Abstract

Driven by many factors, the housing affordability landscape in the United States (U.S.) is in crisis. This research examines the potential role of inclusionary zoning (IZ) policies as a tool to alleviate housing cost burdens and deliver affordable housing in the rapidly growing southeastern region of the U.S., with a specific focus on Greenville County, South Carolina. Utilizing data from LawAtlas, this study first conducts a policy scan on the state of IZ policies across seven comparable jurisdictions. This study further employs qualitative semi-structured interviews with stakeholders to assess the current challenges to affordable housing in the county. Our findings suggest that growing regions such as Greenville County face unique challenges as they strive to meet the growing demand for affordable housing that serves a wide range of community members. A major finding from interviewees includes a need for more localized and nuanced metrics of housing affordability, greater density, and mixed-use development. However, the county faces challenges for such developments due to NIMBYism and preference for a more traditional rural and suburban typology of housing in the county. Finally, our study finds that zoning policies that enhance the supply of affordable housing by design can promote equity, trust, economic growth, and quality of life.

1. Introduction

There is evidence that the housing crisis in the United States continues to grow, and the results are widespread, with negative downstream impacts for individuals, families, communities, states, and the nation. Rental prices continue to rise and outpace inflation, and mortgage rates continue to be at the highest levels in several decades, with over 30% of US households experiencing financial burden due to the high cost of housing. The US Census Bureau reports that more than 21 million households are cost-burdened or rent-burdened, meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on rent, mortgage payments, or other housing costs [1,2,3].

The home affordability crisis impacts both owners and renters, with some racial groups impacted disproportionately by rising costs. The Census Bureau also reports that the percentage of Black and Hispanic households that pay more than 30% of their income on housing costs is, respectively, 6.5% and 3.5% higher than the 49.7% of the total population that is housing cost-burdened. Further, approximately one-third of black households were “severely cost-burdened”, spending more than 50% of their income on housing costs in 2023 [4,5].

Housing is a human need, such that the United Nations (UN) argues it is a human right and is a core component of several of the UN Sustainable Development Goals [6]. As such, when people struggle to find it, have it, and hold on to it, there are profound consequences for our communities. These consequences can have immediate and generational multiplier effects on individuals, groups, and communities. For instance, Gaylord et al. [7] reported that children who experienced residential change or housing instability more than three times before age seven had significantly more thought-and-attention-related challenges when compared with children who experienced less than three residential changes before age seven. Impacts could also include poor mental and physical health, educational delays, and generally delayed development.

Where children live is also strongly correlated with whether they will experience poverty in the future or not because of the potential generational impact of housing and neighborhoods on children’s long-term economic, educational, and health outcomes [8,9,10]. It could be inferred from the findings that the poor health status of adults in low-income households due to poverty, low educational attainment, and poor housing quality could also reduce the children’s present and future income, educational attainment, economic opportunities, wealth, social support, and health outcomes and perpetuate intergenerational cycles of poverty and poor health. However, inclusionary zoning policies have been shown as one of the land-use policy tools that could be instrumental in addressing affordable housing challenges.

While the current affordable housing crisis reaches all regions of the U.S., there is still a gap in the literature examining these challenges and their impact on traditionally rural and mid-sized cities undergoing rapid demographic and economic transformations. For such regions, the challenges of affordability of housing are further impacted by land-use policies, limitations of incentives for developers, and a housing market that tends to favor higher-end, detached, and visually suburban or rural housing typologies. It also cannot be overstated that much of the issues centered around housing affordability in the literature has mostly focused on large metropolitan or urban areas, leaving a significant gap in understanding how smaller, fast-growing regions are addressing the intersection of rapid population and socioeconomic changes, as well as the limitations of current land-use policies that cannot best address affordable and equitable housing that serves the diverse needs of communities in these regions.

We believe that this study fills this gap by examining affordable housing challenges in relation to land-use policies—specifically inclusionary zoning practices—and community planning in the rapidly growing Greenville County in South Carolina. The research applies qualitative methodologies; first, it employs a policy scan that utilizes LawAtlas data to conduct a comparative analysis of current trends in inclusionary zoning policies across jurisdictions in the region. Second, a semi-structured interview protocol is employed that involves interviews with local government officials, planners, and key stakeholders engaged in housing and community development within the County. Through these methods, this study allows a broader policy context and localized insight into the practical realities of implementing and responding to the challenges of affordable housing in the larger context of this pressing basic human right problem.

As stated, this study is significant due to the rising housing costs and demand for affordable housing in the region. Hence, local governments are increasingly being challenged to implement policies that balance growth and inclusivity, while maintaining the historical characteristics of communities. By focusing on inclusionary zoning—a key but often politically complex policy tool in practice—this study also sheds light on how policy mechanisms can be used or are constrained in shaping affordable housing outcomes. The study provides both a comparative policy perspective and context-specific insights from those directly involved in areas that are directly related to affordable housing. Through the first-hand experiences of a region often overlooked in the general housing policy literature, this study contributes to a more inclusive understanding and offers practical guidance for other similar communities attempting to promote more equitable development related to the ever-evolving housing policy paradigm.

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Affordable and Low-Income Housing Programs in the U.S.: An Overview

Housing accessibility and affordability problems among low-income households in the United States have been matters of concern for more than a century. The federal government did not participate actively in the provision of affordable housing to low-income households until the passage of the Housing Act of 1937. The federal government spends billions of dollars on housing programs annually, but most of the fund goes toward subsidizing homeowners through the tax code and not renters. The government has implemented different low-income housing assistance programs since 1937 until now. Affordable housing programs in the US can be grouped into three categories, namely, rental assistance, homeownership assistance, and land-use and regulatory incentives. The low-income tax credit (LITC) and housing vouchers are examples of rental assistance programs meant to encourage the supply and maintenance of quality and affordable rental housing stock for low- to moderate-income households [11].

Homeownership assistance programs, on the other hand, are intended to increase homeownership by subsidizing the production and rehabilitation of for-sale housing and providing low-interest loans, homeownership counseling, and down payment assistance to prospective homeowners. Land-use and regulatory programs, comprising the third category of affordable housing programs, involve land-use and regulatory initiatives that incentivize or mandate affordable housing by providing guidance to private developers on the location, characteristics, and cost of affordable housing developments through tools such as local land-use regulations and building codes, inclusionary zoning regulations, and smart growth initiatives [12,13].

1.1.2. Land-Use Policy and Affordable Housing

American zoning laws were first comprehensively implemented in 1916 in New York City, originating from German slum prevention efforts of the late 19th century [14,15,16]. Stakeholders identified zoning as a means of controlling market competition and safeguarding investments in the 1920s [16]. Laundries were mandated to be situated on a specific side of a town in the 1880s in a small Californian city, marking the earliest instance of zoning used to categorize land-use activities. Since their inception, zoning regulations have addressed various community requirements and preferences across the United States, even when these policies have been discriminatory, inequitable, and resulted in unsafe conditions for some communities. Some have argued that these policies originated, in part, as a reaction to the disorderly conditions brought about by the industrialization of our cities and the explosive expansion of residential areas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries [17].

Specific zoning regulations were meant to maintain distinctive qualities of communities, but they also increased housing costs and disadvantaged minorities by separating and essentially segregating neighborhoods along racial lines. Exclusive-use zoning laws were primarily used in Southern U.S. cities and restricted certain areas to commercial or industrial uses. These laws effectively kept impoverished minorities out of more affluent areas and lowered the value of homes and the standard of living in minority communities that already existed [16,17,18,19,20].

