Urban Tree CO2 Compensation by Albedo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

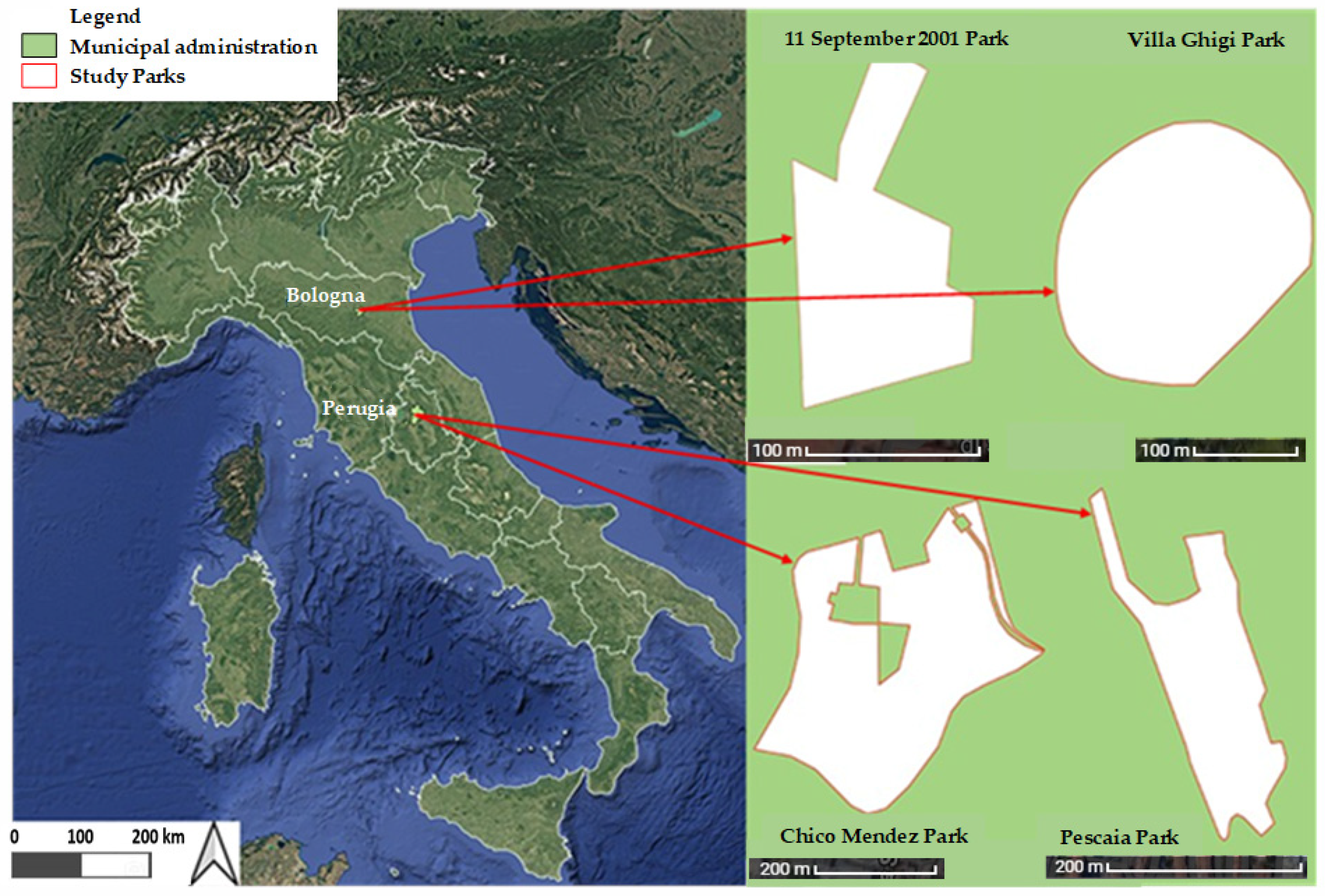

2.1. Study Areas

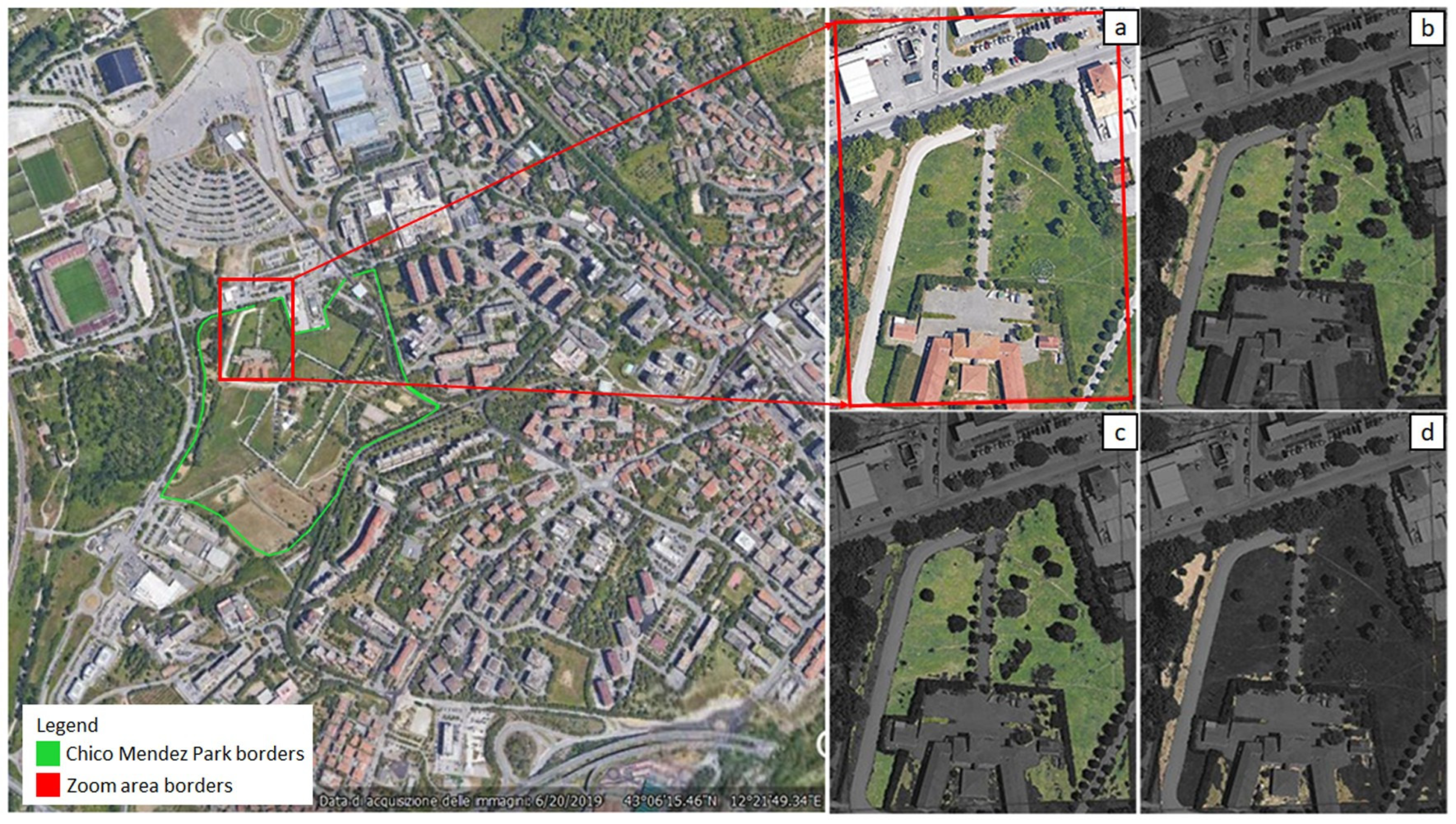

2.2. Assessment of the Different Parks’ Surface Areas

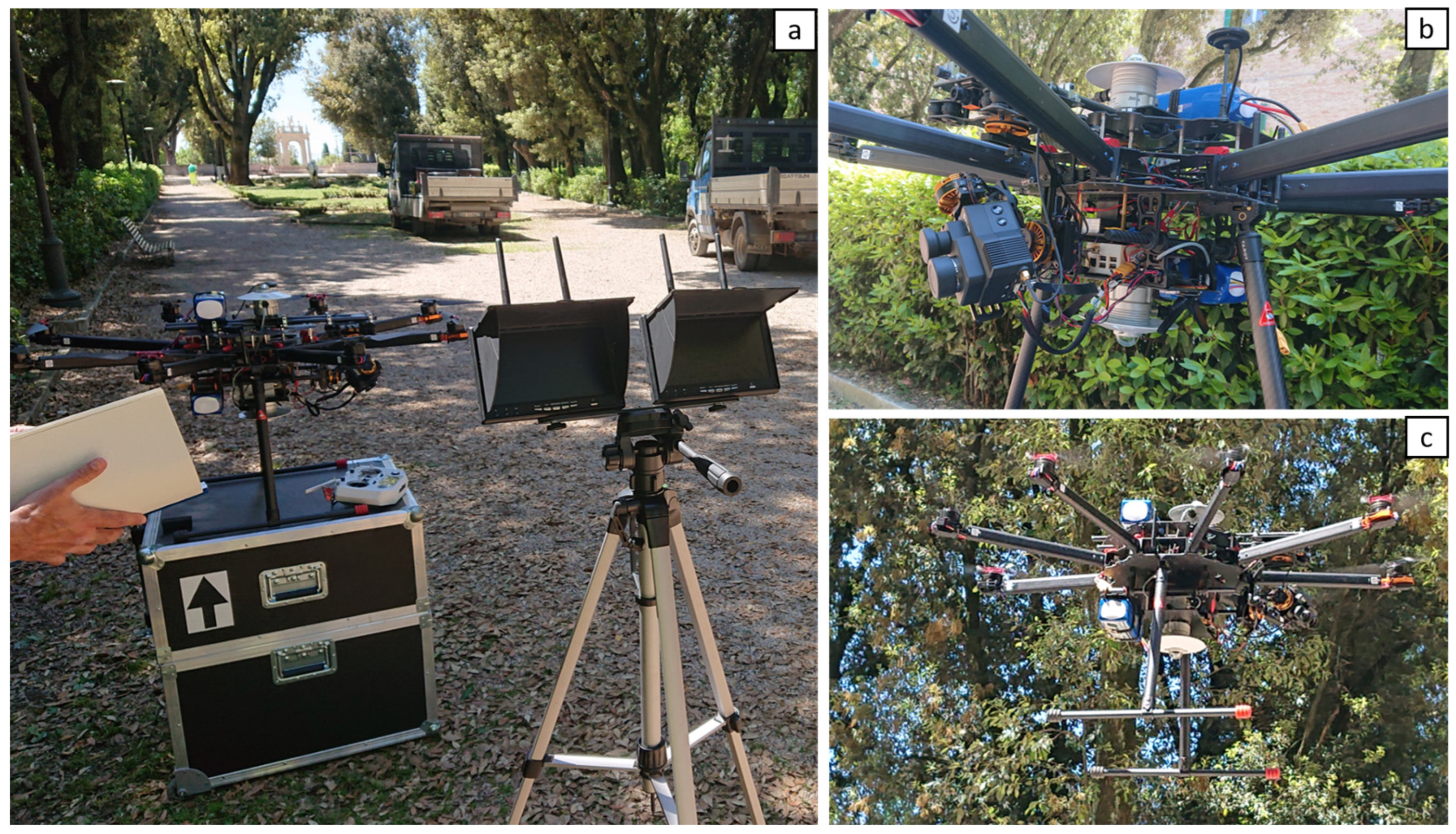

2.3. Albedo Assessment

2.4. Albedo Influence on Radiative Forcing (RF)

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- Albedo Contribution of Urban Parks:

- -

- Limited Albedo-Based Mitigation from Trees:

- -

- Importance of Synergistic Ecosystem Services:

- -

- Call for Integrative Assessment Approaches:

- -

- Species Selection and Albedo Optimization:

- -

- Need for Further Research and Data:

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIRIAF | Interuniversity Centre for Research on Pollution and the Environment “Mauro Felli” |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CO2eq | CO2 Equivalents (unit of measure) |

| ES | Ecosystem Services |

| ETP | Evapotranspiration |

| GHG | Green House Gases |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change |

