Abstract

This study quantitatively analyzed the spatial characteristics of 3425 historical and cultural resources across the Chungcheong region of South Korea and proposed strategies for regional revitalization. Each asset was evaluated on a five-point scale, and spatial patterns were examined using kernel density estimation (KDE), Moran’s I, and Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA). The results show that the historical and cultural resources in the Chungcheong region form significant clusters, particularly in areas such as Boryeong, Seosan, Gongju, and Buyeo, which were historically associated with administrative, Confucian, and Buddhist functions. A Moran’s I value of 0.272 was obtained, indicating statistically significant spatial autocorrelation, and the LISA analysis identified “high–high” clusters as key zones with concentrated high-value assets. This study also revealed mismatches between designated cultural properties and areas with high-value but unrecognized resources, emphasizing the need for more inclusive heritage policies. These findings suggest that historical resources should be understood not as isolated sites, but as interconnected cultural landscapes. This research supports the development of tailored, place-based urban regeneration strategies that leverage cultural heritage as a foundation for sustainable regional identity and growth.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Objectives

Local cities in South Korea are facing serious challenges, including population decline and the deterioration of historic downtown areas [1,2,3,4]. Due to the concentration of population in the Seoul metropolitan area, combined with low birth rates and rapid aging, many small- and medium-sized cities in the provinces are experiencing significant population loss, leading to the decline and depopulation of their downtown cores [3,5]. In addition, large-scale, uniform urban development projects, such as new town constructions and massive apartment complexes, have been carried out nationwide, resulting in the loss of unique local landscapes and identities—a phenomenon known as the “loss of place” [6,7]. As a result, the weakening of regional vitality due to population decline and the destruction of local identity due to indiscriminate development have emerged as critical urban issues in South Korea.

To address these problems, an urban regeneration approach based on regional characteristics and community values is required. “Place-based” bottom-up urban regeneration, which preserves and strengthens local distinctiveness rooted in the region’s history, culture, and residents’ lives, plays a crucial role in promoting social sustainability [8,9]. In particular, urban regeneration strategies that utilize historical and cultural resources have gained attention as they preserve and reinterpret a city’s identity and historical values, while also offering new economic and social vitality to the local community [10,11]. Heritage-led regeneration not only revitalizes local economies by promoting tourism and commercial activity but also positively impacts residents’ place attachment, social cohesion, and identity formation [10,11,12,13]. Furthermore, conserving and reusing existing historical and cultural resources contribute to environmental sustainability by reducing energy consumption and waste compared to new construction [14]. Therefore, urban regeneration centered on historical and cultural resources holds great significance as an integrated approach that simultaneously pursues economic, social, and environmental values [13,14,15].

Recognizing the importance of place-based urban regeneration, South Korea has undertaken institutional efforts. In 2014, the Korean government enacted the Act on Value Enhancement of HANOK and other Architectural Assets [16]. In 2024, the Framework Act on National Heritage was introduced, establishing a policy framework for the systematic identification and preservation of valuable historical and cultural resources nationwide [17]. This represented a new conservation paradigm encompassing not only nationally designated heritage sites but also locally significant modern and contemporary historical and cultural resources. Under this framework, local governments conducted basic surveys to catalog historical and cultural resources, including historic buildings and landscape features, and explored strategies for their preservation and utilization. This approach aligns with the long-standing tradition of urban heritage management seen in Europe and elsewhere [18].

However, despite the establishment of institutional foundations and data, the value of historical and cultural resources has not been fully realized in actual urban planning and regeneration projects, leading to a gap between policy and practice [19]. The underutilization of historical and cultural resource survey results undermines the effectiveness of the policy, highlighting the need for further research and policy improvements. Ultimately, how to analyze and integrate collected historical and cultural resource data into regional regeneration strategies remains a pressing issue, requiring in-depth study.

In response to this challenge, this study proposed a GIS-based methodology to quantitatively analyze the spatial distribution characteristics of historical and cultural resources. The objective was to apply kernel density estimation (KDE) and spatial autocorrelation analyses (Moran’s I and LISA) to historical and cultural resources distributed throughout the study area, identify patterns of spatial concentration and clustering, and derive implications for regional regeneration strategies based on the findings.

1.2. Overview of the Chungcheong Region in South Korea

The Chungcheong region, centrally situated in South Korea, comprises Chungcheongnam-do (South Chungcheong Province) and Chungcheongbuk-do (North Chungcheong Province) (Figure 1). Due to its strategic geographic location at the heart of the Korean Peninsula, the region serves as an essential transportation and administrative hub connecting the Seoul metropolitan area with other provincial regions. National expressways such as the Gyeongbu, Jungbu, and Honam Expressways intersect here, providing excellent accessibility to major metropolitan areas including Seoul, Busan, and Gwangju [20,21]. Chungcheongnam-do, characterized by a broad coastal region along the Yellow Sea, borders Gyeonggi-do to the north, Chungcheongbuk-do to the east, Jeollabuk-do to the south, and the Yellow Sea to the west. In contrast, Chungcheongbuk-do, South Korea’s only landlocked province, features mountainous terrain formed by the Noryeong and Sobaek mountain ranges and is bordered by Gyeonggi-do and Gangwon-do to the north, Gyeongsangbuk-do to the east, Jeollabuk-do to the south, and Chungcheongnam-do to the west [20,21].

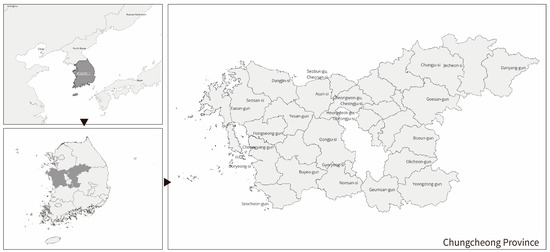

Figure 1.

Geographic location of Chungcheong Province, Korea.

Administratively, Chungcheongnam-do comprises eight cities (Cheonan, Gongju, Boryeong, Asan, Seosan, Nonsan, Gyeryong, and Dangjin) and seven counties (Geumsan, Buyeo, Seocheon, Cheongyang, Hongseong, Yesan, and Taean), while Chungcheongbuk-do includes three cities (Cheongju, Chungju, and Jecheon) and eight counties (Boeun, Okcheon, Yeongdong, Jeungpyeong, Jincheon, Goesan, Eumseong, and Danyang) (Figure 1) [20,21].

