Abstract

The global rise in urban-related health issues poses significant challenges to public health, particularly in cities facing socio-economic crises. In Lebanon, 70% of the population is experiencing financial hardship, and healthcare costs have surged by 172%, exacerbating the strain on medical services. Given these conditions, improving the quality and accessibility of green spaces offers a promising avenue for alleviating mental health issues in urban areas. This study investigates the psychological impact of nine urban public spaces in Beirut through a comprehensive survey methodology, involving 297 participants (locals and tourists) who rated these spaces using Likert-scale measures. The findings reveal location-specific barriers, with Saanayeh Park rated highest in quality and Martyr’s Square rated lowest. The analysis identifies facility quality as the most significant factor influencing space quality, contributing 73.6% to the overall assessment, while activity factors have a lesser impact. The study further highlights a moderate positive association (Spearman’s rho = 0.30) between public space quality and mental well-being in Beirut. This study employs a hybrid methodology combining Research for Design (RfD) and Research Through Designing (RTD). Empirical data informed spatial strategies, while iterative design served as a tool for generating context-specific knowledge. Design enhancements—such as sensory plantings, shading systems, and social nodes—aim to improve well-being through better public space quality. The proposed interventions support mental health, life satisfaction, climate resilience, and urban inclusivity. The findings offer actionable insights for cities facing public health and spatial equity challenges in crisis contexts.

1. Introduction

The global increase in diseases associated with urban living, leading to increased disability and premature mortality, is escalating at an alarming rate [1]. While the physical health effects of urban living are well-recognized [2,3], recent revelations highlight its adverse impact on mental health. Urban living is associated with nearly a 40% higher risk of depression and over 20% higher anxiety rates [4], as well as up to a 2.37 times higher risk of schizophrenia [4]. The COVID-19 pandemic and global economic crisis have worsened mental health issues, intensifying loneliness and stress [5,6,7,8]. In addition, as urbanization increases, more people are exposed to environmental stressors that may negatively impact mental health [9]. A study conducted in Brussels examined the relationship between urban environmental factors—such as air pollution, green spaces, noise, and building morphology—and mental health outcomes [9]. The findings indicated that exposure to traffic-related air pollution (black carbon, NO2, PM10) was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of depressive disorders, with individuals experiencing high black carbon exposure having twice the odds of developing depression compared to those less exposed. However, no significant associations were found between mental health and urban greenness, noise, or building morphology [9]. Another study conducted by Xu et al. (2023) investigated the effects of urban living environments on mental health using data from 156,075 participants in the UK Biobank [10]. The study found that urban environmental factors such as social deprivation, air pollution, street network, and urban land-use density were positively correlated with affective symptoms, mediated by brain volume differences linked to reward processing. This relationship was moderated by genes associated with the stress response, explaining 2.01% of the variance in brain volume differences [10]. Conversely, factors like urban greenness and accessible destinations were negatively correlated with anxiety symptoms, mediated by brain regions involved in emotion regulation and moderated by the EXD3 gene, explaining 1.65% of the variance [10]. The study suggests that specific urban environmental profiles may impact different psychiatric symptoms through distinct neurobiological mechanisms [10,11,12].

Moreover, socioeconomic inequalities exacerbate the impact of urban stressors, with concentrated poverty in urban areas being a key factor in the development of mental health issues [5,13]. Recent studies have highlighted a bidirectional causal relationship between poverty and mental illness, where economic hardship not only contributes to the onset of mental health conditions but also deepens the severity of existing ones [14]. Those living in poverty are generally 1.5 to 3 times more likely to experience depression or anxiety compared to wealthier individuals within the same environment [14]. In light of the increasing strain on healthcare systems worldwide driven by growing demand and escalating costs, there is a global shift toward preventive healthcare, aiming to reduce the burden on medical systems by addressing illnesses before occurring and enhancing overall health and well-being [15]. Considering the above challenges, green spaces have emerged as a potential solution to the multifaceted challenges of urban living, offering a wide array of ecosystem services such as air and water purification, climate regulation, and biodiversity conservation. These services play a crucial role in mitigating environmental stressors, including air pollution, which are closely linked to various mental health issues. Access to green spaces has been consistently associated with improved mental health outcomes, such as reduced stress levels [16], a lower risk of depression [17], and enhanced cognitive function [18].

Specifically, studies show that for every 10% increase in the percentage of green space, the risk of depression decreases by 3% [17]. By addressing both environmental stressors and mental health concerns, green spaces contribute to overall well-being, positioning landscape planning and landscape architecture as a key strategy in creating healthier urban environments. Furthermore, urban green spaces play a central role in fostering healthy living and improving the quality of life [19]. The benefits of green spaces are well-supported by psychological theories [20], including Attention Restoration Theory (ART) [21,22] and Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) [23], which highlight the positive impact of natural environments on mental well-being. ART suggests that exposure to nature can restore mental fatigue and improve concentration, while SRT posits that natural environments can alleviate psychological and physiological stress. These theories underscore the importance of incorporating green spaces into urban planning to enhance mental health, foster healthy living, and improve overall well-being [20]. However, many urban areas, including Beirut, Lebanon, face a critical shortage of green spaces. Lebanon has been severely affected by ongoing economic, political, and social crises, which have had a profound impact on both its landscape and people. The country’s healthcare system is under considerable strain, with limited access to mental health services and escalating healthcare costs [24,25]. This, combined with high poverty rates and widespread economic hardship [26], has contributed to a mental health crisis, marked by high rates of depression and anxiety [27,28]. In this context, increasing access to green spaces offers a promising pathway to improve both the mental and physical well-being of the Lebanese population. Green spaces are increasingly recognized as critical components of healthy cities, offering ecosystem services that mitigate environmental stressors and contribute to psychological restoration [19]. However, Lebanon’s urban areas have some of the lowest green space ratios, with Beirut falling far short of the recommended standard of 9 m2 of green space per capita, a benchmark commonly adopted in developed countries [29]. Beirut currently provides only 0.8 m2 of green space per person, significantly below this threshold [30], with only 11% of the city’s public spaces dedicated to green areas. This shortage of accessible public spaces has further exacerbated the disconnection between residents and nature, underscoring the need for interventions that enhance urban green spaces to mitigate the impacts of urban stressors.

Despite the critical importance of green spaces for mental health, there is a notable lack of empirical research in Lebanon examining the psychological benefits of public green infrastructure. This gap is partly due to the country’s prolonged conflicts and socio-political instability, which have hindered systematic urban research and planning. As a result, evidence-based strategies to guide the design and management of public open spaces—particularly in relation to mental well-being—remain underdeveloped. Existing studies in the region often lack methodological rigor, spatial specificity, or actionable design implications. Recent international research has emphasized that not all green spaces contribute equally to mental health outcomes, highlighting the need to identify the types, characteristics, and quality of green spaces that are most beneficial [30,31]. For example, Ribeiro et al. (2024) found that proximity to urban green spaces was associated with significantly lower odds of depression among older adults in Porto, Portugal, while natural and agricultural green spaces were linked to higher odds [32]. Similarly, Xu et al. (2025), in a systematic review of 22 studies, reported that natural elements—particularly vegetation diversity and water features—were consistently associated with improved mental well-being, while the effects of spatial features such as accessibility and amenities were more context-dependent [31].

