Research on the Protection and Development Model of Cultural Landscapes Guided by Natural and Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Post-Seismic Reconstruction of Dujiangyan Linpan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research on Cultural Landscape Conservation and Development

1.3. Evaluation System

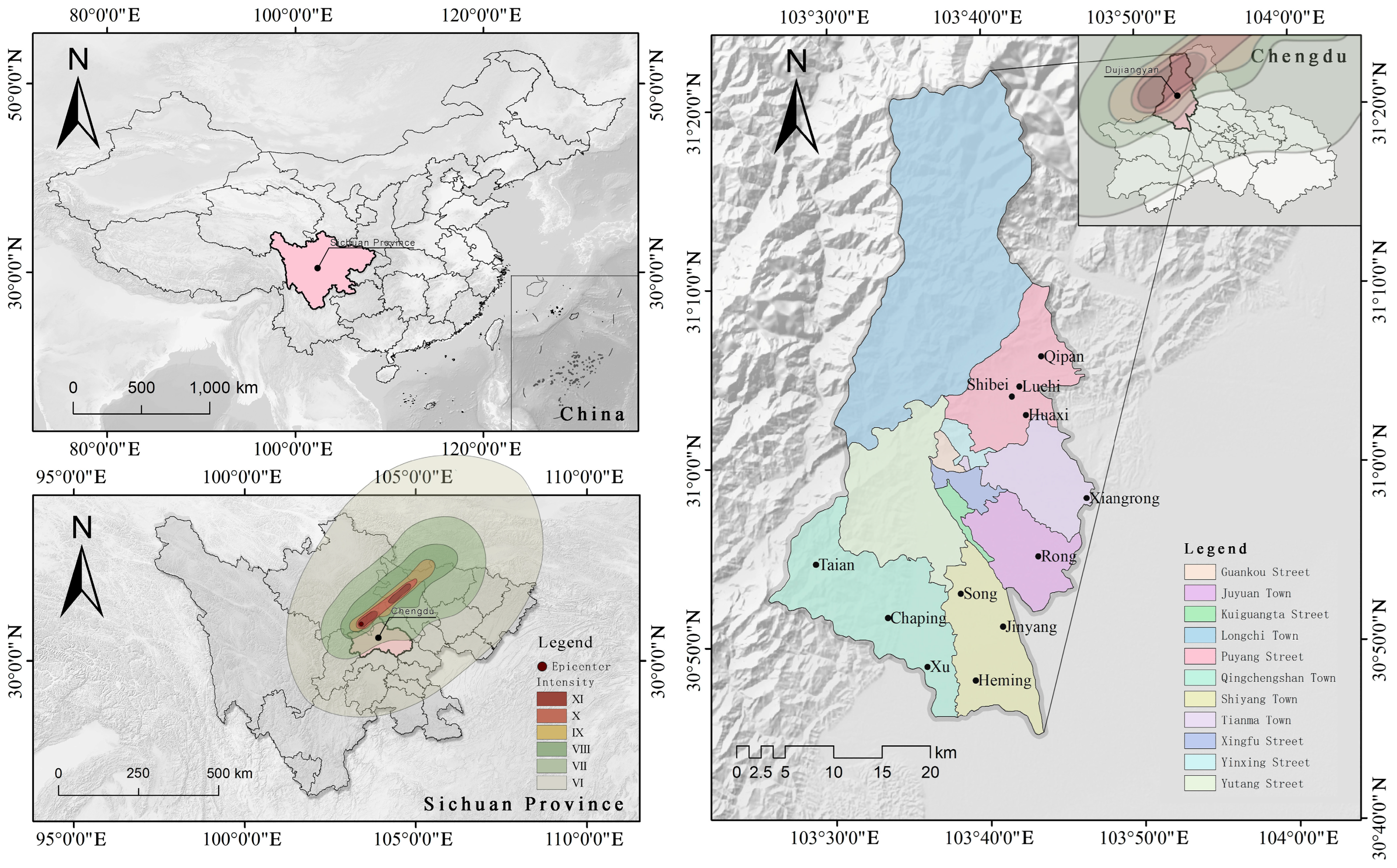

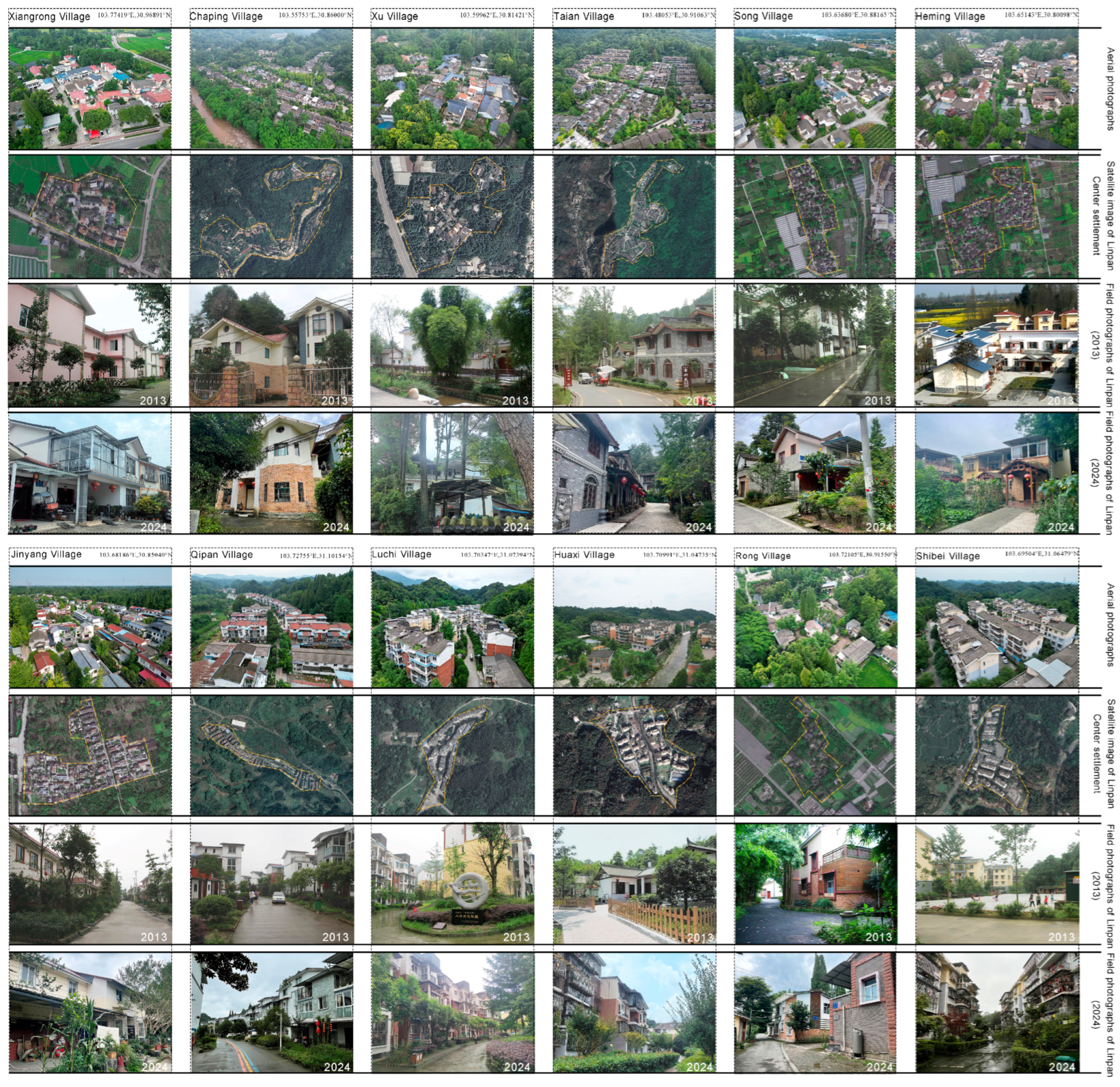

2. Study Areas

3. Research Methods and Data

3.1. Evaluation Method

3.2. Research Framework

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3.1. Construction and Data Collection of the Cultural Landscape Conservation Evaluation System

3.3.2. Construction and Data Collection of the Linpan Development Capability Evaluation System

3.4. Comprehensive Evaluation Model for Linpan Cultural Landscape Protection and Linpan Development Level

3.5. Coupling Coordination Degree Model for Evaluating the Cultural Landscape Protection and Development of Post-Disaster Reconstruction Linpan Settlements

