Abstract

The time is nigh to organize the physical landscapes of the United States under a unified land use policy and planning framework. As human populations have steadily grown, so has the urgency for agencies to plan for land uses at broader scales to overcome continued jurisdictional fragmentation and achieve sustainable and environmentally just landscapes. This paper introduces a vision, conceptual approach, and implementation strategy that applies ecoregions and proposes a unified framework for land use planning and regulation in the United States. The Sustainable Ecoregion Program (SEP) is designed to enable local landowners; public stakeholders; other land users; and state, regional, tribal, and national natural resource professionals to set and achieve future desired conditions for sustainable land uses across landscapes. The objective is to outline a comprehensive and sustainably just solution to the recurring problem of managing conflicting land uses in the face of continued degradation and multiple land tenure systems. The SEP will determine how much of the physical landscape will go to developed, agricultural, and natural landcover types. The framework includes recognition of level III ecoregions as primary boundaries, proposed secondary boundaries and shapes to enhance connectivity and movement across landscapes, a proposed structure for the environmental governance and co-management of landscapes, and definitions of physical landscape types. The benefits and challenges of the SEP are discussed. The outcomes of the SEP include ecological integrity, sustainable land use management, deliberative democracy, just sustainability, and improved quality of life for residents of the United States.

1. Introduction

“The national government has not and does not practice what would constitute national land use planning as that term is commonly understood in the United States and abroad”[1] (p. 446)

“Land use planning and regulation should be one of several mechanisms we can use as we struggle to learn and embrace what is good and right”[2] (p. 9)

Why is there no national, comprehensive land use policy or land use planning framework for the United States? There are many reasons why the United States lacks such a policy, including colonial, constitutional, historical, cultural, and economic traditions and factors [1,3]. Looking at the history of the nation and its progenitors before independence, we are reminded that the 13 colonies had governing institutions in place before there was a central government. There were many small and large farms in operation and production before the United States’ constitution was ratified. The colonial farmers and early frontier settlers had established land use practices and traditions that predated the national government. Before the arrival of settlers, the continent’s indigenous peoples had done the same but in different ways. Land uses have shifted overtime as the continent moved from indigenous stewardship to settler colonial stewardship. For example, during indigenous land stewardship, fire was used as a management tool throughout the United States, and the harvesting and sharing of wild bison (Bison bison) were cultural practices necessary for food security. This land use regime later shifted to fire exclusion, timber management, and domestic cattle production under the management of the settlers. As they colonized, many forms of indigenous land uses were displaced, and the frequency of natural fires on the landscape was interrupted. There is no blank canvas on which to begin, although there is a rich and sorted history, both oral and written, of land use predating the United States’ federal government. Natural history in the United States has a standpoint perhaps best described by ecoregions.

Today, there are substantial, and some will argue insurmountable, legal precedents, political lobbies, and value-driven barriers to developing and implementing a centralized national system of land use planning and management to include private lands and urban developments. Private land use rights in the United States are culturally and legally enshrined [4]. Approximately 60 percent of the land base of the United States is privately owned, and over 60 percent of those private lands are farms, ranches, and forests [1,5]. Private lands and American Indian reservations in the United States hold substantial amounts of economic, social, and ecological value and must be factored into all land use models and plans (both current and future) that are designed for sustainability and human well-being. On the other hand, private land tenure poses an obvious challenge to centralized land use planning and policy. Private property rights and tenure probably are one of the most important reasons why past efforts at regional, multi-state land use planning and regulations failed in the twentieth century.

The reasons for the lack of a national policy framework for land use include the nation’s propensity toward private market and private land ideologies, preferences and values for local control over higher-level controls [6], and the geographical scope of the continental United States, not to mention the combined area of Alaska, Hawaii, and other dispersed U.S. territories. One rationale for having no national land use policy is the sheer size of the country; perhaps the nation is too large with too much variability to centralize land use planning within the federal government [1]. However, we suggest the nation’s size and ecological and social diversity are assets, not hindrances, to improved land use management and societal well-being.

In the late 1930s and again in the early 1970s, there were efforts to establish national-level policies for land use planning and management. The first attempt grew out of President Roosevelt’s New Deal-era Agricultural Adjustment Administration and was designed to alleviate rural poverty among the nation’s farmers [3,7]. The Secretary of Agriculture reorganized the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 1938 to bring order to Roosevelt’s farming programs [7]. The new approach included county-level planning for agricultural land uses. Counties are local land-based governments within the states, and this agricultural planning initiative formed a vast network of thousands of community- and county-level planning committees throughout the rural United States, “designed to serve as conduits of data and policy-making from the grassroots to the USDA, and then back to the grassroots” [3] (p. 75).

Local farmers, working with extension agents and scientists from state and federal agencies and the land grant colleges, created countywide maps of agricultural land uses. The experts did not lead the process; however, the experts supported the process and advised the local planning committees as they made decisions and maps based on local farming knowledge, experience, and needs [7]. As the process, discussions, and planning unfolded among the local committees, desired changes to land uses were incorporated into revised county maps, and the USDA checked all its proposed actions against the county maps. No federal funds were provided for any agricultural land uses that were not consistent with the county land use maps.

Despite imperfect representation on the local committees and disconnects between farmers’ knowledge and technical and scientific expertise, this federal-county agricultural planning system mobilized thousands of rural peoples and government experts into a large-scale participatory and collaborative planning effort [7]. At one point during the program, 2200 counties had organized planning committees. The system was on track to harmonize local interests with national interests, achieve land use and economic benefits, and improve agricultural policies. Then, internal opposition and global geopolitics intervened [3,7]. After substantial political support for the new program, the American Farm Bureau Federation began to lobby congress against its continued funding in an attempt to reclaim local control from the community and county planning committees. The program ceased in 1942 with the onset of World War II. Farming in the United States became highly profitable during the war, without a need to plan for or change land management practices; the rural poverty crisis for the nation’s farmers ended, and with it so did the drive to reform land use planning and policy in rural America [3].

In the early 1970s, the inspiration for national-level land use planning began in the legislative branch of the federal government, not with the president, as certain politicians and lawmakers joined the march of environmentalism sweeping the nation [3]. The context for national land use planning and policy had changed: “National planning in the 1930s … centered on farmlands and the experiences of farm people. National planning in the 1970s, however, was a response to rapid urban growth and the disappearance of open space; it centered on urban land and the experiences of urban people” [3] (p. 77). In 1970, Senator Henry Jackson proposed Senate Bill S. 3354, a largely procedural National Land Use Policy Bill, to establish order in responding to a multitude of environmental conflicts coming before his chairmanship of the Senate Interior Committee [3].

The proposed Senate Bill S. 3354 of 1970 largely focused on data collection and agency coordination, with federal funds going to the states to classify lands and write state land use plans designed to direct land use decisions by the states [8]. Federal allocations of funds for land management would have been determined according to the states’ published plans, with little to no substantive protections prescribed for the environment. President Nixon and Senator Muskie, respectively, joined Jackson’s proposal, adding requirements of environmental reviews; carefully planned land developments (Mr. Nixon); and more rigorous environmental protections for wetlands, flood plains, and important agricultural lands (Mr. Muskie). Congress was not convinced that adding teeth to what was once a procedural bill would have been politically viable; therefore, they failed to pass the bill and all of the iterations of the bill congress deliberated during 1971 to 1974. The revised bill never reached the president’s desk for signature [3].

Land use planning and regulation in the United States remain generally decentralized and locally based, and continue to favor local, and sometimes state, jurisdictions while avoiding national land use regulations outside of publicly owned lands [1,3,6,9]. Despite its history, realistic challenges, and political inertia, the United States should seriously revisit a national land use policy and broad planning framework implemented through a mix of top-down national policy and bottom-up local planning and decision-making. Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution grants to the congress the power to regulate commerce among the states (i.e., the commerce clause). Kayden argued, “because the use of land by one party inevitably affects others and because such others can reside across state lines from the initial user, the constitution axiomatically grants the national government the power to control local land use” [1] (p. 451) and [7].

For example, consider California’s land use restrictions on the construction of new homes in sensitive coastal areas; new home construction and its environmental impacts, such as carbon emissions, were not eliminated by California’s restrictive regulations but merely moved elsewhere to communities with a surplus of land, including Las Vegas, Nevada and Houston, Texas [10]. A completely local perspective and authority for land use policy and regulation is inadequate for producing benefits from lands for the wider society, economy, and ecology of the United States. Thus, the time is nigh to organize the physical landscapes of the United States under a unified land use policy and planning framework.

Environmental problems in the United States, resulting from managing a highly connected landscape as a bundle of independent fragments, are not going away [3,11]. Fragmentation and a lack of focus on connectivity are not the only sources of environmental and social problems. A lack of regional and national planning policies for land uses and an over reliance on local planning authority and city zoning laws have created and exacerbated these issues [1,6,12]. There are a number of pressing problems in the United States and elsewhere that justify reopening a dialog geared toward land use planning and policy at the national level. For example, planners, regulators, and land managers face ubiquitous non-point sources of water and air pollution, resource scarcity (e.g., water in western states) [3,13], urban sprawl and unaffordable housing [1,6,12], environmental injustices and social disparities in health related to the environment [14,15,16], social vulnerability to flood exposure [17], and the climate crisis (e.g., imminent human migration, displacement, and resettlement caused by changing environmental conditions, extreme weather events, and environmental disasters) [18,19,20].

