Toward an Integrative Framework of Urban Morphology: Bridging Typomorphological, Sociological, and Morphogenetic Traditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To review the epistemological foundations and methods of major morphological schools;

- (2)

- To identify the conceptual gaps and overlaps between static, dynamic, and structural reasoning;

- (3)

- To propose a meta-framework that integrates these approaches; and

- (4)

- To demonstrate the relevance of interdisciplinarity as a means of advancing urban morphological research.

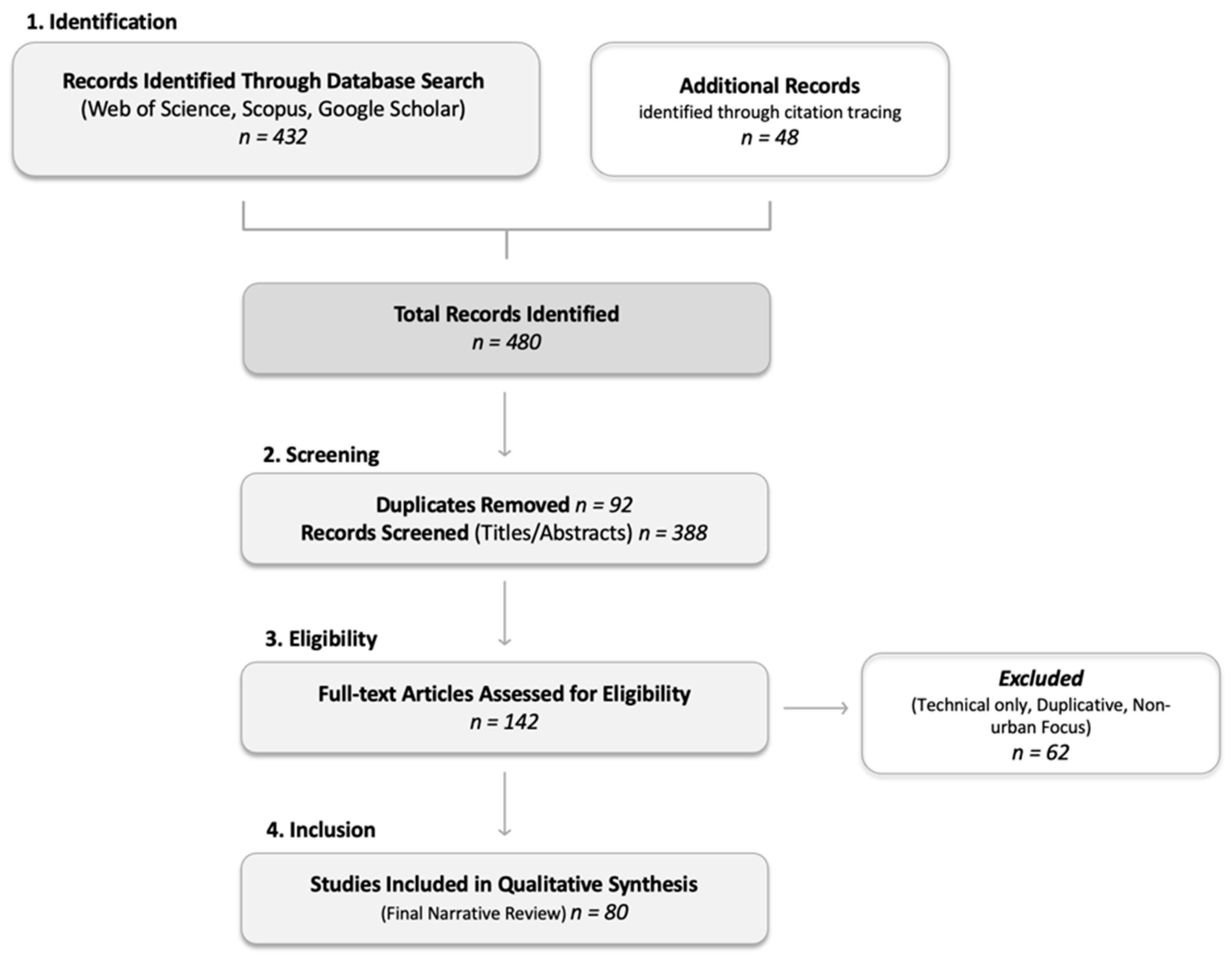

2. Research Design and Methodology

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Literature Selection and Scope

