Abstract

The transfer of development rights (TDR) is a legal instrument, introduced in 1961, that allows transferring of development rights from a land parcel where restrictions are imposed (sending parcel) to another land parcel (receiving parcel). TDRs aim to ensure environmental and cultural heritage protection with respect to the rights of individual land parcel owners, thus constituting a high impact tool in sustainability and urban planning. Although extensive research has been applied in defining development rights’ transfer zones (RTZ), mainly in the proximity of the sending parcels, limited is the research on defining this “proximity”. This research examines the process of identifying the areas that can host RTZs, using as a case study the implementation of TDR in Greece. Greek TDR legislation was challenged by the Hellenic Council of the State as non-conformant to the principles of rational urban and spatial development, thus requiring the identification of the areas that can host rights’ transfer zones. In order to align with the Council’s decisions, the Ministry of Environment and Energy introduced Law 4759/2020 along with Technical Requirements for the delineation of development rights’ transfer zones. Given that restrictions on the transfer of development rights do not exist in all municipalities in Greece, multi-criteria analysis was used to propose municipal units where studies on development rights’ transfer zones (RTZs) could be conducted, based on the number of sending parcels, geographic and urban planning requirements, and funding limitations. The analysis resulted in 83 municipal units, covering about 75% of the country’s need for development rights’ transfer. The deployment of RTZ studies in the selected areas would benefit the owners of the restricted land parcels (where existing TDR titles are currently inactive or where new ones cannot be issued) and assist urban space management.

1. Introduction

Urban planning is a complex process that involves balancing economic, social, and environmental factors to increase the sustainability and efficiency of modern cities. Planning shapes patterns of growth, the location of public facilities, economic development, environmental protection, and the sustainability of communities [1]. Intense urbanisation and the concomitant vertical exploitation of land results in overlapping and conflicting rights in 3D space. Consequently, land rights need to be restricted in content and/or extent in order to serve the public benefit. This brings up the concept of Public Law Restrictions (PLRs)1, which are restrictions imposed by the state on individual owners, to secure public benefit. PLRs are imposed on land for various purposes, including mineral exploitation, environment protection, regulation of aviation (manned and unmanned), development and maintenance of utilities, and urban and spatial planning [2,3]. Urban planning-related PLRs include, among others, construction regulations as well as regulations for the protection of cultural heritage. Within the urban environment, the protection of cultural heritage has to do, among others, with the declaration of buildings of architectural or historic importance as “listed buildings”, restricting potential interventions that may affect their appearance and character or even forbid their demolition. Hence, restrictions on privately owned listed buildings limit the rights of the land parcel owners in fully exploiting their property, resulting in a need for compensation. In most cases, listed buildings are located in historical city centres with advantageous development rights and, consequently, are of high land value. In order to avoid compulsory purchase and minimise compensation resources, the Transfer of Development Rights (TDR)2 legal instrument was introduced [4,5], allowing transfer of development rights from a land parcel where restrictions are imposed to another land parcel which may “host” the restricted development. TDRs were first introduced in the United States in 1961 [6], with TDR programs implemented in several states for numerous purposes, including building conservation, coastal conservation, and land development or redevelopment [7,8,9]. TDR concepts have expanded worldwide, with the implementation of TDR programs globally [10,11,12,13,14,15].

Given that the implementation of TDRs is a planning instrument of high impact where applied and relates to multiple factors, e.g., environmental conditions, socioeconomic conditions, the capacity of infrastructures and utilities, and population density, locations where the “restricted” development rights will be transferred need to be examined in detail. This brings up the role of modern analytical tools to process and evaluate multiple data of a different nature, in order to identify the locations best suited to receive transferred development rights. Moreover, the need for examining the spatial characteristics of the “encumbered” and the “receiving” land parcels may be served through the use of Geographical Information Systems (GIS), which allow spatial data analysis, modelling, mapping, and visualisation. Therefore, GIS-based multi-criteria analysis can be applied to support the decision-making process. Multi-criteria analysis is a tool that is commonly used and allows territorial analysis combined with multiple different or even contradictory actors [16]. Multi-criteria analysis methods were initiated in the 1960s and first combined with GIS systems in the 1980s [17]. The literature provides a variety of multi-criteria analysis applications. In the field of urban and regional planning, GIS multi-criteria analysis plays a dominant role, especially as regarding resource allocation, plan/scenario evaluation, site search/selection, and land suitability problems [17]. In [18], multi-criteria analysis is used to evaluate a city’s performance as compared to six spatial layout alternatives. Within the same context, ref. [19] uses multi-criteria analysis for the classification of urban streets to provide a guiding tool for public spending with the perspectives of urban sustainability. Finally, applying multi-criteria analyses in site search or selection is common in cases of infrastructure establishment, e.g., industrial parks, windfarms, and photovoltaic power plants [20,21,22], or for the investigation of city expansion areas [23].

In Greece, although legislation on development rights’ transfer dates back to 1979, this legal instrument remains inactive, as it has been ruled out by the Hellenic Council of the State (the Supreme Administrative Court in Greece), due to its non-conformance to the principles of rational urban and spatial development. Attempts to regulate this issue by introducing new legislation (1995, 2002) were as well ruled out by the Hellenic Council of the State. In 2017, legislation on TDRs was re-introduced, aiming to conform to the Hellenic Council of the State objections, further amended by Law 4759/2020.

In the light of the Greek Urban Policy Reform, funded by the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF)3, development rights’ transfer zones (RTZs)4 studies were included. In order to the optimise cost and time effectiveness of the RTZs studies, this work applies a GIS multi-criteria analysis for the identification of municipal units appropriate for conducting RTZ studies. Within this context, legal and juridical statutes, urban planning criteria, and spatial analysis tools are combined to a data-driven decision support tool for urban planning and heritage preservation.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: In Section 2, the historical development of the transfer of development rights in Greece is presented, along with the rulings of the Hellenic Council of the State, until the introduction of Law 4495/2017, which is currently in force. Section 3 presents the methodology applied and the data used to conduct this research. In Section 4, the results of implementing the multi-criteria analysis are shown. Finally, in Section 5 the results are discussed, followed by concluding remarks.

