Abstract

In high-density and land-scarce urban environments such as Taipei—a typical example of compact development in East Asia—informal green spaces (IGSs)—defined as unmanaged or unplanned vegetated urban areas such as vacant lots, street verges, and railway margins—play a growing role in urban environmental and social dynamics. This study explores residents’ perceptions of IGSs and examines how these spaces contribute to urban sustainability and land governance. Using a mixed-methods approach that combines the literature review, field observations, and a structured public opinion survey in Taipei’s Wenshan District, the study identifies key perceived benefits and drawbacks of IGSs. Findings show that residents highly value IGSs for enhancing urban greenery, offering recreational opportunities, and promoting physical and mental health. However, concerns persist regarding safety, sanitation, and maintenance—particularly fears of waste accumulation, mosquito breeding, and risks to children. The results highlight the dual nature of IGSs as both vital ecological assets and potential sources of urban disorder. These insights underscore the need for inclusive, community-based governance models that can transform IGSs into legitimate components of green infrastructure. The study contributes to emerging discussions on adaptive urban land governance by proposing that informal spaces be strategically integrated into urban planning frameworks to enhance environmental equity, resilience, and citizen well-being.

1. Introduction

In rapidly urbanizing and land-scarce cities, such as those in East Asia, urban land resources are increasingly under pressure from high-density development, real estate speculation, and the prioritization of economic over ecological functions [1,2]. As a result, the provision of formal green infrastructure often falls short of national or international standards, especially in compact cities like Taipei [1]. This situation has intensified the search for alternative land resources that can support ecological, social, and recreational functions. One such underexplored resource is informal green space (IGS)—including vacant lots, brownfields, roadside verges, utility corridors, and unmanaged or spontaneous vegetated areas [3,4,5,6,7].

IGSs refer to vegetated areas within urban environments that are not formally designated, planned, or maintained as public green spaces. These include vacant lots, roadside verges, railway embankments, riverbanks, and other unmanaged or spontaneous green patches that arise due to regulatory, spatial, or developmental gaps. Although often overlooked in formal planning processes, IGSs provide a range of ecological, recreational, and cultural functions. As Rupprecht and Byrne [3] note, IGSs are frequently considered “leftover” or marginal urban spaces, yet they play a significant role in residents’ everyday interactions with nature.

Building on the study by Kim et al. [1] in Ichikawa City, which examined residents’ perceptions of IGSs in a suburban Japanese context, this study investigates similar perceptions in a dense inner-city district in Taipei. While both cities are situated in East Asia, their contrasting spatial characteristics, land use intensity, and socio-political contexts offer a valuable comparative perspective. This study thus seeks to extend the understanding of IGSs’ perception into a high-density, inner-urban environment.

IGSs are not formally designated or maintained as public green spaces but are often used by residents for walking, jogging, gardening, and informal social gatherings [1,8,9]. These spaces frequently emerge from urban voids or are shaped through grassroots or community efforts. Although typically overlooked in urban planning, IGSs provide a wide range of ecosystem services, including temperature regulation [7,10,11,12,13], biodiversity enhancement [14], and recreational opportunities [8,15]. Importantly, IGSs can serve to reduce inequalities in access to green spaces for marginalized groups such as children and the elderly [16], while also supporting socio-cultural values [17].

However, the benefits of IGSs coexist with concerns related to safety, cleanliness, social conflict, and governance ambiguity [6,18]. Poorly maintained or perceived unsafe spaces may negatively affect residents’ well-being, particularly in disadvantaged neighborhoods [5,19]. Furthermore, IGSs can become inaccessible due to privatization or lack of community engagement, as noted in recent critiques of housing developments that incorporate but restrict access to green areas [16].

There is increasing evidence that IGSs contribute to both mental and physical health outcomes, including reduced stress, improved cardiovascular health, and increased physical activity [1,20,21,22,23,24]. The more naturalistic qualities of IGSs often foster stronger restorative experiences than manicured parks [25,26]. At the same time, urban green spaces and IGSs can function synergistically, offering a complementary system of structured and spontaneous recreational environments [15,25,27].

Despite their potential, residents’ perceptions and evaluations of IGSs remain understudied, particularly in Asian cities where land scarcity and high development intensity create unique conditions for informal green space to emerge and function [1,2,26]. Perceptions of IGSs are influenced by various factors, including safety, accessibility, esthetics, maintenance, and personal or cultural preferences [23,28]. While some residents may prefer wild and spontaneous spaces, others may favor more designed or controlled environments [5,20].

Citizen participation plays a critical role in shaping perceptions and the success of IGSs. Community engagement in gardening or co-maintenance initiatives can foster stewardship and increase perceived value [1,17,22]. Different IGS maintenance regimes—ranging from non-intervention to periodic intervention—can also influence their ecological contribution and social acceptance [7,8,23].

In light of these considerations, IGSs should be reframed not as leftover or failed urban space but rather as latent land resources capable of enhancing socio-ecological resilience and supporting adaptive land governance [2,6]. This is especially pertinent for cities experiencing demographic shifts or undergoing urban shrinkage, where IGSs can support land use transitions and sustainable reuse strategies [14].

For example, Taipei City provides approximately 5.36 m2 of public green space per person, significantly lower than the World Health Organization’s recommended minimum of 9 m2 and far below UN-Habitat’s ideal standard of 15 m2 per capita. According to the Taipei City Government’s statistics, less than 3% of the total urban land area is allocated to parkland, reflecting the city’s limited capacity to develop additional formal green infrastructure. This spatial limitation underscores the importance of exploring alternative green provisions—such as IGSs—to meet residents’ recreational and ecological needs under conditions of spatial constraint. This study situates IGSs within the broader challenges of green space governance in high-density cities. Such contexts—characterized by limited per capita open space, high land values, and rapid infill development—create distinctive pressures on both formal and informal green infrastructures. As such, understanding how residents engage with IGSs in a city like Taipei can yield policy-relevant insights for other compact urban environments. The purpose of this study is to explore the current state of IGSs in Taipei City and examine how residents perceive, use, and evaluate these spaces. Through a mixed-methods approach—combining the literature review, questionnaire surveys, field observations, and in-depth interviews—we aim to address the following research questions:

- ‑

- How do urban residents perceive and use IGSs in high-density cities?

- ‑

- What functions and values do they associate with these spaces?

- ‑

- How might these perceptions inform future land governance strategies and green space planning?

