Abstract

Ilha de Moçambique is an island off the northern coast of Mozambique, covering an area of 1.5 km2. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1991, the island is currently under threat due to the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events caused by climate change. Cyclonic events and pluvial floods have led to the progressive degradation of buildings and are compromising the integrity of the site. Furthermore, the island’s economic and social vulnerability is also worsening. The article aims to critically review the strategic planning approaches adopted for climate adaptation on Ilha de Moçambique. The objective is to identify and assess the planning instruments implemented to protect coastal urban heritage in light of contemporary challenges. Methodologically, a literature review is conducted based on the analysis of a collection of plans dedicated to adapting to climate change and heritage preservation. The results reveal that current planning approaches remain fragmented and insufficient, reducing their practical impact. There is a notable absence of planning instruments specifically designed to integrate cultural heritage preservation with urban climate adaptation. In conclusion, although some initiatives are underway, significant gaps persist in the strategic planning framework, underscoring the urgent need for inclusive integrated and adaptive measures to safeguard the island’s urban heritage and community in the long term.

1. Introduction

Along the African coast several urban areas, considered UNESCO World Heritage Sites, are, nowadays, more vulnerable to flooding and coastal erosion phenomena [1,2,3]. These negative externalities, driven by climate change, in addition to causing physical degradation of the coastal urban assets, and especially the urban heritage, negatively impact the social and economic development of the affected urban areas.

In Africa, projections indicate that by 2100, approximately 30% of cultural heritage sites will be exposed to an extreme coastal event [4]. In fact, coastal urban heritage located on low-lying sandy coasts is more susceptible to the effects of extreme events and around 6% of UNESCO World Heritage Sites will be affected by the rise in mean sea level [5].

Ilha de Moçambique, located off the northern coast of Mozambique in Nampula Province, is the subject of this research, which focuses on the analysis of planning strategies and their impact on the territory. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991, the island features a distinctive urban dichotomy between cidade de pedra e cal (translated as “the city of stone and lime,” cidade de pedra e cal is the name by which the Portuguese-built urban settlement is still known) and cidade de macuti (translated as “the city of macuti, cidade de macuti is the name by which the vernacular settlement is known, referring to the material used for the roofs—palm tree leaves). Although their urban characteristics differ, both urban areas contribute to the definition of the island’s cultural identity. Due to its geographic location, the island is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, especially flooding and tropical cyclones [6]. The coexistence of heritage value and climate vulnerability makes Ilha de Moçambique a relevant case study for an integrated analysis of urban planning adaptation plans and strategies, with a specific focus on heritage preservation, in contexts of climate risk.

Currently, the Ilha de Moçambique territory has several operative plans and programs implemented on a sectoral basis at both national and local levels, including the “Estratégia Nacional de Adaptação e Mitigação das Alterações Climáticas (ENAMMC)” [7] (National Strategy for Adaptation and Mitigation of Climate Change); the “Plano Diretor para a Redução do Risco de Desastres (PDRRD)” [8] (Master Plan for Disaster Risk Reduction); the “Plano estratégico Nacional para Gestão do Património Cultura, Plano Estratégico de Desenvolvimento Distrital da Ilha de Moçambique (PEDD)” [9] (National Strategic Plan for Cultural Heritage Management, and the Mozambique Island District Strategic Development Plan). Each of these instruments addresses specific objectives, ranging from climate impact reductions to the enhancement and preservation of cultural heritage. However, a significant disconnection remains between climate adaptation measures and heritage preservation strategies—particularly in coastal areas, where the risks of coastal erosion, sea level rise and cyclones are more intense. This lack of coordination is evident in the absence of integrated, cross-sectoral policies that align heritage preservation with the increasing challenges posed by the intensification of extreme climate events.

Indeed, according to the study [10], there is a significant gap in the simultaneous integration of climate adaptation, urban planning and cultural heritage. Their study emphasizes the importance of incorporating projection of future climate conditions into urban planning processes, particularly with regard to the vulnerability and potential degradation of heritage sites. However, beyond the inclusion of future climate projections in planning processes, it is crucial that tangible heritage be systematically integrated into broader policy debates and into development of public strategies aimed at adapting to the impacts of extreme climate events [11].

This article aims to critically examine the planning instruments and strategic urban approaches adopted for the adaptation of cultural heritage to contemporary challenges, such as those posed by climate change, at both the national and local levels (with a focus on Ilha de Moçambique).

The research is guided by three questions: (i) How have climate adaptation policies and plans been integrated into cultural heritage preservation policies? (ii) What are the main instruments in place at national and local levels, and how can they be cataloged in terms of objectives, scales and areas of interventions? (iii) How have these instruments been implemented on Ilha de Moçambique, and what adaptive strategies have been adopted for the protection of local heritage?

The research conducted for this article is based on the hypothesis that exploring the correlation between documents focused on heritage conservation and climate adaptation plans can help clarify the interactions present in national and local regulations concerning the protection of coastal urban heritage. This hypothesis forms the basis of the literature review conducted, which seeks to evaluate the potential benefits and limitations of the strategies implemented.

Although this research is grounded in the synthesis of existing reports and plans, its methodological contribution lies in the development of a systematic, criteria-based framework that enables the explicit identification of how heritage preservation measures align with climate adaptation frameworks.

In conclusion to this article, we consider that heritage adaptation plans implemented in Mozambique often overlook the integration of climate risk assessments. We consider that regulatory instruments acknowledge inhabited physical space as the result of various social, economic, cultural and environmental interactions. This recognition is essential to ensure that planning processes are more attuned to local specificities and promote urban solutions tailored to heritage territories vulnerable to climate change. It is argued that the preservation of historical heritage is inherent to urban adaptation and requalification programs—such as the expansion of infrastructures that enable an improvement in the quality of life of the inhabitants of the cidade de pedra e cal and cidade de macuti.

2. Mozambique Coastal Cities Vulnerable to Extreme Weather Events

2.1. Effects of Extreme Weather Events on Coastal Urban Heritage in Mozambique

Mozambique is considered one of the African countries most exposed to the effects of extreme weather events—including coastal erosion, flooding, and rising sea levels, due to its geographic location and geomorphological characteristics [4,12,13]. African coastal cities, in particular, are especially susceptible and vulnerable to these phenomena [14,15,16]. Furthermore, the impacts on the coastal urban areas are already acknowledged and significant; for instance, populations living in cities south of Maputo have been forced to relocate to areas less exposed to coastal erosion [14].

