Abstract

Ethnic villages are a multidimensional interactive space between cultural inheritance and modernization; analyzing their spatial reconstruction is fundamental for promoting agricultural and rural modernization and sustainable ethnic development. This study examined ethnic villages in Yongcong Township, Liping Country, from 2016 to 2022, focusing on changes in function and suitability under relocation through a function and suitability evaluation index. Case comparisons were made between administrative villages with high functional and suitability levels and those with resettlement sites. In 2016, ethnic villages followed a growth pattern of Yongcong–Dundong–Guantuan, with low patch density, dispersed distribution, and simple shapes. By 2022, functionality and suitability significantly improved, with an increase in village patches and larger patch areas shifting toward spatial aggregation. Horizontally, land use within reconstruction boundaries diversified by function, whereas vertically, housing structures were reorganized: non-settlement villages retained traditional and modern types while settlement villages combined both, leading to a shift from functional singularity to multifunctionality. Relocation-induced reconstruction may lag local knowledge systems and reduce well-being. Initially, government-led suitability enhancement dominates; gradually, villages increasingly internalize regional identity and competitiveness. By analyzing post-relocation village reconstruction, this study supports the integration of ethnic and regional dynamics, achieving high-quality sustainable development in minority regions.

1. Introduction

The process of urbanization has contributed to regional economic growth, but it has also exacerbated issues such as rural depopulation, aging populations, land wastage, and the decline of traditional economies [1,2]. Simultaneously, policy interventions and urban economic dynamics have channeled capital and technological resources into rural areas [3,4,5]. Globalization and modernization further reinforce technological innovation and social transformation, promoting economic, social, and cultural reconstruction in rural settings [6,7]. These changes have reconfigured the global countryside and altered rural socio-economic environment and spatial patterns [8,9].

A widely debated issue in rural reconfiguration is how to resolve development dilemmas and promote rural revitalization, particularly in multi-ethnic regions such as China [10,11,12,13]. Extensive literature has analyzed socio-economic changes in rural contexts through frameworks such as land use and landscape structural [14], social transformation [15], rural movements and discourses [16,17], rural governance [18,19], and identity politics [20,21]. However, scant attention has been paid to how the built environment in ethnic minority regions can drive broader transformations in social spaces.

In the context of globalization, urbanization, and industrialization, the relationship between humans and nature, rural and urban spaces, and ethnic and non-ethnic areas are being continuously reconfigured [8,22,23,24,25]. At its core, rural spatial reconfiguration aims to optimize and reorganize spatial elements, structures, and functions in a dynamic and evolving manner [10,26,27]. Contemporary research has shifted from a productivist paradigm to post-productivism and neo-productivism [28,29,30]. This transition has prompted agriculture to transcend its singular role, now endowed with multiple missions encompassing production, ecology, and livelihood. Yet, this evolution brings both positive and negative implications for development. Exploring its impact mechanisms is essential to chart a balanced path that reconciles production, ecology, and sustainability. Key themes include theoretical concepts, driving mechanisms, policy trajectories and interactions across land use, ecological governance, industrial change, housing, spatial planning, and resource allocation [10,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

In multi-ethnic regions like China, rural development and transformation entail added complexity due to the need to balance ethnic diversity and ecological protection [22,38,39]. National policy constitutes a pivotal variable influencing the development of ethnic regions, exerting a profound impact on their developmental trajectory and pace. Top-down political and economic transformations and spatial interactions among stakeholders with Chinese ethnic characteristics offer critical insights into spatial restructuring in rural China [40].

The spatial restructuring of ethnic villages is a key dimension of broader rural transformation and plays an integral role in the evolution of the rural regional system [27,41]. Ethnic villages, whether natural or administrative, are typically characterized by a concentrated population of ethnic minorities and distinctive village features. These villages possess unique cultural and social structures, and their spatial configurations reflect traditional residential customs, cultural expressions, and economic activities.

External factors, such as ethnic customs and identity, serve as external drivers influencing the trajectory and direction of reconstruction. In contrast, endogenous elements, including natural resources and land endowments, provide the foundational dynamics that support reconstruction efforts [42]. The restructuring of ethnic villages is thus shaped by both external socio-economic conditions and internal development needs. Through the integration of endogenous and exogenous resource elements, such as land, labor, and capital, and the ongoing optimization of landscape patterns, social networks, governance models, and cultural forms, ethnic villages transform physical, social, and cultural dimensions [43,44,45].

For instance, Mak & Decaudin [46] propose a redefinition of vernacular heritage in Hong Kong by introducing the concept of the commons, thereby offering a new theoretical framework for examining rural revitalization and reinterpreting community-based heritage governance.

The research by Roe et al. emphasizes the increasing importance of the vitality and transformation of ethnic cultural landscapes [47,48,49]. This evolution underlines not only the importance of sustainable management but also the active participation of local communities in conserving cultural heritage. Related research suggests that fulfilling people’s innate need to connect with their environment can enhance their sense of well-being, strengthen regional identity, and stimulate the development of local tourism economies [50,51,52].

China’s 2016 relocation program for poverty alleviation has improved villagers’ living and developmental conditions to a certain extent. However, in the course of urbanization and relocation, indigenous villages have diminished, and their diverse cultural heritage has consequently been lost [53,54,55]. Therefore, relocation involves more than a change in physical space; it represents a comprehensive reconfiguration of cultural, economic, and social structures. Against this backdrop, the spatial reconstruction of ethnic villages has garnered increasing attention within China’s multi-ethnic society. By presenting the distinctive features of this case study’s reconstruction, this research explores diverse approaches to reconstruction alongside their associated challenges. It aims to enrich the case studies within this field of research, thereby providing more valuable reference points for the development of similar regions.

Using Yongcong Township in Liping County, Qiandongnan Miao, and Dong Autonomous Prefecture, Guizhou Province, as a case study, this study constructs an analytical framework for rural spatial reconfiguration by examining land use and architectural structure. It investigates the characteristics and effectiveness of spatial restructuring in ethnic regions under policy intervention. The study is organized as follows: Section 1 introduces the study; Section 2 outlines the theoretical frameworks; Section 3 presents the study and methodology; Section 4 analyses the spatiotemporal evolution of function and suitability levels in ethnic villages within Yongcong Township, as well as the nature and outcomes of spatial reconfiguration; Section 5 offers a discussion; and Section 6 provides conclusions.

By analyzing the reconstruction, processes, and effectiveness of both resettlement and non-resettlement sites under relocation policy, this study contributes to understanding how to integrate relocated populations into social governance, ensure long-term livelihood improvements, and prevent poverty recurrence. The findings also offer valuable insights for ethnic regions in other countries, supporting the modernization and sustainable development of ethnic villages globally.

