Abstract

Against the backdrop of China’s urban transformation from incremental expansion to stock regeneration, community regeneration has emerged as a critical mechanism for enhancing urban governance efficacy. As fundamental units of urban systems, the regeneration of communities requires comprehensive approaches to address complex socio-spatial challenges, with public participation serving as the core driver for achieving sustainable renewal goals. However, significant regional disparities persist in the effectiveness of public participation across China, necessitating the systematic institutionalization of participatory practices. Guangzhou, as a pioneering city in institutional innovation and the practical exploration of urban regeneration, provides a representative case for examining the evolutionary trajectory of participatory planning. This research employs Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation theory, utilizing literature analysis and comparative case studies to investigate the evolution of participatory mechanisms in Guangzhou’s community regeneration over four decades. The study systematically examined the transformation of public engagement models across multiple dimensions, including organizational frameworks of participation, participatory effectiveness, diversified financing models, and the innovation of policy instruments. Three paradigm shifts were identified: the (1) transition of participants from “passive responders” to “active constructors”, (2) advancement of engagement phases from “fragmented intervention” to “whole-cycle empowerment”, and (3) evolution of participation methods from “unidirectional communication” to “collaborative co-governance”. It identifies four drivers of participatory effectiveness: policy frameworks, financing mechanisms, mediator cultivation, and engagement platforms. To enhance public engagement efficacy, the research proposes the following: (1) a resilient policy adaptation mechanism enabling dynamic responses to multi-stakeholder demands, (2) a diversified financing framework establishing a “government guidance + market operation + resident contribution” cost-sharing model, (3) a professional support system integrating “localization + specialization” capacities, and (4) enhanced digital empowerment and institutional innovation in participatory platform development. These mechanisms collectively form an evolutionary pathway from “symbolic participation” to “substantive co-creation” in urban regeneration governance.

1. Introduction

Participatory planning constitutes a paradigmatic shift in development practice, systematically integrating multi-stakeholder agencies through structured engagement mechanisms that operationalize democratic decision-making across all phases of urban interventions [1]. This collaborative approach requires the substantive participation of diverse actors, including municipal authorities, private sector developers, civic organizations, and resident populations, which materially impact the quality of life parameters and spatial justice outcomes. Over the years, participatory planning research has evolved from Advocacy Planning to actor networks and their self-organized actions [2,3,4]. In Western countries, participatory planning involves the involvement of individuals or organizations in the planning and decision-making process to varying degrees, utilizing various tools to meet the interests of stakeholders [5]. The participatory framework integrates divergent viewpoints through consensus-building mechanisms, thereby cultivating social legitimacy for proposed interventions. This collaborative methodology simultaneously addresses grassroots challenges while resolving ideological conflicts and enhancing institutional coordination, thereby contributing to the formation of sustainable communities [1,6,7].

Public participation is critical to participatory planning [8]. Civic engagement serves as the core driving force for achieving sustainable renewal objectives [9]. Since the 1960s, public participation has emerged as a critical research domain within Western academic discourse. In 1962, Davidoff and Reiner established the theoretical foundation of public participation through a pluralist lens, asserting that planning should not derive value judgments from planners’ subjective values. Building on this, Davidoff proposed Advocacy Planning, positing that urban planning embodies the expression of diverse group interests [2]. Habermas’ Theory of Communicative Action provided essential methodological grounding for public participation. At the same time, Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation offered a practical framework for analyzing institutional engagement levels in urban planning processes [10]. Currently, Western nations have developed mature theoretical frameworks for community renewal. However, a pressing global challenge persists: citizens widely perceive that their ideas and demands are systematically overlooked or undervalued by local governments [11].

China has fully entered the stock development era, where aging community renewal presents complex and arduous tasks [12,13]. While Western academia has developed mature research on community renewal and public participation, the application of collaborative planning theories and Arnstein’s Participation Ladder model in China faces challenges in institutional adaptability [14,15]. A nation’s socioeconomic context shapes public participation in planning and must adapt to its political and institutional realities. In China, research on this topic emerged relatively late, with academic attention to public participation in community renewal only gaining momentum in the late 20th century, remaining in the preliminary stages of summarizing practical experiences [16]. Furthermore, the government-led decision-making mode of urban renewal is commonly found in China [17]. Current public participation practices in China are often characterized by superficial engagement, limited efficacy, and a lack of spontaneity. The existing studies have generally positioned China’s current public participation at the symbolic stage of participation [18]. However, with rising civic awareness and evolving policy systems, shifts are emerging in community renewal practices, marked by diversified participation subjects, institutionalized deepening engagement, and tangible outcomes [19].

Therefore, systematically categorizing public participation models in research holds significant theoretical and practical value for understanding the current status, characteristics, and trends of public participation. The collision between international experiences and local practices raises critical questions: How can localized solutions be refined under a globalized lens? This remains an essential yet underexplored area requiring systematic investigation. This study aimed to explore the evolutionary path of Chinese-style participatory planning. A case study of Guangzhou provided a representative sample for analyzing the evolution of participation models, summarizing their historical features and challenges, and deriving key lessons to illuminate current practices. It further proposed an optimization strategy for public participation mechanisms in collaboration, funding, and policy systems. By offering a holistic perspective on public participation in China’s community renewal, this research examined the localized adaptation of Arnstein’s Participation Ladder theory, providing theoretical guidance and empirical insight for enhancing participatory practices in urban renewal.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Community Renewal Planning

Western community renewal planning has undergone decades of development, forming diversified theoretical and practical models [20]. In 1929, Perry proposed the Neighborhood Unit Theory, emphasizing the use of physical spatial means to address social issues. Early urban renewal focused on material spatial transformation, with primary measures including slum clearance and infrastructure upgrades. However, these approaches neglected social equity, sparking debates over “gentrification”. By the mid-20th century, community renewal shifted from physical spatial renovation to socio-cultural revitalization, giving rise to the theory of “Urban Renewal Programs”. Lewis Mumford first systematically proposed the concept of “urban renewal” in his book The Culture of Cities, advocating for sustainable urban development through historic preservation, mixed-use functions, and community activation while promoting an “organic city” model [21]. Jane Jacobs critiqued large-scale clearance plans in urban renewal, proposing theories of “community diversity” and “street vitality”. By the early 1960s, it became evident that urban renewal programs disrupted existing communities and failed to resolve core issues in central urban areas [22]. Against this backdrop, the Community Action Program (CAP) was initiated. Formally implemented through the 1964 Economic Opportunity Act, the CAP introduced new forms of citizen participation. Rather than overemphasizing physical infrastructure (“bricks and mortar”), the CAP adopted a comprehensive approach integrating social, political, economic, and spatial development, prioritizing resident engagement in community actions [23].

