Abstract

In order to tackle the problems caused by invasive alien plant species, it is important to know what the main groups that have the largest influence on the spreading of the species, know and think about them. Nation-wide questionnaire surveys were carried out in Hungary between 2016 and 2019 among three important stakeholder groups (local governments, national park directorates (NPDs), and state forestry units (SFUs)) of tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima). The aim of the surveys was to reveal the perception of the three groups about Ailanthus altissima, their experiences with eradication, and other needs for its successful management of the species. Besides basic statistical methods, the chi2 test, Fisher’s exact test, Cramer’s V value, and Mann–Whitney U test were conducted to compare groups and reveal relationships between different variables. 221 local governments, 10 NPDs, and 110 SFUs filled in the questionnaire. The response rate was quite low for local governments (8.8%) and high for NPDs (100%) and SFUs (97.5%). Our findings show that the species was recognised by only 59% of respondents representing local governments. Further results are presented regardingthis subsample.The negative impacts of Ailanthus altissima were perceived in all three groups at a higher rate (over 95% in all three groups) than positive impacts (local governments: 63%, NPDs: 10%, SFUs: 35%). The two groups managing forest areas (NPDs and SFUs) ranked the problems caused by the species high (the median was −4 for both groups on a −5–+5 scale). Ailanthus altissima was present in the areas of at least 80 percent in each examined group. In areas where the species was present, eradication was applied in a significantly higher percent of NPDs (86%) and SFUs (88%) than regarding local governments (36%), and the same tendency was found for using mechanical and chemical methods (p < 0.05). The two groups managing forest areas also applied biological methods, although at a lower rate (NPDs: 10%, SFUs: 14%). The unit costs and area of eradication varied between NPDs and SFUs, but the difference was not significant between the two groups (p = 0.073 and 0.213, respectively). NPDs used more external funding for eradication than local governments and state forestry units, mostly co-financed by European Union funds (e.g., LIFE and European Regional Development Fund). Information was required by a large percentage of respondents from local governments (75% of those who recognised the species). The need for cooperation between stakeholder groups was indicated by 78% of local governments recognising the species, and was ranked high by the two expert groups as well (medians were 4 for NPDs and 5 for SFUs on a 0–5 scale). Sharing knowledge about and experience with eradication among the two expert groups and transferring knowledge to the local governments are recommended for the successful management of the species. Further research is needed regarding the effectiveness, the environmental impacts, and the costs of eradication, as well as influencing factors.

1. Introduction

Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle, also known as tree of heaven, is a deciduous tree species native to Southeast Asia [1]. It was brought to Europe and North America in the 18th century, and outside its native range, it has become one of the most problematic invasive alien plant species worldwide and in Europe as well [2,3]. It is on the list of invasive alien species of European Union concern [4]. In Hungary, A. altissima has been present since the early 1800s as an ornamental tree and to tackle erosion of sandy areas in the Great Plain of Hungary, but it soon was considered in forestry as well [5]. Today it is widespread in the country, including forests, settlements, and along linear infrastructure [6,7,8,9,10,11].

A. altissima can have many negative effects on the natural environment. Due to its fast growth, good reproduction capacity, and allelopathic characteristics, it can decrease floral composition and diversity and negatively affect soil properties as well [2,12,13,14,15,16,17]. At the same time, it also provides some benefits to people in forms of medicine, wood, and honey. It can also be used for erosion control or as an ornamental tree [2]. Mechanical, chemical, and biological methods have been used for the management of A. altissima, but their effect on the native vegetation needs to be considered, and monitoring is advised for long lasting results [18]. Combatting the problems of invasive alien species has been a high priority in the European Union (EU), as it is highlighted in the EU biodiversity strategies [19,20] and in the EU Regulation No. 1143/2014 on invasive alien species [21]. The regulation includes provisions for the risk assessment, action plans on the pathways, early detection and eradication of invasive alien species, especially those of European concern. Involvement of the main sectors and stakeholder groups in the surveillance systems is also underlined.

Although there are many publications on the ecological impacts of A. altissima, studies covering the perception, knowledge, and experience of different stakeholder groups toward the species are still scarce in Europe. A few social science studies cover more than one invasive plant species, including A. altissima as well.

Dehnen-Schmutz et al. [22] conducted interviews among many stakeholder groups in Galicia, Spain, about their perception of invasive plant species in the region. A. altissima was named by 11 out of 61 respondents but was not listed among the six most important invasive plant species.

Csiszár et al. [23] surveyed Hungarian protected area managers about their perception of invasive plant and animal species, risk factors, their monitoring, and management. They received answers from 144 protected areas. A. altissima scored as the third most damaging plant species after Robinia pseudoacacia and Asclepias syriaca in areas protected by national regulation and Natura 2000 sites of European importance. 64 out of 144 protected areas were reported to be infected by the species. Risk factors, monitoring and management questions discussed were not species specific.

Straka et al. [24] carried out a questionnaire survey among the residents of Berlin about the acceptability of managing native and non-native animal and plant species in the city. A. altissima was chosen as an alien tree species in the survey. Responses showed more general patterns regardless of the species for the preferred management.

Pindaru and Nita [25] conducted a questionnaire survey among citizens of Bucharest, Romania, about invasive alien plant species. A altissima was the third most often mentioned invasive species by the respondents after Ambrosia artemisiifolia and Robinia pseudoacacia. As the purpose of its introduction, they mentioned its positive visual effect when being planted in gardens as an ornamental tree and thus improving the urban landscape.

Hazarika et al. [26] administered a structured questionnaire among the stakeholders of six countries in the European Alpine Space regarding their perception of non-native tree species. They received 456 responses. A. altissima was the third most commonly reported non-native tree species (201 responses), and was also among the most often reported invasive or potentially invasive non-native species. At the same time, it was also thought to be useful for protection against natural disturbances (39% of respondents) and urban greening (25% of respondents).

Kowarick et al. [27] conducted a questionnaire survey among the citizens of Berlin on their knowledge about the species, their views on A. altissima in different urban settings, and on the acceptance of different management strategies related to this tree species. Their results show that more people thought they recognised the species, but far fewer knew the correct name. Practitioners provided the correct name significantly more often than laypeople. Tall individuals of A. altissima in green places were preferred more than younger ones along the rail line or in the tree pit. Higher preferences were given to single mature trees in urban parks than to groups of trees in green places along the road. The adaptive on-site management received the most support. Laypeople accepted the complete removal less than professionals, and the difference was significant.

Many studies focusing on the social dimension of invasive alien species highlight that for the successful management of these species, it is important to reveal the knowledge, perception, and attitude of different stakeholder groups related to the invasive species [28,29,30]. Perception, especially risk perception related to invasive alien species, can be diverse and might vary between laypeople and experts or even between different expert groups [31,32]. It is influenced by sociocultural, economic, psychological, and ecological factors as well [33], Individual and group characteristics, knowledge, available and affordable management options, as well as the characteristics of the species itself, might be important explanatory variables behind risk perceptions of different stakeholder groups [34,35]. Risk perception may strongly influence the attitude and behaviour toward invasive alien species [36,37]; therefore, it is important to reveal them through social studies. Kapitza et al. [38], in their systematic review on the social perception of invasive species, conclude that the social dimension of invasive species has gained momentum since 2010, but many more studies focus on the perception of the general public than on the views of decision makers.

