Territorial Rebalancing from an Axiological Perspective: A Reaction Capacity Index of Sicily’s Inner Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

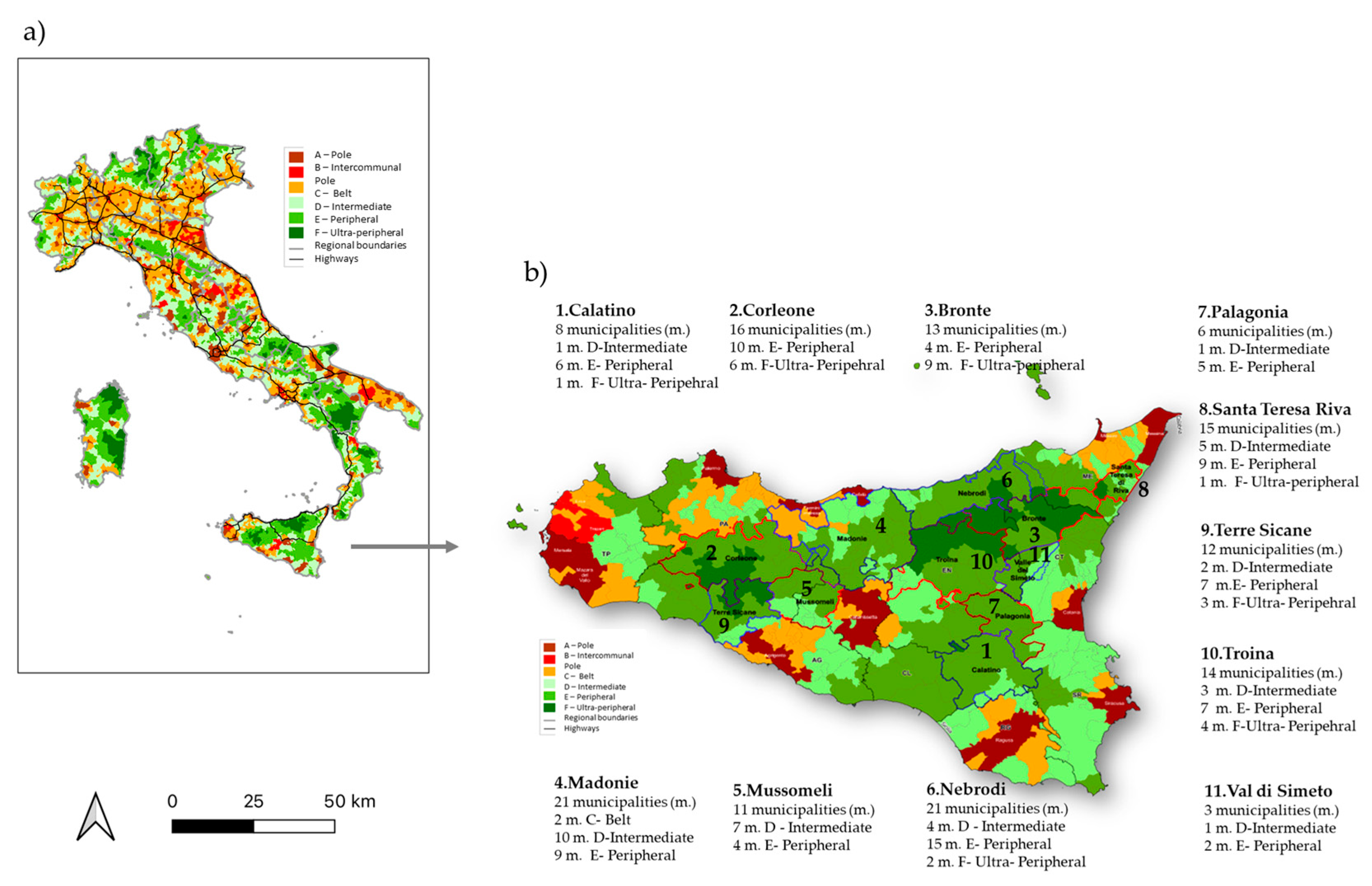

1.1. Towards a Taxonomy of Territorial Imbalances

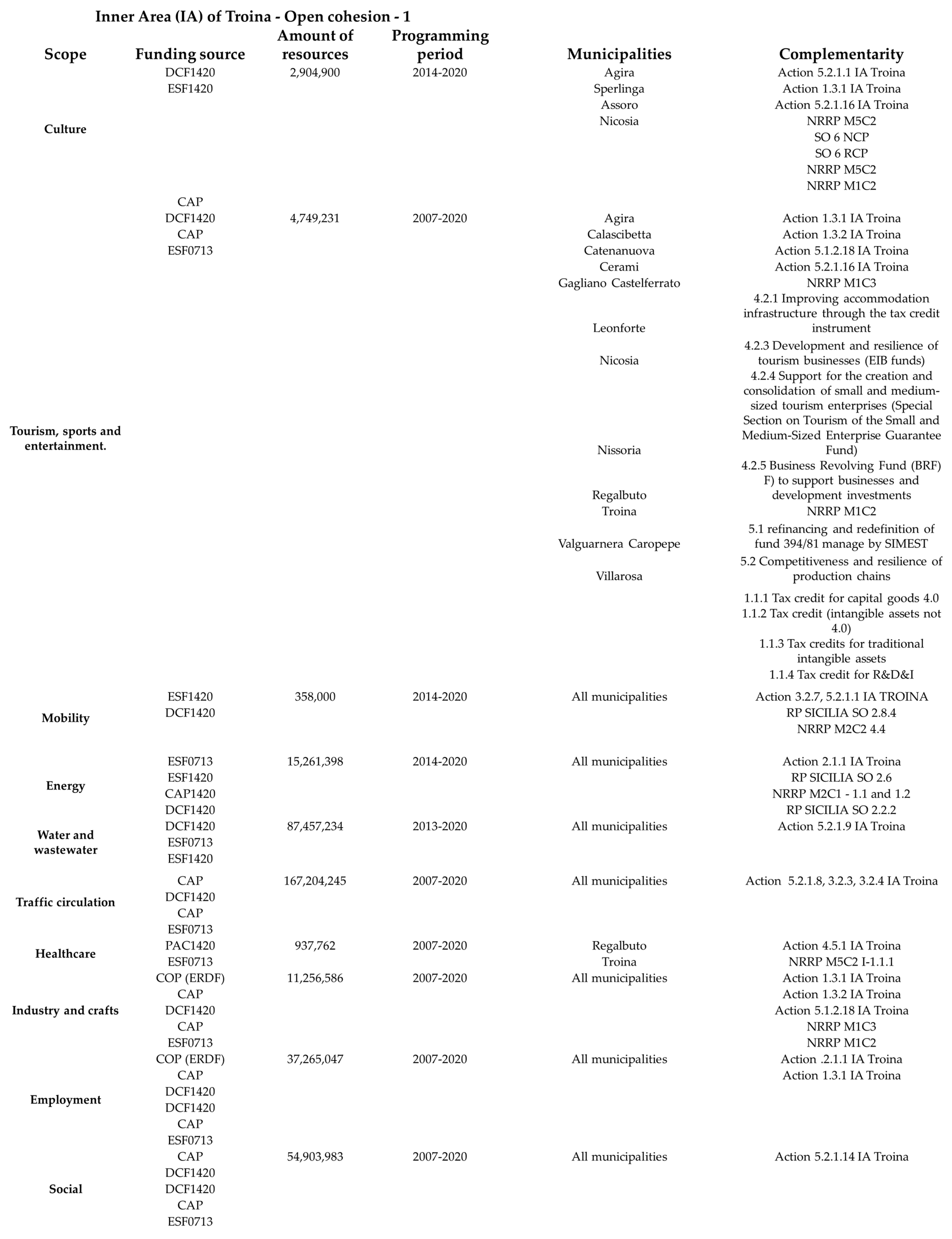

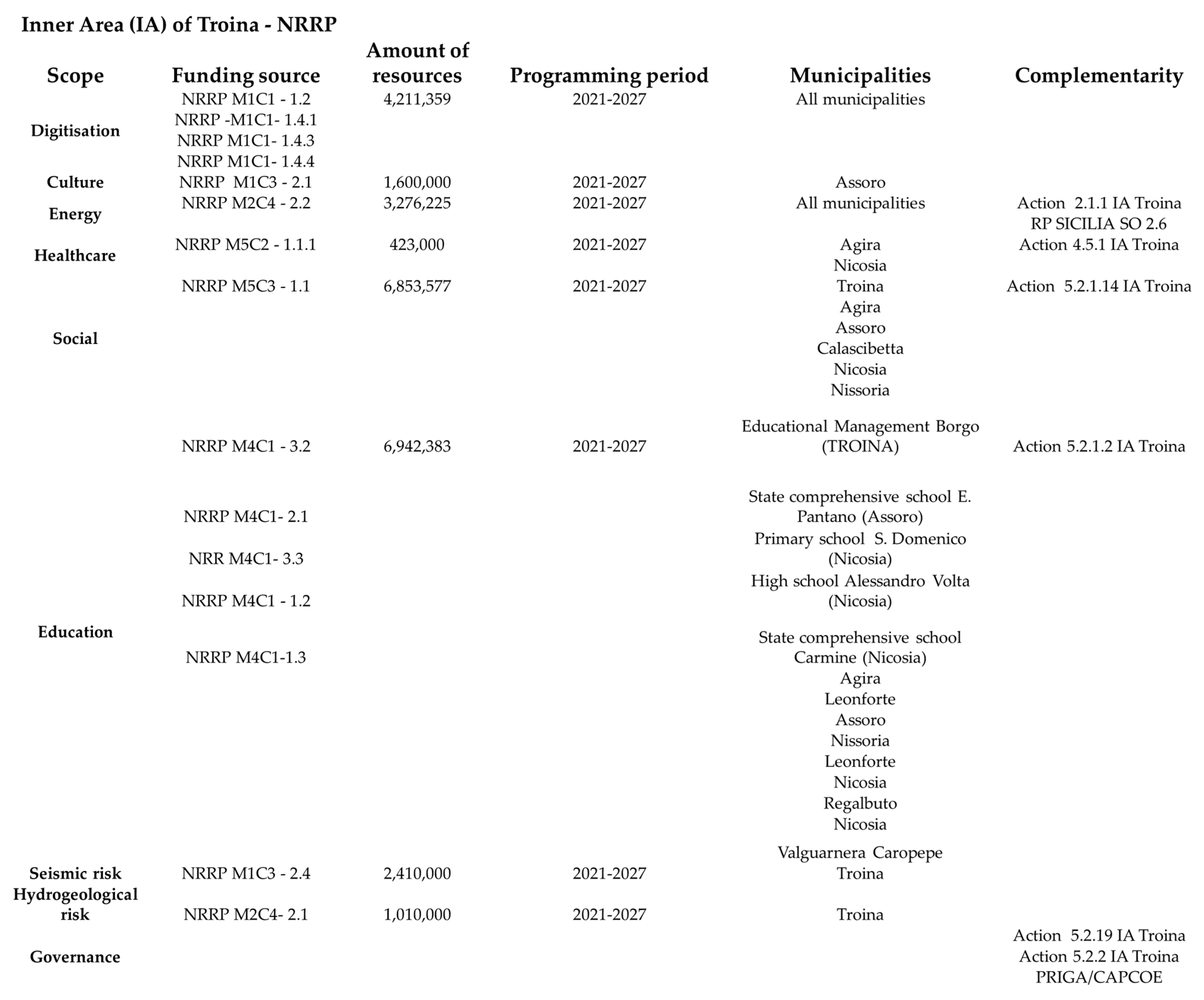

1.2. Territorial Rebalancing Policies and Funding

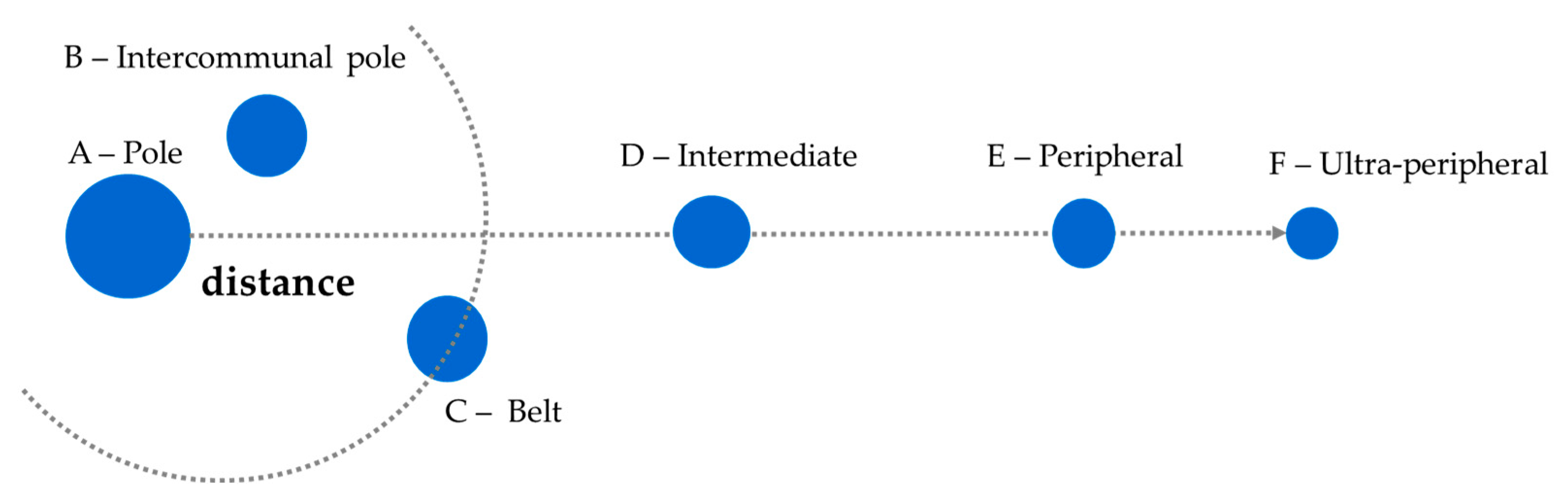

1.3. Cognitive Model of Marginal Territories. NSIA Classification

1.4. Axiological Domains: Towards a New Cognitive Model of Marginal Territories

1.5. Structure of the Paper

- Section 2 introduces the concept of territorial capital;

- Section 3 introduces the NSIA classification and Sicilian NSIA;

- Section 4 illustrates the methodological approach;

- Section 5 reports and discusses the results;

- Section 6 offers reflections on the cognitive model and the application of the IRCI as an operational tool for supporting territorial rebalancing policies. It also identifies the limitations of the research and its potential future developments.

- Section 7 summarises the key findings of the study.

