Towards a Sustainable Process of Conservation/Reuse of Built Cultural Heritage: A “Coevolutionary” Approach to Circular Economy in the Case of the Decommissioned Industrial Agricultural Consortium in the Corbetta, Metropolitan Area of Milan, Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conservation, Reuse and Circular Economy: Contemporary Questions and a Responsive Italian Method

1.2. Intellectual Background of the Original Research and the Selection of the Case Study

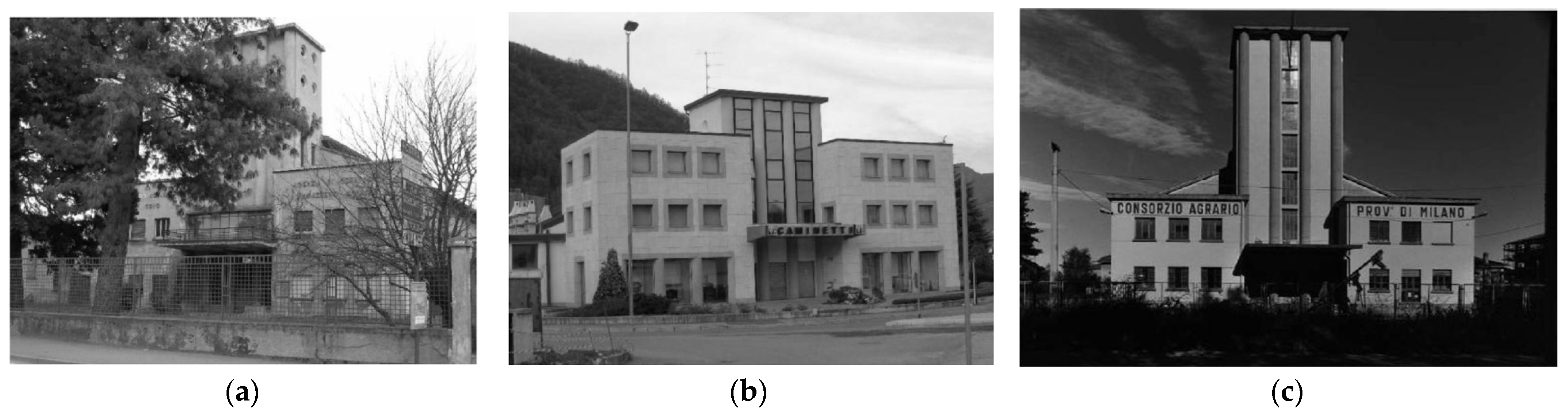

1.3. Grain Silos and the Question of Conservation and Reuse

2. Research Methodology

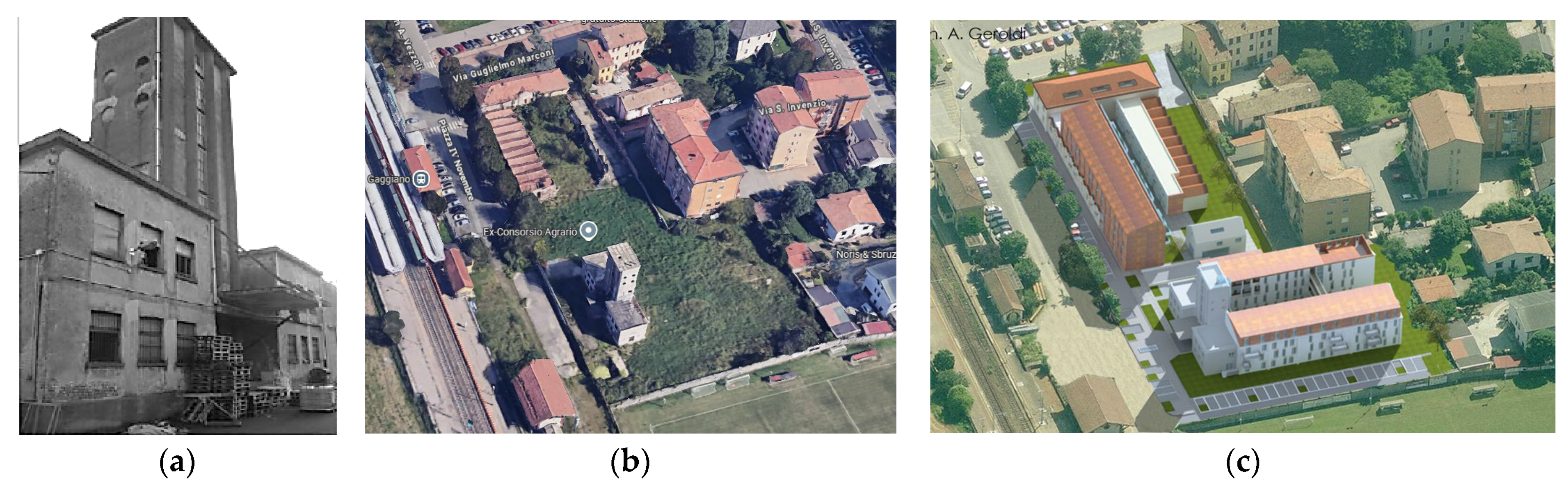

