Abstract

Once confined to mourning and burial, urban cemeteries are now being reimagined as multifunctional public spaces integrated into everyday urban life. Responding to this evolving role, this study investigates how metropolitan cemeteries in Tokyo are used, perceived, and socially negotiated. Although institutional initiatives have promoted the integration of cemeteries into green infrastructure, empirical research on user behavior, perception, and willingness remains limited—particularly in East Asian contexts. To address this gap, the study combines unstructured user-generated data (Google Maps reviews and images) with structured questionnaire responses to examine behavioral patterns, emotional responses, perceived landscape elements, and behavioral intentions across both urban and suburban cemeteries. Findings reveal that non-commemorative uses—ranging from nature appreciation and cultural engagement to recreational walking—are common in urban cemeteries and are closely associated with positive sentiment and seasonal perception. Factor analysis identifies two dimensions of behavioral intention—active and passive engagement—and reveals group-level differences: commemorative visitors show greater inclination toward active engagement, whereas multi-purpose visitors tend toward passive forms. Urban cemeteries are more frequently associated with non-commemorative behaviors and higher willingness to engage than suburban sites. These results underscore the role of cultural norms, prior experience, and spatial typology in shaping cemetery use, and offer practical insights for managing cemeteries as inclusive and culturally meaningful components of the urban landscape.

1. Introduction

Once regarded solely as spaces for the dead, urban cemeteries are now being actively reimagined as part of the living city. In response to spatial constraints and evolving urban needs, these traditionally sacred and segregated landscapes are increasingly recognized for their potential to serve broader public functions. This shift has attracted growing scholarly and planning interest across diverse cultural and institutional contexts [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The multifunctionality of cemeteries has been discussed from various aspects, including the provision of ecological benefits [7,8,9,10,11], utilization as tourism resources [12,13], and accommodate recreational use [14,15,16,17]. In many cities, cemeteries are being incorporated into broader strategies for urban greening and open space planning [18].

However, this transformation is not without challenges. Resistance typically arises from two dimensions: from the perspective of the deceased, concerns center on how to define an appropriate degree of openness while preserving the dignity and tranquility of the burial environment [19,20,21]; from the perspective of the living, cemeteries often continue to carry connotations of death, taboo, and unease in certain cultural contexts, which raises questions about public acceptance and willingness to embrace them as everyday spaces [22,23,24,25].

While the multifunctional transformation of cemeteries has been increasingly discussed in Western contexts—particularly in Northern Europe, where cemetery landscapes have, to varying degrees, been integrated into everyday public life through a range of mindful recreational practices such as walking, jogging, or quiet appreciation of nature [6,21,26]—research from East Asia remains limited. In East Asia, where views on life and death and cultural backgrounds of land use differ, patterns of cemetery use and public acceptance may be informed by distinct socio-cultural and institutional dynamics. Burial spaces are frequently understood not merely as sites of individual remembrance, but as morally charged spaces anchored in ancestral obligations and sustained through ritualized practices of commemoration [27]. These cultural frameworks have historically shaped public perceptions of burial spaces, potentially limiting their integration into broader public space networks. Moreover, traditions of memorialization emphasize symbolic continuity and spatially embedded memory, which may conflict with modern planning ideals that prioritize functionality and public accessibility [28]. These structural dynamics offer a conceptual basis for understanding how multifunctional transformations are interpreted in East Asian contexts, where usage patterns may reflect culturally embedded norms and spatial practices. These differences are important not only for filling a geographical gap, but also for critically contextualizing and potentially revising existing theories of cemetery multifunctionality.

In Tokyo, a series of cemetery regeneration initiatives have been introduced since the early 2000s. Beginning with the regeneration proposal for Aoyama Cemetery [29] (Tokyo Metropolitan Park Council, 2002), and followed by strategic plans for Yanaka [30], Somei [31] and Zoshigaya [32] cemeteries, these policies seek to reposition cemeteries as hybrid public spaces that combine commemorative functions with ecological, cultural, and community value. As shown in Figure 1, the transformations in Tokyo’s public cemeteries—such as the coexistence of burial plots and play equipment in Yanaka Cemetery—demonstrate how these spaces are being redefined to accommodate both memorial and everyday uses. This ongoing institutional effort provides a compelling context for examining how urban cemeteries are being reimagined through planning and policy.

Figure 1.

Coexistence of commemorative, nature and recreational elements in Yanaka Cemetery, Tokyo.

Despite the emergence of institutional efforts to reframe cemeteries in Japan, empirical research on how these changes are perceived, experienced, and socially negotiated by the public remains sparse. Existing studies have primarily focused on administrative systems [33], planning policies [34], spatial transformation [35], or burial practices [36], with comparatively little attention given to users’ perspectives. While these policies actively promote the multifunctionality of cemeteries, there is limited understanding of how such initiatives translate into everyday engagement—both in terms of actual behavior and public intentions. This study addresses this policy gap by examining the actual and potential use of metropolitan public cemeteries in Tokyo. It integrates unstructured user-generated data—including online textual reviews and user-posted images—with structured questionnaire data, enabling a multifaceted analysis of behavioral patterns, spatial perceptions, and willingness to engage with cemetery spaces. Building on exploratory insights from the online review analysis, the questionnaire survey was designed to further examine these patterns and assess their broader relevance. This approach captures both observational and intentional dimensions of cemetery use, and helps to reduce single-source bias, yielding more robust and contextually grounded findings [37].

Specifically, this study aims to explore the following research questions:

- How are metropolitan public cemeteries currently used by visitors in Tokyo?

- What types of emotional responses and perceived landscape elements are associated with these cemetery visits?

- How are observed behaviors related to emotional responses and environmental perception?

- What are the levels and patterns of public willingness to engage in non-commemorative behaviors in cemetery spaces?

- How do patterns of use, perception, and behavioral intention vary between urban and suburban cemetery settings?

By focusing on cemetery users’ behaviors and perceptions, this study contributes to the theoretical understanding of cemetery multifunctionality from a user-centered perspective—an angle largely underexplored in previous research. In particular, it complements existing policy- and planning-oriented studies by empirically examining how non-commemorative activities, emotional experiences, and spatial perceptions unfold in actual use contexts. Furthermore, the findings offer practical insights for urban landscape planning by identifying patterns of engagement that may inform the development of inclusive and multifunctional cemetery spaces grounded in users’ experiences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

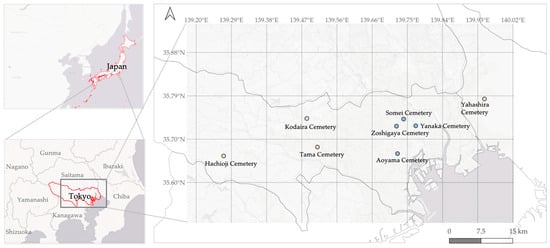

This study focuses on eight metropolitan public cemeteries in Tokyo, Japan—Yanaka, Aoyama, Somei, Zoshigaya, Tama, Kodaira, Hachioji, and Yahashira (Figure 2)—all of which are managed by the Tokyo Metropolitan Park Association. Among them, Yanaka, Aoyama, Somei, and Zoshigaya are situated within the central 23 wards of Tokyo and were established in the late 19th century, during the Meiji era. In contrast, Tama, Kodaira, Hachioji, and Yahashira are located in the suburban areas and were developed throughout the 20th century, reflecting a later phase in cemetery planning aligned with the spatial expansion of the city.

Figure 2.

Locations of the selected public cemeteries in Tokyo, Japan. Yahashira Cemetery, while situated outside the administrative limits of Tokyo, is included as a study site due to its administrative affiliation with the Tokyo Metropolitan Cemetery system.

Notably, Tama Cemetery, opened in 1923, was Japan’s first designated park cemetery, inspired by the design concepts of European forest cemeteries. It integrated commemorative functions with naturalistic landscapes, setting a precedent for subsequent suburban cemeteries such as Yahashira, Kodaira, and Hachioji, which were developed following a similar park-like model.