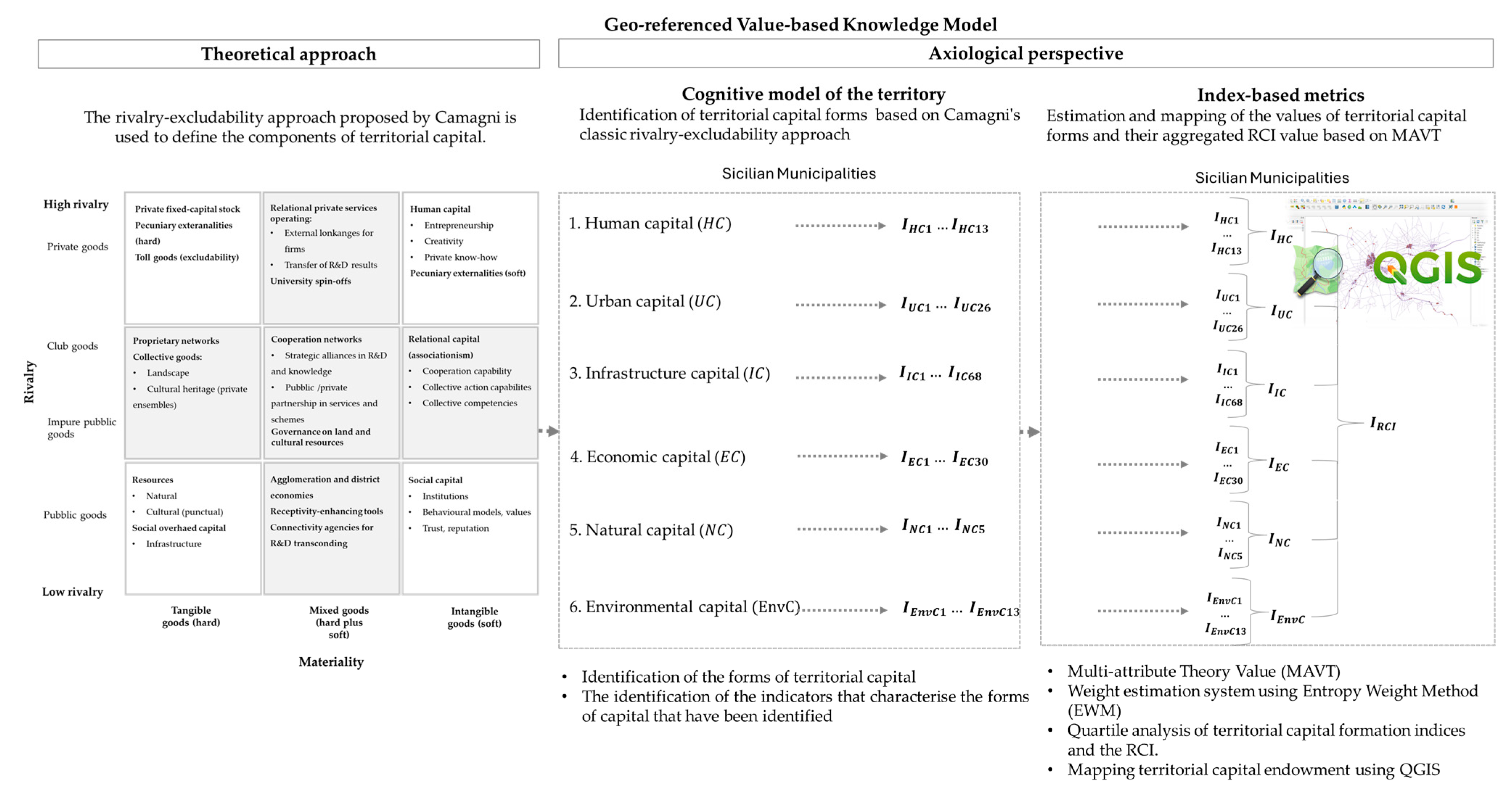

2. The Concept of Territorial Capital

3. Materials

- Consistency of the new area to be nominated with the Map of Internal Areas proposed for the 2021–2027 programming cycle.

- The existence of a defined and recognisable identity and geomorphological system.

- The area is experiencing demographic difficulties.

- Essential services need to be reorganized.

- The willingness and ability of local authorities to collaborate in order to achieve a shared objective.

- Size of the area.

