1. Introduction

The World Cities Report by UN-Habitat states that urbanization will remain a major driver of global growth and will gradually become a key tool to address common challenges [

1,

2]. In China, under the deep integration of the global sustainable development agenda and the strategy of new-type urbanization, coordinating new-type urbanization and rural revitalization has become a core path to achieve high-quality and sustainable development. This coordinated process is directly linked to the local implementation of SDGs 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDGs 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDGs 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). At the same time, China’s territorial spatial planning provides a framework for urban–rural coordination, shaping development through zoning, infrastructure, and land-use controls. The Proposals of the CPC Central Committee for Formulating the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan clearly call for “industry supporting agriculture” and “cities supporting rural areas”. It aims to build a new relationship between industry and agriculture, and between urban and rural areas. This relationship would be characterized by mutual promotion, complementarity, coordinated development, and shared prosperity. This provides clear policy guidance for the coordinated development of the two systems. Furthermore, the 2023 No. 1 Central Document emphasized building livable, employable, and harmonious villages. This outlines specific directions for aligning rural revitalization with new-type urbanization. In practice, these goals are increasingly implemented through spatial planning instruments like urban development boundaries, ecological redlines, and permanent farmland protection, which collectively constrain and guide settlement expansion and service provision. In practice, China has made clear progress in urban–rural coordination. By 2023, the urbanization rate of the resident population reached 66.16% [

3]. In infrastructure connectivity, the total length of rural roads exceeded 4.6 million kilometers [

4], and all eligible townships and administrative villages had paved road access and regular bus services (SDGs 9.1). In public service sharing, counties achieved basic balance in compulsory education, and basic medical insurance in urban and rural areas covered more than 1.3 billion people [

5] (SDGs 3.8). However, structural challenges remain for urban–rural coordination. By the end of 2023, the per capita disposable income of urban residents was 2.39 times that of rural residents [

6], and there were clear per capita gaps in public spending for basic public services (SDGs 10). Factor flows were not fully open in both directions. Two-way flows of capital, talent, and technology between urban and rural areas were still weak. At the same time, the rural domestic sewage treatment rate was only about 40% [

7], and the coordination of urban–rural environmental governance needs to improve (SDGs 6.3). Some of these frictions are spatial in nature, reflecting mismatches between the location of jobs and housing, fragmented service catchments, and uneven land-development intensity.

The theoretical view of urban–rural relations has moved from rigid separation to interactive integration. In development economics, Lewis [

8] proposed the dual-sector model of “agriculture-industry” and saw urbanization as the shift in surplus labor from the traditional sector to the modern sector. This model reveals the basic logic of structural change but assumes a static divide between urban and rural areas. Myrdal [

9] proposed the “backwash and spread” effects and used a cumulative causation framework to explain the non-linear impact of growth poles, which first draw in factor resources from nearby regions and then release spillovers. Lipton [

10] put forward the “urban bias” thesis and argued that a long-term tilt of policy resources toward cities harms rural welfare. To move beyond the simple dualism, the literature turned to the urban–rural linkage. Chambers [

11] proposed a participatory development paradigm and, at the methodological level, set a people-centered path for integrated governance. Tacoli [

12,

13] argued that urban and rural areas form a continuum joined by flows of people, capital, and information, rather than a strict binary. Robeyns [

14], based on the capability approach, defined development as the expansion of human well-being and opportunity sets. This gives a normative basis for the equalization of public services and access to opportunities across urban and rural areas. Guided by these theories, China’s fast urban–rural development offers rich empirical settings. The focus has moved from speed-led expansion to the quality of urbanization-rural coordination. Chen et al. [

15] brought new-type urbanization and rural revitalization into an integrated perspective and stressed a shift from one-way factor flows to two-way urban–rural interaction. Zhang, Fan, and Fang [

16] used provincial data to make scenario projections and argued that, with coordinated expansion of infrastructure and public services, China may reach a high level of integration around the mid-century. For measurement, Wu [

17] proposed multidimensional indicators under a unified scale to depict the link among policy, land, and factors. Yin et al. [

18] reviewed evidence and found that land consolidation has net positive effects on industrial prosperity and well-being, and is an important lever to raise the coupling level. For spatial patterns, Pan et al. [

19] built a four-dimensional index of urban–rural integration and showed clear spatial heterogeneity and geographic constraints across the country. In fragile ecological zones such as the north slope of the Tianshan Mountains and the Loess Plateau, Helili and Zan and Huang et al. [

20,

21] found that environmental carrying capacity, industrial structure, and spatial organization interact, and that a one-size-fits-all approach is not feasible. For mechanism identification, He, Li, and Wang [

22] showed that transport infrastructure can raise accessibility, promote cross-regional factor flows and rural industrial upgrading, and then foster urban–rural integration. In contrast, Ma, Tang, and Dombrosky [

23] on tourism-led urbanization noted that the speed and quality of urban and rural development can be out of step at times, and that rural industry, public services, and community governance need to improve at the same time.

In summary, research since 2022 has driven more in-depth and broader development in the field of urban–rural relations, with discussions becoming more systematic and perspectives increasingly diverse. They explain the mechanisms of urbanization and rural development, build multidimensional frameworks for new-type urbanization and rural revitalization, and carry out related measurements. They also reveal spatial heterogeneity and the roles of land policy, transport, and public services. However, many studies focus on static coordination of development levels. The synchronization of development speed between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization has received less attention. The links between multidimensional indicators and specific channels of urban–rural interaction are also not always clear. There is still a lack of integrated frameworks that connect these theories with China’s territorial spatial planning practice in a single analytical model.

This study responds to these gaps in three ways.

First, it builds a comprehensive evaluation system and a coupling-coordination analysis framework for new-type urbanization and rural revitalization, and it covers both development level and development speed.

Second, it views the two systems as interacting through economic, infrastructural, ecological, and social-digital channels, and uses this view to guide indicator selection and model analysis.

Third, to analyze the spatiotemporal evolution patterns and driving mechanisms of the coupling and coordinated development between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization, this study integrates an improved coupling-coordination model, Dagum Gini decomposition, kernel density estimation, and the Geographical Detector. Within the framework of territorial spatial planning, it further explores how to design region-specific policy systems that facilitate a shift from mere “level upgrading” to the coordinated optimization of the two systems.

Unlike market-led urban–rural transition models in many countries, China stresses the joint role of government guidance and market mechanisms. China advances urban–rural integration through institutional innovation, policy coordination, and factor reforms. This path reflects Chinese characteristics and also offers useful lessons for the world, especially for developing countries that seek coordinated urban–rural transformation. Using quantitative coordination metrics in spatial planning can help direct investment, services, and boundary control to support long-term urban–rural coordination.

Conceptually, new-type urbanization and rural revitalization are neither parallel nor isolated policy agendas, but two interdependent subsystems of an integrated urban–rural development strategy. New-type urbanization focuses on people-centered and quality-oriented transformation on the urban side, emphasizing industrial upgrading, spatial optimization, public service expansion, and digital-green transitions in cities and towns. Rural revitalization, in turn, concentrates on removing structural constraints on the rural side through “thriving businesses, pleasant living environment, social etiquette and civility, effective governance, and prosperity”, so as to rebuild rural industries, communities, and ecosystems. The two are linked by flows of people, land, capital, and data. When viewed within China’s territorial spatial planning system, they can be understood as two mutually reinforcing adjustment processes within a single urban–rural system. If either side lags or becomes unbalanced, problems such as hollow villages, inefficient land use, and segmented public services will emerge and weaken the overall coupling-coordination of development.

On this basis, this study builds an analytic framework for two interacting systems: new-type urbanization and rural revitalization. It follows a people-centered and coordinated development approach and aims to explain their meanings, structures, and joint role in high-quality and sustainable development. New-type urbanization advances rural development through three main pathways. On the economy, city industries spread to nearby rural areas and add new energy [

24,

25]. For example, the Lanshan District in Linyi, Shandong, used its wholesale markets to set up many micro industrial parks, helping nearby villages offer jobs close to home. In terms of infrastructure, an urban–rural transport network speeds up the flow of goods and services [

26,

27]. A representative case is Guangdong’s three-tier logistics system linking counties, towns, and villages. In the cultural sphere, urbanization brings modern culture together with rural traditions [

28]. For instance, Xinye Village in Jiande, Zhejiang Province, renewed traditional folk activities and attracted large numbers of visitors, achieving both heritage transmission and economic gains.

Rural revitalization also supports new-type urbanization in three ways. For factor supply, rural areas provide cities with high-quality agricultural products and a steady labor force [

29]. In ecological services, rural areas serve as green buffers that support urban ecology [

30,

31]. For example, Dongli District in Tianjin expanded forests and restored wetlands to provide environmental protection for the city. Rural communities also preserve local culture, which keeps shared memories and emotions alive for both urban and rural residents. This helps bring society together and supports balanced development. Tangqian Township in Liancheng County, Fujian Province, has created a community cultural center that brings traditional culture to life in today’s world.

The coupling and coordination mechanism refers to the process in which multiple subsystems in a complex system co-evolve under non-linear interactions [

32]. Its main features are as follows. First, feedback linkages: subsystems exchange matter, energy, and information, which maintain and strengthen their relations [

33]. Second, dynamic equilibrium: despite fluctuations, the system remains relatively coordinated and ordered [

34]. Third, threshold effects: when the degree of coupling crosses a critical point, the system may undergo a qualitative shift and reorganization [

35]. In this study, these ideas provide the theoretical basis for using a coupling-coordination model to measure the joint evolution of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization, and for linking empirical results with policy tools in territorial spatial planning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

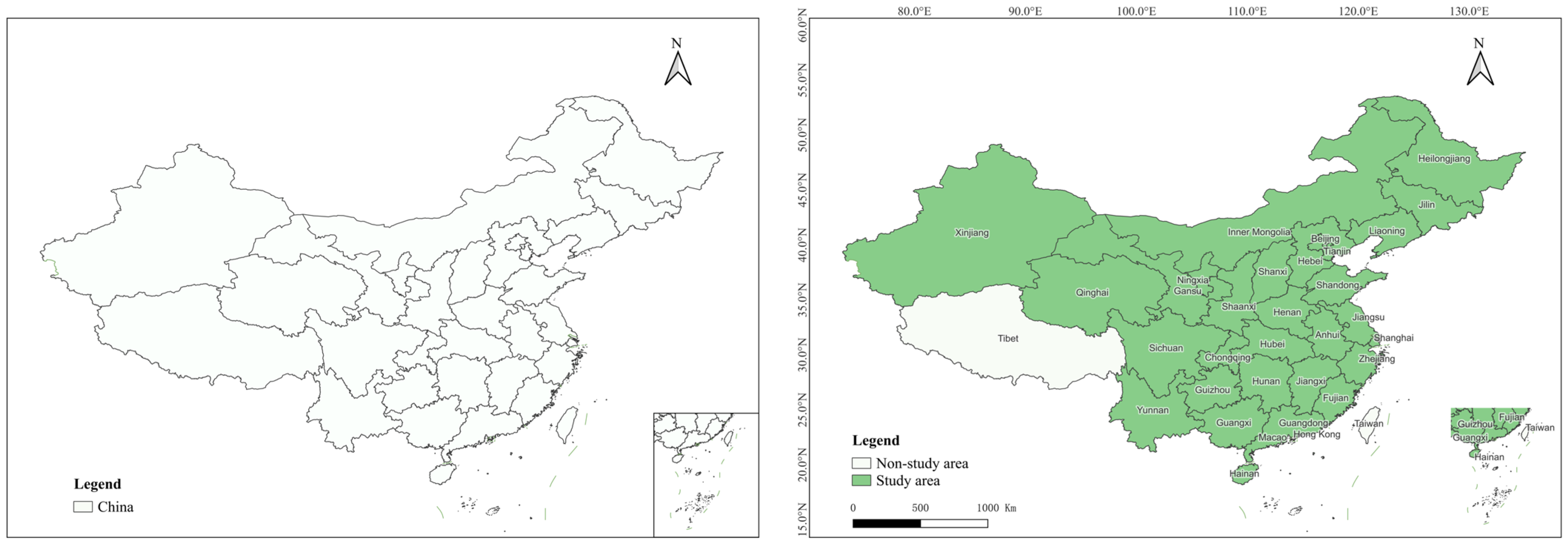

This study takes 30 provincial-level units in China as the study area for the period 2014–2023. The geographic range is roughly between 73° E and 135° E, and between 18° N and 54° N. The area stretches a long distance from north to south and from east to west. Climate types are diverse, and landforms are complex.

Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of the 30 provinces.

Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, and Hainan are located in eastern China. These provinces and municipalities lie along the coastline. Plains, deltas, and hilly or mountainous areas are mixed in this region. The North China Plain, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Pearl River Delta are mostly flat. The coastal areas of Zhejiang and Fujian are dominated by low hills. Hainan is mainly composed of tablelands and hills. Economic activity in these provinces is highly concentrated. Urban density is high, the population is large, and land development intensity is high. As a result, constraints on construction land are more pronounced.

Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, and Hunan are located in central China. This region lies in the middle reaches of the Yellow River, the Yangtze River, and the Huai River. Plains, basins, and hilly areas coexist in this area. Overall, the terrain is relatively gentle, and the agricultural base is strong. The urban system tends to follow major transport corridors and main rivers.

Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang are located in western China. This region covers a very large area. It includes the Inner Mongolian Plateau, the Loess Plateau, the Sichuan Basin, the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, and intermountain basins in Xinjiang. Energy, mineral, and hydropower resources are abundant. At the same time, the distribution of population and land is uneven. Natural conditions are harsh in some parts of the region. In particular, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang in Northwest China have low rainfall and fragile ecosystems. Problems such as wind erosion, sandstorms, and drought are more prominent there.

Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang are located in northeastern China. This region is mainly composed of the Songliao Plain and the Sanjiang Plain. The terrain is open and mostly flat. Soils are fertile, and the climate is cold. The region is a typical old industrial base and an important commercial grain-producing area. Cities are concentrated along major railway lines and rivers. Agriculture and heavy industry account for a large share of the regional economy. Seasonal frozen soil and low temperatures have clear impacts on infrastructure and agricultural production.

This study does not include Tibet, Taiwan, Hong Kong, or Macao in the study area. The main reason is data availability and comparability. For Tibet, many indicators in the index system have serious missing values during 2014–2023, especially those related to innovation, logistics services, and environmental governance. Including Tibet would require extensive interpolation and could distort the results. For Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao, the statistical systems and indicator definitions differ from those of mainland provinces. Some key variables are not reported in a continuous and consistent way in national statistical yearbooks. To maintain a balanced panel and to ensure that the composite indices are based on comparable data, this study limits the sample to 30 provincial-level units in mainland China (including provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions) with relatively complete and consistent data.

2.2. Construction of a Multidimensional Evaluation Indicator System

Based on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the connotations of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization, separate comprehensive evaluation systems are constructed for the two systems. These systems meet the requirements of the local implementation of the SDGs and are consistent with the goals of Chinese modernization. Drawing on the relevant literature [

36,

37], a set of representative, measurable key indicators is selected, and the measurement framework is constructed accordingly.

2.2.1. Selection and Construction of Indicators

New-type urbanization is people-centered. Its development includes population agglomeration and upgrading of the industrial structure. It also includes the rational layout of basic public service infrastructure and transport networks, and the rise in consumption capacity [

38]. The comprehensive evaluation system covers five dimensions: economic development, social development, spatial structure, green ecology, and innovation and digitalization. As shown in

Table 1.

For new-type urbanization, the indicators are selected to reflect five basic dimensions: economic development, social development, spatial structure, green ecology, and innovation and digitalization. Within each dimension, the indicators aim to capture different but related aspects of the same concept.

In the economic development dimension, per capita GDP measures the overall level of economic output. The share of the tertiary sector reflects the upgrading of the industrial structure, and the share of service consumption shows the shift in the consumption structure toward services. The urbanization rate links this economic base to the concentration of population in cities. These indicators are related, but they describe level, structure, demand, and population pattern separately.

In the social development dimension, higher education students per 10,000 people, health professionals per 1000 people, social organizations per 100,000 people, pension insurance participants per 10,000 people, and public library collections per capita together describe human capital, health security, social participation, social protection, and cultural services. They form a chain from basic education and health to social security and cultural resources, and they complement each other.

In the spatial structure dimension, public transport vehicles per 10,000 people and urban road area per capita reflect the intensity of transport service supply. The share of urban construction land in built-up area and transport line density describes land-use patterns and network connectivity. Together, they show how people and economic activities are organized and connected in space.

In the green ecology dimension, urban sewage treatment rate, harmless disposal rate of household waste, the share of environmental protection spending, SO2 emissions per unit of GDP, and urban park green area per capita jointly describe environmental pressure, treatment capacity, fiscal support, and green space provision. They represent different stages in the environmental management process.

In the innovation and digitalization dimension, mobile internet data per capita shows the depth of digital application. R&D expenditure as a share of GDP reflects innovation input, and granted invention patents per 10,000 people capture innovation output. These indicators together represent a basic “input–application–output” chain of innovation and digital development.

Rural revitalization is industry-driven and covers industrial upgrading, accessibility of public services, environmental governance, community governance, and income growth. Its comprehensive evaluation system has five dimensions: thriving businesses, pleasant living environment, social etiquette and civility, effective governance, and prosperity. As shown in

Table 2.

For rural revitalization, the indicators are selected to reflect four core dimensions: thriving businesses, pleasant living environment, social etiquette and civility, effective governance, and prosperity. Within each dimension, the indicators describe different but related aspects of the same concept.

In the thriving businesses dimension, land efficiency, machinery power per unit area, and labor productivity measure how efficiently land, capital, and labor are used in agriculture. The share of primary industry in GDP links farm production to the regional economy, while the share of rural retail sales in total retail sales reflects the strength of local markets and rural demand. Together, these indicators describe both production capacity and market vitality.

In the pleasant living environment dimension, public toilets per township and the share of townships with centralized water supply capture basic sanitation and safe drinking water. Village road hardening rate and township road area per capita show transport conditions and physical access. Township green coverage rate reflects environmental quality. These indicators jointly describe whether rural settlements are clean, convenient, and environmentally friendly.

In the social etiquette and civility dimension, township cultural stations per 10,000 people, health technicians per 1000 rural residents, and the share of spending on education, culture and recreation reflect access to culture, health, and human-oriented consumption. The teacher-student ratio in compulsory education and rural TV coverage show basic education quality and information access. Together, they capture human development, public awareness, and cultural life.

In the effective governance dimension, the shares of townships with construction management institutions and with a master plan measure grassroots planning and spatial management capacity. The share of rural residents covered by the minimum living allowance reflects the strength of the rural safety net. These indicators describe how local governments plan, regulate, and protect rural communities.

In the prosperity dimension, per capita disposable income, cars per 100 rural households, residential floor area per capita, and rural household broadband accounts per 10,000 people capture income, assets, housing conditions, and digital connectivity. These are interrelated outcomes of the above dimensions and summarize the material and digital living standards that rural revitalization seeks to improve.

Our selection of indicators for new-type urbanization and rural revitalization follows three principles: data availability, operational feasibility, and representativeness. The indicator system can depict the multidimensional features of their coupling and coordination. It can also reveal the interactions between urban and rural areas and their joint contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals. In addition, the policy and institutional background for each indicator has been summarized in

Appendix A (

Table A1).

2.2.2. Explanation of Indicator Redundancy and Robustness

Because our empirical framework is based on aggregation- and distance-type methods, the main concern is indicator redundancy. We first examined the correlation structure of both indicator systems. For new-type urbanization (21 indicators), pairwise correlations range from −0.463 to 0.880; only 4 out of 210 pairs have |r| > 0.80, about 69.5% of pairs have |r| < 0.40, and the average correlation is around 0.24. For rural revitalization (22 indicators), correlations range from −0.670 to 0.812; only 1 out of 231 pairs has |r| > 0.80, about 70.6% of pairs have |r| < 0.40, and the average correlation is about 0.10. This indicates that near-perfect collinearity is absent and that most indicators provide non-overlapping information. In addition, the CRITIC-entropy scheme explicitly uses both variance and inter-indicator correlations when computing contrast information, so that indicators highly correlated with many others naturally receive lower weights in the composite indices.

We further tested the robustness of the composite indices and the coupling-coordination degree. First, we re-estimated the indices using equal weights for all indicators (1/21 for new-type urbanization and 1/22 for rural revitalization). The equal-weight indices are highly consistent with the baseline CRITIC-entropy indices (Pearson r = 0.972 for new-type urbanization and r = 0.905 for rural revitalization), and the resulting coupling-coordination degree remains very similar (Pearson r = 0.967; Spearman ρ = 0.978). Second, we removed the indicator with the largest weight in each system-“invention patents granted per 10,000 people” (weight = 0.1093) for new-type urbanization and “student–teacher ratio in compulsory education at the township level” (weight = 0.07346) for rural revitalization—re-estimated the CRITIC-entropy weights for the remaining indicators, and recalculated the indices. The reduced-form indices still show very high agreement with the baseline ones (Pearson r = 0.989 and r = 0.914 for the two systems), and the coupling-coordination degree remains highly stable (Pearson r = 0.978; Spearman ρ = 0.981). These results suggest that our main temporal trends and spatial patterns are not driven by a few highly correlated or high-weight indicators and are robust to reasonable changes in the weighting scheme and indicator set.

2.3. Data Sources

This study employs panel data from 30 provincial-level administrative units in China spanning the period 2014–2023. Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Tibet are excluded from the analysis due to the presence of significant data gaps for certain indicators, as well as inconsistencies in statistical definitions that preclude their direct integration into a unified framework for computation and comparison. The raw data come from the China Statistical Yearbook, the China Rural Statistical Yearbook, the China Urban–rural Construction Statistical Yearbook, statistical bulletins of the relevant years, and official government websites. To preserve dataset completeness, a small number of missing values in the raw series are filled by simple linear interpolation between adjacent years. Linear interpolation is applied only to the original level data, and all growth-rate indicators are calculated afterwards from these completed level series. This avoids interpolating the growth rates themselves, which could otherwise introduce bias into year-on-year changes. Missing values are concentrated in a few variables and years. In the new-type urbanization index, three raw variables—the number of public transport vehicles, the area of urban construction land, and the built-up area of cities—lack data for 2022 for all 30 provinces. These variables are used to construct two indicators: public transport vehicles per 10,000 people and the ratio of construction land area to built-up area. In the rural revitalization index, the raw series for rural population is missing for 2020, and the raw series for the number of township cultural stations is missing for 2017. In addition, the raw series for “rural internet access users” is missing for 2016 in Shanghai. For these gaps, values are interpolated linearly from adjacent years at the provincial level. In total, 90 raw data points are interpolated in the new-type urbanization index, and 61 raw data points are interpolated in the rural revitalization index. Given this pattern and the small number of interpolated cells relative to the full panel, the impact of interpolation on the composite indices and on the coupling-coordination measures is expected to be limited.

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. Methodological Framework

The logical structure of this study is shown in

Figure 2 below. It presents the main research stages, the methods used, and the indicator system within the Sustainable Development Goals framework.

2.4.2. Data Standardization

Because the indicators differ in direction, units, and scale, direct comparison is difficult. Therefore, this study applies the min-max normalization method to standardize the raw data. For each indicator, the minimum and maximum values are calculated using all 30 provinces over the entire period 2014–2023, and these overall minimum and maximum values are then used to rescale the indicator to the [0, 1] range. This normalization removes unit effects and keeps a fixed scale over time, ensuring that the results are comparable across both provinces and years.

