Revisiting the Contested Case of Belgrade Waterfront Transformation: From Unethical Urban Governance to Landscape Degradation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

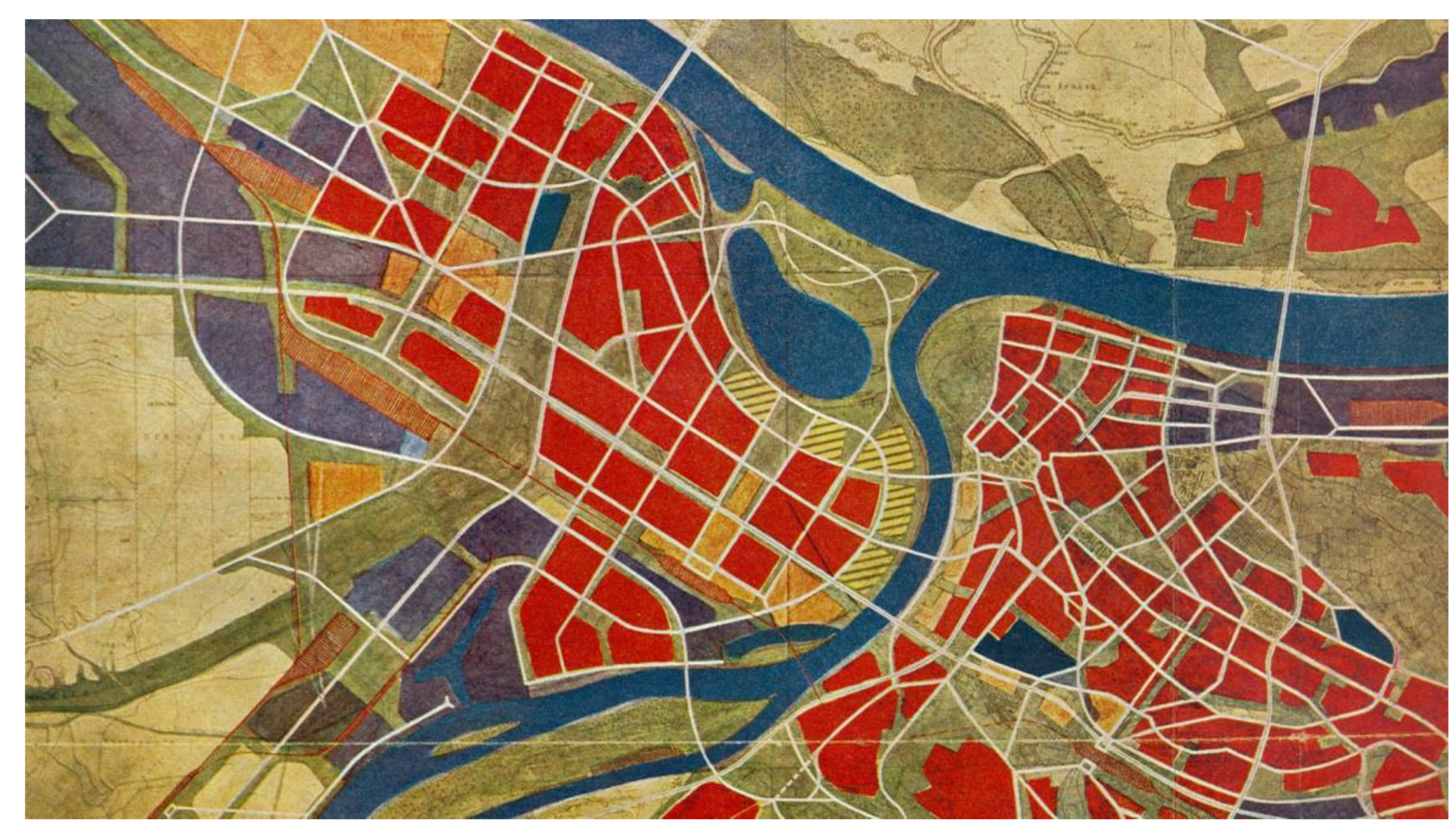

2.1. Historical Background and Spatial Context of the Belgrade Waterfront

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Methodological Framework

- How did a decade-long, capital-centric urban development policy pursued by Belgrade’s city administration succeed in the radical transformation of a precious part of the old town fabric into privatised urban land by enabling large-scale investors to gain privileged access to constructing the business district and exclusive housing, while enhancing existing power asymmetries and inequalities within the city’s population?

- How did the unethical nature of urban land management decisions in the case of the BWP lead to the perpetual loss of meaning of the fabric of the old town along the River Sava for already socially disadvantaged Belgradians by their indirect exclusion from the new city district due to its scarce public spaces?

- How can the notion of urban landscape be used for understanding socio-spatial problems and recognising their concrete consequences for the urban and natural environment?

