Abstract

Tinos Island, part of the Cyclades Complex in the central Aegean Sea, represents a distinctive case of geocultural heritage where geological formations and cultural identity intersect. This study evaluates the geoeducational and geotouristic potential of Tinos’ geosites using GEOAM methodology, which assesses their scientific, educational, and conservation value. Six geosites are examined to explore their geoeducational potential, including prominent locations such as the Tafoni formations and the Exombourgo granite massif. The findings highlight the significance of these sites, while also identifying challenges related to infrastructure, stakeholder engagement, and sustainable management. By integrating geoethics into geotourism practices, Tinos can adopt a balanced approach that enhances environmental conservation alongside community-driven economic benefits. The study underscores the need for collaborative initiatives to optimize the island’s geoheritage for education and tourism, ensuring its long-term preservation. Geotourism, when responsibly implemented, has the potential to strengthen local identity while advancing sustainable tourism development.

1. Introduction

Geotourism is a dynamic combination of education and recreation that emphasizes the preservation and appreciation of geological heritage while actively promoting sustainable development [1]. The integration of geodiversity with biodiversity, local culture, architecture, gastronomy, and other regional assets goes beyond traditional tourism, fostering a deeper understanding of the intrinsic value of geosites in both local and global contexts [2,3,4,5]. Geotourism also serves as a means of diversifying rural and insular economies while promoting territorial cohesion, particularly in geoparks and protected areas [6,7,8].

The Arouca Declaration [9] formally recognized geotourism as a tool not only for appreciating geological heritage, but also for promoting territorial identity and safeguarding environmental integrity. It stressed that geotourism should enhance community pride, stimulate local economies, and respect ecological limits, while preserving cultural and natural resources for future generations. This broader conceptual approach highlights the role of geotourism in enhancing a sense of place, encouraging local engagement, and integrating cultural narratives with the geological history of a region [9,10,11].

Modern geotourism aspires to be rooted in geoethics, offering ethical guidelines for geoscientific activities and tourism practices and promoting responsible decision-making about Earth’s resources, landscapes, and heritage [12,13]. Recent studies have stressed that integrating geoethical principles into geotourism initiatives enhances environmental conservation, fosters territorial identity, ensures local community participation in management decisions, and mitigates risks such as geosite degradation and over-tourism [14,15,16]. Nevertheless, several case studies have shown that real-world practices do not always align with these principles, necessitating clear guidelines and community-driven management frameworks [17,18].

On islands such as Tinos, in the Aegean Sea, in Greece, where geological formations coexist with sacred landscapes and centuries-old cultural heritage, the synergy among geotourism, geoethics, and community values offers opportunities to develop sustainable identity-driven tourism models. These can preserve both tangible and intangible heritage, while supporting responsible economic development and promoting environmental awareness among both visitors and residents [8,19,20,21].

Geoeducation is pivotal in geotourism, as it links scientific knowledge with public awareness. It employs a multidisciplinary approach to convey geoscientific information to various audiences, including educators, students, and the general public [22,23,24]. Geoeducation fosters sustainable development by cultivating an understanding of Earth’s geology, resources, and dynamic systems through classroom instruction, experiential learning, museum exhibitions, and digital resources [25]. Furthermore, recent research highlights the value of integrating geoeducation into place-based learning models and heritage interpretation strategies, particularly in insular and peripheral regions [26,27]. Integrating geological and cultural heritage into geotourism initiatives enhances local identity and enriches visitor experiences, underscoring the significance of sustainable site management and participatory heritage conservation [28,29].

In places where cultures and landscapes are inextricably linked, the integration of geological and cultural narratives is particularly noteworthy. Gałka [30] underscores the significance of incorporating geoeducation with cultural tourism to foster compelling visitor experiences. The island of Tinos is distinguished by its unique geomorphological formations and rich cultural heritage. The island’s geological characteristics, influenced by natural forces and human intervention, offer a robust basis for educational programs that enrich the geotourism experience [31]. Tinos is also well-known for its religious sites and famous wine production, demonstrating the feasibility of combining geotourism with cultural and culinary components [32].

The goal of this research is to investigate the role of geotourism in the relationship between cultural traditions and geological heritage, with a focus on Tinos Island. The study’s goal is to assess the geotouristic and educational potential of key geosites, identify challenges, and propose solutions for sustainable development. The findings will contribute to broader discussions about how geotourism can promote environmental conservation, preserve natural and cultural assets, and support local businesses. Finally, the study encourages the widespread use of geotourism as a multidisciplinary approach that combines education, tourism, and sustainability, ensuring the long-term preservation and appreciation of Earth’s cultural and geological heritage.

With its unusual historical, cultural, and geological characteristics, Tinos, a Cycladic Island in the Aegean Sea, is a prime example of a geotourism site. Its geological relevance is mostly derived from its rich metamorphic geological history, which includes granitic intrusions, upper schists, and unusual marble deposits [33]. Apart from shaping the island’s natural landscape, these geological elements have also had a major impact on its cultural and economic growth, especially in traditional construction and marble manufacture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The island of Tinos belongs to the Cyclades Island complex and has an elongated shape and a NW-SE orientation, about 27 km long and about 12 km wide. It is in the southeast of Attica, it belongs to the group of the northern Cyclades (Figure 1), and it is the fourth largest island of the Cyclades, with an area of 194 km2 and a total coastline length of 114 km. There are many stories about the origin of its name, with the most prevalent being that it took it from the name of its first settler, Tinos. Tinos was the leader of a group of Ionians who arrived on the island around 1130 BC.

Figure 1.

The location of Tinos Island.

According to the most recent census conducted in 2011, Tinos has a population of 8,590 inhabitants. In the year 1856, the population of Tinos was recorded at 21,873. Over the course of fifty years, the population decreased by fifty percent, a trend linked to the booming construction industry in Athens, which led the famous Tinian marble artisans to relocate to that region.

The island is characterized by its many dovecotes, celebrated for their impressive architecture, alongside its 1,200 chapels. Tinos is the origin of numerous remarkable artists. The artistry of marble craftsmanship thrived on the island in a way that was unmatched elsewhere. The stunning natural beauty and intriguing architecture combine to form a truly unique and captivating landscape.

Tinos Island is situated within the geodynamically active South Aegean region, which belongs to the broader Hellenic Arc and Aegean microplate. Although the Aegean Sea is recognized as one of the most seismically active areas in Europe, the island of Tinos itself is characterized by relatively low to moderate seismicity compared to neighboring islands such as Santorini and Nisyros. According to the Unified Greek Earthquake Catalogue (1900–2010) and recent instrumental records [34,35], Tinos has not experienced significant or destructive earthquakes in historic or contemporary times. Furthermore, no historically documented tsunamis have affected the island directly, as confirmed by regional tsunami catalogs [36]. While natural hazards such as seismic activity and associated risks are important considerations in the broader South Aegean region, their direct impact on Tinos has remained limited. As such, the current study prioritizes the assessment of geocultural heritage for its educational and geotouristic potential, rather than for natural hazard risk management, acknowledging, however, that future integrated studies could expand upon this dimension.

Tinos displays diverse geomorphology. In general, its terrain is mountainous, dry, and rocky. The highest peak of the island is Tsiknias (729 m), is located at the NE end, and is identified by the appearance of the upper tectonic unit. The central part is dominated by the steep rock of Exombourgos (or Xoburgos), with a height of 641 m, on which stands the Ancient and Venetian city, whose upper part is by nature invulnerable because of the steepness on three sides. Most of the island shows morphological asymmetry from the NW end to the area where the granite appears. A mountainous axis along the island divides it into a relatively smoother northeast section compared to the southwest. These two sections into which the island is divided by the central ridge are uneven, with the NE section being larger [37].

2.1.1. Geological Setting

Tinos Island, part of the Cycladic archipelago in the Aegean Sea, presents a complex geological context shaped by tectonic processes related to the convergence of the Eurasian and African plates (Figure 2). The geological history of Tinos illustrates a complex narrative of subduction, ophiolite obduction, high-pressure metamorphism, and subsequent extensional processes. The sequential tectonic events demonstrate the island’s current geological structure, offering a profound analysis of the intricate geodynamic evolution of the Aegean region [38,39].

