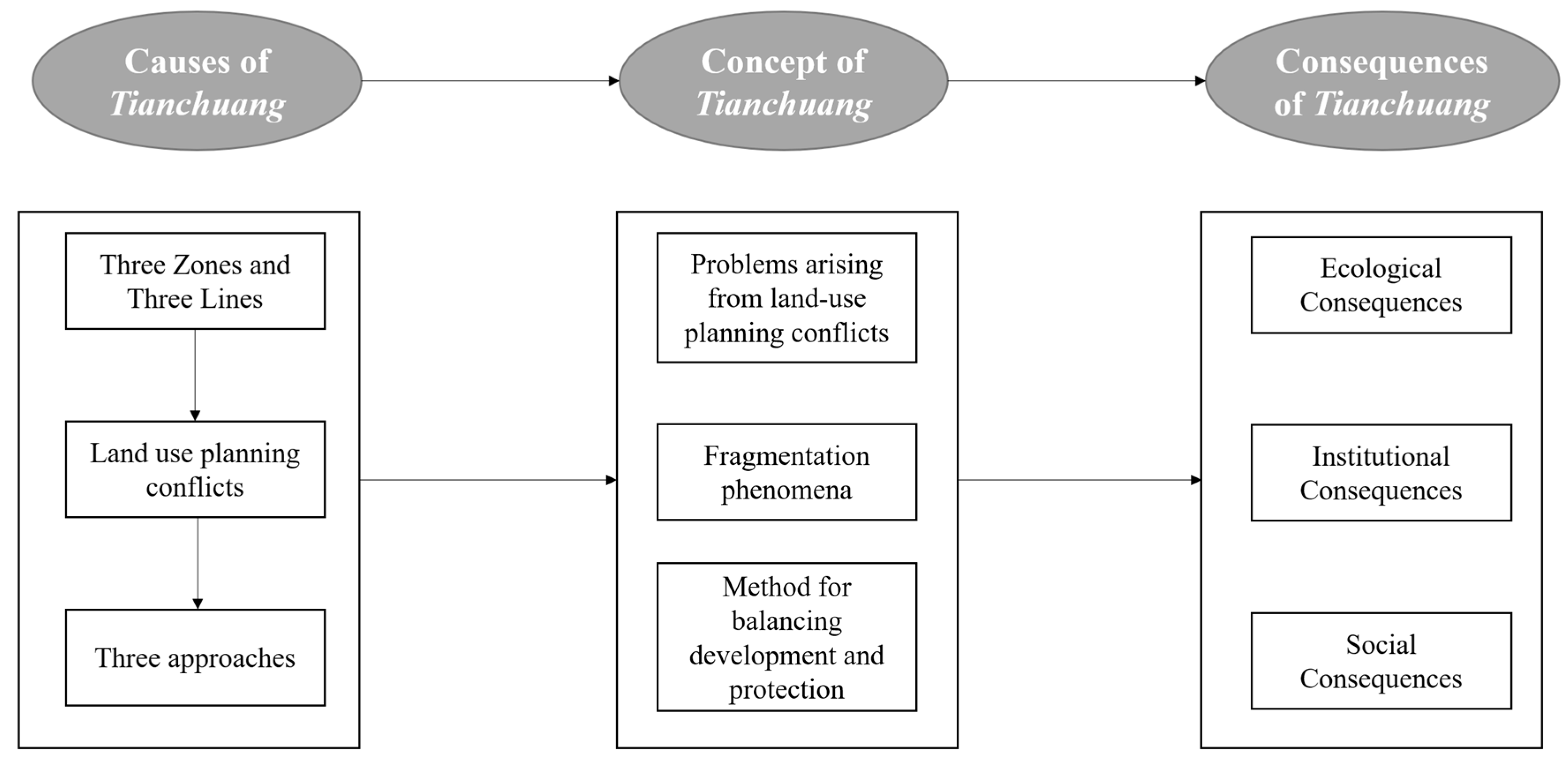

Tianchuang in National Parks of China: Its Concept, Causes, and Consequences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Concept of Tianchuang