By foregrounding public attitudes toward IGSs, this study contributes to the growing discourse on adaptive land management, participatory planning, and the integration of informal spaces into sustainable urban land use systems. To further theorize the dual character of IGSs as both opportunity and challenge, this study draws on Simandan’s concept of “the wise stance”, which interprets wisdom as a form of balancing competing urban values—between ecological spontaneity and safety concerns, or between informal uses and formal planning [29]. This conceptual lens helps frame IGSs not simply as neglected spaces, but as sites of negotiated cohabitation.

Moreover, urban wildscapes—often found in the form of post-industrial or marginal spaces—have been critically examined by scholars such as Whatmore in her theory of Hybrid Geographies, which challenges binary distinctions between nature and culture [30]. Gandy’s recent work Natura Urbana [31] further situates these spaces within urban political ecology, emphasizing their latent capacity to reflect social imaginaries and contested ecological futures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area

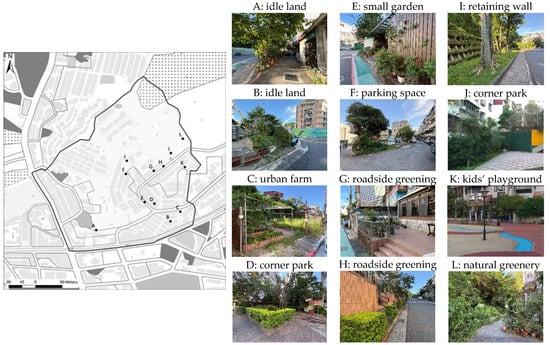

The study was conducted in Wenshan District of Taipei City, a dense urban area known for its proximity to hills and waterways, yet also constrained by limited availability of formal green spaces. While Taipei promotes mixed-use development and has invested in formal parks such as Daan Forest Park and Riverside Park, many residents engage with IGSs—including vacant lots, roadside verges, and rooftop gardens—for recreational and ecological purposes. These spaces often exist outside formal planning systems, making them ideal for examining resident perceptions under conditions of limited green infrastructure provision. The selection of Wenshan District was based on its diverse land use types, socio-demographic mix, and visible presence of IGSs. To enhance the spatial understanding of the fieldwork area, a map of the identified IGSs is provided in Figure 1 and Figure 2. This visual contextualization helps illustrate the distribution and variety of green parcels included in the study.

Figure 1.

Experimental site map of Wenshan District, Taipei City.

Figure 2.

Informal Green Spaces (IGSs) selected for field observation and survey in Wenshan District, Taipei. The map shows the spatial distribution of vacant lots, roadside green strips, and underutilized parcels identified through field visits and community input.

2.1.1. Mixed-Use Development and Transportation

Taipei City has embraced mixed-use development, which combines residential, commercial, and office spaces within the same building or neighborhood. This encourages sustainable living and reduces the need for long commutes. Additionally, mixed-use development promotes walkability, as residents have easy access to amenities and services within their neighborhood. Taipei City has developed an extensive public transportation system, which includes buses, subways, and a high-speed rail system. This transportation network provides residents and visitors with efficient and affordable modes of transportation, reducing traffic congestion and air pollution. In addition, the city has implemented a bike-sharing program that encourages the use of sustainable and healthy modes of transportation.

2.1.2. Green Spaces

Taipei City is known for its numerous green spaces, which provide residents and visitors with opportunities for recreation, relaxation, and connection with nature. The most popular green spaces in Taipei such as the following: Daan Forest Park, Taipei Riverside Park, and Taipei Botanical Garden. Overall, Taipei City’s green spaces are an important part of the city’s culture and identity, providing residents and visitors with opportunities to connect with nature and enjoy the outdoors. IGSs in Taipei City refer to areas that are not designated as official parks or public green spaces but still serve as important recreational and social spaces for residents. These areas can take many forms, such as community gardens, vacant lots, and roadside plantings.

2.1.3. IGSs

One notable example of IGSs in Taipei City is the rooftop gardens that have become increasingly popular in recent years. Residents often establish rooftop gardens using containers and improvised materials to cultivate fruits, vegetables, and ornamental plants. Not only do these gardens provide residents with access to fresh produce, but they also help to mitigate the urban heat-island effect and improve air quality.

Another type of IGSs in Taipei City are the so-called “pocket parks”. These are small, often hidden green spaces that can be found throughout the city, such as in alleyways or on the edges of neighborhoods. These parks often feature benches, plants, and other amenities and serve as important gathering places for local residents. One challenge with IGSs in Taipei City is that they may not receive the same level of maintenance and care as official parks, which can lead to issues with litter and overgrowth. However, these spaces also offer a sense of community ownership and engagement, as residents take on the responsibility of maintaining and caring for them. Overall, IGSs in Taipei City play an important role in providing residents with access to greenery and nature, as well as fostering a sense of community and connection to the urban environment.

Taipei City’s urban planning efforts are focused on creating a livable, sustainable, and resilient city for its residents and visitors. Through the implementation of an extensive public transportation system, the creation of formal and IGSs, and the adoption of mixed-use development, Taipei City is addressing the challenges of population growth and the need for sustainable development. These efforts demonstrate Taipei City’s commitment to creating a more livable and sustainable urban environment.

2.2. Classification of IGSs

Compared to formal green spaces—such as urban parks, botanical gardens, and designated green corridors—which are officially planned, funded, and maintained by public authorities, IGSs lack formal designation and institutional management. While formal green spaces are often associated with structured recreational amenities, landscape esthetics, and strict zoning, IGSs are typically characterized by spontaneity, adaptive reuse, and marginal status in planning systems [3,16].

Despite these differences, both types contribute to urban ecosystem services, albeit in different ways. Formal green spaces are designed for predictability, safety, and social integration, while IGSs provide critical ecological functions in overlooked or residual spaces, such as supporting biodiversity, enhancing microclimates, and serving marginalized communities [5]. Therefore, a critical distinction lies in their governance and inclusivity; IGSs often embody grassroots engagement and adaptive potential, whereas formal green spaces reflect top-down planning approaches.

The literature analysis method is a valuable research methodology that provides researchers with a comprehensive understanding of a particular field of study. By organizing, evaluating, and analyzing the relevant literature, researchers can identify key findings, theories, and methods related to a particular topic and use this information to propose further research questions and hypotheses. Overall, the literature analysis is a useful tool for researchers in a variety of fields. Through the method of the literature analysis, this study refers to the clear definition of IGSs in the relevant literature [1,3,4,6,8,32]. “Informal green space” refers to green areas in urban or peri-urban environments that are not formally recognized or planned as public parks or green spaces. These spaces can take a variety of forms, such as vacant lots, community gardens, roadside plantings, or green roofs. After referring to the relevant literature [3,4,5,7,8,16,20,21,22,24,26,27,28,32,33], this study concludes that there are the following types of IGSs, such as: street verge, lot, gap, railway, brownfield, waterside, structural, microsite, power line, fortification, and fallow or uncultivated land, etc.