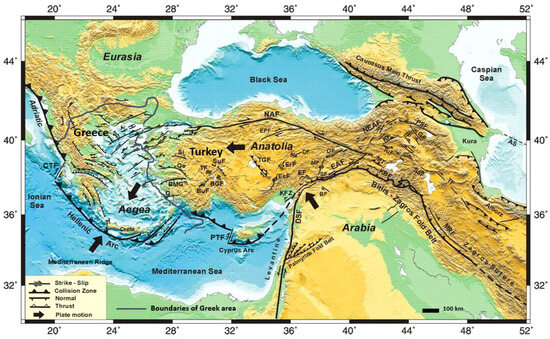

Figure 2.

Sketch map depicting the geodynamic setting of Greece, modified from [40].

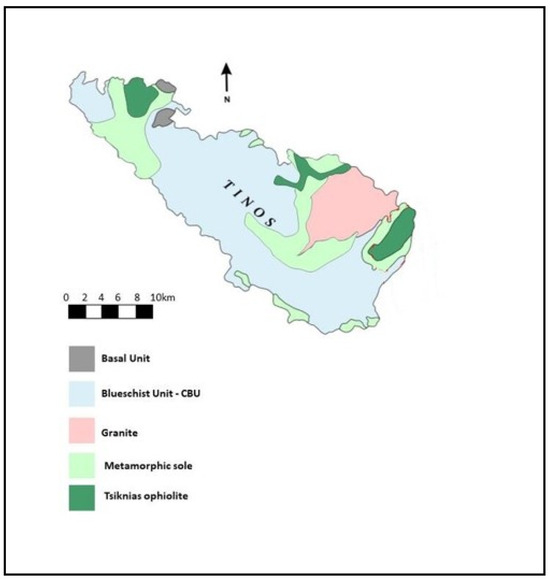

The geological composition of the island is organized into distinct tectonic units, each of which reflects a unique part of its geological history. The island belongs to the Atticocycladic geological mass and is primarily characterized by its complex metamorphic history and structural geology, which are deeply influenced by the tectonic activities within the Aegean region. This geological mass is marked by several distinct metamorphic units.

At the highest structural level is the Tsiknia ophiolite (Upper Unit), which represents remnants of oceanic crust and upper mantle emplaced on the continental margin of the Cyclades. This ophiolitic complex comprises a sequence of mafic and ultramafic rocks, such as serpentinized arzburgites, dunites, phyllite gabbroic, and plagioclase rocks, indicative of the Moho transition zone. The Tsiknia ophiolite is interpreted as a thrust sheet emplaced during the Late Cretaceous, marking a major phase of oceanic crustal impingement in the area [33,41].

Beneath the ophiolite, the Cycladic Blueschist Unit (CBU) is noted for its high-pressure metamorphism, containing marbles, calcschists, and a variety of metasediments, indicative of the intense subduction processes that have shaped the region. Peak metamorphic conditions attained pressures of roughly 22–26 kbar and temperatures ranging from 490–520 °C, which correlate with burial depths of 60–80 km. The exhumation of the CBU involved intricate tectonic processes, such as top-to-SW thrusting and top-to-NE normal-sense shear, which enabled the ascent of these rocks to the surface [41,42,43,44].

At the lowest stratigraphic level, the Basal Unit features a diverse collection of metamorphic carbonate rocks. Together, these units showcase a dynamic tectonic environment with multiple detachments, highlighting the geological complexity and the ongoing metamorphic processes that define the geology of Tinos within the Cyclades complex [45]. Tinos contains notable granitic intrusions, particularly S-type granites, resulting from crustal melting processes. The intrusions are linked to extensional tectonics and normal faulting events that transpired during the Miocene epoch. Geochemical analyses suggest that these granites originated from the partial melting of metasedimentary rocks, which contributes to the island’s diverse lithological assemblage [46,47].

Mapping and analysis of these geological units (Figure 3), based on fieldwork and historical data, provide a detailed view of the island’s geological framework, offering insights into the Cycladic region’s tectonic and metamorphic history. This intricate geological setting not only informs us about past geodynamic conditions, but also helps predict future geological developments in this seismically active region.

Figure 3.

Simplified geological map of Tinos Island (modified from [48,49]).

2.1.2. Cultural Heritage

Tinos Island is a distinctive repository of Greece’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage. The island’s unique cultural identity has been influenced by a variety of factors, including age-old folk practices, marble craftsmanship, traditional architecture, and religious customs.

Greece’s most significant Orthodox pilgrimage site is the church of Panagia Evangelistria, which is the focal point of Tinos’ religious heritage. The construction of the church was inspired by a miraculous Virgin Mary icon that was discovered in the 1820s, which was believed to possess healing properties. The Assumption of the Virgin Mary is commemorated annually by thousands of pilgrims, with a particular emphasis on 15 August.

Tinos boasts an extraordinary architectural and folkloric heritage, in addition to its spiritual significance. The Venetian era is the origin of the island’s more than 1000 dovecotes, which are intricately decorated stone structures that serve both agricultural and aesthetic purposes in the environment [50]. Additionally, the island’s ongoing marble sculpting legacy is evident in the well-known marble sculpted lintels, bell towers, and fountains of towns such as Pyrgos, Kardiani, Volax, and Isternia.

Marble carving is a significant component of the cultural identity of Tinos and was officially recognized by UNESCO as a component of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2015. The Tinos School of Fine Arts and the Museum of Marble Crafts are in the village of Pyrgos, which is the epicenter of this tradition. These institutions preserve and promote the skills of generations of artisans whose works adorn not only the island, but also prominent monuments in Athens, including the National Library and the Academy of Athens [51].

Tinos preserves active intangible cultural practices in addition to its historical and architectural legacy. Village life is enlivened by a variety of religious celebrations (festivals), traditional dances, and musical performances, especially during the summer. The annual Tinos Festival reinforces the community’s connection to its traditions and offers new opportunities for modern cultural expression by showcasing the island’s cultural vibrancy through theatrical performances, art displays, and culinary events.

Tinos boasts an extensive archaeological heritage. The sanctuary of Poseidon and Amphitrite in Kionia, a notable ancient religious center, is a testament to the island’s significant role in ancient Cycladic religious practices [52]. Exombourgos mountain, with the Exombourgo acropolis situated at its summit, the island’s fortified ancient and medieval acropolis, is also noteworthy for its preservation of remnants from the prehistoric, classical, and Venetian eras, which contributes to a multifaceted narrative of Tinos’ historical and cultural development.

This has resulted in Tinos’ cultural legacy, which encompasses religious monuments, traditional architecture, crafts, folk customs, and archaeological remnants, not only narrating the island’s rich history, but also preserving its contemporary identity, thereby fostering both national cultural tourism and regional pride.

2.1.3. Selection of Geosites for Comprehensive Assessment

Identifying appropriate geosites is fundamental to preserving and interpreting the unique geological, cultural, and historical characteristics of the island of Tinos. Tinos has exceptional geodiversity, with granitic intrusions, metamorphic formations, and characteristic marble and ophite deposits, which have significantly shaped the traditions, architecture, and livelihood of local communities. The six geosites (Figure 4, Table 1) included in this study cover a variety of types. GS.T1 is a geological–industrial heritage site near Koumelas village, while GS.T2 and GS.T3 are coastal and mountainous geomorphological sites in southwestern Tinos. GS.T4 and GS.T5 represent spheroidal disintegration formsin the Volax-Livada area, while GS.T6 combines geological and archaeological heritage on the Exombourgo hill.

Figure 4.

Satellite map of the island of Tinos, indicating the selected geosites.

Table 1.

Geosites of Tinos Island.

GS.T1—Ophite Stone Quarry

Type: Ancient quarry site for ophitic-textured mafic rocks (meta-diabase/metabasalt).

Location: Near the settlement of Koumela, northern Tinos Island, within the metamorphic Cycladic Blueschist Unit.

The ophite stone quarry on Tinos Island is an important geological and cultural location in the Cyclades. The unique ophitic texture, a local designation for greenish, fine-to-medium-grained igneous rocks (Figure 5a–d) like diabase and similar lithologies [41,49], is characterized by pyroxene crystals surrounding plagioclase laths. The island’s varied lithological composition comprises serpentinized ultramafic rocks, ophiolitic remnants, ophicalcites, and remnants of a previous oceanic lithosphere, within a subduction-related tectonic setting in the Aegean back-arc system [53].

Figure 5.

(a) The ophite stone quarry; (b) the artificial lake in the area of the quarry; (c) inflow of water into the lake during the winter period; (d) artistic performance in the area of the quarry.

Ophite has long been valued for its durability and aesthetic appeal in Cycladic architecture [54]. It continues to be used in vernacular constructions, where local geology shapes cultural landscapes. Studies of Tinos’ marble quarries and other industrial extractions have highlighted the dynamic relationship between geological resources and human activity [55].