Historically significant, the Chungcheong region hosts a wealth of cultural heritage sites spanning from ancient Baekje cultural sites in Gongju and Buyeo, which include UNESCO World Heritage Sites such as Gongsanseong and Busosanseong Fortresses, to Confucian educational centers from the Joseon Dynasty and modern industrialized cities such as Cheongju and Daejeon. Cheongju, a central administrative hub during the Goryeo Dynasty, is internationally recognized for producing Jikji, the world’s oldest extant book printed with movable metal type [22]. Chungju, Jecheon, and Danyang preserve distinctive Buddhist and mountainous cultural heritages, including significant temples such as Beopjusa and Guinsa, historic houses, and Confucian academies. Additionally, Asan’s Oeam Folk Village maintains traditional noble residences from the Joseon Dynasty, and Cheongpung Cultural Heritage Complex protects historically significant buildings relocated due to dam constructions.

Despite this extensive cultural legacy, recent decades have brought significant demographic and economic challenges, such as population decline, aging, and weakening regional industries. The continued migration of younger populations to the Seoul metropolitan area, coupled with persistently low birth rates, has significantly reduced the working-age population. By 2021, Chungcheongbuk-do officially became an “aged society”, with over 20% of its population aged 65 or older; both Chungcheong provinces are now considered “super-aged” regions.

While the Chungcheong region possesses numerous high-quality heritage assets, including hanok (traditional Korean houses), modern and contemporary architecture, and traditional landscape districts, many non-designated historical and cultural resources remain underutilized and inadequately managed. Thus, there is an urgent need for systematic heritage management and the development of spatially integrated strategies to revitalize the region. Given its developmental disparities and uneven utilization of cultural assets, Chungcheong represents an ideal case for analyzing spatial distribution imbalances and exploring strategic intervention possibilities. Furthermore, the region’s alignment with national initiatives such as “Balanced National Development” and the “Mega-city Concept” heightens the practical relevance and applicability of research outcomes. Despite these strategic benefits, Chungcheong has received limited academic attention, underscoring its value as a case study for proposing innovative regional revitalization strategies through quantitative spatial analysis.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Historical and Cultural Resource Survey and Current Status

Research on urban regeneration utilizing cultural heritage and architectural assets has been conducted from various perspectives. Tweed and Sutherland (2007) examined the relationship between the preservation of architectural cultural heritage and urban regeneration through a literature review, emphasizing the potential synergy between the two fields [23]. Nocca (2017) proposed indicators for measuring the economic and social impacts of heritage projects and evaluated the multifaceted contribution of heritage to sustainable urban regeneration [14]. Doratli (2005) presented an evaluation model for determining optimal strategies for the regeneration of historic city centers and verified the effectiveness of different strategies by applying the model to a case study in Cyprus [24]. Additionally, Evans (2005) conducted a comparative analysis of several culture-led regeneration cases across cities to assess the social and economic impacts of cultural heritage utilization on regional revitalization [10].

In relation to this, there has been active research utilizing GIS and spatial statistical techniques to analyze the spatial characteristics and value of cultural heritage. Liu et al. (2024) analyzed the trends in GIS (geographic information system) application in the field of cultural heritage preservation, noting that its use has steadily increased since 2015 and has contributed to the establishment of sustainable preservation strategies, the development of proactive conservation models, and the enhancement of decision-making processes [25]. Shon et al. (2022) conducted a methodological study to extract candidate sites for deriving architectural assets, select sites linked to heritage properties, and propose the designation of Architectural Asset Value Enhancement (AAVE) zones [26]. Lfadaly et al. (2018) analyzed the spatial distribution of heritage sites in Egypt by classifying their distribution characteristics, applying the Getis–Ord and Hot Spot spatial analysis techniques, and using band combination methods to predict and detect environmental risks [27]. Fu and Mao (2024), Wang and Zhan (2022), and Li (2024) analyzed the spatial characteristics of cultural heritage and relic sites in China using GIS-based kernel density estimation and nearest neighbor analysis, presenting density patterns according to the geographical and historical characteristics [28,29,30]. Garcia-Martin et al. (2017) investigated local stakeholders’ perceptions of landscape value, utilizing a variety of statistical and GIS-based spatial analysis techniques to comprehensively analyze spatial patterns and their correlations with various contextual factors [31].

These studies demonstrate that GIS and spatial analysis tools provide a quantitative basis for the evaluation and preservation planning of cultural heritage, significantly contributing to the establishment of strategic urban regeneration initiatives.

2.2. National-Level Management and Preliminary Surveys of Historical and Cultural Resources

In recent years, social interest in the value of architectural heritage—such as traditional Korean houses (hanok) and modern and contemporary buildings—has significantly increased in South Korea. As rapid urban development leads to the destruction or disappearance of buildings with historical and cultural significance, demands for the preservation of architectural heritage have grown stronger [16]. In particular, hanok structures and buildings constructed during the Japanese colonial period and the early modern era hold critical value in terms of national identity and architectural history. However, under the former Cultural Heritage Protection Act system, only a limited number of these structures were designated as cultural properties, leaving most architectural heritage sites outside the scope of institutional protection. Modern and contemporary buildings that were not designated as cultural properties often faced the risk of damage or demolition, highlighting the need for a new legal framework to address these gaps.

Against this backdrop, the Act on Value Enhancement of HANOK and other Architectural Assets, Including Hanok was enacted and came into force in 2014. As South Korea’s first law specifically dedicated to architectural heritage, it established a legal foundation for the comprehensive conservation and promotion of hanok and other architectural assets [16]. The Act aims to preserve the cultural and historical values of architectural assets and improve the quality of living environments. It mandates the state and local governments to systematically survey, manage, and establish promotion plans for architectural assets [16]. The key provisions include the establishment of a Basic Plan for Architectural Assets, the creation of survey data and information systems, support for the maintenance and utilization of architectural assets such as hanok, and the development of specialized human resources [16].

