Abstract

Against the backdrop of the current rural economic transformation and the intensification of the ageing process, land transfer, as an important land policy tool, has gradually become a key factor influencing the consumption behaviour of farmers, especially older farmers. Based on the four-period panel data of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), this study uses a two-way fixed-effects model to examine the impact of land transfer (land transfer-out, land transfer-in, and two-way land transfer) on the consumption behaviour of older farmers. This study finds that land transfer-out significantly increases the total consumption of older farmers and promotes subsistence, healthy, and hedonic consumption. In contrast, land transfer-in does not show a significant effect on hedonic consumption. The mechanism test reveals that household income plays a key mediating role in the process of land transfer, affecting the consumption behaviour of older farmers. Two-way land transfer promotes the consumption level and the upgrading of the consumption structure of older farmers through income portfolio optimisation and risk diversification.

1. Introduction

With the accelerated ageing of the rural population, older farmers have gradually become the main group in the rural consumption market, and the improvement of their consumption ability is a strategic fulcrum to cope with the challenges of an ageing society and activate the potential of rural domestic demand [1]. Despite the Chinese government’s continuous intervention through policy tools such as infrastructure investment [2] and social security system improvement [3], the consumption level of older farmers is still relatively low [4], the deep systemic root of which lies in the dilemma of the dual attributes of land factors. As a productive asset, land provides basic survival security for older farmers. However, due to land fragmentation and a decentralised business model, its inefficient factor allocation leads to a long-term diminishing returns to scale in the production function [5,6], thus forming a vicious circle of low productivity lock-in effect and consumption inhibition. It has been shown that less than 30 per cent of land is transferred to older farmers [7], a phenomenon that reflects the inefficiency of the existing allocation of land resources to older farmers. The promulgation of the Rural Land Contracting Law provides legal protection for the transfer of land by older farmers. The land transfer system has become an important means to solve the above dilemma by restructuring the property rights transaction structure and optimising the efficiency of factor allocation. At the same time, the transfer of land by older farmers can reduce their production risks and economic burdens, and enhance their income stability, thus releasing the consumption potential of older farmers. Under the combination of land transfer system implementation and government support, China’s land transfer area increased from 12,445,333.33 hectares in 2010 to 38,418,666.67 hectares in 2022 [8].

The impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of farm households has become a topic of wide academic interest. The established literature generally confirms that land transfer has a significant uplifting effect on farm household consumption [9], and its impact effect can be attributed to the fact that land transfer significantly reduces the vulnerability of the traditional smallholder economy through diversification of income sources [10,11]; contractualised transfer mode significantly reduces income volatility caused by agricultural business risks [12]; and incremental income from land transfer exhibits a significant propensity for non-farm consumption [13]. However, there are obvious limitations in the existing research: first, the research perspective mainly focuses on the impact of land transfer on farmers’ consumption, and lacks a systematic examination of the subjective position of older farmers and their unique life cycle constraints; second, the dimensions of the analysis mostly adopt the binary division of “transfer-in & transfer-out”, ignoring the contract reconstruction effect formed by the bidirectional land transfer. The land transfer-out (where older farmers cede the management rights of their contracted land to other business entities, such as agribusinesses, co-operatives or other farmers, through leasing, subcontracting, etc.) and transfer-in (where older farmers acquire the management rights of other people’s land through leasing, substitute farming, etc.) of older farmers are significantly different from those of other age groups. In terms of land transfer-out, older farmers tend to obtain stable rental income through long-term transfer contracts, forming a ‘land pension’ to make up for the shortcomings of the rural pension system [14], which is very different from the middle-aged and young groups who use the transfer proceeds for entrepreneurship or investment in human capital; older farmers retain the contractual right and transfer the right of management, and maintain their ownership of the land while obtaining economic returns. Pursuing economic gains while maintaining symbolic control over the land is a way to consolidate the intergenerational family contract. In terms of land transfer-in, despite physical limitations, older farmers capitalise on their agricultural experience to carry out small-scale intensive cultivation, compensating for efficiency disadvantages through ‘super-marginal output’, an ‘experience-intensive’ model that is different from the ‘capital instead of labour’ model of the young and middle-aged, which relies on mechanisation. The ‘experience-intensive’ model is different from the ‘capital-substituting-labour’ path of young and middle-aged people who rely on mechanisation. At the same time, the transfer-in of land becomes an important way for older farmers to maintain their social network and identity, and when the economic support of their offspring is unstable, the land management serves as a ‘safety valve for consumption’ [15]. In addition, the two-way land transfer unique to older farmers breaks through the traditional binary division, and is essentially a resource optimisation strategy under intergenerational collaboration: through the transfer-out of poor-quality plots to obtain rents, and the transfer-in of high-quality arable land into the neighbourhood to achieve intensive management [16,17], not only to reduce the risk of social isolation in the event of complete withdrawal from agriculture, but also through the formation of a new type of production community through the intergenerational support network of the family, which is ‘old age management + youth security’. The new production community of ‘old age management + youth security’ is formed through the intergenerational support network of the family, and its consumption behaviour thus shows stronger characteristics of intergenerational transfer and preventive savings. Therefore, this study tries to break through the limitations of the existing research and analyse the impact of land transfer on consumption from the perspective of older farmers, and explore the differential impacts of land outflow, land inflow, and two-way land transfer, respectively.

Currently, an increasing number of studies are investigating the consumption behaviour of older farmers. From the perspective of consumer economics theory, the consumption behaviour of older farmers combines a risk-smoothing mechanism, a social capital accumulation effect, and an intergenerational transfer payment function [18]. Their consumption behaviour is affected by several factors, including individual characteristics at the micro level, resource endowment of the household at the meso level, and constraints of the institutional environment at the macro level. At the level of individual characteristics, the age factor influences consumption decisions by moderating the income sources and expenditure needs of older farmers [19], while health capital stock constitutes the core of the rigidity of healthcare expenditure and the constraints on consumption capacity [20]. The consumption preferences of older farmers are generally oriented towards survival rationality, with the marginal utility of necessities significantly higher than that of hedonic goods in their consumption function [21]. At the household endowment level, labour force structural change creates a double constraint through the decline in agricultural labour productivity and the contraction of household income streams [22,23], forcing older farmers to rely more on fixed income and social security to maintain a basic livelihood. Their asset accumulation status determines the amount of savings and capital that can be accessed by older farmers, which directly affects the sustainability of consumption [24]. Intergenerational support, as an informal guarantee mechanism, alleviates the budget constraints of old-age consumption through income transfers [25], but is regulated by both the economic conditions of children and the intensity of filial piety culture. At the level of internet use, the penetration effect of digital technology reconfigures the consumption behaviour of older farmers through the reduction in information acquisition cost and the improvement of transaction efficiency [26,27]. At the level of the socio-economic environment, regional economic gradient differences shape consumption space through the degree of diversification of income sources and the level of market development [7]. The marketisation process in rural areas enhances the diversity of consumption and also creates a risk-expectation effect through the increased sensitivity to price fluctuations [28,29]. Institutional factors regulate consumption behaviour through a combination of policy instruments, with pension coverage and benefit levels affecting the acquisition of economic autonomy [30,31], the healthcare system safeguarding basic consumption needs by reducing the probability of catastrophic health expenditures [32,33], and precise poverty alleviation policies supplementing the capital of livelihoods through a livelihoods mechanism to mitigate the lock-in effect of the poverty trap on consumption upgrading [34], creating a synergy between policy interventions and market mechanisms.

