1. Introduction

Tourism is a critical driver of regional development, particularly in areas abundant with cultural and environmental resources [

1]. However, many peripheral and disaster-affected regions face significant challenges in leveraging these assets for sustainable and inclusive economic growth [

2,

3]. Northern and Central Euboea, Greece’s second-largest island, severely impacted by the 2021 wildfires [

4], exemplifies such a region, grappling with compounded issues including economic decline, depopulation, and environmental degradation [

5,

6]. While mass tourism traditionally focuses on coastal and urban centers [

7,

8], alternative tourism that emphasizes cultural heritage, local identity, and nature-based experiences offers promising pathways to redress territorial inequalities and foster resilient development [

9,

10,

11].

Nonetheless, obstacles such as fragmented spatial planning, limited digital infrastructure, and insufficient stakeholder engagement have hindered the activation of this potential in regions like Evia [

12,

13]. Addressing these gaps, this study proposes an integrated sustainable tourism development model that combines heritage management, innovative ICT tools, agritourism collaboration, and participatory governance, developed within the framework of the AEI project (Sustainable Development of Less Developed Regions and Isolated Areas by Creating New Touristic Resources and Products through Analysis, Documentation and Modelling of Cultural Assets using Innovative ICT Applications.), co-financed by the European Union and Greek national funds [

14].

The “AEI” program focused on sustainable development in Greece’s less developed regions by leveraging cultural and environmental assets through innovative ICT tools. By redirecting tourist flows from major hubs to new attractions such as archaeological parks and cultural routes, it aims to boost local economies and promote social cohesion. Pilot projects in areas like Aetolia-Acarnania, East Mani, Euboea, Chios, and the Dodecanese islands exemplify this approach, structured around asset management, digital innovation, new tourism products, and circular economy principles [

14].

The research aims to assess how the preservation and promotion of cultural and environmental assets—enhanced by digital platforms and inclusive planning—can generate novel tourism products and invigorate the local economy in underdeveloped contexts such as Northern and Central Evia. The Evia case study is described in this work as it regards an underdeveloped/remote area that has been subjected to catastrophic wildfires that further exaggerated the specific rural characteristics and the need to provide alternative and efficient remedial measures. The methodology presented below is applicable to similar case studies of remote areas that experienced physical or anthropogenic disasters, proving that the revealing of an area’s environmental and cultural heritage could be at the core of an overall sustainable development plan. By employing a holistic framework integrating spatial planning, ICT innovation, agrifood-enriched tourism, and multi-stakeholder cooperation, the study transforms environmental and cultural vulnerabilities into opportunities for resilient, equitable growth [

15,

16,

17].

3. Methodology

The methodological framework adopted in this study was developed in the context of the “AEI” research program [

14], which aimed at promoting sustainable development in underdeveloped and post-disaster regions of Greece through the valorization of cultural and environmental assets. The approach combined spatial analysis, participatory planning, ICT integration, and socioeconomic modeling to design and assess a strategic intervention plan for these types of regions, including the region of Northern and Central Euboea.

The research area encompasses a mountainous and environmentally sensitive part of the island of Euboea, which suffered extensive damage during the wildfires of 2021. The region is characterized by dispersed settlements, rich biodiversity, and important but underutilized cultural heritage. The area was selected due to its strategic need for development and its potential to support alternative forms of tourism.

The data collection process included an extensive bibliographic review of the region’s historical, cultural, environmental, and infrastructural characteristics. In parallel, spatial data were gathered through field surveys and interviews with local stakeholders, such as municipal authorities, the Ephorate of Antiquities, professional associations, and residents. These consultations took place throughout the design phase and served to capture the perceptions, needs, and priorities of the local community.

The collected data were processed and analyzed through Geographic Information Systems (GISs), which allowed the mapping and integration of multiple layers of information, including points of cultural and environmental interest, trail networks, land use, and accessibility patterns. This spatial analysis supported the development of new thematic cultural routes and the identification of underutilized tourism assets.

In addition, ICT tools were employed to enhance the management and dissemination of the findings. A WebGIS platform was developed to visualize the spatial configuration of the region’s assets and proposed routes, while a digital development platform was designed to consolidate investment proposals and link them with appropriate funding instruments. Furthermore, a tourism portal and interactive maps were created to support local promotion and tourist guidance.

Concerning the implementation of the proposal schemes as well as the overall promotion of the area’s sustainable development, the development platform created includes all the projects that are in synergy with the plans of the AEI, as well as the available financial tools for their realization. Additionally, the organization of public meetings promoted the political census, the cooperation between governmental bodies (the Ministry of Environment and Energy, the Ministry of Rural Development, and Ministry of Tourism), and the information and coordination with local communities.

To evaluate the economic feasibility and expected outcomes of the proposed interventions, an input–output model was employed, incorporating sector-specific multipliers and scenario-based assumptions. The analysis simulated the effect of investment on regional GDP and employment, assuming an extended tourist season and improved infrastructure and services.

Overall, the methodology followed a holistic and participatory approach. It integrated qualitative data from community engagement and expert input with quantitative tools for spatial planning and economic impact assessment. While the framework was developed within the AEI project, its structure and tools are transferable and scalable to other regions facing similar challenges. Nonetheless, it should be noted that this approach remains primarily ex-ante and planning-oriented, as empirical post-implementation data were not yet available at the time of writing.

