Nature-Based Accounting for Urban Real Estate: Traditional Architectural Wisdom and Metrics for Sustainability and Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ecological and Urban Theory

2.2. Biodiversity, Mental Health and Urban Real Estate

2.3. Accounting for Biodiversity and Extinction in the Real Estate Industry

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Rationale

3.2. Literature Search and Selection Strategy

3.3. Selection Process and Eligibility Criteria

3.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis Approach

3.5. Classification of the Synthesised Literature

4. Traditional Wisdom for Sustainable Urban Real Estate

4.1. Rationale and Case Selection

4.2. Jiangnan Garden Architecture

4.3. Huizhou Architectural Style

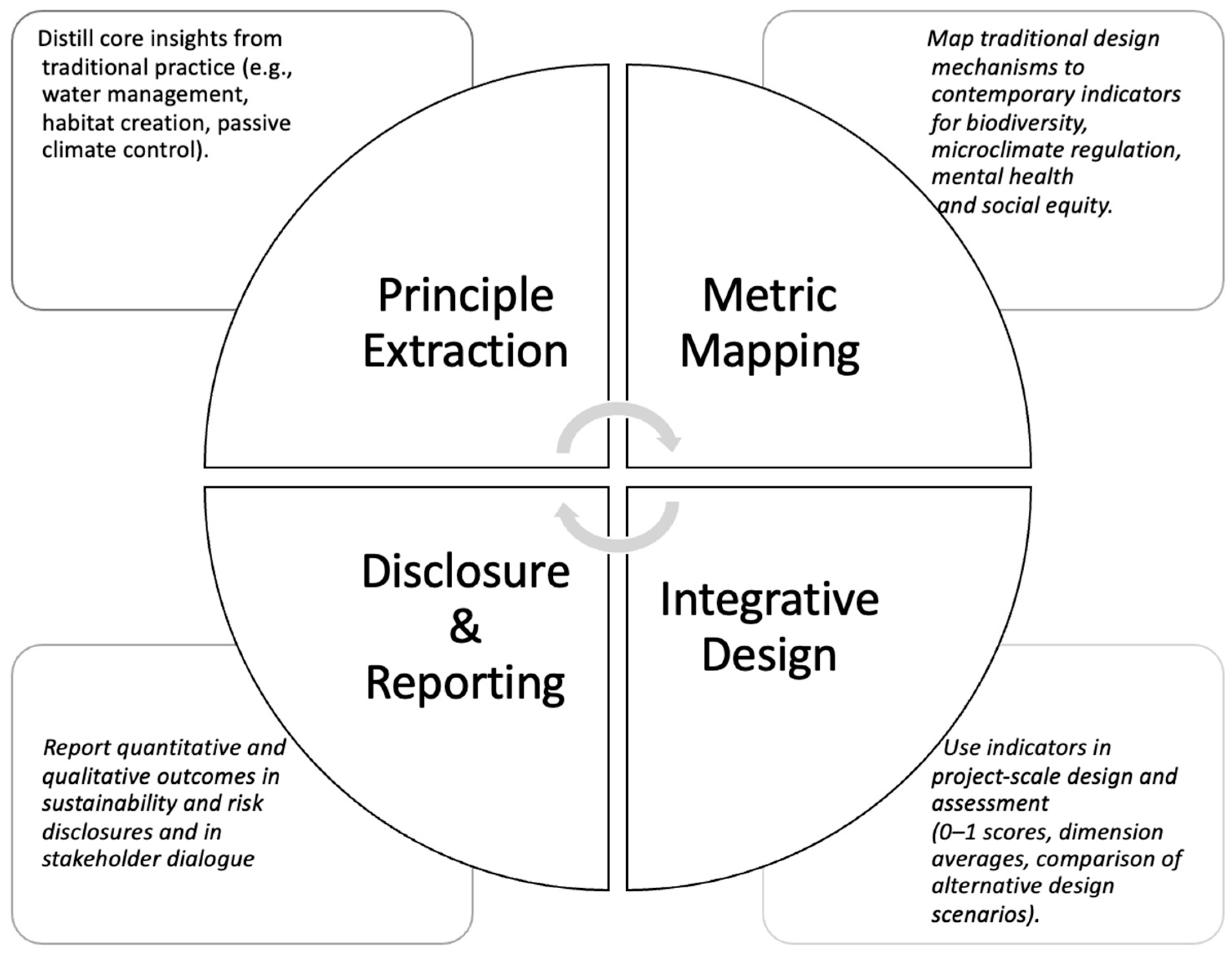

5. Discussion: From Traditional Principles to Project-Scale Nature-Based Accounting

5.1. Conceptual Implications of Jiangnan and Huizhou Traditions

5.2. Comparison with International Natural Capital Metrics and Accounting Frameworks

5.3. Translating Traditional Principles into Contemporary Sustainability Metrics

5.4. A Preliminary Project-Scale Nature-Based Accounting Structure

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Economic Forum (WEF). The Future of Nature and Business: New Nature Economy Report II. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/new-nature-economy-report-ii-the-future-of-nature-and-business/ (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Islam, M.; Yamaguchi, R.; Sugiawan, Y.; Managi, S. Valuing natural capital and ecosystem services: A literature review. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; De Groot, R.; Braat, L.; Kubiszewski, I.; Fioramonti, L.; Sutton, P.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M. Twenty years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Chan, K.M.A.; Garibaldi, L.A.; et al. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 2019, 366, eaax3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kahn, M.E. The greenness of cities: Carbon dioxide emissions and urban development. J. Urban Econ. 2010, 67, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I.; Fischer, L.K.; Kendal, D. Biodiversity conservation and sustainable urban development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.G.; Anderson, S.; Gonzales-Chang, M.; Costanza, R.; Courville, S.; Dalgaard, T.; Dominati, E.; Kubiszewski, I.; Ogilvy, S.; Porfirio, L.; et al. A review of methods, data, and models to assess changes in the value of ecosystem services from land degradation and restoration. Ecol. Model. 2016, 319, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, A. What Caused Dubai Floods? Experts Cite Climate Change, Not Cloud Seeding. Climate & Energy. 2024. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/what-caused-storm-that-brought-dubai-standstill-2024-04-17/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Dahir, A.L. Deadly Rains and Floods Sweep Cities in East Africa. New York Times, 2024. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/25/world/africa/kenya-flooding-rain-tanzania.html (accessed on 4 May 2024).