3. Causes of Tianchuang

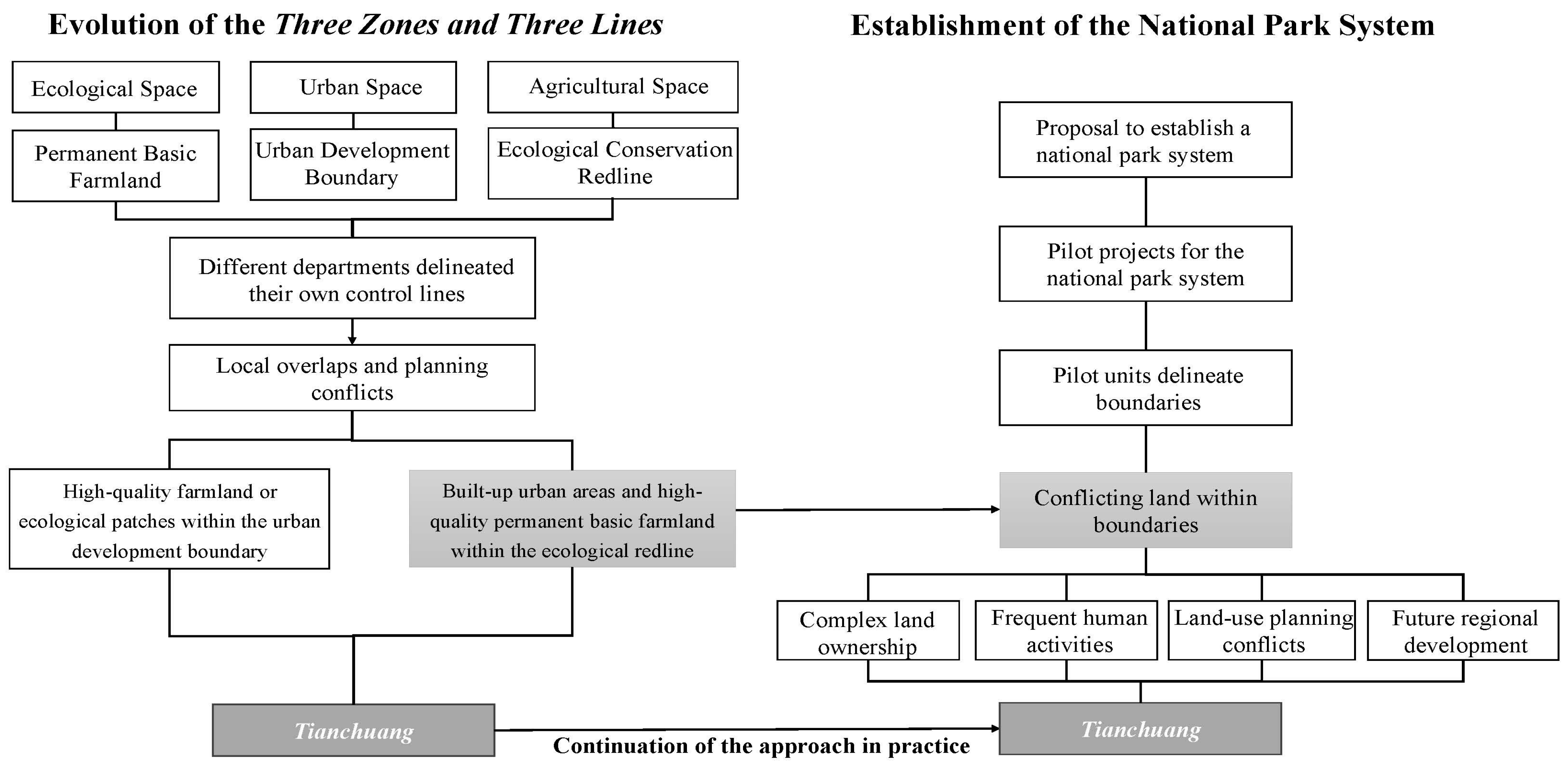

3.1. Policy Background: Spatial Overlaps and Functional Conflicts from Planning

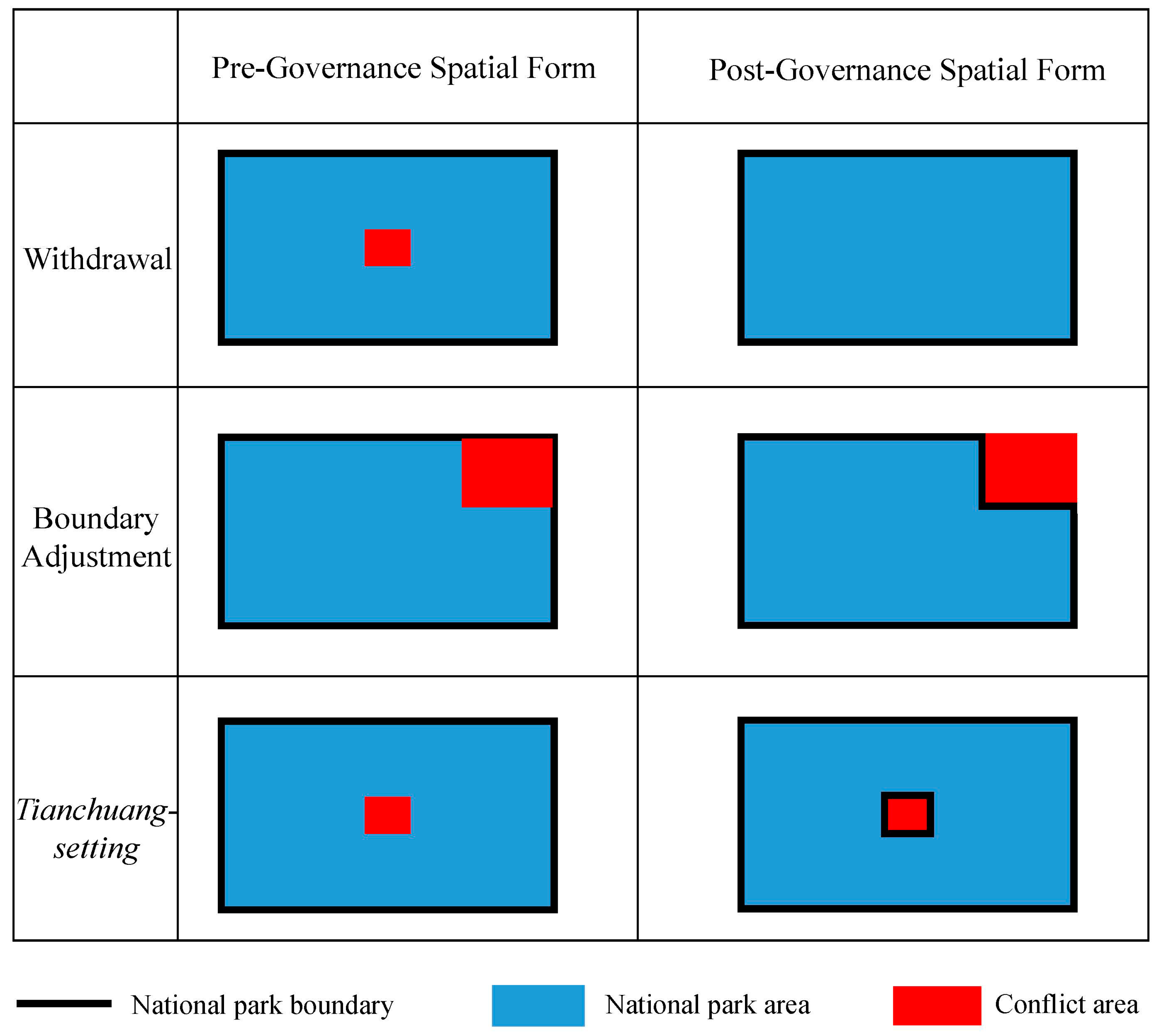

3.2. Three Approaches to Resolving Functional Conflicts: Withdrawal, Boundary Adjustment, and Tianchuang-Setting

- (1)

- Withdrawal refers to removing the existing human activities from the land parcels and converting its original usage to ecological usage, normally by the way of ecological relocation and usage restrictions. In this way, the national park boundaries and ecological red lines remain unchanged, and the management responsibility remains assumed by the national park. Withdrawal is generally applied in core protection zones, fit for areas having serious conflicts between ecological protection and human activities, but also having relocation feasibility and ecological restoration potential [39]. In practice, the feasibility of withdrawal depends on the financial capacity, local acceptance, and relocation conditions [40]. For example, in 2024, the Ministry of Natural Resources responded to the Suggestion on Overlapping Areas of Ecological Protection Red Lines and Permanent Basic Farmland in National Parks and Other Protected Areas [41], proposing that permanent basic farmland in core protection zones should be retained as general farmland and cultivation gradually withdrawn to restore ecological functions. Overall, withdrawal targets areas without significant value but with conflicts in management and ecological function threatened (the “one-with-two” areas). For example, low-quality farmland scattered in general control zones of national parks can take the approach of withdrawal.

