Abstract

In the context of globalization and rapid societal changes, preserving sacred landscapes is vital for cultural identity and resilience. This study investigates the concept of liminality within the cultural landscape of Neira Island, emphasizing the significance of the Buka Kampung ritual and keramat (sacred objects) as integral components of Neira landscape identity. Through qualitative analysis and case studies, the study explores how these rituals serve as liminal practices that mediate between continuity and transformation. The findings highlight that the act of making offerings at keramat during the Buka Kampung ritual fosters social cohesion and reinforces collective identity. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of the interplay between sacredness, rituals, and identity, demonstrating how these elements shape place attachment, collective memory, and the lived experiences of local communities. It highlights the importance of sacred landscapes in fostering community resilience and cultural continuity, offering insights into the role of ritual practices in heritage preservation.

1. Introduction

The Maluku Islands, particularly the Banda Archipelago, have undergone profound socio-cultural, political, and spatial transformations since the height of the global spice trade from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries [1,2,3]. European colonization significantly restructured local dynamics through monopolized trade and forced relocations, displacing long-standing indigenous beliefs with Islam and Christianity [4,5,6]. Nevertheless, the Banda Islands remain deeply rooted in oral traditions, particularly the Kabata—a poetic narrative used to transmit historical memory, cosmology, and moral teachings during ritual events [7]. These oral practices affirm the enduring role of cultural memory and relational cosmology in shaping Bandanese identity.

Historical sources such as Hikayat Banda Lonthoir (1922) narrate the mythical arrival of Banda’s ancestors from Makawaij to Andara following a great flood, embedding their settlement history within a cosmological and sacred landscape [8,9]. One ritual that vividly manifests these traditions is Buka Kampung, conducted in every customary village. Rather than a mere territorial re-entry, it symbolizes a collective spiritual reconnection among the living, the ancestors, and the divine [10]. It serves not only as a communal cleansing but also marks the commencement of mass religious instruction, revealing the integration of adat and faith in daily life [11].

While Maluku’s colonial and archeological records are relatively well-documented, little research has addressed how contemporary ritual practices actively shape spatial configurations and social relations [12,13]. Most heritage studies rely on material analyses or administrative boundaries, overlooking the symbolic and experiential nature of ritual landscapes [14]. This research fills that gap by examining how Buka Kampung redefines sacred space and community roles through performative and symbolic processes.

The study adopts Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space, which conceptualizes space as a social product shaped by practices, representations, and spatial experience [15]. This is further enriched by Catherine Bell’s (1997) interpretation of ritual as a form of strategic practice [16], van Gennep’s theory of rite de passage [17], and Haggar’s (2024) updated reading of Turner’s communitas, which explores the complex emotional and social dynamics of liminality in contemporary settings [18]. Through this combined framework, the study investigates how ritual practices in Banda transform spatial boundaries and reinforce collective belonging, while also revealing tensions, transitions, and symbolic negotiations embedded in ritual space.

The study poses two main research questions: first, it considers how spatial boundaries and social relationships are negotiated and transformed through the Buka Kampung ritual; second, it examines to what extent liminality affects the production of space in the ritual. New perspectives on how landscapes are reshaped through ritual practices within Bandanese society will not only enrich our understanding of the material heritage created through spiritual and cultural processes but also help underpin the conservation of indigenous structures [19].

Sacred Transitions: Rites, Space, and Identity

Space, as a socially produced entity, is continuously shaped by social, political, and cultural forces [15]. This notion highlights how everyday activities, planned structures, and symbolic meanings all contribute to the ongoing production and transformation of space. Instead of positioning space as merely a physical or natural setting, it positions space as dynamic, influenced by human interactions in their social and cultural environment. The concept of ‘landscape’ as developed by researchers in the humanities and social sciences also embraces the qualitative aspects of the environment, both physical and intangible elements of places. Landscape encompasses dynamic systems of cultural and natural resources, shaped by networks of interaction and sustained through traditional knowledge and everyday practices of local communities [20]. Recent studies have built on the “sense of place” to introduce the “sense of landscape” [21,22] or landscape identity [23]. “Place” refers to a space that acquires meaning through individual, collective, or cultural processes [24]. It also represents a universal emotional bond rooted in ancestral ties, a sense of belonging, and an attachment to locality [24,25,26]. A place encompasses the integration of actions, experiences, and intentions that unfold in specific spatial and temporal settings [25]. Its significance is heightened by its atmosphere—often described as the “sense of place”—which reflects the unique expressive energy of an environment [27]. This sense of place forms through long-term emotional engagement and familiarity with a given environment [28]. Stedman [29] emphasizes the physical environment’s role in shaping attachment and meaning. Pred [30] and Seamon [31] extend this by framing place as a process: it is produced through action, and action is shaped within place. The biography of people and things becomes intertwined with the formation of place itself. Thus, as Punter [32] asserts, the sense of place emerges from the interaction of physical environment, meaning, and activities. These dimensions are essential to understanding how ritual, identity, and social cohesion are grounded in particular cultural landscapes. The concept of landscape transcends the individual perspective of ‘sense of place’ by emphasizing the social and collective nature of landscape, which is shaped through human interaction. Landscape, therefore, is not merely an esthetic or visual concept but also incorporates issues of identity, ownership, conflict, justice, and social and ecological balance within communities. Connections between landscape and identity emerge largely through emotions and experience, traditions and memories, rather than simply by rational reflection; in landscapes, these human social and cultural facets are entangled with the material character of regions and places.

The connections between people and places are also important to modern ideas about heritage [33,34], which emphasize the centrality of values (rather than regarding heritage simply as collections of things from the past). The heritage values of landscapes provide pathways for communities to transition towards the future, shaped through dialog with the past. Rituals performed in landscapes—whether as formal as a religious ritual or as casual as daily activities—are creative acts that enable individuals and communities to transform their environments [16]. Therefore, it is essential to examine how and why specific communities or ritual practices as a means of understanding how they create and re-create cultural identity through landscape and heritage.