In the nineteenth century, even before American cities began instituting zoning laws, there was a preference towards the development of single-family homes, no matter how modest. However, over time, the preference for single-family zoning became embedded in city and state policy environments. Single-family zoning is decried as a tool of segregation, discriminatory against specific populations and socioeconomic groups and contributing to suburban sprawl across the country. The post-WWII housing boom is where single-family zoning made its lasting impact. Many Americans fled to the suburbs to get their piece of the so-called American dream, with a single-family home, white picket fence, and a yard. This boom occurred with considerable loan guarantees and subsidies from the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Veterans Administration (VA). At the same time, these developments, often with approval and outright support, often excluded Black and Jewish Americans, among others. This set in motion persistent policies that fostered racial, religious, and socioeconomic segregation. Even after the 1968 Fair Housing Act, which prohibited discrimination in real estate transactions, city officials around the country began to embed single-family zoning preferences into municipal codes to ensure that they remained [21].

Many of the zoning regulations that have evolved in the United States are exclusionary in nature. Exclusionary zoning is reported to cover 75% of land in American cities and is a constraint to the housing supply; it increases housing costs, limits economic diversity in cities, towns, and metropolitan areas, and slows racial economic mobility [22]. In general, there are two distinct zoning approaches, each with very distinct objectives and results. A zoning policy is a set of codes, laws, or regulations that govern how land in a municipality or zoning district can be used [23]. A local land zoning policy can be exclusionary or inclusionary. An exclusionary zoning policy (EZP) is a local land-use policy that effectively prevents low-income households from finding affordable housing [24]. An inclusionary zoning policy (IZP) is a local land policy that mandates or incentivizes estate developers to set aside a percentage of newly constructed housing units to be affordable to low-income households by selling or renting them to low-income households at below-market prices [25].

Historically, many exclusionary zoning practices were direct and intentionally exclusionary or discriminatory. However, exclusionary zoning can be and today is more subtle than past practices but may still result in inequitable outcomes for some groups. Exclusionary zoning is often justified as a way to protect property values, even though it also may prevent lower-income residents from being able to afford living in a particular area [17,20].

The prohibitive cost of housing is one of the socioeconomic problems impacting millions of Americans, but studies have shown that inclusionary zoning could be an important tool to address this problem. For example, Choi et al. [26] showed that zoning policies impact home affordability and have a role in land-use regulation. They reported that strict zoning and land-use regulations substantially raised the prices of low-tier homes compared to high-tier homes from 2000 to 2019. They showed that restrictive zoning often inhibits the availability of apartments and other lower-cost housing, maintaining a supply shortage and ensuring low quality in the available housing stock. Their findings showed that home prices in the lowest 20th percentile of the housing market increased by 126% while prices in the top 20th percentile increased by 86% across Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) between 2000 and 2019, but price appreciation also varies substantially across MSAs. They also reported the following:

“We find that in MSAs with higher employment growth, stronger zoning and land-use regulation, and less land available for development, prices for low-tier homes have increased more than for high-tier homes. The investor share and its growth in the home transaction market is not associated with the price growth rate differences between low-tier and high-tier homes. The relatively greater increase in housing costs for low-income households has caused residual income inequality (household income minus housing costs) to increase more than income inequality. Additionally, because MSAs with lower home price growth rates also experienced lower employment growth, housing cost burden and residual income inequality increased at a similar level across most MSAs.”[26] (p. 5)

In many municipalities, restrictive zoning limits even apartments or lower-cost multifamily housing options, keeping a supply shortage and reducing the levels of quality for available housing today. Reforms should aim to bridge the affordability gap because this divergence results from a limited supply and high demand.

From an international perspective, a comparative study of the U.S., Canada, England, Ireland, France, Spain, and Italy suggests that inclusionary zoning (IZ) is an excellent tool that prevents segregation and promotes social and geographic integration [27]. Reports from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) also suggest that IZ can increase the supply of multi-family housing units and make housing more affordable to low-income households [28]. Municipalities in Canada with a high land regulation index are also reported to have low housing affordability, while those with a low land regulation index have more affordable housing units [29]. In this case, a high land regulation index is comparable to exclusionary zoning, while a low land regulation index is comparable to inclusionary zoning.

One of the arguments against IZ is that it can constrain the overall housing supply and increase house prices [30]. However, this may be addressed by ensuring that the design of the IZ policy aligns with the local market conditions and the local contexts, since the effectiveness of IZ is reported to depend on local market conditions and the specific design of the IZ.

1.1.3. Explanation of Exclusionary and Inclusionary Zoning Policies

Common examples of exclusionary regulations include “minimum lot size requirements, minimum square footage requirements, prohibitions on multi-family homes, and limits on the height of buildings” [31] (p. 3). Lot size requirements in exclusionary zoning prevent the development of small houses on small lots, reduce the supply of available land, increase the cost of housing by making the purchase of larger lots mandatory, and limit the access of low-income households to quality and affordable housing. It also contributes to an increase in property values and pushes low-income households into areas with concentrated poverty. In addition, the cost of a piece of land is reported to be about 21.5% of the total purchase price of a single-family home [32,33,34]. This inadvertently creates an affordability problem for low-income households that may desire to buy houses or a rent burden problem for low-income households that are renters. In summary, exclusionary zoning policies are shown to affect low-income groups disproportionately; widen income inequalities and socioeconomic gaps; inhibit the access of low-income groups or households to affordable housing; segregate people by income, race, and ethnicity; contribute to environmental problems; perpetuate segregation; and impact housing rent, wages, and the economic opportunities of labor negatively [35,36,37,38,39].

On the other hand, inclusionary zoning describes zoning regulations that mandate or reward the incorporation of affordable housing in new construction projects. Inclusionary zoning aims to foster economic diversity and expand the supply of affordable homes in a particular location and can include a number of different elements [17,20,40]. Inclusionary zoning policy (IZP) implemented at the local housing authority level increases the spatial concentrations of affordable housing units and is effective when targeted toward low- to moderate-income households. It serves as an affordable housing tool used to reduce exclusion and racial segregation and increase racial and economic equity for minority groups [25,41,42]. Policies regarding inclusionary zoning by Wang and Balachandran [43] are highly instrumental in the creation of affordable housing opportunities that will be supportive of socioeconomic integration.

IZP can be mandatory or voluntary. The voluntary option gives real estate developers the opportunity to pay fees to affordable housing funds, donate land in lieu of building affordable units, or provide units off-site. The mandatory option requires developers to set aside a fraction of housing units that are affordable for low-income households. IZP can also have different set-aside requirements, affordability levels, and control periods. The incentives they offer to estate developers include density bonuses, expedited approval, and fee waivers.

Inclusionary zoning policies are usually targeted toward solving housing affordability challenges by requiring or incentivizing the inclusion of below-market units in development projects. Wang and Balachandran [43] reported that the implementation of more than 1000 IZPs across different jurisdictions in the U.S. over the years resulted in the creation of over 110,000 affordable units and the collection of USD 1.8 billion in fees for affordable housing development. For example, California and New Jersey have utilized state laws to extend program acceptance and efficiency.

Finally, it is important to note that the current housing policies in the US are diverse across federal, state, and county governments. Federal low-income housing programs are reported to have only helped about 25% of eligible households, with federal funding for affordable housing declining over the years. States, counties, and cities have also implemented many affordable or low-income housing programs, but these have not been adequate for meeting the growing housing accessibility and affordability needs.

However, their effectiveness at addressing affordable housing problems can be influenced by their design and a city or municipality’s market characteristics and context [44,45]. In fact, there are scholars who argue that inclusionary zoning or broad changes to zoning will not be enough to increase the supply of housing to offset the affordability crisis we have today [30,46,47]. For instance, Choi et al. [26] show that, in the absence of restrictive zoning, a supply shortage exacerbates the issue of housing scarcity, leading to a disproportionate increase in prices for low-quality homes.

