Effect of Forced Eviction and Land Grabs on Household Economic Capital Security of Displaced Pre-Urban Farmers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Is there a significant difference between the economic capital security of evicted and non-evicted preurban households?

- Is urban expansion-induced eviction significantly and negatively affecting the economic capital security of peri-urban farming households?

2. Materials and Methods

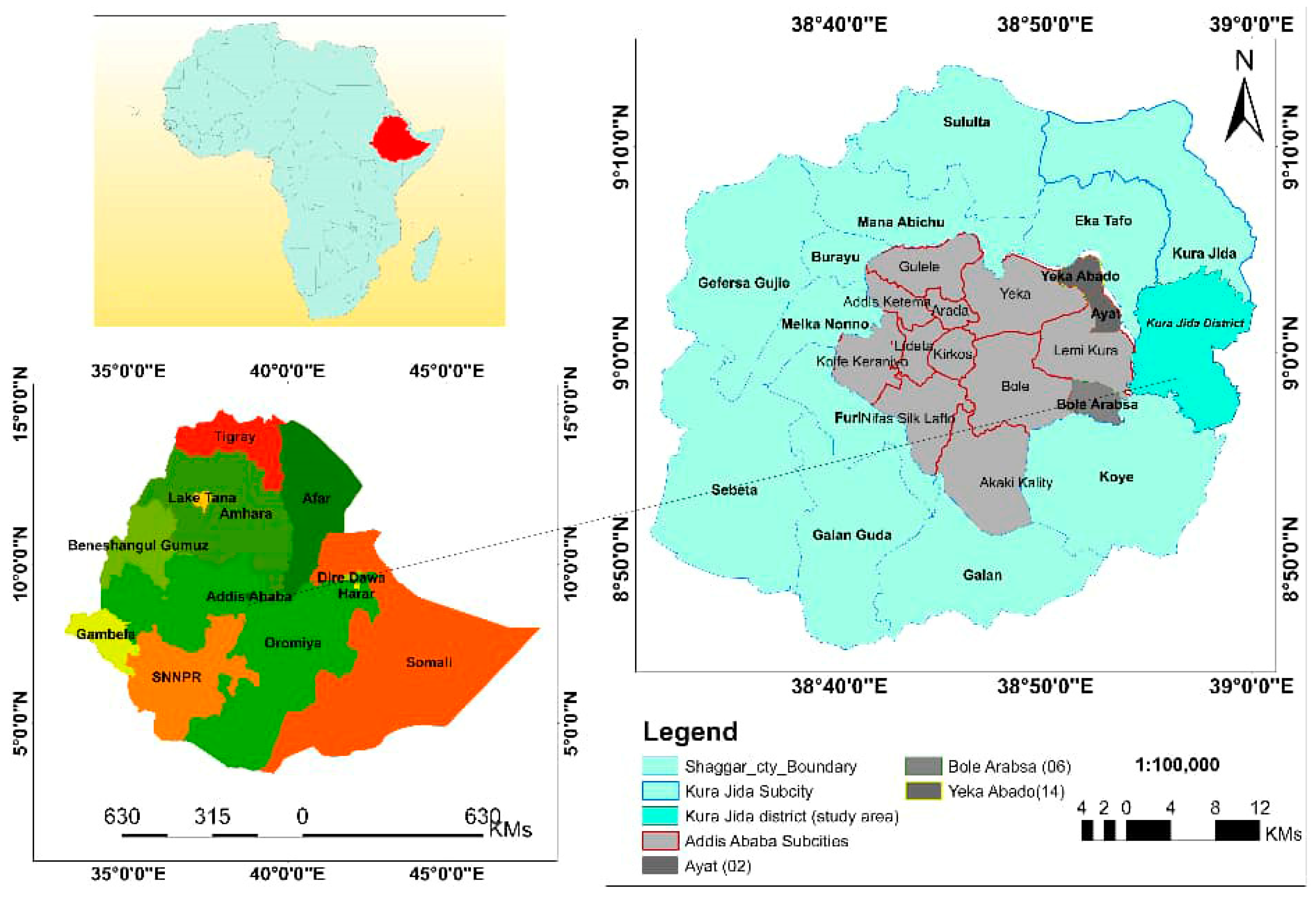

2.1. The Study Area

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Model Specification for Data Analysis

2.4.1. Economic Capital Security Index (ECSI)

2.4.2. Binary Logistic Regression

3. Results

3.1. Expropriated Land Size

3.2. Impact of Eviction on Economic Capital Security (ECS)

3.2.1. Comparison of ECS of Evicted and Non-Evicted Preurban Farming Households

- Income from agricultural sales: Evicted households scored 0.7399 compared to 5 for non-evicted households. The stark difference indicates that non-evicted households have a significantly higher income from agricultural sales, suggesting better access to land and markets.

