Analysis of the Impact of Ownership Type on Construction Land Prices Under the Influence of Government Decision-Making Behaviors in China: Empirical Research Based on Micro-Level Land Transaction Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

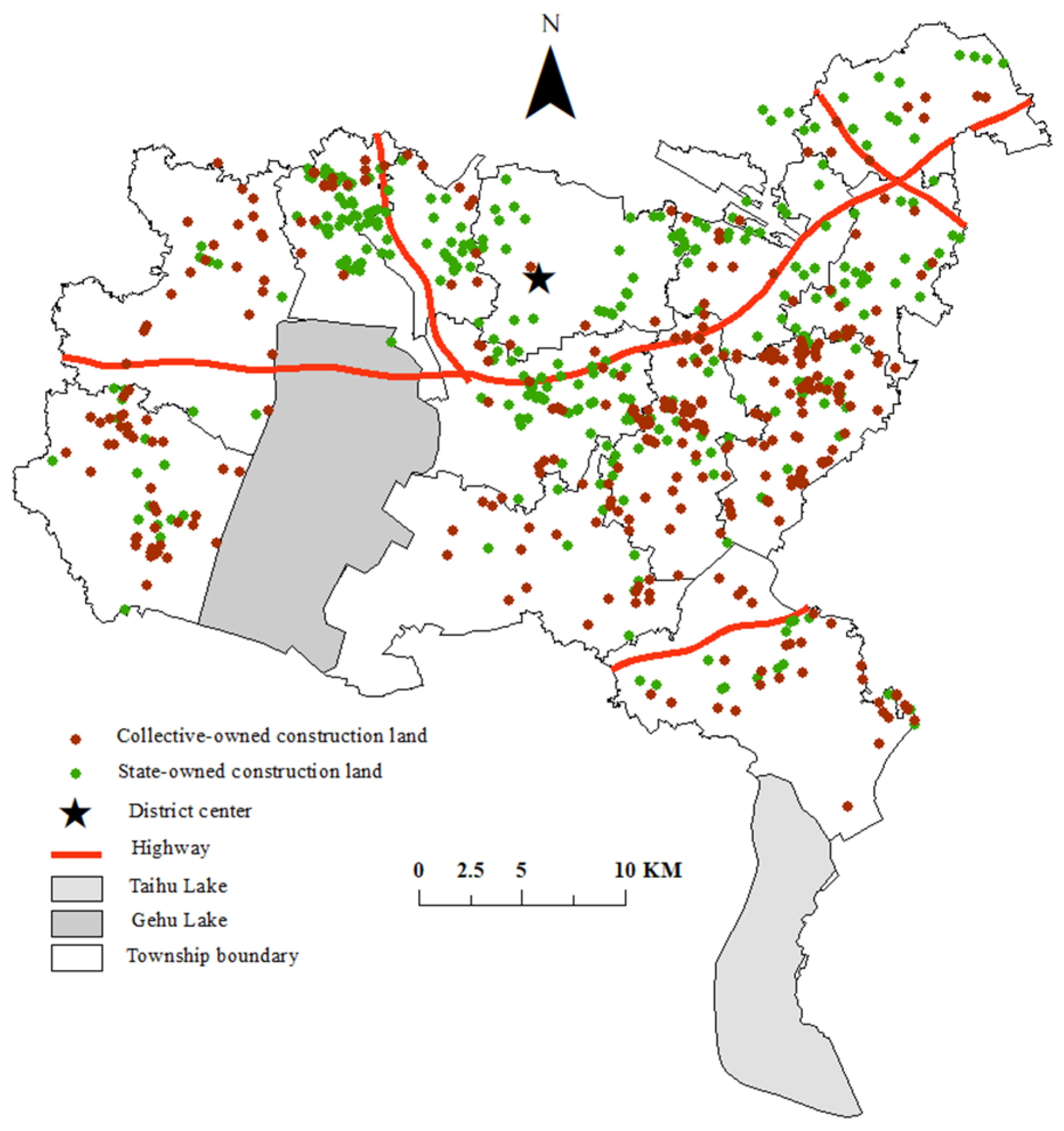

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Model Construction

2.4.1. Hedonic Price Model

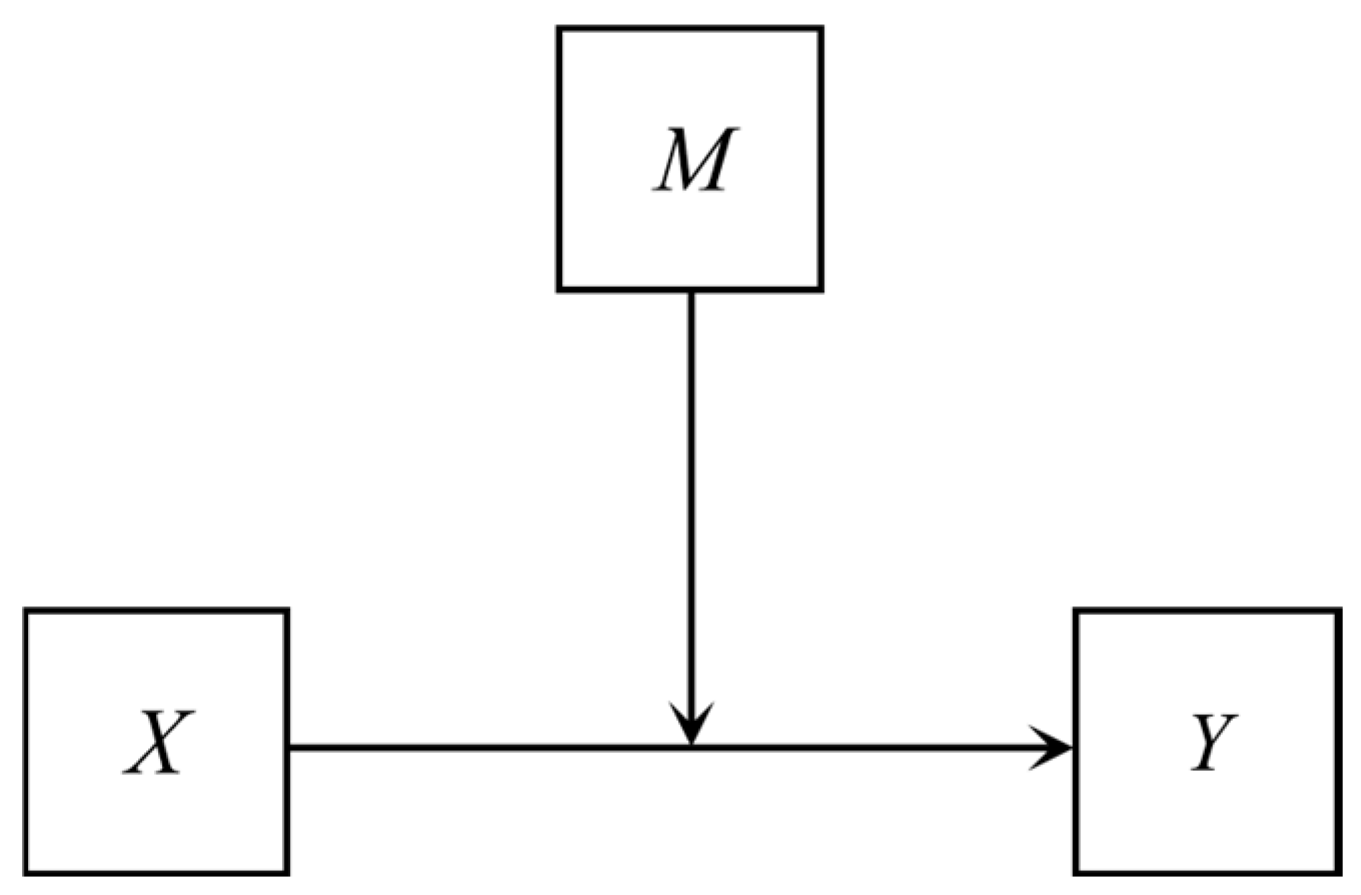

2.4.2. Moderating Effect Model

- (1)

- The main effect (the regression coefficient of the explanatory variable when the interaction term is not introduced) is positive and the coefficient of the interaction term is positive, indicating that the moderator variable M has a positive moderating effect. This means that M strengthens the positive impact of X on Y, i.e., when M has a high value, it enhances the positive impact.

