1. Introduction

In this era of the global land rush, there has been an explosion of scholarship on ‘transnational land deals’ or ‘global land grabs’. These terms are generally defined as large-scale, cross-border land deals through lease, concession, or outright purchase by transnational corporations or foreign governments for diverse profit-seeking activities including food/non-food production, natural resource exploitation, and land speculation [

1,

2]. In the last decade, there has been a surge of literature on global land grabs, revealing the causes, drivers, and dynamics of the phenomenon unfolding at the local, regional, or global scales [

3,

4,

5]. Scholars have shed light on various spectrums of the effects of land grabbing on local configurations, especially concerning the transformation of land property relations [

6,

7], labor pattern changes [

8,

9,

10], social conflicts and local reactions [

11,

12], and human rights concerns [

13]. The impacts of land grabs on local livelihoods have also been debated [

1,

14]. Generally, these scholarly efforts have contributed evidence of the damage a land grab caused to the livelihoods of the affected local people, especially those who were either requested or forced to contribute the land they had owned, including a loss of access to farmland and resultant food insecurity, a decrease in productivity, displacement of their residence, and mounting indebtedness, among others [

6,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, some evidence on the positive impact of land grabs on livelihoods has also been presented, such as increased consumption and income levels, adoption of new agricultural practices, increased employment as wage workers, and improved local infrastructure [

3,

16,

21].

Although the burgeoning literature on land grabbing has greatly enriched our understanding of the possible effects of land grabbing on the livelihoods of affected local people, two important issues have been inadequately addressed. There is a lack of studies analyzing the impacts of land grabs in relation to wider social and agrarian change. The majority of academic land grab studies focus their analysis on the short-term effect of land grabs on local livelihoods. While their findings are insightful in numerous spectrums, they are often confined to micro-level contexts related to inter- and/or intra-household dynamisms or a local community and associated groups, with wider medium- to long-term social relations and alternations left unexamined. Indeed, the academic research has overlooked how land grabs mediate the emergence of new livelihood trajectories in multiple locales. This gap leaves some critical questions about livelihood outcomes unaddressed in the existing literature, such as why certain livelihoods are possible for some groups of people, but not for others; who would win and who would lose in the local developments of the post-land loss phase, and how the local agrarian transformations via land loss are linked to the wider processes of a long-term social change. Further, this void requires a close understanding of interlinkages between the micro-level contexts of local people’s livelihoods and state-driven processes of land grabbing, whereby previously non-existent, new collective livelihoods might come into being. It is also important to understand how a set of collective livelihoods that have emerged in different locales or according to varying identities present a social differentiation whereby newly formed social classes acquire relevance to the long-term processes of broader social and agrarian change (e.g., agricultural modernization, urban industrialization, penetration of capitalism, etc.).