- Income from livestock sales: The evicted households scored 0.6637 against 3.3722 for the non-evicted households. This gap reflects the challenges facing evicted households in maintaining livestock and accessing markets for animal products.

- Income from Employment and Daily Wages: Interestingly, evicted households have a higher weighted score of 0.7534 compared to 0.5247 for non-evicted households. This suggests that evicted households may rely more on casual labour as an income source, possibly due to limited access to stable employment opportunities and lack of access to agricultural land.

- Income from business activities: Non-evicted households scored 0.4843, significantly higher than 0.2152 for evicted households. This disparity implies that non-evicted households have better opportunities to engage in business activities, which contributes to their economic stability. Non-evicted households participate in small businesses, such as small ruminant trades, grain, pottery, livestock manure, and commission work in their communities. However, such opportunities are rarely available in displaced preurban communities.

- Income from semi-skilled work: The non-evicted households scored 1.0628 compared to 0.2287 for the evicted households. This indicates that non-evicted households have more access to semiskilled work opportunities, enhancing their economic capital. Non-evicted households engage in making pottery, which generates additional income for the family. Access to raw materials for pottery making in pre-urban communities contributes to participation in pottery making.

- Remittances and pension income: Remittances provide a slightly higher contribution to the economic capital of evicted households (0.1794) than those of non-evicted households (0.1166). Both groups receive negligible pension income, indicating a limited role in economic security.

- Income from Renting and Distress Selling Assets: Evicted households make significant income from renting assets (1.7892) compared to non-evicted households (0.0538). Evicted households generate additional income from renting their extra rooms from their service quarters due to their proximity to the urbanised centres. On the contrary, both groups have minimal income from distress selling assets, with evicted households scoring slightly higher at 0.1614 than non-evicted households at 0.0538.

- Aid and loans: Evicted households receive more aid (0.9776) compared to non-evicted households (0.0179), reflecting their higher dependency on external support. This is because evicted households receive monthly ETB 2200 safety net support from the Addis Ababa city administration. Loan access remains limited for both groups, though slightly higher for non-evicted households.

- Current Financial Resources: Both groups have similar scores for cash on hand and savings, indicating comparable short-term financial resources.

- Participation in Income-Generating Schemes: Non-evicted households have a slightly higher score (1.3991) compared to evicted households (1.2780), suggesting better participation in various income-generating activities.

3.2.2. Impact of Eviction on HECS of Displaced Pre-Urban Households

3.2.3. Results of the Qualitative Analysis

- i.

- Loss of livelihoods and economic challenges:

- ii.

- Challenges in Transitioning to Non-Agricultural Livelihoods:

- iii.

- Inadequate Compensation and Resettlement:

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

- Compensation in the form of shareholding: To address the lost intergenerational resources of displaced farmers, policymakers should compensate them with in-kind shareholding from private investments, real estate, and government housing projects through public-private partnerships.

- Land Restitution and Compensation: Prioritise fair and equitable land restitution and compensation schemes for evicted households, allowing them to rebuild their agricultural livelihoods.

- Skills Development and Employment Programmes: Provide targeted skills development and employment programmes to equip evicted households with the skills necessary to transition to alternative income-generating activities.

- Microfinance and Access to Credit: Facilitate access to microfinance and credit services to support the development of small businesses and entrepreneurs.

- Social safety nets and cash transfer programmes: Strengthen social safety nets and implement targeted cash transfer programmes to provide immediate relief and prevent further asset depletion.

- Participatory Planning and Community Engagement: Engage affected communities in participatory planning processes to ensure that development initiatives are aligned with their needs and priorities.