1.1.4. Producing Affordable Housing in Rising Markets: What Works?

Many urban households face high rent burdens despite the implementation of inclusionary zoning and statewide “fair share” laws. The impacts of the policy and laws have been minimal and inadequate for offsetting the effects of increasing housing costs. The investment in and development of market-rate housing in low-income neighborhoods have also contributed to increased rent burden among low-income households, gentrification, and worsening housing accessibility and affordable problems. Gentrification, on the other hand, has had negative ripple socioeconomic effects on individuals and cities at large. Therefore, solving the affordable housing crisis requires a multifaceted approach that combines policy innovation, community engagement, and sustained funding efforts to create and preserve affordable housing in high-opportunity areas [48].

1.1.5. Governance Challenges in Housing Policy

The U.S. housing policy governance will encounter several challenges, including decentralized authority and fragmented responsibilities across federal, state, and local levels of government. Willison [49] asserts that increased political devolution and a “submerged state” lead to conflicting policies, reducing accountability and transparency. He further explains that these various governance challenges impede the effective implementation of housing policies, and further reduce health outcomes. Great governance strategies, such as the TAPIC framework, which focuses on transparency, accountability, participation, integrity, and capacity, are necessary to ensure better policies on housing and health.

1.2. The Setting—Greenville County, South Carolina

This section provides a general socio-economic overview of Greenville County using U.S. Census data and utilizes ArcGIS Pro version 3.2 software by Esri to create maps for visual representation of data. In the past two decades, Greenville County has undergone significant population and demographic changes (Table 1). From 2000 to 2020, the county’s population increased by a remarkable 245.1% from 149,556 to 516,126, respectively. Greenville County is currently the largest county in population in the state of South Carolina. Historically, the county was predominantly White, who made up 78.2% of residents in 2000; it has now been experiencing significant changes in the population in the past two decades, with a shifting race and ethnicity makeup. However, while they continue to be the majority, the White population has steadily decreased to 70.3% in 2010 and 67.7% by 2020. During the same period, the population has seen an influx of new minority groups moving into the county. Notably, the Hispanic/Latino population has had a significant growth, increasing by 6.8% between 2000 (2.6%) and 2020 (9.4%). While not as pronounced, the Asian population has also slightly grown, albeit by a smaller 2.4%. Additionally, the Black population in Greenville County stayed the same between 2000 and 2020, comprising 17.1% and 17.3% of residents, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographics in Greenville County in 2000, 2010, and 2020 by race and ethnicity (source: U.S. Census) [50].

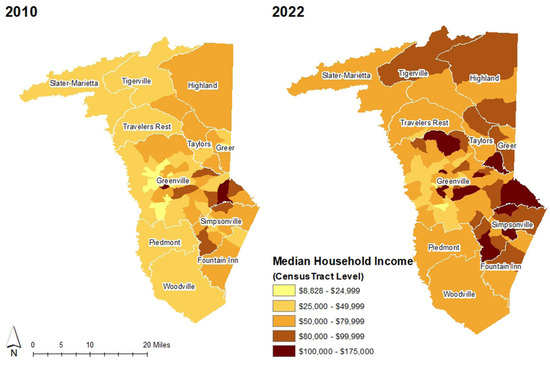

From an economic standpoint, Greenville County has experienced steady growth over the past decade. The median household income increased from USD 45,666 to USD 71,833 between 2010 and 2022, respectively (Figure 1). This growth is the result of the capital investments the county has made over the last years. According to the Greenville Area Development Corporation, between 2016 and 2020 alone, Greenville attracted more than USD 1.96 billion in new business investments, creating over 9505 new jobs in the County. As of 2020, the largest employers are Prisma Health and Greenville County Schools, each employing over 10,000 across the county. They are followed by Michelin North America, Inc. (5001–10,000), Bon Secours, and Duke Energy, with 2501–5000 employees each in 2020.

Figure 1.

Median household income 2010 and 2022 at the census tract level (source: U.S. Census) [50].

Utilizing U.S. Census American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimate data for 2022, Table 2 presents the median household income comparatively between the U.S., South Carolina, and Greenville County by race and ethnicity. As of 2022, the median household income in the county was USD 71,328, a difference of USD 7705 more than the state average but USD 3821 less than the median for the country. This is a reflection of Greenville County’s position as the economic center of the state of South Carolina. Nationally, the median household income for White households stands at USD 80,042. South Carolina’s figure is lower at USD 73,204, reflecting the state’s broader economic challenges. However, Greenville County median incomes tend, in most cases, to exceed state levels and are close to reaching national levels, but wide race disparities are present, with American Indian/Alaskan Native, Black, and Hispanic/Latino families earning well below White families, as well as Asian families, highlighting continuing economic disparities requiring policy responses.

Table 2.

Median household income in the past 12 months by race/ethnicity in 2022: inflation-adjusted dollars (source: U.S. Census) [50].

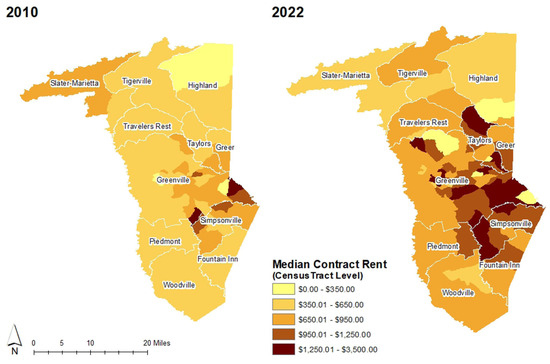

The upward growth in population and income, while positive in many ways, comes with trade-offs and concerns related to equity and wealth disparities within populations. The number of housing units in Greenville County has increased year over year and over the 12-year period between 2010 and 2022, and it grew by 19.4%. Similarly, the increase in renter-occupied units and median rental costs have risen over the period by 24.1% and 63.8%, respectively. Finally, the percentage of individuals and families who are rent burdened has continued to increase in the county and has risen by 30.2% since 2010. The increase in rental costs and rent-burdened households has outpaced the growth in the number of housing units in the county. This hints at potential housing scarcity, especially for low- and middle-income families that have a higher likelihood of being renting households. In 2022, There were 61,485 renter households in Greenville County, paying a typical median rental cost of USD 1121 a month (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Median contract rent 2010 and 2022 at the census tract level (source: U.S. Census) [50].

2. Materials and Methods

This study will employ a qualitative research design to address the question of what the current policy landscape is currently as it relates to inclusionary zoning and housing regulation in Greenville County and a sample of US cities. The qualitative approach will utilize both a policy scan and document analysis to characterize the landscape of inclusionary zoning policies in the region. At the highest level, a policy scan is essentially a survey of the existing policies within a particular area of interest. The purpose is often used to identify existing policies in a particular area to inform the current and future policy and advocacy environment.

A policy scan examines and describes the broadest mix and range of policy instruments that may influence the policy environment of a specific issue [51]. In this way, it is designed to describe the wider regulatory and policy environment around a specific issue. Using a policy scan as a method of analysis requires a review of policy instruments to identify both the positive and negative impacts on a specific policy landscape. The strength of this method is also influenced by its ability to examine the chain of policy instruments and the hierarchy of laws, regulations, and policy tools. This method also allows the researcher to contextualize the policy environment with the relevant external and/or internal political pressures.

