Does Tourism Gentrification in Urban Areas Affect Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior?

Abstract

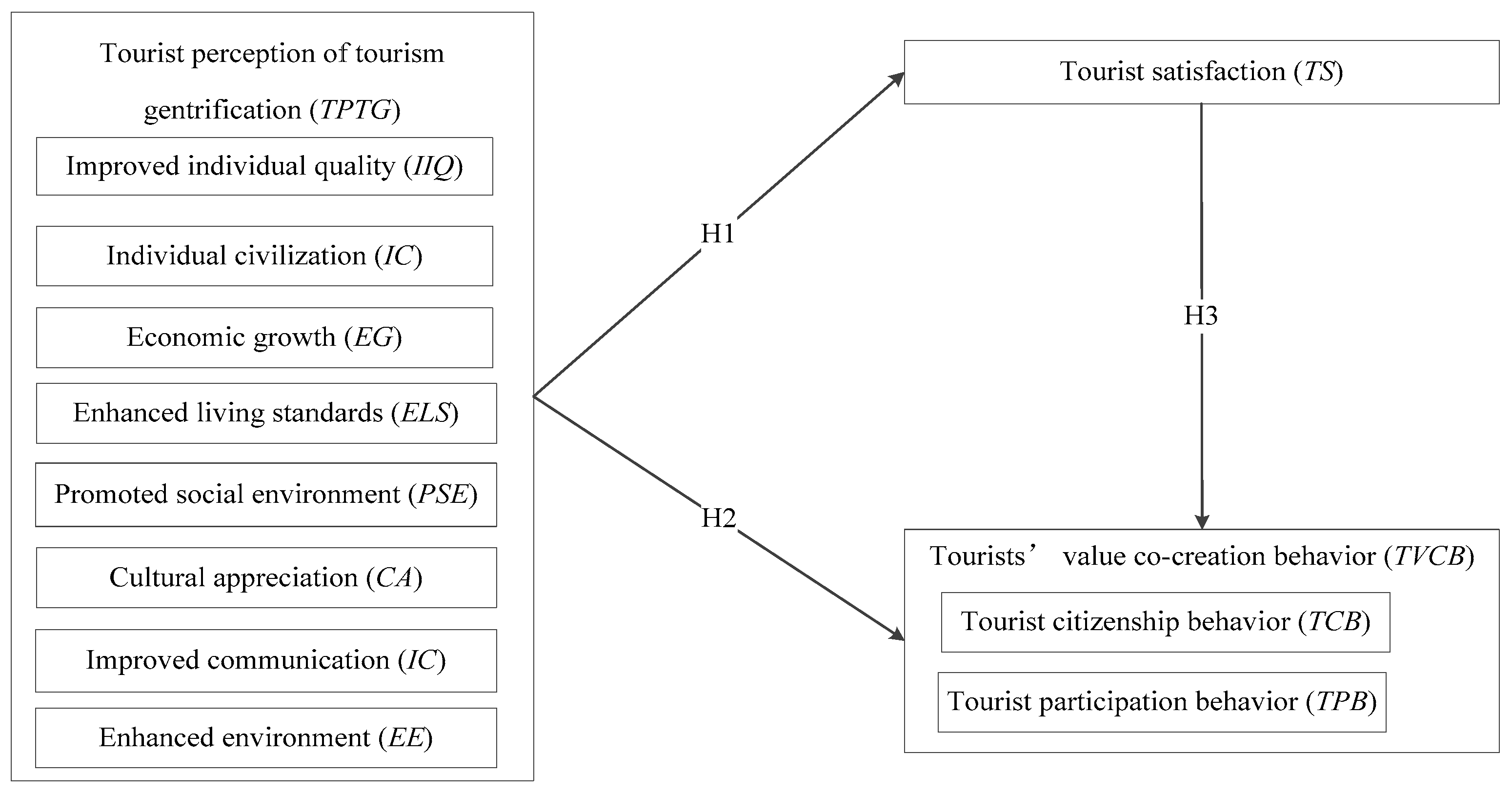

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Gentrification

2.1.1. The Concept of Tourism Gentrification

2.1.2. Research on Tourism Gentrification

2.2. Tourists’ Perception of Tourism Gentrification and Tourist Satisfaction

2.2.1. The Concept of Tourist Satisfaction

2.2.2. Research on Tourists’ Perception of Tourism Gentrification and Tourist Satisfaction

2.3. Tourists’ Perception of Tourism Gentrification and Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior

2.3.1. The Concept of Value Co-Creation Behavior