The wisdom of landscape ecology; the principle of connectivity; and the push towards interdisciplinary, holistic, and landscape-scale planning each support the involvement of higher-level regional and national land use planning in which governmental experts, agency departments and bureaus, tribes, and community residents must participate [3,11,21,22]. These important concepts are brought together in ecoregional planning, which is organized around geographically and ecologically mapped areas of land called ecoregions [23,24]. We use ecoregions as the primary basis of our proposal for establishing a national land use policy and planning framework for the United States.

2. Background

2.1. Rationale

Outside federal and state lands, land use planning in the United States has primarily remained the purview of city, county, state, and tribal governments. These levels of organization are important and must retain a strong voice and hand in land use policy, although a wider perspective is also needed to account for the vast ecological and societal diversity of the nation. There is a need in the United States for an appropriate organizational and regulatory framework to determine how much of the nation’s physical landscapes should go to intensive and moderate human settlement (i.e., urban and suburban), large- and small-scale farming (i.e., various agricultural areas), and natural areas (e.g., national and state parks, wildlife refuges, national forests, multiuse rangelands, urban forests).

A better and more carefully planned organization of the nation’s physical landscapes holds high potential to enrich human experiences, improve well-being, achieve social equity, and ensure ecological integrity [25]. Different land uses do not always conflict and may be complementary. For example, some agricultural lands provide ecological services and are important for biodiversity conservation. Different landscapes and places are connected through human cultures and technologies, belief systems, livelihoods, lifestyles, and relationships with the land and land managers, both public and private [25,26,27,28].

Managing large, connected landscapes as individual fragments and for single species and single economic pursuits has been problematic [11]. However, we do not wish to overemphasize, beyond what we described in the introduction, environmental problems, land use conflicts, and degradation as our primary motivation for proposing a national land use policy, nor do we propose a threat to private landownership. Healthy and trusting partnerships and collaborations with our nation’s private landowners are essential to any form of landscape-scale planning and policy. Likewise, we do not propose a threat to tribal sovereignty and indigenous rights to lands and resources. Indigenous peoples’ relationships with their territories are deep rooted and substantially older than land-based relationships of settler colonialists in the United States. The land use policy and planning framework proposed here includes tribal nations and recognizes the painful history of colonization and land dispossession for the indigenous peoples of the United States.

We emphasize and present a solution that should improve human well-being and reduce environmental injustices through better landscape organization and land use regulation grounded in an alternative, hybrid form of governance. Natural resource decision-makers and managers will continue to fail to set and achieve future desired conditions for sustainable land use without national support and funding that is tied to a unified land use planning and regulatory framework, including local and regional participatory planning with legal decision-making authority [29]. Hoŕelli defined participatory planning as “a social, ethical, and political practice in which individuals or groups, assisted by a set of tools, take part in varying degrees at the overlapping phases of the planning and decision-making cycle that may bring forth outcomes congruent with the participants’ needs and interests” [30] (p. 611). In this paper, we add policy and regulations for land use to Hoŕelli’s list of outcomes of participatory planning. Continued failure to plan for and regulate landscape uses, land use changes, and land management in a comprehensive and well-organized way will perpetuate a myriad of environmental impacts [31] and a waste of resources, time, and quality of life for all citizens of the United States.

2.2. Purpose and Method

The purpose of this perspective paper is to open a discussion on and provide a vision and implementation strategy for national land use planning and policy based in the co-governance and co-management of landscapes. Our vision includes (1) building a national framework for land use legislated and funded by the United States congress; (2) decision-making roles for local and regional landowners, tribes, residents, and other beneficiaries and stakeholders; (3) ecoregional comprehensive land use plans; and (4) advisory and support roles for all levels of government agencies, including tribes, scientists, land developers, and non-governmental organizations in the United States.

We outline a Sustainable Ecoregion Program (SEP) for natural resource professionals and local and regional planners to organize urban and other developed lands, agricultural lands, and lands with largely continuous, natural landcover types1. We apply the ecoregion concept as the central organizing feature of the proposed framework because ecoregions delineate patterns of terrestrial and freshwater biodiversity and the distinctive ways in which humans have used ecoregions through time [23,33].

We present the framework as an organizational tool to alleviate the pressures of development and agriculture while capitalizing on the strengths and benefits of these legitimate land uses. The SEP will enable planners, managers, tribes, citizens, and regulators to create formal partnerships and collaborate across jurisdictional boundaries and levels of government. To implement the proposed framework, we propose a representative co-management system with regulatory and decision-making authority at local levels combined with national legal direction and substantial coordination among local, state, tribal, and federal participants.

Through this perspective, we showcase the historical and current developments in the field of land use planning specific to national-level planning and policy in the United States. An emphasis is placed on future directions in the field and the coauthors’ personal and professional assessments of the topic area [34]. The method is used to present our vision, goals, objectives, and strategies for establishing the SEP in the United States, supported by and in the context of the existing literature.

We have included a targeted review and synthesis of the peer-reviewed published literature and other credible sources, without specific time bounds on the date of publication. The coauthors’ points and arguments in the paper are supported by interdisciplinary but closely related citations of the pertinent literature. In a large-scale comprehensive framework such as the proposed SEP, it is important to cover topics that go beyond conservation ecology and land use planning and delve into the human dimensions and social sciences to cover key socioecological and sociocultural aspects of land use planning. Thus, we include references and information on just sustainability and environmental justice in the context of sustainable urban development and land uses in developed areas with sociocultural connections to natural and agricultural areas. The literature review was not exhaustive or systematic but targeted and geared toward supporting our vision and implementation strategies for the SEP.

We did make an effort to include the recent literature in addition to the older sources from our personal libraries and records from past work. The coauthors have been developing this paper and its foundational ideas since 2007, which has required us to continually review and update the relevant citations. To give coverage to more current sources, we conducted a targeted search in Google Scholar using a range of 2021–2025 for the publication dates. The searches used specific search terms arranged in strings:

- Sustainable ecoregion program;

- Environmental justice and landscape management;

- How to balance development agriculture conservation;

- Balanced landscape planning for development agriculture conservation in the United States.

2.3. Vision, Goals, and Objectives

Biodiversity, environmental justice, and sustainable land use depend on professionals working across large landscapes and diverse social and ecological scales. The SEP cannot be successful on a continental scale and across jurisdictional boundaries without congressional support and funding; leadership and coordination by local, tribal, state, and federal governments; effective partnerships; shared goals and objectives; the extensive sharing of resources; and genuine collaboration and delivery across multiple scales [21,22,35,36]. When these conditions merge into a unified coalition, collective action for large-scale land use planning is possible [37].

The SEP will openly and fairly establish and guide a land use planning and decision-making process and a regulatory framework to involve land managers at all levels of government, including tribal nations, private landowners, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and legislators at all levels of government. Representatives from these groups will serve as the SEP co-managers and will be trained and supported by governmental and university experts and scientists to understand, plan for, and provide ecological integrity, social equity, and human well-being [25]. The proposed SEP is grounded in five vision statements that serve as high-level, strategic planning goals for the program:

- Landscapes and their configuration, including developed, agricultural, and natural landscapes, are fundamental for shaping human experiences and quality of life [25];

- Governmental, tribal, and non-profit agencies are empowered to provide comprehensive leadership and services, balanced programs, and land management planning that is sustainable, equitable, and just;

- All states, tribes, and the federal government recognize the importance of broad-scale, participatory, community-based, and shared management authority to achieve and maintain fair governance, just sustainability, and adequate resources for current and future generations;

- The environmental design, planning, and management professions advocate for the public good and social and environmental responsibility [38];

- Working together, legislators, federal and state natural resource professionals, tribes, and private landowners can design and implement a national system of sustainable land use planning and regulation under private, public, tribal, and common property ownerships [26].

The specific objectives of the SEP include: (1) organize all terrestrial landscapes and land use settings in ways that guarantee current and future human families, communities, and societies will be able to make a living from the land and experience greater well-being from landscapes and legal land uses; (2) center land use planning and policy on people and their quality of life to sustain social, ecological, and economic integrity across ecoregions; (3) improve the conservation of abiotic and biotic resources; (4) ensure diverse and healthy communities of plants, animals, and humans (e.g., biodiversity, food security, well-being); (5) make sustainable land use fair and just for all segments of society; and (6) secure life support systems into the future (e.g., clean air and water).

Like any other properly crafted vision, the ideals and goals of the SEP are aspirational and future-oriented and will be expensive. Working towards these ideals is domestically necessary and can be achieved by implementing these specific objectives, future strategies, and future desired conditions for different landscapes as determined and described in comprehensive land use plans for ecoregions developed by the SEP co-managers.

2.4. Landscape-Scale Approaches

Natural resource professionals increasingly recognize and emphasize a landscape-scale approach rather than planning for and managing single resources [22,24,39,40,41,42]. The management of single resources usually does not benefit broader ecological connections and social processes [25,43]. Sayer et al. [42] argued that the integration of agricultural and conservation land uses requires a people-centered approach applied at the scale of landscapes and relationships. Human relationships with places in the landscape are equally as important as the relationships among residents, landowners, and governmental land managers [27,44].