2. Theory and Ideas

2.1. Ethnic Villages

An ethnic village serves as a repository of national history, cultural heritage, and indigenous wisdom, comprising a spatial fabric interwoven with the environment, inhabitants, and architecture. The cultural heritage of ethnic villages encompasses not only residential architecture and historical sites, but also intangible cultural heritage such as folk customs, local languages, folk arts, and traditional crafts [53]. This heritage holds significant historical, cultural, scientific, artistic, social, and economic value [54,55].

It embodies three interconnected characteristics: materiality, spirituality, and orderliness. Materiality refers to tangible elements such as buildings and the surrounding environment; spirituality encompasses cultural consciousness and traditional values; and orderliness signifies the spatial logic and organization of the village. Materiality acts as the carrier, spirituality forms the essence, and orderliness defines the relationship and arrangement between the two. These three elements are interdependent and collectively shape the spatial identity of ethnic villages. With the intervention of relocation policies, ethnic villages undergo spatial reconstruction, which alters their architecture, environmental settings, and cultural consciousness, thereby transforming their material, spiritual, and orderly dimensions into a redefined spatial structure.

2.2. Boundaries of Village Construction

Village construction is an important component of China’s rural development strategy aimed at improving the quality of life in rural communities. Historically, due to complex terrain and traditional settlement patterns, many villages have lacked clearly defined boundaries, complicating land use planning and local governance. Scientifically delineating village construction boundaries is, therefore, essential for enhancing governance and promoting sustainable rural development. The land within these boundaries (hereinafter referred to as the “boundary”) generally comprises residential land, land for public services and infrastructure, commercial land, non-polluting small-scale industrial land, and reserved land. Industrial land within these zones comprise a mix of primary, secondary, and tertiary functions related to agricultural processing, rural tourism, and logistics services.

2.3. Research Ideas

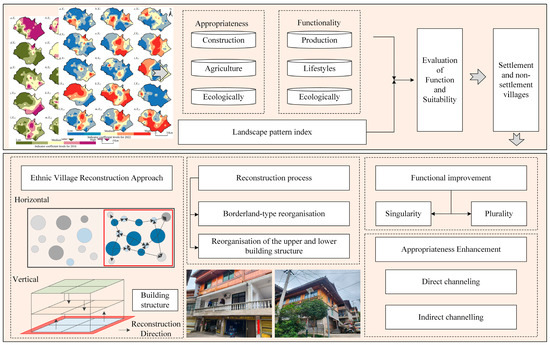

This study explores the status of ethnic villages under policy intervention by evaluating their function performance and spatial suitability. It examines spatial pattern transformations and selects comparative case studies based on significant changes (Figure 1). By analyzing the reconstruction characteristics, processes, and outcomes of different types of ethnic villages from the perspectives of land use and architectural structure within boundaries, the study identifies challenges in village development and proposes insights to support the sustainable development of ethnic communities.

Figure 1.

Technical framework diagram.

3. Study Area, Data, and Methods

3.1. Study Area

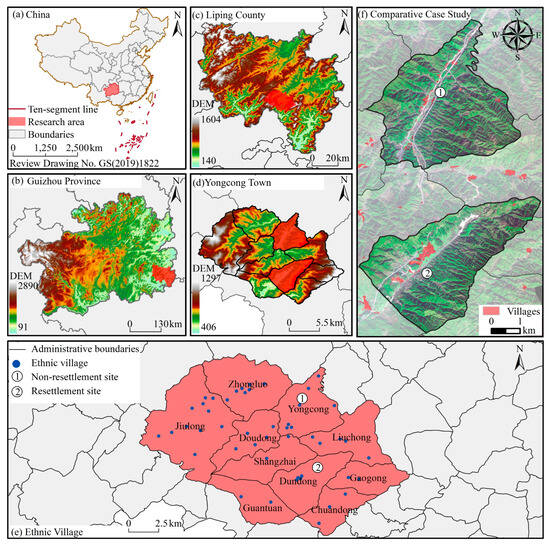

Yongcong Town is located in Liping County within the Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture of Guizhou Province, China. The township government is approximately 42 km from the county seat. Yongcong Town is distinguished by its Dong language and ornate attire as markers of identity, with Dong Grand Songs, Dong Opera and handicrafts serving as its artistic expressions. Its Dong characteristics are exceptionally typical and pronounced, featuring traditional Dong architecture such as drum towers and wind-and-rain bridges (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagram of Dong Ethnic Group Architecture.

As of the end of 2011, Yongcong Town administered 10 villages: Yongcong, Shangzhai, Doudong, Liuchong, Dundong, Guantuan, and Tranhdong, Gaogong, Jiulong, and Zhongluo. A total of 48 villages were surveyed (Figure 3). The main natural hazards in the region include drought, flooding, and freezing conditions. The township-level relocation resettlement site is located in Dundong Village.

Figure 3.

Study area overview.

3.2. Data Sources and Processing

The dataset primarily includes basic geographic information, remote sensing imagery, and social indicators for the years 2016 and 2022.

- AcrGIS 10.8 was used to construct Voronoi diagrams based on village points, which were used to delineate village boundaries for data processing and statistical analysis.

- Remote sensing image data were mainly obtained from the China Resources Satellite Data and Application Center (CRSDC), specifically using GF-6 satellite imagery with a spatial resolution of 30 m. These were primarily used to classify land use within village construction boundaries.

- Data on roads, geological hazards, and land use were obtained from the Natural Resources Bureau of Liping County, Guizhou Province, China. These datasets were used to assess both the accessibility and environmental suitability of ethnic villages.

- Data points for cultural relics and commercial/service facilities were primarily sourced from the Third China Cultural Heritage Census and point-of-interest (POI) data.

Most of these data were supplemented through direct observation and interviews conducted across administrative villages in Yongcong Township between 2024 and 2025. The on-site survey focused on the layout and spatial characteristics of homesteads and their utilization across various spatial types. Observations were recorded using photographs, qualitative descriptions, and mapping techniques.

To investigate reconstruction processes and outcomes, administrative villages with relocation sites were selected for structured interviews. The interview content primarily covers aspects such as Dong ethnic architecture, population, public service facilities, and geological hazards. Each administrative village had 10 respondents, including 10 villagers from the resettlement site and 5 village cadres who were also interviewed. Field surveys revealed that the primary production mode of the village is planting and farming. Roads, water sources, arable land, and gardens serve as foundational elements for agricultural activity. Rice-fish and poultry farming are commonly practiced, with a small portion sold for income and the remainder consumed domestically. Produce is typically sold in Yongcong Town’s local market. Basic services such as shopping, medical care, and education are located in the town center. While some villagers use motorbikes and electric tricycles for access, the majority walk to these facilities. In their leisure time, villagers gather at traditional communal spaces such as drum towers, wind-and-rain pavilions, theaters, and fitness squares for communication and recreation.

