Peri-Urban Land Transformation in the Global South: Revisiting Conceptual Vectors and Theoretical Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Understanding the Transformation of Land in Peri-Urban Contexts

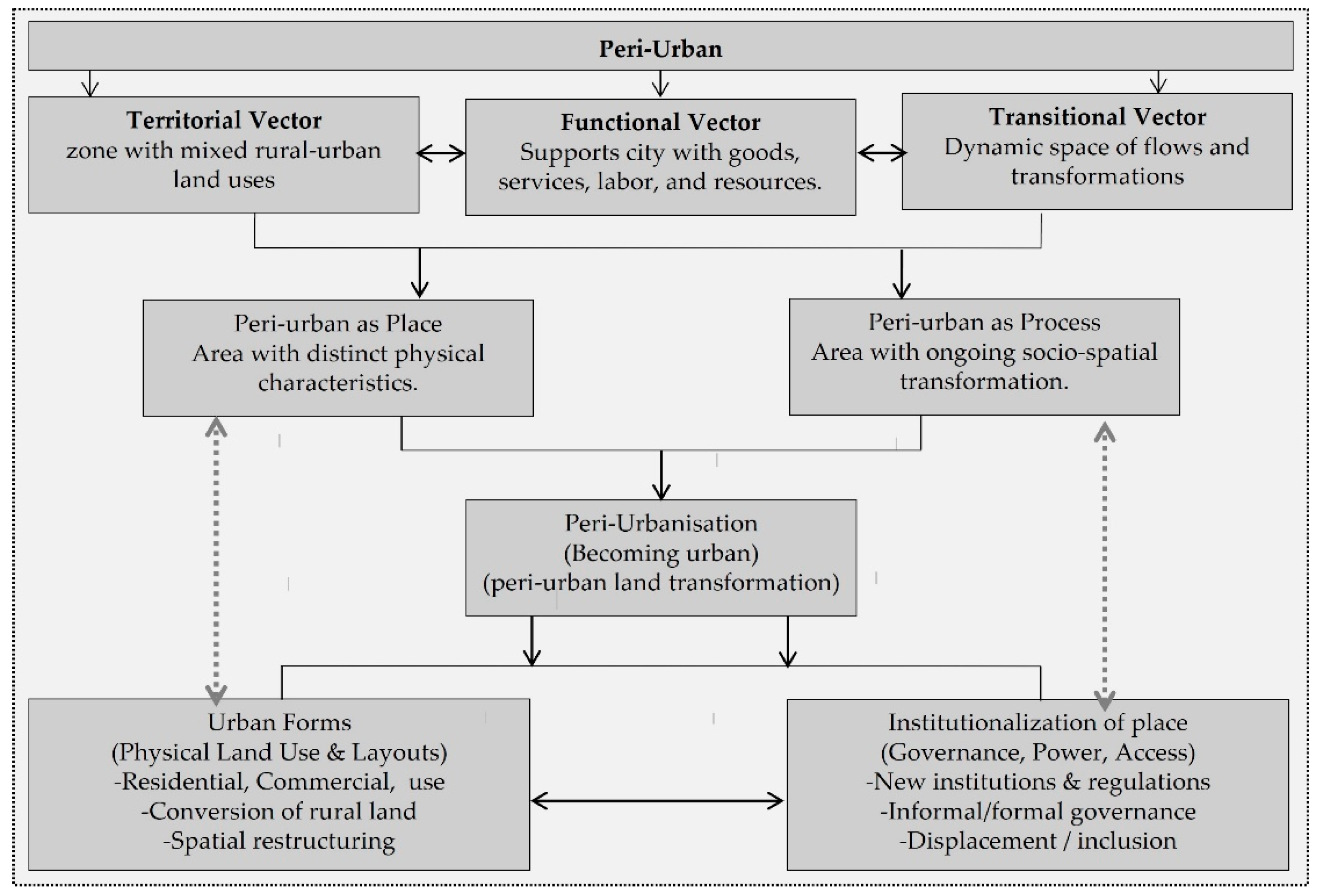

3.1. Understanding the Peri-Urban and Peri-Urbanization

3.2. Peri-Urban Land Transformations: Urban Forms and Institutionalization

4. Understanding Land Transformation Through Theoretical Lenses

4.1. Neo-Classical Economics of Urban Structure and Modernization Theories

4.2. Neo-Marxist and Dependency Theories

4.3. Human Agency, Structuration, and Institutionalism Theories

4.4. Political Ecology and Urban Political Ecology Theoretical Frameworks

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- De Sherbinin, A.; Schiller, A.; Pulsipher, A. The Vulnerability of Global Cities to Climate Hazards. Environ. Urban. 2007, 19, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: 2014 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014.

