Dynamics and Rates of Soil Organic Carbon of Cultivated Land Across the Lower Liaohe River Plain of China over the Past 40 Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. SOC Calculation and Classification Criteria

2.3.2. Ordinary Kriging Interpolation

2.3.3. Calculation and Classification of SOCr

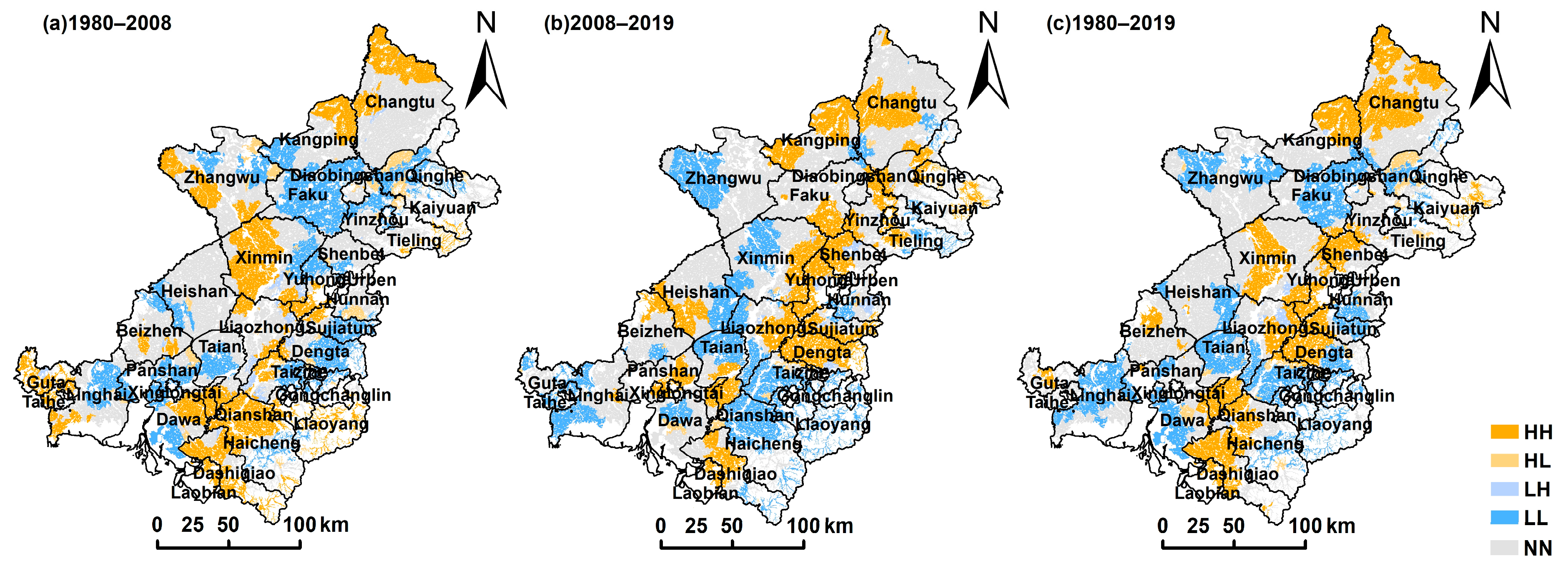

2.3.4. Spatial Autocorrelation

2.3.5. Foundational Data Processing and Mapping

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Cultivated Land SOC Content

3.2. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of SOCr

3.3. Spatiotemporal Correlation Between Initial SOC Content and SOCr

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Cultivated Land SOC

4.2. Correlation Between Initial SOC Content and SOCr

4.3. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gou, N.; Li, B.; Wang, C.; Zhong, W.; Wang, K.; Sun, J. Difference of Soil Nutrient and Organic Carbon Pool Stability of Rice-garlic Rotation in Chengdu Plain. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 55, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillouin, D.; Corbeels, M.; Demenois, J.; Berre, D.; Boyer, A.; Fallot, A.; Feder, F.; Cardinael, R. A global meta-analysis of soil organic carbon in the Anthropocene. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, A.; Dai, T.; Fan, Z.; Luo, Y.; Li, S.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, B.; Tao, Q.; Wang, C.; et al. Depth-dependent soil organic carbon dynamics of croplands across the Chengdu Plain of China from the 1980s to the 2010s. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 4134–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, K.; Lal, R.; Ehlers, K. Soil organic carbon stock as an indicator for monitoring land and soil degradation in relation to United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Owens, P.R.; Libohova, Z.; Miller, D.M.; Wills, S.A.; Nemecek, J. Assessing soil organic carbon stock of Wisconsin, USA and its fate under future land use and climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 667, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; Jones, M.W.; O’Sullivan, M.; Andrew, R.M.; Bakker, D.C.E.; Hauck, J.; Le Quéré, C.; Peters, G.P.; Peters, W.; Pongratz, J.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 1917–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pei, J.; Wang, J. Spatial distribution and relationship between organic matter and pH in the typical black soil region of north-east China. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2019, 36, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y. Spatial-temporal variability of soil organic matter in urban fringe over 30 years: A case study in Northeast China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Rousseau, A.N.; Wang, L.; Yan, B. Spatio-temporal patterns of soil organic carbon and pH in relation to environmental factors—A case study of the Black Soil Region of Northeastern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 245, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, H.; Tian, H.; Lu, F.; Xu, X.; Liu, D.; Gang, C.; Fang, S.; Qin, X.; Pan, N.; et al. Spatial-temporal change in and influencing mechanisms for cropland soil organic carbon storage in the North China Plain from 1981 to 2019. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 9560–9576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Herzberger, A.; Wei, D.; Zhang, W.; Dou, Z.; Zhang, F. Cropping System Conversion led to Organic Carbon Change in China’s Mollisols Regions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 18064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Yang, R.; Ye, X.; Liu, X.; Zeng, F.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; et al. Spatio-temporal patterns of soil carbon and nitrogen characteristics along ariditygradients and their responses to climate change: Based on long-term fieldobservation data of Chinese Ecosystem Research Network. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 3582–3591. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Evolution Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of Black Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen During the Post 113 Years of Reclamation in Northeastern China. Master’s Thesis, Research Center of Soil and Water Conservation and Ecological Environment, the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences and Ministry of Education, Xianyang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Pei, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; Dai, J. Cultivated Quality Evolution and Obstacle Factors Diagnosis in the Lower Liaohe River Plain. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2023, 44, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Song, D.; Li, S.; Wang, J. Study of Temporal and Spatial Variation for Soil Organic Carbon in Croplands in Lower reaches of Liaohe river plain. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2014, 45, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Luo, X.; Li, H.; Zang, Y.; Ou, Y. Progress and Suggestions of Conservation Tillage in China. Strateg. Study CAE 2024, 26, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Qian, Y.; Guo, Z.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Guo, J.; Liu, F.; Peng, X. Evaluating the Regional Suitability of Conservation Tillage and Deep Tillage Based on Crop Yield in the Black Soil of Northeast China: A Meta-analysis. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2022, 59, 935–952. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, C.; Richel, A. The effect of corn straw return on corn production in Northeast China: An integrated regional evaluation with meta-analysis and system dynamics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, D.; Wang, C.; Pan, Y.; Pan, J.; Shi, X. Variations in cropland soil organic carbon fractions in the black soil region of China. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 184, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G.; Guo, X.; Fu, B.; Hu, C. Prediction of the spatial distribution of soil properties based on environmental correlation and geostatistics. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2009, 25, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. Design and Application of Classification Index Assignment Model of Cultivated Land Resources Quality in the Third National Land Survey Based on ArcGIS. Geomat. Spat. Inf. Technol. 2022, 45, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Li, H.; Xie, L.; Sun, J.; He, Y.; Wang, K. Characteristics of Spatiotemporal Variability of Soil Nutrients and pH of Cultivated Land in the Typical West Sichuan Plain. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 51, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Huang, F.; Li, B. Spatial Differentiation Characteristics of Soil Organic Matter in Dry Farmland in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2022, 59, 440–450. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.N.; Zhang, H.C.; Wang, P.X.; Wang, J.Z.; Lu, F. Sequence analysis of local indicators of spatio-temporal association for evolutionary pattern discovery. GISci. Remote Sens. 2025, 62, 2487292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ge, C.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, L.; Nie, C.; Huang, Y. Spatial distribution characteristics and scale effects of regional soil organic carbon. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2018, 34, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, X.; Lai, J.; Liu, F.; Shi, X. Spatial Heterogeneity and Zoning of Soil Organic Matter Based on Geostatistics and Spatial Autocorrelation: A Perspective from Land Consolidation. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2022, 43, 240–252. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Guo, X.; Kuang, L.; Li, W. Spatial Disparity Features and Protection Zoning of Cultivated Land Quality Based on Spatial Autocorrelation. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2018, 25, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Yang, Z.; Qin, F.; Guo, J.; Zhang, T. Spatial Heterogeneity of Vegetation Cover Change and Soil Conservation Evolution. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 37, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasteanu, I.J.; Jaenicke, E.C. Hot Spots and Spatial Autocorrelation in Certified Organic Operations in the United States. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2016, 45, 485–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Yang, S.; Xu, Z.; Vachaud, G. Preliminary Investigation of the Spatial Variability of Soil Properties. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1985, 9, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Qian, R.; Pei, J.; Li, S.; Wang, J. Estimating soil organic carbon sequestration potential in the Chinese Mollisols region. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Conservation agriculture-mediated soil carbon sequestration: A review. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2022, 30, 658–670. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Huang, D.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Tian, C.; McLaughlin, N.B.; et al. Development and effects of conservation tillage in the black soil region of Northeast China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2022, 42, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Hu, X.; Ma, J.; Ye, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, Q.; Lin, H. Effects of long-term organic material applications on soil carbon and nitrogen fractions in paddy fields. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 196, 104483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Accumulation of organic carbon and its association with macro-aggregates during 100 years of oasis formation. Catena 2019, 172, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Digging deeper: A holistic perspective of factors affecting soil organic carbon sequestration in agroecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 3285–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cui, Z.; Fan, M.; Vitousek, P.; Zhao, M.; Ma, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yan, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Producing more grain with lower environmental costs. Nature 2014, 514, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Chang, S.X.; Cui, S.; Jagadamma, S.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, Y. Residue retention promotes soil carbon accumulation in minimum tillage systems: Implications for conservation agriculture. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 140147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, R.; Lamichhane, S.; Acharya, B.S.; Bista, P.; Sainju, U.M. Tillage, crop residue, and nutrient management effects on soil organic carbon in rice-based cropping systems: A review. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.C.; VandenBygaart, A.J.; MacDonald, J.D.; Cerkowniak, D.; McConkey, B.G.; Desjardins, R.L.; Angers, D.A. Revisiting no-till’s impact on soil organic carbon storage in Canada. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 198, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, D.; Schipper, L.A.; Pronger, J.; Moinet, G.Y.K.; Mudge, P.L.; Calvelo Pereira, R.; Kirschbaum, M.U.F.; McNally, S.R.; Beare, M.H.; Camps-Arbestain, M. Management practices to reduce losses or increase soil carbon stocks in temperate grazed grasslands: New Zealand as a case study. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 265, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Zhu, L.; Shen, Y.; Li, S. Biochar Effects on Organic Carbon and Nitrogen in Soil Aggregates in Semiarid Farmland. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2015, 34, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Wiesmeier, M.; Conant, R.T.; Kühnel, A.; Sun, Z.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Hou, R.; Cong, P.; Liang, R.; Ouyang, Z. Large soil organic carbon increase due to improved agronomic management in the North China Plain from 1980s to 2010s. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 24, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wei, K.; Chen, L.; Liang, W. Effects of conservation tillage on soil aggregation and aggregate binding agents in black soil of Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 2012, 124, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shen, P.; Zhang, H.; Mo, F.; Wen, X.; Liao, Y. Study on the Relationship Between Total Nitrogen and Nitrogen Functional Microorganisms in Soil Aggregates under Long-Term Conservation Tillage. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2024, 61, 1653–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, R.; Gao, J.; Zhu, P.; Lu, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X.; Peng, C.; Yang, D. Research progress on the effects of conservation tillage on soil aggregates and microbiological characteristics. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2020, 29, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Han, X.; Du, S.; Li, L.-J. Profile stock of soil organic carbon and distribution in croplands of Northeast China. Catena 2019, 174, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bian, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wang, C.; Sun, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, G. Integrating Landscape Pattern Metrics to Map Spatial Distribution of Farmland Soil Organic Carbon on Lower Liaohe Plain of Northeast China. Land 2023, 12, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, W.; Chen, J.; Alexandrov, G.; Cao, Y. Decipher soil organic carbon dynamics and driving forces across China using machine learning. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 3394–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F. Re-thinking the Establishment of the Farmland Soil Health Assessment System. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2024, 61, 879–891. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Study on Environmental and Economic Effects of Soil Measurement and Fertilization Project of Lower Reaches of Liaohe River Plain. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Z.; Qin, Y.; Yu, X. Spatial variability in soil organic carbon and its influencing factors in a hilly watershed of the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2016, 137, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Pei, J.; Li, S.; Zou, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Main Characteristics and Utilization Countermeasures for Black Soils in Different Regions of Northeast China. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2023, 54, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakšić, S.; Ninkov, J.; Milić, S.; Vasin, J.; Živanov, M.; Jakšić, D.; Komlen, V. Influence of slope gradient and aspect on soil organic carbon content in the region of Niš, Serbia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, W. Changes in soil organic carbon stocks as affected by cropping systems and cropping duration in China’s paddy fields: A meta-analysis. Clim. Change 2011, 112, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Dai, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, P. Soil Organic Carbon Storage of China and the Sequestration Dynamics in Agricultural Lands. Adv. Earth Sci. 2003, 18, 609–618. [Google Scholar]