In the 1980s, New Urbanism emerged, placing greater emphasis on human needs and advocating for scientific and democratic public participation in planning and decision-making. Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, leading figures in American planning, founded the “New Urbanism Alliance”. Responding to post-war suburban sprawl—characterized by traffic congestion, land waste, community segregation, and social inequity—they proposed an alternative planning framework to traditional suburban models. This framework emphasized compact, human-centered, and sustainable urban design to revitalize community vitality and foster a sense of belonging. In 1979, German philosopher Jürgen Habermas introduced “communicative rationality”, a dynamic, bidirectional form of rationality grounded in intersubjective understanding [7]. John Forester was among the first to apply this concept to planning, making Communicative Planning and Collaborative Planning mainstream theoretical approaches under this framework. Communicative planning emphasizes public interest, coordinating stakeholder interests through participatory dialogue, while collaborative planning extends beyond stakeholder engagement to prioritize place-making and institutional development. In the 1990s, Robert Putnam introduced the “social sustainability” theory, focusing on community networks, resident participation, and local identity. Subsequently, influenced by climate change and globalization, urban renewal began prioritizing environmental resilience, economic diversity, and social inclusivity. Foreign community renewal planning has transitioned from singular physical transformation to the complex restructuring of socio-ecological–economic systems [24,25]. Collaborative, incremental, and negotiated renewal approaches now represent future trends in community development [26].

However, these models prioritize the collaborative co-creation of planning objectives and solutions among diverse stakeholders on an ostensibly equal basis, accompanied by decentralized decision-making authority [27]. Within localized urban governance contexts, development goals jointly established by heterogeneous actors frequently manifest as overly idealized constructs [28]. Consequently, this study aimed to investigate the evolutionary trajectories of public participation models in China’s community renewal practices, grounded in its specific institutional and cultural contexts, to establish replicable and scalable operational paradigms.

2.2. Public Participation Models

In the 1960s, Western societies faced significant social contradictions, severe class stratification, and a surging civil rights movement, leading to growing skepticism toward the logic of rational planning. This period witnessed a proliferation of theoretical research on public participation. In 1965, Davidoff proposed the “Advocacy Planning” theory, advocating bottom-up public decision-making and marking the first substantive introduction of public participation in planning. Subsequently, Lefebvre’s The Right to the City (1967) emphasized urban rights as a fundamental civic entitlement, framing them as “expressions of destiny”. In 1969, Arnstein categorized public participation into three tiers—dominant, symbolic, and non-participation—elaborating on how differing levels of involvement lead to distinct implementation outcomes [10]. The message was that the greater the participation was, the better the chances for improving governance would be [29]. Western participatory planning theories evolved progressively from Advocacy Planning to Communicative Planning and Collaborative Planning, increasingly emphasizing multi-stakeholder engagement, the coordination of diverse interests, and institutional development for participatory planning.

Over decades of development, many European and American “community planning” processes have advanced to stages of deep participation or even “decision-making participation”. The evolving roles of multiple actors in community renewal planning have gradually decentralized decision-making power from governments to residents. From setting planning objectives to selecting and implementing proposals, public participation mechanisms now permeate every stage of the planning process. Public renewal stakeholders—including government agencies, residents, community planners, and various grassroots organizations—jointly drive community renewal. The U.S. model exemplifies this shift through Community Development Corporations (CDCs), which have gradually assumed planning authority [30]. CDCs not only access direct government funding and policy incentives but also exercise commercial operational autonomy. Concurrently, involvement by third-party organizations has become institutionalized. Nationwide, Non-Profit Organizations (NPOs) and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) have emerged as key actors in public participation, often mediating stakeholder engagement through intermediary entities. In the U.S., “Community Economists” participate in design, event organization, and implementation. Meanwhile, the UK employs “Community Participation Officers”, publicly appointed by local authorities to act as bridges between stakeholders, fostering collaboration and communication. These models reflect a global trend toward diversified, inclusive, and institutionally embedded participatory practices in community renewal.

While Western scholarship has established a mature body of research on community renewal and public participation, theories such as Collaborative Planning and Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation encounter institutional compatibility challenges when applied to China’s governance context. The ladder theory’s core emphasis on “power redistribution” as the determinant of participation depth faces adaptive constraints within China’s state-centric governance paradigm. This necessitates contextually calibrated participation intensities across diverse policy domains [31]. By contrast, domestic research emerged relatively late, with substantive academic engagement in public participation only commencing in the late 20th century. Current scholarship remains predominantly focused on preliminary empirical generalizations derived from fragmented practices [32]. Achieving theoretical innovation and pragmatic breakthroughs requires the critical localization of Western frameworks through deep institutional embeddedness.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

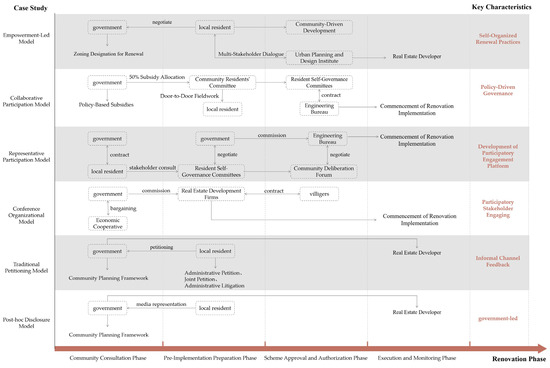

This study focused on the evolutionary logic of the public participation mechanism itself, with the forms and effectiveness of public participation as the primary research objects, forming three stages and six models (Table 1): the Post Hoc Disclosure Model, Traditional Petitioning Model, Conference Organizational Model, Representative Participation Model, Empowerment-Led Model, and Collaborative Participation Model. Centered on the public, this classification method illustrates the evolutionary mechanism of public participation, progressing from symbolic expression to substantive governance through dimensions such as forms of participation, substantive decision-making empowerment, and the activation of social capital.

Table 1.

Descriptive data of the case study area. Source: the authors.

As a typical representative of the Post Hoc Disclosure Model, the redevelopment work of the Enning Road Project has sparked widespread public discussion. It stands as a classic case of old urban renewal in Guangzhou. The Xinyue 10 and 12 Buildings Renewal Project, a typical example of the Traditional Petitioning Model, reflects the usual pattern of resident-government confrontation amid redevelopment disputes. The Pazhou Village Renewal Project, a key case of the Conference Organizational Model, represents one of the first batches of urban village redevelopment projects following the introduction of the Three Olds Reform Policy, exemplifying how the public participates in redevelopment through voting rights under policy guidance. The Dongcheng Huayuan Renewal Project, a representative of the Representative Participation Model, illustrates a typical pattern of government-led redevelopment involving resident representatives. The Beiliyuan Old Community Renewal Project, a prime instance of the Collaborative Participation Model, highlights cooperation between neighborhood committees and the public. The Cluster Street Building No. 2 Renewal Project, a pioneering case of the Empowerment-Led Model, is Guangzhou’s first pilot project for multi-owner self-financed redevelopment.

3.2. Analysis Method

This study employed field research, semi-structured interviews, and questionnaire surveys. Through methods such as direct observation and the provision of third-party information, it sought to understand the redevelopment process and integrate perspectives from the authors, government agencies, enterprises, and property owners. Primary on-site survey data collection ensured informational authenticity and reliability.