In our study we focus on the knowledge of local governments and the perception, and experience of three important stakeholder groups (local governments, national park directorates, and units of state forestry companies) related to A. altissima in Hungary. The reason for choosing these three groups for the assessment was that all of them are affected by the presence of A. altissima and have a great influence on the management of the species in their territory. Local governments are the main actors within the boundaries of settlements, while national park directorates and state forestry companies are the main professional groups managing state forests in Hungary. Our main research questions were the following. (1) What knowledge do local governments have about A. altissima in their territory? (2) How do the three stakeholder groups perceive the impacts of the species? (3) What experience do they have with the management of A. altissima in their territory? (4) What is perceived by the three stakeholder groups as important for the successful management of the species? With our study, we aim to assist the national implementation of the EU regulation on invasive alien species as well. Our hypotheses were that local governments do not have extensive knowledge about A. altissima, the perception and the used management methods vary among the stakeholder groups, and they all recognise the need for cooperation to tackle the problem of A. altissima.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods for Data Gathering

We carried out nationwide questionnaire surveys among three main stakeholder groups of A. altissima in Hungary (local governments, national park directorates, and units of state forestry companies) between 2016 and 2019, after the EU Regulation on invasive alien species came out and before the Hungarian national action plan for the pathway on invasive alien species of European Union concern (Action Plan) was developed. Table 1 provides some details about the surveys.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the three questionnaire surveys conducted among the stakeholder groups of A. altissima.

Local governments were chosen as a target group of the first survey because A. altissima has been often planted in parks and gardens within settlements, which are hotspots for their further distribution. We carried out a pilot survey in 2016 among the local governments in Pest County that were in connection with the Pilis Park Forestry Company. After the pilot survey, we sent out the same questionnaire in 2018 to the rest of those local governments in Hungary and the districts of Budapest (capital city of Hungary) that had an email connection. We acknowledge the potential bias due to the selection criteria, but we wanted to cover as many local governments as possible. The questionnaire consisted of 14 questions related to the knowledge, the perceived problems and benefits, the occurrence and spreading of the species, its management, and some questions related to the characteristics of the settlement (see the questions of the questionnaire in Appendix A). In the pilot phase, a letter containing the questionnaire was sent out first through the post with the assistance of the Pilis Park Forest Company. It was followed by an email with a link to the online version of the questionnaire. In the second phase, a letter with the link to the online questionnaire was sent out through email. We merged the answers of the pilot and the full surveys for the analysis.

The second survey was conducted in 2018 among the national park directorates (NPDs) in Hungary that supervise protected areas and Natura 2000 sites of European importance, where controlling the species is crucial. There are 10 NPDs in Hungary, and they managed only around 2% of forest areas, which accounted for less than 50 thousand hectares in 2018 [39]. The questionnaire contained questions about the problems and benefits of the species, trends related to its distribution, the factors influencing its spreading, and the management of the species with related costs (see the questions of the questionnaire in Appendix B).

We targeted the units of the state forestry companies (SFUs) with the third questionnaire survey in 2018–2019. There are 22 state forestry companies in Hungary that managed over 1 million hectares in 2018 and 2019, accounting for more than half of all forest areas in the country [39,40]. At the time of the survey, the state forestry companies were divided into 120 operational divisions called forestry units, each managing around 6000–12,000 hectares of forests. The questionnaire prepared for the forestry units was the same as the one targeting the national park directorates, allowing comparison. Although, we acknowledge the possible limitations due to the small number of NPDs.

The letters containing the questionnaire were sent out to all 10 national park directorates and 22 state forestry companies through email with the assistance of the departments of the Ministry of Agriculture responsible for forestry and nature conservation. In the email sent to the state forestry companies, they were asked to fill in the questionnaire at the level of the forestry units.

2.2. Methods for Data Analysis

Responses to the questionnaires were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet, and after cleaning, some open questions were coded and new variables were generated for the statistical analysis. Besides basic statistical methods, in the case of nominal variables, the chi2 test, and Fisher’s exact test as well as the Cramer’s V value, were used for associations (p < 0.05). In case of ordinal and interval variables, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied for comparison, because the Kolgomorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests showed that the distribution of values was not normal for either one of the subgroups (NPDs and SFUs) examined. IBM SPSS Statistics 29 software assisted our analysis.

The ethical guidelines of social science research [41] were followed during the research, ensuring voluntary participation, confidentiality, no harm to participants, and anonymity.

3. Results

First, we present the results of the questionnaire survey carried out among local governments, then compare the results of the questionnaires filled in by national park directorates and state forestry companies.

3.1. Results of the Survey Conducted Among Local Governments

After cleaning, 221 questionnaires were used for the analysis. The distribution of the local governments was quite balanced among Budapest/Pest County (33%), the western (41%), and the eastern (26%) part of Hungary. In terms of population, two-thirds (67%) of the participating settlements (including districts of Budapest) had less than 5000 inhabitants, 21% had between 5001 and 25,000, while 12% had over 25,000 inhabitants (only 3% had over 100,000 inhabitants in the whole sample). In terms of position, 46% of the respondents were mayors or legal and administrative heads of the municipality, while only 8% could be considered experts in either environmental issues or park management, and the rest (46%) were in the other categories (responsible for administrative tasks, asset management, authoritative tasks, or it was not specified).

We had a question about recognising A. altissima by showing three pictures with three plant species, and the respondent had to mark A. altissima. Only 59% of the respondents gave the right answer; the rest did not recognise the species. Respondents representing settlements (including districts of Budapest) with a larger number of inhabitants recognised A. altissima with a significantly higher percentage than those of smaller settlements (less than 5000 inhabitants: 56%, 5001–25,000: 76%; over 25,000: 85%) based on the chi2 test (p < 0.05). Respondents representing municipalities from Budapest and Pest County recognised A. altissima with a significantly higher percentage than from the other two regions (Budapest/Pest County: 73%, West: 53%, East: 52%) based on the chi2 test (p < 0.05).

In terms of perceived negative impacts, the highest number of respondents (91%) indicated that it displaces native species, while the other negative impacts were marked by less than 26% of all respondents. Based on the chi2 test, a significantly higher percentage of respondents indicated some negative impacts (displacing native species, releasing anti-sprouting compounds into the soil, causing damage to agriculture) among those who recognised the species (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Regarding the positive impacts, a few options were marked by at least 30% of all respondents (giving a shade, being a good honey making plant, not being aware of any positive effects). Based on the chi2 test, a significantly lower percentage of respondents indicated an exotic look as a positive impact among those who recognised the species (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between perceived impacts and recognition of A. altissima.

In the following, we focus on the answers of only those respondents who recognised the species (n = 131). 80% of the respondents recognising the species indicated that the A. altissima was present in their settlement. A significantly higher percentage of respondents of Budapest/Pest County (89%) and the Eastern region (83%) indicated the presence of the species than of the Western region (69%), based on the chi2 test (p < 0.05). A significantly higher percentage of respondents marked the presence of the species in settlements with a larger number of inhabitants than in smaller settlements (less than 5000 inhabitants: 69%; 5001–25,000: 91%; more than 25,000: 100%) based on the chi2 test (p < 0.05).

In the following, we focus on the answers of respondents who recognised the species and indicated the presence of A. altissima in their settlements (n = 105). Places where the species were observed were marked as follows: outside the inhabited area (53%), along roads (52%), in gardens (47%), in parks (25%). Some other places were mentioned as well (e.g., in forests and forest edges, near buildings, in the cemetery). More answers could be marked. The majority of the respondents recognising the species and indicating its presence in the settlement (95%) did not know when A. altissima was introduced into the settlement, but a majority of them (87%) indicated how it was probably introduced. A large percentage of respondents marked that it appeared spontaneously (76%), and a smaller percentage thought that it came from private areas, e.g., gardens (28%), or was planted by the municipality (3%). More than one answer could be marked.