Based on field survey findings and data availability, the following indicators have been selected for evaluation indexes for functional and stability levels of ethnic villages, adopting a functional perspective of the ‘three lifestyles’:

- 5.

- Production function indicator: Average distances from village patches to roads, water sources, cultivated land, and gardens; average travel time to the town center.

- 6.

- Living function indicators: Average travel time to commercial and service facilities, access to immovable cultural relics, degree of social interaction, village area.

- 7.

- Ecological function indicators: Influence of geological hazards and proportion of forest and grassland coverage.

For appropriateness evaluation, indicators were categorized into construction, living, and ecological dimensions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation indexes for functional and stability levels of ethnic villages.

3.3. Research Methods

3.3.1. Evaluation Methods of Functional and Suitability of Ethnic Villages

We aim to better show the reconstruction characteristics, process, and effectiveness of ethnic villages under the intervention of relocation, and to understand the status of functional improvement and suitability enhancement.

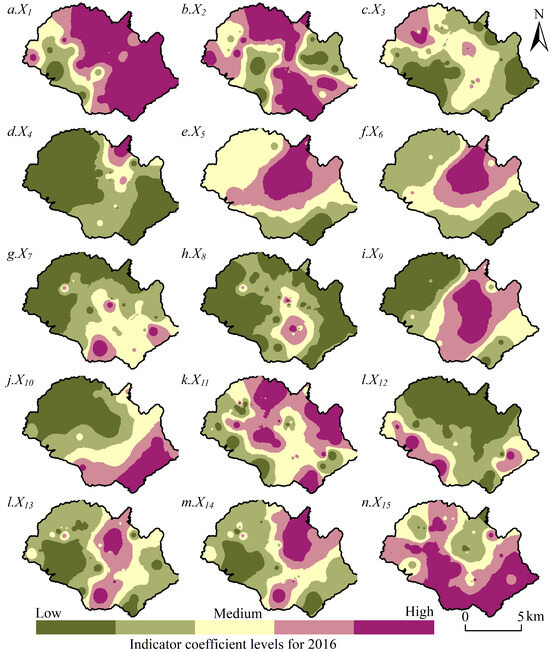

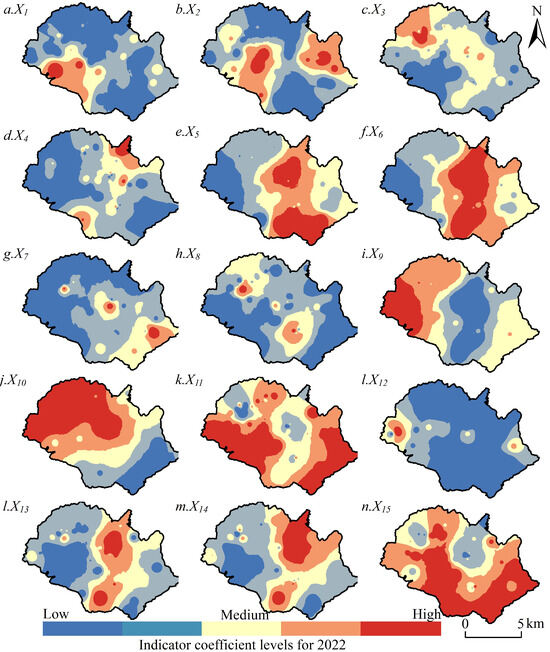

The evaluation indicator systems for the functional stability levels of ethnic villages in 2016 and 2022 were employed to assess changes in functionality and appropriateness (Figure 4 and Figure 5). To ensure comparability across indicators of varying scales, values were standardized using the extreme difference method. The entropy weighting method was then employed to objectively assign indicator weights. These weighted indicators were used to calculate the overall functionality and appropriateness scores of ethnic villages and to analyze their temporal and spatial evolution.

Figure 4.

Index coefficient grade for 2016.

Figure 5.

Indicator coefficient levels for 2022.

The formula used for calculation is shown as follows:

- (1)

- Data standardization. First, all indicators in the functional stability evaluation index system of ethnic villages are standardized by standard deviation:

In the formula, x represents the mean value of indicator j; Sj denotes the standard deviation of indicator j; and xij stands for the standardized value of indicator j. Here, xij refers to the original value of the i-th sample under the j-th indicator. To effectively address the impact of negative values, a shift operation is applied to the standardized values: Xij = xij + A, where A represents the shift magnitude.

- (2)

- Calculation of index entropy. The entropy value of the first index can be expressed as:

- (3)

- Calculation of the coefficient of differentiation of the jth index:

- (4)

- Determination of index weight:

- (5)

- Calculation of composite index:

The functional and stability levels of ethnic villages are shown by Equation (5), and the spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of functional and adaptive levels of ethnic villages from 2016 to 2022 are explored, so as to select typical cases.

3.3.2. Landscape Pattern Index

Vector land use data for Yongcong Township in the years 2016 and 2022 were obtained and categorized into four land use types: unused land, agricultural land, village land, and other construction land outside villages. Using the Vector Landscape Index Calculator (VecLI 2.0) and Fragstats V4.2 software, the following indices were calculated: Number of Patches (NP), Patch Density (PD), Largest Patch Index (LPI), Edge Density (ED), Mean Patch Area (AREA_MN), and Landscape Shape Index (LSI). These indices were used to assess and map the village structure and to track changes in spatial patterns corresponding to functional and suitability evolution over the two time periods.

3.3.3. Case Selection and Comparative Analysis

To better understand the characteristics, processes, and effectiveness of ethnic village reconstruction under the relocation policy, two typical administrative villages were selected for comparative analysis based on high functionality and suitability scores. Dundong Village (a resettlement site) and Yongcong Village (a non-resettlement site) were chosen as case studies. The analysis explores materiality, spirituality, and orderliness under policy intervention, focusing on the restructuring of building layouts within village boundaries and residential areas. This helps evaluate the reorganization methods and the resultant improvements in function and suitability.