- Slessarev, E.W.; Mayer, A.; Kelly, C.; Georgiou, K.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Nuccio, E.E. Initial soil organic carbon stocks govern changes in soil carbon: Reality or artifact? Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 29, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhu, X. The soil microbial carbon pump as a new concept for terrestrial carbon sequestration. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2021, 51, 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wood, J.; Franks, A.; Armstrong, R.; Tang, C. Long-term CO2 enrichment alters the diversity and function of the microbial community in soils with high organic carbon. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 144, 107780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, M.-E.; Chantigny, M.H.; Vanasse, A.; Menasseri-Aubry, S.; Royer, I.; Angers, D.A. Management practices differently affect particulate and mineral-associated organic matter and their precursors in arable soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 107867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, S.R.; Beare, M.H.; Curtin, D.; Meenken, E.D.; Kelliher, F.M.; Calvelo Pereira, R.; Shen, Q.; Baldock, J. Soil carbon sequestration potential of permanent pasture and continuous cropping soils in New Zealand. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 4544–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, K.; Jackson, R.B.; Vindušková, O.; Abramoff, R.Z.; Ahlström, A.; Feng, W.; Harden, J.W.; Pellegrini, A.F.A.; Polley, H.W.; Soong, J.L.; et al. Global stocks and capacity of mineral-associated soil organic carbon. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; An, T.; Li, S.; Sun, L.; Pei, J.; Ding, F.; Xu, Y.; Fu, S.; Gao, X.; Wang, J. Distribution and Sequestration of Exogenous New Carbon in Soils Different in Fertility. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2016, 53, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

