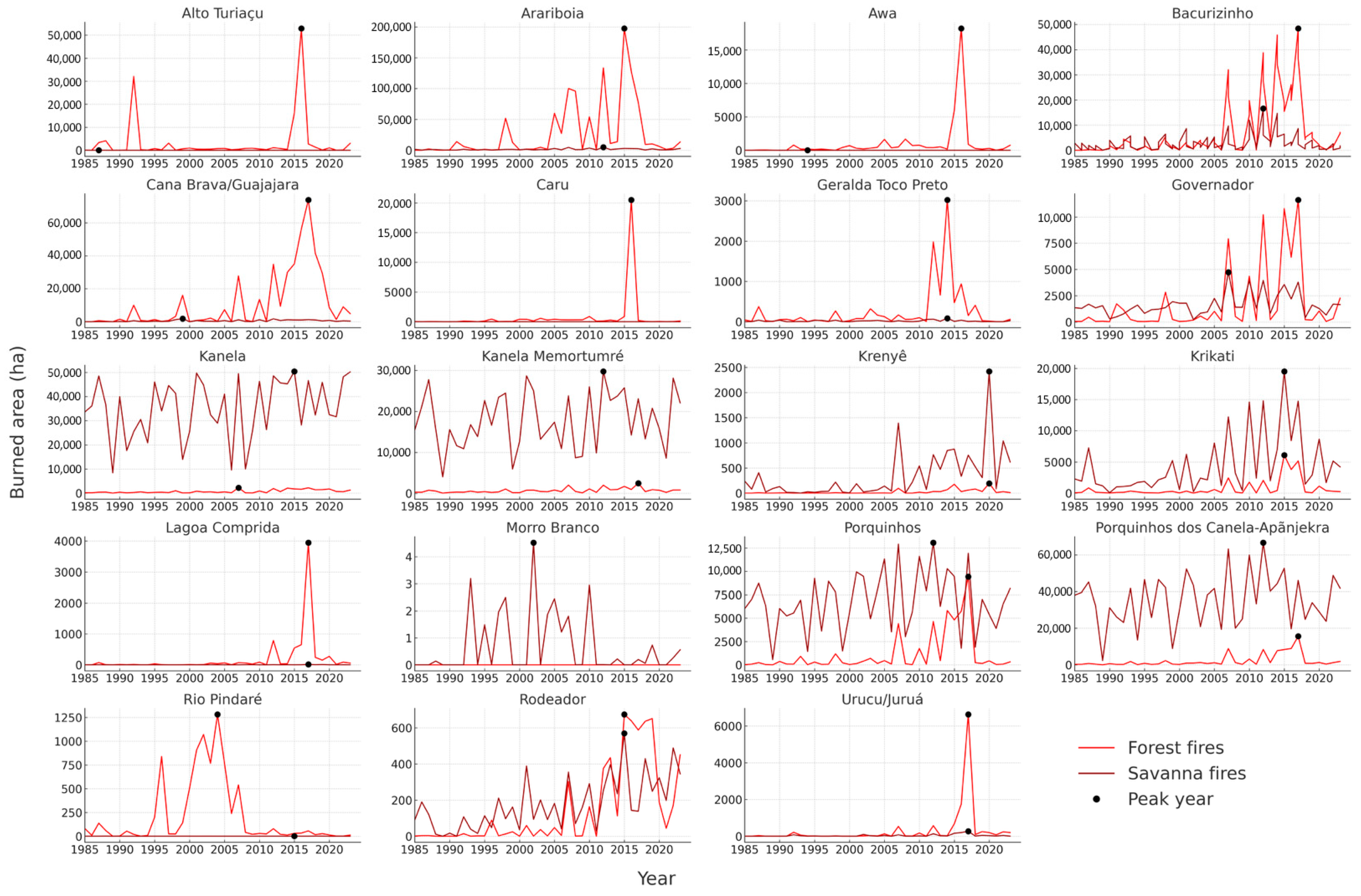

3.2. Mapping of Peak Years of Burned Area in the Indigenous Territories of Maranhão (1985–2023)

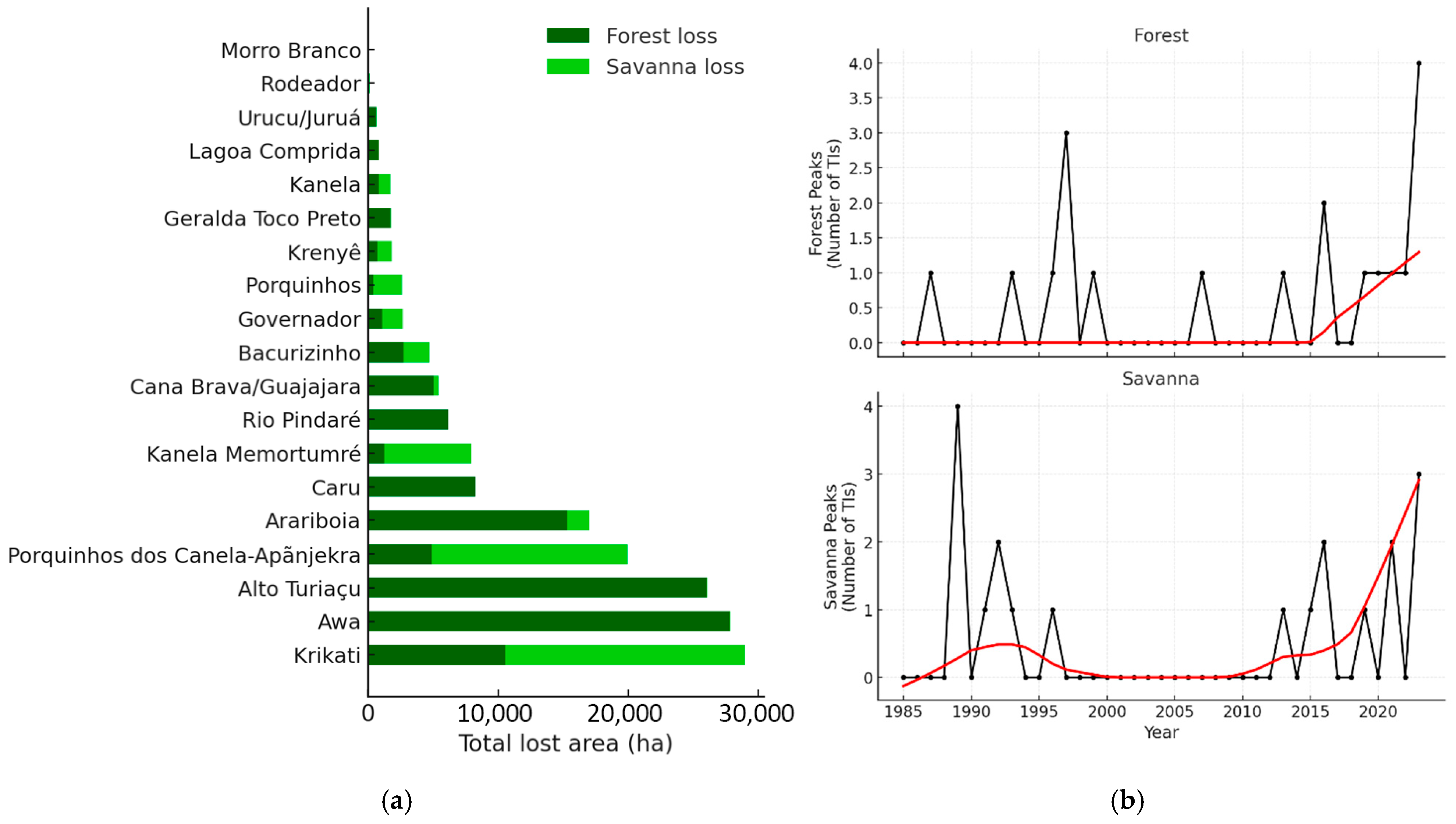

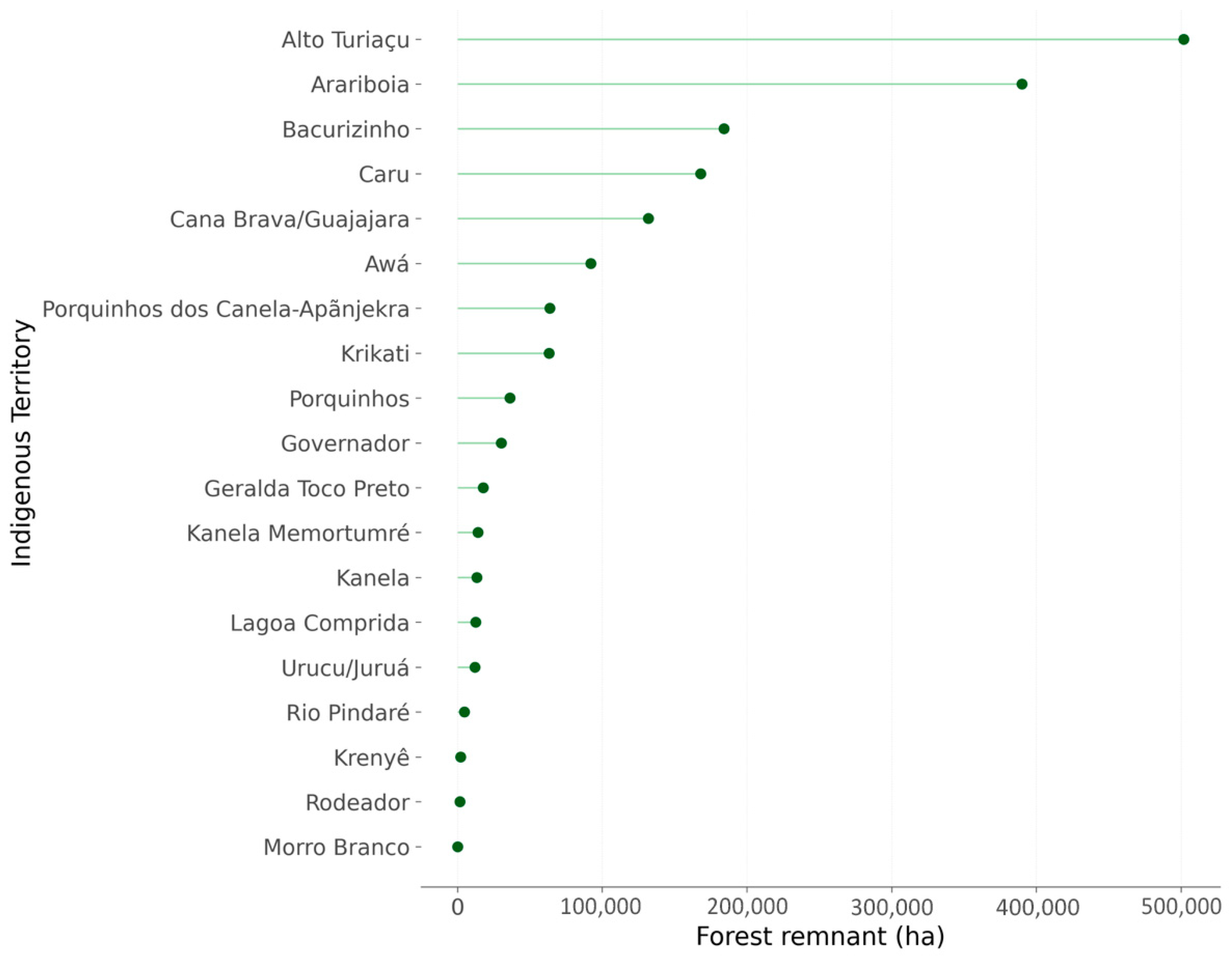

3.3. Vegetation Cover Dynamics in Maranhão and Impacts on Indigenous Territories (1985–2023)

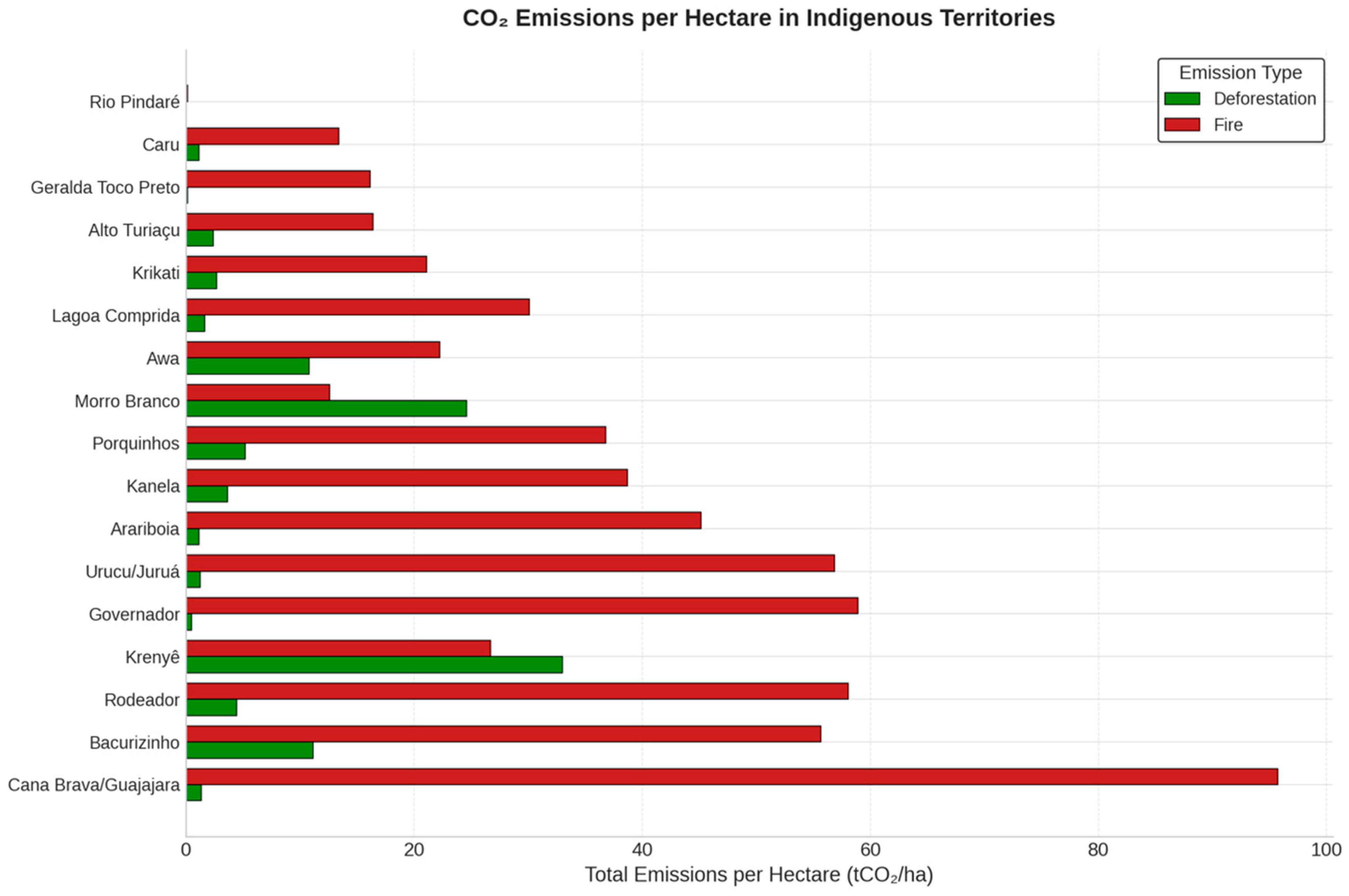

3.4. CO2 Emissions in Indigenous Territories of Maranhão State (2013–2023)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nobre, C.A.; Sampaio, G.; Borma, L.S.; Castilla-Rubio, J.C.; Silva, J.S.; Cardoso, M. Land-use and climate change risks in the Amazon and the need of a novel sustainable development paradigm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10759–10768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.M.C.; Bates, J.M. Biogeographic patterns and conservation in the South American Cerrado: A tropical savanna hotspot. BioScience 2002, 52, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.M.; Roitman, I.; Aide, T.M.; Alencar, A.; Anderson, L.O.; Aragão, L.; Asner, G.P.; Barlow, J.; Berenguer, E.; Chambers, J.; et al. Toward an integrated monitoring framework to assess the effects of tropical savanna and forest degradation and recovery on carbon stocks and biodiversity. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapola, D.M.; Martinelli, L.A.; Peres, C.A.; Ometto, J.P.H.B.; Ferreira, M.E.; Nobre, C.A.; Aguiar, A.P.D.; Bustamante, M.M.C.; Cardoso, M.F.; Costa, M.H.; et al. Pervasive transition of the Brazilian land-use system. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Malhi, Y.; Roman-Cuesta, R.M.; Saatchi, S.; Anderson, L.O.; Shimabukuro, Y.E. Spatial patterns and fire response of recent Amazonian droughts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L07701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.B.; Alvarado, S.T. Variação espaço-temporal da ocorrência do fogo nos biomas brasileiros com base na análise de produtos de sensoriamento remoto. Geografia 2019, 44, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE). Monitoramento do Desmatamento e das Queimadas na Amazônia e no Cerrado; INPE: São José dos Campos, Brasil, 2023. Available online: https://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Instituto Socioambiental (ISA); Fundação Nacional dos Povos Indígenas (FUNAI). Situação Territorial e Extensão Jurídica das Terras Indígenas no Brasil; ISA/FUNAI: Brasília, Brazil, 2025. Available online: https://terrasindigenas.org.br (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Constanino, P.A.L.; Benchimol, M.; Antunes, A.P. Designing Indigenous Lands in Amazonia: Securing indigenous rights and wildlife conservation through hunting management. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.A.P. Property rights, land conflicts and deforestation in the Eastern Amazon. For. Policy Econ. 2008, 10, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conselho Indigenista Missionário (CIMI). Violência contra os Povos Indígenas no Brasil–Dados de 2024; CIMI: Brasília, Brazil, 2025; Available online: https://cimi.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/relatorio-violencia-povos-indigenas-2024-cimi.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Mongabay. Deforestation and Threats to Indigenous Leaders in Maranhão. 2021. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Fellows, M.; Alencar, A.; Bandeira, M.; Castro, I.; Guyot, C. Amazon on Fire: Deforestation and Fire in Indigenous Lands in the Amazon; Technical Note No. 6; Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM): Brasília, Brazil, 2021; Available online: https://ipam.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Amazo%CC%82nia-em-Chamas-6-TIs-na-Amazo%CC%82nia.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Leonel, M. O uso do fogo: o manejo indígena e a piromania da monocultura. Estud. Avanç. 2000, 14, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, N.S.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Anderson, L.O.; Andere, L.; Duarte, V.; Arai, E.; Lima, A. Fire Impact on Diff erent Land Cover Types in the Eastern Part of the Brazilian Legal Amazon. Rev. Bras. Cartogr. 2017, 69, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Marchezini, V. Mudanças na exposição da população à fumaça gerada por incêndios florestais na Amazônia: o que dizem os dados sobre desastres e qualidade do ar? Saúde Debate 2020, 44, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Maranhão—Panorama. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/ma.html (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo Demográfico 2022: População Indígena no Maranhão; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2022. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Feitosa, A.C.; Trovão, J.R. Atlas Escolar do Maranhão: Espaço Geo—Histórico e Cultural; Editora Grafset: João Pessoa, PB, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bandeira, I.C.N. Geodiversidade do Estado do Maranhão; CPRM: Teresina, Brasil, 2013. Available online: https://rigeo.sgb.gov.br/handle/doc/14761 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Spinelli- Araújo, L.; Bayma Siqueira da Silva, G.; Torresan, F.E.; de Castro Victoria, D.; Vicente, L.E.; Bolfe, E.L.; Manzatto, C.V. Conservação da Biodiversidade do Estado do Maranhão: Cenário Atual em Dados Geoespaciais; Embrapa Meio Ambiente: Jaguariúna, Brazil, 2016; Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/1069715/1/SerieDocumentos108Luciana.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Aparecido, L.E.O.; Meneses, K.C.; Lorençone, P.A.; Lorençone, J.A.; Rolim, G.S.; Faria, R.T. Climate Classification by Thornthwaite (1948) Humidity Index in Future Scenarios for Maranhão State, Brazil. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 6352–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, A.C.M.; Anderson, L.O.; Carvalho, N.S.; Campanharo, W.A.; Junior, C.H.L.S.; Rosan, T.M.; Reis, J.B.C.; Pereira, F.R.S.; Assis, M.; Jacon, A.D.; et al. Intercomparison of burned area products and its implication for carbon emission estimations in the Amazon. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Volume 4: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU); IGES: Hayama, Japan, 2006; Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/vol4.html (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Cochrane, M.A.; Alencar, A.; Schulze, M.D.; Souza, C.M.; Nepstad, D.C.; Lefebvre, P.; Davidson, E.A. Positive Feedbacks in the Fire Dynamic of Closed Canopy Tropical Forests. Science 1999, 284, 1832–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane, M.A.; Laurance, W.F. Fire as a large-scale edge effect in Amazonian forests. J. Trop. Ecol. 2002, 18, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Fernandes, H.G.; Sousa Costa, W.; dos Santos Nogueira, F.L.; Vaz Braga, E.; Alves Leão, P.H.; Silva Rodrigues, T.C.; Leite Silva Júnior, C.H. Análise do uso e cobertura da terra e suas relações com o fogo nas terras indígenas do município de Amarante, Maranhão, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2024, 17, 1738–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governo do Estado do Maranhão. Decreto nº 31.186, de 8 de Outubro de 2015: Declara Situação de Emergência em 11 Terras Indígenas Atingidas por Incêndios Florestais; Diário Oficial do Estado do Maranhão: São Luís, Brazil, 2015. Available online: https://pge.ma.gov.br/uploads/pge/docs/DECRETO-N%C2%BA-31.157-DE-01_.10-A-31_.418-DE-18_.12.15.