Although existing studies have analysed the factors influencing the consumption behaviour of older farmers from various perspectives, the theoretical explanation of the central role of land elements is still insufficient. As a special resource with both productive assets and social security functions, the allocation efficiency of land property rights profoundly shapes the consumption behaviours of older farmers through the income effect and risk buffer mechanism [35]. The transferability of land contract management rights not only reconfigures their economic autonomy [36] but also triggers structural changes in the consumption function through factor reallocation. Land transfer-out enhances consumption budget constraint slackness through asset-based returns, while land transfer-in strengthens the consumption support capacity of agricultural operations based on economies of scale, and the two form a differentiated consumption-driven path. In particular, the two-way land transfer generates synergistic effects through the optimisation of property rights portfolio to enhance the elasticity of consumption upgrading of older farmers, providing new evidence for the applicability of the theory of property rights economics in the ageing scenario.

Based on the above, the contribution of this study is reflected in three dimensions: firstly, it constructs a multidimensional analysis framework of ‘transfer mode-income structure-behavioural response’, which breaks through the traditional uni-dimensional analysis paradigm, and provides a new perspective for analysing the consumption effect of land transfer. Secondly, it adopts a two-way fixed effect model (time fixed effects, T FE; province fixed effects, P FE) to reveal the impact of heterogeneity of land transfer on consumption behaviour of older farmers and its mechanism of action, and further analyses the interaction effect between the two land transfer modes. Finally, the influence of spatial and temporal dimensions on the consumption behaviour of older farmers is fully considered. In the spatial dimension, based on the four-period panel data of the China Family Panel Studies, a sample of older groups covering a wide range of geographic areas is selected, which provides a guarantee of the universality and representativeness of the research results. In the temporal dimension, using the panel data spanning seven years, the land transfer and consumption behaviours of older farmers in 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022 are covered, which can reveal, in a relatively comprehensive way, the process of dynamic changes in their land transfer and consumption behaviour.

This study aims to reveal the impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, with a focus on resolving the intrinsic correlation between the heterogeneity of land transfer models (transfer-out, transfer-in, and two-way transfer) under life cycle constraints and the upgrading of consumption structure. Research findings: Land transfer-out significantly boosts the consumption of older farmers through “conversion of guaranteed income”. The transfer-in of land relies on the “experience rent premium” to achieve the function of smoothing consumption. The two-way transfer of land, through the dual mechanisms of risk dispersion and intergenerational collaboration, improves the consumption structure while reducing the motivation for precautionary savings. This research not only expands the intergenerational perspective of the study on the economic effects of land transfer, but also provides a theoretical basis for the coordinated reform of the rural elderly care security system and the land market.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Land Transfer-Out and Land Transfer-In and Consumption Behaviour of Older Farmers

Older groups usually face the dual constraints of decreasing income and increasing demand for old-age security in the late life cycle [37]. Based on the life cycle hypothesis theory, the consumption behaviour of older farmers essentially reflects their inter-period allocation of resource stocks throughout their life cycle [38], and land transfer, as an important means of asset reset for older farmers, profoundly affects their consumption behaviour by reconfiguring the mix of production factors.

In the land transfer-out scenario, the alienation of land contract management rights is essentially a transformation of agricultural assets into financial assets [39,40]. The fixed rental income generated by the property rights transaction has stable cash flow characteristics, effectively alleviating the liquidity constraints and income fluctuation risks faced by older farmers. That is, land transfer-out increases the disposable income of older farmers, reduces precautionary saving incentives [41], improves the structure of household balance sheets, and enhances risk tolerance [11]. In addition, land transfer-out can also promote non-farm employment of older farmers and expand immediate consumption capacity through wage income [42,43].

In a land transfer-in scenario, the expansion of the scale of operations is essentially a Pareto-improvement process of the factors of production. According to the neoclassical investment model, the increasing marginal payoff effect of the land factor triggers a consumption response at two levels. First, economies of scale in agricultural output can increase operating income, raising the consumption baseline through the mechanism of the persistent income hypothesis [44]; second, the technological substitution effect brought by mechanised inputs reduces labour intensity, prompting older farmers to achieve a Pareto improvement in the allocation of time for consumption in the form of ‘leisure-labour’ [45,46]. It is worth noting that the impact of land transfer-in on the consumption structure of older farmers may be characterised by heterogeneity: the rigid growth of consumption of means of production reflects the technological rigidity of the production function, while the lag of hedonic consumption exposes the cognitive stickiness in the transition from traditional small farmers to modern operators.

Based on these considerations, the following hypothesis was advanced:

Hypothesis 1:

Land transfer-in/out has a positive impact on the consumption behaviour of older farmers.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Income

The mechanism of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers is essentially a process of income reconstruction driven by factor reallocation, and its path of action can be systematically deconstructed through the framework of new institutional economics. Income serves a dual function in the transmission chain of ‘land transfer–consumption enhancement’, which is both an economic representation of the efficiency of factor reallocation and an institutional breakthrough point in the constraints on consumption behaviour [47,48].

For older farmers who choose to move land transfer-out, the mediating effect of income can be deconstructed into the following transmission paths. First, the stabilisation effect of property income. The land transfer-out contract management rights form stable property income, and its anti-cyclical characteristics effectively compensate for the loss of productive income of older farmers due to the decline of labour capacity [49,50]. Second, the incremental effect of wage income. The labour resources released by the exit of land elements are transformed into wage income through occupational restructuring, which is strengthened by the dual role of the expansion of labour demand for agricultural industrialisation and the increase in non-farm employment opportunities, and its incremental effect is continuously amplified by the interaction between the labour participation rate and the hourly wage rate [51,52]. Third, the structural upgrading of risk defence ability. The negative correlation between property income and wage income forms a natural hedging mechanism, which reduces the magnitude of income fluctuations and promotes the consumption behaviour of older farmers from survival maintenance orientation to quality of life optimisation orientation. The diversification of income structure enhances the economic risk resilience of older farmers, reduces their dependence on a single source of income, and improves their psychological tolerance in the face of uncertainty and unexpected situations, thus enhancing their consumption capacity [53,54]. According to the precautionary savings theory, improved income enhances the sense of economic security of older farmers, allowing them to meet their daily basic needs with less concern about future uncertainty and shift more resources to non-essential consumption areas [55].

Currently, the widespread land fragmentation and decentralisation of business models in rural China has become a structural contradiction that restricts the development of the rural economy [56], the direct consequences of which can be seen in the loss of efficiency in the allocation of land factors and the diseconomies of scale in agricultural production, and the root causes of which can be traced back to the initial ‘fairness first’ logic of property rights allocation under the household contract responsibility system [57]. Older farmers’ choice of land transfer-in constitutes an institutional breakthrough from the traditional land management paradigm, and realises multiple economic effects through the reorganisation of production factors. From the perspective of the production function, the upgrading of the production function triggered by land transfer-in is reflected in three aspects: firstly, the expansion of land scale reduces the fixed cost per unit area through the incremental effect of returns to scale, optimising the marginal allocation efficiency of production factors [58]. Secondly, centralised and contiguous operation effectively overcomes the externalities of the transaction costs caused by the dispersal of parcels of land, which makes the application of agricultural machinery and equipment and the diffusion of technology possible [59]. Thirdly, the breakthrough of the operation scale threshold enhances the risk resilience of older farmers, both in terms of the natural risk diversification mechanism and in terms of improved market bargaining power. The systematic improvement of the production function ultimately translates into the enhancement of older farmers’ business income, and its income-enhancing effect is verified in the dimensions of cost margin, total factor productivity, and market competitiveness [60]. As far as the income–consumption transmission mechanism is concerned, structural improvements in economic returns reshape the consumption behaviour of older farmers. Studies have shown that income growth from land transfer-in is characterised by a significant non-farming consumption tendency, i.e., after the elasticity of basic subsistence needs is saturated, the new income mainly flows to health capital, intergenerational human capital, quality of life improvement, and cultural consumption upgrading [61]. The Pareto improvement of consumption structure is not only reflected in the vertical upgrade of consumption level, but also in the horizontal expansion of consumption diversity, signalling that older farmers are experiencing a shift from subsistence consumption to healthy and hedonic consumption.

