Abstract

This study offers a new framework for examining central–local government relations by distinguishing between two concepts that are usually combined: local autonomy and municipal activism. We define local or municipal autonomy as the legally defined powers and roles of local authorities, typically granted by law and state directives or reforms. Municipal activism consists of actions and decisions by local authorities that may challenge the formal boundaries of local autonomy, in a policy environment with certain attributes. This paper, using the example of Israel’s education system, examines how features of local autonomy as defined by law enhance and shape the emergence of municipal activism. We focus on the impact that incoherence and lack of clarity in legal guidance and directives may have on local policy actors’ decision making. The findings show that in uncertain and incoherent policy environments, local government tends toward municipal activism. However, the surprising findings challenge the prevailing assumptions regarding the connection between a municipality’s characteristics and its municipal activism. The findings can be applied to various policy domains, such as urban planning or sustainability policy, where the interplay between legal autonomy and municipal activism has become increasingly prevalent.

1. Introduction

Systems of local government differ substantially from one country to another [1], but they share two major aspects: They operate within legal frameworks set by the state and they are expected to be autonomous in some regard. These traits foster a fundamental tension between local autonomy and the central government’s sovereignty, constituting a persistent topic of inquiry in political research [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Specifically, scholars ask, to what extent and in what ways do these inherent tensions affect local governance, and which aspects of the state-set legal framework improve or impair the governance of local authorities?

The concept of local autonomy has come to embrace diverse phenomena and theoretical references. Many scholars refer to it as a general political development [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Others examine cities that act independently vis-à-vis the state [13,14] and innovate policies ahead of state initiatives, for example, in the field of sustainability [15] or in dealing with a pandemic [16]. Recent studies on “sanctuary cities”, which challenge central-government policies regarding irregular immigrants [17,18], and novel urban planning initiatives [19] address additional aspects of local autonomy. Yet another large body of research addresses focus on movements of local populations as part of local autonomy and city-zenship phenomena [20,21,22,23,24,25].

This scholarly interest in urban autonomy is concurrent with major policy reforms in many countries. Recent decades have witnessed a wave of decentralization reforms in most nation-states, constituting a global “quiet revolution”. Faguet [26] (p. 3) summarized these reforms, arguing that “decentralization programs across rich and poor countries are centrally motivated by a quest to improve governance.” However, he contended, this issue remains underexplored.

The current study offers a new framework for examining relations between central and local government by distinguishing between two concepts that usually appear together: local autonomy and municipal activism. Blank [5] and Schragger [10] define local or municipal autonomy as the formal authority of cities to engage in particular activities and decision making, typically granted by the ordinances and state directives or reforms that award formal authority and power to cities and localities. We follow their definitions of local autonomy as the legally defined powers and roles of local authorities. The scholarly discussion of local autonomy is often intertwined with the discussion of decentralization and devolution. Fleurke and Willemse [27] argue that although these concepts are intertwined, they are not necessarily interrelated, and that many decentralization reforms or decentralized systems do not automatically grant local autonomy; therefore, these concepts should not be conflated. This argument applies, for example, to planning and land-use policies in Israel, where a series of decentralization reforms did not result in the strengthening of local autonomy [7,28]. Thus local autonomy, as further discussed, is often not clearly or coherently defined by legal ordinances and state directives. Cha [29] for example found in a study of central–local government conflicts over educational policies in Korea in the years 2010–2014 that conflicts between the Ministry of Education and local councils, first of all, appeared to occur due to ambiguous laws and regulations. Following these reforms, scholars have examined how municipal governments have developed autonomous regulatory practices despite the top-down control system [18]. Hence, while some scholars stress that decentralization did not lead to enhanced local autonomy [27], others point to autonomous patterns that emerged. The impacts of such situations are at the center of this paper. These varied evaluations indicate that a conceptual framework that can encompass those trends is required. That is the challenge of this study.

The current study examines how features of local autonomy as defined by law enhance and shape central–local government conflicts. Following Spencer and Delvino [19], we suggest that local government action that challenges the boundaries of formal local autonomy should be considered municipal activism (MA).

We advance this line of research by focusing on the impact of incoherence and lack of clarity in legal guidance and directives on how local policy actors deal with these policy environments. The surprising research findings challenge the prevailing assumptions regarding the connection between a municipality’s characteristics and its MA. The findings show that in uncertain and incoherent policy environments, local government tends to turn to MA. This study reveals empirical evidence in the field of education, but its findings can be applied to various policy domains, such as urban planning or sustainability policy, where the interplay between legal autonomy and MA has become increasingly prevalent.

We focus on Israel for two main reasons. First, historically, Israel has been considered a highly centralized country in which the central government has formal authority in most realms of life [8,30,31]. Israel has been ranked as the most centralized among OECD countries in terms of the central government’s control over local taxation [32], land-use planning [12,33,34], and education decision making [35]. Second, since the 1970s and especially in the beginning of the new millennium, Israel has implemented simultaneously a series of reforms aimed at devolving and decentralizing its governance structure [7,16,34,36,37] which did not result in enhancing local autonomy [28]. While Israel is at the center of the current examination, it has to be stressed that similar processes took place in other countries. Britain, for example, underwent numerous similar decentralization reforms during the 1980s and 1990s, with mixed results [38]. Awortwi (2011) in a comparative study in developing and transitional countries also pointed to similar processes that took place in many of these societies [39].

The structure of this paper is as follows: The next (Section 2) focuses on the relations between central and local government, using the concepts of local autonomy and MA. The Section 3 introduces the Israeli case, reviewing major changes over time in central–local relations. The Section 4 presents the research methodology, followed by the empirical analysis and findings. The Section 5 expands the discussion and addresses the implications of the findings for central–local government relations in various areas, focusing on the spatial aspect and urban planning.

This paper offers several theoretical and practical contributions. First, it advances research on central–local relations by offering a distinction between local autonomy as defined by the legal system and central-government-led reforms, on the one hand, and MA, as decisions and actions by local policy actors, on the other. In this regard, we follow Riverstone-Newell’s [40] definition of MA as a political behavior whereby local officials leverage their institutional authority to challenge and modify unfavorable central government policies. This distinction is important because it allows us to examine clearly the nature of the linkage between local autonomy (which may be differently defined in diverse national contexts) and MA. This, in turn, allows us to encompass under MA diverse phenomena now addressed as separate, such as sanctuary cities and novelty in urban and land planning. Furthermore, our empirical study develops a framework for measuring degrees of MA that can be adapted to a variety of policy areas in diverse national settings.