4. Evolutionary Patterns of Community Regeneration with Public Participation

4.1. Symbolic Participation Stage: Government-Led Reconstruction

(1) Post Hoc Disclosure Model

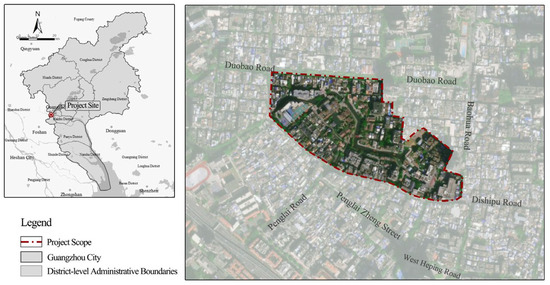

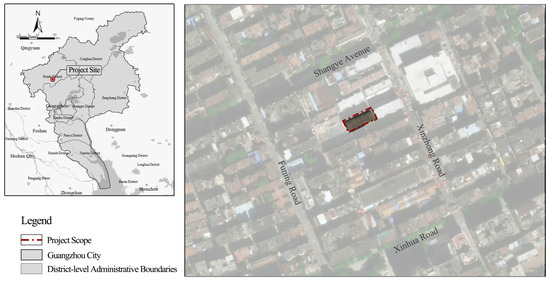

The Post Hoc Disclosure Model refers to a system where power is entirely concentrated in the hands of the government, with the public reduced to passive recipients or subjects to be educated through public announcements. In this model, urban redevelopment projects are government-led, with the public lacking substantive influence over decision-making and merely complying with administrative demands. Public feedback, whether through formal or informal channels, serves to maintain superficial legitimacy rather than advance democratic decision-making. The Enning Road Redevelopment Project in Guangzhou exemplifies this approach. Located in the core area of the Liwan Old City District, Enning Road boasts Guangzhou’s most intact and longest arcade street (qilou), flanked by clusters of Lingnan traditional residences such as Xiguan residences (traditional Lingnan-style row houses) and Zhutong houses (bamboo-tube vernacular dwellings), covering approximately 113,700 m2. In 2006, the Enning Road redevelopment was designated as a pilot project for Guangzhou’s urban renewal efforts, marking the official launch of reconstruction (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area in Guangzhou. Source: the authors.

Figure 2.

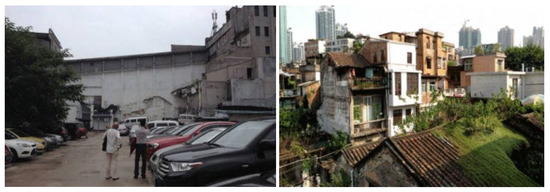

Current situation before regeneration. Source: Coenosis, 2019, available at https://www.ateliercns.com (accessed on 22 May 2019).

In the project’s initial phase, the government prioritized its objectives, with the redevelopment plan predominantly government-led and public participation severely limited. Residents were excluded from decision-making processes. The 2007 demolition plan sparked a protracted “demolition stalemate” due to residents’ dissatisfaction with compensation and reluctance to relocate. It also triggered a “cultural preservation battle” as experts, volunteers, social organizations, and citizens opposed large-scale demolition and the destruction of historic neighborhood character. A December 2009 “New Express” article titled “Enning Road Redevelopment Cannot Proceed Covertly” and “Public Consultation Must Precede Planning” heightened public attention, drawing focus to contentious issues. A coalition of 183 residents submitted a joint petition demanding an immediate halt to demolitions and the suspension of the redevelopment plan. From 2006 to 2009, the project underwent repeated planning revisions. Throughout this period, residents had limited channels through which they could directly influence planning decisions. Post-planning public hearings remained their primary formal avenue for feedback. However, this mechanism failed to address residents’ grievances, prompting many to resort to letters and petitions. While historical conservation planning in the Enning Road proposal was gradually refined, land acquisition processes had already commenced, resulting in severe damage to numerous heritage buildings. Delayed interventions rendered later conservation measures meaningless (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Completion of construction. Source: the authors.

During the Enning Road redevelopment, residents faced restricted avenues for direct participation in decision-making, and no public engagement platform was established. Traditional media outlets, such as newspapers and television, played a pivotal role in disseminating government decisions, with residents relying heavily on these sources for updates on projects. The media also provided a platform for residents to voice their demands; for instance, joint public petitions by Enning Road residents gained widespread attention through media coverage, compelling both the government and the public to address the project’s issues. Nevertheless, public feedback had a minimal impact on the redevelopment process, resulting in prolonged delays, inefficiencies in community renewal, and significant obstacles to achieving equitable outcomes.

(2) Traditional Petitioning Model

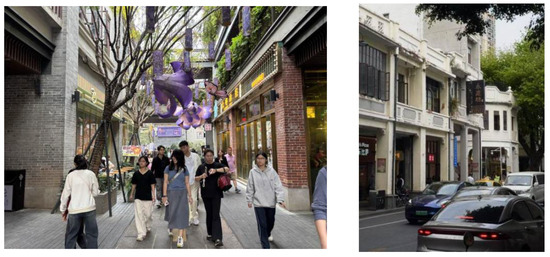

The Traditional Petitioning Model refers to residents’ use of formal or informal channels—such as administrative petitions, joint letters, or administrative litigation—to voice grievances to the government. This adversarial and passive participation pattern is typical in urban renewal disputes. The Xinyue 10 and 12 buildings in Liwang District, constructed in 1995 as reinforced concrete structures, exemplify this dynamic. On 1 October 2002, after a court ruling by the Liwang District People’s Court, the Guangzhou Gujin Auction House organized the sale of these properties. Guangzhou Baifucheng Jinfat Property Management Co., Ltd. exclusively handled publicity and marketing for the buildings as commercial housing. Homeowners did not receive property ownership certificates approved by the Municipal Land and Resources Bureau until May 2003 (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Location of the study area in Guangzhou. Source: the authors.

Figure 5.

Current situation before regeneration. Source: New Express Daily, 2008, available at https://www.xkb.com.cn/ (accessed on 12 May 2008).

In September 2007, the complex was designated for demolition as part of the Enning Road Hazardous Housing Renewal Project. Residents contested the structural appraisal results, arguing that the 1995-built reinforced concrete buildings remained structurally sound and fit for habitation and criticized the government for withholding appraisal documentation. Some homeowners emphasized that the structures did not meet the criteria for “hazardous dilapidated housing”. While the government offered monetary compensation or relocation resettlement, it rejected on-site replacement options. Residents demanded “in-situ exchange”, warning that relocation would escalate living costs and fracture community ties. Repeated requests for disclosure of demolition planning documents went unanswered, fueling suspicions about the legality of government decisions.

Residents attempted to revoke the demolition permit through legal channels, but proceedings were protracted. In this context, over 80 homeowners jointly petitioned the National People’s Congress, alleging that the Enning Road renewal project’s demolition of Xinyue 10 and 12 violated the fundamental principles of the Property Rights Law. Key procedural flaws—including a lack of transparency, insufficient homeowner consultation, and uncompromised compensation standards—highlighted weak protections for property rights under the Property Rights Law. The core issue lay in the government’s unilateral control over demolition permits, compensation, arbitration, and enforcement, directly contradicting the Property Rights Law’s principle of equal protection.