- i.

- Capturing Dynamic Changes: Urban expansion is an ongoing process that unfolds over time. A longitudinal study would allow the researcher to capture the dynamic nature of these changes and their evolving impacts on Peri-urban communities. It enables the observation of gradual shifts in livelihood strategies, land use patterns, and socioeconomic conditions as urban areas invade peri-urban spaces.

- ii.

- Long-term Impact Assessment: The effects of urban expansion on livelihoods are gradual but develop over extended periods. A longitudinal approach would allow one to assess both short- and long-term impacts. It would help to understand how communities adapt to changes over time and the sustainability of these adaptations.

- iii.

- Policy Evaluation: Longitudinal data can provide valuable information on the effectiveness of policies and interventions to manage urban expansion and support periurban livelihoods. It allows for evaluating policy outcomes over time, helping to identify successful strategies and areas needing improvement.

- iv.

- Tracking Socio-economic Trajectories: By following the same communities over time, the researcher can track individual and household socioeconomic trajectories, providing a nuanced understanding of who benefits or loses from urban expansion.

- v.

- Identifying Tipping Points: A longitudinal study can help identify critical tipping points or thresholds at which urban expansion begins to impact peri-urban livelihoods, significantly informing proactive policy measures.

- vi.

- Understanding Adaptation Strategies Over time, communities develop various strategies to adapt to changing circumstances. A longitudinal study would allow observation and analysis of these evolving adaptation strategies.

- vii.

- Informing Sustainable Urban Planning: Long-term data on the impacts of urban expansion can inform more sustainable and inclusive urban planning strategies that consider the needs of Peri-urban communities.

- viii.

- Capturing Intergenerational Effects: A longitudinal study can reveal how urban expansion impacts different generations within urban Peri communities, providing information on issues of intergenerational equity.

- ix.

- Understanding Resilience Observing communities over time allows the researcher to gain insight into factors that contribute to community resilience and urban expansion pressures.

- x.

- Contextualising Rapid Changes Addis Ababa is one of the fastest-growing cities in Africa. A longitudinal study can contextualise this rapid growth and its implications for surrounding areas.

- xi.

- Comparative analysis: Long-term data would allow for a comparative analysis with other rapidly expanding urban areas, contributing to broader theories of periurban development.

- xii.

- Methodological Rigour: Longitudinal studies provide more substantial evidence for causal relationships between urban expansion and change in livelihood, improving the reliability of the findings.

- xiii.