The methodological framework developed in this study is schematically summarized in

Figure 2. It involves an initial stage of analysis of the remoteness characteristics, upon which the areas of study are selected. Key elements of the research areas selection regard geographical issues, the existing transportation infrastructure, the access level to services (e.g., healthcare, education, water, energy), the type of economic activities, the demographic situation, and the connectivity dynamics in all its aspects (trade interaction, cultural compatibility, religion issues).

Following the appropriate selection of the research areas, the main activities are organized along four main axes:

3.1. Axis I—Analysis, Documentation, Modeling, and Management of Cultural and Environmental Assets

The key objective of the initial axis of activities regards the identification and documentation of the two main types of assets within the study area, i.e., cultural and environmental assets. This is achieved by organizing and implementing a comprehensive bibliographical review and mapping and active engagement of the local authorities, professional associations and the general public through field surveys and local meetings to obtain crucial and complementary information. This information is subsequently analyzed and correlated with the remoteness characteristics of the area to identify critical limitations and areas of opportunity in close cooperation with the end-users. Effectively, this axis provides a “pool” of alternative and complementary resources, upon which the most effective design of the tourism products will be based. It is important to emphasize the strong participatory planning character of this group of activities since the early engagement of the local society and stakeholders not only provides more accurate, fair and representative information but also allows for enhanced adaptability if required during future optimization processes.

3.2. Axis II—Utilization of Innovative ICT Applications

This axis focuses on three key objectives: (a) the integration of digital tools, (b) management of tourism and (c) local sustainable development. The utilization of ICT applications aims to exploit their relative advantages: optimized management and distribution of information, enhanced presentation of data, and efficient support for analysis. The utilization of Geographical Information Systems (GISs) is fundamental and compatible with most platforms used nowadays by local and regional authorities to expedite the implementation and control of relevant policies and legislation. GIS shall be used both for mapping purposes as well as for visualization of relevant assets and supporting information. In addition, specialized digital tools need to be developed, such as digital maps, tourism and development platforms, which will jointly function as the main enablers for the digitalization of the corresponding processes. These digital tools, interconnected with each other both technically (e.g., crosscutting databases) as well as functionally, will ensure that the utilization of the included cultural and environmental assets is performed within a joint, integrated utilization framework managed and prioritized by the tourism and development platforms. Finally, a geospatial analysis will ensure that the specific characteristics of each selected subarea and its cultural and environmental content are transformed into drivers for local and trans-local development.

3.3. Axis III—Design and Creation of New Tourism Products

The key objectives of this axis regard (a) the development of alternative—area tailored—tourism strategies, (b) enhancement of local economies, (c) harmonized exploitation of cultural and environmental assets and (d) activities to mitigate the impact of the remoteness characteristics on the area’s development. In order to achieve this, it is important to focus on the most appropriate target group. The target groups are identified based on the remoteness factors and the analysis and correlation of the cultural and environmental assets of the examined area, and with the aid of ICT applications to allow fusion of relevant information. Potential target groups span from tourists and seasonal residents (a very common situation in Mediterranean countries, during summer vacations, when people return to their villages), to more specialized groups such as pilgrims, art tourists, food enthusiasts, art enthusiasts and conference/workshop participants. All such groups obviously necessitate different infrastructure (accommodation, food business, and venues) and focus on different types of assets. The selection and organization of the tourism products will be coordinated by regional and local authorities, residents, professional associations and tourist groups. However, such a process requires addressing often contradicting requirements and priorities: the virtue of prior analysis and correlation between the needs of the local communities, the strengths and weaknesses of the available resources and cultural and environmental assets, the availability of ICT applications to support a better understanding of the overall complex situation, and finally, a clear and feasible development plan at local and regional levels. Through such a comprehensive design and creation process, the most appropriate cultural routes and thematic trails can be defined, in conjunction with promotion of agricultural activities (note: support the tourism flux) and improvement and/or construction of the relevant tourism infrastructure (hotels, transport network, business clusters, information channels, etc.).

3.4. Circular Economy and Social Cohesion

The above efforts cannot be beneficial in the long term unless community participation is fostered and unless economic sustainability is ensured. Both key objectives are achieved by active, continuous and fair community participation, through regular and specialized public meetings between all parties involved (residents, authorities, stakeholders etc.). Once community participation is activated and retained, local businesses need to collaborate to develop complementary and wide-ranging capacities through guidelines and recommendations set by their professional associations and relevant authorities. Effectively, the needs of the local society and the capacities of the local business community are aligned. A metric of the success of such a collaboration is, thus, the evaluation of the socio-economic impact of the selected new tourism products. Overall, the sustainable development of the research area is achieved through close cooperation, fusion of innovation, targeted adjustment of capabilities and methodical utilization of an area’s cultural and environmental reserves.