The proposed SEP aligns with planning and regulatory frameworks outside the United States, with examples being Namibia and Nepal, whereby natural areas are located within each ecoregion and complemented by community conservation programs and regulations for which activities can be performed on lands outside natural landscapes [45]. Some SEP ideals and principles presented here are shared by partnerships in the United States that emphasize the management of specific resources or in specific regions across boundaries at the landscape level. A non-exhaustive list of these initiatives is shown in Appendix A. For example, the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives Network (LCC) was a federal program in the United States involved with landscape-scale planning at the continental level and across political boundaries.

The LCC network was the first federal program in the United States focused on the connectivity and persistence of wildlife at the national level [46]. However, the LCC framework primarily was, and may continue to be in some places, a platform for enabling collaborative research partnerships and data sharing; it served scientific and organizational purposes dedicated to landscape-scale conservation and administration of related collaborative research [35]. The LCC structure relied on existing governance, served a non-regulatory function, and had no authority to set rules, desired conditions, or regulations for what and how many activities and land uses can be allowed to occur on the landscape.

The other initiatives and joint ventures listed in Appendix A emphasize land acquisition, scientific research, management partnerships, working with private landowners, and sharing resources and knowledge but have no rule-making authority. Without regulatory authority, it is difficult to consistently achieve land use planning goals and desired conditions. The SEP will have a regulatory function that goes beyond the initiatives and partnerships shown in Appendix A.

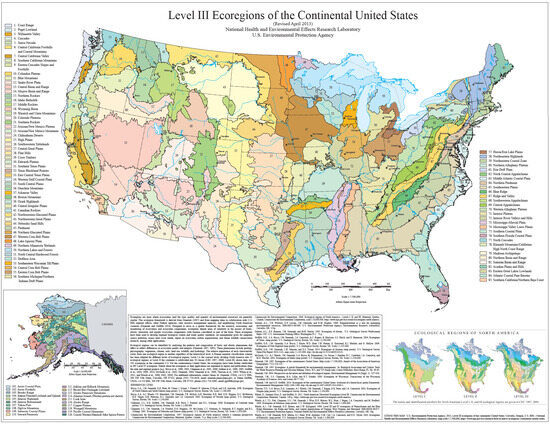

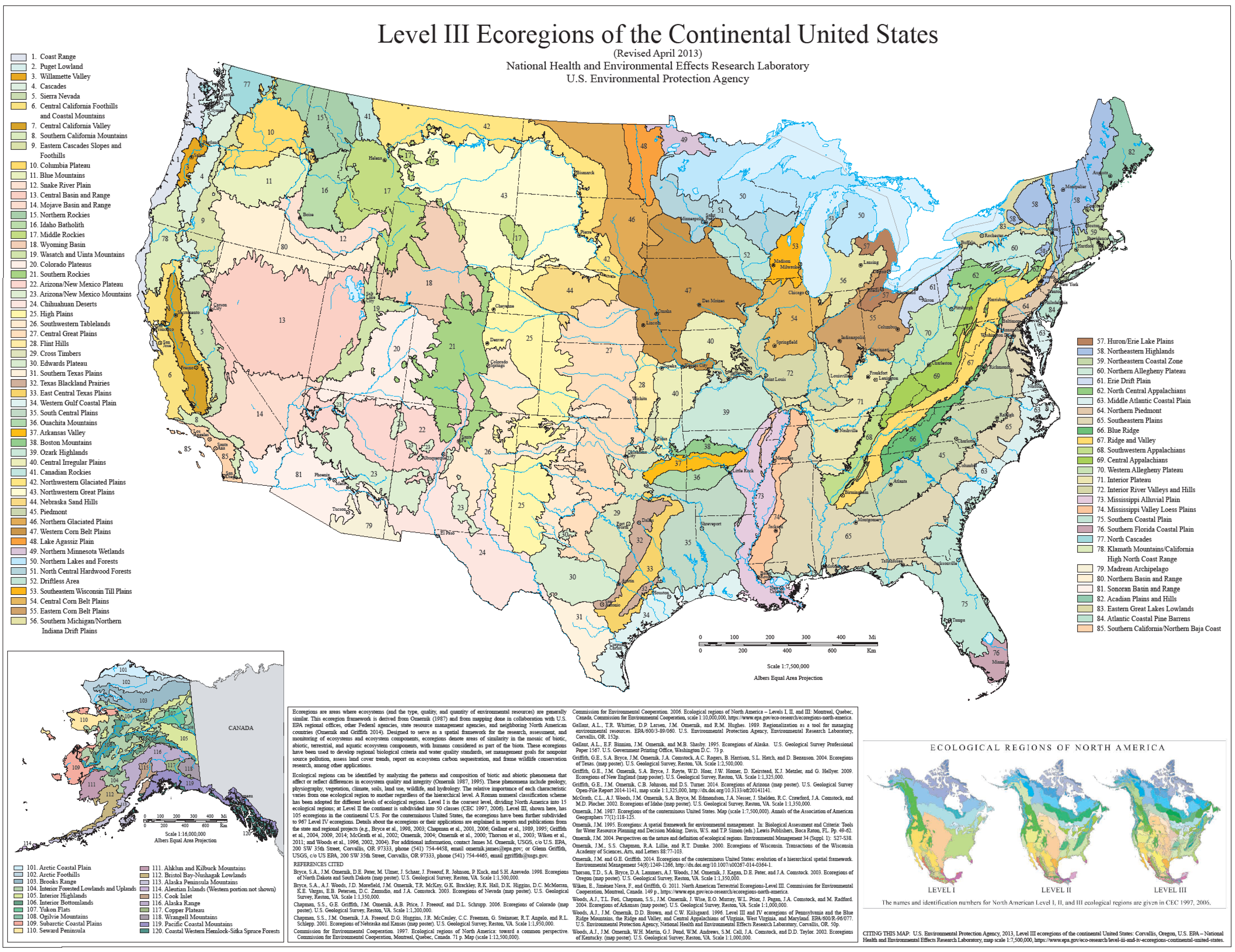

The conservation programs listed in Appendix A use boundaries equivalent to level I or II ecoregions or coarser. As such, we argue that these programs do not allow for the detailed management of unique ecosystems found across the United States. For example, the Great Northern and Gulf Coastal Plains and Ozarks LCCs are each comprised of at least eight different level III ecoregions [47]. With a coarse focus, it is likely some ecosystems are not included in local land use management plans, because the emphasis is more likely to be placed on systems that are rare or harbor endangered species [48]. The conservation of rare ecosystems and endangered species is imperative, although it is also imperative to effectively plan for and manage non-endangered species and more common landscapes, including farms and cities [39,49,50]. The SEP will allow for this by using level III ecoregions as the primary boundaries, and the co-managers will consider and account for level IV ecoregions when establishing secondary boundaries as needed.

2.5. Just Sustainability

Urban land use planning and municipal zoning frequently emphasize politics and economics rather than what is sustainable and socially and environmentally just for all people [6,51,52,53]. The American Planning Association has established principles for urban planning that can be adapted and used as part of the proposed SEP, especially in the context of planning for developed landscapes. “Smart growth is not a single tool, but a set of cohesive urban and regional planning principles that can be blended together and melded with unique local and regional conditions to achieve a better development pattern” [54] (p. 3). The smart growth approaches and policies for urban planning and development initiated in the 1990s [54,55] may still hold promise for improving lives, creating sustainable cities, and reducing urban sprawl but there has been considerable opposition and adverse outcomes in many communities related to smart growth principles and policies, including decreased property values, decreased availability of affordable housing, restrictions on uses of private property, increased sprawl, and other disruptions [12]. Land use policy and ecological design are linked to social and environmental injustices, particularly in and near developed and urban landscapes where a high density and diversity of people live [2,38,51,52,56].

Land use planning must be socially equitable and environmentally just to be sustainable [25,57]. By just, we mean fair, inclusive, and beneficial for all groups of people; by sustainable, we mean the creation and maintenance of conditions in which humans and land can productively coexist and support present and future generations, socially, economically, and ecologically. Environmental justice involves the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in the development and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies, regardless of their race, national origin, or income [58,59].

There are important linkages and synergies between sustainability and environmental and social justice that can be leveraged by policy-makers in a national framework for land use planning and policy [60]. The environmental justice concept has multi-level dimensions, giving it the potential to link local, state, and national land use jurisdictions. Environmental justice is “Predominantly at the local and activist level, a vocabulary for political opportunity, mobilization, and action. At the same time, at the governmental level, it is a policy principle that no public action will disproportionately disadvantage any particular social group” [60] (p. 155). Up until recently, the United States Government had policy and guidance in place to address and integrate environmental justice and the advancement of equity across landscapes and social groups, including Executive Orders 12898, 14008, and 13985 [61,62,63,64].

We can expect to see continued conversions of natural landscapes to urban and agricultural areas as the number of people increases, if we do not establish desired future conditions and make rules and regulations that disallow or limit certain activities within specified boundaries at different scales. The loss of natural landscapes correlates with declines in biodiversity, diminished ecosystem function, and decreased ecosystem services on which humans rely [65,66,67]. However, the conversion of naturally vegetated areas to urban areas, suburbs, and large farms is often completed with little consideration of the externalities or costs to the environment and society [65,68,69]. In the United States, the current system of land use planning and management is neither fair, environmentally just, nor sustainable, as the burden of these costs are most often felt in the near term by lower socio-economic classes and in the future by younger generations and those not yet born, who will have to cope with an environment where we have lost landscape connectivity and depleted our natural resources [70,71].