The protest over Xinyue 10 and 12 underscores homeowners’ dilemma when facing rights violations without effective legal recourse. To defend their interests, residents resorted to cross-administrative petitions, administrative litigation, and other escalated measures. However, such confrontational tactics not only hindered urban renewal progress but also burdened administrative bodies, undermining societal harmony and stability.

4.2. Collaborative Participation Stage: Co-Creation Practices

(1) Conference Organizational Model

The Conference Organizational Model refers to a governance framework in which procedural voting rights are endowed to village collective representatives or community resident representatives through structured decision-making forums, specifically addressing core issues such as compensation schemes and urban renewal plans. This participatory mechanism grants the public substantive influence over redevelopment proposals while retaining ultimate decision-making authority with governmental entities. The Pazhou Village renewal project exemplifies this policy-driven participation model under Guangdong Province’s “Three Olds Transformation” initiative (a provincial urban renewal program). As one of Guangzhou’s largest urban villages, Pazhou spans approximately 757,639 m2 with a gross floor area of 1,850,000 m2. Located along the southern bank of the Pearl River, its transformation demonstrates how procedural participation mechanisms can operationalize public input in legally mandated renewal processes while maintaining state-led developmental priorities (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Location of the study area in Guangzhou. Source: the authors.

Figure 7.

Current situation before regeneration. Source: Guangzhou Urban Planning Exhibition Center, 2022, available at https://www.upec.gz.cn/ (accessed on 31 March 2022).

In 1998, the government initiated the transformation of Pazhou Village through land acquisition for the construction of the Guangzhou International Exhibition Center. This established the spatial scope and planning framework for urban renewal. By 2002, the village had completed the full transition from an agricultural to an urban residency and administrative structure, prioritizing the transformation of socioeconomic attributes before physical redevelopment. This process aimed to dilute the urban–rural dualism. Concurrently, the village committee was dissolved and replaced by the Pazhou Economic Union, a collective economic entity responsible for managing assets and negotiating compensation packages with developers and government agencies. Through scientifically designed compensation mechanisms, the Union safeguarded villagers’ interests by securing housing subsidies and land acquisition compensation.

During the planning and preparation phase in August 2008, the Pazhou Economic Union’s redevelopment proposals and compensation plans received formal approval from village representatives. By October 2009, the Guangzhou Land Development Center conducted market-oriented land leasing, incorporating redevelopment requirements as competitive bidding criteria. The state-owned China Vanke Group ultimately acquired the 757,639 m2 site through a public auction, marking a transition from compulsory demolition to agreement-based expropriation under market mechanisms. This privatization approach reduced governmental intervention in non-public-welfare land acquisitions while formalizing the protection of villagers’ rights. During the decision implementation phase, commissioned by the Economic Union, Vanke Group implemented compensation measures through public Q&A sessions and legal consultation forums. From March to September 2010, the project achieved a 100% household agreement rate, enabling comprehensive demolition by the end of 2010. Reconstruction commenced on 28 September 2010, with total investment exceeding CNY 20 billion. The redevelopment achieved dual objectives: maximizing the benefits for villagers while driving industrial upgrading in Guangzhou (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Completion of construction. Source: the authors.

The procedural participation mechanisms in urban renewal have benefited from institutional refinements under Guangzhou’s “Three Olds Transformation” policy framework and market-oriented land acquisition innovations. While Pazhou Village’s renewal model retains the overarching “government-led, market-driven” paradigm, the government’s dominant role has evolved from “coercive authority” to “negotiated adjustments” within marketized land acquisition systems. During the consultation phase, this has manifested through joint negotiations between government authorities and Urban Village Economic Unions to adjust compensation packages, effectively balancing villagers’ interests with the imperatives of urban development. Market forces are systematically introduced during implementation phases to execute plans aligned with government planning directives and community feedback. This hybrid governance model emphasizes villagers’ participation rights and decision-making authority, leveraging substantial social capital to address Guangzhou’s critical funding gap for urban renewal while rapidly transforming outdated urban areas. However, practical challenges persist in obtaining unanimous consent due to villagers’ concerns about the adequacy of compensation and the credibility of the developer, which frequently stall the voting process.

(2) Representative Participation Model

The Representative Participation Model emphasizes the roles of community leaders in conducting resident needs assessments, incorporating public opinions into design iterations through multi-stage consultations, and overseeing implementation processes. The Dongcheng Huayuan renewal project exemplifies this approach within Guangzhou’s evolving governance paradigm. As an aging residential complex in the core area of Tianhe District (No. 183 Zhongshan Dadao Middle Road, Huangpu Avenue, Tianyuan Subdistrict), Dongcheng Huayuan comprises 29 stairwells spanning 67,191 m2, covering an area of 3.03 hectares. Built in the early 1990s, it houses 946 households (approximately 2585 residents), with elderly and children, each constituting one-third of the population (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Location of the study area in Guangzhou. Source: the authors.

Figure 10.

Current situation before regeneration. Source: China Construction Third Engineering Bureau Group South China, 2019, available at https://3bur.cscec.com (accessed on 20 September 2019).

In the consultation phase (2018), the Tianyuan Subdistrict Office established the Construction Management Committee (CMC) through grassroots mobilization, coordinating environmental remediation before formal renewal. Traditional policy dissemination methods, such as building-posted notices, collected resident feedback with a 2/3 approval threshold required for proposal finalization. However, limited community engagement and the absence of site-specific impact assessments generated resistance among residents whose interests were affected, particularly those facing interference from policy requirements. During the scheme development phase (2018), affected rooftop residents proactively mobilized, establishing autonomous groups through new media platforms. Their strategic actions included collecting legal documentation to facilitate negotiations with public agencies, building coalitions across residential units, and circulating petitions to secure policy modifications. Collaborative governance emerged through co-design platforms involving contractors (China Construction Third Engineering Bureau), street offices, and resident representatives, alongside simultaneous micro-renovation and elevator installation planning with resident co-financing (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Completion of construction. Source: the authors.

Implementation mechanisms integrated digital participation (utilizing WeChat group meetings for weekly progress reviews and issue reporting), financial hybridity (15% resident self-funding), and institutional linkages (grassroots governance institutions that bridged administrative and community-driven processes). This case demonstrates Guangzhou’s shift toward negotiated urban renewal, where bottom-up pressures—such as residents’ use of legal frameworks and digital tools to advocate for policy adjustments—systematically alter top-down policy trajectories. Theoretically, it highlights adaptive governance in China’s hybrid urban renewal system, the transformative potential of resident self-organization under regulatory constraints, and the role of digital infrastructure in enhancing procedural legitimacy.