Here,

θ denotes the year;

i denotes the province (i = 1, 2, …, n);

j denotes the indicator (j = 1, 2, …, m);

Xθij is the raw value, and Yθij is the normalized value;

Xjmin and Xjmax are the minimum and maximum of the raw data for indicator j in year θ, respectively.

2.4.3. CRITIC-Entropy Combined Weighting

To ensure objectivity and scientific rigor in the multidimensional evaluation, a combined weighting strategy is adopted. First, the entropy method (Equation (3)) is applied to compute initial information weights based on the dispersion of each indicator. Second, the CRITIC method (Equation (4)) is employed to calculate weights that account for both the coefficient of variation and the conflict (correlation) among indicators, thereby complementing the entropy method. On this basis, the two sets of weights are integrated to construct a combined weighting model (Equation (5)) that reflects differences in information content and captures inter-indicator linkages. This improves the accuracy and reliability of the overall evaluation framework.

The symbols are defined as follows:

the weight of indicator j calculated by the entropy method;

the share of province i in indicator j relative to the total of that indicator;

the entropy value of indicator j;

the weight of indicator j calculated by the CRITIC method;

the standard deviation of indicator j;

the correlation coefficient between indicators i and j;

the combined weight of indicator j.

2.4.4. The TOPSIS Method

The TOPSIS method ranks alternatives by measuring how close each one is to an ideal target. It relies on objective data, so it can reflect the real status of each alternative [

39]. In this study, the CRITIC-entropy combined weighting is employed to assign composite weights to all indicators in the two systems of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization, and weighted matrices are constructed. TOPSIS is then applied to evaluate the development levels of the two systems for 30 provinces during 2014–2023, yielding the annual composite development index for each system.

The symbols are defined as follows:

the weighted matrix determined by the CRITIC-entropy combined weighting;

the ideal best alternative;

the ideal worst alternative;

the Euclidean distance from alternative i to ;

the Euclidean distance from alternative i to ;

the relative closeness of alternative i to the ideal solution, that is, the composite development index.

2.4.5. Coupling-Coordination Evaluation Model

- (1)

Classical Coupling Coordination Evaluation Model (CCE)

The coupling coordination model can quantify the level of coordinated development that arises from interactions within and between systems, and it can show how this coordination evolves over time [

40]. Using the TOPSIS method, composite development indices are first obtained for new-type urbanization and for rural revitalization. The coupling-coordination model is then applied to empirically assess coupling strength, coordination degree, and their temporal changes between the two subsystems.

The symbols are defined as follows:

C is the coupling degree between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization;

T is the comprehensive coordination index of the two systems;

α and β are coefficients to be set. Treating the two systems as equally important, set α = 0.5 and β = 0.5;

D is the coupling coordination degree, with a range of [0, 1]. A value of D closer to 1 indicates a higher level of coupling coordination between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization.

- (2)

Improved Coordination Evaluation Model

The traditional coupling coordination model mainly measures synchronization and coordination between systems. It does not directly capture the “speed effect” of development. The improved model, based on growth rates and separation, builds a two-system evaluation framework (GSCE). It emphasizes the identification of coordination in growth speed. This provides an operational tool to understand the relative growth pace and dynamic matching between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization [

41].

is the growth rate of the new-type urbanization index;

is the growth rate of the rural revitalization index;

St is the separation based on growth rates. It measures the relative difference in development speed between the two systems and takes values in (−1, 1);

k is an adjustment parameter, usually in [0.1, 0.5]. It avoids a zero denominator or S = ±1 when the signs of the two growth rates differ. A smaller k makes the model more sensitive to growth-rate differences. Set k = 0.3;

Ct′ is the coordination measure for speed. If Ct′ > 0, the speed of new-type urbanization is higher than that of rural revitalization. If Ct′ < 0, the speed of new-type urbanization is lower. The closer |Ct′| is to 1, the higher the coordination in growth speed. The closer it is to 0, the more serious the mismatch. Sign(⋅) is the sign function.

The GSCE model is applied only to the speed dimension to identify coordination in development speed between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization. For all other empirical analyses, the CCE model is employed, with its coupling-coordination degree D used as the basis.

2.4.6. Dagum Gini Coefficient

Among many methods for measuring regional gaps, the Dagum Gini coefficient allows decomposition of spatial disparities. In this paper, the subgroup decomposition of the Dagum Gini coefficient is employed to examine spatial differentiation in the coupling and coordination between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization across Chinese provinces. This method effectively addresses the sources of spatial variation and the issue of overlap between sub-samples [

42]. The basic definition of the Dagum Gini coefficient is given by the following formulas.

G is the overall Gini coefficient,

is the mean level of coupling and coordination;

n is the sample size, and k is the number of subgroups;

yji(yhr) is the coupling-coordination level of province i in region j(h);

nj(nh) is the number of provinces in region j(h).

When decomposing the Gini coefficient, the provinces must first be ordered by the mean level of coupling-coordination, as in Equation (15).

Then, use Equations (16) and (17) to compute within-region differences Gjj and between-region differences Gjh;

Equation (18) gives the within-region contribution to the Gini coefficient Gw;

Equation (19) gives the net between-region contribution Gnb;

Equation (20) gives the overlapping contribution Gt;

The overall Gini coefficient can be decomposed as: G =

Gw +

Gnb +

Gt denotes the share of provinces in region j within the full sample; denotes the share of the total coupling-coordination level of region j in the total across all provinces in the sample.

2.4.7. Kernel Density Estimation

Kernel density estimation is a nonparametric method for estimating a probability density function. It does not assume any specific distribution. Instead, it uses the data to produce a smooth estimate of the distribution shape. It is well-suited for exploratory analysis and can reveal actual features such as multimodality and skewness [

43]. In this paper, kernel density estimation is employed to examine the dynamic evolution of absolute differences in the coupling and coordination between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization in China.

The symbols are defined as follows:

N is the number of observations;

Xi is the coupling-coordination degree of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization for province i;

K(⋅) is the kernel function; the Gaussian kernel is adopted in this study;

h is the bandwidth.

2.4.8. Geographical Detector

The Geographical Detector is a set of statistical methods used to detect spatial differentiation and its driving factors. It does not rely on linear assumptions and has a clear physical meaning. If the study area is divided into several subregions and the sum of within-layer variances is smaller than the total variance of the whole region, spatial differentiation exists. If the spatial distributions of an independent variable and the dependent variable are consistent, there is a significant statistical association between them [

44].

The Geographical Detector includes four modules: factor detector, interaction detector, risk detector, and ecological detector. The factor detector tests whether a given factor explains the spatial differentiation of a target variable. The interaction detector identifies whether factors act independently or interactively. In this paper, the factor and interaction detectors are employed to examine spatial differentiation in the coupling and coordination between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization in China and to identify the underlying driving forces.

The symbols are defined as follows:

q measures the effect of a factor on the spatial differentiation of W. Its range is [0, 1]. A larger q means a stronger influence of the factor on the spatial variation in the coupling-coordination degree; a smaller q means a weaker influence.

h = 1, …, H denotes the partitions of factor X or dependent variable Y. Nh is the number of units in stratum h. N is the number of units in the whole region.

is the variance of Y in stratum h. is the variance of Y in the whole region.

Factor detector measures the explanatory power of a single independent variable X for the dependent variable Y. Using X as the basis for stratification, compute and test its significance. A larger indicates stronger explanatory power.

Interaction detector identifies the type of interaction when any two driving factors act together on Y. First, compute the independent explanatory powers and for the two factors. Then overlay the two layers to form the joint stratification , and compute its explanatory power . Finally, compare the magnitudes of , , and , and determine the interaction type according to standard decision rules. Common rules are as follows:

< : Nonlinear weakening;

< < : Unifactor nonlinear weakening;

< : Bifactor enhancement;

: Independent (additive) effect;

<

: Nonlinear enhancement.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Development Levels in New-Type Urbanization and Rural Revitalization

Using the CRITIC-entropy combined weighting method, weights are first assigned to all indicators of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization, as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Based on these weights, the TOPSIS method is then used to measure the development levels of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization for 30 provincial-level regions in China during 2014–2023.

Figure 3a shows the trend of the new-type urbanization index across regions. Overall, the index rises steadily in all regions. The eastern region has the highest level, and the northeast has the lowest level. This pattern is consistent with China’s efforts to implement SDG 11, which aims to build inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities and human settlements.

Figure 3b shows the development of each dimension of new-type urbanization. The green ecology dimension stays above the other dimensions and is relatively stable. This reflects steady attention and practice in environmental health and climate action (SDGs6/13). The innovation and digitalization dimension lagged before 2017 but then rose quickly. This suggests a clear rise in digital infrastructure and innovation capacity (SDG 9), which supports jobs and productivity (SDG 8).

Figure 3c shows the evolution of the rural revitalization index across regions. The eastern region has the highest overall level. The central and western regions lag behind, but the west has grown faster since 2017 and has gradually surpassed the central region. This convergence helps narrow regional gaps (SDG10) and is consistent with progress in poverty reduction and shared growth (SDGs1/8).

Figure 3d further shows differences across the dimensions of rural revitalization. Effective governance has the highest composite score and remains stable, which reflects steady gains in grassroots governance capacity and institutional performance (SDGs16). Prosperity has the lowest score at the start, but it grows steadily. By 2021, it surpasses pleasant living environment, and by 2023, it is close to social etiquette and civility. This suggests continuous improvement in household income and multidimensional well-being (SDGs1/8).

In sum, both new-type urbanization and rural revitalization in China show a steady upward trend during 2014–2023, and the gaps across dimensions within each system have gradually narrowed.

3.2. Analysis of the Coupling Coordination Degree Between New-Type Urbanization and Rural Revitalization

3.2.1. Analysis of the Coupling Coordination Degree Between the Development Levels of the Two Systems

Using the CRITIC-entropy combined weighting, the coupling-coordination degree between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization is measured for Chinese provinces during 2014–2023. Coordination types are then classified according to the scheme of Xi Yu et al. [

45], as shown in

Table 5.