3.5.1. Coupling Coordination Degree Model

3.5.2. Coordination Degree Model

3.5.3. Classification of Coupling Coordination Degree Model

4. Results Analysis and Discussion

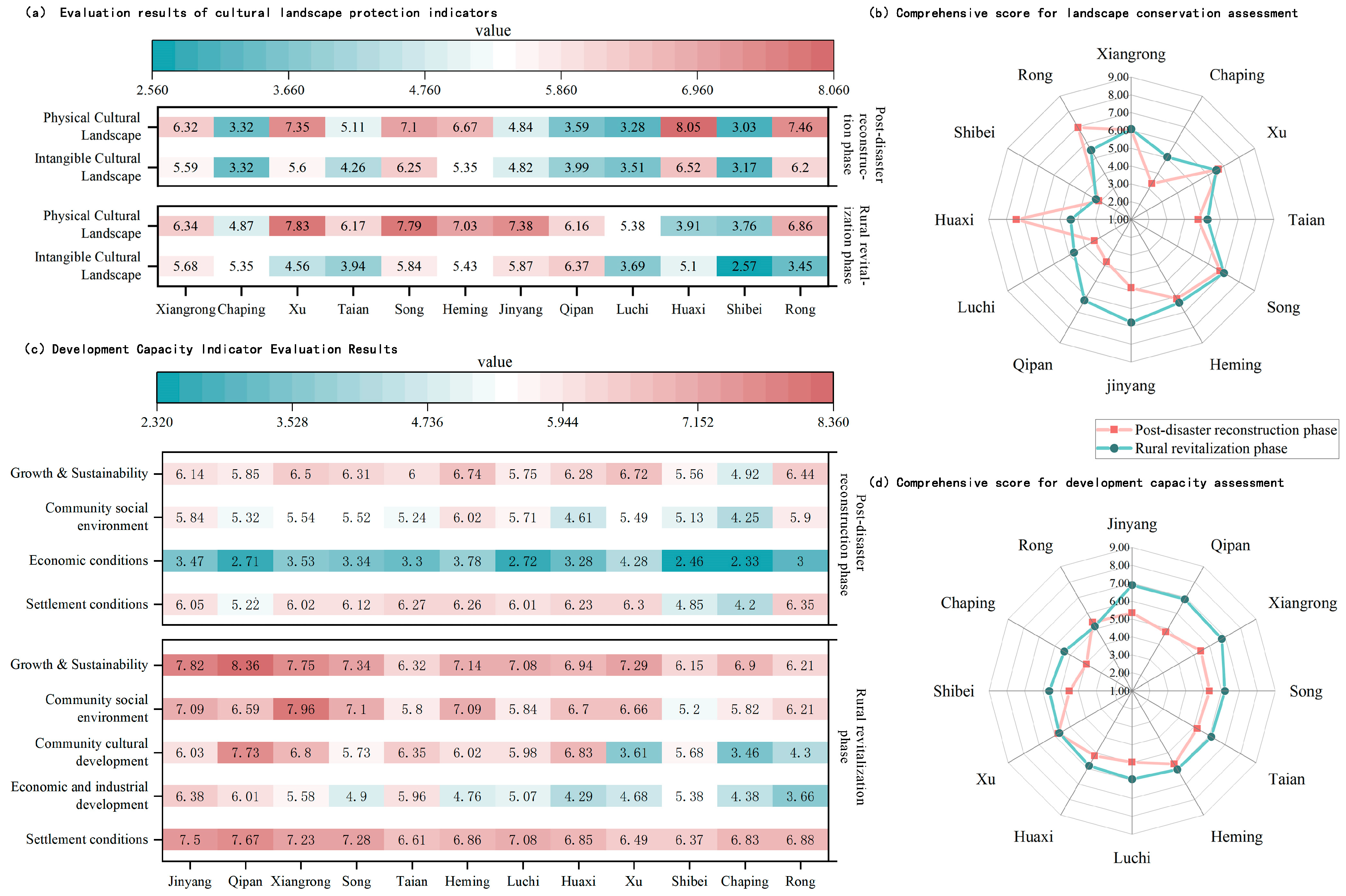

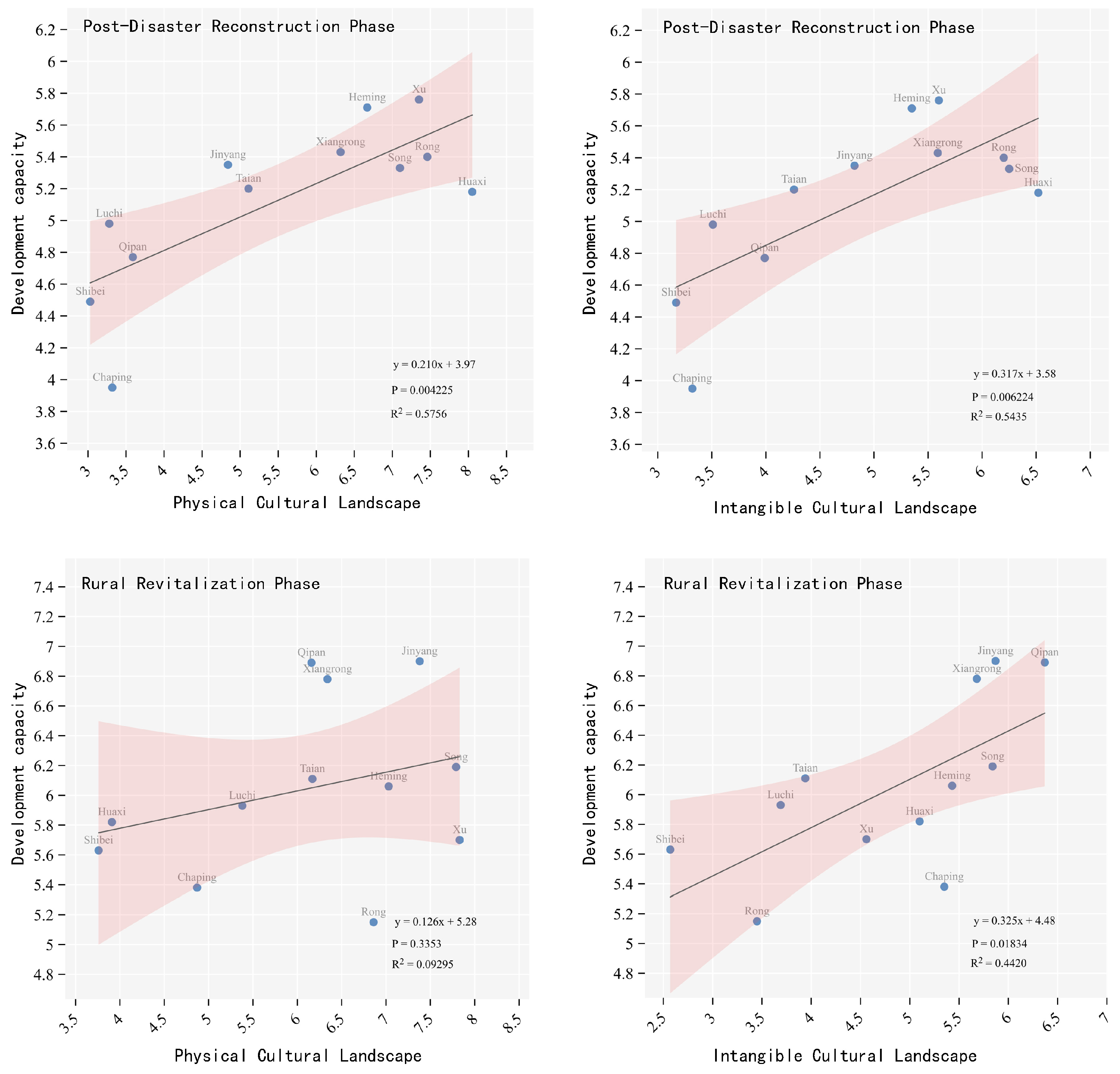

4.1. Evaluation Results of Linpan Cultural Landscape Protection and Development Capabilities

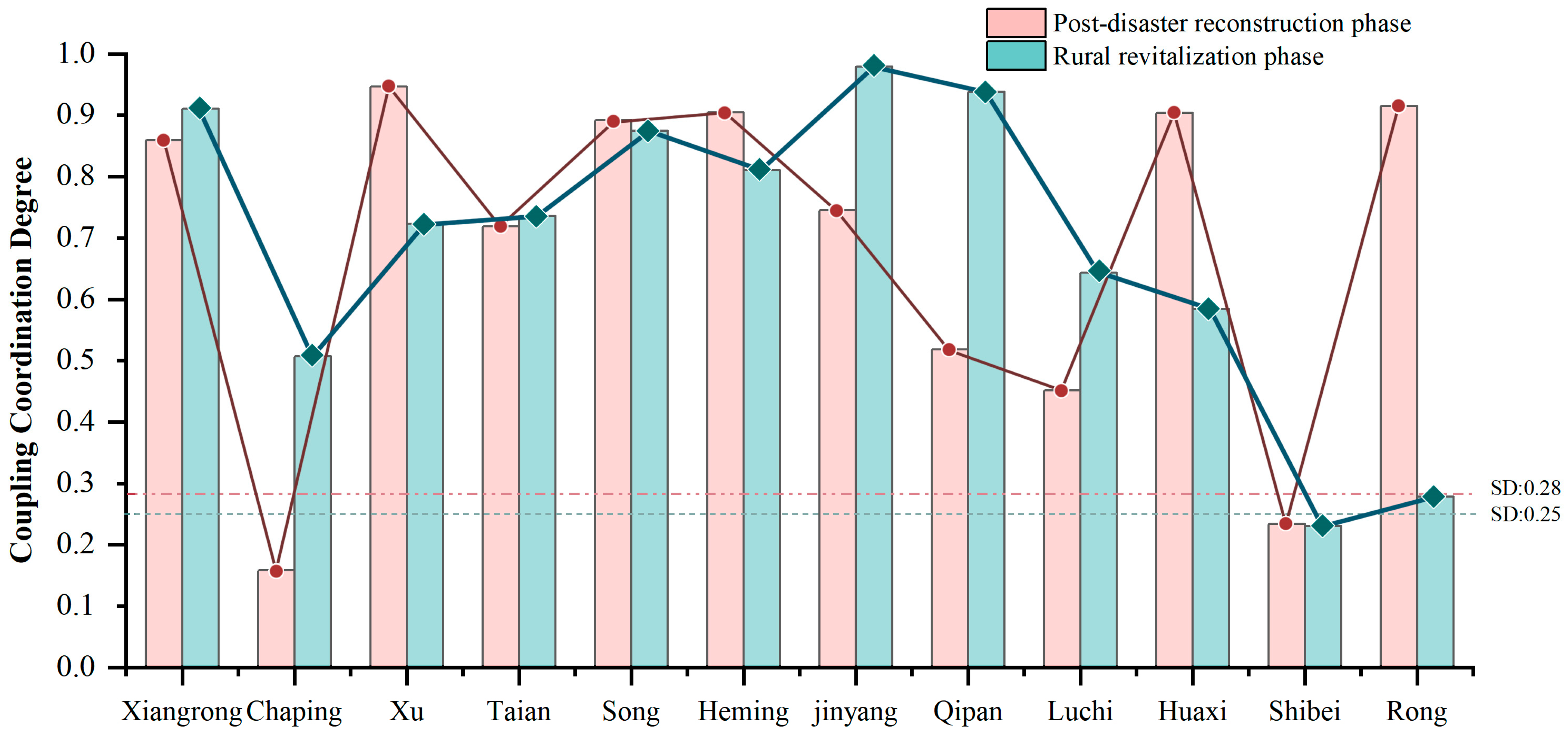

4.2. Coupling Results of Linpan Cultural Landscape Protection and Development Level

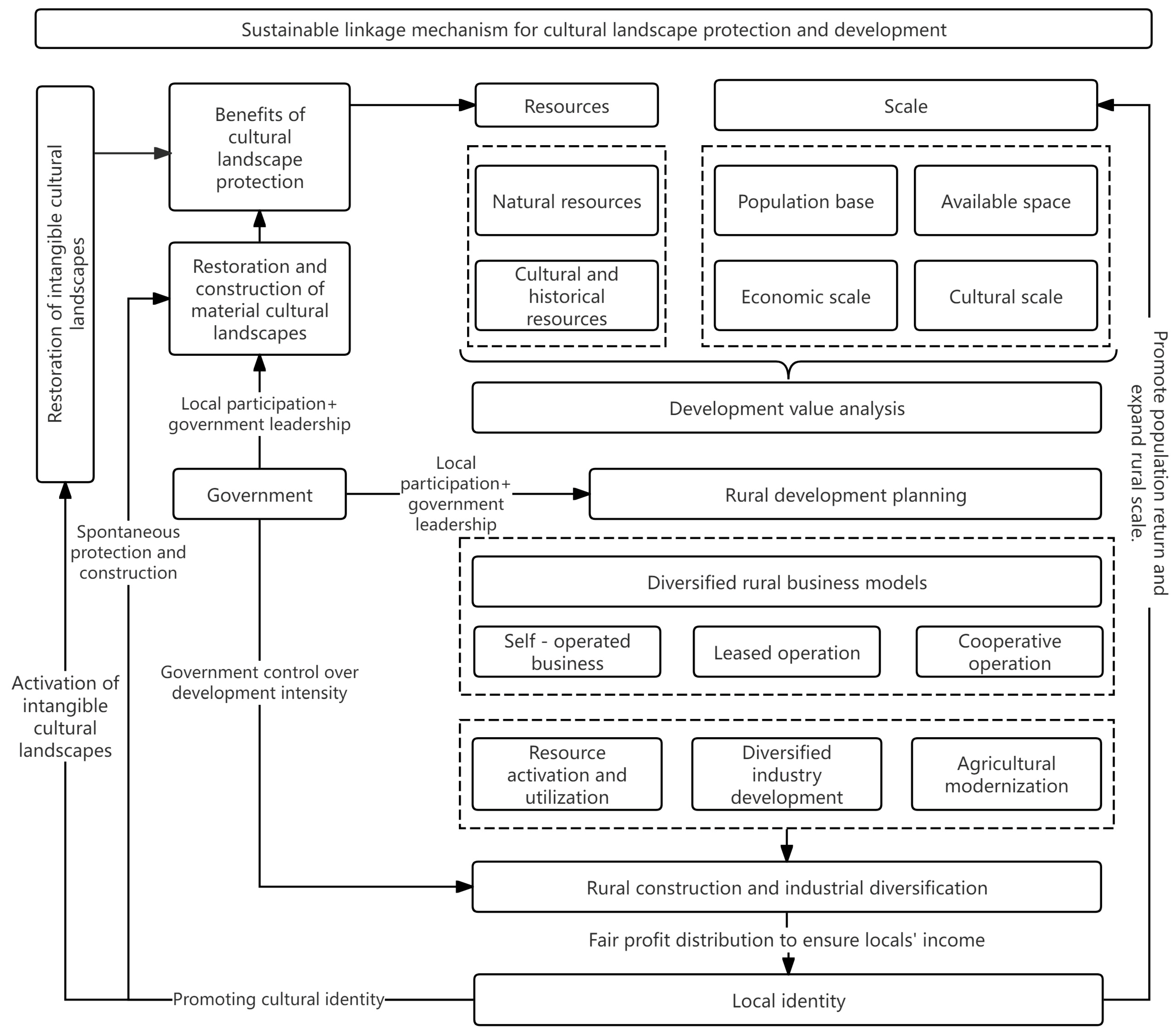

4.3. Analysis of the Linkage Mechanism Between Post-Disaster Reconstruction and the Protection and Development of Linpan Cultural Landscapes

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

5.2. Recommendations

- (1)

- Build an endogenous cyclic system. Based on the compound resource base of “fields–forests–houses–water” in Linpan, adopt the core path of “resource endowment exploration–community participation cultivation–dynamic mechanism construction” to promote the transformation of Linpan from “policy-driven” to “endogenous coordination.” It is recommended to systematically comb cultural, ecological, and industrial resources and actively introduce low-ecological-impact models to revitalize the cultural landscape and achieve value transformation.

- (2)

- Strengthen community participation. Establish systems such as “residents’ discussion meetings” to incorporate cultural heritage protection and industrial planning decisions into villagers’ self-governance, enhancing community belonging [55]. Meanwhile, improve the benefit linkage and distribution mechanism of “protection investment–industrial value added–benefit feedback” to ensure development benefits reach the community, forming a positive endogenous cycle of “internalizing development outcomes.”

- (3)