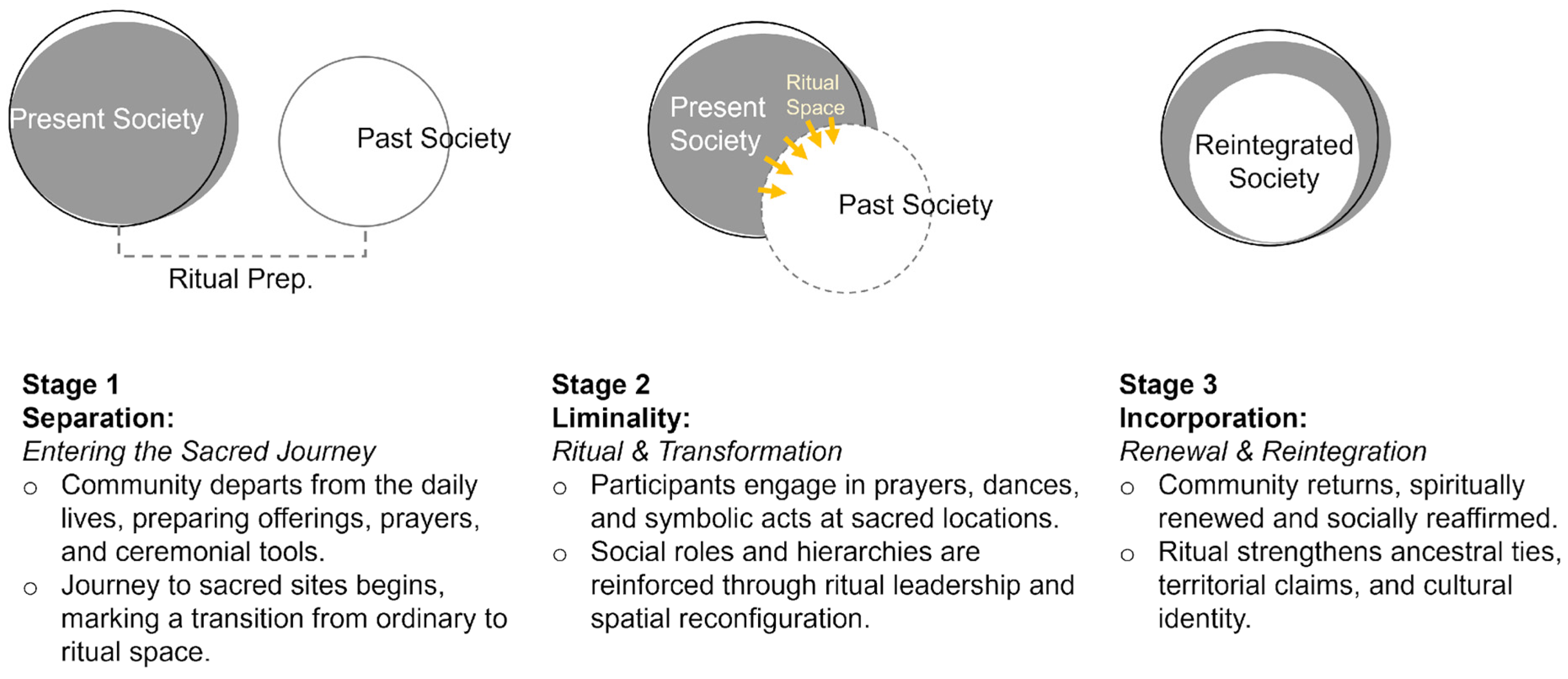

Arnold van Gennep’s theory of rite de passage (1909) provides a structured understanding of life transitions through three phases: separation, liminality, and incorporation [17]. The first phase, separation, involves the individual’s departure from their previous social role and identity. During liminality, individuals find themselves in a state of ambiguity, existing between their former and new roles, where they are socially and symbolically dislocated. This phase is often characterized by rituals that facilitate transformation and reflection. Finally, the incorporation phase marks the reintegration of the individual into society, often with a new social identity or role. These phases are universal in marking significant changes in social roles, from birth to death, often through symbolic rituals that guide individuals through each stage. The significance of these rituals is not only in the individual transformation but also in the way society’s structure maintains cohesion through these processes [16,35,36,37]. During such transformation, individuals or groups are in a state of ambiguity or ‘liminality’ between previous and new social roles [27]. In ritualistic contexts, liminality serves as a space where individuals can transform, gaining new status or clarity upon their reintegration into society [38]. Santos-Granero (1998) suggests that liminality is not confined to individual experiences but can also be observed in collective rituals where communities use this transitional space to renegotiate their cultural identities within historic landscapes [39].

This is further enriched by Catherine Bell’s (1997) interpretation of ritual as a form of strategic practice [16], and Haggar’s (2024) updated reading of Turner’s communitas, which explores the complex emotional and social dynamics of liminality in contemporary settings [18]. Through this combined framework, the study investigates how ritual practices in Banda transform spatial boundaries and reinforce collective belonging, while also revealing tensions, transitions, and symbolic negotiations embedded in ritual space. The study of ritual as practice has therefore shifted from looking at activity as the expression of cultural patterns to looking at it as that which makes and harbors such patterns [16]. In this context, researching the relationship between ritual and heritage landscapes is essential for comprehending how landscapes are formed and, in turn, how they influence human experiences and shape cultural identities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

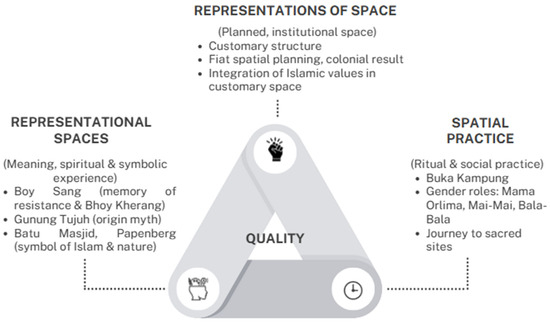

The conceptual framework for the study of the Buka Kampung ritual draws on van Gennep’s theory of rites of passage, integrating spatial, cultural, and symbolic analyses to address the research questions. The framework begins with the collection of ethnographic, spatial, and topographical data, focusing on ritual routes, sacred places, and community practices. These data serve as the foundation for analyzing the spatial patterns of liminality, where transitional zones and the phases of liminality—pre-ritual, liminal, and post-ritual—are identified and mapped. The next step applies Henri Lefebvre’s Production of Space theory as an analytical framework to examine how ritual practices actively produce, negotiate, and transform spaces physically and symbolically. Using his spatial triad—spatial practice (how space is physically used), representations of space (how space is planned and conceptualized), and representational space (how space is lived and symbolically experienced)—the analysis draws from field observations, interviews, and textural materials to identify the interplay between bodily movement, institutional narratives, and the meaning assigned to sacred places at varying elevations.

By integrating these two frameworks, the study interrogates how ritual acts as a spatial practice that redefines liminal landscapes as sacred, and how much such spaces in turn reinforce or renegotiate collective identity. The findings from these analyses are then synthesized to explore the cultural and spatial implications of the ritual, assessing how it sustains or challenges existing social structures while fostering community identity and cultural continuity. Finally, through triangulation with key informants and validation of interpretations, the study develops a comprehensive narrative that connects spatial transformations to the ritual’s role in shaping societal dynamics and maintaining the Adat Unity’s cultural legacy, a traditional system of governance and social organization in the Indigenous community. This iterative process ensures a holistic understanding of the interplay between space, culture, and spirituality in the Buka Kampung ritual.