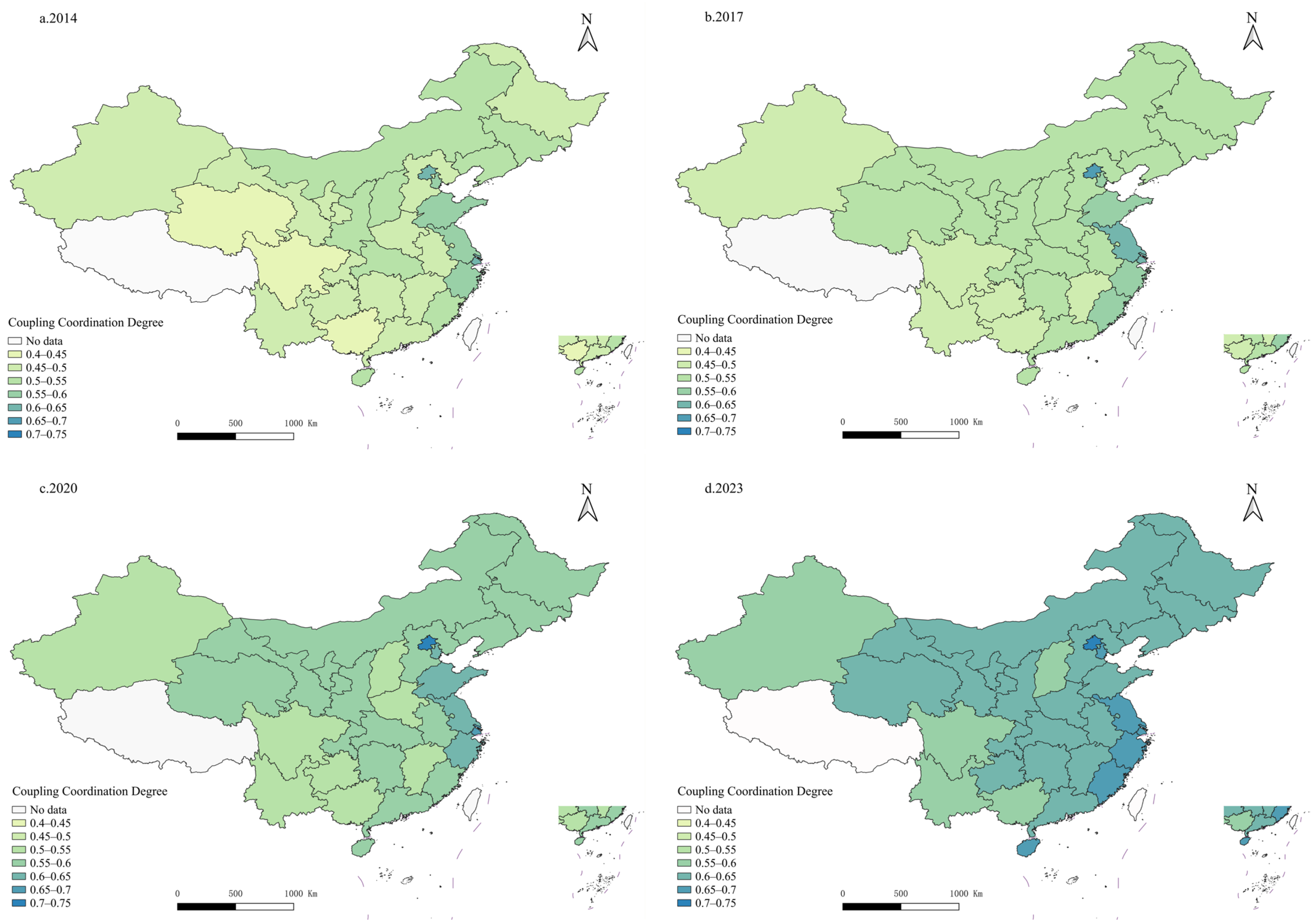

Using QGIS 3.40, the spatial pattern of the coupling-coordination degree between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization for China’s provinces is visualized and analyzed for four key years: 2014, 2017, 2020, and 2023. The results are shown in

Figure 4 and

Table 6. Overall, during the study period, the two systems show clear temporal evolution and marked spatial differentiation in their coupling coordination levels.

From the temporal perspective, the coupling coordination degree increases steadily in most provinces. In 2014, many provinces were still at the stages of “verge of disorder” or “barely coordination”. By 2023, most had reached “primary coordination”, and some developed provinces achieved “moderate coordination”. This trend shows substantial progress in promoting urban–rural development and regional coordination in China.

From the spatial perspective, the coupling coordination degree shows a clear gradient of “eastern lead and central-western catch-up”. In the eastern coastal region, Beijing’s value rose from 0.630 in 2014 to 0.727 in 2023. Since 2020, it has entered and remained at moderate coordination. Shanghai stays at primary coordination over the whole period, with values between 0.640 and 0.685. Its level is high, and the increase is steady. Both cities remain in the lead. This pattern reflects favorable location, strong economic bases, and early policy pilots in the region. These conditions foster positive interactions between urban and rural systems.

In the central and northeast regions, most provinces make a key shift from barely coordination to primary coordination. For example, Hebei, Heilongjiang, and Anhui moved from the verge of disorder in 2014, through barely coordination, to primary coordination by 2023. This suggests that regional strategies such as the rise in the central region and the revitalization of the northeast have supported urban–rural coordination within these areas.

In the western region, although the foundation is relatively weak, the improvement is strong. Provinces such as Qinghai, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, and Gansu have moved out of verge of disorder and reached primary coordination or barely coordination by 2023. Notably, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region remained barely coordinated in 2023, but their values are close to the threshold of primary coordination, which indicates clear potential and room for further improvement.

3.2.2. Analysis of the Coupling Coordination Degree in the Development Speed of the Two Systems

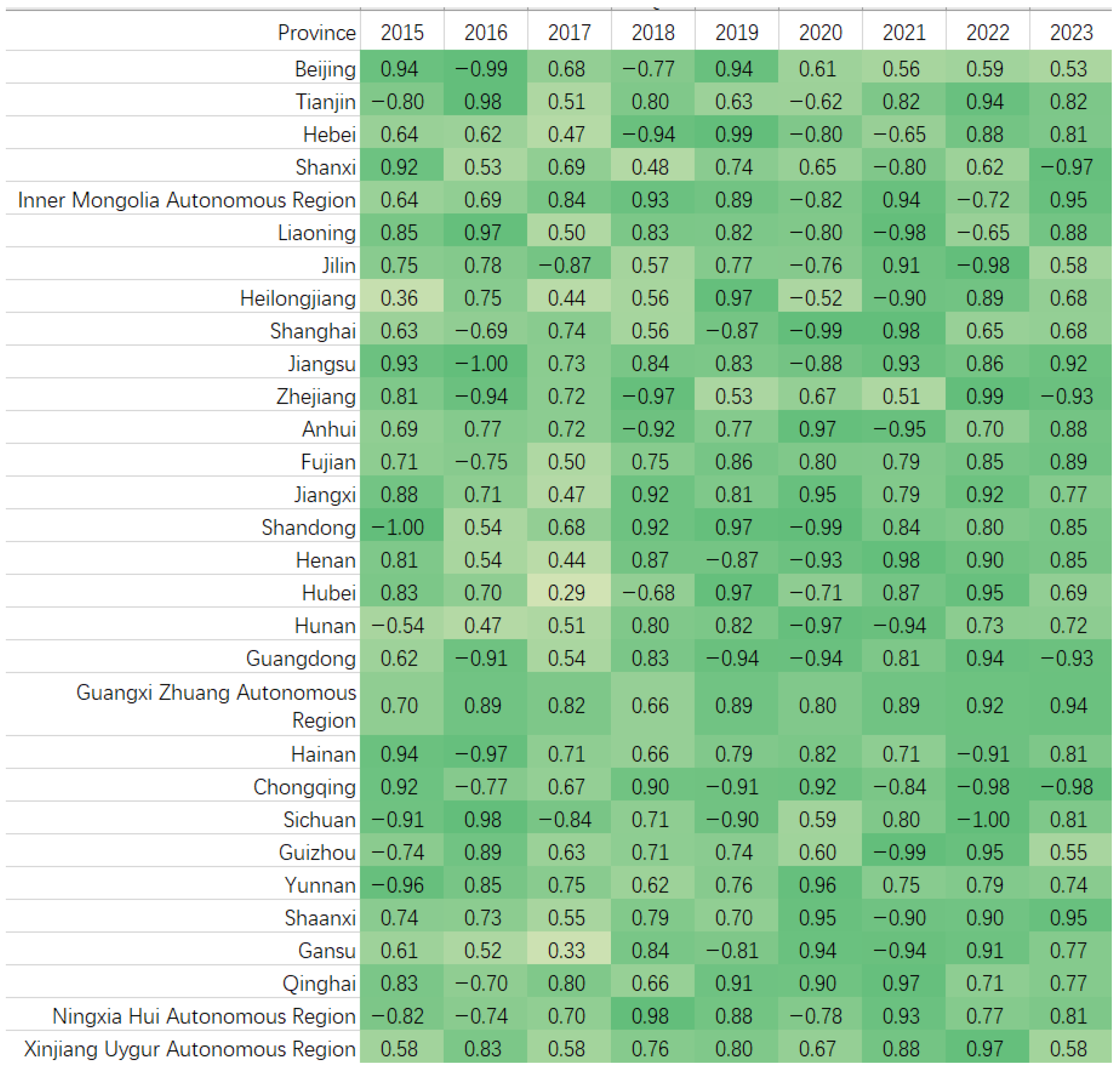

Based on the improved coupling-coordination model, year-on-year growth rates of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization for 30 provinces during 2015–2023 are used to measure coordination in development speed. The results are shown in

Figure 5 (heat map). The absolute value indicates the level of coordination: the closer to 1, the darker the color and the higher the coordination; the closer to 0, the lighter the color and the lower the coordination. The sign shows the leading side: a positive value means new-type urbanization grows faster than rural revitalization; a negative value means rural revitalization grows faster than new-type urbanization.

According to the measurement results, the absolute value of the coordination index in most provinces exceeded 0.5 across different years. Several provinces, such as Jiangsu, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, consistently recorded values close to 0.8–1.0 over multiple years, indicating a generally high level of coordination in the development pace between the two systems. In terms of leadership patterns, many provinces exhibited alternating positive and negative values across years. For instance, Beijing showed new-type urbanization leading in 2015 and 2017–2019, while rural revitalization led in 2016 and 2020, suggesting a dynamic alternation and mutual catch-up process between the two systems. Some provinces, including Guangxi and Xinjiang, maintained positive values in almost all years, reflecting the consistent dominance of new-type urbanization in these regions. Others, such as Yunnan and Gansu, were predominantly positive but experienced isolated years where rural revitalization temporarily surpassed urbanization. Overall, the development speeds of the two systems were well coordinated at the national level. However, clear regional variations and year-to-year fluctuations in leadership were observed, highlighting diverse pathways to urban–rural synergy across different areas.

To facilitate both longitudinal and cross-sectional comparisons, the period 2014–2023 is divided into two phases: 2014–2018 (Phase I) and 2019–2023 (Phase II). Average values of the new-type urbanization index

and the rural revitalization index

for 30 provinces are computed for each phase and compared, as shown in

Figure 6. Coordination of development speeds between the two systems across the two phases for each province is likewise compared, as shown in

Figure 7.

From

Figure 6, clear inter-provincial differences in the coupling coordination degree are observed within each phase. Beijing, Fujian, Hainan, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Zhejiang show markedly higher coordination than most other regions. A longitudinal comparison shows that all provinces record higher coordination in Phase II than in Phase I, but the size of the increase varies. The gaps between the two phases are small in Beijing, Jiangsu, Shanghai, and Tianjin, which suggests that their development levels reached a relatively stable stage earlier. In contrast, the gaps are large in Hainan, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Sichuan, and Qinghai, indicating a faster improvement in coupling coordination during the later period.

Figure 7 presents a comparative analysis of the coordination in development speeds between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization across provinces during the two phases. Most provinces achieved a higher coupling coordination degree in the second phase than in the first, reflecting an overall improvement in the alignment of growth rates between the two systems. In contrast, seven provinces—Beijing, Hainan, Jiangsu, Sichuan, Tianjin, Yunnan, and Zhejiang—exhibited the opposite pattern, with coordination degrees in the first phase not lower than those in the second. This suggests that these regions had established a stronger early foundation for coordinated development, leaving relatively limited room for subsequent improvement. For the remaining provinces, the marked rise in coordination during the second phase indicates progressively optimized development rhythms and a strengthening synergistic acceleration effect between the two systems.

First, there are differences in ranking stability. The leading provinces remain relatively stable in terms of the coordination of development levels between the two systems. In contrast, leadership in development speed coordination changes more easily, showing periodic alternation and catch-up dynamics.

Second, the regional pattern is different. Coastal provinces have clear advantages in the coordination of development levels. However, in terms of speed coordination, some central-western and southwestern provinces improve faster, which suggests a latecomer catch-up pattern.

Third, a mismatch phenomenon exists. Some provinces exhibit “high levels but moderate speed”, suggesting they may have entered a development plateau, requiring structural optimization and resource reallocation to sustain synergistic gains. Others show “moderate levels but high speed”, indicating strong short-term progress but a need to consolidate foundations and maintain outcomes to prevent growth slowdowns.