From a detailed methods perspective, a policy scan systematically gathers and analyzes policies in a particular area of interest. This tool has the benefit of being useful for policymakers and researchers, as this approach uses an “applied” lens to capture the wider policy and regulatory environment at local, regional, and national levels. For the purposes of this analysis, the study sample included all relevant planning and zoning documents for Greenville County, the City of Greenville, and other municipalities in the county. However, the research focused on the City of Greenville rather than other municipalities in the county. The City of Greer, Simpsonville, Travelers Rest, Fountain Inn, and Mauldin did not have any inclusionary zoning ordinances. The City of Greenville’s planning documents were compared against matched Southeastern U.S. cities for inclusionary zoning themes. We downloaded the zoning ordinance/code and read through the texts to determine if there are identifiable inclusionary codes or if specific codes address inclusionary issues. We then used the LawAtlas code book to code the local zoning codes of each municipality.

The LawAtlas policy surveillance program provides clear guidance on how to code and generate data from local-level inclusionary zoning laws through their defined research protocol and code book for local inclusionary zoning laws. This program’s significance lies in its ability to ensure the credibility and reliability of the data used in this research assessment. The LawAtlas has forty questions for coding local inclusionary zoning law. We coded these questions for the six municipalities and Greenville County. However, it is important to note that the local law or policy being coded must be inclusionary for the research protocol and the codebook to be applicable.

2.1. Case Study Jurisdictions

To provide a more robust context for this research, the team developed several short case comparisons of cities in the region. We first obtained a dataset for 1068 jurisdictions that have adopted some type of inclusionary zoning policies from the Grounded Solutions Network. A total of 68 jurisdictions in the southeast region of the US, where Greenville County and South Carolina are located, were selected. The southeastern states in the dataset were Florida, Texas, Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Jurisdictions in North Carolina and Georgia, the two states that share borders with South Carolina, were then selected. North Carolina has seven jurisdictions with inclusionary zoning, while both Georgia and South Carolina have two. Demographic similarity comparisons in terms of population, median income, and median rent were conducted, and seven cities or towns that are demographically similar to the city of Greenville were selected. These were Carrboro, Davidson, Asheville, Chapel Hill, and Durham from North Carolina, Decatur from Georgia, and Charleston and Greenville from South Carolina. Additionally, utilizing a regional perspective also helped define interview questions. Table 3 presents the socioeconomic and demographic descriptive statistics of the jurisdictions included in this study.

Table 3.

Case study jurisdictions descriptive statistics (source: American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates 2022) [52].

2.2. Interview Qualitative Study

Second, to provide a more holistic perspective of the policy scans, an exploratory semi-structured interview protocol was conducted with seven high-level government officials in Greenville County who work in areas of planning and housing development or hold administrative positions. To enhance the validity and reliability of results, a purposive sampling strategy was employed, targeting local and county-level officials with direct responsibilities related to housing policy. This aligns with the study’s main focus, which is to capture government-level perspectives from those directly involved in housing decisions at the local and county levels. Participants were recruited utilizing local and county government websites to identify key individuals at agencies. Once identified, participants were recruited through electronic email correspondence.

The qualitative methodology employed is a deductive thematic analysis that utilizes a set of pre-determined themes in the interview question protocol. The questions utilized were informed by the literature and findings from the case study analysis. The themes included the following: perception and definition of affordable housing; challenges to the development of affordable housing; inclusionary zoning and affordable housing; community resistance to affordable housing; and future outlook (5–10 years) on affordable housing.

All interviews were conducted remotely using Zoom version 6.1.10 (56141) conferencing platform. Interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent and transcribed verbatim for accuracy. To analyze interviews, we applied the themes as a framework to identify key and relevant segments of the interview transcribed data. Next, we coded the data according to themes, while also highlighting significant statements that relate to and exemplify each theme. We reviewed and refined the coding protocol to ensure accuracy and consistency among all interviews. We then analyzed relationships and patterns across and within themes, which facilitated insights that are meaningful and add to a better understanding of our findings.

It is important to note that the limited number of interviews is a reflection of one component of a larger ongoing research project that encompasses a significantly greater number of participants across five additional counties in the upstate region of South Carolina. However, while limited in scope, Greenville County is one of the fastest-growing counties in the region, and these interviews provide valuable perspectives that help lay the groundwork for a broader analysis that will be forthcoming in future research. The broader project will offer a more comprehensive understanding of the socioeconomic and housing trends, challenges, and policy responses, both in practice or those being considered to address these issues at the regional scale.

3. Results

3.1. Inclusionary Zoning Review

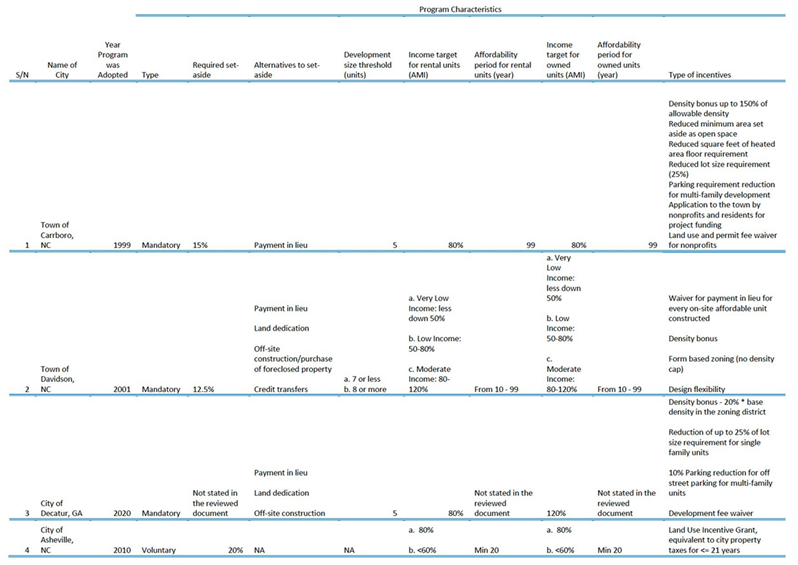

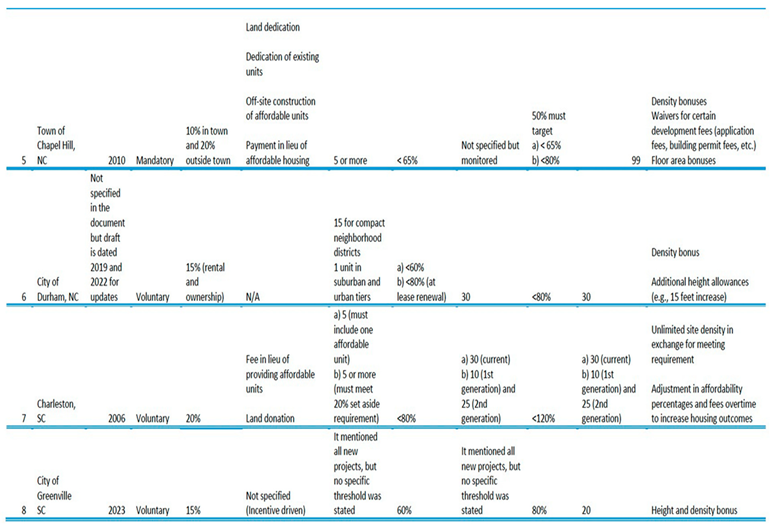

Inspired by the criteria from the LawAtlas, a detailed inclusionary zoning policy scan was completed for each of the communities. The primary categories for review focus on the year of adoption, program type, required set asides, alternatives to set asides, development size threshold, income target for rental and owned units, affordability period for rental and owned units, and incentive types. Each of these categories is identified as a key variable to understanding the community priority and the scope and breadth of inclusionary zoning. A comprehensive summary table of findings is also provided in Appendix A.