The majority of respondents recognising the species and marking its presence (84%) had an idea how A. altissima was spreading. More than one answer could be marked. The order of the perceived ways was as follows: new seedlings sprout from the seeds of older trees (55%), sprout from the ground after felling trees (54%), spread along the roads (32%), and are planted by inhabitants (3%).

Only 10% of the respondents recognising the species and indicating its presence (N = 105, 100%) marked that A. altissima was monitored, but 36% stated that the municipality used some eradication methods (only mechanical: 25%, only chemical: 1%, and a combination of the two: 10%). Some respondents indicated the use of some eradication methods even though they marked before that they had not eradicated A. altissima. We corrected the inconsistencies in a way that we counted the exact methods only for the consistent answers (who marked before that eradication had taken place). Respondents from settlements with a larger number of inhabitants indicated the control of the species at a significantly higher rate than respondents from smaller settlements (less than 5000 inhabitants: 26%; 5001–25,000: 34%; more than 25,000: 64%) based on the chi2 test (p < 0.05). Only a few respondents mentioned financial resources, where the internal source (budget of the municipality) was dominating. 59% of the respondents recognising the species and marking its presence indicated that the eradication could be performed within the public works programme (a state financed programme for temporary employment).

A total of 75% of respondents recognising the species (n = 131, 100%) marked that they would like to obtain more information about the species (impacts: 54%, control methods: 47%), 79% thought that cooperation with other stakeholder groups was needed (with residents: 63%, with forestry companies and nature conservationists: 62%).

In case A. altissima was perceived present in the settlement, the negative impacts, reasons for introduction, and need for information and cooperation were indicated significantly more often compared to those settlements where they were not seen, based on the chi2 or Fisher’s exact test (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations between A. altissima related variables and the perceived presence of the species (only for respondents recognising the species (N = 131)).

3.2. Results of the Survey Conducted Among National Park Directorates and Districts of State Forestry Companies

All 10 national park directorates (NPDs), 108 state forestry units (SFUs), and two state forestry companies (summarising the answers for all of their forestry units) filled in the questionnaires. We treated forestry companies as units for the analysis (N = 110). Both groups (NPDs and SFUs) cover the whole country, and their distribution follows the size of the three regions identified (Pest County/Budapest: 10–14%, West: 40–46%, and East: 40–50%). Respondents were experts; therefore, no question about recognising the species was included.

The seriousness of the problem was ranked by the respondents on a scale of −5 (very serious problem) to +5 (very positive). Based on the Mann–Whitney U test, there was no difference between the two groups (NPDs and SFUs) (p = 0.411), medians were −4 for both groups, showing that they considered the spread of the species as a serious problem.

Negative impacts, especially negative ecological impacts of A. altissima, were perceived in both groups in higher percentages than positive impacts. The only statistically significant difference between the two groups was the perception about the negative economic impacts based on Fisher’s exact test (p < 0.05), indicated only by the SFUs (forestry units) (Table 4). In the comparison with the survey among local governments, local governments indicated positive impacts at a higher percentage (63%) than the two expert groups, and the difference was significant based on the chi2 test (p < 0.05). Nevertheless, we need to note that for local governments there was a predefined list the respondents could choose from, while for the two expert groups it was an open question.

Table 4.

Associations between the respondent group and the perceived impacts of A. altissima.

Table 5 shows the comparison of the two expert respondent groups (NPDs and SFUs) regarding the perceived main factors influencing the spread of A. altissima. Human inaction was perceived by the highest percentage of respondents in both groups as an influencing factor of spreading. Based on Fisher’s exact test, the only statistically significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.05) was the perception about the influence of human activities on the spread of the species, which was indicated by a larger percentage of the NPDs (national park directorates). Lack of eradication and abandonment of some areas were mentioned as examples of human inaction that contributed to the spread of the A. altissima. Human disturbances in forests, in other habitats, and along roads, as well as planting the species in settlements, were mentioned as human actions assisting the dispersal of the species. The changing climate and the wind were indicated as favourable environmental conditions influencing the spread of the species. The ability of A. altissima to occupy an area, its allelopathic effects, rapid growth, very good sprouting ability, and productivity already in a few years were named as characteristics contributing to the expansion of the species.

Table 5.

Associations between the respondent group and the perceived factors that influence the spread of A. altissima.

More than two-thirds of the respondents in both groups (NPDs: 70%, SFUs: 75%) indicated that A. altissima was present in more than 1 hectare in the forest areas they manage. A significantly higher percentage of respondent organisations indicated the presence of the species in the Western region (84%) and in Budapest/Pest County (81%) than in the Eastern region (63%) based on the chi2 test (p < 0.05).

In the following, we use the subgroups where the species was present for the analysis (NPDs: n = 7, SFUs: n = 83). 45% of the state forestry units, which had A. altissima in their territory, utilised the species, but none of the national park directorates did. This difference was significant based on Fisher’s exact test (p < 0.05). The speed of spreading was ranked by the respondents on a scale of 0 (not spreading) to 5 (spreading rapidly). Based on the Mann–Whitney U test, there was no difference between the two groups (medians for NPDs: 3 and SFUs: 2, p = 0.735), showing that they considered the spread of the species moderate. The size of the area covered by A. altisssima was not uniformly interpreted among the respondents (e.g., covered only with this species or mixed with other species). Nevertheless, the medians were less than 100 hectares in both groups (NPDs: 80 ha, SFUs: 41 ha), and the difference was not significant based on the Mann–Whitney U test (p = 0.725). In general, a higher ratio of the areas covered by the species was protected regarding the territories of the national park directorates than the state forestry units (median for NPDs: 80%, SFUs: 1%), and it was significant, based on the Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.05).

A larger percentage of SFUs that had A. altissima in their territory stated that the species caused some economic problems in their forestry activities, while a larger percentage of NPDs indicated that it caused ecological problems in their forestry management. Both differences were significant based on Fisher’s exact test (p < 0.05).

Most organisations in both groups that had A. altissima in their territory used some eradication methods, more often chemical and mechanical than biological methods, and at least half of them in each group used more than one method. The majority of both organisations (NPDs and SFUs) used control measures after eradication. There were no significant differences between the groups based on Fisher’s exact test (Table 6). Comparing the results with the results of the other survey, a significantly smaller percentage of local governments used either mechanical or chemical methods or more than one method than the two other organisations combined based on the chi2 test (p < 0.05) conducted on the subsamples where A. altissima was present. To be able to run the test combining the datasets of NPDs and SFUs was necessary due to the low number of NPDs where the species was present. As previously shown, results of the NPDs and SFU did not differ significantly, which was the other reason for merging the datasets for this analysis. The use of biological methods and control after eradication was not asked in the other survey focusing on local governments.

Table 6.

Associations between the respondent group and the eradication methods used for A. altissima (only for organisations that indicated the presence of the species).