2.3.2. Tourists’ Perception of Tourism Gentrification and Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior

2.4. Tourist Satisfaction and Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior

3. Materials and Methods

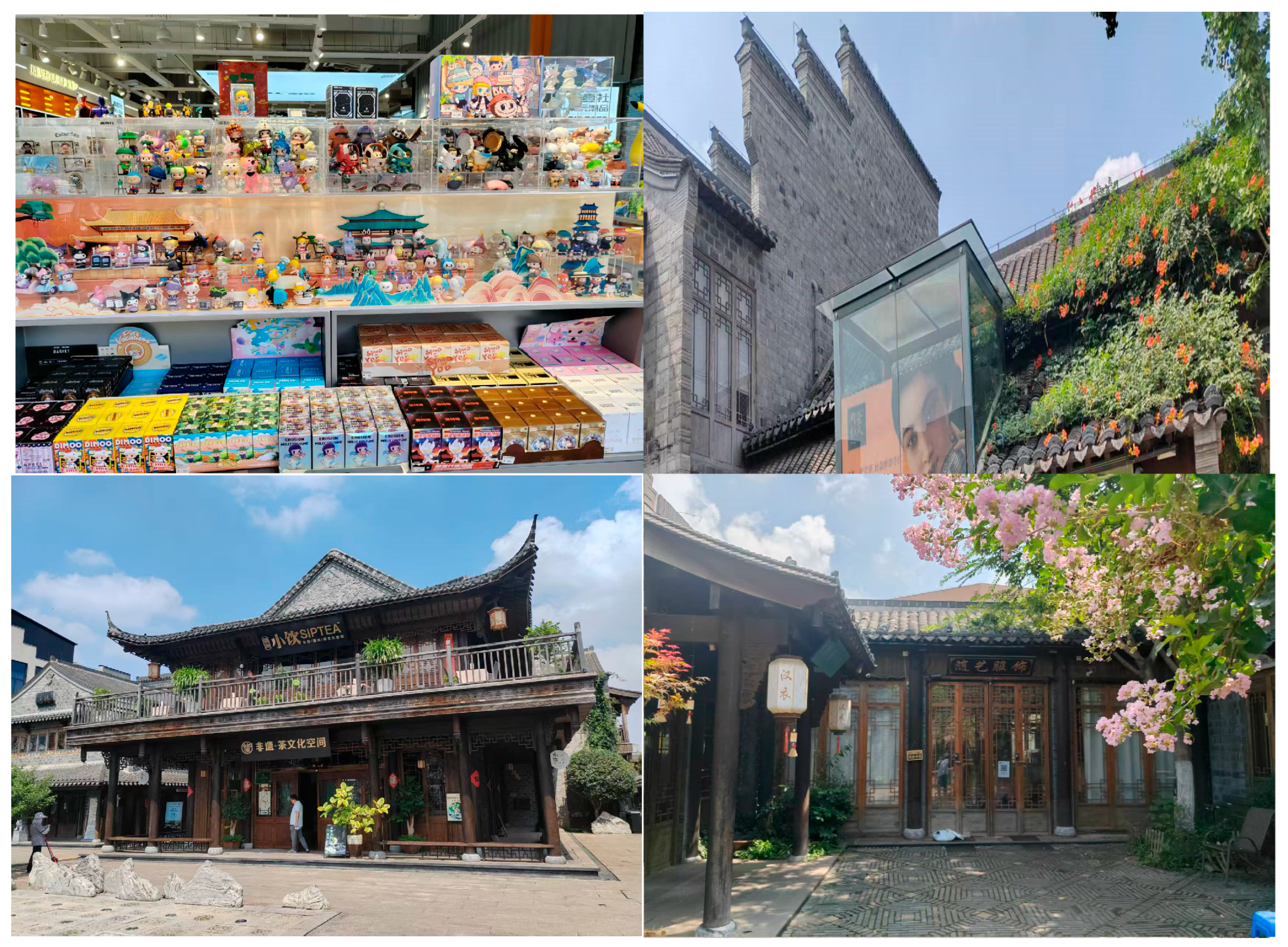

3.1. Field of Research

3.2. Research Methods

3.3. Questionnaire Design

3.4. Survey

4. Results

4.1. Demographics

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.3. Intensity Analysis

4.4. Assessment of Hypothesized Relationships

4.5. Structural Model

4.5.1. Relationship Between Tourists’ Perception of Tourism Gentrification and Tourist Satisfaction

4.5.2. Relationship Between Tourists’ Perception of Tourism Gentrification and Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior

4.5.3. Relationship Between Tourist Satisfaction and Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior

5. Discussion

5.1. Intensity Analysis

5.2. Tourists’ Perception of Tourism Gentrification and Tourist Satisfaction

5.3. Tourists’ Perception of Tourism Gentrification and Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior

5.4. Tourist Satisfaction and Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Significance

6.3. Shortcomings and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brockerhoff, M. World urbanization prospects: The 1996 revision. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1998, 24, 883–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolpin, D.W.; Furlong, E.T.; Meyer, M.T.; Thurman, E.M.; Zaugg, S.D.; Barber, L.B.; Buxton, H.T. Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in U.S. streams, 1999–2000: A national reconnaissance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Lopez, M.A. Urban spatial structure, suburbanization and transportation in Barcelona. J. Urban Econ. 2012, 72, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.W.; Campbell, H.S. The Suburbanization of producer service employment. Growth Change 2006, 28, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C.; Fowles, S.; Karecha, J. Reurbanization and housing markets in the central and inner areas of Liverpool. Plan. Pract. Res. 2009, 24, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, L.S. Reurbanization, uneven urban development, and the debate on new urban forms. Urban Geogr. 1996, 17, 690–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmon, N. Three generations of urban renewal policies: Analysis and policy implications. Geoforum 1999, 30, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, N.; O’Malley, B.W. Urban renewal in the nucleus: Is protein turnover by proteasomes absolutely required for nuclear receptor-regulated transcription? Mol. Endocrinol. 2004, 18, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Newman, K.; Wyly, E.K. The right to stay put, revisited: Gentrification and pesistance to displacement in New York City. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 23–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. New globalism, new urbanism: Gentrification as global urban strategy. Antipode 2002, 34, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoern, H. In between social engineering and gentrification: Urban restructuring, social movements, and the place politics of open space. J. Urban Aff. 2012, 34, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.F. Tourism gentrification: The case of New Orleans’ Vieux Carre (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinand, S.; Gravari, M. Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises: International Perspectives; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2017; pp. 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Janoschka, M.; Sequera, J.; Salinas, L. Gentrification in Spain and Latin America: A critical dialogue. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1234–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Chen, L.Q.; Long, C.; Duan, P.X. Tourism gentrification of traditional villages and towns in the suburbs of big cities in China: A case study of Zhujiajiao Ancient Town in Shanghai. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 2535–2553. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T. Tourism-led Rural Gentrification: Impacts and Residents’ Perception. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.H.; Sha, R. Study on self-driving tours in China and tourism gentrification. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 24, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kesar, O.; Dezeljin, R.; Bienenfeld, M. Tourism gentrification in the city of Zagreb: Time for a debate? Interdiscip. Manag. Res. 2015, 11, 657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Jackjon, R. Bruny on the brink: Governance, gentrification and tourism on an Australian island. Isl. Stud. J. 2006, 1, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobic, S.; Akhavan, M. Tourism gentrification in Mediterranean heritage cities. The necessity for multidisciplinary planning. Cities 2022, 124, 103616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Z.; Gu, C.H.; Li, D.H.; Huang, M.L. Tourism gentrification: Concept, type and mechanism. Tour. Tribune 2006, 21, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.M.; Chao, H.W.; Zhang, T.T. Advances and prospects in tourism gentrification research home and abroad. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 34, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, K.S.; Yiu, C.Y. Touristification, Airbnb and the tourism-led rent gap: Evidence from a revealed preference approach. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourkouridis, D.; Rizos, A.; Frangopoulos, I.; Salepaki, A. Airbnb and Urban Housing Dynamics: Economic and Social Impacts in Greece. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevrier, O.L. The Impact of Airbnb Expansion on Real Estate Speculation in Marseille’s Tourist Areas. Law Econ. 2024, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aritenang, A.F.; Iskandar, Z.S. Tourism gentrification and P2P accommodation: The case of Airbnb in Bandung City. City Cult. Soc. 2023, 35, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Seguel, C. Valparaíso: Touristification and displacement in a UNESCO city. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 46, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suariedewi, I.G.A.A.M.; Handriana, T.; Usman, I. Antecedents and consequences of tourism gentrification: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2025, 8, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Tao, W.; Lin, Q.Q. Advances in tourism gentrification studies: Theoretical context, research topics and paradigm innovation. J. Chin. Ecotour. 2023, 13, 740–761. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.Y.; Ai, L.J. A discussion on the phenomenon of tourism gentrification in urban historical and cultural districts—A case study of the south area of Nanjing Old City. China Anc. City 2018, 7, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez, J.M. The dispute over tourist cities. Tourism gentrification in the historic centre of Palma (Majorca, Spain). Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, K.; Jacobus, R. Retail trade as a route to neighborhood revitalization. Urban Reg. Policy Its Eff. 2009, 2, 19–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, K.S.; Yiu, C.Y. Unfolding touristification in retail landscapes: Evidence from rent gaps on high street retail. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 1224–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Takizawa, A. Population decline through tourism gentrification caused by accommodation in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speake, J.; Kennedy, V.; Love, R. Visual and aesthetic markers of gentrification: Agency of mapping and tourist destinations. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 756–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, S.; Lees, L.; Hubbard, P.; Tate, N. Measuring and mapping displacement: The problem of quantification in the battle against gentrification. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristos, A.V.; Smith, C.M.; Scherer, M.L.; Fugiero, M.A. More coffee, less crime? The relationship between gentrification and neighborhood crime rates in Chicago, 1991 to 2005. City Community 2011, 10, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.; Fortmann, L. Whose landscape? A political ecology of the‘exurban’Sierra. Cult. Geogr. 2003, 10, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.X.; Bao, J.G. Tourism gentrification in Shenzhen, China: Causes and socio-spatial consequences. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.Q.; Shi, C.Y.; Qian, Y.X.; Li, F. Rural spatial restructuring and its driving mechanism under the influence of tourism gentrification: A case study of Hanwang Village in Xuzhou City. Prog. Geogr. 2024, 43, 966–980. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, L.M.G.; Smith, N.; Vera, M.A.M. Gentrification, displacement, and tourism in Santa Cruz De Tenerife. Urban Geogr. 2007, 28, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L. Tourism gentrification in Lisbon: Neoliberalism, financialization and austerity urbanism in the period of the 2008–2009 capitalist post-crisis. Cad. Metróp. 2017, 19, 479–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Z.; Kou, M.; Lu, S.; Li, D.H. The characteristics and causes of urban tourism gentrification: A case of study in Nanjing. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 29, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, J.; Ahmed, U.; Roorda, M.; Habib, K.N. Measuring the process of urban gentrification: A composite measure of the gentrification process in Toronto. Cities 2022, 126, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Los Angeles Chinatown: Tourism, gentrification, and the rise of an ethnic growth machine. Amerasia J. 2008, 34, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuntsok, D.; Xu, X.M. Impacts of the gentrification of historical and cultural districts on the life quality of community residents: A case study of Barkhor in Lhasa. J. Yunnan Minzu Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2016, 33, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkster, F.M.; Boterman, W.R. When the spell is broken: Gentrification, urban tourism and privileged discontent in the Amsterdam canal district. Cult. Geogr. 2017, 24, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yrigoy, I. Airbnb in Menorca: A new form of touristic gentrification? Distribution of touristic housing dwelling, agents and impacts on the residential rent. Scr. Nova-Rev. Electron. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2017, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, L.; Amílcar, A.; Carreiras, M.; Guimarães, P. Master class “City Making & Tourism Gentrification”. Finisterra 2016, 51, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Pizam, A.; Neumann, Y.; Reichel, A. Dimensions of tourism satisfaction with a destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 1978, 5, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.B.; Raghed, M.G. Measuring leisure satisfaction. J. Leis. Res. 1980, 12, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.; Moscardo, G. Visitor evaluation: An appraisal of Foalsand techniques. Eval. Rev. 1985, 9, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eviana, N. Increasing Tourist Satisfaction Through Service Quality: The Mediating Role of Memorable Tourism Experience. Ilomata. Int. J. Manag. 