- How can the experiences of urban landscape transformation from previous epochs be utilised as a repository of knowledge and understanding of spatial and social relations?

- What achievements of socialist socio-spatial development can be utilised for future models of architectural and urban theory and practice as specific innovative impulses?

- Recognition of the relation between unethical features in urban governance and the degradation of the urban landscape in the post-socialist period in Belgrade;

- Insight into alternative architectural and urban models through examination of corresponding socialist socio-spatial development;

- Searching for and specification of the relevant socio-spatial criteria aimed at increasing disciplinary and interdisciplinary knowledge to establish more egalitarian socio-spatial practises.

3. Results

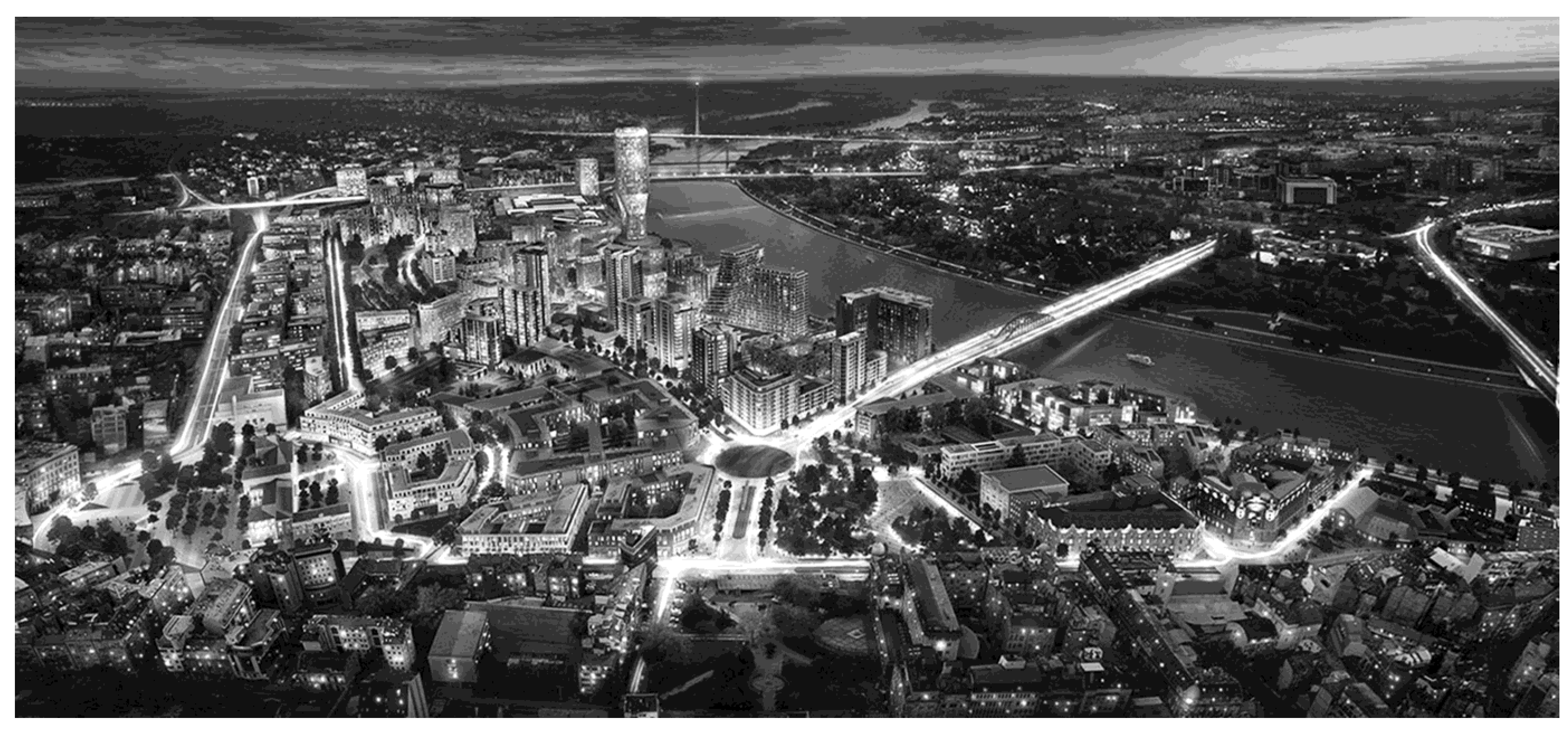

3.1. Belgrade Waterfront Project

3.1.1. The Elusive Process of Urban Megaproject Inception

3.1.2. The Master Plan of Belgrade 2021 (2016)

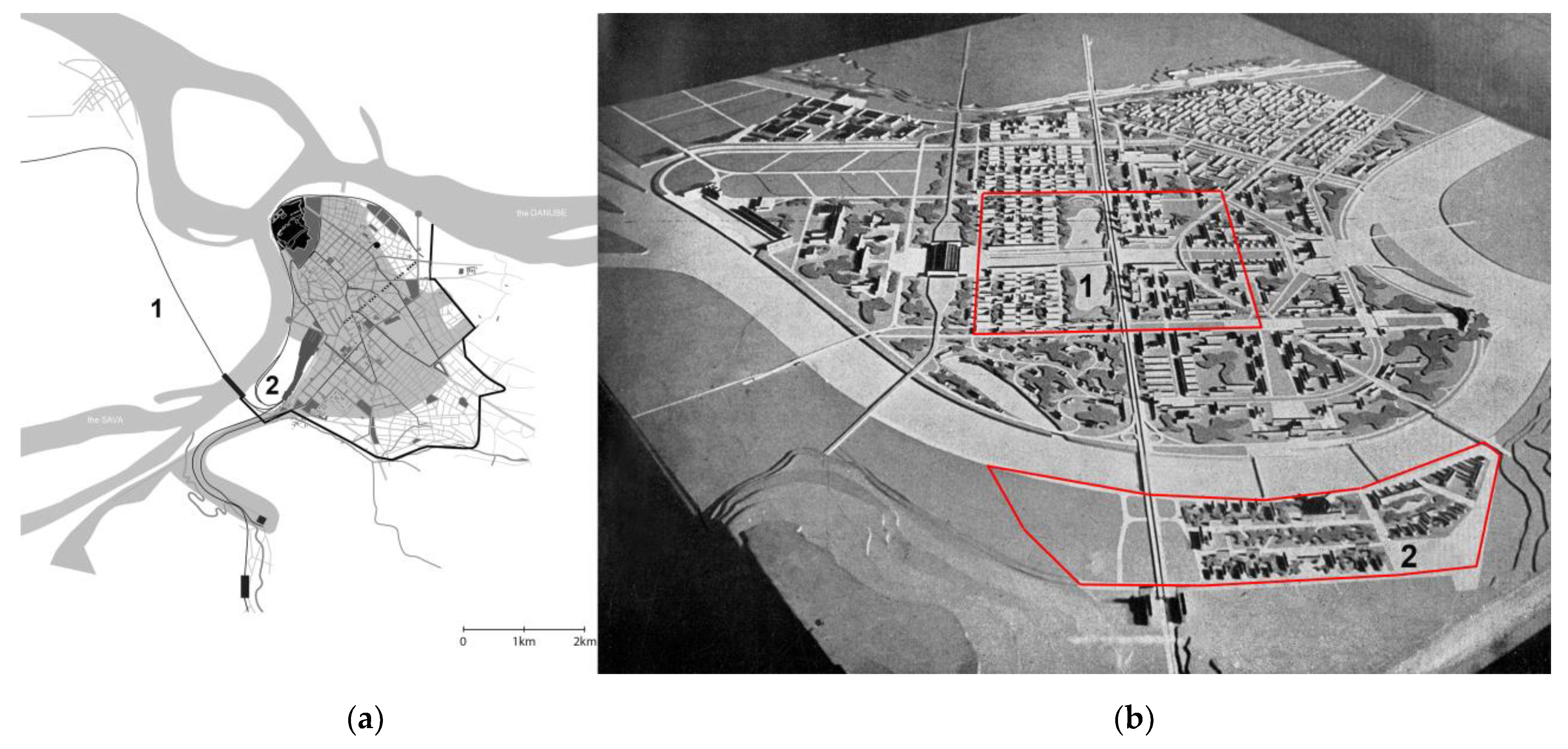

3.2. Searching for Alternative Practises

The Case of New Belgrade and Its Central Zone

4. Discussion

4.1. Recognition of Post-Socialist Paradigm

4.2. Learning from Socialist Paradigm

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BWP | Belgrade Waterfront Project |