1.1. Law and Central and Local Government

Municipalities operate within legal frameworks established by their state. They gain their freedom to act and their powers and capacities from the state that creates and controls their abilities and autonomy [5,10]. The law provides authoritative statements of what is conceivable in society, and legislation serves as a governance mechanism by defining rules of the game and providing predictability [41,42]. Because legal systems comprise multiple layers and components—laws, statutes, executive decrees, regulations, and judicial precedents as well as consecutive reforms—they are often fragmented, incomplete, discontinuous, and incoherent [43,44,45]. For example, as Gibton and Goldring [38] found, while educational reforms in Britain were law-based, legislation did not offer a clear and long range view of educational policy. They claim that in part this lack of clarity was a result of the numerous pieces of legislation since 1988 and the many alterations and versions that resulted in very little consolidation in the elaborate legislative process. These attributes may create an uncertain governance environment and reduced predictability for policy actors.

Organizational studies have suggested that policy environments characterized by uncertainty and low predictability—such as legal systems that impose incongruent conceptions, instructions, and directives—may have negative implications for governance, and in our case, for local governance [46,47,48,49,50,51]. Consequently, reducing the negative effects of uncertainty is considered a major aim of entrepreneurship and policy innovation [52]. However, some studies offer an alternative view of the implications of uncertainty, arguing that it may encourage innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurship. Bakir and Jarvis [53] represent this alternative view, arguing that a “degree of heterogeneity and incomplete institutionalization of practices, values, and norms” can be an enabling factor that allows actors to pursue their objectives. Griffin and Grote [54], who reviewed much of this literature, provide evidence for the positive linkage of uncertainty with creativity and innovation in organizations.

Integrating this line of research into our framework, it can be argued that the traits of the organizational environment that create uncertainty and unpredictability simultaneously constrain local policy actors and enable them to advance their policy goals. Whereas such circumstances may limit policy actors’ ability to advance certain goals, they also create opportunities for actors to mobilize their resources strategically and gain an unregulated scope for action [55]. Such conditions, we claim, facilitate MA, enabling policy actors to function as policy entrepreneurs who can identify and exploit windows of opportunity.

Municipal Activism

In conceptualizing MA, we establish two crucial theoretical distinctions. First, the term “municipal” denotes formal policy actors—elected officials and bureaucrats—thereby distinguishing MA from grassroots or citizen activism. This differentiation is crucial because “local activism” is a broader term that, in current research, encompasses both grassroots initiatives and citizen protests (see, for example, [21,25,56,57,58,59]. Second, our conceptualization builds upon Riverstone-Newell’s [40] definition of MA as a political behavior whereby local officials leverage their institutional authority to challenge and modify unfavorable central government policies. In this regard, Riverstone-Newell’s [40] definition considers local officials as policy actors acting strategically and choosing to challenge central government.

Hence, following Riverstone-Newell [40], we conceptualize MA as a spectrum of initiatives and actions by local officials in response to central government policies. This spectrum ranges from compliance and agreement to opposition and policy innovation. In this regard, we depart from the characterization by Placek et al. [58] of “activist” versus “passive” municipal leaders with regard to reactions to COVID-19. We posit that MA emerges as local policy actors strategically seek to advance policy goals and aspirations and retain local governance, that is, their ability to make policy decisions and deliver services.

We further suggest that the term MA developed here can encompass a wide range of urban phenomena. In recent years, there has been growing scholarly interest in how and why municipalities and municipal actors choose to act autonomously in various areas of policy and create policies that deviate from central government directives. These phenomena may be seen as demonstrating MA.

The two major research questions this study addresses are as follows:

Q1. What are the major features of local autonomy in Israel as defined by the legal system in general and in the field of education specifically?

In Korea, for example, previous studies found that the major source of central–local government conflicts was the ambiguity of laws and regulations [29].

On this basis we propose (H1): the legal instructions and framework in Israel are characterized by ambiguity and lack of clarity.

Q2. How is MA demonstrated, and how is it related to features of local autonomy, and which additional factors shape it?

We allude mostly to research that deals with factors that impact decision making in local authorities in times of crisis and austerity on the one hand and studies dealing with municipal innovative initiatives on the other hand. As there are no previous findings regarding municipal activism, to the best of our knowledge we refer to these studies which provide the closest context similar to the context of issues involved in municipal activism. This involves both reacting to stressful conditions and initiating ways to deal with them. Some of these studies point to the role that socioeconomics play in such cases. Cepiku et al. [59] found that local resources are related to crisis management strategies of the municipalities. Shearmur and Piorier [60] for example found that the tendency of municipalities to engage in everyday municipal administrative innovation was positively related to size, metropolitan location, and socioeconomic resources.

On this basis we propose (H2): that municipal activism will be positively related to local resources, and municipalities ranked higher on the socioeconomic scale and located in more central geographical areas would demonstrate higher municipal activism.

Van Houwelingen [61] and Lander et al. [62] found no correlation between size of municipalities and local autonomy as awarded by law, and no correlation with political participation of citizens. On the basis of these we propose the following hypothesis (H3): there is no relationship between the size of the municipalities and MA.

1.2. Central–Local Government Relations in Israel: Legal and Historical Overview

Israel provides a compelling case study of devolution in a centralized unitary state. It has been characterized by heavy central government regulation of municipalities [31,63], on the one hand, and adoption of devolutionary reforms on the other [37]. However, research has demonstrated that these reforms have not resulted in decentralization of power, as Alterman and Gavrieli [28] and Eshel and Hananel [7] have shown with regard to urban and land planning policies. Instead, central–local relations are characterized by incoherence, lack of clarity on important issues, and a history of regulatory reforms that infuse even more uncertainty.

The legal foundation of Israel’s central–local relations rests primarily on two ordinances issued during the British Mandate, before the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948: the Ordinance of Municipalities (1934) and the Ordinance of Local Councils (1941). These remain the primary sources of local-authority law [45], establishing municipalities as administrative units subject to the principle of the legality of administration. This principle stipulates that every action and authority of local government be based on legal authorization. In the absence of such authorization, a municipality lacks the power to take specific action, and any act performed without or beyond the scope of authorization constitutes a deviation from the ultra vires authority principle.

Israeli law explicitly details all issues within municipal authority, implying that what is not mentioned is excluded [64]. This is clearly demonstrated, for example, in the case of land-use and planning policy. The Israeli Planning and Building Act of 1965 created a hierarchical system of planning institutions, precisely defining the powers of each committee and the relations between the various committees [12,34,65]. However, a close examination reveals that local government authority is simultaneously based on specific particular certification instructions (only what is detailed is allowed) and general authority instructions that provide municipalities with a wide range of powers, thus merging elements of both particular and general certification of local government [64] (p. 336). To summarize, local policy actors in Israel operate in a legal space characterized by ambiguous authority boundaries, internal legal contradictions, and unclear response parameters for local needs.