- UN-Habitat. The State of African Cities 2010: Governance, Inequality and Urban Land Markets; HS/190/10E; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010; p. 279. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/State%20of%20African%20Cities%202010.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Angel, S.; Parent, J.; Civco, D.L.; Blei, A.; Potere, D. The Dimensions of Global Urban Expansion: Estimates and Projections for All Countries, 2000–2050. Prog. Plan. 2011, 75, 53–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, R. After Suburbia: Research and Action in the Suburban Century. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Peri-Urbanization. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Futures; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Urban Environments: Issues on the Peri-Urban Fringe. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008, 33, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K.K. Ageing Societies, Age-Inclusive Spaces and Community Bonding. In Navigating Differences: Integration in Singapore; Chong, T., Ed.; ISEAS Publishing: Singapore, 2020; pp. 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Worku, H.; Lika, T. Urban and Regional Planning Approaches for Sustainable Governance: The Case of Addis Ababa and the Surrounding Area Changing Landscape. City Environ. Interact. 2020, 8, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, G.; Abukashawa, S.; Hussein, M.O. Urban Transformations and Land Governance in Peri-Urban Khartoum: The Case of Soba. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiftachel, O. Theoretical Notes On ‘Gray Cities’: The Coming of Urban Apartheid? Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; McGregor, D.; Nsiah-Gyabaah, K. The Changing Urban-Rural Interface of African Cities: Definitional Issues and an Application to Kumasi, Ghana. Environ. Urban. 2004, 16, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alem, G. Urban Plans and Conflicting Interests in Sustainable Cross-Boundary Land Governance, the Case of National Urban and Regional Plans in Ethiopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhon, M.; Ernstson, H.; Silver, J. Provincializing Urban Political Ecology: Towards a Situated UPE Through African Urbanism: Provincialising Urban Political Ecology. Antipode 2014, 46, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, S.; Narain, V. Land, Water & Power: The Demise of Common Property Resources in Periurban Gurgaon, India. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C. Coding Regimes of Possession. An Essay on Land, Property, and Law. Globalizations 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J.; Isakson, S.R.; Visser, O. The Complex Dynamics of Agriculture as a Financial Asset: Introduction to Symposium. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Pal, A. Drivers of Urban Sprawl in Urbanizing China—A Political Ecology Analysis. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.M. The Anthropology of Human-Environment Relations. Focaal 2018, 2018, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaika, M.; Swyngedouw, E. The Urbanization of Nature: Great Promises, Impasse, and New Beginnings. In The New Blackwell Companion to the City; Bridge, G., Watson, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, B. The State and Financialization of Public Land in the United Kingdom: Financialization of Public Land in the UK. Antipode 2017, 49, 62–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaateba, M.A.; Huang, H.; Adumpo, E.A. Between Co-Production and Institutional Hybridity in Land Delivery: Insights from Local Planning Practice in Peri-Urban Tamale, Ghana. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, L.; Shin, H.B.; López-Morales, E. (Eds.) Global Gentrifications: Uneven Development and Displacement; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, C. Extending the Analysis of Urban Land Conflict: An Example from Johannesburg. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 2779–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.G. Land Tenure in the Changing Peri-Urban Areas of E Thiopia: The Case of Bahir Dar City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1970–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.G. Understanding Competing and Conflicting Interests for Peri-Urban Land in Ethiopia’s Era of Urbanization. Environ. Urban. 2020, 32, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhu, S. Peri-Urban Land Governance in Developing Countries: Understanding the Role, Interaction and Power Relation Among Actors in Tanzania. Urban Forum 2019, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, M. Rethinking Displacement in Peri-Urban Transformation in China. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2017, 49, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meth, M.; Todes, A.; Charlton, S.; Mukwedeya, T.; Houghton, J.; Goodfellow, T.; Belihu, M.S.; Huang, Z.; Asafo, D.M.; Buthelezi, S.; et al. At the City Edge: Situating Peripheries Research in South Africa and Ethiopia. In African Cities and Collaborative Futures; Keith, M., De Souza Santos, A.A., Eds.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastrow, C. Aesthetic Dissent: Urban Redevelopment and Political Belonging in Luanda, Angola: Aesthetic Dissent. Antipode 2017, 49, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T.G. The Sustainability of Extended Urban Spaces in Asia in the Twenty-First Century: Policy and Research Challenges. In Sustainable Landscape Planning in Selected Urban Regions; Yokohari, M., Murakami, A., Hara, Y., Tsuchiya, K., Eds.; Science for Sustainable Societies; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R Package and Shiny App. for Producing PRISMA 2020-Compliant Flow Diagrams, with Interactivity for Optimised Digital Transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashpoor, H.; Ahani, S. Land Tenure-Related Conflicts in Peri-Urban Areas: A Review. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Extended Metropolis: Settlement Transition in Asia. In The Emergence of Desakota Regions in Asia: Expanding a Hypothesis; McGee, T.G., Ed.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, Hawai, 1991; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Follmann, A. Geographies of Peri-urbanization in the Global South. Geogr. Compass 2022, 16, e12650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, L.P.; Raúl, L.; Chen, M.; Guerrero Andrade, J.C.; Akhtar, R.; Mngumi, L.E.; Chander, S.; Srinivas, S.; Roy, M.R. The ‘Peri-Urban Turn’: A Systems Thinking Approach for a Paradigm Shift in Reconceptualising Urban-Rural Futures in the Global South. Habitat Int. 2024, 146, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Becoming Urban: Periurban Dynamics in Vietnam and China—Introduction. Pac. Aff. 2011, 84, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.M.; Eakin, H. An Obsolete Dichotomy? Rethinking the Rural-Urban Interface in Terms of Food Security and Production in the Global South. Geogr. J. 2011, 177, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhan, G. “This Is No Longer the City I Once Knew”. Evictions, the Urban Poor and the Right to the City in Millennial Delhi. Environ. Urban. 2009, 21, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E. Regularization of Informal Settlements in Latin America; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, M.; Rakodi, C. Urban Land Conflict in the Global South: Towards an Analytical Framework. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 2683–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, M. Land Titling and Microcredit in Cambodia: Examining the Reality of Hernando de Soto’s ‘Three Steps to Heaven’. Land 2024, 13, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matunhu, J. A Critique of Modernization and Dependency Theories in Africa: Critical Assessment. Afr. J. Hist. Cult. 2011, 3, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T. Afterword: Are Environmental Imaginaries Culturally Constructed? In Environmental Imaginaries of the Middle East and North Africa; Davis, D.K., Burke, E., Eds.; Ohio University Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2011; pp. 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2007, 610, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levien, M. Regimes of Dispossession: From Steel Towns to Special Economic Zones. Dev. Change 2013, 44, 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhindu, E. Political Economy of Peri-Urban Transformations in Conditions of Neoliberalism in Zimbabwe. In Peri-Urban Developments and Processes in Africa with Special Reference to Zimbabwe; Springer Briefs in Geography; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, S. Assembling Export Markets: The Making and Unmaking of Global Food Connections in West Africa, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T.; Lund, C. Access and Property: A Question of Power and Authority. Dev. Change 2009, 40, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, C.E. What’s Policy Got to Do with It? How the Structure-Agency Debate Can Illuminate Policy Implementation. Am. J. Educ. 2016, 122, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersha, S.; Gebremariam, E.; Gebretsadik, D. Drivers of Informal Land Transformation: Perspective from Peri-Urban Area of Addis Ababa. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 3541–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersha, S.; Mulugeta, S.; Gebremariam, E. Process of Informal Land Transaction: A Case Study in the Peri-Urban Area of Addis Ababa. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 2067–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T. Institutional Theory, New. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; Ritzer, G., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Olsen, J.P. Elaborating the “New Institutionalism”. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions; Binder, S.A., Rhodes, R.A.W., Rockman, B.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A. Peri-Urbanization and the Political Ecology of Differential Sustainability. In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South; Parnell, S., Oldfield, S., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 522–538. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.M. After the Land Grab: Infrastructural Violence and the “Mafia System” in Indonesia’s Oil Palm Plantation Zones. Geoforum 2018, 96, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, L.E.; Bruns, A.; Simon, D. Towards Situated Analyses of Uneven Peri-Urbanisation: An (Urban) Political Ecology Perspective. Antipode 2020, 52, 1237–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, H.; Nowak, S.; Sheppard, E. Everyday Speculation in the Remaking of Peri-Urban Livelihoods and Landscapes. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2023, 55, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, A. Political Ecology I: Where Is Political Ecology? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 43, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; McGregor, D.; Donald, T. Contemporary Perspectives on the Peri-Urban Zones of Cities in Developing Countries. In The Peri-Urban Interface: Approaches to Sustainable Natural and Human Resource Use; Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, VA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, S.; Robinson, J. (Re)Theorizing Cities from the Global South: Looking Beyond Neoliberalism. Urban Geogr. 2012, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzman, K.; Watson, J. Caring Science, Mindful Practice: Implementing Watson’s Human Caring Theory, 2nd ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 978-0-8261-3556–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravetz, J.; Fertner, C.; Nielsen, T.S. The Dynamics of Peri-Urbanization. In Peri-Urban Futures: Scenarios and Models for Land Use Change in Europe; Nilsson, K., Pauleit, S., Bell, S., Aalbers, C., Sick Nielsen, T.