2024, 5, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the Relationship Between Tourists’ Attribute Satisfaction and Overall Satisfaction. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Xiong, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Li, P.; Ryan, C. Tourist satisfaction with online car-hailing: Evidence from Hangzhou City, China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 2708–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, A.M.; Polizzi, G.; Parroco, A.M. Measuring Tourist Satisfaction Through a Dual Approach: The 4Q Methodology. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 146, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.A.; Qadir, N. Tourist Satisfaction in Kashmir: An Empirical Assessment. J. Bus. Theory Pract. 2013, 1, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Martínez, S.; Garau-Vadell, J.B. The Generation of Tourism Destination Satisfaction. Tour. Econ. 2010, 16, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permana, I.N.W.A.; Aryasih, P.A.; Puja, I.B. The Impact of Tour Guide Service Quality and Tourist Experience Towards Tourist Satisfaction in Discova Indonesia Tour and Travel. J. Travel Leis. 2024, 1, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Impact of tourist perceptions, destination image and tourist satisfaction on destination loyalty: A conceptual model. Pasos. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2013, 11, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süleyman, B.; Dogan, H.; Engin, U. Tourists’ perception and satisfaction of shopping in alanya region: A comparative analysis of different nationalities. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hassan, H.; Osman-Gani, A.; Abdel Fattah, F.A.M.; Anwar, M.A. Edu-tourist’s perceived service quality and perception-the mediating role of satisfaction from foreign students’ perspectives. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, R.; Ramirez, R. From value chain to value constellation: Designing interactive strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wan, W.H.; Wang, X.X. The two paradigms of co-Creating value and the frontier research review of co-creating in consumption Area. Econ. Manag. 2013, 35, 186–199. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-opting customer competence. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The co-creation connection. Strategy Bus. 2002, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.Q.; Linghu, K.R.; Li, L. The evolution and prospects of value co-creation research: A perspective from customer experience to service ecosystem. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2016, 38, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J.; Wyllie, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Voola, R. Enhancing brand relationship performance through customer participation and value creation in social media brand communities. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füller, J.; Mühlbacher, H.; Matzler, K.; Jawecki, G. Consumer empowerment through internet-based co-creation. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 26, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, J.; Füller, J.; Pezzei, R. The dark and the bright side of co-creation: Triggers of member behavior in online innovation communities. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1516–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Romero, C.; Constantinides, E.; Brunink, L.A. Co-creation: Customer integration in social media based product and service development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieven, T. Customers’ choice of a salesperson during the initial sales encounter. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to Theory and Research. Contemp. Sociol. 1977, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Chi, Y.Q. A review of consumer behavior research based on the Theory of Reasoned Action. J. Commer. Econ. 2016, 6, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, T. Developing and Validating a Scale of Tourism Gentrification in Rural Areas. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 1162–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Thuy, P.N. Customer participation to co-create value in human transformative services: A study of higher education and health care services. Serv. Bus. 2016, 10, 603–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, T.H. The study of the values of only- child generation: A scale development and test. J. Mark. Sci. 2007, 3, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Responses | Frequency | Percent | Variable | Responses | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 303 | 51.7 | Occupation | Self-employed | 73 | 12.5 |