Informal green space exists around residents’ homes and is relatively accessible; the original urban ecosystem is completely preserved. Compared with managed green spaces such as parks, there are abundant natural resources; it offers a degree of spontaneity and adventure often lacking in formal parks, especially appealing to the youth. However, human beings often regard the environment that lacks management and maintenance as an unsafe space subjectively; the unbeautified natural landscape and vegetation space will increase the possibility of crime and reduce the willingness of users to go there. Therefore, IGSs have multiple functions [6,11,25].

Several studies have demonstrated that IGSs can serve as sites of social interaction, provide visual relief, and enhance perceived neighborhood quality. Kim et al. [1] categorized IGSs’ types based on physical characteristics and evaluated user perceptions through a structured survey. They found that residents valued IGSs for accessibility and visual relief but expressed concerns over safety and maintenance. Their study emphasized the importance of spatial context and prior experience in shaping perception—a premise that also informs the present study. Similarly, in the context of Taipei, our study aims to explore how spatial conditions, accessibility, and past neighborhood engagement influence the perception and acceptance of IGSs.

The utilization and planning of green spaces is a common focus in urban research. Taipei City’s current regulations on legal green spaces in urban planning encompass parks, sports venues, green spaces, squares, and children’s playgrounds. Formal green spaces are often well-integrated into planning frameworks but face significant governance and implementation challenges—especially in ensuring accessibility, multifunctionality, and stakeholder engagement. One study, in a case study of Berlin, highlights that even in well-established formal green spaces, the integration of ecosystem services into planning faces fragmented governance, conflicting stakeholder interests, and data limitations [9]. These issues suggest that IGSs, while informally managed, may offer adaptive advantages in addressing urban sustainability gaps under constrained institutional conditions.

In the realm of academic research, the identification of green spaces is largely dependent on the researcher’s objectives. Typically, green space is defined as managed areas such as parks, schools, or gardens. Informal spaces like rivers, railways, utility poles, or gaps between buildings are deemed unsafe due to a lack of regular maintenance, which results in residents being less inclined to utilize these areas. Furthermore, in the absence of green space within the living environment, some residents may spontaneously create green space that does not conform to the planning system. In today’s cities, residents may have unconsciously utilized or established IGSs to compensate for the lack of formal green spaces. Despite their scattered distribution throughout urban areas, these “IGSs” possess an inherent value that cannot be understated.

2.3. Positive and Negative Impacts of “Informal Green Space”

2.3.1. Positive Impacts of “Informal Green Space”

IGSs, also known as urban green spaces or green infrastructure, refer to areas within cities that are not designated as formal parks or gardens but still provide natural elements and ecological benefits. These spaces can include community gardens, vacant lots, street trees, pocket parks, and other small-scale green areas. While formal parks and protected areas are important, IGSs also play a significant role in enhancing the urban environment and have several positive impacts. Let us explore some of the following positive impacts, such as: biodiversity and habitat preservation, climate regulation, improved mental health and well-being, community engagement and social cohesion, and stormwater management.

Firstly, IGSs can act as valuable habitats for various plant and animal species, contributing to urban biodiversity. Some studies’ results show that IGSs play an important role for biodiversity [8]. One study also found comparable ecosystem services provisioning for dust removal, cooling benefits, water storage, and biodiversity preservation in IGSs and urban parks [27]. They provide food, shelter, and nesting sites for birds, insects, and other wildlife, thereby supporting local ecosystems. These spaces often contain a diverse range of plant species, including native plants, which further enhances their ecological value.

For study ecosystem services of IGSs, after reviewing the 112 papers, one paper found three types of services that were discussed the most: habitat services, cultural services, and climate regulation services [5]. In fact, urban green spaces, both formal and informal, contribute to climate regulation by mitigating the urban heat island effect. Vegetation in IGSs absorbs and filters pollutants from the air while providing shade and reducing the surface temperature in built-up areas. This helps to cool the surrounding environment, improve air quality, and reduce energy consumption for air conditioning.

In recognition that the coming century will see a substantial majority of the world’s population living in urban areas, the World Health Organization and the United Nations have developed policy frameworks and guidance, which promote the increased provision of urban green space for population health [20]. IGSs offer opportunities for relaxation, recreation, and social interaction. Access to green spaces has been linked to improved mental health outcomes, including reduced stress, anxiety, and depression. Spending time in these areas can promote physical activity, encourage social connections, and provide a sense of tranquility, which positively impacts overall well-being.

One study found that urban parks are more inclusive green places than non-urban green areas and that urban parks can promote social cohesion [34]. Moreover, IGSs often serve as gathering places for local communities, fostering a sense of belonging and social cohesion. Community gardens, for instance, bring people together around a shared interest in gardening, food production, and environmental stewardship. These spaces provide opportunities for education, skill-building, and the exchange of knowledge among community members. Nevertheless, due to various constraints and barriers, such as lack of accessibility, limited local knowledge or acceptance, and the cultural services of IGSs, especially those related to recreation, are not fully exploited. The similar conclusion was reached by a study where people did not use these spaces for recreation and did not attribute them with educational and inspirational values [26].

A network of green spaces (for example, parks) and blue spaces (for example, wetlands), productive natural landscapes such as allotment/domestic gardens, or a small-scale ecological solution for stormwater management can all be considered as components of green infrastructure [35]. IGSs play a crucial role in managing stormwater runoff in urban areas [5]. They can absorb and retain rainfall, reducing the strain on drainage systems and helping to prevent flooding and water pollution. By allowing rainwater to infiltrate into the ground, these spaces contribute to groundwater recharge and help maintain water quality. IGSs, with their multiple benefits, contribute to creating healthier, more sustainable, and livable cities. They offer a range of positive impacts, including ecological, social, and psychological benefits, while contributing to the overall well-being of urban communities. Therefore, informal green space has many functions, so it is very worthy of the government’s accumulation and investment in academic research.

2.3.2. Negative Impacts of “Informal Green Space”

While IGSs have numerous positive impacts, it is important to acknowledge that they can also have certain negative effects. The following are some of the potential negative impacts associated with IGSs: maintenance and management challenges, unequal distribution, safety concerns, environmental impacts, conflicts and disputes, and inadequate infrastructure and amenities.