Overall, from 2019 to 2023, China shows a path of “speed coordination first and level coordination later” between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization. Future policy should promote overall progress while optimizing structure and addressing regional gaps. For regions with high development levels but slow speed, the priority is to improve development quality. For regions with low development levels but fast speed, the focus is to strengthen public services and industrial foundations so that short-term growth can turn into sustained, coordinated development capacity.

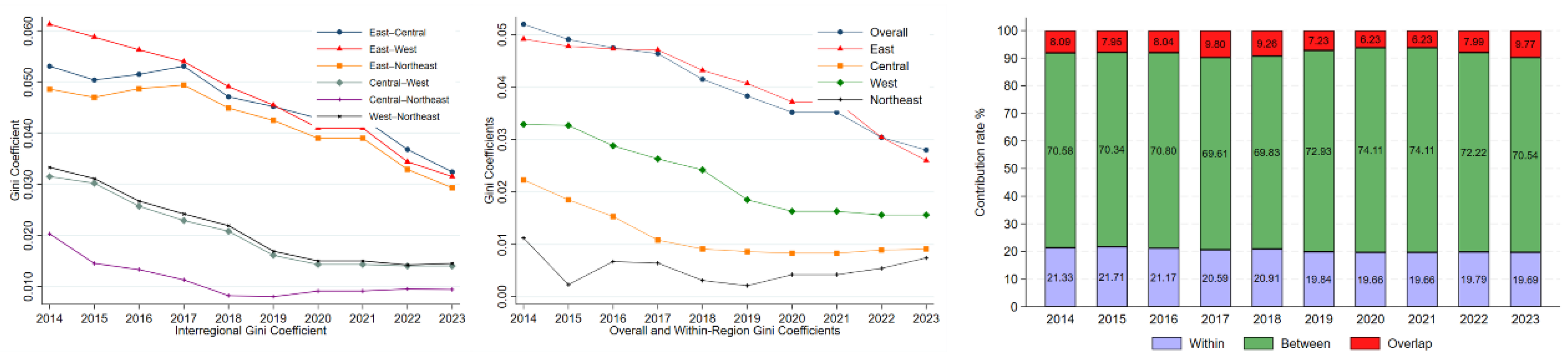

3.3. Analysis of Regional Disparities in the Coupling Coordination Development Between New-Type Urbanization and Rural Revitalization

This study uses the Dagum Gini coefficient to measure regional differences in the coupled and coordinated development of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization across China. The overall disparity is decomposed into within-region and between-region components for the four major economic regions: Eastern, Central, Western, and Northeastern. The contribution of each component to the total gap is assessed. Detailed results are presented in

Figure 8.

The results show that the Dagum Gini coefficient for the coupled and coordinated development of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization ranges from 0.02 to 0.052, with a mean of 0.0404, and exhibits a sustained downward trend at about 6% per year. This indicates a gradual narrowing of interprovincial disparities in the coordination level between the two systems.

From the perspective of within-region differences, the Gini coefficients in all four regions show a downward trend. The East shows the largest internal disparity (mean 0.0406), followed by the West (0.0227), the Central region (0.0119), and the Northeast (0.0053). For decline rates, the Central region decreases by 8.56% per year, which is the largest decline; the West and East decline by 7.19% and 6.18%; the Northeast shows the smallest decline at 4.02%.

The large within-region differences in the East region reflect uneven progress across provinces. Shandong, Beijing, and Jiangsu province have made notable gains in urbanization and rural revitalization due to strong resource endowments, while Hebei and Hainan have lagged behind. In the West, a clear north–south divide is evident: Sichuan and Chongqing in the Southwest benefit from the pull of core cities, whereas Qinghai and the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region in the Northwest face slower growth, because of the lower urbanization quality and infrastructure gaps. The Central and Northeast show smaller internal differences, indicating greater similarity in development levels among provinces within these regions.

In terms of interregional disparities, the gap between the East and the other regions is the most pronounced. The mean interregional Dagum Gini coefficient between the East and the West is 0.0473, between the East and the Central is 0.0455, and between the East and the Northeast is 0.0421. The remaining gaps, from high to low, are West-Northeast (0.0213), West-Central (0.0204), and Central-Northeast (0.0113). All interregional differences show a downward trend, with average annual declines from 4.8% to 7.97%.

The formation of interregional disparities mainly reflects the East’s first-mover advantages in the urbanization process, infrastructure development, and factor allocation. Although national policies promote regional coordination, the East still holds a clear edge in policy resources and financial investment.

In terms of sources of disparity, interregional differences are the dominant contributor, with an average contribution of 71.51%. This indicates that uneven development among the four major economic regions is the core driver of national variation in the coupled and coordinated development of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization. The contribution of intraregional differences is relatively stable, with a mean of 20.43%. The contribution of overlapping component is the lowest, remaining between 8% and 10%, which points to a “club convergence” within the four major regions.

3.4. Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Coupling Coordination Development Between New-Type Urbanization and Rural Revitalization

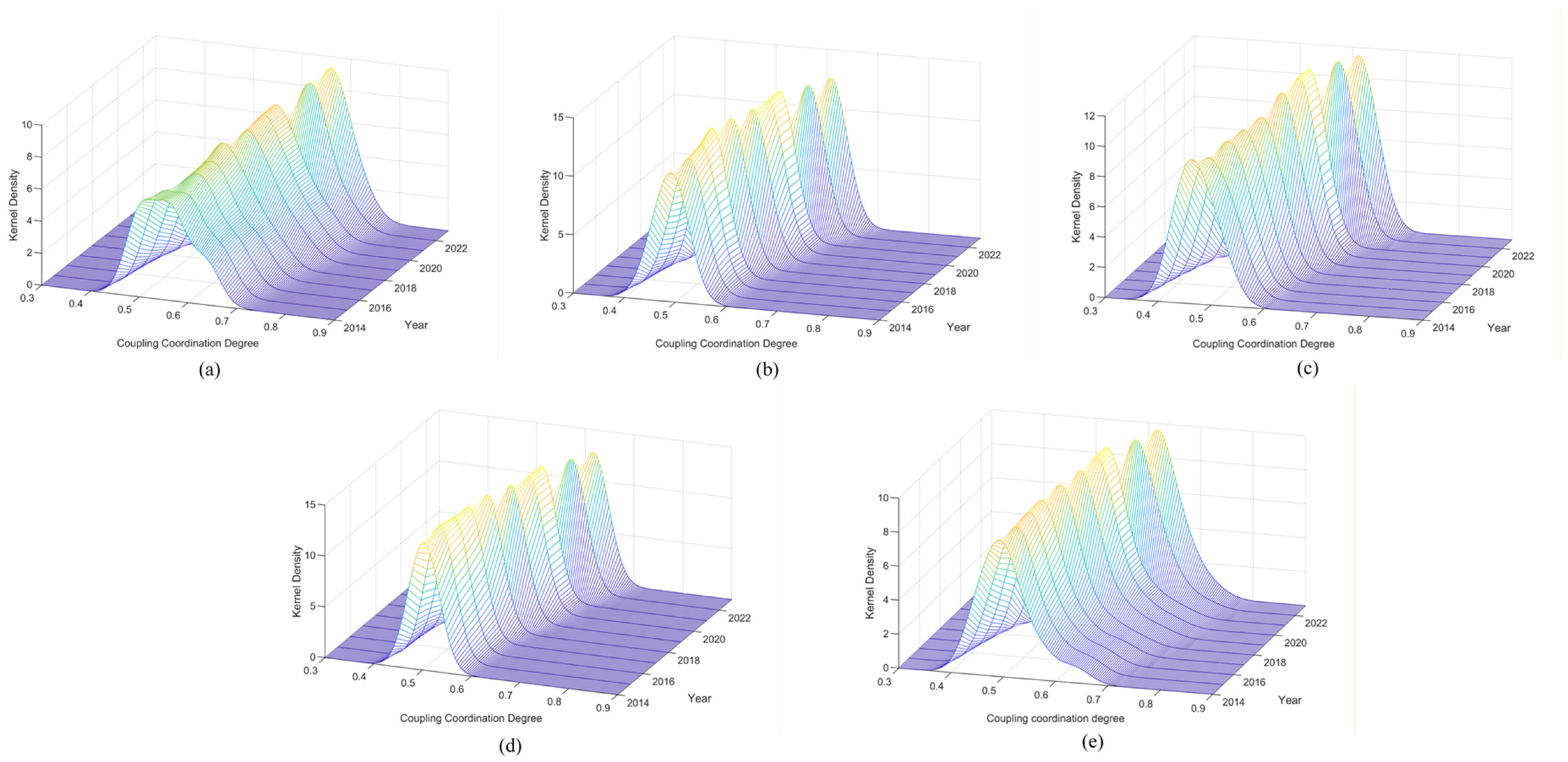

This study applies kernel density estimation to analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of the coupled and coordinated development between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization in China. Kernel density estimation constructs a smooth density curve to show distributional location, concentration, and shape changes, and serves as an effective tool to depict spatial differences and their dynamics. Using MATLAB R2024a, three-dimensional kernel density estimation is conducted for the national sample and for the four major economic regions. The results are interpreted with a focus on the position of the curves, their overall tendency, and their extent.

Figure 9a–d shows the kernel density distributions for China’s four major economic regions: the East, Central, West, and Northeast. These regions share some common trends, but each one also has its own distinct features.

The main peaks of the density curves in all four regions moved to the right. The Eastern region had the most noticeable shift, which means it achieved the greatest progress in coordinating new-type urbanization with rural revitalization. Specifically, the main peaks for the Central, Western, and Northeast regions mostly fall between 0.4 and 0.6. By comparison, the Eastern region’s peak falls within the 0.5 to 0.7 range. This pattern confirms that the Eastern region maintains a generally higher level of development overall.

The distribution shapes evolved differently across regions. In the Eastern region, the curve changed from a low and wide shape to a steep and narrow one. This means that differences within the region first grew larger and then became smaller. In the Central and Western regions, the main peaks kept getting higher. This shows that provinces in these areas are becoming more similar in their development levels. The Northeast region maintained a relatively stable peak height. We can see from this that the internal disparities within the Northeast changed very little over time.

When examining distribution features, all regions except the Eastern one show only one clear peak without heavy tails. This pattern means the Central, Western, and Northeast regions maintained fairly similar and stable coordination levels internally. The Eastern region was different. It initially displayed a second smaller peak to the right of the main one. Over time, this smaller peak gradually joined with the main peak. This change shows that the region moved from having uneven development to a more balanced pattern.

Figure 9e presents the three-dimensional kernel density distribution of the coupling coordination development between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization at the national level, revealing three main characteristics. The density curve’s main peak shows a consistent rightward shift over the study period. This movement points to a clear upward trend in the overall coordination level. At the same time, the main peak is growing taller, indicating that coordination levels across provinces are becoming more alike. This pattern reflects a convergence in regional development. Although no multi-peak structure appears, the distribution does feature a tail extending to the right. This reveals that certain regions performed noticeably better than the national average. As time passed, this tail gradually shortened. These changes together demonstrate not only broad improvement in coordination but also a reduction in gaps between regions.

3.5. Analysis of Influencing Factors in the Coupling Coordination Development Between New-Type Urbanization and Rural Revitalization

This study applies the geographical detector to examine how different factors influence the coupled and coordinated development level of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization. The coupling coordination degree serves as the dependent variable. Selected indicators serve as independent variables. The factor detector and interaction detector are used to identify key drivers of the coupling coordination degree and their interaction mechanisms.