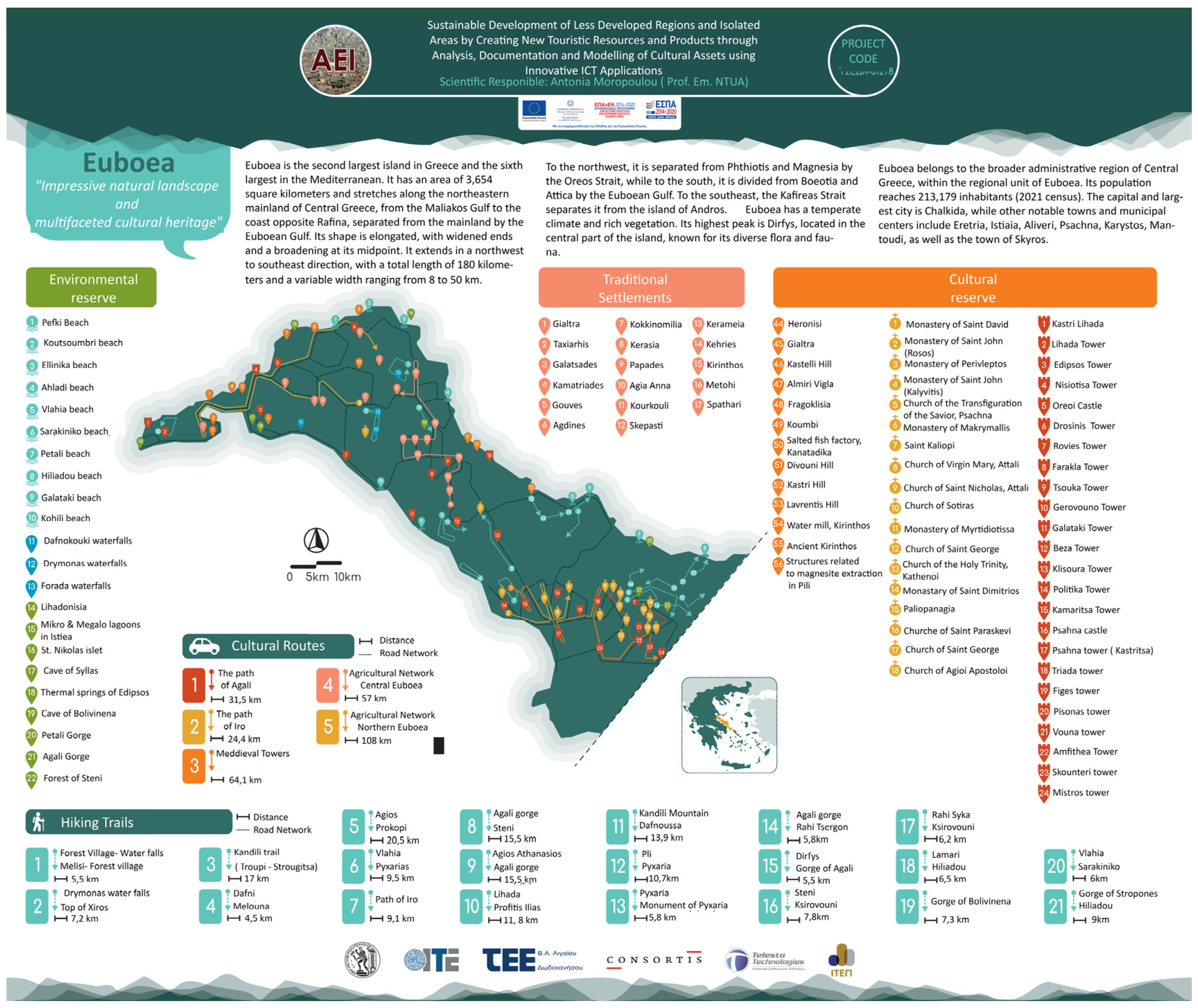

3.5. Research Area Analysis

Central and Northern Euboea, part of Greece’s second-largest island, are characterized by diverse landscapes, including mountainous terrain, fertile valleys, and coastal areas. The region is dominated by the Dirfys and Kandili mountain ranges, which influence its microclimates and ecosystems. These areas are rich in biodiversity, with forests, rivers, and endemic flora and fauna, but they are also vulnerable to environmental threats such as wildfires, soil erosion, and climate change impacts [

41] (

Figure 1). The rugged topography and limited infrastructure in some parts contribute to their relative isolation, particularly in the inland and mountainous zones. In terms of road network and accessibility, the only road connection to the area is via Chalkida, the internal road cannot generate a tourist flow—the only connection is via Edipsos, and there are no roads branching out throughout Evia and connecting the towns and settlements. Access to healthcare, education, and other essential services is also constrained, with residents often needing to travel long distances to reach facilities. Additionally, while Evia is a transit point to the Northern Sporades and Magnesia, the connections with these areas are completely local and do not make Evia a tourist destination on a scale that would contribute to the development of the region.

The population of Central and Northern Euboea is sparse and unevenly distributed, with many small villages experiencing depopulation due to urbanization and limited economic opportunities [

30]. The aging population and youth migration to urban centers, such as Athens and Chalkida, have led to a decline in local labor forces and community vitality. Economically, the region relies heavily on agriculture, livestock farming, and small-scale tourism, with limited diversification. While coastal areas benefit from seasonal tourism, inland and mountainous regions struggle with underdevelopment and limited access to markets and services.

The region boasts a rich cultural heritage, including Byzantine churches, ancient ruins, and traditional villages that reflect its historical importance [

42]. For example, the town of Edipsos is renowned for its thermal springs, which have been used since antiquity. However, many cultural assets remain underutilized or at risk due to neglect and lack of funding for preservation [

31] (

Figure 3). The region’s cultural heritage has significant potential to support sustainable tourism and community development if properly managed.