2.3. Analytical Framework and Coding Logic

3. The Urban Morphology in Question

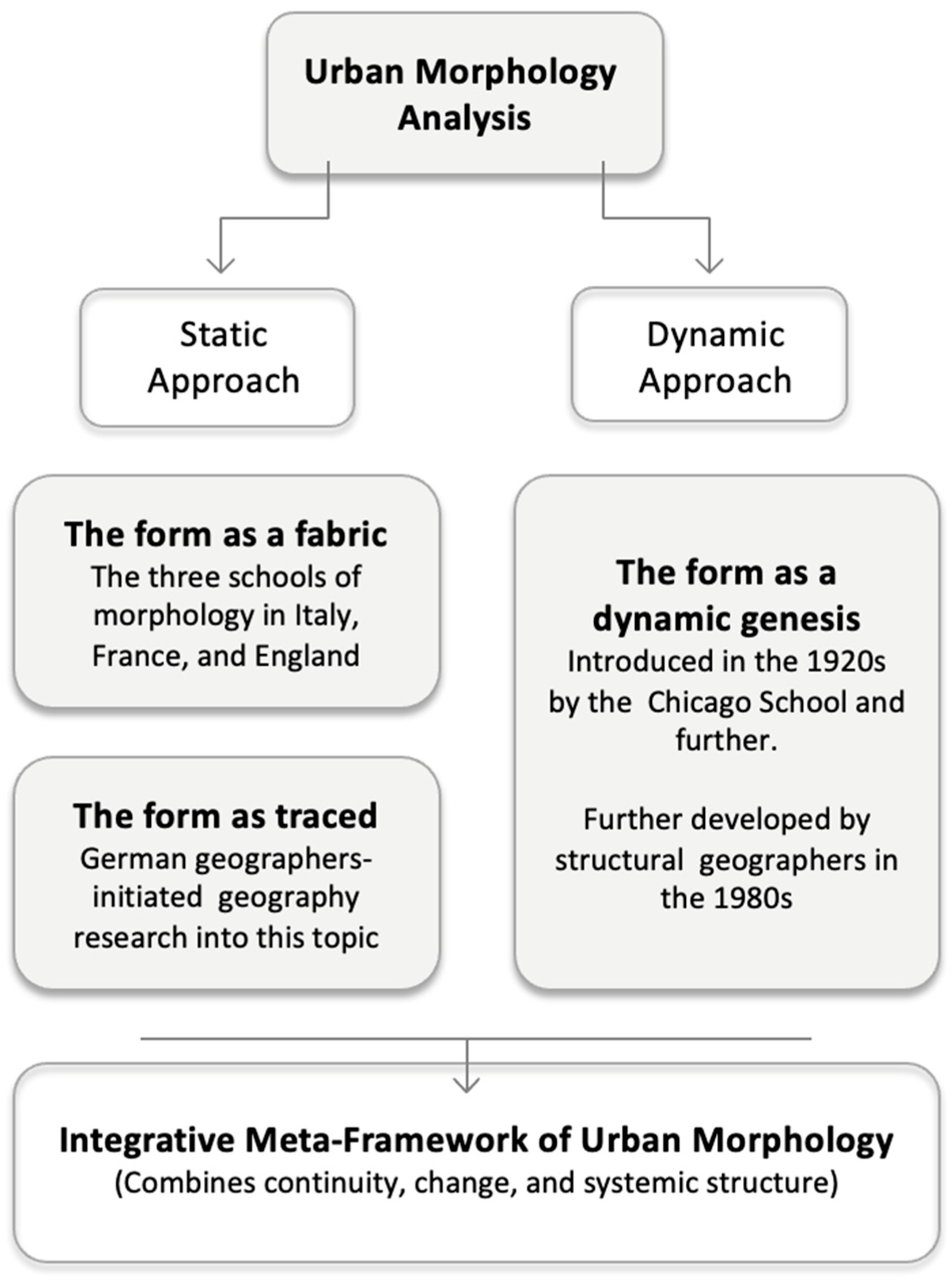

4. Models of Urban Morphology

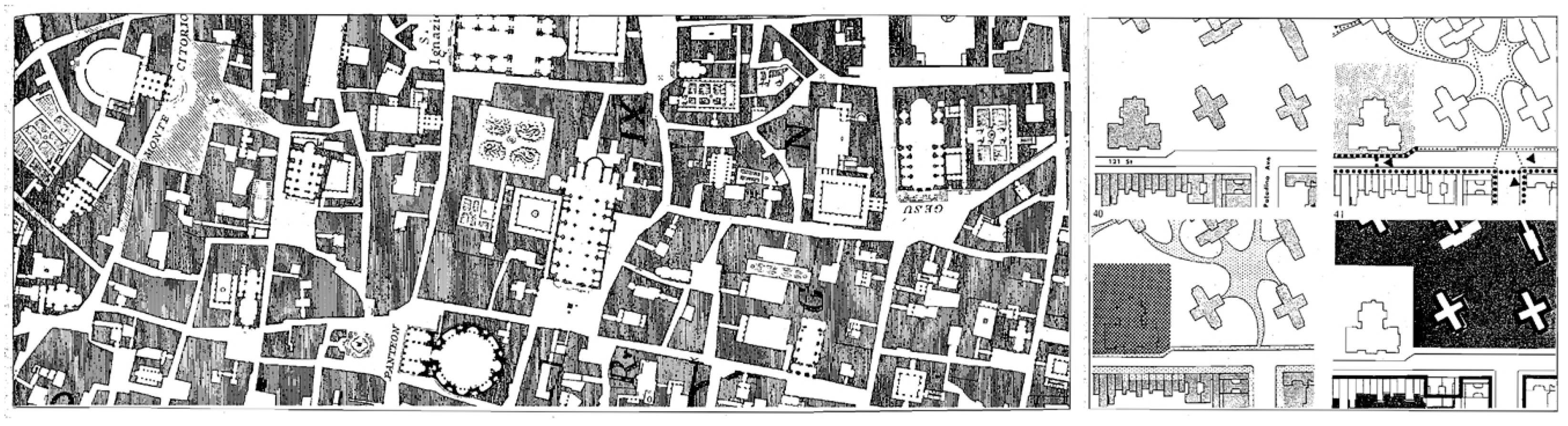

4.1. The Three Schools of Urban Morphology

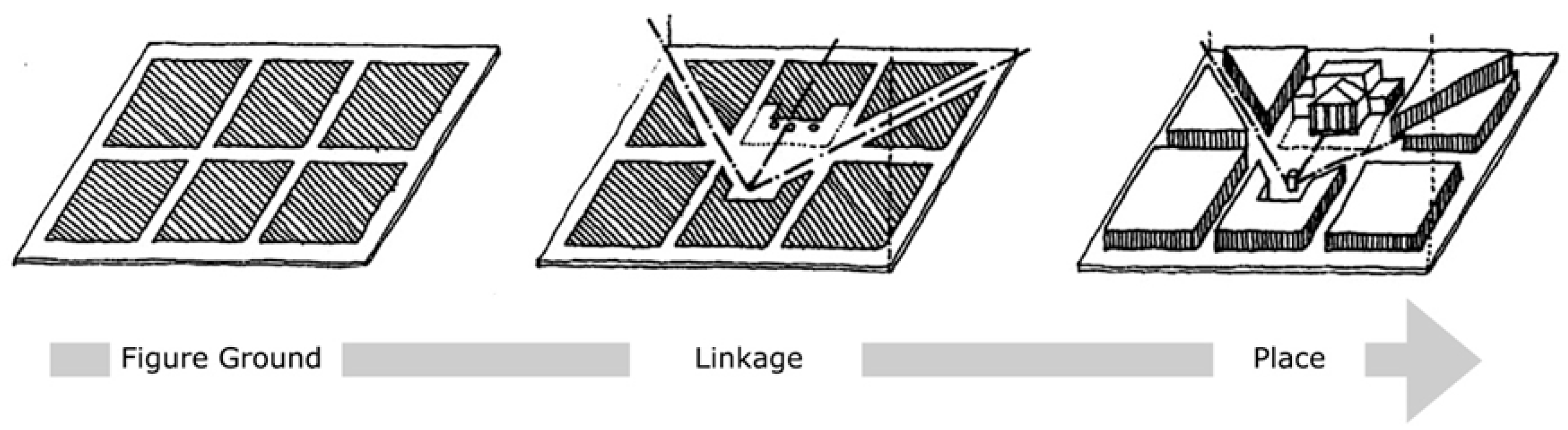

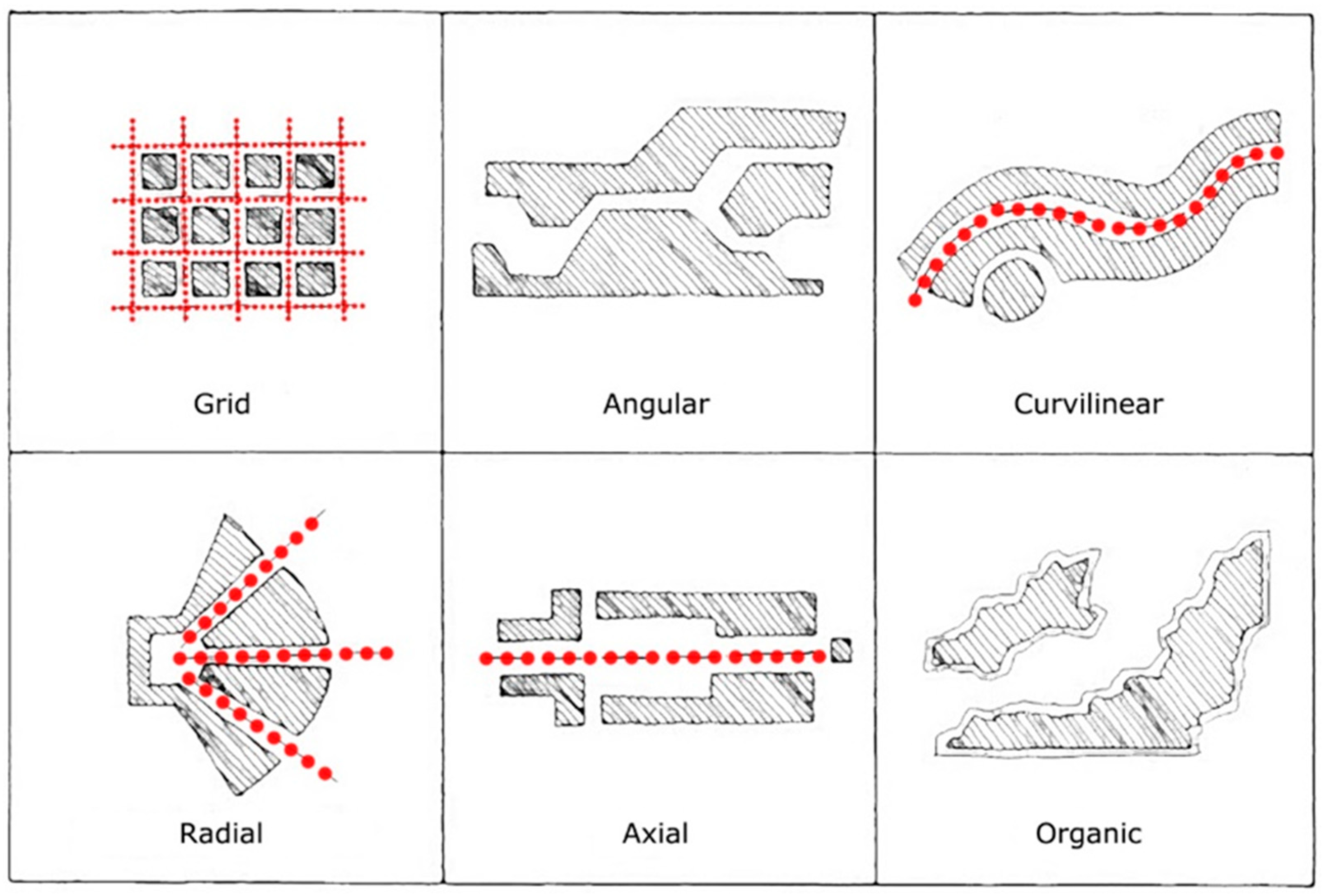

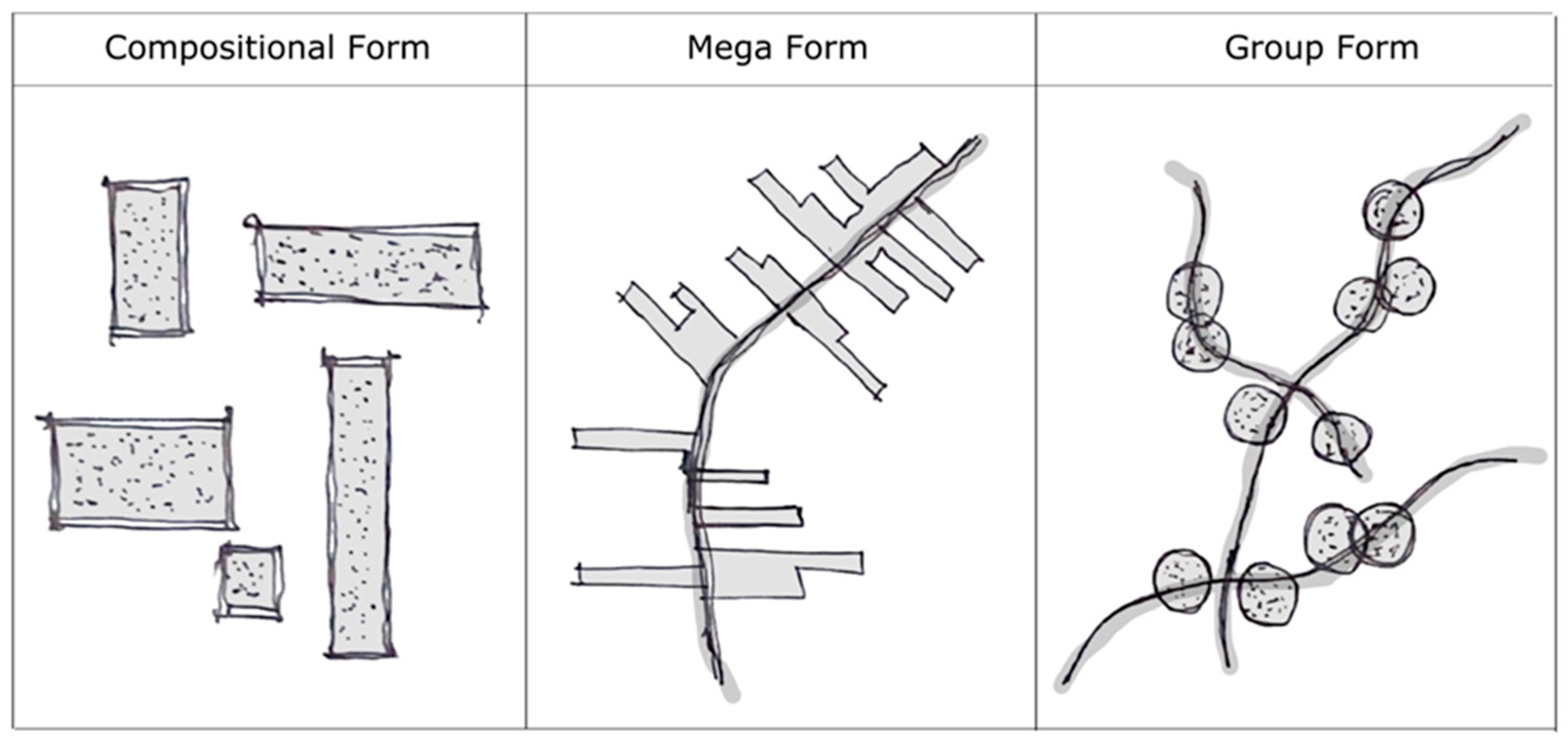

The Dialectical Connection Between Urban Design and Urban Morphology

4.2. The Dynamic Approaches to Urban Form

4.2.1. The Chicago School

4.2.2. The Relationship of Spatial Organization to the Economy

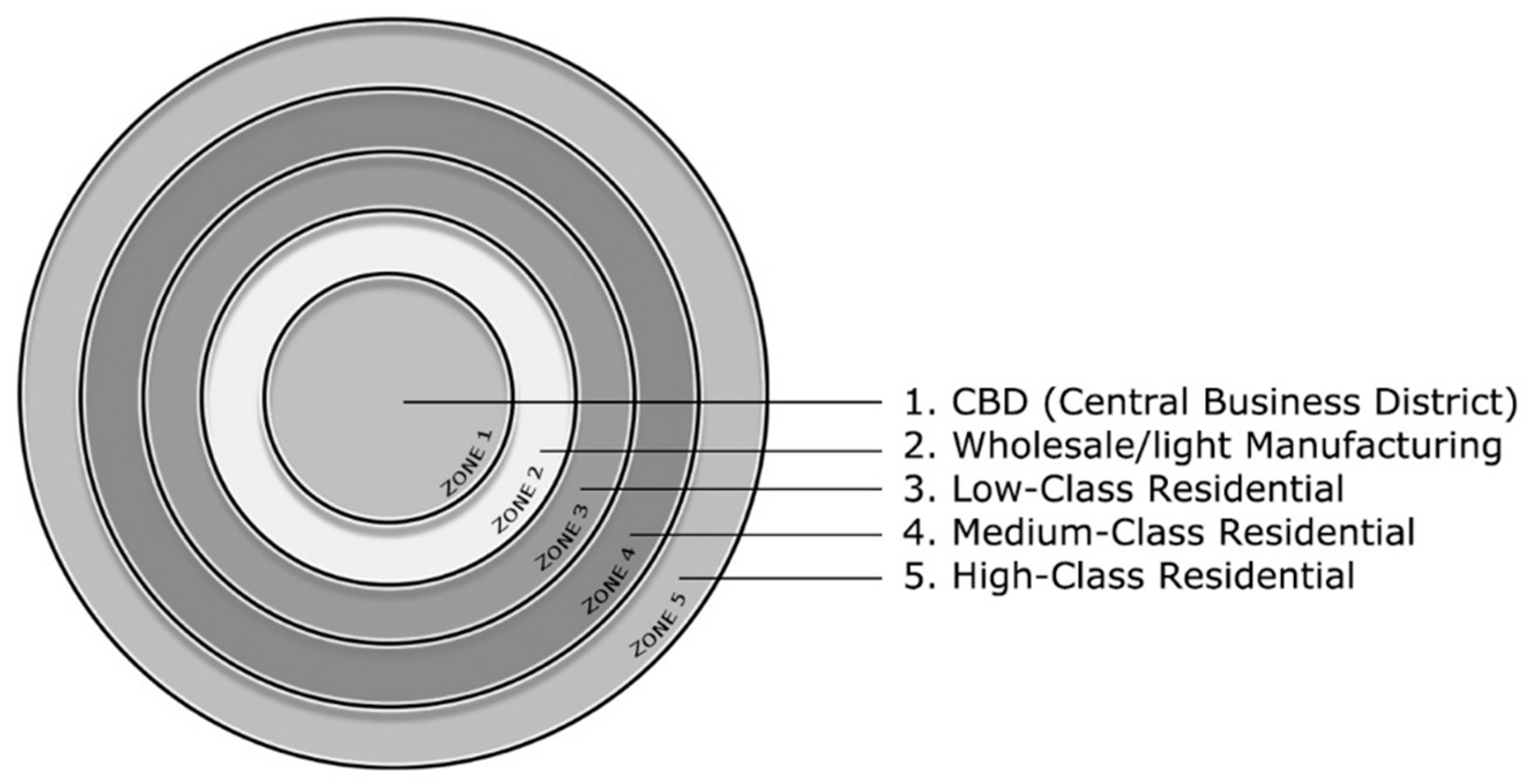

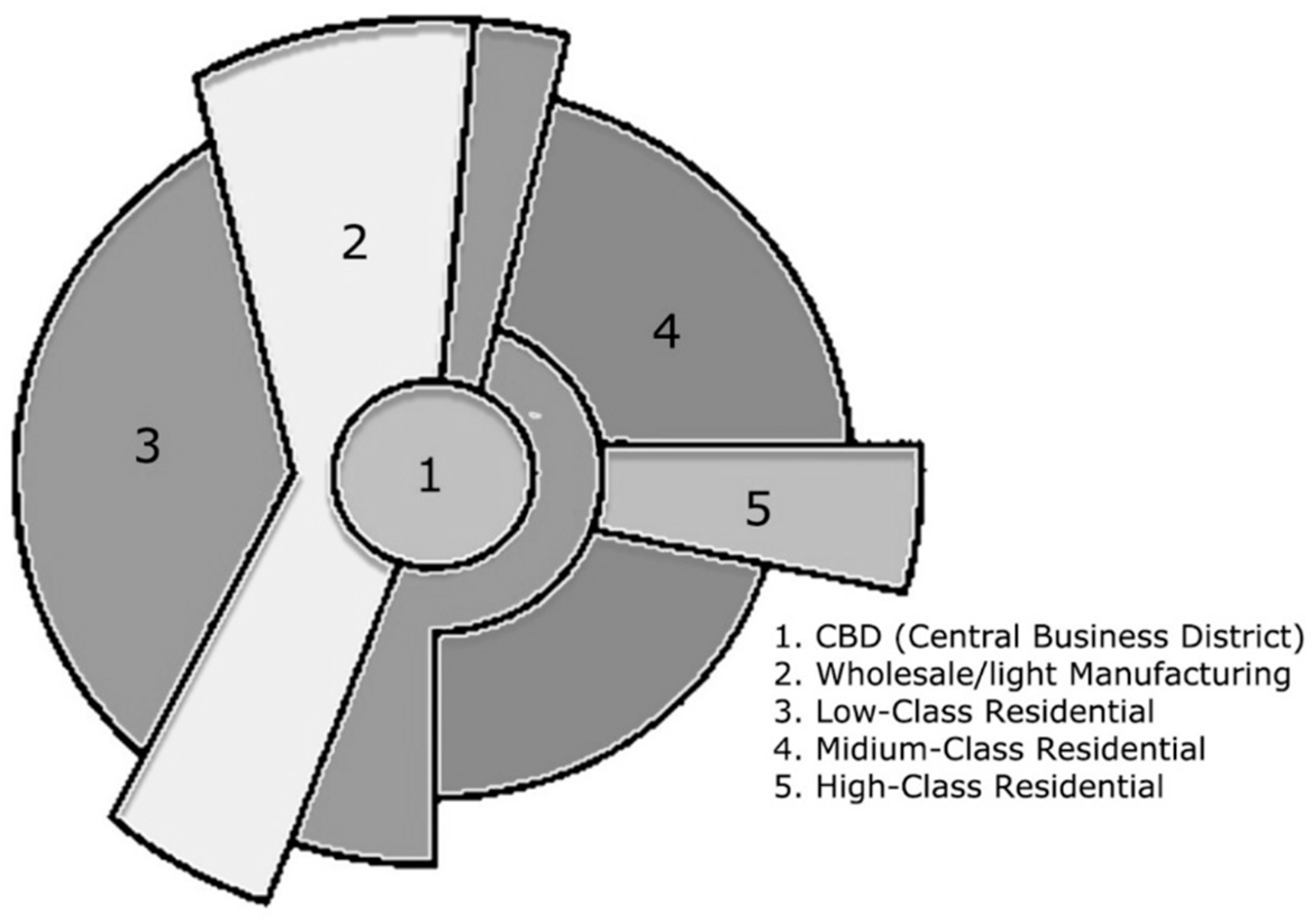

4.2.3. The Models Developed by the Chicago School

- i.