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Kareiva, P.M.; Daily, G.C. Securing natural capital and expanding equity to rescale civilization. Nature 2012, 486, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartland, L.M. Heat Islands: Understanding and Mitigating Heat in Urban Areas; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- James, P.; Banay, R.F.; Hart, J.E.; Laden, F. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2015, 2, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markevych, I.; Schoierer, J.; Hartig, T.; Chudnovsky, A.; Hystad, P.; Dzhambov, A.M.; de Vries, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Brauer, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Hahn, K.S.; Daily, G.C.; Gross, J.J. Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8567–8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.E.; Lovell, R.; Wheeler, B.W.; Higgins, S.L.; Depledge, M.H.; Norris, K. Biodiversity, cultural pathways, and human health: A framework. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Cities and Biodiversity Outlook: Action and Policy. 2011. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/health/cbo-action-policy-en.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Xie, L.; Bulkeley, H.; Tozer, L. Mainstreaming sustainable innovation: Unlocking the potential of nature-based solutions for climate change and biodiversity. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 132, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Blanco, M.; Costanza, R.; Chen, H.; DeGroot, D.; Jarvis, D.; Kubiszewski, I.; Montoya, J.; Sangha, K.; Stoeckl, N.; Turner, K.; et al. Ecosystem health, ecosystem services, and the well-being of humans and the rest of nature. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 5027–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayer, J.A.; Margules, C.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Sunderland, T.; Langston, J.D.; Reed, J.; Childers, D.L.; McPhearson, T.; Muñoz-Erickson, T.A.; Pacteau, C.; et al. Measuring the effectiveness of landscape approaches to conservation and de-velopment. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). TNFD Issues New Sector Guidance. 2025. Available online: https://tnfd.global/new-set-of-sector-guidance-published/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- McHarg, I.L. Design with Nature; American Museum of Natural History: Garden City, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Fanger, P.O. Calculation of thermal comfort: Introduction of a basic comfort equation. ASHARE Trans. 1967, 73, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.; Berardi, U.; Turnbull, G.; McKaye, R. Microclimate analysis as a design driver of architecture. Climate 2020, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Galaso, J.L.; Ladrón de Guevara López, I.; Boned Purkiss, J. The influence of micro-climate on architectural projects: A bioclimatic analysis of the single-family detached house in Spain’s Mediterranean climate. Energy Effic. 2016, 9, 621–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.; Burch, W.R.; Dalton, S.E.; Foresman, T.W.; Grove, J.M.; Rowntree, R. A conceptual framework for the study of human ecosystems in urban areas. Urban Ecosyst. 1997, 1, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Urban ecology and sustainability: The state-of-the-science and future directions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, J.W. The Gaia hypothesis: Fact, theory, and wishful thinking. Clim. Change 2002, 52, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, J.E. Geophysiology, the science of Gaia. Rev. Geophys. 1989, 27, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.R.; Norton, B.G. Policy implications of Gaian theory. Ecol. Econ. 1992, 6, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolman, A. The metabolism of cities. Sci. Am. 1965, 213, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangeng, Z. Process thinking in the book of changes (Yi Jing). Contemp. Chin. Thought 2008, 39, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S.; Brown, T. Environmental preference: A comparison of four domains of predictors. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; de Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P. Towards a better understanding of the relationship between greenspace and health: Development of a theoretical framework. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 118, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Lin, B.B.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Dean, J.H.; Barber, E.; Fuller, R.A. Toward improved public health outcomes from urban nature. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Xiang, W.N.; Zhao, J. Urban ecology in China: Historical developments and future directions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, I.; White, M.P.; Lovell, R.; Higgins, S.L.; Osborne, N.J.; Husk, K.; Wheeler, B.W. What accounts for ‘England’s green and pleasant land’? A panel data analysis of mental health and land cover types in rural England. Landscape and Urban Planning 2015, 142, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic management: A stakeholder theory. J. Manag. Stud. 1984, 39, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Martin, K.; Parmar, B. Stakeholder capitalism. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K. Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and Planet; John Wiley & Sons: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Imrie, R. Concrete Cities: Why We Need to Build Differently, 1st ed.; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Corburn, J. Urban place and health equity: Critical issues and practices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Schröder, T.; Bekkering, J. Biophilic design in architecture and its contributions to health, well-being, and sustainability: A critical review. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 114–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, M.D.; Galiani, S.; Gertler, P.J.; Martinez, S.; Titiunik, R. Housing, health, and happiness. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2009, 1, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Beer, A.; Lester, L.; Pevalin, D.; Whitehead, C.; Bentley, R. Is housing a health insult? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, G.W.; Wells, N.M.; Moch, A. Housing and mental health: A review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.; Maroun, W. Integrated extinction accounting and accountability: Building an ark. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 750–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.; Maroun, W. The Naturalist’s Journals of Gilbert White: Exploring the roots of accounting for biodiversity and extinction accounting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020, 33, 1835–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauko, T. Innovation in urban real estate: The role of sustainability. Prop. Manag. 2019, 37, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walacik, M.; Renigier-Biłozor, M.; Chmielewska, A.; Janowski, A. Property sustainable value versus highest and best use analyzes. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1755–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, H.; Vardon, M.; Obst, C.; Young, V.; Houghton, R.A.; Mackey, B. Evaluating nature-based solutions for climate mitigation and conservation requires comprehensive carbon accounting. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Agra, R.; Zolyomi, A.; Keith, H.; Nicholson, E.; De Lamo, X.; Portela, R.; Obst, C.; Alam, M.; Honzák, M.; et al. Using the system of environmental-economic accounting ecosystem accounting for policy: A case study on forest ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 152, 103653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viti, M.; Löwe, R.; Sørup, H.J.; Ladenburg, J.; Gebhardt, O.; Iversen, S.; McKnight, U.S.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K. Holistic valuation of Nature-Based Solutions accounting for human perceptions and nature benefits. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 334, 117498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.J. Accounting for biodiversity. Br. Account. Rev. 1996, 28, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.J. Accounting for biodiversity: Operationalising environmental accounting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2003, 16, 762–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.; Hassan, A.; Elamer, A.; Nandy, M. Biodiversity and extinction accounting for sustainable development: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.; Macpherson, M. Extinction Accounting, Finance and Engagement: Implementing a Species Protection Action Plan for the Financial Markets. In Extinction Governance, Finance and Accounting; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2022; pp. 13–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Noronha, C. Assessing the nexus between cross-border infrastructure projects and extinction accounting—From the belt and road initiative perspective. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2023, 43, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, L.; Kopnina, H.; Noronha, C.; Hughes, A.C. Biodiversity conservation, extinction accounting and the metropolis: The case of Hong Kong. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samkin, G.; Schneider, A. Accountability, narrative reporting and legitimation: The case of a New Zealand public benefit entity. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2010, 23, 256–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, J. Mainstreaming biodiversity accounting: Potential implications for a developing economy. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 779–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.J. Accounting for the environment: Towards a theoretical perspective for environmental accounting and reporting. Account. Forum 2010, 34, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.J.; Solomon, J.F. Problematising accounting for biodiversity. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 668–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.; Maroun, W.; Atkins, B.C.; Barone, E. From the Big Five to the Big Four? Exploring extinction accounting for the rhinoceros. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 674–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. GRI 304: Biodiversity. 2016. Available online: https://wapsustainability.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/gri-304-biodiversity.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Global Reporting Initiative. GRI 1: Foundation 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards/gri-standards-english-language/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Global Reporting Initiative. Launch of GRI 101: Biodiversity 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/standards-development/topic-standard-project-for-biodiversity/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Agyekum, K.; Botchway, S.Y.; Adinyira, E.; Opoku, A. Environmental performance indi-cators for assessing sustainability of projects in the Ghanaian construction industry. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2022, 11, 918–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.M.; Dennis, L.Y. A review on the generation, determination and mitigation of urban heat island. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2008, 20, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrovolskienė, N.; Pozniak, A.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Assessment of the sustainability of a real estate project using multi-criteria decision making. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrane, S.J. Impacts of urbanisation on hydrological and water quality dynamics, and urban water management: A review. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2016, 61, 2295–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, P.; Guarnaccia, C.; Tajani, F.; Di Liddo, F.; Anelli, D. An analysis of the noise pollution influence on the housing prices in the central area of the city of Bari. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1603, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaratnam, S.; Nguyen, K.; Selvaranjan, K.; Zhang, G.; Mendis, P.; Aye, L. Designing post COVID-19 buildings: Approaches for achieving healthy buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, A. Biodiversity and the built environment: Implications for the Sustainable Develop-ment Goals (SDGs). Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempeneer, S.; Peeters, M.; Compernolle, T. Bringing the user Back in the building: An analysis of ESG in real estate and a behavioral framework to guide future research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). Discussion Paper on Proposed Sector Disclosure Metrics. 2023. Available online: https://tnfd.global/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Discussion_paper_on_proposed_sector_disclosure_metrics_v1.pdf?v=1702661678 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). Guidance on the Identification and Assessment of Nature-Related Issues: The LEAP Approach (Version 1.1). 2023. Available online: https://tnfd.global/publication/additional-guidance-on-assessment-of-nature-related-issues-the-leap-approach/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). Additional Sector Guidance: Engineering, Construction and Real Estate. 2025. Available online: https://tnfd.global/publication/additional-sector-guidance-engineering-construction-and-real-estate/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Hum. Res. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keswick, M. The Chinese Garden: History, Art, and Architecture; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thorp, R.L. Origins of Chinese architectural style: The earliest plans and building types. Arch. Asian Art 1983, 36, 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, N.S. Chinese architectural history in the twenty-first century. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 2014, 73, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. A Philosophy of Chinese Architecture: Past, Present, Future; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wu, J. Sustainable landscape architecture: Implications of the Chinese philosophy of “unity of man with nature” and beyond. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 24, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, R. The Unity of Man in Ancient Chinese Philosophy. Diogenes 1987, 35, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.I.T. The Tao of Architecture; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. The ancestral hall and ancestor veneration narrative of a Huizhou lineage in Ming–Qing China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 2006–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, S.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Nik, V.M.; Scartezzini, J.L. Climate responsive strategies of traditional dwellings located in an ancient village in hot summer and cold winter region of China. Build. Environ. 2015, 86, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Yan, Y.; Sun, S.; Liu, S. Strategies for improving the micro-climate and thermal comfort of a classical Chinese garden in the hot-summer and cold-winter zone. Energy Build. 2020, 215, 109914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.; Sun, S.; Xu, X.; Higueras, E. Effect of the spatial form of Jiangnan traditional villages on microclimate and human comfort. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Han, D.; Zhang, L.; Duan, Z. The thermal performance of Chinese vernacular skywell dwellings. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Jia, S.; Liu, R. Improvement of Indoor Thermal Environment in Renovated Huizhou Architecture. Int. J. Heat Technol. 2019, 37, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Rademacher, A.M. Toward pluralizing ecology: Finding common ground across sociocultural and scientific perspectives. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.; Simone, A.T.; Anderson, P.; Sharifi, A.; Barau, A.; Hoover, F.A.; Childers, D.L.; McPhearson, T.; Muñoz-Erickson, T.A.; Pacteau, C.; et al. The relational shift in urban ecology: From place and structures to multiple modes of coproduction for positive urban futures. Ambio 2024, 53, 845–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Landscape sustainability science: Ecosystem services and human well-being in changing landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Gou, Z.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Lau, S.K.; Chung, K.H.; Zhang, J. From biophilic design to biophilic urbanism: Stakeholders’ perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, B.L. Green plot ratio: An ecological measure for architecture and urban planning. Land-Scape Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, W.E. How Much Are Nature’s Services Worth? Measuring the social benefits of ecosystem functioning is both controversial and illuminating. Science 1977, 197, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanza, R. Valuing natural capital and ecosystem services toward the goals of efficiency, fairness, and sustainability. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 43, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; De Groot, R.; Sutton, P.; Van der Ploeg, S.; Anderson, S.J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Farber, S.; Turner, R.K. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C. (Ed.) Introduction: What are ecosystem services? In Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Azqueta, D.; Sotelsek, D. Valuing nature: From environmental impacts to natural capital. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.S.; Zhen, L.; Miah, M.G.; Ahamed, T.; Samie, A. Impact of land use change on ecosystem services: A review. Environ. Dev. 2020, 34, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.Y.; Zhang, J.; Masoudi, M.; Alemu, J.B.; Edwards, P.J.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Richards, D.R.; Saunders, J.; Song, X.P.; Wong, L.W. A conceptual framework to untangle the concept of urban ecosystem services. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 200, 103837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. 2019. Available online: https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Turner, R.K.; Paavola, J.; Cooper, P.; Farber, S.; Jessamy, V.; Georgiou, S. Valuing nature: Lessons learned and future research directions. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 46, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shilling, F.; Thorne, J.; Li, F.; Schott, H.; Boynton, R.; Berry, A.M. Fragmentation of China’s landscape by roads and urban areas. Landsc. Ecol. 2010, 25, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, B.W.; Lovell, R.; Higgins, S.L.; White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Osborne, N.J.; Husk, K.; Sabel, C.E.; Depledge, M.H. Beyond greenspace: An ecological study of population general health and indicators of natural environment type and quality. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.; Fuchs, M.; van Ingen, W.; Schoenmaker, D. A resilience approach to corporate biodiversity impact measurement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2567–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lange, Y. Implementing biodiversity reporting: Insights from the case of the largest dairy company in China. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 14, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Atkins, J. Assessing the emancipatory nature of Chinese extinction accounting. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2021, 41, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. System of Environmental-Economic Accounting—Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA). United Nations. 2021. Available online: https://seea.un.org/sites/seea.un.org/files/documents/EA/seea_ea_white_cover_final.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- United Nations. System of Environmental-Economic Accounting 2012—Central Framework; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Urban Nature Indexes. Urban Biodiversity Index (UBI). Available online: https://www.iucnurbannatureindexes.org/en (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Cen, K.; Rao, X.; Mao, Z.; Zheng, X.; Dong, D. A Comparative Study on the Spatial Layout of Hui-Style and Wu-Style Traditional Dwellings and Their Culture Based on Space Syntax. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Luo, X.; Shen, F. Suitable and energy-saving retrofit technology research in traditional wooden houses in Jiangnan, South China. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Nasir, N.B.M. From Chinese Painting to Jiangnan Gardens: Inheritance and Innovation of Artistic Style. J. Educ. Educ. Res. 2024, 8, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y. Heavenly Wells in Ming Dynasty Huizhou Architecture. Orientations 1994, 25, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Tian, H. The regionality of vernacular residences on the Tianjing scale in China’s traditional Jiangnan region. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 2745–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. On the Design of Garden. In A Treatise on the Garden of Jiangnan: A Study on the Art of Chinese Classical Garden; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 59–550. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Mustafa, M.B. A study of ornamental craftsmanship in doors and windows of Hui-style architecture: The Huizhou three carvings (brick, stone, and wood carvings). Buildings 2023, 13, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Li, Z.; Xia, S.; Gao, M.; Ye, M.; Shi, T. Research on the spatial sequence of building facades in Huizhou regional traditional villages. Buildings 2023, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.P. Influence of I-ching (Yijing, or The Book of Changes) on Chinese medicine, philosophy and science. Acupunct. Electro-Ther. Res. 2013, 38, 77–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.S. The ancient city of Suzhou: Town planning in the Sung dynasty. Town Plan. Rev. 1983, 54, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Q. Enlightenments of “white space” in traditional Chinese painting on landscape architecture design. J. Landsc. Res. 2013, 5, 79. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Liu, Z.; Tian, J.; Ma, Q. Urban expansion dynamics and natural habitat loss in China: A multiscale landscape perspective. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 2886–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; He, Y. Environment· Feature·Culture—Inheritance and Innovation of Traditional Regional Architecture in Jiangnan—Take Suzhou Museum as an Example. Acad. J. Archit. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 5, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, X.Y.; Su, Z.Y. Review of Timber Structure Reinforcement Research for the Huizhou Ancient Architecture. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 838, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.Y.; Su, Z.Y. Features and Current Damaged Situation of Hui-Style Architecture. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 838, 2905–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. The Hall of Superabundant Blessings: Toward an Architecture of Chinese Ancestral-Temple Theatre. Asian Theatre J. 2017, 34, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.; Goubran, S. Sustainable real estate: Transitioning beyond cost savings. Bus. Soc. 2020, 360, 141–161. [Google Scholar]