To further understand the current relationship between local and central government in Israel we briefly review significant reforms over the years that have affected that relationship. The 1975 introduction of direct election of municipality heads aimed to enhance their policy-making role [36] but instead created a “fuzzy control” system that paradoxically maintained centralized influence while appearing decentralized [30]. In the 1980s, as part of the fiscal decentralization that followed an economic recession in Israel, the government changed the historic mode of financing of the municipalities, increasing the proportion of the self-generated resources of local authorities and shrinking government support from about 70% of local budgets to about 30%. However, the municipalities’ authority to recruit resources was not expanded, and central government supervision over them was not reduced; in some respects it was even enlarged [34].

This added another layer of uncertainty in the funding sources. Whereas the municipalities’ obligation to provide public services remained fixed in primary legislation, the extent of the government’s obligation to participate in the financing of these services was not regulated in legislation [66].

These changes were the main reasons for the budgetary crisis that many municipalities (especially in peripheral areas) faced at the beginning of the new millennium. This is because a large part of the opportunities to obtain economic resources (mainly through revenue-generating land uses) remained determined by the central government through decisions concerning Israel’s centralized land use policy and planning policy [7,12,16,34,36]. For comparison, 95.1% of local taxation in Israel is determined by the state as compared to 7.8% in OECD countries [35] (p. 27).

Moreover, the 1980s saw the start of decentralization of responsibility for social services but with no delegation of adequate formal authority [34,36,37,66], and funding transferred to municipalities for public services (such as health and education) was accompanied by punctilious and rigid detailing of its allocation [34,63]. Hence, paradoxically, fiscal decentralization reduced the budgetary independence of the municipalities [66].

In 2014, the Municipalities Ordinance was amended to distinguish between municipalities on the basis of their financial strength: Fiscally “strong” municipalities were granted greater autonomy, expressed in a series of easements in dealing with the central government [37]. The amendment exacerbated the socioeconomic gaps between municipalities because it did not change the national policy regarding the distribution of revenue-generating land uses [7,12].

Eshel and Hananel [7] sum up by saying that the various decentralization reforms did not enhance local autonomy. Instead, we claim, they infused uncertainty and complexity into the municipalities’ policy environment. The reforms described above were introduced as patchy pieces of legislation or government decisions that, while transferring responsibilities to municipalities, also increased the involvement of the central government [66] (pp. 220–221).

2. Materials and Methods

The research design and methodology have two main objectives: to examine the features of local autonomy in education in Israel and to examine the demonstration of MA in Israeli municipalities. This study falls into the category of small N case studies that have descriptive and exploratory purposes [67]. It attempts to describe the phenomenon of MA and explore its potential origins in the attributes of the legal system. As Gerring and Cojocary claim [67], this requires a complicated task of case selection as will be explained below.

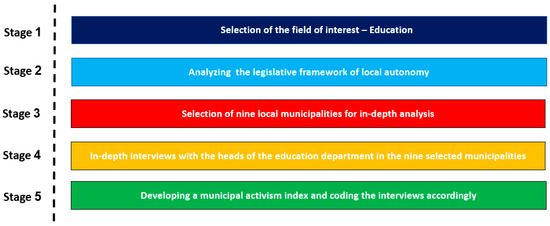

To achieve these objectives. we designed a multi-stage methodology, incorporating multiple quantitative and qualitative research methods, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research stages.

Stage 1: Selection of the field of interest—education: Examining the field of education has theoretical importance because education services are a major factor in households’ choice of where to reside [68,69,70,71,72]. This choice, in turn, may affect municipalities’ ability to generate revenue through taxation of households and commercial facilities, thus increasing local leadership’s interest in education and making it, in most countries, a major issue of local policy and politics [73].

Stage 2: Analyzing the legislative framework of local autonomy in education: We analyzed legal and administrative sources to examine the regulatory framework governing municipalities and to assess the extent of consistency and clarity of power devolution from the Ministry of Education (MoE) to local government. This examination enabled us to sketch the traits of local autonomy in Israel and illuminate the country’s complex central–local government relationship. The analysis also enabled us to seek out incoherence and contradictions that are inherent in the regulatory framework of central–local relations in Israel. Such traits may create a policy environment characterized by uncertainty and low predictability for policy actors.

Stage 3: Selection of municipalities for in-depth analysis: In order to capture the diversity of the phenomenon of MA, a descriptive case selection method is suitable, that will allow on the basis of several cases taken together to capture the diversity of a subject. To identify a small number of diverse cases from a large population of potential cases, it is needed to choose cases with different scores on parameters of interest [67] (p. 365). Our parameters of interest were four characteristics that are often used in local government studies: socioeconomic resources of the community, size, spatial dispersal by region, and financial resources and stability of the municipality. These parameters are described below.

Nine municipalities were selected for this study. First, we selected three municipalities, one from each geographic region of the country, on the basis of relationships established in previous research collaborations that suggested likely cooperation. The additional six municipalities were selected on the basis of four characteristics mentioned above as is explained in more detail below:

- (a)

- Socioeconomic cluster: Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) classifies municipalities by their socioeconomic level using a composite index. This index incorporates demographic data, living standards, municipal grants distribution, education and training levels, employment rates, unemployment figures, and pension coverage. Municipalities and local councils are ranked on a scale of 1–10 clusters, with cluster 1 representing the lowest socioeconomic level and cluster 10 the highest. In selecting the communities on this basis, we omitted the two lowest ranks (1,2) and the two highest ones (9,10) as they include very few municipalities and included municipalities in the range from 3 to 8 representing their relative frequency.

- (b)

- Spatial dispersal by district: Israel is divided into four metropolitan districts (Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Beersheva); six spatial districts (Northern, Haifa, Central, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Southern); and the Judea and Samaria District [74] as may be seen in the map attached to Table 1. The Central District surrounds the Tel Aviv District and both are located in the center of the country; the Northern and Southern districts are considered peripheral regions. The Judea and Samaria District differs from the other districts because it includes territories that are not within the state’s borders and to which Israeli law does not apply.1 We selected municipalities from four different districts (North, Central, Tel-Aviv, and South) reflecting the distribution of municipalities in the country including only the areas under Israeli law. We omitted choosing any of the metropolitan cities due to the large amount of resources they command including professional staff and networks with central government that are not comparable to other municipalities.

Table 1. The 9 municipalities that were chosen for in-depth analysis (p. 12).

Table 1. The 9 municipalities that were chosen for in-depth analysis (p. 12). - (c)

- Size (population): While studies regarding size of municipalities in the EU often use the NUTS classification2, Israeli municipalities are not classified according to NUTS, as Israel is not included in the EU. Hence, we classified municipalities into three size categories on the basis of population size: large municipalities (150,000–300,000 residents, excluding metropolitan cities), medium municipalities (50,000–150,000 residents), and small municipalities (fewer than 50,000 residents).