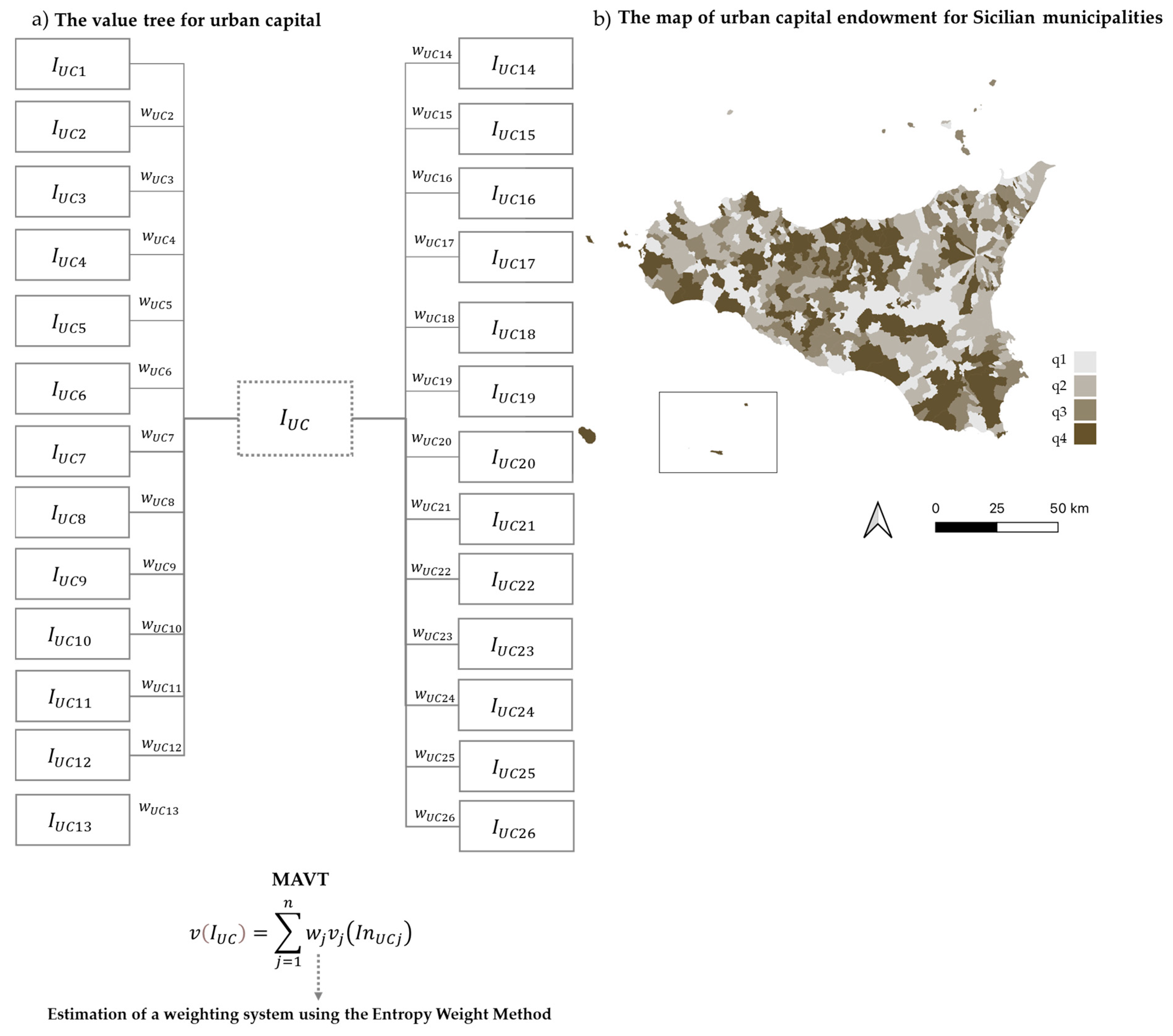

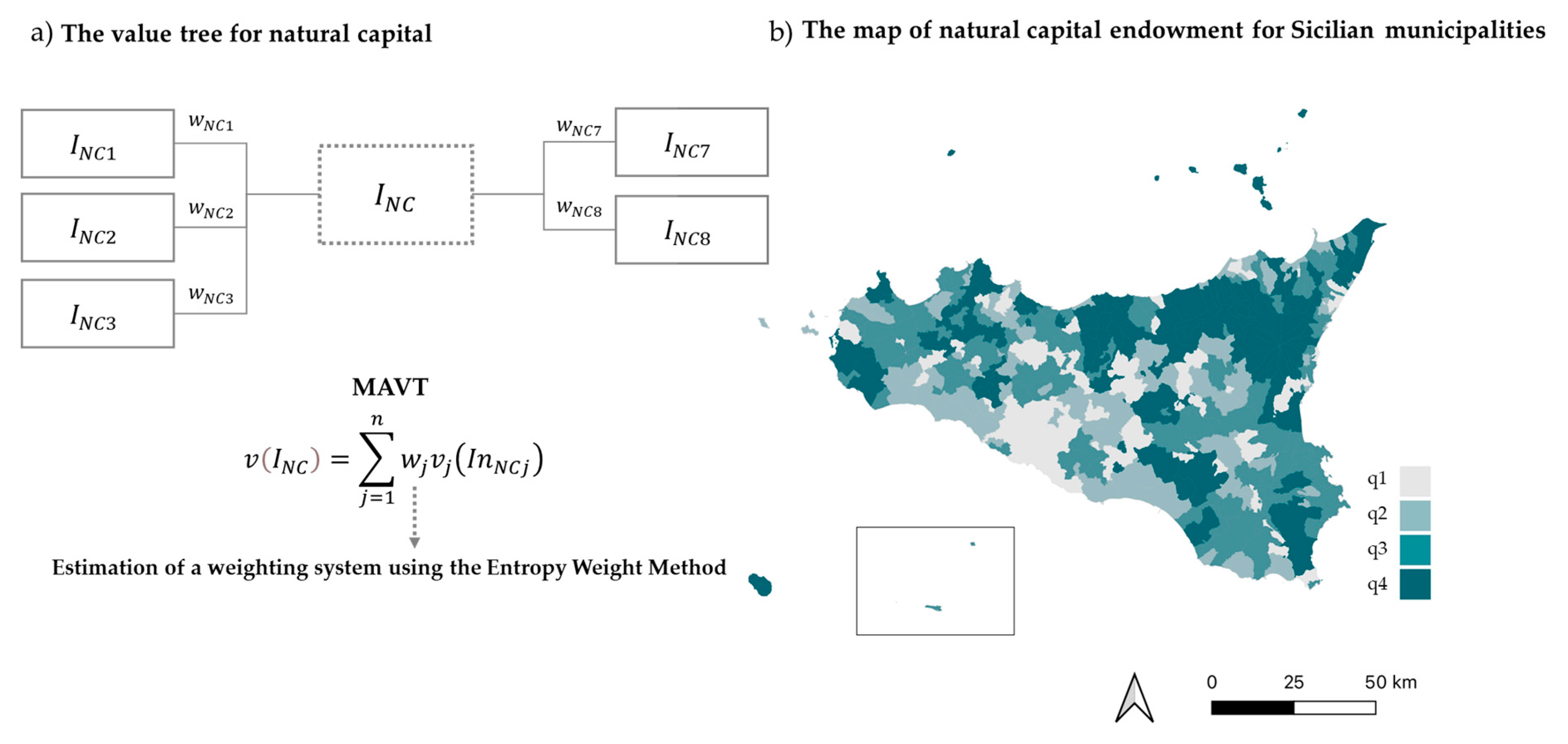

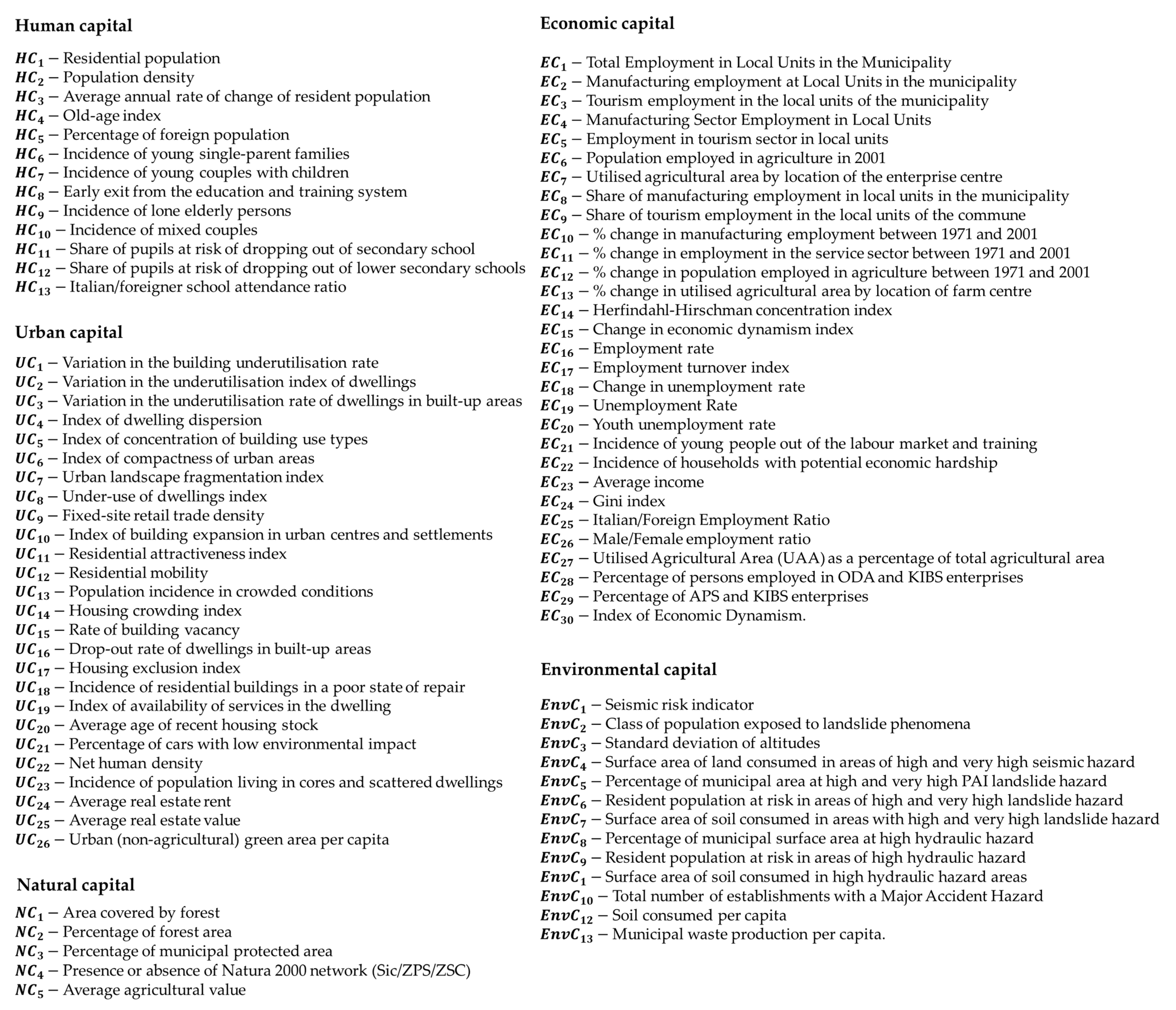

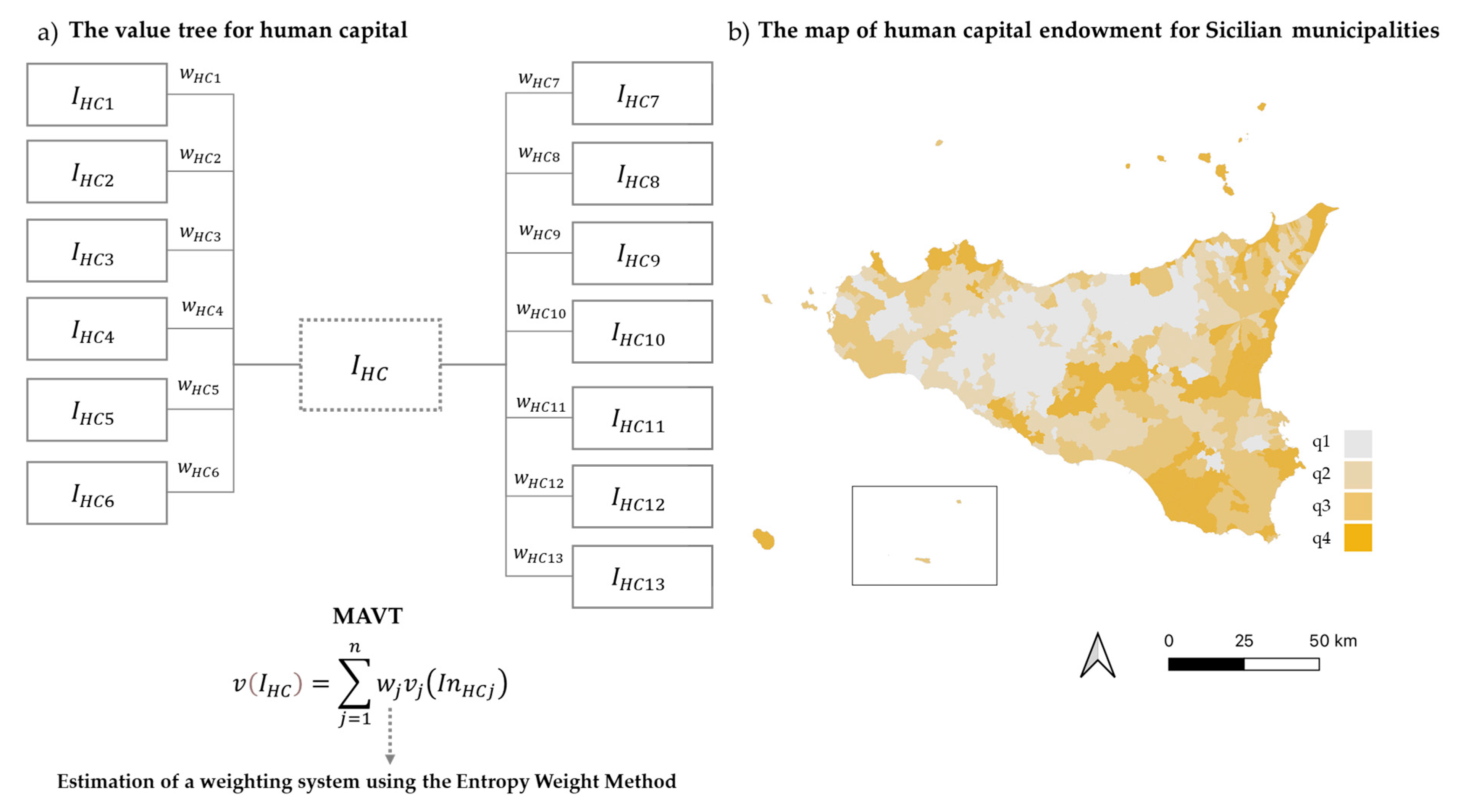

4. Methods

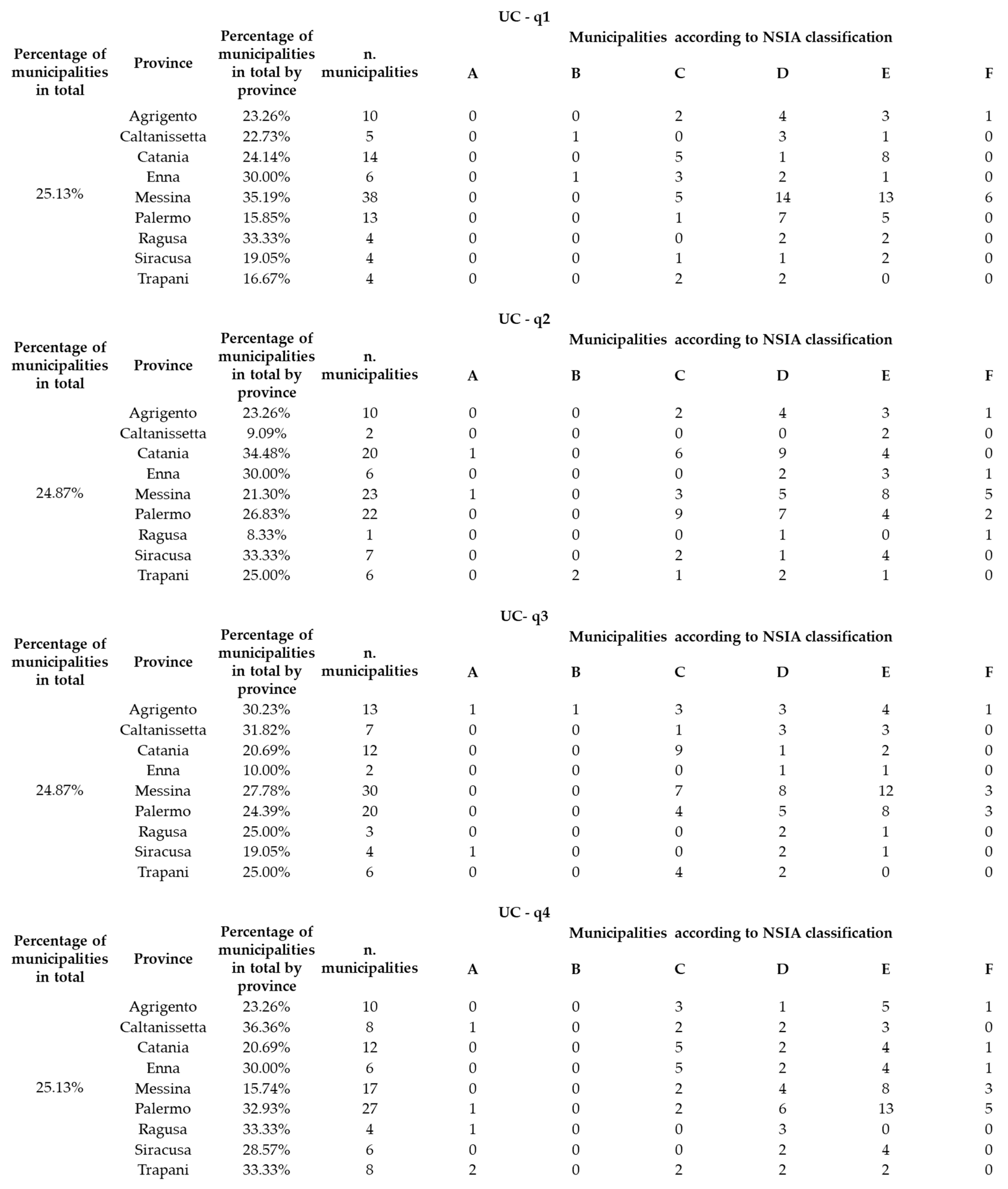

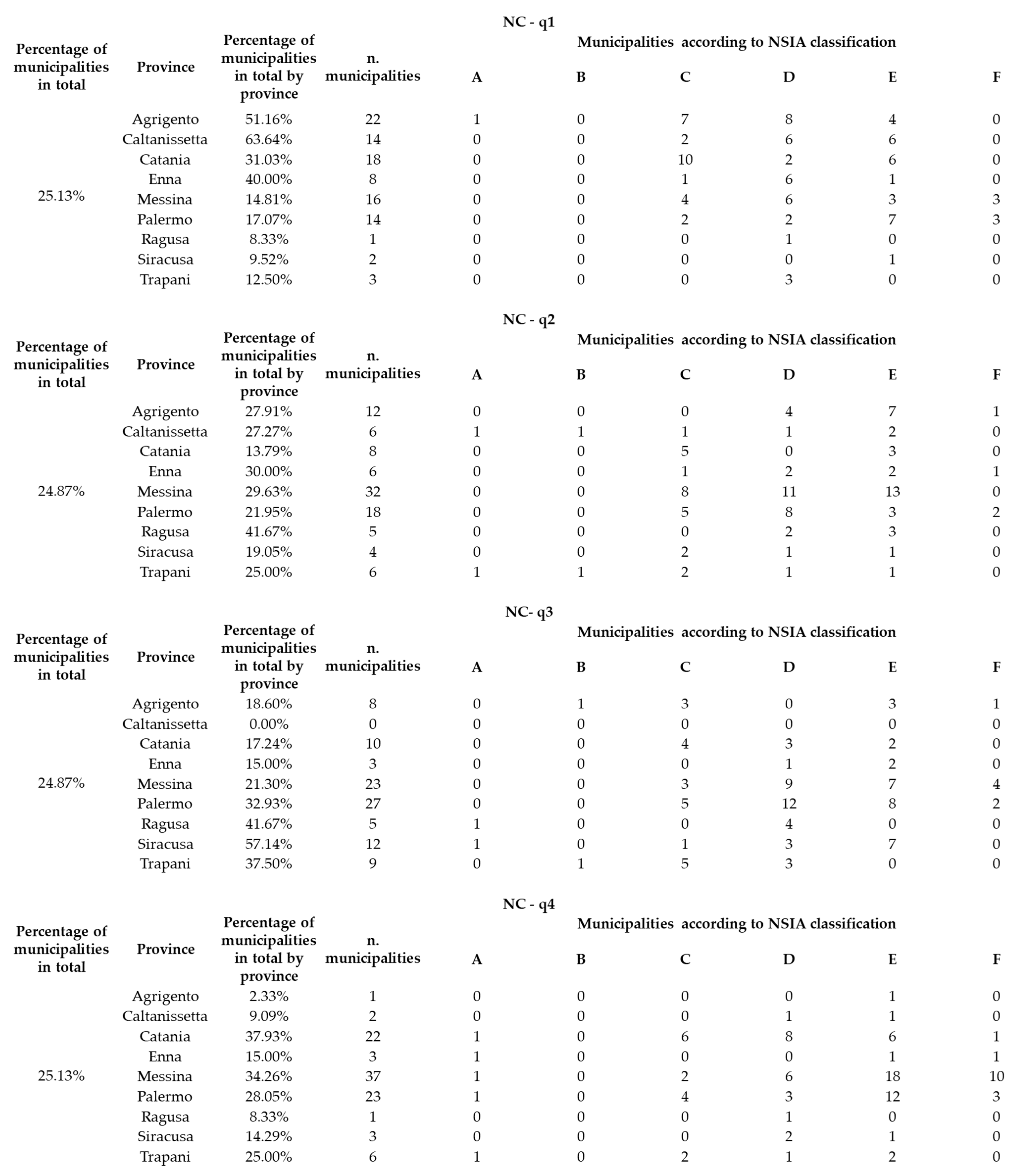

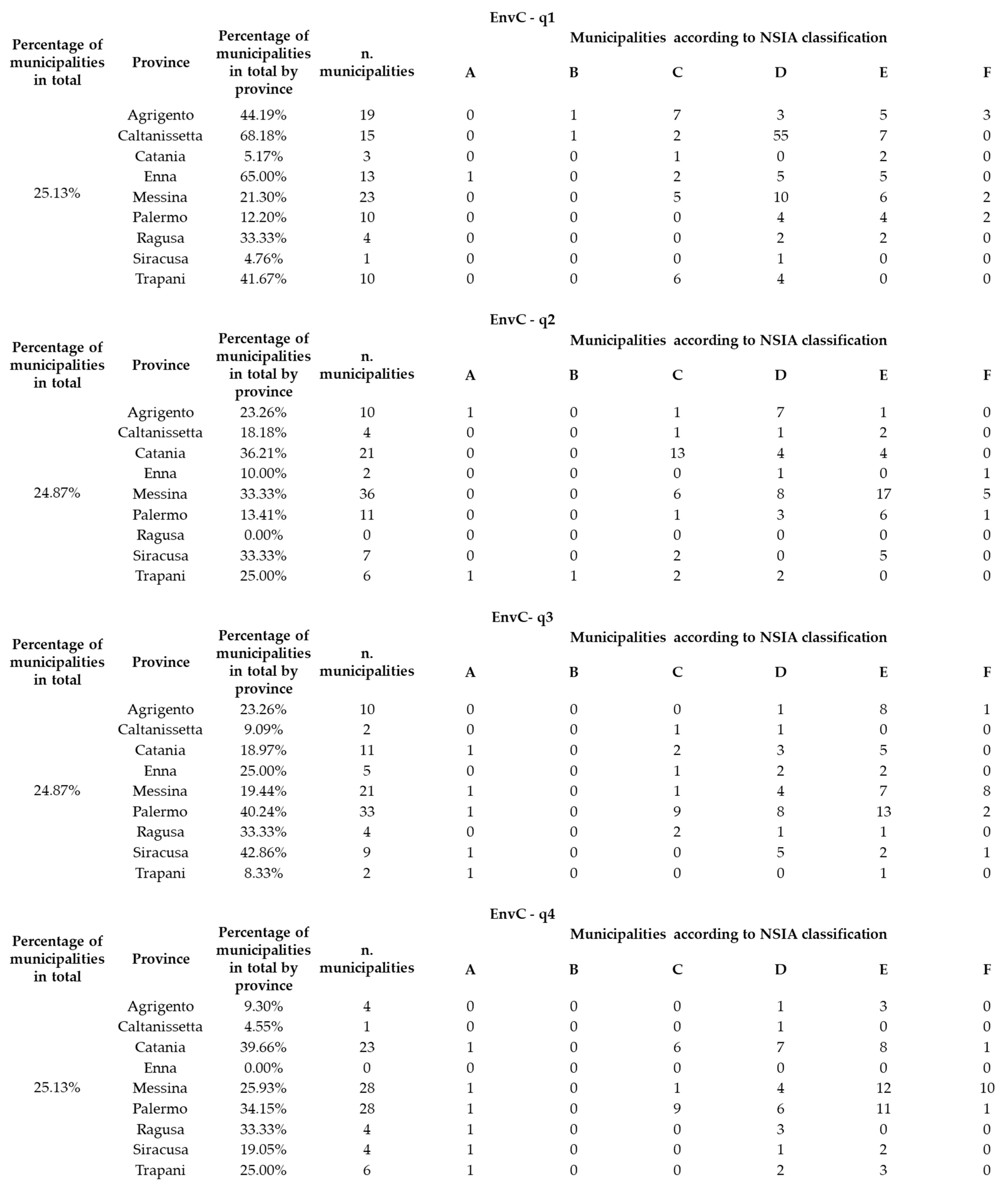

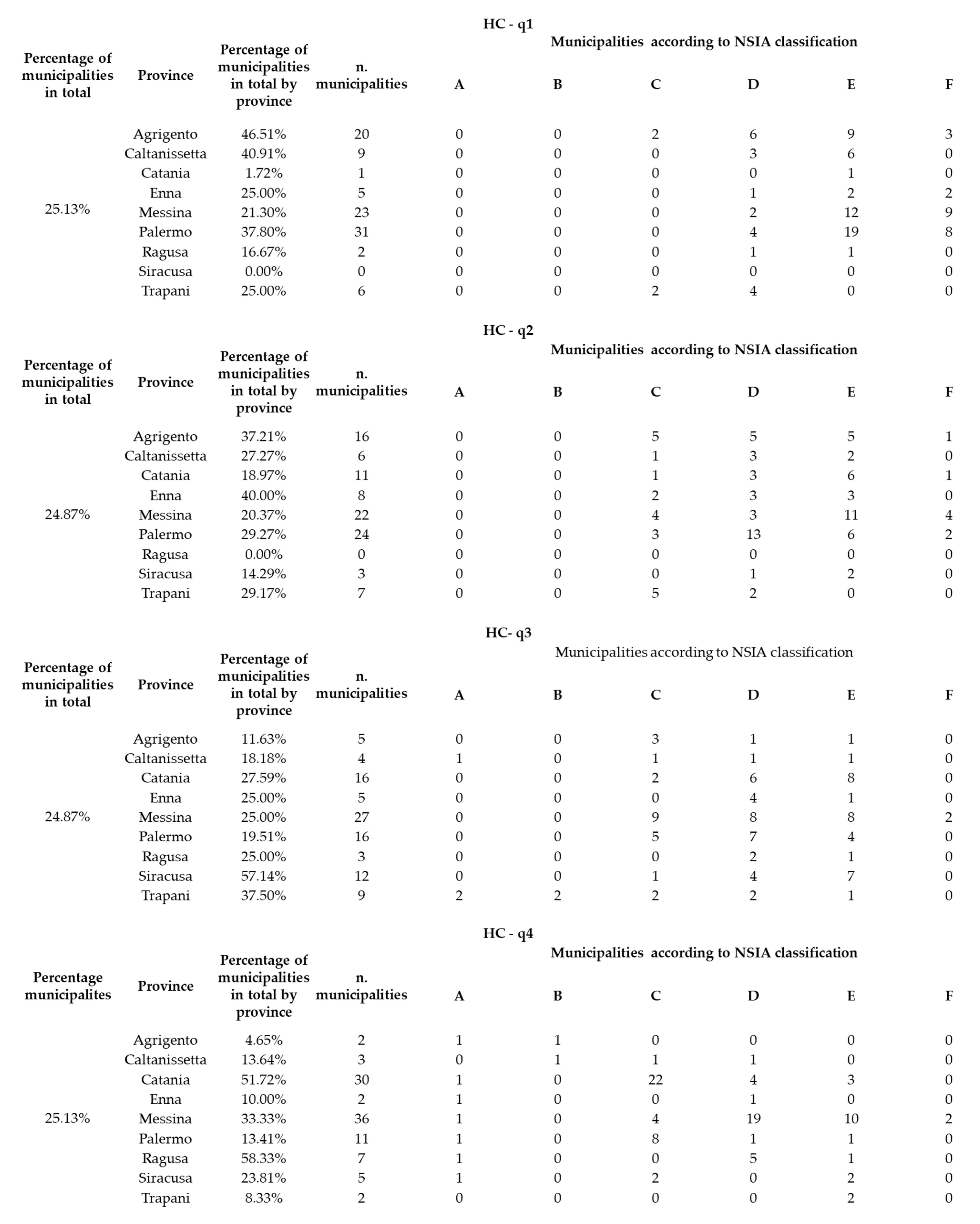

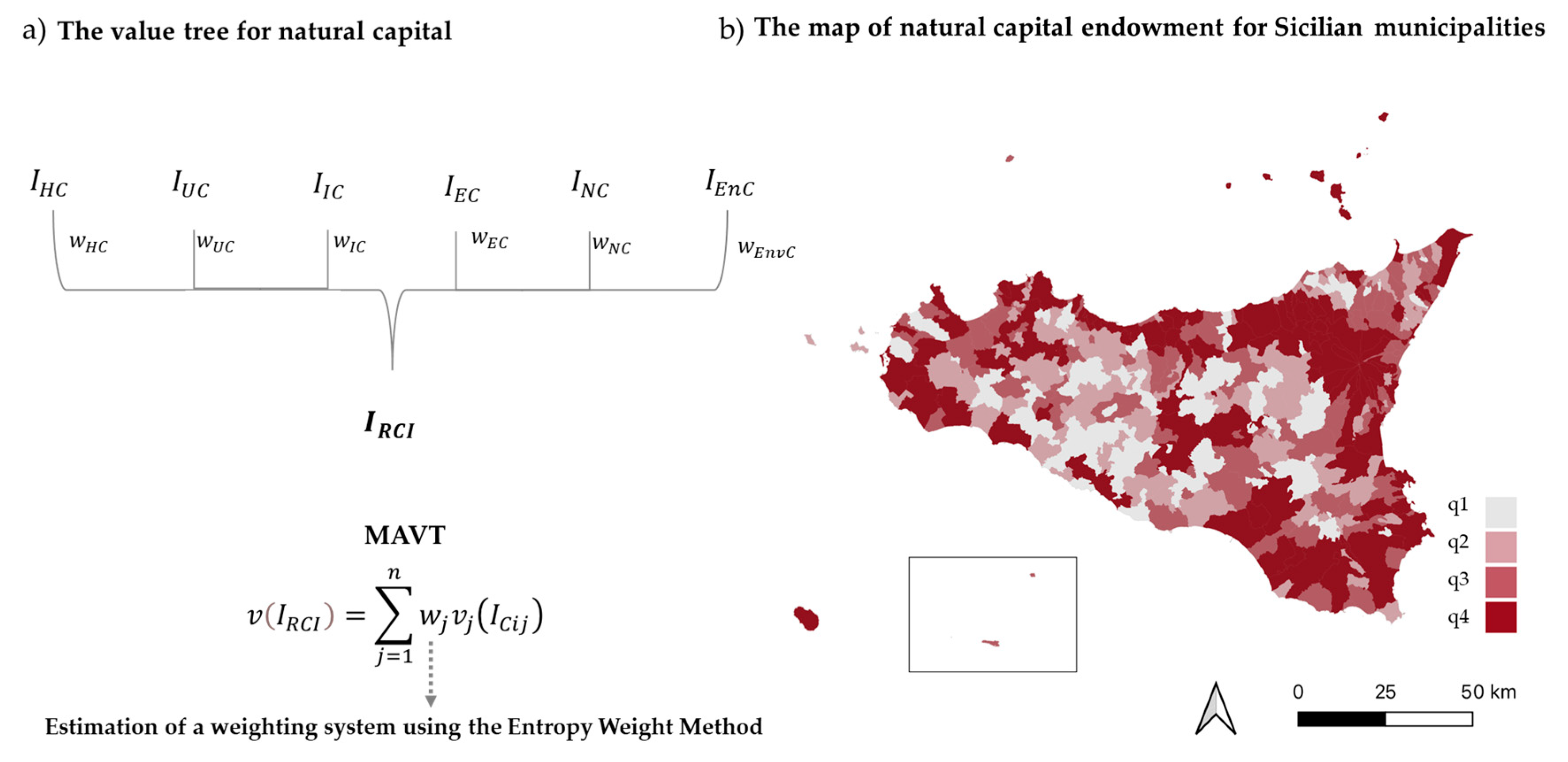

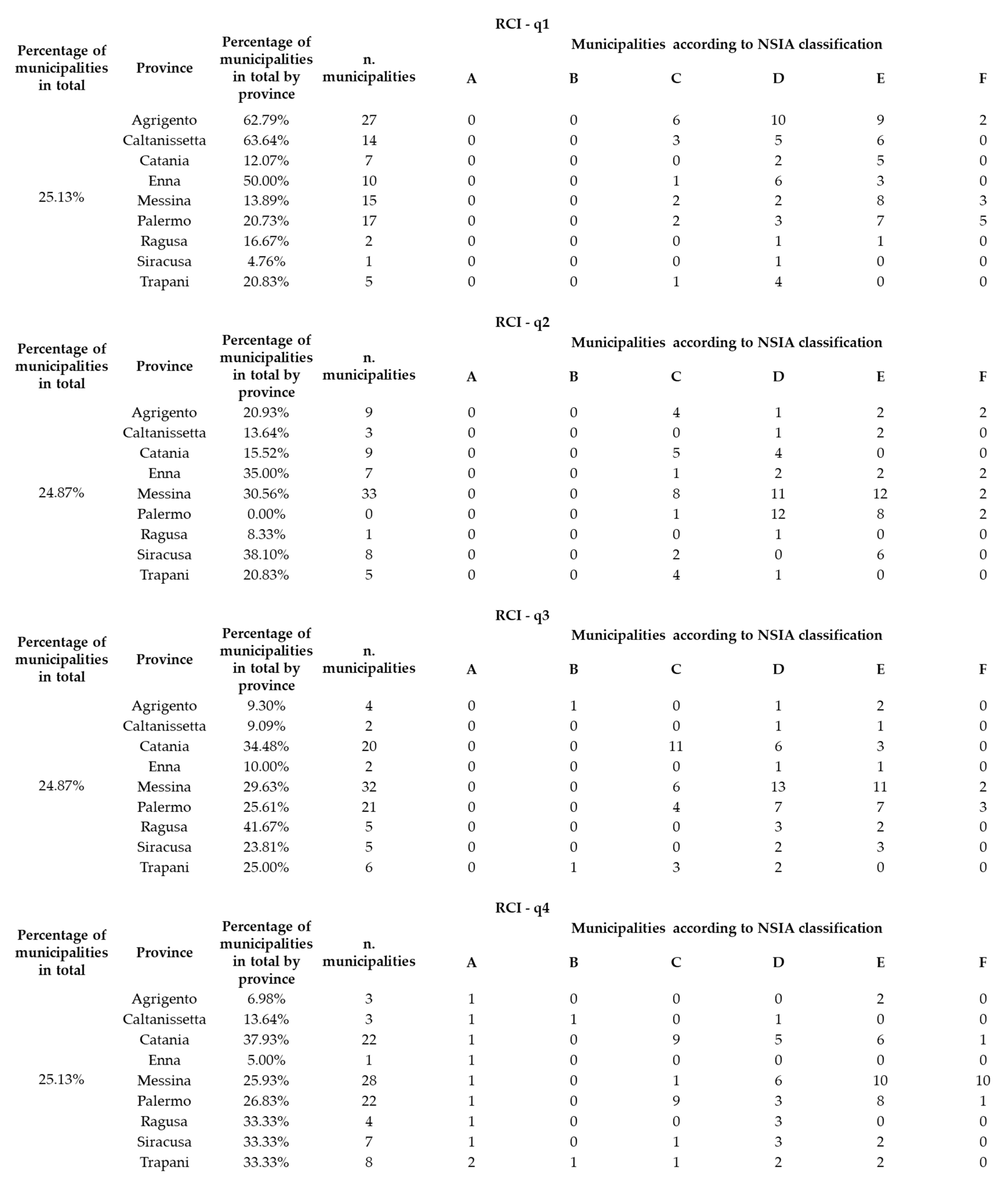

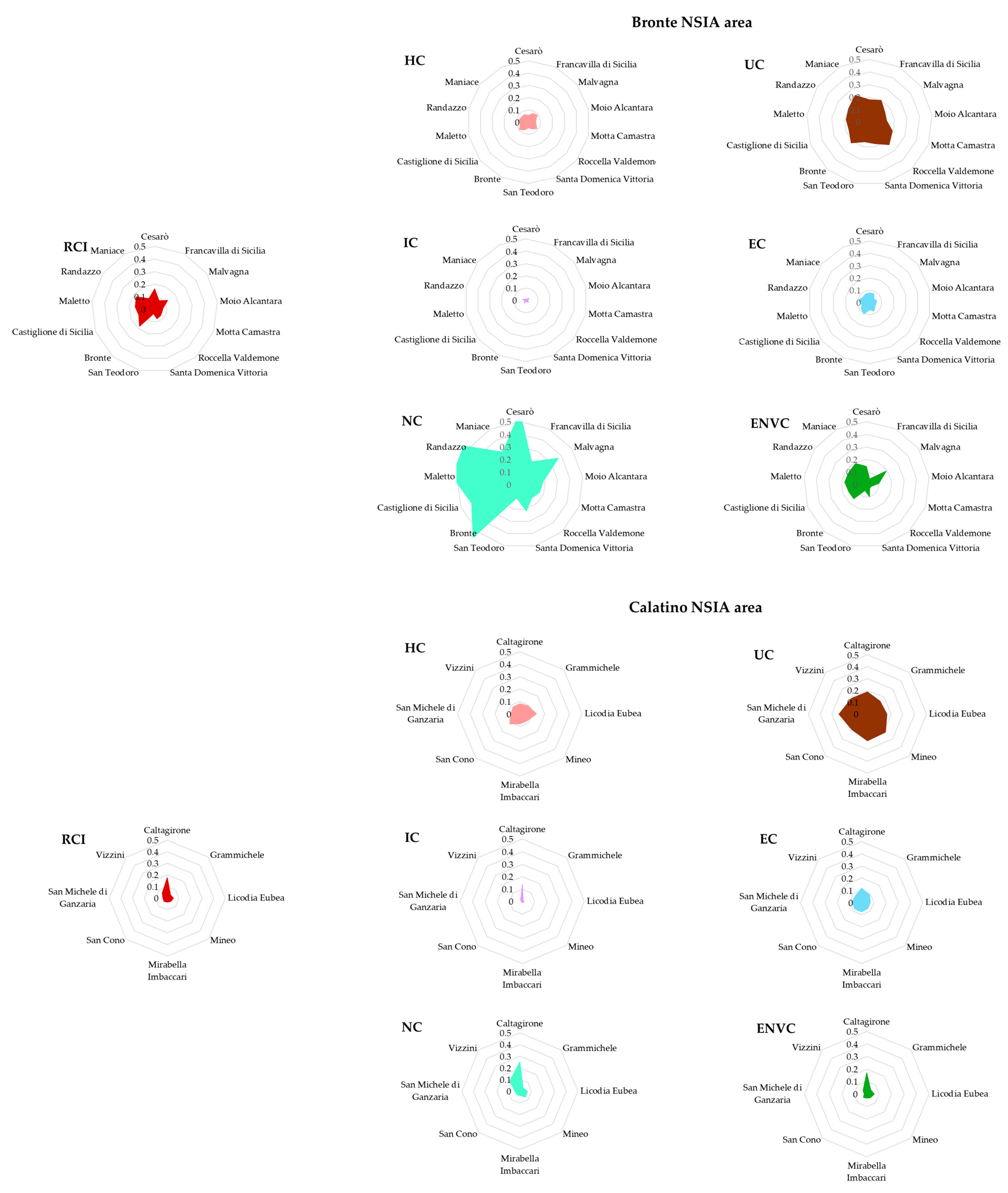

5. Results

6. Discussion

- Development and strengthening of essential services.

- Strengthening mobility within the area.

- Promoting heritage identity and strengthening the competitiveness of SMEs.

- Protecting the environment using ecosystem-based approaches.

- Measures for the digitisation of local public administration.

- Measures to strengthen and improve school environments.

- Reorganisation and upgrading of local health services.

- Integration of services to promote work-life balance.

- Promotion of entrepreneurship through supporting for the creation of new SMEs.

- Promotion of new investments to increase competitiveness.

- Enhancing of public spaces to promote tourist and residential appeal.

- Interventions for the preserving and enhancing of historical and cultural heritage.

- Integrated measures aimed at enhancing and promoting the use of natural areas.

- Redevelopment measures for historic centres and open spaces.

- Measures to encourage the creation of energy communities.

- Measures to improve the integrated water service at every stage of the supply chain.

- Emergency management and risk prevention measures.

- Interventions for the construction of infrastructure, equipment, and resources for waste management, collection, reuse, and recycling.

- Protection of areas falling within Natura 2000 sites.

- Green infrastructure and the creation of urban forests.

- Adoption of technological solutions to reduce energy consumption in public buildings and facilities, as well as in public lighting networks.

7. Conclusions

- The highest levels are found in the eastern areas of Sicily, while the lowest levels are found in the central areas.

- The lowest level is found in the provinces of Agrigento and Caltanissetta. Investment is needed to support the development of municipalities in these provinces.