| Female | 283 | 48.3 | Retirement | 21 | 3.6 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 327 | 55.8 | Other | 39 | 6.7 | |

| Unmarried | 251 | 42.8 | Monthly income | Less than RMB 2000 | 137 | 23.4 | |

| Other | 8 | 1.4 | RMB 2001–4000 | 31 | 5.3 | ||

| Age | less than 18 | 26 | 4.4 | RMB 4001–6000 | 127 | 21.7 | |

| 18–24 | 161 | 27.5 | RMB 6001–8000 | 200 | 34.1 | ||

| 25–34 | 236 | 40.3 | RMB > 8000 | 91 | 15.5 | ||

| 35–44 | 107 | 18.3 | Travel every year | Once or less | 133 | 22.7 | |

| 45–60 | 42 | 7.2 | 2–5 times | 258 | 44.2 | ||

| above 60 | 14 | 2.4 | 6–10 times | 125 | 21.3 | ||

| Education | Junior high school or less | 20 | 3.4 | More than 10 times | 69 | 11.8 | |

| High school | 60 | 10.2 | Information resources | Television | 34 | 5.8 | |

| Junior college | 70 | 11.9 | Newspapers and magazines | 19 | 3.2 | ||

| Bachelor | 347 | 59.2 | Relatives and friends | 149 | 25.4 | ||

| Master or more | 89 | 15.2 | Internet | 279 | 47.6 | ||

| Occupation | Student | 135 | 23 | Short video platforms such as TikTok and RedNote | 61 | 10.4 | |

| Government agency or public institution | 45 | 7.7 | Message | 7 | 1.2 | ||

| Private enterprise | 273 | 46.6 | Others | 37 | 6.3 |

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Standardized Factor Loading | CR | Average | Cronbach’s Alpha | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourists’ perception of tourism gentrification (TPTG) | ||||||

| Improved individual quality (IIQ) | IIQ1: has an open mind through tourism. | 0.741 *** | 0.808 | 0.585 | 0.848 | 0.803 |

| IIQ2: improves residents’ ability in communication. | 0.827 *** | |||||

| IIQ3: improves residents’ international education. | 0.722 *** | |||||

| Individual civilization (ICL) | ICL1: well-mannered through tourism. | 0.683 *** | 0.867 | 0.622 | 0.821 | 0.865 |

| ICL2: pay attention to image through tourism. | 0.798 *** | |||||

| ICL3: civilized through tourism. | 0.844 *** | |||||

| ICL4: show hospitality in tourism development. | 0.819 *** | |||||

| Enhanced living standards (ELS) | ELS1: better lives than other areas. | 0.722 *** | 0.815 | 0.525 | 0.745 | 0.787 |

| ELS2: live a comfortable life with tourism. | 0.702 *** | |||||

| ELS3: improves the healthcare here. | 0.758 *** | |||||

| ELS4: improves community management. | 0.714 *** | |||||

| Promoted social environment (PSE) | PSE1: improves the public health here. | 0.712 *** | 0.808 | 0.513 | 0.754 | 0.775 |

| PSE2: improves the service facilities here. | 0.701 *** | |||||

| PSE3: improves the public identification signage here. | 0.731 *** | |||||

| PSE4: improves the publicity here. | 0.721 *** | |||||

| Cultural appreciation (CA) | CA1: traditional culture is embodied. | 0.790 *** | 0.762 | 0.517 | 0.701 | 0.775 |