Environmental justice issues have been addressed by urban planners to varying degrees across the country. For example, community planners in California are doing a relatively good job of accounting for environmental justice issues in community plans [16], whereas urban forest planners across the United States have devoted less attention and detail to environmental justice goals, objectives, and strategies [15]. The proposed SEP will acknowledge and integrate environmental and social justice into land use planning and regulation to address historical and current environmental injustices. To align with Agyeman and Evans’ [60] (p. 157) argument for a balanced approach, the SEP will reframe and refocus environmental justice and sustainability in terms of “just sustainability”; just sustainability is a holistic model of land use planning that highlights quality of life, present and future generations, justice and equity in resource allocation for all people, and living within ecological limits. Without these factors, disadvantaged communities and underserved social groups in the United States will continue to experience entrenched disparities and other injustices.

The national examples of land use planning efforts from the 1930s and 1970s hold lessons for success and challenges to be overcome. The New Deal-era agricultural planning movement showed that the federal agencies and local land users can mobilize a substantial effort, align interests at disparate levels of jurisdiction, and perform participatory and collaborative planning from the bottom up. This effort was relatively inclusive given the state of racial and social class relations in the country in the 1930s and 1940s. The county committees included men and women; whites and blacks; and landowners, tenants, and sharecroppers, most of whom were low-income farmers; however, wealthier white male farmers were over-represented [7]. The 1970s example shows how the U.S. Congress can craft and put forward legislation to direct land use planning and what can derail such attempts. The proposed SEP will capitalize on these lessons from history.

Today, we should strive to be more inclusive and allow all types of citizens in all income levels, races, and classes and living in all parts of the country to become genuinely involved and active in decision-making for land uses in places where those citizens live and make a living. The proposed SEP framework will directly address environmental justice and just sustainability issues by giving historically marginalized and excluded citizens a place on the co-management committees to plan and decide land use management and regulations in and near their homes.

3. Governance Structure

Similar to agricultural planning reforms of the late 1930s and early 1940s, a national land use planning framework requires a bottom-up coordinated approach, implementing the principles inherent to participatory planning, collaborative learning, and shared decision-making [7,30,37,72]. However, the New Deal experience with agricultural planning taught us that thousands of local county-level plans and maps do not necessarily add up, or translate, to an effective and meaningful land use planning framework or policy at the national level [7]. In the early 1970s, we learned that national legislation from Washington D.C. mandating a process of coordination and data collection by lower-level agencies (i.e., state governments) without local decision-making is not a politically viable solution either, with or without rigorous environmental safeguards [3].

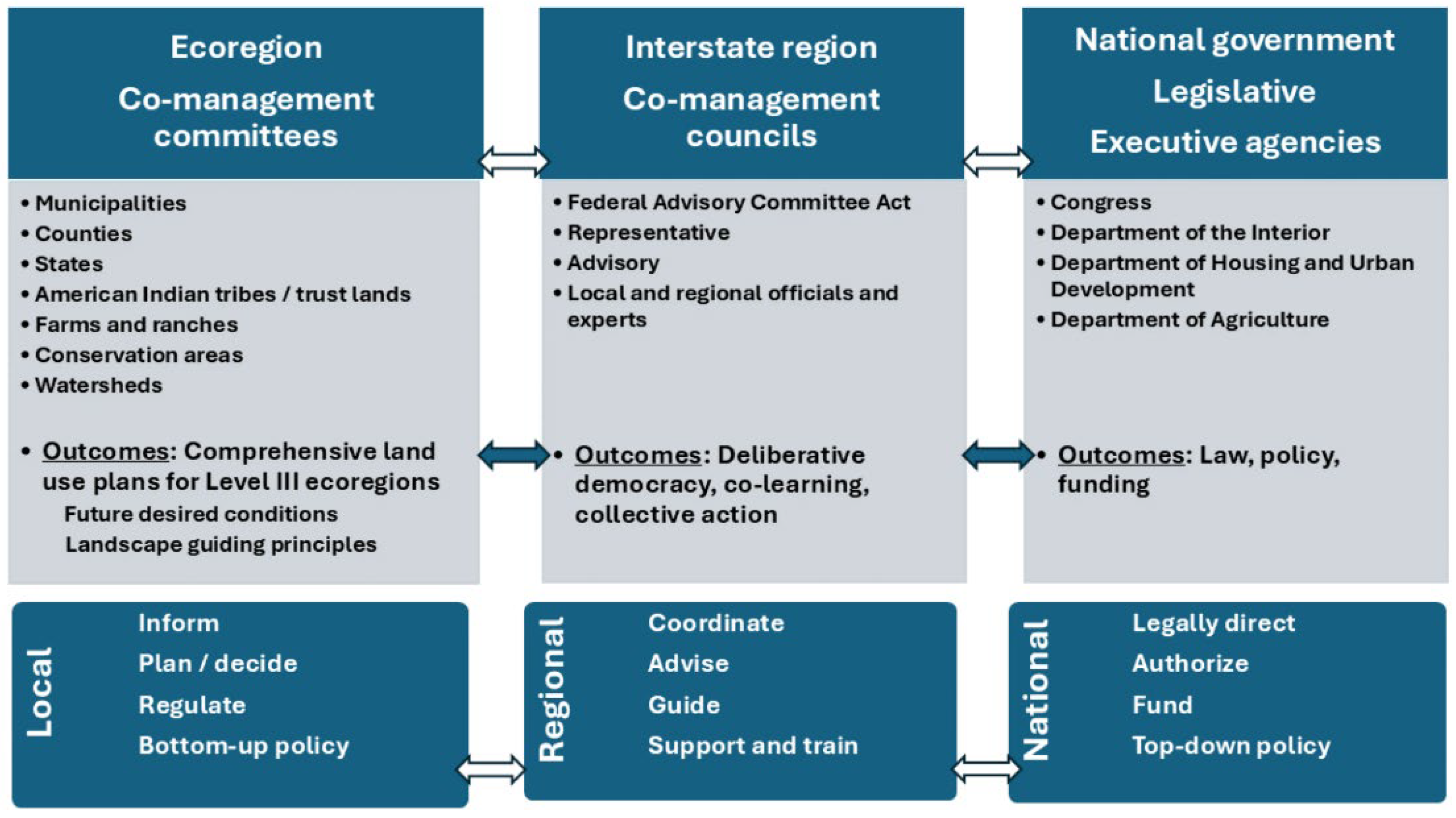

We believe that a hybrid governance system is needed in which there is national direction and allocation of funds from the congress in the form of legislation (i.e., top-down) combined with local participatory planning, policy formation, and shared rulemaking authority at the regional and local levels (i.e., bottom-up). The legal national policy, congressional allocation of funds, and local deliberative democracy via participatory planning [12,30,37,73] should enable and produce a co-management system to organize and regulate the use of lands and resources at a landscape level. The SEP will be a national-level program implemented from the ground up, authorized by national law and policy, with shared decision-making authority among jurisdictions and the support of federal land managers, policy-makers, and university and governmental scientists and land management experts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Governance structure for the Sustainable Ecoregion Program.

Adapting the approach used for the agricultural planning program of the New Deal era (1938–1942), we propose a program that develops and implements a deliberative democratic process among landowners, residents, and other land users, in which these stakeholders formulate land use policy through land use planning. The primary planning and policy decisions will be made by people living in communities, counties, and states within and across ecoregions, not by national government and university experts and scientists; these higher-level experts’ roles in the proposed SEP will be to advise, support, educate, fund, and help coordinate the local-level land use planning committees [7].

The national, regional, and local environmental practitioners who organize the SEP (i.e., an interagency and interdisciplinary working group) will require representatives and supporters from communities, counties, states, and tribal governments. Setting up and implementing the SEP will require immense levels of cooperation between states; tribes; farmers, ranchers, and other private landowners; NGOs; and federal land management agencies. One of the first actions after the congress authorizes and funds the initial phases will be to establish a SEP working group to organize and form the co-management councils and committees (Figure 1). To cultivate support and trust, the diverse partners will be required to develop shared values and objectives and a common language for land use planning, regulation, and management [37]. Initially, they will be challenged to arrive at consensus and collective action on goals and objectives and will need to begin by setting easy-to-reach intermediate objectives to establish trust and a foundation for working together [42,74].

In the beginning of SEP formation, the partners will spend substantial time developing and implementing formal co-management agreements and arrangements, some of which may rely on existing authorities [75]. The program will require new legislation, amendments to existing laws, and funding from several sources, including large amounts of resources and coordination from the state and federal governments and new legislative appropriations. We envision one or more laws enacted by congress to implement the SEP on all lands in the United States, perhaps the Sustainable Ecoregions Lands Act (SELA), which authorizes the SEP as the national land use policy. The SELA could be partly modeled after portions of existing laws and bills and past programs, including the New Deal, Agricultural Adjustment Administration; Senate Bill S. 3354, National Land Use Policy Act (proposed bill); Coastal Zone Management Act; Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act; Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act; Federal Advisory Committee Act [76]; and other environmental laws and programs [1,3].

The guiding framework for administration and coordination will come from the national level, although the SEP will be implemented at multiple levels of decentralized governance through co-management councils that consist of regional, state, and tribal representatives and their designated planning and decision-making committees (Figure 1; Section 4.2). Citizens and governmental authorities from all regions of the United States will be represented and will work through their respective co-management bodies to set and enforce SEP policies and regulations.