Building on these insights, the present study investigates how different types of public open spaces in Beirut—urban parks, promenades, and squares—affect psychological well-being, with a focus on accessibility, spatial quality, and user satisfaction. It addresses the research gap through a novel, interdisciplinary approach that integrates methods from Environmental Psychology [33] and Landscape Architecture [34]. Using a cross-sectional survey of 297 users, analyzed through validated psychological instruments (PANAS and SVS), the study captures real-time user perceptions across a diverse range of public spaces. These findings are then translated into spatial strategies using a Research Through Design (RTD) framework, allowing design itself to function as a method of inquiry. While prior studies have linked green space access to mental health, few have examined the specific qualities of public spaces that influence psychological well-being—particularly in cities under acute socio-economic and environmental stress. In the Middle East and North Africa region, research remains scarce, and there is a lack of integrated methods combining empirical evaluation with design-oriented frameworks. This study addresses that gap by applying RTD and RfD to produce context-sensitive, user-informed spatial interventions.

The originality of this research lies in its integration of an empirical evaluation with spatial design methodologies to generate actionable, context-specific interventions, its contextual focus on a city under acute socio-environmental stress, and its translation of psychological data into spatial design recommendations. Its significance is reflected in applying a hybrid RfD–RTD model to develop design solutions that support mental well-being, social inclusion, and urban resilience. Its significance is reflected in its potential to inform urban design, public health, and climate adaptation strategies in similarly vulnerable urban contexts. The study’s rigor is demonstrated through its robust sampling framework, statistical analysis, and interdisciplinary integration, offering a replicable model for evaluating and enhancing the mental health benefits of urban green infrastructure.

The aim of this study is to explore the potential of landscape interventions to address mental health challenges in Beirut by improving the quality and accessibility of public green spaces. Specifically, it seeks to do the following:

Quantitatively assess the impact of various open spaces in Beirut on individual mental health;

- Identify and rank spatial characteristics linked to higher-quality public spaces;

- Examine barriers to public space use; and

- Develop design recommendations that enhance green space quality, promote social inclusion, and improve accessibility.

By addressing these objectives, the study contributes to the creation of healthier, more resilient urban environments and provides transferable insights for other cities facing similar challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used a mixed methods approach within a pragmatic RTD framework, integrating RfD and RTD methodologies to investigate the relationship between urban public spaces and mental well-being in Beirut. The methodology consists of three key components: (1) site selection and empirical data collection using validated psychological instruments (PANAS and SVS), (2) quantitative analysis of user survey responses to assess spatial quality and well-being indicators, and (3) a qualitative thematic analysis of design interventions derived from the RTD process.

2.1. Description of Study Area

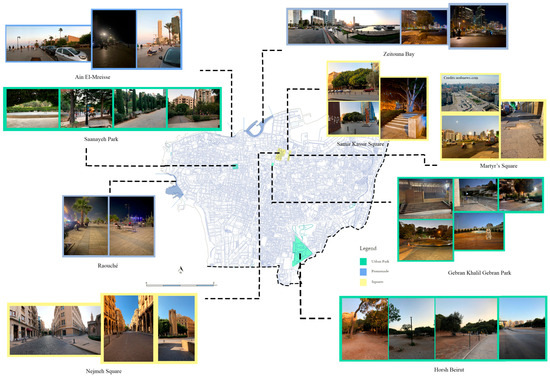

This study focuses on Beirut, a densely populated metropolis with a limited number of public open spaces. It examines three primary types of frequently accessed urban public open spaces that reflect the city’s limited yet varied spatial options: urban parks, promenades, and squares (Figure 1). Based on the specifications for urban public open spaces outlined by UN-Habitat (2018) [35] (Table 1), we selected nine well-known sites to represent different public space typologies and capture the preferences of a diverse user base (Figure 2). The selected urban parks include Horsh Beirut (Site 1), Saanayeh Park (Site 2), and Gebran Khalil Gebran Park (Site 3). The promenade sites are Zeitouna Bay (Site 4), Ain El-Mreisse Corniche (Site 5), and Raouché (Site 6). The square sites include Samir Kassir Square (Site 7), Martyr’s Square (Site 8), and Nejmeh Square (Site 9). Although these sites vary in their spatial distribution across the city, some are in proximity, particularly the squares. Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials outlines the spatial characteristics of each site, drawing on UN-Habitat’s criteria for quality public spaces. This description provides a critical framework for the subsequent analysis of how a site’s spatial characteristics may influence patterns of use and public perception.

Figure 1.

Map of publicly owned parcels and open sites used by the public in municipal Beirut (source: Beirut Urban Lab).

Table 1.

Evaluation of Beirut public open spaces according to UN-Habitat Criteria.

Figure 2.

A map showing the spatial distribution of selected public spaces in Beirut and their key spatial challenges (source: author).

2.2. Participants

This study used a random sampling approach to ensure diversity among participants, with individuals assessed independently to capture broad demographic profiles and user experiences across the nine selected public open spaces. All individuals present at the site during the survey period were approached independently, allowing us to collect real-time feedback regarding their perceptions and interactions with the spaces.

To determine the required sample size, we considered Beirut’s estimated 2023 population of 2,421,354. Using the rule of thumb for sample size estimation, a 10% margin of error (MOE) at a 95% confidence level resulted in a minimum required sample size of 96 responses. To strengthen statistical robustness, the study collected a total of 297 completed surveys, with 99 responses distributed equally among the three public space typologies (urban parks, promenades, and squares) and 33 surveys administered at each of the nine study sites. To further ensure representativeness, we systematically conducted data collection across different days of the week and various times of day. This approach accounted for temporal variations in participants’ behaviors, experiences, and perceptions, thereby reducing selection bias and enhancing the generalizability of the findings. This stratified, site-specific sampling strategy minimized selection bias and provided a comprehensive, balanced dataset reflective of Beirut’s diverse urban public space users.

2.3. Study Survey

This study utilized a cross-sectional, quantitative survey design [36] to investigate perceptions of and satisfaction with urban public open spaces in Beirut and their relationship with psychological well-being. The survey formed the empirical foundation of a broader RfD and RTD framework, enabling the integration of user experience data into spatial strategy development A structured, face-to-face questionnaire was administered in Arabic over a one-month period between July and August 2023, across the nine selected public open spaces. To ensure cultural appropriateness and internal consistency, the instrument was pilot-tested with 40 participants; results from this pilot were not included in the final analysis. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.825 indicated high reliability, confirming the questionnaire’s internal consistency. Developed based on established, validated scales [1,37,38], the instrument was divided into two sections (see Supplementary Materials). The first section assessed individuals’ perceptions of and satisfaction with public spaces, focusing on factors such as accessibility barriers, social inclusivity, site management quality, site intensity, and the presence of natural and functional features. The second section measured users’ psychological well-being, utilizing the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) and the Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS) to assess positive and negative affect, as well as energy and vitality levels, respectively [1,37,38]. All participants provided verbal informed consent before participating.

2.4. Intervention and Implementation

Based on the survey results, which identified specific public open spaces with the lowest scores in both perceived quality and psychological well-being, this study adopted a pragmatic hybrid methodology that integrates both RfD and RTD, as outlined by Lenzholzer et al. (2013) [39,40]. This approach enabled us to develop targeted, context-sensitive interventions grounded in empirical evidence while also using the design process as a method of inquiry [39,40].

The RfD component used quantitative and qualitative survey data to identify spatial barriers, user needs, and environmental deficiencies across nine public spaces in Beirut. These findings guided the formulation of design objectives and priorities.