The enactment of the Act on Value Enhancement of HANOK and other Architectural Assets marked significant progress by supplementing the limitations of the former Cultural Heritage Protection Act and providing an active protection mechanism that encompasses non-designated cultural properties. However, the national heritage protection framework underwent further substantial changes. On 17 May 2024, the heritage management system, which had been centered around the Cultural Heritage Protection Act for over 60 years, was reorganized under the new Framework Act on National Heritage [17]. This new legal framework replaces the term “cultural properties” with the expanded concept of “national heritage”, aiming to establish a more integrated and systematic approach to preservation, management, and utilization [17]. Under this legal foundation, local governments have been developing regional strategies for the conservation of architectural heritage based on the new legislation. These plans are increasingly being linked to urban regeneration projects, aiming to revitalize declining urban areas while simultaneously preserving historical landscapes.

The Framework Act on National Heritage classifies national heritage into three categories: cultural heritage, natural heritage, and intangible heritage. It also provides comprehensive legal protection for non-designated or non-registered heritage assets, such as local heritage assets. In this study, the term historical and cultural resources refers to non-designated and non-registered heritage assets managed by local governments, including local and future heritage assets.

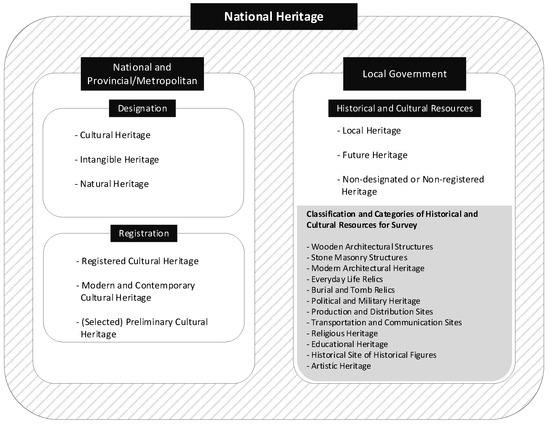

The term cultural properties are used to describe assets officially designated by the national or provincial governments, whereas cultural heritage refers more broadly to non-designated or non-registered heritage (Figure 2). Historical and cultural resources encompass both tangible and intangible elements that reflect the accumulated historical experiences and cultural practices of a specific region. These include wooden and stone structures, modern buildings, everyday life relics, burial sites, political and military sites, production and distribution facilities, transportation and communication infrastructure, religious heritage, educational institutions, heritage sites associated with historical figures, and artistic heritage.

Figure 2.

Concept and scope of historical and cultural resources [32].

2.3. Procedure for Selecting Historical and Cultural Resources

The research methodology involved three distinct phases for creating a comprehensive survey list of historical and cultural resources (Table 1). In the first phase (Step 1), 202 documents from national institutions, metropolitan governments, and key research bodies, including the Cultural Heritage Administration, the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, and local educational offices, were compiled. The research team reviewed and filtered these documents, removing non-relevant items such as buried cultural properties, natural and intangible heritage, duplicates, designated cultural assets, items without verifiable address information, and those with ambiguous scopes. The finalized initial list consisted of 16,149 items, of which 3425 pertained to the research area, and was subsequently uploaded to the survey system. The second phase (Step 2) commenced once field surveys had begun based on the initial list. Regional and category-specific researchers, together with the research support team, identified additional documents and materials that were previously not listed. These supplementary materials were sourced from regional museums, local governments, publications from regional researchers and institutes, and academic studies. The supplementary list included archaeological projects post-1996, important modern architectural works constructed before 1975, recently disclosed military installations, industrial facilities, and additional studies on local beliefs and modern lifestyles conducted after 1996. Burial sites from the Goryeo, Joseon, and modern periods were selectively included based on their historical and artistic significance. In the third phase (Step 3), the combined initial and supplementary lists were reviewed and distributed to local governments. The cultural heritage departments within these governments examined the lists for omissions and inaccuracies. Feedback from local governments was organized and reviewed by regional researchers to confirm compatibility with the research objectives, after approval, additions were uploaded to the survey system, completing the creation of the survey list.

Table 1.

Procedure for selecting historical and cultural resources [33].

The data collection standards used were developed and refined through consultation with the National Heritage Agency’s advisory committee, comprising field-specific experts. The standardized survey form included categories such as basic information, classification codes, detailed type information, historical significance, state of preservation, and researchers’ remarks. This survey form, traditionally designed for completion on paper, required structured and descriptive responses tailored to each category. Classification codes were systematically assigned based on region, usage, material, structure, nature, and religion, facilitating effective management and analysis. The data collection process was digitalized using tablet PCs integrated with GPS, allowing real-time on-site verification and comprehensive data input. All collected data underwent a rigorous approval workflow, involving stages of “Waiting”, “In Progress”, “Request Approval”, “Approved”, “Revision”, and either final “Approval” or “Rejection”, thereby ensuring data accuracy and professional reliability.

2.4. Field Investigations

The data collection for this research was conducted as part of a national project spanning five years [32]. The project was overseen by the Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea (formerly Cultural Properties Administration), with Korean Association for Architectural History and the Architecture and Urban Research Institute—a government-funded institution—serving as the principal and collaborative research organizations, respectively. To ensure consistency, continuity, and improvement through feedback, these research institutions remained involved throughout the five-year duration. In consultation with the supervisory agency, an advisory committee composed of specialists in various fields was established, and a dedicated research support team was formed to provide continuous administrative, financial, and logistical assistance. Each year, a principal investigator was selected from the Architectural History Association, prioritizing individuals with extensive regional experience and demonstrated leadership. Association members typically serve as university professors or researchers in national institutes. Based on their expertise, large-scale annual research teams were formed, composed of regional scholars, cultural heritage professionals, and graduate students in related disciplines. Over the five-year period, between 150 and 200 researchers conducted the field surveys under the direction of designated regional research leaders.