Table 7 shows some indicators related to the eradication of the species, comparing the responses of NPDs and SFUs using the Mann–Whitney U test. For the comparisons, medians were used instead of means because the variables were not characterised by normal distribution. The middle values of the estimated areas, where A. altissima was eradicated were less than 30 hectares regarding both respondent groups. The ratio of permanently eradicated area varied within the groups, and medians also show a higher rate for NPDs (65%) compared to SFUs (30%), but the difference was not significant based on the Mann–Whitney U test. The cost of eradication and the yearly follow up control per hectare also showed a wide range within groups within the respondent groups. Using the medians, there was no significant difference between the groups based on the Mann–Whitney U test. Some factors were named that influence the costs of eradication: size of the affected area, environmental circumstances, the spread of the species, the number of trees and the age of the trees or stands, density of trees, seed base in the soil, weather conditions, the distance of the stands from the site, the applied methods, the human input needed, the amount and type of chemicals used, if it is the first time or a post eradication control measure, the success of the previous eradication. The NPDs used less internal funding than the SFUs for the eradication (median for NPDs: 5%; SFUs: 100%), and the difference was significant based on the Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.05). External sources included mostly using funds co-financed by the European Union (e.g., LIFE, European Regional Development Fund). The lower response rate regarding these questions compared to other questions might indicate the difficulties of such estimations (Table 7). The majority of the respondents in both groups who had A. altissima present in their territory (NPD: 100%, SFU: 90%) indicated the need for further eradication of the species in their area, and there were no significant differences between the two groups based on Fisher’s exact test (p = 1.00). More than half of the respondents of both groups (NPD: 87%, SFU: 54%) indicated that they need external resources as well to continue the eradication, and there was no significant difference between the two groups based on Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.134).

Table 7.

Some indicators related to the eradication of A. altissima—comparison of the two respondent groups (only for organisations that indicated the presence of the species).

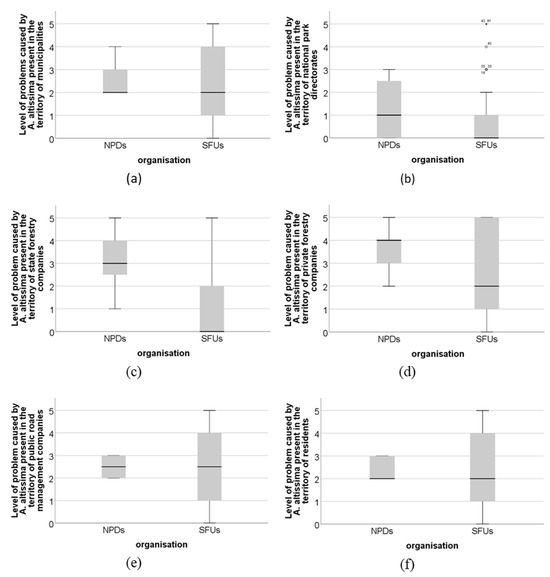

The presence of A. altissima in the territory of different stakeholder groups caused a problem to a variable degree for our two respondent groups. We measured the extent of the problem on a Likert scale (0–5: 0, not a problem at al;, 5: a major problem). The medians of the answers show that for NPDs, the presence of the species on the territory of private and state forestry companies seemed to cause the largest problem, while for SFUs, the species present on the territory of the public road management companies was the most problematic. Based on the Mann–Whitney U test, only the problem regarding the state forestry companies showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the two respondent groups (municipalities: p = 0.603, national park directorates: p = 0.550, state forestry companies: p = 0.001, private forestry companies: p = 0.183, public road management companies: p = 0.955, residents: p = 0.835). The analysis was carried out among the organisations that indicated the presence of the species on their territory (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Boxplots regarding problems caused by A. altissima present in the territory of stakeholder groups to the respondent organisations. (a) municipalities, (b) national park directorates, (c) state forestry companies, (d) private forestry companies, (e) public road management companies, (f) residents (scale: 0–5, 0: does not cause any problems, 5: cause severe problems) (only those respondent organisations were considered that indicated the presence of the species in their territory). Black line in the boxes represents the median. In (b) mild outliers are marked with a circle and extreme outliers are marked with an asterisk. Numbers around these signs represent some cases from the dataset with the given value. Outliers are legitimate, because they are within the possible range (0–5).

NPDs and SFUs in the territory in which A. altissima was present, were most satisfied with their own groups regarding the control of A. altissima and, to a lesser degree, with other groups. Fisher’s exact test showed a significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.05) only regarding the state forestry companies, namely a much larger percent of SFUs thought that this group managed the species properly (NPDs: 33%, SFUs: 4%) (Table 8). We need to note that the response rate was not so high, which indicates that it was probably difficult for our respondent groups to estimate the effectiveness of the other stakeholder groups’ activities.

Table 8.

Associations between the respondent group and the perceived proper control of A. altissima performed by different stakeholder groups.

NPDs and SFUs cooperated with the members of their own groups and with each other the most and to a lesser degree with other groups. Fisher’s exact test showed no significant difference between the two groups regarding none of the stakeholder groups (Table 9).

Table 9.

Associations between the respondent group and the cooperation with other stakeholder groups related to A. altissima.

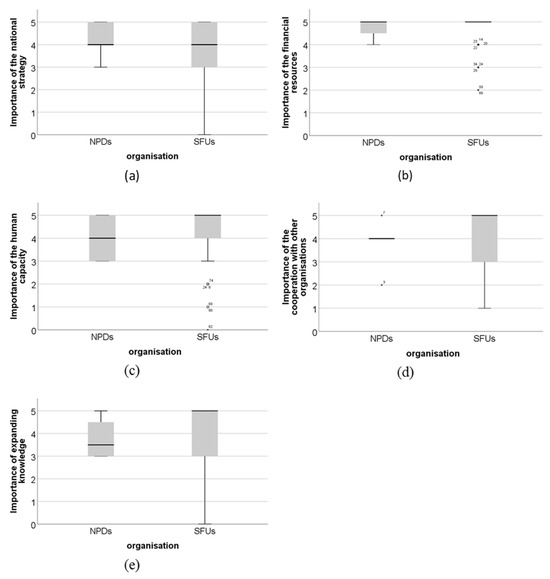

All five factors (national strategy, financial resources, human capacity, cooperation with other groups, expanding the knowledge base) related to the eradication of A. altissima were ranked high by both response groups (median of 3.5–5 on a Likert scale of 0 (not important) to 5 f (very important)) (Figure 2). There was no significant difference between the two groups based on the Mann–Whitney U test (national strategy: p = 0.507, financial resources: p = 0.935, human capacity: p = 0.403, cooperation with other groups: p = 0.404, expanding knowledge: p = 0.381).

Figure 2.

Boxplots regarding the importance of factors influencing the eradication of A. altissima as perceived by the two respondent groups (scale 0–5, 0: not important, 5: very important) (a) national strategy, (b) financial resources, (c) human capacity, (d) cooperation with other organisations (e) expanding knowledge). Black line in the boxes represents the median. Where there is no box, only a line, it means that the median, the first and the third quartile is the same. In (b–d) mild outliers are marked with a circle and extreme outliers are marked with an asterisk. Numbers around these signs represent some cases from the dataset with the given value. In (b–d) outliers are legitimate, because they are within the possible range (0–5).

4. Discussion

Our results show that only 59% of the respondents representing local governments recognised A. altissima. Respondents from settlements with more inhabitants recognised the species with a significantly higher percentage than smaller settlements. Larger settlements probably afford hiring a chief gardener or an environmental expert who can detect the species better. A higher percentage of experts recognised it than mayors and other officers, who are usually non-experts. Kowarick et al. [27] also show in their study conducted in Berlin that experts knew the correct name of the species at a higher percentage than laypeople. Some studies emphasise that knowledge about the invasive alien plant species can be correlated with the support of their management [42,43,44].

In our study, positive impacts of A. altissima were perceived by a significantly larger percentage of respondents from local governments than from national park directorates and state forestry units managing forest areas mostly outside settlements. Some studies also highlight positive impacts of invasive alien tree species in cities (e.g., giving shade, visual effects, cleaning the air) [25,45]. Although some invasive alien tree species can have a positive economic impact as well and might be preferred by forestry companies (e.g., Robinia pseudoacacia) [46,47], in the case of A. altissima, our study shows that it negatively influenced forestry activities. Therefore, the state forestry units also supported its eradication.