The “Programa de Acção Nacional para a Adaptação às Mudanças Climáticas (NAPA)” (National Action Programme for Adaptation to Climate Change) [12] highlights that Mozambique’s vulnerability to climate impacts is further exacerbated by extreme poverty, population growth and inefficient urban planning, as well as by inadequate policies regulating coastal erosion in the context of anthropogenic pressure [12]. Despite their vulnerability, coastal towns are considered key drivers of the country’s economic development. Approximately 60% of the Mozambican population resides along coastal areas [14] seeking refuge near water bodies due to the abundance of subsistence resources available there [14].

The study “Mozambique: Anticipatory Action and Early Response Framework-Cyclones” reports that cyclonic events strike the Mozambican coast on average every two years. Furthermore, according to data from the “Plano Diretor para a Redução do Risco de Desastres (PDRRD)” [8], between 1980 and 2017, the country experienced 17 extreme weather events—including tropical cyclones and tropical storms—as well as 27 major flood events [8], as described on page 10 of the document. These events have resulted in both partial and total destruction of urban infrastructure.

Climate change has contributed to an increased frequency and intensity of such phenomena [17], which can result in the destruction of elements and places, as well as compromising the preservation of the formal characteristics of urban heritage. As a result, interventions aimed at the management and planning of coastal areas are becoming increasingly imperative in order to increase resilience and support the adaptation of coastal cities [16].

Another example of this phenomenon is Xefina Island, located approximately 7 km north of Maputo, Mozambique’s capital, where the impact of the continuous advance of the sea has led to a significant reduction in the coastal area [18]. Currently, the island hosts the degraded remains of historical military structures, whose deterioration has been accelerated by coastal erosion and the lack of systematic conservation and protective interventions.

2.2. The Impacts of Extreme Weather Events on Ilha de Moçambique

Ilha of Moçambique is currently facing a growing threat from the intensification of extreme weather events driven by climate change. According to the study [19] between 1926 and 2019 the island experienced several cyclonic events, including Cyclone Georgette (1968); Cyclone Nadia (1994); Cyclone Jokwer (2008); Cyclone Idai (2019); Cyclone Kenneth (2019) [20]; Cyclone Guambe (2021); Cyclone Gombe (2022); Cyclone Chiado (2024). More recently, in March 2025, Cyclone June struck the island, causing additional damage to infrastructure.

The increasing frequency and intensity of these events exacerbate the vulnerability of the island’s tangible heritage, accelerating its physical degradation. According to recent reports by UNESCO [21], some of the restoration interventions carried out in response to damage have compromised the authenticity of the cultural heritage. Contributing factors include the absence of adequate water drainage systems and the worsening state of historic buildings, particularly in light of repeated cyclonic activity.

2.3. Ilha de Moçambique as a Paradigmatic Case Study

Ilha de Moçambique is located in Mossuril Bay, in Nampula province, off the northern coast of Mozambique, as can observed in Figure 1. The island measures approximately 3 km [22] in length and between 200 and 500 m in width, and is connected to the mainland by a bridge. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991 [23], according to an estimate carried out in 2007, the island has approximately 17,356 inhabitants [9].

Figure 1.

Case study location in Mozambique and the position of Ilha de Moçambique along the coastline. Authors’ edition, 2025.

The island was historically considered the ancient capital of the country due to its strategic location along India’s maritime trade routes [22,24,25]. Within the spatial context of Ilha de Moçambique, two distinct urban realities coexist, each characterized by its own morphological characteristics: cidade de pedra e cal and cidade de macuti. One of these, the cidade de macuti, is administratively divided into seven neighborhoods—Esteu, Litine, Macaripe, Quirahi, Unidade, Areal, and Marangonh—where a significant portion of the local population currently resides.

The island’s topography is predominantly flat, with the cidade de pedra e cal positioned on slightly elevated ground, approximately 9 m above sea level [22]. The neighborhoods of Esteu, Litine, and Macaripe occupy the lowest area of the island. These neighborhoods currently occupy the old quarry, which provided the stone used to build cidade de pedra e cal [22].

2.4. Urban Characterization of Ilha de Moçambique: Cidade de Pedra e Cal, Cidade de Macuti

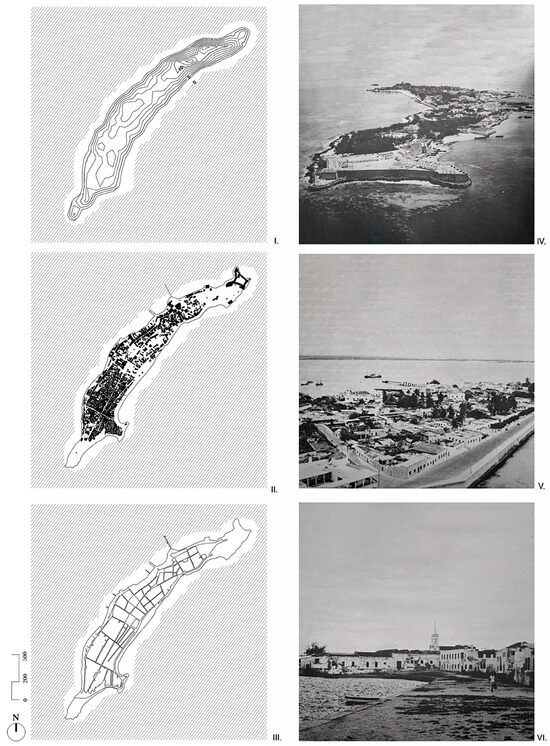

The development of the urban and built fabric on Ilha de Moçambique began between the 16th and 17th centuries [22]. After being considered the country’s capital, the island witnessed the construction of numerous military and religious buildings, as well as facilities supporting maritime navigation to India [22]. Over time, the island’s urban settlement has developed into two distinct urban areas: cidade de pedra e cal and the cidade de macuti. Indeed, the urban form of cidade de pedra e cal reflects the colonial era, characterized by a more regular and planned urban layout, while cidade de macuti presents an organic, dense and informal public space with structures primarily constructed from fragile and perishable materials.

One of the cidade de macuti’s most distinctive architectural features is the roofing of the houses, which is traditionally made from macuti (coconut palm leaves) [6,26,27]. This element is the most emblematic and identifiable architectural feature of the place, defining its identity and serving as a cultural symbol deeply connected to the local building tradition. Administratively, cidade de macuti comprises seven neighborhoods—Esteu, Litine, Macaripe, Quirahi, Unidade, Areal and Marangonha—where a significant portion of local population currently resides. The urban layout and built fabric of the cidade de macuti stand out for its informal and dense organization of buildings constructed from more fragile materials, as can be observed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Delayering of Ilha de Moçambique’s urban form and historical photographs. (I) Topography; (II) Urban built layout; (III) Urban layout. Authors’ edition, 2025. Photographs (IV–VI) from Carlos Alberto e João Marques Caetano, 1966 in [24].