4. Results and Analyses

4.1. Functionality and Suitability Evaluation and Spatial Structure Evolution Characteristics of Ethnic Villages

4.1.1. Functionality and Suitability Evaluation

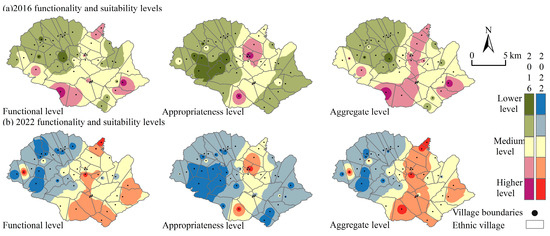

Figure 6 illustrates changes in functionality and suitability levels in Yongcong Town between 2016 and 2022. Functionality levels increased during this period, alongside village expansion under the relocation policy. However, western villages, more affected by geological hazards, showed lower functionality levels compared to their eastern counterparts. Suitability levels displayed a declining trend overall. Spatially, a belt-like growth and diffusion pattern was observed across Yongcong Village, Dundong Village, and Guantuan Village.

Figure 6.

Yongzheng town functionality and suitability level distribution.

Specifically, in 2016, there were a total of 122 village patches in Yongcong Township, accounting for 0.98% of the township’s total area, 16.19% of its cultivated land, 0.80% of its garden land, and 0.013% of the established town. Field investigations revealed that Yongcong villages primarily used arable land, grasslands, and gardens for planting and farming, producing special products, such as rice-fish, tea, and vegetables. Arable land was concentrated in Pingyang and Jiguo villages; grasslands were prominent in Fear Cave, Pingmo, and Shanggao Gong; and garden land was most extensive in Pear Garden and Liangdao Shui. Functionality levels were highest in the Fear Cave and Shanggao Gaog villages. Although Pingyang and Jiguo had a larger share of arable land, their functionality scores were lower due to proximity to geological hazard sites.

Based on agricultural, construction, and ecological suitability data, Yongcong Village, serving as the township’s administrative center, includes commercial streets, residential areas, and public service facilities (e.g., schools and health centers). While small areas of farmland remain nearby to supply local needs, the proportion of arable land in Yongcong Village Street is lower than in Xinzhai. Accordingly, its agricultural suitability is weaker, although construction suitability is higher. Guantuan Village, a traditional Dong embroidery handicraft village, initiated support for an intangible heritage workshop under the relocation policy in 2016. However, due to limited market reach, its construction suitability remains lower than that of Yongcong Village and Xinzhai. Agricultural suitability in Guantuan is comparable to that of Yongcong Village. Overall, suitability levels are concentrated in Pipe Tuan, Yongcong Village Street, and Xinzhai.

By 2022, the number of village patches in Yongcong Township has increased to 513. Compared with 2016, the village area expanded by 0.32%, arable land declined by 6.23%, garden land increased by 0.11%, and the area designated as townships grew by 0.10%. Following the relocation intervention, Yongcong experienced significant urban expansion, with improvements in the road network and commercial service infrastructure. These changes notably enhanced the human environment and accessibility.

Jiulong Village, categorized as a tourist-oriented village, contains potential geological hazard zones, resulting in a low functionality score. In contrast, Gao Ya Village, located farther from hazard zones, maintains livelihoods based on rice cultivation, orchard farming, and livestock rearing. With the village’s expansion of tea plantations and the implementation of a “tea-tourism integration” strategy, garden and grassland areas have increased. The proportion of garden land in Pear Garden and LiangDaoshui Villages, however, has not significantly changed since 2016, although their garden land area remains larger relative to other villages.

In terms of suitability, many areas within Jiulong (e.g., Pingmo, Gibian) and Doudong (e.g., Shihua) fall within the ecological protection red line, limiting both agricultural and construction potential. Despite these restrictions, overall suitability levels improved compared with 2016.

In 2016, the road was concentrated in the northeast of Yongcong Township. Following the relocation intervention, both the width and number of roads increased, extending progressively to the southeast. This improved inter-village connectivity accelerated the flow of resources and enhanced public service accessibility. Consequently, the combined functionality and suitability levels showed a corridor-like growth pattern extending from Yongcong Village through Dundong Village to Guantuan Village.

4.1.2. Characteristics of the Evolution of the Spatial Structure of Ethnic Villages

The results indicate that (Table 2), before policy intervention, ethnic villages exhibited a lack of scale effect and homogeneity in spatial form. These limitations made it difficult to support improvements in rural functionality and suitability. Following policy intervention, the spatial configuration of village clusters improved significantly: the number of patches increased to 513, and the total area expanded by more than 0.32%.

Table 2.

Landscape pattern index of ethnic villages in 2016 and 2022.

Although the rise in patch number could increase boundary complexity and landscape heterogeneity, evidenced by the increase in ED, this diversification in layout also enhances the rational allocation of public services. Furthermore, the increase in the LPI, from 0.1199 to 0.1473, suggests a strengthening dominance of a few larger patches, which fosters economies of scale. This supports more efficient resource use and extends the benefit of functional and spatial reconfiguration to a greater number of residents, thereby contributing to the region’s overall development.

The simultaneous decline in AREA_MN and the increase in PD and LSI reveal a dual trend: while the production, living, and ecological functions of ethnic villages are improving, and suitability levels are rising, the increasing distance between patches the controlled growth of dominant patches help prevent spatial overconcentration. This promotes horizontal development and effectively enhances the integration of functionality and suitability across ethnic villages.

Geographically, the areas that exhibited the greatest increases in comprehensive suitability can be categorized into two types. The first is Dundong Village, a resettlement site characterized by traditional farming and home to the largest number of immovable cultural relics and distinct ethnic cultural features. The second is Yongcong Village, the administrative center of the township, which possesses the most developed accessibility and public service infrastructure. Its economic base integrates commercial services with agricultural activities.

In conclusion, Dundong and Yongcong Villages demonstrate the most prominent patterns of spatial reconfiguration. These cases offer valuable scientific reference points for comparative analysis and serve as models for the integrated development of other ethnic villages and township-level regions.

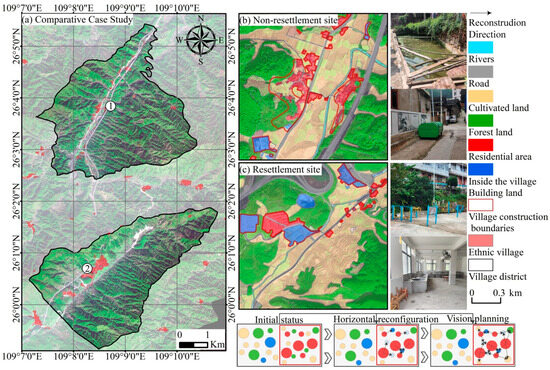

4.2. Reconstruction of Ethnic Villages: Functional Improvement

The village construction boundary refers to the designated area for future village development as defined in territorial spatial planning. This boundary aims to regulate spatial layout, protect arable land and ecological resources, and prevent unregulated expansion. Land use categories within the boundary form the foundation of village development. Over time, a pattern of horizontal outward extension and internal land use conversion has emerged.