The first human presence on Euboea can be traced back to the prehistoric era, with the earliest signs of civilization dating to the Bronze Age (3000–1100 BC) [

43]. The first settlements appeared in both the mountainous and coastal areas of the island. Chalkis, one of the largest city-states of the ancient world, maintained strong trade and political ties with other cities in Ionia and the Aegean. During the Classical period (5th–4th century BC), Euboea was under the influence of Athens, and many cities on the island participated in the Athenian League. At the same time, Euboea continued to be an important trade hub, and frequent battles for independence against the Macedonians occurred [

44].

During the Roman period, Euboea became part of the Roman Empire, and after the establishment of Byzantium, the island was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire. Chalkis became an important commercial and naval center during this time [

45]. The Venetians controlled Euboea, which they called Negroponte, from the early 13th century until the late 15th century, with intermittent interruptions by other powers such as the Byzantines and Ottomans [

46]. The island came under Ottoman control in 1470 and became strategically important for the management of the Aegean. During the Greek War of Independence, Euboea played a key role in the resistance against the Ottomans, and Chalkis became a center of revolutionary activity [

41]. After Greece gained independence, Euboea underwent several changes in terms of economic development. Today, the island is known for its natural beauty, rich cultural heritage, and significance to the tourism industry.

Northern and Central Euboea are renowned for their diverse and well-preserved natural landscapes, which are protected within the island’s environmental reserve. This region is home to lush forests, wetlands, and coastal ecosystems that provide critical habitats for a wide variety of plant and animal species. The northern part of the island, particularly around the protected area of the Northern Evian Gulf, is rich in biodiversity, with unique flora and fauna that thrive in its varied ecosystems [

41]. The area is also famous for its river systems, such as the Kireas River, which supports diverse wildlife and contributes to the region’s ecological balance. Central Euboea, with its mountainous terrain, is home to several protected forests, such as the Dirfys mountain range, which provides a sanctuary for rare species, including the Euboean wild goat [

47]. Additionally, the wetlands of Lake Doirani and the coastal marshes in the region offer crucial breeding grounds for migratory birds, making the area a key stop on the flyway for many species [

41]. The conservation efforts in Northern and Central Euboea not only preserve these valuable ecosystems but also promote sustainable tourism, encouraging visitors to experience the natural beauty while ensuring its protection for future generations.

The trails of Northern and Central Euboea offer a unique blend of natural beauty, cultural heritage, and outdoor adventure. From the rugged peaks of Dirfys Mountain to the serene forests of Agali and the historical pathways of Prokopi, these trails provide opportunities for exploration, relaxation, and connection with nature. With proper development and promotion, they have the potential to become a cornerstone of sustainable tourism in the region, benefiting both visitors and local communities [

48] (

Figure 4).

Agriculture in Northern and Central Euboea is a cornerstone of the local economy and cultural identity, characterized by traditional practices and diverse products. Olive cultivation, particularly around Istiaia and Prokopi, produces high-quality olive oil, while viticulture thrives in areas like Mount Dirfys, with native grape varieties such as Mavroudi and Savvatiano [

49]. Livestock farming, especially sheep and goat rearing, supports artisanal cheese production, and chestnut and walnut orchards in mountainous regions like Agali are celebrated for their cultural and economic value [

50]. Beekeeping yields thyme and pine honey, and fruit and vegetable farming benefits from the region’s fertile valleys. Additionally, in North Evia there are two zones of leucolith deposits, which have a total length of 30 km and a width of 16–20 km. The eastern zone includes the Mandoudi, Galataki, Pili, etc., mines, while the western zone includes the Varia—Rema, Troupi, etc., mines.

In Pili and in the former settlements of Agia Triti and Livadakia, there was great mining activity mainly before the war, but also after the war. In these locations there was mining, transport of the ore by aerial and fixed wagons, processing, storage and again transport by wagons via the sea staircase that had been built on the beach of Pelion to the barges with the barges and to the bay of Atalantos via wagons from Livadakia.

However, challenges such as depopulation, climate change, and limited market access threaten sustainability (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) [

47]. Opportunities lie in organic farming, agritourism, and cooperatives, which can enhance resilience and promote local products while preserving rural traditions.

Tourism development in Northern and Central Euboea is increasingly focused on leveraging the region’s natural beauty, cultural heritage, and sustainable practices to attract visitors while preserving local identity. The area boasts diverse attractions, including the thermal springs of Edipsos, the lush forests of Mount Dirfys, and traditional villages like Steni and Agali, which offer opportunities for ecotourism, agritourism, and cultural tourism [

50]. Initiatives such as hiking trails, chestnut festivals, and farm-to-table experiences highlight the region’s agricultural and natural wealth, while historical sites like Venetian castles and Byzantine monasteries add cultural depth [

51]. However, challenges such as limited infrastructure, seasonal tourism, and the need for greater promotion hinder growth [

50]. By investing in sustainable tourism models, improving accessibility, and engaging local communities, Northern and Central Euboea can enhance its tourism sector, ensuring economic benefits while safeguarding its unique environment and heritage.

4. Assessment of Results

During the study area analysis, thirty-three points of cultural reserve were identified, including prehistoric, archaeological, Byzantine, and Medieval monuments (

Figure 7), and twenty points of environmental reserve were mapped (

Figure 8). Additionally, the trail network was mapped as well, consisting of twenty routes (

Figure 9). Nine traditional settlements of Central Euboea and eight traditional settlements of Northern Euboea with architectural or historical interest were also mapped and identified.