Like municipal zoning, SEP land use regulations and interventions will be guided by comprehensive land use plans developed with meaningful and genuine tribal consultation and public involvement as appropriate. Brooks [77] explained that sovereign tribal nations have a unique relationship with the United States federal government based in the federal trust responsibility, and tribes are not to be simply involved as members of the public due to the legal relationship tribes have with the federal government. The federal agencies that support and participate in the SEP will invite tribal nations to formal government-to-government consultations regarding the work of the SEP and the ecoregional comprehensive plans. Committee members will include private landowners such as farmers and ranchers, tribal leaders and indigenous land managers, and other stakeholders, and they will have decision-making authority, not merely serve an advisory role under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA).

This governance structure and process will result in well-informed and well-supported legal decisions and consistent management guidance across jurisdictional boundaries. Comprehensive land use plans will be developed for each level III ecoregion. These ecoregional plans will contain goals, objectives, and future desired conditions, including the intensity of landscape uses such as large- and small-scale agriculture, outdoor recreation, and housing developments. Land use designations, management interventions, and continued program funding will be guided and directed by the comprehensive land use plans developed by the co-managers.

4. Discussion and Program Implementation

The implementation of the SEP involves several steps:

- Recognition of level III ecoregions as primary boundaries (Appendix B);

- Creation and provisioning of SEP co-management councils and committees;

- Definition of physical landscape types and settings;

- Definition of secondary planning boundaries;

- Determination of future desired conditions;

- Establishment of guiding principles for the management of each landscape type.

4.1. Ecoregions as Primary Boundaries

Ecoregion designations already exist, and experts have demonstrated that ecoregions are a suitable approach to land use planning and ecosystem management [24,33,45,78,79,80,81]. Ecoregions were designed in response to governmental recognition of the need to manage systems across political boundaries [79]. Ecoregions are unique functional areas that share similar ecosystems, landcover types, biotic communities, environmental resources, and sociocultural and socioecological systems [24,82]. Ecoregions have natural boundaries similar to watersheds. Interactions between climatic conditions, geographies, abiotic elements, and endemic plant and wildlife communities have created distinctive ecoregions.

Human populations and their settlements rely on ecosystem services and environmental resources provided by and within ecoregions. Over time, people have modified ecoregions and adapted to their different and changing conditions. Thus, there are somewhat distinct socioecological systems within each ecoregion, and ecoregions are distinctive in the ways that humans have used these regions [23]. The SEP framework will be designed to account for people and their cultural and ecological relationships to ecoregions. The main goal of sustainable ecoregional planning is maintaining “the balance between the ecosystem, economy, and society, where the combination of local and human needs is highlighted with environmental conservation and biodiversity perspectives” [24] (p. 685). The concept is ideal for landscape-level plans because “ecoregions provide a way to integrate different ideas, and social and physical processes, across scales” [23] (p. S5).

Appendix B shows that the level III ecoregions are large, with many crossing multiple state lines of jurisdiction. Ecoregions encompass landscape and sociocultural diversity and provide the primary boundaries co-managers of the SEP can use to organize and maintain landscape diversity and preserve the unique flora and fauna, ecosystems services, and human cultures and relationships with the land in these ecoregions. For example, ranching cultures and families in the western states are included in the SEP process in both AL and NL, and representatives from the ranching communities will be part of the local and regional SEP planning committees; these private landowners are key stakeholders and decision-makers in the proposed SEP.

The same is true for indigenous peoples, as they have ancient and complex relationships with landscapes and sacred sites in North America [28,83]. These connections can be thought of as tribal cultural landscapes [84]. The ancestral and traditional lands of American Indian tribes and Alaska Native Peoples still exist as part of the present-day cities, counties, states, and ecoregions. Some indigenous peoples have been removed or displaced from their ancestral lands, but they still have interests, cares, and concerns for these ancestral lands. The nation’s indigenous peoples have deep cultural and spiritual connections to their homelands. Their ancestral lands are now composed of developed urban places, agricultural lands, and natural protected areas. The SEP committees will include tribal representation, and these co-managers will include tribal cultural landscapes, when and where appropriate; Native American Indian reservations and other trust lands; and local and regional scared sites, viewsheds, and landscapes where appropriate.

Ecoregions have been defined at broad (level I) to fine (level IV) scales [47,85]. We propose that level III ecoregions provide the most suitable delineation for primary boundaries for the SEP (Appendix B) [82]. Although level IV ecoregions would be optimal, there are 967 level IV ecoregions compared to 105 level III ecoregions for the contiguous United States and Alaska. It would be difficult to maintain the organizational framework required if level IV ecoregions were used as primary boundaries.

Level IV ecoregions (or watershed boundaries that lie within level III ecoregions) will need to be considered, and possibly adapted to the SEP, to capture and represent the social and ecological diversity of landscapes nested within some level III ecoregions at smaller scales. Once the SEP is established and operating satisfactorily, the co-managers of the largest ecoregions may wish to include level IV categories or watershed boundaries to capture local issues and provide finer-scale regulations and management interventions if, when, and where appropriate. The SEP will allow for this type of flexibility, especially in the case of watersheds, given their established importance to conservation ecology and human and ecosystem health. Such nuances and allowances for flexibility in planning will be captured, described, and accounted for in each ecoregional land use plan.

4.2. Co-Management Councils and Committees

An initial working group of SEP organizers (i.e., the SEP working group) will set up and establish two types of groups that will ultimately implement the program: interstate, regional co-management councils and ecoregional co-management committees (Figure 1). The initial organizers on the working group will be a combination of officials and experts from the state and tribal governments, universities, NGOs, and representatives from federal regional offices, including the U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Department of Housing and Urban Development. In consultation with attorneys specialized in establishing FACA advisory groups, the SEP working group, coordinating and talking with legislators at the national level and experts at the regional and local levels, will establish approximately nine regional co-management councils to shepherd the SEP, one each in the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, Southeast, Great Lakes, Midwest, Southwest, Hawaii, Pacific Northwest, and Alaska regions of the country. Membership of the regional co-management councils will primarily consist of natural resource, land use, and urban planning professionals in city, county, state, and tribal governments; NGOs; and community representatives, including private landowners. Many of the SEP working group members will most likely stay involved as members of the SEP co-management councils.

Initially, the SEP regional councils’ primary functions will be to advise, liaison, and coordinate with the regional and national federal government agencies, most likely land managers at the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture and representatives from the state governors’ offices. There will also be a need to include experts from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Another main function of the SEP regional councils will be to set up and support the decision-making and planning work for each co-management committee (i.e., one committee per level III ecoregion) as they develop comprehensive land use plans for their respective level III ecoregions.

The SEP co-management committees will primarily be comprised of natural resource and land use professionals in state, county, tribal, and community agencies and organizations. Tribal council presidents, municipal mayors, city managers, county planners, and private landowners and farmers will be included on the committees to represent communities and local governments. The committee members will be from each state either in or encompassing each level III ecoregion and will include one representative from a state outside the ecoregion to act as a neutral observer. The number of members from each state and stakeholder group to serve on each ecoregional committee will be determined by its regional SEP co-management council. The regional councils will provide technical support and logistics for the process and coordinate, guide, and train the committees’ work and membership.

All members of the ecoregional committees will receive training on incorporating the principles of transparency, information management, just sustainability, and citizen participation for the planning and implementation of the SEP [29]. The program will also provide nominal compensation in the form of honoraria for the time commitments of the co-managers and cover most travel expenses when travel is required. The principles of deliberative democracy will be taught while training the committee members [12,73,86]. Frameworks of environmental governance highlight how to apply and evaluate the process against criteria such as accountability, direction, and capacity that the SEP councils may use when guiding and instructing the work and decision-making of the planning committees [87,88]. A framework developed by Campellone et al. [21], the iCASS Platform, should be used by the SEP councils and committees to ensure principles of landscape planning, design, and collaborative science are incorporated into decisions made by the co-management bodies. The co-managers will focus on mutual respect, equity and equality, inclusivity, trust, transparent communication, the interdisciplinary establishment of desired future conditions, and participatory planning [12,21,30].