2. Transfer of Development Rights in Greece

The transfer of development rights was established in Greece by the Law 880/1979 [24], aiming to introduce compensative measures for constitutional restrictions imposed on specific cases of real property objects. According to the Greek Constitution [25], “Monuments and historic areas and elements shall be under the protection of the State. A law shall provide for measures restrictive of private ownership deemed necessary for protection thereof, as well as for the manner and the kind of compensation payable to owners” (art. 24, par. 6). Within this context, Law 880/1979 allowed the transfer of development rights from a number of “encumbered” real property objects (e.g., listed buildings, land parcels on areas of special building conditions, and other types of Public Law Restrictions), to the same land parcel or to another land parcel. A Presidential Decree [26] specified the transformation of development rights from the “sending” parcel to the “receiving” parcel, while another Presidential Decree [27] was issued to regulate the administrative procedures of development rights’ transfer.

In 1994, the Hellenic Council of the State ruled out all provisions on development rights’ transfer as non-conformant to the principles of rational spatial and urban planning development as well as to the principle of built environment protection. According to the ruling of the Hellenic Council of the State, development rights should only be transferred to specific areas, which are designated based on objective spatial and urban planning criteria.

In 1995, Law 2300 [28] was introduced, aiming to replace Law 880/1979 and regulate the transfer of development rights based on the Hellenic Council of the State decisions of 1994. Law 2300 defined specific areas where development rights could be “received” as well as specific criteria regarding the implementation of the transfer process. However, decisions [29,30,31] of the Hellenic Council of the State ruled out Law 2300 on the grounds of non-conformance with par. 2 and 6 of art. 24 of the Constitution, regarding protection of the natural and cultural environment. The decisions of 1994–1996 of the Hellenic Council of the State have defined the regulatory framework regarding development rights’ transfer. “Receiving” land parcels were limited to those for which constitutional provisions allow for the conversion of financial compensation to “in kind” (development rights) compensation. Therefore, “sending” parcels were restricted to land parcels with listed buildings, historical monuments, and archaeological sites, thus excluding land parcels (or parts of land parcels) that are expropriated for public space or public facilities and can only be financially compensated.

In 2002, art. 17 of the Greek Constitution on property protection was amended, providing, under consent of land parcel owners, for “in kind” compensation. In the same year, Law 3044 [32] was introduced, aiming to reactivate the transfer of development rights. Law 3044 defined specific criteria for the transfer of development rights in specific zones (Development Right Purchase Zones). Again, the Hellenic Council of the State ruled out Law 3044 (indicatively decisions [33,34,35,36]). According to the Hellenic Council of the State, transfer of development rights relates to art. 17 and 24 of the Constitution, and it is of a compensatory character. Therefore, it needs to be seen in the context of spatial planning, both in terms of defining “receiving” parcel zones and of the impacts of the added development rights.

In 2017, Law 4495 [37] on the protection of the built environment was introduced. Part C of Law 4495 aims to activate the transfer of development rights, in compliance with the limitations set by the previous Hellenic Council of the State rulings. Law 4495 (amended by Laws 4759/2020 and 5147 in 2024) provides for the definition of dedicated areas where development rights can be transferred (RTZs), taking into account their spatial layout as well as their capacity to receive transferred rights. Art. 72 of Law 4495 defines the characteristics of the areas where RTZs can be defined and sets out exclusion characteristics, thus contributing to the protection of the cultural and built environment, with respect to the property rights of the restricted parcels’ owners.

3. Materials and Methods

As previously mentioned, the aim of this work is to identify the municipal units on which development rights’ transfer zones will be investigated. The selection of a municipal unit level approach relates to the aim of this work (minimising the number of RTZ definition studies) and the administrative divisions of Greece. In 2011, the decentralised administration in Greece was restructured by merging the existing 1,034 municipalities to 325 municipalities. Former municipalities now constitute the municipal units of the 2011 municipalities. Therefore, the municipal unit level is a smaller unit that facilitates the investigation performed in this research.

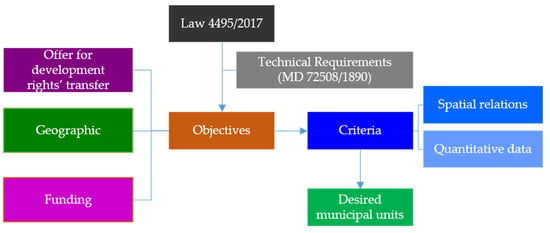

For the implementation of this work, the following methodology was applied, as schematically presented in Figure 1. First, the selection objectives were defined, as described in Section 3.2. Next, the indicators that define each objective were identified, based on the legislation regulating RTZs [37,38]. As aforementioned legislation refers to the process of evaluating urban land for its suitability to host RTZ, analysis within the context of this research goes to less detail level aiming to identify the municipal units that are either suitable to host RTZ, or include a large number of encumbered parcels, so they need to be separately examined. Parameters that are defined descriptively need to be described spatially or quantitatively. After the definition of the indicators against each municipal unit will be evaluated, data was imported to the GIS software, so that spatial analysis can be performed. Depending on the examined indicators, the outcome municipal units derived either through spatial relations, or based on their evaluation on the examined indicators.

Figure 1.

Methodology.

3.1. Methodology

In order to propose the municipal units for which investigation on conducting RTZ studies can be implemented, the objectives (the key aims against which the proposed options are assessed and compared [39]) need to be clearly defined [40,41,42]. There are various sources that can be used to develop a list of objectives, which can include planning and policy documents, general guidelines developed by government departments, agencies, or scholars, evaluation report documents, reports, interviews, and surveys [39].

Art. 70 of [37] defines the characteristics of encumbered land parcels (“sending” parcels), from which development rights can be transferred. These include

- Land parcels that are expropriated for public space or public facilities;

- Land parcels with restrictions for the protection of architecture or natural heritage;

- Land parcels where construction restrictions are imposed due to regulations on archaeological and cultural protection, including archaeological sites and historic places.

The land parcels for which development rights from encumbered parcels can be transferred (“receiving parcels”) need to be situated in dedicated zones (Rights’ Transfer Zones—RTZs) [37] (art. 71). According to art. 72 of [37,38], RTZs can be relocated to areas with the following characteristics:

- Within areas where the urban planning process started with a regulatory act or within approved settlement boundaries;

- Outside historic places, traditional settlements, archaeological sites, or areas where construction limitations are applied for the protection of traditional architecture, archaeological sites, and sites with significant cultural or environmental characteristics;

- Outside historical centres;

- Outside protected areas;

- Outside the first two blocks from the shoreline;

- Outside blocks where the slope is greater than 25%;

- Outside blocks that are neighbouring forest areas.