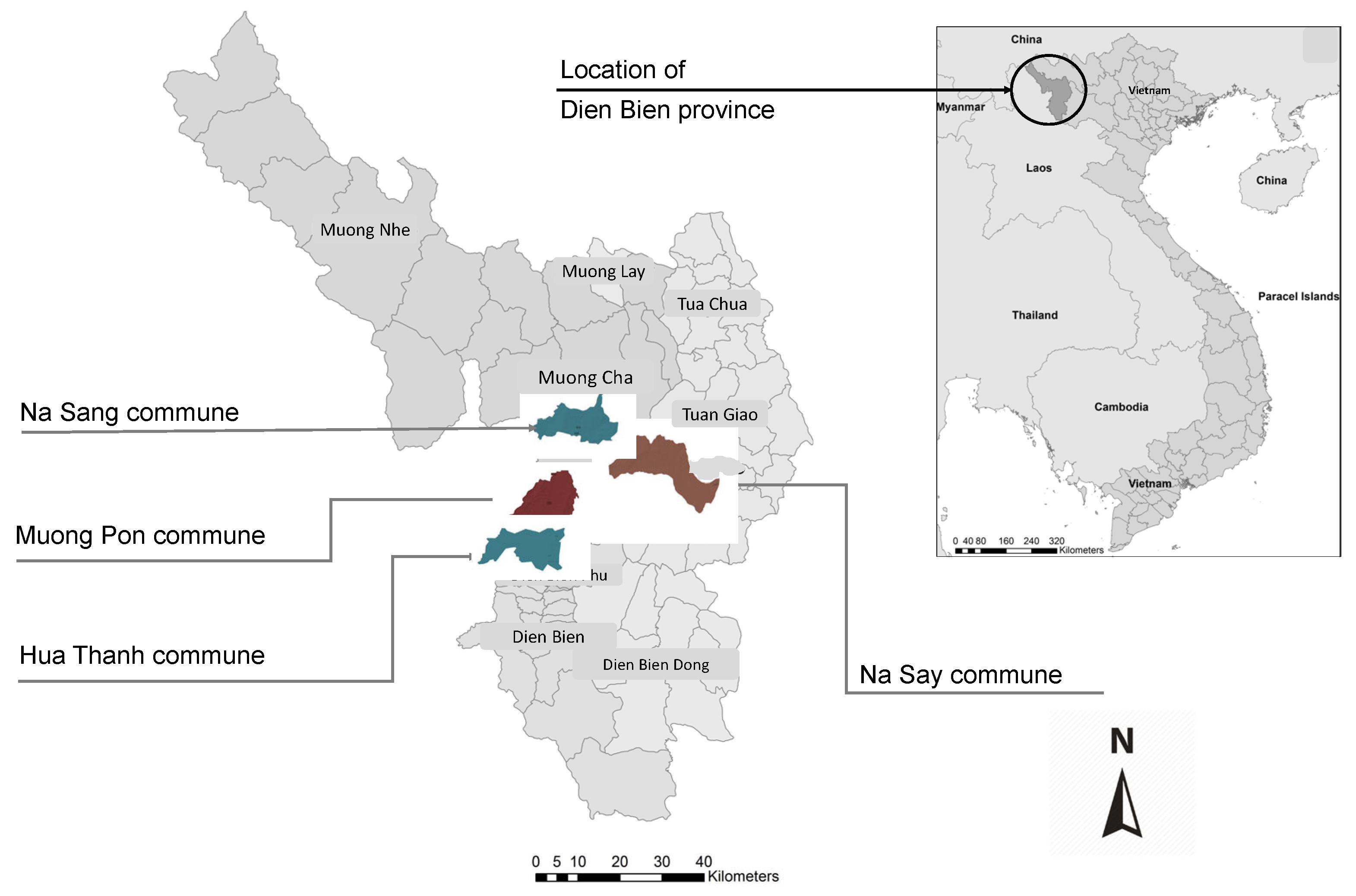

This paper seeks to fill those gaps in the light of a conceptual framework related to the agrarian political economy of livelihood developed by Scoones [

22] for understanding the differential impact of a land grab program on the communities and livelihoods of multiple ethnic groups. This study investigates how different ethnic minority groups, who had customarily owned the land, have developed diverse livelihood strategies following land loss, and how these strategies have shaped collective livelihood pathways. To meet the objectives, we draw on empirical evidence from our case study on rubber plantation land grabs in Dien Bien province, Northwest Vietnam.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section introduces the theoretical framework that underpins the study. This is followed with a discussion about the study site and research methods. After that, the findings are presented and discussed. The final section takes a step back and address how the paper’s findings speak to the broader land grab literature.

2. Theoretical Underpinning

Land grabbing has become the main concern for land use sustainability at any level from local to global. The drivers of land rush range from global dynamics such as increasing demand for, and prices of food and non-food agricultural commodities [

2,

23], corporate food regime restructuring [

24], energy system transition, and environmental purposes such as carbon sinks and global biodiversity [

1,

21,

25], to national and subnational forces including national development strategies [

26,

27], privatization of land by land titling programs or land reforms [

4,

28], and various political ends such as territorialization, sovereignty, and authority [

4,

29,

30]. A land grab process immediately impacts land users whose livelihoods depend largely upon the land and the associated natural resources that are acquired [

31]. There is consensus among scholars that a land acquisition could significantly transform the livelihoods of people residing in the target area by having their land use and control altered. The impacts of these processes, positive and negative, on local livelihoods have been intensely debated [

1,

16,

32]. The above findings contribute to offering diverse empirically grounded explanations of livelihood strategies and changes in specific contexts. However, they do not provide any accounts about the collective livelihood trajectories and associated social differentiation [

22,

33]. Indeed, common livelihood patterns that could be conceived of beyond individual/household contexts remain elusive. Thus, the critical questions of why certain livelihoods are possible for some social groups but not for others, as well as how new agrarian classes emerge, have not been addressed fully by those approaches.

To theorize the relationships between a micro-analysis of livelihoods and a macro-analysis of agrarian change, Scoones [

22] champions a combination of the insights from agrarian political economy and rural livelihood analysis. In developing a framework of the agrarian political economy of livelihood, Scoones [

22] draws on insights from ‘rural livelihood analysis’, which provides a useful framework to reveal the specifics of diverse agrarian livelihood contexts. In the framework, contexts, conditions, and trends constitute the broad spatial or temporal terrain which influences all aspects of people’s livelihoods historically, politically, economically, socially, or environmentally. The livelihood analysis emphasizes the presence of the ‘vulnerability’ context, in which exogenous or endogenous factors such as natural disasters, economic crises, or seasonality adversely affect livelihoods [

34]. This approach also concerns diversified economic and social activities that individuals and households pursue, livelihood assets (also known as capital) that they deploy for forging their livelihoods, and livelihood outcomes they achieve. Institutions and organizations are considered as key vehicles relating to the structures and processes that affect the household assets deployed, intervene in the household livelihood strategies pursued, and mediate the livelihood outcomes achieved, for different individuals and households [

22].

The livelihood perspective has been criticized by some critics, however, due to three reasons. First, it focuses on the micro-level politics of inter- and intra-household relations within the boundaries of a local community and its resident groups, without due consideration of wider political configurations and dynamics. Second, it rests on an instrumental mapping of livelihood assets as a basic component of rural poverty analysis, framed by an economic analysis. Third, a livelihood analysis has a very limited focus on political space by focusing mainly on ‘empowering’ the poor, without making it clear how this process takes place. The class relations are also absent from the discourse on livelihood analysis [

35].