- (d)

- Financial independence: Financially independent municipalities in Israel, as designated by the Ministry of Interior, enjoy certain autonomies, including exemption from ministerial budget approval. This financial independence is a crucial measure of central–local government relations and substantially affects municipalities’ ability to provide public services, particularly in education. Table 1 below presents the location on each of the localities included in the study on each of the four characteristics.

Although it is common in studies to refer to the question of whether local political actors join membership in dominant national political parties, in our case this cannot be applied, because of the direct personal elections for mayors. Mayors in Israel are elected on a personal basis since 1975. Mayors may run as heads of an independent local party or may be aligned to a party that also runs for elections to parliament. Most mayors are elected on a personal basis without affiliation to the national party. For example, in the elections for local municipalities held in Israel in 2024, only 22% of the elected mayors were affiliated with a national party [75]. In our study, six of the mayors headed an independent local party.

To protect participants’ confidentiality, because each local authority has only one education department head, the participating municipalities are designated by letters A through I. This anonymization was necessary because identifying the municipalities would have revealed the participants’ identities.

We selected nine municipalities that reflect the diversity of Israeli municipalities across the key dimensions of socioeconomic cluster, spatial dispersal, size, and financial independence. With this selection, we aimed to provide a comprehensive representation of Israel’s local government landscape.

Stage 4: In-depth interviews with the heads of the education department in the nine selected municipalities: This study included in-depth interviews with the heads of the education department in all nine selected municipalities. The interviews were conducted face-to-face or via Zoom, lasted approximately one hour each, and took place over nearly six months, during the second half of 2022. The protocol of questions focused on asking the interviewees to specify specific policy advancement attempts, the conflicts with central government regarding such policy initiations, how such conflicts were resolved, and with what outcomes.

Stage 5: Developing a municipal activism index and coding the interviews accordingly: In the final stage, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the interviews to explore a demonstration of MA, as presented in detail in the analysis section.

Obstacles and Challenges

In qualitative studies based on the analysis of policy documents or in-depth interviews, there is always the question of how generalizable the conclusions can be from the small number of cases presented. Therefore, the designed methodology prioritized diversity over focusing solely on large, resourceful municipalities that typically dominate local government research. Our sample represents varied socioeconomic levels, sizes, locations, and financial capacities. Through in-depth interviews and material we received from the heads of the education departments, who cooperated fully, we developed a four-dimensional framework for measuring MA. This framework offers a replicable methodology for future research and a comparative tool for analyzing factors that correlate with MA intensity. This diverse sample and systematic measurement approach helps to mitigate the limitation of sample size while providing valuable insights into local government dynamics and enabling a comparison between municipalities with diverse characteristics.

During the coding process, we faced two major challenges. The first was to define the line where local decisions and activities clearly deviate from central government directives and thus should be delineated as confrontational or oppositional. To overcome it, we looked for a specific central government directive (an objective trait) and examined the municipality’s attitude toward it. Hence, we chose attempts by local government to intervene in MoE pedagogical decisions, which by law lie solely within the ministry’s authority (77). Second, it was necessary to identify when local actors chose to follow, and not confront, central government directives. Because such behavior is usually invisible and more difficult to trace, we used self-reporting by local policy actors when they stated that they chose not to challenge central government decisions, even though they thought these decisions were not beneficial for their community.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Legal Framework of Education in Israel

Elementary and secondary education in Israel, which are in the focus of this research, are included in the same legal framework and the law of compulsory education (1949). Higher education is regulated separately since 1958 by the Council of Higher Education Law [76]. This study addresses elementary and secondary education.

The Compulsory Education Law (1949) identifies the formal responsibility for education in Israel in reference to elementary education. Section 7(b) [45] divides responsibility between the MoE and local authorities, but the division is not clear. According to law (Compulsory Education Law, Section 7), Gibton [77] (p. 443) claimed, “the local authorities responsibility lies only in the areas of building new schools, maintaining them technically, and designing and implementing enrollment policies—subject to government guidelines and court rulings. All the rest lies with the central government”. At the same time, the State Education Law, 1953, and the Education Ordinance (new version, 1978), stated in Section 7(b) of the Compulsory Education Law, also states that “official educational institutions for the provision of free elementary education under this Act to children and adolescents…shall be maintained by the state and the local education authority jointly…” [78] (p. 147, our emphasis). Gal-Arieli [78] also points that “in order to clarify this undefined ‘joint maintenance’ of educational institutions, various acts, ordinances and regulations were passed that sought to demarcate more explicit lines of authority and responsibility.” Interpretations of “jointly” are both formal and informal.

On the other hand, over the years, an approach has developed whereby the MoE has taken responsibility for pedagogical matters, and local authorities are responsible for matters related to physical infrastructure and maintenance. This ruling referred both to elementary and secondary education (High Court of Justice 2910/04).3

Gibton [77] further claims that the outdated educational legislation combined with waves of reforms created a state of anomie and a murky policy landscape at the local level. We may conclude by saying that because of the incoherent and unclear granting of power between the central government and local authorities, and sporadic developments that have become partially institutionalized, local policy actors operate in a policy environment characterized by uncertainty and low predictability.

Hence, the field of education in Israel provides a suitable context for examining issues of decentralization, local autonomy, and MA. Israel, as mentioned, has one of the most centralized education systems among OECD countries [32]. However, some argue that the Israeli MoE has gradually withdrawn from the design of education policies [77] and that large segments of the education system are run with only meager control of the MoE. These contrasting evaluations underscore the need for a conceptual framework that can integrate seemingly contradictory observations.

3.2. Analysis of In-Depth Interviews:

We developed coding of the degree of MA in education, using four dimensions and assigning values based on the demonstrated level of MA, particularly regarding their relation to MoE policies. We analyzed the interviews coding the answers into thematic units [79] that allow to reveal the various patterns of MA demonstrated in the different municipalities based on the below explained dimensions. Each dimension represents municipal decisions and activities, ranging from lack of activism to MA. Each decision or action of the municipality in that area was scored on the relevant range.

As Table 2 shows, each dimension received a different number of points according to evaluation of their potential impact on the relationship with MoE, depending on its weight, as explained below:

Table 2.

Dimensions for analysis and the coding system.

- Opposition to MoE Policy (0–4 points): This dimension evaluates the intensity and impact of confrontations with MoE policies, and as such is the primary indicator of MA. This dimension received the widest range (0–4). We assessed both the scope of opposition and the potential for generating systemic changes.

- Local Education Initiatives (0–2 points): These are initiatives based on statutory MoE authority that allows for such initiatives. Hence, they score lower than the above category. Local education initiatives represent the municipalities’ efforts to fill the gap left in education service delivery by central government, aligned with local priorities and resident preferences. The score is assigned according to the number of initiatives and how significant they are.