- (2)

- The main effect is positive and the coefficient of the interaction term is negative, indicating that the moderator variable M has a negative moderating effect. This means that M weakens the positive impact of X on Y, i.e., when M has a high value, it reduces the positive impact.

- (3)

- The main effect is negative and the coefficient of the interaction term is positive, indicating that the moderator variable M has a positive moderating effect. This means that M weakens the negative impact of X on Y, i.e., when M has a high value, it reduces the negative impact.

- (4)

- The main effect is negative and the coefficient of the interaction term is negative, indicating that the moderator variable M has a negative moderating effect. This means that M strengthens the negative impact of X on Y, i.e., when M has a high value, it enhances the negative impact.

2.5. Variable Selection and Descriptive Statistics

2.5.1. Variable Selection

- (1)

- Explained variable

- (2)

- Core explanatory variable

- (3)

- Moderator variables

- (4)

- Control variables

2.5.2. Descriptive Statistics of Main Variables

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Ownership Type on Construction Land Prices

3.2. Moderating Effect of Spatial Planning on the Impact of Ownership Type on Construction Land Prices

3.3. Moderating Effect of Supply Plan on the Impact of Ownership Type on Construction Land Prices

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Zhang, X.L.; Wang, H.Z.; Skitmore, M. The right-of-use transfer mechanism of collective construction land in new urban districts in China: The case of Zhoushan City. Habitat Int. 2017, 61, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.H.; Liu, Y.S. Rural land system reforms in China: History, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.J. Establishment of the integrated urban-rural construction land market system. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.M. The scientific connotation and realization of “equal rights and equal prices” between collective and state-owned land. Issues Agric. Econ. 2017, 38, 12–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dunford, R.W.; Marti, C.E.; Mittelhammer, R.C. A Case Study of Rural Land Prices at the Urban Fringe Including Subjective Buyer Expectations. Land Econ. 1985, 61, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Sun, L. The impacts of floor area ratio and transfer modes on land prices: Based on hedonic price model. China Land Sci. 2010, 24, 70–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.H.; Du, X.J. Holding the market under the stimulus plan: Local government financing vehicle’s land purchasing behavior in China. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 50, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploegmakers, H.; de Vor, F. Determinants of industrial land prices in The Netherlands: A behavioural approach. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2015, 8, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M.; Hansen, D.J.; Mcintosh, W.; Slade, B.A. Urban land: Price indices, performance, and leading indicators. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2020, 60, 396–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Li, C.X.; Fang, Y.H. Driving factors of the industrial land based on a geographically weighted regression model: Evidence from a rural land system reform pilot in China. Land 2020, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Wei, Y.D.; Xiao, W. Land marketization, fiscal decentralization, and the dynamics of urban land prices in transitional China. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, H. Local economic structure, regional competition, and the formation of industrial land price in China: Combining evidence from process tracing with quantitative results. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.F.; Huang, X.J.; Yang, H.; Chen, Z.G.; Zhong, T.Y.; Xie, Z.L. Effects of dual land ownerships and different land lease terms on industrial land use efficiency in Wuxi City, East China. Habitat Int. 2018, 78, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.H.; Du, X.J. Does the marketization of collective-owned construction land affect the integrated urban-rural construction land market? An empirical research based on micro-level land transaction data in Deqing County, Zhejiang Province. China Land Sci. 2020, 4, 18–26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.L.; Yu, Y.Y.; Hong, J.G. Property rights transfer, value realization and revenue sharing of rural residential land withdrawal: An analysis based on field surveys in Jinzhai and Yujiang. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2022, 4, 42–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kheir, N.; Portnov, B.A. Economic, demographic and environmental factors affecting urban land prices in the Arab sector in Israel. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, F.; Ge, J.W.; Liu, D.X.; Zhong, Q. Determinants of industrial land price in the process of land marketization reform in China. China Land Sci. 2017, 31, 33–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tu, F.; Zou, S.L.; Ding, R. How do land use regulations influence industrial land prices? Evidence from China. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2020, 25, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.G.; Chen, Y.Y.; Li, Y.W. Between the ownership and the right to use: The possession of land and its realization. China Econ. Q. 2022, 22, 2107–2124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, R.L. Views on the coordination between urban planning and land use planning. Econ. Geogr. 2001, 5, 605–608. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.Y. Reform of comprehensive land use planning. China Land Sci. 2004, 4, 13–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.L. Difficult position and theoretical error of collective business construction land market with the dimension of “same rights for same land”. Acad. Mon. 2020, 52, 118–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.P.; Feng, Y.Q.; Yu, S.Q. On optimization of land income distribution in transaction of rural commercial collective-owned construction land: A case study of the reform pilot in Beiliu City. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2021, 21, 116–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- CMBS (Changzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics). Changzhou Statistical Yearbook. China Statistics Press (in Chinese). 2019. Available online: https://tjj.changzhou.gov.cn/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- NBS (National Bureau of Statistics). China Statistical Yearbook. China Statistics Press (in Chinese). 2019. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- CAS (Chinese Academy of Sciences). Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, 2019. EB/OL. Available online: http://www.resdc.cn/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- CMBNRP (Changzhou Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning). Changzhou City Urban Master Plan (2011–2020). 2019. Available online: http://zrzy.jiangsu.gov.cn/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Dong, G.P.; Zhang, W.Z.; Wu, W.J.; Guo, T.Y. Spatial heterogeneity in determinants of residential land price: Simulation and prediction. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2011, 66, 750–760. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, S. Hedonic prices and implicit markets: Product differentiation in pure competition. J. Political Econ. 1974, 82, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.W.; Chin, T.L. A critical review of literature on the hedonic price model. Int. J. Hous. Sci. Its Appl. 2002, 27, 145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, L.; Odening, M.; Ritter, M. Do non-farmers pay more for land than farmers? Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2024, 51, 1094–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Hou, J.T.; Zhang, L. A comparison of moderator and mediator and their applications. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2005, 2, 268–274. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.J.; Yang, S.J.; Qi, M.N.; Zhang, A.L. How does China’s rural collective commercialized land market run? New evidence from 26 pilot areas, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 136, 106969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | Land price | Y | Total transfer price of land/Plot area (1000 CNY/m2) |