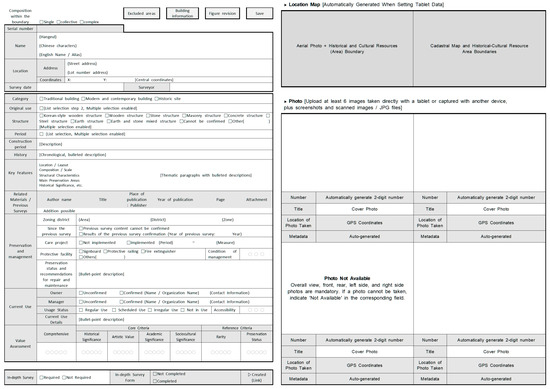

Once survey targets were selected, the lead investigator conducted training sessions for all participating researchers on field survey methods and value assessment criteria. The lead investigator also monitored the survey process to resolve potential issues and ensure accuracy. The national-level survey covered a wide range of data, encompassing spatial coordinates, names, addresses, surveyor identities, physical and managerial conditions, usage status, in-depth evaluation forms, and comprehensive value assessments, including historical, artistic, academic, social, rarity, preservation, and overall value categories (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Survey form (source: authors’ own elaboration) [34].

The comprehensive value assessment of historical and cultural resources was based primarily on four core criteria—historicity, artistic merit, academic relevance, and sociocultural value. Additionally, two reference criteria—rarity and preservation status—were taken into account to determine the final score. Notably, there is no fixed quantitative relationship between the main criteria and the final value rating. In some cases, high scores on the main criteria may be moderated by low scores on the reference criteria, resulting in an overall value score that is lower than expected. Historicity, artistic merit, and academic value are standard indicators used to evaluate designated or registered cultural properties and are assessed via comparison with existing examples listed in the national cultural heritage database maintained by the Cultural Heritage Administration. In contrast, sociocultural value—while not typically used in official evaluations for designation or registration—was included in this study to reflect the unique regional or cultural landscape significance of non-designated assets. This criterion also considers the potential for future contribution to local communities through preservation and adaptive reuse.

For this study, only spatial data and overall value scores were used for analysis. The value assessment was conducted using a 5-point Likert scale: a score of 1 indicated very low value, 3 moderate value, and 5 very high value. To address possible discrepancies in evaluation among research teams, all value assessment results were discussed and harmonized through collaborative review among investigators. This process was essential to ensure consistency, objectivity, and reliability in the final evaluations.

2.5. Research Methods

Based on the aforementioned historical and cultural resource investigation process and field survey methods, the finalized dataset includes spatial and attribute data for over 16,000 resources nationwide, of which 3425 are located in the Chungcheong region. For the purpose of this study, only spatial coordinates and overall value scores were ex-tracted and analyzed.

The spatial analysis was conducted using QGIS (ver. 3.28.), a widely adopted open-source geographic information system. Kernel density estimation (KDE) was applied to visualize the spatial distribution of historical and cultural resources and to identify areas of concentration. Additionally, a density overlay analysis was carried out to examine the spatial relationship between the distribution of historical and cultural resources and that of officially designated cultural heritage sites.

To further enhance spatial understanding; spatial autocorrelation analysis was performed using GeoDa(ver. 1.22) software. In this analysis; each resource’s value assessment score was applied as a weighting factor. Global Moran’s I was used to detect overall spatial clustering trends; while Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) were employed to identify statistically significant local clusters.

To examine the spatial distribution and density of historical and cultural resources, as well as that of designated and registered cultural properties at the national and local levels within the Chungcheong region, a GIS-based kernel density estimation (KDE) technique was applied.

KDE is an analytical method that visually represents the density of point data within a spatial area. In this study, the following formula was utilized [35,36]:

where is the estimated density at location (x, y), is the total number of analyzed points, is the bandwidth (radius), is the kernel function, and represents the distance between location (x, y) and point .

In the next stage of the analysis, administrative divisions (eup, myeon, and dong levels) were set as the basic units of analysis to identify the statistical spatial patterns of historical and cultural resources within the Chungcheong region.

Global Moran’s I and Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) analyses were performed based on the average value scores and the number of historical and cultural resources per administrative unit.

Moran’s I is effective in evaluating the overall spatial autocorrelation of a region and confirming the spatial clustering tendencies of resource values. It is mathematically expressed as follows [37]:

where is the number of spatial units; and are the observed values at spatial units i and j, respectively; represents the spatial weight matrix indicating the connectivity between units; and is the sum of all spatial weights.

Although kernel density estimation, Moran’s I, and LISA represent commonly applied spatial analysis methods, this study is distinguished by its approach to extracting regional characteristics through comparison of resource density with designated heritage sites, as well as through identification of spatial clustering trends based on value assessment scores.

Based on the results, this study derived tailored regional regeneration strategies. These strategies emphasize the potential of high-value historical and cultural clusters as focal points for sustainable urban development, cultural tourism, and community revitalization. By anchoring regeneration efforts on spatially significant cultural resources, this approach aims to enhance local identity, promote regional equity, and support the long-term viability of heritage-informed urban planning.

3. GIS-Based Analysis

3.1. Overview of the Basic Survey of Historical and Cultural Resources

The survey of historical and cultural resources in Chungcheong-do was conducted over a five-year period from 2020 to 2024 under the supervision of the National Heritage Administration of Korea, which oversees the management of the country’s historical and cultural resources. The survey in Chungcheong-do, the study area, was carried out specifically between 2022 and 2023. The purpose of the survey was to obtain foundational data for establishing policies aimed at the comprehensive preservation, management, and utilization of historical and cultural resources, with the ultimate goal of ensuring the sustainable inheritance of regional identity through the systematic management and active utilization of resources that had previously been marginalized.

The scope of the survey was broadly defined to include spaces, buildings, and natural environments that possess historical and cultural significance and contribute to shaping regional identity. Within the framework of the Cultural Heritage Protection Act, the survey excluded already designated or registered cultural properties and focused primarily on above-ground remains. Regarding the selection criteria, the survey targeted assets that had been formed up to 1975. However, modern architectural assets constructed after 1975 but deemed to have significant preservation value were included after consultation with the National Heritage Administration. Priority was given to structures exposed above ground that were considered highly vulnerable to damage or loss.

In terms of methodology, a standardized survey form was used to collect data, supplemented by drawings, photographs, and additional notes. The survey form consisted of 17 items, including name, type classification, address, land use zoning, owner, manager, construction period and historical era, area, historical background, major features, related materials, type-specific information, current usage status, potential value, conservation status, investigator’s opinion, and survey date and investigator.

To ensure accuracy, different types of historical and cultural resources were recorded according to the specific formats appropriate for each type.