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Conselho Indigenista Missionário (CIMI). Relatório de Violência Contra os Povos Indígenas no Brasil; CIMI: Brasília, Brazil, 2015; Available online: https://cimi.org.br/pub/relatorio/Relatorio-violencia-contra-povos-indigenas_2015-Cimi.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). Indígenas Protestam Exigindo Fim do Incêndio Gigante na Terra Indígena Araribóia (MA); ISA: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015; Available online: https://www.terrasindigenas.org.br/pt-br/noticia/156222 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Instituto de Trabalho Indigenista. Estado de Alerta: Incêndios no MA Afetam Indígenas e Acuam Isolados. Boletim Isolados, 2016. Available online: http://boletimisolados.trabalhoindigenista.org.br (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Organization of American States (OAS). Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). Precautionary Measure MC-754/20—Members of the Guajajara and Awá Indigenous Peoples of the Araribóia Indigenous Land regarding Brazil; OAS/IACHR: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/decisions/mc/2021/res_1-21_mc_754-20_br_en.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Jiménez-Muñoz, J.C.; Mattar, C.; Barichivich, J.; Santamaría-Artigas, A.; Takahashi, K.; Malhi, Y.; Sobrino, J.A.; Schrier, G.v.d. Record-breaking warming and extreme drought in the Amazon rainforest during the course of El Niño 2015–2016. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Anderson, L.O.; Fonseca, M.G.; Rosan, T.M.; Vedovato, L.B.; Wagner, F.H.; Silva, C.V.J.; Silva Junior, C.H.L.; Arai, E.; Aguiar, A.P.; et al. 21st Century drought-related fires counteract the decline of Amazon deforestation carbon emissions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panisset, J.S.; Libonati, R.; Gouveia, C.M.P.; Machado-Silva, F.; França, D.A.; França, J.R.A.; Peres, L.F.; Silva, F. C Contrasting patterns of the extreme drought episodes of 2005, 2010 and 2015 in the Amazon Basin. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Junior, C.H.L.; Anderson, L.O.; Silva, A.L.; Almeida, C.T.; Dalagnol, R.; Pletsch, M.A.J.S.; Penha, T.V.; Paloschi, R.A.; Aragão, L.E.O.C. Fire Responses to the 2010 and 2015/2016 Amazonian Droughts. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, E.; Lennox, G.D.; Ferreira, J.; Malhi, Y.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Barreto, J.R.; Espírito-Santo, F.D.B.; Figueiredo, A.E.S.; França, F.; Gardner, T.A.; et al. Tracking the impacts of El Niño drought and fire in human-modified Amazonian forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2019377118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Maranhense de Estudos Socioeconômicos e Cartográficos (IMESC). Análise dos Focos de Queimadas no Maranhão; IMESC: São Luís, Brazil, 2015. Available online: https://imesc.ma.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2-tri-2016.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Masullo, Y.A.G.; Castro, C.E. Aspectos socioeconômicos e a incidência de queimadas nas terras indígenas do estado do Maranhão. Rev. Geografar 2015, 10, 112–139. Available online: https://revistas.ufpr.br/geografar/article/view/44814/28115 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). Ficha Técnica da Terra Indígena Krenyê; ISA: São Paulo, Brazil, 2023. Available online: https://terrasindigenas.org.br/pt-br/terras-indigenas/5387 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). Fogo Cerca os Awá-Guajá, Mais uma Vez; Boletim Socioambiental; ISA: Brasília, Brazil, 2016; Available online: https://site-antigo.socioambiental.org/pt-br/noticias-socioambientais/fogo-cerca-os-awa-guaja-mais-uma-vez (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE). INPE Registra 30.066 Focos de Queimadas em 2015 no Maranhão. Available online: http://www.inpe.br/noticias/noticia.php?Cod_Noticia=3822 (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Garcia, E. Fogo e Conflito Fundiário em Terras Indígenas do Cerrado; Universidade de Brasília: Brasília, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fundação Nacional dos Povos Indígenas (FUNAI). Despacho nº 549, de 29 de agosto de 2012. Aprova os Estudos de Identificação da Terra Indígena Kanela/Memortumré. Available online: https://acervo.socioambiental.org/acervo/noticias/funai-aprova-identificacao-e-delimitacao-da-terra-indigena-kanela-memortumre-no (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Silva Bezerra, D.; Dias, B.C.C.; Rodrigues, L.H.d.S.; Tomaz, R.B.; Santos, A.L.S.; Silva Junior, C.H.L. Análise dos focos de queimadas e seus impactos no Maranhão durante eventos de estiagem no período de 1998 a 2016. Rev. Bras. Climatol. 