- (2)

- Boundary adjustment refers to removing specific areas from national park boundaries or changing land use. In this way, both the areas’ space and management responsibilities will be fully separated from the national parks, and local governments will take the responsibilities [42]. This approach applies to areas that are clearly defined, spatially contiguous, and have long-term stable usage. These areas are normally at the edge of national parks’ boundaries and will be excluded during the official boundary delineation of the national park. For instance, the Response specifies that permanent basic farmland which is concentrated, spatially contiguous, stably used, and located out of core protection zones can be removed away from the national park. Additionally, quantity and quality balance of farmland can be achieved through additional allocation. Generally, areas without significant protection value, having no great ecological impacts or management conflicts (the “two-with-one” areas [41]), can be legally adjusted out. The advantage of the boundary adjustment approach is not involved with resident relocation, land use change, or large administrative costs. The disadvantage of this approach might involve insufficient supervision, ecological degradation, and disruption of ecological connectivity and functional integrity [43,44].

- (3)

- Tianchuang-setting refers to maintaining the current land usage, management responsibilities temporarily not incorporated into unified management, leaving governance to local governments until conditions are suitable for future integration. Tianchuang-setting applies to areas deep within park boundaries, with complex land tenure, concentrated populations, and are currently incapable of withdrawal or boundary adjustment. Tianchuang commonly includes permanent basic farmland, township settlements, and infrastructure dense regions. For example, some permanent basic farmland and cropland in national parksmay be temporarily retained and integrated later when the conditions are appropriate.

4. Consequences of Tianchuang

- (1)

- Ecological Consequences

- (2)

- Institutional Consequences

- (3)

- Social Consequences

5. Discussion

- (1)

- Formed in China, Tianchuang was temporarily retained under original usage and excluded from unified management because of planning conflicts, frequent human activities, and complex land tenure. Essentially, Tianchuang represents a transitional strategy under a centralized governance system to balance ecological protection objectives with local development needs during rapid boundary delineation [58]. In the United States, inholdings originated from a historical transition of land policy from “transfer” to “retention”. Large-scale land transfers in the 19th century had left private and state-owned parcels, which became enclosed by national park boundaries after park establishment. Given strong property rights and limited federal funds, the federal government could not compel acquisition of these parcels. The integration of these parcels relied on market tools (purchases and land exchanges) and were incomplete [59]. In Australia, co-managed at Uluru-Kata Tjuta originated from the recognition of indigenous land rights. In 1985, the land ownership of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was returned to the Anangu people and co-managed with the government through long-term leases and formalized agreements. Rooted in colonial legacies and Indigenous movements, it institutionalized cultural recognition and land-rights legitimacy [60]. In Nigeria, the GGNP enclaves originated from the traditional migratory pastoralism of the Fulani herders, who established camps locally. When the protected area was established, some camps were retained through negotiations between the state and local chiefs, forming de facto enclaves. With limited national finances and regulatory capacity, governance gradually relied on the traditional “chief–family–camp” structure and external international project support, evolving into a negotiated governance model prioritizing social stability [61].

- (2)

- Governance In China, Tianchuang follows a government-led model, where the central government sets policies and boundaries, and local authorities implement them, balancing community interests through categorized management and transitional compromises [62,63]. In the United States, inholding management exhibits a dual-track governance model, where the federal government enforces top-down ecological protection via land acquisition, eminent domain, or land-use regulations, while the local governments regulate private development from the bottom-up using planning, density control, and design review, balancing ecological protection with property rights [64]. In Australia’s Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, co-management is practiced. The Anangu, as landowners, hold a majority of seats on the board and jointly govern with the park authority. Community members also participate directly in ecological and tourism management through projects such as the Mutitjulu Mala Rangers, achieving a combination of rights and responsibilities [65]. In Nigeria, GGNP enclave governance reflects a bottom-up negotiated approach [66]. The Fulani communities maintain order using traditional governance structures, while the state and NGOs intervene through project collaboration and educational programs.