A Ministerial Decision [38] further specifies the desirable characteristics during the investigation of RTZs as regarding land use and infrastructure as the following:

- Prevalent land use is other than for residence, so that the potential increase of building rights shall not lead to a significant population increase, thus stretching the demands on infrastructure and utilities;

- Are areas of production activities;

- Are areas that are designated for urban plan extension;

- Are pure residential areas of low building density in which a potential increase will not degrade quality of life;

- Are urban renewal areas.

It is noted that special provisions or exemptions may apply to some of the aforementioned characteristics. Such provisions were not described above, as they do not affect the analysis of this work and would increase the complexity for the readers.

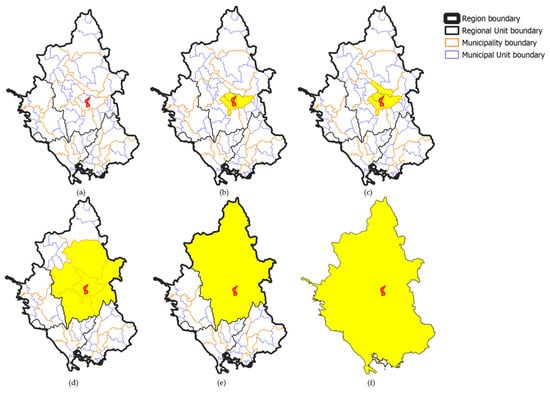

According to the Ministerial Decision [38], development rights of each “sending” parcel can be transferred to RTZs located to the same municipal unit (Figure 2a). If there is no space that fulfils the requirements for RTZs within this municipal unit, they may be transferred to RTZs located in neighbouring municipal units (Figure 2b) or within the municipality (Figure 2c). If no RTZs are available within the municipality, transfer may apply to RTZs in neighbouring municipalities (Figure 2d). If no “receiving” parcels are available, investigation may extend within the Regional Unit (Figure 2e) or, finally, to an RTZ established within the Region (Figure 2f).

Figure 2.

Example of potential transfer of development rights at municipal unit level (a), neighbouring municipal units in the same municipality (b), municipality level (c), neighbouring municipalities (d), Regional Unit level (e), and Region level (f).

3.2. Objectives

Setting the objectives is of crucial value for conducting multi-criteria analysis [40]. Objectives need to be specific, measurable, agreed upon, realistic, and time dependent [40]. The definition of the objectives of this research is related to the following aspects:

- The quantity of encumbered parcels and of non-materialised titles of development rights’ transfer: This objective relates to the definition of the municipal units that will be investigated for the development of RTZs, based on the number of parcels with listed buildings and the number of issued titles of development rights’ transfer.

- Geographic and urban planning requirements. Geographic and urban planning requirements are associated with spatial relations between municipal units with a high number of “sending” and “receiving” parcels. They also relate to the existence of areas in need of increased development rights, avoiding population increases that would result in an excessive need for infrastructure and utilities (e.g., industrial areas). Moreover, limitations for the protection of areas of unique character and traditional architecture need to be considered within this objective.

- Funding limitations: According to a Ministerial Decision [43], RTZs may also be investigated within the preparation of Local Urban Plans (LUPs)5 and Special Urban Plans (SUPs)6. The development of LUPs/SUPs constitutes part of the National Urban Policy Reform that is currently ongoing in Greece, covering 227 municipalities throughout the country and funded by the RRF, as it applies to the development of RTZ study. Therefore, municipal units where LUPs and SUPs are conducted are excluded from the study for the development of RTZs. The difference between the two programs is that LUPs are related to the holistic reform of the national urban policy and the relevant planning system that horizontally affects a wide range of policy areas, including environmental protection and adaptation to climate change, built environment and development, protection of historic sites and buildings, allocation of public infrastructure, and allocation of investments [44], while the development of RTZ study focuses specifically on transferring building rights from encumbered land parcels and listed buildings. Moreover, the establishment of RTZs within LUPs may apply only in cases where “receiving“ parcels cover the needs set by the “sending” parcels. RTZ study emphasises municipalities where the “receiving” area cannot absorb the “sending” one; thus, the investigation for “receiving” parcels needs to be extended to neighbouring municipal units, neighbouring municipalities, municipalities within the same Regional Unit, or municipalities within the Region. Given the different aims of these two projects, municipal units where it can be justified that there are not enough “receiving” parcels to cover the offer of “sending” parcels may be included in the individual project for the development of RTZs.

3.3. Setting the Indicators Based on the Objectives

In this section, the indicators against which municipal units are evaluated for the development of RTZs are investigated based on the objectives defined in the previous section. A summary of the aforementioned objectives and their related indicators is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of objectives and criteria applied to the multi-criteria analysis.

- Τhe quantity of encumbered parcels and non-materialised titles of development rights’ transfer in each municipal unit (Objective 1 described in Section 3.2) is unequivocally of a numerical nature; thus, the indicator to be used for its evaluation is the number of “sending” parcels in each municipal unit as well as the number of development rights’ transfer titles that have been issued based on previous legislation and have not materialised. The more “sending” parcels and non-materialised titles that exist in a municipal unit, the higher priority this municipal unit has to be selected for the development of RTZs. It is noted that existing titles of development rights’ transfer are titles that have been issued under revoked legislation regulating the transfer of development rights and cannot yet be “received” by another parcel.

- Geographic limitations relate to the location of municipal units with large numbers of “sending” parcels and non-materialised titles and alternatives for the allocation of “receiving” parcels, extending gradually from neighbouring municipal units to municipalities within the same Region, as shown in Figure 2. Therefore, geographic relations constitute spatial indicators, based on the location of the municipal units identified in Objective 1. Urban planning requirements are combined in this research with geographic ones, as jurisprudence of the Hellenic Council of the State sets geographic limitations by excluding, inter alia, shores and islands from “receiving” areas due to urban planning purposes [45,46].