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 13–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Peri-Urbanization. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Futures; Brears, R.C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1250–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, V.; Prakash, A. (Eds.) Water Security in Peri-Urban South Asia: Adapting to Climate Change and Urbanization; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsch, C.; Chakraborty, S.; Gomes, S.L.; Kumar, S.; Hermans, L.M. Changing Hydrosocial Cycles in Periurban India. Land 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D. On the Edge: Shaping the Future of Peri-Urban East Asia. 2002. Available online: https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/Webster2002.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Dupont, V. Conflicting Stakes and Governance in the Peripheries of Large Indian Metropolises—An Introduction. Cities 2007, 24, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Kaika, M. Urban Political Ecology. Great Promises, Deadlock… and New Beginnings? Doc. Anàl. Geogr. 2014, 60, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Larkham, P.J. The Study of Urban Form in Great Britain. Urban Morphol. 2006, 10, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Karimi, K. Urban Function Connectivity: Characterisation of Functional Urban Streets with Social Media Check-in Data. Cities 2016, 55, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubneh, M. Policies and Praxis of Land Acquisition, Use, and Development in Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombe, W.J. Land Use Dynamics in Peri-Urban Areas and Their Implications on the Urban Growth and Form: The Case of Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Habitat Int. 2005, 29, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, Y. Mapping Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture Using High Spatial Resolution Satellite Data. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2009, 3, 033523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahana, M.; Ravetz, J.; Patel, P.P.; Dadashpoor, H.; Follmann, A. Where Is the Peri-Urban? A Systematic Review of Peri-Urban Research and Approaches for Its Identification and Demarcation Worldwide. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. Periurbanization as the Institutionalization of Place: The Case of Japan. Cities 2016, 53, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, T.; Assefa, E.; Zeleke, T. Land Use Transformation by Urban Informal Settlements and Ecosystem Impact. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Ferreira, M. The Bureaucratic Politics of Urban Land Rights: (Non)Programmatic Distribution in São Paulo’s Land Regularization Policy. Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 2024, 66, 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulai, I.A.; Enu-kwesi, F.; Agyenim, J.B. Peri-Urbanisation: A Blessing or Scourge? J. Plan. Land Manag. 2020, 1, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M. Modernization Theories of Development. In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology; Callan, H., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippel, S.R.; Visser, O. Introduction to Symposium ‘Reimagining Land: Materiality, Affect and the Uneven Trajectories of Land Transformation’. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.K. Resurrecting the Granary of Rome: Environmental History and French Colonial Expansion in North Africa; Ohio University Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shetler, J. Imagining Serengeti; Ohio University Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Jia, K. How Rent Facilitates Capital Accumulation: A Case Study of Rural Land Capitalization in Suzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 139, 107063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Billon, P.; Sommerville, M. Landing Capital and Assembling ‘Investable Land’ in the Extractive and Agricultural Sectors. Geoforum 2017, 82, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururani, S. Cities in a World of Villages: Agrarian Urbanism and the Making of India’s Urbanizing Frontiers. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 971–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Hanisch, M. Dynamics of Peri-Urban Agricultural Development and Farmers’ Adaptive Behaviour in the Emerging Megacity of Hyderabad, India. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K. Overview of Corruption and Anti-Corruption in Tanzania; Transparency International Anti-Corruption Helpdesk Answer; Transparency International: Berlin, Germany, 2019; p. 29. Available online: https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/assets/uploads/helpdesk/Country-profile-Tanzania-2019_PR.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Potts, D. Urban Economies, Urban Livelihoods and Natural Resource-Based Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Constraints of a Liberalized World Economy. Local Econ. J. Local Econ. Policy Unit 2013, 28, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyshon, A.; Thrift, N. The Capitalization of Almost Everything: The Future of Finance and Capitalism. Theory Cult. Soc. 2007, 24, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dépelteau, F. Relational Thinking in Sociology: Relevance, Concurrence and Dissonance. In The Palgrave Handbook of Relational Sociology; Dépelteau, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F. Theories of Power and Social Change. Power Contestations and Their Implications for Research on Social Change and Innovation. J. Polit. Power 2021, 14, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkamu, B.; Aytenfisu, S. Facing the Challenges in Building Sustainable Land Administration Capacity in Ethiopia. In Facing the Challenges—Building the Capacity; FIG Congress: Sydney, Australia, 2010; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Chitonge, H. Capitalism in Africa: Mutating Capitalist Relations and Social Formations. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 2018, 45, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, S. The Difference That ‘Capitalism’ Makes: On the Merits and Limits of Critical Political Economy in African Studies. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 2017, 44, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecours, A. 1. New Institutionalism: Issues and Questions. In New Institutionalism; Lecours, A., Ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.E.; Yates, J.S. Introduction: Rendering Land Investable. Geoforum 2017, 82, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R.H.; Buur, L. Beyond Land Grabbing. Old Morals and New Perspectives on Contemporary Investments. Geoforum 2016, 72, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenberger, L.; Beban, A. Rupturing Violent Land Imaginaries: Finding Hope through a Land Titling Campaign in Cambodia. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzaninis, Y. Cosmopolitanism beyond the City: Discourses and Experiences of Young Migrants in Post-Suburban Netherlands. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, P. Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction, 3rd ed.; Critical Introductions to Geography; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA; Chichester, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, R. Making Political Ecology; Human Geography in the Making; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.A. Political Ecology: Where Is the Ecology? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayda, A.P.; Walters, B.B. Against Political Ecology. Hum. Ecol. 1999, 27, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. Land’s End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. Gender Equality, Food Security and the Sustainable Development Goals. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 34, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A.J. Bounding Difference: Intersectionality and the Material Production of Gender, Caste, Class and Environment in Nepal. Geoforum 2011, 42, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhon, M. Relational Power in the Governance of a South African E-Waste Transition. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2012, 44, 954–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, A. Urban Political Ecology. Theoretical Concepts, Challenges, and Suggested Future Directions. ERDKUNDE 2010, 64, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, R. Transnational Urban Political Ecology: Health and Infrastructure in the Unbounded City. In The New Blackwell Companion to the City; Bridge, G., Watson, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, H.; Wachsmuth, D. Urbanizing Urban Political Ecology: A Critique of Methodological Cityism. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandy, M. Urban Political Ecology: A Critical Reconfiguration. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 46, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.H.; Zwarteveen, M.; Stead, D.; Bacchin, T.K. Bringing Ecological Urbanism and Urban Political Ecology to Transformative Visions of Water Sensitivity in Cities. Cities 2024, 145, 104685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzaninis, Y.; Mandler, T.; Kaika, M.; Keil, R. Moving Urban Political Ecology beyond the ‘Urbanization of Nature’. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 45, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.L.; Alvim, A.B.; Pereira, I.A.; Leite, C. Nature-Based Solutions in Peri-Urban Areas of Latin American Cities: Lessons from São Paulo, Brazil. In Design for Climate Adaptation; Faircloth, B., Pedersen Zari, M., Thomsen, M.R., Tamke, M., Eds.; Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauleit, S.; Andersson, E.; Anton, B.; Buijs, A.; Haase, D.; Hansen, R.; Kowarik, I.; Stahl Olafsson, A.; Van Der Jagt, S. Urban Green Infrastructure—Connecting People and Nature for Sustainable Cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Scripting Indian and Chinese Urban Spatial Transformation: Adding New Narratives to Gentrification and Suburbanisation Research. Environ. Plan. C Polit. Space 2020, 38, 980–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. Political Ecology. Camb. Encycl. Anthropol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpouzoglou, T.; Marshall, F.; Mehta, L. Towards a Peri-Urban Political Ecology of Water Quality Decline. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekers, M.; Prudham, S. The Socioecological Fix: Fixed Capital, Metabolism, and Hegemony. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2018, 108, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreucci, D.; García-Lamarca, M.; Wedekind, J.; Swyngedouw, E. “Value Grabbing”: A Political Ecology of Rent. Capital. Nat. Social. 2017, 28, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerup, L.; Vassallo, J. The Continuous City: Fourteen Essays on Architecture and Urbanization; Architecture at Rice; Park Books: Zurich, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, J.P.; Cousins, J.J. The Boundaries of Urban Metabolism: Towards a Political–Industrial Ecology. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 39, 702–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahiteme, Y. Manipulating Ambiguous Rules: Informal Actors in Urban Land Management, a Case Study in Kolfe-Keranio Sub-City. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies; NTNU-trykk: Trondheim, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Overarching Analytical Component | Categories of Data | Main Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptualizing Peri-Urban Spaces | Territorial, functional, and transitional conceptual vectors; urban–rural interface and spatial in-betweenness; place vs. process framing | Keil, 2020 [6]; Shih, 2017 [29]; McGee,1991 [35]; Follmann, 2022 [36] Rajendran et al., 2024 [37]; Friedmann, 2011 [38]; Lerner & Eakin, 2011 [39] |