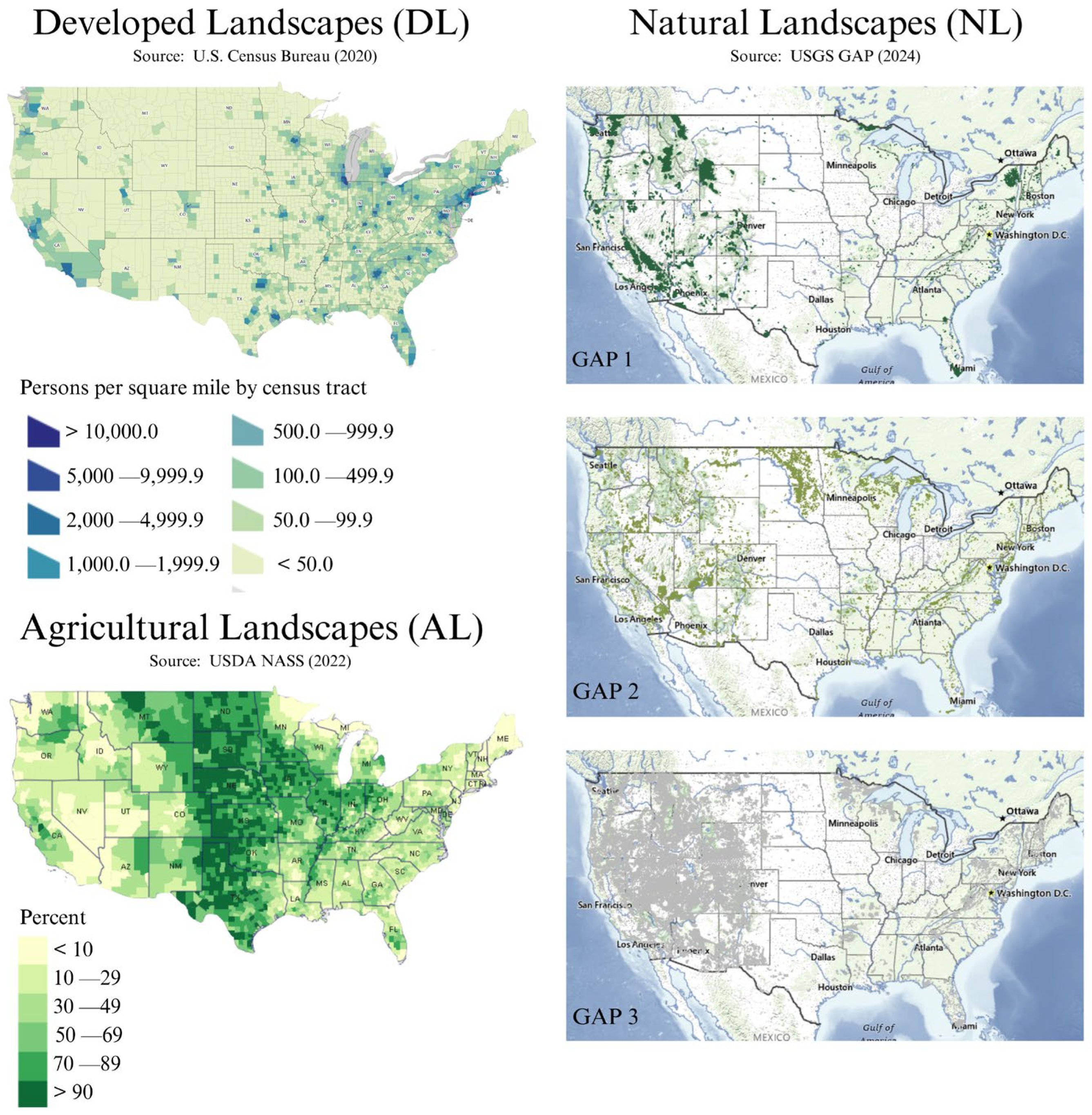

4.3. Physical Landscape Types

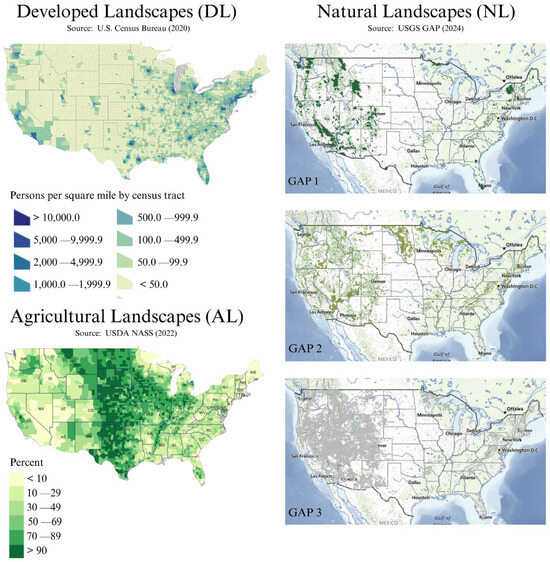

The surface area of the United States will be classified into three physical landscape types: developed landscapes (DL), agricultural landscapes (AL), and natural landscapes (NL) (Figure 2). Each physical landscape type will be managed at a low, moderate, or high level of use intensity based on prescriptions from the SEP co-management committees and directed by the comprehensive land use management plan for each ecoregion. The result will be a 3 × 3 matrix of combinations for a total of nine physical landscape settings (Table 1). The SEP co-management councils and committees will work together to define the composition of the intensity levels in the early stages of development of the ecoregional land use management plans.

Figure 2.

Maps of the 2020 U.S. population based on U.S. Census [89] data representing developed landscapes (DL), percentage of land in farms representing agricultural landscapes (AL) from the USDA [90] Census of Agriculture, and protected areas classified into three GAP categories representing natural landscapes (NL). The GAP categories vary in their level of conservation protection, from GAP 1 being the most protected to GAP 3 being the least protected, implying increased land use intensity as one moves from gap 1 to gap 3 [91].

Table 1.

Nine landscape settings for the SEP arranged in a 3 × 3 matrix of landscape type by intensity of human use.

Published maps and descriptions define some NL, particularly for public lands, otherwise known as protected areas with well-demarcated boundaries (Figure 2). Private landowners would be engaged on the councils and committees to define areas of NL on private lands. The current extant DL and AL are relatively well defined (Figure 2) but are in a continual state of change because these fluctuate throughout landscapes over time. The primary function of DL is to provide an area for humans to live a healthy and comfortable life and for industries to sustain production, jobs, housing, and economies within ecological limits.

The AL will often have fewer humans present than the DL and will be carefully managed for food and fiber production while maintaining populations of native flora and fauna. The primary function of NL will be to provide ecosystem services and sustain communities of indigenous and endemic plants and wildlife populations. NL will provide places for carefully managed visitation by humans for outdoor recreation, tourism geared toward culture and ecology, fishing, subsistence harvest and gathering, sport hunting, the enjoyment of solitude, visitation and ceremony by indigenous peoples at sacred sites, and other beneficial but limited land uses as determined by the SEP and published in the comprehensive land use plans for each level III ecoregion.

The NL primarily consists of publicly protected areas and privately owned natural areas and landcover types managed for ecological integrity and human uses and enjoyment. Where appropriate, many land uses on private lands could be managed as part of the SEP by the landowners, using conservation easements, land trusts, and other mechanisms devised by the landowners or the SEP co-management committees on which they serve or are represented by their peers. Private landowners will be decision-makers in the governance structure. The SEP co-managers will establish norms and procedures for deferring to the legal rights and practical and livelihood needs of farmers and ranchers in all but extraordinary decision-making and regulatory situations.

Conflicts between private and public property cultures in the United States should not be overemphasized when it comes to sustainable landscape planning, as the inclusion of private lands is necessary to allow connectivity; alternatives to exclusive public or private land tenure exist and may be developed for communities, regions, and ecosystems [26] (p. 57). For some landscape settings, the SEP councils and committees may have to set in place a common property system of land tenure.

Common property is a form of shared private property where individuals jointly own rights to a resource system or have shared rights to use a resource for grazing livestock or gathering firewood, for example [92]; common property tenure offers efficiencies in the management of common pool resources ([68] (p. 227) and [93]). In densely populated urban and suburban areas and where resource uses are intense, the SEP co-managers may find a common property model desirable to control economic externalities [68]. Common property arrangements do not allow unregulated uses and non-members may be excluded. “Commons limit use because only community members have a right to use them. Many commons have rules limiting use (limiting the season for grazing, limiting types of livestock, etc.) … common property refers to a situation where there are controls over the use of the resource” [92] (p. 3).

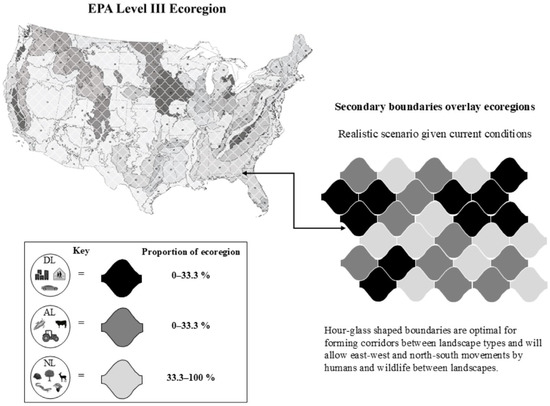

4.4. Secondary Boundaries

The SEP committees will be allowed flexibility when planning secondary land use planning boundaries within each level III ecoregion. The national SEP direction will provide guidelines and broad rules for setting secondary boundaries; there could be a set of options or alternatives in terms of shapes, sizes, and corridor types for this land use planning layer. The local SEP committees will have decision-making authority to determine specific details and spatial arrangements. Since some ecoregions run east-to-west and some north-to-south, there may be a need to be flexible in determining the secondary boundaries’ shapes, extent, and direction (Appendix B).