Based on these considerations, the following hypothesis was advanced:

Hypothesis 2:

Income plays a mediating role in the process of land transfer-in/out, influencing the consumption behaviour of older farmers.

2.3. Two-Way Land Transfer and Consumption Behaviour of Older Farmers

In the process of land transfer, the fact that older farmers often engage in both land transfer-out and land transfer-in at the same time must be taken into account when studying the consumption behaviour of older farmers. The optimisation of consumption behaviour by older farmers through the synergistic allocation of land transfer-out and land transfer-in is essentially an adaptive strategy to cope with life cycle constraints [62]. In the context of two-way land transfer, the synergistic effect of factor replacement shapes the consumption behaviour of older farmers, a process that is different from the simple linear superposition of land transfer-out or land transfer-in, where two-way land transfer achieves intertemporal equilibrium between risk and return through Pareto improvements in asset portfolios.

Firstly, a dynamic optimisation mechanism for resource reallocation. Fragmented land outflow releases sunk costs, and by disposing of fragmented plots with low marginal output, older farmers can divest themselves of unproductive burdens [16]. Meanwhile, contiguous land transfer-in forms technologically adapted farming units through the integration of plots with high output potential [17], and this “removing the bad and reserving the best“ resource reallocation strategy is essentially a structural upgrading of the production function through dynamic screening of land assets. Secondly, the complementary reconstruction of cash flow structure. Rental income and operating income form a complementary temporal structure of cash flow, i.e., the fixed rent generated by land transfer-out provides immediate liquidity security and meets basic consumption needs [63], while the income from economies of scale brought by land transfer-in supports the expectation of long-term asset value-added [64], which provides a sustainable impetus to the consumption behaviour of the older farmers. The two-pillar system of ‘short-term liquidity protection and long-term asset appreciation’ can alleviate the vulnerability of consumption fluctuations under the traditional single-income agricultural model. Thirdly, the adaptive restructuring of the intergenerational contract. The dynamic adjustment of land tenure is embedded in the process of family intergenerational relationship reconstruction, through part of the management right in exchange for children’s support for technical inputs or market connections, forming an invisible contract of ‘intergenerational equity replacement—intergenerational collaboration reinforcement’ [65,66]. The transfer strategy of ‘orderly entry and exit’ is essentially to internalise intergenerational cooperation capital through institutional transaction costs, and to activate the consumption potential of older farmers through intra-household resource reallocation.

Based on these considerations, the following hypothesis was advanced:

Hypothesis 3:

Two-way land transfer has a positive impact on the consumption behaviour of older farmers.

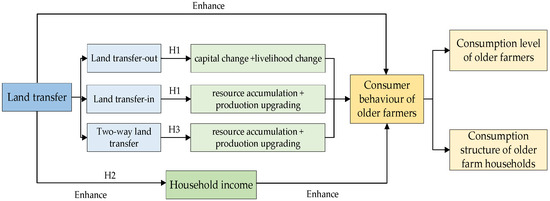

Based on the above theoretical analysis, this paper constructs an analytical framework for the impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Analytical framework.

2.4. Data and Processing

The China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a comprehensive social tracking survey database with international impact, is conducted by the China Social Science Research Centre of Peking University. The survey adopts a multi-stage stratified probability sampling method; its sampling area covers 25 provinces/municipalities/autonomous regions in China, and the survey object contains all family members in the sample households. This study selects four periods of balanced panel data in 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022, focusing on the rural older groups who participated in the four rounds of the survey and received a collective allocation of land. The sample is screened based on the following criteria: firstly, the study is restricted to the agricultural population aged 60 and above who hold rural household registration; secondly, they own collectively allocated land. By eliminating observations with missing key variables and extreme outliers, 6321 valid samples were formed.

2.5. Variable Selection

2.5.1. Dependent Variables

The dependent variables of this study are the consumption behaviour of older farmers, covering two dimensions: total consumption and consumption structure. Total consumption (Tc) is measured by the questionnaire, ‘In the past 12 months, how much did your household spend on daily expenses such as food, clothing, housing and transport, education, medical care, culture and leisure, and gifts for family members?’ This variable integrates comprehensive expenditure items such as basic living expenses, human capital investment, and social and cultural consumption, and can effectively characterise the overall scale of economic resource allocation of older farmers. In the dimension of consumption structure, regarding the classification method of existing studies [67] and taking into account the heterogeneous characteristics of consumption of older farmers, a four-dimensional functional consumption classification framework is constructed: (1) subsistence consumption (Sc), which covers expenditures on basic needs, such as food, clothing, and housing; (2) healthy consumption (Hc), which includes expenditures on medical treatment, health care, and insurance; (3) developmental consumption (Dc), which includes expenditures on ability enhancement, such as transport and communication, and education; (4) hedonic consumption (Hc’), which involves cultural entertainment, tourism and other quality of life improvement expenditures. This classification system strengthens the theoretical interpretation of the specificity of the consumption behaviour of older farmers by introducing health-oriented consumption. To eliminate the difference in magnitude and meet the requirements of model parameter estimation, all consumption variables are processed with a natural logarithmic transformation.

2.5.2. Independent Variables

The independent variable of this study is land transfer. As a core production factor for the livelihood maintenance of older farmers, land not only plays the economic function of a basic production factor, but also assumes the risk mitigation role of an informal social security mechanism when the dual social security structure of urban and rural areas has not yet been fully integrated. Based on the multidimensional attribute characteristics of land, this study incorporates four types of agricultural land resources—arable land, forest land, pasture land, and water ponds—into a unified analytical framework to systematically examine the impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers. At the level of operationalised definitions, land transfer-out is measured by the questionnaire, ‘In the past 12 months, did your household rent out the land allocated by the collective to other people, whether or not you received rent?’ Land transfer-in is measured by the questionnaire, ‘In the past 12 months, excluding land allocated collectively, did your household rent land to individuals or collectives, with or without paying rent?’ Older farmers are assigned a value of 1 when there is a land transfer-out or land transfer-in, and a value of 0 when there has not been any transfer.

2.5.3. Control Variables

This study mitigates the problem of omitted variable bias by including control variables covering four dimensions: (1) demographic characteristics (age, political, marital status, health status, education level); (2) household endowment characteristics (number of household members, household income, and assets and loan); (3) participation in the social security system (status of health insurance participation, government assistance, and social assistance); and (4) Internet characteristics (mobile phone).