2.2. Study Area

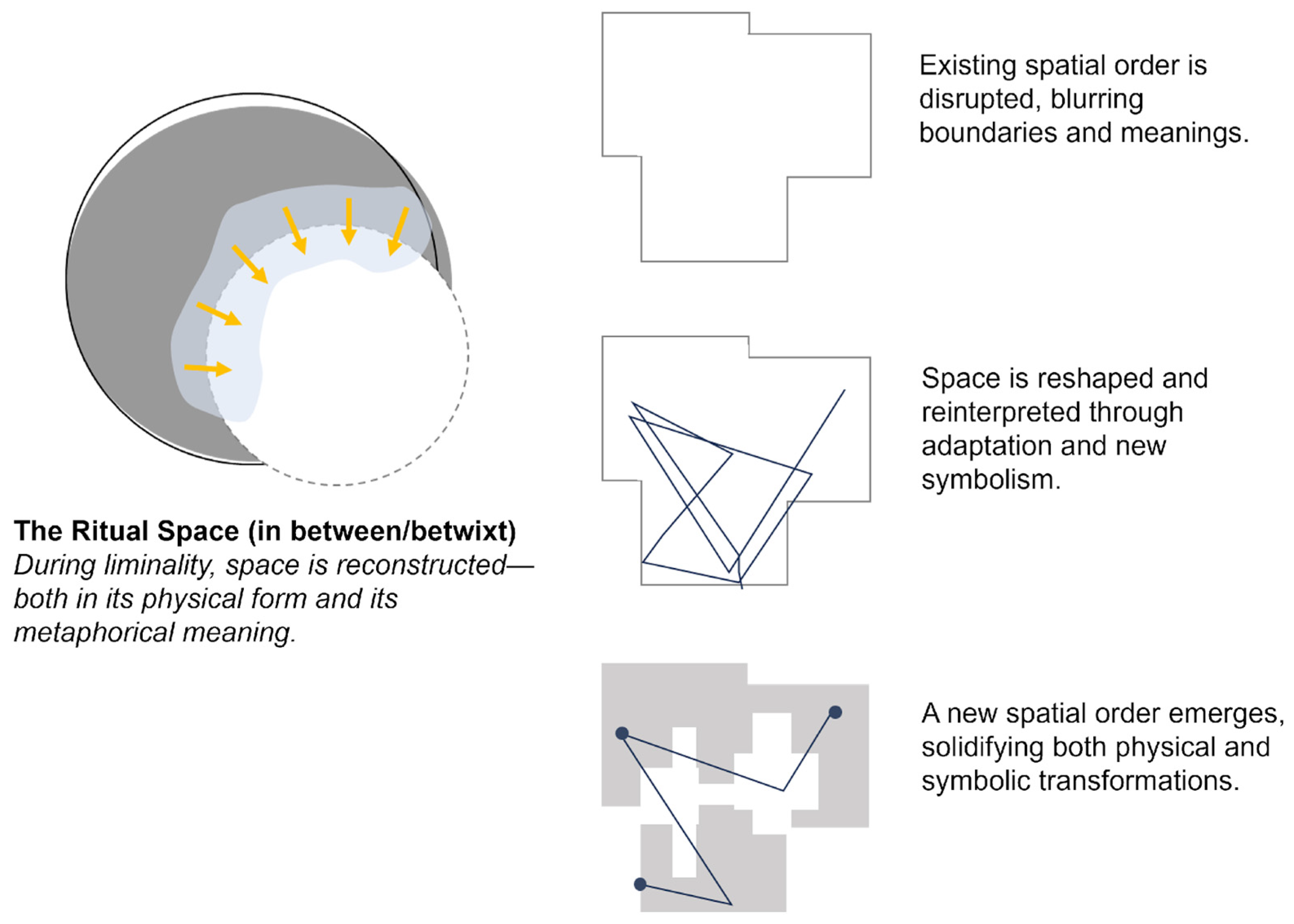

The research took place in Banda Neira, an island within the Maluku archipelago that holds profound cultural, social, political, and religious significance. Administratively, Banda Neira is divided into several villages (Figure 1), which are organized under three main customary (adat) villages:

Figure 1.

Banda Neira Island.

- Kampung Adat Namasawar, located at the northern tip of the island, consists of three sub-villages: Nusantara, Merdeka, and Rajawali;

- Kampung Adat Ratu (Dwiwarna), located in the central region of the island;

- Kampung Adat Kampung Baru (Fiat), located towards the southern part of the island.

Each of these adat villages plays a key role in maintaining the cultural heritage and governance systems of Banda Neira, with distinct leadership structures that are grounded in traditional practices. The village heads (kepala desa) historically held the title of Orang Kaya (regent) while the Orang Lima (five elders) were responsible for overseeing the adat governance, spiritual practices, and community welfare.

One of the most important adat areas within Kampung Adat Namasawar is Lautaka, situated in the northernmost part of the island. Lautaka holds profound significance both spiritually and historically, as it is one of the earliest inhabited regions of the Banda Islands. The settlement of Lautaka was primarily driven by its abundant spice plantations, which include one of the oldest nutmeg plantations on the island, as well as a concentration of historical spice estates. Over time, these plantations became an integral part of the local identity, shaping the livelihoods and belief systems of the community.

Lautaka is deeply embedded in the mythology and historical narratives of Banda. It is mentioned extensively in the Hikayat Lonthoir, a traditional chronicle that recounts the origins of settlements, ancestral journeys, and the spiritual significance of sacred sites in the Banda Islands [8]. According to the Hikayat, Lautaka was the first region where early Bandanese ancestors established their settlements, cultivating spice plantations while maintaining a deep spiritual connection to the land [8]. This bond between the land and spirituality is reflected in the numerous sacred burial sites found in Lautaka, where influential figures from the past—those who played pivotal roles in shaping the community’s history—were laid to rest. These sacred burial sites, including Makam Lewetaka/Keramat Kota Banda/Kubur Gila, are still revered today as keramat (sacred sites) and are honored by the community through ritual offerings and traditional ceremonies. These acts of commemoration serve not only to respect ancestral heritage but also to strengthen the spiritual and social cohesion of the Bandanese people.

In addition to its cultural and spiritual importance, Lautaka is historically significant due to its role in resisting colonial powers. As noted by van Donkersgoed and Farid (2022), the Banda people fiercely opposed the Dutch monopolization of the spice trade, which led to violent conflicts and mass displacements [7]. Many of the sacred sites in Lautaka, such as Batu Kadera and Parigi Laci, are believed to be places where local leaders strategized against the colonial forces or sought refuge during times of conflict. These sites continue to function as important locations in ritual practices, particularly during the Buka Kampung ritual, which symbolizes rebirth, renewal, and the reaffirmation of communal ties.

Moving beyond Lautaka, Kampung Adat Ratu (Dwiwarna) and Kampung Baru (Fiat) also play significant roles in Banda Neira’s cultural and political landscape. Kampung Baru (Fiat) is historically notable for the settlement area known as Tanah Rata, which became a refuge for the Banda people after the large-scale displacement during the Dutch colonial period [10]. The region of Tanah Rata, located in the southern part of the island, later became a vital area for administrative and cultural renewal following Indonesia’s independence. The community in Kampung Baru (Fiat) continues to practice rituals that honor both their ancestors and the legacy of resistance against colonial rule [10].

Meanwhile, Kampung Adat Ratu (Dwiwarna) is situated in the central part of the island and is known for its historical significance during the colonial era. This village has a rich heritage, as it was once a site for Dutch plantation workers and administrators. The influence of colonial architecture is still visible, especially in the form of remnants from the Dutch period, such as old buildings and religious symbols. Despite this colonial history, Dwiwarna continues to uphold its traditional customs, blending both indigenous and colonial influences in its cultural practices. Through the presence of these adat villages, Banda Neira continues to preserve its rich cultural heritage. The sacred sites, rituals, and historical narratives of each village contribute to the collective memory and identity of the Bandanese people. These practices are not only a means of honoring the past but also act as a foundation for community resilience and continuity in the face of social and political change.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

This study uses qualitative methods to explore an in-depth understanding of the cultural and historical meanings of Banda Neira’s traditional areas, particularly in the context of traditional rituals and the community’s spiritual relationship with their ancestors. Informants were selected purposely based on their roles in sustaining and transmitting traditions. The selection was guided by an initial scoping process where the research team engaged the community to identify key knowledge holders and practitioners of the ritual. Informants were categorized into three groups: key informants (e.g., Ama Kaka, Orang Lima Besar, Bapak Imam), main informants (ritual actors), and supporting informants (elders, local historians), enabling a multi-perspective understanding of the practice.

Data collection was conducted through in-depth interviews, participatory observation during the rituals, and documentation of oral histories. Historical texts and archival materials were also used to compare past and present forms of the ritual and its spatial organization. In parallel, spatial data were collected to map the ritual landscape, including sacred places (tempat keramat), ritual routes, and symbolic markers.

The analysis combined thematic and narrative techniques with spatial and symbolic interpretation. Thematic coding was applied to identify recurring patterns and meanings. Narrative analysis focused on stories and myths that articulate social memory and territorial identity. Spatial analysis was employed to visualize the distribution and relationships of ritual sites using ArcGIS Pro 2.7. Each sacred site and ritual location was georeferenced and mapped to uncover spatial patterns and their symbolic meanings.

Symbolic analysis followed a performative approach to examine how rituals enact and produce space, referencing Lefebvre’s spatial triad [15] and Turner’s rites of passage framework [17,36]. The physical space was treated as a semiotic text [40], interpreted through hermeneutic readings informed by local cosmology and practice. GIS technology was instrumental in visualizing how space is socially constructed and symbolically maintained. This enabled the identification of liminal zones, central sacred points, and movement patterns across ritual stages (preliminal, liminal, and postliminal) [35,37].