The residence base plays a core role in supporting rule living. Therefore, the method of reconstruction and its effectiveness significantly affect both the livelihood and production activities of residents. Originally serving a single purpose, residential use, the house site has evolved into a multifunctional space. Against the backdrop of rapid urbanization, homesteads now not only serve as living quarters and spaces for family interaction, but also support ecological activities such as vegetable gardening and productive functions like poultry farming—particularly for households whose primary labor has shifted outside the home. Homestead vegetable cultivation represents not merely a supplementary source of household food, but a strategy to reduce living costs, enhance livelihood diversification, and bolster resilience against market risks. From a spatial functional perspective, this represents an extension of residential space into productive functions. It embodies the micro-scale realization of “production-living” composite utilization within rural spaces, thereby achieving functional enhancement and optimization of residential units. These diverse uses reflect the co-existence of living, production, and ecological functions within residential land.

Yongcong Village, as the township’s administrative center, is characterized by a mix of commercial, residential, and public service land uses. Facilities such as farmers’ markets, health centers, and schools are concentrated in the town center, alongside active commercial activity on market days. Despite its urban core, surrounding farmland is retained for vegetable cultivation, sustaining a degree of self-sufficiency. This meets residents’ subsistence needs while pursuing a higher quality of life. According to surveys of Yongcong Village residents, there is a strong demand to add new facilities, such as vegetable markets, fitness plazas, and public canteens, within the village construction boundary. These enhancements to the rural service infrastructure raise the overall functional level of the village. As land is reclassified within the boundary, arable and grassland areas are being gradually converted into commercial land, increasing patch diversity and functional complexity.

Dundong Village, serving as a resettlement site, has taken in 71 households (328 individuals) from Chuandon Village, including the sub-village of Zaikengzhai and Yabuzhai. Each household was allocated approximately 90 m2 of building space, while the resettlement site also included 380 m2 for public service and infrastructure. The original ethnic villages, such as Zaikengzhai, were located deep in the Liubai Mountains, where transportation was limited and access to town services was poor. Housing was primarily composed of hazardous wooden structures. In contrast, the resettlement area includes modern facilities such fitness plaza and public canteens. As the boundary of the village expands, the land use function has evolved from a primarily residential role to a more integrated combination of living, production, and ecological uses, contributing to overall functional diversification (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Horizontal reconfiguration map of the resettlement and non-resettlement villages.

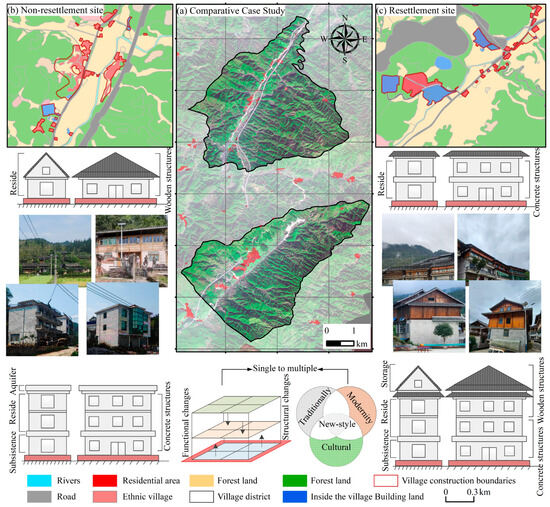

The rural residential base ensures that each household has access to housing. The principle of “one household, one house” remains the foundation of residential land management, and recent policies strictly enforce this rule, prohibiting excessive construction and the development of multiple homes per household. However, due to urbanization and population outflow, some rural homes are now large but underutilized, leading to resource inefficiencies. In this context, vertical reconstruction has been implemented to improve the functionality value of the residential base.

Yongcong Village features two main types. The first includes traditional ethnic-style homes, typically 1–2 stories, with wooden frames and tiled roofs, primarily serving residential purposes. The second includes a modern multi-story concrete building, generally 2–3 stories, with mixed functions: the ground floor often supports commercial or livelihood activities, while the upper floors are for residences. Roof spaces are often adapted for rainwater storage (Figure 8). This approach has proven particularly prevalent and practical within the context of China’s large-scale urbanization and poverty alleviation relocation initiatives. As a significant national strategy, the relocation policy for poverty alleviation has moved millions of residents from remote mountainous areas with harsh natural conditions and fragile ecosystems to newly constructed towns or communities. These modern settlements typically comprise multi-storey residential buildings. Installing rainwater harvesting systems on the rooftops of these structures provides a non-potable water source for community greening irrigation, toilet flushing, and cleaning, effectively alleviating pressure on the water supply network.

Figure 8.

Vertical reconfiguration of the resettlement and non-resettlement villages.

At the Dondong Village resettlement site, hybrid structures combined these two models. Buildings are commonly 3–4 stories, with concrete construction on the lower floors and architecture. Functional zones are vertically organized: the lower levels support livelihood activities, the middle levels serve as living spaces, and the upper levels are often used for storage. This spatial organization represents an adaptive modification to the local climate, topography, and modes of production and daily life. Primarily, heavy and unclean production materials are situated on the ground floor, core living spaces occupy the middle level for enhanced security and comfort, while lightweight and infrequently used items are placed on the upper floor. The integration of murals and stilted houses with traditional architecture transforms these deliberately preserved structures into distinctive village landscapes when innovatively incorporated into new developments. This unique architectural culture and spatial form constitutes the core tourism resource for developing rural tourism and creating ethnic-themed guesthouses. This process continually reinforces villagers’ recognition and pride in their cultural distinctiveness through everyday spatial experiences and cultural displays for visitors, thereby subtly strengthening cultural identity. It indirectly boosts household income for villagers. Architectural elements also reflect local ethnic culture, contributing to cultural preservation and socioeconomic development. These multifunctional structures support household income, improve food storage, and enhance the cultural identity of the village.

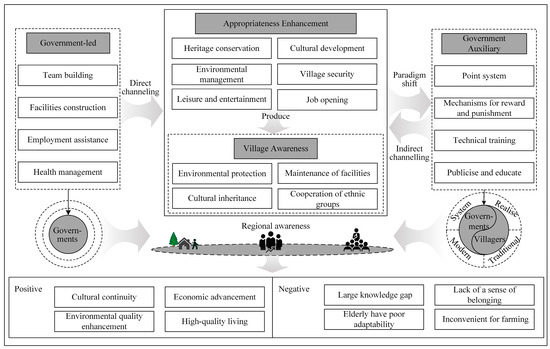

4.3. Reconstruction of Ethnic Villages: Improvement of Suitability

The horizontal and vertical reconstruction of ethnic villages has improved their overall functionality, and the point-by-point process of suitability enhancement is illustrated. The proportion of Yongcong Village within the established town has increased by 0.107%. Commercial and service facilities are mostly concentrated along the streets of Yongcong Village, forming a relatively boundary zone. These facilities are located on the periphery of the town and evolve in suitability alongside the town’s development.