- An attractiveness of the center. This attractiveness is due to most jobs being performed in the city center and the value of having a short commute to work.

- ii.

- A process known as “invasion”, which occurs as a result of this attractiveness. It is an agglomeration effect centered on the appealing center.

- iii.

- The aspect of “resistance on the spot” is a reaction to social group competition. This opposition is manifested by the assertion that individuals are members of a group. Members of groups tend to prefer residing together and would rather have members of other groups reside elsewhere.

- iv.

- Resistance on the spot has two outcomes: if it fails, it leads to position abandonment and repression in the periphery (groups abandoning neighborhoods); if it succeeds, it manifests as adaptation on the spot and position consolidation (formation of quarters: the Greek Quarter, Bronzeville, Chinatown, etc.).

- v.

- The various concentric zones are formed as a result of a dynamic sequence of invasion, resistance, abandonment, and adaptation.

- i.

- Attractive high-rent areas contribute to a city’s growth.

- ii.

- During growth, sectors can widen and lengthen.

- iii.

- When a high-rent class moves into an area, they stay for a long time.

- iv.

- High-rent neighborhoods are moving outward. These sectors don’t invade others. They fill empty spaces.

- v.

- When a high-rent class leaves, a low-rent class moves in.

- vi.

- High-rent areas tend to develop along the most efficient transportation routes, often leading to affluent suburbs, shopping centers, or natural parks.

- i.

- Agglomeration economies, or the clustering of similar and complementary activities in the same industry.

- ii.

- The distance between wealthy or affluent and underprivileged neighborhoods.

- iii.

- Competition for land use, certain activities, or certain social groups not having the means to afford more advantageous locations (Figure 9).

4.3. New Model of Morphogenesis

4.3.1. The Theory of Urban Morphogenesis

- i.

- The investment of anthropological values in very particular organizing centers, which they call “vacuums.”

- ii.

- Flows or trajectories of political control of settlement mobility appropriating spaces around vacuums.

- iii.