In 2002, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Construction issued a regeneration proposal for Aoyama Cemetery [29], which laid the foundation for a broader transformation of central Tokyo cemeteries. The document redefined urban cemeteries not merely as places for remembrance but as shared urban assets that preserve historical and cultural resources, provide valuable open space, and contribute to community identity. It emphasized the necessity to regenerate such cemeteries as hybrid spaces where memorial and public uses coexist. Building on this vision, similar regeneration strategies were formulated for Yanaka Cemetery in 2005 [30], Somei in 2012 [31], and Zoshigaya in 2021 [32], demonstrating a sustained metropolitan effort toward the multifunctional revitalization of cemeteries in Tokyo’s urban core. These cemeteries and their defining characteristics are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key attributes of selected metropolitan cemeteries in Tokyo.

Based on their geographic location and developmental history, this study categorizes Yanaka, Aoyama, Somei, and Zoshigaya cemeteries as Urban Cemeteries, and Tama, Kodaira, Hachioji, and Yahashira as Suburban Cemeteries. This classification provides a useful analytical framework for identifying spatial and policy-related differences where relevant. However, it is important to note that the primary aim of this research is to examine the collective transformation and multifunctionality of Tokyo’s metropolitan cemeteries. The urban-suburban distinction is employed only where necessary to highlight contextual contrasts or to interpret variation in visitor behavior and spatial usage across different cemetery environments.

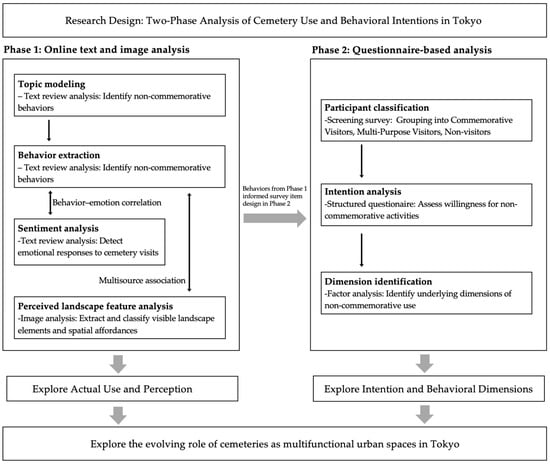

2.2. Research Design

This study adopts a two-phase mixed-methods design that integrates unstructured user-generated content with structured survey data to investigate the evolving role of public cemeteries in Tokyo (Figure 3). The first phase consists of a qualitative content analysis of Google Maps reviews and user-posted images, which captures the behavioral patterns, emotional responses, and perceived spatial elements among individuals who have visited cemeteries and chosen to publicly share their experiences. This approach offers rich, in situ insights into actual use [38] but is limited in scope; it is subject to bias as it excludes the perspectives of non-reviewers [39] and it cannot measure the latent acceptance and intentions underlying the observed behaviors.

Figure 3.

Research design framework: integrating text-based and survey-based methods in a two-phase study.

To address these limitations and broaden the scope of analysis, a second phase of research was conducted through a structured questionnaire survey. Based on the observed variation in cemetery-related behaviors in the first stage, the questionnaire assessed the extent to which these forms of engagement are supported or anticipated by a wider segment of the public. The survey captures self-reported behavioral intentions from a broader sample, including both cemetery visitors (for urban and suburban cemeteries) and non-visitors. This integrative approach enables a more comprehensive examination of how cemeteries are used, perceived, and socially negotiated in contemporary Tokyo, grounding empirical findings in both observational and intentional dimensions of public engagement.

2.3. Social Media Data Analysis

2.3.1. Social Media Data on Public Cemeteries in Tokyo

This study utilized Google Maps as a source of publicly accessible social media content to explore public perceptions and experiences of Tokyo’s metropolitan cemeteries. Google Maps provides location-based user-generated content, including text reviews and shared images, which offers valuable material for spatial and landscape analysis [40]. A total of 1175 valid textual reviews and 1596 user-uploaded images related to eight selected cemeteries were examined. The dataset spans from March 2015 to March 2025. All materials analyzed in this study were publicly accessible on the platform at the time of access. In accordance with Article 30-4 of the Japanese Copyright Act [41]—which permits the use of publicly available online information for non-commercial data analysis under specific conditions—all data were exclusively used for academic research purposes. Duplicate entries, irrelevant content (e.g., public notice boards), and indoor photographs were excluded during the cleaning process to ensure data quality and relevance. All non-English text was translated into English using Google Translate. A sample of 100 reviews was randomly selected and independently checked by two researchers to ensure that the translated content retained its original meaning without major semantic loss.

2.3.2. Topic Modeling

To extract key themes from the collected review texts, this study employed BERTopic, a state-of-the-art topic modeling technique that leverages BERT embeddings and clustering algorithms to generate semantically meaningful topics [42]. Compared to traditional methods, BERTopic is better suited for short texts and can capture contextual nuances in user-generated content.

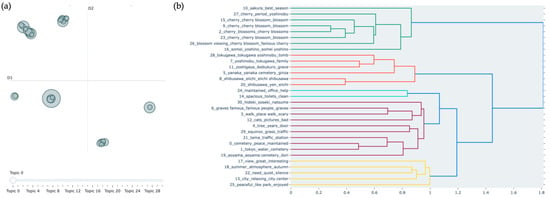

As part of the modeling process, UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) and hierarchical clustering were employed to visualize the distribution of topics and explore the relationships between them (Figure A1). These visualizations supported the identification of overlapping or semantically similar clusters. Based on the visual and semantic analysis, smaller or closely related clusters were manually reviewed and merged to improve topic coherence. The resulting topics were then manually labeled using representative keywords and sample reviews to ensure interpretability and thematic coherence.

2.3.3. Behavior Extraction

To identify the types of user activities associated with cemetery visits, a manual behavior coding process was applied to the collected Google Maps reviews. Each review was read and annotated to extract references to specific non-commemorative and commemorative behaviors described or implied by the user.

This qualitative content analysis involved iteratively grouping semantically similar behaviors based on recurring patterns, thematic relevance, and the representativeness of specific actions. The process enabled the identification of distinct categories of user activity observed in the review texts. Each review could be assigned to one or more behavior categories, depending on the presence of multiple behavioral references in a single text.

2.3.4. Emotion Detection

To examine the emotional content of the user-generated reviews, sentiment analysis was conducted using the Google Cloud Natural Language API (CNL) (https://cloud.google.com/natural-language/docs/analyzing-sentiment, accessed on 20 March 2025). This tool enables sentence- and document-level sentiment scoring by analyzing the polarity and magnitude of the text. For each review, CNL returned two key metrics: sentiment score (ranging from −1.0 to 1.0) indicates the overall emotional tone; magnitude reflects the emotional intensity or strength of feeling, regardless of polarity. Based on the sentiment score, reviews were categorized into three classes: positive (>0.2), neutral (−0.2 to 0.2), and negative (<−0.2).

2.3.5. Image Feature Extraction

This study employed the Google Cloud Vision API (https://cloud.google.com/vision, accessed on 20 March 2025) to identify and classify visual elements present in user-submitted images. The API provides automated image annotation capabilities by identifying objects, scenes, and concepts within photographs using machine learning–based image classification models. Each image was processed through the label detection function of the Vision API, which returned a set of descriptive labels along with confidence scores. For clarity and interpretability, infrequent labels were excluded from analysis.

2.3.6. Co-Occurrence Analysis of Visual Features

To examine the spatial and symbolic patterns embedded in user-shared images, a co-occurrence analysis was conducted on the labeled visual features extracted from the Google Vision API. For fine-scale spatial content analysis, the image labels were reviewed and categorized into different thematic groups based on their visual and semantic characteristics, following a previously established classification approach [43]. A pairwise co-occurrence matrix was then constructed using the Jaccard coefficient, which quantifies the similarity between two sets by dividing the number of images in which both labels appeared by the number of images in which one of the labels appeared. Based on the resulting co-occurrence matrix, a visual co-occurrence network was generated to represent the structure of label associations. In addition, category-level contribution networks were constructed separately for urban and suburban cemeteries by aggregating co-occurrence values at the category level. To further explore the relationship between physical environments and user engagement, the co-occurrence patterns of visual features were compared with the previously extracted behavior categories.

2.4. Survey Design and Analysis

The questionnaire was designed to obtain a broader and more representative understanding of public engagement with metropolitan cemeteries. While online reviews reflect the views of individuals motivated to share their experiences, the survey captures self-reported behavioral intentions from a wider population, including less vocal users and non-visitors.

In addition to identifying past behaviors, the survey focused on behavioral intentions toward ten categories of cemetery-related activities. Investigating intention, rather than action alone, is essential for capturing latent demand and assessing the public acceptability of multifunctional cemetery spaces.