| IRTA | Institut de Recerca y Tecnologia Agroalimentàries |

| PM10 | Particulate Matter (with a diameter of 10 μm or less) |

| Q | Potential Heat Reduction (W) |

| RF | Radiative Forcing |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

References

- Hayes, A.T.; Jandaghian, Z.; Lacasse, M.A.; Gaur, A.; Lu, H.; Laouadi, A.; Ge, H.; Wang, L. Nature-Based Solutions (NBSs) to Mitigate Urban Heat Island (UHI) Effects in Canadian Cities. Buildings 2022, 12, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.H. Projecting population growth as a dynamic measure of regional urban warming. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkstein, L.S.; Eisenman, D.P.; de Guzman, E.B.; Sailor, D.J. Increasing trees and high-albedo surfaces decreases heat impacts and mortality in Los Angeles, CA. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Singh, S.; Mall, R.K. Urban ecology and human health: Implications of urban heat island, air pollution and climate change nexus. In Urban Ecology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, K.; Licker, R.; Abatzoglou, J.T. Increased frequency of and population exposure to extreme heat index days in the United States during the 21st century Increased frequency of and population exposure to extreme heat index days in the United States during the 21st century. Environ. Res. Commun. 2019, 1, 075002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Rybski, D.; Kropp, J.P. The role of city size and urban form in the surface urban heat island. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandaghian, Z.; Akbari, H. Energy & Buildings Increasing urban albedo to reduce heat-related mortality in Toronto and Montreal, Canada. Energy Build. 2021, 237, 110697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Brown, R.D. Urban heat island (UHI) variations within a city boundary: A systematic literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 148, 111256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Energy Consumption and Environmental Quality of the Building Sector. In Minimizing Energy Consumption, Energy Poverty and Global and Local Climate Change in the Built Environment: Innovating to Zero; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 29–64. [Google Scholar]