3.1.1. Year of Adoption

From a policy perspective, the year of program adoption signals several important things for communities, policymakers, and applied researchers. In general, it may signal policy entrepreneurship, innovation, and leadership around a specific policy problem. As such, the longer a community has been actively engaged around a specific issue, the more experience they may have with the best practices in managing, improving, or preventing challenges related to a particular problem. While the year of adoption is important, it does not tell us why a community felt the need to adopt a policy or what the stressors, opportunities, or incentives may have been. This is another important piece for future investigation. The year of adoption of inclusionary zoning varies substantially among the sample jurisdictions. The earliest adoption among the sampled jurisdictions was 1999 in the Town of Carrboro, North Carolina, while the latest was in 2023 in the City of Greenville, South Carolina. The impacts of the policy on affordable housing are therefore expected to vary across jurisdictions based on the time horizon. There are also between and within-state variations in adoption rates.

The Town of Carrboro, NC, adopted an inclusionary zoning program in 1999, while both Asheville and Chapel Hill, NC, adopted theirs in 2010, eleven years after Carrboro’s adoption. The City of Charleston adopted a policy in 2006. Based on this and other policy examples, cities and towns in North Carolina appear to be earlier adopters than their counterparts in the border states of Georgia and South Carolina. Irrespective of the variations in the year of adoption, the fact that the City of Greenville included inclusionary zoning guideline in the 2023 Development Code reflects the impact and the importance of ongoing research, discussions, and the realities of housing situations in the US. It further reflects the role that inclusionary zoning policy is expected to play as part of the solution to housing affordability challenges.

3.1.2. Program Type

The program type will depend on a state’s statute on inclusionary zoning, each city and town’s economic characteristics, and the overall housing market landscape. Some states preempt counties from passing inclusionary zoning policies, while some only preempt mandatory policies but leave room for voluntary policies. States with inclusionary zoning statutes may give communities more room for the types of policies and programs they can implement. Depending on the state statute, these policies may have to be voluntary at the city or county level. Studies have shown that mandatory policies appear to be more effective at producing affordable housing units than voluntary policies [53,54]. However, it may still be better to have a voluntary program than to have nothing at all.

The program type varies among the jurisdictions. In North Carolina, the three sampled towns have a mandatory inclusionary zoning policy, while the two sampled cities have a voluntary inclusionary zoning policy. Mandatory zoning in North Carolina is reported to operate in a “legal gray zone”. This means that the state’s constitution and statutes do not grant counties express power to enact inclusionary zoning policies, but the towns are reported to have authority to regulate where buildings are located and their usage [55]. This may explain why the three sampled towns in North Carolina passed mandatory programs while the two cities passed voluntary programs; the Town of Carrboro, Town of Chapel Hill, and Town of Davidson, NC, have mandatory programs, along with the City of Decatur, GA. Decatur’s mandatory program further implies that Georgia’s statute does not preempt a mandatory program at the local level. Charleston, SC, and the City of Greenville, SC, have voluntary affordable housing programs.

3.1.3. Required Set-Asides

This is one of the most critical components of inclusionary zoning policy. It stipulates the number of housing units that are to be set aside by developers as affordable in new development projects. It is usually expressed as a percentage of the total units to be constructed. It ranges from 10% to 20% among the sampled jurisdictions. Asheville, Chapel Hill (outside of main town), and the City of Charleston have set-asides of 20% each; the Town of Carrboro, Durham, and the City of Greenville have 15%, and Davidson has 12.5%. However, the set-aside was not specified in the documents reviewed for Decatur. The lack of a specific set-aside in this jurisdiction may reflect the dynamics of the local economy, housing markets, and the nature of the support and/or opposition for inclusionary zoning or affordable housing efforts. Without a specific implementation goal for communities and developers to reach, the success of these policies and the potential expected outcomes are circumspect.

3.1.4. Alternatives to Set-Asides

A few communities outline alternatives to set-asides that may also support affordable housing goals. The number of alternatives to set-asides also varies across jurisdictions. For example, payment in lieu is one alternative that cities and developers use in place of set-asides. Payment in lieu is a fee developers can pay to the jurisdiction for its selective use instead of building the required number of affordable units as part of their project. Payment in lieu was the only alternative found in the Town of Carrboro, while the Town of Davidson has payment in lieu, land dedication, off-site construction, and credit transfers. The City of Asheville, Durham, and the City of Greenville did not specify alternatives to set-asides in their documents. These variations are also likely reflections of local contexts and dynamics in the design of inclusionary zoning policies. Some jurisdictions may be more supportive of specific types of development policy and methods for achieving affordable housing goals in comparison to others.

3.1.5. Development-Size Threshold

This sets the requirements for the number of units developers intend to construct that will trigger the inclusion of affordable units. The minimum number of units is generally five. This means that any developer who intends to construct five housing units will be required to set one aside as an affordable unit. The City of Asheville and the City of Greenville did not specify this threshold.

3.1.6. Income Target for Rental and Owned Units

All jurisdictions set income targets for rental units based on their Area Median Income (AMI). Davidson has three income targets, making it the jurisdiction with the most comprehensive income targets among the sampled jurisdictions. It has less than 50% AMI for very-low-income, 50–80% for low-income, and 80–120% for moderate-income households. The remaining jurisdictions have an AMI from 60 to 80% as low-income targets. Affordable housing is a broad term, and affordability is widely relative. There are some growing conversations related to how to measure affordability and for whom, conversations that could result in a more nuanced definition of how to support the goal of ensuring that every individual and family can “afford” a place to live.

3.1.7. Affordability Period for Rental and Owned Units

The affordability period determines the number of years the set-aside units will remain affordable based on local market rates. It is 99 years for Carrboro, 10–99 years for Davidson, a minimum of 20 years for Asheville and Greenville, 30 years for Durham, and 10–30 years for the City of Charleston, the City of Decatur, and Chapel Hill. When the period of affordability is longer and more stable and secure, this provides potential residents. In contrast, the longer the affordability period, the more constraints there are on development and uncertainties related to community and market changes.

3.1.8. Incentive Type

Cities, counties, and states provide a wide range of economic development incentives; affordable housing is no exception. The type of affordable housing incentives offered to developers by jurisdictions varies by type and level of comprehensiveness. The Town of Carrboro has the most comprehensive incentives among all jurisdictions. These include a density bonus up to 150% of the allowable density, reduced minimum set-aside area as open space, reduced square footage of heated area floor space, reduced lot size requirement (25%), and parking requirement reductions for multi-family development. The Town of Carrboro also allows the following: applications to the town by nonprofits and residents for project funding; and land-use and permit fee waivers for nonprofits.

All jurisdictions have a density bonus as an incentive except Asheville. Asheville has a land-use grant, which is the jurisdiction’s only affordable housing development incentive. It is equivalent to the city’s property tax rate, which is less than or equal to 21 years. Other incentives across jurisdictions include development fee waivers, parking requirement reductions for multi-family units, reduction in lot size requirements for single-family units, design flexibility, and a waiver of payment in lieu. Overall, all jurisdictions have at least one incentive. This reflects the primary purpose of inclusionary zoning policies, which is to incentivize the supply of affordable housing units in ways that meet the needs of the local community and its characteristics.

The 2023 Development Code of the City of Greenville lacks specific alternatives to set-asides and a development size threshold. Given that this policy is new, there are opportunities for the city council to design additional policy measures in a more comprehensive way, with careful attention to current local economic housing market situations and contexts.

3.2. Interview Results

The following section presents preliminary findings from interviews conducted with key stakeholders who encompassed local government officials and other stakeholders in Greenville County.