On the contrary, the urban blocks present in cidade de pedra e cal are systematically oriented transversely to the coastline and exhibit a more permanent architectural character, owing to the use of more durable construction materials—specifically, stone masonry and lime mortar. Nevertheless, due to a prolonged lack of maintenance, a number of these structures have been reduced to ruins [22].

As reported in the “Plano de Gestão e Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique 2010–2014” [28] (Mozambique Island Management Plan—2010-14), the management and protection of the island’s heritage are coordinated through the collaboration of various public and private institutions, including the “Conselho Municipal da Ilha de Moçambique (CMCIM)” (Mozambique Island Municipal Council); the “Governo Distrital da Ilha de Moçambique (GDIM)” (Mozambique Island District Government); and the “Gabinete de Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique (GACIM)” (Mozambique Island Conservation Office) [28].

The Ilha of Moçambique has various buildings classified as unique monuments; between them: the fortress of S. Sebastião; the Chapel of Nossa Senhora do Baluarte; the Convent of S. Domingos; the Palace of S. Paulo; the Church of Misericórdia; the Municipal Market; the Hospital; the Church of Saúde; the Main Mosque; the Municipal Slaughterhouse; the Chapel of S. Francisco Xavier; the Church and the Fort of St. António; and the Fort of S. Lourenço, highlighted in Figure 3. This classification complies with the criteria defined in the “Regulamento sobre a Classificação e Gestão de Bens Culturais Imóveis e as Classes do Património Edificado” (Regulation on the Management of Immovable Cultural Assets and Classes of Built Heritage) permitted by “Política de Monumentos” (Monuments Policy).

Figure 3.

The urban layout limit + singular buildings location + the predicted sea level rise—plan and sections. Based on Coastal Risk Screening Tool from Climate Center, Land below 5 m, Authors’ edition, 2025.

According to the “Regulamento sobre a Gestão de Bens Culturais Imóveis”, Regulation of the Built Heritage of the Island of Mozambique [29], heritage elements must be subject to differentiated levels of intervention and protection and the interventions must respect the safety, integrity, legibility, reversibility, cultural and environmental criteria of the pre-existing building [29]. The dispositions in Chapter III, Article 12 define five heritage classes—A+, A, B, C and D—each corresponding to a different level of value and intervention. Class A and A+ identify buildings of outstanding universal and high value, for which only conservation and restoration are permitted. Class B defines buildings with medium value and the level of intervention corresponds to rehabilitation. Classes C and D correspond to buildings with limited value, allowing for reconstruction [29,30]. This set of classes allows interventions in buildings and public spaces to be more regulated and controlled by specific heritage maintenance and restoration techniques.

2.5. The Process of Heritage Recognition in Ilha de Moçambique

The recognition of the island as a heritage site was established through a legislative framework articulated between different entities, notably the “Governo de Moçambique” (Government of Mozambique) and the” Serviço Nacional de Património” (National Heritage Service).

During the second half of the 19th century, with the new commercial routes centered in the city of Maputo (formerly Lourenço Marques), the Ilha de Mozambique experienced an economic decline, leading to the deterioration of its urban fabric and buildings [23]. Indeed, its significance diminished after the city of Lourenço Marques was designated as the new capital of Mozambique in 1898, coupled with the subsequent transfer of the provincial capital to the city of Nampula [31].

In 1955, during the period of Portuguese colonization, the Portuguese government classified the cidade de pedra e cal as a “Imóvel de Interesse Público” (Property of Public Interest) [32]. This official classification enabled the definition of specific measures and the delineation of the architectural and urban interventions to be implemented in the city. In 1966, following the establishment of the “Departamento da Educação e Cultura (DEC)” (Department of Education and Culture), which would later become the “Ministério da Educação e Cultura (MEC)” (Ministry of Education and Culture), there was a growing recognition of the value of heritage, as well as an increasing awareness of the need to safeguard both tangible and intangible cultural assets [32].

However, during the period of the colonial war, between 1977 and 1992, the island experienced an exponential population increase in its resident population, as many mainland inhabitants sought refuge on the Island in search of improved living conditions. Nonetheless, the incoming population from the mainland possessed different cultural values and perceptions of heritage compared to the local residents. This cultural divergence negatively affected the approach to heritage preservation on the Island through the informal occupation of the historical urban area [32].

In 1982, following Mozambique’s adherence to the UNESCO Convention for the Protection of the Heritage of 1972, the Ilha de Mozambique was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1991, according to criteria IV and VI, which recognize the exceptional value of the place [23,32]. The recognition of the island’s historical significance stimulated new initiatives, both local and international, aimed at preserving its built heritage. In particular, the project and exhibition “A Ilha de Moçambique em Perigo de Desaparecimento. Uma Perspectiva Histórica e um Olhar para o Futuro” (The Island of Mozambique in Danger of Disappearing. A Historical Perspective and a Look to the Future), sought to raise awareness of the urgent need to rehabilitate the island’s urban fabric, severely affected by physical decay, as well as the threat posed by rising sea levels and coastal erosion [25]. Furthermore, the “Relatório—Ilha de Moçambique 1982–1985” (Report—Ilha de Moçambique 1982–1985) developed through collaboration between the “Secretaria de Estado da Cultura” (Secretary of State for Culture) and the Aarhus School of Architecture in Denmark, played a pivotal role in supporting the island’s nomination and inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

In 2006, the “Gabinete de Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique (GACIM)” (Mozambique Island Conservation Office) was established to monitor the state of preservation and interventions implemented concerning the island’s heritage [23,27]. In the same period, the “Estatuto Específico da Ilha de Moçambique” (Specific Statute of the Island of Mozambique) was approved, with the objective of improving the application of national legal instruments ensuring alignment with UNESCO standards in the scope of heritage preservation.

3. Method

3.1. Data Acquisition

This research focuses on reviewing the different planning instruments and strategies implemented in Mozambique for the preservation and adaptation to climate change in cultural heritage, with particular emphasis on Ilha de Moçambique.

The methodology adopts a systematic policy review approach, developed to provide a rigorous framework for critical assessment across multiple governance scales. The methodological process consists of three main stages: (i) collection, (ii) selection, and (iii) critical review and interpretation of plans, planning instruments, and policy documents applied at different scales, ranging from national frameworks to site-specific local initiatives.

In the first stage, relevant policy documents, plans, and strategies were systematically gathered from national, regional and local sources, including governmental agencies, official repositories, and international frameworks. The selection was guided by the relevance of each instrument to cultural heritage preservation, climate change adaptation and applicability to coastal urban contexts. The selected documents were organized, according to legislative hierarchy (international, national and local), approval date, temporal scope (long-term, medium-term and short-term strategies), authors, responsible entities, description. These criteria enable us to develop a formula for ordering and identifying the available instruments.