- COVID-19 Crisis Response (0–1 point): Given that data collection occurred near the end of the COVID-19 period, and considering the complex central–local government dynamics during the pandemic, we included a specific analysis of MA in pandemic response. The findings focus on central–local government conflicts regarding school closure decisions. The COVID-19 crisis highlighted varying responses among municipalities to central government directives. Whereas the central government provided specific instructions about education operations, particularly regarding school closures and reopening, the municipalities’ responses ranged from strict compliance (0 points) to independent decision making that sometimes departed from national guidelines (1 point).

- Modifications in curricula (0–1 point): Modifications regarding the core curriculum received binary scoring for presence or absence. Israel’s MoE mandates the core curriculum for all education institutions. Municipalities may supplement this curriculum but are not permitted to implement alternative curricula. Consequently, local intervention in curricular matters remains limited.

The result of the scoring scheme of the dimensions is described over a continuum, on a scale of values ranging theoretically from 0 to 8, and represents the MA level of each municipality. The final range is between 2 and 6, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Municipal activism of the municipalities.

The analysis shows MA should be conceptualized as a spectrum. At one end, HMA (high MA) involves direct challenges to the central authority. At the opposite end, LMA (low MA) is characterized by conflict avoidance and acceptance of central government policies, even when local leaders view these policies as inadequate for their populations’ needs.

3.2.1. The Intensity of MA

The coding analysis produced scores between 2 and 6, enabling us to identify two distinct levels of MA: medium-high (5–6) and medium-low (2–3). Interestingly, there was a clear division between these groups, with no municipalities scoring in the middle range. To illustrate the forms of MA, we present evidence from our interviews, offering direct quotes that exemplify medium-high and medium-low activism.

Medium-High MA

Five municipalities demonstrated medium-high MA (MHMA). They represent different sizes, different socioeconomic levels and financial independence, and different districts:

- (a)

- Municipality A, a medium-size municipality in the Periphery-Northern District, declared by the MoF not to be financially independent, socioeconomic cluster 5 (score 6);

- (b)

- Municipality B, a small municipality in the Periphery-Northern District, not financially independent, socioeconomic cluster 5 (score 6);

- (c)

- Municipality F, a large municipality in the Central District, financially independent, socioeconomic cluster 7 (score 6);

- (d)

- Municipality E, a large municipality in the Tel Aviv District, financially independent, socioeconomic cluster 7 (score 5);

- (e)

- Municipality I, a small municipality in the Periphery-Southern District, not financially independent, socioeconomic cluster 3 (score 5).

In these municipalities ranked by us as demonstrating MHMA, we also encountered many examples of actions by local policy actors that led to confrontations with central government policies. As examples, we consider challenges to pedagogical decisions that are clearly within the authority of the MoE:

- School Closure Decision: The MoE has the sole authority to make this decision. However, the mayor of Municipality F (socioeconomic cluster 7) unilaterally decided to close a school despite the MoE’s disapproval. The resulting conflict concluded with the ministry eventually approving the closure for the following year.

- Policy Change Initiative: A modestly resourced municipality (Municipality A, cluster 5) secured a special arrangement for funding youth-at-risk services by challenging budget allocation rules and called for an overall reform in this regard for all municipalities. Whereas the MoE created an exception rather than change general policy, this represents a successful local initiative in securing a desired outcome.

- Systemic Policy Reform: Another cluster 5 municipality (Municipality B), operating under special financial government supervision because of a financial crisis, successfully advocated for reducing the required local matching funds for social services from 25% to 5% for all Northern municipalities, demonstrating how local activism can lead to broader policy changes.

All five municipalities demonstrated local education initiatives: a large number in Municipalities A, E, F, and I, and a smaller number in Municipality B. Municipalities B, F, and I demonstrated independent decision making and departed from national guidelines during the COVID-19 crisis, and Municipalities E and F demonstrated involvement in MoE curricula.

Because we view MA as an agency concept, we asked how local policy actors perceive MA, in the sense of decisions to accept or challenge central government policy. An interesting example can be seen in Municipality I (cluster 3), where the head of the local education unit attested to the sense of power that local actors have vis-à-vis central government:

When I ran the education department at the beginning of my career, I thought that the Ministry of Education was all-powerful and their word was sacred. After a few years, I realized I could act in opposition to the ministry’s opinion. As soon as I understood this, things turned around…The heads of the [local] education administrations know today that they have authority. The Ministry of Education also knows this and knows that it is better to be their partner and not to fight them.

In the case of the interviewee from Municipality F (with the highest grade of MA), it is apparent that the specific conflicts and confrontations discussed above were congruent with views regarding the more general trends of change in central–local government relations: “The education departments of the municipalities have actually been transformed in recent years from administrative units to pedagogical systems”.

This conception challenges the legal framework, which explicitly denies pedagogical authority to municipalities, and creates the potential for conflict with the national education administration.

Medium-Low MA

Four municipalities—of different districts, sizes, socioeconomic clusters, and degrees of financial independence—demonstrated medium-low MA (MLMA):

- Municipality D, a medium-size municipality in the Central District, financially independent, socioeconomic cluster 8,the highest among the municipalities included in this study, (score 3);

- Municipality C, a medium-size municipality in the Periphery-Northern District, not financially independent, socioeconomic cluster 6 (score 2);

- Municipality G, a medium-size municipality in the Tel Aviv District, not financially independent, socioeconomic cluster 5 (score 2);

- Municipality H, a small municipality in the Periphery-Southern District, not financially independent, socioeconomic cluster 4 (score 3).

None of the four municipalities resisted broad MoE policy changes and engaged in mostly local activities. Three (Municipalities C, D, and H) demonstrated a large number of local education initiatives, and Municipality G a smaller number. Three (Municipalities D, E, and H) showed independent decision making during the COVID-19 crisis; none demonstrated involvement in MoE curricula.

As can be seen, MLMA was demonstrated also in a strong and financially stable municipality in the Central District (Municipality D). In this locality, it was expressed in the way that proper relations between the local level and central level were perceived: “What is not mine is not mine. You have to understand where your place is and to know how to let go [of decisions that should be made by central government]”.

In municipality C, socioeconomic cluster 6, the view was described thus: “If there is tension, we discuss the tension, and when we disagree, there are things that are within the municipalities’ decision-making scope, and there are those within the scope of the Ministry of Education”. Another example comes from Municipality G, socioeconomic cluster 5: “In the end there are directives from the director general of the Ministry of Education, so there are standards that must be met. I do what I want within the limits allowed me”.