2.5.4. Mediating Variable

This study establishes the total income of older farmers as the mediating transmission path in the theoretical mechanism. Based on the composite characteristics of the income composition of older farmers, production and management income (agricultural cultivation, animal husbandry, etc.), asset income (land transfer rent, etc.), transfer income (pension, government subsidies, etc.), and social network income (gifts, etc.) are all taken into account. This variable was measured by the questionnaire ‘In the past 12 months, how much did your household’s income add up to, including business income, wage income, rental income, pension income, various government grants or financial support from others, gifts, etc.?’ By integrating heterogeneous incomes such as income from productive operations, wage compensation, asset rental income, social security transfers and social capital realisation, the total income of older farmers can be systematically characterised. To eliminate the difference in magnitude and meet the model parameter estimation requirements, the mediating variables are processed with natural logarithmic transformation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variable definitions and descriptive statistics.

2.6. Model Construction

To assess the impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, this study constructed two baseline regression models (1) and (2), with total consumption and consumption structure as the dependent variables and land transfer as the independent variable. The formulas are as follows:

Formulas (1) and (2) represent the impact of land transfer-out and land transfer-in on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, respectively. denotes the natural logarithm of the consumption expenditures of various types of older farmers in year , including subsistence consumption, healthy consumption, development consumption, hedonic consumption, and total consumption; denotes whether or not older farmers transfer-out of the land in year , and denotes whether or not older farmers transfer-in land in year ; denotes the control variable; denotes the time fixed effect; denotes the area fixed effect; , , is the surrogate estimation parameter; and and denotes the random perturbation term.

Given that the land transfer behaviour of older farmers may be affected by a variety of non-random factors, the presence of these factors may cause sample selection bias. If the baseline models (1) and (2) are used directly for estimation, the sample self-selection problem may lead to bias in the estimation results, thus affecting the accuracy of the conclusions [68]. To effectively control the bias of the estimation results, this study adopts the propensity score matching (PSM) to overcome the endogeneity problem caused by sample self-selection [69].

where denotes whether or not the older farmer participates in land transfer, 1 for older farmers who participate in land transfer (treatment group), for older farmers who do not participate in land transfer; is the characteristic variable affecting the consumption behaviour of older farmers; denotes the conditional probability of older farmer participation in land transfer given covariate with a range of values of [0, 1]; and , , are the model parameters. The propensity score matching constructs an unbiased control group by estimating a ‘propensity score’ for each observation unit, i.e., the probability of its participation in land transfer, and then matching based on this probability. By matching participants and non-participants in land transfers on the propensity score, the endogeneity problem caused by selection bias can be effectively reduced, and the causal impact of land transfers on the consumption behaviour of older farmers can be more accurately assessed. The method helps to control confounding factors that may affect land transfer decisions and consumption behaviour, and improves the robustness and reliability of the analysis results. As a result, the impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers can be tested more scientifically with the elimination of endogeneity bias.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables

Table 2 shows that from 2016 to 2022, the proportion of land transfer-out to older farmers in China increased from 17.10 per cent in 2016 to 23.79 per cent in 2022, which is basically in line with the existing studies [7]. However, the proportion of land transfer-in to older farmers decreased by about 3.46 per cent from 2016 to 2022. In terms of two-way land transfer, it increased by approximately 0.31 per cent from 2016 to 2022. The above data show that the dominant trend of land transfer-out confirms that rural areas are experiencing intergenerational occupational differentiation, with the transfer of young labour forcing older groups to adjust their land strategies, while the lack of vitality in two-way land transfer reflects the lagging development of rural land property rights trading markets, and the urgent need to establish standardised transfer platforms and risk-sharing mechanisms.

Table 2.

Basic situation of land transfer among older farmers from 2016 to 2022 (unit: %).

Table 3 demonstrates the differential impact of land transfer heterogeneity on the consumption behaviour of older farmers. (1) In terms of land transfer-out, the total consumption of older farmers participating in land transfer-out is cumulatively higher than that of non-transfer-out older farmers by CNY 6103.830 (from 2016 to 2022), with subsistence consumption (CNY +3904.140) and healthy consumption (CNY +1964.910) constituting the main increment, and developmental consumption (CNY +95.136) and hedonic consumption (CNY +443.462) show marginal improvement. (2) In terms of land transfer-in, although the total consumption of land transfer-in older farmers is higher than that of non-transfer-in older farmers, their consumption structure shows significant heterogeneity—subsistence, healthy, and developmental consumption have increased significantly, while hedonic consumption has not increased. It is worth noting that, except for developmental consumption, all other consumption indicators of land transfer-in-only older farmers are lower than those of land transfer-out-only older farmers, revealing that land transfer-out may have a stronger consumption promotion effect. (3) Older farmers who participate in both land transfer-out and land transfer-in are characterised by consumption upgrading: their total consumption reaches CNY 49,289.310, and their subsistence, healthy, and hedonic consumption is significantly higher than that of older farmers who only have land transfer-out or land transfer-in.

Table 3.

Differences in consumption characteristics of older farmers in different land transfer situations (unit: yuan).

Table 4 reveals the differential impact of land transfer heterogeneity on the income of older farmers. (1) In terms of land transfer-out, the total incomes of older farmers who chose to land transfer-out were higher than those of older farmers who did not land transfer-out by CNY 11,611.570. (2) In terms of land transfer-in, the total incomes of the older farmers who land transfer-in were higher than those who did not land transfer-in by CNY 5958.510, but the income-generating effect of land transfer-in was weaker than that of land transfer-out. (3) The total incomes of older farmers with two-way land transfer are higher than those of older farmers with only land transfer-out or land transfer-in by CNY 15,324.120 and CNY 22,085.990, respectively, highlighting the double dividend of land resource reallocation and optimisation of agricultural operation efficiency. The above findings explain the rural land market’s promotion of income growth for older farmers, confirming the structural role of the reform of the agricultural land transfer system in alleviating poverty among older farmers.

Table 4.

Differences in income characteristics of older farmers in different land transfer situations (unit: yuan).

3.2. The Impact of Land Transfer on the Consumption Behaviour of Older Farmers

Considering the robustness of the model, this study adds all other influencing factors into the econometric model to examine the effects of land transfer-out and land transfer-in on the consumption behaviour of older farmers. The estimation results of the four groups of models for the consumption behaviour of older farmers are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers.

Table 5 reveals the impact of land transfer-out and land transfer-in on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, (1) to (5) indicate the impact of land transfer-out on the total consumption and consumption structure of older farmers, and (6) to (10) indicate the impact of land transfer-in on the total consumption and consumption structure of older farmers. The results of the study show that land transfer-out significantly increases the total consumption scale of older farmers (β = 0.136, p < 0.01), with relatively higher expenditures on healthy consumption (β = 0.180, p < 0.01) and hedonic consumption (β = 0.185, p < 0.05), which indicates that the asset-based income induced by the land transfer-out is more inclined to improve the investment in health and the quality of life enhancement. Older farmers with land transfer-in also showed a significant increase in total consumption (β = 0.084, p < 0.05), but their consumption structure showed survival rationality, with subsistence consumption (β = 0.091, p < 0.01) and healthy consumption (β = 0.159, p < 0.01) constituting the main increment, reflecting that the income stream generated by land transfer-in through the expansion of agricultural business is more used for basic needs satisfaction and risk prevention reserves. Controlling for other variables, land transfer not only significantly increases the total consumption of older farmers, but also drives the transformation of the consumption structure of older farmers. Therefore, the above findings confirm the validity of research hypothesis H1.

Control variables such as demographic characteristics, family endowment characteristics, social security system participation and internet characteristics showed significant heterogeneity in their impact on the consumption behaviour of older farmers. Older farmers who are married, have poorer health, party membership, are engaged in non-farm employment, have higher levels of education, have higher household incomes, have loans in the household, have a larger number of household members, and use smartphones generally have higher total consumption.