| Peri-Urban Land Transformations and Institutionalization of Place | Rural-to-urban land conversion and changing urban forms; informal and formal land developments; legal pluralism and tenure systems; institutional fragmentation and hybridity | Alem, 2021 [14]; Akaateba et al., 2018 [23]; Adam, 2014 [26], 2020 [27]; Nuhu, 2019 [28]; Bhan, 2009 [40]; Fernandes, 2011 [41]; |

| Understanding Land Transformation through Theoretical Lenses | Actor ecology and power relations in land governance; displacement, speculation, and land commodification Neo-classical economics and modernization theory; land market dynamics and commercialization-led growth Neo-Marxist and dependency theory; class conflict, land grabs, and global–local power asymmetries Structuration and institutional theories; structure–agency relations, resistance, institutional hybridity Political ecology and urban political ecology (UPE); socio-natural transformations and socio-ecological inequalities Poststructuralist political ecology and situated perspectives; everyday power practices, plural meanings, and local agency | Lund, 2024 [17]; Marx, 2015 [25]; Lombard & Rakodi, 2016 [42]; Meth et al., 2021 [30]; Bateman, 2024 [43]; Clapp et al., 2017 [18]; Matunhu, 2011 [44]; Mitchell, 2011 [45]; Friedmann, 2011 [38]; Harvey, 2007 [46]; Levien, 2013 [47]; Mazhindu, 2016 [48]; Adam, 2020 [27]; Ouma, 2015 [49]; Sikor & Lund, 2009, [50]; Coburn, 2016 [51]; Mersha et al., 2022 [52,53]; Lang, 2018 [54]; March & Olsen, 2009 [55]; Lawhon et al., 2014 [15] Allen, 2014 [56]; Li, 2018 [57]; Bartels et al., 2020 [58]; Lawhon et al., 2014 [15] Bartels et al., 2020 [58]; Leitner et al., 2023 [59]; Howard, 2018 [20]; Latour, 2018 [60]; Loftus, 2019 [61] |

| Theoretical Lens | Core Assumptions | Relevance to Peri-Urban Land Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Neo-Classical Economics | Land use is shaped by market competition and rational choices. | Explains land conversion through market-led, demand-driven dynamics. |

| Modernization Theory | Development follows a linear path toward modernity. | Frames peri-urban change as modernization and progress. |

| Neo-Marxist Theory | Capital accumulation restructures land use and society. | Highlights class conflict and land grabs in capitalist urbanization. |

| Dependency Theory | Global structures create unequal development. | Reveals how global interests shape land transformation in the South. |

| Structuration Theory | Social structures and agency are co-constitutive. | Explains how land actors reproduce or resist institutional norms. |

| Institutional Theory | Institutions shape actor behavior and outcomes. | Shows how institutional arrangements mediate land use. |

| Political Ecology | Land issues are rooted in historical and political struggles. | Exposes land-use conflict as outcome of socio-political tensions. |

| Urban Political Ecology | Urban land is produced through socio-natural processes. | Demonstrates how peri-urban land reflects unequal flows of capital and power. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tesfay, S.M.; Gebregiorgis, G.A.; Ayele, D.G. Peri-Urban Land Transformation in the Global South: Revisiting Conceptual Vectors and Theoretical Perspectives. Land 2025, 14, 1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071483

Tesfay SM, Gebregiorgis GA, Ayele DG. Peri-Urban Land Transformation in the Global South: Revisiting Conceptual Vectors and Theoretical Perspectives. Land. 2025; 14(7):1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071483

Chicago/Turabian StyleTesfay, Shiwaye M., Genet Alem Gebregiorgis, and Daniel G. Ayele. 2025. "Peri-Urban Land Transformation in the Global South: Revisiting Conceptual Vectors and Theoretical Perspectives" Land 14, no. 7: 1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071483

APA StyleTesfay, S. M., Gebregiorgis, G. A., & Ayele, D. G. (2025). Peri-Urban Land Transformation in the Global South: Revisiting Conceptual Vectors and Theoretical Perspectives. Land, 14(7), 1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071483