Therefore, to ensure a comparison criteria, documents were coded and assessed against a framework of criteria, including: type of instrument; plan validity; territorial scope; indication of adaptation measures in heritage; temporal scope; climate adaptation measures, goals and actions and heritage measures, goals and actions. This classification enabled a systematic comparison and the identification of overlaps, gaps or complementarities between the instruments.

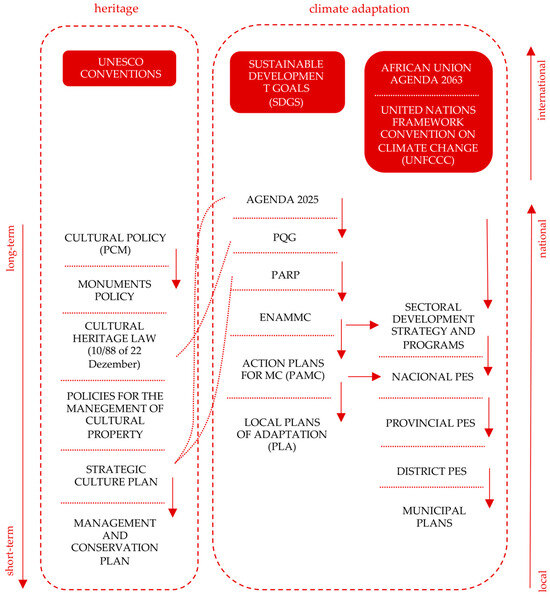

Figure 4 presents the selected documents, plans, organized vertically according to their legislative hierarchy. They are further classified across three spatial levels—international, national and local—and arranged along a longevity axis, spanning from long-term strategies to short-term actions.

Figure 4.

Diagram illustrating the hierarchy of plans and the interrelation of planning instruments, based on the Policy Framework in the National System for Monitoring and Evaluation of Climate Change (SNMAMC) [33]. Authors’ edition, 2025.

3.2. Data Cataloging

In order to catalog the plans and instruments presented in Table 1, it was necessary to establish a set of observation criteria, namely: the “Type of instrument” which indicates the nature of the instrument; “Approval date” corresponding to the date of official approval of the instrument; “Temporal scope” referring to the instrument’s temporal scope; ‘Authors’ listing the individuals, groups, or institutions directly involved in the elaboration and development of the plan; “Responsible entities” refers to the institutions or entities responsible for implementing or monitoring compliance with the instrument; “Description” summarizing the instrument’s content, including its purpose, main objectives, and key actions. Additionally, the plans and instruments are organized according to a legislative hierarchy covering the period from 2010 to 2025.

Table 1.

Overview of the principal instruments, Authors’ Edition, 2025.

Table 2 is organized with the aim of systematizing and comparing various climate change adaptation plans developed between 2010 and 2025. Its structure is designed to collect essential information on each reviewed instrument, enabling a critical reading of both the content and the institutional and territorial context in which these documents were produced. Overall, the table’s organization is based on Type of Instrument; Plan validity; Territorial scope; Indication of adaptation measures in heritage; Temporal Scope; Climate adaptation and heritage measures, goals and actions classification criteria. These criteria facilitate the comparison of different instruments and help to identify correlations as well as existing gaps.

Table 2.

Literature Review of Adaptations Plans (2010–2025). Authors’ Edition, 2025.

The characterization of the plans was outlined according to a guide and a set of systematic criteria, namely: “Type of instrument,” “Plan validity”, “Territorial scope”, “Indication of adaptation measures in heritage—Explicit, Implicit, Undefined”, “Temporal scope”, “Climate adaptation measures, goals and actions” and “Heritage adaptation measures, goals and actions”.

“Type of instrument” identifies the formal nature of each collected and analyzed document—for instance, whether it is an adaptation plan, public policy, or a national or local strategy. This classification is essential for understanding the institutional role of each instrument and enables the identification of different strategic approaches.

“Plan validity” indicates the year in which the plan was developed. This temporal reference situates the instrument within a specific timeframe and contributes in understanding key moments in the development of adaptation policy.

“Territorial scope” refers to the geographical scale at which the adaptation plan is applied. This criterion is essential for understanding the scale of intervention implemented across different governance levels.

“Indication of adaptation measures in heritage—Explicit, Implicit, Undefined” evaluates the extent to which the adaptation plan considers and integrates heritage. Adaptation measures related to heritage can be classified as explicit, implicit, or undefined, depending on how heritage is addressed within the plan. When measures are explicit, the plan clearly outlines detailed actions aimed at protecting, preserving, or adapting heritage in response to climate change.

In the case of implicit measures, the adaptation plan does not directly mention heritage, but indicates actions or guidelines that may indirectly benefit or protect it in the face of extreme climate events. When the indication of adaptation measures for heritage is undefined, the plan makes no explicit reference to heritage or its protection within the context of climate change adaptation. In such cases, the plan may address adaptation measures related to infrastructure or communities in general, without recognizing or incorporating specific actions for heritage.

“Temporal scope” refers to the plan’s time horizon, indicating the period envisioned for implementing the proposed measures, which can be organized into short-, medium- or long-term.

“Climate adaptation measures, goals and actions” and “Heritage adaptation measures, goals and actions” provide a summary of the main actions and strategies. This category includes only those measures, actions, and strategic objectives that explicitly address the relationship between the preservation or protection of heritage and extreme climate events, as outlined in the plans observed.

4. Results

4.1. Adaptation Measures Implemented at the National Scale

A review of national planning instruments reveals a lack of articulation between policy measures aimed at protecting and preserving heritage and strategic actions in the face of extreme climatic events. Indeed, the “Estratégia Nacional de Desenvolvimento (ENDE) (2025–2044)” (National Development Strategy (ENDE) (2025–2044) [35], in the cultural sphere, underscores the need to preserve and enhance tangible cultural heritage in order to guarantee its continuity for future generations. With regard to climate change, the strategy identifies investment in infrastructure resilient to extreme weather events as a key strategic objective. However, the protection of cultural heritage in the context of extreme weather events is not explicitly discussed. In other words, while the strategy prioritizes the adoption of climate change adaptation measures, it remains unclear how these actions and objectives are to be operationalized with regard to tangible heritage.

Similarly, the “Politica Cultural” (Cultural Policy), integrated into the Government of Mozambique’s Five-Year Program, highlights as a priority the support of initiatives aimed at the preservation and enhancement of heritage assets—particularly with a special focus on the Island of Mozambique (Law 12/97 10 of June).