IGSs often lack formal management structures and funding, which can lead to issues related to maintenance and upkeep [18]. Without proper management, these spaces may become overgrown, unkempt, or susceptible to invasive species. Neglected IGSs can create safety concerns, harbor pests, and become eyesores within the community. A study’s results suggest that different maintenance regimes for IGSs may improve their contribution to urban conservation; therefore, it proposes adapting management to the local context [8].

IGSs may sometimes be associated with safety issues, especially if they are poorly lit, isolated, or lack surveillance. A study revealed that, while IGSs offered different ecosystem services, not all IGSs were accessible to children due to safety concerns, maintenance conditions, and parental restrictions [18]. These areas can become gathering places for illicit activities or vandalism, raising concerns about personal safety and community security. The perception of a lack of safety can deter people from using or enjoying these spaces. The results showed most respondents (>70%) remembered using informal urban green spaces in the past and preferred them over other green spaces because they were easily accessible; meanwhile, most (>70%) recalled experiencing no problems (e.g., danger of injury) when using IGSs, a contrast to recently increasing parental concern for children’s safety [23]. Therefore, such factors may limit present informal urban green space use and prevent it from fulfilling the important role it played for previous generations’ recreation [23].

IGSs, especially community gardens and allotments, may occasionally become sites of conflict or disputes among different stakeholders. Disagreements may arise over issues such as land tenure, resource allocation, or conflicting visions for the use of space. For example, in developing China, residents in many emerging urban communities of China have been appropriating and reclaiming public open spaces intentionally as a leisure opportunity and transforming their entertainment functions into vegetable plots, which has caused a series of conflicts and disputes [36]. Resolving these conflicts can be challenging and may require effective community engagement and mediation. Nevertheless, resolving the conflict between habitat service and cultural service through considering the temporary benefits of ecological succession and enhancing the public’s accessibility and awareness of IGSs [37].

The parks and green squares are most frequently equipped with paths for night walks, playgrounds for children, outdoor gyms, flowerbeds, toilets, chess tables, bicycle paths, sculptures and monuments, and sports fields; in additionally, when it comes to recreational sites, playgrounds for children represent the most popular amenities, and followed by paths for night walks [38]. IGSs may lack essential infrastructure and amenities that are commonly found in formal parks. This can include a lack of seating, garbage bins, lighting, or public restrooms. Insufficient infrastructure and amenities can limit the usability and accessibility of these spaces, particularly for individuals with disabilities or the elderly. Therefore, it is essential to address these negative impacts through effective management, community engagement, and equitable distribution of resources to ensure that IGSs continue to provide benefits while minimizing any adverse effects.

2.4. Public Opinion Survey

A public opinion survey, also known as an opinion poll or survey, is a research method used to measure and gather information about the attitudes, beliefs, and preferences of a particular population or group of individuals. These surveys aim to provide insights into public opinion on various topics, including politics, social issues, consumer behavior, and more. The questionnaire was developed based on a synthesis of the international literature on IGSs, particularly focusing on ecosystem services, public safety, and urban planning concerns as identified by Rupprecht et al. [8], Luo & Patuano [5], and Sikorska et al. [16].

Public opinion surveys can be conducted through various means, including telephone interviews, face-to-face interviews, online questionnaires, and mail-in surveys. Careful sample selection is essential to ensure the accuracy and representativeness of survey results. Public opinion surveys play a significant role in shaping public discourse and decision-making processes. They provide valuable insights into the opinions and preferences of the general population, allowing policy-makers, businesses, and organizations to gauge public sentiment and adjust their strategies accordingly. Overall, public opinion surveys serve as a valuable tool for understanding the thoughts and attitudes of the general public. They provide a quantitative measure of public opinion, which can be used to inform decision-making processes in politics, marketing, policy development, and more. However, it is crucial to interpret survey results critically and consider the limitations and potential biases inherent in the survey methodology.

Therefore, this study endeavors to elucidate the public’s emphasis on the positive and negative perceptions of “informal green space” in Wenshan District, Taipei City. Firstly, the study conducted an analysis of the literature to identify eight positive impact items and six negative impact items of “informal green space”. Subsequently, the degree of the public opinion survey of the positive and negative impacts of “informal green space” was obtained via a questionnaire. Finally, the research findings will be presented to the government as a reference for improving and managing informal green space.

The questionnaire was distributed through a random intercept approach, conducted in various public settings adjacent to identified IGSs (e.g., street verges, idle lots, and small parks). While the sampling was not stratified by demographic characteristics, we aimed for heterogeneity by varying the time of day and survey locations to reach respondents of diverse age, gender, and employment background. However, the survey did not deliberately target specific vulnerable subgroups, such as the elderly or persons with disabilities, and we acknowledge this as a methodological limitation. Given the importance of inclusive green space planning, we recommend that future research adopt stratified or purposive sampling techniques to ensure adequate representation of these groups and explore how their IGS perceptions may differ from the general population.

A pilot test involving 10 residents from the Wenshan District was conducted to refine item clarity, wording, and response interpretation. Based on pilot feedback, minor adjustments were made to the phrasing of several items to enhance readability and eliminate ambiguity. The final questionnaire consisted of 14 items: eight addressing perceived positive impacts and six focusing on perceived negative impacts of IGSs. Internal consistency reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, which yielded values of 0.82 for the positive impact scale and 0.79 for the negative impact scale, indicating acceptable to good reliability. This validation process supports the robustness of the survey as a tool for gauging residents’ perceptions.

The survey was designed to minimize potential privacy concerns among respondents by avoiding the collection of personally sensitive information, including detailed socioeconomic status (SES) variables such as income, occupation, or household registration. Instead, the questionnaire focused on general perceptions, emotional responses, and usage behavior related to informal green spaces (IGSs), which are less likely to be influenced by SES in small-area studies. Furthermore, given the spatially constrained study area and the aim of capturing hyperlocal perceptions, a purposive sample of 52 valid responses was obtained from individuals with direct experience of IGSs in the neighborhood. Although the sample size is modest, it was sufficient to capture diverse narratives and usage patterns during the study period. Additional sampling was not pursued, as time-sensitive environmental and social conditions had changed since the initial fieldwork, making new data potentially non-comparable.

While the study collected 52 valid responses from residents in the Wenshan District, it is important to note that the relatively small sample size limits the statistical generalizability of the findings to the broader population of Taipei. Nevertheless, the results provide valuable exploratory insights into public perceptions of IGSs, especially in a high-density urban context where such spaces remain underexamined. Future studies with larger and more representative samples are encouraged to validate and expand upon these preliminary observations. To protect respondent anonymity and adhere to ethical standards in public intercept surveys, the questionnaire did not collect sensitive personal data such as age, household location, or precise residential distance from the surveyed IGSs. While this approach encouraged open participation and reduced privacy concerns, it also limited the ability to perform correlation or subgroup analyses between sociodemographic traits and IGSs’ perception patterns.