- Conflicting settlement mobility trajectories create hidden structural positions.

- iv.

- The diversified valuation of these positions by the situation rent.

- v.

- The construction of concrete forms of spatial occupation is stimulated by rent.

- vi.

- The profitability of concrete forms through economic activities.

4.3.2. The Structuring of Space

- i.

- ii.

- They only consider centripetal and centrifugal space appropriation and occupation flows, not settlement mobility. This leads to a static conception that cannot formalize the evolution and historical transformation of specific entities.

- i.

- Monumental forms with sought-after architecture, sumptuous urban squares, temples, institutional buildings, luxury apartment towers, and expansive urban parks serve as gathering places (R).

- ii.

- Working-class suburbs and neighborhoods, low-rent complexes (HLM foothills), and informal housing neighborhoods (wilderness suburbs) are concentrations (C).

- iii.

- The city is organized structurally by a threshold configuration where (R/C) positions overlap. High-value buildings and low-value suburbs rub shoulders.

- iv.

- The city’s influence on villages externalizes (C/D) positions. In each, an institutional building (such as a church, town hall, or post office) stands out from the surrounding craft houses, shops, and workshops.

- v.

- The countryside is typical of dispersed positions (D) that are dependent on the city, as livestock and agriculture have low demographic densities.

- vi.

- The sprawl of suburbs, often far from dense agglomeration, projects concrete urban forms (E/D) onto rural areas.

- vii.

- Affluent suburbs as well as luxurious resort fronts materialize escapes (E).

- viii.

- Bourgeois and select neighborhoods combine positions of escape and positions of assembly (R/E).

- ix.

- Artisan, commercial, or middle-class neighborhoods combine escape and concentration (E/C).

- x.

- Certain public squares or monumental voids materialize vacuums that give rise to gatherings followed by dispersals (R/D).

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Comparative Coding Outcomes

5.2. Toward an Integrative Framework of Complementarity

5.3. Interdisciplinary and Theoretical Contribution

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kropf, K. The Handbook of Urban Morphology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, A. Urban sustainability assessment: An overview and bibliometric analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Claramunt, C. Integration of space syntax into GIS: New perspectives for urban morphology. Trans. GIS 2002, 6, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo de Oliveira, V.M. The Study of Urban Form: Different Approaches. In Urban Morphology: An Introduction to the Study of the Physical Form of Cities; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 141–197. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.X.; Qiu, C.; Hu, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Schmitt, M.; Taubenböck, H. The urban morphology on our planet–Global perspectives from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehand, J.W. Issues in urban morphology. Urban Morphol. 2012, 16, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, M.; Feliciotti, A.; Kerr, W. Evolution of urban patterns: Urban morphology as an open reproducible data science. Geogr. Anal. 2022, 54, 536–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; La Rocca, L. Urban regeneration processes and social impact: A literature review to explore the role of evaluation. In Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2021: 21st International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; Proceedings, Part VI; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, K. Urban Morphology of the Chinese City: Ases from Hainan; University of Waterloo: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, M. Empiricism and Geographical Thought. In From Francis Bacon to Alexander von Humbolt; University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C. The Morphology of Landscape; University of California Publications in Geography: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1925; Volume 2, pp. 296–315. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, E. Garden Cities of Tomorrow; Faber: London, UK, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Corbusier, L. The Radiant City: Elements of a Doctrine of Urbanism to be Used as the Basis of Our Machine-Age Civilization; Orion Press: Raymond, WA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, F.L. When Democracy Builds; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Kropf, K. The handling characteristics of urban form. Urban Des. 2005, 93, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehand, J. Urban morphology, urban landscape management and fringe belts. Urban Des. 2005, 93, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The image of the environment. In The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960; Volume 11, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. Jane jacobs. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961; Volume 21, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. Notes on the Synthesis of Form; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, P. Architectural Morphology: An Introduction to the Geometry of Building Plans; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.Y. Innovations in Urban Computing: Uncertainty Quantification, Data Fusion, and Generative Urban Design; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, M.J.T. An Approach to Built-Form Connectivity at an Urban Scale: Variations of Connectivity and Adjacency Measures Amongst Zones and other Related Topics. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1979, 6, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Penn, A.; Hanson, J.; Grajewski, T.; Xu, J. Natural movement: Or, configuration and attraction in urban pedestrian movement. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1993, 20, 29–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzen, M.P. Analytical Approaches to the Urban Landscape. Dimensions of Human Geography; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978; pp. 128–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ledrut, R. La Forme et le Sens Dans la Société; FeniXX: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lévy, A. Formes urbaines et significations: Revisiter la morphologie urbaine. Espaces Sociétés 2005, 122, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncayolo, M. Lectures de Villes. Formes et Temps; Éditions Parenthèses: Marseille, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.E.; Burgess, E.W. Introduction to the Science of Sociology; Good Press: Glasgow, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M.; Tiesdell, S. Urban Design Reader; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais, G.; Ritchot, G. La Géographie Structurale; Éditions L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2001; pp. 1–148. [Google Scholar]