| BW | Belgrade Waterfront |

| EHC | Eagle Hill Company |

| BWCI | Belgrade Waterfront Capital Investment LLC |

| CZNBg | Central Zone of New Belgrade |

References

- Hoggett, P. A Service to the Public: The Containment of Ethical and Moral Conflicts by Public Bureaucracies. In The Values of Bureaucracy; du Gay, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrade Waterfront, Eagle Hills, Essential Principles. 2016. Available online: https://www.belgradewaterfront.com/en/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Popović, M. Stari Beograd-segment Savske varoši (Lociran u zoni planske razrade projekta-Beograd na Savi) [Old Belgrade-the Segment of Savska Varoš (Located within the Zone of Planned Development Defined by the Project Entitled Belgrade on the Sava)]. Nasleđe 1997, 1, 33–37. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Vuksanović-Macura, Z. Bara Venecija i Savamala: železnica i grad [Bara Venecija and Savamala: The Railway and the City]. Nasleđe 2015, 16, 9–26. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrović, N.; Marković, V. Železnički Problem Beograda [The Railroad Problem of Belgrade]; Urbanistički institut NRS: Belgrade, Serbia, 1946. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Zečević, V. Govor ministra građevina FNRJ Vlade Zečevića na svečanosti prilikom otvorenja radova na izgradnji Novog Beograda [Speech by the FPRY Minister of Construction Vlado Zečević at a Ceremony During the Opening of the Works on the Construction of New Belgrade]. Arhitektura 1948, 2, 7–12. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Karamata, K. Transformacija staroga Beograda [The Transformation of the Old Belgrade]. Arhit. Urban. 1966, 7, 39–47. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Đorđević, A. Razvoj Beograda i aktuelni urbanistički problemi [Development of Belgrade and Current Urban Planning Problems]. Arhit. Urban. 1966, 7, 4–11. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Ćorović, D. Beograd kao Evropski Grad u Devetnaestom Veku: Transformacija Urbanog Pejzaža [Belgrade as a European City in the Nineteenth Century: Urban Landscape Transformation]. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Architecture, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2015. (In Serbian). [Google Scholar]

- Perović, M.R. Iskustva Prošlosti/Lessons of the Past; Zavod za planiranje razvoja grada Beograda: Belgrade, Serbia, 1983; bilingual edition Serbian-English. [Google Scholar]

- Perović, M.R.; Stojanović, B. With Man in Mind: Royal Institute of British Architects, London: An Exhibition of Two Projects from the City Planning Institute; Gradski Zavod za Planiranje: Belgrade, Serbia; Kulturni centar Beograd: Belgrade, Serbia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Perović, M.R. Središte Kulture III Milenijum u Beogradu [III Millennium Centre of Culture in Belgrade]; Gradski zavod za planiranje: Belgrade, Serbia, 1989. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Vukmirovic, M. Urban Plans and the Transformation of Belgrade Through History. In Belgrade; The Urban Book Series; Arandelovic, B., Vukmirovic, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kadijević, A.Đ.; Kovačević, B.S. Degradative urbanistic and architectural aspects of the project “Belgrade Waterfront” (2012–2016). Matica Srp. J. Fine Arts 2016, 44, 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade. Generalni Urbanistički Plan Beograda 2021 (GUP BGD 2021) [The Master Plan of Belgrade 2021]. Službeni List Grada Beograda. 7 March 2016. Available online: https://www.beoland.com/en/plans/master-plan-of-belgrade.html (accessed on 13 March 2025). (In Serbian).

- Odluka o Izradi Izmena i Dopuna Prostornog Plana Područja Posebne Namene Uređenja Dela Priobalja Grada Beograda [Decision on the Development of Amendments to the Spatial Plan for the Special Purpose Area for the Development of the Coastal Part of the City of Belgrade]. Službeni Glasnik RS, 11 April 2024, p. 31. Available online: https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/odluka/2024/31/2/reg (accessed on 28 September 2024). (In Serbian).

- Strategija Razvoja Grada Beograda [City of Belgrade Development Strategy]. Službeni List Grada Beograda, 61, 30 June 2017. Available online: https://www.sllistbeograd.rs/pdf/2017/47-2017.pdf#view=Fit&page=1 (accessed on 30 January 2025). (In Serbian).

- Primedba na Izmene i Dopune Prostornog Plana Posebne Namene za Beograd na Vodi [New Planning Practice. Comment on the Amendments to the Special Purpose Spatial Plan for Belgrade on the Water]. 13 July 2024. Available online: https://novaplanskapraksa.com/ppppn-bgdnavodi-izmene/ (accessed on 28 September 2024). (In Serbian).

- Pierre, J. The Politics of Urban Governance; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Erkkilä, T.P.O. Politics and Numbers: The Iron Cage of Governance Indices. In Ethics and Integrity in Public Administration: Concepts and Cases; Cox, R.W., III, Ed.; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, M.D. Good Governance. In Encyclopedia of Governance-First Volume; Bevir, M., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 359–362. [Google Scholar]