- The highest level is found in the provinces of Catania and Palermo.

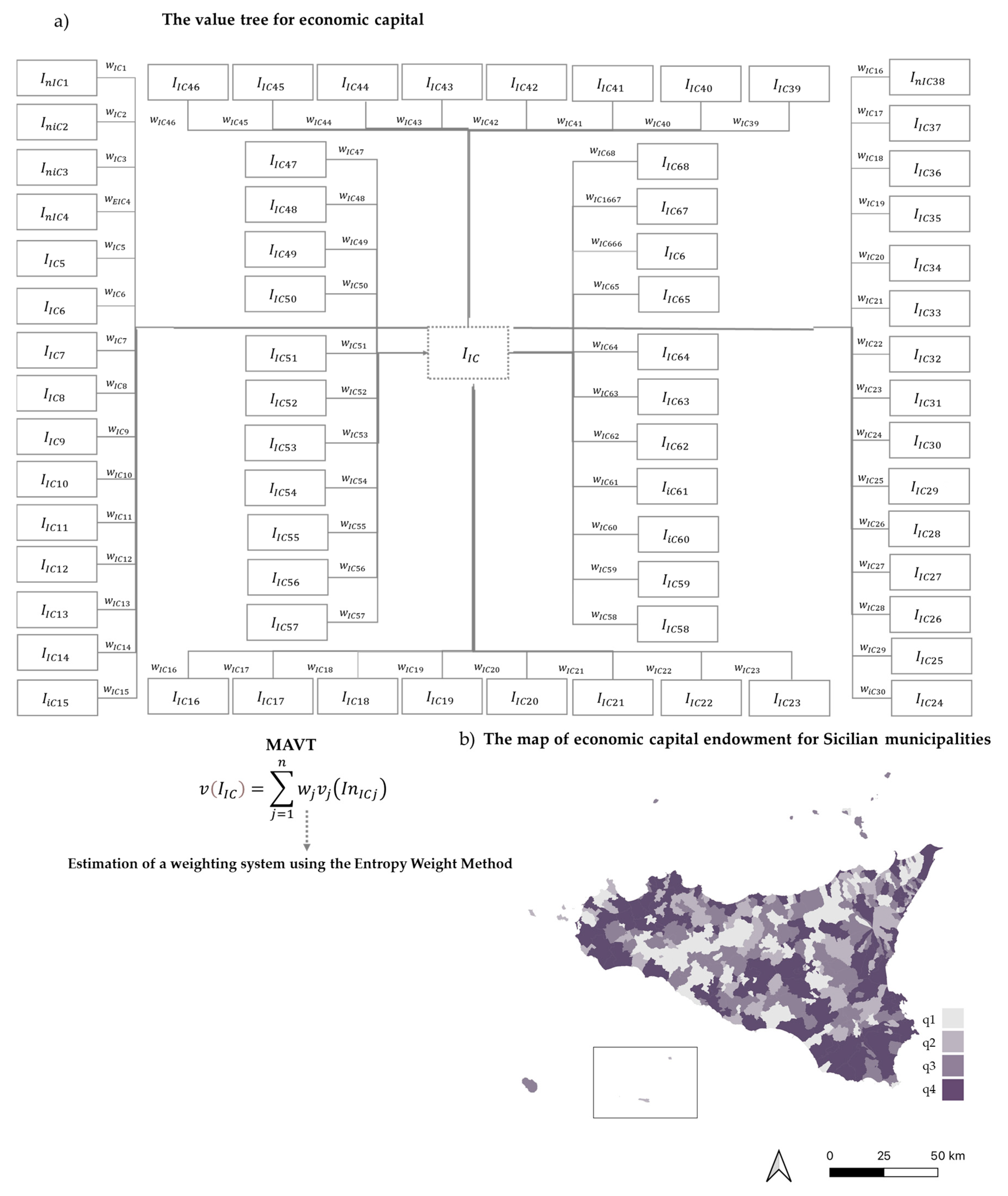

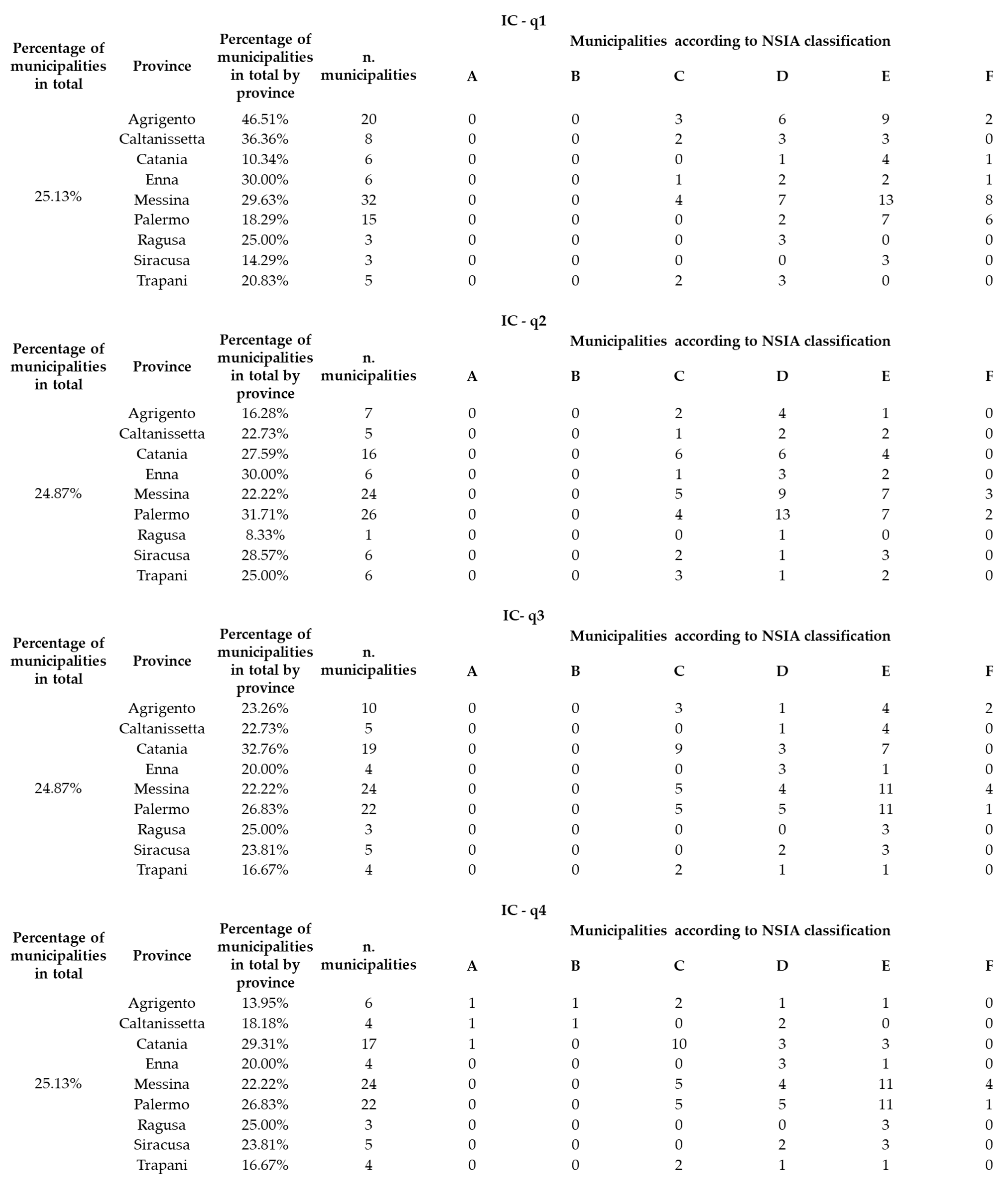

- The municipalities with the worst endowment, i.e., those in the first quartile of the index, are in the provinces of Agrigento and Caltanissetta. According to the NSIA classification, most of them are classified as D—Intermediate, E—Peripheral or F—Ultra-peripheral. This shows that even municipalities considered less peripheral under the NSIA classification, such as those in class D (Intermediate), have low human capital endowment. Furthermore, it shows that municipalities in different NSIA classes have the same level of human capital endowment.

- The municipalities with the best endowment, falling within the fourth quartile of the index, are in the provinces of Catania and Palermo. According to the NSIA classification, they fall into all NSIA classes. This suggests that the NSIA classification, and therefore the differentiation into different classes based on the criterion of peripherality, does not accurately reflect their value. In this case, given that these results concern the two main Sicilian provinces, it is likely that some of the more peripheral areas benefit from “organised proximity”, which allows them to mitigate the effects of their geographical peripherality.

- A fairly diverse distribution of urban capital among municipalities in central Sicily. Inner areas in central Sicily have a good level of urban capital. This suggests that the classic contrast between inland and coastal areas does not apply in terms of urban capital.

- A better distribution in the southern and central-northern areas.

- Approximately one third of municipalities with a low level are located in the provinces of Catania and Syracuse.

- Approximately one third of municipalities with a high level of urban capital are located in the provinces of Caltanissetta, Enna, Palermo, Ragusa and Trapani.

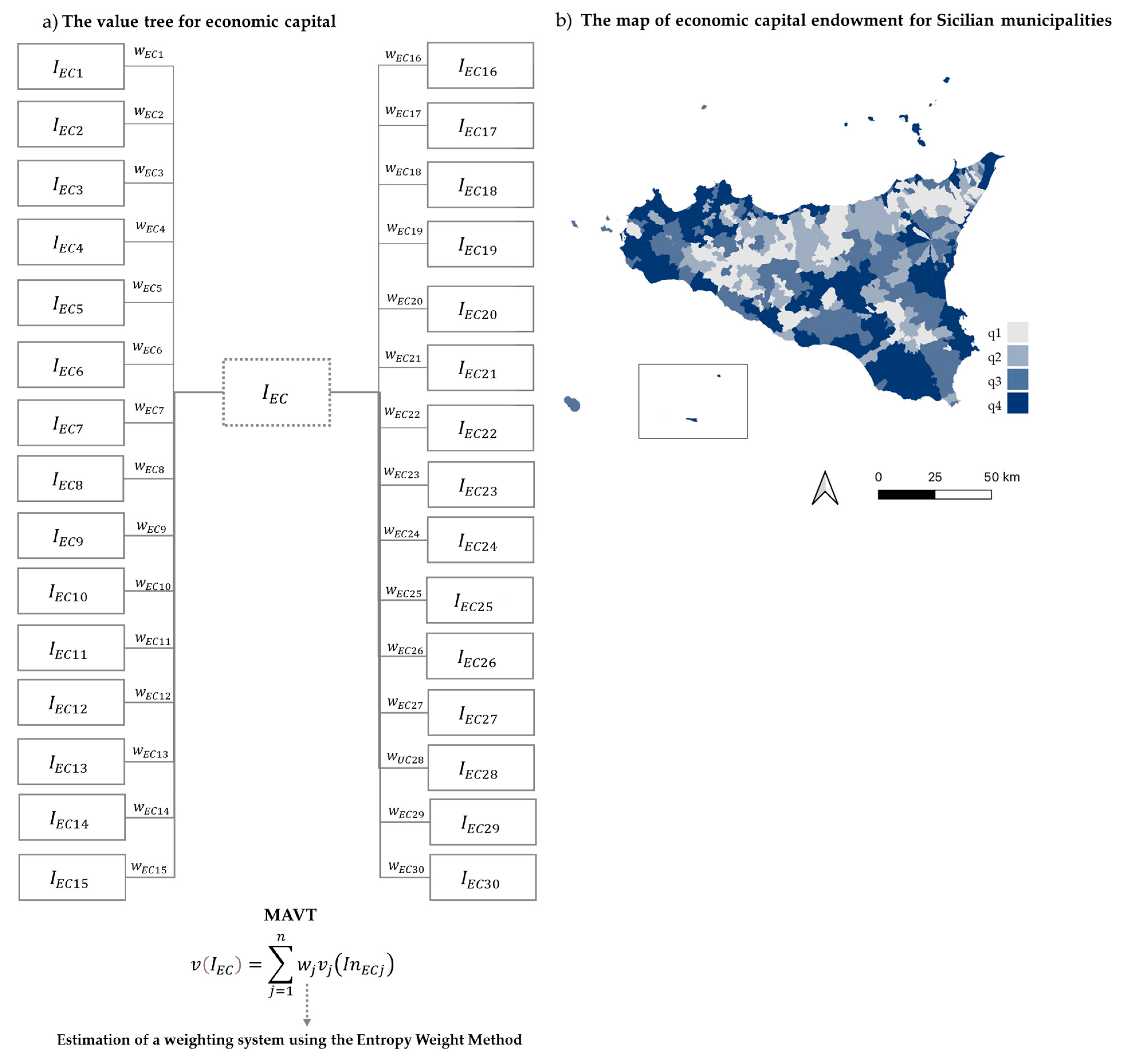

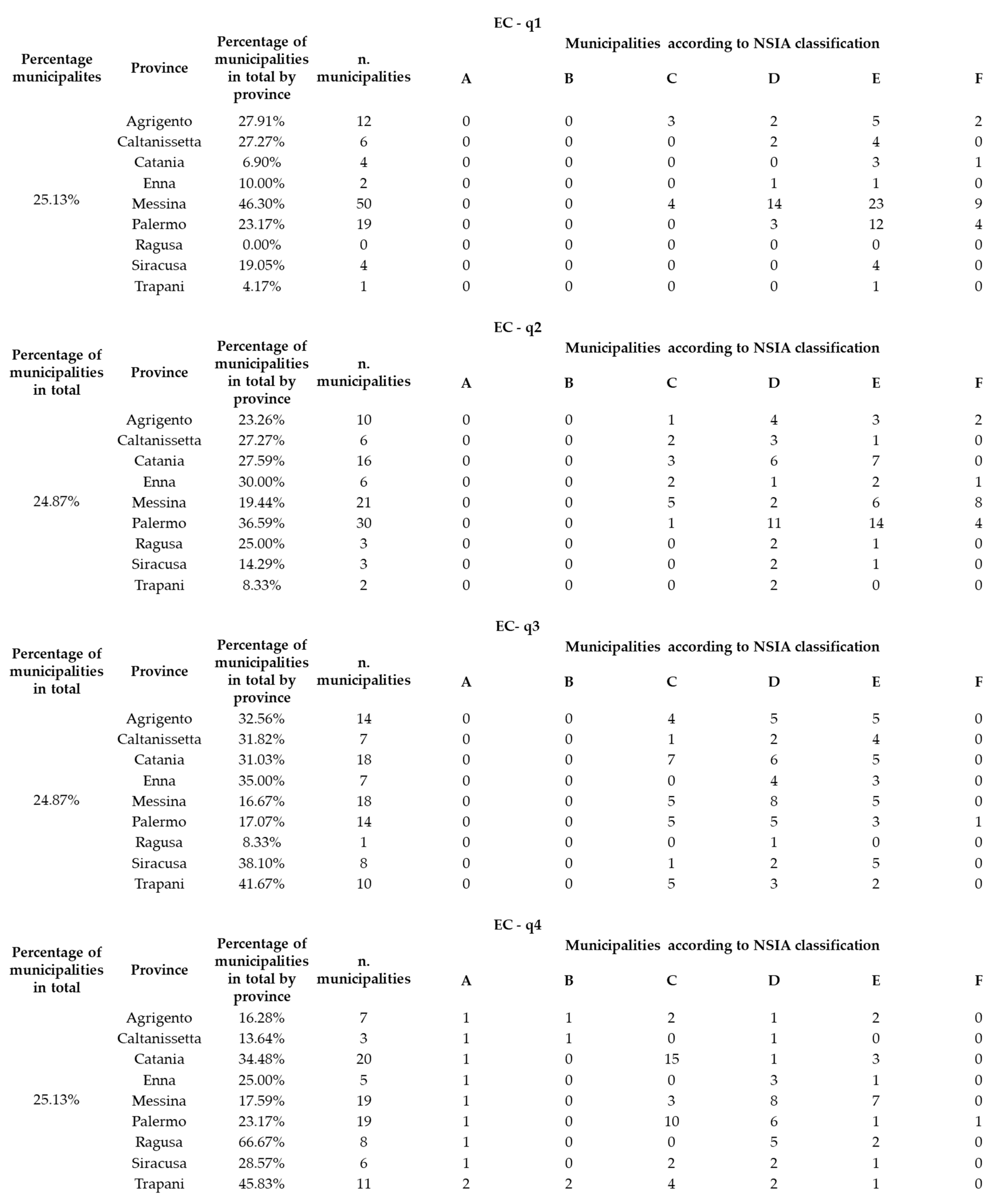

- A high concentration in coastal areas, particularly in the provinces of Catania, Palermo, Ragusa, Syracuse and Trapani.