Moreover, the “Programa Quinquenal do Governo de Moçambique (PQG)” (Quinquennial Government Plan) [36] reaffirms the government’s commitment to promoting research, preservation and enhancement of Mozambican’s cultural heritage. Similarly, in the domain of risk management, the plan emphasizes the need to reduce the vulnerability of both communities and infrastructures to climate-related risks arising from natural and anthropogenic phenomena.

Other national-level instruments aimed at climate change adaptation—such as the “Programa Nacional de Ação para Adaptação às Mudanças Climáticas (NAPA)” [12], the “Plano de Ação para Redução da Pobreza (PARP)” [37], and the “Plano Diretcor de Redução de Riscos de Desastres (PDRRD)” [8] mainly include implicit measures. While these documents do not explicitly address cultural material heritage, the proposed actions may indirectly contribute to its protection and preservation. Such contributions are reflected, for instance, in resilient-oriented strategies including the mapping of vulnerable infrastructure in relation to specific climate phenomena, the construction of protective barriers in densely populated areas, and the relocation of communities to safer areas.

4.2. Adaptive Strategies for the Protection of Heritage on the Ilha de Moçambique

In 2006, the Government of Mozambique, in accordance with Decreto No. 28/2006 of 13 July, established the Mozambique Island Conservation Office (GACIM), with the mandate to coordinate tourism development on the island and to guide interventions aimed at the protection and preservation of its cultural heritage [31].

In 2011, as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Cities program, the “Historic Urban Landscape (HUL)” approach was introduced on the island. This approach emerged in response to the island’s accelerated heritage degradation and aims to foster more effective management and preservation of heritage areas articulated with sustainable local development [23,38]. Key initiatives under this framework have included the implementation of heritage management regulations; the integration of basic infrastructure in the cidade de macuti, and the revitalization of the cidade de pedra e cal [38].

In 2017, the project “Resilient Houses for the residents of Mozambique Island” was developed under the framework of the USAID Coastal Cities Adaptation Program (CCAP), in collaboration with the Island’s Municipal Council and UNHABITAT. According to the União das Cidades Capitais de Língua Portuguesa (UCCLA—Union of Portuguese-Speaking Capital Cities) [39], the initiative aimed to train local artisans in construction techniques adapted to withstand the impacts of extreme weather events. As part of the project, three prototypes of more climate-resilient houses were built in the Massicate neighborhood [39].

According to the “Report of the State of Conservation of Mozambique Island (World Heritage Site) 2022” produced by the Mozambique Island Conservation (GACIM), several projects are currently being implemented [40]. Among them, the project entitled “Heritage and environmental education: Reinforcement of citizenship and social participation on the Island of Mozambique and the project” [40] and the project “Community Participation in Assessing the State of Heritage Conservation and Resilience Mechanisms in Response to Risks and Disasters Caused by Cyclonic Events (2024)” [41] aims to prepare and empower the local population to respond to climate change. These initiatives promote a set of tools and strategies designed to mitigate the impacts of extreme weather events on the integrity and authenticity of cultural heritage.

Indeed, a range of collective and individual actions have been undertaken to support the adaptation and preservation of the island’s urban heritage. These interventions are documented in the annual reports on the state of conservation of the island’s heritage, prepared by GACIM, which address both anthropogenic and natural threats. According to the most recent Report on the State of Conservation of the Island of Mozambique (2022), the damage caused by Cyclone Gombe—which affected numerous buildings on the island—was followed by a series of rehabilitation interventions [40]. However, despite these building-scale efforts, there remains a significant lack of coordinated interventions focused on adapting and preserving public spaces in the face of increasingly frequent cyclonic events.

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy and Planning Frameworks in Ilha de Moçambique

The case study of Ilha de Moçambique provides a relevant context for reviewing and analyzing planning instruments and strategies in the articulation of heritage preservation with adaptation to the impacts of extreme weather events. As demonstrated in this study, and according to documentation available on the UNESCO platform [21], storms were identified as a significant risk factor between 1994 and 2006. However, in reports published in the subsequent period, this concern was no longer explicitly emphasized. It was only between 2021 and 2023 that the threat posed by extreme weather phenomena re-emerged as a prominent issue in official records [21].

Furthermore, a critical analysis of the principal planning instruments reveals that most documents lack a cohesive framework that explicitly integrates climate change adaptation with heritage preservation. In many instances, the proposed measures tend to focus exclusively on one of these domains—either climate adaptation or heritage conservation—without establishing an effective link between these two dimensions of planning.

An exception is the “Plano Estratégico de Desenvolvimento Distrital da Ilha de Moçambique (PEDD)” [9] which identifies the area’s most vulnerable to pluvial flooding in the cidade de macuti—such as the Litine neighborhood—and outlines strategic measures to address the issue, including the reconstruction of the city’s drainage system and the promotion of early warning mechanisms for flooding. Another notable example is the “Estratégia Nacional de Adaptação e Mitigação das Mudanças Climáticas (ENAMMC)” [7], which, albeit in general terms, includes a provision for adapting heritage to risks associated with climate change.

For instance, the “Programa Quinquenal de Desenvolvimento Nacional (PQG)” [36] makes reference to the protection of cultural heritage; however, it lacks an explicit and operational framework for addressing the impacts of extreme climatic events. This omission undermines the coherence and potential impact of the proposed actions, particularly in a territorial context characterized by acute vulnerability.

On the other hand, the “Lei de Proteção do Património Edificado e do Regulamento dos Bens Classificados na Ilha de Moçambique” (Regulation of the Law for the Protection of Built Heritage and the Regulation of Classified Property on the Island of Mozambique) contains important information regarding the management of natural risks. Article 53 stipulates that preventive measures must be implemented to mitigate the negative effects of natural disasters on heritage sites, with the aim of safeguarding their physical integrity. Furthermore, Article 54, Subsection III, reinforces the need for special attention to ensure the protection and integrity of heritage sites, while at the same time guaranteeing the preservation of their cultural significance. Although these legislative advances are noteworthy, in practice, many of the measures proposed in strategic documents lack sufficient clarity regarding their effective contribution to adapting heritage to climate change. We therefore consider that what is needed are detailed, site-specific plans and projects that address the unique needs of each heritage site while aligning with the general guidelines set by national-level policies.

In the case of the “Estratégia Nacional de Adaptação e Mitigação das Mudanças Climáticas (ENAMMC)” [7], for example, the strategic objective to “promote tree planting mechanisms develop resilience mechanisms for urban areas and other settlements adapting the development of tourist areas and coastal zones” [7] raises several questions regarding its practical application. We are therefore led to ask: where are the trees intended to be planted? Which species are envisaged? Does the strategy refer specifically to mangrove reforestation as a means to contain coastal erosion? Such omissions risk compromising the proposed intervention.