4.3. Empowered Participation Stage: Multi-Stakeholder Synergy

(1) Collaborative Participation Model

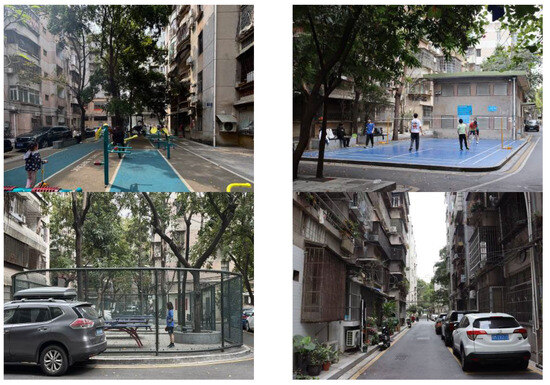

The Collaborative Participation Model breaks away from government-dominated approaches, empowering residents as rights-bearing stakeholders to engage substantively in renewal processes. This framework establishes equal negotiation platforms among governments, residents, enterprises, and social organizations or facilitates cooperation between neighborhood committees and residents to guide public involvement. By enabling full-cycle participation—from initial consultation to design and construction—the model fosters collaborative governance communities driven by mutual benefits. The renovation of the Beiliyuan Old Community in Yile Community, Panyu District exemplifies this approach through policy-driven collaboration between neighborhood committees and residents. The 35-year-old complex, spanning 160,000 m2, faced critical issues before the renovation, including damaged stairwells, aged facades, and elevator deficiencies, all of which severely impacted residents’ quality of life (Figure 12 and Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Location of the study area in Guangzhou. Source: the authors.

Figure 13.

Current situation before regeneration. Source: Panyu Integrated Media Network, 2025, available at https://www.pycmc.net/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

In 2024, Panyu District revised and issued the Guidelines for Direct Resident Funding Participation in the Building Renovation of Old Communities, introducing policy incentives and a cost-sharing mechanism. The guidelines stipulate subsidies of 80% for basic improvement projects and 50% for enhancement projects, with capped government contributions. For instance, residents would only need to contribute CNY 1000–2000 per household for elevator installations, with the remainder subsidized. This policy drastically reduced financial burdens, thereby boosting willingness to participate. Standardized unit prices (e.g., guidance rates for stairwell repairs) were provided to prevent contractors from inflating costs. Additionally, residents were required to raise initial funds, with subsidies disbursed post acceptance to ensure fund efficiency.

During the consultation phase, community Party volunteers and neighborhood committee staff collected residents’ core demands—such as door updates, access control upgrades, and stairwell repairs—via online surveys and door-to-door visits (covering all households). Elderly mobility challenges, particularly elevator shortages, were prioritized. In the planning phase, two resident representatives per building formed an autonomous core team responsible for fund management, contractor negotiations, and progress oversight. Real-time fund progress was disclosed via WeChat groups to ensure transparency. Contractors incorporated residents’ customized needs such as optional facial-recognition upgrades beyond subsidy limits. During implementation, a “resident co-supervision” model was adopted, with building representatives monitoring construction quality. For example, the representative of one building promptly negotiated corrections when tile laying deviated from design specifications (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Completion of construction. Source: the authors.

By significantly lowering financial barriers through high subsidy ratios, the model reconfigures participation from state-dominated toward resident-driven models. Residents strengthened neighborhood trust through joint decision-making and collaborative oversight. Neighborhood committees fully leveraged grassroots autonomy by organizing forums, establishing feedback platforms, and conducting policy outreach to galvanize participation. Guided by the principle of “joint construction, co-governance, and shared benefits”, the project advanced the orderly implementation of facility upgrades and public space optimization. The Beiliyuan case demonstrates that renewal transcends physical space transformation—it represents a systemic enhancement of community governance capacity. This “policy guidance + resident autonomy + technical support” model offers a replicable template for other regions.

(2) Empowerment-Led Model

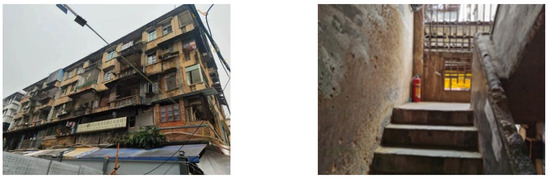

The Empowerment-Led Model emphasizes resident-led urban renewal through policy-backed authority, granting residents or their representatives’ substantive control over all stages—from needs assessment and design to construction and long-term management. Cluster Street Building No. 2 in Huadu District, Guangzhou serves as the city’s first multi-owner self-funded renewal pilot project, initiating a bottom-up “self-demolition and self-reconstruction” exploration. Constructed in the 1970s, this 25-unit, 1750.20 m2 residential building in Huadu’s old urban core was identified as hazardous, with only a few residents remaining (Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 15.

Location of the study area in Guangzhou. Source: the authors.

Figure 16.

Current situation before regeneration. Source: Guangzhou Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau, 2025, available at https://ghzyj.gz.gov.cn/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

During the preparation phase, aligned with Guangzhou’s Hundred Million Projects requirements, the 2023 urban renewal initiative for the Guangzhou North Railway Station East Area included Cluster Street Building No. 2 as a pilot for multi-owner hazardous housing redevelopment. In August 2023, after resident consultations revealed opposition to minor repairs, homeowner Mr. Xu proposed a demolition and reconstruction plan, adopting an “autonomous renewal with self-raised funds” model. To facilitate this, the Guangzhou Municipal Housing and Urban–Rural Development Bureau issued the Guangzhou Hazardous Housing Renovation Implementation Measures (Trial) in 2024, providing policy support for resident-led updates, including streamlined permitting and subsidies. The district-level Pilot Scheme for Hazardous Housing Demolition and Reconstruction in the North Railway Station East Area further enabled the collective ownership of hazardous housing redevelopment through owner-led initiatives.

For funding and consensus-building, residents collectively bore renovation costs, prepaying CNY 4600/m2 into a jointly managed account supervised by the neighborhood committee. This mechanism, supplemented by policy incentives such as public housing fund withdrawals and targeted subsidies for low-income households, raised approximately CNY 8 million from residents (averaging CNY 300,000 per household). Government support included design cost subsidies and expedited approvals. Over nine resident assemblies and 48 door-to-door negotiations, the neighborhood committee and the Guangdong Architectural Design Institute addressed disputes, refining plans to accommodate residents’ needs. Construction commenced on 18 March 2024, with developer-led “demolish-and-rebuild” work that expanded the total floor area by 1870.43 m2, allocated proportionally to the owners. By 11 January 2025, the renovated building was completed and occupied (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Completion of construction. Source: the authors.

Cluster Street’s owner-driven model alleviates fiscal burdens on governments while empowering residents with substantive decision-making authority. However, challenges persist: self-raising funds require complex mechanisms, such as “direct contributions + public revenue transfers + housing fund withdrawals”, necessitating government subsidies to alleviate financial pressure. Cross-sector professional collaboration has also proven critical to accelerating progress. Comparable projects, such as Nanjing’s Hujilu Block No. 4 residential tower, faced delays of seven to eight years due to fragmented coordination. For multi-owner renewal to succeed, policy frameworks must standardize procedures, as seen in Cluster Street’s template of “resident autonomy + technical support + policy alignment”. This case underscores the potential of empowerment-led models to redefine urban renewal through collective agency, though systemic refinements are essential for scalability.