3.3. Aggregative Analysis

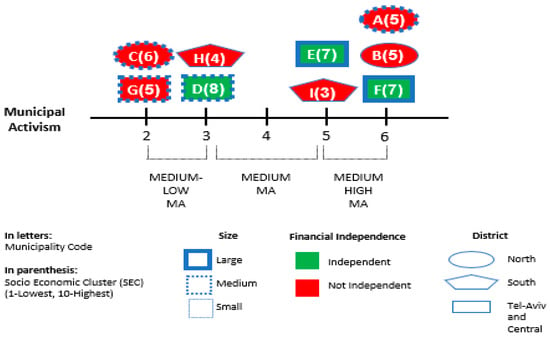

In the final stage, we examined the relation between the intensity of MA and the characteristics of the locality (socioeconomic level, spatial location, number of residents, financial independence) described earlier. Therefore, we placed the various variables on a single axis, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Integrative analysis range.

The following aggregative analysis addresses the propositions offered above regarding the relationships between socioeconomic and spatial attributes of the municipalities and the patterns of MA.

One might assume that a large locality in the center of the country, with a high socioeconomic level and financial independence, would tend to be more municipally active. However, when we combined the characteristics of the municipalities and the intensity of MA, the findings were surprising. As shown in Figure 2, contrary to what might be expected, we found no clear relationship between a municipality’s financial strength and its level of MA. This was particularly evident in the case of Municipality D, which, despite being officially designated as financially independent, demonstrated only medium-low MA.

Geographic location similarly proved to be an unreliable predictor of MA levels. The highest levels of MA were found in Municipalities A and B, both located in the Peripheral-Northern District, whereas some municipalities located in the Central District near major commercial centers, such as Municipalities G and D, displayed lower levels of MA.

The conventional assumption that larger municipalities would demonstrate higher levels of MA because of their greater resources and capacity was also challenged by our findings. Municipality B, despite its small size, showed the highest level of activism among all sampled municipalities. Conversely, several medium-size municipalities (C, D, and G) demonstrated only medium-low levels of MA.

Perhaps most striking was the absence of any clear correlation between socioeconomic cluster and MA. Municipalities A and B, with a medium socioeconomic cluster (5), and Municipality I, with a lower socioeconomic cluster (3), all demonstrated high levels of MA, whereas municipalities including C, D, and G, with higher socioeconomic clusters (6, 8, and 5, respectively), showed only medium-low levels of MA. These findings suggest that MA operates independently of traditional indicators of municipal capacity and status, and point to the potential influence of other, less tangible factors in determining a municipality’s approach to innovation and autonomy in education.

The apparent disconnect between municipal characteristics and MA levels can be better understood through our interview findings. These revealed that resource differences do not necessarily determine whether an authority engages in MA, but rather influence how that MA takes shape and what goals it pursues. Disadvantaged municipalities typically follow two distinct paths to activism. The primary path emerges when the municipality struggles to mobilize resources for service provision, leading to activism aimed at changing central government’s policies of resource allocation or redistribution, or requesting more autonomy in resource mobilization. The second path reflects attempts to establish some measure of autonomous education leadership regarding specific issues, especially those related to acknowledged needs and demands of the local population.

In contrast, medium-high MA in more affluent municipalities typically expresses a different set of motivations and goals. It often reflects their attitude of high professional capacity, and activism frequently aims to secure recognition of local leaders as pioneers in innovative education policies rather than as only addressing resource shortages.

Medium-low MA, though present across the socioeconomic spectrum, also manifests differently depending on municipal resources. Affluent municipalities often choose low activism strategically, maintaining the ability to advance their policy preferences through direct resource deployment rather than confrontation with central government. This represents a form of “quiet autonomy,” enabled by resource availability. Conversely, disadvantaged municipalities are often pushed into low-key activity by necessity, constrained by limited organizational or professional capacity to engage in disputes with powerful state actors. Their position is further complicated by heavy dependence on central government resources and goodwill.

This nuanced understanding helps explain why traditional municipal characteristics do not predict MA levels directly: similar levels of MA can emerge from vastly different resource contexts, driven by diverse motivations and manifesting through different strategies of municipalities.

4. Discussion

This study offers a look at central–local government relations, based on the distinction between two concepts: local autonomy and MA. Local autonomy consists of the legally defined relationship and division of power between central and local government. MA refers to how local governments choose to act within the boundaries and powers that the legal system—that is, the local autonomy—grants them. These two concepts are often used interchangeably [27], including diverse phenomena in the same categories and thus blurring their analytical usefulness. Distinguishing between them may make a fruitful contribution to further studies.

Building on this distinction we further explored theoretically and empirically the linkage between local autonomy, as defined in the legal system of each country, and its potential impact on MA. We addressed incoherence, ambiguity, and contradictions within legal systems that create a policy space with unclear rules. Such policy environments may have both constraining and enabling impacts for local actors. Organizational and policy entrepreneurship theory point to impairing impacts on policy performance, but they also point to such contexts as offering opportunities and driving innovation and novel ways of acting [48,49,51,53,54]. We argue that this two-faced nature of uncertainty in the policy environment establishes the theoretical link between local autonomy as a systemic variable and MA as an agency concept referring to political actors. Policy actors operating in such a policy environment may seek innovative and entrepreneurial ways to deal with local issues and adopt high MA, or resort to low levels of activity and display low MA, as demonstrated in this study.

Moreover, the distinctions offered between local autonomy and MA, and the suggested ways of looking at linkages between them, allow for studies that compare the attributes of local autonomy in diverse national systems and examine their linkage to MA. Although our study focused on the field of education, the conceptual framework is applicable to the comparative study of other fields of central–local government relationship, such as land policy and urban planning.

Turning to our empirical findings, as we proposed, we indeed found local autonomy as defined by legal ordinances, acts, and reforms to create an uncoherent and ambiguous policy environment for local policy actors in Israel. Such policy environments as previous studies, and our study as well, confirm, are characterized by conflicts between central and local government actors and lead policy actors to MA.

Another important finding that emerges from the empirical study is that, contrary to expectations, our findings do not show consistency between MA and socioeconomic level, spatial dispersal, or demographic and financial attributes of the municipality. Municipalities that scored high or low on these characteristics showed similar patterns of MA.

We suggest that these findings be explained by looking at the differences between local autonomy and MA offered here. As suggested, when local autonomy is an ill-defined policy environment, how local policy officials will act tends to be uncertain. Such situations are both constraining and enabling for policy actors and provide obstacles and opportunities. As organizational theory suggests, such circumstances may impair performance but may also lead to innovative and entrepreneurial modes of action [54]. We further suggest that one way to explain the low correlation between MA and the socioeconomic, demographic, and financial resources of municipalities is to view MA as one type of entrepreneurial behavior. Municipal activists share with policy entrepreneurs the drive to influence policy outcomes using innovative ways to promote their policy goals [80,81]. We suggest that insights from entrepreneurship theory be integrated in further research to explain why certain policy actors choose a high level of MA.