The “Plano Estratégico da Cultura (PEC)” (Strategic Plan for Culture), developed following the establishment of the new Ministry of Culture in 2010, aims to position culture as a driver of development by outlining various actions to enhance both tangible and intangible heritage at the national level. However, this instrument neither explicitly addresses the climate vulnerability of heritage assets nor proposes specific adaptation measures.

Similarly, the “Regulamento sobre a Gestão de Bens Culturais Imóveis ou a Lei da Protecção Cultural (Lei 10/88 de 22 de Dezembro)” (Regulations on the Management of Immovable Cultural Property and the Cultural Protection Law (Law No. 10/88 of 22 December) lacks provisions concerning the safeguarding of heritage against extreme climatic events. Although there are instruments such as the “Plano Estratégico Nacional para Gestão do Património Cultural” (National Strategic Plan for Cultural Heritage Management) and initiatives like the “Safe Schools” project—developed by UN-Habitat and implemented by “Ministério da Educação e Desenvolvimento Humano de Moçambique” (Mozambique’s Ministry of Education and Human Development), with the aim of constructing educational infrastructure resilient to the impacts of climate change—the absence of intersectoral coordination and integrated policy guidelines may undermine the coherence and long-term impact of these initiatives. Consequently, we could affirm that responses tend to be fragmented and peripheral rather than more targeted and inclusive.

Furthermore, population growth may exacerbate existing challenges related to sanitation, public health and housing problems on the Ilha de Moçambique. According to projections by the National Statistics Institute (INE), the island is expected to experience significant demographic growth in the coming decades, driven by increased birth rates and improvements in health conditions that have contributed to higher life expectancy. The National Statistics Institute (INE) estimates that the local population could nearly double, rising from approximately 867,000 inhabitants to 170,000 by 2040 [42,43]. Should this trend continue, it may lead to socio-economic decline, further aggravating the island’s environmental vulnerability.

5.2. International Lessons and Levels of Integration

Internationally, the city of Venice, similar to many other UNESCO World Heritage cities, faces challenges posed by extreme climatic events. In response to recurrent flooding and the sea level rise, the “Venezia e La sua Laguna Patrimonio Mondiale Unesco—Piano Di Gestione (2012–2018) (Venice and its Lagoon UNESCO World Heritage Site—Management Plan), ref. [44] was developed with the objective of protecting and enhancing the site by promoting the coordination and articulation between climate change management and cultural heritage. Among its strategic objectives, it emphasizes the restoration and maintenance of heritage assets, as well as the adaptation of sea level rise impacts on the urban fabric [44]. Additionally, based on these objectives, action plans were outlined focusing on the protection and preservation of heritage. This initiative reveals a first attempt to answer to the increasingly recognized necessity of integrating cultural heritage preservation considerations with climate change adaptation strategies

Based on the international example presented above, it is possible to identify three levels of integration between climate adaptation and heritage preservation: (i) lack of integration, where policies address only one dimension focused on heritage or climate adaptation; (ii) partial integration, where policies recognized the link between heritage and climate adaptation, with strategic guidelines and orientations present in plans and instruments; (iii) systemic integration, where adaptation and heritage are explicitly coordinated through specific planning and projects at different scales, with protocols and implementation monitoring.

In conclusion, the lack of integration between climate change adaptation and protection plans and those aimed at preserving tangible cultural heritage, combined with pressing challenges related to overpopulation, inadequate sanitation services, and socio-economic vulnerabilities, undermines the resilience of Ilha de Moçambique. We therefore argue that without a coherent, cross-sectoral approach that addresses these interlinked issues globally, both cultural assets and community wellbeing remain exposed to significant risks amid growing environmental and demographic pressures.

6. Conclusions

The intensification of climate change represents a significant challenge in the domain of heritage preservation, as it subjects cultural and historical assets to increasingly severe risks. In this context, it is essential to establish a coherent integration and coordination between climate adaptation measures and heritage preservation strategies, thereby enabling more pragmatic and directive responses.

To achieve this, regulatory instruments for territorial management and planning should be developed from a more integrated perspective of the inhabited physical space, with the local population as the central point of reference. Consequently, it is necessary to revisit these regulatory instruments in two respects: first, by updating and revising them through a transversal alignment; and second, by embracing inclusion as a fundamental principle.

This entails shifting the perception of such instruments from being solely technical tools to recognizing and reinforcing their sociological, socio-cultural and economic dimensions as they relate to the local inhabitants.

According to the previously presented case of Venice, we could argue that there is a need to develop technical instruments, such as the mapping of the most vulnerable areas, the systematic assessment of risks to identify key vulnerabilities, and the consequent establishment of continuous risk monitoring protocols. These instruments should be supported by specific funding and directives that integrate heritage protection into policies for reducing the risk of extreme weather events. At the same time, we therefore believe that institutional changes are essential, including greater coordination between the Ministries of Culture, Environment, and Urban Planning, along with the creation of intersectoral committees with active and inclusive community participation. Incorporating community perceptions and traditional practices into urban planning instruments can contribute to enhancing the capacity of cities to address social and environmental challenges [45]. Therefore, future research could explore broader international comparisons, providing insights for other coastal heritage cities facing similar weather-related challenges.

In the case of Ilha de Moçambique, a possible future development scenario hinges on effective coordination among public institutions, local communities and international partners. Such cooperation must lead to the formulation and implementation of integrated strategies that facilitate effective responses to the impacts of climate change, while safeguarding the preservation of urban heritage.

In this context, the preservation of the heritage of the cidade de pedra e cal and the cidade de macuti is intrinsically related to the improvement of inhabitants’ living conditions through infrastructure development and urban requalification programs. However, despite the investment in infrastructures, neighborhoods within the cidade de macuti may continue to experience challenges related to precarious housing and inadequate sanitation. If current development experience challenges alteration within the macuti neighborhoods—particularly the use of inappropriate construction materials—could compromise the authenticity of the heritage according to complementary conservation criteria. Moreover, population growth combined with the lack of planning can intensify the problems of sanitation, public health and housing.

Therefore, the characterization of planning instruments according to a common framework that allows for their comparison is not a methodological innovation. However, the themes and criteria chosen in this research allow us to summarize the content of each one in relation to the topics addressed and answer the research questions posed.