| CA2: plenty of tourism products with traditional here. | 0.732 *** | |||||

| CA3: traditional culture has been commercialized. | 0.691 *** | |||||

| Improved communication (IC) | IC1: honest to tourists. | 0.722 *** | 0.835 | 0.506 | 0.802 | 0.841 |

| IC2: increases residents’ honesty with tourists. | 0.781 *** | |||||

| IC3: abide strictly by the rules due to tourism. | 0.755 *** | |||||

| IC4: readily adopts tourists’ opinions. | 0.609 *** | |||||

| IC5: more willing to interact with tourists than other rural areas. | 0.675 *** | |||||

| Enhanced environment (EE) | EE1: improves the ecological environment. | 0.706 *** | 0.864 | 0.514 | 0.848 | 0.859 |

| EE2: improves the natural scenery here. | 0.750 *** | |||||

| EE3: increases residents’ awareness of ecological protection. | 0.730 *** | |||||

| EE4: improves residents’ sanitation here. | 0.744 *** | |||||

| EE5: improves the water quality here. | 0.711 *** | |||||

| EE6: improves residents’ living environment here. | 0.658 *** | |||||

| Tourist satisfaction (TS) | ||||||

| Tourist satisfaction (TS) | TS1: share with others about the pleasant experience of this trip. | 0.845 *** | 0.854 | 0.662 | 0.726 | 0.852 |

| TS2: recommend it to others. | 0.832 *** | |||||

| TS3: visit here again. | 0.761 *** | |||||

| Tourist value co-creation behavior (TVCB) | ||||||

| Tourist citizenship behavior (TCB) | TCB1: put forward suggestions for the development of the tourism | 0.890 *** | 0.934 | 0.781 | 0.857 | 0.933 |

| TCB2: cooperate with the work of tourism practitioners. | 0.906 *** | |||||

| TCB3: help other tourists to solve problems. | 0.929 *** | |||||

| TCB4: understand the service defects. | 0.805 *** | |||||

| Tourist participation behavior (TPB) | TPB1: learn the information through the internet, travel agencies and acquaintances. | 0.836 *** | 0.933 | 0.736 | 0.865 | 0.934 |

| TPB2: share what I have seen. | 0.912 *** | |||||

| TPB3: concern about environment. | 0.918 *** | |||||

| TPB4: pay attention to culture. | 0.819 *** | |||||

| TPB5: communicate my needs with the staff. | 0.798 *** | |||||

| Constructs | CA | PSE | IC | ICL | IIQ | ELS | EE | TS | TCB | TPB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural appreciation (CA) | 0.719 | |||||||||

| Promoted social environment (PSE) | 0.609 ** | 0.716 | ||||||||

| Improved communication (IC) | 0.531 ** | 0.612 ** | 0.711 | |||||||

| Enhanced living standards (ICL) | 0.397 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.788 | ||||||

| Improved individual quality (IIQ) | 0.385 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.646 ** | 0.765 | |||||

| Enhanced living standards (ELS) | 0.523 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.544 ** | 0.476 ** | 0.724 | ||||

| Enhanced environment (EE) | 0.499 ** | 0.714 ** | 0.594 ** | 0.484 ** | 0.398 ** | 0.635 ** | 0.717 | |||

| Tourist satisfaction (TS) | 0.379 ** | 0.428 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.304 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.814 | ||

| Tourist citizenship behavior (TCB) | 0.029 ** | −0.032 ** | 0.02 ** | 0.029 ** | 0.055 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.02 ** | 0.017 ** | 0.884 | |

| Tourist participation behavior (TPB) | −0.018 ** | 0.027 ** | −0.019 ** | 0.006 ** | 0.042 ** | 0.006 ** | −0.002 ** | −0.056 ** | −0.036 ** | 0.858 |

| Hypothesis | Hypothesis Path Relationship | Standardized Path Coefficient | Critical Ratio | p Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 Tourists’ perception of tourism gentrification → tourist satisfaction | |||||