- A medium and low concentration in inner areas.

- A high percentage of municipalities with a low level in the province of Agrigento.

- Approximately one third of municipalities with a high level fall within the province of Catania.

- There are extensive areas with low and medium levels, mostly in inner areas.

- There is a concentration of medium-high and high levels in coastal areas.

- A high percentage of municipalities with low levels in the province of Messina.

- There are extensive areas with a low level in the southern areas.

- There are extensive areas with a medium-high level in the central areas.

- There are extensive areas with a high or medium-high level in the eastern and western areas.

- A high percentage of municipalities with a low level in the province of Caltanissetta.

- A high percentage of municipalities with a high level in the province of Syracuse.

- The areas most exposed to environmental risk are in northern and eastern Sicily.

- The areas least exposed to risk in central, southern and western Sicily.

- A high percentage of municipalities in the province of Enna are characterised by low environmental risk.

- One third of municipalities in the provinces of Catania, Palermo and Ragusa are characterised by high environmental risk.

- The municipalities with the highest levels of territorial capital are those located on the coast, especially in eastern Sicily, and those in the municipality of Enna.

- The municipalities characterised by low and medium levels of territorial capital are those located inner areas.

- A high percentage of municipalities in the provinces of Agrigento, Caltanissetta and Enna fall within the first quartile of the index IRCI, meaning they are characterised by a low level of territorial capital. These are the most vulnerable areas. A strategy aimed at revitalising and strengthening these areas would require significant investment.

- One third of the municipalities in the provinces of Catania, Ragusa, Syracuse and Trapani fall into the fourth quartile of the index IRCI, meaning they have a high level of territorial capital. These are the least vulnerable areas. In this case, a strategy aimed at strengthening these areas would require less investment.

- A low level of infrastructure capital.

- A fairly similar level of human and economic capital.

- Some minor differences in urban and environmental capital.

- More marked differences in natural capital.

- There is greater natural capital in the NSIA areas of Bronte, Madonie, Nebrodi and Val di Simeto.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| NSIA 2014–2020 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Calatino | E—Peripheral | Caltagirone | 383.37 | 36,241 |

| Calatino | E—Peripheral | Grammichele | 31.02 | 12,561 |

| Calatino | D—Intermediate | Licodia Eubea | 112.45 | 2794 |

| Calatino | E—Peripheral | Mineo | 246.32 | 4991 |

| Calatino | F—Ultra-peripheral | Mirabella Imbaccari | 15.30 | 4282 |

| Calatino | E—Peripheral | San Cono | 6.63 | 2431 |

| Calatino | E—Peripheral | San Michele di Ganzaria | 25.81 | 2965 |

| Calatino | E—Peripheral | Vizzini | 126.75 | 5772 |

| NSIA 2021–2027 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Corleone | F—Ultra-peripheral | Bisacquino | 64.97 | 4203 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Campofelice di Fitalia | 35.29 | 473 |

| Corleone | F—Ultra-peripheral | Campofiorito | 22.35 | 1181 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Castronovo di Sicilia | 201.06 | 2880 |

| Corleone | F—Ultra-peripheral | Chiusa Sclafani | 57.40 | 2611 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Ciminna | 56.84 | 3485 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Contessa Entellina | 136.40 | 1536 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Corleone | 228.69 | 10,580 |

| Corleone | F—Ultra-peripheral | Giuliana | 23.64 | 1730 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Godrano | 39.27 | 1087 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Lercara Friddi | 37.27 | 6340 |

| Corleone | F—Ultra-peripheral | Palazzo Adriano | 129.25 | 1863 |

| Corleone | F—Ultra-peripheral | Prizzi | 95.03 | 4342 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Roccamena | 33.32 | 1388 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Roccapalumba | 31.41 | 2298 |

| Corleone | E—Peripheral | Vicari | 85.74 | 2484 |

| NSIA 2021–2027 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Bronte | F—Ultra-peripheral | Cesarò | 215.75 | 2212 |

| Bronte | E—Peripheral | Francavilla di Sicilia | 82.11 | 3636 |

| Bronte | F—Ultra-peripheral | Malvagna | 6.90 | 649 |

| Bronte | F—Ultra-peripheral | Moio Alcantara | 8.76 | 664 |

| Bronte | E—Peripheral | Motta Camastra | 25.29 | 804 |

| Bronte | F—Ultra-peripheral | Roccella Valdemone | 40.98 | 583 |

| Bronte | F—Ultra-peripheral | Santa Domenica Vittoria | 19.98 | 871 |

| Bronte | F—Ultra-peripheral | San Teodoro | 13.90 | 1260 |

| Bronte | E—Peripheral | Bronte | 250.01 | 18,327 |

| Bronte | F—Ultra-peripheral | Castiglione di Sicilia | 120.41 | 2969 |

| Bronte | E—Peripheral | Maletto | 40.88 | 3613 |

| Bronte | F—Ultra-peripheral | Randazzo | 204.84 | 10,324 |

| Bronte | F—Ultra-peripheral | Maniace | 35.87 | 3739 |

| NSIA 2014–2020 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Madonie | F—Ultra-peripheral | Alcara li Fusi | 62.93 | 1763 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Caronia | 227.26 | 3097 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Castel di Lucio | 28.78 | 1206 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Castell’Umberto | 11.43 | 2872 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Frazzanò | 7.00 | 601 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Galati Mamertino | 39.31 | 2361 |

| Madonie | F—Ultra-peripheral | Longi | 42.11 | 1348 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Militello Rosmarino | 29.54 | 1197 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Mirto | 9.27 | 913 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Mistretta | 127.47 | 4434 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Motta d’Affermo | 14.58 | 670 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Naso | 36.74 | 3523 |

| Madonie | D—Intermediate | Pettineo | 30.62 | 1240 |

| Madonie | D—Intermediate | Reitano | 14.12 | 733 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | San Fratello | 67.63 | 3350 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | San Marco d’Alunzio | 26.14 | 1830 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | San Salvatore di Fitalia | 15.00 | 1178 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Sant’Agata di Militello | 33.98 | 11,989 |

| Madonie | D—Intermediate | Santo Stefano di Camastra | 21.92 | 4416 |

| Madonie | E—Peripheral | Tortorici | 70.50 | 5908 |

| Madonie | D—Intermediate | Tusa | 41.07 | 2663 |

| NSIA 2021–2027 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Mussomeli | E—Peripheral | Cammarata | 192.03 | 5930 |

| Mussomeli | D—Intermediate | Casteltermini | 99.51 | 7473 |

| Mussomeli | E—Peripheral | San Giovanni Gemini | 26.30 | 7590 |

| Mussomeli | D—Intermediate | Acquaviva Platani | 14.72 | 891 |

| Mussomeli | D—Intermediate | Bompensiere | 19.74 | 522 |

| Mussomeli | D—Intermediate | Campofranco | 36.06 | 2758 |

| Mussomeli | E—Peripheral | Marianopoli | 12.96 | 1669 |

| Mussomeli | E—Peripheral | Mussomeli | 163.90 | 10,059 |

| Mussomeli | D—Intermediate | Milena | 24.56 | 2777 |

| Mussomeli | D—Intermediate | Montedoro | 14.14 | 1418 |

| Mussomeli | D—Intermediate | Sutera | 35.55 | 1234 |

| NSIA 2014–2020 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Nebrodi | F—Ultra-peripheral | Alcara li Fusi | 62.9346 | 1763 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Caronia | 227.2587 | 3097 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Castel di Lucio | 28.7781 | 1206 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Castell’Umberto | 11.4282 | 2872 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Frazzanò | 6.9981 | 601 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Galati Mamertino | 39.3108 | 2361 |

| Nebrodi | F—Ultra-peripheral | Longi | 42.1099 | 1348 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Militello Rosmarino | 29.5356 | 1197 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Mirto | 9.2692 | 913 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Mistretta | 127.4678 | 4434 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Motta d’Affermo | 14.5764 | 670 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Naso | 36.7367 | 3523 |

| Nebrodi | D—Intermediate | Pettineo | 30.6164 | 1240 |

| Nebrodi | D—Intermediate | Reitano | 14.1173 | 733 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | San Fratello | 67.6292 | 3350 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | San Marco d’Alunzio | 26.1407 | 1830 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | San Salvatore di Fitalia | 14.9963 | 1178 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Sant’Agata di Militello | 33.9764 | 11,989 |

| Nebrodi | D—Intermediate | Santo Stefano di Camastra | 21.9173 | 4416 |

| Nebrodi | E—Peripheral | Tortorici | 70.5008 | 5908 |

| Nebrodi | D—Intermediate | Tusa | 41.0737 | 2663 |

| NSIA 2021–2027 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Palagonia | E—Peripheral | Castel di Iudica | 14.14 | 4352 |

| Palagonia | E—Peripheral | Militello in Val di Catania | 62.14 | 6792 |

| Palagonia | E—Peripheral | Palagonia | 57.66 | 15,805 |

| Palagonia | E—Peripheral | Raddusa | 23.32 | 2875 |

| Palagonia | E—Peripheral | Ramacca | 305.38 | 10,377 |

| Palagonia | D—Intermediate | Scordia | 24.26 | 16,296 |

| NSIA 2021–2027 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | E—Peripheral | Alì | 16.69 | 702 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | F—Ultra-peripheral | Antillo | 43.4 | 844 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | E—Peripheral | Casalvecchio Siculo | 33.37 | 749 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | E—Peripheral | Fiumedinisi | 35.99 | 1294 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | E—Peripheral | Forza d’Agrò | 11.18 | 883 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | D—Intermediate | Furci Siculo | 17.86 | 3205 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | E—Peripheral | Limina | 9.81 | 735 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | E—Peripheral | Mandanici | 11.65 | 557 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | D—Intermediate | Nizza di Sicilia | 13.18 | 3518 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | D—Intermediate | Pagliara | 14.57 | 1097 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | E—Peripheral | Roccafiorita | 1.14 | 182 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | D—Intermediate | Roccalumera | 8.77 | 3953 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | E—Peripheral | Sant’Alessio Siculo | 6.17 | 1488 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | D—Intermediate | Santa Teresa di Riva | 8.13 | 9271 |

| Santa Teresa di Riva | E—Peripheral | Savoca | 8.80 | 1660 |

| NSIA 2014–2020 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Terre Sicane | E—Peripheral | Alessandria della Rocca | 62.2395 | 2567 |

| Terre Sicane | F—Ultra-peripheral | Bivona | 88.5732 | 3298 |

| Terre Sicane | E—Peripheral | Burgio | 42.2307 | 2532 |

| Terre Sicane | E—Peripheral | Calamonaci | 32.8901 | 1203 |

| Terre Sicane | D—Intermediate | Cattolica Eraclea | 62.1638 | 3364 |

| Terre Sicane | E—Peripheral | Cianciana | 38.0815 | 3177 |

| Terre Sicane | F—Ultra-peripheral | Lucca Sicula | 18.632 | 1730 |

| Terre Sicane | D—Intermediate | Montallegro | 27.4124 | 2385 |

| Terre Sicane | E—Peripheral | Ribera | 118.521 | 18,058 |

| Terre Sicane | E—Peripheral | San Biagio Platani | 42.6663 | 2946 |

| Terre Sicane | F—Ultra-peripheral | Santo Stefano Quisquina | 85.5183 | 4216 |

| Terre Sicane | E—Peripheral | Villafranca Sicula | 17.6292 | 1358 |

| NSIA 2021–2027 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Troina | E—Peripheral | Agira | 163.11 | 7756 |

| Troina | E—Peripheral | Assoro | 111.50 | 4892 |

| Troina | D—Intermediate | Calascibetta | 88.17 | 4169 |

| Troina | F—Ultra-peripheral | Cerami | 94.87 | 1859 |

| Troina | D—Intermediate | Catenanuova | 11.17 | 4519 |

| Troina | E—Peripheral | Gagliano Castelferrato | 56 | 3368 |

| Troina | E—Peripheral | Leonforte | 84.09 | 12,583 |

| Troina | F—Ultra-peripheral | Nicosia | 217.87 | 12,947 |

| Troina | E—Peripheral | Nissoria | 61.62 | 2849 |

| Troina | F—Ultra-peripheral | Sperlinga | 58.76 | 691 |

| Troina | F—Ultra-peripheral | Troina | 166.95 | 8699 |

| Troina | E—Peripheral | Regalbuto | 169.27 | 6830 |

| Troina | E—Peripheral | Valguarnera Caropepe | 9.32 | 7163 |

| Troina | D—Intermediate | Villarosa | 55.01 | 4496 |

| NSIA 2014–2020 | NSIA-2020 | Municipalities | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) |

| Valle del Simeto | E—Peripheral | Adrano | 83.2208 | 33,926 |

| Valle del Simeto | D—Intermediate | Biancavilla | 70.2753 | 22,987 |

| Valle del Simeto | E—Peripheral | Centuripe | 174.1946 | 5172 |

Appendix B

References

- Trovato, M.R.; Nasca, L.; Giuffrida, S.; Ventura, V. Centre Versus Periphery. Territorial Imbalance from Perspectives of the Multiple Capital Dimensions. In Networks, Markets & People, Proceedings of the NMP 2024, Reggio Calabria, Italy, 22–24 May; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Calabrò, F., Madureira, L., Morabito, F.C., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R.; Strigari, A.; Napoli, G. Houses for One Euro” and the Territory. Some Estimation Issues for the “Geographic Debt” Reduction. In New Metropolitan Perspectives, Proceedings of the NMP 2020, Reggio Calabria, Italy, 18–23 May 2020; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 178, pp. 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halás, M.; Klapka, P.; Tonev, P. A Contribution to Human Geographical Regionalisation of the Czech Republic at the Mezzo Level. In Proceedings of the 17th International Colloquium on Regional Sciences, Hustopece, Czech Republic, 18–20 June 2014; Klimova, V., Zitek, V., Eds.; Masarykova University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2014; pp. 715–721. [Google Scholar]