In conclusion, the review of the most relevant instruments reveals a systemic weakness in the integration of climate and heritage policy in Mozambique. The lack of a strategic framework, clearly articulated through operational instruments that concretely link climate change adaptation with heritage preservation, constitutes a significant barrier to the resilience of vulnerable territories, such as Ilha de Moçambique. Developing effective solutions will necessitate an intersectoral and multi-scalar approach that recognizes the value of heritage not only as a tangible legacy but as a critical component of urban climate adaptation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V.M., L.L. and F.D.C.; methodology, C.V.M. and F.D.C.; software, C.V.M.; validation, S.B.P., F.D.C., C.V.M. and L.L.; formal analysis, C.V.M., F.D.C., S.B.P. and L.L.; investigation, C.V.M., F.D.C., L.L. and S.B.P.; resources, C.V.M.; data curation, C.V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V.M., F.D.C., S.B.P. and L.L.; writing—review and editing, C.V.M., F.D.C., S.B.P. and L.L.; supervision, F.D.C., S.B.P. and L.L.; funding acquisition, C.V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financed by national funds through FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the strategic project with the references UID/04008: Centro de Investigação em Arquitetura, Urbanismo e Design. And it is also financed by national funds through FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project with the reference 2023.05118.BD.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANE | Administração Nacional de Estradas |

| AWHF | Fundo Mundial para o Património Africano |

| CONDES | Conselho Nacional para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável |

| CTGC | Conselho Técnico de gestão de Calamidades |

| CLGRC | Conselhos Locais de Gestão do Risco de Calamidades |

| CENOE | Centros Nacionais Operativos de Emergência |

| CMCIM | Conselho Municipal da Cidade da Ilha de Moçambique |

| CCGC | Conselho Coordenador de gestão das Calamidades |

| MICOA | Ministério para a Coordenação da Acção Ambiental |

| MISAU | Ministério de Saúde |

| INGC | Instituto Nacional de Gestão de Calamidades |

| MS | Ministros Sectoriais |

| MPD | Ministério do Plano de Desenvolvimento |

| MPD | Ministério do Plano e Desenvolvimento |

| MOPH | Ministério das Obras Públicas e Habitação |

| MINAG | Ministério da Agricultura |

| MC | Ministério da Cultura |

| OREP | Órgãos de Representação do Estado Provincial |

| OGDP | Órgãos de Governação Descentralizada Provincial |

| DPT | Direcção Provincial de Transportes e Comunicações de Nampula |

| BM | Banco Mundial |

| MITADER | Ministério da Terra, Ambiente e Desenvolvimento Rural |

| MTA | Ministério da Terra e Ambiente |

| INE | Instituto Nacional de Estatística |

| IPAD | Instituto Português de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento |

| INAM | Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia |

| INGD | Instituto Nacional de Gestão e Redução do Risco de Desastres |

| MEF | Ministério da Economia e Finanças |

| DNMC | Direção Nacional de Mudanças Climáticas |

| MADER | Ministério da Agricultura de Desenvolvimento Rural |

| OSC | Organização da Sociedade Civil |

| MIREME | Ministério da Energia e Recursos Minerais |

| SNMAMC | Sistema Nacional de Monitoria e Avaliação das Mudanças Climáticas |

| UNCDF | Fundo das Nações Unidas para o Desenvolvimento de Capital |

| UNESCO | Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura |

| PNUD | Programa das Nações Unidas para o Desenvolvimento |

| GM | Governo de Moçambique |

| GTT | Grupo Técnico de Trabalho |

| GEF | Fundo Global para o Meio Ambiente |

| GACIM | Gabinete de Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique |

| GDIM | Governo Distrital da Ilha de Moçambique |

| PEDD | Plano Estratégico de Desenvolvimento Distrital |

References

- Sesana, E.; Gagnong, A.S.; Bertolin, C.; Hughes, J. Adapting Cultural Heritage to Climate Change Risks: Perspectives of Cultural Heritage Experts in Europe. Geosciences 2018, 8, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisse, T.; Brempong, K.; Taveneau, A.; Almar, R.; Sy, B.A.; Anguureng, B. Extreme coastal water levels with potential flooding risk at the low-lying saintlouis historic city, Senegal (West Africa). Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 993644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, J.; Irish, J.; Camargo, S. Coastal flooding by tropical cyclones and sea-level rise. Nature 2013, 504, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Clarke, J.; Ranasinghe, R.; Reimann, L.; Khalaf, N.; Duong, T.M.; Ouweneell, B.; Sabour, S.; Iles, C.E.; Trisos, C.H.; et al. African heritage sites threatened as sea-level rise accelerates. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzeion, B.; Levermann, A. Loss of cultural world heritage and currently inhabited places to sea-level rise. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milão, S.; Ribeiro, T.; Correia, M.; Neves, I.C.; Flores, J.; Alvarez, O. Contributions to Architectural and Urban Resilience Through Vulnerability Assessment: The Case of Mozambique Island’s World Heritage. Heritage 2025, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério para a Coordenação da Ação Ambiental (MICOA). Estratégia Nacional de Adaptação e Mitigação de Mudanças Climáticas (ENAMMC) 2013–2025; Governo de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 2012; Available online: https://www.biofund.org.mz/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Estrategia-Nac-Adaptacao-e-Mitigacao-Mudancas-Climaticas-2013-2025.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- República de Moçambique–Conselho de Ministros. Plano Director para a Redução do Risco de Desastres 2017–2030 (PDRRD). Governo de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique; 2017. Available online: https://cdn.climatepolicyradar.org/navigator/MOZ/2017/master-plan-for-disaster-risk-reduction-2017-2030_09301d0b6bcd081a43fbb7f5edcf4857.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Governo do Distrito da Ilha de Moçambique. República de Moçambique. Plano Estratégico de Desenvolvimento Distrital 2010-14 (PEDD); 2009. Available online: https://www.acismoz.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Plano%20Estrategico%20de%20Desenvolvimento%20Distrital%20Ilha%20de%20Mocambique%20%20Ilha%20de%20Mocambique%20-%202010%20-%202014.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Carroll, P.; Aarrevaara, E. The Awareness of and Input into Cultural Heritage Preservation by Urban Planners and Other Municipal Actors in Light of Climate Change. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, R.; Jelo, G. Built Heritage Preservation and Climate Change Adaptation in Historic Cities: Facing Challenges Posed by Nature-Based Solutions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério para a Coordenação da Acção Ambiental (MICOA). Programa de Acção Nacional para a Adaptação às Mudanças Climáticas (NAPA); Direcção Nacional de Gestão Ambiental: Maputo, Moçambique, 2007; Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/16411_planonacionalparaadaptaoasmudanascl.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Massuanganhe, E.A.; Macamo, C.; Westerberg, L.; Bandeira, L.; Mavume, A.; Ribeiro, E. Deltaic coasts under climate-related catastrophic events—Insights from the Save River delta, Mozambique. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2015, 116, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, P.; Augusto, G.; Akande, A.; Costa, A.; Amade, N.; Niquisse, S.; Atumane, A.; Cuna, A.; Kazemi, K.; Mlucasse, R.; et al. Assessing Mozambique’s exposure to coastal climate hazards and erosion. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 23, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrua, A.B.; Bandeira, S.O.; Catarino, S.; Cabral, P.; Romeiras, M.M. Assessment of the vulnerability of coastal mangrove ecosystems in Mozambique. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 189, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machel, S. Analysis of Extreme Weather Events in Coastal Regions in Mozambique. Int. J. Clim. Stud. 2024, 3, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blavier, C.; Huerto-Cardenas, H.; Aste, N.; Pero, C.; Leonforte, F.; Torre, S. Adaptive measures for preserving heritage buildings in the face of climate change: A review. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaúque, A. Estudo da dinâmica da linha de costa na Ilha de Xefina (2004–2016). In Monografia para a Obtenção do Grau de Licenciatura em Oceanografia; Escola Superior de Ciências Marinhas e Costeiras Universidade Eduardo Mondlane: Quelimane, Moçambique, 2017; Available online: http://monografias.uem.mz/bitstream/123456789/1949/1/2017%20-%20Chaúque%2C%20Alfredo.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Rebelo, M. Exposição, Vulnerabilidade e Risco aos Perigos Naturais em Moçambique: O Caso dos Ciclones Tropicais no Município de Angoche. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Gestão de Desastres (INGD). Relatório do Balanço da ECC 2017–2018. Maputo, Moçambique: INGD. 2025. Available online: https://ingd.gov.mz/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Relatorio_do_Balanco_da_ECC_2017-2018.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- UNESCO. Island of Mozambique. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/4380 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Secretaria de Estado da Cultura Moçambique-Arkitektskolen i Aarhus-Danmark. Ilha de Moçambique—Relatório 1982-85; Governo de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Macamo, S.; Raimundo, M.; Moffett, A.; Lane, P. Developing Heritage Preservation on Ilha de Moçambique Using a Historic Urban Landscape Approach. Heritage 2024, 7, 2011–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, A. Ilha de Moçambique: Panorama Estético; Agência Geral do Ultramar: Lisboa, Portugal, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Lobato, A.; Escudeiro, A.; Barros, J.; Forjaz, M.; Knopfly, R.; Viana de Lima, A.; Alves, A. A Ilha de Moçambique em Perigo de Desaparecimento: Uma perspectiva Histórica, Um Olhar para o Futuro; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian: Lisboa, Portugal, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, C. Mozambique Island: Transform a World Heritage Site in a Touristic Destination. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2012, 2, 1134–1137. Available online: https://www.tmstudies.net/index.php/ectms/article/view/310 (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Zunguene, C. Conflitos e tensões na fiscalização do patrimônio cultural edificado pelo IPHAN em Ouro Preto e GACIM na Ilha de Moçambique: Uma análise comparativa. Master’s Thesis, Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Cultura Moçambique. Plano de Gestão e Conservação Ilha de Moçambique Património Cultural Mundial (PGC) 2010-14; Governo de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 2010.