The agrarian political economy provides the opportunity to ‘bring the politics back in’ to livelihood analysis to show political and economic alliances being forged between different classes and the structuring of wider agrarian change dynamics [

22]. Scoones notes that “a grounded political economy approach allows for the detailed description of a diversity of livelihood strategies and evaluation of long-term livelihood trajectories and their structural conditioning and shaping” [

22]. By adding two more questions from Bernstein’s initial four questions of political economy underpinning agrarian analysis [

36], Scoones presents six core questions in analyzing the agrarian political economy of livelihood: (i) ‘who owns what (or who has access to what)?’; (ii) ‘who does what?’; (iii) ‘who gets what?’; (iv) ‘what do they do with it?’; (v) ‘how do social classes and groups in society and within the state interact with each other?’; and (vi) ‘how do changes in politics get shaped by dynamic ecologies and vice versa?’ [

22] They are a set of questions on livelihood that have been answered primarily on the micro-scale through a detailed livelihood analysis addressing the ownership of household livelihood assets, livelihood strategies, and their consequences. However, a profound understanding of collective livelihoods allows us to reveal the contextual and experiential specificities of accumulation and differentiation in specific locales or according to particular identities of social groups. An agrarian political economy perspective, on the other hand, helps elucidate how social relations on diverse scales shape a broad network of accumulation, determine patterns of class formation, and ultimately identify patterns of winners and losers under a changing agrarian landscape. By incorporating the strengths of livelihood analysis and agrarian political economy, we can better identify the nuances and intersections of livelihoods associated with particular locales or identities and also understand their implications for a broad social and agrarian change, in such a way that neither approach can do by itself.

There is a theoretical challenge when it comes to combining these two approaches. A conventional livelihood analysis attempts to unfold individualistic strategic behaviors. The agrarian political economy primarily focuses on analyzing social differentiation, including power relations and institutional processes at meso or macro levels. At a glance, the level of analysis in each analytical frame appears to diverge. To link complex, individualized livelihoods to the dynamics of accumulation and social differentiation, some scholars argue that a ‘livelihood pathway’ approach is useful to provide a way forward [

37,

38,

39,

40]. According to de Haan and Zoomers [

40], a livelihood pathway is defined as “a pattern of livelihood activities which emerges from a co-ordination process among actors, arising from individual strategic behavior embedded both in a historical repertoire and in social differentiation, including power relations and institutional processes, both of which play a role in subsequent decision-making” [

40].

Three vital issues are associated with the ‘livelihood pathway’, a concept that forges synergetic links between livelihood analysis and agrarian political economy. First, a livelihood pathway highlights the formation and development of a collective pattern of livelihoods relating to a locale, a community, or any other identity. Accordingly, its plurality (livelihood pathways) signifies a differentiation of livelihood patterns across different locales, communities, or other identities. The genealogy of such a collectivized understanding of livelihoods could be connected to the emphasis of a political economy perspective: a certain common attribute that is shared by a group of people beyond individual differences (e.g., land ownership, income level, gender, age, ethnicity, and so on) provides a context for them to collectively engage with the livelihood of a similar trait.

Second, a livelihood pathway analysis highlights the collective dimensions of interaction between agency and ‘institutional processes/organizational structures’. Accordingly, it allows us to unpack the ‘black box’ of institutions and organizations regarding how they affect and transform the livelihoods of people at a certain collective level. This point could be better conceived of by considering multiple layers of commonality and difference observed for a people. For example, a group of rural dwellers might be seen as subsistence peasants living in the same region. However, the very same people could also be considered as an amalgam of sub-groups living in different communities with varying socio-cultural backgrounds and political networks. From the viewpoint of the original commonality of livelihood (subsistence farming), it would be difficult to understand how and why any difference in the livelihood emerges across the group of people after external institutions and organizations influence them (e.g., land loss through grabbing). It is possible, however, that certain collective variations at the sub-group level (e.g., ethnicity, educational level, political affiliations, etc.), which appear rather irrelevant at first sight, have played decisive roles in the formation and development of a distinctive set of livelihood pathways.

Third, as de Haan and Zoomers [

40] argue, by incorporating political economy perspectives, a livelihood pathway analysis allows us to relate the identified collective patterns of livelihoods to the wider context of a society. As discussed above, a group of rural dwellers may share or shape a common trajectory of livelihood. In doing so, they develop a particular ‘habitus’, which, according to Bourdieu [