The tourist experience in Central and North Evia is limited to accommodation and food, and, more rarely, to some other activities, qualitatively and quantitatively degraded in relation to the potential of the region (natural and cultural reserve). This is to a significant extent the generative cause of the two main problems of the tourism industry in the region: (a) the very limited tourist season and (b) the, in economic terms, low quality of tourists [

50]. The area’s trail network consists of an important attraction that could serve as a base for the design of the overall plan of development. Additionally, taking into consideration the area’s agricultural tradition, the development of agrotourism in Central and Northern Euboea requires the exploitation of the environmental and cultural heritage of the region. The implementation of the proposals concerning the environmental and cultural upgrading of the tourism product will provide the necessary infrastructure for the development of this mild but high-quality form of tourism, which is very much in keeping with the special character of North and Central Evia [

50]. Finally, accessibility is a major issue to be addressed, focusing on marine tourism as well as the sufficiency of the accommodation facilities.

The sustainable development proposals could be described in the above categories:

Revealing of cultural and environmental assets,

Revealing of traditional practices and activities,

Promotion of agritourism,

Improvement of accessibility,

Design of accommodation facilities.

4.1. Proposal Scheme for Cultural Routes

Focusing on the revealing of cultural and environmental assets, traditional practices and activities, in the framework of the AEI program, five new cultural routes were designed (

Figure 10).

4.1.1. The Path of Agali—Connection with Monuments (~31.5 Km)

The Agalis Trail lies on the western slopes of Mount Dirfys, beginning at the village of Agios Athanasios, near the Agalis Gorge, and ending in the region of Attali. This scenic route passes through communities known for their rich natural environment and significant cultural landmarks, including monasteries and Byzantine churches, offering a unique blend of nature and heritage exploration. The trail starts in Agios Athanasios (28 km northeast of Chalkida), where visitors can access the Agalis Gorge—a tranquil landscape of small waterfalls, fir trees, and streams. Heading southeast, a short detour leads to the Holy Monastery of Agios Dimitrios Loutsa. Nearby, visitors may also explore the Byzantine Church of Palaio Panagia and the Monastery of Agia Paraskevi, noted for its carved wooden iconostasis. The path continues through Kato Steni, past the cemetery chapel, and into the area of Vounoi, home to the churches of the Transfiguration of the Saviour and the Holy Apostles. It then proceeds through Amfithea and toward the village of Kathenoi, where the Church of Saint George is located. From there, it reaches the settlement of Palioura and the Monastery of Panagia Myrtidiotissa. Following the provincial road, the route passes the Church of the Ascension in Makrykappa and ends in Attali. At the center of Attali are the ruins of the 10th-century Byzantine Monastery of Saint Nicholas, from which the later Church of the Presentation of the Virgin was built.

The monuments that are proposed to be interconnected in a route with the Agali Gorge—Tsergon Ridge as its axis are: (a) Holy Church of Agia Paraskevi in Loutsa, (b) Holy Monastery of St. Dimitrios in Loutsa, (c) Holy Church of Panagia (Paleopanagia) in Steni, (d) Holy Church of Transfiguration of the Saviour in Vounous (chapel of the cemetery), (e) Holy Church of the Holy Apostles in Vounous, (f) Holy Church of St. George in Kathenoi, (g) Monastery of the Theotokos/Panagia Monomeritissa in Eria Kathenon, (h) Holy Church of the Ascension in Makrykapa and (i) Holy Church of the Presentation of the Virgin Mary and St. Nicholas in Attali.

This path is typical of cultural trails (in this case, pilgrimage-related “Tourism”), which are in the vicinity of a large city with adequate services and accommodation infrastructure. Specifically, this path is very close to the city of Chalkida and the coastal municipality of Nea Artaki, which can function as “bases” for daily or weekly excursions like the one in this path. The wealth of religious monuments makes this path a recurring excursion—based in Chalkida or Nea Artaki—since it necessitates many daily visits to one or a couple of the path’s many monasteries and churches. Thus, no new accommodation infrastructure is required. However, restaurants, taverns, and businesses (mainly local products, souvenirs and religious items) can be established in the vicinity of each monument to serve the visitors.

4.1.2. The Path of Iro/Hiking Route—Connection with Monuments (24.4 Km)

Overlooking the northern Evian Gulf, near the gorge of Ladas, there is a path, which today is known as “The Path of Iro”. In the past, it was used by loggers, quarrymen, resin collectors and shepherds to move to their work areas, while it also connected the village with a quarry. In the area around the path of Iro, there are important cultural attractions, capable of attracting visitors with a religious/pilgrimage tourism orientation. The monuments proposed to be interconnected in a route are: (a) Holy Monastery of Panagia Peribleptou, (b) Holy Monastery of Agios Ioannis Kalyvitis and (c) Holy Monastery of Virgin Mary Makrimalli.

This path is similar to the above, in the sense that its proximity to Chalkida (a medium-sized city) does not necessitate the development of significant accommodation infrastructure. However, the environmental character (hiking) of this path may promote certain types of business, either in the nearby villages or in Chalkida to provide equipment and services (e.g., guiders) to visitors interested in hiking. Also, businesses relevant to or promoting the sustainability of the local environment (e.g., biological local agricultural products) and adventure-related tourism are potentially more attractive to this type of visitor. The traditions of the area (logging, resin collection, and quarrying) can either be promoted via info kiosks along the routes or at Chalkida, or through ICT applications.