- Venice Commission. Stocktaking on the Notions of ‘Good Governance’ and ‘Good Administration’. 2011. Available online: https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2011)009-e (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Barrett, B.F.D.; Horne, R.; Fien, J. Ethical Cities; Routledge: Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bozeman, B. Public Values and Public Interest: Counterbalancing Economic Individualism; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McHarg, A. Reconciling Human Rights and the Public Interest: Conceptual Problems and Doctrinal Uncertainty in the Jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights. Mod. Law Rev. 1999, 62, 671–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denhardt, J.V.; Denhardt, R.B. The New Public Service: Serving, Not Steering; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wildavsky, A. What Is Permissible So That This People May Survive?: Joseph the Administrator. PS Political Sci. Politics 1989, 22, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Geuras, D. Common Ground, Common Future: Moral Agency in Public Administration, Professions, and Citizenship; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, M.S. Making Ethical Decisions; Josephson Institute of Ethics: Los Angeles, LA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C.W.; Gilman, S.C. The Ethics Challenge in Public Service; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M. Public Administration Ethics for the 21st Century; ABC Clio: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, M. Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Berque, A. Thinking Through Landscape; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, J. (Ed.) Recovering Landscape, Essays in Landscape Architecture; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.E. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape; The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.B. Discovering the Vernacular Landscape; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape. In University of California Publications in Geography; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1925; Volume 2, pp. 19–53. [Google Scholar]

- Stilgoe, J.R. Landschaft and Linearity: Two Archetypes of Landscape. Environ. Rev. 1980, 4, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, J. Landscape; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Milinković, M.; Ćorović, D.; Vuksanović-Macura, Z. Historical Enquiry as a Critical Method in Urban Riverscape Revisions: The Case of Belgrade’s Confluence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, J. Terra Fluxus. In The Landscape Urbanism Reader; Waldheim, C., Ed.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Postmodern Geographies, Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Spaces; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Basta, C.; Moroni, S. (Eds.) Ethics, Design and Planning of the Build Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, H. Belgrade Waterfront: An Unlikely Place for Gulf Petrodollars to Settle. The Guardian, 10 December 2015. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/dec/10/belgrade-waterfront-gulf-petrodollars-exclusive-waterside-development (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Zeković, S.; Maričić, T.; Vujošević, M. Megaprojects as an Instrument of Urban Planning and Development: Example of Belgrade Waterfront Project, Cooperation & Development Center Codev, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne EPFL 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325797400_Megaprojects_as_an_Instrument_of_Urban_Planning_and_Development_Example_of_Belgrade_Waterfront (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- The Academy of Architecture of Serbia (AAS). Deklaracija: O “Beogradu na vodi” [The Declaration: On “Belgrade Waterfront”]. 5 March 2015. Available online: http://aas.org.rs/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Deklaracija-AAS-o-Beogradu-na-vodi-05.-mart-2015.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025). (In Serbian).

- The Academy of Architecture of Serbia (AAS). Deklaracija br. 3 [The Declaration No.3]. 6 April 2016. Available online: http://aas.org.rs/deklaracija-broj-3/ (accessed on 14 February 2025). (In Serbian).

- Bojović, B. Diletantizam kao urbanizam–Beograd na vodi [Dilettantism as urbanism-Belgrade Waterfront]. Izgradnja 2014, 68, 167–168. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The International Network for Urban Research and Action (INURA) Open Letter to the People of Belgrade. 1 August 2014. Available online: https://pescanik.net/open-letter-to-the-people-of-belgrade/ (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Slavković, L. Belgrade Waterfront: An Investor’s Vision of National Significance. Failed Architecture 2015. Available online: https://www.failedarchitecture.com/belgrade-waterfront/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Cukic, I.; Sekulic, D.; Slavkovic, L.; Vilenica, A. Report from Belgrade Waterfront. Eurozine 2015. Available online: https://www.eurozine.com/report-from-belgrade-waterfront/?pdf (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Vilenica, A.; Džokić, A.; Neelan, M. Contemporary housing activism in Serbia: Provisional mapping. Interface A J. About Soc. Mov. 2017, 9, 424–447. Available online: http://www.interfacejournal.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Interface-9-1-Vilenica.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Republički Geodetski Zavod: Najskuplji Kvadratni Metar Stana u Srbiji Prodat u Beogradu na Vodi za 11.811 Evra [The Republic Geodetic Authority: The Most Expensive Square Meter Apartment in Serbia Sold in Belgrade Waterfront for 11,811 Euros] Forbes. 2025. Available online: https://forbes.n1info.rs/novac/rgz-najskuplji-kvadratni-metar-stana-u-srbiji-prodat-u-beogradu-na-vodi-za-11-811-evra/ (accessed on 23 February 2025). (In Serbian).