- Establish a dynamic monitoring and adaptation mechanism. Construct a monitoring system covering the dual dimensions of “protection efficiency” (e.g., preservation rate of material culture, sustainability of intangible culture) and “development quality” (e.g., community participation, industrial sustainability). Regularly engage third-party evaluations to continuously optimize policy support and corporate access standards, ensuring the mechanism dynamically matches the characteristics and developmental needs of Linpan.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pintossi, N.; Ikiz Kaya, D.; Pereira Roders, A. Assessing Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse Practices: Multi-Scale Challenges and Solutions in Rijeka. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO WHC; ICCROM; ICOMOS; IUCN. Managing Disaster Risks for World Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/managing-disaster-risks/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, E.; Gillespie, J. Under-utilisation of the World Heritage Cultural Landscape category? A timely question. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2024, 30, 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.R.; Li, X.K. Historical Causes of the Culture of the Linpan in Western Sichuan. J. Chengdu Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 5, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y. Sanxingdui and the Study of Ba and Shu Culture in the Past Seventy Years. Chin. Cult. Forum 2003, 3, 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.R.; Yang, D.X. Bashu Symbols: The Source and Vitality of Bashu Culture. Tianfu New Discourse 2021, 6, 2+161. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.X. The Chengdu Plain Is the Center of Ancient Civilization in the Upper Yangtze River. Chin. Cult. Forum 2003, 4, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H. The Present and Future of the Traditional Rural Settlement “Linpan” on the Chengdu Plain; Chinese Urban Planning Academic Season Rural Planning and Construction Committee: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, R.; Xu, Y.P. Spatial Production and Place Reconstruction: A Study on the Protection of Tusi Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Landscape Anthropology. Guangxi Ethn. Res. 2024, 2, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C.; Miller, P.; Katen, B. The Traditionality Evaluation of Culture Landscape Space and Its Holistic Conservation Pattern: A Case Study of Qiandeng-Zhangpu Region in Jiangsu Province. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2011, 4, 525–534. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.M.; Liu, X.J.; Zhao, S.B. Research on Cultural Landscape Preservation of New and Old Ditches in Haikou from the Perspective of ‘Production-living-ecological’ Spatial Optimization. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2023, 41, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.Q.; Zheng, R.N.; Ma, J. Landscape Characteristics and Conservation and Utilization Mechanisms of Composite Agricultural Heritage Systems in Japan. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 12, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.C.; Wang, C. Research on the Design of Activating Traditional Villages’ Cultural Landscape from the Perspective of Organic Regeneration: A Case Study of the Urban Village Located in Houxi Town, Xiamen. Archit. Cult. 2024, 6, 180–182. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Wu, J.M.; Liu, P.F.; Yu, Y.H. The Living Inheritance Path of Intangible Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Traditional Craft Revitalization-Taking Huang Yunpeng, the National Intangible Cultural Heritage Inheritor of Jingdezhen. J. Ceram. 2023, 2, 382–388. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.B.; Gao, W. Institutional Empowerment: Community Participation in the Conservation of Traditional Village Cultural Landscape of Guangdong Kaiping Watchtower. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 32, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Tang, C.C.; Liu, H.X.; Cui, M.R. Spatial characteristics and restructuring model of the agro-cultural heritage site in the context of culture and tourism integration. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ning, W. Mechanisms and effects of the sustainable integration of digital-driven rural cultural tourism from the perspective of symbiosis. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.L.; Xing, Y.J. Research Review and Prospects on the Linpan in Western Sichuan—Based on CiteSpace and VOS viewer. J. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2024, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.B. A Study on the Protection and Development of Linpan Landscape Resources in Western Sichuan; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, H.; Chen, X.H. A Study on the Ecological Wisdom of the Linpan Landscape in Western Sichuan; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.; Liu, J.Q. Value Realization Mechanism of Rural Ecological Resources: A Cross Case Study Based on Linpan in West Sichuan. Issues Agric. Econ. 2022, 11, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.S.; Ishikawa, M.; Wumaier, K. Analysis on the Sustainable Development Path of Traditiona Settlement of Linpan in Western Sichuan from the Perspective of Genetic Inheritance. Areal Res. Dev. 2020, 3, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.H.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y.C. Research Progress on Traditional Rural Cultural Landscapes. Prog. Geogr. 2008, 6, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.X.; Li, L.; Zhou, J.P.; Liu, C.J. The dynamic evolution and its driving mechanism of coordination of rural rejuvenation and new urbanization. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 2044–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.C.; Zhong, Z.P. Research on the Coupling Coordination Degree Between Tourism Industry and Regional Economy—A Case Study of Hunan Province. Tour. Trib. 2009, 8, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Yang, Z.F.; Chen, B. Landscape ecology planning of a scenery district based on a characteristic evaluation index system—A case study of the Wuyishan scenery district. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 13, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleni, V.; Apostolos, S.; George, M. Cultural heritage risk assessment in a changing rural Landscape: The case study of Northeastern Messenia, Greece. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2025, 38, e00425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, J.J.; Lyu, X.Y.; Sun, Y.Y.; Tan, C.D.; Zhang, B.; Paolo, T.; Yang, Q.C. An integrative conservation and management strategy based on biological and cultural diversity assessment: A case study of Miaoling mountainous region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171, 113187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Işık, C.; Yan, J.L.; Zhong, Q.K. Promoting the sustainable development of traditional villages: Exploring the comprehensive assessment, spatial and temporal evolution, and internal and external impacts of traditional village human settlements in hunan province. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assandri, G.; Bogliani, G.; Pedrini, P.; Brambilla, M. Beautiful agricultural landscapes promote cultural ecosystem services and biodiversity conservation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 256, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.Y.; Xiong, H.J.; Hu, H.Z.; Zhou, J.Y.; Wang, M. Integrating Risk-Conflict assessment for constructing and optimizing ecological security patterns of Polder landscape in the Urban-Rural fringe. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivathsa, A.; Vasudev, D.; Nair, T. Prioritizing India’s landscapes for biodiversity, ecosystem services and human well-being. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Landscape sustainability science (II): Core questions and key approaches. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 36, 2453–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. Prioritizing agricultural, rural development and implementing the rural revitalization strategy. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2019, 12, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Li, J.M.; Zeng, H.J.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhao, J. Analysis and Application Research of Weight Calculation Methods of Analytic Hierarchy Process. Math. Pract. Theory 2012, 7, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Z.; Si, Q. Data Statistical Processing Methods and Application Research in Delphi Method. J. Inn. Mong. Univ. Financ. (Compr. Ed.) 2011, 4, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Luo, Y.S.; Li, Y.Q.; Peng, P.H.; Zheng, S.W. Construction of Rural Landscape Quality Evaluation System Based on AHP Method—Taking Linpan in Western Sichuan as an Example. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2018, 2, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.D.; Zhang, X.Y.; Nie, C.J. Evaluation on Cultural Landscape Value and Sustainable Development of Traditional Villages under the Perspective of Live Protection: A Case Study of jingxing County, Hebei Province. Technol. Ind. 2025, 6, 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C.; Guo, H.C. Rural Economic Sustainable Development Indicator System and Evaluation in Luxi Plain—A Typical Case Study of Dongchangfu District. Econ. Geogr. 2000, 1, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.Z.; Wang, Q. Evaluation and Impact Analysis of Rural Human Settlements Quality in the Southern Anhui Tourism Area. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2013, 6, 851–867. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Y.F.; Huang, H.L. On the Significance, Classification, Evaluation and Protection Design of Rural Cultural Landscapes. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 28, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.G.; Dong, W.Q.; Zhang, R.S.; Chen, X.Y. Construction of Landscape Performance Evaluation System of Wetland-type Agricultural Cultural Heritage in the Yangtze River Delta Region: A Case Study of Gaoyou Agricultural Cultural Heritage. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 41, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.Y.; Wang, Y.C. On the Theoretical Basis and Indicator System for Rural Landscape Evaluation in China. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2002, 5, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wang, S. Construction on evaluation system of sustainable development for rural tourism destinations based on rural revitalization strategy. Geogr. Res. 2022, 41, 289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F. Endogenous Development Evaluation of Linpan Agricultural and Rural Complexes under Rural Revitalization. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Lin, J.Y.; Cui, S.H. A Review of Sustainable Development Evaluation Indicator Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 33, 99–105, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.H.; Zhou, J.; Wei, B.J.; Xiao, Q.H.; Wang, W.L. Integrated Rural Landscape Evaluation Based on Sustainable Human Settlements Development: A Case Study of Touche Village, Longshan County, Hunan Province. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2023, 51, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.Q. Research and Practice on the Development Potential Evaluation of Traditional Villages in the Guang-fo Area. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D.; Gao, L.; Zhang, H.B.; Zhao, C.Z.; Shen, Y.C.; Shinfuku, N. Post-earthquake quality of life and psychological well-being: Longitudinal evaluation in a rural community sample in northern China. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000, 54, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Sunindijo, R.; Lestari, F. Users’ long-term satisfaction with post-disaster permanent housing: A case study of 2010 Merapi Eruption, Indonesia. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 192, 02066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, L.; Miller-Karas, E. A case for using biologically-based mental health intervention in post-earthquake China: Evaluation of training in the trauma resiliency model. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health 2009, 11, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- KamacI-Karahan, E.; Kemec, S. Residents’ satisfaction in post-disaster permanent housing: Beneficiaries vs. non-beneficiaries. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 73, 102901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhou, X. The dynamic relationship among digital inclusive finance, integration of industries in rural areas, and rural revitalization. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 85, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.B.; Su, Q. A Study on the Relationship Between Community Participation in Rural Tourism, Residents’ Perception of Tourism Impacts and Community Belongingness—A Case Study of Rural Tourism in Anji, Zhejiang. Tour. Trib. 2011, 26, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.G. The Origin, Development and Evolution of the Theory of Polycentric Governance. J. Southeast Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2009, S2, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.H. The Origin, Development and Divergence of Contract Theory. Comp. Econ. Soc. Syst. 2017, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.J. Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, 1st ed.; Ningxia People’s Education Press: Ningxia, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Cultural Economics: The Arts, the Heritage, and the State; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y. Research on the Theory and Practice of Cultural—Tourism Integration, 1st ed.; Cultural Development Press: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, J.; Li, G.; Xiao, D.W.; Zhuo, X.L. Research progress and prospect of traditional rural settlements in China. S. Archit. 2024, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Laurajane, S. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social Capital and Community Resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmen, E.; Fazey, I.; Ross, H.; Bedinger, M.; Smith, F. Building community resilience in a context of climate change: The role of social capital. Ambio 2022, 51, 1371–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Population | Size of Linpan | Major Development Industries (Field Research) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Disaster Reconstruction Phase | Rural Revitalization Phase | |||