Mechanical and chemical eradication methods or their combination were applied by a significantly lower percentage of local governments than by state organisations managing forests in Hungary. A larger percentage of local governments applied mechanical methods than chemical methods. This latter might be explained by the fact that chemical methods require more skills and might be more costly than mechanical methods. Soler and Izquierdo [18], in their recent review on A. altissima, indicate that mechanical or chemical methods alone are not sufficient and the combination of two might be more effective. Csiszár and Korda [48] refer to Hungarian cases focusing on the eradication of A. altissima. They also conclude that applying mechanical methods alone is not advised, but there were successful cases using chemical methods. Biological control is quite new and was already applied by some NPDs and SFUs managing state forests, according to our survey results. Miles et al. [49] in their review show a wide range of potential biological agents against A altissima, but they also emphasise the need for further research on their application and combination with other methods. Soler and Izquierdo [18] stress that chemical and biological methods can have negative environmental impacts as well that need to be carefully taken into account in their application.

Based on our results, the per hectare cost of eradication of A. altissima varied in forest areas (10 to 750 thousand HUF2018/ha). The unit costs depend on many factors, e.g., the spread of the species, the age of the stands, some environmental circumstances, and the applied eradication methods. Demeter et al. [50], in an earlier study, showed that the unit cost of eradication in the Kiskunság NPD was 570 thousand HUF2015/ha. The results of Peugh et al. [51] indicated that depending on the agent used for the chemical control, cost can also vary. Fernandez et al. [52] summed the reported costs using the InvaCost database for 72 invasive tree species worldwide, and the total cost was 19.2 billion USD between 1960 and 2020. A. altissima was not among the 10 species with the highest costs that were detailed. Nevertheless, the authors stress that there is a large information gap related to the reported costs of invasive tree species.

Based on our results, local governments and state forest districts used more internal financial sources for eradication, while national park directorates indicated more external sources. Kovács et al. [53] show that NPDs and SFUs used EU funds (LIFE and European Regional Development Fund) for the eradication of invasive alien plant species in forest areas, including A. altissima. Scalera [54] and Piria et al. [55] also indicate that LIFE has been used to finance eradication of invasive alien species. However, Piria et al. [55] highlight that funding is not sufficient in Europe to tackle the problems caused by invasive alien species.

Based on our findings, a large percent of local governments indicated the need to cooperate with national park directorates and state forestry organisations in eradicating A. altissima. National park directorates and state forestry units cooperated more with organisations within their own group and less with local governments. But they also ranked the importance of cooperation with other stakeholder groups high in the effective control of the species. Fischer and Charnley [36] showed that private forest owners in the US cooperated with their neighbours regarding the management of invasive alien species. Other studies also highlight the importance of coordinated actions among stakeholders in the eradication and control of invasive alien species, including A. altissima [56,57].

5. Conclusions

Our study showed the results of questionnaire surveys carried out among local governments, national park directorates, and state forestry units in Hungary to assess the knowledge and perception of these stakeholder groups related to A. altissima, reveal the eradication methods they apply, and information and cooperation needed for the control of the species. With this analysis we contributed to expanding the knowledge base on the social and economic aspects of this invasive alien species that is lacking in the international literature as well.

Our study had some limitations. Due to the small total number of national park directorates in Hungary (10), especially in the comparison of results of state forestry units. Nevertheless, it seems from our findings that comparisons were possible regarding most questions.

According to our findings, a quite large proportion of respondents representing local governments (41%) did not recognise the species, which is in line with our related hypothesis that local governments have no extensive knowledge about the species. It underlines the importance of providing information to local governments, especially to those without expertise (e.g., settlements with a low number of inhabitants), to assist the recognition of A. altissima. A large percent of respondents recognising the species indicated the need for more information. Local governments are one of the main target groups related to A. altissima in the Hungarian action plan on invasive alien species of European importance present in Hungary [6], and raising their awareness is also emphasised in the action plan. Providing information on the characteristics of the species, its impact on the natural environment, and methods of eradication is recommended.

The seriousness of the problem was considered high by NPDs and SFUs, but the speed of spreading was seen as moderate. Negative ecological impacts of the species were perceived by all three groups, but more positive impacts were marked by the local governments, and economic losses were seen more by the SFUs. Based on our results, we can partly accept our hypothesis on the differing perception of the examined groups regarding the species. The majority of respondents in all three groups indicated that A. altissima was present in their territory. However, from the answers of the NPDs and SFUs, it seemed that it was not easy to determine the exact size of the area where A. altissima was present. The action plan [6] also emphasises the need for a cost effective way of delineating the areas affected by the species, e.g., using remote sensing. In forest areas, the extent of the area where A. altissima was present could be interpreted in different ways, which is also a limitation of our study. In future surveys it will be important to define this term better.

In the action plan [6], it is stated that the eradication of A. altissima is of high importance, especially in areas under the management of national park directorates and in the most valuable habitats from a nature conservation point of view. The eradication in forest areas is also a legal obligation. Based on our results, a higher percent of NPDs and SFUs were putting efforts into the eradication of A. altissima than local governments. Mechanical and chemical methods were used by all three groups for eradication, but by a larger percent of the NPDs and SFUs than by the local governments. Therefore, we can accept our hypothesis that the management methods vary among the three stakeholder groups. This result indicates the need for knowledge transfer from NPDs and SFUs to local governments regarding the eradication methods. Biological methods were used by NPDs and SFUs but less often than the other two methods. The reported rate of long term eradication varied within NPDs and SFUs as well, but the median did not reach 70% in either group. The per hectare costs also varied and were quite high in some cases (maximum: 790 HUF/ha). Although chemical and biological methods, especially in combination with other methods, can be effective, they can have negative environmental impacts as well. Therefore, sharing of experiences between the two expert groups is recommended in order to minimise the negative side effects, increase the effectiveness, and lower the costs. Participatory methods might be used to facilitate the process. Further research is needed regarding the effectiveness, the environmental impacts, and the costs of eradication, as well as influencing factors.

The importance of cooperation between the stakeholder groups was ranked high in all three examined groups for the successful eradication of the species, confirming our related hypothesis. In addition, national strategy, financial resources, human capacity, and expanding the knowledge base were also perceived as highly important by NPDs and SFUs. There has been some progress made in the raised issues in recent years (e.g., the completion of the action plan). However, given the severity of the problems caused by A. altissima and the high level of human and financial resources needed for its long lasting eradication, further steps are still desired for the successful management of the species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D., E.T.K. and S.C.; methodology, A.D., P.C., T.L. and E.T.K.; software, E.T.K. and D.S.; investigation, A.D.; data curation, A.D., E.T.K. and D.S.; formal analysis, A.D., E.T.K. and D.S.; validation, A.D., P.C. and T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., E.T.K. and D.S.; writing—review and editing, A.D., D.S., S.C., P.C., T.L. and E.T.K.; visualisation, E.T.K. and D.S.; supervision, E.T.K. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the respondents of the questionnaire surveys. We also appreciate the assistance of the forestry and nature conservation departments of the Ministry of Agriculture.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NPD | National park directorate |

| SFU | State forestry unit |

Appendix A. Questions of the Questionnaire for Local Governments

- General questions about the tree of heaven

- 1.

- Choose the species from the pictures below!

- 2.

- In your opinion, what negative effects could the spread of the tree of heaven have in Hungary ? (You can tick more than one answer)

- It displaces native plant species and the animal species associated with them

- It introduces germination-inhibiting compounds into the soil

- Many people are allergic to it

- It causes significant damages in the agricultural sector

- Other, namely …………………………………………………………

- I do not know of any negative effects

- 3.

- In your opinion, what positive effects could the spread of tree of heaven in Hungary have? (You can tick more than one answer)

- Good nectar supplier

- Provides good timber

- Exotic appearance

- Creates species-rich habitats

- Provides shade

- Other, namely ……………………………………………………

- I do not know of any positive effects

- Questions about the occurrence and distribution of the species

- 4.

- Is the tree of heaven present in your municipality? (You can tick more than one answer)

- Yes, it occurs along the roads

- Yes, it occurs in gardens

- Yes, it occurs in parks

- Yes, it occurs outside residential areas

- Yes, in other places, namely ………………………

- Yes, but not common

- No

- I do not know

- 5.

- How do you think the tree of heaven came into your municipality? (You can tick more than one answer)

- Planted by the municipality as an ornamental tree

- Appeared spontaneously

- Spread from private areas (e.g., gardens)

- other, namely …………………………………………………………………………

- Do not know

- 6.

- Do you know when the tree of heaven was introduced to the municipality?

- Yes, and specifically ………………………

- No

- 7.

- How does the species spread in the municipality? (You can tick more than one answer)

- Sprouted from the ground after cutting down existing trees

- It spreads further along roads

- New individuals emerge from the seeds of older trees (with a trunk diameter of at least 10 cm)

- Residents plant it diligently

- other, namely…………………………………………………………………………………

- I do not know

- 8.

- Does the municipality have a tool to monitor the appearance and spread of the tree of heaven (e.g., regular survey), or a local government measure or decree aimed at its suppression?

- Yes, and specifically …………………………

- No

- I do not know.

- Questions about the suppression of the species

- 9.

- Does the local government deal with the suppression and eradication of the species? If so, from what source?

- Yes, we regularly spend money on the eradication of the tree of heaven, using the following sources: …………………………………………..

- We have tried to prevent its spread, using the following sources: ……………………

- No, because it meets our expectations as an unpretentious ornamental plant

- No, because there is no money for it

- No, because ……………………………………………………………………………

- 10.

- If you eradicate the species, what methods do you use?

- Mechanical (cutting, pruning)

- Chemical (spraying, bark dressing, injection)

- Mechanical and chemical

- Other, namely …………………………………………………………………………………

- 11.

- Would you like to know more about the tree of heaven? (You can tick more than one answer)

- Yes, I am interested in its effects on habitats

- Yes, I would be interested in how we can protect ourselves from it

- Yes, I would also be interested in ………………………………………

- No

- 12.

- Do you think there is a need for cooperation in managing the species? (You can tick more than one answer)

- Yes, communication and cooperation with local forestry and nature conservation is important

- Yes, the residents should also be involved

- No, we can fight with the problems alone

- other, namely …………………………………………………………………………………

- 13.

- Do you think it would be possible to eradicate the tree of heaven through public works programmes?

- Yes

- No

- 14.

- Do you have any other experiences, ideas, requests, or comments that you would like to share with us?

- …………………………………………………………………………………………

- Which municipality do you represent? ……………………………………

- Can we name the municipality in our analyses?

- Yes

- yes, under the following conditions: …………………………………………………

- No

Appendix B. Questions of the Questionnaire for National Park Directorates and State Forestry Districts

- Which institution do you represent (which state forestry company and which forestry districts): ……………………………………………………………………………………….

- 1.

- Question

- Please indicate with a number on the scale of −5 (serious problem) 0 (neutral) +5 (significant positive assessment), how serious you consider the problem of the strong spreading of the tree of heaven in Hungary. Please justify your answer!

- −5 −4 −3 −2 −1 0 1 2 3 4 5

- Justification: ……………………………….

- 2.

- Question

- What do you think are the positive and negative effects of the spread of the species?

- Positive effect: ……………………………………………………………………….

- Negative effect:……………………………………………………………………………………………..

- 3.

- Question

- What factors do you think assist the spread of the species in Hungary the most?

- …………………………………………………………………………………………………..

- 4.

- Question

- How widespread is the species in the areas under your management, and how large an area does it occupy? How much of the area it occupies is protected and how much is a Natura 2000 area?

- Distribution of the species: ………………………………

- 5.

- Question

- What influences the spread of the tree of heaven the most in the area you manage, and how would you characterise the speed of its spread?

- Factors influencing the spread of the species: ……………………………………………….

- Indicate the speed of its spread with a number on the scale, where 0: does not spread, and 5: spreads extremely quickly, occupying new areas every year!

- 0 1 2 3 4 5

- 6.

- Question

- Can you use the species in any way?

- No.

- Yes, this way ……………………………………………………..

- 7.

- Question

- Does the species cause any problems in your forestry activities? If so, what?

- No.

- Yes, and specifically: ……………………………………………………….

- 8.

- Question

- Are you involved in the eradication of the tree of heaven?

- We are not involved in eradication, and we do not plan to do so.

- We are not involved in eradication, but we are planning to do so.

- Yes, we are involved in eradication.

- If yes, the methods of eradication (multiple answers are possible):

- Chemical, namely: …………………………………………………………………….

- Mechanical, namely: …………………………………………………………………

- Biological, namely: ……………………………………………………………………….

- Was post-treatment necessary?

- No.

- Yes, for ……… years, with ……………… method.

- After eradication, did you experience the allelopathic (growth-inhibiting) effect of the species (e.g., more difficult renovation, possible failure)?

- No.

- Yes, namely: ………………………………………………………….

- 9.

- Question

- How large was the area where the species had been eradicated and what proportion of that area has been permanently eradicated?

- Area affected by the eradication of the species: …………….. ha, of which …………….% does not require further post-treatment.

- 10.

- Question

- If you eradicate the species, what costs do you have per hectare and what do these amounts depend on?

- One-time cost of suppression: … HUF/ha

- Cost of follow-up treatment: ……. HUF/ha for ….. years.

- The costs depend on the following factors: ……………………………………………………………….

- 11.

- Question

- In what ratio can the eradication of the species be financed from your own resources, or from public funds or other sources?

- Own resources ratio: ……%

- Public funds ratio: ……%

- Other, namely: …, ……%

- 12.

- Question

- What funding sources has your organisation received/is it using to eradicate tree of heaven? (LIFE, Environmental and Energy Operative programme of the National Development Plan financed from the European Regional Development Fund, European Agricultural Rural Development Fund, and other, etc.)

- Financial sources: ……………………………………………………..

- 13.

- Question

- How is your organisation affected by the attitude of local organisations and groups towards the species?