5. Conclusions

The empirical study of local autonomy and MA in Israel pointed to the usefulness of the distinctions offered here. Our analysis of local autonomy as defined by Israel’s legal system and many reforms over the years revealed an incoherent division of powers and responsibilities between central and local government. Indeed, we argue that the contradictory evaluations offered by previous studies of the Israeli system, as being the most centralized while having “omnipotent” local government [36], seem to reflect the attributes of local autonomy and varieties of MA to which we call attention.

Our empirical study points to additional possible lines of research. First, though most extant research naturally focuses on highly visible activities that challenge the central government, our study shows the need to shed light also on the less visible pole—low MA, a strategy adopted by local actors, sometimes even when they view it as detrimental to their local populations. How and why such decisions are made, in highly resourced municipalities or in poor ones, requires further research.

Second, our sample did include municipalities with a range of socioeconomic dimensions, including financial resources and stability, socioeconomic attributes of the local population, size, and location (ranging from periphery to central). The findings allow for some tentative generalizations: The intensity of MA was not related to the socioeconomic and demographic attributes of the municipalities. Affluent municipalities and poor municipalities displayed medium-high MA, and other affluent municipalities displayed medium-low MA. These findings require further study of the factors that contribute to shaping the type of linkage between local autonomy and specific types of MA. In this regard, the present study, though small, enlarges the realm of municipalities studied with regard to activism, because most research that deals with such phenomena as sanctuary cities or planning initiatives focuses on central and large cities.

The generalizations that emerge from this study are limited by the small number of municipalities included, and by its being conducted in a single national context and a single policy field. To overcome these limitations, the usefulness of the framework offered has to be examined in additional national contexts as well as in additional policy fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S.R., G.M., A.M. and R.H.; Methodology: O.S.R., G.M. and R.H.; Software, O.S.R. and R.H.; Validation, O.S.R., G.M., A.M. and R.H.; Formal Analysis, O.S.R., G.M., A.M. and R.H.; Investigation, O.S.R.; Resources, O.S.R., G.M., A.M. and R.H.; Data Curation, O.S.R.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, O.S.R., G.M., A.M. and R.H.; Writing—Review and Editing, O.S.R., G.M. and R.H.; Visualization, O.S.R. and R.H.; Funding Acquisition, O.S.R., G.M. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research by The Bloomberg-Sagol Center for City Leadership at Tel Aviv University.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor, and the anonymous reviewers for their useful and challenging comments, which have strengthened the paper. Special thanks to Ophir Pines Paz and Sivan Landman. We thank the interviewees, directors of education departments in the municipalities whose names cannot be mentioned. We thank Gaddy Radom for the cartography assistance and for the support along the way.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The administration of the Judea and Samaria District is responsible only for the settlement areas in Area C in Judea and Samaria, which are not part of the State of Israel but are under its control (Meydani and Shohet Radom, 2025). Hence, this district was not included in our study. |

| 2 | More about the NUTS classification is here: Overview—NUTS—Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics—Eurostat. |

| 3 | High Court of Justice 2910/04)—The Federation of Local Authorities in Israel v. The Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Finance. |

References

- Franzke, J.; Linze, S. Beyond charter and index: Reassessing local autonomy. In The Future of Local Self-Government: European Trends in Autonomy, Innovations and Central-Local Relations; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R.A. The city in the future of democracy. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1967, 61, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffin, M. Central–local relations in an era of governance: Towards a new research agenda. Local Gov. Stud. 2009, 35, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. Control and Power in Central-Local Government Relations; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Y. Urban legal autonomy and (de) globalization. Raisons Polit. 2020, 3, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menahem, G. Arab citizens in an Israeli city: Action and discourse in public programmes. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1998, 21, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshel, S.; Hananel, R. Centralization, neoliberalism, and housing policy central–local government relations and residential development in Israel. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2019, 37, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meydani, A. Political Entrepreneurs and Public Administration Reform: The Case of the Local Authorities’ Unification Reform in Israel. Int. J. Public Adm. 2010, 33, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V.; Pratchett, L. Local governance under the coalition government: Austerity, localism and the ‘Big Society’. Local Gov. Stud. 2012, 38, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schragger, R. City Power: Urban Governance in a Global Age; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ladner, A.; Keuffer, N.; Baldersheim, H. Measuring local autonomy in 39 countries (1990–2014). Reg. Fed. Stud. 2016, 26, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hananel, R. Planning Discourse versus Land Discourse: The 2009–2012 Reforms in Land-Use Planning Policy and Land Policy in Israel. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1611–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.; Nowak, J. The New Localism: How Cities Can Thrive in the Age of Populism; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, I.; Duyvendak, J.W. Understanding governmental activism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2017, 16, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreurs, M.A. From the bottom up: Local and subnational climate change politics. J. Environ. Dev. 2008, 17, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hananel, R.; Fishman, R.; Malovicki-Yaffe, N. Urban diversity and epidemic resilience: The case of the COVID-19. Cities 2022, 122, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauder, H. Sanctuary cities: Policies and practices in international perspective. Int. Migr. 2017, 55, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.; Delvino, N. Municipal activism on irregular migrants: The framing of inclusive approaches at the local level. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2019, 17, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, N.; Mualam, N. How do cities foster autonomous planning practices despite topdown control? Cities 2022, 123, 103576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, A.; Holston, J. Cities and citizenship. Public Cult. 1996, 8, 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Menahem, G. Cross-border, cross-ethnic, and transnational networks of a trapped minority: Israeli Arab citizens in Tel Aviv-Jaffa. Glob. Netw. 2010, 10, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, N. Ecological city-zenship. Environ. Politics 2020, 29, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Shalit, A. Thinking like a city, thinking like a state. In Cities vs. States: Should Urban Citizenship be Emancipated from Nationality? Bauböck, R., Orgad, L., Eds.; European University Institute: Florence, Italy, 2020; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. To Live as a Cityzen: Class-Based Cosmopolitan Cityzenship. In Transnational Student Return Migration and Megacities in China: Practices of Cityzenship; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Avni, N. Cities fight for autonomy: A view from an ongoing protest in Israel. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2024, 31, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faguet, J.P. Decentralization and governance. World Dev. 2014, 53, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleurke, F.; Willemse, R. Measuring local autonomy: A decision-making approach. Local Gov. Stud. 2006, 32, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterman, R.; Gavrieli, E. Between Extreme Centralization and Hesitant Decentralization. In Haifa: The Center for Urban and Regional Studies; The Technion—Israel Institute of Technology: Haifa, Israel, 2008. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Cha, S.H. Decentralization in educational governance and its challenges in Korea: Focused on policy conflicts between central and local government in education. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2016, 17, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dery, D. Fuzzy control. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2002, 12, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razin, E. Needs and impediments for local government reform: Lessons from Israel. J. Urban Aff. 2004, 26, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, Y. Reorganization of Relationships Between Local Authorities and the Ministry of Education (Discussion Paper); Van-Leer Institution: Jerusalem, Israel, 2012. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, E. Planning rights in theory and in practice: The case of Israel. Int. Plan. Stud. 2007, 12, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hananel, R. Distributive Justice and Regional Planning: The Politics of Regional Revenue Generating Land Uses in Israel. Int. Plan. Stud. 2009, 14, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkenstein, A. Local Government in Israel: General Background, Core Issues and Challenges; Israel Democracy Institute: Jerusalem, Israel, 2020. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Elia, N. The Fourth Generation: New Local Government in Israel, 2nd ed.; The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies: Jerusalem, Israel, 2006. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Beeri, I.; Yuval, F. New Localism and Neutralizing Local Government: Has Anyone Bothered Asking the Public for Its Opinion? J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 623–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibton, D.; Goldring, E. The role of legislation in educational decentralization: The case of Israel and Britain. Peabody J. Educ. 2001, 76, 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Awortwi, N. An unbreakable path? A comparative study of decentralization and local government development trajectories in Ghana and Uganda. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2011, 77, 347–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riverstone-Newell, L. Bottom-up activism: A local political strategy for higher policy change. Publius J. Fed. 2012, 42, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meydani, A. The Israeli Supreme Court and the Human Rights Revolution: Courts as Agenda Setters; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, G.; Quack, S. Law as a Governing Institution. In Glenn Morgan, and others [Eeds]. The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Institutional Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, H.L.A.; Green, L. The Concept of Law, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gellman, R.M. Fragmented, incomplete, and discontinuous: The failure of federal privacy regulatory proposals and institutions. Softw. LJ 1993, 6, 199. [Google Scholar]

