Study on the Changes of Agritourism Landscape Pattern in Southwest China’s Mountainous Area from a Landscape Function Perspective: A Case Study of Hanyuan County, Sichuan Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source and Preprocessing

2.2.1. Landscape Classification of Agritourism Based on Landscape Function Perspective

2.2.2. POI Data Acquisition and Processing

2.2.3. Multisource Supporting Data

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Landscape Pattern Differentiation Characteristics Across Terrain Gradients

2.3.2. Driving Mechanism Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Agritourism Landscape Types

3.1.1. Temporal Changes in Landscape Types

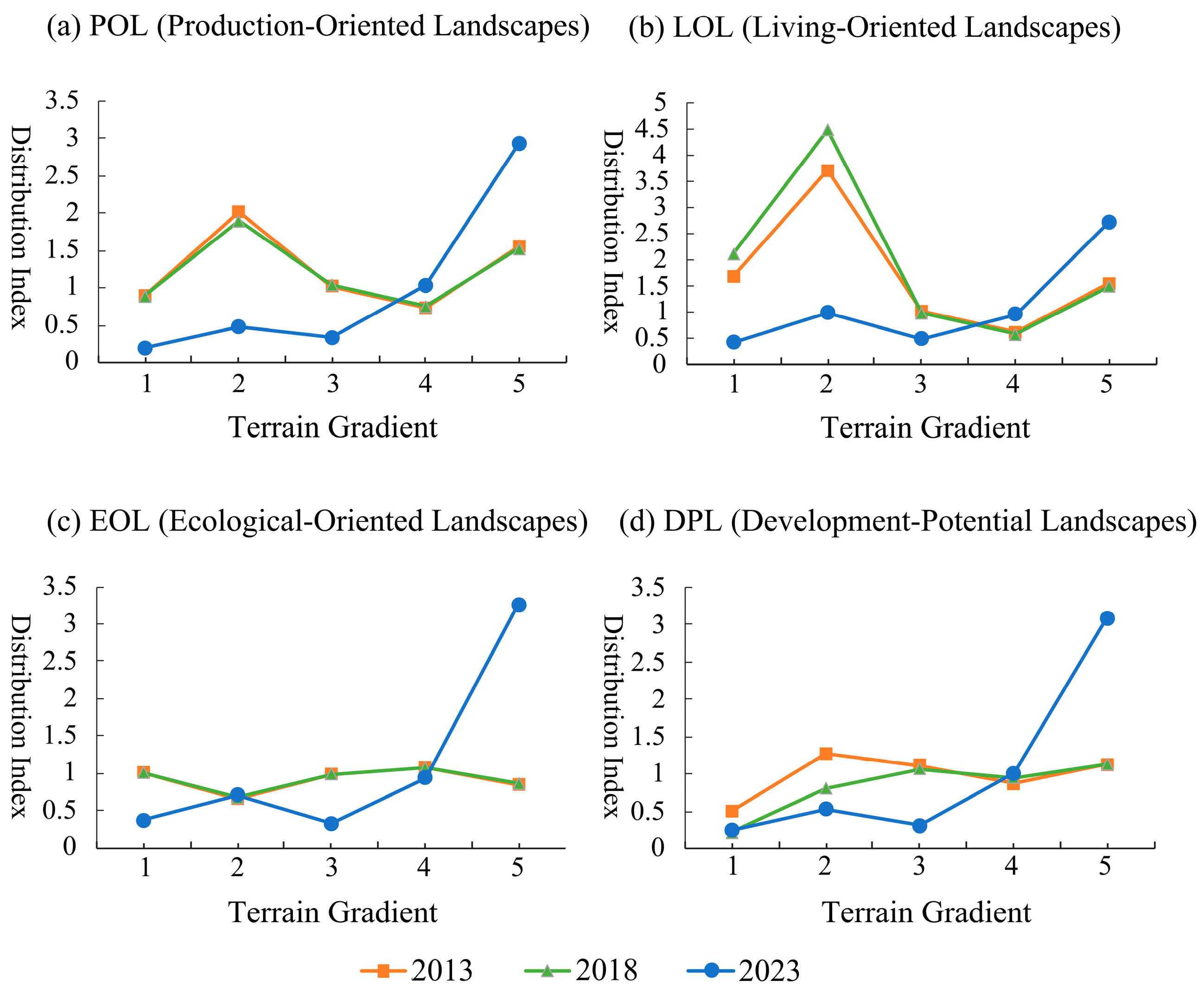

3.1.2. Spatial Distribution Along Terrain Gradients

3.2. Key Factors Associated with Landscape Types

3.2.1. Factors Associated with Production-Oriented Landscapes (POLs)

3.2.2. Factors Associated with Living-Oriented Landscapes (LOLs)

3.2.3. Factors Associated with Ecological-Oriented Landscapes (EOLs)

3.2.4. Factors Associated with Development-Potential Landscapes (DPLs)

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatiotemporal Changes in Agritourism Landscape Pattern