Independent variables are chosen at two levels. For internal drivers, five dimensions of new-type urbanization are included: economic development, social development, spatial structure, green ecology, and innovation and digitalization. Five dimensions of rural revitalization are also included: thriving businesses, pleasant living environment, social etiquette and civility, effective governance, and prosperity. For external drivers, four indicators are selected: proportion of expenditure on urban and rural community affairs, per capita postal and express delivery volume, per capita real estate development investment, and digital financial inclusion index. These four external drivers are selected for two main reasons. First, they correspond to key policy levers-public spending, logistics and e-commerce networks, construction and land development, and digital financial services-and thus capture important external conditions that shape factor flows and spatial patterns between urban and rural areas. Second, they are conceptually complementary to the internal dimensions already included in the two composite indices, rather than simple duplicates of existing indicators. They help explain differences in coupling coordination from the perspective of “institutional and enabling conditions”. At the same time, these variables are closely aligned with China’s territorial spatial planning priorities, such as equalization of public services, layout of transport and logistics corridors, control of construction land, and the building of a “digital China”.

3.5.1. Nationwide Full-Period Analysis of Influencing Factors

- 1.

Factor detection: identifying key drivers

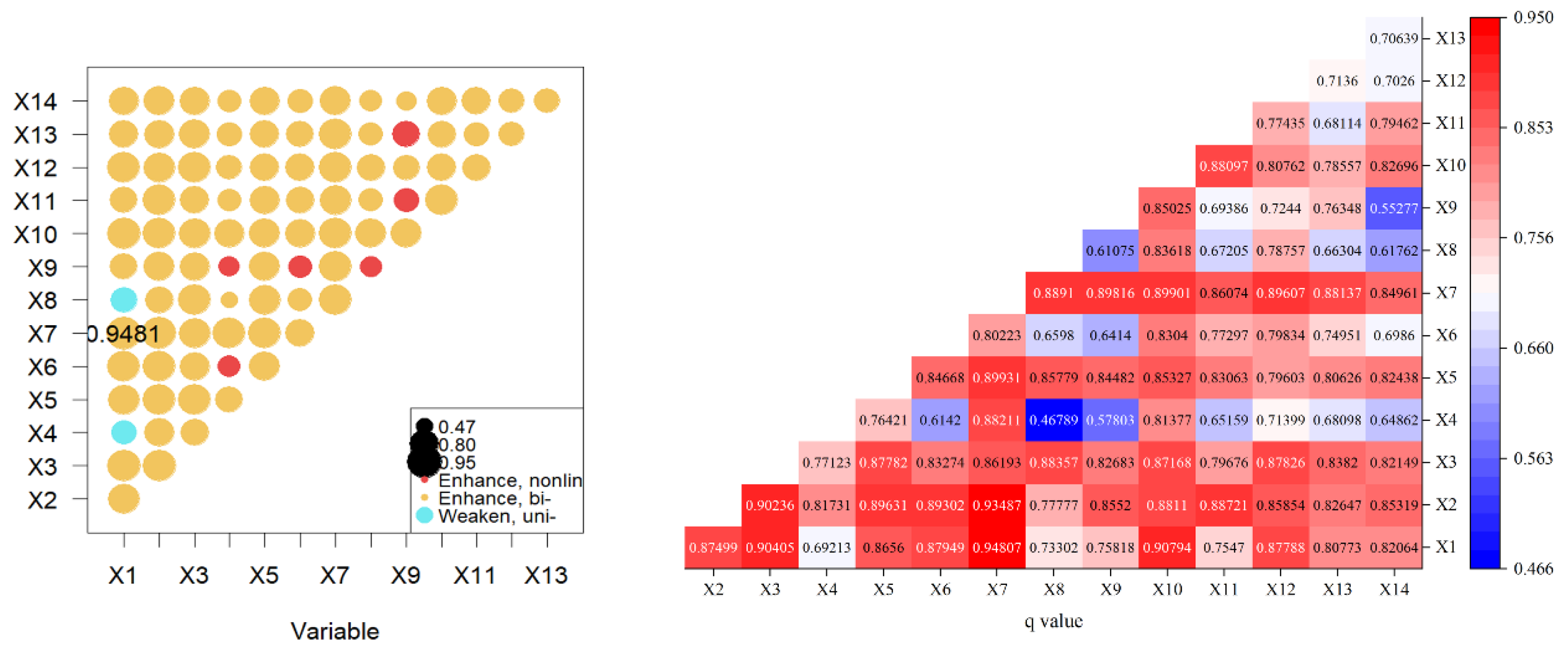

Using the geographical detector, the drivers of the coupled and coordinated development of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization over the full study period are identified. The results are shown in

Table 7.

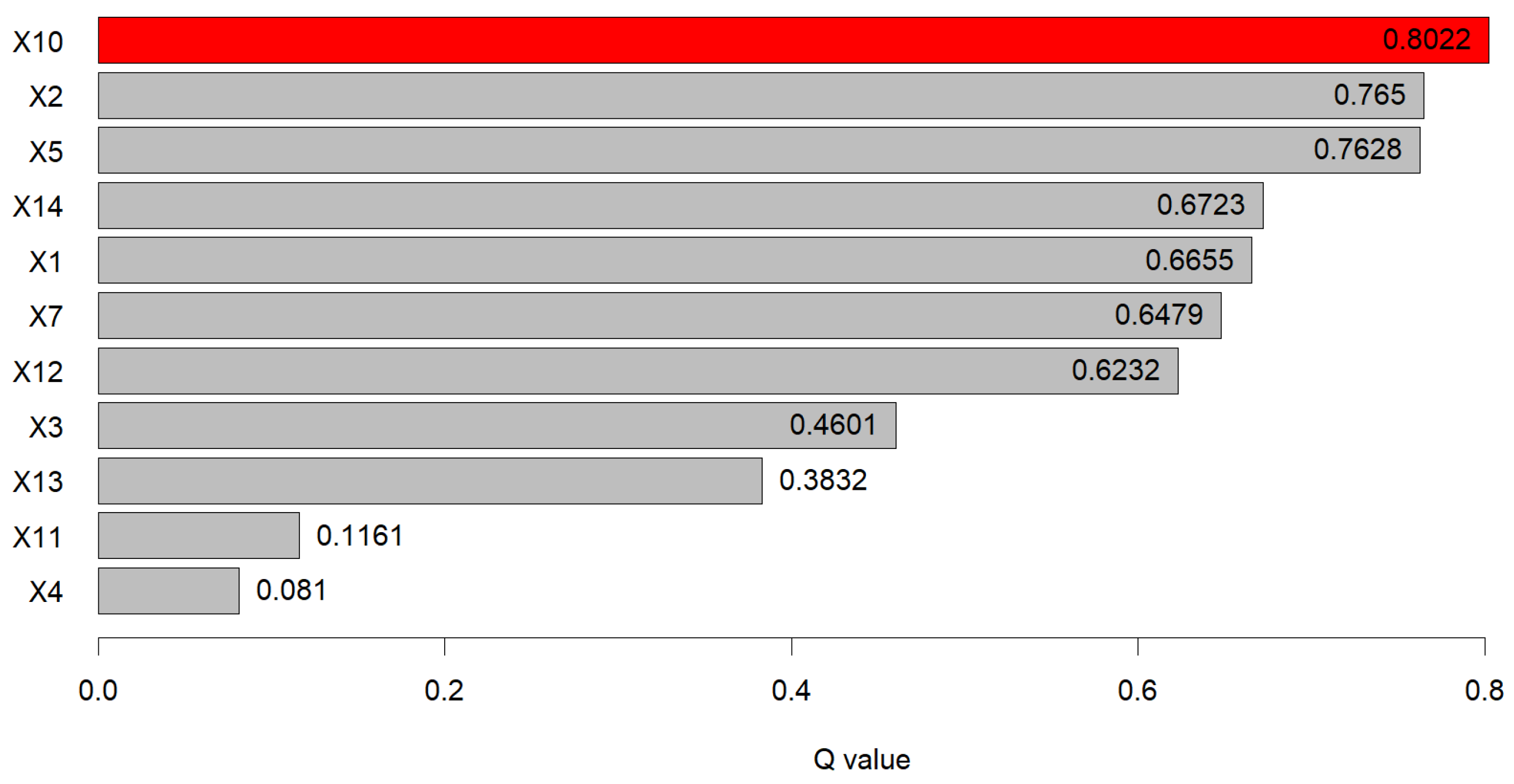

The factor detector results show clear stratification in the explanatory power (q values) of the drivers. This pattern indicates structural differences in how factors from different dimensions promote the coupled and coordinated development of the two systems, as shown in

Figure 10.

Among the internal drivers, prosperity (X10) shows the strongest independent explanatory power (q = 0.802), well above the other variables, indicating that improvements in household income and living standards are key to advancing the coupled and coordinated development of the two systems (SDGs1/8). Social development (X2, q = 0.765) and innovation and digitalization (X5, q = 0.763) also exert significant influence, highlighting the supporting roles of public service provision, gains in education and health, and the use of digital infrastructure and data factors (SDGs3/4/9). In addition, economic development (X1, q = 0.666) and a pleasant living environment (X7, q = 0.648) are important drivers, reflecting the essential contributions of economic growth and ecological improvements to urban–rural coordination (SDGs8/11).

For the external drivers, per capita postal and express delivery volume (X12, q = 0.623) and digital financial inclusion index (X14, q = 0.672) show strong and significant explanatory power. This indicates that financial accessibility and logistics connectivity help strengthen urban–rural linkages and factor flows, thus providing external channels for coordinated development (SDGs8/9/10).

By contrast, several factors have weaker explanatory power. Spatial structure (X3, q = 0.460) and the proportion of expenditure on urban and rural community affairs (X11, q = 0.116) show limited independent effects. Green ecology (X4, q = 0.081) has a modest effect, and thriving businesses (X6), social etiquette and civility (X8), and effective governance (X9) do not pass the significance test. This suggests that, at the national level, these factors have not yet formed systematic independent drivers and may rely more on combinations with other conditions or on region-specific contexts.

- 2.

Interaction Detection: Unveiling the Mechanisms of Interactive Effects among Factors

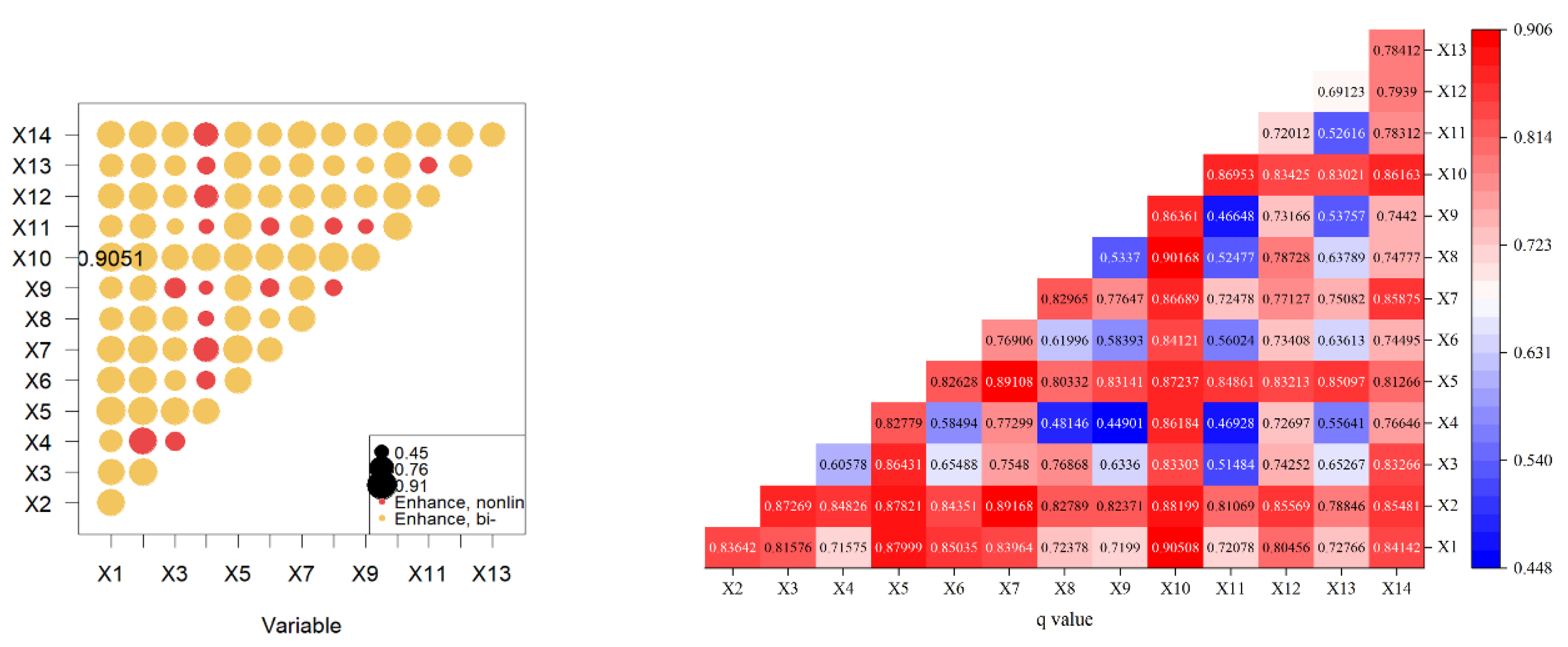

The interaction detector results show that factors consistently reinforce each other, as shown in

Figure 11. For any two factors, their combined ability to explain the outcome is stronger than any single factor alone. All observed interactions were enhancing types, with no independent or weakening effects found. This consistent pattern demonstrates that the coordination between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization essentially functions as a system where multiple factors work together.