- Funding limitation indicators are also of a spatial connotation. Municipal units where LUPs are conducted, funded by the RRF, are excluded from the investigation. However, exceptions may apply for municipal units with an excessive number of “sending” parcels and issued titles of development rights’ transfer. In such cases, for the excepted municipal units, investigation for RTZs is not conducted within the LUP study, while investigation of the “receiving” parcels extends, gradually, from neighbouring municipal unit level to municipalities within the administrative Region.

3.4. Materials

Given that this research pertains to the examination of spatial relations, examination and evaluation of numerical data, and existence of specific infrastructures and utilities, all based on descriptive legal statutes, it is clear that a variety of data is required.

Specifically, descriptive regulations on defining RTZs were extracted from legislation [37,38], also contributing to the deployment of the methodological steps that applied to this research.

In order to investigate spatial relations as described earlier in the methodology description, the administrative division of Greece is used, available in vector format by the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) [47]. According to its administrative division, Greece is divided in 13 administrative Regions that pertain to 75 Regional Units. Regional Units comprise 326 municipalities, which are further divided into 1035 municipal units [48,49].

Information on the number of listed buildings and issued titles of development rights’ transfer per municipal unit and per municipality was provided by the Department of Public Open Spaces Reservation and Building Coefficient Transfer of the Ministry of Environment and Energy in numerical data format. It is noted that since July 2024, the Ministry of Environment and Energy has launched an online webmap (ESTIA) [50], where listed buildings and traditional settlements of Greece are presented, along with descriptive information related to each building or traditional settlement. Given that this research preceded the development of the ESTIA webmap, the vector data of ESTIA were not used in this research. However, the numerical data used for this research are the same as those presented in the ESTIA webmap; therefore, this does not affect the results of this work. It is noted that apart from the ESTIA webmap, a digital Archaeological Cadastre was developed by the Directorate of National Archives and Monuments, presenting immovable monuments, archaeological sites, historical sites, and their protection zones for more than 17,000 monuments, approximately 3400 archaeological sites and historical sites, 844 protection zones, and 220 museums in Greece [51]. Data listed in the Archaeological Cadastre were not used in this research, as the objects and zones shown in the Archaeological Cadastre do not set restrictions at the municipality or municipal unit level and may apply as restriction zones during the stage of investigating RTZs within the selected municipal units.

Municipal units where LUPs and SUPs funded by the RRF were conducted were provided by the General Secretariat of Spatial Planning and Urban Environment of the Ministry of Environment and Energy in vector format.

Industrial areas were provided in vector format by the Ministry of Development, while the subway network lines were recovered from the Public Sector Open Data Registry, where public sector datasets and links to the websites or institutions where data are maintained are available to the public [52].

A summary of the data used in this research is shown on Table 2.

Table 2.

Data used for multi-criteria analysis.

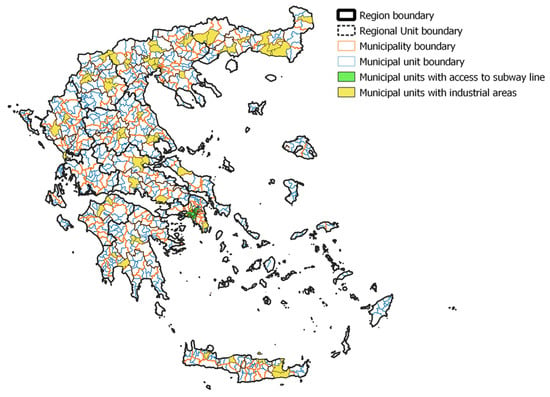

4. Implementation of the Multi-Criteria Analysis

Having set the methodological framework as well as the data used for this research, implementation of the multi-criteria analysis could proceed. It is noted that for the implementation of the geospatial analysis part of the research, QGIS software was used. In the first step of conducting this analysis, the cartographical background was set by introducing vector data to the GIS software. Next, numerical data regarding the number of listed buildings and the number of issued titles for transfer of development rights were related to their spatial counterparts, the municipal unit and municipality. Figure 3 presents the background map, including the boundaries of municipal units, municipalities, Regional Units and Regions. Subway lines and industrial areas are shown at the municipal unit level on the same figure for readability purposes.

Figure 3.

Background map showing administrative division of Greece: municipal units with industrial areas and municipal units with access to subway lines.

The analysis started by evaluating municipal units based on their number of listed buildings. Evaluation was also made based on the number of issued titles of development rights’ transfer per municipality. Both evaluations were related to Objective 1, described in Section 3.2, and aimed to identify the municipal units with a high number of “sending” parcels.

Next, the geographic requirements were applied, by excluding municipal units on islands. In this step, municipal units that could serve as “receiving” areas in the proximity of highly evaluated “sending” municipal units were also identified (Objective 2 described in Section 3.2).

Finally, the identified municipal units from the previous steps were compared to the municipal units where LUPs/SUPs were conducted, to be excluded from selection. However, municipal units with high numbers of “sending” parcels were exempted from this exclusion (Objective 3 described in Section 3.2).