In more remote villages, where original residential sites are limited by functional constraints, daily life centers on agricultural production and home-based rest. The main form of leisure involves traveling to the town to participate in activities. This dynamic encourages occasional interaction between villagers and town residents or between neighbors. However, geographical isolation presents these villages with multiple challenges in accessing policy support, participating in socio-cultural exchanges, and benefiting from environmental governance.

Through horizontal reconstruction, public service facilities, such as a community cafeteria, fitness plaza, and a Rain and Wind Pavilion, have been established to address the lack of social spaces. These additions promote interaction among the village’s productive, residential, and ecological functions, leading to both functional improvement and suitability enhancement.

In resettled ethnic villages such as the Dundong site, villagers face challenges in adapting to unfamiliar environments. Among these, livelihood insecurity remains a key issue. Support workshops have played a vital role in addressing this concern. The resettlement site includes more comprehensive public services and infrastructure.

Vertical reconstruction, combining ethnic architectural elements, has been used to build a culturally unified appearance. However, the use of an upper wooden structure presents safety concerns. Therefore, fire prevention planning plays a crucial role in protecting both physical safety and the continuity of cultural heritage.

In the initial stage, government efforts have focused on assistance and community engagement. Activities are organized, and volunteer teams are established to help villagers adapt to new environments and practices, thereby enhancing functionality and suitability (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Suitability enhancement framework.

In the later stage, the introduction of a points-based village evaluation system has indirectly fostered regional awareness. Villages are now more likely to take initiative in maintaining facilities and the local environment, thereby contributing to ethnic unity and the creation of a livable, culturally rich community.

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy Intervention and the Enhancement of the Functionality and Appropriateness of Ethnic Villages

Liu and Li [2] point out that top-down rural development policies often fail to deliver the intended outcomes because they do not fully account for the unique characteristics of different rural areas. This study shows that, under the influence of relocation policies, the functionality and appropriateness of ethnic villages can be significantly improved by upgrading infrastructure, leveraging local resources, and developing rural specialty industries.

In 2016, the per capita disposable income of rural residents in Yongcong Township was 6805 yuan. As of 2024, the figure has increased to $2023.55. By the end of 2024, all administrative villages in Yongcong Township will be equipped with hardened roads, bus services, and postal delivery infrastructure. These developments have substantially improved overall infrastructure conditions in the township.

With strong support from relocation policies, Yongzong Township has seen marked progress in industrial development, infrastructure construction, and public services, which has contributed to improvements in village functionality and suitability.

For remote ethnic villages, breaking the cycle of poverty and underdevelopment remains difficult without strong policy support. Rapid urbanization and increasing globalization have contributed to economic decline and social fragmentation in ethnic areas [56,57].

Poverty alleviation remains the central objective of the Chinese government’s rural development. From the national to the local level, the government has developed the organizational and implementation capacity to provide targeted assistance to ethnic villages based on their distinct poverty profiles. This targeted intervention has effectively enhanced the resilience of impoverished ethnic villages and improved their capacity for recovery [58].

This study identifies a key mechanism in the implementation of relocation policies: the guiding mechanism. Direct guidance, based on the administrative village system, helps awaken ethnic conscientiousness and activate the internal development capacity of ethnic communities. Indirect guidance, on the other hand, relies on the establishment of public service facilities to foster autonomous management and growth.

Through the stimulation of external policy forces, the architectural functions of ethnic villages have expanded. These developments have promoted the emergence of self-accumulation and self-development capabilities, significantly enhancing the villages’ resilience capacity to adapt to risks. Furthermore, the empirical results indicate that policy intervention primarily enhances the functionality and appropriateness of ethnic villages rather than their capacity for transformation. This outcome is closely tied to China’s emphasis on developing specialty industries, diversifying income sources, and encouraging localized development as a means of building adaptability in ethnic areas.

In contrast to policies in several Southeast Asian countries, which aim to establish protected zones and increase the resistance of ethnic regions to external shocks, China’s approach focuses on strengthening economic capacity and local development [59,60]. Another key finding suggests that the impact of relocation policy interventions varies among villages. The effects are more pronounced in areas with weaker economic foundations and higher exposure to poverty and disasters. Therefore, policy intervention has led to a significant improvement in the level of functionality and appropriateness of ethnic villages.

5.2. Reconstructing the Characteristics of Ethnic Villages and the Awakening of Ethnic Consciousness

Existing research on ethnic villages has largely concentrated on the benefits associated with architectural features. However, it is also crucial to examine how ethnic villages evolve under external influences, particularly when considering architectural structure and land use types from the perspective of traditional ethnic village characteristics. This approach contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the overall development trajectories of ethnic villages.

This study draws on both horizontal and vertical reconstruction frameworks to observe how the function of ethnic villages has transitioned from unitary to diversified. Horizontally, land use within the designated construction boundaries has become increasingly diversified. A functional system integrating production, ecological preservation, and daily life has emerged, thereby enhancing the villages’ utility. Furthermore, the expansion of communal spaces has fostered platforms for inter-villager communication, which in turn has contributed to the formation of platforms of regional ethnic consciousness.

Vertically, reconstruction alters the architectural structure of residential areas. The integration of upper and lower components combines traditional and modern architecture, allowing for diversified residential and community functions. During the process of urbanization, these architectural developments have helped preserve and promote aspects of national culture [6,47].

This study highlights the different development trajectories and functional benefits of ethnic villages, contrasting with earlier research that has predominantly focused on vertical aspects, such as the above- and below-ground architectural structures while overlooking horizontal changes and the critical role of ethnic consciousness [25,61].

5.3. Recommendations

Econometric validation, field research, and theoretical analysis indicate that China’s relocation policy has significantly improved the functionality and appropriateness of ethnic areas. Based on the findings of this study, integrating practical implementation with policy frameworks facilitates institutional innovation. This approach influences subsequent poverty alleviation policies, shifting the focus from subsistence-level support towards quality enhancement and fostering organizational diversification. Consequently, the following recommendations are proposed for future research and policy formulation:

- Strengthen government-led direct guidance by continuing to provide policy support to low-income households and underdeveloped regions. A long-term mechanism should be established to address relative poverty, alongside a monitoring system to prevent the recurrence of poverty.