- Klopfer, F.; Westerholt, R. Conceptual Frameworks for Assessing Climate Change Effects on Urban Areas: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Vasilakopoulou, K.; Santamouris, M. Exploring the potential impacts of anthropogenic heating on urban climate during heatwaves. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilby, R.L. Past and projected trends in London’s urban heat island. Weather 2003, 58, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.C.R.; Maslin, M.; Killeen, T.; Backlund, P.; Schellnhuber, J. Introduction. Climate change and urban areas: Research dialogue in a policy framework. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2007, 365, 2615–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Roesler, J. Aging albedo model for asphalt pavement surfaces. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 117, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R.W.; Christy, J.R.; Braswell, W.D. Urban Heat Island Effects in U.S. Summer Surface Temperature Data, 1895–2023. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2025, 64, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnfield, J.A. Two decades of urban climate research: A review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island. Int. J. Climatol. 2003, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Zhang, T.; Qin, Y.; Tan, Y.; Liu, J. A comparative review on the mitigation strategies of urban heat island (UHI): A pathway for sustainable urban development. Clim. Dev. 2023, 15, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L.; Sun, X.; Li, Y. Exploring the relationships between urban forms and fi ne particulate (PM 2.5) concentration in China: A multi-perspective study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 990–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, B.; Zhan, Q.; Gao, S.; Li, R.; Fan, Z. The influence of urban form on surface urban heat island and its planning implications: Evidence from 1288 urban clusters in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 71, 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, S.; Vettorato, D. Urban surface uses for climate resilient and sustainable cities: A catalogue of solutions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, M.V.; Sevin, S. Urban heat island effects of concrete road and asphalt pavement roads. In The Role of Exergy in Energy and the Environment; Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doick, K.; Hutchings, T. Air Temperature Regulation by Urban Trees and Green Infrastructure; Forestry Commission: Bristol, UK, 2013. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259889679_Air_temperature_regulation_by_urban_trees_and_green_infrastructure (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Lopez-cabeza, V.P.; Alzate-gaviria, S.; Diz-mellado, E.; Rivera-gomez, C.; Galan-marin, C. Albedo influence on the microclimate and thermal comfort of courtyards under Mediterranean hot summer climate conditions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 81, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y. A review on the development of cool pavements to mitigate urban heat island effect. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Harvey, J.T.; Holland, T.J.; Kayhanian, M. The use of reflective and permeable pavements as a potential practice for heat island mitigation and stormwater management. Envrionmental Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 015023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colunga, M.L.; Cambrón-sandoval, V.H.; Suzán-azpiri, H.; Guevara-escobar, A.; Luna-soria, H. The role of urban vegetation in temperature and heat island effects in Querétaro city, Mexico. Atmósfera 2015, 28, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosset, M.; Riedo, M.; Grub, A.; Geissmann, M.; Fuhrer, J. Seasonal variation in radiation and energy balances of permanent pastures at different altitudes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1997, 86, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardo, L.; Geneletti, D.; Pérez-Soba, M.; Van Eupen, M. Estimating the cooling capacity of green infrastructures to support urban planning. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, B.D.; Valsta, L.T. Optimal forest species mixture with carbon storage and albedo effect for climate change mitigation. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 123, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, R.A. Offset of the potential carbon sink from boreal forestation by decreases in surface albedo. Nature 2000, 408, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.; Ramaswamy, V.; Artaxo, P.; Berntsen, T.; Betts, R.; Fahey, D.W.; Haywood, J.; Lean, J.; Lowe, D.C.; Myhre, G.; et al. Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing. In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ar4-wg1-chapter2-1.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Houghton, J.T.; Meira Filho, L.G.; Callander, B.A.; Harris, N.; Kattenberg, A.; Maskell, K. Climate Change 1995. The Science of Climate Change, 1st ed.; Lakeman, J.A., Ed.; Geoscience Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_sar_wg_I_full_report.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Fornaciari, M.; Muscas, D.; Rossi, F.; Filipponi, M.; Castellani, B.; Di Giuseppe, A.; Proietti, C.; Ruga, L.; Orlandi, F. CO2 Emission Compensation by Tree Species in Some Urban Green Areas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, F.; Ranfa, A.; Proietti, C.; Ruga, L.; Ventura, F.; Fornaciari, M. Dynamic estimates of tree carbon storage and shade in Mediterranean urban areas. Int. For. Rev. 2022, 24, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, F.; Fornaciari, M.; Ranfa, A.; Proietti, C.; Ruga, L.; Meloni, G.; Burnelli, M.; Ventura, F. LIFE-CLIVUT, ecosystem benefits of urban green areas: A pilot case study in Perugia (Italy). iFor.-Biogeosci. For. 2022, 15, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestrella, A.; Savé, R.; Biel, C. An Experimental Study in Simulated Greenroof in Mediterranean Climate. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 7, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesús, J.; Kaya, Y.; Bort, J.; Nachit, M.M.; Araus, J.L.; Amor, S.; Ferrazzano, G.; Maalouf, F.; Maccaferri, M.; Martos, V.; et al. Using vegetation indices derived from conventional digital cameras as selection criteria for wheat breeding in water-limited environments. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2007, 150, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeñas, V.; Cuxart, J.; Picos, R.; Medrano, H.; Simó, G.; López-Grifol, A.; Gulías, J. Thermal regulation capacity of a green roof system in the mediterranean region: The effects of vegetation and irrigation level. Energy Build. 2018, 164, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Pickles, B.J.; Shao, L. In-situ spectroscopy and shortwave radiometry reveals spatial and temporal variation in the crown-level radiative performance of urban trees. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 253, 112231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, L.; Eckhardt, K.; Frede, H. Plant parameter values for models in temperate climates. Ecol. Model. 2003, 169, 237–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo Amores, T.R.; Sanchez Ramos, J.; Guerrero Delgado, M.C.; Castro Medina, D.; Cerezo-Narvaez, A.; Alvarez Domínguez, S. Effect of green infrastructures supported by adaptative solar shading systems on livability in open spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatani, L.; Hosseini, S.M.; Sarjaz, M.R.; Alavi, S.J. Tree species effects on albedo, soil carbon and nitrogen stocks in a temperate forest in Iran. Austrian J. For. Sci. 2019, 136, 283. Available online: https://www.forestscience.at/artikel/2019/3/tree-species-effects-on-albedo--soil-carbon-and-nitrogen-stocks-.html (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Otto, J.; Berveiller, D.; Bréon, F.