4.1. Objective 1

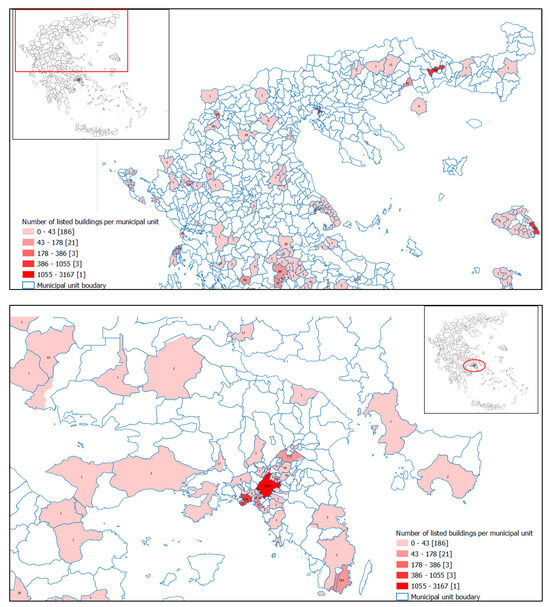

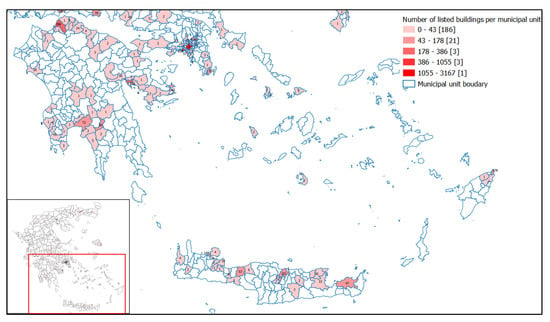

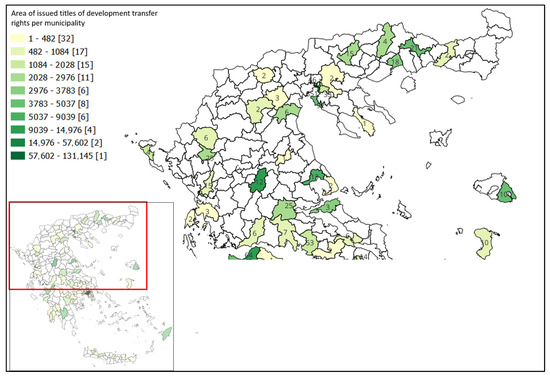

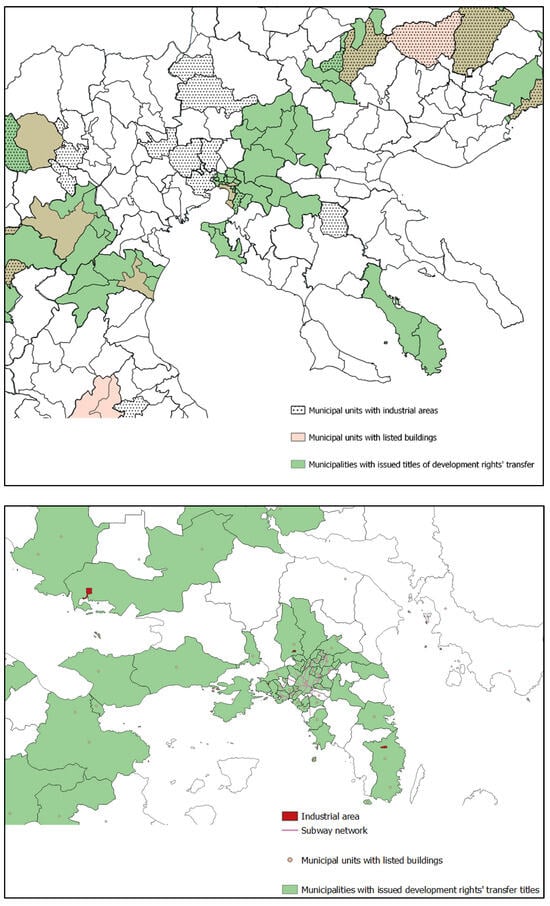

According to Objective 1, the municipal units where the most listed buildings exist need to be extracted, also considering the number of issued titles of development rights’ transfer. Figure 4 presents the number of listed buildings per municipal unit, while the area in square metres of issued titles per municipality is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Number of listed buildings per municipal unit. Top: Northern and Central Greece: middle: Attiki Region; bottom: Southern Greece. The exact number of listed buildings is shown on each municipal unit’s centroid. Inside the brackets, the sum of municipal units falling into each of the five categories is shown.

Figure 5.

“Sending” area in municipalities with issued titles. Top: Northern and Central Greece; middle: Attiki Region; bottom: Southern Greece. Inside the brackets is the number of issued titles pertaining to each category.

Both figures show that there is a high level of variance between the number of listed buildings in each municipal unit as well as between the number of municipalities with issued titles. In the latter case, it is not only the number of issued titles, but the transferable area deriving from these titles that needs to be considered, as the number of issued titles does not always correspond to a high transferable area. It can be noted that there is a small number of municipalities/municipal units, mainly found in the large urban centres, where most listed buildings and issued titles are traced. A high number of “sending” parcels is also found in cities with historic centres, where construction limitations are imposed for the protection of their unique character. As shown in Figure 4, there are 186 municipal units with less than 43 listed buildings (a total of 9397 listed buildings), while more than 43 listed buildings are found in 28 municipal units (summing to a total of 8414 listed buildings, out of which 3167 are located within the city of Athens). The mean number of listed buildings per municipal unit is 16 if municipal units with no listed buildings are included to the calculations, while this increases to 43 if selection is restricted to municipal units with listed buildings.

This similarly applies in the case of issued titles of development rights’ transfer. The majority of development rights’ transfer titles were issued in highly populated municipalities, with high urban concentrations and historic centres (e.g., the city of Athens and the Attika conurbation, Thessaloniki, Patra, Iraklion, Volos, Rhodes, Ioannina, Chania), and their neighbouring municipalities, in accordance with the legislation regulating the transfer of development rights at the time.