2.4.1. Participant Recruitment and Group Classification

A web-based questionnaire survey was conducted targeting residents of Tokyo, using the online survey distribution platform Freeasy (https://freeasy24.research-plus.net/, accessed on 1 February 2025). The survey was administered in two stages between February and March 2025: an initial screening followed by the main survey. To ensure demographic comparability across groups, stratified sampling by age group and gender was implemented throughout both stages. Efforts were made to recruit approximately equal numbers of participants in each stratum, thereby minimizing demographic biases in subsequent analyses. In the screening phase, invitations were distributed to 10,000 individuals residing in Tokyo. Based on their responses, participants were classified into three groups according to their cemetery visitation history over the past two years: individuals who had visited public cemeteries exclusively for commemorative purposes (e.g., visiting family graves) were categorized as Commemorative Visitors (CV, N = 2017); those who had visited for other or multiple reasons, such as nature appreciation or cultural interest, were categorized as Multi-purpose Visitors (MPV, N = 462); and those who had not visited any public cemeteries were categorized as Non-visitors (NV, N = 7521).

Following this classification and sampling process, the main questionnaire was administered to investigate participants’ behavioral intentions regarding non-commemorative activities in cemetery spaces. A total of 718 responses were collected, of which 605 were deemed valid (CV = 200, MPV = 222, NV = 183), yielding a valid response rate of 84.26%. Responses were excluded if they demonstrated patterns indicative of response bias.

2.4.2. Questionnaire Structure

The questionnaire was designed to assess respondents’ willingness to engage in a variety of non-commemorative activities in cemetery settings. At the beginning of the survey, respondents were asked to select the Tokyo Metropolitan Cemetery they had visited most frequently in the past two years. Activity categories were initially derived from a content analysis of online reviews and further refined through field observations. Environmental evaluation was excluded from the final instrument, as it primarily reflected reviewer-specific behavior rather than in situ engagement.

In response to policy directives from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government regarding cemetery regeneration, a new item addressing the emergency use of cemetery spaces was added. The final questionnaire included items on the following behaviors: nature enjoyment, cultural and historical engagement, spirituality and tranquility, leisure walking, commemoration, everyday mobility, physical activity, social interaction, photography and event participation, and emergency use.

For each activity, respondents indicated their willingness on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”), responding to prompts framed as: “Would you be willing to engage in [specific activity] in the cemetery setting?”

2.4.3. Statistics Analysis

Descriptive statistics were first calculated to determine the mean willingness scores for each of the ten non-commemorative activity types across the three respondent groups: CV, MPV, and NV. As the data did not meet the assumptions of normality, Kruskal–Wallis tests were employed to examine overall group differences. Where significant effects were found, Dunn’s post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction were used for pairwise comparisons.

To compare behavioral willingness between urban and suburban cemetery visitors, Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted for each activity, separately within the CV and MPV groups. This non-parametric approach was chosen due to the ordinal nature of the Likert-scale data and the violation of normality assumptions. A Bonferroni adjustment was applied to control for Type I error across the ten activity comparisons.

Finally, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on the ten behavioral intention items to identify latent dimensions of activity preference. The adequacy of the correlation matrix was confirmed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Items with factor loadings above 0.50 were retained, and standardized factor scores were calculated via the regression method for subsequent group-wise comparison.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Online Reviews

3.1.1. Topic Modeling Results

To identify the key points of visitors’ perceptions and experiences in cemeteries, thematic analysis of online reviews was conducted. In this analysis, eight major topics were identified (Table 2), each representing a distinct aspect of cemetery use and perception. High-frequency feature words within each topic were extracted to represent the themes, and the semantic relationships among these words helped to clarify the overall context of each topic. The most frequent theme was Cultural and Historical Engagement (26.72%), followed by Management and Maintenance (19.54%) and Seasonal Nature Experience (17.96%).

Table 2.

Summary of topics extracted from cemetery reviews.

These thematic categories reflect the diverse ways in which visitors interact with and experience cemetery spaces. The Cultural and Historical Engagement theme underscores the role of cemeteries as sites of heritage and historical memory, with comments frequently highlighting the presence of graves of notable individuals and the unique stories embedded in these spaces. The Management and Maintenance theme captures visitors’ observations about the cleanliness and upkeep of cemetery grounds, as well as the availability of amenities such as public toilets and rest areas, which contribute to their practical use. The Seasonal Nature Experience theme illustrates the importance of cemeteries as seasonal landscapes, providing visitors with opportunities to enjoy natural beauty, especially during cherry blossom periods.

In addition, several other themes highlight more specific aspects of cemetery experiences. The Perceived Green and Spatial Environment theme (6.81%) relates to visitors’ perceptions of green spaces, spatial arrangements, and the surrounding natural environment, often conveyed through impressions of trees, scenic views, and overall landscape qualities. The Spiritual and Tranquil Experience theme (4.34%) emphasizes the calming and contemplative atmosphere of cemeteries, with visitors describing a sense of peace and solitude within these spaces. Walking Experience (5.62%) focuses on cemeteries as places for leisurely walking, including experiences during both day and night, which can evoke feelings of tranquility and occasional unease. Finally, the Commemoration and Family Practices theme (1.19%) highlights how cemeteries are used as spaces for family remembrance and cultural practices, such as equinox-related visits and personal rituals.

A portion of the reviews (17.79%) were not assigned to specific topics, possibly because they encompassed multiple thematic aspects, thereby hindering a clear classification. Overall, the distribution of these themes highlights the multifunctional role of cemeteries in Tokyo, encompassing not only cultural heritage, seasonal enjoyment, and spiritual experiences, but also a variety of other non-commemorative uses.

3.1.2. Behavioral and Sentiment Patterns

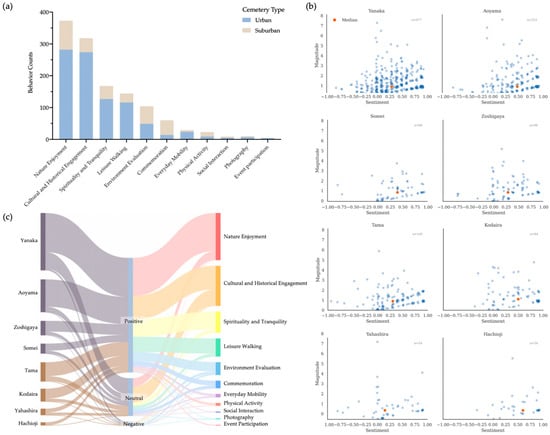

To further understand patterns of cemetery usage, ten distinct behavior categories were identified through qualitative coding, reflecting a range of commemorative and non-commemorative activities described by reviewers. These categories include Nature Enjoyment, Cultural and Historical Engagement, Spirituality and Tranquility, Leisure Walking, Environment Evaluation, Everyday Mobility, Physical Activity, Social Interaction, Photography, and Event Participation. Detailed definitions and representative examples for each category are provided in Table A1.

The distribution of these behaviors is illustrated in Figure 4a, with Nature Enjoyment (30.03%) and Cultural and Historical Engagement (25.60%) emerging as the most frequently observed activities, underscoring the role of cemeteries as spaces for both environmental appreciation and cultural reflection. These were followed by Spirituality and Tranquility (13.53%), Leisure Walking (11.59%), and Environment Evaluation (8.37%), indicating additional functions related to psychological restoration and spatial leisure recreation. In contrast, behaviors such as Everyday Mobility (2.33%), Physical Activity (1.85%), Social Interaction (0.72%), Photography (0.81%), and Event Participation (0.32%) were relatively infrequent, suggesting limited engagement in more active or communal forms of use. Notably, Commemoration accounted for only 4.83% of all identified behaviors. While this does not necessarily reflect the overall purpose of cemetery visitation, it implies that among online reviewers, traditional grave-visiting was not the dominant focus.

Figure 4.

Behavioral patterns and sentiment dynamics across public cemeteries. (a) Distribution of visitor behaviors across 8 public cemeteries; (b) sentiment–magnitude patterns for 8 public cemeteries; (c) relationship between sentiment polarity and behavioral categories. Cemeteries are divided into urban (Yanaka, Aoyama, Zoshigaya, Somei) and suburban (Tama, Kodaira, Yahashira, Hachioji) locations. Flow widths represent the number of reviews linked to each sentiment category, which are further connected to specific behavioral tags. The figure highlights sentiment–behavior associations, with cemetery names included to contextualize the sources of sentiment.