4.2. Driving Mechanisms Underlying Landscape Changes

4.3. Implications for Sustainable Agritourism Landscape Management

4.3.1. Zoned Optimization Based on Landscape Functions and Terrain Gradients

4.3.2. Policy Guidance and Technological Intervention

4.4. Limitations and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bruno, M.; Daniel, V.; Rolf, W. Comments: A new typology for mountains and other relief classes: An application to global continental water resources and population distribution. Mt. Res. Dev. 2001, 21, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tappeiner, U.; Tasser, E. A transnational perspective of global and regional ecosystem service flows from and to mountain regions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bičík, I.; Jeleček, L.; Štěpánek, V. Land-use changes and their social driving forces in Czechia in the 19th and 20th centuries. Land Use Policy 2001, 18, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Ye, C.; Cai, Y.; Xing, X.; Chen, Q. The impact of rural out-migration on land use transition in China: Past, present and trend. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godde, P.M.; Price, M.F.; Zimmerman, F.M.; Ebrary, I. Tourism and Development in Mountain Regions; CABI Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal, S.K.; Chipeniuk, R. Mountain tourism: Toward a conceptual framework. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 7, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, R.; Knowles, N.; Pöll, K.; Rutty, M. Impacts of climate change on mountain tourism: A review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 1984–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches—Towards a new generation concept? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dax, T.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y. Agritourism initiatives in the context of continuous out-migration: Comparative perspectives for the Alps and Chinese mountain regions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X.; He, J.; Wang, H. Identification of important terraced visual landscapes based on a sensitivity-subjectivity preference matrix for agricultural cultural heritage in the Southwestern China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.I.; Sánchez-Martín, J. Agricultural landscapes as a basis for promoting agritourism in Cross-Border Iberian Regions. Agriculture 2022, 12, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorner, B.; Lertzman, K.; Fall, J. Landscape pattern in topographically complex landscapes: Issues and techniques for analysis. Landsc. Ecol. 2002, 17, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J. Landscape pattern and sustainability of a 1300-year-old agricultural landscape in subtropical mountain areas, Southwestern China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2013, 20, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Fan, W.; Stott, P. Effect of terrain on landscape patterns and ecological effects by a gradient-based RS and GIS analysis. J. For. Res. 2017, 28, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Hu, C.; Li, J. Spatial-temporal driving factors of urban landscape changes in the Karst mountainous regions of Southwest China: A case study in central urban area of Guiyang City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xie, Y.; Li, Y. Transition of rural landscape patterns in Southwest China’s mountainous area: A case study based on the Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Hu, X.; Qiu, S.; Hu, Y.; Meersmans, J.; Liu, Y. Multifunctional landscapes identification and associated development zoning in mountainous area. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 660, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, R. Function-analysis and valuation as a tool to assess land use conflicts in planning for sustainable, multi-functional landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Zeng, H.; Chang, R.; Bai, X. Understanding relationships between landscape multifunctionality and land-use change across spatiotemporal characteristics: Implications for supporting landscape management decisions. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; D’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C. Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 1–412. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumans, R.M.J. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MA. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; He, T.; Gao, Z. Landscape ecological risk assessment and driving factor analysis in southwest China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, S.; Zhang, L.; Pang, J. The spatial–temporal evolution of the trade-offs and synergy between the suburban rural landscape’s production–living–ecological functions: A case study of Jiashan in the Yangtze River Delta eco-green integrated development demonstration zone, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Du, C. Plant landscape characteristics of mountain traditional villages under cultural ecology: A case study of Pilin village. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.; Yang, F.; Huang, D.; Luo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wen, C. Land-use transformation and landscape ecological risk assessment in the Three Gorges Reservoir Region based on the “production–living–ecological space” perspective. Land 2022, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ye, Y.; Fang, X. Reconstruction of cropland cover in topographically complex areas: The case of Sichuan Province, China, from 1671 to 2019. Glob. Planet. Change 2024, 236, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Xiao, Y.; Polasky, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Rao, E.; et al. Improvements in ecosystem services from investments in natural capital. Science 2016, 352, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striving with Resilience Towards the Future—A Spotlight on Post-Disaster Recovery and Reconstruction in Hanyuan County After the “4·20” Lushan Strong Earthquake. Available online: https://www.yaan.gov.cn/xinwen/show/052913d4-fa4f-4a4a-b057-96ed547a341c.html (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Notice of the Office of the People’s Government of Hanyuan County on Issuing the Implementation Plan for Key Tasks in the Reform and Development of the County Economy in 2018. Available online: http://www.hanyuan.gov.cn/gongkai/show/20180910093106-078704-00-000.html (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Prioritizing Agriculture and Rural Development to Advance rural Revitalization: Hanyuan County Named 2023 Sichuan Provincial Outstanding Performer in Rural Revitalization. Available online: https://www.yaan.gov.cn/zhangzhe/show/f5824fd9-fa2c-48fd-b6c6-290adc3a3087.html (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- GB/T 21010-2017; Current Land Use Classification. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Milias, V.; Psyllidis, A. Assessing the influence of point-of-interest features on the classification of place categories. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 86, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito, A.; Mancini, S.; Brito, J.; Moreno, J.A. A fuzzy GRASP for the tourist trip design with clustered POIs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 127, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.; Alves, A.; Bento, C. POI mining for land use classification: A case study. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Veloso, M.; Alves, A.; Bento, C.L. Socioeconomic and functional zoning characterization in a city: A clustering approach. Cities 2025, 163, 106023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingseisen, B.; Metternicht, G.; Paulus, G. Geomorphometric landscape analysis using a semi-automated GIS-approach. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2008, 23, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; You, G.; Chen, T.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y. Rural landscape change: The driving forces of land use transformation from 1980 to 2020 in Southern Henan, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déjeant-Pons, M. The European landscape convention. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hwang, S.; Lee, S.; Hwang, H.; Sung, H. Landscape ecological approach to the relationships of land use patterns in watersheds to water quality characteristics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 92, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, Y. Multi-scale analysis of spatially varying relationships between agricultural landscape patterns and urbanization using geographically weighted regression. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 32, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Ma, Q.; Du, C.; Hu, G.; Shang, C. Rapid urbanization in a mountainous landscape: Patterns, drivers, and planning implications. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 2449–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renetzeder, C.; Schindler, S.; Peterseil, J.; Prinz, M.A.; Mücher, S.; Wrbka, T. Can we measure ecological sustainability? Landscape pattern as an indicator for naturalness and land use intensity at regional, national and European level. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tong, X. Spatiotemporal variation of landscape patterns and their spatial determinants in Shanghai, China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 87, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, Q.; Li, B.; Fan, Y.; Fan, H.; Yang, N.; Quan, Y.; Ding, H.; Zhang, Y. Trends and factors influencing the evolution of spatial patterns of cropland toward large-scale agricultural production in China. Land 2024, 13, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yang, Q. Theoretical analysis and empirical research on the driving force of agricultural landscape evolution in mountainous areas—A case study of Shizhu County, China. J. Southwest Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 49, 139–152. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Yan, X. Driving mechanism analysis of landscape pattern change in the lower reach of liaohe river plain based on gis-logistic coupling model. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 7280–7292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, L.; Zhang, W. Impacts of land use change on landscape patterns in mountain human settlement: The case study of Hantai District (Shaanxi, China). J Mt. Sci. 2021, 18, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, W.; Zhu, L.; Li, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, X. Spatial variations of terrain and their impacts on landscape patterns in the transition zone from mountains to plains—A case study of Qihe River Basin in the Taihang Mountains. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2018, 61, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wu, W.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Z. Spatiotemporal changes in landscape patterns in karst mountainous regions based on the optimal landscape scale: A case study of Guiyang City in Guizhou Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, J. Heterogeneous effects of climate change and human activities on annual landscape change in coastal cities of mainland China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zha, P.; Yu, M.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, J.; You, Q.; Xie, X. Landscape pattern evolution and its response to human disturbance in a newly metropolitan area: A case study in Jin-Yi Metropolitan area. Land 2021, 10, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ning, L.; Bai, X. Spatial and temporal changes of human disturbances and their effects on landscape patterns in the Jiangsu coastal zone, China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, Y.; Xia, C.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, B. Coupling responses of landscape pattern to human activity and their drivers in the hinterland of Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 33, e01992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, S.; Wang, R.; Zhang, B.; Liang, X.; Shao, J.A. Transformation of land use and landscape pattern in global mountains: Based on local and regional knowledge. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Li, Y. Spatiotemporal features of farmland scaling and the mechanisms that underlie these changes within the Three Gorges Reservoir area. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Xiang, P.; Wang, H.; Xia, M. Driving mechanisms of the integration of ecological farms and rural tourism: A mixed method study. Agriculture 2025, 15, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Xie, B.; Luo, W. A comparative study on land use/land cover change and topographic gradient effect between mountains and flatlands of Southwest China. Land 2023, 12, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbrechts, L.; Azevedo, J.C.; Verburg, P. Trajectories and drivers signalling the end of agricultural abandonment in Trás-os-Montes, Portugal. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 24, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Code | Dominant Function | Representative Land Use | Example of Satellite Remote Sensing Image | Environmental Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production-oriented landscapes | POLs | Production function | Dry land, paddy land, watered land, land for agricultural facilities, orchards, tea plantations and other gardens, etc. |  |  |