Further analysing the different types of consumption, the impact of control variables on the consumption behaviour of older farmers showed variability. In terms of subsistence consumption, age, health status, political profile, whether non-farm employment, education level, household income, number of household members, government subsidies and whether using smartphones have a significant impact on subsistence consumption. In terms of health consumption, age, marital status, health status, whether non-farm employment, education level, household income, whether having loans, and number of household members have a significant impact. In terms of developmental consumption, age, marital status, household income, whether there is a loan, number of household members, and whether there is smartphone use have a significant impact on developmental consumption. In terms of hedonic consumption, age, whether there is non-farm employment, household income, number of household members, government subsidy, and whether there is smartphone use have a significant impact on hedonic consumption. In summary, the control variables have different degrees of impact on different types of consumption, indicating that the consumption behaviour of older farmers is affected by a combination of factors.

3.3. Robustness Tests

In this study, the robustness of the underlying regression results was tested in terms of the substitution of independent variables, propensity score matching, instrumental variables method, and sub-sample.

3.3.1. Robustness Test 1: Replacement of Independent Variables

To exclude endogeneity bias that may result from measurement bias, drawing on the practice of an existing study [70], land transfer-out funds and land transfer-in expenditures are used as proxy variables for land transfer-out and land transfer-in, respectively, for the robustness test. The land transfer-out funds represent the economic gains obtained by older farmers through land transfer-out, and the land transfer-in expenditures reflect the funds paid by older farmers for land transfer-in. The two proxy variables can effectively mitigate the measurement errors that may exist between the actual amount paid for land transfer-out and land transfer-in behaviours and the survey data, and improve the accuracy and reliability of the estimation results. The regression results in Table 6 show that the direction and significance level of the coefficients of the land transfer-out funds and land transfer-in expenditures are consistent with the results of the benchmark regression, indicating that the conclusions obtained are not affected by the measurement bias after using the proxy variables for the robustness test, thus verifying the robustness of the benchmark regression results. In the baseline regression, the ‘developmental consumption’ variable did not reach statistical significance, so the study does not show the results of its robustness test.

Table 6.

Robustness test I: Replacement of independent variables.

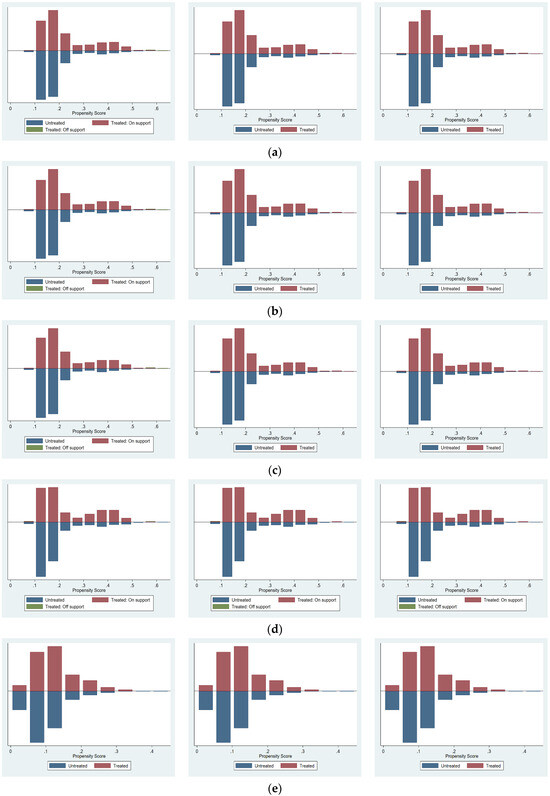

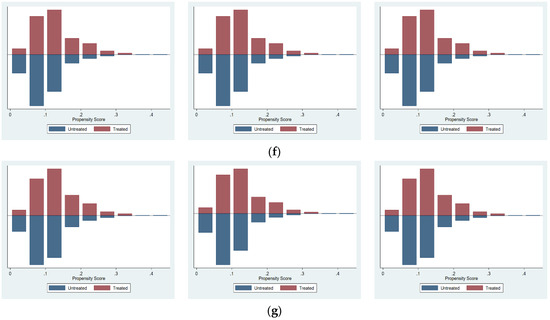

3.3.2. Robustness Test 2: Propensity Score Matching

To eliminate the endogeneity problem due to possible selectivity bias in the sample, the propensity score matching was used for robustness testing. The control and experimental groups were matched according to the control variables in Table 5, and the older farmers with land transfer-out and land transfer-in were set as the experimental group, and the older farmers with no land transfer-out and no land transfer-in were set as the control group. On this basis, the average treatment effects of land transfer-out and land transfer-in are estimated using the nearest neighbour matching method, radius matching method, and kernel matching method, respectively. The results of the common support condition test shown in Figure 2a–g indicate that all the observations under the three matching methods fall within the common support range, indicating that the matched samples satisfy the balance requirement, the matching quality is high, and the endogeneity problem that may be caused by the sample selectivity bias is effectively ruled out.

Figure 2.

(a). Total consumption with and without land transfer-out. (b). Subsistence consumption with and without land transfer-out. (c). Healthy consumption with and without land transfer-out. (d). Hedonic consumption with and without land transfer-out. (e). Total consumption with and without land transfer-in. (f). Subsistence consumption with and without land transfer-in. (g). Healthy consumption with and without land transfer-in.

The results in Table 7 present the estimated treatment effects of land transfer-out and land transfer-in on the consumption behaviour of older farmers. The average treatment effects on the treated (ATT) obtained based on the nearest-neighbour matching method, radius matching method, and kernel matching method all indicate that both land transfer-out and land transfer-in have a significant positive impact on the total and various types of consumption of older farmers. Taking the estimation results of the nearest neighbour matching method as an example, controlling for other variables, land transfer-in raises the total, subsistence, and healthy consumption of older farmers by 12.89% (exp (0.1212)-1), 13.19% (exp (0.1239)-1), and 17.16% (exp (0.1584)-1), respectively. Similarly, land transfer-out significantly increased total, subsistence, healthy, and hedonic consumption of older farmers by 5.31% (exp (0.0517)-1), 4.93% (exp (0.0481)-1), 16.37% (exp (0.1516)-1), and 27.30% (exp (0.2414)-1), respectively. The above results are consistent with the findings of the benchmark regression analysis, which further validates the promotion effect of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers and indicates the robustness of the benchmark regression results.

Table 7.

Robustness test II: Re-estimation using PSM.

3.3.3. Robustness Test 3: Instrumental Variable

The impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers may lead to endogeneity problems due to the presence of reverse causality and omitted variables, when the direct use of the Ordinary Least Squares estimation method may lead to bias in the estimation. Therefore, the instrumental variable method is used to eliminate the endogeneity problem caused by reverse causality and omitted variables. Drawing on the practice of an existing study [71], ‘the percentage of land transfer-out older farmers in the total number of households in the village other than their own’ and ‘the average expenditure on land transfer-in of other older farmers in the village other than their own’ are selected as the land transfer-out and land transfer-in instrumental variables, and estimated using two-stage least squares.