| Metric Category | Metric Subcategory | Indicator/Metric | Description/Measurement Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land/Freshwater/Ocean Use Change | Linear infrastructure fragmentation | Length/footprint/number of new or upgraded linear infrastructure (km, km2, number of lanes, by ecosystem/sensitivity) | Report total length, surface material, location (sensitive/other), traffic, and number/type of wildlife crossings. |

| Land/Freshwater/Ocean Use Change | Wildlife connectivity | Number and structure of wildlife crossing installations per km of linear infrastructure | Include type of crossing, dimension, and verification of wildlife use. |

| Pollution/Removal | Spill events | Volume of pollutant or wastewater spills above regulatory thresholds, by affected ecosystem type and classification | Track and disclose types/quantity, affected ecosystems, and remediation undertaken. |

| Resource Use/Replenishment | Manure and compost use | Input of manure and compost on landscaped areas (tonnes) | Report total input mass linked to real estate/landscaped area. |

| Land Use Change | Green space creation | Amount of green space created (area, type, plant species composition, proportion of native species, connectivity overlap) | Measure area of new green spaces, number/area of trees, share of native species, and overlap with ecological networks. |

| Pollution/Removal | Light pollution | Number, type, and characteristics of outdoor lighting, luminance, area coverage, and dimming practices | Disclose by BUG rating, color temperature, total lumen, and % lights dimmed or on at night. |

| Pollution/Removal | Noise pollution | Noise level measurements (dB, Hz) at significant time periods and across the asset life cycle; incident threshold exceedances | Report baseline, construction, and operational noise, as well as the number of regulatory exceedances/incidents. |

| Invasive Alien Species | Management and remediation | Area (km2) with invasive species present; % area under active management or cleared of invasive species | Quantify and describe management measures and clearance progress. |