Triangulation was achieved by cross-validating ethnographic findings with spatial and historical data. This comprehensive approach ensured analytical rigor and revealed how sacred space in Banda Neira is continuously produced through ritual, memory, and interaction.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Production of Buka Kampung

The Buka Kampung ritual is one of the main mechanisms in producing sacred space for the Banda indigenous community. Sacredness in Banda society does not exist singly, but rather as a result of historical, spiritual, and social relationships that continue between generations. The customary rituals that are carried out, such as journeys to sacred sites and prayer practices, show how space is used (spatial practices), imagined by customary and religious authorities (representation of space), and interpreted collectively (representational space). Buka Kampung functions as a cross-generational ritual that transforms ordinary space into sacred and meaningful space. These sites are not just stopping places on a customary journey, but rather points of interaction between collectives, local cosmologies, and strategic resistance to colonial history. These spaces, initially perceived as mundane or transitional, are activated through repeated use during the ritual, giving them new meaning and significance. As participants move through these spaces, they impose symbolic value that alters the perception and experience of the physical environment.

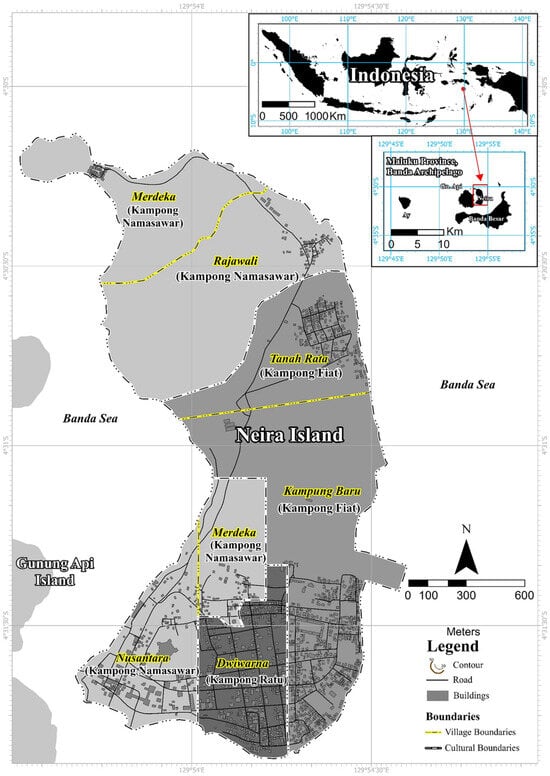

This study focuses on the sacred sites in Kampung Adat Namasawar and Fiat (Figure 2), which have been shaped by generations of ritual practices, ancestral beliefs, and the Banda indigenous community’s history. Namasawar, founded during the era of the Lautaka kingdom, is closely tied to the narrative of resistance and sacred natural sites, particularly before the 16th-century VOC massacre [8]. In contrast, Fiat developed and was formed after the massacre and was more integrated with the spread of Islam and religious authority, emphasizing spiritual continuity than historical resistance [40]. Ratu Village (Dwiwarna), in comparison, is excluded from this study due to its colonial roots and lack of ritual continuity. The historical context of each village shapes its representation of space, where colonial power intervenes and defines the spatial layout of the village, but indigenous people continue to produce sacred spaces through narratives of resistance and spiritual customs with varying intensity between Namasawar and Fiat. This historical foundation informs the different relations between humans, space, and spiritual power, while serving as the framework for understanding the production of sacred space in Banda.

Figure 2.

Ritual routes and sacred places in Neira Island showing the traditional pathways of Buka Kampung ceremony for Namasawar and Fiat traditional village, with detailed mapping of sacred sites, built-up areas, and topographic features at a 1:13,500 scale based on field observations and interviews.

Theoretical frameworks on the social production of space and the sense of landscape provide a critical lens to understand the spatial dynamics embedded in sacred practices across Banda Neira. Rather than being neutral containers, spaces acquire meaning through social interactions, rituals, and embodied experiences (Lefebvre, 1991 [15]). As Lefebvre theorized, space is not only shaped by physical structures but also by symbolic representations and lived practices. Similarly, the concept of landscape, as developed in the humanities and social sciences, extends beyond visual esthetics to include intangible dimensions such as emotional attachment, memory, and identity (Olwig, 2019 [20]; Stobbelaar and Pedroli, 2011 [23]). Landscape identity emerges from the interplay between physical environment, cultural meanings, and community activities (Pred, 1984 [30]; Seamon, 2015 [31]). In the Bandanese context, sacred landscapes are formed through intergenerational ritual practices, mythologies, and cosmological narratives, serving as dynamic spaces where the spiritual, ecological, and historical dimensions of identity intersect. These sacred sites, therefore, function as representational spaces—deeply affective and symbolically charged environments where the community continually negotiates and reaffirms its collective identity.

The sacred sites in Namasawar and Fiat not only refer to the physical existence of these locations but also reflect how they have been spiritually and historically utilized, connecting the indigenous community to their ancestors and the surrounding environment, and reinforcing their sense of collective identity and continuity. Key sites shared by both Namasawar and Fiat, such as Boy Sang, Papenberg, Makam Lewetaka (Keramat Kota Banda), and Batu Masjid, a sacred site that is not only linked to Islamic values, but also the history of local struggle, where a flag captured from the war against Spain was given [2,41,42]. This stone is still used for meditation and is revered by various communities, making it a very sacred place in the collective experience of the Banda people. Boy Sang, as a site of respect for Bhoy Kherang, a female figure who led the resistance against the VOC, contains historical, spiritual, and collective identity dimensions [43,44]. Papenberg, as the highest point topographically, represents the vertical relationship of the Banda people with nature and spirituality, a symbol of the journey to the ancestors. Also, that place has always been used as a meeting place for traditional elders since ancient times [45]. Makam Lewetaka marks the continuity of customary lines and spiritual authority, while Batu Masjid reflects the integration of Islam and local customs. These four sites form representations of space in Lefebvre’s framework, as they are institutionally understood by the indigenous people as the center of cosmology and history. Through ritual practices such as pilgrimages, offerings, and prayers, these spaces become spatial practices that continually reproduce sacred meanings. What makes them representational spaces is the ongoing collective experience, fostering a sense of belonging to both history and shared identity. The high level of sacredness is determined by cross-village involvement, the role of spiritual figures, and historical values that are still internalized today. Academically, these spaces function not only as ritual sites but also as living archives of local history, continually reproduced through the social and spiritual practices of the Banda indigenous community.

The exclusive sacred places belonging to Kampung Namasawar have a character that is more connected to the natural landscape and ancestral mythology. Sites such as Gunung Tujuh (Ulupitu), Gunung Manangis, Dapur Pala, Pasir Panjang, and Batu Kadera show scattered spatial patterns, indicating a cosmological relationship with mountains, seas, and large rocks [44]. For example, Gunung Tujuh is believed to be the birthplace of the seven children of Siti Galsoem, who symbolize the origin of the Banda people’s lineage [8]. Dapur Pala or Perk marks the space for the production and preservation of sacred commodities (nutmeg), which is a symbol of economic resistance to colonialism. The sacredness of these places varies: from very high (Gunung Tujuh as the place of origin) to medium (Pasir Panjang as a ritual transit point). Customary practices such as opening the village, offerings of agricultural products, and oral narratives strengthen the status of these places as representational spaces with meanings that continue to live in the collective consciousness. Within the framework of the production of space, these spaces are the result of cultural practices and historical narratives that reproduce customary values towards nature. Namasawar’s position, which was not massively disturbed by colonialism, made the sacredness of these spaces more intact and continuous. Academically, this exclusive sacred place shows that the spirituality of indigenous peoples is not just a form of belief, but also a way of simultaneously caring for history, nature, and social structures through the production of multi-layered spaces.