3. Industrial Agricultural Consortium of Corbetta and Its Context; Historical Significance and Current Situation

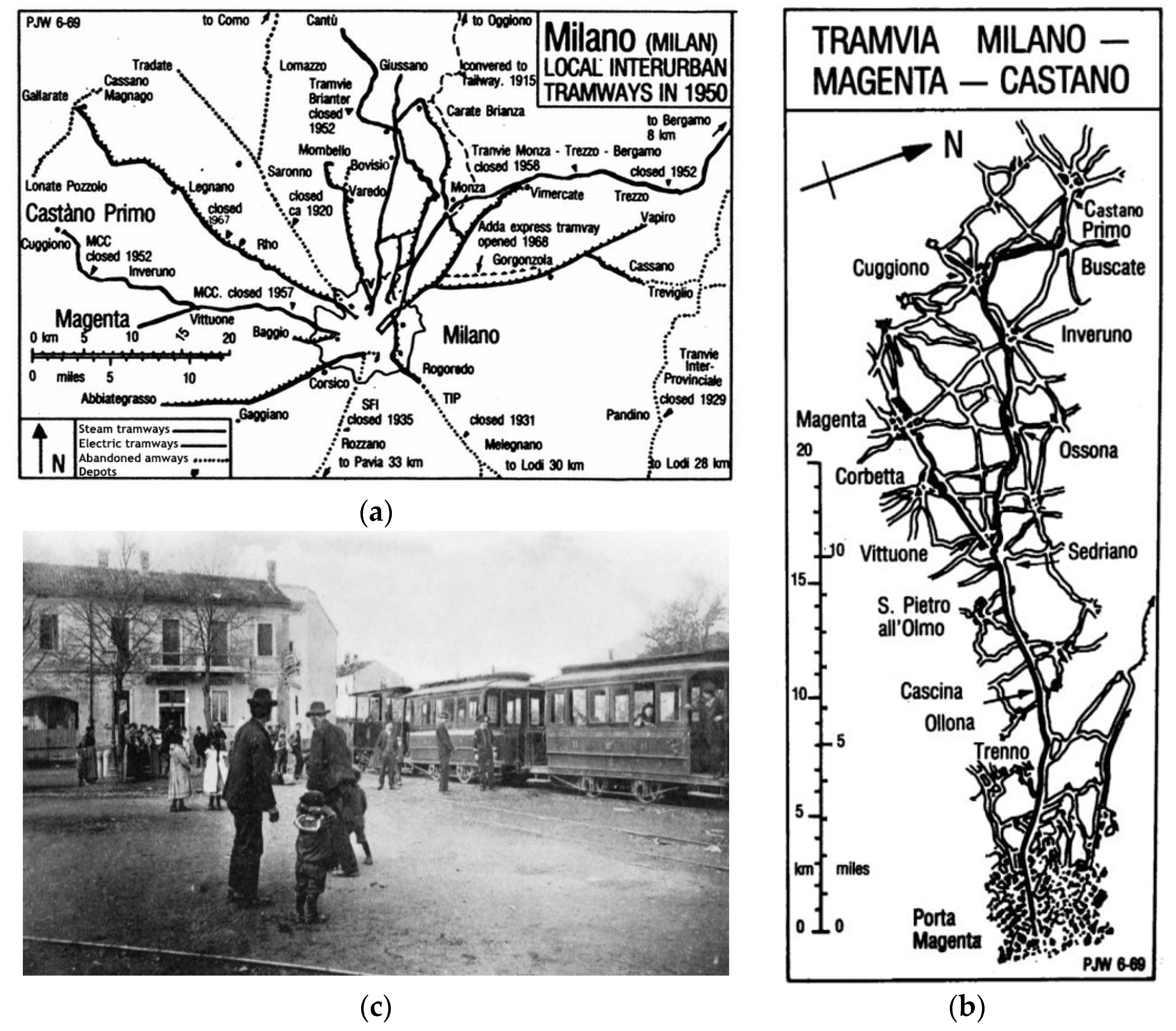

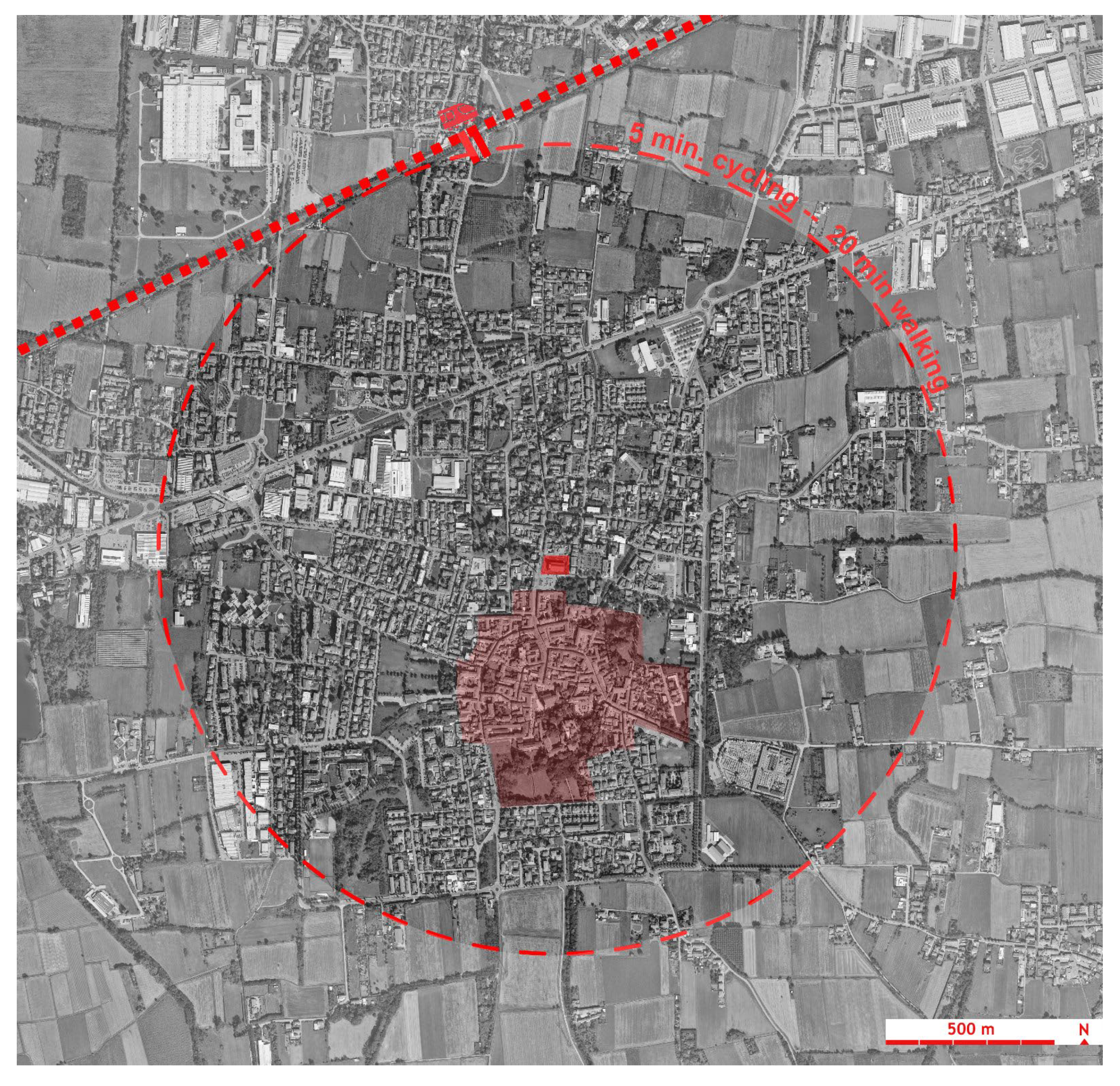

3.1. The City of Corbetta

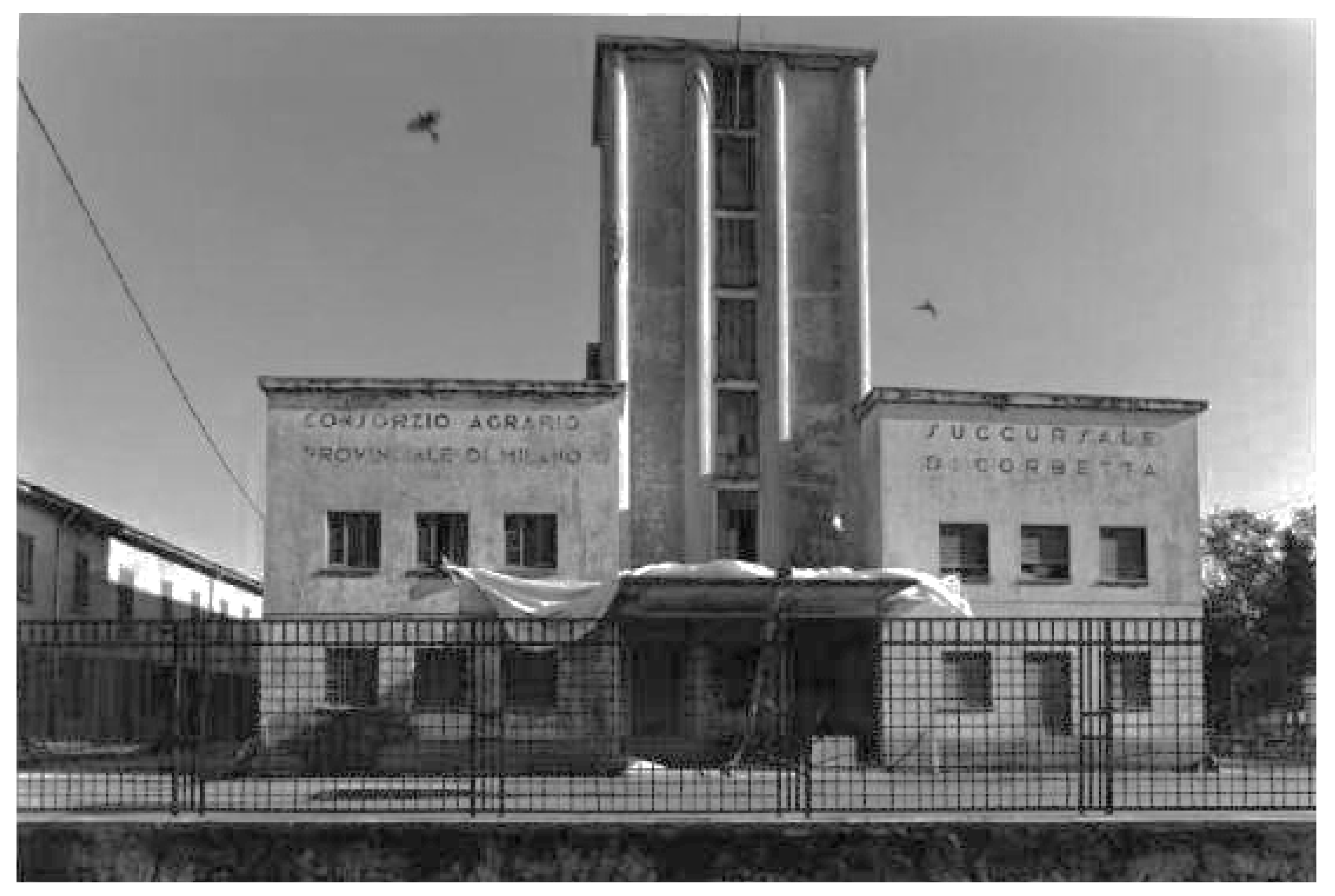

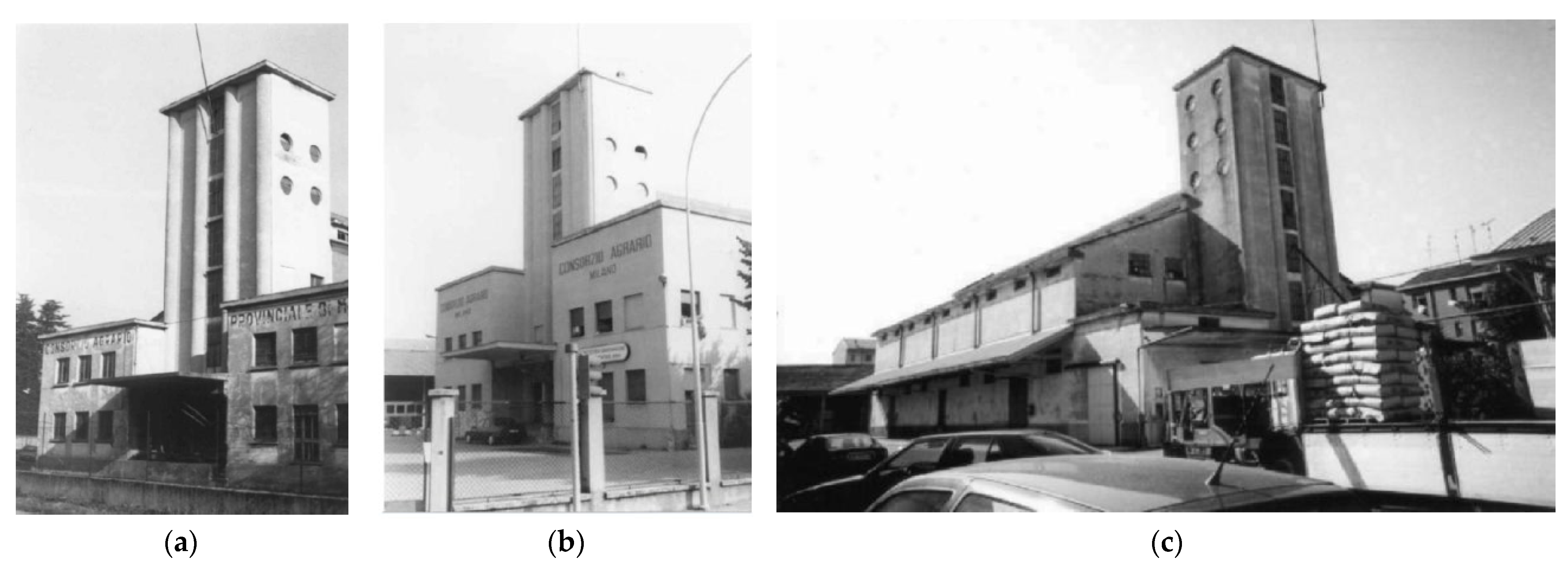

3.2. The Industrial, Agricultural Consortium of Corbetta

4. Discussion

4.1. The Values System of Industrial Agricultural Consortium of Corbetta

4.2. Compatibility of Design Choices and Reuse Options with Values System

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F. Integrating cultural heritage in urban territorial sustainable development. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 19th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium Heritage and Democracy, New Delhi, India, 13–14 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Gravagnuolo, A. Circular economy and cultural heritage/landscape regeneration. Circular business, financing and governance models for a competitive Europe. Bull. Calza Bini Cent. 2017, 17, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, S. A coevolutionary approach to the reuse of built cultural heritage. In Proceedings of the 35 Convegno internazionale Scienza e Beni Culturali, Collana Scienza e Beni Culturali, Bressanone, Italy, 1–5 July 2019; Edizioni Arcadia Ricerche: Bressanone, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. The management process for built cultural heritage: Preventive systems and decision making. In Innovative Built Heritage Models, 1st ed.; Van Balen, K., Vendesande, A., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2018; pp. 13–20. ISBN 978-1-138-49861-7. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. Planned conservation and local development processes: The key role of intellectual capital. In Reflections on Preventive Conservation, Maintenance and Monitoring; Van Balen, K., Vandesande, A., Eds.; Acco: Leuven, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. Conservation of built cultural heritage, laws enabling preventive approach: The case of Italy. In Cultural Heritage and Legal Aspects in EUROPE; Gustin, M., Nypan, T., Eds.; Institute for Mediterranean Heritage and Institute for Corporation and Public Law Science and Research Centre Koper, University of Primorska: Koper, Slovenia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rajabi, M. Climate Change, Resilience and Cultural Heritage, In-Between International Debates and Practical Encounters; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-61241-1. [Google Scholar]

