Does the National Key Ecological Function Zones Policy Promote Leapfrog Development in Urban–Rural Integration?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Policy Background

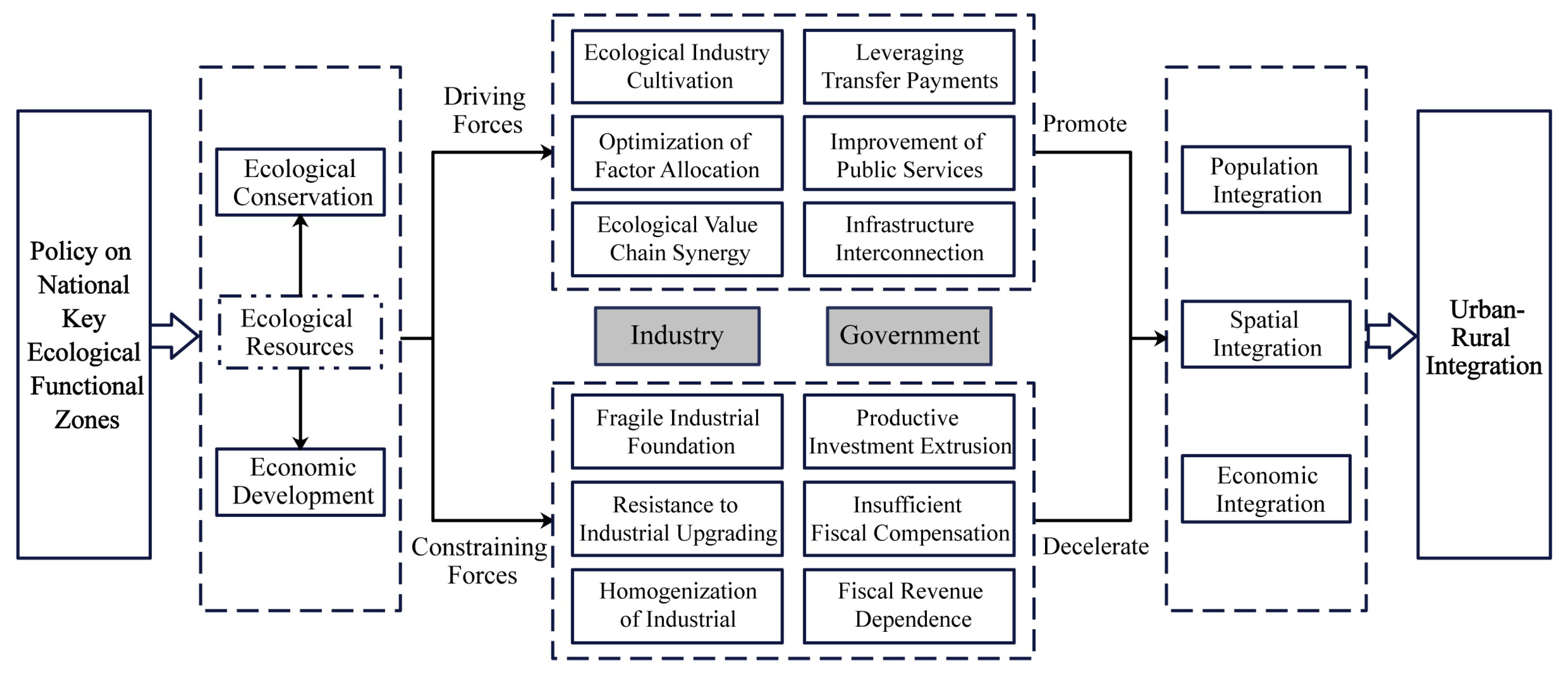

4. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

4.1. The Driving Force of the NKEFZ Policy on Urban–Rural Integration

4.2. The Constraining Force of the NKEFZ Policy on Urban–Rural Integration

5. Research Design, Variables, and Data

5.1. Model Specification

5.2. Variable Selection

5.2.1. Dependent Variable: Level of Urban–Rural Integration Development

5.2.2. Independent Variable

5.2.3. Control Variables

5.2.4. Mechanism Variables

5.2.5. Covariates

5.3. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

6. Empirical Results and Analysis

6.1. Analysis of Baseline Regression Results

6.2. Robustness Checks

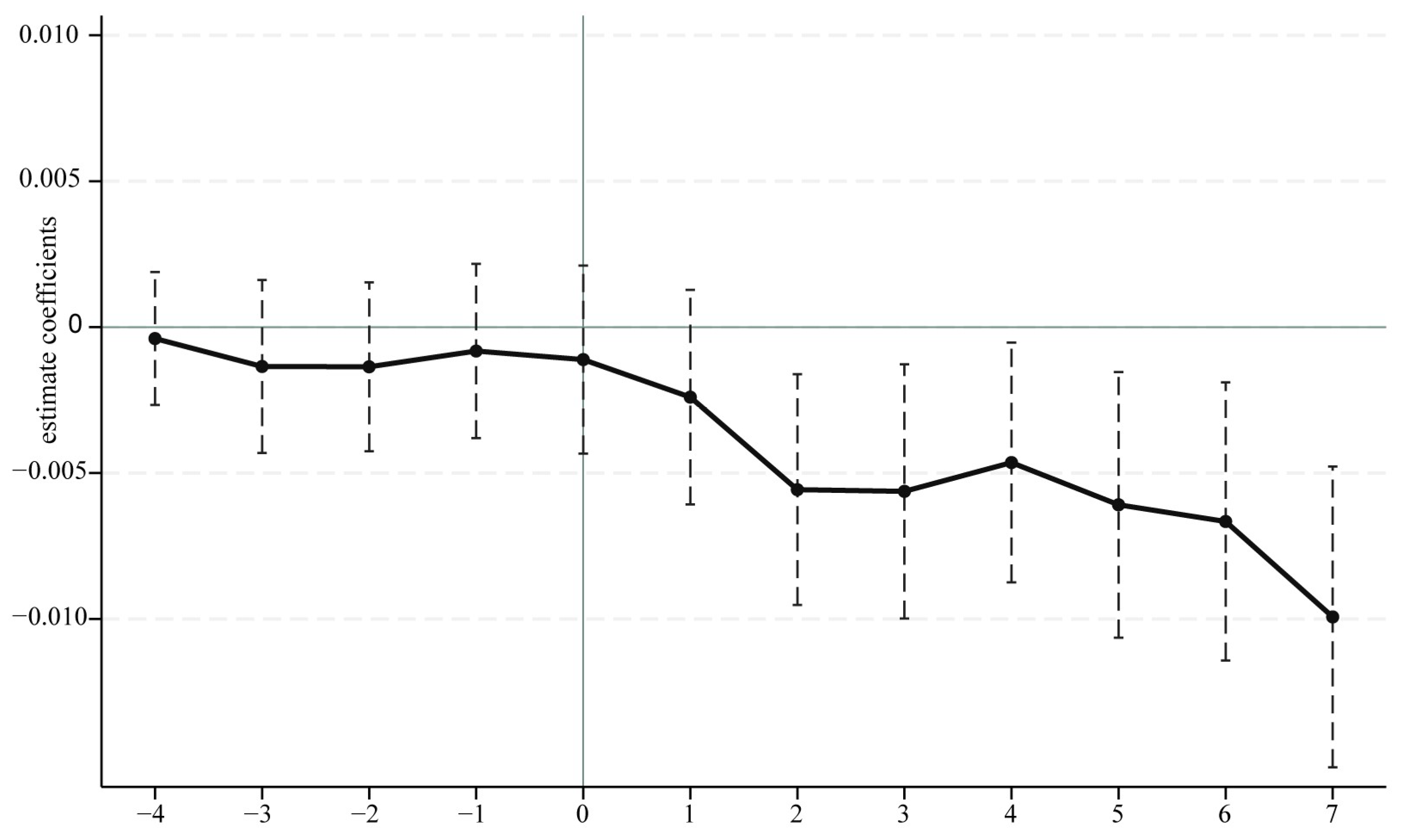

6.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

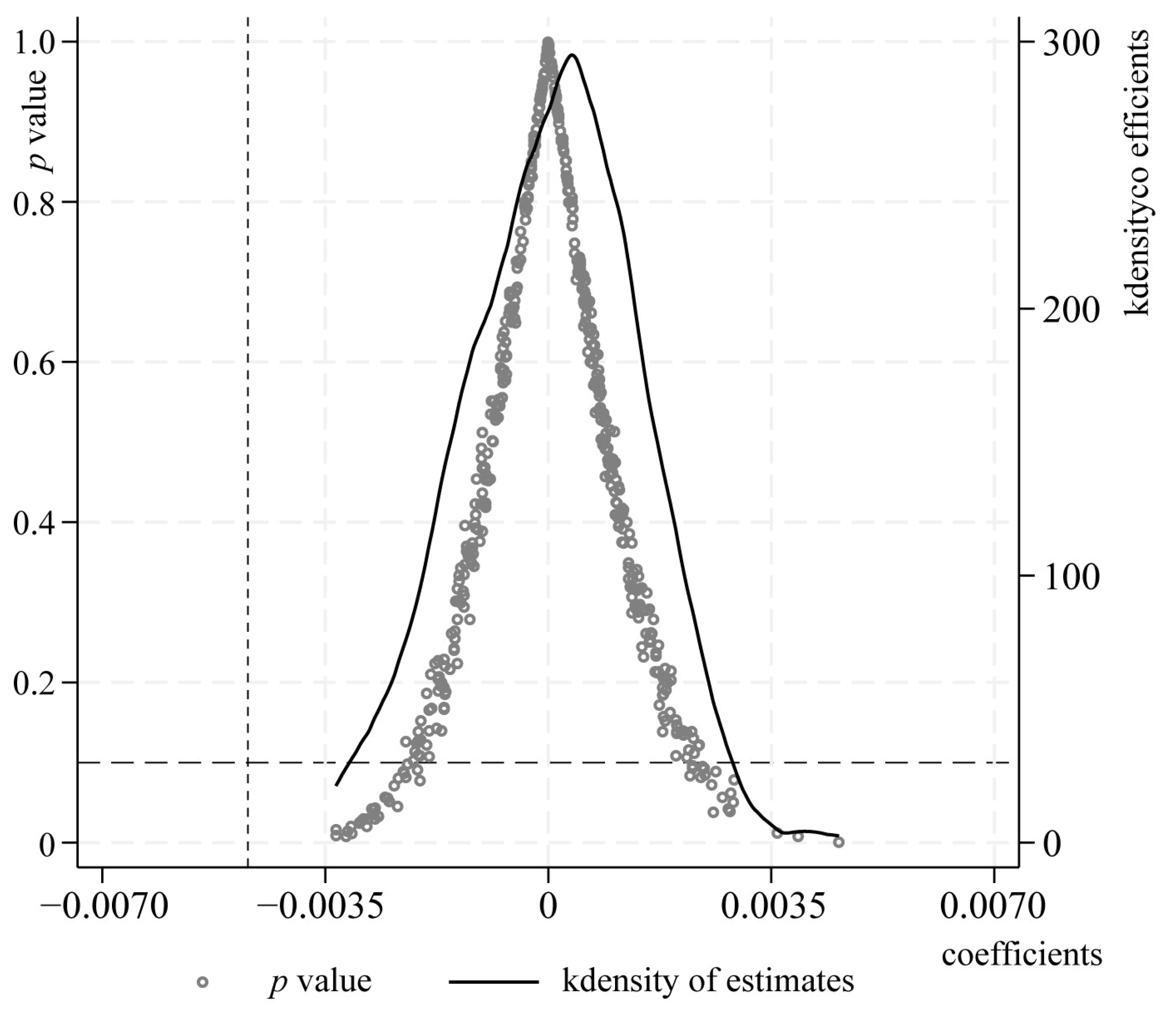

6.2.2. Placebo Test

6.2.3. PSM-DID

6.2.4. Sample Exclusion

6.2.5. Alternative Dependent Variable

6.2.6. Addressing Heterogeneity in Multi-Period Difference-in-Differences (DID)

7. Further Analysis

7.1. Mechanism Analysis

7.1.1. Industrial Structure Upgrading

7.1.2. Government Fiscal Pressure

7.2. Further Analysis: Heterogeneous Effects

7.2.1. Proportion of Key Ecological Function Counties

7.2.2. Regional Location

8. Conclusions, Recommendations, and Discussion

8.1. Research Conclusions

8.2. Policy Recommendations

8.3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Potter, R.B.; Unwin, T. Urban-rural interaction: Physical form and political process in the Third World. Cities 1995, 12, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Ye, C. The integration of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization strategies in China: Origin, reality and future trends. Land 2021, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, J.Q. Value realization mechanism of rural ecological resources: A cross case study based on Linpan in west Sichuan. Issues in agricultural economy. Issues Agric. Econ. 2022, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Wang, G.X. The logical mechanism and breakthrough path for the activation of ecological resources value to promote rural revitalization. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, M. Operational Pattern of Urban-Rural Integration Regulated by Land Use in Metropolitan Fringe of China. Land 2021, 10, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wang, K.; Gan, C.; Ma, X. The Impacts of Tourism Development on Urban–Rural Integration: An Empirical Study Undertaken in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Land 2023, 12, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, L.; Marsden, T. Creating Sustainable Rural Development through Stimulating the Eco-economy: Beyond the Eco-economic Paradox? Sociol. Rural. 2009, 49, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Luo, J.; Tian, L.; Liu, J.; Gan, Y.; Han, T. “Realization–Feedback” Path of Ecological Product Value in Rural Areas from the Perspective of Capital Recycling Theory: A Case Study of Zhengjiabang Village in Changyang County, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Ming, L.; Hai, Y.; Chen, H.; Jize, D.; Luo, J.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Yao, S.; Hou, M. Has the Establishment of National Key Ecological Function Zones Improved Eco-Environmental Quality?—Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment in 130 Counties in Sichuan Province, China. Land 2024, 13, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.Y. Do vertical ecological compensation policies promote green economic development: A case study of the transfer payments policy for China’s National Key Ecological Function Zones. Econ. Syst. 2023, 47, 101125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, G.; Kosov, M.; Ponkratoy, V.; Volkova, M.; Durmanov, A.; Shkalenko, A.; Elyakov, A. The Green Transition Paradox Across Natural Resource-Rich Economies: Evidence from Brazil, Russia, and Uzbekistan. Emerg. Sci. J. 2025, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Ma, B.; Sun, Y.D. Does central ecological transfer payment enhance local environmental performance? Quasi-experimental evidence from China. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 212, 107920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Ke, D.T.; Shao, S.; Liu, Y.; Pan, S.; Xiao, H. The diminishing incentive of ecological fiscal transfer on local government environmental expenditure—Evidence from National Key Ecological Function Zone in China. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 235, 108634. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wu, W.G.; Xiong, L.C.; Wang, F.Y. Is there an environment and economy trade off for the National Key Ecological Function Area policy in China? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 104, 107347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, C.; Xu, C. How Does the National Key Ecological Function Areas Policy Affect High-Quality Economic Development?