A total of 3425 historical and cultural resources were surveyed across the Chungcheong region, categorized by type as follows:

- Traditional structures accounted for the largest share, with 1767 cases;

- Archaeological sites came in second, with 1295 cases;

- Modern and contemporary buildings were recorded as 336 cases;

- Other categories totaled 27 cases.

This distribution suggests that the historical and cultural resources in the Chungcheong region are heavily concentrated in traditional and indigenous heritage, underscoring the need for conservation and utilization strategies for these assets.

Regarding distribution by administrative district, Boryeong-si had the highest number of resources, with 379 cases, followed by Geumsan-gun (287 cases), Chungju-si (262 cases), Okcheon-gun (241 cases), Boeun-gun (185 cases), Danyang-gun (169 cases), Gongju-si and Asan-si (each with 167 cases), and Seosan-si (149 cases).

These areas account for a significant proportion of the region’s historical and cultural resources and should be prioritized as key hubs for future urban regeneration and cultural tourism development strategies. When classified by usage and function, the largest category was commemorative resources, totaling 1377 cases, followed by religious resources (1318 cases) and funerary resources (488 cases). These three categories together accounted for over 90% of all resources. Other categories included military sites (39 cases), residential buildings (35 cases), transportation infrastructure (25 cases), telecommunication infrastructure (19 cases), industrial facilities (18 cases), educational institutions (9 cases), governmental buildings (5 cases), cultural and assembly spaces (4 cases), hydraulic structures (3 cases), and accommodation facilities (1 case). There were also 84 cases classified as mixed types or others.

This distribution indicates that the historical and cultural resources in the Chungcheong region are predominantly centered on religious, commemorative, and funerary themes, highlighting the need for strategic planning that takes these characteristics into account when developing future cultural heritage management and regional cultural policies.

3.2. Distribution of Buildings in Chungcheong Region

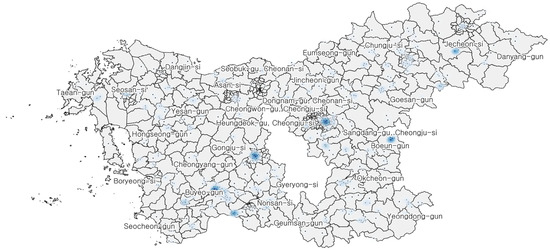

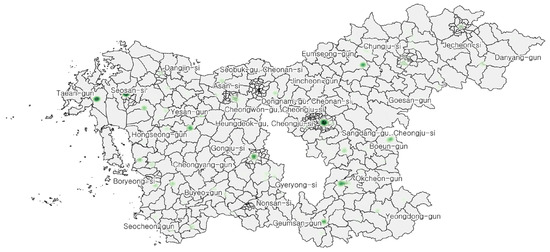

Based on the above analysis, two separate heatmaps were generated: one for historical and cultural resources and another for cultural properties. These heatmaps were subsequently overlaid to visually identify areas where high-density overlaps occurred and areas where they did not. This enabled a clear spatial analysis of the relationship between historical and cultural resources and designated cultural properties.

For the Chungcheong region, a total of 3425 historical and cultural resources and cultural properties (both designated and registered) were analyzed. The KDE function within QGIS was utilized for the analysis, with a bandwidth (search radius) set at 3000 m and a resolution of 100 pixels.

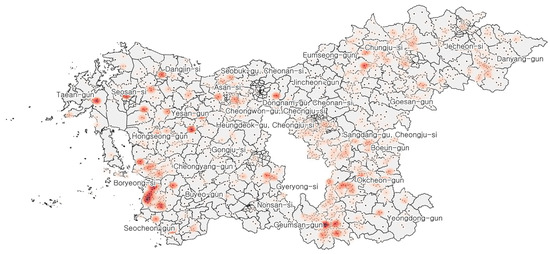

The results of the kernel density heatmaps are as follows:

- The heatmap for historical and cultural resources (displayed in red) indicates relatively high densities in Boryeong-si, Taean-gun, Buyeo-gun, Yesan-gun, and Seosan-si in Chungcheongnam-do, as well as in Geumsan-gun, Eumseong-gun, and Chungju-si in Chungcheongbuk-do, particularly in the West Coast area (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Heatmap of Chungcheong Province’s historical and cultural resources.

Figure 4. Heatmap of Chungcheong Province’s historical and cultural resources. - The heatmap for cultural properties (displayed in blue) shows high concentrations in historically significant areas such as Buyeo-gun and Gongju-si in Chungcheongnam-do, and Cheongju-si and Boeun-gun in Chungcheongbuk-do, where major temples are located (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Heatmap of Chungcheong Province’s Cultural Heritage.

Figure 5. Heatmap of Chungcheong Province’s Cultural Heritage.

The overlaid heatmap (displayed in green) reveals that areas with high density in both datasets correspond largely to regions with a dense distribution of cultural properties. However, there are also areas with a large number of historical and cultural resources that are not adjacent to designated cultural properties (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Overlapping area of Chungcheong Province’s historical and cultural resources and cultural properties.

This finding suggests that such areas should be prioritized for further investigation into potentially expanding their cultural property registration and for the development of preservation and utilization stmrategies.

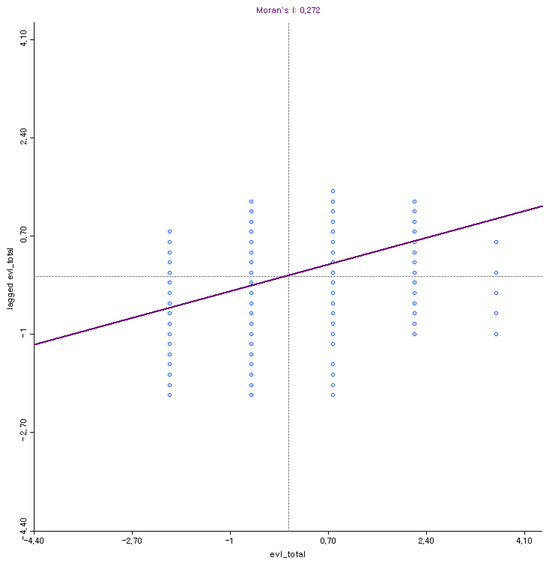

3.3. Spatial Autocorrelation of Historical and Cultural Resources

This study conducted both global spatial autocorrelation analysis (Moran’s I) and local spatial autocorrelation analysis (LISA) to examine the spatial distribution characteristics and clustering tendencies of historical and cultural resources in the Chungcheong region. The goal was to identify spatial clusters and heterogeneities and to provide a foundational reference for future spatial policy development.