| Core explanatory variable | Ownership type | E | “1” indicates that the plot is collective-owned, “0” indicates state-owned |

| Moderator variables | Spatial planning | M1 | “1” indicates the plot is within the boundary of downtown areas, “0” indicates outside |

| Supply plan | M2 | Proportion of collective-owned land in the annual total land supply (%) | |

| Plot attributes | Area | X1 | Plot area of land (m2) |

| Term | X2 | Transfer term of land-use right (years) | |

| Time | X3 | Year of land transfer (year) | |

| Location attributes | Distance to district center | X4 | Distance from the plot to the district administrative center (km) |

| Distance to township or sub-district center | X5 | Distance from the plot to the nearest township or sub-district administrative center (km) | |

| Distance to highway exit | X6 | Distance from the plot to the nearest highway exit (km) | |

| Distance to major roads | X7 | Distance from the plot to the nearest major road (urban expressway and national, provincial, and county highways) (km) | |

| Distance to train station | X8 | Distance from the plot to the nearest train station (km) | |

| Distance to school | X9 | Distance from the plot to the nearest primary or secondary school (km) | |

| Number of schools | X10 | Number of primary and secondary schools within a 2 km radius of the plot | |

| Distance to park | X11 | Distance from the plot to the nearest park (km) | |

| Distance to water source | X12 | Distance from the plot to the nearest water source (rivers and lakes) (km) | |

| Neighborhood attributes | Population density | X13 | Population density of the township or sub-district where the plot is located (1000 person/km2) |

| GDP density | X14 | Total GDP within a 1 km grid (billion CNY/km2) |

| Variable | Collective-Owned Construction Land | State-Owned Construction Land | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | Mean | STD | Observation | Mean | STD | |