—Evidence from 243 Cities in China. Land 2025, 14, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Zhuang, G.Y. Has the establishment of National Key Ecological Function Areas promoted economic development?—Evaluation of the policy effects based on a DID study. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, M.Y.; Xi, Z.L.; Zhang, X.; Yao, S.B. Assessing the environmental quality and economic growth of the National Key Ecological Function Areas. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2023, 33, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Sun, Y.D.; Qin, L. Counties’ economic effect of ecological protection policies in China: Evidence from national key ecological function zones. China Environ. Sci. 2022, 42, 5928–5940. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y. China’s urban-rural relationship: Evolution and prospects. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, T. The spatio-temporal patterns of urban–rural development transformation in China since 1990. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.Y.; Wang, S.J.; Xie, S.X.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Qu, Y.B. Spatial path to achieve urban-rural integration development—Analytical framework for coupling the linkage and coordination of urban-rural system functions. Habitat Int. 2023, 142, 102953. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, Y.P.; Fang, C.L. When will China realize urban-rural integration? A case study of 30 provinces in China. Cities 2024, 153, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Legates, R.; Zhao, M.; Fang, C.H. The changing rural-urban divide in China’s megacities. Cities 2018, 81, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.H.; Zhou, G.; Tang, C.L.; Fan, S.G.; Guo, X.S. The spatial organization pattern of urban-rural integration in urban agglomerations in China: An agglomeration-diffusion analysis of the population and firms. Habitat Int. 2019, 87, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Zheng, D. Does the Digital Economy Promote Coordinated Urban–Rural Development? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.G.; Li, Y.J.; Dai, Z.Y.; Lin, Q.R. Study on Impact of Factor Mobility on Urban-Rural Integration Development—Taking the Yangtze River Delta Region as an Example. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2024, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.H.; Li, J. Does Ecological Compensation Help Winning the Tough Battle against Poverty? Quasi-natural Experiment Research Based on Transfer Payment in Key Ecological Function Zone. Financ. Trade Res. 2021, 32, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.Q.; Zhang, G.F.; Ma, X.J.; Yue, Z. Can China’s transfer payment in national key ecological function zones promote green poverty reduction? Quasi-natural experiment evidence from China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 30465–30491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Dai, F.; Shen, W. How China’s Ecological Compensation Policy Improves Farmers’ Income?—A Test of Environmental Effects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6851. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.J.; Zhang, C. Does Ecological Compensation Narrow the Urban-Rural Income Gap?—Empirical Evidence Based on Transfer Payments in National Key Ecological Function Zone of China. Public Financ. Res. 2023, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yao, S.B.; Hou, M.Y.; Weng, F.L. Transfer Payment in National Key Ecological Functional Areas and Supply of Basic Public Services: Empirical Analysis from Counties in China. East China Econ. Manag. 2024, 38, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, L. Research on the Influence of Main Functional Area Policy on Regional Economic Growth Gap. China Soft Sci. 2020, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Jin, L.S. How eco-compensation contribute to poverty reduction: A perspective from different income group of rural households in Guizhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Li, X.H.; Su, S.X.; Guo, Y.Z. Ecological industrialization and rural revitalization for global sustainable development. Geogr. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, B.F.; Zeng, Z.Y.; Xiao, W.H.; Jin, S.T.; Zhao, D.D. The spatial effect of transfer payments for key ecological function zones on the development of ecological industry: A case study of 80 counties in Jiangxi province. J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 2720–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.H.; Zhang, D.X.; Liang, Y.Q.; Ding, J. Value Realization of Ecological Products and Integrated Urban-rural Development: An Empirical Study Based on Urban-rural Integrated Development Pilot Zones. Stat. Res. 2024, 41, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; Luo, X. Urban-rural spatial transformation process and influences from the perspective of land use: A case study of the Pearl River Delta Region. Habitat Int. 2020, 104, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.G.; Zhang, J.H.; Liu, H. Do industrial pollution activities in China respond to ecological fiscal transfers? Evidence from payments to national key ecological function zones. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 1184–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.P.; Long, H.X.; Liu, J.L. Identifying Problematic Areas in the National Key Regions for Ecological Function Based on the Negative List of Industry Access. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 39, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Cheng, N.Y.; Zhang, R.J.; Shen, W.X.; Miao, C.X. Repression or promotion? Transfer payments, ecological constraints, and enterprise development. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 63, 105346. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.H.; Wen, Y.H.; Xie, J.; Liu, H.J. Evolution of Transfer Payment Policy for National Key Ecological Function Areas and Suggestions for Improvement. Environ. Prot. 2020, 48, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Zhu, P.X. Impact mechanism of land resource allocation on integrated urban-rural development. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 2144–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Bao, W.K.; Wang, Y.S.; Liu, Y.S. Measurement of urban-rural integration level and its spatial differentiation in China in the new century. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. The Impact of the Platform Economy on Urban–Rural Integration Development: Evidence from China. Land 2023, 12, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yan, X.L.; Hou, Y.; Lv, B.Y.; Huang, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Han, H.T.; Li, X. Can ecological zoning act as an environmental management tool for protecting regional habitat quality: Causal evidence from the national key ecological function zone in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Bacon, A. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, B.; Sant’anna, P.H.C. Difference-in-Differences with multiple time periods. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T. Mediating Effects and Moderating Effects in Causal Inference. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, L. Research on the impact and path of digital economy on urban-rural integrated development. J. Chongqing Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2025, 31, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.Z.; Zhou, H.M. Study on Influence of Land Resource Allocation on Urban-Rural Integration Development—An Empirical Study on Chengdu-Chongqing Area. Reform Econ. Syst. 2023, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