- Further leverage the role of ethnically distinctive industries as key drivers of development. This includes enhancing the adaptability of local economic systems. In the context of the growing smart economy, policymakers should promote the integration of digital technology and traditional industries to build a sustainable digital industrial ecosystem in ethnic regions.

- Align development plans with villagers’ preferences by integrating traditional ethnic architectural elements with modern building designs. Village planning and renovation should aim to accentuate local characteristics while advancing an “industry + tourism” development model. This would help increase the resilience and transformation capacity of local economies, strengthen ethnic consciousness, and support the protection and exchange of cultural heritage.

In addition, the industrial development of ethnic regions must consider both agriculture and ethnic-specific industries, rather than prioritizing secondary and tertiary sectors without local relevance. Future research should focus both on the characterization and diversification of industrial structure. This includes balancing domestic and international market development and selectively promoting industries that are resource-aligned and can involve and benefit local farmers.

Will ethnic villages be impacted positively or negatively under relocation policies? Field investigations suggest that the outcomes depend on whether the policy emphasizes mere relief or guided development. Under China’s development-oriented poverty alleviation strategy, villagers are not only lifted out of poverty but also empowered through enhanced self-development capacity and motivation. The approach fosters endogenous village development while continuously adapting spatial structures to evolving needs.

However, if poverty alleviation is limited top-down resource inputs and neglects the agency of villagers, the lack of intrinsic capacity may lead to long-term fragility. Upon policy withdrawal, communities with a dependency mindset may face increased vulnerability, hindering sustainable self-reliant development.

Therefore, while financial assistance remains crucial, greater emphasis must be placed on transforming villagers’ attitudes, nurturing ethnic regional identity and solidarity, and implementing both direct and indirect guidance mechanisms. These efforts can support skill acquisition and strengthen the internal development capacity of ethnic villages.

6. Conclusions

Under the relocation policy, ethnic villages face both diversified opportunities and significant challenges, making it crucial for them to adapt to evolving development conditions. Investigating the characteristics, processes, and effectiveness of village reconstruction in response to external stimuli is critical to supporting their long-term progress. This study evaluates the functional and suitability levels of ethnic villages to determine their comprehensive development status, identify typical cases, and compare resettlement with non-resettlement villages. These comparative analyses aim to uncover different reconstruction pathways and more scientifically represent the characteristics and effectiveness of the reconstruction process.

The Voronoi diagram, generated based on the actual geographical locations of the villages, provides a division method unconstrained by administrative boundaries and purely grounded in spatial distance. It visually illustrates the theoretical geographical hinterlands or spheres of influence served and affected by these villages. Although construction boundaries across villages vary, the results remain consistent with actual conditions. The use of the Voronoi method to delineate village boundaries is thus considered feasible. Given the limitation of villagers’ subjective opinions as research data, a case study approach was adapted to maintain objectivity and analytical clarity.

This study focuses on Yongcong Township, located in Liping County, Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture, Guizhou Province, China. It analyses spatial and temporal changes in functionality and suitability levels and the evolution of spatial landscape patterns between 2016 and 2022. Typical and resettlement villages were identified based on functionality and suitability indices, and a comparative analysis of different reconstruction types was conducted to examine their characteristics, processes, and impacts. Although this period is short, it captures a phase of rapid transformation driven by China’s targeted rural development policies.

The key findings are as follows: relocation initiatives have contributed to the development of new settlements in previously fragile villages. Two types of reconstruction, horizontal and vertical, have led to improved functionality and enhanced suitability. As a result, villagers’ overall well-being has significantly improved. However, the study also reveals certain limitations. In some cases, relocation, combined with the outmigration of family members and the reliance of those remaining on agriculture, has created mismatches between farmer agricultural lifestyles and current conditions. For example, relocated households may now live further from their farmland, and changes in daily routines have exposed gaps between local residents’ existing knowledge, technological capacity, and evolving needs. Although aggregate development levels have improved, these mismatches have, in some cases, reduced the sense of well-being.

Future research should therefore focus on enhancing villagers’ skill levels and fostering a stronger sense of belonging, to achieve a sustainable, culturally sensitive development model. This model should balance ethnic identity with modernization and offer a more harmonious and context-specific approach to village reconstruction.

However, relying only on a single ethnic region limits the generalizability of the findings. Supplementary studies across diverse ethnic areas are necessary to develop a more comprehensive reconstruction mechanism and theoretical model. In addition, attention must be paid to the risk of excessive reconstruction, such as the commodification of ethnic villages or the erosion of traditional cultural practices. Regulating funding flows and the development of specialized industries, encouraging creativity and innovation, and balancing development priorities with cultural preservation should be central to future research efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, J.C. and L.D.; writing—original draft preparation, X.C.; visualization, F.Y.; supervision, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42361028, 42271228), the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education (24YJC630028), the Humanities and Social Science Research Project of Guizhou Provincial Department of Education (24RWZX007).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRSDC | China Resources Satellite Data and Application Center |