2018, 22, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerude, C.E.F.; Pinheiro, A.S.; Lima, J.S. Análise da Distribuição Espacial e Temporal dos Focos de Calor nas Terras Indígenas do Maranhão (2008–2012). In Proceedings of the Anais do XVI Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto, Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, 13–18 April 2013; INPE: São José dos Campos, Brazil, 2013; pp. 7281–7288. Available online: https://dataserver-coids.inpe.br/queimadas/queimadas/Publicacoes-Impacto/material3os/2013_Gerude_Focos_XVISBSR_DE3os.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Celentano, D.; Miranda, M.V.C.; Mendonça, E.N.; Rousseau, G.X.; Muniz, F.H.; Loch, V.D.C.; Varga, I.V.D.; Freitas, L.; Araújo, P.; Narvaes, I.D.S.; et al. Desmatamento, degradação e violência no “Mosaico Gurupi”—A região mais ameaçada da Amazônia. Estud. Avanç. 2018, 32, 315–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, A.A.; Brando, P.M.; Asner, G.P.; Putz, F.E. Landscape fragmentation, severe drought, and the new Amazon forest fire regime. Ecol. Appl. 2015, 25, 1493–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.H.F.; Silva, F.B.; Santos Filho, O.O. Conhecimento indígena, sistema de manejo e mudanças ambientais na região de transição Amazônia–Cerrado. Desenvolv. Meio Ambient. 2022, 59, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros de Castro, E. Os Pronomes Cosmológicos e o Perspectivismo Ameríndio. Mana 1996, 2, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Junior, C.H.L.; Silva, F.B.; Arisi, B.M.; Mataveli, G.; Pessôa, A.C.M.; Carvalho, N.S.; Reis, J.B.C.; Júnior, A.R.S.; Motta, N.A.C.S.; e Silva, P.V.M.; et al. Brazilian Amazon indigenous territories under deforestation pressure. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima. Plano de Ação para a Prevenção e Controle do Desmatamento na Amazônia Legal (PPCDAm): 5ª Fase (2023–2027); Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima: Brasília, Brazil, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mma/pt-br/ppcdam_2023_sumario-rev.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- de Melo, M.H.F. O Nome e a Pele: Nominação e Decoração Corporal Gavião (Amazônia Maranhense). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, São Luís, Brazil, 2017; p. 411. [Google Scholar]