| Composite Indicator | First-Level Indicator | Second-Level Indicator | Explanation | Unit | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Evaluation Indicators for Urban- Rural Integration | Population Integration | Urbanization Rate | Urban Population/Resident Population | % | + |

| Urban–rural Employment Level | Employed Population in Municipal Districts/Total Employed Population | % | − | ||

| Wage Level | Average Wage of Employed Workers | CNY | + | ||

| Coverage Rate of Social Security for Urban and Rural Residents | Number of Basic Pension Insurance Participants/Resident Population | % | + | ||

| Unemployment Insurance Coverage/Resident Population | % | + | |||

| Population Density | Resident Population/Land Area of Administrative Region | People per Square Kilometer | + | ||

| Spatial Integration | Degree of Product Mobility | Total Road Freight Volume/Total Domestic Road Mileage | Ten Thousand Tons per Kilometer | + | |

| Degree of Information Communication | Telecommunication Revenue/Resident Population | CNY per Capita | + | ||

| Degree of Digitalization | Number of Internet Users/Resident Population | Households per Ten Thousand People | + | ||

| Road Accessibility | Total Domestic Road Mileage/Land Area of Administrative Region | Kilometers per Square Kilometer | + | ||

| Degree of Postal Development | Total Postal Service Revenue/Resident Population | CNY per Capita | + | ||

| Urban Environmental Supply Level | Green Coverage Rate | % | + | ||

| Economic Integration | Per Capita GDP | GDP/Resident Population | CNY per Capita | + | |

| Urban–rural Budget Expenditure Gap | General Budget Expenditure of Municipal Districts/General Budget Expenditure of Administrative Regions | % | − | ||

| Urban–rural Budget Revenue–Expenditure Ratio | General Budget Revenue of Municipal Districts/General Budget Revenue of Administrative Regions | % | − | ||

| Urban–rural Income Gap | Urban Residents’ Disposable Income/Rural Residents’ Disposable Income | - | − | ||

| Urban–rural Tertiary Industry Development | Tertiary Industry Output of Municipal Districts/Tertiary Industry Output of Administrative Regions | % | − | ||

| Per Capita Year-End Savings Balance of Urban and Rural Residents | Year-End Savings Balance of Urban and Rural Residents/Total Population | CNY per Capita | + |

| Variable Categories | Variable Name | Measurement Method | Variable Symbols | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Urban–Rural Integration Development | Entropy Weight Method for Indicator System Calculation | uri | 0.254 | 0.050 | 0.153 | 0.603 |

| Independent Variable | Policy Variable | Whether It Includes Key Ecological Function Zones | did | 0.253 | 0.435 | 0 | 1 |

| Control Variable | Level of Economic Development | Logarithm of GDP | led | 16.417 | 1.028 | 13.160 | 19.973 |

| Economic Vitality | Year-End Total Loans Balance of Financial Institutions/GDP | ev | 1.001 | 0.642 | 0.027 | 12.817 | |

| Scale of Education Expenditure | Education Expenditure/Fiscal Expenditure | see | 0.180 | 0.042 | 0.015 | 0.408 | |

| Scale of Science and Technology Expenditure | Technology Expenditure/Fiscal Expenditure | sste | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0 | 0.178 | |

| Per Capita Fiscal Expenditure | General Budget Expenditure/Resident Population | pcfe | 0.822 | 0.605 | 0.058 | 11.665 | |

| Mechanism Variable | Industrial Structure Upgrading | Tertiary Sector Output/Primary Sector Output | isu | 0.943 | 0.017 | 0.844 | 0.992 |

| Government Fiscal Pressure | (General Budget Expenditure − General Budget Revenue)/GDP | gfp | 0.116 | 0.097 | −0.002 | 0.521 | |

| Covariates | Vegetation Coverage | Statistical Division by Prefecture-Level Cities, Averaging Monthly Data | vc | 0.502 | 0.140 | 0.067 | 0.765 |

| Share of Primary Industry | Primary Sector Output/GDP | spi | 0.129 | 0.083 | 0.002 | 0.499 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| uri | pop | spa | eco | |

| did | −0.005 *** (0.001) | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.006 *** (0.002) | −0.008 *** (0.002) |

| lngdp | 0.012 *** (0.002) | 0.008 ** (0.004) | 0.013 *** (0.003) | 0.016 *** (0.003) |