The RTD component then explored and generated new knowledge through the act of designing. A series of research questions guided the design process, addressing key issues identified in the empirical phase [39,40]. Ultimately, we identified and refined the best-performing design propositions [40]. Specifically, the RTD process was guided by the following research questions: (1) how can design interventions address the specific barriers to accessibility identified in the survey? (2) How can incorporating natural elements improve the functionality and overall user satisfaction of public spaces? (3) How can the availability, condition, and maintenance of facilities in public spaces be improved through effective management strategies to better serve users’ needs? (4) How can design features reduce the effects of overcrowding in public spaces to improve comfort and space usability? (5) How can design interventions encourage diverse social interactions and physical activities in public spaces? (6) How do enhancements to public space quality factors affect the mental well-being and experience of users?

Based on these insights, the RTD process was initiated to experiment with design-based responses that tested how spatial interventions could address the identified deficiencies. The team presented users with a curated mood board of existing designs, including shaded play areas, a promenade flanked with trees, and a central gathering space, to stimulate discussion and gather feedback in public spaces. These elements were considered to enhance thermal comfort, encourage social interaction, and improve psychological well-being.

These interventions were designed to be climate-resilient, drawing on existing literature on landscape and urban design for health and well-being and climate adaptation [41,42], reducing environmental stressors and enhancing green space quality to ensure that public spaces actively promote mental well-being. While the interventions were informed by empirical data (RfD), the design process itself contributed to the generation of new, site-specific knowledge (RTD), resulting in integrated design solutions. This aligns with the pragmatic RTD model, where, as Lenzholzer et al. (2013, p. 125) note, “the final product might be a ‘fully’ integrated design—an example of accumulated knowledge” [39].

Table 2 summarizes the transition from empirical findings to design strategies. The following subsections present the site-specific interventions developed through this approach, organized around key thematic categories: thermal comfort and shading, inclusive seating, sensory engagement, accessibility thresholds, and symbolic–functional layering.

Table 2.

Translation of empirical findings into design interventions (RfD to RTD).

Recognizing that green spaces are integral to the broader socio-ecological system, the study addressed human needs—such as accessibility, shade, and social inclusivity—to improve both site usability and environmental performance.

The research embodied in the final design is site-specific, developed with an in-depth understanding of how each location affects relevant performance criteria. While the designs were tailored to meet the specific needs of the identified sites, the knowledge gained from these interventions may be applicable to similar contexts in other urban environments, leading to broader replicable design knowledge. This approach ensured that the development of public spaces contributed to improved mental well-being while enhancing ecosystem services such as biodiversity, water management, and heat mitigation.

2.5. Data Analysis

We analyzed the collected data using a combination of parametric and non-parametric statistical techniques to examine variations in user satisfaction with public space quality and psychological well-being. Prior to the main analysis, they tested data normality using Q-Q plots to determine the appropriate statistical methods. To compare perceptions across the nine study sites, we conducted a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), followed by a Duncan post-hoc test to identify statistically significant differences and group the sites into homogeneous subsets. We used descriptive statistics to summarize overall trends, including frequency distributions and mean scores. To explore the relationship between perceived public space quality and psychological well-being, we applied Spearman’s rank correlation to assess the strength and direction of associations between key variables. We also performed factor analysis to identify underlying dimensions influencing perceptions of public space quality. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted in R (version 4.1.0) using the factoextra and ade4 packages to extract latent constructs related to spatial and psychological factors. We used IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25) for statistical analyses, setting significance at p < 0.05.

In parallel with the quantitative survey analysis, we analyzed the qualitative results from the RTD phase thematically to derive design recommendations. This thematic analysis focused on identifying key spatial, environmental, and management-related factors that influenced the perceived quality and usability of public green spaces. These themes were then used to inform the translation of empirical findings into site-responsive design interventions.

3. Results

3.1. Quality of Public Open Spaces in Beirut City

To compare the mean satisfaction levels across the nine locations, we performed a one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test. Table 3 presents the one-way ANOVA results, alongside the effects of post-hoc analysis effects conducted after ANOVA. Means marked with different small letters indicate significant differences.

Table 3.

Means of satisfaction level of quality of public open space during the study (the same letters after means indicate where there is no difference between means).

We identified significant differences between sites (p-value = 0.000, p < 0.05), indicating varied levels of people’s satisfaction with the quality of each public space. The study highlighted diverse and location-specific barriers faced during the use of public spaces in Beirut. These barriers included discomfort caused by pebble-paved paths, a lack of facilities for children, and inconvenient entrances for individuals with special needs. Upon analyzing public spaces in Beirut, urban parks showed the highest satisfaction levels regarding space quality, with slight differences among them. Satisfaction varied across sites, with Saanayeh Park (site 2) perceived as the best in terms of quality. Conversely, site 8, Martyr’s Square, exhibited the lowest satisfaction levels and emerged as the lowest-quality site in the study. Functionality-related issues such as uneven walking paths, variable vegetation conditions, limited facilities, and inconsistent lighting, contributed to these disparities. Safety challenges also pose significant concerns for public spaces in Beirut. These include inadequate lighting, risks when crossing roads amidst traffic hazards, and an overall unstable security situation. Accessibility challenges vary across public spaces in Beirut, influenced by factors such as closure times. Limited transportation options further emerge as a potential concern, affecting individuals’ ability to access public open spaces.

The study assessed the quality of public open spaces by exploring various interconnected factors. It evaluated accessibility by examining access timing, transportation options, and economic barriers. Activity and social interaction were measured through questions about socializing, physical activities, and exercise opportunities within the space, reflecting how well the space fosters social inclusivity. The assessment of management focused on safety, cleanliness, attractiveness, and suitability for intended purposes, indicating the space’s maintenance and appeal. Intensity of visit was measured by analyzing the level of crowdedness and usage frequency. The natural environment factor was evaluated based on the presence and quality of vegetation, while facilities were assessed through amenities like benches, play areas, water features, lighting, and walking paths. Each factor was addressed through targeted questions to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the public open spaces.

We employed descriptive statistics to analyze the key factors influencing public space quality, calculating mean satisfaction values and standard deviations (SDs), as presented in Table S2. Among the evaluated dimensions, users reported the highest satisfaction with natural elements, such as trees and shrubs, with a mean score of 3.7. In contrast, accessibility received the lowest satisfaction score (mean = 2.7), reflecting significant barriers and indicating comparatively lower user satisfaction than other factors.

Factor analysis identified six dimensions of public space quality. The highest loading was observed for the facility factor (0.74), followed by management (0.71) and accessibility (0.60). The activity factor had the lowest loading (0.37), indicating a weaker influence on perceived quality. Full results are presented in Table S3 (Supplementary Materials).

These findings from the RfD phase provided empirical grounding for designing hypotheses related to shade provision, surface treatment, accessibility enhancements, and inclusive programming, which the researchers explored in the RTD phase.

3.2. Psychological Indices

We conducted a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to examine psychological indices across various public spaces in Beirut and found no significant differences among the three studied types. All psychological measures assessed, including PANAS positive [F(2294) = 0.267, p = 0.766], PANAS negative [F(2294) = 0.416, p = 0.660], and SVS [F(2294) = 0.645, p = 0.526], had p-values exceeding 0.05, suggesting uniform emotional experiences across the different spaces.

However, when assessing both the PANAS and SVS scales as psychological indices at each site, we found statistically significant differences between them, despite some similarities (Table 4). While certain sites contributed more to psychological well-being, a comparison of mean values revealed that Site 8 (Martyr’s Square) had the least impact. In contrast, Site 7 (Samir Kassir Square) showed the highest positive effect, demonstrating the greatest mental improvement among the surveyed sites. This outcome is attributed to its location near a working area, where workers perceive it as a space to relax during their breaks.

Table 4.