- Nepstad, D.C.; Schwartzman, S.; Bamberger, B.; Santilli, M.; Ray, D.; Schlesinger, P.; Lefebvre, P.; Alencar, A.; Prinz, E.; Fiske, G.; et al. Indigenous lands and protected areas in the Brazilian Amazon: Conserving biodiversity, reducing deforestation, and protecting carbon stocks. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, E.; Ferreira, J.; Gardner, T.A.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; de Camargo, P.B.; Cerri, C.E.; Barlow, J. A large-scale field assessment of carbon stocks in human-modified tropical forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 3713–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, M.V.F.; Silva-Junior, C.H.L.; Anderson, L.O.; Aragão, L.E.O.C. Amazon fires in the 21st century: The year of 2020 in evidence. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 2026–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, G.R.; Randerson, J.T.; Giglio, L.; van Leeuwen, T.T.; Chen, Y.; Rogers, B.M.; Mu, M.; van Marle, M.J.E.; Morton, D.C.; Collatz, G.J.; et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 697–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2019/11/SRCCL-Full-Report-Compiled-191128.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- SEEG Brasil. Sistema de Estimativas de Emissões e Remoções de Gases de Efeito Estufa. 2024. Available online: https://seeg.eco.br (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Pyne, S. The Fires This Time, and Next. Science 2001, 2942, 1005–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.L. Living with Fire: Sustaining Ecosystems & Livelihoods Through Integrated Fire Management; Global Fire Initiative/The Nature Conservancy: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2006; Available online: https://sbfiresafecouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LivingWithFire_Myers_2006-1.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- de Moraes Falleiro, R.; Santana, M.T.; Berni, C.R. As contribuições do manejo integrado do fogo para o controle dos incêndios florestais nas Terras Indígenas do Brasil. Biodivers. Bras. 2016, 6, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indigenous Territory | Burned Area (ha) | 1–3 Burns (%) | 4–9 Burns (%) | ≥10 Burns (%) | Max. Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Araribóia | 293,375 | 66.4% | 28.7% | 4.9% | 32 |