- Moudon, A.V. Urban morphology as an emerging interdisciplinary field. Urban Morphol. 1997, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M.M.; Noaime, E. Typological transformation of individual housing in Hail City, Saudi Arabia: Between functional needs, socio-cultural, and build polices concerns. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noaime, E. La Transformation Socio-Morphologique de la Ville dans les Processus de Métropolisation: L’exemple d’Alep Depuis Sa Fondation Jusqu’en 2011; Université de Strasbourg: Strasbourg, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Conzen, M.R.G. Alnwick, Northumberland: A Study in Town-Plan Analysis. Transactions and Papers; Institute of British Geographers: London, UK, 1960; Volume 27, p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehand, J.W.R.; Samuels, I.; Conzen, M.P. Conzen, M.R.G. 1960: Alnwick, Northumberland: A study in town-plan analysis. Institute of British Geographers Publication 27. London: George Philip. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, G.; Li, B. Urban Morphology: Comparative Study of Different Schools of Thought. Curr. Urban Stud. 2019, 7, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldai, G.; Maffei, G.L.; Vaccaro, P. Saverio Muratori and the Italian school of planning typology. Urban Morphol. 2002, 6, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzot, N. The study of urban form in Italy. Urban Morphol. 2002, 6, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A. L’architecture de la Ville (1966); L’Equerre: Paris, France, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehand, J. Urban morphology and policy: Bridging the gap. Urban Morphol. 2007, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V. The study of urban form: Different approaches. In Urban Morphology: An Introduction to the Study of the Physical Form of Cities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 87–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Panerai, P.; Castex, J.; Depaule, J.-C. Formes Urbaines: De L’îlot a la Barre; Editions Parentheses: Marseille, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, S. History, Space and Place; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, P. La morphologie urbaine vue par les experts internationaux. In Proceedings of the Morpgologie Urbaine et Parcellaire: Colloque d’Arc-et-Senans, Arc-et-Senans, France, 28–29 October 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, P.; Schenke, K.C. Predictive social perception: Towards a unifying framework from action observation to person knowledge. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G. Measuring the complexity of urban form and design. Urban Des. Int. 2018, 23, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Zhang, W. The way to measure and establish an emotional-based assessment of vertical urban complex. Cities 2025, 163, 106015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, G. Towards a general theory of urban morphology: The type-morphological theory. In Teaching Urban Morphology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bürgel, G. La Ville Aujourd’hui, Hachette, Coll; Pluriel: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, B. How Designers Think; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. The place-shaping continuum: A theory of urban design process. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Trancik, R. Finding Lost Space: Theories of Urban Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, I. L’école de Chicago: Naissance de L’écologie Urbaine; Aubier: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, M.J. The Chicago school of ethnography. In Handbook of Ethnography; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2001; pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lutters, W.G.; Ackerman, M.S. An introduction to the Chicago School of Sociology. Interval Res. Propr. 1996, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.; Burgess, E.; McKenzie, R. The City. Chicago; Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Alnaim, M.M.; Noaime, E. Spatial dynamics and social order in traditional towns of Saudi Arabia’s Nadji region: The role of neighborhood clustering in urban morphology and Decision-Making processes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, G. La Morphogenèse de Paris: Des Origines a la Révolution; Editions L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Noaime, E.; Alalouch, C.; Mesloub, A.; Hamdoun, H.; Gnaba, H.; Alnaim, M.M. Urban Centrality as a Catalyst for City Resilience and Sustainable Development. Land 2025, 14, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, G. Trois concepts-clés pour les modèles morphodynamiques de la ville. Cah. Géographie Québec 1998, 42, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, G. La structuration morphologique de la Rome antique, du centre organisateur à la configuration de seuil. Espaces Sociétés 2005, 122, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauphiné, A.; Péguy, C.-P. Les Théories de la Complexité Chez les Géographes; Anthropos: Reims, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I. Irreversibility and randomness. Astrophys. Space Sci. 1979, 65, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractal geometry: What is it, and what does it do? Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 1989, 423, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Haken, H. Synergetics. Phys. Bull. 1977, 28, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymond, H.; Cauvin, C. L’espace Géographique des Villes: Pour Une Synergie Multistrates; Anthropos Research & Publications: Sankt Augustin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boutot, A. Catastrophe theory and its critics. Synthese 1993, 96, 167–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchot, G. Prémisses d’une Théorie de la Forme Urbaine. Gilles RITCHOT et Claude FELTZ, Forme Urbaine et Pratiques Sociales, Editions Le Préambule/CIACO, Montréal, Louvain-la-Neuve. 1985, pp. 23–65. Available online: https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/cgq/1992-v36-n98-cgq2670/022268ar/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ritchot, G.; Feltz, C. Forme Urbaine et Pratique Sociale; Le Préambule: Cassis, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Petitot, J. Physique du Sens, Editions du CNRS; CNRS: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Thom, R. Stabilité Structurelle et Morphogénèse: Essai D’une Théorie Générale des Modèles; Addison Wesley Longman: Boston, MA, USA, 1972; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, C. Le triangle culinaire (1965). Food Hist. 2004, 2, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greimas, A.J. For a Topological Semiotics. In The City and the Sign; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, A. Sémantique Structurale, Formes Sémiologiques; PUF: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais, G. Projection ou émergence: La structuration géographique de l’établissement bororo. Semiot. Inq. 1992, 12, 189–215. [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais, G.; Ritchot, G. La modélisation dynamique en géographie humaine. Cah. Géographie Québec 1998, 42, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, G. Les centres organisateurs de l’écoumène: Des formes structurantes pour l’identité culturelle. Actes Sémiotiques 2008, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumain, D. Pour une Théorie Evolutive des Villes. In L’Espace Géographique; Editions Belin: Paris, France, 1997; pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Pumain, D.; Sanders, L.; Saint-Julien, T. Villes et Auto-Organisation; FeniXX: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, Y.-M. Megacity Seoul: Urbanization and the Development of Modern South Korea; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gohaud, E.; Arora, A.S.; Schuetze, T. Urban Form and Sustainable Neighborhood Regeneration—A Multiscale Study of Daegu, South Korea. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Time window | 1960–2025 | Captures canonical works and contemporary extensions |

| Disciplines/outlets | Architecture/urban design (Urban Morphology), planning/complexity (Environment & Planning B), geography/urban systems, and allied journals (Land, Cities) | Ensures cross-paradigm coverage |

| Databases & sources | Publisher sites + journal archives; backward/forward citation tracing from canonical texts | Complements keyword search with lineage mapping |

| Keywords (indicative) | Typomorphology, plot/parcel system, urban tissue, îlot, Chicago School, invasion–succession, sector model, multiple nuclei, morphogenesis, structural geography, positional structure, anisotropy | Targets each school’s core conceptual language |

| Inclusion criteria | (i) Paradigm-defining or programmatic texts; (ii) works explicating mechanisms or processes; (iii) contributions linking physical and social dimensions | Prioritizes explanatory and integrative relevance |

| Exclusion criteria | Purely technical applications without conceptual contribution; duplicate overviews; texts lacking urban form focus | Maintains conceptual signal over methodological repetition |