Geologically, the ophite quarries reveal insights into the region’s tectonic, metamorphic, and magmatic evolution. Research by Mavrogonatos et al. [53] on the Upper Tectonic Unit’s ophicalcites and Lamont et al. [49] on the Tsiknias Ophiolite document the complex tectonometamorphic cycles of oceanic crust formation, obduction, and metamorphism throughout the Alpine orogeny.

In Tinos there is a place referred to as the “Green Quarry”, described as the “largest natural marble pool in the Mediterranean”. This “Green Quarry” is not a natural lake in the sense of a geological formation created without human intervention, but it is an abandoned quarry for the extraction of green Tinian marble (ophite stone), which has been filled with water, creating an impressive “natural pool” with marble walls and characteristic turquoise waters.

In the northern part of the island, near Koumela village (Figure 4), there is the Koumela quarry, one of the most characteristic quarries of green Tinian marble (ophite stone). This imposing quarry, hidden at the bottom of a natural cove, is known for the layers of greenish marble that meet the sea water. In fact, its landscape has been used as a backdrop for musical and theatrical performances because of its imposing and unique beauty.

Today, including the ophite quarry in Tinos’ geosite inventory enhances its scientific and cultural significance, making it an important site of natural and historical interest. Its global role as a decorative stone exported to several European countries creates opportunities for sustainable geotourism, geoeducation, and heritage promotion. However, the increasing demand and potential overexploitation of this georesource give rise to geoethical concerns around environmental impacts and cultural implications when substituting indigenous materials. Addressing these through geoeducational initiatives could foster public awareness of sustainable natural stone use, heritage conservation, and responsible management.

GS.T2—Tafoni

Type: Cavernous weathering forms on granitic outcrops.

Location: Western slopes of Mount Pateles (near Kardiani region and overlooking the southwest coastline), at elevations ranging from sea level up to approximately 400 m.

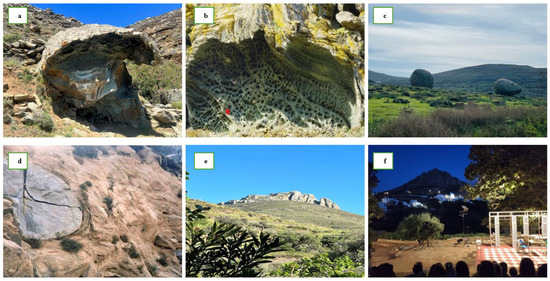

Tafoni are cavernous weathering forms resembling honeycombs or small caves [56] (Figure 6a). On Tinos Island, these features predominantly occur on granitic outcrops, especially on the southeastern slopes and coastal sectors of Livada and the hinterland of Falatados village. Their formation depends on rock mineralogy, microclimate, and salt weathering processes, strongly influenced by the island’s Mediterranean climate [57]. Tinos’ granitic rocks, rich in feldspar and quartz, undergo chemical weathering enhanced by physical processes like thermal expansion and contraction. Microfractures and zones of increased porosity allow moisture infiltration, while the rapid wetting and drying cycles characteristic of the region facilitate salt accumulation within pore spaces. Subsequent salt crystallization generates pressures that widen fractures and detach mineral grains, leading to the progressive enlargement of cavities [58,59].

Figure 6.

(a) Tafoni; (b) alveoles; (c) tors in Volax; (d) core stones; (e) Exombourgo; (f) evening theater performance with the view of Exombourgo’s plutonite.

Cavities typically initiate at pre-existing weaknesses such as microcracks or bedding planes and enlarge over time. The process is further accelerated by capillary action, drawing saline moisture to the rock’s exterior, where evaporation concentrates salts, causing surface disintegration [60].

On Tinos, tafoni occur in a range of sizes, from millimeter-scale alveoles to cavities exceeding 2 m in diameter. Particularly large and well-formed tafoni are observed at the outlets of the Livada valley and on the granite slopes south of Falatados, often appearing alongside other granite landforms such as tors and core stones [57].

The Kardiani region, situated on the western slopes of Mount Pateles near Exombourgo and overlooking the southwest coastline of Tinos Island, features a distinctive landscape of granitic outcrops and boulders where tafoni are well-developed. These weathering cavities are particularly evident on granite blocks located above and around Kardiani village, along the coastal granite exposures between Kardiani and Agios Romanos, as well as in abandoned quarry sites and residual tors scattered nearby. The tafoni typically form on granite surfaces that are sheltered from direct precipitation yet exposed to salt-laden winds and marine aerosols, as the village directly faces the open Aegean Sea. Their development results from a combination of salt weathering, thermal stress, and granular disintegration processes acting on the granitic bedrock. Geomorphologically and aesthetically, the tafoni of Kardiani are notable, as they occur on granitic outcrops positioned between rugged sea cliffs and mountainous terrain. The granites in this area belong to the Tinos Pluton, dated to approximately 14–11 Ma [61,62], and the unique microclimate of the western slopes—characterized by persistent meltemi winds and high levels of marine aerosol input—further promotes tafoni formation.

Tafoni are widespread across the Mediterranean—in Sardinia, Corsica, Tuscany, southern Spain, and the Aegean Islands of Thassos, Naxos, Tinos, and Ios [31,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. The term “tafoni” was introduced by Penck [76] to describe Corsican granite weathering forms. Archaeological finds on Tinos suggest that human fascination with these features dates back centuries [69].

The tafoni sites hold notable scientific and geoeducational significance, providing accessible examples for demonstrating the interplay between lithology, climate, and weathering processes in coastal and upland granite terrains of the Aegean. Additionally, their aesthetic appeal and geomorphological rarity contribute to their value as geosites within Tinos’ broader geological heritage inventory [56].

GS.T3—Alveoles

Type: Microcavernous weathering forms (alveolar weathering).

Location: Kardiani Area, at elevations between 50–350 m.

Alveoles are similar cavernous weathering features, though smaller than 0.5 m, typically developing on shale surfaces (Figure 6b) [63]. They represent an early stage in the development of larger cavernous forms such as tafoni and are characteristic of granite terrains subject to intense physical, chemical, and biological weathering processes. Alveoles occur predominantly on weathered shale surfaces within the metamorphic basement, as well as on fine-grained granite and granodiorite outcrops, where structural weaknesses such as joints, fractures, and bedding planes facilitate their formation. The mineralogical composition of these rocks, particularly their content of clay minerals, feldspars, and iron oxides, makes them especially susceptible to granular disintegration and chemical alteration.

On Tinos Island, alveoles predominantly form on the island’s coarse-grained granites in coastal and upland areas, particularly around Livada, Volax, and Agapi, where massive granitic outcrops are abundant. The Kardiani region also exhibits well-developed alveolar weathering features on its granitic surfaces. These small, honeycomb-like cavities occur in clusters on weathered granite blocks both above Kardiani village and along the coastal granite exposures between Kardiani and Agios Romanos.

The formation of alveoles on Tinos is attributed to multiple interacting factors. The semi-arid Mediterranean climate, characterized by seasonal alternation of wet and dry periods, promotes salt crystallization within rock pores, particularly in coastal and near-coastal areas. Sea spray, transported inland by prevailing winds, deposits saline aerosols onto rock surfaces. As moisture evaporates, salt crystals grow within the pore spaces, exerting physical pressure that disaggregates mineral grains. At the same time, chemical weathering processes such as the decomposition of feldspars and the hydration of clay minerals weaken the rock matrix, making the surface more friable. These mechanisms enlarge pre-existing microcavities or irregularities in the rock preferentially, gradually forming alveoles through successive cycles of wetting, drying, and salt crystallization [56].

Unlike larger tafoni, which have occasionally served as natural shelters and have therefore been directly exploited for human use, alveoles have not. However, their occurrence contributes to the distinctive stone landscapes of the Cyclades. Their characteristic pitted surfaces have historically been recognized by local communities as natural manifestations of stone decay, forming part of the vernacular landscape aesthetic and local environmental knowledge.

From a geoheritage perspective, alveoles possess considerable scientific and educational value. Studying them offers insights into the interplay among lithology, climate, and geomorphic processes in semi-arid island environments. They present opportunities for public education on physical and chemical weathering mechanisms, particularly when integrated into geoeducational trails or interpretive signage alongside associated tafoni formations. Given their fragile nature and susceptibility to human-induced damage, including alveoles in Tinos’ geosite inventory highlights the importance of protecting micro-scale geomorphological features within a sustainable geotourism and geoheritage management framework.