The calculated Moran’s I value is 0.272, indicating a weak-to-moderate positive spatial autocorrelation (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Moran’s I results.

Although the Moran’s I value is not extremely high, it suggests that high-value and low-value assets each form localized spatial clusters, rather than being randomly distributed. Particularly, the scatter plot shows a concentration of observations in the high–high and low–low quadrants, allowing for the identification of clusters that may require policy intervention.

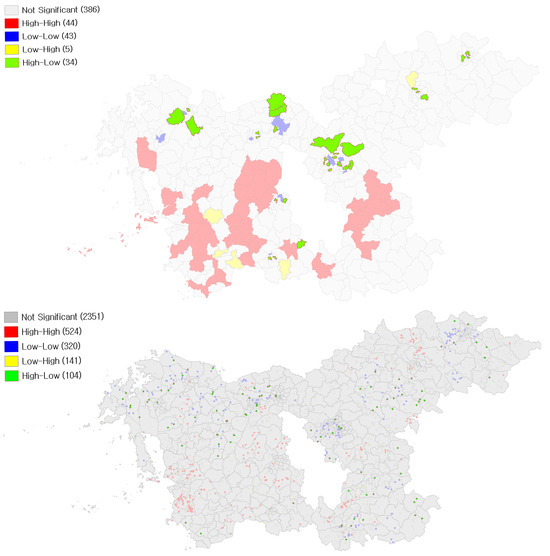

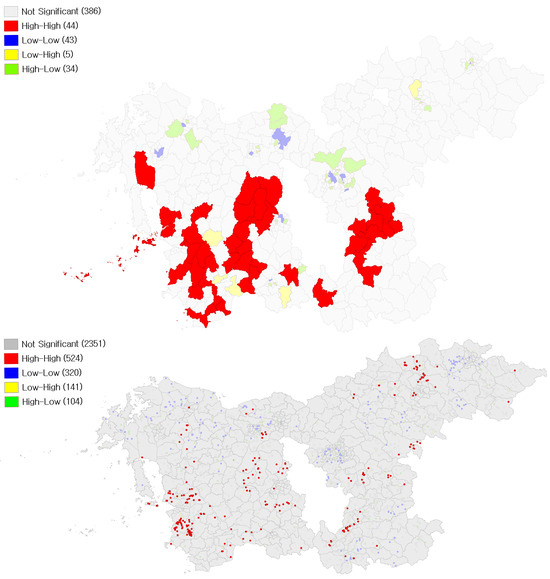

Following the global analysis, LISA was used to generate cluster maps based on both administrative units and point data. This enabled the identification of significant local clusters (e.g., high–high, low–low) from a localized spatial perspective (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

High–high spatial cluster map.

The high–high cluster map (areas in red) was used to identify administrative divisions where high-value resources are surrounded by other high-value resources, forming high-density clusters. Notably, Boryeong, Seosan, Gongju, Nonsan, Buyeo, and parts of Seocheon-gun in Chungcheongnam-do, along with Boeun-gun and Okcheon-gun in Chungcheongbuk-do, were identified as major high-density areas. These regions show high potential as strategic hubs for future regional regeneration efforts (Figure 8).

The high-low cluster map (areas in green) was used to identify administrative units where high-value resources are surrounded by relatively low-value resources. Differences were observed between point-based and administrative-unit-based analyses (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

High–low (HL) spatial cluster map.

This pattern indicates dispersed high-value assets that may require targeted, node-based revitalization strategies. In other words, these isolated high-value sites have the potential to grow into cultural centers, but they currently exhibit a weak spatial linkage with surrounding areas.

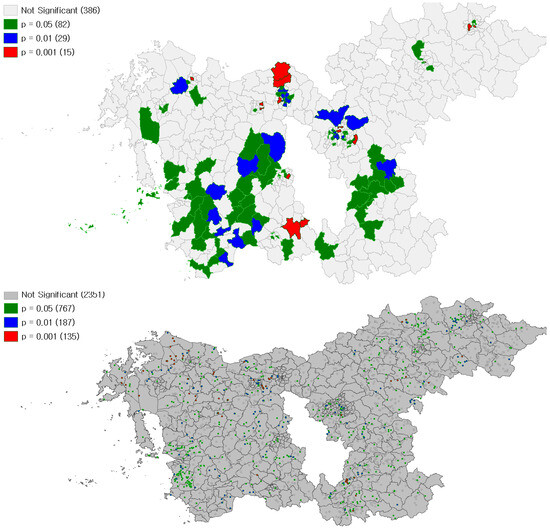

The LISA significance map visualizes the statistical significance (p-values) of the spatial patterns across administrative units (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

LISA significance map.

The analysis revealed that approximately 17.2% of the administrative divisions exhibited spatial autocorrelation at a significance level of p < 0.05. Among them, 15 regions met the 99.9% confidence level (p < 0.001), indicating the strong statistical reliability of the observed spatial patterns.

This result strengthens the validity of the LISA cluster interpretation and suggests that the findings can serve as a robust foundation for the formulation of spatial policies.

Based on point data, the LISA significance analysis showed that approximately 32% of all historical and cultural resource points (1089 locations) exhibited significant spatial autocorrelation at p < 0.05, with 135 points reaching the highest confidence level of 99.9% (p < 0.001).

These findings suggest that these sites have strong spatial interactions with neighboring resources, highlighting them as key focal areas for future cultural hub development or heritage conservation prioritization.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of Analysis of Historical and Cultural Resources in the Chungcheong Region

First, the historical and cultural resources in the Chungcheong region do not exhibit a random spatial distribution but rather form significant clusters. Areas such as Boryeong, Seosan, Gongju, Buyeo, Boeun, and Okcheon were identified as core regions of such clusters. These areas historically served as key administrative centers during the Joseon dynasty and earlier periods. They also functioned as focal points for Confucian institutions, such as seowon (Confucian academies) and hyanggyo (local Confucian schools), and were rich in Buddhist cultural heritage dating back to the ancient and Goryeo periods. The prevalence of educational and religious facilities among the clustered resources suggests a strong correlation between historical function and current spatial patterns.