| Living-oriented landscapes | LOLs | Living function | Town sites, rural settlement sites, transportation road sites |  |  |

| Ecological-oriented landscapes | EOLs | Ecological function | Forested land, shrubland, other forested land, natural pasture and other grasslands, etc. |  |  |

| lake, river, inland mudflats, artificial reservoirs, ditches, and land for water facilities |  |  | |||

| Development-potential landscapes | DPLs | Multifunctional potential | Sand, bare ground, and other land |  |  |

| Category | Specification | Source | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEM | 30 m | Geospatial Data Cloud platform of the Chinese Academy of Sciences: https://www.gscloud.cn/, accessed on 10 August 2020 | Terrain zoning (Section 2.3.1) |

| Meteorological data (temperature and precipitation) | 1 km | Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research Chinese Academy of Science: https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home, accessed on 4 January 2024 | Driving factors analysis (Section 2.3.2) |

| Road network | Vector | OpenStreetMap (OSM): https://www.openstreetmap.org/, accessed on 6 March 2024 | |

| Socioeconomic indicators | County-level | People’s Government of Hanyuan County Ya’an Bureau of Statistics Field research information |

| Terrain Gradient | TNI | Areal Proportion/% |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.22~0.41 | 2.18 |

| 2 | 0.41~0.53 | 3.94 |

| 3 | 0.53~0.60 | 34.30 |

| 4 | 0.60~0.65 | 46.98 |

| 5 | 0.66~0.79 | 12.60 |

| Category | Indicator | Variable | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic | Population density | X1 | person/km2 |

| Farmers’ per capita net income | X2 | CNY | |

| Year-end cultivated land area | X3 | % | |

| Location | Distance to nearest road | X4 | m |

| Distance to township center | X5 | m | |

| Tourism | Distance to dining/lodging | X6 | m |

| Distance to scenic spots | X7 | m | |

| Distance to water bodies | X8 | m | |

| Climate | Annual mean temperature | X9 | °C |

| Annual mean precipitation | X10 | mm | |

| Terrain | Elevation | X11 | m |

| Slope | X12 | ° |

| Type | 2013–2018 | 2018–2023 |

|---|---|---|

| POL | −0.3240 | 3.6637 |

| LOL | 1.1031 | 2.3467 |

| EOL | 0.0002 | −0.0027 |

| DPL | 0.0770 | −4.9627 |

| Time | 2018 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | POL | LOL | EOL | DPL | |

| 2013 | POL | 65.09% | 6.43% | 24.72% | 3.76% |

| LOL | 32.84% | 48.23% | 15.60% | 3.33% | |

| EOL | 4.94% | 0.68% | 92.22% | 2.16% | |

| DPL | 22.91% | 5.09% | 47.30% | 24.70% | |

| Time | 2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | POL | LOL | EOL | DPL | |

| 2018 | POL | 80.28% | 8.05% | 9.89% | 1.78% |

| LOL | 18.74% | 70.89% | 8.29% | 2.08% | |

| EOL | 6.78% | 1.96% | 90.00% | 1.26% | |

| DPL | 37.65% | 6.39% | 27.32% | 28.64% | |

| Period | Homsmer–Lemeshow (HL) | Area Under ROC Curve | Independent Variable | Regression Coefficient (β) | Standard Error (SE) | Statistics (Wald) | Significance (Sig) | Incidence Rate (Exp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2018 | 0.403 | 0.762 | Distance to township center (X5) | −0.453 | 0.206 | 4.819 | 0.028 | 0.636 |

| Distance to dining/lodging (X6) | −1.034 | 0.255 | 16.400 | 0.000 | 0.356 | |||

| Annual mean temperature (X9) | 0.825 | 0.310 | 7.100 | 0.008 | 2.283 | |||

| Annual mean precipitation (X10) | −0.607 | 0.256 | 5.643 | 0.018 | 0.545 | |||

| 2018–2023 | 0.669 | 0.668 | Year-end cultivated land area (X3) | 0.261 | 0.127 | 4.226 | 0.040 | 1.298 |

| Distance to nearest road (X4) | 0.367 | 0.140 | 6.819 | 0.009 | 1.443 | |||

| Distance to township center (X5) | −0.467 | 0.150 | 9.756 | 0.002 | 0.627 | |||

| Annual mean precipitation (X10) | 0.298 | 0.150 | 3.960 | 0.047 | 1.348 | |||

| Slope (X12) | −0.214 | 0.109 | 3.861 | 0.049 | 0.807 |

| Period | Homsmer–Lemeshow (HL) | Area Under ROC Curve | Independent Variable | Regression Coefficient (β) | Standard Error (SE) | Statistics (Wald) | Significance (Sig) | Incidence Rate (Exp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2018 | 0.635 | 0.733 | Year-end cultivated land area (X3) | −0.411 | 0.152 | 7.312 | 0.007 | 0.663 |

| Distance to nearest road (X4) | −0.426 | 0.197 | 4.684 | 0.030 | 0.653 | |||

| Distance to township center (X5) | −0.432 | 0.172 | 6.312 | 0.012 | 0.650 | |||