4.1.3. Route of Medieval Towers—Central Euboea (62.2 Km)

There are numerous medieval monuments in the Municipality of Dirfya—Messapia. The medieval towers located in the area are a remarkable example of medieval monuments potentially capable of becoming an attraction as part of a network of medieval monuments that are well signed and linked to a thematic route.

The monuments proposed to be interconnected in a route are (a) Tower of Politica, (b) Tower of Kamaritsa, (c) Castri in Psahna, (d) Tower of Triada, (e) Tower of Figa, (f) Tower of Pissona, (g) Tower of Amphithea, (h) Tower of Vouna, (i) Tower Skuderi, and (j) Tower of Mistros.

This route is similar to the Path of Agali in the sense that it, too, places emphasis on built cultural heritage. However, the cultural assets involved, unlike monasteries or churches, are largely “inactive”, basically being preserved buildings or structures. As a result, the visitors of the route are a more specific target group, i.e., those interested in medieval history and architecture. Again, the nearby cities of Chalkika and Nea Artaki can be used as ‘bases”; however, the route can also function as a daily “diversion” and short excursion for northbound travelers and visitors of North Euboea. Alternative target groups of this route may include conference/workshop participants, either based in Chalkida, or in local hotels and motels that can support such activities. Food and business services along the route can develop, potentially exploiting the medieval history of the area through corresponding promotion campaigns and local products.

4.1.4. Route of Agricultural Settlements in the Municipality of Mantoudi-Limni-Agia Anna (108 Km)

The villages included in this route are: (a) Kirinthos, (b) Metochi, (c) Spathari, (d) Kechries, (e) Skepasti, (f) Kourkooli, (g) Papades, (h) Kerasia and (i) Agia Anna.

These villages are located on or next to main roads, are in close proximity to each other and define an area of outstanding natural beauty with many points of interest (Drimonas Falls, protected oak forest, petrified forest, mountain crops, pomegranate cultivation and standardization, beekeeping, wild mushrooms, herbs, infrastructure and conditions for new crops, and cheese dairies). The inhabitants of these villages are largely resin collectors, farmers, stockbreeders and beekeepers (usually combining two or more activities) and own smaller or larger areas of mountain farmland. Most of them were also significantly affected by the major fire of 2021 and its consequences, so they will have to redefine their professional activities by adapting to a new reality.

This route is typical of agricultural routes aiming to promote and strengthen the local agricultural sector. The 2021 fire had a significant impact; thus, much of the local agricultural products cannot be produced in the short term. Gradually, however, many activities are recuperating and returning to their previous capacities; others require reestablishment or reorientation; for example, resin collectors initially—after the fire—concentrated on forest’s and land flood protection and logging (cleaning the burnt trees). The development of accommodation infrastructure is not a priority (Agia Anna is a famous coastal resort municipality); the utmost priority is the regeneration of agricultural activities.

4.1.5. Route of Agricultural Settlements in the Municipality of Istria—Edipsos, Including the Villages (57.2 Km)

The villages included in this route are: (a) Kokkinomilia, (b) Yaltra, (c) Keramia, (d) Kamatriades, (e) Galatsades, (f) Taxiarchis, (g) Agdines and (h) Gouves.

These villages are located near main roads, are in close proximity to each other and delimit an area of outstanding natural beauty with many points of interest (Fountains, Kremasi Falls, broad-leaved forests—oaks and chestnut trees, coniferous and mixed forests, interesting crops (figs, fruits, cereals, olives), beekeeping, livestock farms, wild mushrooms (broad-leaved mushrooms such as trumpets, figs and chantarelles), herbs, processing plants for local products such as PDO Taksiarchi figs and wineries—distilleries). The inhabitants of these villages are loggers, resin collectors, farmers, stockbreeders and beekeepers (usually combining two or more of the above activities) and own small or large areas of mountainous/semi-mountainous farmland. The development of agrotourism in this arc will also provide development prospects for smaller adjacent villages such as Simia, Voutas, Kryoneritis and others.

This route is similar to the above route, with emphasis on agricultural settlements. However, this route is closer to the coastline and includes the internationally acclaimed spa of Edipsos. Edipsos, with many established hotels, room-to-let installations, restaurants and a port, arguably serves as the base point of these northern routes and tourism products. This route is a prime example of expanding the attractiveness of established tourist destinations (Edipsos, and all coastal municipalities along the north coast of Euboea) by offering complementary destinations of environmental interest, with emphasis on agrotourism. Due to the rather established accommodation infrastructure and the relatively adequate access (through Edipsos), this route can serve conference tourism or related activities. Its proximity to Volos (and consequently to the Pilio area in Magnesia) and the Sporades islands nearby through the Istiaia port means it can also function as an alternative daily destination from these touristic sources. As such, the target groups in this area can shift from traditional family-oriented groups toward youth and environmentally sensitive tourist groups. In general, this route is typical of rebranding a group of established local resorts, focusing on more modern and alternative target groups.