| Languages | Primarily English; seminal works in French and Italian when directly relevant | Preserves European school lineage and theoretical origins |

| Output of screening | Canon of ≈ 70–80 representative works balanced across schools | Enables comparative analysis without over-extension |

| Goal | Conceptual integration of static, dynamic, and structural views | Guides synthesis across disciplinary boundaries |

| Analytical Dimension | Conceptual Focus | Example Indicator | Representative Data Source/Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1. Ontology of Form | Physical, social, or structural conceptualization of urban form | Typological classification; structural schema | Conzen (1960); Muratori (1959); Rossi (1982) |

| D2. Epistemic Aim | Objective of inquiry (description, explanation, emergence) | Purpose statement; analytical orientation | Whitehand (1987); Moudon (1997) |

| D3. Scale of Analysis | Spatial hierarchy of analysis | Plot, block, neighborhood, systemic scale | Cataldi (2002); Kropf (2018) |

| D4. Mechanisms of Change | Transformation processes | Accumulation, invasion–succession, positional dynamics | Burgess (1925); Desmarais (1998) |

| D5. Tools Referenced | Analytical and representational methods | Mapping, typological survey, graph models | Hillier & Hanson (1989); Oliveira (2016) |

| D6. Social–Spatial Coupling | Integration of social and physical structures | Network density, land-use mix, behavioral indicators | Lefebvre (1991); Panerai et al. (1997) |

| D7. Design Relevance | Application to planning and design | Design guidelines; spatial policy connection | Trancik (1986); Carmona (2014) |

| Analytical Workflow for Integrative Urban Morphology | |||

| |||

| Analytical Dimension | British (Conzenian) | Italian (Typo- Morphological) | French (Versailles) | Contemporary Synthesis/Research Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontological focus | Urban form as historical palimpsest | Urban form as typological system | Urban form as socio-perceptual construct | Integrates material, typological, and experiential dimensions of form |

| Analytical unit | Plot, street, town plan | Building type, urban fabric | Urban block, lived space | Enables multi-scalar reading from parcel to perceptual field |

| Mechanism of change | Accumulation, adaptation, transformation, replacement | Typological continuity and mutation | Social practice, perception, and re-appropriation | Supports dynamic modeling of morphological change |

| Methodological tools | Cartographic analysis, map regression | Typological survey, historical parcellography | Observational and ethnographic analysis | Combines quantitative mapping with qualitative observation |

| Relation to society | Implicit—form reflects collective history | Mediated—form transmits social values through type | Explicit—form expresses social behavior and representation | Bridges physical and social interpretation of urban space |

| Design relevance | Conservation and landscape planning | Architectural and urban design guidance | Design as socio-cultural mediation | Expands from descriptive analysis to projective urban design |

| Key pioneers | Conzen, Whitehand, Larkham | Muratori, Rossi, Caniggia, Aymonino | Castex, Panerai, Depaule, Lefebvre | New synthesis: Oliveira, Moudon, Batty, Portugali |

| Epistemological contribution | Structural continuity | Historical typology | Socio-spatial experience | Toward integrated morphogenetic theory |

| Period | Focus | Representative Works |

|---|---|---|

| 1920–1950 | Foundations of the Chicago School and ecological models of urban growth | Burgess (1925), Park (1936), Hoyt (1939) |

| 1950–1970 | Emergence of European typomorphology and historical-geographical morphology | Muratori (1959), Conzen (1960) |

| 1970–1990 | Theoretical consolidation integrating type, structure, and perception | Caniggia & Maffei (1979), Rossi (1982), Panerai (1990), Whitehand (1987) |

| 1990–2025 | Methodological expansion and interdisciplinary synthesis | Desmarais (1995), Kropf (2001), Moudon (1997) |

| Directionality | Regulation | |

|---|---|---|

| - | Exoregulation | Endoregulation |

| Polarization | Gathering | Concentration |

| Diffusion | Evasion | Dispersion |

| Dimension | European School | Chicago School | Morphogenetic Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 Ontology of form | Static–Structural | Dynamic | Structural–Generative |

| D2 Epistemic aim | Description/Typology | Explanation/Process | Emergence/Structure |

| D3 Scale | Plot–Block–Îlot | Neighborhood–City | City–System |

| D4 Mechanisms | Historical transformation | Invasion–Succession | Positional thresholds (R, C, D, E) |

| D5 Tools (referenced) | Cartography, typological diagrams | Empirical mapping, statistics | Graphs, structural geometry |

| D6 Social–spatial coupling | Weak/Implicit | Strong/Explicit | Formalized (structural) |

| D7 Design relevance | High (urban fabric) | Medium (policy, zoning) | Moderate (structural modeling) |

| Criterion | If the School Excels at … | … But Is Limited by … | Then Complement with … | Expected Integrative Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static clarity vs. dynamics | Typological and fabric description (European) | Weakness in explaining mobility and process | Chicago mechanisms | Processual explanation of patterned change |

| Dynamics vs. anisotropy | Socio-spatial mobility and competition (Chicago) | Isotropic assumptions; weak attention to form | Morphogenetic positional structure + European descriptors | Directionally constrained and fabric-aware interpretation |

| Structure vs. concreteness | Positional thresholds and systemic logic (Morphogenesis) | Abstractness; low design specificity | European typology | Contextual and design-relevant structural guidance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noaime, E.; Alnaim, M.M. Toward an Integrative Framework of Urban Morphology: Bridging Typomorphological, Sociological, and Morphogenetic Traditions. Land 2025, 14, 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122323

Noaime E, Alnaim MM. Toward an Integrative Framework of Urban Morphology: Bridging Typomorphological, Sociological, and Morphogenetic Traditions. Land. 2025; 14(12):2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122323

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoaime, Emad, and Mohammed Mashary Alnaim. 2025. "Toward an Integrative Framework of Urban Morphology: Bridging Typomorphological, Sociological, and Morphogenetic Traditions" Land 14, no. 12: 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122323

APA StyleNoaime, E., & Alnaim, M. M. (2025). Toward an Integrative Framework of Urban Morphology: Bridging Typomorphological, Sociological, and Morphogenetic Traditions. Land, 14(12), 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122323