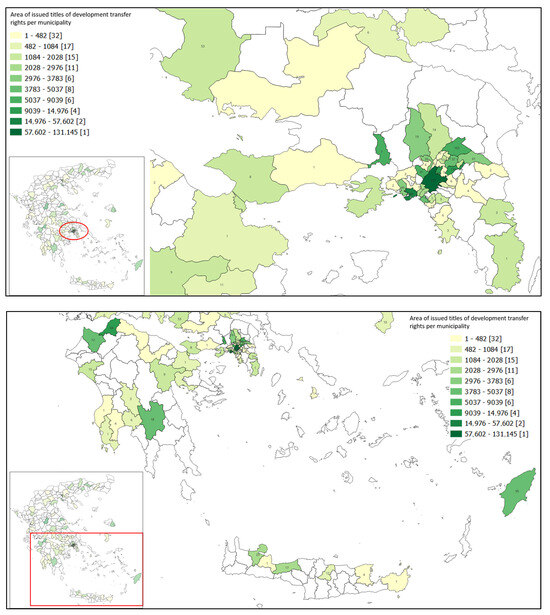

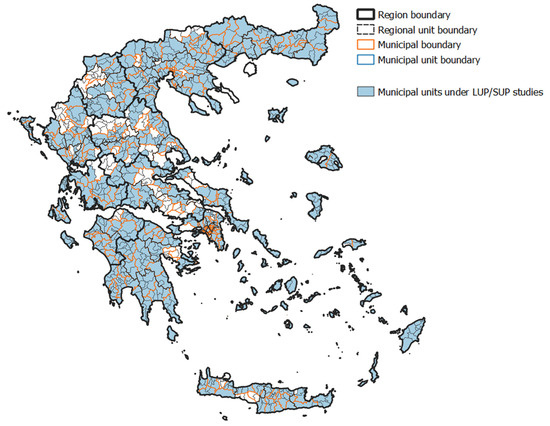

4.2. Objective 2

This objective investigates spatial relations between municipal units. The indicators used are based on the proximity of each municipal unit to municipal units with high numbers of “sending” parcels (neighbouring, within the same municipality, in neighbouring municipality, within the same Regional Unit, or within the same Region) to the existence of areas that can serve as “receiving” areas without bringing population increase and exceeding the region’s capacity for infrastructure and utilities (e.g., industrial areas, municipalities served by the subway network). Finally, exclusion areas are defined based on the jurisprudence of the Hellenic Council of the State, which excludes shores and islands from “receiving” areas. It is noted that the fact that islands are excluded from “receiving” areas aims to prevent accumulation of transferred rights on islands and does not mean that “sending” parcels will not be able to transfer their development rights. “Receiving” parcels in such cases will be investigated, at the municipal level, within the LUP. All municipalities with “encumbered” parcels, issued titles of development rights’ transfer, and municipal units with industrial areas at the country level are shown in Figure 6 (top) as well as in the Region of Central Macedonia in Northern Greece (middle) and in the Region of Attika (bottom).

Figure 6.

Municipalities and municipal units with “sending” parcels, location of industrial areas, subway network lines (top: country level, middle: Central Macedonia Region, Bottom: Attika Region).

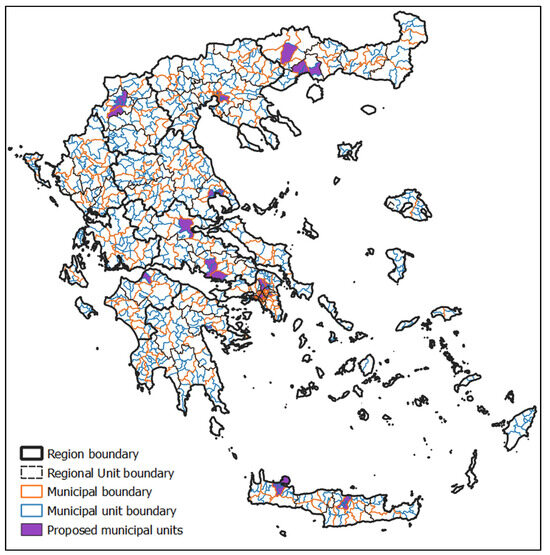

4.3. Objective 3

The aim of this objective is to exclude from selection the municipal units where studies on LUPs and SUPs are conducted. LUPs and SUPs are in progress in 227 municipalities (LUPs) and seven municipalities (SUPs) throughout the country. Investigation of RTZs may also be conducted within the LUP study. However, RTZs in such cases may not be investigated outside the LUP area; therefore, the “sending” area within the LUP area needs to be equal to the “sending” area. This may apply in municipalities with a small number of listed buildings and issued titles of development rights’ transfer, but as the number of listed buildings and the “sending” area deriving from issued titles grows, the need to expand the level of investigation emerges. In this case, investigation of RTZs is not conducted within the LUP or SUP but falls into the dedicated study for the development of RTZs, and the municipal units involved are exempted from this exclusion. Figure 7 presents the municipal units where LUPs and SUPs are conducted.

Figure 7.

Municipal units under study for the development of LUPs/SUPs.

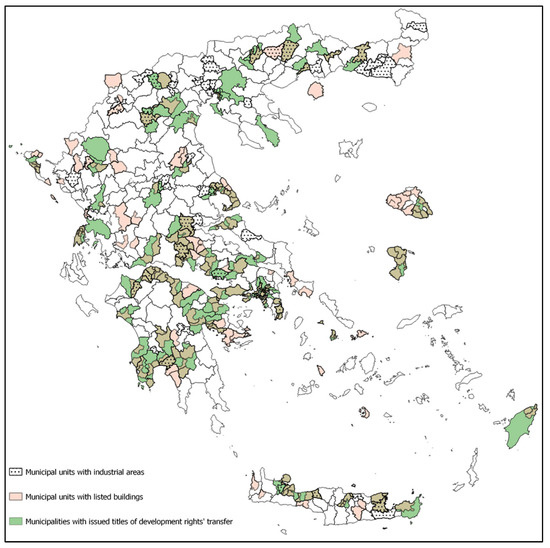

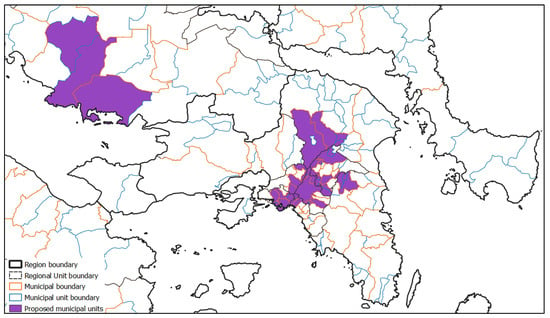

5. Results

Based on the findings of the preceding analysis, the selection of the municipal units that can host studies for the definition of RTZs resulted in 83 municipal units throughout the country (Figure 8). Selected municipal units

Figure 8.

Top: Proposed municipal units resulting from the multi-criteria analysis. Bottom: Proposed municipal units in the Attika Region.

- Are those with the highest number of listed building and issued titles, regardless of their selection for LUP/SUP studies.

- Have established industrial areas, where increase of development rights will not result in population increase.

- Have access to the subway network.

- Are of low construction density, neighbouring municipal units with a high number of listed buildings or issued titles of development rights’ transfer. Such municipal units were selected even if their number of listed buildings or issued titles of development rights’ transfer was limited.

Selected municipalities include 5758 listed buildings and 3707 issued titles of development rights’ transfer, covering a total area of 393,894 m2. Table 3 briefly presents the main features related to the demand on RTZs covered by the selected areas.

Table 3.

Number of listed buildings, issued titles of development rights’ transfer, and corresponding area of the selected municipal units.