-M.; Delpierre, N.; Geppert, G.; Granier, A.; Jans, W.; Knohl, A.; Kuusk, A.; Longdoz, B.; et al. Forest summer albedo is sensitive to species and thinning: How should we account for this in Earth system models? Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2411–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, W.; Wellpott, A.; Falk, W.; Wehberg, J.; Böhner, J. Klimawandel und der Wasserhaushalt unserer Wälder. AFZ-DerWald 2022, 15, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wicklein, H.F.; Ollinger, S.V.; Martin, M.E.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Lepine, L.C.; Day, M.C.; Bartlett, M.K.; Richardson, A.D.; Norby, R.J. Variation in foliar nitrogen and albedo in response to nitrogen fertilization and elevated CO2. Oecologia 2012, 169, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotelli, D.; Montagnani, L.; Andreotti, C.; Tagliavini, M. Evapotranspiration and crop coefficient patterns of an apple orchard in a sub-humid environment. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 226, 105756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M.; Allen, R.G.; Zarco-tejada, P.J.; Kilic, A.; Santos, C.; Lorite, I.J. Impact of the spatial resolution on the energy balance components on an open-canopy olive orchard. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 74, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.; Matias, M.; Girotti, C.; Vasconcelos, J.; Lopes, A. Heat stress mitigation by exploring UTCI hotspots and enhancing thermal comfort through street trees. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 153, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Du, Z.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Gu, F.; Hao, W.; Yang, Z.; Liu, D. Energy partitioning and evapotranspiration in a black locust plantation on the Yellow River Delta, China. J. For. Res. 2022, 33, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, A.; Frangi, P.; Comin, S.; Vigevani, I.; Rettori, A.A.; Brunetti, C.; Baesso Moura, B.; Ferrini, F. Effects of pavements on established urban trees: Growth, physiology, ecosystem services and disservices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 226, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcgregor, S.; Cromsigt, J.P.G.M.; Beest, M.; Chen, J.; Roy, D.P.; Hawkins, H.; Kerley, G.I.H. Grassland albedo as a nature-based climate prospect: The role of growth form and grazing. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Menon, S.; Rosenfeld, A. Global Cooling: Increasing World-Wide Urban Albedos to Offset CO2. Clim. Change 2009, 94, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Cotana, F.; Filipponi, M.; Nicolini, A.; Menon, S.; Rosenfeld, A. Cool roofs as a strategy to tackle global warming: Economical and technical opportunities. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2013, 7, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. Boundary Layer Climates, 2nd ed.; Methuen Co.: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1987; p. 435. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, B.; Ghosh, A. Urban ecosystem services and climate change: A dynamic interplay. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1281430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. The urban energy balance. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 1988, 12, 471–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finne, E.A.; Bjerke, J.W.; Erlandsson, R.; Tømmervik, H.; Stordal, F. Variation in albedo and other vegetation characteristics in non-forested northern ecosystems: The role of lichens and mosses. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 074038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrer, D.; Pique, G.; Ferlicoq, M.; Ceamanos, X.; Ceschia, E. What is the potential of cropland albedo management in the fight against global warming? A case study based on the use of cover crops. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 044030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, L.W. Radiation Budget of the Forest—A Review; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1973; Available online: https://andrewsforest.oregonstate.edu/publications/1829 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Bright, R.M.; Zhao, K.; Jackson, R.B.; Cherubini, F. Quantifying surface albedo and other direct biogeophysical climate forcings of forestry activities. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 3246–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piselli, C.; Pisello, A.L.; Sa, M.; de Gracia, A.; Cotana, F.; Cabeza, L.F. Cool Roof Impact on Building Energy Need: The Role Climate Conditions. Energies 2019, 12, 3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithers, R.J.; Doick, K.J.; Burton, A.; Sibille, R.; Steinbach, D.; Harris, R.; Groves, L.; Blicharska, M. Comparing the relative abilities of tree species to cool the urban environment. Urban Ecosyst. 2018, 21, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, D.A.; Burakowski, E.A.; Murphy, M.B.; Borsuk, M.E.; Niemiec, R.M.; Howarth, R.B. Trade-offs between three forest ecosystem services across the state of New Hampshire, USA: Timber, carbon, and albedo. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandara, R.; Rupasinghe, H.; Halwatura, R.; Jayasinghe, G. Influence of Street Tree Canopy on the Microclimate of Urban Eco-Space. In Proceedings of the 25th International Forestry and Environment Symposium 2020 of the Department of Forestry and Environmental Science, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Nugegoda, Sri Lanka, 22–23 January 2021; p. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Speak, A.; Montagnani, L.; Wellstein, C.; Zerbe, S. The influence of tree traits on urban ground surface shade cooling. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 197, 103748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, N.; Williams, C.A.; Denney, V.C.; Ellis, P.W.; Shrestha, S.; Hart, D.E.T.; Wolff, N.H.; Yeo, S.; Crowther, T.W.; Werden, L.K.; et al. Accounting for albedo change to identify climate-positive tree cover restoration. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, A.; Mona, M. Climate Change Adaptation: Prioritising Districts for Urban Green Coverage to Mitigate High Temperatures and UHIE in Developing Countries. In Renewable Energy and Sustainable Buildings: Selected Papers from the World Renewable Energy Congress WREC 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, L.S.; Levinson, R. Analysis of the effect of vegetation on albedo in residential areas: Case studies in suburban Sacramento and Los Angeles, CA. GISci. Remote Sens. 2013, 50, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, P.M.; Carinanos, P.; Casares-Porcel, M.; Semenzato, P.; Calaza, P.; Andreucci, M.B.; Branquinho, C.; Mexia, T.; Anjos, A.; Goncalves, P.; et al. Breathing in the Mediterranean Parks. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317011684_BREATHING_IN_THE_MEDITERRANEAN_PARKS (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Wu, Y.; Mashhoodi, B. Urban Climate Effective street tree and grass designs to cool European neighbourhoods. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species Name | Albedo (α) | Mean Value | Approximated Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acer campestre | 0.21 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Acer negundo 1 | 0.22 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Acer opalus 1 | 0.22 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Acer platanoides | 0.22 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Acer pseudoplatanus 1 | 0.22 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Acer rubrum | 0.15 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Acer saccharinum 1 | 0.22 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Acer saccharum 1 | 0.22 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Acer spp. 1 | 0.22 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Aesculus hippocastanum | 0.18 | x | Drone survey | |