3.2.1. Perception and Definition of Affordable Housing

A recurring theme across the interviews is the inadequacy of standardized definitions of affordable housing that meet the needs of local communities in Greenville County. Several of those we interviewed criticized the dominance of the official U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) matrix that defines affordable housing as occupants paying no more than 30% of the gross income or housing prices for those earning 80–120% of the Area Median Income (AMI). For example, one informant underscored that, in some communities, these measures do not translate into actual affordability for many members of the community, such as teachers and firefighters, suggesting that a focus on those earning closer to 50% AMI is a better matrix instead. While the HUD definition remains a useful baseline, several informants noted its limitations in addressing affordability for varying socioeconomic groups. For instance, some distinguished between “affordable housing” for lower-income groups and “workforce housing” for moderate-income earners, emphasizing that both are necessary components of a balanced housing market for the county.

The interviews also highlight the importance of contextualizing affordability to local economic conditions and workforce needs. Several of those interviewed emphasized the need for affordable housing options at every socioeconomic tier, including for people who hold essential but lower-paying jobs, with one stating the following: “We need affordable housing every place. It’s just that we’ve come to define affordable housing as a technical term for families with low income”. One participant stressed that affordable housing should be accessible for those who can “work a job, not necessarily a career, and still afford to live in a house”. Another pointed out that framing a USD 350,000 home as affordable, as seen in most areas of Greenville County, is entirely disconnected from the financial realities of most blue-collar and service industry workers.

Moreover, the findings point to the importance of education and awareness in shaping effective policies. The public’s misconceptions about affordability and housing costs were identified as a barrier to progress in this area. One of the participants interviewed stressed the need for decision-makers to be informed through the socioeconomic conditions on the ground in order to help them understand what affordability means in practice. This highlights the need for policymakers to move beyond official abstract metrics and engage with the lived experiences of community members, further revealing a need for a more nuanced, contextual approach in defining and achieving affordable housing in Greenville County.

3.2.2. Challenges to the Development of Affordable Housing

In Greenville County, one of the most persistent challenges identified is the rising cost of land and the construction of housing. Interviewees consistently noted that an increase in land values and rising material and labor costs significantly limit the ability to build affordable housing for developers. As one informant explained, “…with building prices going up the way they have, land values increasing, and significant changes in housing values in our area, it’s tough to create affordable housing”.

Whether in rural or urban settings, land availability for the development of affordable housing is another issue that was mentioned by those who were interviewed. Interestingly, another informant quipped that they are “…competing with investors from all over the country who come in from Chicago or LA, or wherever, and just buy up pieces of land and sit on it because they felt like Greenville was a hot spot and was going to grow. So, getting land is obviously a huge, huge challenge”. At the urban scale, it was noted that land acquisitions by large developers have driven up prices, making it difficult for affordable housing projects to secure suitable property. At the suburban and rural scale, several informants emphasized that this challenge is further deepened by infrastructure gaps, such as connections to sewer and water lines, which increase costs for developers. It was noted that this is often inadequately addressed by the local, state, or federal government, where there is a need for consistent support, particularly in addressing infrastructure gaps and subsidizing development costs.

Community resistance also emerged as a significant barrier, with several informants relating this issue to the prevalence of “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) sentiments. According to many of those interviewed, these feelings often stem from misconceptions about the impact of affordable housing on property values and potential traffic impact on the community. As one of our sources explained, “People often say, ‘we don’t want this development here because it might pull down the value of my house’”. However, most interviewees noted that such fears are often unfounded. Another barrier mentioned was the negative perceptions of housing typologies, such as attached townhomes and apartments. This limits the ability to create higher-density affordable options in certain areas. This resistance to diverse housing typologies was highlighted as a significant challenge, particularly in the suburban and rural areas of the county, which have traditionally preferred single-family detached homes. Finally, economic pressures such as inflation, rising interest rates, and fluctuating political support for affordable housing initiatives further exacerbate the problem. Informants noted that changes in political leadership often lead to shifts in funding priorities, creating uncertainty for long-term planning.

3.2.3. Inclusionary Zoning and Affordable Housing

A central theme across participants is the potential of increased density as a solution to housing affordability. All interviewees consistently emphasized that higher-density developments, such as townhomes, condominiums, and mixed-use projects, provide viable avenues for creating more affordable housing. As one city administrator noted, “In order to achieve affordable housing, you have to have density in the area. Townhomes and attached homes are probably our best avenue forward”. This view reflects a recognition that increasing the number of units per acre can reduce per-unit costs, making housing more accessible to diverse income levels.

However, higher-density housing is often met with resistance from communities; in particular, residents are concerned about maintaining the rural character of an area and exhibit skepticism toward zoning changes in rural or suburban areas. One interviewee explained, “Density makes things more affordable, but rural communities don’t want to sacrifice their character for regional housing markets”. This resistance can manifest as opposition to rezoning efforts or rejection to typologies like attached homes and manufactured housing, which are often stigmatized despite their potential in delivering affordable housing.

The interviews also revealed ongoing efforts to update and refine zoning laws to better accommodate affordable housing needs. In one rural community, for example, there is an initiative to rewrite zoning laws to balance increasing density with the preservation of local identity. Another interviewee described efforts to implement inclusive zoning practices through a Uniform Development Code, which would promote mixed-use and mixed-income developments. Overall, flexibility in zoning was identified as an essential policy tool for accommodating diverse housing needs while addressing community concerns.

Despite these initiatives, several of those interviewed noted significant challenges in securing widespread support for higher-density zoning. Pushback often arises from fears that increased density might negatively impact property values or alter the community’s aesthetic. Some informants also suggest that these barriers can be overcome through education, engagement, and a collaborative approach to demonstrating how density can coexist with the community’s long-term development goals.

3.2.4. Community Resistance to Affordable Housing

A significant theme across the interviews is the preference of many communities for maintaining the status quo. One informant noted that residents often want new developments to mirror existing homes and demographics, with resistance arising to anything perceived as different: “People just want to see the same type of homes they have go up and the same type of people move in. Anything else often faces resistance”. This sentiment underscores the social and cultural factors that contribute to opposition, which can be as influential as economic conditions.

Concerns about property values were frequently cited as a key driver of resistance. In suburban areas, fears that affordable housing might negatively impact existing home values often create significant pushback. One informant also highlighted how biases, including racial prejudices, can further complicate efforts to introduce affordable housing projects in certain neighborhoods, stating some pushback from communities had “…a racial element to it. ‘You’re going to bring those folks into our neighborhood?’”. However, the informant also pointed to successful examples where communities embraced affordable housing, suggesting that local context and proactive engagement can influence outcomes.

The importance of collaboration and education emerged as a crucial strategy to address resistance. Informants emphasized the need to involve residents early in the planning process to foster understanding and support. As one informant explained, “We need to set the table for development that aligns with the community’s needs and build consensus around affordable housing initiatives”. Another advocated for starting with small, pilot projects to demonstrate the benefits of affordable housing and educate both council members and residents: “I want to do it with our community, not to them”.

Proactive engagement with communities is also vital in overcoming resistance. Informants shared examples of building trust through open dialogue and addressing specific concerns raised by residents. For instance, one interviewee exemplified how initiatives in neighborhoods such as Sterling and Nicholtown illustrate how tailored communication and relationship-building can lead to successful affordable housing developments.