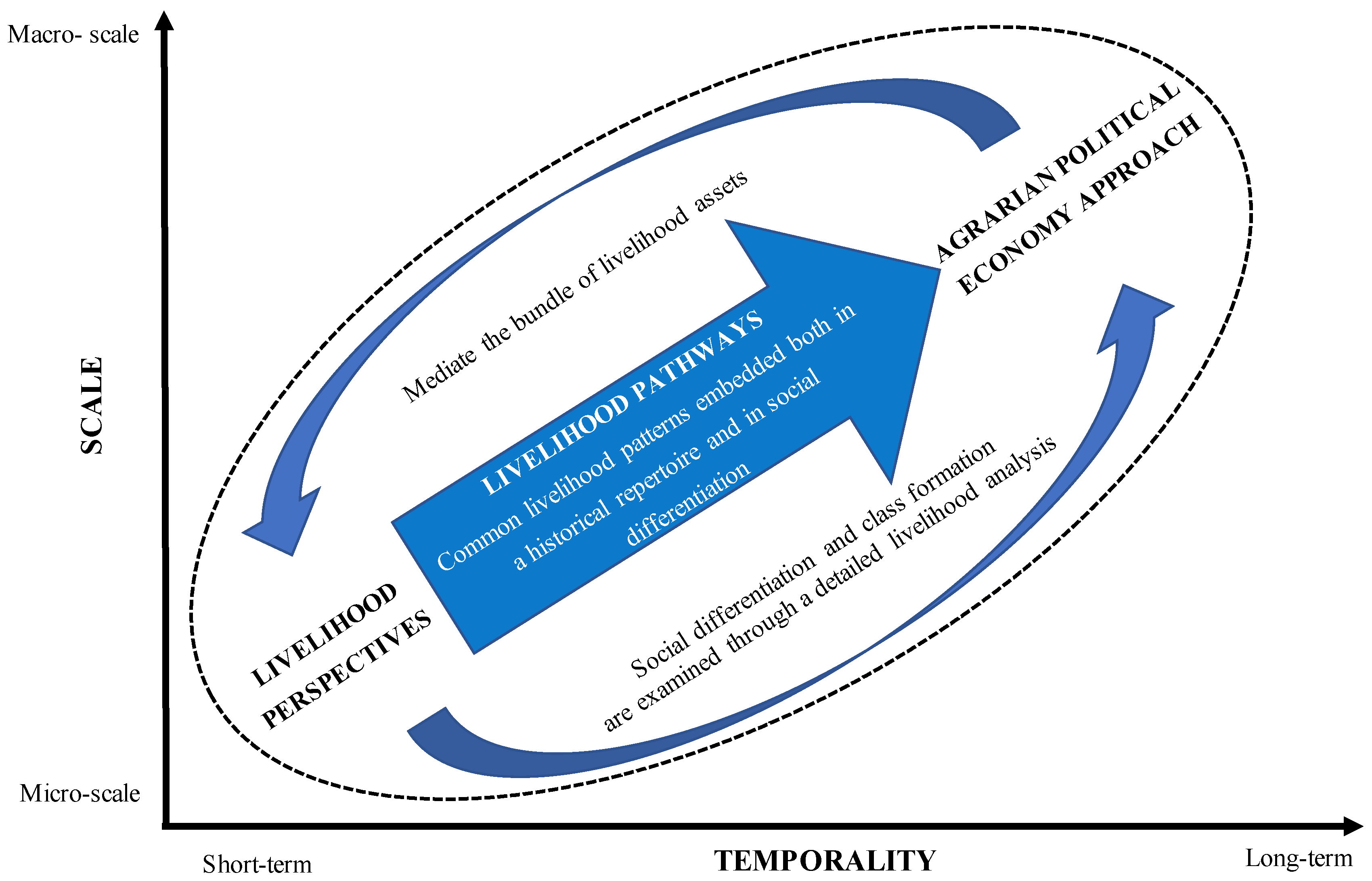

41], is a system of dispositions primarily defined by social class and to be acquired through socialization. An agrarian political economy perspective helps link this domain of social differentiation and class formation to the macro-scale structure and processes, so that a livelihood pathway as the middle level concept could be relevant to the wider social and agrarian change (e.g., agricultural modernization, urban industrialization, and penetration of capitalism). Thus, there is a need to examine the transition from micro-scale (livelihood perspectives) to macro-scale (agrarian political economy approach). In addition, inspired by the temporal perspective of political economy, a livelihood pathway analysis adds historical moments (short- to long-term) to a livelihood analysis. These spatial and temporal moments of a livelihood pathway provide a useful bridge to the structural concerns of an agrarian political economy. Such an integrated approach is recursive in that it connects inter- and intra-household relations with the structural process of social differentiation within which their livelihoods are pursued, as shown in

Figure 1.