5. Discussion

5.1. Characterization of Participation Models

(1) Evolution of Stakeholder Roles

The evolution of public participation models in community renewal planning exemplifies China’s modernization of grassroots governance, profoundly reflecting the synergistic development of governmental function restructuring, social capital activation, and multi-subject governance (Figure 18). Throughout this process, the government’s role has transitioned from an “omnipotent dominant actor” to an “institutional provider”. Gradually withdrawing from operational implementation, governments have devolved implementation authority to community self-governance organizations while concentrating on core functions such as planning formulation and quality supervision, thereby creating institutional space for public engagement. Historically serving as the primary driving force, the market has progressively shifted from decision-making roles in micro-renovation and resident-led renewal projects to construction contractor roles. As key governance coordinators, third-party actors exhibit distinct stage-based characteristics. Initial informal mediation by media platforms initiated public participation, which evolved into formalized coordination entities, such as neighborhood committees, resident self-governance groups, and government liaison offices. These coordinators integrate planning consultation, dispute mediation, and fund supervision functions, emerging as indispensable pillars in community renewal processes.

Figure 18.

Summary of multi-stakeholder interaction process in community renewal. Source: the authors.

(2) Paradigm Shifts in Public Participation Models

Community renewal participation models in China are transitioning from “symbolic involvement” to “proactive engagement”, with Guangzhou establishing a comprehensive, deep-rooted, and sustainable participation mechanism. Three transformative features characterize this shift. First, participation has shifted from “passive responsiveness” to “active co-construction”, rooted in rising civic awareness and citizens’ assertion of their rights and pursuit of collective interests. Growing demands for high-quality public spaces and environments drive residents to leverage their agency for material and spatial improvements. Second, participation has evolved from “fragmented consultation” to “whole-cycle empowerment”, extending beyond traditional consultation stages (e.g., opinion solicitation) toward resident-led process dominance. This transformation underscores the organizational capacity of resident groups, which act as critical intermediaries between residents and governments. The efficacy of public participation directly correlates with the proactivity and competency of these organizations. Third, participation has transitioned from “one-way communication” to “collaborative governance”, supported by policy frameworks and decentralized authority, enabling residents to co-lead renewal initiatives. Governments now coordinate multi-stakeholder collaborations involving residents, community planners, and neighborhood organizations, fostering shared decision-making.

(3) Stage-Specific Characteristics of Role Transformation

Despite progress toward proactive participation, China’s community renewal engagement remains distant from Arnstein’s highest tier of “citizen control” in participatory democracy. Western models emphasize universal citizen involvement across all phases of planning, approval, and implementation. In contrast, Chinese residents still exhibit limited decision-making capacity due to insufficient professional knowledge and a lack of expertise in planning-related matters. Complex renewal projects—such as the comprehensive renovation of Jiqun Street No. 2 and the micro-renovation of the Beiliyuan Community—typically remain led by neighborhood committees or design institutes, necessitating third-party facilitation [33]. Moreover, China lacks standardized procedures for proactive participation, leaving initiatives in a spontaneous state that hinders scalable implementation.

Dynamic democracy management is crucial across project phases [34]. During the consultation phase, maximizing resident participation ensures the precise expression of needs, meticulous articulation of demand, and broad mobilization of the project, which are vital for securing social legitimacy and facilitating smooth project initiation. In the decision-making phase, collaboration between residents and technical teams (planners, architects, engineers) becomes essential. Through multi-party negotiations, benefit balancing, and scheme optimization, strategies emerge that align urban development goals with the needs of local livelihoods. By the implementation phase, residents transition to supervisory roles, monitoring progress, quality, safety, and fund utilization via project meetings, site inspections, and satisfaction surveys. Tailored strategies must balance power redistribution, governance efficiency, and social costs across spatial attributes and renewal models. Power redistribution necessitates dynamic adjustments based on stakeholder capacities, governance efficiency requires institutional innovation and capacity building, and social costs necessitate policy instruments and market mechanisms for adequate control.

5.2. Institutional Optimization Pathways

(1) Staged Characteristics of Collaborative Mechanisms

In urban renewal mobilization processes, neighborhood committees leverage their administrative advantages to serve as critical connectors between governments, markets, and residents. In the Beiliyuan Old Community renovation project, the street-resident governance model emphasized strengthening the coordinating role of neighborhood committees. Through door-to-door resident engagement, these committees effectively galvanized participation. Their facilitation manifested in two dimensions: first, breaking information silos among residents to ensure transparency; second, organizing residents into collective entities—given the limited autonomy of individual citizens—to amplify their influence through organized action.

During the preparation phase, cultivating local capacity and establishing resident-led organizations became priorities. To address residents’ deficits in technical expertise, a dual-track ‘localized-professionalized’ support system emerged. This included assigning certified planners for on-site services and institutionalizing a collaborative workflow where resident proposals underwent professional refinement before joint approval. Concurrently, nurturing grassroots technical talent—identifying and empowering community leaders—helped form locally rooted “capable person networks”. These networks became pivotal nodes within neighborhood social structures, alleviating workload pressures on neighborhood committees. Additionally, leveraging building-level hierarchies or administrative networks to elect resident representatives ensured broad participation in the decision-making process for renewals. As multi-stakeholder collaboration expanded, a hybrid framework integrating “community planners + local capable organizations + volunteers” coalesced as the primary public participation force. To incentivize involvement, policies offered stipends and professional title incentives. For instance, Beiliyuan’s renovation relied on building representatives to form autonomous resident groups whereas Jiqun Street No. 2 leveraged capable networks to advance renewal.

In the decision-making stages, stakeholders collectively upheld shared values and objectives to achieve “joint decision-making”, driving sustainable community development [35]. To balance efficiency and inclusivity, dual-track online-offline deliberation platforms emerged, enabling information transparency and universal access. As projects progressed, community planners transitioned from government-aligned facilitators to neutral mediators balancing diverse interests. Local capable organizations and volunteers, drawing on their community embeddedness, further bridged gaps by mediating conflicts and fostering communication among stakeholders.

(2) Funding Mechanisms

Historically, residents’ financial vulnerability in renewal projects has stemmed from inadequate capital investment and profit-sharing structures, which have undermined their bargaining power. Combined with monolithic financing models and low returns, funding shortages have intensified. Thus, establishing multi-party cost-sharing mechanisms has become essential to protect public interests while alleviating fiscal burdens. In Jiqun Street No. 2, a tripartite “government-guided + market-operated + resident-contributed” model enabled self-funded renewal, exemplified by resident-led architectural modifications such as elevator additions for accessibility for the elderly. To diversify funding, tiered subsidy systems were implemented: full public funding for low-income households and blended support (subsidies, flexible housing provident fund withdrawals, and public revenue offsets) for others. Transparent fund management was ensured through cloud-based platforms, enabling phased disbursements and real-time expenditure tracking.

However, Jiqun Street’s single-building focus revealed scalability challenges. Expanding renewal scope across larger areas demands innovative financing to stabilize funding sources. Tapping into post-demolition land redevelopment potential, monetizing public service facilities (e.g., kindergartens, elderly care centers), and optimizing commercial space operations emerged as viable strategies. These approaches not only secure capital but also incentivize private sector participation. For example, Pazhou Village’s systemic redevelopment leveraged land value appreciation from commercial space operations, creating a market-driven return mechanism that balanced public benefits with private investment—a scalable model for large-scale urban renewal.