- Informing Future Scenarios: Long-term data can inform predictive models and future scenarios, helping policymakers and planners anticipate and prepare for future challenges.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yasin, K.H.; Iguala, A.D.; Gelete, T.B. Spatiotemporal analysis of urban expansion and its impact on farmlands in the central Ethiopia metropolitan area. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, T.; Assefa, E.; Zeleke, T. Urban expansion-induced changes in land use and its effect on ecosystem services in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1454556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayenachew, Y.A.; Abebe, B.G. The dynamics of urbanization, land use land cover changes, and land expropriation in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1439954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, C.; Teklemariam, D.; Addis, E. Effect of Drivers of Urban Expansion on Food Security in Moderating Role of Governance Response. Int. J. Manag. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 10, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnamura, K.; Antwi, M.A.; Abenet, B. The impact of urban expansion on peri-urban farmers in Addis Ababa. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2024, 74, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, B.; Baye, F. The impact of land expropriation on changing livelihoods: The case of displaced peri-urban farmers in Kon and Gashena towns, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchelo, R.; Bishop, T.F.A.; Ugbaje, S.U.; Akpa, S. Patterns of Urban Sprawl and Agricultural Land Loss in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Cases of the Ugandan Cities of Kampala and Mbarara. Land 2024, 13, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Shakeel, A.; Ahmad, S.; Kaur, N. Exploring the Linkages Between Land Degradation and Food Insecurity. Asia-Pac. J. Rural. Dev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamura, K. Exploring the Consequences of Land Expropriation on the Food Security of Peri-urban Indigenous Communities in Addis Ababa. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G. Conservation and Indigenous peoples’ struggle for livelihoods: Suba Park (Ethiopia). Environ. Conserv. 2023, 50, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberra, D. Addis Ababa master development plan: A program for development or for ethnic cleansing? Вестник Рoссийскoгo университета дружбы нарoдoв. Серия: Сoциoлoгия 2019, 19, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debelo, A.R.; Soboka, T.E. Urban Development and the Making of Frontiers in/from Addis Ababa/Finfinne, Ethiopia. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2022, 58, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayessa, B.S. They deceived us: Narratives of Addis Ababa development-induced displaced peasants. Int. J. Sociol. Anthropol. 2020, 12, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnakew, M.B.; Amogne, M.K.; Abebe, K.T.; Gebru, M.A. Land rights, bases of informal settlements and bogus contract documents as a means of urban fringe legal land transactions in Ethiopia. Cities 2024, 149, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demisse, M. Urban land use, land cover change and urban microclimate dynamics in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Discov. Environ. 2024, 2, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, T.O.; Oyebamiji, V.O.; Sanni, D.O.; Akinwale, E.O.; Akinluyi, F.O. Environmental impacts of urban growth and land use changes in tropical cities. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 6, 1481932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Urban Sprawling and Agriculture: A Review of Issues. Indian J. Econ. Dev. 2024, 20, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolamo, Z.M.; Kitila, A.W.; Beza, S.A. Urban expansion and its impacts on the livelihood of peripheral farming households: The case of Shinshicho town, Ethiopia. Int. Plan. Stud. 2024, 29, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnianto, B.T. Urban Agriculture: A Solution to Land Constraints Amidst Urbanization. West Sci. Nat. Technol. 2024, 2, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeda, B.S.; Cirella, G.T.; Abebe, B.G.; Gemeda, F.T. Unveiling and speculators in Addis Ababa: Insights, recommendations, and economic implications for sustainable development. Eco Cities 2024, 4, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayenachew, Y.A.; Abebe, B.G. Navigating urbanization implications: Effects of land expropriation on Farmers’ Livestock in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Front. Sustain. Cities 2024, 6, 1385309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklemariam, A.T.; Cochrane, L. The Rush to the Peripheries: Land Rights and Tenure Security in Peri-Urban Ethiopia. Land 2021, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.G.; Agegnehu, A.W.; Dessie, B.T.; Minale, A.S. Responsible Governance of Land Tenure in the context of Investment from Theory to Practice: Lessons from Ethiopia. Res. Glob. 2023, 6, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabala, A.M. Large-scale land acquisition and human rights at the crossroads: Quest for a rights-based approach to land administration in Ethiopia. J. Sustain. Dev. Law Policy 2020, 10, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, I.Z.; Abubakar, U.; Muhammad, A.; Ahmad, K.H. Sample size calculation in biomedical, clinical, and biological sciences research. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2025, 11, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangappa, D.; Rafi, K.; Candhini, E.; Charishma, G. Livelihood Security Index Assessment among Millet Farmers in Northeastern Hill (NEH) States of India. Int. J. Bio-Resour. Stress Manag. 2024, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, M.S.; Nanaware, D.R.; Ghagare, T.N. Measuring Regional Dimensions of Sustainable Livelihood Security Index in Maharashtra. Preprint 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Jatav, S.S. Are livelihoods of slum dwellers sustainable and secure in developing economies? Evidence from Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh in India. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeraladinni, D.; Patil, B.L. Agricultural sustainability in Karnataka: Application of Sustainable Livelihood Security Index. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 93, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdushamad, A.; Salam, M.; Tenriawaru, A.N.; Jamil, M.H.; Rukmana, D.; Hamid, N.; Kamarulzaman, N.H.; Rahmadanih, R.; Heliawaty, H.; Busthanul, N.; et al. The Application of the Binary Logistic Regression Model in Examining the Effects of Input Factor Allocation on Tangerine Production: Empirical Evidence from Selayar Islands Regency, Indonesia. Preprints 2024, 2024091689. [Google Scholar]