Means of psychological measures during the study (the same letters after means indicate where there is no difference between means).

3.2.1. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

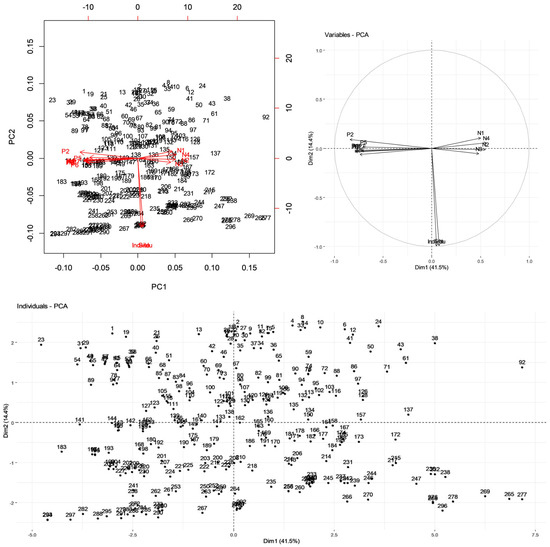

Figure 3 presents a biplot Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the PANAS scale and shows that urban parks, specifically Horsh Beirut and Gebran Khalil Gebran Park, exhibited a higher prevalence of individuals expressing negative feelings, potentially resulting from safety and accessibility concerns, as well as the absence of certain amenities. In contrast, Saanayeh Park records a larger share of visitors who report positive feelings, which could be attributed to effective management and better facilities. Along the promenades, Zeitouna Bay and Raouché receive more negative reports, whereas Ain el Mreisse shows more positive ones, probably because its easy sea access enhances the experience. In city squares, Samir Kassir Square and Nejmeh Square generate more positive experience, credited to the high-quality materials in the space providing appealing aesthetics, whereas Martyr’s Square displayed signs of neglect, leading to a higher prevalence of individuals experiencing negative feelings.

Figure 3.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) bi-plot representing positive and negative affect schedule scores.

3.2.2. Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS)

The one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s Multiple Range Test results for the SVS mean comparison, shown in Table 5, indicate that sites within urban park and square types significantly impact individuals’ well-being, especially their feelings of aliveness, vitality, and energy. Squares particularly stand out for fostering alertness and an energized sense of being. On the other hand, promenade sites tend to receive lower ratings in these aspects. Overall, the findings suggest that each type of urban space uniquely influences well-being, with squares notably fostering alertness and energy and urban parks contributing to a general sense of anticipation for each new day and feeling alive.

Table 5.

Means of psychological measures of SVS during the study (the same letters after means indicate where there is no difference between means).

By identifying which sites contributed more significantly to positive affect and vitality, these results shaped RTD priorities, emphasizing design strategies that could amplify positive emotional responses through spatial quality, social functionality, and sensory stimuli.

3.3. Urban Public Spaces and Mental Well-Being

The descriptive statistics obtained through SPSS, presented in Table 6, reveal that participants generally reported high levels of positive affect (M = 4.36) and subjective vitality (M = 5.23) when utilizing public open spaces, as measured by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule and Subjective Vitality Scale, respectively. Conversely, respondents reported a lower level of negative affect (M = 2.68) in these spaces, suggesting an overall positive emotional experience. The mean values, interpreted against the Likert scale (five-point Likert scale), indicate that most participants experienced positive emotions ranging from “quite a bit” to “extremely”, while negative emotions were reported as “very slightly” or “a little”. The SVS mean score of 5.23 falls above the midpoint of the seven-point Likert scale, indicating that, on average, participants felt subjectively vital to a high degree, with responses ranging from “Very true” to “Extremely true”. These findings suggest that public open spaces not only contribute to positive affect but also foster a sense of subjective vitality, highlighting the potential to enhance mental well-being, minimize negative emotions, and promote vitality for the surveyed individuals.

Table 6.

Means and SD of psychological measures during the study (for PANAS and SVS scales).

The positive impact of urban public spaces on mental well-being was found to be linked to the quality of each studied site. An analysis of the data revealed a moderate positive association (Spearman’s rho = 0.30) between public space quality and mental well-being. (Table 7). This finding implies that the environment in which people engage, particularly public open spaces, plays a substantial role in shaping their mental health.

Table 7.

The correlation test result between quality of public open spaces and mental (psychological) well-being.

The positive direction of the relationship indicates that as satisfaction with public open spaces increases, so does the mental well-being of individuals accessing those spaces.

The moderate positive correlation between perceived public space quality and psychological well-being validates the design goal of enhancing quality factors—such as shade, comfort, safety, and vegetation—as mechanisms to support mental resilience through spatial interventions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Public Space Quality and User Satisfaction in Beirut

This study examined the quality of public open spaces in Beirut, identifying key factors that influence user satisfaction and mental well-being. An analysis of nine urban locations revealed significant variability in space quality, shaped by location-specific barriers and a complex interplay of accessibility, facilities, management, and natural elements.

Factor analysis showed that facility quality, management, and accessibility were the most influential dimensions, while activity had the lowest loading (see Table S3). These findings suggest that in Beirut’s urban context, functional and infrastructural qualities—including well-designed landscapes, safety, and amenities—are more critical to user satisfaction than recreational or social activities [43].

A previous study conducted in Indonesia found that ‘activity’ was the most significant factor influencing public open space quality, while ‘accessibility’ was considered insignificant [44]. In that context, public spaces often function as vibrant hubs for social and recreational activity, and accessibility is largely understood in terms of vehicle access, primarily motorcycles. This interpretation contrasts with international planning principles, which emphasize walkability and pedestrian connectivity [45].

4.2. The Role of Context and Design in Shaping Public Space Benefits

This study reveals a greater diversity of user experiences, highlighting the significant role that local context, as shown in previous studies [46], plays in shaping public space satisfaction. Quality public spaces are essential for building sustainable and resilient cities [47], because they significantly influence individual and community well-being [48]. The findings confirm prior research showing that high-quality urban spaces are not merely defined by aesthetics but by their ability to support mental health, social interaction, and inclusive use [47]. Key dimensions such as accessibility, walkability, inclusivity [47], comfort, safety, and cleanliness must be evaluated to ensure public spaces meet the diverse needs of users [48]. This not only enhances the functionality and appeal of urban spaces but also strengthens their role in fostering emotional restoration [49], social cohesion [50], and overall quality of life [48].

With all the challenges facing Beirut and their impact on residents’ mental health, many people seek public open spaces as places to relax and escape [43]. Amidst the hustle of life and in line with efforts to address barriers to public space use and in order to develop strategies that cope with sustainability and resiliency of the space, this study demonstrates that well-designed and well-maintained public spaces can enhance mental well-being, reduce negative emotions, and promote a sense of vitality. Notably, the benefits of high-quality public spaces were evident regardless of their size. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2021), in a study conducted in Zhuhai, China, found a strong positive correlation between the quality of public open spaces (POSs) and residents’ mental health, independent of the spaces’ size or accessibility [51]. These findings highlight the importance of adopting quality-oriented design approaches—such as incorporating activity facilities and improving environmental quality—especially in the context of urban renewal and limited land availability. In such settings, expanding green areas may not be feasible, making it even more critical to shift away from traditional planning indicators (e.g., green space ratio or park area per capita) toward a greater emphasis on the quality of public open spaces [51].

4.3. Site-Specific Insights and Design Implications

Building on the study’s findings, this section explores how different types of public open spaces in Beirut perform in terms of quality and mental well-being and how targeted design interventions can address identified deficiencies.

Among the three urban parks analyzed, Saanayeh Park emerged as the highest-quality site. As Beirut’s oldest public park, it underwent a major renovation in 2014, funded and maintained by the Azadea Foundation [52]. These improvements—such as enhanced landscaping, seating, and accessibility—contributed to consistently high user satisfaction across multiple quality dimensions.

In contrast, Horsh Beirut and Gebran Khalil Gebran Park received the lowest scores among urban parks. Despite sharing similar ratings, Gebran Khalil Gebran Park was selected for intervention due to specific functional deficiencies. While the park holds aesthetic and memorial value as a tribute to the poet, it lacks essential features—particularly designated play areas—that support family use and recreational engagement. Prior studies such as Jiménez [53] and others [54,55,56] emphasize the importance of accessible, multifunctional spaces in encouraging family presence and supporting child development. The park’s current state reflects a disconnect between its symbolic value and its practical usability. Addressing this gap through quality-oriented design [51,57,58] will improve not only its functionality but also enhance urban well-being and community engagement.

Among the promenades, Zeitouna Bay was rated most favorably, offering scenic views and well-maintained infrastructure. In contrast, Ain El-Mreisseh ranked lowest due to poor design and limited environmental quality. Supported by previous studies, the design vision revolves around creating an inclusive urban public space that fosters and enhances people’s mental well-being by incorporating design elements like green spaces and walkability [59].

Ain El-Mreisse lacks proper design, functionality, and space quality. Although people use it for relaxation and physical activity, it is missing the key environmental [60] and structural [47] elements needed for a health-promoting public space. The absence of designated lanes for pedestrians and cyclists creates shared paths, increasing collision risks and compromising safety. Researchers observed similar issues on New York’s Brooklyn Bridge, where inadequate lane separation increased user conflicts and safety concerns [61]. Likewise, Mastora et al. (2023) observed, in Thessaloniki, that shared spaces without clear separation rely on mutual respect, often leading to conflicts and perceived safety issues [62].

Moreover, although the presence of the water-related settings has the potential to contribute to relaxation and emotional restoration—as supported by the Stress Reduction Theory [23], which highlights the calming effects of natural features like water—this benefit is not fully realized because of the space’s poor landscape integration. Vegetation is nearly absent, limiting the site’s capacity to offer shade, visual relief, or biodiversity-related benefits, all of which are essential components for enhancing mental well-being [63]. The lack of greenery also disconnects the site from qualities commonly associated with restorative environments, such as those emphasized in Attention Restoration Theory, which identifies natural settings as restoring directed attention and reducing mental fatigue [22], facilitating stress recovery [23], or both.

Among the three sites analyzed, Martyrs’ Square emerged as the least favorable, exhibiting the lowest scores across all evaluation criteria. This evident lack of quality reflects not only the lack of fundamental characteristics associated with high-quality public spaces such as safety, functional amenities, and landscape aesthetic [64], but also a broader issue of underutilization and disconnection from contemporary urban needs [65]. These findings align with previous systematic review by Kabisch et al. (2015), which indicates that urban spaces with deficiencies in fundamental qualities such as minimal vegetation, limited accessibility, and a lack of social infrastructure tend to perform poorly in both perceived and actual usability [65]. Participants’ responses and site observations suggested that users felt neither comfortable nor attracted to stay or utilize the space. This supports prior findings that comfort, greenery, and sense of enclosure are strongly linked to prolonged use and perceived safety, which encourage more frequent and extended visits to urban green spaces [66].

As urban design trends increasingly favor resilient landscapes, integrating principles of adaptability, sustainability [67], and human well-being has become a central priority [68]. Central to this approach is the designation of the entire area of Martyr’s square as car-free. Researches have empirically shown that car-free zones enhance both perceived and actual safety [69], improve air quality [70], reduce noise pollution [71], and increase pedestrian activity [71]. These benefits collectively contribute to a more positive urban experience and improved mental well-being for users. By removing vehicular access, the site encourages walkability and fosters a secure and inclusive environment that supports active transportation. For example, a pedestrianization project in Iran significantly increased perceived safety and reduced traffic-related emissions [69]. A study conducted in Barcelona, Spain, examined the implementation of “Superblocks,” a pedestrian-friendly approach, designed to reduce vehicle traffic and enhance public spaces within the city. The project resulted in an 8% reduction in main pollutants as a result of these traffic restrictions and a 14% saving in travel time, which also contributed to better air quality [70].

4.4. Accessibility as a Barrier to Equitable Public Space Use

The study revealed that accessibility significantly hinders the use of public spaces in Beirut, receiving the lowest satisfaction scores among all factors. This finding is consistent with a widespread challenge observed globally, where accessibility to public spaces remains a key issue across urban environments. For example, a systematic review by Jabbar et al. (2022) underscores the vital role of urban green spaces in promoting human well-being, highlighting accessibility as a key determinant in maximizing their use and associated benefits [72]. Factors such as distance, time, safety, and the suitability of green space amenities to the users’ needs and preferences often determine whether individuals can use these spaces effectively [73]. In many cases, lower-income groups and women experience these barriers more acutely, limiting their ability to engage with public spaces [73]. Furthermore, the design and distribution of green spaces play a critical role in either alleviating or exacerbating these barriers.

As discussed by Pelorosso et al., 2021, the design and spatial distribution of green spaces significantly influence accessibility for various users, with factors such as distance, safety, and amenities playing a crucial role [74]. Previous studies emphasize that the mere presence of green spaces is insufficient; their location, accessibility, and integration within urban layouts significantly affect how easily people can utilize them [75]. Studies indicate that poorly planned or inaccessible public spaces fail to meet the needs of diverse populations, contributing to low satisfaction levels [76]. Institutional barriers also significantly impact accessibility, as issues like conflicting interests, legal constraints, and the lack of funds often hinder the development and maintenance of accessible green spaces [77]. These barriers, including fencing and poor urban planning, further restrict public access to green spaces [45]. Various studies emphasize that creating well-designed, inclusive, and accessible spaces is essential to improving their use and ensuring equity across urban populations [45].

4.5. Linking Public Space Quality to Mental Well-Being

The study found a moderate positive correlation (0.30) between the quality of urban public spaces and mental well-being, suggesting that higher-quality public spaces are linked to improved mental health outcomes. This finding builds on previous research highlighting the significant role of public open space quality in reducing psychological distress among residents [31,78,79]. However, the moderate strength of the correlation may partly originate from the presence of low-quality sites in the study, which could have affected participants’ perceptions and experiences of these spaces.

While the quality of the public space, including factors such as cleanliness, safety, accessibility, and amenities, is crucial for enhancing mental well-being, it is not the sole determinant. Other factors also influence residents’ mental wellbeing. In contexts like Lebanon, additional socio-political and economic conditions play a significant role.

Lebanon has experienced prolonged political instability, economic crises, and social tensions, all of which deeply influence residents’ mental wellbeing by creating anxiety and depression [80]. These issues also affect how public spaces are used and perceived. For example, concerns about personal safety, social fragmentation, and limited public investment in infrastructure can overshadow the physical quality of the space itself [81]. These factors affect not only the maintenance and development of public spaces but also how welcoming or accessible they feel to different groups, exacerbating the problem [81].

The findings from the psychological measures demonstrate that public open spaces in Beirut contribute positively to users’ mental well-being. Users showed high scores for positive affect (M = 4.36) and subjective vitality (M = 5.23), alongside a relatively low score for negative affect (M = 2.68). These outcomes align with growing global evidence around the access to nature and its link to supporting mental health. In particular, White et al. (2019) [82] provide compelling research findings, quantifying a minimum of two hours per week spent in natural environments (whether through long weekend walks far from home or short, regular walks in urban parks, regardless of which activity took place) as a critical threshold for experiencing significantly higher levels of self-reported health and well-being.

The positive emotional responses experienced by the study participants while engaging with public spaces align with previous research highlighting the mental health benefits of urban green spaces [83]. Specifically, studies have shown that exposure to nature and opportunities for physical and social activities in these environments improve mood, vitality, and psychological well-being [84,85,86,87,88,89].

Beute et al. (2023) [30] underscore the mental health benefits of green spaces but also highlight a persistent challenge: current evidence does not clearly identify which types or features of green spaces offer the most benefits. This study contributes by systematically assessing psychological responses across different urban public space types in Beirut using uniform survey tools. The absence of significant differences in mental well-being measures across these spaces suggests that, at least locally, the overall availability and use of green or open spaces may be more critical for mental wellbeing than the specific characteristics of each space [90]. While this indicates a potential universal benefit from access to nature, it also emphasizes the need for further research with standardized methodologies to examine the effects of specific green space attributes on mental wellbeing and health outcomes. This is especially important since current research relies mostly on indirect comparisons between different types and features of green spaces [30].

4.6. Design Recommendations

Based on survey results and identified barriers in Beirut’s public open spaces, the following design recommendations aim to improve the quality and accessibility of urban green spaces, fostering mental well-being, environmental resilience, and long-term sustainability. These design interventions were developed using an RTD framework methodology, which enabled an iterative process of creating and refining solutions grounded in empirical survey data and detailed site observations. This approach allowed for the creation of design solutions that are not only contextually relevant but also tailored to enhance the mental well-being of users. The recommendations address key themes of accessibility, shade provision, sensory engagement, environmental resilience, and community interaction. The thematic analysis of the interventions highlights the importance of integrating these elements to create environments conducive to positive mental health outcomes.

The RTD methodology ensured that each intervention was tested and refined within actual site contexts, ensuring a practical impact on users’ experience of space. Table 8 summarizes the key design recommendations under each theme, alongside the specific interventions implemented and their anticipated effects.

Table 8.

Design recommendations based on thematic analysis of interventions.

To illustrate these interventions, Figures S1–S7 in the Supplementary Materials present design plans and vegetation strategies across the studied sites, with Table S4 providing a comparative overview of the three urban interventions based on site characteristics, design strategy, and alignment with UN-Habitat (2018) [35] and RfD/RTD frameworks. For example, Figure S1 outlines the proposed redesign of Gebran Khalil Gebran Park, balancing its memorial identity with functional improvements. This intervention seeks to balance the park’s cultural heritage with the need for functional improvements. It introduces a dedicated children’s playground, while preserving the memorial identity of the park, which honors the renowned Lebanese author Gebran Khalil Gebran. The design applied inspired and taken from the playground designs implemented in Gravesend Park in Brooklyn, reflecting Gebran’s themes of nature and wisdom, fostering an environment that supports both physical activity and mental development. The playground is strategically positioned at the park’s center, replacing an area of deteriorated grass to create a dynamic space for engagement and interaction. In addition to the playground, the design recommends replacing damaged benches throughout the park to enhance seating provisions that encourages social interaction and prolonged engagement, both vital for positive mental health outcomes.

Recognizing the therapeutic benefits of water features in public spaces [37], the design incorporates revitalizing the park’s existing water feature through regular maintenance and effective management. This intervention enhances the aesthetic appeal of the park but also supports users’ psychological well-being by offering a calming, reflective environment. Further interventions include the enhancement of lighting to improve safety and aesthetic quality, ensuring that the park remains inviting and functional during evening hours. The design also addresses accessibility by proposing modifications to the park’s entrance, making it fully accessible for people with disabilities, thus promoting inclusivity and equal access for all visitors. Introducing new vegetation is a key component of the proposed redesign. It complements the existing plant life to enrich the park’s overall ambiance, in line with previous research highlighting the stress-reducing and well-being-promoting effects of greenery in urban parks and the importance of incorporating plants in park environments to reduce stress and promote mental well-being [91]. Figures S2 and S3 provide a detailed overview of the vegetation strategy, which focus on increasing tree density by introducing species such as Quercus ilex and Tabebuia rosea. This approach creates a more varied and resilient environment with seasonal changes. To further enhance the sensory experience, the design includes aromatic shrubs, including lavender. Previous research has demonstrated that aromatic plants, particularly lavender, can significantly reduce anxiety and improve mood [92], thereby contributing to the mental well-being of park users. The design recommends planting between 5 and 20 scented flowers or shrubs per 100 square meters, strategically distributed to maximize sensory stimulation throughout the park’s 5572 square meters.

These interventions aim to create a sensory-rich, inclusive public space that promotes mental well-being through both physical design and the introduction of elements that support users’ psychological health. Moreover, the design ensures natural surveillance, a key factor in providing a sense of security and fostering a safe, welcoming environment. These comprehensive improvements will enhance the park’s overall quality by addressing both physical and psychological barriers to effective use.

The proposed interventions vary in scope. Some areas require relatively simple improvements, while others necessitate more substantial changes. The overarching goal is to create a public space that not only meets the physical needs of the community but also actively contributes to improving mental health outcomes, accessibility, and the overall quality of life for Beirut’s residents.

4.7. Study Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between urban green spaces and mental well-being in Beirut, several limitations require acknowledgement.

First, although the sample size was adequate for achieving statistical robustness, it may not fully capture Beirut’s diverse population. With an estimated 2023 population of 2,421,354, a 10% margin of error (MOE) required a minimum sample size of 96 responses. To improve the statistical reliability, we conducted 297 surveys, administering 33 at each of the nine selected sites. However, the sample may not fully represent the broader population, particularly marginalized groups with limited access to or use of public spaces, potentially introducing bias into the results.

Second, the data-collection period (July–August 2023) aligned with Lebanon’s summer vacation season, when public parks experience high visitation due to school holidays, warm weather, and extended daylight hours. This period may have influenced both the frequency and patterns of public space usage, as well as user perceptions, given seasonal behavioral changes such as heat-related avoidance and increased tourism. We deliberately selected this period to capture usage during the peak activity phase, offering timely insights and solutions during a relatively stable socio-political period. However, the findings may not reflect user perceptions or behaviors during other times of the year, particularly colder or rainier months when park usage tends to decline and weather conditions may affect mood and emotional responses. Additionally, Lebanon’s fluctuating sociopolitical conditions significantly shape and impact public space use and research site accessibility, limiting the generalizability of these findings to more stable or different timeframes. Future research should adopt a multi-seasonal and multi-contextual approach to better capture the variability in usage patterns and emotional perceptions throughout the year.

In terms of design recommendations, the proposed interventions, while based on survey data, have not yet been tested through physical implementation or real-world observation. We have not validated the designs using rendering or virtual reality (VR) simulations, which could provide a more accurate representation of how these changes might improve mental well-being. Future studies could benefit from testing the designs through such advanced technologies to better predict their impacts.

Furthermore, the climate resilience of the proposed designs has not been evaluated. While the interventions intended to improve the quality of public spaces and mental well-being, they have not been assessed using modeling approaches to determine their effectiveness in addressing climate challenges, such as heat stress or water management. Future research should explore how these design solutions can improve ecosystem services and contribute to long-term climate resilience.

Another limitation concerns the inclusion of lawns in the proposed designs, which, although culturally accepted in the Middle East, they may not be the most climate-resilient option. They require regular maintenance, irrigation, and resources that may prove unsustainable in the face of climate change. While they may be valued for their aesthetic appeal and cultural significance, alternative, more water-efficient and low-maintenance solutions should be considered to enhance the sustainability of these public spaces.

Finally, the study focused on cross-sectional data, meaning that the long-term impacts of the proposed interventions on mental well-being have not been evaluated. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the sustained effects of these design changes over time.

5. Conclusions

This study, the first to combine a cross-sectional survey with a pragmatic RfD and RTD framework in Beirut’s public green spaces, addresses the urgent need for restorative urban environments amidst Lebanon’s ongoing socio-economic crisis. This methodological integration uniquely positions the study to not only understand user experiences but to actively generate actionable design solutions rooted in empirical evidence. With 70% of the population struggling to meet basic expenses and healthcare costs rising sharply, the scarcity of accessible, high-quality public spaces has become a pressing public health concern.

Beirut’s urban landscape, characterized by widespread poverty and a severe shortage of green space per capita, presents significant challenges to mental well-being. Through a mixed-methods approach, the study quantified the relationship between public space quality and psychological well-being using validated instruments (PANAS and SVS) and spatial satisfaction metrics. The findings revealed a moderate positive association between well-maintained, accessible, naturally enriched public spaces and enhanced mental well-being and vitality (Spearman’s rho = 0.30), underscoring the critical role of spatial quality in urban mental health outcomes within crisis-affected settings.

Key barriers to public space use included safety concerns, poor accessibility, and inadequate facilities. Sites such as Horsh Beirut and Gebran Khalil Gebran Park were negatively impacted by these issues, while Saanayeh Park emerged as a positive example of well-managed space. Promenades like Zeitouna Bay and Raouché underperformed, whereas Ain el Mreisse, Samir Kassir Square, and Nejmeh Square received more favorable perceptions. Natural elements such as trees and shrubs were consistently rated highly, underscoring their restorative value.

This study contributes to the emerging body of research linking spatial quality to mental health by identifying specific characteristics that influence psychological outcomes in a crisis-affected urban context. Theoretically, it expands the applicability of environmental psychology and urban design integration to the Global South. Practically, it demonstrates how user-generated data can inform low-cost, scalable design interventions through RTD methods, providing a replicable research-to-design model to guide resilient urban regeneration efforts in similar vulnerable cities.

By integrating RfD and RTD, the study showcases how empirical data collection and design inquiry can work in tandem to generate context-specific knowledge and actionable spatial strategies. Supplementary design outputs further illustrate how these insights translate into tangible interventions that promote mental well-being, inclusivity, and climate resilience. This approach exemplifies how research and design co-evolve to create adaptive solutions tailored to complex socio-environmental challenges.

Given Lebanon’s ongoing crises, investing in the improvement and equitable distribution of green spaces should be considered a national priority. These interventions offer a cost-effective, scalable strategy to support public health, foster social cohesion, and build urban resilience. Local authorities, urban planners, and international development organizations can use these findings to guide the design, funding, and implementation of green infrastructure projects that prioritize mental well-being and social equity.

Future research should explore the long-term impacts of such interventions, test the proposed design solutions in practice, and examine their broader ecological and social benefits. Moreover, an iterative evaluation of RTD interventions through longitudinal and participatory methods will be crucial to refine and optimize their effectiveness. By advancing a replicable, evidence-based framework for evaluating and enhancing urban green spaces, this study contributes to developing healthier, more livable cities—both in Lebanon and in similarly challenged urban contexts worldwide.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14081558/s1, A list of spatial characteristics of selected public spaces in Beirut is provided in Table S1, descriptive statistics of public open space quality factors is shown in Table S2, factor analysis for the public open space’s factors in Table S3, Survey questions, Figures S1–S7 shows proposed design plan and vegetation plan for each chosen site (Gebran Khalil Gebran Garden, Ain El-Mreisse Promenade, and Martyr’s Square), Table S4 proposes a comparative summary of the three urban interventions implemented in Gebran Khalil Gebran Garden, Ain El-Mreisse Promenade, and Martyr’s Square, based on site characteristics, design strategy, and alignment with UN-Habitat (2018) guidelines and RfD/RTD research frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R., G.K. and N.Z.; methodology, M.R. and A.R.; software, G.K.; validation, M.R., G.K. and F.A.; formal analysis, M.R. and F.A.; investigation, M.R. and F.A.; data curation, M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R., G.K., N.Z., V.D. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, M.R., G.K., F.A., N.Z., V.D. and A.R.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, G.K., F.A. and N.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of the Lebanese University. All participants were informed about the purpose and procedures of the study and provided verbal informed consent prior to participation.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and constructive suggestions, which greatly improved the quality and clarity of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ART | Attention Restoration Theory |

| PANAS | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule |

| SVS | Subjective Vitality Scale |

| RTD | Research through Design |

| SRT | Stress Recovery Theory |

| RfD | Research for Design |

References

- Janeczko, E.; Bielinis, E.; Wójcik, R.; Woźnicka, M.; Kedziora, W.; Lukowski, A.; Elsadek, M.; Szyc, K.; Janeczko, K. When Urban Environment Is Restorative: The Effect of Walking in Suburbs and Forests on Psychological and Physiological Relaxation of Young Polish Adults. Forests 2020, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-92-1-004314-4. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Urbanization and Health. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mona, M.; Ayad, H.M.; Raslan, R. Investigating the Effect of Urban Built Environment on Mental Health (Depression): Case Study of Damietta City, Egypt. BAU J.-Health Wellbeing 2018, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Argabright, S.T.; Tran, K.T.; Visoki, E.; DiDomenico, G.E.; Moore, T.M.; Barzilay, R. COVID-19-Related Financial Strain and Adolescent Mental Health. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2022, 16, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubayashi, T.; Ishikawa, Y.; Ueda, M. Economic Crisis and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 306, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einav, M.; Margalit, M. Loneliness before and after COVID-19: Sense of Coherence and Hope as Coping Mechanisms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Cloonan, S.A.; Taylor, E.C.; Dailey, N.S. Loneliness: A Signature Mental Health Concern in the Era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelgrims, I.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Guyot, M.; Keune, H.; Nawrot, T.S.; Remmen, R.; Saenen, N.D.; Trabelsi, S.; Thomas, I.; Aerts, R.; et al. Association between Urban Environment and Mental Health in Brussels, Belgium. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, N.; Polemiti, E.; Garcia-Mondragon, L.; Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Lett, T.; Yu, L.; Nöthen, M.M.; Feng, J.; et al. Effects of Urban Living Environments on Mental Health in Adults. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, N.; Polemiti, E.; Mondragon, L.G.; Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Lett, T.; Yu, L.; Noethen, M.; Yu, C.; et al. Environmental Profiles of Urban Living Relate to Regional Brain Volumes and Symptom Groups of Mental Illness through Distinct Genetic Pathways. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolouki, A. Neurobiological Effects of Urban Built and Natural Environment on Mental Health: Systematic Review. Rev. Environ. Health 2023, 38, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anakwenze, U.; Zuberi, D. Mental Health and Poverty in the Inner City. Health Soc. Work 2013, 38, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridley, M.; Rao, G.; Schilbach, F.; Patel, V. Poverty, Depression, and Anxiety: Causal Evidence and Mechanisms. Science 2020, 370, 6522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, G.; Evans, S.; Knight, J.; Shackell, A.; Tisdall, R.; Westley, M. Public Health and Landscape: Creating Healthy Places. Landscape Institute 2013. Available online: https://landscapewpstorage01.blob.core.windows.net/www-landscapeinstitute-org/2013/11/Public-Health-and-Landscape_FINAL_single-page.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Barnes, M.R.; Donahue, M.L.; Keeler, B.L.; Shorb, C.M.; Mohtadi, T.Z.; Shelby, L.J. Characterizing Nature and Participant Experience in Studies of Nature Exposure for Positive Mental Health: An Integrative Review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Cui, H.; Ma, Y.; Gao, N.; Li, X.; Meng, X.; Lin, H.; Abudou, H.; Guo, L.; et al. Green Space Exposure on Depression and Anxiety Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, E.; Spano, G.; Lopez, A.; Tinella, L.; Clemente, C.; Elia, G.; Dadvand, P.; Sanesi, G.; Bosco, A.; Caffò, A.O. Long-Term Exposure to Greenspace and Cognitive Function during the Lifespan: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A. Urban Green Spaces and Healthy Living: A Landscape Architecture Perspective. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A. Renaturing for Urban Wellbeing: A Socioecological Perspective on Green Space Quality, Accessibility, and Inclusivity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Sanayeh, E.; El Chamieh, C. The Fragile Healthcare System in Lebanon: Sounding the Alarm about Its Possible Collapse. Health Econ. Rev. 2023, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeineddine, A. Int’l Report Ranks Beirut’s Quality of Life Among the ‘Worst’ in the World. Asharq Al-Awsat 2023, January 7. Available online: https://english.aawsat.com/home/article/4085101/int%E2%80%99l-report-ranks-beirut%E2%80%99s-quality-life-among-%E2%80%98worst%E2%80%99-world (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Choueiri, F.I.; Abi Haidar, J.; Moukarzel, M. 80% of Lebanon’s Population Was Below the Poverty Line in 2021 as per HRW. Credit Libanais 2023, March 27. Available online: https://economics.creditlibanais.com/Article/211558#en (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Obeid, S.; Lahoud, N.; Haddad, C.; Sacre, H.; Akel, M.; Fares, K.; Salameh, P.; Hallit, S. Factors Associated with Depression among the Lebanese Population: Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020, 56, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haigney, M. Mental Health in Lebanon. Anera 2022, August 17. Available online: https://www.anera.org/blog/mental-health-in-lebanon/ (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Nazzal, M.; Chinder, S. Lebanon Cities’ Public Spaces. JPS 2018, 3, 119–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beute, F.; Marselle, M.R.; Olszewska-Guizzo, A.; Andreucci, M.B.; Lammel, A.; Davies, Z.G.; Glanville, J.; Keune, H.; O’Brien, L.; Remmen, R.; et al. How Do Different Types and Characteristics of Green Space Impact Mental Health? A Scoping Review. People Nat. 2023, 5, 1839–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Marini, S.; Mauro, M.; Maietta Latessa, P.; Grigoletto, A.; Toselli, S. Associations Between Urban Green Space Quality and Mental Wellbeing: Systematic Review. Land 2025, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.I.; Behlen, M.; Henriques, A.; Severo, M.; Santos, C.J.; Barros, H. Exposure to Green and Blue Spaces and Depression among Older Adults from the EPIPorto Cohort: Examining Environmental, Social, and Behavioral Mediators and Varied Space Types. Cities Health 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. Research Methods for Environmental Psychology; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-118-79533-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, A.; Bruns, D.; Tobi, H.; Bell, S. Research in Landscape Architecture–Methods and Methodology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-02092-4. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. SDG Indicator 11.7.1 Training Module: Public Space. United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi 2018. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/07/indicator_11.7.1_training_module_public_space.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Tanur, J.M. Survey Research Methods in Environmental Psychology. In Advances in Environmental Psychology (Volume 5): Methods and Environmental Psychology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Czyżyk, K.; Korcz, N.; Woźnicka, M.; Bielinis, E. The Psychological Effects and Benefits of Using Green Spaces in the City: A Field Experiment with Young Polish Adults. Forests 2023, 14, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, T.L.; Aziz, N.A.A.; Yaakob, S.S.N. The Effects of Different Natural Environment Influences on Health and Psychological Well-Being of People: A Case Study in Selangor. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzholzer, S.; Duchhart, I.; Koh, J. “Research through Designing” in Landscape Architecture. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 113, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesão, J.; Lenzholzer, S. Research through Design in Urban and Landscape Design Practice. J. Urban Des. 2022, 27, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souter-Brown, G. Landscape and Urban Design for Health and Well-Being: Using Healing, Sensory and Therapeutic Gardens; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Graça, M.; Cruz, S.; Monteiro, A.; Neset, T.-S. Designing Urban Green Spaces for Climate Adaptation: A Critical Review of Research Outputs. Urban Clim. 2022, 42, 101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehab, A. Exploring the Attributes of Open Public Spaces in the Developing Cities. Archit. Plan. J. 2022, 28, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, A.D.; Zahrah, W. Community Perception on Public Open Space and Quality of Life in Medan, Indonesia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 153, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE); Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR). The Value of Urban Design; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 2001; 113p. [Google Scholar]

- Halawani, R. The Effects of Public Spaces on People’s Experiences and Satisfaction in Taif City: A Cross-Sectional Study. Land 2024, 13, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mela, A.; Vryzidis, I.; Varelidis, G.; Tsotsolas, N. Urban Space Quality Evaluation Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis-Based Framework; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mela, A.; Tousi, E.; Varelidis, G. Measuring Urban Space Quality: Development and Validation of a Short Questionnaire. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz-Pascual, K.; Aspuru, I.; Iraurgi, I.; Santander, A.; Eguiguren, J.L.; García, I. Going beyond Quietness: Determining the Emotionally Restorative Effect of Acoustic Environments in Urban Open Public Spaces. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinçer, M.; Akyüz, S.; Açık Etike, B. Quality Assessment of Public Spaces: The Case of Beyazit Square and Its Surroundings. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 1675–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, J.; Qin, B. Quantity or Quality? Exploring the Association between Public Open Space and Mental Health in Urban China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 213, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiruting |News| The Rene Mouawad Sanayeh Garden Reopens Its Gates. Available online: https://www.beiruting.com/news/2747/the-rene-mouawad-sanayeh-garden-reopens-its-gates (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- May, V. Family Life in Urban Public Spaces: Stretching the Boundaries of Sociological Attention. Families, Relationships and Societies. Fam. Relatsh. Soc. 2023, 12, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awada, H. Fostering Social Equity in Planning and Urban Design with Children. Topophilia 2024, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.C.; Thompson-Carr, A.; Lovelock, B. Parks and Families: Addressing Management Facilitators and Constraints to Outdoor Recreation Participation. Ann. Leis. Res. 2012, 15, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S. Reclaiming Spaces: Child Inclusive Urban Design. Cities Health 2019, 3, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fang, M.; Hu, J. The Associations between the Quantity and Quality of Urban Green Spaces and Health: Enlightenment from the Case of Hangzhou, China. Preprints 2024, 2024041183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Jabbour, N.; John, D.D.; Ahmad, A.M.; Furlan, R.; Al-Matwi, R.; Isiafan, R.J. The Impact of Urban Design on Mental Well-Being by Integrating Green Spaces in Doha City, Qatar. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsabila, S.; Navitas, P. Built Environment Design Features, Mental Health, and Well-Being for Inclusive Urban Design: An Extensive Literature Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1394, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaralioglu, I.; Kara, C. Sustainable Urban Design Approach for Public Spaces Using an Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP). Land 2025, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]