4.2. Proposal Scheme for Revealing Traditional Practices and Activities and the Promotion of Agritourism

The proposed development strategy for Northern and Central Euboea emphasizes the revival of traditional practices and activities, along with the promotion of agritourism. In addition to the design of two thematic cultural routes, the strategy includes several interrelated initiatives. These involve the diversification of agricultural production through the introduction of new crops such as truffles, kiwis, pomegranates, aloe vera, and mountain vineyard varieties, aiming to expand and enrich the region’s agricultural profile. Emphasis is also placed on supporting enterprises engaged in the production, standardization, and certification of local products through structured programs of information dissemination, training, financial support, and continuous knowledge transfer.

A key component of the strategy is the development of model olive oil standardization and processing units, accompanied by incentives for the cultivation and certification of organic olive oil products. Traditional practices are further highlighted through the proposed reopening of historic mills, such as the one in Kerasia, for the production of carob and other locally sourced flours. The establishment of a facility for the standardization and packaging of honey and other apicultural products—including royal jelly, propolis, pollen, wax, and cosmetic items based on bee products—is also planned.

Further efforts include the creation of local wineries with organized grape cultivation and the development of a distinctive regional wine brand, as well as the installation of a processing and packaging plant for organic aloe vera. The strategy additionally proposes support for local cheese dairies, particularly in relation to the standardization and certification of traditional white cheeses. Regional tourism is expected to benefit from initiatives such as the integration of the “Greek Breakfast” program into local hospitality offerings, encouraging the use of certified regional products in hotels across Central Greece. Lastly, the industrial heritage of the region will be preserved through the reuse of abandoned limestone mining buildings in areas such as Pili and Paraskevorema, thereby linking cultural preservation with sustainable development.

Simultaneously, the improvement of accessibility within Northern and Central Euboea is a central focus, particularly regarding maritime infrastructure (

Figure 11). Proposed interventions include the modernization and enhancement of port facilities across all local ports and tourist shelters, along with improvements in transport networks connecting these ports to the broader regional infrastructure. Moreover, an extension of the operational season for maritime connections to Northern Euboea is recommended, addressing current limitations due to the region’s primary dependence on road access via National Road E75 (Athens–Chalkida) and National Road E77 (Chalkida–Istriaia–Edipsos). Focusing on the sufficiency of accommodation facilities, emphasis is given to the creation of new agritourism facilities in the villages of the rural network and to the creation of guesthouses for the important monasteries of Saint Ioannis Rossos and Saint David (

Figure 12).

4.3. ICT Tools

One of the primary objectives of the AEI project was to integrate diverse datasets into a cohesive and practical tool. To achieve this, the use of Geographic Information Systems (GISs) was deemed essential. Thematic and interactive maps provide a clear and accessible overview of proposed routes, points of interest, and specific area characteristics, making them understandable even for non-specialists. Building on this geospatial data management framework, a unified interactive web map was developed to showcase and analyze the project’s study sites. The map’s primary purpose was to visually represent existing tourist attractions, points of interest, and cultural and natural heritage sites but also to include the proposed tourist routes and planned interventions for each location [

52] (

Figure 13).

To address the lack of knowledge about funding programs and funding tools combined with the inability to manage different resources at an integrated local level, a development platform was developed as part of the AEI project that offers the possibility of managing different financing tools to finance development proposals. The development platform includes the AEI proposals and suggested financial tools for their implementation, the relative contemporary sustainable development project for the area, and information about the available financial tools for future projects (

Figure 14).

Finally, digital tourist maps involving Northern and Central Euboea’s cultural and environmental assets, as well as the proposed cultural routes, were created along with a touristic platform for information and promotion (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

4.4. Socioeconomic Assessment of the Results

The assessment focuses on economic indicators, such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and production value, at both regional and national levels. Socioeconomic data were collected from the Hellenic Statistical Authority, the Merchants’ Chamber of Evoia Prefecture, the Technical Chamber of Greece—Section of Evia and the Research Institute for Tourism (RIT), which was an AEI program partner. The analysis is based on a scenario anticipating an increase in tourism. To implement the research, a bibliographic review was conducted, exploring the relationship between sustainable development and key areas such as investment, tourism, cultural heritage, and the environment. Additionally, the current tourism landscape on the island was examined. These steps informed the assumptions used in the input–output model, which was applied to evaluate the direct and indirect socioeconomic impacts. The findings indicate that sustainable development proposals yield positive economic outcomes, with the magnitude of these effects depending on the scale of investments [

53].

Key characteristics of Northern and Central Euboea, including environmental features, tourism patterns, and other relevant data, were identified. Based on these, the required investment in cultural and environmental reserves was calculated. The analysis assumed an extension of the tourist season from May–October to April–November, driven by the proposed investments. The additional tourism revenue generated during April and November, particularly in the accommodation and food and beverage sectors, was also estimated. The total investment, combining both the proposed initiatives and the expected tourism growth, was incorporated into the input–output model. This investment was allocated to relevant economic sectors.

The results show that for every EUR 1 million invested in Central and Northern Euboea, regional GDP increases by EUR 650.1 thousand and 14 new jobs are created. At the national level, the same investment boosts GDP by EUR 1.25 million and generates 28 new employment opportunities. These findings highlight the significant economic benefits of sustainable development initiatives in the region.