Municipal units that were not selected include islands, due to limitations deriving from jurisprudence of the Hellenic Council of the State, as described in Section 3.3. It is noted that non-selected municipal units with “sending” parcels are either selected for LUP study or constitute neighbouring municipal units, neighbouring municipalities, municipalities within the same Regional Unit, or municipalities within the same Region where individual RTZs studies will be conducted; therefore, their needs in “receiving” parcels will be covered.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This work presented the workflow of conducting a multi-criteria analysis for the selection of municipal units in Greece, where studies for the definition of RTZs could be conducted. Selection involved a variety of parameters, including geography, urban and spatial planning, spatial relations, and funding, for achieving time and cost effectiveness.

The analysis was based on the legislation regulating the transfer of development rights in Greece, Law 4495/2017 and the Ministerial Decree on defining the Technical Requirements for the implementation of studies for the definition of RTZs. However, the purpose of this work was to identify which municipal units throughout the country were most appropriate for RTZs. Therefore, the methodology described in the statute was adjusted to fit the aim of this research.

Apart from the need for the adjusting in-statute methodology (which regulates the identification of RTZs) to fit to the aim of this research (to identify the municipal units that could host RTZs), the following challenges were also faced:

- Data heterogeneity: The available data came from different administrative levels (municipal unit level and municipality level). Although municipalities constitute municipal units, and their spatial relations could be derived using GIS, this did not allow for analysis of all data on the municipal unit level.

- Investigation at municipal unit level: The selection of municipal units for this research was based on the administrative division of Greece and on the specific characteristics of this research. Investigation at the municipality level would lead to the selection of municipal units (within the municipality) not suitable for RTZ definition studies, increasing time and cost. On the other hand, investigation at the building block or land parcel level would actually mean conducting the RTZ definition studies for the whole country.

- Process automation: The specifications of this research (in terms of geographic characteristics and funding limitations) did not allow for fully automating the selection process. For example, excluded municipal units due to low number of “sending” parcels could be finally selected (as suitable “receiving” municipal units). Therefore, the selected and excluded municipal units were manually cross-checked.

The contribution of the identification of the municipal units that could host RTZs in Greece impacts both individuals and urban planning policy. As regarding individual owners, the definition of RTZs would allow them to transfer existing titles that have remained inactive for almost 20 years. Moreover, owners of the listed buildings would be able to issue TDR titles, thus being compensated for the restrictions imposed on their properties. In terms of the impacts on urban planning policy, these include the efficient protection of the cultural environment and the organisation of urban space. By limiting potential RTZs to specific municipal units that fulfil specific characteristics, environmental and urban planning impacts are minimised. Moreover, this prevents speculation on the land market, especially in densely populated or protected municipalities/municipal units.

Multi-criteria analysis constitutes a powerful tool to support decision making, by combining and analysing aspects of different characteristics and nature. In the field of urban planning, where the sustainable management of space, population, and resources is required, multi-criteria analysis may play a valuable role by analysing all aspects related to urban planning projects, saving time and preventing territorial or environmental conflicts. Urban planning strongly relates to spatial characteristics and relations. This brings up the role of GIS systems in analysing complex interrelations between multiple factors with spatial counterparts.

GIS provides a convenient, time and cost effective tool to analyse, model, and represent spatial data, thus leading to comprehensive, clear, and objective outcomes. Therefore, the main challenge for implementing multi-criteria analysis using GIS systems lies to the elaboration of the studied project’s aims and anticipated outcomes, so that objectives and their related indicators are identified for inclusion in the analysis. The contribution of artificial intelligence tools in identifying objectives and indicators for multi-criteria analyses is a subject that could be investigated in future research. However, it needs to be noted that despite the advantages of applying GIS multi-criteria analysis as regarding the objectivity of results as well as time and cost effectiveness, it is a process that cannot be fully automated, especially in fields like urban planning, which is affected by multiple, and in several cases, contesting parameters. The automation of GIS analyses in such cases is an interesting direction for future research. This brings up the need of further investigating the quantification of qualitative parameters or descriptive stipulations so that they can be effectively used in GIS analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V. and A.I.; methodology, A.V., A.I. and D.K.; data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, A.V., A.I. and D.K.; supervision, E.B.; project administration, A.V. and D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not all data used are publicly available. Data availability is mentioned on text and references.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Public Law Restrictions (PLRs): Restrictions imposed by the State on individuals. |

| 2 | Transfer of Development Rights (TDR): TDR is a legal instrument that allows transferring development rights from a land parcel where restrictions are imposed (sending parcel) to another land parcel (receiving parcel). |

| 3 | Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF): Temporary instrument of the European Union’s (EU) plan to fund EU states to implement reforms and investments towards sustainability, resilience, and green and digital transitions. |

| 4 | Right Transfer Zones (RTZs): The zones where development rights deriving from sending parcels can be transferred. |

| 5 | Local Urban Plans (LUPs): Municipal unit level plans defining (among others) land uses, building terms, residential areas, delimitation of settlements, definition of protected areas, and measures to adapt to climate change. |

| 6 | Special Unit Plan (SUP): Urban planning tool with the same content as LUP, of supra-local/strategic importance. |