| POI | Point-of-interest |

| ED | Edge Density |

| LPI | Largest Patch Index |

| LSI | Landscape Shape Index |

| NP | Number of Patches |

| PD | Patch Density |

References

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Ives, C.D.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y. Modes and practices of rural vitalisation promoted by land consolidation in a rapidly urbanising China: A perspective of multifunctionality. Habitat Int. 2022, 121, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Li, Y.H. Revitalizing the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosworth, G.; Bat Finke, H. Commercial counterurbanisation: A driving force in rural economic development. Environ. Plan. A 2020, 52, 654–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilley, L.; Gkartzios, M.; Kudo, S.; Odagiri, T. Hybridising counterurbanisation: Lessons from Japan’s Kankeijinko. Habitat Int. 2024, 143, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkartzios, M. ‘Leaving athens’: Narratives of counterurbanisation in times of crisis. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Visualization system of Hlai ethnic village landscape design based on machine learning. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 10001–10011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural Geography: Processes, Responses, and Experiences in Rural Restructuring; SAGE: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M.; Fois, F.; Heley, J.; Jones, L.; Onyeahialam, A.; Saville, S.; Welsh, M. Assemblage, place and globalisation. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2021, 46, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Tu, S.; Ge, D. The allocation and management of critical resources in rural China under restructuring: Problems and prospects. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Lowe, P.; Whatmore, S. Rural Restructuring: Global Processes and Their Responses; Fulton: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. Rural; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, H.; Ma, L.; Tu, S.; Li, Y.; Ge, D. Analysis of rural economic restructuring driven by E-Ommerce based on the space of flows: The case of Xiaying village in central China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, Z. The changing face of the Czech rural landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 31, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charatsari, C.; Papadaki-Klavdianou, A. First be a woman? Rural Development, social change and women farmers’ lives in Thessaly-Greece. J. Gend. Stud. 2017, 26, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosset, P.M.; Martínez-Torres, M.E. Rural social movements and agroecology: Context, theory, and process. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 1095080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Social movements and rural politics. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.; Goodwin, M.; Pemberton, S.; Woods, M. Partnerships, power, and scale in rural governance. Environ. Plann. C Gov. Policy 2001, 19, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, M. The governance of rural areas: Some emerging research issues and agendas. J. Rural Stud. 1998, 14, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.M. The fruit of difference: The rural-urban continuum as a system of identity. Rural Sociol. 1992, 57, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, K.; Gaddefors, J.; Lindgren, M. Provoking identities: Entrepreneurship and emerging identity positions in Rural Development. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2016, 28, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornel-Vázquez, R.; Iglesias, E.; Loureiro, M.L. Adoption of nature based solutions for energy transition in rural households of Northern Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, G.; Yu, X.; Li, Y. Social network dynamics in rural public spaces of multi-ethnic settlements: A case study from Tongren, China. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 102, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J. Co-Constructing the Countryside: Hybrid Networks and the Extensive Self; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zévl, J.J.; Špačková, P. ‘My Sweet Little Village’: Central settlement system in socialist Central Bohemia. J. Maps 2025, 21, 2453102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ding, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. A quantitative investigation of the passive features in vernacular Mu Nia Tibetan houses. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Tu, S. Rural restructuring: Theory, approach and research prospect. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkartzios, M.; Lowe, P. Revisiting neo-endogenous rural development. In The Routledge Companion to Rural Planning; Scott, M., Gallent, N., Gkartzios, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.A. From productivism to post-productivism… and back again? Exploring the (un)changed natural and mental landscapes of European agriculture. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2001, 26, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A.; Burton, R.J.F. ‘Neo-Productivist’ agriculture: Spatio-temporal versus structuralist perspectives. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 38, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkartzios, M.; Scott, M. Residential mobilities and house building in Rural Ireland: Evidence from three case studies. Sociol. Ruralis 2010, 50, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkartzios, M.; Scott, M. Placing housing in rural development: Exogenous, endogenous and neo-endogenous approaches. Sociol. Ruralis 2014, 54, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Tang, Y.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zheng, Y. The impact of land consolidation on rural vitalization at the village level: A case study of a Chinese village. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Woods, M.; Zou, J. Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing Balance’s land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, S.; Tao, T.; Gong, M.; Bai, J. Spatial reconstruction of rural settlements based on livability and population flow. Habitat Int. 2022, 126, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zoh, K. Analysis of the spatial distribution characteristics and driving factors of ethnic-minority villages in China using geospatial technology and statistical models. J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 21, 2770–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H. Rural restructuring in China: Theory, approaches and research prospect. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggart, K.; Paniagua, A. What rural restructuring? J. Rural Stud. 2001, 17, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Precarious rural cosmopolitanism: Negotiating globalization, migration and diversity in Irish small towns. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 64, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Wen, Z.; Fan, J. Rural spatial restructuring: Theoretical research progress and framework construction. Trop. Geogr. 2020, 40, 765–774. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Bai, X.; Ravenscroft, N. Counterurbanization, gentrification and the potential for rural revitalisation in China. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, T. Quantitative analysis of spatial genes in traditional villages: A case study of Korean traditional villages in northeast China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 2577–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, R.; Li, S. Rural development transformation and social governance from the perspective of specialization: A case study of Ruiling Village in Guangzhou City, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H. Land consolidation: An indispensable way of spatial restructuring in rural China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Long, H.; Tu, S.; Jiang, Y. Theoretical analysis and models of rural industrial restructuring from the perspective of rural revitalization: A case study in Guangxi. Prog. Geogr. 2024, 43, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, V.W.S.; Decaudin, M.C. Village (Re)commoning: Rethinking Hong Kong’s rural built heritage as commons. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, W. Cultural geography meets architectural typology: A mixed-methods study of traditional Bayu dwellings in Southwestern China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, M.H.; Taylor, K. New Cultural Landscapes; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K.C.A.S.; Nora, M. Conserving Cultural Landscapes: Challenges and New Directions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.B.; Green, G.T. Ecotourism and natural resource conservation: The ‘potential’ for a sustainable symbiotic relationship. J. Ecotourism 2016, 15, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, E.Q.; Ip, R.; Wang, K. How does rural tourism experience affect green consumption in terms of memorable rural-based tourism experiences, connectedness to nature and environmental awareness? J. Hosp. Tourism Manag. 2023, 54, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecka, M.; Prince, S.; Boley, B.B. Resident connection to nature and attitudes towards tourism: Findings from three different rural nature tourism destinations in Poland. J. Sustain. Tourism 2023, 31, 664–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrini, M.; Jon, B.; Paul, M.; Alberto, Z.; Yvonne, R. “Understanding Sustained Community Engagement: A Case Study in Heritage Preservation in Rural Argentina”. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 26 April–1 May 2014; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA; pp. 2675–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.Q.; Wang, M.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhang, S.N. Configuring Creativity: Promoting Cultural Inheritance-Based Innovation in Heritage Tourism Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Ma, L.; Zhou, W.; Dai, L. Traditional village digital archival conservation: A case study from Gaoqian, China. Arch. Rec. 2023, 44, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakderi, C.; Tasopoulou, A. Regional economic resilience: The role of the national and regional policies. Eur. Plann. Stud. 2017, 25, 1435–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, O.; Drewes, E.; Van Aswegen, M.; Malan, G. A policy approach towards achieving regional economic resilience in developing countries: Evidence from the Sadc. Sustainability 2021, 5, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilling, J.; Jones, S.; Duncan, A. Sector approaches, sustainable livelihoods and rural poverty reduction. Dev. Pol. Rev. 2010, 3, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitenhuis, Y.; Candel, J.J.L.; Termeer, K.J.A.M.; Feindt, P.H. Does the common agricultural policy enhances farming systems’ resilience applying the resilience assessment tool (Resat) for a farming system case study in the Netherlands. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibe, M.; Tomita, S.; Umezaki, M. Divergence in nutritional intake and physical activity patterns among households in a village of ethnic minorities in Northern Laos at the initial stage of health transition. Hum. Ecol. 2022, 50, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Duan, Y.; Li, D. Hani mushroom house building adaptability. Buildings 2023, 13, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).