- Sihombing, E.D.; Novianti, P.; Wahyuliani, I. Binary Logistic Regression Modeling on Household Poverty Status in Bengkulu Province. Pattimura Proceeding Conf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 5, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethan, N.K.F.; Luan, F.; Obe, L. Binary Logistic Regression Analysis in Determining Risk Factors of Acute Respiratory Infection (IRA) on Under-Five Children. Sainmatika 2024, 21, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, D.; Romaguera-de-la-Cruz, M. Measuring economic insecurity by combining income and wealth: An extended well-being approach. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2025, 23, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiraszka, P.; Karpińska, U. Economic security as an element of the region’s development process on the example of communes of the świętokrzyskie voivodship. Balt. J. Econ. Stud. 2020, 6, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikpeyma, N.; Maroufizadeh, S.; Esmaeili, M. The importance of reporting the effect size in quantitative studies. Nurs. Pract. Today 2021, 8, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares-Neto, J. Effect size: A statistical basis for clinical practice. Rev. Odonto Ciência 2018, 33, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, J.E.; Mader, N.S.; Tannenbaum, D.I.; van Dijk, W. Does Eviction Cause Poverty? Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Cook County, IL; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T.F. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. J. Am. Hist. 2017, 104, 820–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.A.; Ikram, K.; Hussain, M.; Lak, T. Forced Displacement, Socio-Economic Impacts and Misplaced Identity of Villagers: A Qualitative Exploration of Three Villages in Lahore. Deleted J. 2024, 13, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygün, S.; Akdemir, M.; Duran, C. Bibliometric Analysis of Refugee Effects to Economic Development. Anadolu Üniversitesi Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2024, 24, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, E.; Patiño, J.E.; Duque, J.C.; Keith, M. The urban footprint of rural forced displacement. Comput. Urban Sci. 2024, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, S.E.; Yaseen, M.; Ali, S.; Visetnoi, S. Agricultural Land Conversion and Challenges for Tenant Farmers: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 36, 802–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeven, K.; Milimu, W.S. Examining How Land Eviction Affects Social Cohesion in an Integrated Community: A Case of Maela Integrated Community, Naivasha, Nakuru County. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2025, XI, 1008–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, V.; Matilla-Santander, N.; Kreshpaj, B.; Vignola, E.; Wegman, D.H.; Hogstedt, C.; Bodin, T.; Ahonen, E.Q.; Baron, S.; Muntaner, C.; et al. A Systematic Review of Evaluated Labor Market Initiatives Addressing Precarious Employment: Findings and Public Health Implications. Int. J. Soc. Determ. Health Health Serv. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, N. Socioeconomic Vulnerabilities of Migrant Labour Households in Delhi. Indian Public Policy Rev. 2024, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, I.; von Peter, G. Distress selling and asset market feedback. Financ. Mark. Inst. Instrum. 2007, 16, 243–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, R.; Masset, E. Land markets, risk, and distress sales in Nicaragua: The impact of income shocks on rural differentiation. J. Agrar. Change 2003, 3, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmakki, O. From Relief to Resilience: The Dual Role of Humanitarian Assistance in Alleviating Poverty and Fostering Sustainable Development. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2025, VIII, 1952–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyitunga, E.B.; Musya, J.K. Dependency syndrome within Africa’s international relations: A hindrance to sustainable development in Africa. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 7052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamneh, A.S.; Workie, G.F.; Moges, N.B. The political-economy of land acquisition and privatization of Birr and Ayehu Farms in Amhara Region, North-West Ethiopia. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutapea, M. Implementation of Compensation of Rights of Ownership on Land in the Development of Toll Road in Dumai City, Riau Province. West Sci. Law Hum. Rights 2024, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanga, L.; Mooya, M.M. Compensation assessment practices in expropriation of customary land: Evidence from Malawi. Land Use Policy 2023, 134, 106931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusti, I.; Kade, A.; Adhisukmawati, H.; Ketut, G.A.; Handayani, R.; Karjoko, L. Fairness Aspects of Compensation Arrangements in the acquisition of land for development for the public interest. Int. J. Educ. Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.; Saharan, T. Urban development-induced displacement and quality of life in Kolkata. Environ. Urban. 2019, 31, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sl. No. | Participation of the Household in Economic Activities | Response |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Income obtained from crops (Teff, wheat, barley, chickpeas, vegetables, etc.) in the past 12 months | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 2 | Income obtained from livestock and livestock products (milk, meat, live animal, eggs, sheep, goat, heifer, bull, ox, cow, horse, donkey, etc.) in the last 12 months. | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 3 | Income obtained from other jobs/employment (Daily Wage/Causal labour work) in the past 12 months | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 4 | Income obtained from business in the past 12 months | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 5 | Income obtained from semi-skilled work (pottery, carpentry, masonry, electric work, gypsum work, metal work, mechanics, etc.) in the past 12 months. | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 6 | Remittances received in the last 12 months | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 7 | Received pension income in the last 12 months | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 8 | Income from renting assets (land, house, shops, etc.) in the past 12 months | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 9 | Income from the sale of assets (land, house, shops, etc.) in the past 12 months | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 10 | Received aid/support from the government and/or NGOs in the past 12 months | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 11 | Received a loan from MFIs, banks, or informal money lenders in the past 12 months. | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| 12 | Cash on hand currently | ETB |