Similar alveolar formations have been documented in other parts of the Mediterranean, including Corsica, Sardinia, southern Spain, and on other Aegean islands such as Naxos and Ios [31,58,65,72,75], reflecting the widespread occurrence of these features in granitic and fine-grained rock formations exposed to Mediterranean climatic conditions. The presence of these formations on Tinos enriches the island’s geomorphological diversity, enhancing its value as a natural laboratory for studying weathering processes and coastal landform evolution.

GS.T4—Tors (Area of Volax)

Type: Granite landforms—spheroidal weathering residuals (tors).

Location: Central and southern Tinos Island, predominantly around the village of Volax and the Falatados–Steni area, at elevations ranging from 400 m to 450 m.

Tors are residual rock outcrops formed by differential weathering and erosion of granitic bedrock, resulting in clusters of rounded or blocky boulders often perched on or near their parent rock (Figure 6c). On Tinos Island, these characteristic granite landforms are especially concentrated in the area surrounding the village of Volax, a geologically and culturally significant landscape known for its exceptional spheroidal granite boulders scattered across a flattened erosional surface [77].

The formation of tors in Tinos is closely linked to spheroidal disintegration processes occurring in massive granitic rocks. Chemical weathering along joint systems and fractures penetrates the granite, rounding off angular edges and progressively isolating core stones that remain exposed as tors following the removal of the surrounding weathered mantle [78]. The granite pluton of Tinos, emplaced during the Miocene, exhibits jointed structures and mineralogical heterogeneity, which promotes localized weathering susceptibility [79].

The geomorphic evolution of the Volax tors has been further influenced by the semi-arid Mediterranean climate of the Cyclades, characterized by alternating wet and dry periods that accentuate physical and chemical weathering mechanisms. The granitic boulders of Volax range in diameter from 1.5 m to 3.5 m and frequently display additional microfeatures such as tafoni and alveoles, indicating prolonged surface weathering [56].

These tors contribute significantly to the geomorphological and geoheritage value of Tinos, serving as classic examples of granite landform evolution in insular Aegean settings and offering important educational opportunities in physical geography, geomorphology, and landscape interpretation.

GS.T5—Core Stones (Falatados–Volax–Livada Area)

Type: Granite weathering landforms (core stones).

Location: Falatados–Volax–Livada Area, central and eastern Tinos Island, Cyclades, Greece. Specifically concentrated in the Volax valley, between the villages of Falatados, Volax, and Livada, at elevations ranging from 40 m to 430 m a.s.l.

The core stones of Tinos Island are striking geomorphological features resulting from spheroidal disintegration processes in the island’s extensive granitic terrain. These rounded or sub-rounded blocks of granite form below the surface, isolated within a weathered mantle, and are later revealed through gradual erosion and removal of the surrounding decomposed material (Figure 6d) [78,79]. In contrast to tors—which remain attached to the parent rock—core stones are free-standing boulders, typically concentrated within deeply weathered granite zones.

On Tinos, significant concentrations of core stones occur in the central granite massif, particularly around the villages of Falatados and Volax and in the Livada valley. These localities lie at elevations ranging from 40 m to 430 m, with higher frequencies recorded on flat to gently undulating surfaces at mid-elevations [77]. Their spherical to ellipsoidal morphology, often measuring 1.5 to 3 m in diameter, is a product of concentric weathering, where chemical alteration progresses inward along fractures and joints, preferentially rounding the block edges [56,80].

Environmental factors such as the Mediterranean climate, the fluctuating humidity, and the influence of salt-bearing sea spray enhance chemical weathering, particularly at lower altitudes near the coast [81]. Sea-salt aerosols are transported inland by prevailing winds, promoting granular disintegration, especially where micro-fractures and joint systems are dense. This mechanism, coupled with differential weathering rates along joint planes, produces isolated core stones, frequently found lying on weathered granite surfaces or partially embedded within soil cover [82].

These landforms offer insights into the paleoclimatic and geomorphological evolution of Tinos, while also contributing to the island’s geoheritage significance. The visual impact and density of these boulder fields have historically inspired local folklore and are integrated into the region’s cultural landscape, particularly around the Volax amphitheatrical valley, a unique granite field scattered with spheroidal boulders of remarkable size and preservation [77,82].

GS.T6—Exombourgo Granitic Massif

Type: Plutonic igneous landform (granitic pluton).

Location: Central-southern Tinos Island, Cyclades, Greece. Centered at Exombourgo hill (c. 640 m elevation), approximately 4 km southeast of Tinos Town (Chora).

The Exombourgo granitic residual massif represents one of the most prominent geomorphological and geological landmarks of Tinos Island, rising sharply to an altitude of 530 m above the central part of the island (Figure 6e,f). It forms part of the Tinos Pluton, an elongated granitic intrusion of Oligocene–Miocene age (16–25 Ma) that was emplaced into a pre-existing sequence of schists and marbles during the post-orogenic extensional phase of the Alpine Orogeny in the Aegean [61,62].

Lithologically, the Tinos Pluton consists primarily of granodiorite and subordinate leucogranite, with the granodiorite forming the main body of the intrusion and the leucogranite occurring along the margins as veins, dykes, and infiltrations into the surrounding metamorphic rocks [41,44]. Contact between the pluton and the surrounding country rock is marked by intense contact metamorphism, producing skarns and calc-silicate hornfelses, visible around Exombourgo [41,83]. The pluton was rapidly emplaced at shallow crustal levels, with its sharp, isolated relief a consequence of differential erosion of the surrounding, less-resistant, metamorphic rocks.

From a geomorphological perspective, Exombourgo is a classic example of a granitic residual inselberg—a steep-sided, dome-shaped hill or mountain of resistant rock rising above a more subdued erosion surface [78,79]. Its rugged slopes and prominent form dominate the Tinos skyline, while its geological composition offers valuable insights into Aegean post-orogenic magmatism, crustal melting processes, and regional tectonics associated with the back-arc extension of the Hellenic subduction zone [61,83].

Historically, Exombourgo has been a locus of human occupation and strategic significance since prehistoric times. Archaeological investigations have uncovered evidence of Copper Age settlements, a Geometric-period sanctuary of Demeter, and continuous habitation into the Classical and Hellenistic periods [84]. In the medieval period, the Byzantines fortified the site, followed by the Venetians, who constructed the Castello di Santa Elena, a defensive stronghold that served as the administrative center of Tinos until its fall to the Ottomans in 1715 [84].

Today, Exombourgo is not only a site of geological and geomorphological importance, but also a key element of Tinos’ cultural and archaeological heritage, making it an essential component of geotourism and geoeducation initiatives on the island.

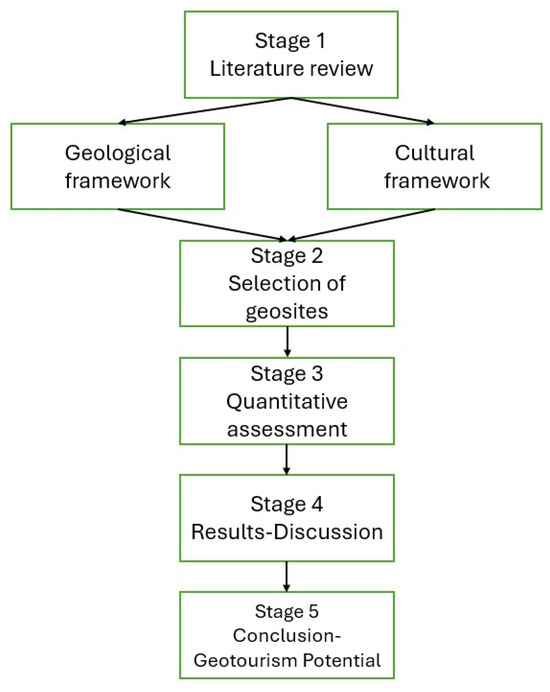

2.2. Quantitative Assessment

For the present study, the following methodology was adopted, as illustrated in the flowchart (Figure 7). Initially, a comprehensive literature review was conducted, followed by a detailed geological study of the area. In parallel, the cultural characteristics of the region were examined to establish a holistic understanding of its geocultural landscape. In the next phase, a selection of geosites was carried out based on their geological, educational, and cultural relevance. These geosites were then subjected to a structured quantitative evaluation. Subsequently, the results were analyzed and discussed to identify key strengths and limitations. The study concludes with a synthesis of findings, emphasizing the significant geotouristic potential of the Tinos Island geosites.