- Cvetinovic, M.; Nedovic-Budic, Z.; Bolay, J.-C. Decoding urban development dynamics through actor-network methodological approach. Geoforum 2017, 82, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelemaij, J.; Janković, S. Behind the Frontline of the Belgrade Waterfront: A Reconstruction of the Early Implementation Phase of a Transnational Real Estate Development Project. In Experiencing Postsocialist Capitalism: Urban Changes and Challenges in Serbia; Petrović, J., Backović, V., Eds.; University of Belgrade-Faculty of Philosophy: Belgrade, Serbia, 2022; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Peric, A. Public engagement under authoritarian entrepreneurialism: The Belgrade Waterfront project. Urban Res. Pract. 2020, 13, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeković, S.; Maričić, T. Contemporary Governance of Urban Mega-Projects: A Case Study of the Belgrade Waterfront. Territ. Politics Gov. 2022, 10, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čamprag, N. Effects and Consequences of Authoritarian Urbanism: Large-Scale Waterfront Redevelopments in Belgrade, Zagreb, and Novi Sad. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 7589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, K. Šta znamo o megaprojektima u Srbiji [What We Know About Mega-Projects in Serbia]. Kritika 2024, 5, 211–227. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, A.; Maruna, M. Post-socialist Discourse of Urban Megaproject Development: From City on the Water to Belgrade Waterfront. Cities 2022, 130, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T. Urban Geography; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, I. Space in the age of non-place. In Deleuze and Space; Buchanan, I., Lambert, G., Eds.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2005; pp. 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrade Waterfront Serbia. Potpisan Ugovor o Zajedničkom Ulaganju u Projekat Beograd na Vodi Između Vlade Srbije i Eagle Hillsa [The Agreement on Joint Venture for the Belgrade Waterfront Project Signed Between the Serbian Government and Eagle Hills]. 26 April 2015. Available online: https://www.belgradewaterfront.com/vesti/potpisan-ugovor-o-zajednickom-ulaganju-u-projekat-beograd-na-vodi-izmedju-vlade-srbije-i-eagle-hillsa/ (accessed on 6 March 2025). (In Serbian).

- Bovaird, T.; Löffler, E. Understanding public management and governance. In Public Management and Governance; Bovaird, T., Löffler, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rescher, N. Fairness: Theory and Practice of Distributive Justice; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2002. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Republic Agency for Spatial Planning (RASP) Prostorni Plan Područja Posebne Namene Uređenja dela Priobalja Grada Beograda–Područje Priobalja Reke Save za Projekat “Beograd na Vodi” [The Special Purpose Area Spatial Plan–for the Part of the Belgrade Riverfront for the Project “Belgrade Waterfront”]. June 2014–January 2015. Available online: https://www.urbel.com/srl/biblioteka-planova/2952/detaljnije/w/0/prostorni-plana-podrucja-posebne-namene-uredjenja-dela-priobalja-grada-beograda-podrucje-priobalja-reke-save-za-projekat-beograd-na-vodi/ (accessed on 25 February 2025). (In Serbian).

- Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU), Department of Fine Arts and Music, The Working Group of the Initial Committee for Architecture and Urban Planning. Primedbe i Sugestije na Nacrt Prostornog Plana Područja Posebne Namene Uređenja Dela Priobalja Grada Beograda [Comments and Suggestions on the Draft of the Special Purpose Area Spatial Plan, for the Part of the Belgrade Riverfront]. 28 October 2014. Available online: http://aas.org.rs/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Savski-amfiteatar-komplet-28.-10.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024). (In Serbian).

- The Republic Agency for Spatial Planning (RASP). Prestanak Rada Republičke Agencije za Prostorno Planiranje [Closing of the Republic Agency for Spatial Planning]. 17 December 2014. Available online: https://www.apps.org.rs/2014/12/prestala-sa-radom-republicka-agencija-za-prostorno-planiranje/ (accessed on 16 January 2025). (In Serbian).

- Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade. Generalni Urbanistički Plan Beograda 2021 (GUP BGD 2021) [The Master Plan of Belgrade 2021]. Službeni List Grada Beograda, 15 October 2003. Available online: http://nastava.sf.bg.ac.rs/pluginfile.php/11248/mod_resource/content/0/ZAKONI_I_PRAVILNICI/GUP_BGD.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2025). (In Serbian).

- Demir, T. Professionalism, Responsiveness, and Representation: What do They Mean for City Managers? Int. J. Public Adm. 2011, 34, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgrade Waterfront. A New Chapter in the History of Belgrade. 2025. Available online: https://cityexpert.rs/a/en/new-build-homes/belgrade/savski-venac/belgrade-waterfront (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- E-kapija. Study of High-Rise Buildings of Belgrade Adopted. 30 December 2010. Available online: https://www.ekapija.com/website/en/page/383005/Study-of-high-rise-buildings-of-Belgrade-adopted (accessed on 21 March 2025). (In Serbian).