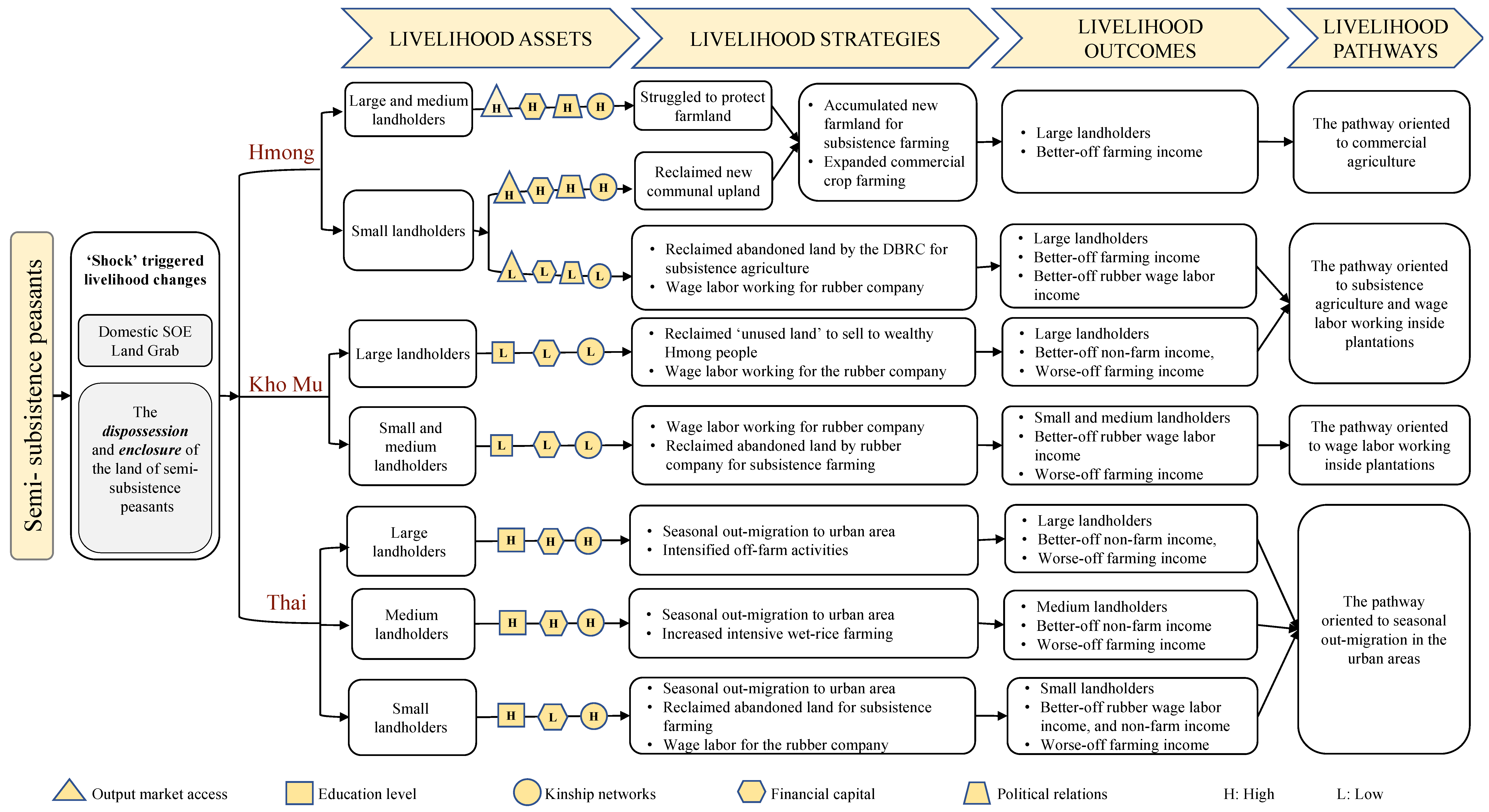

By incorporating these conceptual leverages, an extended livelihood framework is built as an integrated model involving the elements of land grabs and agrarian political economy, as shown in

Figure 2. In the integrated framework, land grabbing is considered as a critical factor for agrarian changes that affect individual household livelihoods. In the light of the framework, the processes of land acquisition appear to have changed the ability of households to access a bundle of livelihood assets (especially land and land-based resources). The transformation of land use reshapes the opportunities and constraints relating to the livelihood strategies pursued, as well as the outcomes achieved, of individual households.

In addition, land grabs are a critical driver pushing affected people into vulnerable conditions such as displacement, distress from land use transformations, food insecurity, erosion of customary culture, and social conflicts, among others. In response to land grabbing, individual households, depending on various given contexts, pursue different livelihood strategies with the combination of livelihood assets at their disposal to achieve the desired livelihood outcomes.

The peasants who have lost their land could have various options according to their given circumstances and priorities in needs. They would strive, covertly or overtly, to protect their land or get access to another land for sustaining the farming practices on which they have relied. Those who have lost their farmland but do not have the power to regain it nor have access to any other available livelihood sources may be left with no choice but to become wage workers for the investors. Meanwhile, others who have some good physical and financial capital at hand might prefer earning more income by offering new services to others. Others might also end up moving away from their neighborhood to a distant city to earn and send remittances home.

While individual household responses to land loss may vary, certain common patterns of livelihood strategies and outcomes may be observed at a micro- or meso-social level, which can be discerned as a set of livelihood pathways. As mentioned above, livelihood pathways would be a useful conceptual liaison to identify patterns of collective accumulation and social differentiation occasioned by land grabs over time.

As seen in the agrarian political economy of livelihood approach, five out of the six basic questions of agrarian study, as offered by Bernstein [

36] and Scoones [

22], have been ingrained to link the livelihood framework to the wider patterns of agrarian change. For the purpose of our inquiry, the question of “who owns what?” (or “who has access to what?”) relates to the issues of property and ownership of land and other livelihood assets that have been changed following a land grab. The questions of “who does what?” and “what do they do with it?” relate to the concerns of individual livelihood strategies for the short term, while from a medium- and long-term macro-scale viewpoint, they pertain to the social division of labor, patterns of consumption, savings/indebtedness, and investments taking place in the post-land grab phase. The question of “who gets what?” directly refers to short-term individual livelihood outcomes, but it also relates to the medium- and long-term patterns of macro-scale accumulation and socio-economic differentiation. The final question of “how do social classes and groups in society and within the state interact with each other?” offers a useful lens to examine the social relations among key stakeholders and other actors involved in the land grabs.

By adapting the foregoing framework, this paper attempts to respond to the above core questions for an in-depth understanding of agrarian change dynamics in the post-land grab phase in Vietnam. We aim to examine how livelihood pathways have been formed after the rubber plantation grabbing by a state-owned enterprise in the mountainous area.