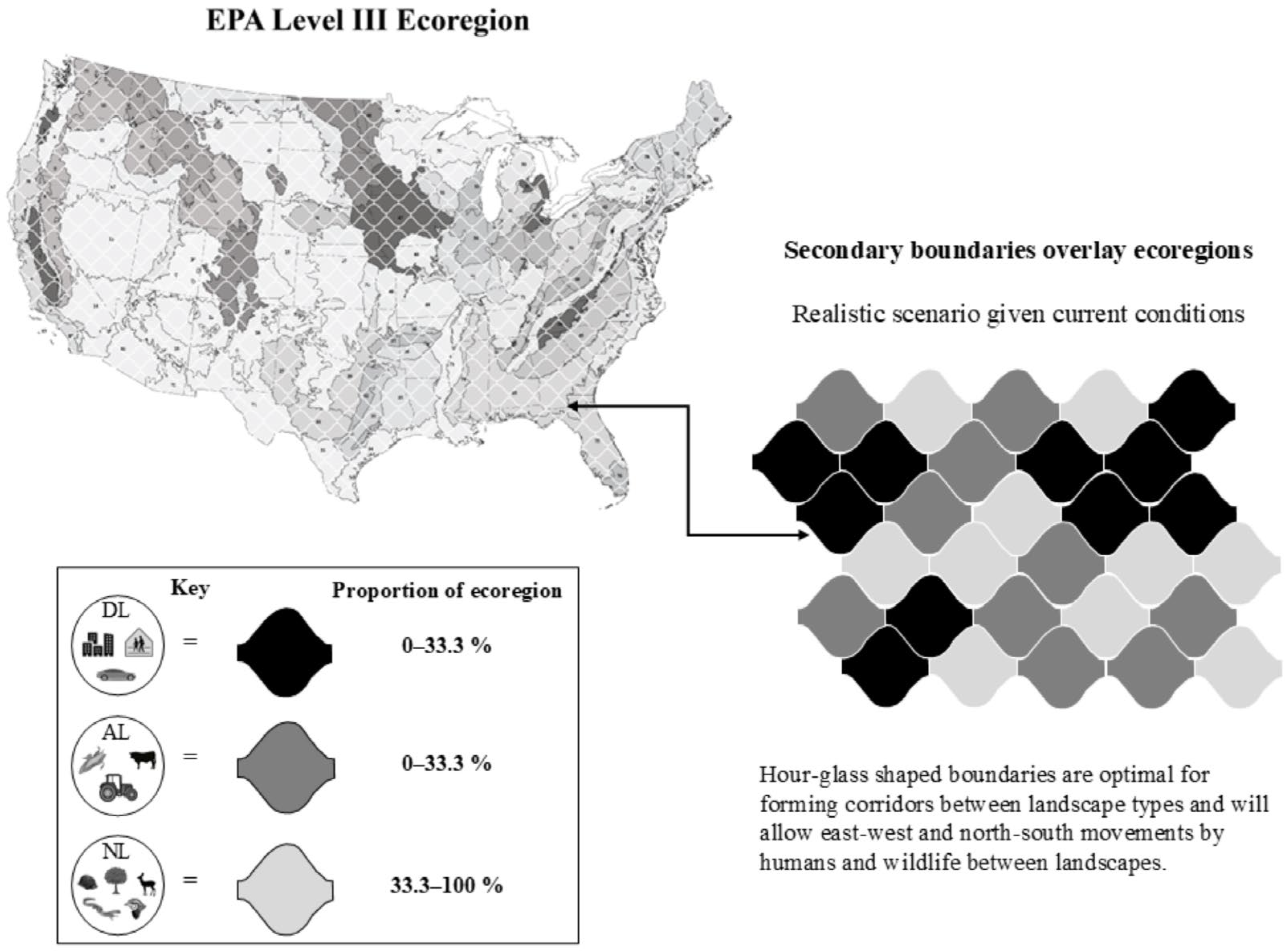

For demonstration purposes, we recommend that the SEP committees and counsels explore how to connect ecoregions with a type of side-by-side and end-to-end hourglass-shaped grid or overlay with alternating areas of DL, AL, and NL to encompass all level III ecoregions (Figure 3). The hourglass grid is conceptualized as a land use planning layer, overlaid atop the core ecoregions layer. This layer of secondary boundaries will allow portions of all ecoregions to remain conserved as NL and have permanent connectivity to all other ecoregions. We recommend maintaining a classical, medium bulbous-shaped hourglass throughout each ecoregion and across adjacent ecoregions versus long, flattish grid shapes or near round ones. With a medium shape, an eye looking at a map of planning layers should be able to pick up on the same hourglass shapes or patterns running as both east-to-west and north-to-south.

Figure 3.

A map of the Environmental Protection Agency’s level III ecoregions [82] and proposed placement of hourglass-shaped (i.e., corridors and patches) secondary boundaries to define developed landscapes (DL), agricultural landscapes (AL), and natural landscapes (NL) within each level III ecoregion. The size and direction of the secondary boundaries could vary from those displayed on the map and will be decided by the Sustainable Ecoregion Program co-managers. Note: The ecoregions are numbered and correspond to the labels shown in Appendix B.

Figure 3 depicts a hypothetical grid overlay that roughly matches the realities on the landscape today in which DL, AL, and NL are dispersed in patches or clusters. Ideally, each landscape type would occupy a complete latitudinal row of hourglasses and alternate in the DL–AL–NL order to maintain connectivity. For example, if DL were organized in east–west rows, existing U.S. highways with even numbers (running east–west) could run through the centers of the DL hourglass rows. The idea is to enhance their connectivity while fully organizing the three landscape types to address issues of environmental management, including the carbon footprint related to transportation, aesthetics, the simplified control of nuisance wildlife or feral animals, and the control of the threat of invasive species. Figure 3 depicts a scenario example that is less desirable but still provides improved outcomes for many already populated areas and matches current conditions. However, when DL, AL, and NL are not arranged in rows, travel distances to the same area types are longer. The SEP co-managers will strive for the ideal placement pattern of secondary boundaries within each level III ecoregion to the extent practicable.

This proposed spatial arrangement is based on approaches developed in landscape ecology, sustainable development, and ecoregional planning [24]. The main spatial and physical elements of a landscape are the substrate, patch, and corridor, and the landscape planner’s objective, among others, is to maintain connectivity for the movement of species and people [24,94]. Figure 3 shows the proposed hour-glass shape of the boundaries, which is optimal for forming corridors between the 3 landscape types and will allow movement between each by humans and wildlife. The design of corridors in SEP comprehensive management plans for each ecoregion will account for the specific needs of plants and animals, including humans, within each level III ecoregion [95,96]. The hourglass shape, concurrent with a carefully planned spatial configuration, will allow humans to experience each landscape type nearby their homes. This will more closely tie people to their food and local environments, preventing disconnects associated with the separation of past generations from food and fiber production and the stewardship and enjoyment of environmental resources [97]. The hourglass-shaped corridors should allow for a balance of interior and edge areas to accommodate species’ needs [98,99,100,101].

The shape of the secondary boundary overlays becomes especially important in forested environments where areas could receive very different sunlight-hours per day due to shading or not and depending on the orientation of the hourglass shape (i.e., east–west orientation, north–south orientation, or an orientation at an angle between the perpendiculars). In forested environments, the orientation of secondary boundaries could have implications for more or less shade per day for the suburban lives of people, forest regeneration, and productivity for timber products and growth hours for crops, which could be controversial and politically charged. The proposed governance structure and deliberative and participatory processes used by the SEP committees are designed to mitigate and resolve these types of conflicts and controversies at the ecoregional level.

Maintaining the hourglass shape (Figure 3) would protect ecoregions long term even as ecoregion classifications change in the future. That is largely why maintaining a perfect medium hourglass shape is important throughout. Climate change already has plant and animal communities shifting, mostly north and south. From a wildlife management perspective alone, there may be reasons to argue for a different shape of hourglass. Concepts such as the patch size and edge effect would be impacted. The SEP co-managers will address these nuances and options for spatial arrangements on an ecoregion-by-ecoregion basis in the comprehensive land use plans.

For example, wherever natural corridors or passes are absent, SEP co-managers could interweave and link the areas of DL, AL, and NL with overpasses and underpasses at the narrowest junctions in the hourglass grid layer to act as corridors between landscapes. The SEP committees and councils will determine the size of the overpasses and underpasses and direction as appropriate. The DL and AL are currently connected in a suitable way to allow for the movement of humans and commodities via existing infrastructure and roads. The SEP co-managers will establish and organize corridors to connect NL across the secondary boundaries where necessary and accommodate already established private property, human structures, and existing rights of way.

Again, flexibility will be allowed for the SEP committees to establish the specific dimensions and exact shapes of the secondary boundaries based on the ecological needs of populations of endemic species and the sociocultural makeup of human populations and their needs, such as food security and outdoor recreation. The SEP committees will consult with the councils’ experts and other botanists, biologists, and ecologists for expertise and supportive guidance to identify locations, home ranges, and space requirements for the long-term viability of species in each ecoregion.

Economists, anthropologists, and other social scientists will provide guidance for accounting for the sociocultural factors and needs of the people living in the ecoregions. For example, tribal cultural landscapes and sacred sites will require the desired conditions and land use intensities prescribed in the ecoregional plans. In terms of wildlife, the bobwhite quail requires large areas (i.e., 800–9600 ha) to maintain viable populations [102], and the pronghorn antelope relies on specific migratory pathways [103], for example. The committees will need to account for species’ space requirements when setting the size of secondary boundaries and establish corridors along the edges of or across secondary boundary zones for some DL and AL. The SEP co-managers will use existing maps to identify naturally occurring secondary boundaries within ecoregions and determine which landscape type will be associated with each secondary boundary [46].

A high percentage of some ecoregions currently are in agricultural development or private rangelands, and the SEP co-managers may consider restoring a portion of AL to NL to achieve desired future conditions. The aim is not for each of these boundaries to exclude the other types of lands but to allow for setting regulations for what and how much future development and intensity of land uses can occur and where to focus restoration when needed. Human life, health, and welfare are linked to ecological services and natural resources [104,105,106], and some species of wildlife and plants have become common residents of DL [107,108]. Some NL is present within the DL secondary boundaries to benefit human health and enjoyment and maintain flora and fauna in urban and suburban environments and green spaces. Conversely, some NL contain amounts of DL and AL.