Valid instrumental variables need to satisfy two basic conditions: firstly, the instrumental variables are highly correlated with the endogenous independent variables; secondly, the instrumental variables are not related to the disturbance terms. The test results in Table 8 show that, firstly, the F-value of the first-stage regression is much larger than 10, which excludes the possibility of weak instrumental variables; secondly, the results of the DWH-Chi2 test rejected the original hypothesis that the land transfer-out and land transfer-in variables are exogenous at the 1 per cent level, which verifies the exogenous nature of the selected instrumental variables. Therefore, the instrumental variables used in this study passed rigorous tests in terms of relevance and exogeneity and met the basic requirements of instrumental variables. After eliminating the endogeneity problem caused by reverse causality and omitted variables, the estimated coefficients of both land transfer-out and land transfer-in variables are consistent with the benchmark regression results in terms of significance and direction, indicating the robustness and credibility of the benchmark regression results.

Table 8.

Robustness test III: Re-estimation using instrumental variables.

3.3.4. Robustness Test 4: Subsample Tests

Considering the large differences in the health status of older farmers, referring to the practice of existing studies [7], older farmers are divided into a group with health status higher than the health average and a group with health status lower than the health average, based on the mean value of the sample’s health scores, and the impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of the two groups is estimated separately. The estimation results in Table 9 show that the impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers exhibits variability among older farmers with different health statuses. For land transfer-out older farmers, land transfer-out significantly increases consumption levels regardless of whether their health status is above or below the mean, a finding that is consistent with the results of the benchmark regression.

Table 9.

Robustness test IV: Sub-sample test (transfer-out).

Similarly, the estimation results in Table 10 show that for land transfer-in older farmers, land transfer-in equally significantly enhances their consumption levels regardless of their health status. It is worth noting that the difference in health level does not change the promotion effect of land transfer-in on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, but rather further validates the robustness of the land transfer-in effect. The above results indicate that the health status of older farmers does not significantly modulate the relationship between land transfer and consumption behaviour, and that the enhancing effect of land transfer on consumption level is stable across the group of older farmers with different health status. This finding reinforces the reliability of the baseline regression results and suggests that the consumption-enhancing effect of land transfer is universal.

Table 10.

Robustness test IV: Sub-sample test (transfer-in).

3.4. Mechanism Analysis

The results of the benchmark regression and robustness test indicate that land transfer can increase the consumption level of older farmers. Therefore, this study further explores the internal transmission mechanism of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers using the mediation effect model. It is worth noting that land transfer-out and land transfer-in represent the livelihood patterns of different types of older farmers, respectively. Previous studies have measured the incomes of land transfer-out older farms through rental income and wage income, and the incomes of land transfer-in older farms through productive income [68]. However, as the income of outgoing older farmers may also include productive income, and the income of in-flowing older farmers may also include wage income, it is difficult for a single income indicator to fully reflect the characteristics of the income structure of older farmers. In contrast, total household income can more accurately reflect the overall economic situation of older farmers. Therefore, this study selects total household income as the mediating variable of the impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers. According to the estimation results in Table 11, both land transfer-out (β = 0.141, p < 0.01) and land transfer-in (β = 0.115, p < 0.05) have a significant positive impact on the income of older farms, and the impact of land transfer-out and land transfer-in on income presents an asymmetric feature—the income effect of land transfer-out is stronger than that of land transfer-in, a finding that structurally echoes the heterogeneous character of the impact of land transfer-out on the consumption behaviour of older farmers in the benchmark regression. From this, it can be inferred that income is an important transmission path for land transfer to act on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, and the economic effect of land transfer-out has stronger transmission effectiveness. Research hypothesis H2 is verified.

Table 11.

Intermediary effect test.

3.5. Interaction Term: The Effect of Two-Way Land Transfer on the Consumption Behaviour of Older Farmers

Although the various types of consumption of land transfer-out older farmers are higher than those of land transfer-in older farmers, their consumption behaviour may be potentially influenced by land transfer-in; conversely, the consumption behaviour of land transfer-in older farmers may be shaped by land transfer-out decisions. This suggests that land transfer is not a single behaviour, and that the co-existence of land transfer-out and land transfer-in may have a non-linear impact on the consumption function of older farmers through resource reallocation effects and risk hedging mechanisms. For this reason, this study breaks through the traditional unidimensional analytical framework, constructs the interaction term of land transfer-out and land transfer-in, and examines the impact of two-way land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers. The regression results in Table 12 show that there is a significant positive effect of bidirectional land transfer on the total consumption behaviour of older farmers (β = 0.186, p < 0.05), and the effect is heterogeneous in the consumption structure dimension: subsistence consumption (β = 0.306, p < 0.01) and hedonic consumption (β = 0.382, p < 0.1) are significantly elevated, but healthy consumption and development consumption do not show significant changes. Research hypothesis H3 was verified. This result suggests that analysing the interaction effect of land transfer-out and land transfer-in is important for a comprehensive understanding of the impact of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers.

Table 12.

The effect of interaction terms on the consumption of older farmers.

4. Discussion

This study systematically assesses the impact of land transfer (land transfer-out and land transfer-in) on the consumption behaviour of older farmers by constructing a two-way fixed-effects model, and explores the mediating role of income in this process. The empirical analysis based on the four-period panel data of the China Family Panel Studies shows that there is an institutional dependence feature in the release of the policy effectiveness of land transfer, which is an important revelation for the improvement of market-based reform of rural factors.

The design and implementation of land transfer policies cannot only focus on the appearance of land transfer behaviour, but also need to focus on cracking the institutional barriers of low willingness to land transfer, to fully release their consumption potential. This study found that the sample of older farmers has low land transfer motivation, and this phenomenon has been confirmed [7,72]. Possible explanations for the low motivation of older farmers to transfer land include: firstly, the psychological profile of older farmers who regard land as the ‘last line of defence’, which leads to the fact that they would rather bear the opportunity cost of inefficient operation than realise the release of asset value through transfer [73]; secondly, it is difficult for older farmers to accurately assess the potential risks of land transfer contracts, and they tend to adopt the ‘status quo preference’ strategy, which creates a lock-in effect in factor allocation [74]; thirdly, the uncertainty of non-standardised land transfer contracts forces older farmers to set aside excess risk premiums, which substantially reduces the space for potential net returns. Despite the above institutional constraints, land transfer still exhibits significant consumption promotion effects. To address institutional frictions in the land transfer process, the Chinese government has promoted the establishment of a system of registration of land management rights and filing of land transfer records through the Rural Land Contract Law, with the aim of reducing transaction costs and building a risk-hedging mechanism through the clarification of property rights. In China, land transfer refers to the process of transferring land contracting rights from farmers to other business entities through market-based mechanisms on the basis of adhering to the collective ownership of rural land and the family contracting system, with the core being the implementation of the reform of the ‘separation of three rights’, i.e., clarifying collective land ownership, stabilising the contracting rights of farmers, and revitalising the right to operate the land [75]. The forms of transfer mainly include subcontracting, leasing, shareholding, transferring, trusteeship, etc. Of these, leasing and shareholding account for the highest proportion, the former through the rent to achieve short-term transfer, and the latter with land management rights to join a co-operative or enterprise to share the benefits [76]. The transfer process needs to follow the provisions of the Rural Land Contracting Law, whereby farmers and new management subjects (such as co-operatives, family farms, and agribusinesses) sign a written contract after negotiation, specifying the transfer period, use restrictions, and compensation, and report it to the village collectives and the township agricultural economics departments for record and registration. Local governments provide services such as contract authentication and dispute mediation through the establishment of property rights trading centres and information platforms, and have strengthened their supervision of ‘off-farming’ and ‘off-food’ practices.