5. Discussion

Considering the findings above, this study solicits a renewed understanding of the consequences of land grabs for livelihoods in the light of the agrarian political economy of livelihood framework. The key discussions are outlined below.

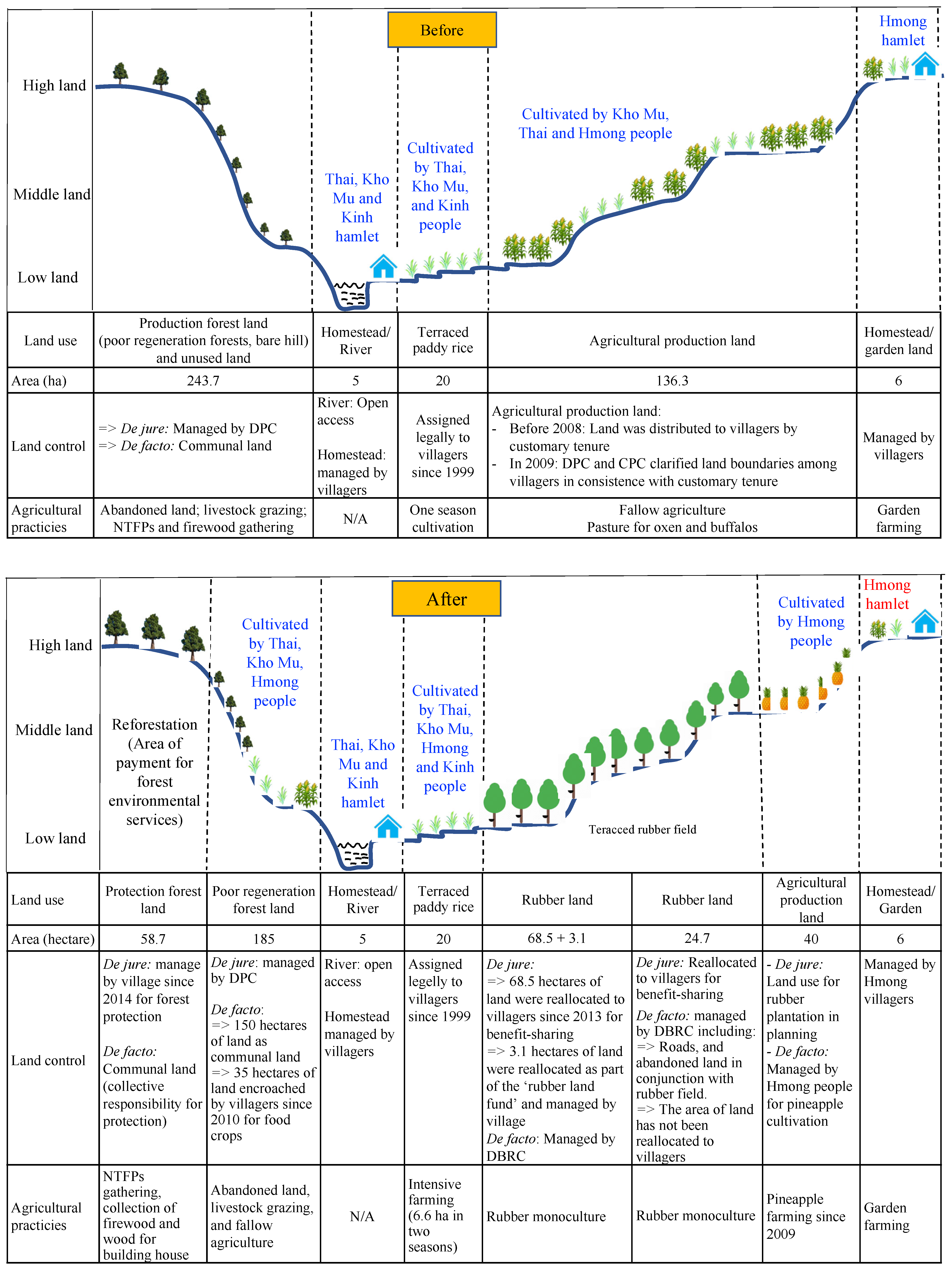

First, right after their land loss on behalf of contribution for rubber plantations, the local peasants diversified their formerly subsistence-based livelihoods into various forms such as cash crop cultivation, acquisition of new land, rubber wage labor, and out-migrated urban labor. As observed in the study villages, the choice of livelihood strategies was made consciously based on the livelihood assets that each ethnic group used to deploy, and the socio-political relations as well as market conditions they were involved with. As we have seen, the total remaining farmland in the aftermath of the land contribution to the rubber company played an essential role in determining households’ livelihood choice, such as on-farm strategies, off-farm activities, or both in combination. Small landholders contributed almost all their land to the rubber company, with many of them being unable to acquire new land. Hence, they had no choice but to find wage labor work wherever available. Here, their relationships with their relatives, educational background, and social networks were the key factors that determined what type of wage labor work they could engage in. Thai people, who tended to have relatively high educational levels, available social networks, and reliable relationships with their relatives, were able to get more lucrative wage work in the city. Meanwhile, Kho Mu people, who tended to lack those conditions, were engaged in the relatively less lucrative wage work for the rubber company. In contrast, medium- and large-sized landholders of all the three ethnic groups were able to maintain existing farming practices while being engaged in wage work for the rubber company, or urban industrial wage work. On the other hand, political connections with local officials allowed Hmong people to retain large areas of farmland, on which they increasingly pursued commercial farming by taking advantage of the availability of output market access.