3.2.5. Future Outlook

Looking at what affordable housing may look like in Greenville County in the next five to ten years, a recurring theme was the need for localized solutions tailored to the unique challenges of smaller communities in regions that are currently experiencing population growth and housing shortages. As larger cities within the County, such as the City of Greenville, face capacity limits, smaller jurisdictions will play a more significant role in addressing affordable housing needs. One interviewee highlighted this shift, emphasizing that “this conversation will have to hit small city walls soon… but we’ll need solutions tailored to our unique challenges”. To facilitate this change, participants stressed the importance of educating policymakers and residents about the complexities of affordable housing, promoting a shared understanding of the issue.

The need for aligning housing development with local economic and social contexts was also identified as critical for future sustainable development. Reflecting on historical examples such as mill villages, one informant advocated for modern approaches that integrate housing with the economic landscape it serves: “Affordable housing has to tie to the commerce or industry it serves”. Additionally, showcasing successful projects, such as manufactured home subdivisions, was highlighted as a means to combat stigma and demonstrate the viability of alternative housing typologies.

Systemic issues, particularly poverty and wage disparities, emerged as underlying challenges that must be addressed to ensure long-term housing affordability. Without significant intervention, one informant warned, affordability issues will worsen for low-income families. They advocated for investments in education and skill development to improve income levels and create a more sustainable foundation for housing solutions.

Shifts in development patterns, such as a greater emphasis on multifamily housing, were also seen as likely in response to economic and land-use pressures. While some informants expressed optimism about government investment and market adjustments, they emphasized the urgency of prioritizing funding and policy changes to avert a deepening housing crisis. As one informant noted, “We have to get used to this conversation and have solutions that actually help people”. Overall, informants expressed an urgent need for communities and policymakers to develop local solutions and nurture community support for affordable housing programs. The issue is not improving in most communities, and with current regional economic and workforce conditions, it is only predicted to worsen.

4. Discussion

Greenville County has experienced remarkable population growth over the past several decades and continues to grow. It is currently the largest county in terms of population in the state of South Carolina. Greenville has achieved remarkable success in attracting new firms and capital investment in the region. From 2016 to 2020 almost 10,000 new jobs were created in the county. The median income and educational attainment have also increased over the decade, while poverty rates have declined. Overall, Greenville County is in a remarkably good socioeconomic position and often fares better than state averages and comes close to matching national averages in some cases [50].

The housing environment in Greenville County has been impacted by the many diverse factors facing similarly growing counties around the nation. With this said, the result of this research is largely focused on one county and region of South Carolina in southeastern United States. While affordable housing is a widely shared challenge, the characteristics of each community and the potential local solutions to affordable housing are arguably not widely generalizable. The number of housing units in Greenville County has continued to increase, along with substantial growth in the demand for rental units. Median rental costs have continued to increase, such that the percentage of individuals and families that are rent burdened has risen by 30.2% since 2010. Almost 50% (47.6) of Greenville County residents are rent-burdened, which is higher than the national average of 45.83%. Further, costs have continued to outpace the growth in housing units in the county, which has disproportionately impacted low- and middle-income families and renters [56].

Greenville County is experiencing housing affordability challenges similar to much of America. However, a lack of housing has critical downstream impacts on individuals and communities, creating short- and long-term challenges for individuals and the communities in which they live. The results confirm that zoning is an important part of a city’s and county’s toolbox, as it relates to the built environment and housing. Research confirms that policies like inclusionary zoning can be a valuable tool that facilitates more affordable housing in communities [25,41,42]. In 2023, the City of Greenville incorporated some inclusionary- inspired zoning measures, but it is too early to effectively determine the result of these policy measures. None of the other municipalities in Greenville County have any inclusionary zoning measures, although the county passed a Unified Development Ordinance (UDO) in the fall of 2024. The UDO is an effort to standardize zoning and development codes across the county. While zoning alone will not solve the affordable housing crisis, inclusionary zoning practices can support and incentivize the development of more affordable rental and owned units in Greenville County.

This research confirms several important key findings. One primary takeaway is that there is not one specific policy, regulation, or approach that will solve affordable housing. It is a complicated system that demands different solutions for every community. However, one similarity that Greenville and other communities all have is the need to have robust community engagement, public information sessions, and broad-based community dialogue on how to create local solutions to affordable housing. Developing community- and county-wide networks that build trust and support creative ideas and solutions will help open pathways for locally driven solutions. While these types of engagements require financial and time investments, they can be implemented with relative ease and in a timely fashion in collaboration with higher education, municipalities, and local partners.

Further, it is important for communities to consider the difference between mandatory and voluntary measures [3,44]. The findings from the reviewed studies suggest that it is possible that voluntary measures may be effective if the development incentives are valuable enough to incentivize developers; however, when this is not the case, it may be important for a community to consider mandatory policies if affordable housing is a priority. In addition to this, there is evidence that when states signal the support of inclusionary zoning measures through state legislation, there is a stronger use and focus on it from cities and counties. Framing the potential social and economic benefits of specific policies to local and state policymakers is a critical part of building a case for affordable housing. Non-profits and other community-serving organizations can serve as important resources for education, advocacy, and lobbying for policy change at the state and local levels. Working with community organizations to determine the prioritization of community needs can help determine whether and how best to inform public officials on these issues and advocate their solutions.

Another primary finding from the policy scan and interviews is the expressed need for the six municipalities in Greenville County to conduct a wide stakeholder engagement process to hear and make every voice and concern regarding equity in affordable housing and health count. Based on these results, county municipalities see the need for community conversations and engagement. The product of stakeholder engagement would ideally be a design of a comprehensive inclusionary zoning policy that takes the municipalities’ economic characteristics, the housing market situations, and the local context into consideration. Zoning policies that enhance the supply of affordable housing by design can promote equity, trust, economic growth, and quality of life.

Additionally, programs that empower low-income and underrepresented minority groups to improve their economic opportunities, access to health care, and quality education should also be combined with inclusionary zoning policy [57,58,59,60]. These could include targeted skill acquisition, workforce training, early childhood education support, and increased health insurance coverage. For example, in Greenville County, collaborating with Greenville Community College and the area’s employers in the development of targeted programming aimed at specific areas of the community, types of skills, and socioeconomic groups could provide additional value to affordable housing programs. Solving the affordable housing crisis for any community is complex and requires a unique set of approaches for each community. The relationship between housing and health risks and outcomes is an additional impetus for communities to consider more effective and timely housing solutions that improve affordable housing and housing security.

The results from interviews also highlight several significant challenges that align with the existing literature. First, as the literature suggests [3,4], stakeholders in Greenville County expressed that the current use of the US-HUD standardized definition of affordability metrics tends not to align with the socioeconomic realities of the region. Interviewees suggest that there is a need for more localized metrics that take into account the income distribution, housing costs, and evolving workforce needs of this region. Second, the rising costs of land, construction, and infrastructure gaps, particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, have become an impediment to affordable housing development [26]. Moreover, speculative land investment in growing regions such as Greenville County has further put pressure on housing affordability generally. Finally, as the literature suggests and our findings from interviews affirm, increased density, mixed-use development, and zoning flexibility are perhaps the greatest pathways toward the development of affordable housing in the region [32,36].

5. Conclusions

The housing crisis in the United States and Greenville County is unlikely to abate without effective policy measures at the state and local levels. Ensuring safe, affordable, and good-quality housing for a community is a multifaceted problem that requires a diverse set of solutions based on the needs and conditions of the local community. Policy measures that focus on issues of housing as a social determinant of health are more likely to consider affordability issues, access to transportation, issues impacting physical activity, and other related health risk factors. The complexity of this challenge requires policies at all levels of governance, along with engagement and solutions from the community and non-profit organizations.