- Copus, A.; de Lima, P. Territorial Cohesion in Rural Europe: The Relational Turn in Rural Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibert, T. The Peripheralization of Rural Areas in Post- socialist Central Europe: A Case of Fragmenting Development? Lessons from Rural Hungary. In Peripheralization; Fischer-Tahir, A., Naumann, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, M.; Reichert-Schick, A. Infrastructure and Peripheralization: Empirical Evidence from North-Eastern Germany. In Peripheralization; Fischer-Tahir, A., Naumann, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürk, T. Voices From the Margin: The Stigmatization Process as an Effect of Socio-Spatial Peripheralization in Small-Town Germany. In Peripheralization; Fischer-Tahir, A., Naumann, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlíček, T.; Chromý, P. Contribution to the Theory of Polarized Development of a Territory, with a Special Attention Paid to Peripheral Regions. Geografie 2001, 106, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, M. Regional Inequalities in the Enlarged Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2003, 13, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzini, M.; Pianta, M. Explaining Inequality; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 1317561023. [Google Scholar]

- Naumann, M.; Fischer-Tahir, A. Peripheralization: The Making of Spatial Dependencies and Social Injustice; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 3531190180. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Cities in a World Economy; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781506362618. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Napoli, G.; Trovato, M.R. Industrial Areas and the City. Equalization and Compensation in a Value-Oriented Allocation Pattern. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2016, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2016, Beijing, China, 4–7 July 2016; Lecture Notes in Computer, Science; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Torre, C.M., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Stankova, E., Wang, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppido, S.; Ragozino, S.; Espostio De Vita, G. Peripheral, Marginal, or Non-Core Areas? Setting the Context to Deal with Territorial Inequalities through a Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 0674599225. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON. Policy Brief: Shrinking Rural Regions in Europe. Towards Smart and Innovative Approaches to Regional Development Challenges in Depopulating Rural Regions. 2017. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/rural-shrinking (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- Martinez-Fernandez, C.; Audirac, I.; Fol, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 33, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, P.; Haslam, D.; Kil, W.; Prigge, W.; Ronneberger, K.; Thomas Sugrue, T.; Douglas, S. Shrinking Cities; Hatje Cantz Verlag: Ostfildern, Germany, 2005; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Oswalt, P.; Alsop, W.; Baur, R. Shrinking Cities 2; Hatje Cantz Verlag: Ostfildern, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON; University of Geneva. European Perspective on Specific Types of Territories. Applied Research 2013/1/12. Final Report|Version 20/12/2012. 2012. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/GEOSPECS_Final_Report_v8___revised_version.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- ESPON. PROFECY—Processes, Features and Cycles of Inner Peripheries in Europe. Applied Research. Final Report. Version 07/12/2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/D5%20Final%20Report%20PROFECY.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Bernt, M.; Colini, L. Exclusion, Marginalization and Peripheralization. Work. Pap. 2013, 49, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kinossian, N. Planning Strategies and Practices in Non-Core Regions: A Critical Response. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 26, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Nasca, L.; Giuffrida, S.; Ventura, V. Convergences Versus Gaps. Capital Axiology as a Cognitive Pattern of Territorial Fragility. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2025 Workshops, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2025, Istanbul, Turkey, 30 June—3 July 2025; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Garau, C., Karaca, Y., Faginas Lago, M.N., Scorza, F., Brage, A.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.R. Regional Development Policy: A Case of Venezuela; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966; ISBN 9780262060134. [Google Scholar]

- Tiebout, C.M. A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures. J. Political Econ. 1956, 64, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzhaf, H.S.; Walsh, R.P. Do People Vote with Their Feet? An Empirical Test of Tiebout’s Mechanism. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 843–863. Available online: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.98.3.843 (accessed on 2 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hachadoorian, L. Homogeneity tests of Tiebout sorting: A case study at the interface of city and suburb. Urban Sci. 2015, 53, 1000–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, P.; Ferreira, F.; McMillan, R. A Unified Framework for Measuring Preferences for Schools and Neighborhoods; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w13236 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Hanlon, B.; Short, J.R.; Vicino, T.J. Cities and Suburbs: New Metropolitan Realities in the US; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bickers, K.; Engstrom, R.N. Tiebout sorting in metropolitan areas. Rev. Policy Res. 2006, 23, 1181–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkila, E.J. Are municipalities Tieboutian clubs? Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1996, 26, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.; Hay, D. Growth Centres in the European Urban System; Heinemann: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen, L.H.; Paelinck, J.H.P. The future of large towns. Environ. Plan. A 1979, 11, 10951104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, L.H.; Scimemi, G. Theoretical issues in urban dynamics. In Dynamics of Urban Development; Klaassen, L.H., Molle, W.T.M., Paelinck, J.H.P., Eds.; Gower: Aldershot, UK, 1981; p. 828. [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen, L.H.; Bourdrez, J.A.; Vollmuller, J. Transport and Reurbanization; Gower: Aldershot, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, L.; van der Meer, J. Urban Change in the Netherlands. In Dynamics of Urban Development; Klaassen, L.H., Molle, W.T.M., Paelinck, J.H.P., Eds.; Gower: Aldershot, UK, 1981; p. 137169. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, P.C.; Hay, D.G. Urban Problems in Western Europa: An Economic Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Aydalot, P. Economie Régionale et Urbaine; Economica: Paris, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, L.; Klaassen, L.H. The contagiouness of urban decline. In Spatial Cycles; van den Berg, L., Burns, L.S., Klaassen, L.H., Eds.; Gower: Aldershot, UK, 1987; p. 8894. [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima, T. Is disurbanisation foreseeable in Japan? A comparison between US and Japanese urbanisation processes. In Spatial Cycles; van den Berg, L., Burns, L.S., Klaassen, L.H., Eds.; Gower: Aldershot, UK, 1987; p. 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, M. Peripheralization: Theoretical Concepts Explaining Socio-Spatial Inequalities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Copus, A.; Mantino, F.; Noguera, J. Inner Peripheries: An Oxymoron or a Real Challenge for Territorial Cohesion? Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2017, 7, 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- Spiekermann, K.; Neubauer, J. European Accessibility and Peripherality: Concepts, Models and Indicators; Nordregio: Stockholm, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Tahir, A.; Naumann, M. Introduction: Peripheralization as the Social Production of Spatial Dependencies and Injustice. In Peripheralization; Fischer-Tahir, A., Naumann, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copus, A. From Core-Periphery to Polycentric Development: Concepts of Spatial and Aspatial Peripherality. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, A.; Rallet, A. Proximity and localization. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito De Vita, G.; Marchigiani, E.; Camilla, P. Sui Margini: Una Mappatura Di Aree Interne e Dintorni. BDC 2021, 21, 183–216. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Single European Act. Official Journal of the European Communities, No L169/1, 29.06.87. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:11986U/TXT (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- European Parliament. Treaty of Lisbon. Official Journal of the European Communities, C306, Vo. 50 17-12-2007. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=oj:JOC_2007_306_R_TOC (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- European Commission; Christophersen, H. Guide to the Reform of the Community’s Structural Funds, Publications Office. 1989. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/80ad8eda-9206-4a51-9814-be85d4da4886 (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Commission of the European Communities. Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion Turning Territorial Diversity into Strength, Brussels, 6.10.2008 COM(2008) 616 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2008:0616:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- European Parliament. Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion and Debate on the Future Reform of the Cohesion Policy. Official Journal of the European Union, C 117 E/65, 24-03-2009. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d986b0c0-e58d-4ced-8bba-083a28d00ffa/language-it (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- European Parliament. The treaty on the functioning of the Europea Union. Official EN Journal of the European Union, C 326/47, 26-10-2012. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT:en:PDF (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Piattoni, S.; Polverari, L. Handbook on Cohesion Policy in the EU; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham/Camberley, UK, 2016; ISBN 1784715670. [Google Scholar]

- Viesti, G. The European Regional Development Policies. In The History of the European Union: Constructing Utopia; Amato, G., Moavero-Milanesi, E., Pasquino, G., Reichlin, L., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2019; pp. 385–400. ISBN 150991742X. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Government. Decree-Law No. 77 of 31 May 2021. Governance of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan and Initial Measures to Strengthen Administrative Structures and Accelerate and Streamline Procedures. (Clause 40% PNRR Southern Italy Re-sources), Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2021/05/31/21G00087/SG (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Italian Government. Law No. 101 of 1 July 2021. Conversion into Law, with Amendments, of Decree-Law No 59 of 6 May 2021 on Urgent Measures Relating to the Supplementary Fund for the National Recovery and Resilience Plan and Other Urgent Investment Measures. (Clause 40% PNRR Southern Italy resources), Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2021/07/06/21G00111/SG (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Italian Government. Decree- Law the 6 August 2021. Allocation of Financial Resources Provided for the Implementation of the Interventions of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NPRR) and Allocation of Targets and Objectives by Six-Monthly Reporting Deadlines. Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2021/09/24/21A05556/sg (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Italian Government. Decree-Law No. 13 of 24 February 2023. Urgent Provisions for the Implementation of the National Plan for Recovery and Resilience (NPRR) and the National Plan for Complementary Investments to the NPRR (PNC), as Well as for the Implementation of Cohesion Policies and the Common Agricultural Policy. Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2023/02/24/23G00022/SG (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Comunicazione Della Commissione Europea. EUROPA 2020 Una Strategia per una Crescita Intelligente, Sostenibile e Inclusiva, Bruxelles, 3.3.2010 COM(2010) 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:2020:FIN:IT:PDF (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Commissione Europea. Rural Vision. 2022. Available online: https://rural-vision.europa.eu/index_it (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Italian Government. Law No. 178 of 30 December 2020. State Budget for the 2021 Financial Year and Multi-Year Budget for the Three-Year Period 2021-2023. Rome, Italy 2021. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/vediMenuHTML?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2020-12-30&atto.codiceRedazionale=20G00202&tipoSerie=serie_generale&tipoVigenza=originario (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Prime Ministerial. Decree 30 November 2021. Countering Deindustrialisation Fund, Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/01/14/22A00106/SG (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Prime Ministerial. Decree 30 September 2021. Marginal Municipalities, Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2021/12/14/21A07265/sg (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Prime Ministerial. Decree 24 September 2020. Inner Areas Municipalities, Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/12/04/20A06526/sg (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Agency for Territorial Cohesion. National Strategy for Inner Areas. Available online: https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/strategia-nazionale-aree-interne/la-selezione-delle-aree/ (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Agenzia per la Coesione Territoriale. PNRR Missione 5, Componente 3, Investimento 1.1.1. 2022. Available online: https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/bandi-agenzia/avviso-pubblico-per-la-presentazione-di-proposte-di-intervento-per-servizi-e-infrastrutture-sociali-di-comunita-da-finanziare-nellambito-del-pnrr/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Dall’Erba, S.; Le Gallo, J. Regional convergence and the impact of European structural funds 1989–1999: A spatial econometric analysis. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2008, 87, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.O.; Egger, P.H.; Von Ehrlich, M. Too much of a good thing? On the growth effects of the EU’s regional policy. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2012, 56, 648–668. [Google Scholar]

- Fratesi, U. Impact assessment of European cohesion policy: Theoretical and empirical issues. In Handbook on Cohesion Policy in the EU; Piattoni, S., Polverari, L., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 443–460. ISBN 978-1-78471-566-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fratesi, U.; Perucca, G. EU Regional Policy Effectiveness and the Role of Territorial Capital. In Regeneration of the Built Environment from a Circular Economy Perspective; Research for Development; Della Torre, S., Cattaneo, S., Lenzi, C., Zanelli, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Nasca, L. An Axiology of Weak Areas: The Estimation of an Index of Abandonment for the Definition of a Cognitive Tool to Support the Enhancement of Inland Areas in Sicily. Land 2022, 11, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R. Regional competitiveness: Towards a concept of territorial capital. In Modelling Regional Scenarios for the Enlarged Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 33–47. ISBN 978-3-540-74736-9. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R. Why Foundations …? Evaluation as Civil Commitment. In Science of Valuations; Green Energy and Technology; Giuffrida, S., Trovato, M.R., Rosato, P., Fattinnanzi, E., Oppio, A., Chiodo, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolando, D.; Barreca, A.; Rebaudengo, M. The SAVV+P method: Integrating qualitative and quantitative analyses to evaluate the territorial potential. In Proceedings of the ICCSA 2023, Athens, Greece, 3–6 July 2023; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Garau, C., Scorza, F., Karaca, Y., Torre, M.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14106, pp. 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolando, D.; Barreca, A.; Malavasi, G.; Rebaudengo, M. Data-Driven AI Approach to Address Territorial Strategies. Why Investing in Agri-Food Sector to Enhance the Valsesia Inner Area. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2025 Workshops, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2025, Istanbul, Turkey, 30 June–3 July 2025; Lecture Notes in Computer, Science; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Garau, C., Scorza, F., Karaca, Y., Torre, M.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, C. Resistance to Sardinia’s Guarded Capacity: Multicriterial Mapping for Strategies and Valorization of Abandoned Places. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2024 Workshops, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2024, Hanoi, Vietnam, 1–4 July 2024; Lecture Notes in Computer, Science; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Garau, C., Taniar, D., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Faginas Lago, M.N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düzgün, E. The Poverty of “Peripheralization”: Re-conceptualizing the Peripheral Space. In Peripheralization; Fischer-Tahir, A., Naumann, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norese, M.F.; Rolando, D.; Rocco, C. DIKEDOC: A multicriteria methodology to organise and communicate knowledge. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 325, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R. A multi-criteria approach to support the retraining plan of the Biancavilla’s old town. In New Metropolitan Perspectives, Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, Proceedings of the 3rd International New Metropolitan Perspectives, Local Knowledge and Innovation Dynamics Towards Territory Attractiveness Through the Implementation of Horizon/Europe2020/Agenda2030, Reggio Calabria, Italy, 22–25 May 2018; Bevilacqua, C., Calabro, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 101, pp. 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Shi, X.; He, D.; Guo, B.; Li, Z.; Shi, X. Designing a spatial pattern to rebalance the orientation of development and protection in Wuhan. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Erbaugh, J.T.; Fajardo, P.; Lu, L.; Molnár, I.; Papp, D.; Robinson, B.E.; Austin, K.G.; Castro, M.; Cheng, S.H.; et al. Global evidence of human well-being and biodiversity impacts of natural climate solutions. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V. From stakeholders analysis to cognitive mapping and Multi-Attribute Value Theory: An integrated approach for policy support. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 253, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comino, E.; Ferretti, V. Indicators-based spatial SWOT analysis: Supporting the strategic planning and management of complex territorial systems. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 1104–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.E.; Wise Bender, H.; Shields, D.J. Stakeholder objectives for public lands: Rankings of forest management alternatives. J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 58, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G. The network governance of urban renewal: A comparative analysis of two cities in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V.; Comino, E. An integrated framework to assess complex cultural and natural heritage systems with Multi-Attribute Value Theory. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, A.; Ming, X.; Riaz Raja, M.; Tetteh, A.; Hussain, A.; Answer, M.; Ali, N. An Innovative Approach in Decision-making Environments: Assessing Performance by Applying Multi-attribute Value Theory (MAVT). Asian J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2015, 3, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, V.; Bottero, M.; Mondini, G. From Indicators to Composite Indexes: An Application of the Multi-Attribute Value Theory for Assessing Sustainability. Adv. Eng. Forum 2015, 11, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, J.U. A Multiplicative Approach in Multiattribute Value Theory: The Aggregated Performance Factor Model. In Decision Analysis and Multiple Criteria Decision Making: Proceedings of the Joint GOR-DASIG Conference; Shaker: Aachen, Germany, 2013; pp. 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hajkowicz, S. Multi-attributed environmental index construction. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 57, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gibari, S.; Gómez, T.; Ruiz, F. Building composite indicators using multicriteria methods: A review. J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 89, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V.; Bottero, M.; Mondini, G. Decision making and cultural heritage: An application of the Multi-Attribute Value Theory for the reuse of historical building. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolaro Monsù, A.; Cappello, C. The Realms of Abandonment: Measures and Interpretations of Landscape Value/Risk in Northern Sardinia (Italy). Land 2023, 12, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, F.; Tajani, F.; Guarini, M.R.; Ranieri, R. A Sensitivity Index to Perform the Territorial Sustainability in Uncertain Decision-Making Conditions. Land 2023, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M. Thinking through complex values. In Making Strategies in Spatial Planning; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R.; Ventura, V.; Cappello, C.; Nasca, L. Concepts and Tools for the Emergence of the Axiological Subject in the Prospect of Territorial Rebalancing. In Networks, Markets & People, Proceedings of the NMP 2024, Reggio Calabria, Italy, 22–24 May; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Calabrò, F., Madureira, L., Morabito, F.C., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S.; Collesano, G.; Nasca, L.; Gagliano, F. People, Property and Territory: Valuation Perspectives and Economic Prospects for the Trazzera Regional Property Reuse in Sicily. Land 2023, 12, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. Regional Competitiveness and Territorial Capital: A Conceptual Approach and Empirical Evidence from the European Union. Reg. Stud. 2012, 47, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Territorial Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R.; Caragliu, A.; Perucca, G. Draft Version. Territorial capital, relational and human capital. Il CapitaleTerritoriale: Scenari Quali-Quantitativi Di Superamento Della Crisi Economica e Finanziaria Per Le Province Italiane, PRIN. 2011. Available online: https://www.grupposervizioambiente.it/aisre/pendrive2011/pendrive/Paper/Camagni_Caragliu_Perucca.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Crescenzi, R.; Gagliardi, L.; Percoco, M. Social capital and the innovative performance of Italian provinces. Environ. Plan A 2013, 45, 908–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Do institutions matter for regional development? Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, S.; Tamásy, C.; Mathys, A.; Heinz, V. Sustainability and regions: Sustainability assessment in regional perspective. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2016, 7, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tödtling., F. Endogenuos approaches to local an regional development policy. In Handbook of Local and Regional Development; Pike, A., Rodriguez-Pose, A., Tomaney, J., Eds.; Routlege: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 333–334. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Barquero, A.; Rodriguez-Cohard, J.C. Local development in a global world: Challenges and opportunities. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2018, 11, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri. Dipartimento per le Politiche di Coesione. Nucleo di Valutazione e Analisi per la Programmazione. Criteri per la Selezione delle Aree Interne da Sostenere nel Ciclo 2021–2027. Roma, Italy. 2022. Available online: https://lineaamica.gov.it/docs/default-source/focus/criteri-aree-interne.pdf?sfvrsn=c61e29a0_4 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Nasca, L.; Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R. Value and Quality in the Dialectics between Human and Urban Capital of the City Networks on the Land District Scale. Land 2022, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governo Italiano, Presidenza del Consiglio del Consiglio dei Ministri. Urban Index. Indicatori per le Politiche Urbane. Available online: https://www.pnmetroplus.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/presentazione_urbanindex_step7.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Trovato, M.R.; Ventura, V.; Lanzafame, M.; Giuffrida, S.; Nasca, L. Seismic–Energy Retrofit as Information-Value: Axiological Programming for the Ecological Transition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R.; Circo, C.; Ventura, V.; Giuffrè, M.; Macca, V. Seismic Vulnerability and Old Towns. A Cost-Based Programming Model. Geosciences 2019, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Carocci, C.; Circo, C.; Giuffrè, M.; Trovato, M.R.; Ventura, V. Axiological Strategies in the Old Towns Seismic Vulnerability Mitigation Planning; Valori e Valutazioni; Dei Tipografia del Genio Civile: Rome, Italy, 2020; pp. 99–106. ISSN 20362404. [Google Scholar]