| Rank | SOC Content Range (g kg−1) | Level |

|---|---|---|

| I | ≥23.20 | Very High |

| II | 17.40~23.20 | High |

| III | 11.60~17.40 | Medium |

| IV | 5.80~11.60 | Moderately Low |

| V | 3.48~5.80 | Low |

| VI | <3.48 | Very Low |

| Rank | SOCr Range (g kg−1 a−1) | Number of Sample | Average (g kg−1 a−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | ≥0.28 | 269 | 0.40 ± 0.10 a |

| II | 0.10~0.28 | 1158 | 0.16 ± 0.05 b |

| III | 0.00~0.10 | 3075 | 0.04 ± 0.03 c |

| IV | −0.10~0.00 | 4114 | −0.04 ± 0.03 d |

| V | −0.32~−0.10 | 1606 | −0.16 ± 0.05 e |

| VI | <−0.32 | 194 | −0.47 ± 0.10 f |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shu, X.; Pei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Song, D.; Dai, J.; Fan, X.; et al. Dynamics and Rates of Soil Organic Carbon of Cultivated Land Across the Lower Liaohe River Plain of China over the Past 40 Years. Land 2026, 15, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010099

Shu X, Pei J, Zhang Y, Wang S, Liu S, Wang M, Zhang X, Song D, Dai J, Fan X, et al. Dynamics and Rates of Soil Organic Carbon of Cultivated Land Across the Lower Liaohe River Plain of China over the Past 40 Years. Land. 2026; 15(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleShu, Xin, Jiubo Pei, Yao Zhang, Siyin Wang, Shunguo Liu, Mengmeng Wang, Xi Zhang, Dan Song, Jiguang Dai, Xiaolin Fan, and et al. 2026. "Dynamics and Rates of Soil Organic Carbon of Cultivated Land Across the Lower Liaohe River Plain of China over the Past 40 Years" Land 15, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010099

APA StyleShu, X., Pei, J., Zhang, Y., Wang, S., Liu, S., Wang, M., Zhang, X., Song, D., Dai, J., Fan, X., & Wang, J. (2026). Dynamics and Rates of Soil Organic Carbon of Cultivated Land Across the Lower Liaohe River Plain of China over the Past 40 Years. Land, 15(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010099