- (3)

- Challenges: In China, Tianchuang are faced with concentrated populations and infrastructure, complex land tenure, imperfect compensation, and withdrawal mechanisms, making policy implementation and local coordination difficult. Unclear responsibilities and insufficient coordination weaken protection enforcement and exacerbate community trust crises. In the USA, the main issues of inholdings are fragmented property rights and high acquisition costs, slowing integration; differences in state and local policies further complicate management, and ongoing private development in some areas undermines ecosystem integrity [59,67]. In Australia, the co-management of Uluru-Kata Tjuta are faced with the challenge of balancing the sacredness of indigenous culture with tourism development. The community livelihoods depend on external funding, while Anangu and Parks Australia still have divergences in governance responsibilities [68]. In Nigeria, GGNP enclaves are faced with conflicts between state and local community in terms of land tenure and governance rights. Local groups view enclaves as traditional lands with clear family ownership and usage rules, and the division of power between federal and local authorities, combined with diverse land tenure, makes central policies prone to conflict with local customs [69].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shrestha, A.; Zhou, X.; Teng, M.; Wang, P.; Wang, G. Exploring the main determinants of National Park community management: Evidence from bibliometric analysis. Forests 2023, 14, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.S.; Xiao, L.L. Path selection and research issues in the pilot construction of China’s National Park system. Resour. Sci. 2017, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, M.; Tao, Y.Z.; Tan, L.; Bai, H.N. Research on ecological management of National Parks. Nat. Reserves 2023, 3, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, T.L.; Li, N.; Huang, Z.P.; Li, Y.P.; Mu, Y.; Xiao, W. Research progress on the construction of National Parks in China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 4964–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.A.; Li, X. Optimizing the National Park management system in China: A case study at the central level. Biodivers. Sci. 2023, 31, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Q.Y.; Huang, B.R. The “Tianchuang” in China’s National Parks: Causes, status and management recommendations. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; He, S.Y. Management pathways and practices for National Park “Tianchuang”: Comparisons and insights from China and the USA. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zale, K. Inholdings. Harv. Environ. Law Rev. 2022, 46, 439–522. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, A.R.; Radeloff, V.C.; Helmers, D.P.; Mockrin, M.H.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Pidgeon, A. The extent of buildings in wildland vegetation of the conterminous U.S. and the potential for conservation in and near National Forest private inholdings. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.M.; Pidgeon, A.M.; Radeloff, V.C.; Helmers, D.P.; Culbert, P.D.; Keuler, N.S.; Flather, C.H. Long-term avian community response to housing development at the boundary of protected areas: Effect size increases with time. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddock, K.N.; Heinen, J.T. Conserving nature through land trust initiatives: A case study of the little traverse conservancy, Northern Michigan, USA. Nat. Areas J. 2017, 37, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.S.; Prochaska, N.; Keating, W.D. Bringing permanent affordable housing and community control to scale: The potential of community land trust and land bank collaboration. Cities 2022, 126, 103718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Xie, M.; Zhang, W.; Xia, C.; Yi, X.; Solomon, T.; Yin, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, C. International experience of community support for National Park development and its implications. For. Econ. Rev. 2025, 7, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, K.L. A Comparative Analysis of Co-Management Agreements for National Parks: Gwaii Haanas and Uluru-Kata Tjuta. Master’s Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sahabo, A.A. Community participation in tourist resort development in Gashaka Gumti National Park, North Eastern Nigeria. FUTY J. Environ. 2019, 13, 112–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kwesaba, D.A.; Daniel, O.E.; Delphine, D.; Benjamin, E. Examination of the challenges militating against the development of Gashaka-Gumti National Park, Nigeria. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2023, 10, b665–b673. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D.; Ross, C. Fulani of the Highlands: Costs and benefits of living in National Park enclaves. In Primates of Gashaka; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 283–317. [Google Scholar]