- Jugoslavija 1918–1988. Statistički Godišnjak [Yugoslavia 1918–1988. Statistical Yearbook]; Savezni zavod za statistiku: Belgrade, Serbia, 1989. (In Serbian)

- Vujnović, R.O. O kompleksnoj stambenoj izgradnji [About Complex Residential Construction]. Izgrad. Spec. Issue Stan Stanov. [Appartment Dwell.] 1973, 27, 3–7. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Mrkšić, D. Srednji Slojevi u Jugoslaviji [The Middle Classes in Yugoslavia]; Istraživačko-izdavački centar SSO Srbije: Belgrade, Serbia, 1987. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Ćorović, D.; Milinković, M.; Vasiljević, N.; Tilinger, D.; Mitrović, S.; Vuksanović-Macura, Z. Investigating Spatial Criteria for the Urban Landscape Assessment of Mass Housing Heritage: The Case of the Central Zone of New Belgrade. Land 2024, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrović, N. Obnova i Izgradnja Beograda. Konture Budućeg Grada [Reconstruction and Construction of Belgrade. Contours of the Future City]; Urbanistički Institut NRS: Belgrade, Serbia, 1946. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Blagojević, L. Novi Beograd, Osporeni Modernizam [New Belgrade, Contested Modernism]; Zavod za udžbenike/Arhitektonski fakultet Univerziteta u Beogradu/Zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture grada Beograda: Belgrade, Serbia, 2007. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Kulić, V.; Mrduljaš, M.; Thaler, W. Modernism in-Between: The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia; Jovis Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Glavički, M. Detaljni urbanistički plan mesne zajednice u bloku 28–jedna faza razrade idejnog urbanističkog rešenja Centralne Zone Novog Beograda [Detailed Urban Plan of the Local Community in Block 28-One Phase of the Development of the Conceptual Urban Solution of the Central Zone of New Belgrade]. Arhit. Urban. 1966, 7, 82–87. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade. Istorijat, Generalni Plan Beograda 1950 [History, General Plan of Belgrade. 1950]. 2025. Available online: https://www.urbel.com/srl/zavod/istorijat/ (accessed on 12 January 2025). (In Serbian).

- Đokić, A. Nove šanse Novog Beograda [New chances for New Belgrade]. Arhit. Urban. 1968, 9, 25–32. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Blagojević, L. The residence as a decisive factor: Modern housing in the central zone of New Belgrade. Archit. Urban. 2012, 46, 228–249. [Google Scholar]

- Mecanov, D. Urbanističko nasleđe–Blok 28 na Novom Beogradu [Urban Heritage-Block 28 in New Belgrade]. Nasleđe 2019, 20, 89–111. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keković, A. Stambeni blok 30 u Novom Beogradu [Apartment block 30 in New Belgrade]. Arhit. Urban. 1979, 82, 5–7. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović, J. Mass Heritage of New Belgrade: Housing Laboratory and So Much More. Period. Polytech. Archit. 2017, 48, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinović, U. Analiza i definisanje projektnog programa za mesnu zajednicu Bloka 30 u Novom Beogradu [Analysis and definition of the project program for the local community of Block 30 in New Belgrade]. In Detaljni Urbanistički Plan Mesne Zajednice Blok 30 na Teritoriji Opštine Novi Beograd [Detailed Urban Plan of the Local Community Block 30 in the Territory of the Municipality of Novi Beograd]; Institut za Arhitekturu i Urbanizam: Belgrade, Serbia, 1967; pp. 5–38. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Milinković, M.; Tilinger, D.; Jovanović, J.; Ćorović, D.; Krklješ, M.; Nedučin, D.; Dukanac, D.; Subić, S. (Middle Class) Mass Housing in Serbia Within and Beyond the Shifting Frames of Socialist Modernisation. In European Middle-Class Mass Housing: Past and Present of the Modern Community, Working Group 1 MCMH ATLAS, COST Action CA 18137-European Middle Class Mass Housing; Lima Rodrigues, I., Tsiambaos, K., Korobar, V., Eds.; Iscte-IUL (Instituto Universitário de Lisboa): Lisbon, Portugal, 2023; pp. 490–497. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrović, N. Terazijska Terasa: Jedan Savremeni Problem Prestonice [Terazije Terrace: One Contemporary Problem of the Capital City]. Vreme 26 February 1932. (In Serbian)

- Minić, O. Beograd danas [Belgrade Today]. Arhit. Urban. 1966, 7, 3. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- N1info. Koliko Košta Beograd na Vodi [How Much Does Belgrade Waterfront Cost]. 2022. Available online: https://n1info.rs/biznis/koliko-kosta-beograd-na-vodi/ (accessed on 21 November 2024). (In Serbian).

- Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Kula Belgrade. Available online: https://www.som.com/projects/kula-belgrade/ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Vuolteenaho, J.; Basik, S. Mobilities of toponymic place branding in an autocratic post-Soviet city: The Mayak Minska (the Lighthouse of Minsk) and the Minsk-Mir (the Minsk-World) megaprojects. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2022, 65, 459–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. “Minsk Mir”–Priglašjenije v Mašinu Vriemieni! Kak Novyj Kompleks na Našich Glazach Mieniajet Obraz Bielorusskoj Stolicy [“Minsk Mir”—A Sign into a Time Machine! How the New Complex Changes the Image of the Belarusian Capital in Our Eyes]. Komsomól’skaja Právda, 30 March 2020. Available online: https://www.kp.ru/daily/27110/4187105/ (accessed on 12 April 2024). (In Serbian).