References

- Levy, J. An Overview. In Contemporary Urban Planning, 11th ed.; Levy, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Givord, G. Cadastre 3D des Restrictions de Droit Public à la Propriété Foncière. Master’s Thesis, Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers École Supérieure des Géomètres et Topographes, Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsakis, D.; Dimopoulou, E. Possibilities of Integrating Public Law Restrictions to 3D Cadastres. In Proceedings of the 5th International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop, Athens, Greece, 18–20 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A. Reconsidering the merit of market-oriented planning innovations: Critical insights on Transferable Development Rights from Coimbra, Portugal. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, E.; Falco, E.; Shabab, S.; Geneletti, D. Integrating ecosystem services in transfer of development rights: A literature review. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, G. Transferable Density in Connection with Zoning. In Technical Bulletin; Urban Land Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1961; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotou, T. Conservation of Biodiversity and Economic Development: The Concept of Transferable Development Rights. Environ. Resour. Econ. 1994, 4, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, V.; Kopits, E.; Walls, M. Using markets for land preservation: Results of a TDR program. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2006, 49, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaplowitz, M.; Machemer, P.; Pruetz, R. Planners’ experiences in managing growth using transferable development rights (TDR) in the United States. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, I. Between the transfer of development rights and the equivalency values: The case study of Natal, Brazil. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2017, 12, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumara, H.S.; Gopiprasad, S. Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) as an instruments for spatial planning implementation: Case of Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (BMA). In Proceedings of the 68th National Town and Country Planners Congress, Mumbai, India, 11–13 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yokohari, M.; Murayama, A.; Terada, T. The Value of Grey. In Framing in Sustainability Science Theoretical and Practical Approaches; Mino, T., Kudo, S., Eds.; SpringerOpen: Singapore, 2020; pp. 57–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghini, G.; Gemperle, F.; Seidl, I.; Axhausen, K.W. Results of an Agent-Based Market Simulation for Transferable Development Rights (TDR) in Switzerland. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2015, 42, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, E.; Chiodelli, F. The transfer of development rights in the midst of the economic crisis: Potential, innovation and limits in Italy. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, A.; Stocker, L.; Payne, M.; Middle, G.J. Enabling Managed Retreat from Coastal Hazard Areas through Property Acquisition and Transferable Development Rights: Insights from Western Australia. Urban Policy Res. 2020, 38, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billaud, O.; Soubeyrand, M.; Sandra, L.; Lenormand, M. Comprehensive decision-strategy space exploration for efficient territorial planning strategies. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 83, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhar, S.; Mousseau, V. Multicriteria Decision Making, Spatial. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Shekhar, S., Xiong, H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.; Sousa, N.; Coutinho-Rodrigues, J.; Natividade-Jesus, E. Benchmarking real and ideal cities—A multicriteria analysis of city performance based on urban form. Cities 2024, 150, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, N.; Cruz Salvador, L.C.; dos Santos, A.C.P.; Madero, Y.S. A proposal to compare urban infrastructure using multi-criteria analysis. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Asanza, S.; Quirow-Tortos, J.; Franco, J. Optimal site selection for photovoltaic power plants using a GIS-based multi-criteria decision making and spatial overlay with electric load. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S. Spatial multi-criteria decision making approach for wind farm site selection: A case study in Balıkesir, Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 192, 114158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhu, S.; Manan, Z.; Alwi, S.; Reba, M. Roles of geospatial technology in eco-industrial park site selection: State–of–the-art review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 309, 127361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, M.; Martínez-Graña, A.; Santos-Francés, F.; Veleda, S.; Zazo, C. Multi-Criteria Analyses of Urban Planning for City Expansion: A Case Study of Zamora, Spain. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law 880/1979; Government Gazette A. 58, 22.03.1979. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1979. (In Greek)

- Hellenic Republic. The Constitution of Greece. Available online: https://www.hellenicparliament.gr/UserFiles/f3c70a23-7696-49db-9148-f24dce6a27c8/THE%20CONSTITUTION%20OF%20GREECE.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Presidential Decree 470/1979; Government Gazette A. 138, 26.06.1979. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1979. (In Greek)

- Presidential Decree 510/1979; Government Gazette A. 154, 10.07.1979. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1979. (In Greek)

- Law 2300/1995; Government Gazette A. 69, 12.04.1995. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1995. (In Greek)

- Hellenic Council of the State. Hellenic Council of the State Decision 4573; Hellenic Council of the State: Athens, Greece, 1996. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Council of the State. Hellenic Council of the State Decision 4574; Hellenic Council of the State: Athens, Greece, 1996. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Council of the State. Hellenic Council of the State Decision 6070; Hellenic Council of the State: Athens, Greece, 1996. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Law 3044/2002; Government Gazette A. 197, 27.08.2002. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2002. (In Greek)

- Hellenic Council of the State. Hellenic Council of the State Decision 2366; Hellenic Council of the State: Athens, Greece, 2007. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Council of the State. Hellenic Council of the State Decision 2367; Hellenic Council of the State: Athens, Greece, 2007. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Council of the State. Hellenic Council of the State Decision 3274; Hellenic Council of the State: Athens, Greece, 2008. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Council of the State. Hellenic Council of the State Decision 3921; Hellenic Council of the State: Athens, Greece, 2010. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Law 4495/2017; Government Gazette A. 167, 03.11.2017. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2017. (In Greek)

- Ministerial Decision 72508/1890; Government Gazette B. 3544, 03.08.2021. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2021. (In Greek)

- Dean, M. A Practical Guide to Multi-Criteria Analysis; Technical Report; Bartlett School of Planning, University College London: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Communities and Local Government. Multi-Criteria Analysis: A Manual; Department for Communities and Local Government: London, UK, 2009; Available online: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/12761/1/Multi-criteria_Analysis.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Gamper, C.; Turcanu, C. On the governmental use of multi-criteria analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Analysis Function. An Introductory Guide to Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA). Available online: https://analysisfunction.civilservice.gov.uk/policy-store/an-introductory-guide-to-mcda/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Ministerial Decision 72343/1885; Government Gazette B. 3545, 03.08.2021. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2021. (In Greek)

- Vassi, A.; Siountri, K.; Papadaki, K.; Iliadi, A.; Ypsilanti, A.; Bakogiannis, E. Policy Reform through the Local Urban Plans (LUPs) and the Special Urban Plans (SUPs), Funded by Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). Land 2022, 11, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysanthakis, C. Commentary on the Hellenic Council of State Decision 2366/2007 on Transfer of Development Rights. Available online: https://nomosphysis.org.gr/11092/nomologia-2007ii/ (accessed on 1 February 2025). (In Greek).

- Varotsos, A. Transfer of Development Rights. In Proceedings of the PRODEXRO 2007 Conference, Athens, Greece, 23–24 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Digital Cartographical Data (DCD). Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/digital-cartographical-data (accessed on 15 January 2025). (In Greek).

- Law 3852/2010; Government Gazette A. 87, 07.06.2010. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2010. (In Greek)

- Law 4555/2018; Government Gazette A. 133, 19.07.2018. Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2018. (In Greek)

- ESTIA. Ministry of Environment and Energy. Available online: https://estia.minenv.gr/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Archaeological Cadastre. Directorate of the National Archive of Monuments. Available online: https://www.arxaiologikoktimatologio.gov.gr/en/content/about-archaeological-cadastre (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Public Sector Open Data Registry. GIS Athens Metro Operating. Available online: http://beta.data.gov.gr/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).