- Do you think that the tree of heaven individuals/stocks located in the areas of the following organisations and groups cause you problems in the spread of the species? Choose from the following answer options, circle the one next to the given group: I do not know; or on a scale from 0 to 5, where 0: not at all, 5: a big problem.

| Stakeholder Group | Not a Problem at all | Big Problem | |||||

| local governments | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | I do not know |

| national park directorates | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | I do not know |

| state forestry companies | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | I do not know |

| private forestry comapneis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | I do not know |

| road operators | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | I do not know |

| residents | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | I do not know |

| other, namely: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | I do not know |

- In your opinion, do the following organisations and groups in your area properly manage their areas infected with the tree of heaven? Choose from the following answer options and write next to the given group: yes, in this way………..; no, and the reason for this is………………….

| Stakeholder Groups | They Manage Well | They Do Not Manage Well |

| local governments | yes, in this way: ……………… | no, and the reason is: ……………………………….. |

| national park directorates | yes, in this way: ……………… | no, and the reason is: ……………………………….. |

| state forestry companies | yes, in this way: ……………… | no, and the reason is: ……………………………….. |

| private forestry companies | yes, in this way: ……………… | no, and the reason is: ……………………………….. |

| road operators | yes, in this way: ……………… | no, and the reason is: ……………………………….. |

| residents | yes, in this way: ……………… | no, and the reason is: ……………………………….. |

| other, namely: | yes, in this way: ……………… | no, and the reason is: ……………………………….. |

- Is there a cooperation between the following organisations, groups and you in the eradication of the species? If so, what kind? Please choose from the following answer options and write next to the given group: no cooperation; there is cooperation, namely…. (e.g., they ask for expert advice, help with treatment, exchange of experiences, exchange of information…)

| Stakeholder Groups | No Cooperation | There Is Cooperation |

| local governments | no cooperation | there is cooperation, namely: …………………… |

| national park directorates | no cooperation | there is cooperation, namely: …………………… |

| state forestry companies | no cooperation | there is cooperation, namely: …………………… |

| private forestry comapnbeis | no cooperation | there is cooperation, namely: …………………… |

| road operators | no cooperation | there is cooperation, namely: …………………… |

| residents | no cooperation | there is cooperation, namely: …………………… |

| other, namely: | no cooperation | there is cooperation, namely: …………………… |

- 14.

- Question

- Do you feel it is necessary to further eradicate the species in the areas under your management? If so, from what sources do you plan to achieve this?

- I do not know.

- No.

- Yes, and from the following sources: ……………………………………………

- 15.

- Question

- In your opinion, approximately how much money would be needed to eradicate the tree of heaven from the area under your management? …………………… HUF

- 16.

- Question

- Choose what you think would be the most needed to effectively reduce the species? (mark on a scale where 0: not important, 5: absolutely necessary)

- National strategy: 0 1 2 3 4 5,

- Financial resources: 0 1 2 3 4 5,

- Human capacity: 0 1 2 3 4 5,

- Cooperation with national park directorates/forestry enterprises/municipalities/residents: 0 1 2 3 4 5.

- Expansion of knowledge base: 0 1 2 3 4 5.

- Other, namely: ………………………………………………………………… 0 1 2 3 4 5.

- 17.

- Question

- Do you have any other comments on this topic?

- …………………………………………………………………………………….…………

References

- Kowarik, I.; Säumel, I. Biological Flora of Central Europe: Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2007, 8, 207–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladonja, B.; Sušek, M.; Guillermic, J. Review on Invasive Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle) Conflicting Values: Assessment of Its Ecosystem Services and Potential Biological Threat. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 1009–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPBES. Thematic Assessment Report on Invasive Alien Species and their Control of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Roy, H.E., Pauchard, A., Stoett, P., Renard Truong, T., Eds.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1141 of 13 July 2016 Adopting a List of Invasive Alien Species of Union Concern Pursuant to Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Consolidated Text. 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02016R1141-20220802&from=EN (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Korda, M. A Magyarországon inváziós növényfajok elterjedésének és elterjesztésének története I. Acer negundo, Ailanthus altissima, Celtis occidentalis, Elaeagnus angustifolia, Fraxinus pennsylvanica, Padus serotina. Tilia 2018, 19, 1–459. Available online: https://real-j.mtak.hu/21198/1/Tilia_19.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Nagy, G.G.; Czirák, Z.; Demeter, A.; Dóka, R.; Fadel, N.; Jónás, B.; Riskó, A.; Schmidt, A.; Sulyán, P.; Váczi, O.; et al. Az európai uniós jegyzéken szereplő idegenhonos inváziós fajok terjedési útvonalainak magyarországi átfogó elemzése és értékelése, valamint a terjedési útvonalak cselekvési tervei. Agrárminisztérium, Természetmegőrzési Főosztály, 2020; 109p. Available online: http://www.invaziosfajok.hu/uploads/document/2/ias-cselekvesi-terv-magyarorszag-ver6-boritoval-60262df28bd04.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Erdélyi, A.; Hartdégen, J.; Malatinszky, Á.; Vadász, C. Silvicultural Practices as Main Drivers of the Spread of Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle). Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2021, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilassi, P.; Soóky, A.; Bátori, Z.; Hábenczyus, A.A.; Frei, K.; Tölgyesi, C.; van Leeuwen, B.; Tobak, Z.; Csikós, N. Natura 2000 Areas, Road, Railway, Water, and Ecological Networks May Provide Pathways for Biological Invasion: A Country Scale Analysis. Plants 2021, 10, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnich, V.J.; Udvardy, O.; Kajtor-Apatini, D.; Ferencz, Á.; Szarvas, A.; Makra, L.; Magyar, D. Pollen concentration of invasive tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) on the Northern Great Plain, Hungary. Acta Herbol. 2022, 31, 43–52. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Laszlo-Makra/publication/363837527_Pollen_concentration_of_invasive_tree_of_heaven_Ailanthus_altissima_on_the_Northern_Great_Plain_Hungary/links/6440ee632eca706c8b6f521f/Pollen-concentration-of-invasive-tree-of-heaven-Ailanthus-altissima-on-the-Northern-Great-Plain-Hungary.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Erdélyi, A.; Hartdégen, J.; Malatinszky, Á.; Vadász, C. Historical reconstruction of the invasions of four non-native tree species at local scale: A detective work on Ailanthus altissima, Celtis occidentalis, Prunus serotina and Acer negundo. One Ecosyst. 2023, 8, e108683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vig, T.; Erdélyi, A.; Malatinszky, Á. The distribution of the tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle) in the settlements and forests of Southern Börzsöny, Hungary. Bot. Közlem. 2023, 110, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Aparicio, L.; Canham, C.D. Neighbourhood analyses of the allelopathic effects of the invasive tree Ailanthus altissima in temperate forests. J. Ecol. 2008, 96, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszár, Á. Allelopathic effects of invasive woody plant species is Hungary. Acta Silv. Lign. Hung. 2009, 5, 9–17. Available online: http://publicatio.uni-sopron.hu/112/1/01_csiszar_p.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Csiszár, Á.; Korda, M.; Schmidt, D.; Šporčić, D.; Süle, P.; Teleki, B.; Tiborcz, V.; Zagyvai, G.; Bartha, D. Allelopathic potential of some invasive neophytes occurring in Hungary. Allelopath. J. 2013, 31, 309–318. [Google Scholar]