3. Results

Through the analysis of previous domestic and foreign literature and relevant policy content, this study sorts out the following positive and negative impacts that IGSs may have on the environment, which are the following eight positive impacts: increasing or maintaining rich greening, increasing biological species richness, providing animal and plant habitats, purifying air quality, promoting residents’ physical and mental health, providing recreational use, planting edible plants and activating urban space utilization; and six negative impacts: destroying environmental quality, affecting city appearance, producing garbage, and dumping waste space, breeding grounds for mosquito vectors, increased crime rates, and concerns about the safety of children.

The design of the self-administered questionnaire in this study adopts the Likert scale type, and the respondents answer the questions according to their subjective consciousness. The impact of the informal green space on the overall environment is divided into five points. The higher the score the higher the degree of influence; five means the highest degree of influence, and one means the least degree of influence. Aiming at the results of the questionnaires filled with personal experiences of the people, this study uses the mean, median, mode, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation to examine the degree of impact of different impact items on IGSs in the people’s subjective consciousness (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

The degree of positive impact of IGSs by ranking order.

Table 2.

The degree of negative impact of IGSs by ranking order.

The method of distributing questionnaires in this research is mainly based on the actual on-site distribution, and random distribution of questionnaires was adopted in the selection of distribution objects, and a total of 52 questionnaires were recovered (including 32 paper questionnaires and 20 online questionnaires). Although mean values were primarily used to rank the perceived importance of various IGS factors, skewness and kurtosis coefficients were analyzed to ensure the statistical appropriateness of this approach. A skewness value close to zero indicates a symmetrical distribution of responses, suggesting that the mean is a stable and unbiased measure of central tendency. Similarly, kurtosis values near zero suggest a mesokurtic distribution, implying that the responses do not exhibit extreme outliers or heavy tails. These indicators jointly validate the reliability of using mean scores for ranking, as they confirm that participant responses were normally distributed and not overly skewed or peaked.

3.1. The Degree of Positive Impact of IGSs

According to the analysis of respondents’ positive impact on informal green space, from the perspective of kurtosis coefficient and skewness coefficient, the kurtosis coefficient of the questionnaire survey results is between −1.298 and 1.372, and the skewness coefficient is between −1.098 Between and 0.091, it can be seen that the questionnaire result data presents a normal distribution. Regarding the distribution of the ratings given by the respondents, this study mainly uses the mean test to compare the arithmetic mean of the ratings of each item. According to the results of the questionnaire, most residents believe that IGSs can bring the following: 1. increase or maintain rich greenery, 2. provide recreational use, and 3. promote residents’ physical and mental health and other positive effects. It can be seen that for the residents, they generally agree that informal green space can bring a positive impact of rich greening to the environment. Secondly, for the two effects of providing recreational use and promoting residents’ physical and mental health, it means that residents agree with the entertainment provided by informal green space and can bring positive benefits to their physical and mental health. Among the assessed functions, planting edible crops received the lowest ratings, suggesting it holds less relevance for most residents. Obviously, for residents, whether the informal green space can be planted with edible plants is of little importance or influence.

3.2. The Degree of Negative Impact of IGSs

This study analyzes the degree of negative impact of respondents on informal green space and first judges whether the collected data is normally distributed. From the results, the kurtosis coefficient is between −0.562 and 0.673, and the skewness coefficient is between −0.562 and 0.673. Between −1.040 and 0.491, it means that the questionnaire results present a normal distribution. Secondly, this study uses the average test of the questionnaire results to compare the arithmetic mean of the scores of each item. According to the results of the questionnaire, the residents think that the informal green space has three negative impacts on the environment: 1. it becomes a space for dumping garbage, 2. it is a breeding ground for mosquitoes and vectors, 3. it has doubts about the safety of children, etc. These three negative impacts were rated as highly important by respondents. On the other hand, the two effects of affecting city appearance and destroying environmental quality are less important. In other words, the safety and sanitation management of informal green space is more important to residents.

3.3. Comprehensive Analysis

In order to strengthen people’s willingness to use informal green space, according to the results of this study, the advantages of “informal green space” that the government must strengthen are as follows: increase or maintaining rich greenery, for recreational use, and promoting the physical and mental health of residents. First of all, the government can promote the informal green space to increase the amount of greening through policies to meet the expectations of the public. Through government subsidies, the community can plant, manage, and maintain plants. In addition, the leisure and entertainment functions of IGSs accessible to the community can be discussed through public participation, and the leisure functions of IGSs can be strengthened with government funding or corporate sponsorship. Finally, as the functions of IGSs are improved, the physical and mental health of the people living around them can be improved.

On the other hand, according to the results of this study, people think that the most important negative impacts of “IGSs” are as follows: creating waste storage space, breeding grounds for mosquito vectors, and safety concerns for children. Therefore, through public participation management mechanisms (such as community adoption), the problems of clutter and mosquito breeding in IGSs can be reduced. Moreover, through security equipment and a public watch and help mechanism, the safety of children using IGSs can be ensured. Only by trying to improve the positive benefits of IGSs and reduce the negative dangers and risks can people be willing to use IGSs, and IGSs can complement urban parks and green spaces.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight both the recognized benefits and prevailing concerns regarding IGSs in dense urban environments such as Taipei. The residents’ evaluation reveals the following duality: while IGSs are broadly appreciated for their environmental and recreational functions, their unmanaged nature and ambiguous governance give rise to safety and sanitation concerns. This dual perception aligns with patterns reported in prior studies conducted in Japan [1,2], Europe [16,26], and Africa [18].

4.1. Public Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Everyday Functions

Among the eight positive impacts assessed, the highest-rated aspects—enhancing urban greening, enabling recreational use, and supporting physical and mental health—align closely with cultural and regulating ecosystem services identified in the literature [5,8,27]. These findings support the view that residents regard IGSs as not merely supplementary, but as integral, lived components of the urban environment that contribute to everyday urban life. Such perceptions provide valuable support for integrating IGSs into broader green infrastructure strategies [14,35].

However, lower scores for impacts such as “planting edible plants” suggest a more limited resident awareness or engagement with the productive functions of IGSs, such as urban agriculture. This may reflect both cultural attitudes and the limited institutional support for community gardening initiatives in Taipei, as observed similarly in China [36]. Strengthening policy and educational efforts to promote multifunctional use of IGSs may enhance both their perception and ecological utility.