- Minioto, C.; Martinico, F.; Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S. Data and Values: Axiological Interpretations of Building Sprawl Landscape Risk in the Rural Territory of Noto (Italy). Land 2023, 12, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R. Axiology of Urban Quality. The City as a Functionings System. In Science of Valuations; Green Energy and Technology; Giuffrida, S., Trovato, M.R., Rosato, P., Fattinnanzi, E., Oppio, A., Chiodo, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R. Human Capital Approach in the Economic Assessment of Interventions for the Reduction of Seismic Vulnerability in Historic Centres. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R.; Giannelli, A. Semiotic-Sociological Textures of Landscape Values. Assessments in Urban-Coastal Areas. In Information and Communication Technologies in Modern Agricultural Development, Proceedings of the 8th International Conference, HAICTA 2017, Chania, Greece, 21–24 September 2017; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Gagliano, F.; Trovato, M.R. Land as Information. A Multidimensional Valuation Approach for Slow Mobility Planning. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies in Agriculture, Food and Environment (HAICTA 2015), Kavala, Greece, 17–20 September 2015; Andreopoulou, Z., Bochtis, D., Eds.; Volume 1498, pp. 879–891, ISSN 16130073. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R.; Falzone, M. The Information Value for Territorial and Economic Sustainability in the Enhancement of the Water Management Process. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2017, Proceedings of the 17th International Conference, Trieste, Italy, 3–6 July 2017; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 575–590. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R. A Semiotic Approach to the Landscape Accounting and Assessment. An Application to the Urban-Coastal Areas. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies in Agriculture, Food and Environment, HAICTA 2017, Chania, Greece, 21–24 September 2017; Salampasis, M., Theodoridis, A., Bournaris, T., Eds.; CEUR Workshop Proceedings: Aachen, Germany, 2017; pp. 696–708, ISSN 16130073. [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, R.; Raiffa, H. Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Trade-Offs; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Von Winterfeldt, D.; Edwards, W. Decision Analysis and Behavioral Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, V.; Stewart, T. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: An Integrated Approach; Kluwer Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, S.; Ehrgott, M.; Figueira, J. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Beinat, E. Value Functions for Environmental Management; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, J.; An, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L. Using fuzzy theory and information entropy for water quality assessment in Three Gorges region, China. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 2517–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.-H.; Yun, Y.; Sun, J.-N. Entropy method for determination of weight of evaluating indicators in fuzzy synthetic evaluation for water quality assessment. J. Environ. Sci. 2006, 18, 1020–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.W.; Chong, X.; Bao, Z.F.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, S.H. Fuzzy comprehensive assessment method based on the entropy weight method and its application in the water environmental safety evaluation of the heshangshan drinking water source area. Three Gorges Reserv. Area 2017, 9, 329. [Google Scholar]

- Taheriyoun, M.; Karamouz, M.; Baghvand, A. Development of an entropy-based fuzzy eutrophication index for reservoir water quality evaluation. Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2010, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Xu, J.; Chen, X. nformation-Theoretic-Entropy Based Weight Aggregation Method in Multiple-Attribute Group Decision-Making. Entropy 2016, 18, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Winterfeldt, D.; Fischer, G.W. Multi-Attribute Utility Theory: Models and Assessment Procedures. In Utility, Probability, and Human Decision Making; Theory and Decision Library; Wendt, D., Vlek, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1975; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkenhoef, G.; Tervonen, T. Entropy-optimal weight constraint elicitation with additive multi-attribute utility models. Omega 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzengand, G.H.; Huang, J.J. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Tian, D.; Yan, F. Effectiveness of entropy weight method in decision-making. Math. Problems Eng. 2020, 2020, 3564835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, J.; Peng, L.; Zhou, X. Multiattribute Decision-Making in Wargames Leveraging the Entropy–Weight Method in Conjunction With Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Games 2024, 16, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.H.; Wu, W.Z.; Wang, L.X.; Tan, A.H. Entropy based optimal scale selection and attribute reduction in multi-scale interval-set decision tables. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cyber. 2024, 15, 3005–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, P.; Qian, H.; Chen, J. On the sensitivity of entropy weight to sample statistics in assessing water quality: Statistical analysis based on large stochastic samples. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 2185–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Qian, B.; Xiao, X. Geo-accumulation vector model for evaluating the heavy metal pollution in the sediments of Western Dongting Lake. J. Hydrol. 2019, 567, 112–124. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Li, L.Y.; Lei, K.; Wang, L.; Zhai, Y.; Zhai, M. Water quality assessment of Wei River, China using fuzzy synthetic evaluation. Environ. Earth Sci. 2010, 60, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, K.; Chen, X. Hydrological effects of water reservoirs on hydrological processes in the East River (China) basin: Complexity evaluations based on the multi-scale entropy analysis. Hydrol. Process. 2012, 26, 3253–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoyo, A.; Muñoz, R.; Gutiérrez, Y. Geo.IA: Artificial geo-intelligence platform to Solve Citizens problems and facilitate strategic decision making in the public administration. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Athens, Greece, 18 November 2024; Volume 3729, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Grieco, B.; Sacco, S.; Cannatella, D.; Cerreta, M. Spatial Analysis in Multi-Value Assessment for Rural Landscapes: A Comparative Study of ES, LS, and LCA Frameworks. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2025 Workshops, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2025, Istanbul, Turkey, 30 June–3 July 2025; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Garau, C., Karaca, Y., Fagina Lago, M.N., Scorsa, F., Braga, A.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Poli, G. A complex values map of marginal urban landscapes: An experiment in Naples (Italy). Int. J. Agric. Environ. Inf. Syst. 2013, 4, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Sanzaro, D. A Knowledge and Evaluation Model to Support the Conservation of Abandoned Historical Centres in Inner Areas. Heritage 2024, 7, 1618–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Gagliano, F.; Giannitrapani, E.; Marisca, C.; Napoli, G.; Trovato, M.R. Promoting Research and Landscape Experience in the Management of the Archaeological Networks. A Project-Valuation Experiment in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Laiô, S.K. Decision network: A planning tool for making multiple, linked decisions. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2011, 38, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, A.; Sundaram, D. Flexible modelling and support of interrelated decisions. Decis. Support. Syst. 2011, 46, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscia, C.; Gron, S.; Vercellino, E. Decision-Making CIA Process (DeMaCIA) to Support SNAI Strategies: The Case of Castelluccio Inferiore in Basilicata, Italy. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2025 Workshops, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2025, Istanbul, Turkey, 30 June–3 July 2025; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Garau, C., Karaca, Y., Fagina Lago, M.N., Scorsa, F., Braga, A.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajani, F.; Sica, F.; De Paola, P.; Morano, P. A networking-economic model to enhance the cultural value in small towns. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, P.; Tajani, F.; Di Liddo, F.; Amoruso, P. The public role for the effectiveness of the territorial enhancement initiatives: A case study on the redevelopment of a building in disuse in an Italian small town. Buildings 2021, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, F.; Tajani, F.; Morano, P. A Model for Sustainable Development in Territorial Production System. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 4511–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerè de la Transition Ècologique. Revitalisation des Centres-Bourges 2014. Available online: https://www.centres-bourgs.logement.gouv.fr (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Agence Nationale de la Coèsion de Territories. Action Coeur de Ville. 2018. Available online: https://agence-cohesion-territoires.gouv.fr/action-coeur-de-ville-42 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Agence Nationale de la Coèsion de Territories. Petites Villes de Demain. 2020. Available online: https://www.agence-cohesion-territoires.gouv.fr/petites-villes-de-demain-45 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Region Swisse. Swisse Spatial and Regional Development Policies and Programmes. Available online: https://regiosuisse.ch/en/swiss-spatial-and-regional-development-policies-and-programmes (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Region Swisse. Financial Instruments and Measures Within the Framework of the NRP. Available online: https://regiosuisse.ch/en/financial-instruments-and-measures-within-framework-nrp (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Gobierno de Castilla-La Mancha. Inversiòn Territorial Integrada. Estrategia para el Desarrollo de Zonas con Despoblamiento y Declive Socioeconómico en Castilla-La Mancha. 2016. Available online: https://www.castillalamancha.es/sites/default/files/documentos/pdf/20170721/folleto_informativo_iti.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Ministero de Political Territorial. Estrategia Nacional Frente al Reto Demográfico. 2019. Available online: https://www.mptfp.gob.es/portal/reto_demografico/Estrategia_Nacional.html (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Malavasi, G.; Barreca, A.; Rebaudengo, M.; Rolando, D. A stakeholder analysis to support resilient strategies in the Alta Valsesia inner area. In Proceedings of the ICCSA 2023, Athens, Greece, 3–6 July 2023; LNCS. Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Garau, C., Scorsa, F., Karaca, Y., Torre, C.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14106, pp. 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, M.; Favargiotti, S.; Lino, B.; Rolando, D. Branding4Resilience: Explorative and Collaborative Approaches for Inner Territories. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossitti, M.; Dell’Ovo, M.; Oppio, A.; Torrieri, F. The Italian National Strategy for Inner Areas (SNAI): A Critical Analysis of the Indicator Grid. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L. Community Branding and Participatory Governance: A Glocal Strategy for Heritage Enhancement. Heritage 2025, 8, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L. Revitalization of Inner and Marginal Areas: A Multi-Criteria Decision Aid Approach for Shared Development Strategies. Valori E Valutazioni 2020, 25, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Cohesion Policies for Southern Italy. OpenCoesione. Available online: https://opencoesione.gov.it/it/ (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Comuni Della NSIA Area Troina. Strategia Territoriale dell’Area Interna Troina. Caratteristiche, Fabbisogni e Identità dell’Area Interna Troina Nella Programmazione Territoriale 2021–2027 in Sicilia. Available online: https://www.regione.sicilia.it/sites/default/files/2024-11/ALL.%201%20al%20DDG%20N.%20741-2024%20AI%20TROINA.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Presidency of the Council of Ministers. Italia Domani. Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza. Catalogo Open Data. Available online: https://www.italiadomani.gov.it/it/home.html (accessed on 5 April 2024).

| Cycle 2014–2020 NSIA Areas | Tot. Municipalities | A—Pole | C—Belt | D— Intermediate | E— Peripheral | F— Ultra- Peripheral | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 NSIA Areas in 2014–2020 Cyle | 1060 | 1 | 127 | 333 | 482 | 117 | 1,938,909 | 51,205 |

| Cycle 2021–2027 NSIA Areas | Tot. Municipalities | A—Pole | C—Belt | D— Intermediate | E— Peripheral | F— Ultra- Peripheral | Tot. Population (ISTAT 2020) | Tot. Surface Area (sq.km.) |

| 67 NSIA Areas in 2014–2020 Cycle | 1105 | 1 | 148 | 358 | 482 | 116 | 2,301,499 | 54,615 |

| 56 NSIA Areas in 2021–2027 Cycle | 764 | 55 | 236 | 369 | 104 | 2,056,139 | 38,442 | |

| Minor Inland | 35 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 18 | 213,093 | 971 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trovato, M.R.; Nasca, L. Territorial Rebalancing from an Axiological Perspective: A Reaction Capacity Index of Sicily’s Inner Areas. Land 2025, 14, 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091916

Trovato MR, Nasca L. Territorial Rebalancing from an Axiological Perspective: A Reaction Capacity Index of Sicily’s Inner Areas. Land. 2025; 14(9):1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091916

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrovato, Maria Rosa, and Ludovica Nasca. 2025. "Territorial Rebalancing from an Axiological Perspective: A Reaction Capacity Index of Sicily’s Inner Areas" Land 14, no. 9: 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091916

APA StyleTrovato, M. R., & Nasca, L. (2025). Territorial Rebalancing from an Axiological Perspective: A Reaction Capacity Index of Sicily’s Inner Areas. Land, 14(9), 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091916