| 13 | Savings in a bank currently | ETB |

| 14 | Family members engaged in income-generating schemes other than agriculture. | (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| Total cash income from all sources of economic activity in the last 12 months | ETB | |

| Total Economic Capital Security Score | ||

| Economic Capital Security Index | ||

| Category of Economic Capital Security Index of the Median (1, if >=median and 0, if <median). |

| Independent Variables | Description of Variables | Expected Effect |

|---|---|---|

| X1 | Gender of the head of household (TypeHH) 1 = male, otherwise = 0. | +ve |

| X2 | categorical age of the respondent (AgeRes) (age between 18 and 65 = 1, otherwise = 0 | +ve |

| X3 | Family members engaged in continuous productive activities (income-generating activities) (FamSize) continuous | +ve |

| X4 | Literacy rate of wives (LevEdu) (Literate = 1, illiterate = 0) | +ve |

| X5 | Food security (secured = 1, not-secured = 0) | +ve |

| X6 | Social capital security (secured = 1, nonsecured = 0) | +ve |

| X7 | Land tenure security (secured/grabbed = 1, not secured/not grabbed = 0) | +ve |

| X8 | Human capital/resources security (secured = 1, not secured = 0) | +ve |

| X9 | Physical capital security(secured/above moderate = 1, nonsecured/below moderate = 0) | +ve |

| X10 | Infrastructural services security (have better access = 1, have no or little access = 0) | +ve |

| X11 | ICT security (having better access = 1, having no or little access = 0) | +ve |

| X12 | Forced eviction (evicted = 1, non-eviction = 0) | −ve |

| Dependent variable: ln(Px/(1 − Px)) | Px is the probability that the household has secured economic capital = 1, otherwise = 0 | |

| Land Type | No. of HH | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total farmland expropriated in (Ha) | 223 | 1.34 | 2.19 |

| Residential area expropriated in (m2) | 223 | 183.56 | 470.71 |

| Economic Capital Security Variables | HH Evicted | HH Non-Evicted | Weights | HH Evicted (Weighted Mean Score) | HH Non-Victed (Weighted Mean Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income from sales of (Teff, wheat, barley, chickpeas, vegetables, etc.) in the past 12 months | 0.147982 | 1 | 5 | 0.73991 | 5 |

| Income from sales of livestock (milk, meat, live animal, eggs, sheep, goat, heifer, bull, ox, cow, horse, donkey, etc.) in the past 12 months | 0.165919 | 0.843049 | 4 | 0.663676 | 3.372196 |

| Income from other jobs/employment (Daily Wage/Casual Labour Work, in the past 12 months). | 0.251121 | 0.174888 | 3 | 0.753363 | 0.524664 |

| Income from business in the past 12 months livestock trade, grain trade, etc. | 0.071749 | 0.161435 | 3 | 0.215247 | 0.484305 |

| Income from semi-skilled work (pottery, carpentry, masonry, electric work, gypsum work, metalwork, mechanics, etc.) in the past 12 months | 0.076233 | 0.35426 | 3 | 0.228699 | 1.06278 |

| Income from remittances in the past 12 months | 0.089686 | 0.058296 | 2 | 0.179372 | 0.116592 |

| Income from pension income in the past 12 months | 0.017937 | 0.017937 | 1 | 0.017937 | 0.017937 |

| Income from renting assets (land, house, shops, etc.) in the past 12 months | 0.596413 | 0.017937 | 3 | 1.789239 | 0.053811 |