- Karanth, K.K.; Nepal, S.K. Local residents’ perception of benefits and losses from protected areas in India and Nepal. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariyam, D.; Gulati, S.; Karanth, K.K. Contradictions in Conservation: Education, Income, and the Desire to Live Near Forest Ecosystems. Environ. Manag. 2025, 75, 2795–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.M. Spatio-Temporal Variation Analysis of Landscape Pattern and Ecosystem Service Value in Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park. Ph.D. Thesis, Hainan University, Haikou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.F.; Yang, X.L.; Zhang, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.L. Differential impacts of “Tianchuang-setting” on rural household livelihood capitals: A case study of Wuyi Mountain National Park. Natl. Parks 2025, 3, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Su, H.Q.; Zhao, X.R. Reform of administrative rights allocation in National Parks: Status, issues and optimization paths. Natl. Parks 2024, 2, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Sang, J.; Peng, M.X.; Sui, Y.T.; Tang, Y.F.; Wang, Y.K.; Li, Z.Y.; Guo, S.L. Practical issues and optimization suggestions in the adjustment process of ecological protection red line assessment. Urban Rural Plan. 2020, 78, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Z.Y.; Tang, X.P.; Du, A.; Zang, Z.H.; Xu, W.H. Scientific construction of National Parks: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Natl. Parks 2023, 1, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.P. Functional positioning and spatial attributes of National Park planning systems. Biodivers Sci. 2020, 28, 1246–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.R.; Zhang, L.; Xu, P.F.; Xing, Y.; Zhu, Y.W.; Zhao, J.W.; Zang, Y. Analysis of integration and optimization plan for nature reserves in Wuyi, Zhejiang. Zhejiang For. Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.; Peng, T.L.; Zhao, Y.T.; Wang, Z.H. Exploration of integration and optimization ideas for Hongjiang nature reserves. Cent.-South For. Investig. Plan. 2021, 40, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.L.; Gu, J.; Ruan, H.H.; Shang, S.B.; Hu, X.Y.; Tang, H.W.; Liu, N. Construction of natural resource classification system under the concept of a new nature reserve system. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 48, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.T.; Chen, X.H.; Ma, Y.W.; Liu, M. Sustainable development research on world natural heritage protection of giant panda habitat in Sichuan. J. Mt. Sci. 2008, 26, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.Z.; Wang, C.L. Nature, development characteristics and policy needs of National Park entrance communities. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.W.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.F. Integrated delimitation of “three zones and three lines” and optimization of national spatial layout: Challenges and methodological considerations. Urban Plan. Forum 2022, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.T.; Lu, S.W.; Ma, Y.P.; Huang, Y.P. Research progress, characteristics and trends of “three zones and three lines” in national spatial planning: A CiteSpace data visualization analysis. In Proceedings of the People’s City, Planning Empowerment—2023 China Urban Planning Annual Conference (20 Master Planning), Wuhan, China, 23–25 September 2023; pp. 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.L.; Wu, D.X.; Zhou, K.; Liao, L.W. Delimitation of urban space and urban development boundaries in national spatial planning. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 2458–2472. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Li, Z.Y.; Li, Q. Evolution characteristics and driving mechanisms of China’s spatial planning system from an ecological perspective. World For. Res. 2020, 33, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Fan, M.X. Exploration of urban development boundary delimitation based on “two plans in one”. Planner 2015, 31, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.G.; Zhang, Q.P.; Kong, X.B.; Duan, X.F.; Zuo, X.Y.; Tan, M.; Zhao, J.; Dong, T. Optimization rules and empirical study of provincial permanent basic farmland layout under the coordination of “three lines”. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 248–257. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, B.; Zheng, X.H.; Luo, H.M.; Shen, J.; Ji, F.F.; Lin, X.H. Integrated delimitation of “three zones and three lines”: Phenomenon analysis, technical logic and the Nanjing experience. Urban Plan. Forum 2024, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gao, J.X. Progress and prospects of China’s natural protected area system construction with National Parks as the main body. Environ. Sci. Res. 2024, 37, 2100–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.M.; Su, Y. From conflict to coexistence: Institutional logic of National Parks in ecological civilization construction in China. Manag. World 2022, 38, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.R.; Ma, S.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.J. Analysis of National Park concession cooperation mechanism from a social embeddedness perspective: A case study of Three-River-Source National Park. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 2276–2293. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.P.; Liu, Z.L.; Ma, W. Research on integration and optimization rules and paths of China’s natural protected areas. For. Resour. Manag. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y.; Su, Y.; Min, Q.W. Boundaries, zoning and land use management of National Parks in China: Lessons from nature reserves and scenic areas. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 1318–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.B.; Guo, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.P.; Kong, D.Z. Exploration of integration and optimization of natural protected areas under the National Park system: A case study of Sanmenxia. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2021, 60, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.F. Discussion and suggestions on several key issues in the integration and optimization of natural protected areas. Biodiversity 2023, 31, 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.Y. The role of communities in governance of China’s national parks and its consolidation and development. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 2310–2334. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhong, F. Resident empowerment and national park governance: A case study of Three-River-Source National Park, China. Land 2025, 14, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B.Y.; Yu, C.Y.; Zheng, J.X.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J.N. Impact assessment of regional adjustment in Shuangbai Dinosaur River Provincial Nature Reserve, Yunnan. For. Investig. Plan. 2021, 46, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, C.J. Survey Report on the Living Environment of Three-River-Source National Park. Urban and Rural Construction. Urban Rural. Dev. 2022, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, J. Review and prospects of human–land relationship studies in the Three-River-Source area: From the perspective of “people, events, time, space”. Adv. Earth Sci. 2020, 35, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Miao, R.; Ren, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, G. Corridor area identification of the Amur tiger and leopard based on National Highway (G331) in Hunchun City. J. Northeast Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 55, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W. Some reflections on the high-quality development of China’s national parks. Nat. Reserves 2025, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.S.; Deng, W.G.; Li, Z.; Kang, X.X. Integration and optimization of natural protected areas: Approaches, responses and discussions. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.G.; Zhou, Y.X.; Ge, Y.X. The Impact of Diversified Ecological Compensation on Rural Household Livelihood Strategy Choice: A Case Study of Households in Ecological Protection Red Line Areas. Rural. Econ. 2024, 502, 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.N. The Impact of Ecological Migrant Urban Integration on Livelihood Strategy Choice: A Case Study of the Three-River-Source Area. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.H.; Hu, Z.M.; Wu, K. Spatiotemporal changes of NDVI and climate driving forces on Hainan Island from 1982 to 2015. Remote Sens. Technol. Appl. 2023, 38, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Hang, L.D. Research on the Implementation Mechanism of Community Participation in Co- Management of Wuyishan National Park. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, F. Research progress and prospects on community co-management in national parks. Green Technol. 2023, 25, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Feng, Y.B. A study on the predicament of community governance and its optimization in the process of national parks’ construction. Adv. Soc. Sci. 2019, 08, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.L.; Li, X. Insights for China from the construction and management experience of U.S. national parks. China Urban For. 2020, 18, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Walliss, J. Transformative landscapes: Postcolonial representations of Uluru-Kata Tjuta and Tongariro National Parks. Space Cult. 2014, 17, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwesaba, D.A.; Daniel, O.E.; Delphine, D.; Benjamin, E. An assessment of land cover change in Gashaka-Gumti National Park, Nigeria. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2023, 11, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.Y. Research on the relationship between ecological zoning control and land spatial planning. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.H.; Zang, Z.H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, S.H.; Cheng, X.G. Current status, problems, and countermeasures of national park zoning and differentiated management. Natl. Parks 2024, 2, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, P.J.; Sherry, S. Implied Limits on the Legislative Power: The Intellectual Property Clause as an Absolute Constraint on Congress. Univ. Ill. Law Rev. 2000, 2000, 1119–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Renkert, S.R. Community-owned tourism and degrowth: A case study in the Kichwa Anangu community. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1893–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagowa, W.N.; Buba, U.N. Emergent strategies for sustainable rural tourism development of Gashaka-Gumti National Park, Nigeria. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 161, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.J.; Huang, R. Nation, ethnicity, and community: Experiences and lessons from the construction of U.S. national parks. J. Ethnol. 2018, 9, 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- James, S. Constructing the climb: Visitor decision-making at Uluru. Geogr. Res. 2007, 45, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A. Gashaka Gumti, Nigeria—From Game Reserve to National Park; Technical Report Rural Development Forestry Network Paper 18d; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.M.; Su, Y.; Wu, B.H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Xu, W.H.; Min, Q.W.; Zhang, H.X. Theoretical reflections and innovative practices of China’s natural protected areas development under the background of ecological civilization construction. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 839–861. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.H.; Xie, M. Governance of natural protected areas with national parks as the main body: Process, challenges, and system optimization. China Rural Econ. 2023, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.; Waterton, E. A journey to the heart: Affecting engagement at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 971–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, S.M.; Meduna, P.N.; Babatunde, A.A. Effects of banditry and illegal logging on conservation in Kainji Lake National Park, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2025, 29, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Specific Connotation |