4.1. Land Transfer Has a Positive Impact on the Consumption Behaviour of Older Farmers

This study found that land transfer-out has a significant enhancing effect on the consumption behaviour of older farms, a finding that is consistent with that of previous studies [40]. This may be attributed to the de-agrarianisation effect of land transfer-out restructuring the asset structure of older farms, which not only diversifies non-farm income sources by converting land assets into stable rental income, but more critically reduces agricultural production risks, thus unleashing room for improvement in marginal consumption propensity [12,39,43]. It is worth noting that the promotional effect of land transfer-out on the developmental consumption of older farmers is not obvious, and the phenomenon can be explained in several ways: firstly, the mechanism of mismatch between the nature of income and the duration of consumption. Developmental consumption usually requires intertemporal decision support, requiring long-term stability and growth expectations of income sources [77], but older farmers are constrained by the life cycle stage, and there is an intrinsic contradiction between the return cycle of their human capital investment and the physiological ageing process, which leads to a significantly high intertemporal discount rate of developmental consumption among older farmers. Secondly, risk perception and behavioural preference lock-in effect. Older farmers generally have ‘land plot’ and ‘physical asset’ preferences. Although land transfer-out brings cash income, it does not fundamentally change their risk-averse decision-making mode; instead, they prioritise compensatory consumption over productive investment [78]. Thirdly, social capital and information access barriers. The realisation of developmental consumption is highly dependent on social network support and access to information channels [79], and the marginalised position of older farmers in the non-farm sector limits their access to developmental consumption.

At the same time, land transfer-in also has a positive impact on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, a finding that contradicts the findings of previous studies. Previous studies have generally concluded that land transfer-in leads to a decrease in the consumption level of farm households. This is mainly due to the fact that the continuous input of production factors crowds out the disposable income of households, and at the same time, the increase in business risk generated by the expansion of land scale forces farmers to increase the motivation of precautionary savings, which leads to structural suppression of consumption expenditures [9]. However, this study finds that the consumption level of land transfer-in to older farmers has increased. There are several possible explanations for this. Firstly, this study focuses on older farmers, a group which, through the expansion of land operation scale, has enhanced their sense of economic security and lowered their preventive saving motives; secondly, the panel data adopted in this study are better able to capture the dynamic process of consumption behaviour than the cross-sectional data of previous studies; thirdly, the majority of previous studies focused on specific regions with relatively limited sample sizes [80]. Expanding the scale of land operation allows older farmers to make full use of the resource integration capacity and mechanisation under scale operation as a condition to optimise the efficiency of the allocation of production factors and reduce the unit production cost, thus releasing the consumption potential.

The positive impact of land transfer-in on the consumption behaviour of older farmers can be attributed to the following points. Firstly, the expansion of land scale breaks through the technological application threshold of traditional decentralised management, enabling older farmers to access the modern agricultural technology system, which not only alleviates the physical limitations of the aged labour force but also generates a ‘technological dividend’ through the improvement of total factor productivity, whose spillover effect is reflected in the increase in disposable income and optimisation of the consumption structure. Secondly, the expansion of land scale reconfigures intergenerational family relations by increasing the economic autonomy of older farmers, reducing their dependence on economic transfers from their children and thus giving them greater subjectivity in their consumption behaviour [81].

Two-way land transfer has a significant impact on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, but this finding has not been systematically addressed in existing studies. The ‘two-way interaction’ of land transfer affects the consumption behaviour of older farmers by reconfiguring their asset allocation patterns, which may be explained by the following: firstly, risk diversification and income smoothing mechanisms. By transferring out land with low marginal output, older farmers obtain stable rental income, which improves the relaxation of budget constraints. At the same time, the selective transfer-in of high-quality land realises the optimal reorganisation of production factors, forming the dual effect of ‘risk diversification and income superposition’, and providing continuous cash flow support for the improvement of consumption behaviours. Secondly, the mechanism of balancing asset liquidity and specialisation. The transfer-out of fragmented land releases the sunk cost of assets [16], while the transfer-in of contiguous land enhances the return of asset exclusivity through economies of scale [17]. The allocation strategy of ‘in and out’ not only avoids the identity crisis caused by the complete withdrawal from agriculture, but also enhances the intertemporal consumption through the optimisation of the asset portfolio, forming the synergistic effect of ‘short-term cash flow improvement—long-term asset appreciation’. Finally, the life cycle adaptation mechanism. Older farmers transfer-out of sloping land that is more difficult to cultivate, reducing the physical load, and at the same time transfer-in the land that is suitable for mechanisation in order to adapt to mechanised production. The strategy of ‘selective large-scale operation’ reduces the intensity of labour while maintaining moderate participation in agriculture, releasing the time budget for leisure consumption, and promoting a change in the consumption structure to a hedonic and health-oriented one.

The above findings can be elucidated by behavioural economics theories, in particular the explanatory power of prospect theory and mental accounts on the land transfer decisions of older farmers. Firstly, risk aversion and the consumption effect of land transfer-out. Older farmers are generally loss-averse, and their land transfer decisions are affected by the ‘endowment effect’: they are more concerned about the risk of loss of control due to land transfer-out than the potential benefits of land transfer-in. However, once a stable rental income is generated from land transfer-out, their psychological profile will shift from ‘productive assets’ to ‘security savings’, triggering the consumption budget constraint, which can well explain why land transfer-out can promote the consumption of older farmers. Secondly, the perceived stickiness between status quo preferences and land transfer-in. Older farmers’ cautious attitude towards land transfer-in can be attributed to status quo bias. Expanding land management can improve income, but they will need to bear the double risk of technical adaptation failure and market fluctuations. Older farmers are more sensitive to short-term costs than long-term benefits, resulting in developmental consumption failing the significance test. Thirdly, the synergistic effect of social norms and two-way transfer. The consumption-promoting effect of two-way land transfer is embedded in social preferences: the liquidity support gained from the transfer-out of fragmented plots and the demonstration effect of the transfer-in of contiguous land jointly reduce the social risk perception of older farmers and promote the improvement of consumption level and structure.

4.2. Income Mediates the Impact of Land Transfer on the Consumption Behaviour of Older Farmers

It has been revealed that rental income or non-farm income has a mediating attribute in the transmission chain of land transfer and consumption behaviour, and its mechanism of action presents significant heterogeneity in transfer status [82]. This study verifies through the mediating effect model that total household income is the key pivot of land transfer affecting the consumption behaviour of older farmers, and the intensity of its role presents significant differences depending on the direction of land transfer. The transmission logic can be deconstructed as follows:

In the land transfer-out scenario, the mediating effect of total household income is the transformation of asset forms. Firstly, the capitalisation of land management rights releases a continuous flow of rents, which reshapes the consumption expectations of older farmers through the stability of cash flows [74]; second, the labour force released by the land transfer-out is transformed into incremental wage income through non-farm employment channels, and this change in the nature of income not only enhances the purchasing power of older farmers, but also promotes the modernisation of consumption perceptions through the transformation of occupational identities [42]. In this process, the intermediary role of total household income is reflected in the transmission loop of ‘stable cash flow enhancement—optimisation of consumption decision-making over time’, and the synergistic growth of rental income, non-farm income and other incomes drives the growth of consumption behaviour of older farmers.