| Aesculus x carnea | 0.18 | x | Drone survey | |

| Albizia julibrissin | 0.60 | x | Palomo Amores et al., 2023 [41] | |

| Carpinus betulus | 0.19 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Celtis australis | 0.18 | x | Palomo Amores et al., 2023 [41] | |

| Cercis siliquastrum | 0.60 | x | Palomo Amores et al., 2023 [41] | |

| Cupressus sempervirens | 0.16 | x | Vatani et al., 2019 [42] | |

| Cupressus sempervirens pyramidalis 2 | 0.16 | x | Vatani et al., 2019 [42] | |

| Diospyros kaki 3 | 0.23 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Fagus sylvatica | 0.17 | x | Otto et al., 2014 [43] | |

| Fraxinus angustifolia | 0.18 | x | Weis et al., 2022 [44] | |

| Fraxinus excelsior | 0.18 | x | Weis et al., 2022 [44] | |

| Fraxinus intermedia | 0.18 | x | Weis et al., 2022 [44] | |

| Fraxinus ornus | 0.18 | x | Weis et al., 2022 [44] | |

| Fraxinus spp. | 0.18 | x | Weis et al., 2022 [44] | |

| Liquidambar styraciflua | 0.30 | x | Wicklein et al. 2012 [45] | |

| Malus communis 4 | 0.15 | x | Zanotelli et al., 2019 [46] | |

| Malus domestica | 0.15 | x | Zanotelli et al., 2019 [46] | |

| Malus sylvestris 4 | 0.15 | x | Zanotelli et al., 2019 [46] | |

| Olea europaea | 0.19 | x | Ramírez-Cuesta et al., 2019 [47] | |

| Picea abies | 0.14 | x | Weis et al. 2022 [44] | |

| Pinus halepensis | 0.14 | x | Drone survey | |

| Pinus pinaster 5 | 0.17 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Pinus pinea | 0.17 | x | Drone survey | |

| Pinus sylvestris | 0.16 | x | Otto et al., 2014 [43] | |

| Platanus acerifolia | 0.18 | x | Palomo Amores et al., 2023 [41] | |

| Populus alba | 0.31 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Populus nigra | 0.31 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Populus nigra ‘Italica’ | 0.31 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Prunus amygdalus | 0.40 | x | Silva et al., 2025 [48] | |

| Prunus persica | 0.28 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Pyrus calleryana | 0.40 | x | Silva et al., 2025 [48] | |

| Pyrus communis 6 | 0.40 | x | Silva et al., 2025 [48] | |

| Pyrus pyraster 6 | 0.40 | x | Silva et al., 2025 [48] | |

| Quercus crenata | 0.34 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Quercus ilex | 0.15 | x | Drone survey | |

| Quercus petraea | 0.34 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Quercus pubescens | 0.34 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Quercus robur | 0.34 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Quercus spp. | 0.34 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | 0.12 | x | Gao et al., 2022 [49] | |

| Tilia cordata 7 | 0.20 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Tilia intermedia 7 | 0.20 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Tilia platyphyllos | 0.20 | x | Deng et al., 2021 [39] | |

| Ulmus carpinifolia | 0.28 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Ulmus laevis | 0.28 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Ulmus minor | 0.28 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] | |

| Ulmus pumila | 0.28 | x | Breuer et al., 2003 [40] |

| City | Park Name | Total Park Area (m2) | Streets and Paths (m2) | Buildings (m2) | Tree Canopy (m2) | Lawn (m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG | Chico Mendez Park | 160,235.88 | 38,359.61 | 162.14 | 39,398.12 | 82,316.01 |

| (24%) | (0%) | (25%) | (51%) | |||

| PG | Verbanella Park | 30,868.47 | 3276.18 | 465.16 | 24,534.95 | 2592.19 |

| (11%) | (2%) | (79%) | (8%) | |||

| BO | Villa Ghigi Park | 25,474.33 | 1694.31 | 934.77 | 15,596.02 | 7249.22 |

| (7%) | (4%) | (61%) | (28%) | |||

| BO | 11 September Park | 15,965.77 | 4561.64 | 1555.41 | 7044.42 | 2804.29 |

| (29%) | (10%) | (44%) | (18%) |

| Tree Species | Number of Trees | Crown Area (m2) | Compensated CO2eq (Ton) Trees vs. Asphalt Scenario | Compensated CO2eq (Ton) Trees vs. Lawn Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acer campestre | 72 | 2153.17 | 0.33 | −0.04 |

| Acer opalus | 2 | 22.78 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Acer platanoides | 4 | 80.90 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Acer pseudoplatanus | 7 | 208.13 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Acer rubrum | 1 | 9.62 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Aesculus hippocastanum | 189 | 4919.51 | 0.55 | −0.28 |

| Aesculus × carnea | 10 | 444.93 | 0.05 | −0.03 |

| Carpinus betulus | 16 | 506.58 | 0.06 | −0.02 |

| Cupressus sempervirens | 170 | 538.19 | 0.04 | −0.05 |

| Malus communis | 1 | 7.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Malus domestica | 1 | 12.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Olea europea | 54 | 616.14 | 0.08 | −0.02 |

| Pinus halepensis | 5 | 392.70 | 0.02 | −0.05 |

| Pinus pinea | 2 | 226.19 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| Populus alba | 19 | 1545.66 | 0.48 | 0.22 |

| Populus nigra | 124 | 1573.35 | 0.49 | 0.23 |

| Populus nigra ‘Italica’ | 18 | 72.26 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Prunus amygdalus | 7 | 119.77 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Prunus persica | 6 | 18.85 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Quercus crenata | 6 | 91.50 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Quercus ilex | 141 | 9855.87 | 0.63 | −1.03 |

| Quercus petraea | 3 | 356.57 | 0.13 | 0.07 |

| Quercus pubescens | 18 | 995.88 | 0.37 | 0.20 |

| Quercus robur | 6 | 204.99 | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | 39 | 691.54 | 0.01 | −0.11 |

| Tilia platyphyllos | 5 | 249.76 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

| Ulmus carpinifolia | 14 | 455.53 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

| Ulmus laevis | 15 | 743.77 | 0.20 | 0.07 |

| Ulmus pumila | 3 | 368.35 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| Total | 958 | 27,482.13 | 3.95 | −0.69 |

| Tree Species | Number of Trees | Crown Area (m2) | Compensated CO2eq (Ton) Trees vs. Asphalt Scenario | Compensated CO2eq (Ton) Trees vs. Lawn Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acer opalus | 5 | 237.19 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Acer pseudoplatanus | 1 | 19.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Acer saccharinum | 5 | 106.81 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Acer saccharum | 5 | 296.10 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| Aesculus hippocastanum | 6 | 230.91 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

| Cercis siliquastrum | 41 | 1425.50 | 1.12 | 0.87 |

| Cupressus sempervirens | 42 | 296.88 | 0.02 | −0.03 |

| Cupressus sempervirens pyramidalis | 21 | 103.08 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| Fraxinus ornus | 9 | 450.82 | 0.05 | −0.03 |

| Fraxinus sp. | 3 | 76.18 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Olea europaea | 66 | 2568.25 | 0.33 | −0.11 |

| Pinus pinaster | 24 | 4265.50 | 0.41 | −0.32 |

| Pinus pinea | 38 | 4228.58 | 0.20 | −0.52 |

| Quercus ilex | 47 | 2849.42 | 0.18 | −0.31 |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | 6 | 117.81 | 0.00 | −0.02 |

| Ulmus carpinifolia | 42 | 1935.61 | 0.51 | 0.18 |

| Ulmus pumila | 2 | 66.76 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Total | 363 | 19,275.05 | 3.01 | −0.30 |

| Tree Species | Number of Trees | Crown Area (m2) | Compensated CO2eq (Ton) Trees vs. Asphalt Scenario | Compensated CO2eq (Ton) Trees vs. Lawn Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acer campestre | 3 | 75.40 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| Acer negundo | 4 | 453.96 | 0.08 | −0.02 |

| Acer platanoides | 2 | 166.50 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

| Aesculus hippocastanum | 4 | 201.06 | 0.02 | −0.02 |

| Albizia julibrissin | 1 | 50.27 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Celtis australis | 17 | 1624.20 | 0.18 | −0.18 |

| Cercis siliquastrum | 3 | 37.70 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Fraxinus angustifolia | 1 | 12.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fraxinus excelsior | 4 | 87.96 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| Fraxinus intermedia | 3 | 37.70 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fraxinus ornus | 1 | 12.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Liquidambar styraciflua | 2 | 25.13 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Malus sylvestris | 3 | 37.70 | 0.00 | −0.01 |

| Pinus sylvestris | 3 | 195.56 | 0.02 | −0.03 |

| Platanus acerifolia | 7 | 559.20 | 0.06 | −0.06 |

| Populus nigra | 5 | 457.10 | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| Populus nigra ‘Italica’ | 1 | 7.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pyrus calleryana | 1 | 12.57 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Quercus ilex | 1 | 12.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Quercus robur | 2 | 226.98 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | 2 | 183.00 | 0.00 | −0.04 |

| Tilia cordata | 3 | 113.10 | 0.02 | −0.01 |

| Tilia intermedia | 4 | 245.83 | 0.03 | −0.02 |

| Tilia platyphyllos | 2 | 25.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ulmus carpinifolia | 2 | 190.07 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Total | 81 | 5050.90 | 0.82 | −0.28 |

| Tree Species | Number of Trees | Crown Area (m2) | Compensated CO2eq (Ton) Trees vs. Asphalt Scenario | Compensated CO2eq (Ton) Trees vs. Lawn Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acer campestre | 7 | 227.77 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Acer opalus | 15 | 714.71 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| Acer sp. | 1 | 78.54 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Carpinus betulus | 2 | 355.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Celtis australis | 21 | 2203.04 | 0.24 | 0.03 |

| Cercis siliquastrum | 1 | 19.63 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Cupressus sempervirens | 1 | 50.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Diospyros kaki | 20 | 565.49 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Fagus sylvatica | 2 | 57.33 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Fraxinus angustifolia | 1 | 153.94 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Picea abies | 1 | 50.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pinus sylvestris | 1 | 38.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pyrus communis | 1 | 113.10 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Pyrus pyraster | 3 | 139.80 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Quercus pubescens | 13 | 2787.38 | 1.01 | 0.74 |

| Quercus robur | 2 | 267.04 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Quercus spp. | 1 | 78.54 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Tilia cordata | 13 | 1361.88 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| Tilia platyphyllos | 5 | 547.42 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| Ulmus carpinifolia | 1 | 28.27 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Ulmus laevis | 1 | 28.27 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Ulmus minor | 1 | 78.54 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Total | 114 | 9944.71 | 2.14 | 1.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muscas, D.; Bonciarelli, L.; Filipponi, M.; Orlandi, F.; Fornaciari, M. Urban Tree CO2 Compensation by Albedo. Land 2025, 14, 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081633

Muscas D, Bonciarelli L, Filipponi M, Orlandi F, Fornaciari M. Urban Tree CO2 Compensation by Albedo. Land. 2025; 14(8):1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081633

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuscas, Desirée, Livia Bonciarelli, Mirko Filipponi, Fabio Orlandi, and Marco Fornaciari. 2025. "Urban Tree CO2 Compensation by Albedo" Land 14, no. 8: 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081633

APA StyleMuscas, D., Bonciarelli, L., Filipponi, M., Orlandi, F., & Fornaciari, M. (2025). Urban Tree CO2 Compensation by Albedo. Land, 14(8), 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081633