In addition, sacred places exclusively visited by Kampung Fiat, such as Nira Bati Wetro and Tanjung Besar, show a pattern of sacredness that is more focused on aspects of Islamic religiosity and historical healing [10]. Nira Bati Wetro is the tomb of a respected great scholar and is an important point in pilgrimage and prayer rituals, while Tanjung Besar has a mystical meaning that connects the community with the power of nature and ancestors. These places have a medium to high level of sacredness depending on the context of the ritual and the role of the respected figure. Sacredness in this context is more symbolically structured as representations of space, because it is designed through an Islamic value system integrated into custom. Although there are not as many sites in Namasawar, the sacredness of these places is strengthened by the spiritual practices of the community and the narrative of post-colonial recovery. Fiat, as a village resulting from post-genocide restructuring in 1621, rebuilds sacred space as a form of representational space that heals historical wounds [45,46]. Through the practice of opening the village, the Fiat community strengthens collective memory while reproducing local Islamic-based social structures [46]. The production of space in Fiat reflects new social dynamics that combine adaptation, healing, and the search for identity. From an academic perspective, Fiat’s sacred sites are a new form of articulation of the production of spiritual space born from colonial trauma, making them a concrete example of the transformative production of space.

Papenberg, topographically the highest ritual site, holds profound spiritual significance as a sacred point visited by both villages [44]. The ascent to this site in traditional rituals symbolizes the Banda people’s spiritual journey in honoring their ancestors. Papenberg is significant as a spiritual space, closely tied to the presence of Wali Allah, reflecting the assimilation of Islamic beliefs and local customary systems. Meanwhile, Makam Lewetaka, also known as Keramat Kota Banda or Kubur Gila, is the burial site of a highly respected customary figure and serves as a stop during rituals conducted by both villages. This site represents historical continuity and ancestral lineage, where ritual practices strengthen the social and cultural bonds with villagers’ forebears. Batu Masjid, which has a shape resembling a mosque dome, is another sacred site visited by both indigenous villages. As a representation of Islam within local traditions, Batu Masjid functioned as a customary gathering place in the past and remains a symbol of the assimilation between Islamic teachings and Banda’s indigenous beliefs [44].

Thus, the sense of place in the sacred sites of both adat villages is shaped by ritual practices passed down through generations, where spirituality and history forge the relationship between people and space. Spatial practices in adat rituals create a dynamic cultural space, where sacred sites serve not only as geographical locations but also as symbols of resistance, spirituality, and communal identity. The distribution patterns of sacred sites illustrate both the interconnectedness and distinctions between the two villages, with shared ritual sites representing historical unity while exclusive sites reflect their distinct functions and identities.

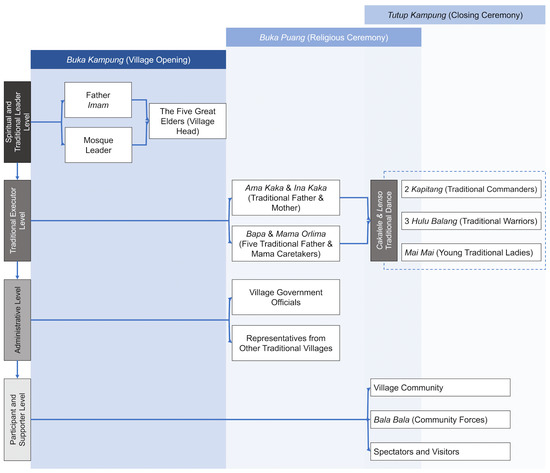

Beyond its role in cultural space production, Buka Kampung also shapes and reinforces social structures through the involvement of various key figures in the ritual. The organizational structure of the Buka Kampung ceremony, encompassing the phases of village opening, religious rituals, and closing, illustrates the dynamic production of sacred space as theorized by Henri Lefebvre. Through this lens, space is not static or neutral but socially produced through spatial practices (rituals like prayers, offerings, and dances), representations of space (formal hierarchies and symbolic roles of spiritual and traditional leaders), and representational space (emotional, embodied experiences of the community). The ritual structure, from the imam to community forces, demonstrates how sacred space is constructed by the interplay of authority, tradition, and collective memory, transforming physical places into spiritually charged, socially meaningful landscapes.

At the apex of the ritual hierarchy during the Buka Kampung phase, spiritual leadership is held by the Imam (Father Imam) and the Mosque Leader, who serve as intermediaries between the community and the divine realm (Figure 3). They operate in conjunction with the Five Great Elders, who hold symbolic and procedural authority within the village. This spiritual core establishes the sacred legitimacy and cosmological alignment of the ritual opening. On the traditional executor level, the presence of Ama Kaka and Ina Kaka (traditional father and mother) and the Bapa and Mama Orlima (the five elder traditional caretaker couples) reflects the gendered and generational custodianship of indigenous knowledge and morality. These actors serve as the ritual organizers, moral anchors, and enforcers of cultural continuity through performative and spoken tradition. Their role marks the articulation of sacred space through embodied practice and inherited wisdom.

Figure 3.

The hierarchical organization structure of the Buka Kampung ritual in Banda Islands, illustrates the various levels of authority and participation from spiritual leaders to community members, including traditional roles, administrative positions, and participant categories.

Further engagement is evident at the administrative level, where village government officials and delegates from neighboring traditional villages participate. This involvement suggests that Buka Kampung is not merely a localized cultural event but operates as a platform for regional socio-political negotiation, inter-village diplomacy, and ceremonial governance. The convergence of formal and customary authorities highlights a syncretic system of ritual administration that transcends bureaucratic boundaries.

The Buka Puang phase intensifies the sacred dimension of the ritual sequence, centering on offerings, prayer, and spiritual invocations. The previously identified actors continue their roles, but with greater emphasis on the symbolic parent figures (Ama Kaka, Ina Kaka, and Orlima) who mediate ancestral presence and spiritual vitality. This phase illustrates the enactment of mobile sacrality, in which sacredness is not bound solely to physical sites but is animated through ritual action, bodily presence, and relational networks.

Finally, the Tutup Kampung ceremony culminates in a collective expression of cultural identity through traditional dance performances, particularly Cakalele and Lenso, involving designated groups such as the 2 Kapitang (traditional commanders), 3 Hulu Balang (traditional warriors), and Mai-Mai (young traditional women). These figures represent symbolic protectors and transmitters of heritage, whose choreographed movements encode both martial valor and communal harmony. The participation of the broader village community, Bala Bala (community forces), and spectators or visitors at the lowest level signifies the communal production of sacredness through embodied witness, emotional engagement, and ritual solidarity.

Women in Banda have played a central role in safeguarding land, customs, and lineage in the Banda Islands since the colonial period in 1609 [47]. This is reinforced by the presence of the Bhoy Kherang and Siti Galsoem figures in the oral history of Banda, showing how women are the main actors in maintaining customary space and spirituality [46]. In the customary structure, the Mama Lima and Mama Sembilan groups hold authority in carrying out rituals, from preparing offerings to spiritual purification. Women also play a role in transmitting customary values to the younger generation, as well as leading aspects of rituals that touch on everyday dimensions, such as processing nutmeg and arranging traditional houses. Mai-Mai’s involvement in the Lenso dance during the liminal phase of the ritual reflects the importance of women’s representation in sacred transitions and cultural regeneration. According to Lefebvre, representational spaces are strongly influenced by affective and symbolic experiences, which in the Bandanese context are actively managed by women. This proves that the production of space is not only the result of male authority, but also comes from women’s deeply rooted spiritual and social experiences. In rites of passage, women play a role in the stages of transition and social recovery, making them guardians of social cohesion and customary values. So, academically, the role of women in the production of sacred Bandanese spaces is not complementary, but rather a core element in customary regeneration and continuity.