Figure 7.

Flowchart followed in this paper.

Natural landmarks, such as caves, gorges, river valleys, and paleontological sites, are crucial for geotourism planning and management. Researchers have developed criteria for determining the intrinsic value of different types of geosites, considering scientific, educational, aesthetic, and economic aspects [2,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94]. Geosite assessment methods can be categorized into qualitative and quantitative approaches. Qualitative assessment methods rely on descriptive site analysis without assigning specific scores or points, while quantitative methods involve assigning specific point values to different criteria. Quantitative assessment forms the cornerstone of the decision-making framework for geotourism development [86,87,88,91,95,96,97,98,99,100,101]. However, there is no universally accepted approach within the geological community, due to the focus on evaluation criteria varying based on researchers’ interests and perspectives.

The GEOAM (Geoeducational Potential Assessment Method) is a systematic evaluation framework designed to assess the educational value, conservation status, and overall potential of geosites [102]. Incorporating a multidimensional approach, GEOAM employs a set of specific criteria to conduct a thorough assessment of geological features, accessibility, educational resources, visitor experience, and conservation considerations. Through the assignment of scores to individual criteria and subsequent computation of an overall assessment, the method offers a quantifiable gauge of a geosite’s potential for geoeducation [103]. Notably, GEOAM’s flexible structure allows adaptation to diverse geographical contexts and varying site characteristics, making it a versatile tool for educators, researchers, and policymakers striving to identify and enhance the educational significance and sustainable management of geosites [102]. This approach considers eight distinct criteria, each supported by its associated subcriteria. These criteria form the core framework for our data evaluation and play a pivotal role in assessing the geoeducational potential of geosites.

The eight criteria are as follows:

- Site Management and Visitor Experience (SMVE) evaluates the quality of site management and the overall visitor experience. It delves into aspects such as site accessibility, signage, staff knowledge, visitor facilities, site maintenance, safety, and security.

- Natural Resource Management (NRM) assesses how well the geosite manages its natural resources. This includes the conservation of biodiversity, preservation of eco-systems, sustainable resource use, pollution prevention and control, and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

- Environmental Education and Interpretation (EEI) focuses on the presence of interpretive signage or exhibits, the availability of trained interpretive staff or volunteers, the integration of environmental education and interpretation, the inclusion of interactive activities, and the incorporation of environmentally friendly practices.

- Cultural and Historical Significance (CHS) evaluates the historical and cultural value of the geosite. This includes aspects like historical significance, cultural significance, interpretation, cultural diversity, and inclusivity.

- Geoethics (GE) assesses ethical aspects related to geosite. This criterion includes considerations for environmental impact, cultural heritage preservation, social responsibility, transparency, and professional conduct.

- Economic Viability (EV) examines the economic aspects of the geosite. It includes evaluating tourist revenue potential, local economic impact, sustainability of economic benefits, cost-effectiveness of management, and innovative economic models.

- Community Involvement and Engagement (CIE) looks at how the geosite involves and engages the local community. It includes aspects like stakeholder participation, cultural sensitivity, community benefits, outreach, and communication.

- Sustainable Development (SD) assesses how the geosite contributes to sustainable development. This includes resource efficiency, waste management, biodiversity conservation, social and economic impacts, climate change adaptation, and cultural heritage preservation.

For each criterion, a specific weighting factor is applied to ascertain the ultimate score. Subsequently, the final score is determined using the provided formula:

Final score: [(SMVE × 0.10) + (NRM × 0.10) + (EEI × 0.30) + (CHS × 0.10) + (GE × 0.20) + (EV × 0.05) + (CIE × 0.05) + (SD × 0.10)]

It is noteworthy to mention that the scoring system allocates values ranging from 1 to 5 for the subcriteria. Consequently, considering the formula for computing the ultimate score, a five-point scale is established for categorizing and determining the final score. This classification of the final score as “High implementation” (HI), “Moderate implementation” (MI), or other similar categories provides a quick summary of the level of success in integrating the geoeducational and sustainable principles into the geosite’s management, visitor experience, resource management, and other relevant aspects (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of the final GEOAM score.

The scoring process in our research assessment was designed to maintain objectivity through several key steps. Firstly, it involved a team of expert assessors who were well-versed in the relevant criteria and the sites being evaluated. These assessors followed clear and detailed scoring guidelines that outline how each criterion and subcriterion should be assessed and define different score levels. Training has been provided to ensure assessors understand and can consistently apply these guidelines. Assessments were conducted independently to minimize bias, with each assessor evaluating sites separately. After individual assessments, a review process checked for scoring consistency, and any significant discrepancies were resolved through discussions or revisions. Transparency was maintained throughout the process, documenting how scores were determined and including relevant comments or justifications. Finally, many research papers and assessments were subjected to peer review by other experts in the field to ensure the methodology and findings are sound and objective.

3. Results

Intricate evaluation of the criteria using GEOAM revealed the following results (Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10):

Table 3.

Scoring system for the geosites of Tinos based on SMVE.

Table 4.

Scoring system for the geosites of Tinos based on NRM.

Table 5.

Scoring system for the geosites of Tinos based on EEI.

Table 6.

Scoring system for the geosites of Tinos based on CHS.

Table 7.

Scoring system for the geosites of Tinos based on GE.

Table 8.

Scoring system for the geosites of Tinos based on EV.

Table 9.

Scoring system for the geosites of Tinos based on CIE.

Table 10.

Scoring system for the geosites of Tinos based on SD.

The evaluation utilized a weighted scoring mechanism that considers the varying significance of each criterion, offering a comprehensive perspective on the strengths and potential areas for improvement across the sites (Table 11).

Table 11.

Scoring system for the geosites of Tinos and final scores.

In accordance with the observations from Table 10, all of the geosites are of high importance, as none have a low score. In fact, three out of six show high implementation (HI), as illustrated in the characterization of the final score. More specifically, GS.T4 shows the highest score, of 3.30 (Table 11). That creates great potential for further steps, to achieve more community initiatives for its rational management. Furthermore, GS.T2 and GS.T6 has a similar geoheritage dynamic and could be subjected to collective management. In this way, the local community can capture the benefits of their geosites under sustainable development.

On the other hand, GS.T1, GS.T3, and GS.T5 demonstrate the lowest scores, of 2.76, 2.44, and 2.34, respectively. This point reflects the absence of geoenvironmental activities and actions that will promote the promotion of these geosites. This can also be seen from the fact that the third main axis EEI (Environmental Education and Interpretation) received the lowest scores for all geosites.

4. Discussion

The comprehensive assessment we conducted offers valuable insights into the current management status and future potential of Tinos Island’s geosites, based on a multicriterion framework incorporating Site Management and Visitor Experience (SMVE), Natural Resource Management (NRM), Environmental Education and Interpretation (EEI), Cultural and Historical Significance (CHS), Geoethics (GE), Economic Viability (EV), Community Involvement and Engagement (CIE), and Sustainable Development (SD).

The final weighted scores (Table 11) revealed a relatively consistent pattern among the evaluated geosites, with GS.T4 (3.30) ranking highest, followed by GS.T2 (3.10) and GS.T6 (3.04). Conversely, GS.T5 (2.34) and GS.T3 (2.44) received lower scores, indicating areas requiring targeted improvements.

The highest mean scores across all sites—particularly at GS.T4 and GS.T6—were recorded for the criteria of Cultural and Historical Significance (CHS) and Geoethics (GE). This outcome reflects the rich cultural landscape of the island, where natural and cultural features are closely intertwined [104]. Tinos’ longstanding traditions in religion, craftsmanship, and agriculture, historically linked to its geomorphological characteristics, support previous studies suggesting that integrating cultural narratives enhances the identity and appeal of geosites [87,96].

Geoethics also scored consistently high, indicating awareness of environmental impacts, social responsibility, and professional integrity in site management––a critical aspect for small island communities, where geoethical values can guide equitable tourism development and culturally sensitive resource use [97].

In contrast, Environmental Education and Interpretation (EEI) was the weakest-performing criterion at all sites, averaging between 2.00 and 2.40. This points to a general absence of interactive educational initiatives, trained staff, and interpretive infrastructure. Such deficiencies reduce the sites’ capacity to serve as effective learning tools and compromise their ability to raise awareness about geoconservation values [98].

Moreover, the climate change adaptation subcriterion consistently received the lowest possible scores (1 or 2) across all sites, highlighting a significant gap in area management systems. The absence of proactive adaptation planning threatens the long-term preservation of both natural and cultural assets, especially given the vulnerability of island ecosystems to climate-related hazards [99].