In the land transfer-in scenario, the income transmission path is then factor reward reconstruction. Firstly, the total factor productivity increase brought about by large-scale operation enlarges the base of operating income of older farmers through the value-added from agricultural surplus value [83]. Secondly, mechanisation replaces a proportion of labour cost, which not only reduces the physical exertion in the production process but also improves the production efficiency through the application of precision agriculture technology [84], forming a virtuous cycle of ‘high efficiency—high income—high consumption’. Thirdly, the land asset premium effect strengthens the resilience of the balance sheet of older farmers through the premium effect of land assets, which is a reconstruction of factor rewards. Under this path, the intermediary role of total household income presents the chain reflection of ‘upgrading the production function-income base expansion-consumption structure iteration’, which pushes older farmers to break through the traditional consumption pattern of ‘keeping expenditure within the limits of revenues’, and adopt consumption planning for the whole life cycle. The ability to plan consumption for the whole life cycle.

The asymmetry of the intermediary effect maps out a profound institutional logic: land transfer-out releases the value of precipitated assets by removing ‘de-small farming’, and its consumption promotion effect relies more on the stability of cash flow. Meanwhile, land transfer-in raises the remuneration of factors through ‘re-agriculturalisation’, and its consumption driving mechanism places more emphasis on income growth. Its consumption-driven mechanism places more emphasis on the sustainability of income growth. The transformation of the mechanism for generating total household income has provided a systemic breakthrough for breaking the vicious circle of ‘low income—low consumption’ among older farmers.

4.3. Heterogeneity Exists in the Impact of Land Transfer on the Consumption Behaviour of Older Farmers

The heterogeneity analysis in this study reveals that there is heterogeneity in the impact of land transfer-out on the consumption behaviour of older farmers with different health levels. The effects of land transfer-out and land transfer-in on consumption behaviour are consistent with the results of the baseline regression for older farmers with higher than average health levels, while land inflow does not have a significant effect on hedonic consumption for older farmers with lower than average health levels. Possible explanations for this result are that older farmers with above-average health levels obtain a continuous income stream by extending the agricultural production cycle, which strengthens the ability to secure a base for subsistence consumption, while the complementary effects of health capital and land capital induce older farmers to allocate more resources to preventive health investments [85], and the physical fitness advantage reduces the dependence on child care, which strengthens consumption decisions. The advantage of physical fitness reduces the degree of dependence on children’s care, strengthens the autonomy of consumption decision-making, and promotes the transformation of hedonic consumption from ‘potential demand’ to ‘effective demand’. For older farmers whose health level is lower than average, the income generated by land transfer forms a ‘pension-like’ effect, replacing the economic function of the traditional family pension [86], which enables this group to maintain basic survival consumption while at the same time allocating their marginal income to health and hedonic consumption.

4.4. Implications for Land Transfer Policy Reforms

The results of this study have important policy implications for rural land system reform.

Firstly, build a land transfer system with balanced rights and interests. The first goal is to establish a differentiated land transfer rights and interests protection mechanism, focusing on strengthening judicial remedies for the right to rent and income for outgoing older farmers, and improving the stability of business expectations for incoming older farmers. The second goal is to implement a ‘negative list + flexible term’ contract model by setting a list of land use restrictions and renewable terms to reduce the risk of ‘forced transfer’.

Secondly, develop an intergenerational agricultural service network. The first goal is to cultivate professional trusteeship consortia and ensure that trusteeship income is not lower than the level of self-management through standardised service processes and service quality tracking systems. The second goal is to develop a hybrid model of ‘land bank + professional manager’, so that older farmers can realise capitalised income from their land while retaining their contractual rights. The third is to establish a linkage mechanism between trusteeship services and pension insurance, and turn part of the trusteeship proceeds into pension savings, so as to alleviate the worries of consumption upgrading.

Thirdly, we are promoting the transformation of employment structures based on the ability to adapt. The first goal is to establish a non-farming skills reshaping centre for older farmers, and develop a ‘light physical strength—high technology’ job training programme for the health gradient. The second goal is to develop a courtyard economy and rural micro-industries, and enhance the inclusiveness of non-farming employment through the embedding of e-commerce platforms and the construction of local brands. The third is to innovate the ‘land-based pension’ replacement mechanism, allowing part of the proceeds from land transfer to be discounted against pension insurance contributions, so as to enhance the sustainability of the accumulation of consumption capacity.

Finally, improve the risk-buffering system infrastructure. The first goal is to the establishment of a land transfer risk compensation fund, natural disasters, and other force majeure events caused by the suspension of the contract to provide financial support. The second is to construct a land transfer disputes ‘administrative mediation—arbitration—litigation’ three-level settlement mechanism, to reduce the erosion of older farmers’ ability to consume due to cost.

It is suggested that future research could explore whether older farmers are more inclined to accept credit products or other financial services after land transfer, which could influence their consumption behaviour. For example, research could examine whether older farmers are able to increase their consumption levels through loan financing, especially in areas such as health and education.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

5.1. Conclusions

Land transfer is the foundation of the market-based reform of rural factors, and its resource allocation efficiency and welfare distribution effects not only concern sustainable rural development, but also directly address the dilemma of the smallholder economy and promote the long-term stability of sustainable livelihoods of older farmers. Based on the four-period panel data of the China Household Tracking Survey 2016–2022, this study explores the impact and mechanism of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers, revealing the following conclusions of general significance that can provide theoretical references for global rural reform and the international poverty reduction agenda.

First, land transfer significantly increases the consumption level and structure of older farmers through differentiated paths. The rent capitalisation effect of land transfer-out not only contributes to the growth of total consumption, but also extends the consumption structure towards healthy and more hedonistic consumption through risk appetite adjustment. Countries around the world, especially those facing the problem of ageing, can improve the consumption capacity of older people and, at the same time, guide the development of their consumption structure in the direction of healthier and higher quality. The ‘re-agriculturalisation’ effect of land transfer-in, despite structural constraints, is also globally applicable, especially in regions that are more dependent on agricultural resources, and has the same application in improving subsistence and healthy consumption. This finding suggests that a synergistic policy design that improves land exchange markets, strengthens property rights protection, and promotes complementary technologies is a universal path to activating rural consumption upgrading.

Second, land transfer-out significantly promotes the consumption of older farmers through the household income mechanism. The income mechanism of land transfer-out is to release consumption through the triple path of ‘rent stability—incremental non-farm income—preventive savings release’. Land transfer-in realises structural expansion of income through ‘economies of scale—technological dividends—asset premium’, which is a universal path to activating consumption upgrading in rural areas, especially for low- and middle-income households. Consumption promotion through land transfer-out relies on a change in the nature of income, while land transfer-in improves the quality of income; together, they constitute an institutional channel for older farmers to break out of the ‘low-income trap’.

Third, there is a dynamic synergy in the consumption effects of two-way land transfers. The transfer-out of fragmented land through the liquidity release effect for the transfer-in of continuous operation to provide capital accumulation, while the transfer-in of land scale gains through intergenerational transfer payments to feed the transfer-out of older farmers to upgrade consumption. This effect has the potential to be widely applied globally, especially in areas with limited or unevenly distributed land resources, to optimise land resource allocation and promote agricultural modernisation and sustained growth of the rural economy.

5.2. Limitations

Although this study systematically reveals the impact and mechanism of land transfer on the consumption behaviour of older farmers and provides a basis for policy optimisation, there are still some limitations. One limitation concerns the group boundary constraints of the research object. This study focuses on the group of older farmers, and although it can deeply analyse the special consumption response pattern in the context of ageing, it fails to include young and middle-aged farmers for comparative analysis.

Author Contributions

P.C.: Conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration; Q.J.: writing—review and editing, funding acquisition; Y.X.: conceptualisation, methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding