3.1. Lowess Results

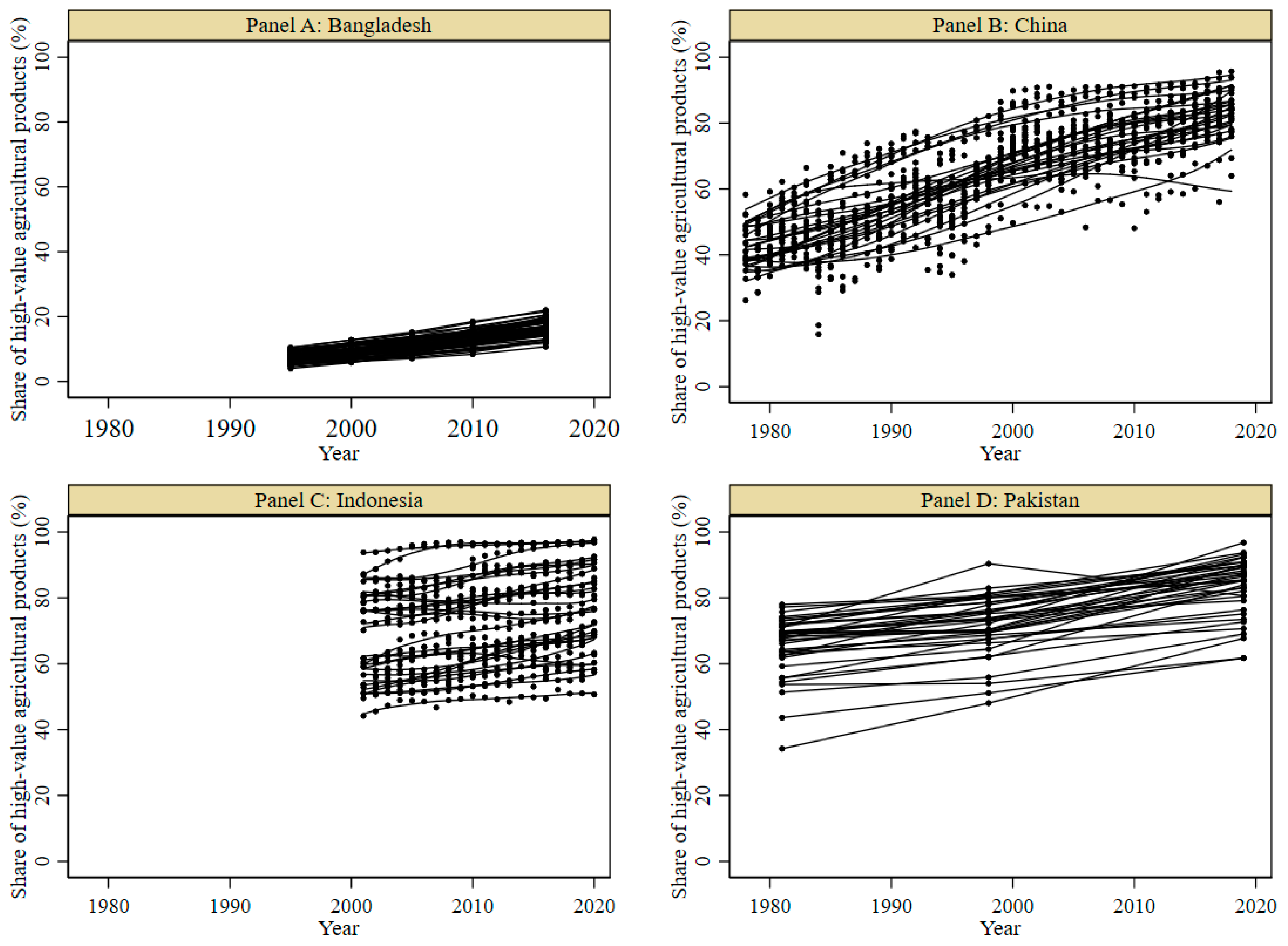

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 reveal the progress of RT in Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, and Pakistan. In

Figure 1, a commonality is evident in the overall upward trend of the share of HVAP over time, reflecting a general pattern of agricultural transformation and upgrading. However, differences are notable in both the transition paths and the speed of transformation. Bangladesh and Pakistan exhibit a more gradual increase, with Pakistan showing a more pronounced upward trend starting around 2000, while Bangladesh experienced a significant acceleration after 2000. Bangladesh’s level of HVAP is significantly lower than the other three countries due to differences in definitions based on the country’s local situation. In contrast, China’s share of high-value agricultural products has shown more rapid and consistent growth since the 1980s, particularly during the 1990s and early 2000s, indicating a faster pace of agricultural transformation. Indonesia presents a distinct pattern, characterized by fluctuations during the 1980s and 1990s giving way to more stable but slower growth after 2000. These variations underscore that while all four countries are shifting toward a greater share of high-value agricultural products, their specific trajectories and rates of change differ significantly.

These different rates of change in the share of HVAP identified in each country are influenced by natural endowments and policy focus. As an illustrative example, Bangladesh is a smaller country with similar, although constrained, land conditions throughout, while Indonesia is an archipelago with highly diverse land and agricultural production conditions, which influence the capacity to move into HVAP. These differing agricultural production conditions provide different enabling conditions for transitioning to HVAP. In addition, key policy reforms also influence the capacity to transition to HVAP. China’s key agricultural policy reforms have focused on market engagement with the provision of capital and increased services, which has enabled, in most regions, a transition into HVAP, whereas, in Indonesia, the policy focus has remained on rice agriculture to improve self-sufficiency.

Figure 2 illustrates an increasing trend in share of NFRE across Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, and Pakistan, indicating a common structural transformation within their rural economies. However, significant differences are evident in their transition paths and speeds: Bangladesh experienced a gradual rise with acceleration post-2000; China demonstrated a steep and continuous increase, particularly during the 1990s, reflecting rapid industrialization and urbanization; Indonesia showed initial fluctuations followed by steady growth from the late 1990s onward; and Pakistan exhibited diverse regional patterns, which are likely influenced by different agricultural sectors within each region. These variations highlight that while all four countries are shifting towards greater non-farm rural employment, the pace and nature of these structural shifts are significantly shaped by unique economic policies, geographical factors, and developmental strategies. Regions within countries that have enabled improved market access (i.e., coastal zone in China, regions in Indonesia in close proximity to the markets of Singapore and Malaysia) have seen the development of agricultural value chains that benefit from market access. These agricultural value chains have seen employment opportunities emerge as agricultural production delivers on market opportunities and as there is a transition into HVAP.

3.2. Bivariate Mapping Results

3.2.1. Rural Transformation in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s more homogeneous RT is due to its smaller, flatter land area with less complex economic structures with labor, land, and climate favorable for rice cultivation. Between 1995 and 2016, Bangladesh experienced a broad upward and rightward shift on the bivariate HVAP–NFRE maps (

Figure 3). These trends have been influenced by particular policies and programs including the Crop Diversification project, the Comprehensive Village Development Programme, and the Promoting Agricultural Commercialization and Enterprises, which have each enhanced market access and diversified farmer incomes. At the national level, thresholds for both high-value agricultural production (HVAP) and non-farm rural employment (NFRE) nearly doubled, underscoring the significant rural transformation occurring. In 1995, most regions were concentrated in the lower or middle quadrants, reflecting modest progress in crop diversification and limited off-farm opportunities. By 2016, many regions had moved into higher quadrants, with stronger colors on the maps reflecting an increase in higher-value agriculture and expanded rural non-farm labor markets. Yet, this overall improvement masks strong spatial heterogeneity, with some regions making significant progress in RT while others lag behind national progress.

The northwest belt of Bangladesh—including Rajshahi, Naogaon, Bogra, Pabna, Rangpur, and Sirajganj—stands out as the region with the most pronounced synergic rise, where HVAP and NFRE advanced together (

Figure 3). In 1995, these regions were positioned in the mid-range on both axes; by 2016 they appear in darker purple/blue quadrants, indicating joint improvements. The drivers are clear: Barind irrigation projects expanded Boro rice and high-value crops, agricultural research centers promoted pulses, fruits, and vegetables, and improved connectivity allowed surplus production to reach Dhaka and export markets. At the same time, non-farm rural opportunities in services, trade, and migration accelerated. This synergy created one of Bangladesh’s RT frontiers.

In the central regions surrounding Dhaka—Gazipur, Narayanganj, Narsingdi, Tangail, Manikganj, and Munshiganj—the dominant pathway has been NFRE-driven transformation. In 1995, these areas were largely agrarian. By 2016, they had very high NFRE but only moderate HVAP growth, as indicated by the deep purple shades. Factors influencing this NFRE-driven transformation are Dhaka’s urban pull and industrial spillovers: garment manufacturing, peri-urban industries, and service sector expansion absorbed rural labor. Regions like Gazipur and Narayanganj illustrate the strongest integration into the national industrial economy; in particular, textile production is highly concentrated in Gazipur district, while Tangail and Narsingdi have the combined agro-processing industries.

The southwest coastal belt of Bangladesh—Khulna, Satkhira, Bagerhat, Jashore, Narail, and Magura—reflects a different pathway, one that is HVAP-driven (

Figure 3). In 1995, these regions were only modest performers; by 2016 they moved sharply upward in HVAP, reflecting the rise of aquaculture, shrimp farming, and vegetable production for domestic and export markets. NFRE also expanded but less dramatically than in the Dhaka belt. Shrimp farming in Khulna and Satkhira created major export linkages, while Jashore diversified into vegetables and floriculture. This specialization has brought income gains but also ecological risks such as salinity intrusion.

The northeast region of Bangladesh (Sylhet, Moulvibazar, Habiganj, Sunamganj) follows a distinctive remittance- and consumption-driven transformation. In 1995, it was marked by low HVAP and modest NFRE. By 2016, NFRE indicators improved significantly, but HVAP remained weaker compared to the northwest or the southwest. Increased remittance inflows stimulated service and construction employment rather than farm intensification. Tea estates and citrus production provide some HVAP gains, but overall, the agricultural base remains underdeveloped.

In the southeast of Bangladesh, including Comilla, Chattogram, Cox’s Bazar, Feni, and Noakhali, the dominant trajectory has been NFRE-driven transformation. Comilla has expanded garment and small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) clusters and also huge remittance inflows, while Chattogram’s port economy, industrial parks, and services have drawn in significant rural labor. Cox’s Bazar added tourism employment due to the longest seabeach in the south Asian region, reinforcing NFRE gains. HVAP grew but was secondary to NFRE growth, positioning these regions as gateways of industrial and service-led transformation.

The southern Barisal belt of Bangladesh—Barisal, Bhola, Patuakhali, Barguna, Jhalokati, and Pirojpur—lags behind in overall RT. These regions continue to have low HVAP and low NFRE, as indicated by the lighter-colored areas on the bivariate maps (

Figure 3). Some incremental progress is visible in Barisal, but overall transformation has been slow. These areas suffer from geographic isolation, recurrent cyclones, intrusion of saline water, riverbank erosion, and weak infrastructure. As a result, RT has been constrained, and poverty remains entrenched.

Bangladesh’s regional-level patterns of RT reveal multiple pathways under a common national trend of rising HVAP and NFRE. The northwest showcases a synergic model where agriculture and non-farm activities reinforce each other. The Dhaka belt and the southeast illustrate NFRE-driven growth linked to urbanization, garments, and industrialization. The southwest demonstrates HVAP-driven transformation through aquaculture and high-value crops (vegetables and floriculture). The Sylhet region underscores a remittance-consumption model with limited agricultural upgrading. The Barisal belt highlights persistent laggards, where climate vulnerability and poor connectivity inhibit transformation. Together, these maps show how geography, infrastructure, technology, migration, market integration, and policy interact to shape diverse RT trajectories across Bangladesh.

3.2.2. Rural Transformation in China

China’s RT has been influenced by a step-by-step approach to broad policy reform, strong market orientation, investment in infrastructure, improved contract management of rural land, and improved extension systems to modernize the agricultural sector.

Figure 4 shows the evolution of regional-level RT in China from 1978 to 2018, using four benchmark years—1978, 1995, 2006, and 2018. During this period, landmark policies such as marketization reform (1985), the mechanization promotion law (2004), the abolishment of the agricultural tax (2006), environmental and sustainability policies (post-2010), and the rural revitalization strategy (2017) have all significantly influenced China’s RT.

The maps show a decisive national shift in China’s RT over the four decades. In 1978, most regions were clustered at the lower end of NFRE despite some regions in the northeast and coastal areas already providing HVAP. By 1995, the maps reveal an upward and rightward drift, with clear increases in HVAP and the first signs of substantial NFRE growth. By 2006, both axes had expanded further: thresholds for HVAP and NFRE had almost doubled, and regions in the east and south were consistently in higher quadrants. By 2018, the distribution was polarized: coastal and central regions were firmly embedded in high-HVAP–high-NFRE zones, while some western and interior regions lagged due to weaker NFRE gains. Overall, China’s RT path shows rapid intensification of agriculture and diversification of rural economies but with persistent regional disparities.

The coastal regions (e.g., Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Fujian, Shandong) illustrate a synergic rise pathway, where both HVAP and NFRE expanded dramatically (

Figure 4). By 2006 and especially 2018, these regions had both high levels of HVAP and NFRE. Coastal modernization was driven by township and village enterprises (TVEs) from the 1980s onward, integration into global markets and value chains, specialization in horticulture, aquaculture, and export-oriented crops, alongside booming non-farm rural industries. The combination of agricultural upgrading and industrial employment made the eastern seaboard the epicenter of China’s RT. This indicates the crucial role of trade liberalization, openness, and an export-oriented growth in driving structural transformation. The region’s proximity to growing markets, integration into global value chains, and early adoption of TVEs contributed to the deepening of rural non-farm economies [

22].

Regions in the Central Plains (Henan, Anhui, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi) shifted upwards strongly on HVAP (

Figure 4), reflecting their role as China’s grain basket and center of agricultural intensification. Mechanization, irrigation expansion, hybrid rice, and strong state support policies enabled substantial productivity gains. NFRE also increased, but not as dramatically as in coastal regions, leaving many regions in the Central Plains on an HVAP-driven pathway. By 2018, these regions had robust agricultural surpluses but remained less diversified than coastal regions, highlighting the challenge of absorbing surplus labor into non-farm rural sectors.

The northeastern regions (Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning) stand out as high HVAP performers since 1978 (

Figure 4), with mechanized large-scale farming and soybean/corn production. However, their NFRE growth has been less dynamic compared to coastal or central regions. By 2018, they remain relatively high on HVAP but mid-range on NFRE, reflecting structural challenges such as aging rural populations, declining heavy industries, and limited diversification. This is a stable high-agriculture model with weaker non-farm dynamism.

The western and interior regions (Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Yunnan, Guizhou) consistently lagged in both HVAP and NFRE. In 1978 they were concentrated in the lower quadrants; by 2018, despite improvements, many remained lagging, reflecting weaker transformation, as indicated by lighter shades (

Figure 4). Challenging physical geography (mountains, deserts, arid conditions), limited infrastructure, and persistent poverty constrained both agricultural intensification and RNFE. Some regions (e.g., Xinjiang) have niche HVAP gains (cotton and horticulture), but overall, these regions represent the lagging transformation pathway.

The southwestern regions (Sichuan, Chongqing, Guangxi, Yunnan) show gradual progress. Sichuan, once a labor-sending region, illustrates how outmigration and remittances drove consumption and services, while agricultural restructuring shifted towards vegetables, livestock, and aquaculture. By 2018, these regions moved closer to the middle–high quadrants, reflecting balanced but slower transformation heavily shaped by migration and policy-driven rural development investments.

China’s RT between 1978 and 2018 reflects a rapid national rise in both HVAP and NFRE but along very different regional pathways. The eastern coastal regions (e.g., Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Shandong) followed a synergic rise trajectory, where agricultural diversification, export-oriented crops, and TVEs jointly propelled HVAP and NFRE. The Central Plains (Henan, Anhui, Hubei, Hunan) represent an HVAP-driven pathway, with major gains in grain productivity but slower non-farm diversification. The Northeast (Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning) maintained a stable-high agricultural model, with consistently high HVAP but more stagnant NFRE. In the Southwest (Sichuan, Chongqing, Guangxi, Yunnan), transformation was migration- and remittance-led, with gradual agricultural diversification but heavy reliance on outmigration. By contrast, the Western regions (Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Guizhou) remained laggards, constrained by geography, infrastructure, and poverty, showing slower gains in both HVAP and NFRE. Together, these trajectories reveal how national growth and structural transformation coexisted with persistent regional inequalities, reflecting the enduring coastal–inland divide in China’s development.

3.2.3. Rural Transformation in Indonesia

Indonesia’s RT has significant regional disparities due to its archipelago and diverse economic activities, which occur at a relatively slower pace due to some commodity sectors’ (e.g., palm oil, rubber, coffee, and tea) boom limiting the transition into HVAP.

Figure 5 illustrates Indonesia’s RT dynamics across three pivotal years (2001, 2010, and 2019), revealing distinct regional pathways. The RT dynamics of Indonesia are influenced by more granular policies, such as the Indonesia–Malaysia–Singapore Growth Triangle benefiting regions within the triangle and localized limitation, such as South Sumatra’s continued low productivity rice production due to limited production environment. In addition, policies biased towards rice production and self-sufficiency such as fertilizer subsidies, R&D focused on the rice sector, and infrastructure development that favors rice production, also limit RT.

Indonesia’s RT between 2001 and 2019 reveals a broad shift upward in HVAP and rightward in NFRE (

Figure 5). In 2001, most regions clustered around low-to-mid HVAP and moderate NFRE. By 2010, thresholds had shifted upward and rightward, reflecting agricultural intensification and a rise in rural services and manufacturing. By 2019, the distribution widened further, with certain regions moving firmly into high-HVAP and/or high-NFRE quadrants, but many eastern regions remained laggards. Overall, the maps indicate uneven but notable progress, shaped by resource endowments, industrial location, and decentralization reforms.

The regions of Java (West Java, Central Java, East Java, Yogyakarta, Jakarta) and Bali illustrate an NFRE-driven transformation pathway. From 2010, becoming more pronounced in 2019, these regions had some of the highest NFRE scores, driven by industrialization, manufacturing, and services linked to urban growth poles. Agriculture remains important, with horticulture, rice, and livestock intensification, but the dominant trend has been labor absorption into the garment, electronics, tourism, and service industries. Bali, in particular, demonstrates transformation shaped by tourism and service employment rather than agriculture. Java became increasingly dominated by NFRE-driven pathway, as indicated by its blue coloring (

Figure 5), reflecting its dense population, strong urban–rural linkages, and the expansion of the service and industrial sectors.

Sumatra (North Sumatra, West Sumatra, Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, Lampung) exhibits a mixed pathway, with significant HVAP growth (palm oil, rubber, coffee, horticulture) but varying levels of NFRE. North Sumatra and Lampung show higher NFRE gains due to urban spillovers and agro-processing, while regions like Jambi and Riau remain more HVAP-driven through plantation crops. This reflects Sumatra’s dual role as an agricultural export hub and a site of resource-based industrialization. Lampung transitioned from low HVAP and NFRE towards an NFRE-driven transformation.

The Kalimantan regions (West, Central, South, East) primarily show HVAP-oriented transformation, heavily tied to plantation crops (palm oil) and natural resource industries (timber, coal). NFRE increased in mining and services, but less evenly distributed compared to Java and Sumatra. By 2019, Kalimantan regions remained agriculture- and resource-heavy, with weaker diversification into labor-intensive non-farm employment.

The Sulawesi regions (South Sulawesi, North Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi, Gorontalo, Central Sulawesi) demonstrate emerging synergic transformation. Southeast Sulawesi underwent a dynamic transformation, shifting from high HVAP and medium NFRE to peak levels in both variables. HVAP rose steadily with cocoa, coffee, and fisheries, while NFRE also expanded, with Makassar as a growth hub. The region reflects the importance of agro-exports combined with urban-led service expansion. Notably, this dual progression in Southeast Sulawesi signifies successful HVAP-NFRE integration, likely stemming from a number of factors. First, the government promotes agricultural diversification, value-chains, and agribusiness development. Second, the mining sector growth results in investments in associated infrastructure and services, creating NFRE opportunities. Third, the moderate out-migration allows labor to maintain adequate farm and non-farm labor supply.

The eastern regions remain laggards across both HVAP and NFRE. By 2019, they still occupied lighter quadrants, indicating slow agricultural intensification and limited non-farm diversification. Geographic isolation, weaker infrastructure, and higher poverty levels constrain transformation. Some localized improvements in fisheries and niche crops (e.g., nutmeg in Maluku, cocoa in Papua) are visible but insufficient to shift overall performance.

Indonesia’s RT is marked by both progress and inequality. Java and Bali represent an NFRE-driven model, reflecting industrialization, services, and tourism. Sumatra follows a mixed HVAP–NFRE model, with strong plantation agriculture and uneven industrialization. Kalimantan remains HVAP-resource driven, tied to palm oil, mining, and timber. Sulawesi demonstrates an emerging synergic model, combining cocoa/fisheries with urban services. The Eastern regions continue as laggards, shaped by remoteness and weak infrastructure. Nationally, RT has deepened between 2001 and 2019, but the persistence of a western–eastern divide mirrors broader patterns of uneven development in Indonesia.

Indonesia’s spatially differentiated trajectories underscore the need for region-specific policy responses. For stagnant regions like Kalimantan, targeted interventions to stimulate both agricultural upgrading and rural diversification are critical. Meanwhile, Java’s NFRE-dominant transformation calls for policies that enhance rural labor productivity and ensure equitable access to emerging non-farm opportunities. In regions like Southeast Sulawesi, efforts should focus on consolidating gains, promoting inclusive agri-food value chains, and maintaining environmental sustainability alongside economic growth.

3.2.4. Rural Transformation in Pakistan

Pakistan’s RT has significant regional heterogeneity and is reasonably slow due to land area and diverse natural conditions.

Figure 6 traces Pakistan’s RT evolution over nearly four decades (1998–2019), underscoring gradual but uneven progress with increasing HVAP-NFRE convergence over time. Key policies, such as the Khushal Pakistan Program in the early 2000s and the Prime Minister’s Kissan Package, have been influential with a focus on infrastructure and available finance.

Between 1998 and 2019, Pakistan experienced a moderate but uneven process of RT. At the national level, the maps reveal an upward and rightward shift in both HVAP and NFRE (

Figure 6), though the pace of change was slower and more fragmented than in neighboring countries such as Bangladesh or China. In 1998, most regions clustered in the lower and middle quadrants, reflecting a rural economy dominated by staple crops and with limited diversification into non-farm sectors. By 2019, several regions, particularly in Punjab, had made significant strides in agricultural intensification and in linking to industrial and service employment. However, transformation was highly uneven across regions, with clear divides between Punjab’s irrigated core and the more peripheral regions of Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), and Balochistan.

Punjab stands out as the most dynamic region of Pakistan’s RT (

Figure 6). Central and northern regions such as Faisalabad, Sargodha, Gujranwala, Sheikhupura, and Lahore (mix-cropping and rice–wheat cropping zones) clearly illustrate a synergic rise, combining gains in HVAP—through cereals, specifically rice as a cash crop, sugarcane, citrus, mangoes, and vegetables—with the expansion of NFRE linked to the textile, agro-processing, and manufacturing clusters. By contrast, the regions of southern Punjab (cotton–wheat cropping zone), including Bahawalpur, Rahim Yar Khan, Bahawalnagar, and Multan, progressed more slowly. While cotton and mango production supported some HVAP gains, NFRE opportunities remained limited, leaving these regions in the lower quadrants. Western Punjab, stretching through Dera Ghazi Khan, Bhakkar, and Layyah, shows mixed progress, marked by modest productivity increases but continued weak integration into the non-farm economy. The decline in cotton production in these regions of Pakistan started in the years 2015–2016. Cotton lint production in the country peaked to 13.96 million bales, then started to drop significantly, reaching 5.5 million bales by 2025. This marks a decade-long trend of decline driven by factors like climate change, pest infestations, and economic challenges. Crop productivity declined from 802 to 475 kg per hectare. Due to the low profitability of cotton, farmers replaced the crop mainly with sugarcane, maize, and rice and, to a lesser extent, sesame and sunflower.

Sindh presents a more polarized picture. Regions around Karachi and Hyderabad benefited most from industrial and port-related NFRE growth, while peri-urban corridors linked agriculture with urban consumption. Upper Sindh regions such as Sukkur, Larkana, and Khairpur registered HVAP gains through rice, dates, and vegetables, but these advances were less matched by NFRE expansion, illustrating a more HVAP-driven pathway. In contrast, southern and rural Sindh—including Tharparkar, Thatta, Badin, and Umerkot—remain lagging. Chronic water scarcity, salinity, and climate shocks continue to constrain both farm productivity and non-farm employment, leaving these regions clustered in the low-HVAP, low-NFRE category.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), transformation has been led more by non-farm opportunities than by agriculture. Northern regions such as Mardan, Swabi, Abbottabad, and Haripur recorded modest HVAP growth in fruits, vegetables, and tobacco, but stronger NFRE gains driven by migration, remittances, and local small industries. Southern KP regions, including Kohat, Bannu, Karak, and Dera Ismail Khan, advanced more slowly, with agriculture being less diversified and NFRE more dependent on labor migration. Taken together, KP illustrates a remittance- and NFRE-driven transformation pathway, with weaker agricultural upgrading than Punjab.

Balochistan remains the least transformed region of Pakistan. Most regions, such as Kalat, Khuzdar, Chagai, Gwadar, and Kharan, continue to sit in the low-HVAP, low-NFRE zones. Some northern regions, including Quetta, Pishin, and Ziarat, show HVAP gains in niche horticulture like apples, grapes, and pomegranates, but these gains did not translate into significant non-farm employment. Ongoing security challenges in Balochistan significantly hinder investment and development initiatives, adversely affecting both infrastructure and community stability. Additionally, the region’s low population density complicates the delivery of essential services, making it economically unviable for businesses to operate efficiently. Furthermore, agricultural productivity has been severely impacted by inefficient farming practices, over-extraction of groundwater, and rangeland degradation. These interconnected factors have contributed to keep Balochistan lagging behind the rest of the country despite its diverse natural resource base.

Overall, Pakistan’s RT since 1998 demonstrates multiple pathways. Central and northern Punjab exemplify a synergic rise, while southern Punjab and Sindh remain laggards. Sindh’s irrigated northern core illustrates an HVAP-driven model, while the peri-urban Karachi–Hyderabad corridors show NFRE-led growth. KPK reflects remittance- and NFRE-led transformation, and Balochistan remains the most structurally constrained. The contrast between Punjab’s core regions and the more peripheral regions highlights the fragmented nature of Pakistan’s transformation and the persistence of regional inequalities in development.

3.2.5. Factors Constraining Rural Transformation in Laggard Regions

Despite the overall upward trends in high-value agricultural products (HVAP) and non-farm rural employment (NFRE), several regions across the four countries remain trapped in slow or stagnant transformation pathways. The underlying causes of this stagnation are multidimensional.

Geographic isolation plays a primary role. Remote coastal and mountainous areas such as Barisal in Bangladesh, eastern Indonesia, and Balochistan in Pakistan face higher transport and transaction costs that limit access to markets and inputs. These physical barriers discourage private investment and reduce the profitability of shifting toward high-value agriculture.

Infrastructure deficits—particularly in rural roads, irrigation networks, electricity, and storage facilities—further weaken the enabling environment for transformation. Without reliable connectivity, farmers struggle to adopt modern technologies or reach non-farm employment opportunities.

Institutional and governance weaknesses compound these challenges. In many lagging regions, land tenure insecurity, limited extension services, and weak local governance reduce farmers’ ability to invest or diversify production. Access to credit and insurance is also highly unequal, constraining the adoption of productivity-enhancing practices.

Environmental and climatic factors—such as salinity intrusion in coastal Bangladesh, recurrent droughts in Pakistan, and natural disasters in Indonesia—exacerbate vulnerability and deter long-term investment.

Together, these constraints create a form of path-dependent under-transformation: regions starting with poor infrastructure and weak institutions tend to experience slower structural change, even when national policies are supportive. Addressing these bottlenecks requires targeted spatial strategies that integrate infrastructure investment, institutional reform, and place-based development policies to unlock rural transformation potential.