| Circular Economy/Materials | Use of recycled and reused materials | Proportion (%) of major inputs/materials that are recycled, reused, or repurposed | Percentages for significant categories by mass/product type and by project phase (build, refurbish, fit-out, etc.). |

| Value Chain/Certification | Environmental product declarations | Share (%) of input materials by credible environmental declaration/certification | Disclose by material type and certificate/label. |

| Water Circularity | Water reuse rate | Total volume of water recycled or reused, metered at the utility level | Report water reuse and recycling in m3 and link to asset or project data. |

| Thematic Domain | Sub-Domain and Research Focus | Representative Sources Cited |

|---|---|---|

| I. Traditional architectural and ecological wisdom | History and principles of Chinese architecture and gardens: analyses of design elements, spatial organisation, and philosophical underpinnings. | [87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] |

| Climate-responsive and passive design: studies on the environmental performance and microclimate regulation of traditional forms (e.g., Huizhou architecture). | [12,25,26,95,96,97,98,99] | |

| II. Foundational ecological and urban theory | Urban ecology and systems thinking: theories on urban areas as ecosystems, “design with nature”, urban metabolism, and the Gaian hypothesis. | [23,27,28,29,30,31,40,100,101,102] |

| Biophilic design and human–nature connection: foundational theories on humanity’s innate connection to nature (biophilia) and its application in urban design. | [39,45,48,103,104] | |

| III. Biodiversity, ecosystems and valuation | Ecosystem services and natural capital: seminal works on the concept and economic valuation of “nature’s services”. | [3,4,5,105,106,107,108,109,110,111] |

| Urban biodiversity and conservation: research on biodiversity within cities and the impact of urbanisation on species and habitats. | [7,79,112,113,114,115,116] | |

| IV. Sustainability accounting and disclosure | Nature-related and biodiversity accounting: development of accounting frameworks to measure and report corporate impacts and dependencies on nature. | [52,53,59,60,61,63,64,66,67,68,69,117,118] |

| Official frameworks and standards: primary documents from global standard-setting bodies that define current disclosure requirements. | [1,17,18,70,71,72,82,83,112,119,120,121] | |

| V. Urban mental health and well-being | Restorative effects of nature: foundational theories (stress reduction, attention restoration) and empirical studies linking green space to psychological well-being. | [13,15,16,35,36,37,38] |

| Socio-ecological systems and health: analyses of links between urban form, social equity, access to green space, and community health outcomes. | [13,16,37,47,49,50,51,78] |

| Feature | Description | Impact on Human–Nature Coexistence |

|---|---|---|

| Site selection and orientation | Siting and orienting buildings in relation to rivers, lakes, canals, prevailing winds and solar exposure to enhance environmental harmony and climatic comfort. | Aligns settlement patterns with local hydrology and climate, reducing energy demand for heating and cooling and embedding habitation within existing landscape structures. |

| Integration of buildings, water and landscape | Residential buildings, gardens, canals, ponds and walkways form a continuous spatial system with frequent interfaces between built edges and water. | Enhances microclimate regulation through evaporative cooling, supports aquatic and riparian habitats, and integrates everyday activities with water-based ecological processes. |

| Courtyards and vegetated spaces | Internal courtyards, gardens and planted edges use trees, shrubs and groundcover to structure space and experience. | Create shaded, ventilated microclimates, provide habitats and food resources for urban biodiversity and offer restorative environments for residents. |

| Water management and storage | Pitched roofs and paved surfaces channel rainwater into internal courtyards, ponds and canals for temporary storage and reuse. | Supports local water cycling, attenuates stormwater peaks and contributes to thermal comfort, while reducing pressure on external supply and drainage infrastructure. |

| Light, views and circulation | Permeable layouts, framed views, bridges and paths maximise visual and physical contact with water and vegetation. | Maintain continuous sensory engagement with nature, supporting mental well-being, place attachment and environmental stewardship. |

| Vegetation composition | Preference for hardy, often indigenous plant species arranged to provide shade, shelter and seasonal variety. | Reinforces local biodiversity, stabilises soils and moderates microclimate, while expressing cultural meanings associated with particular species. |

