Abstract

Historic urban alleys encapsulate cultural identity and collective memory but are increasingly threatened by commercialization and context-insensitive redevelopment. Preserving their authenticity while enhancing environmental resilience requires design strategies that integrate both heritage and ecological values. This study explores the potential of generative artificial intelligence (AI) to support biophilic design in historic alleys, focusing on Daegu, South Korea. Four alley typologies—path, stairs, edge, and node—were identified through fieldwork and analyzed across cognitive, emotional, and physical dimensions of place identity. A Flux-based diffusion model was fine-tuned using low-rank adaptation (LoRA) with site-specific images, while a structured biophilic design prompt (BDP) framework was developed to embed ecological attributes into generative simulations. The outputs were evaluated through perceptual and statistical similarity indices and expert reviews (n = 8). Results showed that LoRA training significantly improved alignment with ground-truth images compared to prompt-only generation, capturing both material realism and symbolic cues. Expert evaluations confirmed the contextual authenticity and biophilic effectiveness of AI-generated designs, revealing typology-specific strengths: the path enhanced spatial legibility and continuity; the stairs supported immersive sequential experiences; the edge transformed rigid boundaries into ecological transitions; and the node reinforced communal symbolism. Emotional identity was more difficult to reproduce, highlighting the need for multimodal and interactive approaches. This study demonstrates that generative AI can serve not only as a visualization tool but also as a methodological platform for participatory design and heritage-sensitive urban regeneration. Future research will expand the dataset and adopt multimodal and dynamic simulation approaches to further generalize and validate the framework across diverse urban contexts.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Purpose

Urban streets and alleys embody the history, culture, and communal life of a region, encapsulating distinctive identities and collective memories. In particular, historic–cultural landscapes shaped during the modernization process represent complex layers that extend beyond physical structures, incorporating accumulated social events and architectural styles over time. These layers provide a unique sense of placeness, organizing urban life, mediating social relations, and serving as cultural landscapes that reproduce regional identity [1,2].

The cultural value of historic alleys has been increasingly reappraised in recent years, establishing them as strategic assets for tourism, regeneration, and urban branding. In particular, Daegu, South Korea, has developed a distinctive street culture within its historic core, shaped by governmental offices, religious institutions, and heritage sites associated with nationalist movements during the Japanese colonial period [3]. In response, the city has introduced cultural tourism initiatives, such as the Historical and Cultural Streets Tours, which strategically leverage visual traces and historical placeness as urban marketing resources [4].

However, the original character of Daegu’s alleys has been increasingly threatened by tourism-oriented commercialization and uncontextual visual interventions, often leading to the erosion of authenticity and rupture of historical continuity. As critics note, preservation alone is insufficient to ensure the sustainability and resilience of these spaces [5]. Place identity is not merely a function of visual elements or building materials, but is formed through layered sensory and experiential dimensions encompassing memory, emotion, and behavior [6]. Consequently, urban environments face a dual tension: the simultaneous demands of preserving identity and enhancing environmental quality.

Against this backdrop, biophilic design has emerged as a promising approach to reintegrate human–nature relationships into design and promote restoration [7]. Biophilic design refers to the intentional incorporation of natural elements, patterns, and processes into the built environment to enhance human well-being and foster emotional connections with nature [8,9]. Yet a critical question remains: how does nature operate within historic and cultural urban landscapes? Traditionally framed in planning as a source of comfort or decorative value [7], nature in historic and cultural contexts fulfills multiple, interdependent functions:

- Memory and emotional restoration: Elements such as greenery, water, shade, and wind evoke collective memories and facilitate emotional recovery at both individual and communal levels [10,11]. In historic contexts, natural features reinforce temporal continuity by evoking past experiences [12].

- Place attachment and sensory immersion: Seasonal vegetation, water features, and variations in natural light foster sensory immersion and reinforce emotional attachment to place [13,14].

- Harmonization of landscape tensions: Vegetation-based interventions, including green façades and permeable pavements, can mediate tensions between conservation and contemporary development, thereby maintaining visual coherence and contextual integration [15,16].

Thus, biophilic design in historic and cultural landscapes should extend beyond functional comfort, operating as a strategic design intervention that preserves place identity while enhancing emotional resilience. This necessitates a contextual approach grounded in memory, form, and symbolism.

To address this complexity, generative artificial intelligence (AI) offers new opportunities for predictive experimentation and visual simulation in design. Generative image models translate textual prompts into visual outputs after being trained on large-scale datasets [17]. With additional fine-tuning through low-rank adaptation (LoRA) [18], these models can be specialized for specific themes or contexts. Integrating generative AI with LoRA fine-tuning enables efficient learning of typological visual data and facilitates the simulation of design interventions in urban environments. This process serves both as a predictive design tool and as a visual platform for public engagement and feedback.