Positive results were also recorded for Community Involvement and Engagement (CIE) and Economic Viability (EV), particularly at GS.T4, GS.T2, and GS.T6. These sites demonstrated strong local participation and tangible economic benefits, confirming the established view that community-driven geosites tend to achieve better outcomes in visitor experience and sustainable area management [102,103].

The results indicate that, while cultural values are appropriately integrated into site narratives and management practices, they are not adequately reflected in environmental education initiatives and interpretive tools. For instance, GS.T4 combines relatively low EEI scores with high CHS and GE values—a trend also observed in other Mediterranean geotourism destinations [100]. This inconsistency limits visitors’ ability to fully appreciate the geological context supporting Tinos’ cultural landscapes, an issue already identified as a barrier to effective geoconservation promotion [71].

A promising opportunity lies in developing an integrated geoeducation strategy focusing on the island’s longstanding cultural relationship with its geological environment—particularly through themes such as traditional stone craftsmanship, quarrying heritage, and the symbolic significance of local stones like the Tinos ophite at both local and international levels. This unified narrative could connect diverse geoheritage elements, illustrating how geological resources shaped settlement patterns, architectural styles, religious practices, and trade relations over centuries.

The UNESCO Global Geopark of the Apuan Alps in Italy offers a pertinent model, where geoheritage promotion is actively tied to the region’s historic marble quarrying and cultural identity [105]. A comparable approach could be effectively adapted for Tinos, where the rich tradition of stone craftsmanship—including the extraction and artistic use of ophite, marble, and other local rocks—forms an integral part of the island’s cultural and economic history. Integrating this quarrying heritage into geoheritage promotion strategies would not only emphasize the scientific significance of geosites, but also celebrate their cultural narratives, offering opportunities for interpretive trails, community-led storytelling, and exhibitions on stone craftsmanship. Such initiatives could position geodiversity not as an isolated feature, but as a product of continuous interaction with local history, human activity, and landscape transformations over centuries [106]. This approach highlights geoheritage within a broader cultural framework while promoting visitor engagement and local community involvement through sustainable tourism [101].

To address the significant educational and interpretive deficiencies identified, priority should be given to installing interpretive signage, interactive exhibits, and guided educational programs conveying the geological significance of each geosite to both visitors and residents. These initiatives should follow international best practices for geosite interpretation, emphasizing accessibility, clarity, and audience engagement. However, recent research increasingly supports diversified interpretation strategies beyond static signage and conventional guided tours [98,102]. Co-creating educational material with local communities—incorporating oral histories, traditional knowledge, artisanal practices, and storytelling—could enrich site narratives with culturally embedded content while fostering local ownership and stewardship.

Additional interpretation tools could include augmented reality (AR) applications for mobile devices, temporary or permanent geoheritage exhibitions in local museums, and practical workshops on traditional stone-carving and quarrying techniques. Educational games for younger audiences, digital storytelling programs, and on-site art installations using local stones have also been successfully employed in other geoparks to broaden visitor engagement and interpretation. These approaches offer participatory, immersive, and multisensory experiences aligned with geoethical principles, raising environmental awareness and supporting the sustainable growth of geotourism through active community participation.

It is worth noting that cooperative enterprise among the local community, stakeholders, and policymakers is necessary. Only in this case will it be possible to take a holistic approach to enhance the geoheritage value of such areas. In this way, the cultural dynamics of this region, which are threatened according to a study by a European body [92], will be ensured at the same time. It seems that geoeducation through geoeducational activities or recreation can contribute constructively, benefiting society economically, socially, and environmentally. It should also be emphasized that the promotion of organized geoeducational activities can cultivate a geoethical perception and life attitude in those concerned. Therefore, in this manner, which is closer to the principles of sustainable development, a society can exist completely in harmony with the natural environment.

Finally, considering the increasing risks posed by climate change, it is essential to establish site-specific adaptation strategies appropriate to each geosite’s environmental conditions. These strategies should address critical deficiencies threatening the infrastructure and ecological integrity of small island sites, including sea-level rise, coastal erosion, and the intensification of extreme weather events.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the necessity of adopting a holistic, place-based approach to geotourism on Tinos Island, integrating the island’s rich geological heritage with its cultural and intangible assets within the framework of sustainable development. The geosite assessments confirm that several locations demonstrate considerable potential for geoeducational and geotouristic applications. However, the results also reveal critical challenges, including deficiencies in site infrastructure, limited stakeholder engagement, and an absence of coherent management strategies grounded in geoethical principles.

To effectively capitalize on Tinos’ geoheritage, the establishment of a collaborative management framework is essential, incorporating local communities, policymakers, tourism stakeholders, and scientific experts. Such a framework should prioritize the conservation of key geosites, the advancement of geoeducation initiatives, and the promotion of culturally sensitive, community-led tourism activities. These efforts would not only enhance the visitor experience, but also safeguard the island’s natural and cultural resources for future generations.