| Materials and construction | Use of locally available stone, timber and tiles compatible with humid conditions and repeated maintenance. | Limits embodied energy and transport distances, supports local material cycles and contributes to long-term adaptability and repair of the built fabric. |

| Feature | Description | Impact on Human–Nature Coexistence |

|---|---|---|

| Site selection and village layout | Villages and building groups located at the foot of hills and along streams and ponds, with enclosing landforms and planted shelterbelts. | Uses topography and vegetation for wind protection, moisture retention and flood safety; aligns built form with local climatic and hydrological conditions. |

| Landscape integration | Building masses, walls and street networks follow natural contours and frame views of surrounding hills and water bodies. | Minimises earthworks and ecological disturbance, preserves visual and ecological continuity between settlement and landscape and supports habitat connectivity. |

| Courtyards as microclimate systems | Internal courtyards organise rooms and circulation and host planting and small water features. | Provide shaded, ventilated microclimates, support small-scale biodiversity and offer semi-private restorative outdoor spaces. |

| Water channels and ponds | Water channels and ponds are integrated into village and compound layouts for domestic use, irrigation, drainage and fire protection. | Enable local water storage and recycling, moderate humidity and temperature and provide habitats for aquatic species. |

| Materials and construction | Extensive use of local timber, bamboo, stone and lime-based plasters in thick walls and tiled roofs. | Reduces embodied energy and transport impacts, enhances thermal mass and durability and supports local resource economies. |

| Light and ventilation management | Openings, courtyards and skywells (tianjing) calibrated to admit daylight and drive natural ventilation. | Reduces reliance on artificial lighting and mechanical cooling, improves indoor environmental quality and maintains continuous sensory contact with natural cycles. |

| Traditional Feature | Functional Principle | Contemporary Sustainability Metric | Implementation Approach | Reporting & Disclosure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site selection and orientation | Climate adaptation, landscape harmony | Proportion of sites optimized for passive comfort; landscape linkage index | Context-sensitive siting and EIA integration | TNFD/sustainability disclosures |

| Landscape integration | Ecological corridors, visual/functional integration | Green space ratio; length and connectivity of corridors | Designation of ecological/visual corridors | Annual green space and connectivity reporting |

| Courtyard system | Microclimate, biodiversity, social well-being | Courtyard density; species richness index | Courtyard-linked biodiversity monitoring | Operations & biodiversity reporting |

| Water management | Rainwater retention, cooling, habitat | % runoff managed via NBS; water retention ratio | Ponds, rainwater systems, seasonal audits | Water management metrics in reports |

| Vegetation strategy | Native flora, ecosystem resilience | Native species ratio; biodiversity score | Indigenous planting, regular diversity surveys | Planting and biodiversity metrics |

| Sustainable materials | Carbon reduction, local economic support | Local/renewable material ratio; embodied carbon | Local procurement; LCA integration | Materials/carbon reporting |

| Daylighting/ventilation | Passive climate control, comfort, health | Area with passive light/vent; daylight index | Natural ventilation/daylight design, QA | Passive feature impact disclosure |

| Cost–benefit and social inclusion | Economic feasibility; social equity; well-being outcomes for vulnerable groups | Projected lifecycle cost savings (energy, health); share of low-income beneficiaries; accessibility/per capita green space; community engagement index | Prioritization of nature-based solutions in affordable housing; local sourcing; targeted subsidies or incentives; participatory planning | Cost–benefit analysis and inclusion metrics in sustainability, social responsibility, or impact finance reporting |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, R. Nature-Based Accounting for Urban Real Estate: Traditional Architectural Wisdom and Metrics for Sustainability and Well-Being. Land 2026, 15, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010101

Zhang R. Nature-Based Accounting for Urban Real Estate: Traditional Architectural Wisdom and Metrics for Sustainability and Well-Being. Land. 2026; 15(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010101

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ruopiao. 2026. "Nature-Based Accounting for Urban Real Estate: Traditional Architectural Wisdom and Metrics for Sustainability and Well-Being" Land 15, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010101

APA StyleZhang, R. (2026). Nature-Based Accounting for Urban Real Estate: Traditional Architectural Wisdom and Metrics for Sustainability and Well-Being. Land, 15(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010101