Although the sample size in this study is modest, the findings serve an important exploratory function by illuminating patterns in residents’ valuations and concerns regarding IGSs. These insights can inform hypothesis generation and guide the design of broader, citywide or cross-city comparative studies. Moreover, the survey results complement the qualitative and literature-based components of the research, enhancing its overall relevance for adaptive urban land governance discussions. The use of mean values for ranking is supported by the skewness and kurtosis statistics reported in Section 3. Most items fell within acceptable thresholds (|skewness| < 0.5, |kurtosis| < 1), indicating consistent and normally distributed responses across participants. This statistical robustness strengthens the validity of the comparative ranking of perception factors.

4.2. Safety and Management as Constraints to Full Utilization

Residents’ concerns about IGSs—particularly waste dumping, mosquito breeding, and child safety—mirror the most common barriers to informal space usage reported internationally [6,18]. While more than 70% of respondents reported having used IGSs previously, their willingness to continue such usage appears conditional on perceived management quality and safety conditions, consistent with observations in Rupprecht et al. [23].

However, to fully appreciate these concerns, it is crucial to consider the inherent unpredictability and affective dimensions of IGSs. As Simandan [39] argues, experiences of fear or anxiety in urban environments often stem from the potential for “negative surprise”—such as unexpectedly encountering wildlife (e.g., snakes, raccoons, or coyotes) or illicit activity. These moments of unexpected confrontation evoke deeper feelings of spatial discomfort or even territorial alienation. Thus, residents’ fears are not just about sanitation or maintenance per se, but also about the psychological unease produced by spatial ambiguity and uncontrolled nature within the city. This interpretation helps explain why the negative perception of IGSs does not simply correlate with objective disorder, but rather emerges from a complex interplay of surprise, bodily response, and socio-cultural expectations of what urban nature should feel like.

Notably, concerns related to esthetics or urban design—such as visual disorder—received lower levels of negative response. This suggests that for Taipei residents, IGSs are not rejected on grounds of visual informality per se, but rather due to perceived disorder or neglect. This distinction is important for land governance approaches: interventions should prioritize sanitation and community safety mechanisms over visual beautification alone.

4.3. Implications for Urban Land Governance

The results confirm that IGSs in Taipei occupy a gray zone in land governance—neither fully public nor private, formally designated nor entirely abandoned. This governance ambiguity is a central challenge in recognizing IGSs as legitimate urban land uses [3,4,37]. As Włodarczyk-Marciniak et al. [26] suggest, minor design interventions and clearer maintenance regimes can significantly improve public perception without compromising the spontaneous and flexible nature of IGSs.

Furthermore, citizen participation emerges as a key solution. The study supports earlier findings that community adoption models, such as co-maintenance or stewardship programs, can simultaneously reduce the negative impacts (e.g., waste and vector risk) and strengthen residents’ place attachment and informal land use legitimacy [17,22].

This echoes earlier findings by Sun et al. [40], who examined eco-communities in Taiwan and emphasized the importance of multilevel governance involving government support, intermediary partnerships, and community engagement. While situated in a different spatial context, their tripartite framework of institutional coordination offers valuable insights for addressing the governance ambiguity of informal green spaces in dense urban settings.

Similarly to the study by Kim et al. [1], this study finds that safety, accessibility, and ecological value are central to residents’ perceptions of IGSs. However, our findings diverge in that Taipei residents showed stronger awareness of governance limitations and expressed more interest in community co-management. This may reflect Taipei’s denser urban fabric and more active civil society participation.

One critical dimension of governance ambiguity—land ownership or tenure status—was not directly addressed in the present survey. Residents’ perceptions of whether IGS parcels are public, private, or “no-man’s-land” may significantly shape their attitudes toward usage rights, co-management potential, and policy interventions. However, since the current questionnaire was finalized before this issue was identified, no specific questions on tenure awareness or assumptions were included. Future studies would benefit from incorporating such items to better understand how legal uncertainty influences community interaction with IGSs.

Based on survey responses and field observations by this study, several practical strategies may help address the following negative perceptions identified:

- ‑

- “Environmental degradation (e.g., trash accumulation, pollution) can be mitigated through community-led cleanup events and municipal micro-maintenance funding, especially in areas not covered by formal park services”.

- ‑

- “Visual disorder, often stemming from overgrowth or disorganized vegetation, could be addressed by light-touch landscape management—such as regular trimming or selective planting—without compromising the informal or spontaneous character of the site”.

- ‑

- “To alleviate safety concerns, especially in sites perceived as hidden or dark, simple measures like solar lighting, clear sightlines, and occasional patrol signage have been recommended by users”.

- ‑

- “Perceived vacancy or underutilization could be counteracted by community activation, such as installing temporary seating, play structures, or hosting pop-up events that increase visibility and frequency of positive use”.

These targeted, low-cost interventions reflect a form of “minimum viable governance” suitable for informal, fragmented green parcels and could serve as a bridge between fully planned spaces and neglected urban voids.

4.4. Towards a Hybrid Green Space Framework

This study reinforces the call for a hybrid urban green space framework—one that integrates formal and informal spaces to maximize spatial coverage and functional diversity [15,25]. Rather than relying solely on planned parks, municipal governments can adopt inclusive planning frameworks that valorize existing IGSs, support community engagement, and address site-specific risks. In compact cities like Taipei, such approaches may be particularly effective for ensuring green space equity and resilience under land scarcity conditions. These findings resonate with Simandan’s notion of urban wisdom as a balancing act between planning formality and ecological openness [29]. In this light, IGSs represent hybrid ecologies [30] that challenge rigid classifications and offer fertile ground for inclusive urban imaginaries [31].

The findings suggest that IGSs complement formal green infrastructure rather than replace it. Unlike planned parks, which offer standardized recreational amenities, IGSs serve hyperlocal and adaptive functions that are particularly valuable in land-scarce contexts. A hybrid approach that integrates the spontaneity and community-driven aspects of IGSs with the stability and predictability of formal green spaces could enhance green equity and resilience.

At the policy level, this implies updating existing land use classifications and green space inventories to acknowledge and incorporate IGS typologies, and to fund micro-scale, community-led interventions. Planning regulations should further recognize IGSs as provisional but functional components of urban green infrastructure, capable of adapting to shifting demographic and spatial dynamics. In addition, a notable methodological limitation is the absence of sociodemographic and spatial proximity data, which precluded correlation analyses between variables such as age, IGS familiarity, or residential distance. While our descriptive statistics yielded meaningful patterns, future studies should consider integrating optional demographic and locational questions—with appropriate consent—to enable richer inferential analyses and segmentation of user perceptions. This would be especially valuable for tailoring IGS governance strategies to different resident groups.