Cemeteries were categorized into urban and suburban types to examine spatial differences in behavioral patterns, and the distribution of behavior counts was compared accordingly (Figure 4a). Overall, urban cemeteries exhibited higher absolute frequencies across most behavior categories, particularly in Nature Enjoyment and Cultural and Historical Engagement. A notable difference was observed in the Commemoration category: suburban cemeteries had a markedly higher proportion of commemorative behaviors relative to their total behavior counts, whereas urban cemeteries showed comparatively lower engagement in this traditional function. This suggests that among reviewers, suburban cemeteries were more often associated with conventional grave-visiting practices, while urban cemeteries tended to be referenced in the context of broader experiential or observational uses.

The affective responses associated with cemetery visits were explored by sentiment analysis conducted on the review texts. Overall, the emotional tone was predominantly neutral and positive, with an average sentiment score of 0.36 and a mean magnitude of 1.21, indicating generally favorable and moderately intense emotional expressions (Figure 4b). Moreover, when comparing cemeteries by spatial context, no substantial differences were observed between urban and suburban cemeteries in terms of either sentiment polarity or emotional magnitude.

To further explore the relationship between emotional valence and behavioral tendencies, a Sankey diagram was constructed to visualize the co-occurrence of sentiment polarity and overall behavior categories (Figure 4c). The results show that most behaviors were associated with positive sentiment, particularly those related to Nature Enjoyment, Spirituality and Tranquility, and Leisure Walking, indicating that these experiences often elicited favorable emotional responses. In contrast, although positive sentiment dominated overall, a relatively high proportion of neutral sentiment was observed in reviews mentioning Cultural and Historical Engagement as well as Commemoration. Additionally, while negative sentiment was rare across the dataset, it was most frequently linked to Environment Evaluation.

3.2. Visual Element Analysis

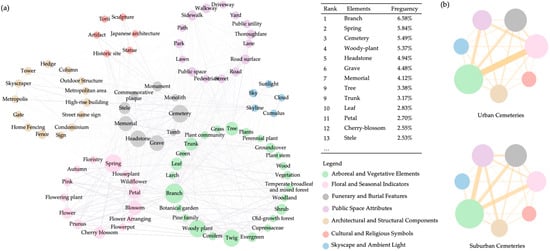

3.2.1. Visual Features Extraction

To understand how visitors perceive environmental features within cemetery spaces, physical landscape elements were extracted from user-uploaded images (Figure 5a). Based on visual characteristics and semantic similarity, the identified elements were grouped into six categories: (1) Arboreal and Vegetative Elements, (2) Floral and Seasonal Indicators, (3) Funerary and Burial Features, (4) Public Space Attributes, (5) Architectural and Structural Components, (6) Cultural and Religious Symbols, and (7) Skyscape and Ambient Light. The descriptions and included labels are listed in Table A2.

Figure 5.

Co-occurrence patterns and category contributions of perceived landscape features in cemetery images. (a) Visual co-occurrence network of landscape elements (n > 10). (b) Category contribution networks for urban and suburban cemeteries. Edge thickness indicates the strength of co-occurrence between element categories based on image analysis, with co-occurrence rates calculated using the Jaccard coefficient.

Among these, Arboreal and Vegetative Elements were the most frequently perceived, indicating a strong visual presence of trees, greenery, and other plant-based features. These were followed by Floral and Seasonal Indicators—such as cherry blossoms and petals—and Funerary and Burial Features, including gravestones and memorials. In contrast, elements related to Cultural and Religious Symbols and Skyscape and Ambient Light were less commonly detected.

This overall pattern remained consistent across both urban and suburban cemeteries, with Arboreal and Vegetative Elements continuing to dominate as the most prominent category in both settings (Figure 5b). However, notable differences were observed in the relative prominence of other categories. In urban cemeteries, Floral and Seasonal Indicators were more salient than Public Space Attributes, reflecting a greater emphasis on seasonal aesthetics such as cherry blossoms. Conversely, in suburban cemeteries, Public Space Attributes appeared more prominent than seasonal elements, suggesting a stronger visual presence of paths and open areas in these settings. These distinctions highlight subtle variations in the visual character and environmental emphasis of cemeteries depending on their spatial context, and are consistent with the behavioral analysis, which similarly indicated a stronger emphasis on seasonal and aesthetic engagement in urban cemeteries, and more functional usage in suburban settings.

3.2.2. Association Between Behaviors and Visual Features

To explore the relationship between visitor behaviors and perceived physical elements, a co-occurrence analysis was conducted using reviews that contained both behavioral information and user-uploaded images (Figure 5). Due to the limited availability of images, behavior categories were filtered based on the number of image-containing reviews to ensure sufficient data for reliable co-occurrence analysis.

Across the seven selected behaviors, distinct yet thematically overlapping co-occurrence patterns emerged. Nature Enjoyment (Figure 6a) was predominantly associated with arboreal and floral elements—trees, petals, and seasonal indicators such as cherry blossoms—highlighting an aesthetic engagement with the transient beauty of nature. In contrast, Cultural and Historical Engagement (Figure 6b) and Commemoration (Figure 6e) were strongly tied to funerary features such as gravestones, memorials, and cemetery infrastructure, reflecting a continued emphasis on traditional cemetery symbolism. Meanwhile, Spirituality and Tranquility (Figure 6c) and Leisure Walking (Figure 6d) demonstrated more heterogeneous co-occurrence patterns, encompassing both vegetative and public space elements, suggesting multifaceted uses of the cemetery landscape that transcend singular functional categories. Everyday Mobility (Figure 6f) was associated with infrastructural elements like roads and boundary features, reinforcing its utilitarian and transitional nature. Finally, Environmental Evaluation (Figure 6g) frequently co-occurred with physical features such as paving conditions and surrounding vegetation, indicating a more analytical mode of engagement concerned with spatial quality and maintenance.

Figure 6.

Associations between behavioral categories and perceived landscape elements. (a) Nature Enjoyment; (b) Cultural and Historical Engagement; (c) Spirituality and Tranquility; (d) Leisure Walking; (e) Commemoration; (f) Everyday Mobility; (g) Environmental Evaluation. Node size reflects the frequency of co-occurrence. Legend applies to all subfigures (a–g).

Collectively, these patterns illustrate a spectrum of interactions, ranging from symbolic and commemorative uses to aesthetic, recreational, and functional engagements within cemetery spaces.

3.3. Behavioral Intentions Analysis

The analysis of questionnaire data provided insight into public willingness to engage in non-commemorative cemetery activities, expanding the perspective beyond those who have already visited and reviewed these spaces. By focusing on behavioral intentions, the survey captured potential engagement patterns across a broader demographic, including non-visitors.

Notably, the Environmental Evaluation category—originally identified in online review data—was excluded from the final questionnaire due to its limited applicability to in situ users. Instead, a new item on Emergency Use was introduced, reflecting recent policy emphasis on disaster-prevention functions and the development of resilient, multi-functional urban green spaces.

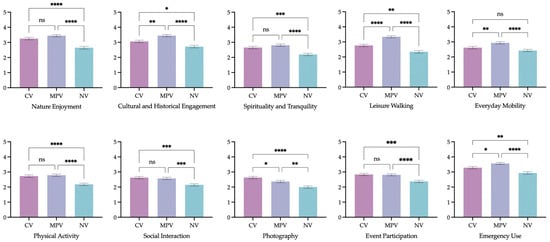

3.3.1. Comparison of Behavioral Intentions Across Visitor Groups

The results of the behavioral intention analysis revealed significant differences across the three visitor groups for all activity categories (Figure 7). NV consistently reported the lowest levels of intention, while MPV and CV generally showed higher and comparable levels across many behaviors.

Figure 7.