The findings reaffirm the growing consensus that geotourism, when designed and managed within a geoethical and sustainable development framework, can contribute meaningfully to the resilience of both natural landscapes and local communities. Future research should focus on monitoring the long-term socio-economic and environmental impacts of geotourism interventions on Tinos and on evaluating their effectiveness in fostering environmental awareness and stewardship among residents and visitors alike.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z. and H.D.; methodology, G.Z.; formal analysis, G.Z.; investigation, G.Z., S.K. and H.D.; resources, G.Z.; data curation, G.Z. and S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, G.Z. and H.D.; supervision, H.D.; project administration, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the local authorities, residents, and cultural associations of Tinos Island for their valuable insights and support during the fieldwork phase of this study. Special thanks are extended to the University of the Aegean for providing access to geospatial data and logistical assistance. The authors also acknowledge the constructive comments of the anonymous reviewers, which greatly contributed to improving the quality and clarity of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Karampela, S.; Papazoglou, C.; Kizos, T.; Spilanis, I. Sustainable Local Development on Aegean Islands: A Meta-Analysis of the Literature. Island Stud. J. 2017, 12, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalíková, L. Assessing Geotourism Resources on a Local Level: A Case Study from Southern Moravia (Czech Republic). Resources 2019, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Kim, C.; Paek, C. Landform Diversity Supporting the Geotourism Attractiveness of Mt. Kumgang. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Valverde, M.E.; Quesada-Román, A. Worldwide Trends in Methods and Resources Promoting Geoconservation, Geotourism, and Geoheritage. Geosciences 2023, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, L.; Mandal, U.K.; Karmakar, M.; Banerjee, M.; Ghosh, D. Geomorphosite Evaluation for Geotourism Development Using Geosite Assessment Model (GAM): A Study from a Proterozoic Terrain in Eastern India. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2023, 11, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumanapala, D.; Wolf, I.D. Introducing Geotourism to Diversify the Visitor Experience in Protected Areas and Reduce Impacts on Overused Attractions. Land 2022, 11, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pedrosa, R.M.; Serrano, E. Geotourism and Local Development in Rural Areas: Geomorphosites as Geotouristic Resources in Sierras de la Paramera y Serrota, Spain. Land 2025, 14, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Dowling, R. Geotourism and Geoparks—A Tool for Geoconservation and Rural Development in Vulnerable Environments: A Case Study from Iceland. Geoheritage 2014, 6, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouca Declaration. International Declaration on Geotourism; Global Geoparks Network Archives. 2011. Available online: https://globalgeoparksnetwork.org (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Koupatsiaris, A.A.; Drinia, H. Investigating Sense of Place and Geoethical Awareness among Educators at the 4th Summer School of Sitia UNESCO Global Geopark: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Geosciences 2024, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. The Significance of Geotourism through the Lens of Geoethics. In Geotourism in the Middle East; Stewart, I.S., Alsharhan, A.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Drinia, H.; Voudouris, P.; Antonarakou, A. Geoheritage and Geotourism Resources: Education, Recreation, Sustainability II. Geosciences 2023, 13, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. Geoethics: Ethical, Social and Cultural Implications in Geosciences. Ann. Geophys. 2017, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrowsky, P.; Cronin, V.S.; Di Capua, G.; Kieffer, S.W.; Peppoloni, S. The Emerging Field of Geoethics. In Scientific Integrity and Ethics in the Geosciences; Wyss, M., Peppoloni, S., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 175–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcavilla, L.; Cabrera, A.; Díaz-Martínez, E.; Luengo, J.; Vegas, J. Treinta Años de Geoconservación en España. Museol. Patrim. 2022, 15, 54–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, X.; Nawijn, J.; von Zumbusch, J. A New Materialist Governance Paradigm for Tourism Destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, D.A. Geotourism: A Geographical Review of the Literature. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Tverijonaite, E. Geotourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Geosciences 2018, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Canio, F.; Martinis, A.; Todaro, G.; Nocca, F. Geotourism as a Catalyst for Sustainable Development: The Role of Geoheritage and Local Communities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Han, Z.; Han, J.; Pang, X.; Song, W.; Wang, Q. From Geoparks to Regional Sustainable Development: Geoheritage Protection and Geotourism Promotion of Geoparks in Hebei Province, China. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, K.; Colomer, M. Geoparks and Education: UNESCO Global Geopark Villuercas–Ibores–Jara as a Case Study in Spain. Geosciences 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R. Geoheritage and Geotourism. In Geoheritage; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hose, T. A3G’s for Modern Geotourism. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulos, G.; Drinia, H.; Antonarakou, A.; Zouros, N. From geoheritage to geoeducation, geoethics and geotourism: A critical evaluation of the Greek region. Geosciences 2021, 11, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, A.; Almeida, Â. The importance of geology as a contribution to the awareness of the cultural heritage as an educational resource. In Geoscience Education: Indoor and Outdoor; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulos, G.; Drinia, H. Evaluating the Impact of Geoeducation Programs on Student Learning and Geoheritage Awareness in Greece. Geosciences 2024, 14, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koupatsiaris, A.A.; Drinia, H. Expanding Geoethics: Interrelations with Geoenvironmental Education and Sense of Place. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulos, G.; Drinia, H. Kalymnos Island, SE Aegean Sea: From Fishing Sponges and Rock Climbing to Geotourism Perspective. Heritage 2021, 4, 3126–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Ng, Y.; Zhang, E.; Tian, M. (Eds.) Dictionary of Geotourism; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałka, E. The Development of Geotourism and Geoeducation in the Holy Cross Mountains Region (Central Poland). Quaest. Geogr. 2023, 42, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivaditis, G.; Alexouli-Leivaditi, A. Geomorphology of the island of Tinos. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2001, 34, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Food & Wine. Here’s how you can drink wine grown on the battlegrounds of Greek gods. Food & Wine. 31 October 2024. Available online: https://www.foodandwine.com/tinos-greece-vineyards-8736082 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Pe-Piper, G.; Piper, D.J.; Matarangas, D. Regional implications of geochemistry and style of emplacement of Miocene I-type diorite and granite, Delos, Cyclades, Greece. Lithos 2002, 60, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makropoulos, K.; Kaviris, G.; Kouskouna, V. An Updated and Extended Earthquake Catalogue for Greece and Adjacent Areas since 1900. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOA Geodynamics Institute. Real-Time and Historical Seismicity Data. Available online: https://bbnet.gein.noa.gr (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Fokaefs, A.; Giraleas, N.; Karastathis, V.; Balis, D. A New Catalogue of Tsunamis in the Eastern Mediterranean, Aegean Sea and the Black Sea. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 309–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostou, V.; Kyriakidou, X.; Drakopoulou, P. The morphodynamics of the island of Tinos (Cyclades) as a mechanism for shaping its coasts. In Proceedings of the 9th Panhellenic Oceanography & Fisheries Symposium, Patras, Greece, 13–16 May 2009; Volume 1, pp. 190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Jolivet, L.; Lecomte, E.; Huet, B.; Denèle, Y.; Lacombe, O.; Labrousse, L.; Pourhiet, L.; Mehl, C. The North Cycladic Detachment System. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 289, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brichau, S.; Ring, U.; Carter, A.; Monié, P.; Bolhar, R.; Stockli, D.; Brunel, M. Extensional faulting on Tinos Island, Aegean sea, Greece: How many detachments? Tectonics 2007, 26, 1187–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taymaz, T.; Yilmaz, Y.; Dilek, Y. The geodynamics of the Aegean and Anatolia: Introduction. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spéc. Publ. 2007, 291, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, T.N.; Searle, M.P.; Gopon, P.; Roberts, N.M.; Wade, J.; Palin, R.M.; Waters, D.J. The Cycladic Blueschist Unit on Tinos, Greece: Cold NE Subduction and SW Directed Extrusion of the Cycladic Continental Margin under the Tsiknias Ophiolite. Tectonics 2020, 39, e2019TC005890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotet, F.; Jolivet, L.; Vidal, O. Tectono-Metamorphic Evolution of Syros and Sifnos Islands (Cyclades, Greece). Tectonophysics 2001, 338, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, T.; Vidal, O.; Jolivet, L. Relation between the Intensity of Deformation and Retrogression in Blueschist Metapelites of Tinos Island (Greece) Evidenced by Chlorite–Mica Local Equilibria. Lithos 2002, 63, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröcker, M.; Franz, L. Rb–Sr Isotope Studies on Tinos Island (Cyclades, Greece): Additional Time Constraints for Metamorphism, Extent of Infiltration-Controlled Overprinting and Deformational Activity. Geol. Mag. 1998, 135, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulia, E.; Kokinou, E.; Panagiotakis, C. The Contribution of Pattern Recognition Techniques in Geomorphology and Geology: The Case Study of Tinos Island (Cyclades, Aegean, Greece). Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 51, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasemann, B.; Schneider, D.A.; Stöckli, D.F.; Iglseder, C. Miocene Bivergent Crustal Extension in the Aegean: Evidence from the Western Cyclades (Greece). Lithosphere 2012, 4, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denèle, Y.; Lecomte, E.; Jolivet, L.; Lacombe, O.; Labrousse, L.; Huet, B.; Le Pourhiet, L. Granite Intrusion in a Metamorphic Core Complex: The Example of the Mykonos Laccolith (Cyclades, Greece). Tectonophysics 2011, 501, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melidonis, N.G. The Geological Structure and Mineral Deposits of Tinos Island (Cyclades–Greece). Geol. Greece 1980, 13, 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, T.N.; Roberts, N.M.; Searle, M.P.; Gopon, P.; Waters, D.J.; Millar, I. The Age, Origin, and Emplacement of the Tsiknias Ophiolite, Tinos, Greece. Tectonics 2020, 39, e2019TC005677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubisch, J. The Ethnography of the Islands: Tinos. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1976, 268, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2015. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/decisions/10.COM/10.B.17 (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Kourou, N. From the Dark Ages to the Rise of the Polis in the Cyclades: The Case of Tenos. In The “Dark Ages” Revisited. I.; Mazarakis Ainian, A., Ed.; University of Thessaly: Volos, Greece, 2011; pp. 399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrogonatos, C.; Magganas, A.; Kati, M.; Bröcker, M.; Voudouris, P. Ophicalcites from the Upper Tectonic Unit on Tinos, Cyclades, Greece: Mineralogical, Geochemical and Isotope Evidence for Their Origin and Evolution. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2021, 110, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anevlavi, V.; Doperé, F.; Sideridis, A.; Prochaska, W.; Angelopoulou, A. Marble Extraction and Its Industry: A Multidisciplinary Case Study of the Vathi Quarry on Tinos Island. Światowit 2024, 62, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideridis, A.; Anevlavi, V.; Tombros, S.F.; Hauzenberger, C.; Koutsovitis, P.; Boumpoulis, V.; Jakobitsch, T.; Petrounias, P.; Aggelopoulou, A. Developing a Provenance Framework for Ancient Stone Materials: A Subduction-Related Serpentinite Case Study from Tinos, Cyclades, Greece. Minerals 2025, 15, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelpidou, N.; Karkani, A.; Tzouxanioti, M.; Spyrou, E.; Petropoulos, A.; Lakidi, L. Inventory and Assessment of the Geomorphosites in Central Cyclades, Greece: The Case of Paros and Naxos Islands. Geosciences 2021, 11, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelpidou, N.; Vassilopoulos, A.; Gaki-Papanastassiou, K. Palaeogeographic Evolution of the Cyclades Islands (Greece) during the Holocene. In Coastal and Marine Geospatial Technologies; Green, D.R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Weingartner, H. Tafoniverwitterung in Naxos. In Geographische Studien Auf Naxos; Salzburger Exkursionsberichte: Salzburg, Austria, 1982; Volume 8, pp. 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Matsukura, Y.; Tanaka, Y. Effect of Rock Hardness and Moisture Content on Tafoni Weathering in the Granite of Mount Doeg-Sung, Korea. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 2000, 82, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmy, H. Klimamorphologie der Massengesteine, 2nd ed.; Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft: Hesse, Germany, 1981; p. 254. [Google Scholar]