- Decreto nº54/2016, de 28 de novembro de 2016 (aprova o Regulamento sobre a Classificação e Gestão do Património Edificado e Paisagístico da Ilha de Moçambique. Boletim da República nº142. Available online: https://ilhademocambique.co.mz/sites/default/files/2023-05/legislacoes6.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Macamo, S. O sistema de gestão da ilha de Moçambique: Implementação da legislação na área do património edificado. In Oficinas de Muhipiti: Planeamento Estratégico Património Desenvolvimento; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2017; pp. 89–134. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, L.; Dias, J. O Cluster da Ilha de Moçambique e a Recuperação da Fortaleza de S.Sebastião; Instituto Portugues de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento (IPAD): Lisbon, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, L.; Júnior, E. Património Cultural e Memória Social na Ilha de Moçambique. Rev. CPC 2014, 18, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Sustentável (CONDES). República de Moçambique. Sistema Nacional de Monitoria e Avaliação das Mudanças Climáticas (SNMAMC); Governo de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 2014. Available online: https://climatechangemoz.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/SistemaNacionaldeMonitoriaeAvaliacaodasMudancasClimaticas-Mozambique.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Comité de Conselheiros–Ministério da Economia e Finanças. Agenda 2025: Visão e Estratégias da Nação; Comité de Conselheiros–Ministério da Economia e Finanças: Maputo, Moçambique, 2001.

- Governo de Moçambique–Ministério da Economia e Finanças; Ministério da Planificação e Desenvolvimento. Estratégia Nacional de Desenvolvimento (ENDE) 2025–2044; Ministério da Economia e Finanças: Maputo, Moçambique, 2024.

- Governo de Moçambique–Assembleia da República. Programa Quinquenal do Governo (PQG) 2020–2024; Assembleia da República: Maputo, Moçambique, 2020.

- República de Moçambique–Ministério da Economia e Finanças. Plano de Ação para Redução da Pobreza (PARP) 2011–2014; Ministério da Economia e Finanças: Maputo, Moçambique, 2011.

- Jopela, A. Salvar as paisagens urbanas: Ilha de Moçambique. In O Correio da UNESCO Reinventar as Cidades; Mabanckou, A., Majfud, J., Reverdy, T., Eds.; Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura: London, UK, 2019; pp. 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- União das Cidades Capitais de Língua Portuguesa (UCCLA). Casas Resilientes para os Munícipes da Ilha de Moçambique. Available online: https://www.uccla.pt/noticias/casas-resilientes-para-os-municipes-da-ilha-de-mocambique (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- GACIM (Gabinete de Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique). Report of the State of Conservation of Mozambique Island (World Heritage Site) 2022; Ministério da Cultura e Turismo, República de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 2022; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/198379 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 20XX. “International Assistance under the World Heritage Convention”. UNESCO. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/intassistance/3488 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Projecções Anuais da População Total, Urbana e Rural, Moçambique (2017–2050); INE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Estatísticas do Distrito de Ilha de Moçambique (2020–2024); INE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2024.

- Comune di Venezia. Venezia e la Sua Laguna: Patrimonio Mondiale UNESCO–Piano di Gestione 2012–2018: Documento di Sintesi; Comune di Venezia: Venice, Italy, 2012. Available online: https://www.comune.venezia.it/sites/comune.venezia.it/files/page/files/LOW_executive_ita.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Khamis, A.H.; Hollmén, S.; Koskinen, A.; Nimri, L. Stone Town Built Heritage Identity as a Stimulus to Sustainable Urban Growth within Zanzibar City. Environ. Sci. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 9, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).