Prosperity (X10) plays a key hub role in interaction effects. When it interacts with social development (X2) and innovation and digitalization (X5), the q-values reach 0.882 and 0.872, showing clear synergistic effects. This shows that rising living standards can activate and strengthen the contributions of social structures and digital-intelligence factors to coordinated development. Additionally, strong reinforcing effects are found between prosperity and economic development (X1, q = 0.905), a pleasant living environment (X7, q = 0.867), and per capita postal and express delivery volume (X12, q = 0.834). These results together confirm that prosperity holds a central position in advancing urban–rural coordination.

Several variables that showed weaker individual effects in the factor detector still play important roles when interacting with core drivers. These include spatial structure, effective governance, green ecology, and social etiquette and civility. When these factors work together with stronger ones like prosperity and social development, they create clear strengthening effects. For instance, the interaction between prosperity (X10) and effective governance (X9) reaches a q-value of 0.864. This demonstrates that although these factors have a limited impact alone, they can still act as important catalysts or channels within the overall system. In doing so, they support core drivers in achieving more efficient resource allocation and institutional integration.

3.5.2. Period-Specific Analysis of Influencing Factors

- 1.

Factor detection: identifying key drivers

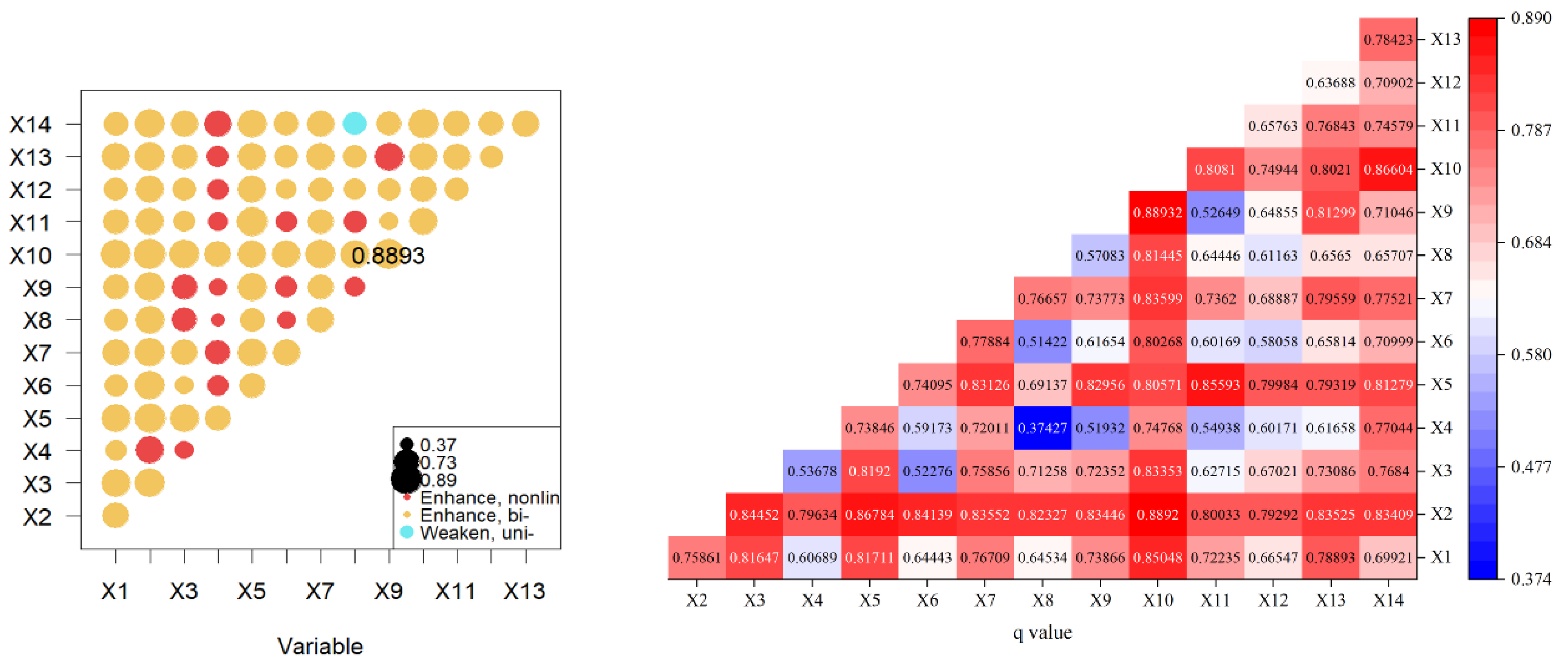

Based on period-specific factor detector results, the driving mechanism of the coupling coordination degree shows clear stage heterogeneity. The factor influence (q values) and statistical significance (

p values) are not always aligned, indicating that the strength and stability of drivers vary across periods. Detailed results are reported in

Table 8.

- (i)

2014–2017: Initial formation of a multi-driver pattern

During this stage, seven factors passed the significance test (

p < 0.05). Ranked by explanatory power (q-value) in descending order, they are prosperity (X10) > pleasant living environment (X7) > innovation and digitalization (X5) > social development (X2) > spatial structure (X3) > digital financial inclusion (X14) > share of expenditure on urban and rural community affairs (X11), as shown in

Figure 12. Prosperity (q = 0.773) and a pleasant living environment (q = 0.750) show the strongest effects, indicating that rising household living standards and improvements in the ecological environment played foundational roles in advancing urban–rural coordination. Innovation and digitalization (q = 0.747) and social development (q = 0.743) follow closely, suggesting that technological progress and social service improvements were important drivers in this period.

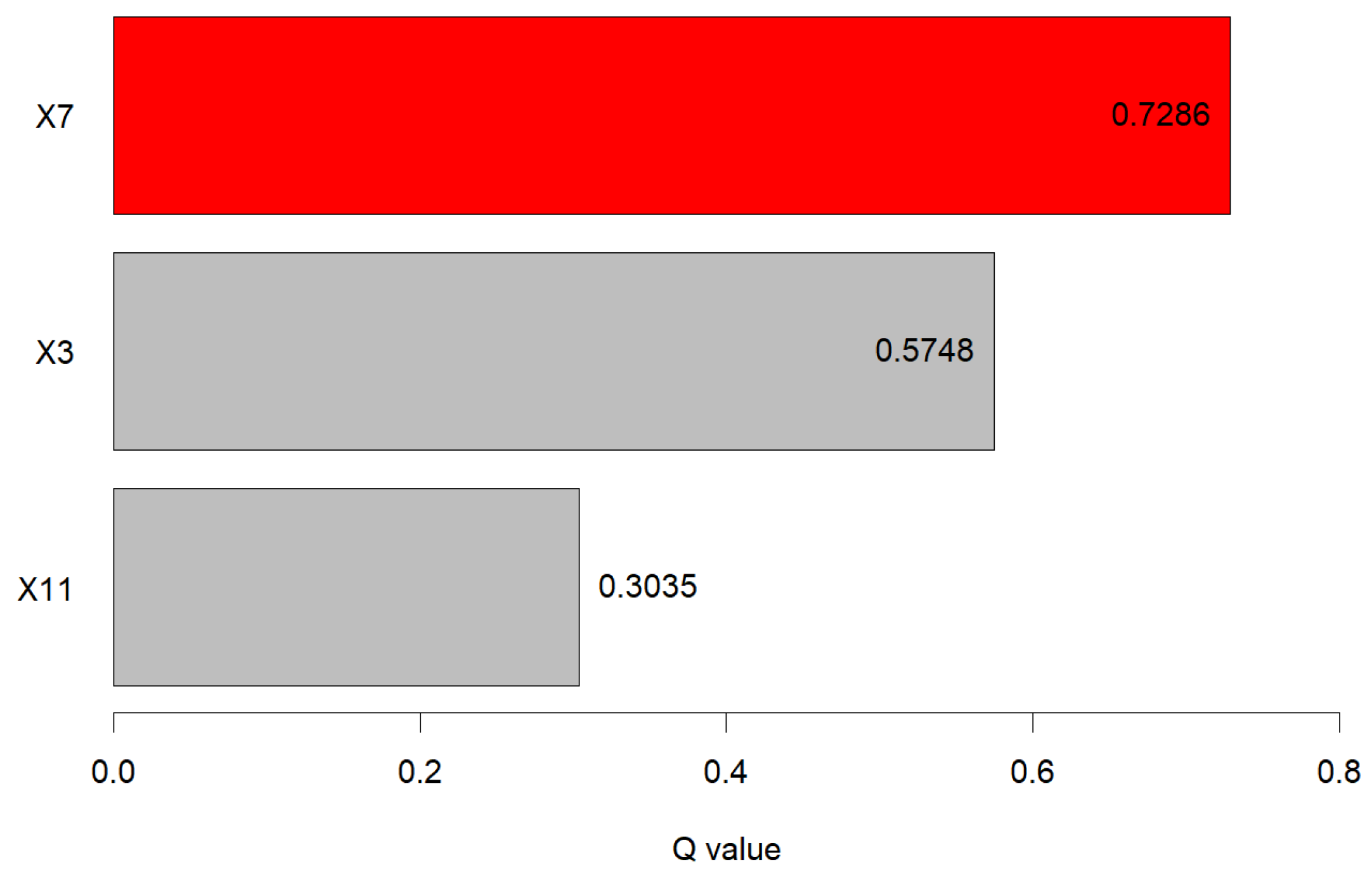

- (ii)

2018–2020: Optimization of the driver structure and convergence of some factor effects

In this stage, the number of significant drivers falls to three, ordered by explanatory power as follows: pleasant living environment (X7) > spatial structure (X3) > proportion of expenditure on urban and rural community affairs (X11), as shown in

Figure 13. Notably, the explanatory power of social development continues to rise (q = 0.812), while its statistical significance weakens (

p = 0.062), reaching a marginal level. The explanatory power of spatial structure declines (q = 0.575). Digital financial inclusion index and innovation and digitalization, which were significant in the previous stage, retain moderate explanatory power (q = 0.747 and q = 0.611, respectively) but lose statistical significance, indicating a shift from explicit to latent effects.