- Kuletskaya, D. The “Legitimized Architecture” of Minsk World: Primitive Accumulation Through Housing Under Authoritarian Neoliberalism in Belarus. Archit. Theory Rev. 2022, 26, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, A. Dissipating the Political: Battersea Power Station and the Temporal Aesthetics of Development. Open Cult. Stud. 2018, 2, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battersea Power Station, Masterplan. Available online: https://batterseapowerstation.co.uk/about/building-battersea-the-masterplan/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Warwick, H. Cathedral of Power: Battersea Power Station in Dystopian Visual Culture. Crit. Q. 2023, 64, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Moulaert, F.; Rodriguez, A. Neoliberal Urbanization in Europe: Large–Scale Urban Development Projects and the New Urban Policy. Antipode 2002, 34, 542–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, D. The Architecture of Neoliberalism: How Contemporary Architecture Became an Instrument of Control and Compliance; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dukanac, D.; Milinković, M.; Bnin Binski, A. Calibrating the parallax view: Understanding the critical moments of Yugoslav post-socialist turn. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Cannibal Capitalism. How Our System is Devouring Democracy, Care, and the Planet and What We Can Do About It; Verso: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrović, N. Što je gradski pejsaž? Njegova uloga i prednost u suvremenom urbanizmu [What is urban landscape: Its role and advantage in contemporary urban studies]. Covjek. Prost. 1954, 20, 1–3. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Milenković, A. Aktuelne teme prostornog planiranja [Current Topics of Spatial Planning]. Urban. Beogr. 1981, 8, 84–89. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Perić, A.; Blagojević, M. Passive agents or genuine facilitators of citizen participation? The role of urban planners under the Yugoslav self-management socialism. In Urban Planning During Socialism: Views from the Periphery; Mariotti, J., Leetimaa, K., Eds.; Rutledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Radović, R. Od kritike modernog urbanizma do sopstvene radne filozofije i prakse ljudskih naselja naše sredine [From Criticism of Modern Urbanism to Our Own Work Philosophy and Practice of Human Settlements in Our Environment]. Urban. Beogr. 1981, 8, 40–43. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Planerski atlas o razvoju Beograda na izložbama u Dablinu i Parizu [Planning Atlas on the Development of Belgrade at Exhibitions in Dublin and Paris]. Urban. Beogr. 1981, 8, 51–52. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, S. Antropologija Novobeogradskih Blokova: Urbano Stanovanje, Stvaranje Društvenih Prostora i Novi Život Prostornih Zajedničkih Dobara [Anthropology of New Belgrade Blocks: Urban Dwelling, Creation of Social Spaces and the New Life of Urban Commons]. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2023. (In Serbian). [Google Scholar]

- Murawski, M. Actually-Existing Success: Economics, Aesthetics, and the Specificity of (Still-)Socialist Urbanism. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 2018, 60, 907–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, J.; Leetimaa, K. (Eds.) Urban Planning During Socialism: Views from the Periphery; Rutledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Urban Process Under Capitalism: A Framework for Analysis. In The Urbanisation of Capital, Studies in the History and Theory of Capitalist Urbanisation 2; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1985; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Who Owns Our Cities-and Why This Urban Takeover Should Concern Us All. The Guardian, 24 November 2015. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/nov/24/who-owns-our-cities-and-why-this-urban-takeover-should-concern-us-all (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Lefebvre, H. The Right to the City. In Writings on Cities; Korman, E., Lebas, E., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 147–159. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ćorović, D.; Korać, S.T.; Milinković, M. Revisiting the Contested Case of Belgrade Waterfront Transformation: From Unethical Urban Governance to Landscape Degradation. Land 2025, 14, 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050988

Ćorović D, Korać ST, Milinković M. Revisiting the Contested Case of Belgrade Waterfront Transformation: From Unethical Urban Governance to Landscape Degradation. Land. 2025; 14(5):988. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050988

Chicago/Turabian StyleĆorović, Dragana, Srđan T. Korać, and Marija Milinković. 2025. "Revisiting the Contested Case of Belgrade Waterfront Transformation: From Unethical Urban Governance to Landscape Degradation" Land 14, no. 5: 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050988

APA StyleĆorović, D., Korać, S. T., & Milinković, M. (2025). Revisiting the Contested Case of Belgrade Waterfront Transformation: From Unethical Urban Governance to Landscape Degradation. Land, 14(5), 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050988