(3) Policy Frameworks

Institutional innovation requires a lifecycle policy framework comprising front-end incentives, process safeguards, and post-implementation rewards. This framework necessitates a clear delineation of roles and synergistic cooperation between government agencies, market actors, and community representatives throughout each stage. During the initiation phase, fiscal subsidies and floor area ratio incentives encourage resident participation while standardized technical guidelines and cost controls provide actionable tools. Standardized technical guidelines and cost controls mandated by the government ensure market actors have the actionable tools to comply efficiently. In implementation, streamlined multi-department approval mechanisms reduce bureaucratic hurdles. To address knowledge gaps, a planner + community advisor support system offers technical assistance under government-backed risk mitigation. Clear risk-sharing agreements define responsibilities: the government for policy and exogenous risks, the market for construction, and communities for adaptation. For sustainability, expedited property registration and dynamic property fee adjustments are paired with tax breaks and grants to consolidate gains.

5.3. Theoretical Innovations in Participatory Planning

Since its inception in 1969, Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation has remained a foundational framework for analyzing public engagement. The theory categorizes citizen participation into three tiers—”non-participation”, “symbolic participation”, and “substantive participation”—further subdivided into eight rungs, emphasizing power redistribution as the criterion for evaluating participatory depth. Rooted in Western democratic ideals and societal openness, Arnstein’s model faces adaptability challenges within China’s administrative governance framework, necessitating localized theoretical innovation. Chinese participatory practices predominantly manifest as government-led collaborative governance rather than power delegation [36]. For instance, Guangzhou’s “Joint Creation Workshops” grant residents design input but retain final decision-making authority within government approval processes, reflecting “limited empowerment”. China’s participatory ladder framework emphasizes multi-subject collaboration, constructing a governance network integrating government, market, society, and citizens. In urban renewal, residents—as property owners—hold legitimate rights to participate in decision-making and implementation, with their voices requiring due consideration. However, from a strategic, systemic perspective, while residents play critical roles in renewal processes, they lack comprehensive control over urban renewal trajectories. Governments, leveraging macro-level planning, policy design, and resource allocation, remain core drivers, ensuring orderly, efficient, and sustainable urban development.

The communicative and collaborative planning paradigms advocated in Western academia during the 1980s emphasized multi-subject equality in goal-setting and decentralized decision-making, prioritizing consensus-building. Arnstein’s ladder implies an idealized “perfection” at its highest rung [24]. Yet, practical implementation reveals trade-offs: even lower-tier participation may yield tangible benefits while high-level engagement risks inefficiencies and the “elite capture” of marginalized groups. Despite China’s shift from rational, economy-focused planning to balanced socioeconomic and environmental development, collaborative planning in practice continues to rely on government oversight, with local administrations serving as mediators of stakeholder interests and facilitators of public participation.

Funding mechanisms for participatory renewal exhibit pluralism, directly influencing power distribution and motivational structures. Traditional models rely on fiscal transfers, policy-based financial instruments, and developer-driven social capital, prioritizing exogenous capital and economic growth. Such mechanisms often marginalize public interests, manifesting as spatial justice issues such as the excessive compression of public spaces and inequitable resource allocation, which can trigger disputes related to gentrification. Contemporary renewal practices are transitioning toward paradigm shifts: community foundations and resident-led cost-sharing models empower residents in capital negotiations, safeguarding their interests while balancing economic, social, and environmental outcomes. Institutionalized channels now ensure resident demands are addressed, reaffirming the public nature of renewal.

The Joint Creation philosophy positions residents as primary actors, with governments, planners, and communities working together to advance urban planning. This model redefines planners’ roles from technical executors to multi-stakeholder coordinators tasked with reconciling public demands and broader societal interests. Simultaneously, governments transform from dominant planners to “wisdom-guided” facilitators, designing policy frameworks, safeguarding rights, and steering implementation through flexible governance. Residents gain comprehensive rights, including demand articulation, participation in decision-making, and oversight over implementation.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to explore the evolutionary path of participatory planning and summarize the lessons from its patterns, thereby providing suggestions for optimizing the public participation mechanism. As a pioneering city in urban renewal system innovation and practical exploration, Guangzhou offers typical cases for studying the evolutionary path of participatory planning. These cases profoundly reveal the core role of public participation in balancing efficiency and fairness, as well as short-term interests and long-term sustainable development, serving as a window to observe the modernization transformation of China’s grassroots governance. This study constructed a systematic theoretical framework for public participation in community renewal. Localizing the Participation Ladder model reveals the formation mechanism of the “responsibility-based participation paradigm” in China’s administrative-led urban governance. Unlike the “rights-first principle” emphasized by Western communitarianism, China’s participation model is not a transfer of rights but a collaborative assumption of responsibilities among property owners. In practice, this is manifested as the diversification and improvement of efficiency in participation models. This model transforms the Western “rights transfer” into a Chinese-style “joint” responsibility-sharing. Its essence lies in the localization reconstruction of Western public participation theories in public affairs governance.

This study employed Arnstein’s Participation Ladder theory, analyzing the evolution of the participation mechanism in Guangzhou’s community renewal over the past nearly four decades through literature analysis and comparative case studies. The research found that there are three major mode transitions in public participation: the participation subjects have shifted from “passive response” to “active construction”, the participation stages have been upgraded from “fragmented intervention” to “full-cycle empowerment”, and the participation methods have been iterated from “one-way transmission” to “collaborative governance”. On the one hand, the transformation of Guangzhou’s public participation model is driven by policy innovation. From an institutional void to institutional construction, the Guangzhou municipal government has continuously built formal channels for public participation and explored diverse participation models. On the other hand, it is due to the rise of public awareness. From self-right protection to the pursuit of a better environment, the public’s willingness to participate in community renewal has been continuously enhanced, promoting its involvement in community renewal.

During Guangzhou’s community renewal process, the public participation model has undergone multiple stages of evolution. In the symbolic participation stage, although the first-phase renewal plan of Enning Road had not been officially incorporated into the public participation mechanism, the strong public voice had already attracted high-level attention from the government, laying the foundation for subsequent public participation. In the collaborative participation stage, the meeting organization model became a vital way to safeguard public interests. The “Three Olds” (old villages, old factories, and old urban areas) renovation policy was effectively implemented under this model. Through two rounds of meeting voting, the full expression and protection of public interests were ensured. Meanwhile, the economic joint society in Pazhou Village played a pivotal intermediary role in practice. It not only organized villagers to express collective opinions, serving as a communication bridge between individuals and the government, but also broke through the shackles of the urban–rural dual system.