Comparison of behavioral intentions across visitor groups. Mean values are shown with error bars indicating ±1 SEM. Statistical significance was tested using Kruskal–Wallis tests with post hoc pairwise comparisons conducted via Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction. Asterisks indicate significance levels: ns = not significant, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

For activities such as Nature Enjoyment, Spirituality and Tranquility, Physical Activity, Social Interaction, and Event Participation, both MPV and CV reported similarly high levels of intention, each significantly greater than NV (p < 0.001), with no significant differences observed between MPV and CV. In contrast, MPV demonstrated markedly higher intentions than both CV and NV for Cultural and Historical Engagement, Leisure Walking, Everyday Mobility and Emergency use, with all pairwise comparisons reaching high levels of significance (p < 0.05 or lower). Photography presented a notable exception to the general trend: CV reported significantly higher intentions than MPV (p < 0.05), reversing the pattern observed in most other behaviors. Additionally, Emergency Use received the highest overall intention scores across all three groups, suggesting a broad recognition of its importance despite its functional specificity.

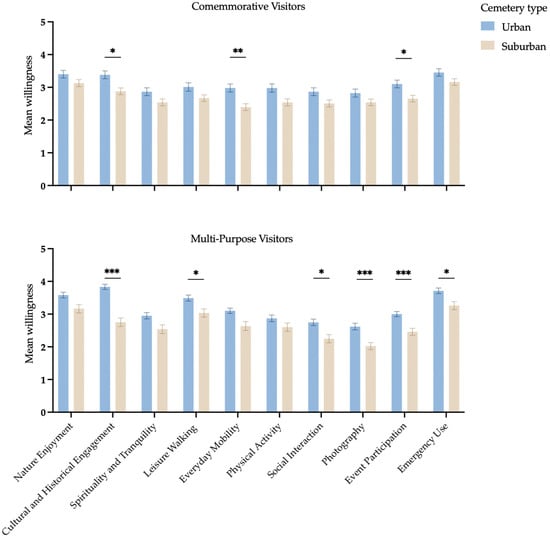

3.3.2. Comparison of Behavioral Intentions Across Cemetery Types

To examine how spatial context may influence behavioral intentions, participants’ willingness to engage in various non-commemorative activities across urban and suburban cemeteries were compared, focusing on CV and MPV, two groups with actual visitation experience (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Comparison of behavioral intentions by cemetery type among commemorative and multi-purpose visitors. Mean values are shown with error bars indicating ±1 SEM. Statistical differences were tested using Mann–Whitney U tests, with Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons. Asterisks indicate significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Overall, spatial differences were more pronounced among MPVs, with urban cemeteries consistently associated with higher behavioral intentions across a wide range of activities. Significant differences were observed in Cultural and Historical Engagement, Leisure Walking, Social Interaction, Photography, Event Participation, and Emergency Use (p < 0.05 or lower), suggesting that MPVs are particularly sensitive to spatial settings when considering multifunctional use. Notably, the strongest spatial contrasts were found in Cultural and Historical Engagement, Photography, and Event Participation (p < 0.001), indicating that urban cemetery environments may be more conducive to cultural, or expressive activities for this group.

In contrast, CVs exhibited relatively stable levels of intention across cemetery types, with fewer behaviors showing significant differences. Only Cultural and Historical Engagement, Everyday Mobility and Event Participation revealed modest but significant urban–suburban contrasts. This suggests that commemorative visitors tend to engage with cemeteries in more consistent ways and are less sensitive to spatial variation.

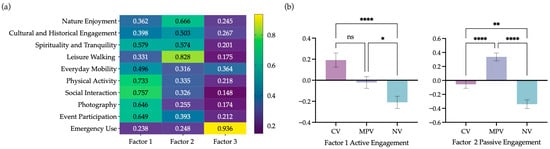

3.3.3. Factor Analysis of Behavioral Intentions and Group Differences

To identify underlying dimensions of behavioral intentions, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the ten activity items. Sampling adequacy was confirmed by a KMO value of 0.931, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicated statistical significance (p < 0.0001), supporting the factorability of the data.

A three-factor solution was extracted using varimax rotation, guided by the interpretability and conceptual clarity of the factor structure (Figure 9a). The first factor was characterized by high loadings on Physical Activity, Social Interaction, Photography, Event Participation, and Everyday Mobility, encompassing behaviors that involve movement, social engagement, and active use of space. Accordingly, this factor was labeled “Active Engagement.” The second factor comprised Nature Enjoyment, Spirituality and Tranquility, Leisure Walking, and Cultural and Historical Engagement, representing more contemplative or observational activities, and was therefore named “Passive Engagement.” The third factor was defined almost entirely by a single item—Emergency Use—which exhibited a strong loading of 0.936, while all other items showed negligible loadings on this factor. Although this factor does not represent a coherent latent construct in the statistical sense, its emergence as a distinct dimension suggests that emergency-related use is qualitatively differentiated from other forms of non-commemorative engagement. For the sake of analytical clarity and consistency, the following analysis focuses on the two-factor structure of active and passive engagement. Nonetheless, the singularity of emergency use—paired with its high intention scores—resonates with recent policy efforts to incorporate disaster-prevention functions into cemetery planning, and will be further discussed in light of its distinct conceptual position.

Figure 9.

Factor structure of behavioral intentions and group differences among visitor types. (a) Factor loadings of the ten behavioral intention items across three extracted factors; (b) comparison of factor scores across CV, MPV, and NV. Mean values are shown with error bars indicating ±1 SEM. Statistical significance was tested using Kruskal–Wallis tests with post hoc pairwise comparisons conducted via Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction. Asterisks denote significance levels (ns = not significant, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001).

Group comparisons of factor scores (Figure 9b) revealed significant differences across visitor types. Intriguingly, CVs reported the highest intentions for Active Engagement, followed by MPV and then NV, with pairwise comparisons between CV and NV reaching statistical significance (p < 0.0001). In Passive Engagement, MPV scored significantly higher than both CV and NV (p < 0.0001), and CV also scored significantly higher than NV (p < 0.01).

These findings highlight distinct engagement profiles across groups—CVs showed a greater inclination toward active, socially oriented uses of cemetery space, while MPVs demonstrated stronger intentions for passive and reflective activities. This contrast suggests that even commemorative visitors may engage deeply with cemeteries through dynamic and expressive forms of interaction.

4. Discussion

4.1. Patterns of Cemetery Use in Tokyo

Tokyo’s metropolitan cemeteries are no longer used solely for remembrance—they are increasingly woven into the fabric of everyday urban life. Moving beyond conventional negative perceptions [4], these spaces are now progressively serving as places of environmental amenity, aesthetic enjoyment, and informal cultural engagement. This aligns with international research that frames cemeteries as recreational or restorative landscapes [14,15,44,45], yet the patterns observed in Tokyo reveal distinct cultural inflections. Among all observed behaviors, the most prominent was nature appreciation, particularly in its seasonal form. This prominence reflects more than a preference for greenery; it evokes the deep-rooted cultural significance of hanami (cherry blossom viewing), an enduring tradition that celebrates the beauty of impermanence and the sensory transitions of time. This aesthetic engagement may also resonate with mono no aware—the traditional Japanese appreciation for impermanence and subtle melancholy [46]—and the melancholic elegance of wabi-sabi, often found in moments where life and death coexist. One visitor described the blooming cherry trees set against gravestones as evoking a gentle, poignant contrast, unlike the spectacle of more crowded hanami sites. These perceptions suggest that seasonal use of cemeteries in Japan transcends recreation or visual pleasure. It is entangled with cultural ways of seeing and feeling—where beauty is found not in permanence, but in evanescence, and where the cemetery becomes not merely a space of the dead, but a reflective landscape of nature, time, and mortality.

Beyond seasonal appreciation, cultural memory emerged as another prominent mode of engagement. Metropolitan cemeteries in Tokyo serve as living archives of historical and cultural identity [47], holding the remains of iconic figures such as Tokugawa Ieyasu and Natsume Sōseki, as well as symbols woven into the fabric of popular memory like Hachikō, the faithful dog buried beside his master. These spaces are also architectural palimpsests. Temples, stone pagodas, and other structures dating back to the Shōwa era are scattered throughout, offering material traces of evolving religious and civic histories. These visits are not always driven by personal commemoration—they often reflect a desire to connect with shared cultural narratives and iconic historical figures, highlighting how the perception of cemeteries is shifting from funerary spaces toward sites of cultural heritage [12,13,23], offering new modes of engagement that combine learning, reflection, and spatial experience. While not part of organized tourism, such behavior parallels what has been described as “cemetery tourism (thanatourism)” [48], where visitors seek out the historical, architectural, and symbolic value of burial landscapes. In this sense, cemeteries serve as open-air repositories—where individual remembrance merges with collective heritage, and where the urban landscape becomes a site of both mourning and meaning-making.