Considering all these aspects, the Buka Kampung ritual is a concrete form of regenerative, symbolic, and collective spatial production in the Banda indigenous community (see Figure 4). It not only maintains old values but also allows for the renegotiation of social and spiritual boundaries in a society that is constantly changing. Through Lefebvre’s approach, we see that sacred space in Banda is not natural or passively inherited, but rather the result of a dynamic interaction between practice, power, and spiritual experience. The involvement of women, the younger generation, and traditional leaders shows that the production of space involves all elements of the community in an equal trajectory. At the same time, the distribution of sites shows different cultural orientations, but remains within the framework of Banda’s spiritual unity. The author argues that the study of sacred space like this offers an important approach in understanding the social dynamics of indigenous communities, especially amidst the pressures of modernity and cultural homogenization. By understanding space as a result of social construction, we can be more just and contextual in designing local cultural preservation policies. So, Buka Kampung is not only a religious or customary ritual, but also a social archive that is continuously updated in space and time.

Figure 4.

Triad Analysis Production of Space of Buka Kampung.

3.2. Ritual in Neira

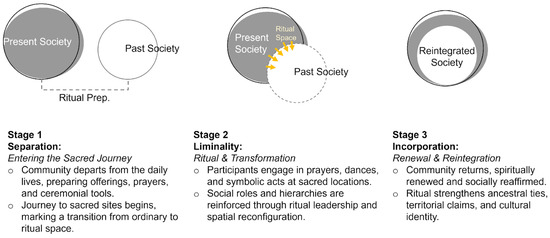

Buka Kampung enables the Indigenous community to create sacred spaces as a group, rebuild their connection to the past, and strengthen their social bonds through rituals that have been passed down from generation to generation (Figure 5). The ritual is not only a symbolic moment for participants but also a collective process that allows the Banda community to undergo social transition, renew their attachment to sacred spaces, and reaffirm their cultural identity through cyclical ritual practice. During the Buka Kampung ritual, the social space is reproduced through pilgrimages to sacred sites, which function as liminal spaces where the boundary between the profane and the sacred becomes blurred. This cyclical process of separation, liminality, and incorporation forms the foundation for understanding how sacred space is produced and experienced.

Figure 5.

Application of Arnold van Gennep’s three stages of Rite de Passage to the Buka Kampung ritual in Banda Neira, depicting the progression from separation through liminality to incorporation, with each stage’s distinct characteristics and ritual functions in the community’s spiritual and social transformation.

The separation phase marks the initial detachment from everyday life and social roles. In the context of Buka Kampung, this phase is characterized by participants preparing for the ritual by moving away from their routine environments. This could include specific actions like participants gathering at a designated ritual space or sacred site, symbolizing their departure from the mundane world into a space of transformation. This phase may also involve symbolic acts such as cleansing or offerings, further marking the ritual separation. For example, during the preparation of Buka Kampung, the Banda indigenous community symbolically detaches from their daily activities and enters a transitional phase through various ritual preparations, such as self-purification, prayers at the traditional house, and the preparation of betel nut offerings and other ceremonial materials. This process sets the stage for their subsequent transition into the liminal phase.

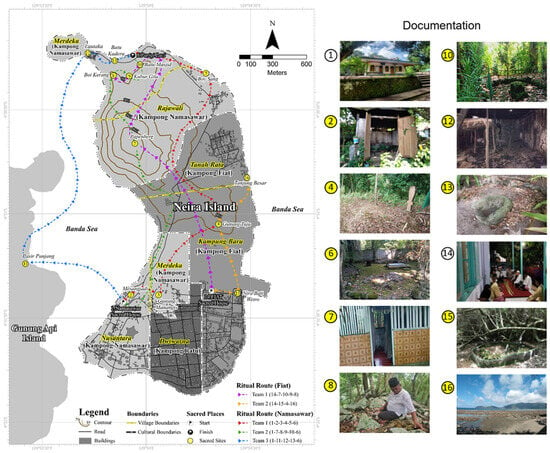

The liminal phase is the core of transformation, where participants experience a state of ambiguity and in-betweenness. In the Buka Kampung ritual, this phase occurs as participants perform rituals, such as pilgrimages, offerings, and prayers, at sacred sites. These actions serve to temporarily suspend social roles and hierarchies, creating a space where participants are no longer bound by the everyday structures of life but are in a transitional state of becoming.

Sacred places like Makam Lewetaka and Batu Masjid, where rituals and collective practices occur, become liminal spaces during this phase. These sites are marked by ritual practices that transcend their usual function, transforming them into spaces that embody both sacredness and transformation. The cross-village involvement of participants and the collective performance of rituals deepen this sense of communitas (a term from Victor Turner), emphasizing equality and shared experience during the liminal phase. This phase marks the transition from ordinary space to sacred space, where conventional social boundaries are suspended, paving the way for a deeper experience of liminality.

In the second phase, the liminal stage in the Buka Kampung ritual is most evident during the processions to sacred sites, such as Parigi Laci, Makam Lewetaka/Keramat Kota Banda/Kubur Gila, Boy Sang, and Batu Masjid. These sites function as transitional spaces where participants not only engage with spiritual dimensions but also undergo social transformation. As outlined by Turner (1969, 1982), liminality represents a state of ambiguity in which individuals or groups exist between their former and new social statuses, allowing for the reconstruction of social and cultural meanings [36,37]. In the context of Buka Kampung, the journey to sacred places is not merely a physical transition but also symbolizes a collective renewal. During this journey, participants experience spiritual reinforcement, a reinterpretation of ancestral history, and renewed social connections.

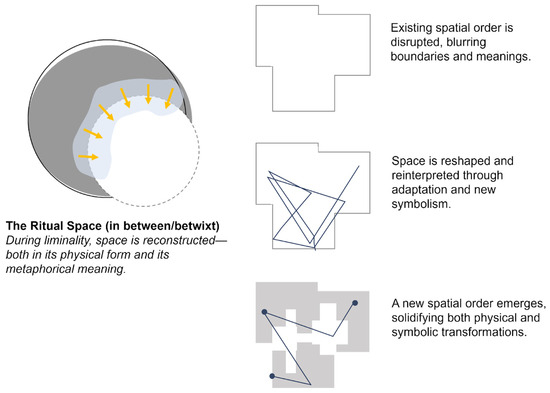

Within this liminal space, sacred sites play a crucial role in reshaping the community’s social structure. For instance, Parigi Laci serves not only as a holy site but also as a symbolic meeting point for the entire community involved in the ritual. At this site, the boundaries between the individual and the collective blur, and all participants are perceived to be in a state of spiritual equality, where everyday social statuses are less relevant compared to their collective identity as heirs to ancestral traditions. During the ritual, Parigi Laci transcends its everyday function as a fixed location and transforms into a dynamic, fluid space where distinctions between sacred and secular, public and private, or center and periphery are momentarily suspended.

The physical layout of the site, typically bound by social norms and structured movement, becomes redefined by the ritual experience, allowing for an alternative spatial order dictated by collective participation rather than conventional spatial regulations (Figure 6). This transformation underscores how liminality not only affects social roles but also reconfigures spatial perceptions, reinforcing the idea that sacred sites are not merely static places but fluid, ever-evolving landscapes shaped by communal practice and meaning-making. This aligns with Victor Turner’s concept of “community,” in which the liminal phase temporarily dissolves social hierarchies, enabling the formation of stronger communal bonds [18,37].

Figure 6.

Conceptual diagram illustrating the liminal phase in the Buka Kampung ritual as a transformative space between pre-ritual and post-ritual states, highlighting its significance in shaping the social and cultural identity of the Banda folks.