| Xiangrong Village | 1767 | Large | Agriculture, processing and sales of agricultural and sideline products. | Complex industry linkage, rural tourism-based (flower and tree planting, specialty lodging) |

| Chaping Village | 1384 | Large | Development of agriculture and poultry farming is the main focus | Complex industry linkage (tea planting), rural tourism-based |

| Xu Village | 152 | Small | Transition from traditional to modern agriculture, vigorously develop the seedling industry | Modern agriculture, sideline-oriented, development of the bonsai and seedling industry, (nanmu planting, wood crafts sales) |

| Taian Village | 1468 | Large | Leading the development of eco-tourism and creative industries | Leading in the development of eco-tourism (Taian Ancient Town), creative industries, and sales of specialty products |

| Song Village | 419 | Medium | Grain and vegetable cultivation as the mainstay, transitioning from traditional to modern agriculture | Focus on the development of modern agriculture (grain and vegetable cultivation, viticulture) |

| Heming Village | 1800 | Large | Transformation of traditional agriculture to modern agriculture with the flower industry as the main focus | Complex industry linkage (flower and nursery industry) |

| Jinyang Village | 2751 | Large | Transformation from traditional to modern agriculture and development of the tourism industry | Complex industry linkage (seedling ginkgo industry), rural tourism-oriented |

| Qipan Village | 838 | Medium | Transformation from traditional to modern agriculture and development of the tourism industry | Composite industrial linkage (kiwifruit industry, the industry of Sanmu medicinal materials) |

| Luchi Village | 733 | Medium | Transformation from traditional to modern agriculture and development of the tourism industry | Complex industry linkage (tea planting, rural tourism mainly) |

| Huaxi Village | 2028 | Large | Transition from traditional to modern agriculture, with grain and vegetable cultivation and rural tourism as the mainstay | Grain and vegetable cultivation, rural tourism mainly |

| Shibei Village | 1401 | Large | Transformation from traditional to modern agriculture and initial development of the tourism industry | Complex industry linkage (tea planting, rural tourism mainly) |

| Rong Village | 141 | Small | Building modern agriculture, creating an agricultural science and technology industrial park, and initially developing the tourism industry | Developing modern agriculture, with grain and oil cultivation, edible fungus cultivation and seedling planting as the main industries |

| Target Layer | Indicator Layer | Weight | Factor Layer | Weight | Hierarchical Total Sorting Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linpan landscape protection evaluation (U1) | Degree of physical cultural landscape protection | 0.60 | Degree of architectural landscape Protection | 0.16 | 0.096 |

| Degree of forest landscape protection | 0.22 | 0.132 | |||

| Degree of field landscape protection | 0.15 | 0.090 | |||

| Degree of water landscape protection | 0.15 | 0.090 | |||

| Degree of preservation of rural settlement patterns | 0.33 | 0.198 | |||

| Degree of intangible cultural landscape protection | 0.40 | Degree of agricultural culture protection | 0.29 | 0.116 | |

| Degree of traditional lifestyle retention | 0.28 | 0.112 | |||

| Degree of folklore retention | 0.30 | 0.120 | |||

| Degree of retention of productive activities | 0.14 | 0.056 |

| Target Layer | Indicator Layer | Weight | Factor Layer | Description of Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linpan development capacity (U2) | Growth and sustainability | 0.34 | Psychological recovery | Degree of recovery of disaster victims’ psychological state |

| Quality of life recovery | Improvement in the living conditions of disaster victims | |||

| Housing design | Degree of integration between housing design and local culture | |||

| Housing satisfaction | Satisfaction with various aspects of housing | |||

| Community satisfaction | Satisfaction with various aspects of the community | |||

| Community social environment | 0.17 | Safety | Rural security and risk resistance | |

| Sanitation | Neighborhood sanitation and tidiness | |||

| Rural transportation | Accessibility of rural roads | |||

| leisure facility | Availability of leisure and entertainment facilities and venues | |||

| Community infrastructure | Completeness of various types of infrastructure | |||

| Convenience of shopping | Distance to shopping places and their richness | |||

| Accessibility of education | Richness of educational resources | |||

| Accessibility of healthcare | Richness of medical resources | |||

| Economic conditions | 0.27 | Household durable goods | Ownership of durable goods, such as household appliances | |

| Other household property | Situation of assets other than durable goods | |||

| Local employment opportunities | Richness of job opportunities around housing | |||

| Household income situation | Level of family economic income | |||

| Settlement conditions | 0.22 | Housing hardware facilities | Quality of water, electricity, and gas facilities. | |