| H1a | Improved individual quality → tourist satisfaction | 0.175 | 2.435 | 0.018 | supported |

| H1b | Individual civilization → tourist satisfaction | 0.18 | 2.978 | 0.003 | supported |

| H1d | Enhanced living standards → tourist satisfaction | 0.24 | 2.426 | 0.015 | supported |

| H1e | Improved communication → tourist satisfaction | 0.334 | 3.232 | 0.001 | supported |

| H1f | Cultural appreciation → tourist satisfaction | 0.465 | 3.417 | 0.000 | supported |

| H1g | Enhanced environment → tourist satisfaction | 0.216 | 2.222 | 0.026 | supported |

| H1h | Promoted social environment → tourist satisfaction | 0.126 | 3.164 | 0.02 | supported |

| Hypothesis | Hypothesis Path Relationship | Standardized Path Coefficient | Critical Ratio | p Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 Tourists’ perception of tourism gentrification → tourists’ value co-creation behavior | |||||

| H2a1 | Improved individual quality → tourist citizenship behavior | 0.158 | 2.287 | 0.022 | supported |

| H2a2 | Improved individual quality → tourist participation behavior | 0.113 | 1.204 | 0.229 | unsupported |

| H2b1 | Individual civilization → tourist citizenship behavior | 0.147 | 3.62 | 0.000 | supported |

| H2b2 | Individual civilization → tourist participation behavior | −0.044 | −0.474 | 0.635 | unsupported |

| H2d1 | Enhanced living standards → tourist citizenship behavior | 0.42 | 2.22 | 0.026 | supported |

| H2d2 | Enhanced living standards → tourist participation behavior | 0.303 | 3.179 | 0.001 | supported |

| H2e1 | Improved communication → tourist citizenship behavior | −0.091 | −0.609 | 0.542 | unsupported |

| H2e2 | Improved communication → tourist participation behavior | 0.574 | 1.957 | 0.048 | supported |

| H2f1 | Cultural appreciation → tourist citizenship behavior | 0.088 | 0.649 | 0.516 | unsupported |

| H2f2 | Cultural appreciation → tourist participation behavior | −0.058 | −0.556 | 0.578 | unsupported |

| H2g1 | Enhanced environment → tourist citizenship behavior | 0.065 | 0.4 | 0.689 | unsupported |

| H2g2 | Enhanced environment → tourist participation behavior | 0.695 | 2.155 | 0.031 | supported |

| H2h1 | Promoted social environment → tourist citizenship behavior | 0.602 | 1.981 | 0.048 | supported |

| H2h2 | Promoted social environment → tourist participation behavior | 0.148 | 3.824 | 0.000 | supported |

| Hypothesis | Hypothesis Path Relationship | Standardized Path Coefficient | Critical Ratio | p Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3 Tourist satisfaction → tourists’ value co-creation behavior | |||||

| H3a | Tourist satisfaction → tourist citizenship behavior | 0.03 | 0.313 | 0.754 | unsupported |

| H3b | Tourist satisfaction → tourist participation behavior | 0.136 | 3.269 | 0.001 | supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, N. Does Tourism Gentrification in Urban Areas Affect Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior? Land 2025, 14, 1778. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091778

Xu Y, Yao Z, Zhang Y, Zheng S, Wang R, Wang N. Does Tourism Gentrification in Urban Areas Affect Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior? Land. 2025; 14(9):1778. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091778

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yumei, Zhipeng Yao, Yechen Zhang, Shanting Zheng, Ruxing Wang, and Naiju Wang. 2025. "Does Tourism Gentrification in Urban Areas Affect Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior?" Land 14, no. 9: 1778. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091778

APA StyleXu, Y., Yao, Z., Zhang, Y., Zheng, S., Wang, R., & Wang, N. (2025). Does Tourism Gentrification in Urban Areas Affect Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Behavior? Land, 14(9), 1778. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091778