Once the spatial arrangements of secondary boundaries are determined for NL, no further conversion to DL or AL should occur, and the SEP planners and co-managers should focus restoration efforts within those boundaries to reestablish or maintain healthy ecosystems.

4.5. Desired Future Conditions

The three physical landscape types serve as the basis for establishing the desired future conditions. The desired future conditions will be defined early in the implementation of the SEP and planning process used to develop the ecoregional plans. Discussing and determining the desired conditions will require coordination among the co-management councils and ecoregional committees and substantial input from stakeholders to reach consensus on what use limits are acceptable. The desired conditions will appear in each comprehensive plan as a series of statements. Desired condition statements are aspirations that describe the desired conditions within the three landscape types. The desired conditions address conditions, not management actions; these statements indicate what is desired, not how it will be achieved [109]. However, statements of desired conditions should be written clearly enough and with proper detail to guide management actions.

We recognize that different desired conditions may be applicable to different scales within ecoregions and landscape types. For example, the desired conditions will vary depending on whether the planners are addressing patches of habitat, watersheds, or ecosystems. Not all scales of land and land use will be included in every ecoregional comprehensive plan, as the physical spaces of ecoregions vary across the country. For example, a small ecoregion may not encompass an entire watershed but may contain all of the habitat of an endemic species that has a small home range.

The first step is to determine spatial arrangements for all physical landscape types, using already established level III ecoregions as primary boundaries. Spatial arrangements include landscape components such as corridors for species migrations and movements, secondary boundaries within level III ecoregions, patch sizes, and rights of way to accommodate varying types and intensities of land use, land access, and overland travel. The desired future conditions will include the intensity of management, quantities and qualities of endemic plants and wildlife, and allowable levels of human interactions with the land. Other desired conditions are possible and should vary across ecoregions, including land use activities, resource conditions, habitat functions, human experiences and opportunities for visitors, the size and type of agricultural production, and ecosystem services.

The committees will design planning layers to overlay onto the ecoregion boundaries and serve as secondary boundaries and corridors and choose desired future conditions that will endure time and societal pressures. The desired conditions will vary spatially but not necessarily temporally, especially not in the short term. “Desired condition statements provide long-term vision for an area. They describe future conditions, not necessarily what exists today; and they are not necessarily time-bound nor do they include completion dates. Desired condition statements consider potential changes due to climate change” [109] (p. 25). The desired conditions will be reviewed and may be revised if appropriate when the comprehensive plans are reviewed and revised.

The DL and AL each ideally could occupy up to one-third of each ecoregion, and the NL should occupy a minimum of one-third of each ecoregion (Figure 3). The 33% target for NL is lower than the scientifically recommended target of 50% suggested in the Nature Needs Half agenda [45,110]. Our minimum target for NL recognizes there are areas nested within the AL and DL that are relatively healthy and functioning ecologically as NL. For example, timber companies and many non-industrial forest landowners in the southeastern United States often plant loblolly and slash pines in areas that were once longleaf pine savannahs [111]. Although the overstory tree composition is not native, many of these companies manage for a relatively continuous understory indicative of longleaf pine wiregrass ecosystems that benefit wildlife [112]. Indigenous wildlife managers practice land stewardship and habitat restoration on American Indian reservations. Ranchers in the western United States practice land stewardship and environmental conservation on private rangelands and federal grazing allotments [113]. Parts of private and tribal lands will most likely contain areas of NL.

Additionally, NL will include small urban parks, small urban forestlands, and some relatively larger green spaces (e.g., Central Park in New York) for outdoor recreation, scenic beauty, spiritual connection, limited and regulated resource harvests in some places, the preservation of flora and fauna, and other benefits and services. These types of NL may be encompassed by DL or located in and near AL. The SEP could ideally achieve a target of at least 50% of each ecoregion being NL and will strive to exceed this target wherever possible. The conservation of 50% of NL may not be possible in some imperiled, threatened, or recovering ecoregions [45]. In many contexts, AL serve similar functions to NL due to the stewardship and conservation values and practices of farmers, ranchers, and tribal land managers who understand the importance of respectfully caring for and efficiently utilizing the lands that support their livelihoods and families [113,114].

One-third of each physical landscape type will be managed at low-, medium-, and high-use intensities, and the committees will aim for 33% or more of each NL at each level of intensity to be publicly or communally owned. The decision-making for each area must match the definition and intent for each of the three physical landscape types and nine settings shown in Table 1. The SEP co-management committees will design all interventions to restore and maintain the quality and quantity of future desired conditions for each of the physical landscape types and settings based on a foundation of guiding principles published in the comprehensive land use plans and designed to promote ecological integrity, social equity, and human well-being.

4.6. Guiding Principles

The SEP councils and committees will develop and recommend, and in some cases prescribe, specific guiding principles for management and define low-, medium-, and high-intensity uses (Table 1). The local and regional SEP co-managers will solicit input from the governmental agencies and all partners involved in the SEP to develop and publish four sets of tools called landscape guiding principles (LGPs) for managing physical landscapes (3 within-LGPs and 1 complete-LGP). The three within-LGPs (i.e., developed, agricultural, and natural) will provide unique principles for high, moderate, and low management intensities for each landscape type. The result will be three published sets of principles having nine sections each. The fourth set of LGPs will be called the complete-LGP and will be applicable to all physical landscape types. The complete-LGP will describe and map future desired conditions designed to:

- Describe the core values of ecological integrity, social equity, environmental justice, and the underlying principles the co-managers will apply to ensure these values are upheld. The SEP could use the iCASS Platform as a model to design stakeholder engagement and build trust [21].

- Provide a description of how the SEP was founded and how it is protected and maintained by LGPs and the agencies and participants of the SEP that developed them.

- Describe the nine physical landscape settings that should each occupy roughly 11% of the total United States land area.

- Provide landscape diversity ranging from urban to rural backcountry wildlands.

- Emphasize the need for secondary boundaries to be carefully arranged and interwoven to ensure relatively easy but regulated movement and access for everyone.

- Document how the SEP co-managers and the comprehensive plans considered and incorporated appropriate scientific and indigenous knowledge and relevant data into decisions. The co-managers could apply science capacity and data sharing practices developed by the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives Network [35].

The LGPs will be maintained through an officially recognized website and other media forums available to agencies, tribes, NGOs, and the public. The LGPs will be published in the comprehensive land use plans for each ecoregion, allowing the principles to be revised and updated as necessary when plans are periodically updated.

5. Benefits, Outcomes, and Challenges

The proposed SEP approach to landscape planning, designation, and co-management will increase the quality of life for people, reduce economic waste, improve ecosystem services for people, and maintain populations of native flora and fauna for generations to come. The time has come to plan for and organize our land uses to improve our quality of life and well-being in the United States. Our natural resources have suffered tremendously from ambivalence, lack of vision, and an overwhelming societal focus on single-resources such as air and water quality alone, endangered species alone, or soil erosion alone, as well as other single-issue initiatives such as zoning for detached, single-family housing.

5.1. Benefits for Developed Landscapes

Urban planning under the SEP will provide a forum for better and more inclusive communication and cooperation in urban development, giving attention to long-lasting functionality, durability, aesthetics, and appeal. The SEP will use deliberative democracy and participatory planning when addressing contentious issues such as urban sprawl, the pros and cons of smart growth, affordable housing, housing availability, and city zoning laws [12]. The SEP will emphasize public deliberation to work through these controversial issues to create political legitimacy and willingness to abide by decisions reached through inclusiveness, mutual respect, and meaningful dialogue. All parties to these discussions will have equal standing to defend and critique arguments during urban planning. This approach will account for past and present issues of inequity and environmental injustices and lessen the reliance on decisions made by voting on heated political referenda, the manipulation of voter districts, and city zoning strategies that exclude certain groups of people and drive up housing costs and displace residents.

The SEP will offer city officials opportunities to set boundaries for the designated land uses of cities, towns, and suburban areas. The SEP will focus on the benefits for people who live in developed urban areas. Citizens should be more able and pressed to focus on careful planning for building concepts and the design and construction of housing and commercial areas for increased quality of life. Ideally, the SEP co-managers, working closely with city and county officials, will be able to plan for DL and settings to reconcile the benefits and disbenefits of smart growth approaches such as limiting the impacts of urban sprawl, not exacerbating its impacts [12]. The SEP will accentuate the benefits of smart growth while mitigating or eliminating its adverse impacts. This will also lead to less economic waste in the long term if population densities and related transportation issues can be reconciled by improved urban planning and management.

People will have improved quality of life via reduced commute distances and travel times from home for work, food security, and pleasure visits with each other. The SEP will provide new access and improve existing access to natural places for pleasure, outdoor recreation, socializing or solitude, and tourism closer to home. People will have increased opportunities for improved human health directly with more walkable communities and indirectly with less environmental costs of transportation. The SEP is designed to achieve better connectivity within and across landscapes, which will provide more people with access to AL and NL. People will have direct views of scenic agricultural areas and taller-statured or elevated natural landscapes from home and work and while commuting. People will be more familiar with agricultural and natural landscapes without crowding them and will have designated areas for manageable access to them.

5.2. Benefits for Agricultural Landscapes