5. Conclusions

In the Taipei Metropolitan Area, the population density after urban development is much higher than expected, and the current situation of limited urban green space is not likely to increase significantly. Therefore, IGSs can provide people with space for leisure and recreation. Urban planners have always been tasked with the challenge of providing more green spaces for city residents within limited urban space and budgets. In recent years, several studies have suggested that the shortage of urban parks and green spaces can be addressed by utilizing IGSs.

According to the results of this study, the advantages of “IGSs” that the government must strengthen are as follows: increasing or maintaining rich greenery, for recreational use, promoting physical and mental health of residents. Therefore, the government can promote the IGSs to increase the amount of greening through policies to meet the expectations of the public. In addition, the leisure and entertainment functions of IGSs accessible to the community can be discussed through public participation, and the leisure functions of IGSs can be strengthened with government funding or corporate sponsorship.

In addition, according to the results of this study, people think that the most important negative impacts of IGSs are as follows: creating waste storage space, breeding grounds for mosquito vectors, and safety concerns for children. Therefore, through public participation management mechanisms (such as community adoption), the problems of clutter and mosquito breeding in IGSs can be reduced. Moreover, through security equipment and a public watch and help mechanism, the safety of children using IGSs can be ensured.

In summary, this study lists the positive and negative influencing factors of informal green spaces with reference to the relevant literature and obtains the people’s most real thoughts on IGSs through questionnaires. The findings indicate that all evaluated factors received mean scores above 3.0, suggesting that residents generally attribute at least moderate importance to both positive and negative aspects of IGSs. In particular, people believe that the most important positive impact of IGSs is to increase the amount of greening in cities and communities, and they are most worried that IGSs will become a storage space for garbage and waste. However, relevant research results have also concluded that proper management of IGSs or increased usage can help reduce the amount of garbage and crime in these spaces. Therefore, the management and maintenance of informal green spaces are very important to improve urban landscape, safety, and function.

This study reveals that while residents value IGSs for their ecological and recreational functions, concerns over safety and sanitation pose persistent challenges to their full integration into urban life. Rather than viewing IGSs as marginal or temporary, our findings underscore their potential as essential components of urban green infrastructure—particularly in space-constrained contexts. These dual perceptions reflect a broader socio-ecological tension that urban policymakers must address by designing governance frameworks that balance community empowerment with safety and maintenance protocols.

Theoretically, this study contributes to the evolving discourse on informal urbanism by empirically demonstrating how residents’ ecological, recreational, and safety perceptions shape the socio-political legitimacy of IGSs. It supports the view that informal spaces are not merely residual but function as contingent commons—informally governed areas that demand adaptive policy responses.

These findings are particularly relevant for other densely populated Asian cities facing land scarcity and fragmented green networks, offering a transferable model for integrating resident perceptions into IGS governance and participatory planning frameworks.

In sum, IGSs in Taipei are valued by residents not only for their environmental functions but also for their contributions to well-being and social cohesion. At the same time, perceived risks such as safety and poor maintenance hinder broader usage. These results suggest that IGSs should not be regarded as leftover land but as latent ecological assets requiring tailored governance. Theoretically, this study expands the discourse on informal urbanism by framing IGSs as contingent commons, where legitimacy arises through community perceptions and co-management. For other dense Asian cities grappling with similar spatial and governance constraints, our findings provide a foundation for developing hybrid green space policies that are inclusive, flexible, and grounded in local values.

In addition to enhancing residents’ recognition of ecological and social benefits, it is equally important to respond to negative perceptions through adaptive, site-specific interventions. Based on both survey feedback and on-site observations, this study recommends municipal support for light-touch maintenance, participatory design, and stewardship incentives as feasible strategies to improve user experience without requiring large-scale redevelopment or rezoning.

This study has two primary limitations. First, the relatively small sample size (n = 52) restricts the statistical generalizability of the findings. However, given the localized nature of IGSs and the exploratory focus of this research, the sample was sufficient to identify key perceptual trends and qualitative insights within the study area. Second, the study did not collect detailed SES data to avoid raising privacy concerns, especially in an urban setting where distrust or suspicion toward surveys may reduce response quality. While this limits the ability to analyze perception differences by income or class, future studies can build upon our framework with stratified sampling and expanded demographic profiling to address equity-related issues more explicitly.

Due to the exploratory nature and limited sample size of this study, caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings. Future studies should consider stratified sampling and subgroup targeting, particularly to understand the needs and experiences of vulnerable populations such as older adults and persons with mobility constraints. In addition, future studies should explore residents’ perceptions of land ownership and tenure in relation to IGSs. Understanding whether users believe IGSs are publicly owned, privately abandoned, or ambiguously governed can offer deeper insight into the socio-political legitimacy of these spaces and guide more effective community-based governance models. Future survey designs might benefit from using more explicit phrasing or visual prompts to ensure semantic clarity between environmental and esthetic perceptions of IGSs.

Moreover, this study is based on a relatively small sample size (n = 52), which limits the statistical generalizability of the findings. Additionally, detailed socioeconomic status (SES) indicators—such as income level, employment type, and housing tenure—were not collected. As a result, potential associations between SES and residents’ perceptions of informal green spaces could not be thoroughly examined. Future research should incorporate a broader range of SES variables and expand the respondent pool to better assess equity-related dimensions of IGSs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-P.C. and C.-Y.S.; methodology, T.-P.C. and C.-Y.S.; software, T.-P.C. and C.-Y.S.; validation, C.-Y.S., T.-P.C., and Y.-W.W.; formal analysis, C.-Y.S., T.-P.C., and Y.-W.W.; investigation, T.-P.C.; resources, T.-P.C. and C.-Y.S.; data curation, T.-P.C. and C.-Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.-P.C. and C.-Y.S.; writing—review and editing, C.-Y.S. and Y.-W.W.; visualization, C.-Y.S., T.-P.C., and Y.-W.W.; supervision, C.-Y.S.; project administration, C.-Y.S.; funding acquisition, C.-Y.S., T.-P.C., and Y.-W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan, under grant number 111-2813-C-004-073-H.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the ‘Scope of Human Research Exempt from Review by an Institutional Review Board’ issued by the Taiwan Ministry of Education (5 July 2012), this study qualifies for exemption. The research involved anonymous, non-interactive, and non-interventional public questionnaire surveys conducted in open spaces, with no collection of identifiable personal data. Therefore, ethical approval was not required, and no formal exemption certificate could be obtained post hoc due to institutional policy allowing only prior applications for exemption.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions related to human subject participation.