The incorporation phase represents the return to normal life, but with the individual or community transformed by the ritual experience. After the Buka Kampung ritual concludes, participants return to their everyday lives, but the sacred and historical meanings of the ritual spaces remain with them. The reintegration is marked by both physical and symbolic return to ordinary life, with a heightened sense of belonging to the community and continuity with ancestral traditions.

After passing through the liminal phase, the incorporation stage of Buka Kampung is marked by the return of the community to the traditional house after visiting sacred places. The closing procession, communal prayer, and ritual banquet mark the end of the transitional phase and the community’s return to everyday life with a renewed understanding of their cultural identity. As van Gennep (1960) explains, the reunification phase in rites de passage is a moment when individuals or communities who have passed through a liminal experience are reintegrated into the social structure with renewed status and understanding [17].

This reunification also emphasizes the transformation of their physical space. The process redefines familiar places, embedding new symbolism and meaning into the landscape. Once separate spaces become interconnected through ritual, reinforcing their role in cultural continuity. As the ritual concludes, a new spatial order emerges, solidifying both physical and symbolic transformations. Paths taken, the sacred sites, and the traditional house are no longer just locations but dynamic spaces shaped by communal practice, strengthening the sustainability of Banda’s customary identity.

Buka Kampung exemplifies how indigenous communities intertwine spiritual and social dimensions, reinforcing cultural continuity. Bell (1997) argues that rituals not only reflect but shape cultural patterns [16]. The sacred landscape is continually recreated through repeated pilgrimage, reinforcing community identity. As an informant states:

“When we visit these sacred places, we do not just remember our ancestors, but we also renew our bond with them. The ritual keeps our identity alive, and the meaning of these places continues to grow with each generation”.(Mochtar, 2024)

A traditional elder echoes this sentiment:

“What our ancestors did in these places is still meaningful today, but the way we perform the rituals has changed slightly. The essence remains, but every generation finds new ways to connect with our sacred land”.(Namasawar Traditional Elder, 2024)

Socially, Buka Kampung reinforces existing hierarchies while allowing generational participation, ensuring cultural regeneration. Ritual authority is held by spiritual leaders and customary elders, but youth involvement through the Lenso dance and Bala-Bala troops fosters continuity. The ritual also solidifies cultural claims to sacred landscapes, countering external pressures of modernization, migration, and development. As one elder states:

“The places we visit in Buka Kampung are not just land or old sites; they are part of our identity. Even as times change, as long as we continue this ritual, we remain connected to our past and our ancestors”.(Mocthar Thalib, 2024)

Another participant emphasizes the ritual’s role in preserving customary rights:

“If we stop performing Buka Kampung, outsiders may see these places as abandoned. But through this ritual, we show that these lands are still alive, still sacred, and still ours”.(Head of Naraya Youth Community, 2024)

Furthermore, Buka Kampung fosters engagement with communities beyond the host village. It functions as a platform for social negotiation, reinforcing alliances and preventing fragmentation amid contemporary challenges. The ritual not only preserves tradition but adapts to evolving social contexts, integrating Islamic elements while maintaining indigenous identity. Rituals can serve as adaptive mechanisms, ensuring cultural resilience [16]. In this way, Buka Kampung embodies both preservation and renewal, maintaining its significance within an ever-changing social landscape.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that the production of sacred space in Banda, particularly through the Buka Kampung ritual, is deeply rooted in historical legacy, spiritual experience, and social practices of the indigenous communities. Patterns observed in the distribution and significance of sacred sites in Namasawar and Fiat demonstrate a strong relationship between place, collective identity, and resistance narratives. These patterns directly address the core research question concerning how sacred space is formed and inherited in postcolonial indigenous contexts. The ritual enables the Indigenous community to collectively create sacred space, reestablish ties with their ancestral past, and strengthen social cohesion through traditions passed down across generations. This ritual is not merely symbolic but also a performative and cyclical act of cultural reproduction that renews spiritual connection and reaffirms communal identity. As these rituals unfold through movement and pilgrimage to sacred sites, they reproduce a social space where boundaries between the profane and sacred are blurred, forming a deeply affective spatial experience.

Drawing from the theoretical framework of Henri Lefebvre’s triad—the spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces—the findings strongly align with the idea that space is socially produced through both physical activity and symbolic meaning. The application of Arnold van Gennep’s three-phase rite of passage—separation, liminality, and incorporation—further deepens this analysis. During the Buka Kampung ritual, the separation phase entails symbolic and physical detachment from daily routines through acts like self-purification and ceremonial preparation. The liminal phase, characterized by pilgrimage and ritual acts at sites like Makam Lewetaka, Boy Sang, and Batu Masjid, suspends ordinary roles, enabling a shared state of “communitas,” as conceptualized by Victor Turner. These sacred spaces are not static locations but fluid liminal arenas that transform participants socially and spiritually. Upon incorporation, the community returns to daily life with renewed social bonds and an embedded sense of sacredness in their environment. This cyclical transition not only reshapes physical landscapes but also reinforces spatial memory and cultural continuity.

The practical implications of these findings underscore the need for community-centered heritage policies that recognize sacred sites as living, dynamic spaces rather than fixed cultural artifacts. Planners, conservationists, and policymakers must understand that rituals like Buka Kampung maintain landscape vitality and social resilience. These practices offer alternative models for spatial governance rooted in indigenous knowledge systems. Additionally, the study’s insight into intergenerational transmission and adaptive strategies in ritual practice shows how sacred space can serve as a medium for negotiating modern challenges such as migration, religious pluralism, and ecological threats. By fostering inclusion across age and gender groups—evident in roles of youth in Lenso dances and women in preparatory rituals—the ritual ensures both preservation and transformation of cultural traditions.

Nonetheless, limitations in this study include the lack of extensive geospatial mapping and reliance on oral narratives, which, while rich in cultural texture, may lack longitudinal accuracy or be subject to memory-based biases. The specificity of the Banda context may also constrain the generalizability of these findings to other indigenous groups in Indonesia or the broader Southeast Asian region. Future research would benefit from integrating participatory mapping methods, multi-sited ethnography, and cross-comparative studies to deepen our understanding of sacred geographies. Moreover, employing digital tools to document ritual cycles and sacred landscapes could enhance both scholarly understanding and cultural preservation efforts.

In light of the above, future studies should examine how sacred spatial practices evolve in response to globalization and modernity. More research is needed on the intersection of ritual, gender, and land rights, particularly in the role of women as cultural stewards. Investigating the use of technology in ritual documentation and youth engagement may also uncover new pathways for maintaining indigenous identity. As Buka Kampung shows, sacred spaces are continually reimagined through cyclical practices, narrative negotiation, and spiritual renewal—making them not only central to Banda’s past but vital to its future resilience.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The Buka Kampung ritual in the traditional villages of Namasawar and Fiat exemplifies how the Bandanese community produces, sustains, and negotiates social space and sacred landscapes. This ritual not only preserves ancestral values but also accommodates ongoing social changes, strengthening community attachment to sacred sites and reinforcing social bonds among participating groups. By providing a space for ritual and collective memory, Buka Kampung becomes a powerful tool for cultural continuity in the face of modernization.

From a cultural perspective, Buka Kampung serves as a mechanism for both preserving traditions and negotiating space for social transformation. Women in Banda have historically played a central role in maintaining land, traditions, and lineage, and they continue to be key actors in the ritual. The involvement of younger generations, such as the Mai-Mai and Bala-Bala groups, ensures the transfer of cultural knowledge and skills across generations, making Buka Kampung a dynamic mechanism for social regeneration. Buka Kampung serves as a dynamic cultural practice that both maintains and challenges existing social structures. While reinforcing the authority of traditional and religious leaders, the ritual also reshapes social roles, increasing the involvement of women and younger generations. The transformation of spatial boundaries within the ritual reflects how Bandanese society negotiates between tradition and modernity, with sacred spaces becoming more inclusive and fostering broader community participation.