| Y | 1426 | 0.371 | 0.276 | 249 | 0.759 | 1.190 |

| E | 1426 | 1 | 249 | |||

| X1 | 1426 | 7202.004 | 15,956.008 | 249 | 25,086.013 | 34,601.351 |

| X2 | 1426 | 49.804 | 1.705 | 249 | 48.394 | 4.703 |

| X3 | 1426 | 2018.227 | 0.551 | 249 | 2018.920 | 1.345 |

| X4 | 1426 | 16.525 | 5.166 | 249 | 11.763 | 6.054 |

| X5 | 1426 | 3.461 | 1.929 | 249 | 3.755 | 1.850 |

| X6 | 1426 | 7.426 | 2.857 | 249 | 4.521 | 2.720 |

| X7 | 1426 | 0.896 | 0.702 | 249 | 0.687 | 0.592 |

| X8 | 1426 | 11.424 | 8.032 | 249 | 16.486 | 8.285 |

| X9 | 1426 | 1.246 | 0.627 | 249 | 1.372 | 0.656 |

| X10 | 1426 | 2.979 | 2.242 | 249 | 3.177 | 3.955 |

| X11 | 1426 | 6.958 | 4.992 | 249 | 6.805 | 3.505 |

| X12 | 1426 | 4.248 | 2.566 | 249 | 4.404 | 2.700 |

| X13 | 1426 | 1.430 | 0.720 | 249 | 2.090 | 1.350 |

| X14 | 1426 | 0.224 | 0.050 | 249 | 0.286 | 0.091 |

| Variables | lnY | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | STD | ||

| Main | E | −0.228 *** | 0.033 |

| lnX1 | 0.018 ** | 0.009 | |

| lnX2 | −2.116 *** | 0.157 | |

| X3 | 0.014 | 0.013 | |

| lnX4 | 0.126 | 0.184 | |

| lnX5 | 0.023 | 0.056 | |

| lnX6 | 0.092 | 0.076 | |

| lnX7 | −0.037 *** | 0.011 | |

| lnX8 | 0.022 | 0.095 | |

| lnX9 | −0.122 *** | 0.029 | |

| X10 | 0.003 | 0.008 | |

| lnX11 | 0.058 | 0.082 | |

| lnX12 | −0.009 | 0.025 | |

| lnX13 | −0.136 * | 0.072 | |

| lnX14 | −0.028 | 0.080 | |

| Wx | lnY | 0.503 *** | 0.045 |

| E | 0.203 *** | 0.072 | |

| lnX1 | 0.088 *** | 0.025 | |

| lnX2 | 0.250 | 0.408 | |

| X3 | −0.045 | 0.034 | |

| lnX4 | −0.157 | 0.193 | |

| lnX5 | −0.023 | 0.063 | |

| lnX6 | −0.106 | 0.084 | |

| lnX7 | 0.041 ** | 0.016 | |

| lnX8 | −0.003 | 0.101 | |

| lnX9 | 0.181 *** | 0.043 | |

| X10 | 0.005 | 0.011 | |

| lnX11 | −0.044 | 0.085 | |

| lnX12 | −0.007 | 0.030 | |

| lnX13 | 0.122 | 0.086 | |

| lnX14 | 0.051 | 0.108 | |

| R2 | 0.392 | ||

| Log LIK | −678.722 | ||

| AIC | 1421.440 | ||

| SC | 1595.000 | ||

| Observation | 1675 | ||

| Variables | lnY | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | STD | ||