- Motard, E.; Dusz, S.; Geslin, B.; Akpa-Vinceslas, M.; Hignard, C.; Babiar, O.; Clair-Maczulajtys, D.; Michel-Salzat, A. How invasion by Ailanthus altissima transforms soil and litter communities in a temperate forest ecosystem. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 1817–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, A.; Saláta, D.; Tormáné Kovács, E.; Szirmai, O.; Trenyik, P.; Meinhardt, S.; Rusvai, K.; Verbényiné Neumann, K.; Schermann, B.; Szegleti, Z.; et al. Effects of the invasive tree species Ailanthus altissima on the floral diversity and soil properties in the Pannonian Region. Land 2021, 10, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, M.; Fontaneto, D.; Casella, F. Effects of Ailanthus altissima Invasion and Removal on High-Biodiversity Mediterranean Grasslands. Environ. Manag. 2021, 68, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J.; Izquierdo, J. The invasive Ailanthus altissima: A biology, ecology, and control review. Plants 2024, 13, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Our Life Insurance, Our Natural Capital: An EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020, COM(2011) 244 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0244 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0380 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 on the Prevention and Management of the Introduction and Spread of Invasive Alien Species. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014R1143 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Chas-Amil, M.L.; Touza, J. Stakeholders’ perceptions of plant invasions in Galicia, Spain. Asp. Appl. Biol. 2010, 104, 13–18. Available online: https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/id/file/129489 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Csiszár, Á.; Kézdy, P.; Korda, M.; Bartha, D. Occurrence and management of invasive alien species in Hungarian protected areas compared to Europe. Folia Oecologica 2020, 47, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straka, T.M.; Bach, L.; Klisch, U.; Egerer, M.H.; Fischer, L.K.; Kowarik, I. Beyond values: How emotions, anthropomorphism, beliefs and knowledge relate to the acceptability of native and non-native species management in cities. People Nat. 2022, 4, 1485–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindaru, C.L.; Nita, R.M. Methods of Including Invasive Species Research in Urban Planning-A Case Study on Ailanthus altissima. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, R.; Lapin, K.; Bindewald, A.; Vaz, A.S.; Marinšek, A.; La Porta, N.; Detry, P.; Berger, F.; Barič, D.; Simčič, A.; et al. Balancing Risks and Benefits: Stakeholder Perspective on Managing Non-Native Tree Species in the European Alpine Space. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2024, 29, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I.; Straka, T.M.; Lehmann, M.; Studnitzky, R.; Fischer, L.K. Between approval and disapproval: Citizens’ views on the invasive tree Ailanthus altissima and its management. NeoBiota 2021, 66, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Llorente, M.; Martín-López, B.; González, J.A.; Alcorlo, P.; Montes, C. Social perceptions of the impacts and benefits of invasive alien species: Implications for management. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2969–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, R.T.; Larson, B.M.; Novoa, A.; Richardson, D.M.; Kull, C.A. The human and social dimensions of invasion science and management. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 229, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleespies, M.W.; Dörge, D.D.; Peter, N.; Schantz, A.V.; Skaljic, A.; Feucht, V.; Burger-Schulz, A.L.; Dierkes, P.W.; Klimpel, S. Identifying opportunities for invasive species management: An empirical study of stakeholder perceptions and interest in invasive species. Biol. Invasions 2024, 26, 2561–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selge, S.; Fischer, A.; van der Wal, R. Public and professional views on invasive non-native species–A qualitative social scientific investigation. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 3089–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humair, F.; Kueffer, C.; Siegrist, M. Are non-native plants perceived to be more risky? Factors influencing horticulturists’ risk perceptions of ornamental plant species. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, R.A.; Anderson, C.B.; Pizarro, J.C.; Burgman, M.A. Clarifying values, risk perceptions, and attitudes to resolve or avoid social conflicts in invasive species management. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Llorente, M.; Martín-López, B.; Nunes, P.A.; González, J.A.; Alcorlo, P.; Montes, C. Analyzing the social factors that influence willingness to pay for invasive alien species management under two different strategies: Eradication and prevention. Environ. Manag. 2011, 48, 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbrugge, L.N.; Van den Born, R.J.; Lenders, H.R. Exploring public perception of non-native species from a visions of nature perspective. Environ. Manag. 2013, 52, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.P.; Charnley, S. Private forest owners and invasive plants: Risk perception and management. Invasive Plant Sci. Manag. 2012, 5, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Clarke, M.; Ma, Z.; Snyder, S.A.; Hennes, E.P. Understanding invasive plant management on family forestlands: An application of protection motivation theory. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 286, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapitza, K.; Zimmermann, H.; Martín-López, B.; Von Wehrden, H. Research on the social perception of invasive species: A systematic literature review. NeoBiota 2019, 43, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Forestry Inventory Database, Forest Areas by Sector. 2018. Available online: https://foldalap.am.gov.hu/download.php?id_file=40406 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- National Forestry Inventory Database, Forest Areas by Sector. 2019. Available online: https://foldalap.am.gov.hu/download.php?id_file=41503 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Babbie, E.R. The Practice of Social Research, 13th ed.; Wadsworth Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P. Beasts or beauties? Laypersons’ perception of invasive alien plant species in Switzerland and attitudes towards their management. NeoBiota 2016, 29, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, A.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Fried, J.; Vimercati, G. Does public awareness increase support for invasive species management? Promising evidence across taxa and landscape types. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 3691–3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, B.; Marchante, H.; Castro, P.; Marchante, E. Does public awareness about invasive plants pays off? An analysis of knowledge and perceptions of environmentally aware citizens in Portugal. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 2267–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, L.J.; Gaertner, M.; O’Farrell, P.J.; Richardson, D.M. Perceptions of impact: Invasive alien plants in the urban environment. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 229, 7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fejes, Z.; Vadász, C.; Andrési, D.; Tormáné Kovács, E. Konfliktusok és közös pontok feltárása a Peszéri-erdő főbb érintett csoportjai között az OAKEYLIFE Projekt kapcsán. Tájökológiai Lapok 2023, 21, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, S.; Czóbel, S.; Ábrám, Ö.; Tormáné Kovács, E. Perception of local stakeholder groups about certain invasive alien bee pasture species around Lake Kolon. Tájökológiai Lapok 2024, 22, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszár, Á.; Korda, M. (Eds.) Practical Experiences in Invasive Alien Plant Control. Rosalia Handbooks; Duna–Ipoly National Park Directorate: Budapest, Hungary, 2015; 241p, ISBN 978-615-5241-16-1. Available online: https://www.dunaipoly.hu/uploads/2016-02/20160202200313-rosalia-handbook-ver2-6xtoafsq.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Miles, H.H.; Salom, S.; Shively, T.J.; Bielski, J.T.; McAvoy, T.J.; Fearer, C.J. A review of potential biological controls for Ailanthus altissima. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2025, 118, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, A.; Sarlós, D.; Skutai, J.; Tirczka, I.; Ónodi, G.; Czóbel, S. Kiválasztott özönfajok gazdasági szempontú értékelése—A fehér akác és a mirigyes bálványfa. Tájökológiai Lapok 2015, 13, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peugh, C.M.; Bauman, J.M.; Byrd, S.M. Case study: Restoring remnant hardwood forest impacted by invasive tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima). J. Am. Soc. Min. Reclam. 2013, 2, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.D.; Haubrock, P.J.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Heringer, G.; Kourantidou, M.; Hudgins, E.J.; Angulo, E.; Diagne, C.A.; Courchamp, F.; Nuñez, M.A. Underexplored and growing economic costs of invasive alien trees. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, E.; Harangozó, G.; Marjainé Szerényi, Z.; Csépányi, P. Natura 2000 erdők közgazdasági környezetének elemzése; Duna-Ipoly Nemzeti Park Igazgatóság: Esztergom, Hungary, 2015; 215p, Available online: https://unipub.lib.uni-corvinus.hu/2190/1/life_in_forests2015.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Scalera, R. How much is Europe spending on invasive alien species? Biol. Invasions 2010, 12, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piria, M.; Copp, G.H.; Dick, J.T.; Duplić, A.; Groom, Q.; Jelić, D.; Lucy, F.E.; Roy, H.E.; Sarat, E.; Simonović, P.; et al. Tackling invasive alien species in Europe II: Threats and opportunities until 2020. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2017, 8, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunel, S.; Brundu, G.; Fried, G. Eradication and control of invasive alien plants in the M editerranean Basin: Towards better coordination to enhance existing initiatives. EPPO Bull. 2013, 43, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitani, N.; Shivambu, T.C.; Shivambu, N.; Downs, C.T. An impact assessment of alien invasive plants in South Africa generally dispersed by native avian species. NeoBiota 2022, 74, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).