Second, the overlay analysis comparing designated cultural properties with non-designated historical and cultural resources revealed regional imbalances. Some areas exhibit high densities of valuable resources but have relatively few officially designated properties. This indicates that many locally significant assets remain outside institutional protection, calling for a reassessment of equity and inclusiveness in cultural heritage designation systems. If such resources continue to be overlooked or undervalued, the risk of their destruction increases, ultimately leading to the fragmentation of cultural landscapes and erosion of local identity. Therefore, an expansion of designation criteria and improved procedural access is urgently needed to bridge the gap between actual resource distribution and formal recognition.

Third, the spatial autocorrelation analysis yielded a Moran’s I value of 0.272, suggesting that the historical and cultural resources in the region exhibit non-random spatial distribution with notable spatial concentration and interrelatedness. This implies that these resources are not isolated but interconnected within a shared cultural and historical context, thereby necessitating an integrated approach to heritage management at the regional scale. The spatial structure reflects residual patterns from past administrative, religious, and cultural systems, indicating the enduring influence of historical networks.

Fourth, LISA analysis identified statistically significant local clusters of historical and cultural resources. Specifically, areas such as Boryeong, Seosan, Gongju, Nonsan, Buyeo, Seocheon, Boeun, and Okcheon were classified as “high–high” clusters, where high-value resources are concentrated in proximity. These findings suggest that such areas possess strong potential to function as core zones for strategic, heritage-led urban regeneration. Conversely, the “high–low” clusters—where high-value resources are isolated from other high-value assets—highlight the need for node-based connectivity strategies to enhance network centrality and accessibility. These insights support the formulation of differentiated management strategies based on the spatial relationships of resources.

Fifth, spatial statistical analysis showed that approximately 17.2% of the administrative units in the Chungcheong region exhibit statistically significant spatial autocorrelation (p < 0.05), indicating that the distribution of resources in these areas is characterized by spatial concentration and interconnection rather than randomness. Furthermore, 1089 individual resources—accounting for about 32% of the total—were found to form statistically significant spatial relationships at the point level, suggesting that many resources are part of larger spatial clusters shaped by historical and cultural contexts.

In conclusion, this study found that the historical and cultural resources in the Chungcheong region are not randomly dispersed but form meaningful clusters with strong spatial interconnectivity. These clusters function not merely as isolated heritage sites, but also as components of a broader cultural landscape structured by historical and cultural networks. The identification of high–high clusters in historically important administrative and cultural centers—such as Boryeong, Seosan, Gongju, and Buyeo—underscores their potential as strategic hubs for urban regeneration. Meanwhile, the imbalance between designated and non-designated assets highlights the need for more inclusive heritage policies, and the presence of isolated high-value resources calls for network-based connectivity strategies. Finally, the finding that 32% of all resources demonstrate spatial significance supports a paradigm shift from treating heritage assets as individual objects to managing them as interconnected systems, forming the foundation for sustainable regional development through integrated, place-based strategies.

4.2. Regional Revitalization Strategies Focused on Activation

Regions identified as high–high clusters—such as Boryeong, Seosan, Gongju, Nonsan, Buyeo, Seocheon in Chungcheongnam-do, and Boeun and Okcheon in Chungcheongbuk-do—should be prioritized as heritage-based regeneration hubs.

By integrating the conservation of historical and cultural resources into urban regeneration projects, these areas can strengthen their regional identities while fostering sustainable social and economic revitalization. Strategic initiatives may include the establishment of heritage-themed cultural zones, the promotion of cultural tourism based on local narratives, and the development of creative industries leveraging traditional assets.

In high–low cluster areas, where individual high-value resources are dispersed and isolated, a node-based activation strategy is recommended.

This approach involves enhancing the visibility, accessibility, and utilization of these isolated heritage assets through thematic linking and targeted investment. By positioning high-value nodes as local cultural centers, these areas can stimulate surrounding communities and create broader ripple effects for regional development.

For areas with a dense distribution of historical and cultural resources but a low concentration of officially designated cultural properties, proactive efforts are needed to expand cultural property designation.

Identifying and registering currently non-designated yet valuable resources will strengthen the region’s cultural asset base and provide a foundation for more comprehensive preservation and utilization initiatives.

This strategic expansion will also enhance eligibility for national and international cultural heritage support programs.

Urban regeneration strategies should integrate heritage conservation into broader sustainable urban development frameworks.

Rather than treating conservation as a separate or secondary objective, it should be embedded within urban planning processes, emphasizing adaptive reuse, environmentally friendly development, and the creation of culturally sensitive spaces.

Such an integrated approach can contribute to achieving both heritage preservation and revitalization of declining urban and rural areas.

Areas with dense clusters of high-value historical and cultural resources (e.g., Boryeong, Buyeo, Gongju) should develop integrated cultural tourism initiatives.

Strategies may include the creation of heritage trails, thematic tour courses, and cultural festivals that link multiple heritage sites, creating experiential tourism products that stimulate visitor inflows and local spending.

By branding regions around their unique historical identities (e.g., Baekje cultural route, Buddhist heritage route), local economies can be revitalized through increased tourism demand.

Regions with strong but underutilized historical resources should foster creative industries linked to cultural assets.

This may include supporting startups in heritage interpretation, cultural content development (e.g., AR/VR heritage experiences), traditional crafts, and local storytelling businesses.

By encouraging young entrepreneurs and creative professionals to settle and work in these areas, sustainable economic bases can be expanded beyond traditional tourism.

To ensure sustainable revitalization, community participation must be strengthened.

Programs that train local residents as cultural interpreters (docents), heritage managers, and tourism operators should be developed.

Additionally, participatory heritage management initiatives (e.g., community-led restoration projects, shared heritage gardens) can foster a sense of ownership and pride, making revitalization efforts more resilient and locally rooted.

Activation strategies should move beyond isolated site conservation toward integrated spatial planning.

This would involve creating cultural corridors that connect heritage sites with daily community functions (e.g., markets, cafes, galleries), as well as improving pedestrian accessibility, public transportation links, and public spaces around heritage zones.