- Altherr, R.; Kreuzer, H.; Wendt, I.; Lenz, H.; Wagner, G.; Keller, J.; Harre, W. A Late Oligocene/Early Miocene High-Temperature Belt in the Attic-Cycladic Crystalline Complex (SE Pelagonian, Greece). Geol. Jahrb. 1982, E23, 97–164. [Google Scholar]

- Pe-Piper, G.; Piper, D.J.W. The Igneous Rocks of Greece: The Anatomy of an Orogen; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Theodoropoulos, D. Cellular Disintegration Phenomena (Tafoni) on the Island of Tinos. Ann. Géol. Pays Hellén. 1974, 26, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Soukis, K.; Koufosotiri, E.; Stournaras, K.G. Special landforms in Tinos: Global disintegration and “tafoni” forms. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Scientific Symposium on Protected Areas and Monuments of Nature, Lesbos, Greece, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Klaer, W. Verwitterungsformen im Granit auf Korsika. Petermanns Geogr. Mitt. 1956, Ergänzungsheft 261, Gotha; Frenzel, G. Studien an Mediterranen Tafoni. Neues Jahrb. Geol. Paläontol. Abh. 1965, 122, 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, P. Tafoni Weathering, with Examples from Tuscany. Z. Geomorphol. 1978, 22, 44–67. Available online: http://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=12835536 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Mellor, A.; Short, J.; Kirkby, S.J. Tafoni in the El Chorro Area, Andalucia, Southern Spain. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 1997, 22, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, H. Beobachtungen zur Klimamorphologie von Massengesteinen in den Alt- und Neuweltlichen Subtropen vorwiegend des Mediterranen Typs. In Festschrift für Herbert Paschinger; Arbeiten aus dem Geographischen Institut der Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 1991; Volume 30, pp. 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hejl, E. A Pictorial Study of Tafoni Development from the 2nd Millennium BC. Geomorphology 2005, 64, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, T.; Stangl, D.; Weingartner, H. Tafoniverwitterung auf Thassos. Ein Fallbeispiel. In Salzburger Geographische Arbeiten; Beiträge zur Landeskunde von Griechenland III; Universität Salzburg: Salzburg, Austria, 1989; Volume 18, pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sabot, V. La Geomorphologie et la Geologie du Quaternaire de l’Ile de Naxos, Cyclades-Greece. Master’s Thesis, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium, 1978; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Evelpidou, H.N. Geomorphological and Environmental Study in Naxos Island (Cyclades) Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Physical Geography-Climatology, Department of Geology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingartner, H.; Wögerbauer, E. Microclimate and Tafoni Weathering: Results of a Field Study on the Island of Naxos (Cyclades, Greece). In Proceedings of the 6th Pan-Hellenic Geographical Conference of the Hellenic Geographical Society, Thessaloniki, Greece, 9–11 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leonidopoulou, D. Geological and Geomorphological Factors in the Formation of Intrinsic Vulnerability of Fractured Rocks: Application on the Island of Tinos. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Physical Geography-Climatology, Department of Geology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroukian, H.; Leonidopoulou, D.; Skarpelis, N.; Stournaras, G. Effects of Lithology, Mineralogy, and Weathering on Particle Size Variability of Sediments in the Coastal Environment of Livada Bay in SE Tinos Island, Greece. J. Coast. Res. 2010, 26, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penck, A. Morphologie der Erdoberfläche; Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft: Stuttgart, Germany, 1984; Volume 1, p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- Gaki-Papanastassiou, K.; Maroukian, H.; Papanikolaou, D. Geomorphological Evolution of Tinos Island (Cyclades, Greece): An Example of Island Landscape Development in the Aegean. Z. Geomorphol. N.F. 1992, 36, 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Twidale, C.R. Granite Landforms; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Migoń, P. Granite Landscapes of the World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dragovich, D.; Twidale, C.R. Granite Landforms. In Geomorphology of Desert Environments, 2nd ed.; Thomas, D.S.G., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 287–314. [Google Scholar]

- Varnes, D.J. Slope Movement Types and Processes. In Landslides: Analysis and Control; Schuster, R.L., Krizek, R.J., Eds.; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1978; pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Marinos, G.; Petrascheck, W.E. Geology of the Western Cyclades. Ann. Géol. Pays Hellén. 1956, 7, 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lallemant, S.; Patriat, M. 3D-Kinematics of Extension in the Aegean Region from the Early Miocene to the Present: Insights from the Ductile Crust. Bull. Soc. Géol. Fr. 1994, 165, 195–209. [Google Scholar]

- Spathari, E. Tinos: History and Monuments; Ekdotike Athenon: Athens, Greece, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bâca, I.; Schuster, E. Listing, evaluation and touristic utilisation of geosites containing archaeological artefacts. Case study: Ciceu ridge (Bistrita-Nasaud County Romania). Rev. Geogr. Acad. 2011, 5, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi, V.M.; Cendrero, A.; Albertos, J.A.C. A statistical approach to the validation and optimisation of geoheritage assessment procedures. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassoulas, C.; Mouriki, D.; Dimitriou-Nikolakis, P.; Iliopoulos, G. Quantitative assessment of geotopes as an effective tool for geoheritage management. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Pereira, D.; Caetano Alves, M.I. Geomorphosite assessment in Montesinho natural park (Portugal). Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, B.; Daigneault, R.A. La mise en valeur du patrimoine géologique du Sentier national du Québec dans les Laurentides. Le Nat. Can. 2011, 135, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E.; Fontana, G.; Kozlik, L.; Scapozza, C. A method for assessing “scientific” and “additional values” of geomorphosites. Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybář, R. Filozofie zdraví jako výchova ke zdravému životu. Škola A Zdr. Pro 2010, 21, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tucki, A. Propozycja regionalizacji turystycznej województwa lubelskiego. Folia Tur. 2009, 21, 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Warszyńska, J. Ocena Zasobów Środowiska Naturalnego Dla Potrzeb Turystyki: (Na Przykładzie Woj. Krakowskiego); Nakł. Uniw. Jagiellońskiego: Kraków, Poland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wimbledon, W.A.P.; Ishchenko, A.A.; Gerasimenko, N.P.; Karis, L.O.; Suominen, V.; Johansson, C.E.; Freden, C. Geosites—An IUGS Initiative: Science Supported by Conservation. In Geological Heritage: Its Conservation and Management; Barettino, D., Wimbledon, W.A.P., Gallego, E., Eds.; Instituto Tecnológico GeoMinero de España (ITGE): Madrid, Spain, 2000; pp. 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi, V.M.; Cendrero, A. Direct and parametric methods for the assessment of geosites and geomorphosites. Geomorphosites 2009, 9, 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bollati, I.; Smiraglia, C.; Pelfini, M. Assessment and selection of geomorphosites and trails in the Miage Glacier Area (Western Italian Alps). Environ. Manag. 2013, 51, 951–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cendrero, A. El patrimonio geológico. Ideas para su protección, conservación y utilización. In El Patrimonio Geológico. Bases para su Valoración, Protección, Conservación y Utilización; MOPTMA, Ed.; Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Transportes y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 1996; pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cendrero, A. Propuestas sobre criterios para la clasificación y catalogación del patrimonio geológico. In El Patrimonio Geológico. Bases Para su Valoración, Protección, Conservación y Utilización; MOPTMA, Ed.; Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Transportes y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 1996; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Coratza, P.; Giusti, C. Methodological proposal for the assessment of the scientific quality of geomorphosites. Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 2005, 18, 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, P.; Pereira, D. Methodological guidelines for geomorphosite assessment. Géomorphol. Relief Process. Environ. 2010, 16, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pralong, J.P.; Reynard, E. A proposal for a classification of geomorphological sites depending on their tourist value. Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 2005, 18, 315–321. [Google Scholar]

- Zafeiropoulos, G.; Drinia, H. GEOAM: A holistic assessment tool for unveiling the geoeducational potential of geosites. Geosciences 2023, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulos, G. The Importance of Geoenvironmental Education in Understanding Geological Heritage and Promoting Geoethical Awareness: Development and Implementation of an Innovative Assessment Method, with a Case Study of the Southeast Aegean Islands. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Geology and Geoenvironment, School of Science, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouros, N.C. Geomorphosite assessment and management in protected areas of Greece: Case study of the Lesvos Island–coastal geomorphosites. Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]