| House structure | Safety of house structure | |||

| House space | Rationality of room layout and other functions | |||

| House usability | Situation of usable space in the house | |||

| Housing comfort | Comfort of lighting, ventilation, etc. | |||

| Building appearance | Aesthetic appeal of house facade | |||

| Building density | Density of buildings | |||

| Commuting situation | Distance to workplace and transportation |

| Target Layer | Indicator Layer | Weight | Factor Layer | Description of Indicators |

| Linpan development capacity (U2) | Growth and sustainability | 0.15 | Psychological recovery | Degree of recovery of disaster victims’ psychological state |

| Quality of life | Comprehensive situation of life | |||

| Housing satisfaction | Satisfaction with various aspects of housing | |||

| Community satisfaction | Satisfaction with various aspects of the community | |||

| Community social environment | 0.22 | Sanitation | Neighborhood sanitation and tidiness | |

| Rural transportation | Accessibility and convenience of transportation | |||

| Convenience of shopping | Distance to shopping places and their richness | |||

| Accessibility of education | Richness of educational resources | |||

| Accessibility of healthcare | Richness of medical resources | |||

| Safety | Rural security situation | |||

| Community cultural development | 0.08 | Configuration of cultural facilities | Types and quantities of cultural facilities | |

| Richness of holiday activities | Diversity of cultural and entertainment activities during holidays | |||

| Richness of activity venues | Number and types of sports and cultural activity venues | |||

| Economic and industrial development | 0.39 | Local employment opportunities | Richness of job opportunities around housing | |

| Household income situation | Level of family economic income | |||

| Richness of local specialty products | Types and quantities of local specialty products | |||

| Development of local tourism | Scale and benefits of the tourism industry | |||

| Richness of local enterprises | Number and industry diversity of local enterprises | |||

| Settlement conditions | 0.16 | Condition of hardware facilities | Quality of water and electricity facilities | |

| Safety of house structure | Safety of house structure | |||

| Comfort of housing | Comfort of lighting, ventilation, etc. | |||

| Building appearance | Aesthetics and harmony of house facade | |||

| Building density | Density of buildings |

| Survey Year | Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Gender | Male | 81 | 48.50% |

| Female | 86 | 51.50% | ||

| Age | 18~30 | 14 | 8.38% | |

| 31~45 | 42 | 25.15% | ||

| 46~60 | 60 | 35.93% | ||

| 61~75 | 40 | 23.95% | ||

| >76 | 11 | 6.59% | ||

| Employment situation | Farming | 67 | 40.12% | |

| Migrant worker | 65 | 38.92% | ||

| Government agency or public institution | 6 | 3.59% | ||

| Corporate entity | 12 | 7.19% | ||

| Sole proprietorship | 17 | 10.18% | ||

| 2024 | Gender | Male | 110 | 47.62% |

| Female | 121 | 52.38% | ||

| Age | 18~30 | 24 | 10.39% | |

| 31~45 | 61 | 26.41% | ||

| 46~60 | 75 | 32.47% | ||

| 61~75 | 55 | 23.81% | ||

| >76 | 16 | 6.92% | ||

| Employment situation | Farming | 72 | 31.17% | |

| Migrant worker | 87 | 37.66% | ||

| Government agency or public institution | 13 | 5.63% | ||

| Corporate entity | 23 | 9.96% | ||

| Sole proprietorship | 36 | 15.58% |

| Sample | Post-Disaster Reconstruction Phase | Rural Revitalization Phase | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coupling Degree (C) | Coordination Index (T) | Coupling Coordination Degree (D) | Coordination Level | Coupling Degree (C) | Coordination Index (T) | Coupling Coordination Degree (D) | Coordination Level | |

| Xiangrong | 0.996 | 0.742 | 0.859 | 9 | 0.994 | 0.834 | 0.911 | 10 |

| Chaping | 0.692 | 0.036 | 0.158 | 2 | 0.835 | 0.308 | 0.507 | 6 |

| Xu | 0.995 | 0.901 | 0.947 | 10 | 0.888 | 0.590 | 0.723 | 8 |

| Taian | 0.961 | 0.538 | 0.719 | 8 | 1.000 | 0.542 | 0.736 | 8 |

| Song | 0.999 | 0.797 | 0.892 | 9 | 0.968 | 0.791 | 0.875 | 9 |

| Heming | 0.987 | 0.830 | 0.905 | 10 | 0.974 | 0.673 | 0.810 | 9 |

| Jinyang | 0.950 | 0.585 | 0.745 | 8 | 1.000 | 0.960 | 0.979 | 10 |

| Qipan | 0.876 | 0.306 | 0.518 | 6 | 0.994 | 0.886 | 0.938 | 10 |

| Luchi | 0.636 | 0.320 | 0.451 | 5 | 0.997 | 0.415 | 0.643 | 7 |

| Huaxi | 0.982 | 0.833 | 0.904 | 10 | 0.993 | 0.343 | 0.584 | 6 |

| Shibei | 0.352 | 0.156 | 0.234 | 3 | 0.366 | 0.144 | 0.230 | 3 |

| Rong | 0.999 | 0.838 | 0.915 | 10 | 0.255 | 0.302 | 0.278 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, Y.; Yang, J. Research on the Protection and Development Model of Cultural Landscapes Guided by Natural and Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Post-Seismic Reconstruction of Dujiangyan Linpan. Land 2025, 14, 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091753

Su Y, Yang J. Research on the Protection and Development Model of Cultural Landscapes Guided by Natural and Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Post-Seismic Reconstruction of Dujiangyan Linpan. Land. 2025; 14(9):1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091753

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Yuxiao, and Jie Yang. 2025. "Research on the Protection and Development Model of Cultural Landscapes Guided by Natural and Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Post-Seismic Reconstruction of Dujiangyan Linpan" Land 14, no. 9: 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091753

APA StyleSu, Y., & Yang, J. (2025). Research on the Protection and Development Model of Cultural Landscapes Guided by Natural and Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Post-Seismic Reconstruction of Dujiangyan Linpan. Land, 14(9), 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091753