Through spatial integration, heritage can be naturally embedded into the everyday life of residents, reinforcing both economic activity and cultural identity.

5. Conclusions

This study quantitatively examined the spatial distribution and clustering characteristics of 3425 historical and cultural resources across the Chungcheong region of South Korea, employing GIS-based methods including kernel density estimation (KDE), Moran’s I, and Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA). The analysis confirmed that these resources are not randomly distributed but form significant spatial clusters, particularly in historically important administrative and cultural centers such as Boryeong, Seosan, Gongju, and Buyeo. Moreover, the study revealed a substantial gap between actual resource value and formal designation status, emphasizing the need for more inclusive cultural heritage policies and spatially tailored regeneration strategies.

However, this study focused solely on the Chungcheong region, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other contexts. Additionally, the physical condition, accessibility, and community engagement levels of each resource were not assessed, which may affect their real-world applicability. Future research should incorporate diverse value assessment results—including cultural, historical, social, and economic dimensions—to conduct more detailed and nuanced regional analyses. Such work would enable a multidimensional understanding of heritage significance and allow for more targeted planning interventions at the local level.

The findings of this study offer practical implications for multiple stakeholders. Local governments are urged to prioritize high–high clusters as regeneration hubs and close the gap in designation processes. Cultural and planning institutions should adopt integrated approaches to embed heritage assets into sustainable urban and regional development strategies. Community actors should be encouraged to participate in heritage activation to ensure resilient and inclusive revitalization. Ultimately, this study reaffirms the scientific and practical value of spatial heritage analysis and contributes to a growing paradigm that sees cultural resources as foundational assets for sustainable, place-based development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, D.S. and B.K.; software, formal analysis, and data curation, B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.; writing—review and editing, B.K.; visualization and supervision, B.K.; funding acquisition, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding for academic research programs from Chungbuk National University in 2024.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors with each individual’s consent, wish to express their gratitude to the four anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which have been very helpful in improving the paper. We would also like to thank the National Heritage Administration of Korea and the Architecture and Urban Research Institute (AURI) for their cooperation in providing the historical and cultural resource data utilized in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, S. Are small cities disappearing? The policy responses to urban shrinkage oriented toward young people in Uiseong-gun, South Korea. Cities 2024, 155, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.W.; Bae, C.-H.C.; Choe, S.C. Shrinking cities in South Korea. In Shrinking Cities: A Global Perspective; Richardson, H.W., Bae, C.-H.C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-Y.; Yoon, C.-J. Typology of small- to medium-sized Korean local cities with population decline from the perspective of urban compactness. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Suh, K. A new index to assess vulnerability to regional shrinkage (hollowing out) due to the changing age structure and population density. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Li, M.; Jung, J. Response to shrinking cities: Cultural urban regeneration. Cities 2024, 155, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, K. Modern Architecture: A Critical History, 5th ed.; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J. Cultural quarters as mechanisms for urban regeneration. Plan. Pract. Res. 2004, 19, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, M.; Pitt, M. The characters of place in urban design. Urban Des. Int. 2014, 19, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.; Sykes, H.; Granger, R. (Eds.) Urban Regeneration, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. Measure for measure: Evaluating the evidence of culture’s contribution to regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 959–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardi, G.; Amirtahmasebi, R. (Eds.) The Economics of Uniqueness: Investing in Historic City Cores and Cultural Heritage Assets for Sustainable Development; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-D. Event and sustainable culture-led regeneration: Lessons from the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture: Urban Future—Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nocca, F. The role of cultural heritage in sustainable development: Multidimensional impact evaluation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Paddison, R. Introduction: The rise and rise of culture-led urban regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Assembly of the Republic of Korea. Act on Value Enhancement of HANOK and other Architectural Assets (Act No. 16057). Available online: https://law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=Act+on+Value+Enhancement+of+HANOK+and+other+Architectural+Assets+&x=0&y=0#liBgcolor0 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- National Assembly of the Republic of Korea. Framework Act on National Heritage (Act No. 20309). Available online: https://law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=Act+on+National+Heritage+&x=25&y=29#liBgcolor3 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Pickard, R. Funding the Architectural Heritage: A Guide to Policies and Examples; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Park, I.; Son, E.; Lee, K. Current status and improvement direction of the construction asset promotion system. AURI Brief 2022, 247. Available online: https://www.auri.re.kr/publication/view.es?mid=a10313000000&publication_type=brief&publication_id=1826 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Chungnam Province. Available online: https://www.chungnam.go.kr/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Chungbuk Province. Available online: https://www.chungbuk.go.kr/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- UNESCO. JIKJI. Available online: https://www.unescoicdh.org/home/sub.php?menukey=272&mod=view&no=17855&page=2&search=4&scode=00000004&listCnt=10&code1=00000003&code2=00000032 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doratli, N. Revitalizing historic urban quarters: A model for determining the most relevant strategic approach. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2005, 13, 749–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, C.; Xu, W.; Shen, Y.; Tang, F. Emerging trends in GIS application on cultural heritage conservation: A review. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, D.; Kim, S.; Byun, N. Derivation method of architectural asset value enhancement zones in South Korea. Land 2022, 11, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifadaly, A.; Attia, W.; Qelichi, M.M.; Murgante, B.; Lasaponara, R. Management of cultural heritage sites using remote sensing indices and spatial analysis techniques. Surv. Geophys. 2018, 39, 1347–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Mao, H. Study on the spatiotemporal distribution patterns and influencing factors of cultural heritage: A case study of Fujian Province. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhan, S. Exploring the spatial distribution of ICH by Geographic Information System (GIS). Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 8689113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Determination of the temporal–spatial distribution patterns of ancient heritage sites in China and their influencing factors via GIS. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Martin, M.; Fagerholm, N.; Bieling, C.; Gounaridis, D.; Kizos, T.; Printsmann, A.; Müller, M.; Lieskovský, J.; Plieninger, T. Participatory mapping of landscape values in a Pan-European perspective. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 2133–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Official Website of the Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Republic of Korea; Available online: https://www.cha.go.kr (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Cultural Heritage Report 2023; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Heritage Administration. A Comprehensive Survey and Management Plan for Historical and Cultural Resources 2020; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, D.; Unwin, D.J. Geographic Information Analysis, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).