The spirituality and tranquility observed in Tokyo’s cemeteries are characterized by emotional calm and reflective solace, as frequently described by visitors. These experiences constitute a form of secular spirituality—an affective engagement with the environment that is deeply felt yet untethered from formal religious practices. The serene green setting of the cemetery itself appears to support this introspective mood. Studies have shown that natural features can evoke a “sense of spirituality” [49,50] and even trigger transcendent emotional responses [15]. The tranquil atmosphere of Tokyo’s cemeteries offers similar quietly profound encounters. Many visitors reported feeling a sense of relief from the pressures of urban life when spending time in these quiet green spaces—an effect echoed by findings in Helsinki, where cemeteries were valued as places for “escaping stress” [18]. In such moments of spiritual reflection, the cemetery functions as a therapeutic landscape or restorative environment [51], fostering mental calm and a sense of unity with nature.

Taken as a whole, the behavioral patterns observed suggest a prevailing tendency toward passive engagement, a mode of use that is contemplative, respectful and intentionally unobtrusive. Rather than treating cemeteries as conventional public parks, most visitors in Tokyo seem to inhabit these spaces with quiet attentiveness, engaging in ways that preserve the atmosphere of reverence. In other cultural contexts, different yet equally considerate patterns of cemetery use have been documented. For example, in Scandinavian countries, public cemeteries are more openly integrated into daily life and are frequently used for jogging [44], dog walking [16], and other forms of active recreation [6,45]. Although these activities are more physically dynamic, they remain low-impact and quiet, aligning with the tranquil and respectful character of cemetery landscapes. Conversely, in many Chinese cities, cemeteries are often perceived as undesirable or even taboo, remaining spatially and symbolically segregated from everyday urban rhythms [52]. These contrasts reveal that cemetery use is never neutral—it is culturally situated and emotionally coded. How people move through these spaces—often with restraint and quiet observation—suggests a sensitivity to context, one that reflects shared cultural norms around reverence, tranquility, and spatial decorum.

4.2. Affective and Environmental Dimensions of Cemetery Behaviors

The sentiment analysis of user-generated reviews revealed that public cemeteries in Tokyo are not merely perceived as solemn or mournful spaces, but are often described in emotionally positive terms—especially in relation to nature and tranquility. Further examination of sentiment-behavior associations revealed that emotional tone varied depending on the type of engagement. Positive sentiment was most frequently linked with behaviors such as nature enjoyment, leisure walking, and spiritual reflection. These affective responses may stem not only from the immediate aesthetic appeal of the environment, but also from the broader psychological benefits associated with cemetery spaces as sites of calm and restoration. Previous studies have noted that cemeteries—through their nature-rich and visually soothing settings—can elicit positive emotional responses and support mental well-being [52,53,54,55].

In contrast, behaviors related to cultural and historical engagement and commemoration were more often associated with neutral sentiment, possibly indicating a more reflective or cognitive mode of interaction rather than overt emotional expression. Similar patterns have been observed in previous research on online reviews of urban green spaces, where cultural content contributed less to the prediction of positive sentiment, but consistently predicted non-positive reactions [56]. Although negative sentiment constituted only a small proportion overall, it appeared most frequently in reviews categorized as environmental evaluation, particularly those referencing spatial legibility, insufficient amenities, or socially contested behaviors. This pattern suggests that while cemeteries are generally viewed as tranquil and restorative, they can be held to stricter—if more implicit—standards of social propriety than other urban public spaces.

In addition to emotional tone, spatial perception also plays a key role in shaping cemetery experience. Nature emerges not merely as a backdrop but as a central actor in cemetery spaces, shaping both how these environments are perceived and how they are used. Vegetation invites not only aesthetic appreciation, but also subtly guides behavioral patterns and emotional tone—a dynamic echoed in prior studies identifying greenery as one of the most valued aspects of cemetery design [57]. The co-occurrence of behaviors and perceived landscape elements suggests a kind of spatial choreography, where natural and structured elements cue different forms of engagement. These associations are not strictly bounded but overlapping and fluid, reflecting an interplay between spatial texture and human intent. A comparable spatial sensibility was observed in Berlin, where vegetation and were highly valued by those motivated by nature appreciation, whereas mourners expressed greater preference for structured elements, such as monuments and chapels [15]. In some European and Scandinavian contexts, such spatial sensibilities are more formally embedded in cemetery design, with deliberate efforts to visually or symbolically separate burial areas from public zones. This approach enables the accommodation of both commemorative and active uses while minimizing potential conflict. In contrast, this study finds that Tokyo cemeteries tend to exhibit more integrated and porous spatial configurations. Burial areas are often interwoven with green spaces, paths, and circulation routes across different behavioral contexts, rather than being visually enclosed or clearly zoned. This openness allows commemorative and everyday activities to coexist in close proximity, shaped more by subtle spatial cues than by rigid boundaries. These converging insights underscore the capacity of urban cemeteries to accommodate a spectrum of behavioral orientations through layered and differentiated spatial configurations. When spatially attuned, cemeteries can thus function as flexible landscapes—capable of supporting diverse and coexisting modes of urban life.

4.3. Latent Dimensions of Non-Commemorative Engagement

Although non-commemorative engagement features prominently in the online review data, the screening survey reveals a different picture: among individuals who had visited Tokyo’s public cemeteries within the past two years, only approximately one-fifth reported doing so for multi-purpose reasons. This suggests that, despite signs of diversification, public cemeteries in Tokyo remain primarily commemorative spaces for the majority of users. This discrepancy also reflects the inherent user bias in platforms like Google Maps, where those engaging in atypical or more recreational behaviors may be more inclined to leave reviews [39,58]. While identifying differences between online reviewers and the broader population was not the main objective of this study, it is noteworthy that the past behavioral patterns of multi-purpose respondents appeared generally aligned with those extracted from the Google Maps reviews—albeit with relatively more emphasis on leisure walking and everyday mobility.

Beyond the patterns identified in online reviews, the questionnaire data offers a more systematic view of behavioral intentions. One of the clearest patterns to emerge from this study is the strong association between prior visitation and behavioral willingness. Individuals who had engaged with cemeteries for multi-purpose reasons reported the highest levels of intention across most activity types, echoing earlier studies that highlight the aesthetic and restorative motivations of less commemorative users [53]. Interestingly, even individuals who had visited cemeteries solely for commemorative purposes expressed significantly higher intentions to participate in non-commemorative activities compared to non-visitors. This suggests that the act of visiting itself—regardless of its original purpose—may foster a form of spatial familiarity or emotional attunement that lowers psychological barriers to diverse forms of engagement. This pattern stands in contrast to findings from Taiwan, where no notable differences in recreational engagement were observed between those with and without prior cemetery visiting experiences [59]. The divergence may point to contextual differences in how cemetery spaces are framed, experienced, and imagined. In Tokyo’s case, gradual shifts in planning discourse and public perception may be nurturing a more fluid understanding of what cemeteries can be—less bounded by commemorative conventions and more open to everyday appropriations.

Analysis of non-commemorative behavioral intentions revealed two distinct yet interpretable dimensions: Active Engagement and Passive Engagement. This typology resonates with previous qualitative research in Nordic context, which examined public acceptance of recreational activities in cemeteries [21]. Passive forms of engagement tend to enjoy broader social acceptability, likely because they align more closely with prevailing norms of reverence and restraint in cemetery settings. Notably, although emergency use did not cluster with other behavioral items, its conceptual distinctiveness should not be interpreted as marginality. On the contrary, its high intention scores reveal broad public recognition of cemeteries as viable disaster-response infrastructure. This combination of cognitive separation and strong acceptance underscores the unique status of emergency use: it is not part of the everyday repertoire, but it is firmly within the collective imagination of what cemeteries can be—especially in times of crisis. In this sense, the multifunctionality of cemeteries includes not only leisure and contemplation, but contingency itself.

4.4. Who Has the Right to Act? Relational Legitimacy in Cemetery Spaces

Perhaps most unexpectedly, it was commemorative visitors who expressed the strongest willingness for active engagement—exceeding even those with multi-purpose motivations. This finding may be understood not merely through behavioral openness, but through the lens of relational legitimacy: the idea that a personal connection to the cemetery space grants social and emotional permission for more active forms of engagement. As previous studies have noted, everyday acts such as drinking coffee or eating a sandwich are often viewed as acceptable when performed by mourners, yet may appear inappropriate or disruptive when enacted by unrelated individuals [21]. In this context, actions that might otherwise be hesitant for non-stakeholders become permissible for commemorative visitors because they are framed as part of a dialogue with the deceased or an act of remembrance. Building on these insights, the current study suggests that willingness for active use depends less on functional openness or affective familiarity, and more on the perceived legitimacy to act. Commemorative visitors, by virtue of their ties to the deceased, are socially recognized as entitled users—their actions more readily interpreted as respectful and meaningful. In contrast, those without such relational claims—lacking both context and connection—may lack the symbolic authority to act, regardless of their intentions. In this light, the latent dimensions of cemetery engagement reflect more than patterns of use or degrees of attachment—they reveal how spatial practices are conditioned by structures of belonging, entitlement, and moral legitimacy within spaces marked by both intimacy and collective significance.

4.5. Contextual Variations in Cemetery Engagement: Urban and Suburban Variations

The spatial context in which cemeteries are situated appears to subtly shape how they are perceived, inhabited, and used. While both urban and suburban cemeteries support a spectrum of commemorative and non-commemorative behaviors, a divergence in functional orientation begins to emerge. In suburban contexts, cemetery use remains more closely aligned with traditional commemorative practices. Urban cemeteries, by contrast, are more frequently approached as sites of recreational engagement. Visitors to urban cemeteries likewise reported higher intentions to engage in non-commemorative behaviors, regardless of their original motivation for visiting. This distinction may reflect more than physical layout; it signals broader shifts in public expectations surrounding green space and its everyday accessibility.

In compact urban settings, cemeteries may be more readily interpreted as extensions of the everyday landscape—porous, multifunctional, and capable of supporting a diversity of uses beyond mourning. In this sense, urban cemeteries appear to occupy a more fluid position within the city’s green infrastructure, gradually dissolving the boundaries between memorial function and everyday utility. Their liminal status—at once sacred and ordinary, bounded and accessible—invites reimagining how memory, nature, and public life might coexist within the same spatial frame.

4.6. Aligning Policy Vision with Public Experience in Cemetery Management

This study offers empirical insights that may inform the ongoing regeneration of Tokyo’s metropolitan cemeteries. While existing policy frameworks emphasize an integrated vision that combines commemorative, ecological, and cultural functions, our findings suggest that public engagement with this vision remains uneven. In particular, lower willingness among non-visitors and suburban residents to participate in non-commemorative activities reflects broader questions about how such spaces are socially interpreted, and which forms of use are considered appropriate or legitimate.

Such variation should not be regarded as a barrier to be removed, but rather as an inherent feature of the gradual and negotiated transition that multifunctional spaces often undergo. Public-facing interpretive tools—such as on-site signage, cultural narratives, or guided pathways—are less about promoting specific behaviors than about conveying the layered meanings of cemetery landscapes and support more informed engagement. At the same time, the heterogeneity in user attitudes underscores the importance of adopting flexible, context-sensitive management approaches. Instead of applying a uniform model, cemetery governance would be strengthened by recognizing local patterns of use and expectation—for instance, maintaining contemplative settings in sites primarily used for remembrance, while accommodating low-impact cultural or seasonal activities in cemeteries where such uses are already emergent.

Such strategies do not assume universal endorsement of multifunctionality, but acknowledge that its realization is likely to proceed incrementally, shaped by evolving public values, cultural norms, and spatial contexts.

4.7. Limitations and Future Work

Despite the contributions, this study has several clear limitations. First, the research was conducted solely in Tokyo, and the findings are therefore embedded in a specific cultural and urban context. The concept of “Japanese cemeteries” should not be regarded as a unified or monolithic system. Rather, it represents a diverse mosaic of regionally distinct practices, shaped by local customs, religious traditions, and spatial planning histories. This contextual specificity limits the generalizability of the results to other regions in Japan or broader sociocultural settings. Second, this study offers a preliminary exploration of cemetery transformation and public behavior in Tokyo, and does not address the underlying psychological or social mechanisms driving behavioral intentions. Third, the sampling strategy adopted in this study prioritized analytical balance over representativeness. Specifically, roughly equal group sizes were selected for commemorative visitors, multi-purpose visitors, and non-visitors in order to facilitate meaningful and reliable inter-group comparisons. While this controlled design improves statistical stability and comparability, it does not reflect the actual distribution of visitor intentions in the general population.

To address these limitations, future research would benefit from expanding the geographical scope to include a wider range of Japanese cities, enabling comparative analyses across spatial and cultural contexts. In addition, incorporating more explanatory approaches could help uncover the deeper experiential and perceptual processes through which individuals relate to cemetery spaces. Moreover, employing proportionally representative or population-based sampling could help clarify the actual behavioral tendencies of urban cemetery users. Such approaches would not only enrich our understanding of multifunctional cemetery use, but also offer insights into how behavioral patterns and intentions are shaped by evolving spatial, cultural, and institutional contexts in urban environments.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the evolving role of metropolitan cemeteries in Tokyo by examining patterns of user behavior, emotional response, spatial perception, and behavioral intention across both urban and suburban contexts. By integrating user-generated reviews, images, and survey data, it offers new empirical insights into how cemeteries are being reimagined as multifunctional public spaces within the contemporary city. The findings suggest that, while commemorative purposes remain central, these spaces are increasingly perceived and used in diverse ways—particularly in urban settings where seasonal nature appreciation, cultural reflection, and quiet leisure have become more common. Such behaviors were often accompanied by calm or positive emotions and shaped by the spatial and symbolic qualities of the environment. These patterns suggest a gradual shift in public attitudes, with cemeteries increasingly viewed not only as spaces of mourning but also as reflective landscapes that intersect with everyday urban experiences.

While some of these non-commemorative uses are already observable, the willingness to engage in them remains uneven. Prior visitation, especially for multiple purposes, tended to correlate with greater behavioral openness, while non-visitors expressed more hesitation. These patterns also varied by location: urban cemeteries were more closely associated with diverse and reflective uses, whereas suburban sites retained a more strongly commemorative character. Beyond spatial familiarity, the sense of having a personal or symbolic connection to the space also appeared to shape whether individuals felt comfortable engaging more actively.

Taken together, this study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of cemetery multifunctionality by foregrounding user experience and highlighting how spatial context and relational claims influence public perceptions and behavioral intentions. In doing so, it complements existing planning-oriented literature with a user-centered perspective. These insights also offer practical implications for cemetery management. As multifunctionality continues to evolve, the ability of cemeteries to accommodate diverse forms of engagement will depend not only on thoughtful spatial planning, but also on culturally sensitive management strategies that incorporate interpretive tools and respond to the varying expectations of different user groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and R.M.; methodology, Y.X. and R.M.; formal analysis, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.X. and K.F.; visualization, Y.X.; supervision, K.F.; funding acquisition, Y.X. and K.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Japan Science and Technology Agency, grant number JPMJSP2109 and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Grant Number 24K03144.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy concerns and platform terms-of-service restrictions, the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CV | Commemorative Visitors |

| MPV | Multi-purpose Visitors |

| NV | Non-visitors |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Topic structure and semantic relationships in cemetery review texts via BERTopic. (a) Intertopic distance map (via UMAP); (b) hierarchical clustering of topics based on c-TF-IDF similarity.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Definitions and examples of identified behavior categories.

Table A1.