| Distance to scenic spots (X7) | 0.385 | 0.147 | 6.883 | 0.009 | 1.469 | |||

| Annual mean temperature (X9) | 0.662 | 0.297 | 4.979 | 0.026 | 1.938 | |||

| Slope (X12) | −0.521 | 0.124 | 17.676 | 0.000 | 0.594 | |||

| 2018–2023 | 0.052 | 0.666 | Population density (X1) | 0.237 | 0.116 | 4.223 | 0.040 | 1.268 |

| Distance to nearest township center (X5) | −0.286 | 0.142 | 4.073 | 0.044 | 0.751 | |||

| Annual mean precipitation (X10) | −0.318 | 0.148 | 4.613 | 0.032 | 0.727 | |||

| Slope (X12) | −0.432 | 0.118 | 13.528 | 0.000 | 0.282 |

| Period | Homsmer–Lemeshow (HL) | Area Under ROC Curve | Independent Variable | Regression Coefficient (β) | Standard Error (SE) | Statistics (Wald) | Significance (Sig) | Incidence Rate (Exp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2018 | 0.227 | 0.759 | Distance to nearest road (X4) | 0.422 | 0.185 | 5.179 | 0.023 | 1.525 |

| Annual mean precipitation (X10) | −0.645 | 0.215 | 9.002 | 0.003 | 0.524 | |||

| 2018–2023 | 0.076 | 0.612 | Distance to township center (X5) | 0.346 | 0.111 | 9.657 | 0.002 | 1.414 |

| Distance to scenic spots (X7) | −0.324 | 0.144 | 5.054 | 0.025 | 0.723 |

| Period | Homsmer–Lemeshow (HL) | Area Under ROC Curve | Independent Variable | Regression Coefficient (β) | Standard Error (SE) | Statistics (Wald) | Significance (Sig) | Incidence Rate (Exp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2018 | 0.634 | 0.744 | Distance to township center (X5) | 0.390 | 0.129 | 9.105 | 0.003 | 1.447 |

| Distance to dining/lodging (X6) | 0.466 | 0.146 | 10.174 | 0.001 | 1.594 | |||

| Annual mean temperature (X9) | −0.790 | 0.209 | 14.353 | 0.000 | 0.454 | |||

| Annual mean precipitation (X10) | 0.939 | 0.219 | 18.337 | 0.000 | 2.556 | |||

| Slope (X12) | 0.270 | 0.109 | 6.170 | 0.013 | 1.311 | |||

| 2018–2023 | 0.492 | 0.676 | Distance to water bodies (X8) | 0.317 | 0.111 | 8.193 | 0.004 | 1.372 |

| Slope (X12) | 0.469 | 0.104 | 20.124 | 0.000 | 0.325 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, K.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Q.; Kang, C. Study on the Changes of Agritourism Landscape Pattern in Southwest China’s Mountainous Area from a Landscape Function Perspective: A Case Study of Hanyuan County, Sichuan Province. Land 2025, 14, 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122346

Wang K, Pan Y, Zhou J, Xu Q, Kang C. Study on the Changes of Agritourism Landscape Pattern in Southwest China’s Mountainous Area from a Landscape Function Perspective: A Case Study of Hanyuan County, Sichuan Province. Land. 2025; 14(12):2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122346

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Kailu, Yuanzhi Pan, Jiao Zhou, Qian Xu, and Chenpu Kang. 2025. "Study on the Changes of Agritourism Landscape Pattern in Southwest China’s Mountainous Area from a Landscape Function Perspective: A Case Study of Hanyuan County, Sichuan Province" Land 14, no. 12: 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122346

APA StyleWang, K., Pan, Y., Zhou, J., Xu, Q., & Kang, C. (2025). Study on the Changes of Agritourism Landscape Pattern in Southwest China’s Mountainous Area from a Landscape Function Perspective: A Case Study of Hanyuan County, Sichuan Province. Land, 14(12), 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122346