Geographical location has a profound influence on households’ livelihood choice. To minimize operational costs, the Dien Bien Rubber Company prioritized the establishment of rubber plantations in villages characterized by favorable biophysical and infrastructural conditions. In villages such as Tin Toc, Huoi Chan 1, Xa Nhu, Co Ha, and Ta Lao—where road access is relatively convenient and the terrain is less steep—much of the cultivable land previously managed by local households was converted into large-scale rubber plantations. In these villages, the residents were left with little agency over their livelihood choices, as the large-scale conversion of farmland to rubber plantations severely constrained their access to productive land. Consequently, many households were compelled to shift their livelihood strategies toward wage labor employment with the rubber company or to engage in seasonal out-migration for off-farm income opportunities. In contrast, Na Sang village is situated in a more remote and mountainous area, with limited transport infrastructure and reduced connectivity to markets. These spatial constraints, alongside the Hmong community’s strategic engagement with local political structures, enabled households not only to retain their agricultural land but also to expand their holdings. As a result, many pursued a distinct livelihood pathway centered on commercial farming, diverging from the agrarian transformations observed in the other study sites.

All these findings clearly suggest that though sharing the identical operational source of land acquisition, the affected local people with different social-economic backgrounds under varying political, cultural, and spatial contexts had significantly different responses to their land loss. Hence, it is argued that in analyzing the impacts of land grabs, communities could be seen as heterogeneous units, and that our analysis should not confine itself to short-term, immediate economic impacts and responses, but embrace the reformulated long-term patterns of social differentiation and class formation in wider contexts.

Second, in the land grab literature, there is a common argument that in the post-land grab phase, larger landholders have the potential to achieve higher incomes and assets than smaller landholders by taking advantage of their asset status to accumulate further land from desperate small farmers through an “everyday process of accumulation and dispossession” [

9]. Access to land plays a key role in creating winners (large landholders) and losers (smallholders), with the losers being forced to sell their remaining land, seek wage employment locally, or migrate seasonally or permanently. This ‘everyday process’ gives rise to a differentiation among farm households in terms of their access to land, which consequentially leads to the formation of contrasting livelihood pathways. However, the development of the pathway toward forming large landholders in our case does not fit in this process. In the post-land grab stage, Hmong people retained a large area of land by transforming their farming system from slash-and-burn to intensive cash crop cultivation. As they continued commercial farming, they accumulated financial capital, and using it, they bought more land over time. However, the large landholders did not buy land from small landholders because the latter tended to retain their small plots of land for food subsistence rather than sell them to the former. Hence, to acquire new land, large landholders negotiated with other large landholders who needed more money for technical investment in intensive farming or children’s education.

Third, the rubber plantation land grabs taking place in Dien Bien point to the conscious efforts of the socialist state to involve ethnic minority populations in the ongoing process of “market integration, replacing the common property with private land use rights, pressing shifting cultivators to become settled farmers” [

48]. Like numerous state policies introduced in the ethnic minority uplands, the rubber plantation project shows that the state aims to “handle highland minorities in the most effective and economic way” to avoid impeding Vietnam’s steady ‘modernization’ [

49]. Ultimately, by employing these projects, the State’s goals are to “ensure that [ethnic minorities’] economic activity was legible, taxable, assessable, and confiscatable or, failing that, to replace it with forms of production” [

50].

Fourth, these findings also have broader implications when viewed through the lens of ethnic inequality and agrarian justice. The differentiated livelihood trajectories among the Thai, Kho Mu, and Hmong communities are not simply the result of individual household choices or market dynamics but rather reflect deeper structural inequalities embedded in Vietnam’s upland development policies and land governance regimes. The rubber plantation expansion, though officially promoted as a modernization and poverty reduction initiative, has in practice privileged groups with greater access to land, education, political connections, and market resources—reinforcing existing hierarchies and creating new forms of exclusion [

51,

52]. For instance, the Hmong’s ability to retain and commercialize large landholdings was closely tied to their connections with local officials, while the Kho Mu, with fewer institutional ties and weaker educational backgrounds, were more often pushed into precarious forms of labor. This suggests that the state-led process of “legibility” and “market integration” has not affected ethnic groups equally; instead, it has reproduced patterns of marginalization under the guise of development [

7,

47,

53,

54]. By reshaping land access, labor relations, and market participation, these land grabs have contributed to a new agrarian order in which inequality is restructured along both class and ethnic lines. As such, our findings call for a more critical engagement with the justice dimensions of land-based development projects in multi-ethnic contexts, where the long-term social consequences may outweigh short-term economic gains [

53,

55].