- Meydani, A.; Shohet Radom, O. Local government in Israel: A multidisciplinary view. In Local Government Law; Yagil, L., Ed.; The Open University of Israel Publishing House: Raanana, Israel, 2025; Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, R. Perceived environmental uncertainty in public organizations: An empirical exploration. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2008, 32, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourou, L.; Himick, D.; Saadi, S. Regulatory uncertainty and corporate social responsibility. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 55, 104020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latan, H.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Wamba, S.F.; Shahbaz, M. Effects of environmental strategy, environmental uncertainty and top management’s commitment on corporate environmental performance: The role of environmental management accounting. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulen, H.; Ion, M. Policy uncertainty and corporate investment. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2016, 29, 523–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menahem, G.; Gilad, S. Policy Stalemate and Policy Change in Israel’s Water Sector 1970–2010: Advocacy Coalitions and Policy Narratives. Rev. Policy Res. 2016, 33, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeter, P.; Sandberg, J. Constraining or enabling green capability development? How policy uncertainty affects organizational responses to flexible environmental regulations. Br. J. Manag. 2017, 28, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.S.; Melwani, S.; Goncalo, J.A. The bias against creativity: Why people desire but reject creative ideas. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, C.; Jarvis, D.S. Contextualising the context in policy entrepreneurship and institutional change. Policy Soc. 2017, 36, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Grote, G. When is more uncertainty better? A model of uncertainty regulation and effectiveness. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meydani, A. The design of land policy in Israel: Between law and political culture. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. First world urban activism: Beyond austerity urbanism and creative city politics. City 2013, 17, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, A.; Lebuhn, H.; Rattner, G. Between neoliberal governance and the right to the city: Participatory politics in Berlin and Tel Aviv. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 704–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaček, M.; Špaček, D.; Ochrana, F. Public leadership and strategies of Czech municipalities during the COVID-19 pandemic–municipal activism vs municipal passivism. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2021, 17, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepiku, D.; Mussari, R.; Giordano, F. Local governments managing austerity: Approaches, determinants and impact. Public Adm. 2016, 94, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearmur, R.; Poirier, V. Conceptualizing nonmarket municipal entrepreneurship: Everyday municipal innovation and the roles of metropolitan context, internal resources, and learning. Urban Aff. Rev. 2017, 53, 718–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Houwelingen, P. Local autonomy, municipal size and local political participation in Europe. Policy Stud. 2018, 39, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladner, A.; Keuffer, N.; Baldersheim, H. Final Report. Tender No 2014.CE.16.BAT.031: Self-rule Index for Local Authorities (Release 1.0); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dery, D.; Schwartz-Milner, B. Who Governs Local Government; Israel Democracy Institute: Jerusalem, Israel, 1994. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rosen-Zvi, I. The Essence of Local. Law Gov. 2009, 12, 333–406. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Razin, E. Government Reform in Israel: Between Centralization and Decentralization; The Floresheimer Institute for Policy Studies: Jerusalem, Israel, 2003. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Y. The Place of the Local: Local Government Law, Spatial Inequality and Decentralization in Israel. Mishpatim 2004, 34, 197–299. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Gerring, J.; Cojocaru, L. Selecting Cases for Intensive Analysis: A Diversity of Goals and Methods. Sociol. Methods Res. 2016, 45, 392–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiebout, C.M. A pure theory of local expenditures. J. Political Econ. 1956, 64, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasington, D.M.; Haurin, D.R. Educational outcomes and house values: A test of the value-added approach. J. Reg. Sci. 2006, 46, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fack, G.; Grenet, J. When do better schools raise housing prices? Evidence from Paris public and private schools. J. Public Econ. 2010, 94, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azary-Viesel, S.; Hananel, R. Internal migration and spatial dispersal; changes in Israel’s internal migration patterns in the new millennium. Plan. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hananel, R.; Berechman, J.; Azary-Viesel, S. Join the Club: Club Goods, Residential Development, and Transportation. Sustainability 2022, 15, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowson, R.L.; Goldring, E.B. The new localism: Re-examining issues of neighborhood and community in public education. In Yearbook of National Society for the Study of Education; University of Michigan Library: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009; Volume 108, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hananel, R.; Azary-Viesel, S.; Nachmany, H. Spatial gaps–Narrowing or widening? Changes in spatial dynamics in the new millennium. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, A. Analysis of the Results of the 2024 Local Government Elections; Israel Democracy Institute: Jerusalem, Israel, 2024. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Menahem, G. The transformation of higher education in Israel since the 1990s: The role of ideas and policy paradigms. Governance 2008, 21, 499–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibton, D. Post-2000 law-based educational governance in Israel: From equality to diversity? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2011, 39, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal-Arieli, N.; Beeri, I.; Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Reichman, A. New localism or fuzzy centralism: Policymakers’ perceptions of public education and involvement in education. Local Gov. Stud. 2017, 43, 598–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L.; Quincy, C.; Osserman, J.; Pedersen, O.K. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol. Methods Res. 2013, 42, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M.; Norman, P. Policy entrepreneurship and policy change. Policy Stud. J. 2009, 37, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.; Aviram, N.F. Street-level bureaucrats and policy entrepreneurship: When implementers challenge policy design. Public Adm. 2021, 99, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).