| Income from distressed sale of assets (land, house, shops, etc.) in the past 12 months | 0.053812 | 0.017937 | 3 | 0.161436 | 0.053811 |

| Aid/support from government and/or NGOs in the last 12 months | 0.488789 | 0.008969 | 2 | 0.977578 | 0.017938 |

| Loans from MFIs, banks, or informal money lenders in the last 12 months | 0.026906 | 0.049327 | 2 | 0.053812 | 0.098654 |

| Currently have cash on hand. | 0.560538 | 0.569507 | 1 | 0.560538 | 0.569507 |

| Have savings in a bank at present? | 0.650224 | 0.641256 | 1 | 0.650224 | 0.641256 |

| Family members participate in income-generating schemes other than agriculture. | 0.426009 | 0.466368 | 3 | 1.278027 | 1.399104 |

| Household Economic Capital Security Index (HECSI) | 0.258808429 | 0.312940429 | 0.22969606 | 0.37257097 | |

| Total Economic Capital in ETB | 109,234.80 | 218,748.70 | 109,234.80 | 218,748.70 |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% CI for EXP(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Eviction category (1) | −1.297 | 0.373 | 12.090 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.273 | 0.132 | 0.568 |

| Gender of Household Head | −0.256 | 0.334 | 0.587 | 1 | 0.444 | 0.774 | 0.402 | 1.490 |

| Age Category | 0.315 | 0.249 | 1.603 | 1 | 0.206 | 1.370 | 0.842 | 2.230 |

| Family size category | −0.013 | 0.224 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.955 | 0.987 | 0.636 | 1.532 |

| Family member engaged | −0.279 | 0.245 | 1.295 | 1 | 0.255 | 0.757 | 0.468 | 1.223 |

| Marital Status Category | 0.643 | 0.342 | 3.534 | 1 | 0.060 | 1.902 | 0.973 | 3.718 |

| Wife Education Level | 0.365 | 0.337 | 1.171 | 1 | 0.279 | 1.441 | 0.744 | 2.791 |

| Household Head Education Level | 0.153 | 0.286 | 0.287 | 1 | 0.592 | 1.166 | 0.665 | 2.043 |

| Social Security | −0.127 | 0.256 | 0.245 | 1 | 0.620 | 0.881 | 0.533 | 1.456 |

| Land Security | 0.117 | 0.245 | 0.229 | 1 | 0.633 | 1.124 | 0.696 | 1.816 |

| Physical Capital Security | 0.860 | 0.269 | 10.194 | 1 | 0.001 | 2.364 | 1.394 | 4.009 |

| Human Security | −0.154 | 0.214 | 0.521 | 1 | 0.471 | 0.857 | 0.564 | 1.303 |

| Infrastructural Service Access Security | 0.271 | 0.262 | 1.064 | 1 | 0.302 | 1.311 | 0.784 | 2.191 |

| ICT Security | 0.583 | 0.236 | 6.106 | 1 | 0.013 | 1.791 | 1.128 | 2.844 |

| Food Security | 0.429 | 0.300 | 2.037 | 1 | 0.154 | 1.535 | 0.852 | 2.766 |

| Constant | −0.764 | 0.474 | 2.599 | 1 | 0.107 | 0.466 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gnamura, K.; Antwi, M.; Abenet, B. Effect of Forced Eviction and Land Grabs on Household Economic Capital Security of Displaced Pre-Urban Farmers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Land 2025, 14, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051051

Gnamura K, Antwi M, Abenet B. Effect of Forced Eviction and Land Grabs on Household Economic Capital Security of Displaced Pre-Urban Farmers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Land. 2025; 14(5):1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051051

Chicago/Turabian StyleGnamura, Kejela, Michael Antwi, and Belete Abenet. 2025. "Effect of Forced Eviction and Land Grabs on Household Economic Capital Security of Displaced Pre-Urban Farmers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia" Land 14, no. 5: 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051051

APA StyleGnamura, K., Antwi, M., & Abenet, B. (2025). Effect of Forced Eviction and Land Grabs on Household Economic Capital Security of Displaced Pre-Urban Farmers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Land, 14(5), 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051051