| Main | E × M1 | −0.241 *** | 0.066 |

| E | −0.136 *** | 0.041 | |

| M1 | 0.225 ** | 0.100 | |

| lnX1 | 0.017 ** | 0.009 | |

| lnX2 | −2.141 *** | 0.157 | |

| X3 | 0.012 | 0.013 | |

| lnX4 | 0.128 | 0.183 | |

| lnX5 | 0.013 | 0.055 | |

| lnX6 | 0.093 | 0.075 | |

| lnX7 | −0.043 *** | 0.011 | |

| lnX8 | 0.021 | 0.094 | |

| lnX9 | −0.122 *** | 0.030 | |

| X10 | 0.000 | 0.008 | |

| lnX11 | 0.040 | 0.081 | |

| lnX12 | −0.012 | 0.025 | |

| lnX13 | −0.141 ** | 0.071 | |

| lnX14 | −0.047 | 0.080 | |

| Wx | lnY | 0.504 *** | 0.045 |

| E × M1 | 0.184 * | 0.111 | |

| E | 0.152 * | 0.089 | |

| M1 | −0.212 | 0.129 | |

| lnX1 | 0.096 *** | 0.026 | |

| lnX2 | 0.167 | 0.413 | |

| X3 | −0.043 | 0.035 | |

| lnX4 | −0.164 | 0.194 | |

| lnX5 | −0.011 | 0.063 | |

| lnX6 | −0.110 | 0.083 | |

| lnX7 | 0.047 *** | 0.016 | |

| lnX8 | −0.005 | 0.101 | |

| lnX9 | 0.181 *** | 0.044 | |

| X10 | 0.007 | 0.011 | |

| lnX11 | −0.021 | 0.085 | |

| lnX12 | 0.000 | 0.030 | |

| lnX13 | 0.132 | 0.086 | |

| lnX14 | 0.076 | 0.109 | |

| R2 | 0.397 | ||

| Log LIK | −671.653 | ||

| AIC | 1415.310 | ||

| SC | 1610.550 | ||

| Observation | 1675 | ||

| Variables | lnY | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | STD | ||

| Main | E × M2 | −0.689 ** | 0.309 |

| E | 0.602 *** | 0.185 | |

| M2 | 0.379 | 0.274 | |

| lnX1 | 0.087 *** | 0.024 | |

| lnX2 | −0.115 | 0.410 | |

| X3 | −0.070 * | 0.042 | |

| lnX4 | −0.094 | 0.189 | |

| lnX5 | −0.023 | 0.061 | |

| lnX6 | −0.111 | 0.082 | |

| lnX7 | 0.043 *** | 0.016 | |

| lnX8 | −0.012 | 0.098 | |

| lnX9 | 0.181 *** | 0.043 | |

| X10 | 0.008 | 0.011 | |

| lnX11 | −0.037 | 0.083 | |

| lnX12 | −0.008 | 0.030 | |

| lnX13 | 0.100 | 0.084 | |

| lnX14 | −0.019 | 0.106 | |

| Wx | lnY | 0.437 *** | 0.049 |

| E × M2 | −0.730 *** | 0.107 | |

| E | 0.245 *** | 0.067 | |

| M2 | 0.061 | 0.094 | |

| lnX1 | 0.012 | 0.009 | |

| lnX2 | −2.056 *** | 0.154 | |

| X3 | −0.046 *** | 0.016 | |

| lnX4 | 0.048 | 0.181 | |

| lnX5 | 0.032 | 0.054 | |

| lnX6 | 0.101 | 0.074 | |

| lnX7 | −0.037 *** | 0.011 | |

| lnX8 | 0.020 | 0.092 | |

| lnX9 | −0.110 *** | 0.029 | |

| X10 | 0.003 | 0.008 | |

| lnX11 | 0.055 | 0.080 | |

| lnX12 | −0.005 | 0.025 | |

| lnX13 | −0.118 * | 0.070 | |

| lnX14 | −0.002 | 0.078 | |

| R2 | 0.442 | ||

| Log LIK | −290.285 | ||

| AIC | 652.570 | ||

| SC | 842.025 | ||

| Observation | 1426 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duan, J.; Ma, Z.; Dong, F.; Zhou, X. Analysis of the Impact of Ownership Type on Construction Land Prices Under the Influence of Government Decision-Making Behaviors in China: Empirical Research Based on Micro-Level Land Transaction Data. Land 2025, 14, 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051070

Duan J, Ma Z, Dong F, Zhou X. Analysis of the Impact of Ownership Type on Construction Land Prices Under the Influence of Government Decision-Making Behaviors in China: Empirical Research Based on Micro-Level Land Transaction Data. Land. 2025; 14(5):1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051070

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Jinlong, Zizhou Ma, Fan Dong, and Xiaoping Zhou. 2025. "Analysis of the Impact of Ownership Type on Construction Land Prices Under the Influence of Government Decision-Making Behaviors in China: Empirical Research Based on Micro-Level Land Transaction Data" Land 14, no. 5: 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051070

APA StyleDuan, J., Ma, Z., Dong, F., & Zhou, X. (2025). Analysis of the Impact of Ownership Type on Construction Land Prices Under the Influence of Government Decision-Making Behaviors in China: Empirical Research Based on Micro-Level Land Transaction Data. Land, 14(5), 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051070