By replacing the traditional village committee with the economic joint society, it jointly promoted the sustainable development of the city. In the representative participation stage, the community renewal practice of Dongcheng Huayuan, an old residential community, combined top–down and bottom–up mobilization paths, forming a positive interaction between the residents’ self-governance groups and the government. Residents exchanged partial self-funded contributions for broader public interests, achieving a win-win situation in community renewal. Today, Guangzhou’s community renewal has taken new steps with the emergence of the proactive public participation model. Taking the renewal practice of Building 2, Jiqun Street, as an example, this model can be regarded as an innovation in Guangzhou’s community self-renewal. Residents efficiently completed the comprehensive renovation of the building through self-financing and self-construction, not only improving the living quality but also providing reference experiences for other communities. However, it is worth noting that the renovation area of Building 2, located on Jiqun Street, is relatively small and lacks overall coordination and planning with the surrounding areas. Meanwhile, Beiliyuan, an old residential community, demonstrated the organizational form of the cooperative participation model. Under the leadership of the neighborhood committee, residents quickly formed self-governance groups to promote the community’s renewal and renovation jointly. This case demonstrates that in large-scale community renewal, a clear leader is necessary to coordinate various matters and ensure the smooth progress of the renewal work.

This article highlights that by enhancing policy systems, capital raising, coordinator construction, and participation platform development, the public participation mechanism can be improved, leading to increased public participation efficiency. This facilitates meaningful discussions for exploring urban renewal in large cities and provides localized solutions for urban governance. Firstly, one must establish a flexible policy adjustment mechanism, including the approval system and the flexible land use regulation system. This mechanism flexibly and dynamically responds to the diverse demands of multiple stakeholders, including the government, the market, social organizations, and residents, ensuring that the supply of policy systems precisely matches the actual needs of community governance and maximizes governance efficiency. Secondly, one must implement a diversified financing guarantee mechanism and innovatively construct a cost-sharing model of “government guidance + market operation + resident co-bearing”. This not only allows the government to play a guiding role in resource allocation but also leverages the efficient operation of the market mechanism. At the same time, it encourages residents to participate in capital raising responsibly, thereby forming a win–win financing situation. Thirdly, one must strengthen coordinator construction and build a “localized + professionalized” support system. This means selecting and training coordinators who are familiar with the local community situation and possess professional knowledge. They can effectively communicate with all parties, promote consensus, and drive the smooth implementation of projects. Finally, in terms of public participation, platform construction, digital empowerment, and mechanism innovation, these areas should be strongly enhanced. One must utilize modern information technology means such as big data and cloud computing to create a transparent, efficient, and convenient digital participation platform. At the same time, one must explore new models that integrate online and offline activities, broaden public participation channels, enhance interactivity and participation, and ensure that public participation is not only diverse in form but also effective in substance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F. and W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.F.; visualization, D.F.; revising, D.F. and T.C.; supervision, T.C. and W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42471216, 42371206).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study have been included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the editors’ and anonymous reviewers’ comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A new style of urbanization in China: Transformation of urban rural communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D. Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1965, 31, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, W.; Fu, D.; Chen, T. Exploring Self-Organization in Community-Led Urban Regeneration: A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Approaches. Land 2025, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horelli, L.; Wallin, S. Civic Engagement in Urban Planning and Development. Land 2024, 13, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, L.; Lock, S.J.; Rydin, Y.; Lee, M. Participatory planning and major infrastructure: Experiences in REI NSIP regulation. Town Plan. Rev. 2019, 90, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Cabezas, V. Another mythology for local development? Selling places with packaging techniques: A view from the Spanish experience on city Strategic planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1995, 3, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.; Münster, S.; Noennig, J.R. A Theoretical Framework for the Evaluation of Massive Digital Participation Systems in Urban Planning. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2019, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jialing, Y.; Yan, H.; Shuying, T.; Wei, L. Jointly Creating Sustainable Rural Communities through Participatory Planning: A Case Study of Fengqing County, China. Land 2023, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.W.; Shen, G.Q.; Wang, H. A review of recent studies on sustainable urban renewal. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóbiás, K. Boros Participatory Planning and Gamification: Insights from Hungary. Land 2025, 14, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.; Chan, E.H.; Xu, Y. Assessing the social impact of revitalising historic buildings on urban renewal: The case of a local participatory mechanism. J. Des. Res. 2015, 13, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chenm, T.; Chanm, H.E. Understanding livable dense urban form for shaping the landscape of community facilities in Hong Kong using fine-scale measurements. Cities 2018, 84, 8434–8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsui, H.; Koistinen, M. The participatory research approach in non-Western countries: Practical experiences from Central Asia and Zambia. Disabil. Soc. 2008, 23, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberer, T. Evolvement of citizenship in urban China or authoritarian communitarianism? Neighborhood development, community participation, and autonomy. J. Contemp. China 2009, 18, 491–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Lang, H.; Hui, E.C.; Chen, T.; Wu, J.; Jahre, M. Measuring urban vibrancy of neighborhood performance using social media data in Oslo, Norway. Cities 2022, 131, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Yang, S.; Lai, Y. Experimentation-based policymaking for urban regeneration in Shenzhen, China. China Q. 2024, 258, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, L.; Demartini, P.; Marchegiani, L.; Marchiori, M.; Piber, M. Understanding orchestrated participatory cultural initiatives: Mapping the dynamics of governance and participation. Cities 2020, 96, 102459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.-M.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Ou, Y. Urban community regeneration and community vitality revitalization through participatory planning in China. Cities 2021, 110, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regional Plan Association. Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1929; pp. 1922–1930. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, L. The City in History; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Alinsky, S.D. Rules for Radicals; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, G.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, H.; An, X. Harmonizing stakeholder interests in urban renewal: A novel planning approach using explainable machine learning and spatial optimization. Land Use Policy 2025, 155, 107588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chang, J. Imitation, Reference, and Exploration—Development Path to Urban Renewal in China (1985–2017). J. Urban Hist. 2019, 46, 728–746. [Google Scholar]

- Permana, C.T.; Shaw, D.; Dembski, S. Towards a more collaborative planning process for traditional communities? A sociological-institutionalist analysis of the Kampong Kauman in Surakarta, Indonesia. Cities 2025, 158, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, R.; Gaffikin, F. Collaborative Planning in an Uncollaborative World. Plan. Theory 2007, 6, 282–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cao, K. The Third Sector in Collaborative Planning: Case Study of Tongdejie Community in Guangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2021, 109, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, M.; Gupta, J. The split ladder of participation: A diagnostic, strategic, and evaluation tool to assess when participation is necessary. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 50, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, E.G.; Sidney, M. Community development corporations as neighborhood advocates: A study of the political activism of nonprofit developers. Appl. Behav. Sci. Rev. 1995, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.E. Governance-driven democratization. Crit. Policy Stud. 2009, 3, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Kyttä, M. Incentives and Disincentives in Public Participation—A Review of Public Participation in Planning Practices in China. J. Plan. Lit. 2025, 40, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, E.C.M.; Lang, W. Collaborative Workshop and Community Participation: A New Approach to Urban Regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Chen, R.; Qin, S.; Liu, L. Evaluating the Public Participation Processes in Community Regeneration Using the EPST Model: A Case Study in Nanjing, China. Land 2022, 11, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Gkartzios, M.; Yan, J. Community Co-creation through Knowledge (Co)Production: The engagement of universities in promoting rural revitalization in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 112, 103455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.; Wong, J.T.; Wan, J.K. A review of the effectiveness of urban renewal in Hong Kong. Prop. Manag. 2008, 26, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).