Beyond its social and cultural dimensions, the ritual’s spatial expressions also have economic potential, particularly for cultural tourism. When properly planned and managed, Buka Kampung can provide economic benefits to local communities through enterprises such as cultural tourism and the marketing of handicrafts. However, striking a balance between tradition and commercialization is crucial, ensuring that indigenous communities retain control over how the ritual is presented to outsiders. Where cultural heritage (including its intangible aspects) can be included in planning and landscape design, it has the potential to enhance community engagement, preserve cultural identity, and contribute to sustainable development.

Ultimately, Buka Kampung is more than a ritual of ancestral heritage preservation—it is a dynamic mechanism for social adaptation, fostering community cohesion and ensuring that Bandanese cultural values remain relevant amid evolving social and economic landscapes. Understanding the interconnection between ritual and spatial transformation is crucial to recognizing how cultural landscapes are shaped, reproduced, and experienced over time. In this sense, Buka Kampung is a dynamic cultural practice that maintains ancestral traditions while simultaneously enabling future transformations in Bandanese society. This research contributes to heritage studies by highlighting the importance of rituals in shaping sacred spaces, and it provides insights into policy and planning efforts aimed at preserving sacred landscapes while accommodating social and economic change.

Author Contributions

H.I., S.M. and Z.R.U. developed the concept and reported the results. J.A. and N.I. collected, analyzed, and interpreted data. S.T. and S.L. supervised, reviewed, and provided consultation. R.H. and M.I.K. visualized and edited the final manuscript. M.A. reviewed and prepared the funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Directorate of Cultural Development and Utilization, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, under contract 471/F5/KB.18.05/PPK II/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study adheres to strict ethical principles by obtaining permission from local authorities, clearly explaining research objectives to informants, and securing their consent. Respect for cultural norms and restrictions surrounding sacred information is paramount, alongside ensuring community participation and representation.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are not available.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the support of the Directorate of Cultural Development and Utilization MoECRT, Centre for Landscape, Newcastle University, United Kingdom, Universitas Banda Naira, community representatives in the Banda Islands, and other involved parties who helped us with this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Averbuch, B. The Spice Trade in Southeast Asia. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hägerdal, H. History of the Banda Sea. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cillia, G. Spices, Exotic Substances and Intercontinental Exchanges in Early Modern Times. Master’s Thesis, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Venice, Italy, 2021. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14247/10594 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Hägerdal, H. Contact zones and external connectivities in southern Maluku, Indonesia: A reassessment of colonial impact, trade, and autonomous agendas. Indones. Malay World 2019, 47, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, G. Hunting and farming in prehistoric Italy: Changing perspectives on landscape and society. Pap. Br. Sch. Rome 1999, 67, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, V. Symbolic studies. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1975, 4, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Donkersgoed, J.; Farid, M. Belang and Kabata Banda: The significance of nature in the adat practices in the Banda Islands. Wacana J. Humanit. Indones. 2022, 23, 415–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirabatij, M.S.; Donkersgoed, J.V., Translators; Hikayat Banda Lonthoir: Stories from Orang Kaya Lonthoir M.S. Neirabatij; Het Scheepvaartmuseum: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lape, P. On the use of archaeology and history in Island Southeast Asia. J. Econ. Soc. Hist. Orient 2002, 45, 468–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, H. Tradisi Buka Kampong Desa Adat Fiat Kecamatan Banda. Banda Hist. J. Hist. Educ. Cult. Stud. 2023, 1, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uneputty, T.; Thalib, U.; Nanlohy, M.; Berhitu, B.; Batkunda, A. Upacara Tradisional Yang Berkaitan Dengan Peristiwa Alam dan Kepercayaan Daerah Maluku; Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1985. Available online: http://repositori.kemdikbud.go.id/id/eprint/12236 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Tripathi, D. Decolonization. In The Impact of Wars on World Politics, 1775–2023: Hope and Despair; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Ferrer, L.; Egea-Vivancos, A. Thinking like an archaeologist: Raising awareness of cultural heritage through the use of archaeology and artefacts in education. Public Archaeol. 2017, 16, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, R. On the Edge of the Banda Zone: Past and Present in the Social Organization of a Moluccan Trading Network; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The production of space (1991). In The People, Place, and Space Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C.M. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- van Gennep, A. The Rites of Passage; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Haggar, S. Communitas revisited: Victor Turner and the transformation of a concept. Anthropol. Theory 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtorf, C. Embracing change: How cultural resilience is increased through cultural heritage. World Archaeol. 2018, 50, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwig, K.R. The practice of landscape ‘Conventions’ and the just landscape: The case of the European landscape convention. In Justice, Power and the Political Landscape; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Knez, I. Place and the self: An autobiographical memory synthesis. Philos. Psychol. 2014, 27, 164–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, I.; Eliasson, I. Relationships between personal and collective place identity and well-being in mountain communities. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stobbelaar, D.J.; Pedroli, B. Perspectives on landscape identity: A conceptual challenge. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Place: An experiential perspective. Geogr. Rev. 1975, 65, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, R. A rooted sense of place in cross-cultural perspective. Can. Geogr./Le Géographe Can. 1998, 42, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Sense of place. In The International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Bahauddin, A.; Prihatmanti, R.; Putri, S.A. ‘Sense of Place’ on sacred cultural and architectural heritage: St. Peter’s Church of Melaka. Interiority 2022, 5, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Is it really just a social construction?: The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pred, A. Place as historically contingent process: Structuration and the time-geography of becoming places. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1984, 74, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D. Body-subject, time-space routines, and place-ballets. In The Human Experience of Space and Place; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 148–165. [Google Scholar]

- Punter, J. Participation in the design of urban space. Landsc. Des. 1991, 200, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wensing, E. The Right to Landscape: Contesting Landscape and Human Rights; Taylor & Francis: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play; Performing Arts Journal Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V. The Rites of Passage; Vizedom, M.B.; Caffee, G.L., Translators; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V.; Abrahams, R.; Harris, A. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Granero, F. Writing history into the landscape: Space, myth, and ritual in contemporary Amazonia. Am. Ethnol. 1998, 25, 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersapati, M.I.; Setiadi, H. Semiotic Study of Settlement’s Spatial Pattern in Kuningan Regency, West Java. J. Geogr. Lingkung. Trop. 2021, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Donkersgoed, J. Shifting the historical narrative of the Banda Islands From colonial violence to local resilience. Wacana J. Humanit. Indones. 2023, 24, 500–514. [Google Scholar]

- Darman, F. Mitos dalam Upacara Adat Masyarakat Pulau Banda, Kabupaten Maluku Tengah; Kantor Bahasa Maluku, Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan: Ambon, Indonesia, 2017.

- van Engelenhoven, A. (Ed.) Oral Traditions in Insular Southeast Asia: Lokaswara Nusantara; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alwi, D. Sejarah Maluku, Banda Naira, Ternate, Tidore, dan Ambon; Dian Rakyat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2005; ISBN 9795237012. [Google Scholar]

- STP & STKIP Hatta-Sjahrir. Pariwisata Adat Pulau Naira: Buku Narasi Situs Adat Pulau Naira; Central Maluku, Indonesia: Maluku, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kastanya, H. Bahasa dan Sastra Lisan Kepulauan Banda Dalam Perspektif Poskolonial; Kantor Bahasa Maluku, Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan: Ambon, Indonesia, 2017.

- Swadiansa, E.; Adiyanto, J. Banda 3 Zaman: Berkah, Petaka, dan Harapan; Government Central Maluku: Maluku, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Farid, M.; Sadée, J. Mama lima. the significance of women’s role in protecting nature, nurture, and culture in Banda Islands. Wacana J. Humanit. Indones. 2023, 24, 284–309. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).