| Porquinhos dos Canela-Apãnjekra | 141,702 | 25.5% | 27.6% | 46.9% | 36 |

| Cana Brava | 94,271 | 47.5% | 44.7% | 7.9% | 27 |

| Kanela | 82,238 | 7.5% | 11.7% | 80.7% | 37 |

| Bacurizinho | 80,196 | 43.7% | 48.1% | 8.2% | 26 |

| Alto Turiaçu | 71,686 | 98.6% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 8 |

| Kanela Memortumré | 64,530 | 16.4% | 31.8% | 51.8% | 36 |

| Porquinhos | 39,201 | 38.0% | 28.6% | 33.4% | 31 |

| Krikati | 38,291 | 71.9% | 23.0% | 5.1% | 28 |

| Governador | 22,688 | 47.1% | 43.4% | 9.5% | 34 |

| Caru | 21,654 | 99.8% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 6 |

| Awá | 17,730 | 99.5% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 6 |

| Urucu/Juruá | 7305 | 91.8% | 8.1% | 0.0% | 11 |

| Geralda Toco Preto | 6179 | 98.3% | 1.6% | 0.1% | 15 |

| Lagoa Comprida | 4718 | 96.9% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 7 |

| Krenyê | 4437 | 73.9% | 25.4% | 0.6% | 13 |

| Rio Pindaré | 1900 | 97.4% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 6 |

| Rodeador | 1779 | 30.0% | 44.3% | 25.7% | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fernandes, H.G.P.; Rodrigues, T.C.S.; Nogueira, F.d.L.d.S.; Melo, M.H.F.d.; Dalagnol, R.; Freire, A.T.G.; Silva-Junior, C.H.L. Land Use and Land Cover Dynamics and Their Association with Fire in Indigenous Territories of Maranhão, Brazil (1985–2023). Land 2026, 15, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010132

Fernandes HGP, Rodrigues TCS, Nogueira FdLdS, Melo MHFd, Dalagnol R, Freire ATG, Silva-Junior CHL. Land Use and Land Cover Dynamics and Their Association with Fire in Indigenous Territories of Maranhão, Brazil (1985–2023). Land. 2026; 15(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010132

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernandes, Helen Giovanna Pereira, Taíssa Caroline Silva Rodrigues, Felipe de Luca dos Santos Nogueira, Maycon Henrique Franzoi de Melo, Ricardo Dalagnol, Ana Talita Galvão Freire, and Celso Henrique Leite Silva-Junior. 2026. "Land Use and Land Cover Dynamics and Their Association with Fire in Indigenous Territories of Maranhão, Brazil (1985–2023)" Land 15, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010132

APA StyleFernandes, H. G. P., Rodrigues, T. C. S., Nogueira, F. d. L. d. S., Melo, M. H. F. d., Dalagnol, R., Freire, A. T. G., & Silva-Junior, C. H. L. (2026). Land Use and Land Cover Dynamics and Their Association with Fire in Indigenous Territories of Maranhão, Brazil (1985–2023). Land, 15(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010132