- (iii)

2021–2023: Emergence of new-type drivers and restructuring of the driver system

In this stage, the number of significant factors rises to six. The ranking by explanatory power is prosperity (X10) > social development (X2) > pleasant living environment (X7) > Per capita real estate development investment (X13) > Proportion of expenditure on urban and rural community affairs (X11) > effective governance (X9), as shown in

Figure 14. Prosperity (q = 0.704) and social development regain strong and significant explanatory power and re-emerge as core drivers. Of particular note, effective governance (X9) and per capita real estate development investment (X13) appear as new significant drivers for the first time. Although their explanatory power is moderate (q = 0.288 and q = 0.496, respectively), their emergence signals an expansion of the driver base toward governance performance and investment structure.

Synthesizing the three stages, prosperity, a pleasant living environment, and social development emerge as stable cross-period drivers, with consistently high explanatory power (q > 0.6). Proportion of expenditure on urban and rural community affairs remains statistically significant in all three periods, indicating a sustained supporting role. By contrast, the effects of spatial structure and innovation and digitalization converge over time. Going forward, priority should be given to prosperity and a pleasant living environment as core dimensions, while strengthening governance effectiveness and optimizing the urban–rural investment structure to promote the deep integration and coordinated development of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization.

- 2.

Interaction Detection

- (i)

2014–2017: Early emergence of coordination

The interaction results for 2014–2017 indicate that relationships among factors were dominated by bivariate enhancement. The strongest pairs were economic development and pleasant living environment (X1 × X7, q = 0.948), social development and pleasant living environment (X2 × X7, 0.935), and economic development and prosperity (X1 × X10, 0.908). These findings suggest that the pleasant living environment (X7) functioned as a core node in the network. It showed strong linkages with economic, social, and livelihood dimensions, as illustrated in

Figure 15.

The interaction results also identify several cases of nonlinear enhancement, including green ecology and thriving businesses (X4 × X6), green ecology and effective governance (X4 × X9), and social etiquette and civility and effective governance (X8 × X9). This pattern means that when progress in ecology, industry, governance, and civility advances together, their joint effect exceeds the simple sum of individual contributions. In other words, the combined explanatory power is greater than additive effects.

At the same time, a few pairs show univariate weakening, such as economic development and green ecology (X1 × X4) and economic development and social etiquette and civility (X1 × X8). These results warn that if economic growth is not aligned with ecological protection or improvements in social norms, the overall coordination effect will be reduced.

- (ii)

2018–2020: Coordination and mismatch under external shocks

During this period, factor interactions show a mixed pattern of enhancement and weakening. Overall, bivariate enhancement remains dominant, as illustrated in

Figure 16. Social development (X2) and prosperity (X10) are the most stable and influential hubs in the network. They form a strong linkage with each other (X2 × X10, q = 0.901) and connect strongly with other factors, including spatial structure (X2 × X3, q = 0.928) and innovation and digitalization (X2 × X5, q = 0.898). Together, these links outline a coordination framework centered on social-livelihood-spatial-innovation connections.

Several cases of nonlinear enhancement show how different factors work together in the system. Specifically, when spatial structure interacts with green ecology (X3 × X4) and with effective governance (X3 × X9), the combined effects are greater than simply adding up their individual contributions. This finding means that coordinating spatial planning with ecological protection and governance arrangements creates significantly better outcomes.

The results also reveal some systemic mismatches. When digital financial inclusion (X14) interacts with key factors like innovation and digitalization (X5), thriving businesses (X6), and prosperity (X10), the effects show a weakening pattern. This suggests that in the early stages, digital finance does not yet work well with traditional development factors. Furthermore, the interactions between economic development (X1) and green ecology (X4), as well as between social development (X2) and green ecology (X4), also show weakening effects. This indicates that we still need to find better ways to make economic growth and social progress align with ecological protection.

- (iii)

2021–2023: Formation of a networked coordination pattern

During this period, the interaction results identify two clear coordination paths. First, social development (X2) and prosperity (X10) serve as hubs for the whole system, as seen in

Figure 17. These two factors show strong enhancing effects with most other core factors. These include innovation and digitalization, thriving businesses, spatial structure, effective governance, and digital financial inclusion. This pattern shows that a well-developed coordination network has formed, centered on social and livelihood connections and extending across multiple areas.

Second, another important finding involves the role of green ecology (X4). While its individual effect is limited, its interactions with industry, spatial planning, digital finance, governance performance, and fiscal inputs mainly show nonlinear enhancement. This means ecological protection is no longer a separate constraint. Instead, by deeply connecting with other systems, it now works as a catalyst that improves overall development outcomes.

Furthermore, spatial structure (X3), social etiquette and civility (X8), and effective governance (X9) create consistent chains of nonlinear enhancement. This highlights the importance of coordinating spatial planning with governance systems. Another notable change involves digital financial inclusion (X14). Compared to the earlier period, its interactions have shifted from mainly weakening to mostly enhancing. After going through an initial adjustment period, digital finance has now become part of the core development process and works effectively with other development factors.

4. Discussion

Building on the analyses in this study, we systematically explain the interaction mechanism of the coupled and coordinated development between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization, examine in depth the influence of institutional arrangements, digital factors, and population flows on this coordination process, and finally conduct a comparative analysis drawing on international experience.

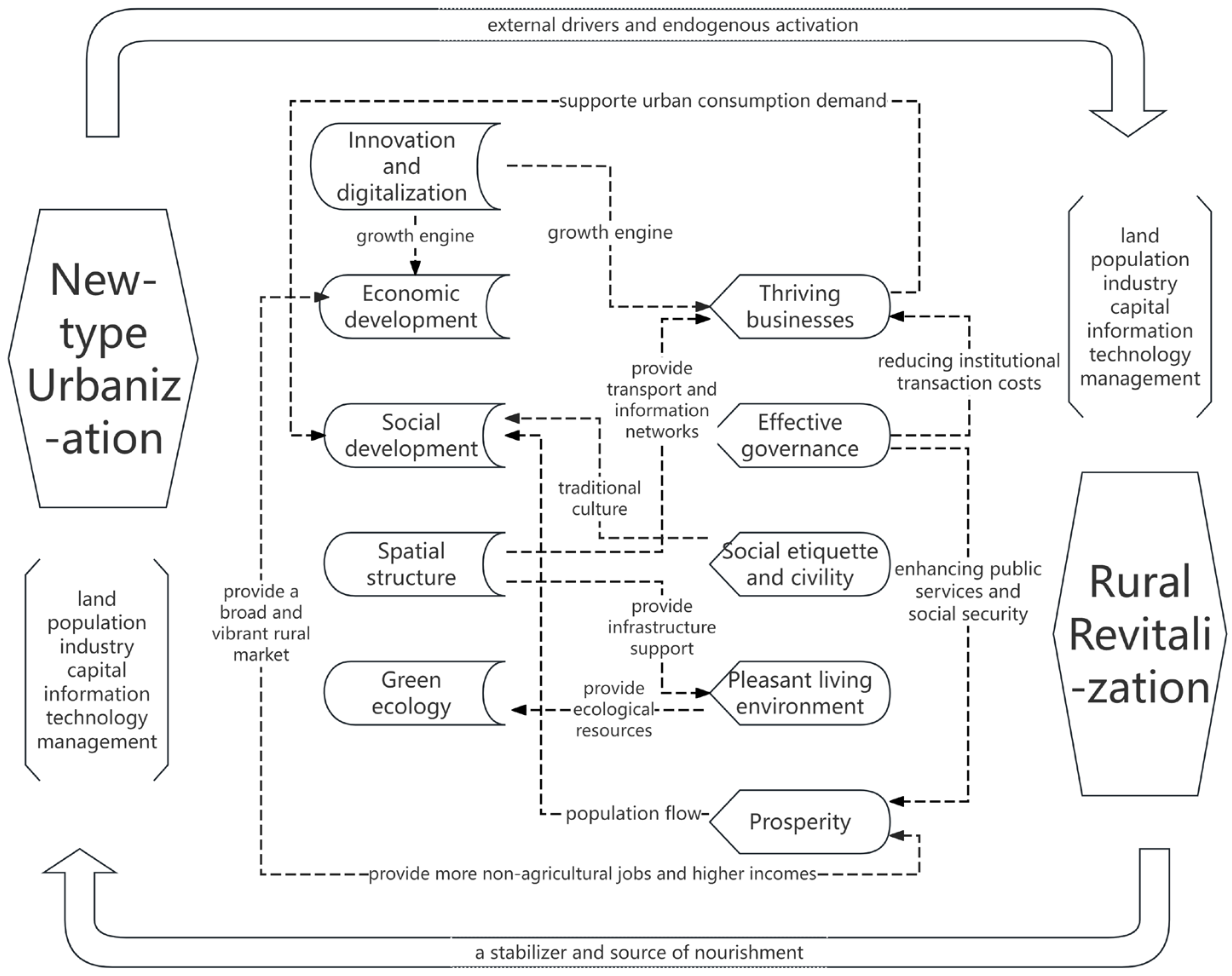

4.1. Interaction Mechanism of the Coupled and Coordinated Development Between New-Type Urbanization and Rural Revitalization

Based on the above findings, the coupled and coordinated development between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization is a complex system. It works through key transmission paths that support two-way interaction of factors and functions, and it relies on basic support systems and macro-level regulation. The internal logic can be summarized as four linked subsystems. As shown in

Figure 18.

The core driving system. Innovation and digitalization act as a common engine across urban and rural areas. They push industrial upgrading and higher factor efficiency in cities, and they also support new rural industries such as e-commerce, tourism, and agricultural processing. In this way, they raise the development level of both economic growth in cities and thriving businesses in the countryside.

The two-way transmission system. Economic development creates more non-agricultural jobs and higher incomes for rural residents, which supports orderly population flows and faster social development. Spatial structure extends transport and information networks to rural areas, lowers logistics costs, enlarges markets, and supports a better living environment. At the same time, thriving rural industries supply cities with agricultural and ecological products, good rural ecosystems provide water and ecological buffers, rural culture enriches urban cultural life, and higher rural incomes create new demand for urban goods and services.

The basic support system. Green ecology in cities and a pleasant living environment in rural areas together build an urban–rural ecological security pattern. Compact urban development reduces pressure on rural ecological space, while good rural ecology improves overall livability. The spatial structure dimension provides an orderly physical framework for the layout of industry, population, and public services, and helps factor flows and functional linkages operate within a reasonable spatial pattern.

The stabilization and regulation system. Effective governance uses integrated public services, social security, and dispute resolution to reduce social risks and to stabilize factor flows and structural change. The interaction between rural social etiquette and civility and modern urban civic values helps form an open and trust-based culture. This lowers social and psychological resistance and provides social capital to support long-term coupled and coordinated development.

4.2. Discussion of Institutional, Digital, and Spatial Mechanisms

From an institutional perspective, the coupled and coordinated process identified in this study is not driven only by economic and technological factors. It is also strongly shaped by institutional arrangements. The household registration system, land institutions, the fiscal system, and territorial spatial planning all play an important role in deciding whether factors can move smoothly between urban and rural areas. For example, the separation of urban and rural public services and the rules for transfer payments affect migrants’ willingness to settle in cities for the long term. These rules also influence the capacity of counties to receive industries and population. Future research could include these institutional variables in the analytical framework and more carefully identify how different institutional combinations lead to different coupling and coordination paths between new-type urbanization and rural revitalization.

Digitalization is identified in this study as an important driving force, but its potential negative effects also need attention. On the one hand, digital inclusive finance and express delivery networks can clearly reduce transaction costs, enlarge “long-tail” markets, and promote a new matching of urban and rural factors. On the other hand, digital infrastructure and skills are not evenly distributed. Less developed areas, older people, and low-education groups are more likely to be left out of the new round of digital dividends, which may create a new “digital divide.” Platform economies and algorithm-based pricing may also squeeze the survival space of small actors and strengthen spatial concentration rather than narrow gaps. Therefore, while promoting digital villages and smart cities, it is necessary to use tools such as digital literacy training, age-friendly design, and platform regulation to prevent digitalization from amplifying existing inequalities.