| act | 0.003 * (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.005 ** (0.002) | 0.000 (0.002) |

| edu | 0.067 *** (0.018) | 0.099 *** (0.029) | 0.052 ** (0.024) | 0.050 ** (0.023) |

| sci | 0.254 *** (0.047) | 0.266 *** (0.081) | 0.268 *** (0.066) | 0.219 *** (0.048) |

| pfis | 0.012 ** (0.005) | 0.013 * (0.008) | 0.005 ** (0.002) | 0.019 *** (0.007) |

| Constant Term | 0.029 (0.034) | 0.016 (0.061) | −0.111 ** (0.044) | 0.253 *** (0.050) |

| Fixed Effects by Region | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Fixed Effects by Year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 5112 | 5112 | 5112 | 5112 |

| R2 | 0.960 | 0.965 | 0.826 | 0.923 |

| Type | PSM-DID | Omitted Samples | Alternative Dependent Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| uri | uri | uri | uri | D | D | |

| did | −0.003 * (0.002) | −0.004 *** (0.001) | −0.004 *** (0.001) | −0.004 *** (0.001) | −0.008 *** (0.002) | −0.007 *** (0.002) |

| Constant Term | 0.246 *** (0.000) | 0.039 (0.038) | 0.248 *** (0.000) | 0.097 *** (0.031) | 0.252 *** (0.001) | −0.038 (0.049) |

| Control Variable | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Fixed Effects by Region | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Fixed Effects by Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 3294 | 3294 | 4482 | 4482 | 5112 | 5112 |

| R2 | 0.947 | 0.954 | 0.951 | 0.958 | 0.872 | 0.885 |

| Type | 2 × 2 Treatment Approach | Proportional Weight | Average Treatment Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Group | Control Group | |||

| A | Treatment Group of the First Policy Implementation Cohort | Treatment Group of the Second Policy Implementation Cohort | 0.056 | −0.004 |

| B | Treatment group of the second policy implementation cohort | Treatment Group of the First Policy Implementation Cohort | 0.089 | 0.003 |

| C | All Cohorts of the Policy Implementation Treatment Groups | Control Group that has never been Exposed to Policy Implementation | 0.855 | −0.007 |

| Type | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| isu | isu | gfp | gfp | |

| did | −0.002 ** (0.001) | −0.001 * (0.001) | 0.020 *** (0.004) | 0.016 *** (0.003) |

| Constant Term | 0.944 *** (0.000) | 1.123 *** (0.034) | 0.111 *** (0.001) | 1.716 *** (0.132) |

| Control Variable | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Fixed Effects by Region | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Fixed Effects by Year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 5112 | 5112 | 5112 | 5112 |

| R2 | 0.864 | 0.875 | 0.881 | 0.936 |

| Type | Proportion of the Number of Key Ecological Function Counties | Geographical Location | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Low Proportion | Medium Proportion | High Proportion | Eastern Region | Central and Western Regions | |

| did | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.009 *** (0.002) | −0.009 *** (0.002) | −0.003 (0.003) | −0.003 *** (0.001) |

| Constant Term | −0.005 (0.037) | 0.052 (0.038) | 0.059 (0.042) | −0.044 (0.075) | 0.024 (0.035) |

| Control Variable | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Fixed Effects by Region | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Fixed Effects by Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 3672 | 3636 | 3636 | 1764 | 3348 |

| R2 | 0.961 | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.970 | 0.950 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, F.; Ma, G.; Zhang, G. Does the National Key Ecological Function Zones Policy Promote Leapfrog Development in Urban–Rural Integration? Land 2026, 15, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010128

Li F, Ma G, Zhang G. Does the National Key Ecological Function Zones Policy Promote Leapfrog Development in Urban–Rural Integration? Land. 2026; 15(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010128

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Fanfan, Guangpeng Ma, and Guixiang Zhang. 2026. "Does the National Key Ecological Function Zones Policy Promote Leapfrog Development in Urban–Rural Integration?" Land 15, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010128

APA StyleLi, F., Ma, G., & Zhang, G. (2026). Does the National Key Ecological Function Zones Policy Promote Leapfrog Development in Urban–Rural Integration? Land, 15(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010128