At the state level, states that have passed inclusionary-zoning-enabling legislation appear to be more effective at creating an environment for more affordable housing than states without this type of legislation. In the same vein, states that allow for the creation of housing, renter advocacy groups, and rent stabilization programs also create pathways for more affordable housing. Programs that allow for the right to legal counsel laws, rental/eviction legal defense funds, bans on income source discrimination, and others also enable an environment for more stable housing across a community. However, the creation and certainly the implementation of much of the policy and regulation around affordable housing occur at the local level.

As this review illustrates, communities that have passed inclusionary zoning measures have carried this out in ways that attempt to meet the needs and demands of their communities. This research confirms that in the face of rising housing costs, gentrification, and clear geographic discrepancies around health risk factors and health outcomes, Greenville County is at an important juncture, and it would benefit the county to proactively consider measures that support affordable housing measures across the community. As one of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and one that impacts someone’s access to work, education, healthcare, nutrition, etc., policy mechanisms that enable a wide range of housing options create short- and long-term benefits for individuals, families, and the larger community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D., N.T., O.A.I. and A.O.O.; methodology, N.T., O.A.I., L.D. and A.O.O.; formal analysis, N.T., O.A.I., L.D. and A.O.O.; data curation, O.A.I., A.O.O. and N.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.T., O.A.I., L.D. and A.O.O.; writing—review and editing, N.T., O.A.I., L.D. and A.O.O.; visualization, N.T. and O.A.I.; supervision, N.T. and L.D.; project administration, L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the United States Office of Minority Health to Livewell Greenville and is in collaboration with Furman University and Clemson University with a subaward project number 205-2015954.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Clemson University with the identification code IRB2024-0795 on 19 November 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Inform consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Before each interview, participants were provided with a verbal informed consent outlining the purpose of the research, confidentiality protocols, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Consent to record the interview was also obtained. The verbal informed consent was necessary as the interviews were conducted online virtually. This was further approved by the institutional IRB. The language below is the verbal informed consent that was utilized: “I am conducting research about affordable housing, and I am interested in your experiences as ___________. The purpose of the research is to investigate stakeholders’ insights on policies that facilitate the development of affordable housing in Greenville County. Your participation will involve one informal interview that will last between thirty minutes and an hour. This research has no known risks. This research will benefit the academic community because it helps us to understand issues around housing policies and particularly those related to access to affordable housing for low-income and minority groups that improve overall community well-being in the region. Our research team will protect all interviewees privacy. Your identity or personal information will not be disclosed in any publication that may result from the study. No recordings will be shared publicly. All notes and audio recordings will be kept on a password protected computer in a locked office. Once audio recordings are transcribed, reviewed, and converted to digital files, they will be destroyed by the research team. All notes and transcripts of recordings will not contain identifiable information. Notes will be kept for up to five months at which time all notes will be destroyed. No data will be shared with future researchers or use any data for future research studies”. Would it be all right if I audiotaped our interview? Saying no to audio recording will have no effect on the interview.

Data Availability Statement

The LawAtlas data utilized for the policy scan are openly available at https://legacy.LawAtlas.org/datasets/inclusionary-zoning (accessed on 10 October 2024). Interview data are unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Comparative Case Study Program Characteristics

|

|

References

- Aratani, Y.; Chau, M.M.; Wight, V.; Addy, S.D. Rent Burden, Housing Subsidies and the Well-Being of Children and Youth. 2011. Available online: https://www.nccp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/text_1043.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Jones, A.; Squires, G.D.; Nixon, C. Ecological associations between inclusionary zoning policies and cardiovascular disease risk prevalence: An observational study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2021, 14, e007807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. Rental Burdens: Rethinking Affordability Measures. 2014. Available online: https://archives.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr_edge_featd_article_092214.html (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Delouya, S. Nearly Half of US Renters Spend More Than 30% of Their Income on Housing Costs. CNN. 2024. Available online: https://abc17news.com/money/cnn-business-consumer/2024/09/12/nearly-half-of-us-renters-spend-more-than-30-of-their-income-on-housing-costs/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- United States Census Bureau. Nearly Half of Renter Households are Cost-Burdened, Proportions Differ by Race. 2024. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2024/renter-households-cost-burdened-race.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. (n.d.). The Human Right to Adequate Housing; Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-housing (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Gaylord, A.L.; Cowell, W.J.; Hoepner, L.A.; Perera, F.P.; Andrews, H.F.; Rauh, V.A. Impact of housing instability on child behavior at age 7. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1635–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bess, M.; Miller, M.; Mehdipanah, R. Community Inequality and Connection to Basic Needs. Minnesota Department of Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/ace/commconnbasicneed.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Hock, E.; Blank, L.; Fairbrother, H.; Clowes, M.; Cuevas, D.C.; Booth, A.; Goyder, E. Exploring the impact of housing insecurity on the health and well-being of children and young people: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 19735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. In Reducing Intergenerational Poverty; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Collinson, R.; Ellen, I.G.; Ludwig, J. Low-income housing policy. In Economics of Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 59–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kalugina, A. Affordable Housing Policies: An Overview. 2016. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/ab84123b-8e26-498f-afc8-b4bc3fd3653c/content (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- National Low Income Housing Coalition. (n.d.). State and City Funded Rental Housing Programs. Available online: https://nlihc.org/state-and-city-funded-rental-housing-programs (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Fischel, W.A. An Economic History of Zoning and a Cure for its Exclusionary Effects. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, R. Health, safety, and the general welfare: Markets, politics, and social science in early land-use regulation and community design. J. Urban Hist. 1998, 24, 675–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stach, P.B. Zoning—To Plan or to Protect? J. Plan. Lit. 1987, 2, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoff, P.; Davidoff, L. Opening The Suburbs: Toward Inclusionary Land Use Controls. Syracuse Law Rev. 1971, 22, 509–536. [Google Scholar]

- Shertzer, A.; Twinam, T.; Walsh, R.P. Zoning and segregation in urban economic history. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2022, 94, 103652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troesken, W.; Walsh, R. Collective Action, White Flight, and the Origins of Racial Zoning Laws. J. Law Econ. Organ. 2019, 35, 289–318. [Google Scholar]

- Young, L.C. Breaking the color line: Zoning and opportunity in America’s metropolitan areas. J. Gend. Race Justice 2005, 8, 667–710. [Google Scholar]

- von Hoffman, A. Single-Family Zoning: Can History be Reversed? 2021. Available online: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/single-family-zoning-can-history-be-reversed (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- American Planning Association. What Is Zoning Reform and Why Do We Need It? 2023. Available online: https://www.planning.org/planning/2023/winter/what-is-zoning-reform-and-why-do-we-need-it/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- National Association of Realtors. (n.d.). Zoning. Available online: https://www.nar.realtor/zoning (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Whittemore, A.H. Exclusionary zoning: Origins, open suburbs, and contemporary debates. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2021, 87, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PolicyLink. Inclusionary Zoning. 2023. Available online: https://www.policylink.org/resources-tools/tools/all-in-cities/housing-anti-displacement/inclusionary-zoning (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Choi, J.H.; Goodman, L. Why the Most Affordable Homes Increased the Most in Price Between 2000 and 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102216/why-the-most-affordable-homes-increased-the-most-in-price_2.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Calavita, N.; Mallach, A. (Eds.) Inclusionary Housing in International Perspective: Affordable Housing, Social Inclusion, and Land Value Recapture; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Monroy, A.; Gars, J.; Matsumoto, T.; Crook, J.; Ahrend, R.; Schumann, A. Housing Policies for Sustainable and Inclusive Cities: How National Governments Can Deliver Affordable Housing and Compact Urban Development; OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2020/03; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. Approval Delays Linked with Lower Housing Affordability. 2023. Available online: https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/blog/2023/approval-delays-linked-lower-housing-affordability (accessed on 10 May 2025).