Definitions and examples of identified behavior categories.

| Category | Definition | Representative Examples from Reviews |

|---|---|---|

| Nature Enjoyment | Expressions of appreciation for natural elements such as trees, flowers and seasons. | “Beautiful cherry blossoms.” “Loved the quiet greenery.” |

| Cultural and Historical Engagement | References to historical knowledge, cultural heritage, or famous individuals associated with the cemetery. | “Visited the grave of a historical figure.” “Reminded me of the Showa era.” |

| Spirituality and Tranquility | Descriptions of emotional calm, spiritual reflection, or a peaceful atmosphere. | “Felt very serene and calming.” “A sacred and quiet place.” |

| Leisure Walking | Walking for pleasure or relaxation. | “Took a walk in the cemetery.” “Nice place for a stroll.” |

| Environment Evaluation | Comments evaluating the physical condition, cleanliness, layout, or design of the space. | “Very well maintained.” “Really big and easy to get lost.” |

| Everyday Mobility | Use of the cemetery as a route for passing through or shortcutting between other destinations, such as commuting or accessing nearby places. | “Used it as a shortcut.” “Walked through on my way to the station.” |

| Physical Activity | Engagement in physically active or mobile behaviors within the cemetery, including jogging, cycling, or walking a dog. | “Went for a jog.” “Rode my bike through the paths.” |

| Social Interaction | Non-commemorative, person-to-person engagement within the cemetery, including casual conversations or shared activities with friends, partners, or family members. | “Talked with an old man I met in the cemetery.” “Enjoying a picnic on the lawn.” |

| Photography | Mention of taking, sharing, or admiring photographs of the cemetery space. | “Great spot for photography.” “Took lots of pictures.” |

| Event Participation | Participation in non-ritual events or community-led activities held within the cemetery. These include educational, environmental, or cultural programs that do not involve direct commemorative or religious practices. | “Participated in a community-led moss cleaning event.” “Participated in a guided tour about old trees.” |

Appendix C

Table A2.

Visual feature categories and label definitions.

Table A2.

Visual feature categories and label definitions.

| Visual Feature Category | Descriptions | Labels |

|---|---|---|

| Arboreal and Vegetative Elements | Tree and plant-related features reflecting natural and ecological aspects. | branch, woody plant, twig, tree, trunk, leaf, shrub, groundcover, evergreen, vegetation, conifers, plants, wood, plant community, pine family, botanical garden, green, grass, larch, temperate broadleaf and mixed forest, Cupressaceae, plant stem, old-growth forest, woodland, perennial plant |

| Floral and Seasonal Indicators | Floral and seasonal elements evoking aesthetic and cultural associations. | spring, blossom, petal, cherry blossom, flower, prunus, pink, flowering plant, flower arranging, floristry, autumn, flowerpot, houseplant, wildflower |

| Funerary and Burial Features | Core cemetery components related to commemoration and burial. | cemetery, headstone, grave, memorial, stele, monument, commemorative plaque, monolith, tomb |

| Public Space Attributes | Circulation and open space elements indicating spatial structure. | road surface, walkway, public space, thoroughfare, park, road, street, lane, public utility, pedestrian, yard, path, lawn, driveway |

| Architectural and Structural Components | Built environment features surrounding or intersecting the cemetery. | fence, high-rise building, home fencing, skyscraper, tower, hedge, condominium, sign, metropolitan area, gate, metropolis, outdoor structure, column, street name sign |

| Cultural and Religious Symbols | Symbolic or ritual elements reflecting cultural and spiritual identity. | statue, sculpture, artifact, historic site, Japanese architecture, torii |

| Skyscape and Ambient Light | Atmospheric elements contributing to ambient perception and openness. | sky, sunlight, cumulus, cloud, skyline |

References

- Długozima, A.; Kosiacka-Beck, E.; Krzykawska, K. Multiuse Cemetery Paradigm: Cemetery as a multifunctional place of social significance–Reshaping a cemetery in the urban space of Eastern Europe. Cities 2025, 156, 105556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, E.G.; Forkuor, D.; Opoku, F. The last cityscapes: Public cemetery management in Kumasi’s Urban Terrain. Mortality 2024, 30, 798–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddrell, A.; Beebeejaun, Y.; Kmec, S.; Wingren, C. Cemeteries and crematoria, forgotten public space in multicultural Europe. An agenda for inclusion and citizenship. Area 2023, 55, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocón, D.; Young, W.P. Bridging the nature-cultural heritage gap: Evaluating sustainable entanglements through cemeteries in urban Asia. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1641–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabalov, P. Invisible public spaces: The role of cemeteries in urban planning and development in Moscow. J. Urban Aff. 2022, 46, 1971–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabalov, P.; Nordh, H. The Future of Urban Cemeteries as Public Spaces: Insights from Oslo and Copenhagen. Plan. Theory Pract. 2022, 23, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpe, B.; Stuhrmann, N.; Jostmeier, A.; Marschner, B. Urban cemeteries: The forgotten but powerful cooling islands. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 934, 173167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, D.E.; Terzi, F. Ice floes in urban furnace: Cooling services of cemeteries in regulating the thermal environment of Istanbul’s urban landscape. Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowinska, R.; Czarna, A.; Kozlowska, M. Cemetery types and the biodiversity of vascular plants—A case study from south-eastern Poland. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, F.; Mikula, P.; Benedetti, Y.; Bussière, R.; Tryjanowski, P. Cemeteries support avian diversity likewise urban parks in European cities: Assessing taxonomic, evolutionary and functional diversity. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 36, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I.; Buchholz, S.; von der Lippe, M.; Seitz, B. Biodiversity functions of urban cemeteries: Evidence from one of the largest Jewish cemeteries in Europe. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 19, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzikowska, A.; Zaręba, A.; Krzemińska, A.; Pawłowski, K. The cultural landscape of rural cemeteries on the Polish–Czech borderlands: Multi-faceted visual analysis as an element of tourism potential assessment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallay, Á.; Mikházi, Z.; Gecséné Tar, I.; Takács, K. Cemeteries as a part of green infrastructure and tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, K.H.; Nordh, H.; Skaar, M. Everyday use of urban cemeteries: A Norwegian case study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 159, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straka, T.M.; Mischo, M.; Petrick, K.J.S.; Kowarik, I. Urban cemeteries as shared habitats for people and nature: Reasons for visit, comforting experiences of nature, and preferences for cultural and natural features. Land 2022, 11, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swensen, G.; Helena, N.; and Brendalsmo, J. A green space between life and death—A case study of activities in Gamlebyen Cemetery in Oslo, Norway. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2016, 70, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugozima, A.; Kosiacka-Beck, E.; Krzykawska, K. Cemetery as multifaceted space with leisure uses in the urban American and Western European context. Leis. Stud. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Evensen, K.H. Qualities and functions ascribed to urban cemeteries across the capital cities of Scandinavia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 33, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingemann, H. Cemeteries in transformation—A Swiss community conflict study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 76, 127729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Phin Keong, V.; Ong, S.K.; Goh, H.C. Chinese cemeteries and environmental ethics: Some insights from Malaysia. Airiti 2014, 41, 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Nordh, H.; Wingren, C.; Uteng, T.P.; Knapskog, M. Disrespectful or socially acceptable? -A nordic case study of cemeteries as recreational landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.K.; Chen, Y. Not or Yes in My Back Yard? A physiological and psychological measurement of urban residents in Taiwan. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, H.C.; Ching, E. Acceptable use of Chinese cemeteries in Kuala Lumpur as perceived by the city’s residents. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 55, 126837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deering, B. From anti-social behaviour to X-rated: Exploring social diversity and conflict in the cemetery. In Deathscapes; Maddrell, A., Sidaway, J.D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Fernández, E. The death taboo: Euphemism and metaphor in epitaphs from the English cemetery of Malaga, Spain. Languages 2023, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, R.A. Cemeteries as public urban green space: Management, funding and form. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, S. Nature’s Embrace: Japan’s Aging Urbanites and New Death Rites; University of Hawai‘i Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2010; pp. 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L. No place, new places: Death and its rituals in urban Asia. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokyo Metropolitan Park Council. Summary of the Recommendation on the Management of Ward-Level Cemeteries: Aoyama Cemetery—A Historical Forest Accumulated by the Passage of Time; Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Construction: Tokyo, Japan, 2002. Available online: https://www.kensetsu.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/documents/d/kensetsu/000007696 (accessed on 3 July 2025). (In Japanese)

- Tokyo Metropolitan Park Council. Summary of the Proposal on the Future of the Regeneration of Yanaka Cemetery; Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Construction: Tokyo, Japan, 2005. Available online: https://www.kensetsu.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/park/tokyo_kouen/shingikai/yanaka (accessed on 3 July 2025). (In Japanese)

- Tokyo Metropolitan Park Council. Proposal on the Future of the Regeneration of Somei Cemetery: A Space That Cultivates Cherry Blossoms and Connects Edo-Period History to the Future; Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Construction: Tokyo, Japan, 2012. Available online: https://www.kensetsu.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/documents/d/kensetsu/000051778 (accessed on 3 July 2025). (In Japanese)