Last, this study advances the agrarian political economy of livelihood framework originally articulated by Scoones [

22] by proposing an integrated conceptual approach that incorporates the land grab phenomenon as a key analytical entry point. While Scoones emphasized the need to connect micro-level livelihood strategies with broader political-economic structures, our framework operationalizes this connection by tracing how land dispossession reshapes household livelihoods in the short term and contributes to longer-term processes of social differentiation. Specifically, we show how land grabs—implemented through state-corporate alliances—initiate immediate disruptions to local livelihoods, which in turn catalyze divergent livelihood pathways based on households’ differential access to assets, socio-political capital, and ethnic identity. Over time, these differentiated responses evolve into broader patterns of agrarian restructuring at the community and regional levels. Thus, the proposed framework enables a dual-level analysis: capturing both the short-term micro-level consequences of land loss and the long-term macro-level outcomes in terms of emergent agrarian transitions. In doing so, this study offers an important theoretical extension to Scoones’ framework by deepening its capacity to account for the temporal dynamics of land-based transformations and the intersectionality of ethnicity, class, and state power in shaping rural livelihoods.

6. Conclusions

In the last decades, there has been a proliferation of case studies in the land grab literature that are focused on the impacts of land grabbing on the livelihoods of households and individuals within a community. In this regard, local people in the affected community are treated as if they were a homogeneous unit, with the community members uniformly affected by the land loss. However, the impacts may not necessarily be uniform but could be significantly different among the different groups within a community, let alone across different neighboring communities. In addition, there is a lack of studies analyzing the impacts of land grabs by integrating livelihood perspectives with wider contexts of agrarian political economy. This paper has attempted to fill these gaps by highlighting the consequences of rubber plantation land grabs on the livelihoods and social stratification of ethnic minority peasants in Northwest Vietnam.

Drawing on the integrated framework of the agrarian political economy of livelihood, this paper has highlighted the consequences of land grabs by revealing distinctive patterns of livelihood pathways within a complex web of intersections across class and ethnicity in an upland area. An emphasis on the livelihood aspect of the integrated framework has allowed us to illuminate the emergence of a set of distinctive livelihood pathways. Following the land grabs, individual households, with different socioeconomic, political, ethnic, and spatial backgrounds, have drawn on a bundle of livelihood assets at their disposal. In doing so, they have pursued various livelihood strategies that might be most congenial to their needs, thereby achieving various livelihood outcomes. Accordingly, as time goes on, common livelihood patterns have emerged at the local community level, influenced to a significant degree by the given local context after land contribution. This paper has highlighted that the activities of these groups were identified, chosen, and carried out as part of their conscious livelihood strategies based on the livelihood assets at their disposal, including the socio-political relations and market conditions they were involved with.

This study further argues that, as a conceptual approach, the agrarian political economy of livelihood is a framework that has an inexhaustible potential for analyzing the impact of land grabs on livelihoods thanks to its integrative feature to link short-term micro-scale and long-term macro-scale contexts. Although our research findings drew on a limited number of villages in Northwest Vietnam, there are several areas and communities across the country that accommodate similar local contexts of land property relations, livelihood conditions, and surrounding geographical, socio-political, and cultural contingencies. For instance, in many upland communities, local people have maintained customary land rights over generations. Their livelihoods mainly rely on subsistence farming, which heavily depends on the land and land-based resources. Hence, enclosure of communal land and associated land dispossession from the original land users could be operated relatively easily because of the existing ambiguous land tenure system and the land users’ limited bargaining power to maintain the land [

47,

56]. Consequently, similar patterns of livelihood pathways, as we observed in our research, could be seen widely in Vietnam. Unpacking these patterns, as Scoones noted, could itself be an act of ‘bringing politics back in’, which was originally central to livelihood analysis, whose essential domain has often been downplayed and even lost through various externally driven aid deliveries in the past three decades.

The findings of this study highlight significant differences in the impacts of rubber plantation expansion in the Northwest region of Vietnam, largely influenced by local governance capacity, land tenure systems, and ethnic minority livelihood strategies. To address these disparities, several policy recommendations are proposed. First, strengthening community-based land governance is critical, especially in areas where ethnic minorities face challenges securing land rights. Implementing participatory land-use planning and formalizing customary land rights would help ensure tenure security and reduce the risk of land dispossession. Second, local authorities should design region-specific livelihood support programs, tailored to the unique socio-economic conditions of ethnic minority communities, particularly those affected by land conversion for rubber plantations. A uniform approach to livelihood assistance is insufficient, as it fails to account for the diverse needs and vulnerabilities of different groups. Third, there is a need to enhance transparency and accountability in rubber plantation investments by establishing robust monitoring mechanisms. Affected communities must be adequately informed and consulted throughout the process, and environmental and social impact assessments should be conducted transparently. This would allow for adaptive policy interventions and ensure that the development of rubber plantations is sustainable and beneficial to all stakeholders in the long run.

This study acknowledges several limitations. The research is confined to a small number of villages in Northwest Vietnam, which limits the broader applicability of the findings. While the analysis offers deep qualitative insights supported by descriptive statistics, it does not include cross-regional quantitative comparisons. To enhance understanding, future research should adopt a comparative, multi-site approach across different ethnic groups and regions. Longitudinal studies are also recommended to trace how livelihood pathways and social differentiation evolve over time. Despite these limitations, this study proposes that its findings on social differentiation and livelihood pathways may be relevant to other regions with similar characteristics, such as customary land rights, subsistence farming, and limited political influence. The core intention of this study is not to generalize its findings universally, but to offer a conceptual framework that can be applied to investigate comparable land-related transformations in other contexts.