- Giraud-Labalte, C.; Pugh, K.; Quaedvlieg-Mihailović, S.; Sanetra-Szeliga, J.; Smith, B.; Thys, C.; Vandesande, A. (Eds.) Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe: Full Report; International Culture Centre: Krakow, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Plevoets, B.; Van Cleempoel, K. Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage: Concepts and Cases of an Emerging Discipline; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douet, J. Industrial Heritage re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J. Building Adaptation; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifko, S. Protection of Authenticity and Integrity of Industrial Heritage Sites in Reuse Projects. In Protection and Reuse of Industrial Heritage: Dilemmas, Problems, Examples, Monographic Publications of ICOMOS Slovenia; Ifko, S., Stokin, M., Eds.; ICOMOS: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, M. (Ed.) Industrial Buildings: Conservation and Regeneration, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banham, R. A Concrete Atlantis. In US Industrial Building and European Modern Architecture 1900–1925; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke, F. Measure of Emptiness: Grain Elevators in the American Landscape; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mahar-Keplinter, L. Grain Elevators; Princeton Architectural Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Salamanca Cascos, D. Los Gigantes del Siglo XX. Reinterpretacion en el Silo XXI. 2009. Available online: https://www.ugr.es/~ambientalia/congresos/ArticulosIVCongreso/Articulos_pdf/Salamanca_2009_Ambientalia.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Caballos, M. Red Nacional de Silos y Generos. Territorio Arquitectura y Oportunidad. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, S. Grain Silos from the Thirties in Italy, Analysis, Conservation and Adaptive Reuse; Pisa University Press: Pisa, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mimmo, M.; Casiraghi, C.; Massari, A.; Cadamuro, F.; Magugliani, B. (Eds.) Guida ai Monumenti di Corbetta; Comune di Corbetta: Corbetta, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Maddalena, A. Dalla Città al Borgo. Avvio di una Metamorfosi Economica e Sociale Nella Lombardia Spagnola; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Comincini, M. (Ed.) Corbetta, Storia Della Comunità dal 1861 al 1945; Grafica Sant’Angelo: Sant’Angelo Lodigiano, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquero Pineiro, M. I silos granari in Italia negli anni Trenta: Fra architettura e autarchia economica. Patrim. Ind. 2011, 7, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquero Piñeiro, M. Rastrellare il grano. Gli ammassi obbligatori in Italia dal Fascismo al Dopoguerra. Soc. Stor. 2015, 148, 257–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federazione Italiana dei Consorzi Agrari. Federazione Italiana dei Consorzi Agrari 1892–1952; Ramo Editorial Degli Agricoltori: Rome, Italy, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Torelli, G.A. (Ed.) Consorzio Agrario di Milano e Lodi 1902–2002: Diario di Cento anni di Lavoro al Servizio Degli Agricoltori; Stampa Furlan Grafica: Milan, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mango, A. La Conservazione dei Cereali; Federazione Italiana Consorzi Agrari: Piacenza, Italy, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Garre, G. Sul problema dei silos granari in Italia. Ind. Ital. Cem. 1934, VI, 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, S. Italian grain silos in the 1930s, Which reuse? In Proceedings of the REUSO 2015—III Congreso Internacional sobre Documentación, Conservación y Reutilización del Patrimonio Arquitectónico y Paisajístico, Editorial Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 22–24 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, F.; De Falco, A.; Landi, S.; Bevilacqua, M.G.; Santini, L.; Pecori, S. Reusing grain silos from the 1930s in Italy, A multi-criteria decision analysis for the case of Arezzo. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 29, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapperon, R. Silos e Magazzini per Ammassi Granari. Progettazione, Costruzione, Gestione; Istituto delle Edizioni Accademiche: Udine, Italy, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Docci, M. Oltre l’abbandono: Il patrimonio industriale fra conoscenza e Progetto. In Disegno e Restauro: Conoscenza Analisi Intervento per il Patrimonio Architettonico e Artistico; Strollo, R.M., Ed.; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2010; pp. 165–180. ISBN 978-88-548-3609-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mainini, G.; Rosa, G.; Sajeva, A. Archeologia Industriale; La nuova Italia: Florence, Italy, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. (Ed.) Restauro dell’Architettura. Per un Progetto di Qualità; Edizioni Quasar di S. Tognon srl: Napoli, Italy, 2023; ISBN 979-88-5491-462-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cascos, S.; Caballos, M. Red Nacional de Silos. Integración en la Realidad Urbana Andaluza y su Reutilización para Nuevas Tipologías; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yeksareva, N.; Yeksarev, V.; Yeksarev, A. Potential for architectural adaptation port silos. VITRUVIO Int. J. Archit. Technol. Sustain. 2022, 7, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Fraddanni, S. (Ed.) Verso una Nuova Sky-Line Portuale. La Rinascita del Silo Granario; 5th of the Quaderni di Memoria Series; Fondazione Livorno: Livorno, Italy, 2023; ISBN 978-88-8341-918-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tinè, V. Architettura Preventiva? Nuovi Strumenti Normativi per un Equilibrio fra Tutela e Progettualità. Available online: https://sira-restauroarchitettonico.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ARCHIPREVdef-1.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Zanetti, T. La Manufacture d’Armes de Saint-Ètienne: Un patrimoine militaire saisi par l’économie créative. In Situ Rev. Patrim. 2011, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, S. L’idea di coevoluzione messa in pratica. Intrecci 2023, 3, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rajabi, M.; Della Torre, S.; Heidari Afshari, A. Towards a Sustainable Process of Conservation/Reuse of Built Cultural Heritage: A “Coevolutionary” Approach to Circular Economy in the Case of the Decommissioned Industrial Agricultural Consortium in the Corbetta, Metropolitan Area of Milan, Italy. Land 2025, 14, 1595. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081595

Rajabi M, Della Torre S, Heidari Afshari A. Towards a Sustainable Process of Conservation/Reuse of Built Cultural Heritage: A “Coevolutionary” Approach to Circular Economy in the Case of the Decommissioned Industrial Agricultural Consortium in the Corbetta, Metropolitan Area of Milan, Italy. Land. 2025; 14(8):1595. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081595

Chicago/Turabian StyleRajabi, Mehrnaz, Stefano Della Torre, and Arian Heidari Afshari. 2025. "Towards a Sustainable Process of Conservation/Reuse of Built Cultural Heritage: A “Coevolutionary” Approach to Circular Economy in the Case of the Decommissioned Industrial Agricultural Consortium in the Corbetta, Metropolitan Area of Milan, Italy" Land 14, no. 8: 1595. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081595

APA StyleRajabi, M., Della Torre, S., & Heidari Afshari, A. (2025). Towards a Sustainable Process of Conservation/Reuse of Built Cultural Heritage: A “Coevolutionary” Approach to Circular Economy in the Case of the Decommissioned Industrial Agricultural Consortium in the Corbetta, Metropolitan Area of Milan, Italy. Land, 14(8), 1595. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081595