|---|---|

| Problems arising from land-use planning conflicts | Due to land-use planning conflicts or historical legacies, areas retain specific functions not ecologically coherent with the overall protected area [26,27,28]. |

| Fragmentation phenomena | Within or at the edges of protected areas caused by boundary adjustments or changes in land function due to development projects or human activities [29]. |

| Method for balancing development and protection | Transitional areas between ecological protection and economic development [25], allowing indigenous communities or moderate development while being restricted by ecological policies and infrastructure to ensure ecological functions are not compromised [30]. |

| Three Zones | Three Lines | Original Competent Authority (Former) | Delineation Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological Space | Ecological Protection Red Line | Ministry of Environmental Protection, National Development and Reform Commission | Ecological importance and ecological sensitivity |

| Agricultural Space | Permanent Basic Farm land | Ministry of Land and Resources | Farmland quality and agricultural productivity |

| Urban Space | Urban Development Boundary | Urban–Rural Development, Ministry of Land and Resources | Existing built-up areas, future population, economic targets |

| Three Approaches | Applicable Conditions | Specific Changes | Authorities | Governance Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawal | ① Significant conflicts between ecological protection and human activities ② Relocation feasibility ③ Ecological restoration potential | No change in the boundary; ecological relocation and land-use restrictions | National park authority | Ecological protection |

| Boundary Adjustment | ① Near the boundary ② Clear, concentrated, contiguous, and stable land-use functions | Adjust the national park boundary to formally exclude the area | Local government | Development |

| Tianchuang-setting | ① Deep inside the park, complex land ownership ② Concentrated population ③ Infeasible for immediate withdrawal or boundary adjustment | Retain within the boundary, temporarily not incorporated into unified management | Locally led with national park participation | Balance (future integration) |

| Dimension | China (Tianchuang) | USA (Inholding) | Australia (Uluru-Kata Tjuta Co-managed Community) | Nigeria (GGNP Enclaves) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formation | Follow the “Three Zones and Three Lines” delineation practice to address parcels with frequent human activities and functional conflicts. | Private/state lands enclosed by parks after 19th-century transfers, preserved due to property rights and limited federal funds. | Land rooted in colonial legacy and indigenous rights recognition. | Camps retained through negotiation, shaped by Fulani pastoral traditions and limited state resources. |

| Governance | Government-led model | Dual-track model | Co-management model | Bottom-up negotiated model |

| Challenges | Complex tenure, dense population, weak compensation, unclear responsibilities, poor coordination, trust deficit. | Fragmented property rights, high acquisition costs, state–local policy differences, ecological threats. | Tension between cultural sacredness and tourism; reliance on external funds; governance disputes. | Federal–local conflicts, ancestral land claims, overlapping tenures vs. customary rules. |

| Prospects | Gradual reintegration into unified governance | Slow market-based integration | Strengthening Indigenous governance | Negotiated governance with multi-party collaboration. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tao, R.; Li, T.; Zhang, X. Tianchuang in National Parks of China: Its Concept, Causes, and Consequences. Land 2025, 14, 2275. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112275

Tao R, Li T, Zhang X. Tianchuang in National Parks of China: Its Concept, Causes, and Consequences. Land. 2025; 14(11):2275. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112275

Chicago/Turabian StyleTao, Rong, Tianjiao Li, and Xujiao Zhang. 2025. "Tianchuang in National Parks of China: Its Concept, Causes, and Consequences" Land 14, no. 11: 2275. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112275

APA StyleTao, R., Li, T., & Zhang, X. (2025). Tianchuang in National Parks of China: Its Concept, Causes, and Consequences. Land, 14(11), 2275. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112275