5. Discussion

The results of this study confirm the potential of integrated spatial planning and heritage-based development to revitalize peripheral and post-disaster regions such as Northern and Central Euboea. Empirical evidence highlights how combining spatial planning with rural tourism can significantly enhance local economic resilience and preserve cultural assets [

54,

55,

56]. The geospatial documentation and visualization of cultural and environmental assets—via WebGIS and participatory mapping—form a solid foundation for crafting sustainable tourism strategies [

57,

58,

59].

The methodology for developing new products and services in this study is characterized by innovation in terms of:

Analysis and documentation of the Cultural and Environmental Reserve (CER): assessing its value in order to model the upgrading of new potential tourism resources into products.

Upgrading the CER: creating new tourist resources, services, and products.

Designing and promoting new tourist resources and services, with the aim of channeling tourist traffic from more to less developed areas.

Developing new ICT tools for managing/upgrading the CER, either by individual users or by relevant authorities.

Enriching ICT with the use of spatial information in a way that is organically linked to the integration of new tourism resources, services, and products into the local and regional tourism economy.

Providing scientific support for the redesign, planning, and implementation of development projects, infrastructure improvement, and augmentation measures to the local economy.

A focus on circular economy, social cohesion and sustainability principles.

The thematic cultural routes emerging from this study exemplify models that shift away from mass tourism toward immersive, place-based experiences rooted in history, landscape, and community [

21,

32]. GIS-informed network analyses support optimal route design and equitable visitor distribution, helping to mitigate seasonality and territorial disparities [

60,

61].

The integration of ICT and spatial decision support tools, including WebGIS, digital tourism platforms, and MCDA frameworks, bolsters transparency and fosters participatory governance, enabling stakeholders to plan and promote their territory effectively [

35,

62]. These tools enhance accessibility to spatial data and enable evidence-based planning.

From an economic standpoint, input–output modeling provides an early indication that heritage-led investments can yield measurable benefits in terms of regional GDP and employment [

22,

39]. This aligns with published studies supporting the microeconomic viability of heritage tourism in rural regions [

33], though it remains contingent on planning assumptions without post-implementation validation.

A key insight from this research is the critical need for multisectoral coordination—between heritage, infrastructure, agriculture, education, and environmental protection. Studies confirm that sustainable rural development thrives when such sectors are integrated through collaborative governance [

36]. Community empowerment, via capacity-building and institutional backing, further reinforces long-term sustainability [

21,

24].

Nevertheless, limitations persist: the study is scenario-based and lacks behavioral or climate-risk modeling, echoing broader calls for integrating dynamic variables into GIS-driven planning [

2,

62]. Furthermore, local-level data gaps—in income, migration, and tourism flows—impact modeling granularity and accuracy.

Future research should emphasize:

Longitudinal monitoring of implemented interventions;

Creation of rural tourism sustainability indicators;

Deeper civic engagement via digital platforms;

Comparative analysis of similar heritage-led initiatives in other peripheral or disaster-affected areas.

In conclusion, Northern and Central Euboea may serve as a benchmark for heritage-led, community-driven, digitally enriched sustainable development in rural and semi-remote regions, transitioning from crisis to resilience.

6. Conclusions

The application of the proposed methodology in Northern and Central Euboea led to the development of an integrated spatial and strategic plan for the enhancement of cultural and environmental assets, the design of thematic routes, and the promotion of alternative tourism products. A total of 33 cultural heritage sites were identified and documented across the study area, including prehistoric, Byzantine, and medieval monuments. Additionally, 20 natural sites of ecological or landscape significance were mapped, and 20 hiking and pilgrimage trails were documented through field research and spatial analysis. These were georeferenced using open-source Quantum GIS (QGIS) desktop (

https://qgis.org/) application and visualized through a digital map, which also included 17 traditional settlements with architectural or historical value. Based on the spatial distribution and thematic clustering of these assets, five cultural and agritourism routes were designed. Each route links natural and cultural landmarks while promoting specific elements of the local identity, such as religious heritage, medieval towers, traditional farming villages, and abandoned mining infrastructure. These routes were developed to address the seasonal limitations of tourism in the region and to expand tourist activity into inland areas.

In addition to physical mapping, a comprehensive digital platform was created to support the management and promotion of tourism development proposals. This platform integrates the AEI project interventions with potential funding tools and facilitates project monitoring by local stakeholders.

Furthermore, the study produced interactive tourism maps and a WebGIS environment that visualizes key attractions, proposed routes, and supporting infrastructure. These tools aim to empower local authorities and tourism actors by improving accessibility to data and supporting informed decision-making.

The impact of the proposed interventions was assessed through an input–output analysis. The model indicated that for every EUR 1 million invested in the region’s cultural and environmental reserve, there is a projected increase of approximately EUR 650,000 in regional GDP and the creation of 14 new jobs. At the national level, the same investment is estimated to contribute EUR 1.25 million to GDP and 28 new employment opportunities. These results confirm the potential of alternative tourism as a mechanism for regional economic revitalization, particularly in post-disaster contexts.

Overall, the results highlight the feasibility and scalability of the integrated approach developed in this study. By combining spatial data, digital tools, and community-based planning, the methodology provided a coherent strategy for the reactivation of local economies through sustainable tourism rooted in cultural and environmental heritage. By implementing these proposals, Northern and Central Euboea can transition from a region facing post-disaster challenges to a model of sustainable tourism development that balances cultural heritage preservation, environmental conservation, and economic resilience.