Acknowledgments

The support of the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan (Project No. 111-2813-C-004-073-H) is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, M.; Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Furuya, K. Residents’ Perception of Informal Green Space—A Case Study of Ichikawa City, Japan. Land 2018, 7, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D. Informal Urban Green Space: Residents’ Perception, Use, and Management Preferences across Four Major Japanese Shrinking Cities. Land 2017, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A. Informal urban greenspace: A typology and trilingual systematic review of its role for urban residents and trends in the literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A. Informal Urban Green-Space: Comparison of Quantity and Characteristics in Brisbane, Australia and Sapporo, Japan. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Patuano, A. Multiple ecosystem services of informal green spaces: A literature review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 81, 127849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długoński, A.; Dushkova, D. The Hidden Potential of Informal Urban Greenspace: An Example of Two Former Landfills in Post-Socialist Cities (Central Poland). Sustainability 2021, 13, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A.; Ueda, H.; Lo, A.Y. ‘It’s real, not fake like a park’: Residents’ perception and use of informal urban green-space in Brisbane, Australia and Sapporo, Japan. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A.; Garden, J.G.; Hero, J.-M. Informal urban green space: A trilingual systematic review of its role for biodiversity and trends in the literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 883–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N. Ecosystem service implementation and governance challenges in urban green space planning—The case of Berlin, Germany. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.Y.; Lin, H.T.; Ou, W.S. The Relationship Between Urban Greening and Thermal Environment. In Proceedings of the 2007 Urban Remote Sensing Joint Event, Paris, France, 11–13 April 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.Y. The Thermal Influence of Green Roofs on Air Temperature in Taipei City. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2011, 44–47, 1933–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Brazel, A.J.; Chow, W.T.L.; Hedquist, B.C.; Prashad, L. Desert heat island study in winter by mobile transect and remote sensing techniques. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2009, 98, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.Y.; Lin, Y.J.; Sung, W.P.; Ou, W.S.; Lu, K.M. Green Roof as a Green Material of Building in Mitigating Heat Island Effect in Taipei City. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 193–194, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archiciński, P.; Przybysz, A.; Sikorska, D.; Wińska-Krysiak, M.; Da Silva, A.R.; Sikorski, P. Conservation Management Practices for Biodiversity Preservation in Urban Informal Green Spaces: Lessons from Central European City. Land 2024, 13, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Furuya, K. Typology and Perception of Informal Green Space in Urban Interstices: A case study of Ichikawa City, Japan. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 8, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikorska, D.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Krauze, K.; Sikorski, P. The role of informal green spaces in reducing inequalities in urban green space availability to children and seniors. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 108, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, A.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Kronenberg, J. Eliciting non-monetary values of formal and informal urban green spaces using public participation GIS. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 160, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, E.L.; Okyere, S.A.; Frimpong, L.K.; Diko, S.K.; Commodore, T.S.; Kita, M. Planning for Informal Urban Green Spaces in African Cities: Children’s Perception and Use in Peri-Urban Areas of Luanda, Angola. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrad, A.; Kawazoe, Y. Can interaction with informal urban green space reduce depression levels? An analysis of potted street gardens in Tangier, Morocco. Public Health 2020, 186, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, O.; Lennon, M.; Scott, M. Green space benefits for health and well-being: A life-course approach for urban planning, design and management. Cities 2017, 66, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.F.; Cleland, C.; Cleary, A.; Droomers, M.; Wheeler, B.W.; Sinnett, D.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Braubach, M. Environmental, health, wellbeing, social and equity effects of urban green space interventions: A meta-narrative evidence synthesis. Environ. Int. 2019, 130, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi Farahani, L.; Maller, C. Investigating the benefits of ‘leftover’ places: Residents’ use and perceptions of an informal greenspace in Melbourne. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A.; Lo, A.Y. Memories of vacant lots: How and why residents used informal urban green space as children and teenagers in Brisbane, Australia, and Sapporo, Japan. Child. Geogr. 2016, 14, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Hooper, P.; Foster, S.; Bull, F. Public green spaces and positive mental health—Investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental wellbeing. Health Place 2017, 48, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, N.J.; Weekers, T.; Marshall, L.; D’Haeseleer, J.; Cuypers, M.; Pauly, A.; Pasau, B.; Leclercq, N.; Tshibungu, A.; Molenberg, J.-M.; et al. Five years of citizen science and standardised field surveys in an informal urban green space reveal a threatened Eden for wild bees in Brussels, Belgium. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2021, 14, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk-Marciniak, R.; Sikorska, D.; Krauze, K. Residents’ awareness of the role of informal green spaces in a post-industrial city, with a focus on regulating services and urban adaptation potential. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 59, 102236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikorski, P.; Gawryszewska, B.; Sikorska, D.; Chormański, J.; Schwerk, A.; Jojczyk, A.; Ciężkowski, W.; Archiciński, P.; Łepkowski, M.; Dymitryszyn, I.; et al. The value of doing nothing—How informal green spaces can provide comparable ecosystem services to cultivated urban parks. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyani, A.; Shackleton, C.M.; Cocks, M.L. Attitudes and preferences towards elements of formal and informal public green spaces in two South African towns. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simandan, D. The wise stance in human geography. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2011, 36, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatmore, S. Hybrid geographies: Rethinking the ‘human’in human geography. In Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 411–428. [Google Scholar]

- Gandy, M. Natura Urbana: Ecological Constellations in Urban Space; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Feltynowski, M.; Kronenberg, J.; Bergier, T.; Kabisch, N.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Strohbach, M.W. Challenges of urban green space management in the face of using inadequate data. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, E.; Jones, A.P.; Hillsdon, M. The relationship of physical activity and overweight to objectively measured green space accessibility and use. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Elands, B.; Buijs, A. Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion? Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegun, O.B. Green infrastructure in relation to informal urban settlements. J. Archit. Urban. 2017, 41, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Zhu, J. Constructing community gardens? Residents’ attitude and behaviour towards edible landscapes in emerging urban communities of China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathey, J.; Rößler, S.; Banse, J.; Lehmann, I.; Bräuer, A. Brownfields as an Element of Green Infrastructure for Implementing Ecosystem Services into Urban Areas. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2015, 141, A4015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaszkiewicz, E.; Czembrowski, P.; Kronenberg, J. Creating a Map of the Social Functions of Urban Green Spaces in a City with Poor Availability of Spatial Data: A Sociotope for Lodz. Land 2020, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simandan, D. Being surprised and surprising ourselves: A geography of personal and social change. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-A.; Zhang, X. Key Factors in the Success of Eco-Communities in Taiwan’s Countryside: The Role of Government, Partner, and Community Group. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).