However, recent studies caution that mainstream AI models such as ChatGPT and Midjourney often fail to adequately capture cultural diversity and place-specific identities, particularly in non-Western contexts [19,20]. Campo-Ruiz [19], for instance, argues that these models tend to generate imagery biased toward iconic landmarks or commercialized urban culture, thereby diminishing cultural authenticity and reinforcing urban inequalities. Similarly, Jang et al. [20] emphasized that although generative AI holds potential for visualizing place identity, the quality of representation is contingent upon the cultural scope of training data, which often excludes or oversimplifies the particularities of non-Western cities.

Therefore, using AI to preserve place identity in historic and cultural landscapes should not remain a purely technical exercise. It requires a design approach that integrates urban and architectural contexts with cultural identity and restorative spatial experiences. The historic alleys of Daegu, shaped by modernization and enriched with both physical features and sensory memories, provide a clear example of where such an approach is both necessary and timely.

The present study analyzes the elements of place identity embedded in Daegu’s “Historic Modern Culture Alley” and explores their integration with biophilic design attributes through generative AI simulations. By doing so, it aims to reconcile identity preservation with emotional resilience, providing new insights into the design and regeneration of culturally significant urban environments.

1.2. Research Aim and Questions

This study investigates design strategies that balance place preservation and restorative potential in Daegu’s historic alleys by analyzing their cognitive, emotional, and physical elements and integrating these with biophilic design attributes through generative simulations. Specifically, a Flux-based LoRA model was employed to generate alley landscape images, followed by the application of biophilic design prompts to create intervention scenarios. The resulting outputs were evaluated through quantitative metrics and expert assessments, offering empirical insights into reconciling identity preservation with emotional restoration in historic urban landscapes.

The study addresses the following research questions (RQs):

- (1)

- How can the cognitive, emotional, and physical components of place identity in Daegu’s historic alleys be represented through visual imagery?

- (2)

- What biophilic design strategies are most appropriate for historic cultural landscapes in Daegu, and how do these strategies contribute to both the preservation of identity and the realization of restorative experiences?

- (3)

- To what extent can generative AI serve as an effective tool for designing biophilic alley landscapes grounded in place identity, and what are its limitations?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Place Identity of Cultural Landscape and Urban Alley

The concept of place identity was first articulated by environmental psychologist Proshansky et al. [21], who defined it as “cognitions about the physical world in which the individual lives.” This perspective highlights that place identity is not merely a reflection of subjective awareness, but emerges from the interplay of physical, symbolic, institutional, and social dimensions [22]. Relph [12] and Paasi [23] broadened the concept, viewing place identity as a composite structure that integrates nature, culture, and everyday life to differentiate one locality from another. Similarly, Groote and Haartsen [24] conceptualize place identity as the outcome of the interaction between physical and artificial structures, systems of meaning, and social signifiers. Collectively, these perspectives emphasize that place identity is not a fixed entity but a fluid and multi-layered cultural construct that is continually reconstituted through time and context.

Synthesizing prior scholarship, place identity can be understood across three interrelated dimensions:

- Cognitive elements: Spatial perception, sense of orientation, and interpretation of symbolic meanings.

- Emotional elements: Attachment, familiarity, belonging, and psychological mechanisms tied to identity formation.

- Physical elements: Landscape structures, architectural styles, materials, spatial organization, and visual markers.

These three dimensions do not operate independently but interact dynamically. In historic urban places, past experiences and collective memories intersect with present emotional and physical environments, generating a multi-layered and evolving reproduction of place identity.

Place identity is also closely tied to the spatial composition of urban landscapes. Lynch [25] identified five key elements contributing to the imageability of cities—paths, edges, nodes, districts, and landmarks—illustrating how citizens perceive and structure urban form. Among these, paths, edges, and nodes constitute critical components in alley landscapes, mediating place experience through cognitive mapping, perception of boundaries, and recognition of transitional points. In this study, alleys are interpreted as district units with a unique identity, further distinguished by surrounding landmarks that enhance visibility and character. Within these districts, the configuration of paths (e.g., non-linear flows, directional guidance), edge elements (e.g., walls, vertical differences), and nodes (e.g., corners, small squares, spaces of interaction) serve as key visual cues shaping the place identity of alleys.

2.2. Biophilic Design Theory and Urban Landscape Application

Biophilic design is a design paradigm grounded in the premise that emotional and psychological connections with nature can enhance human health and well-being [7]. It offers human-centered principles for urban environments, moving beyond conventional approaches that focus on the physical incorporation of natural elements. Instead, it emphasizes the integration of cultural context and sensory experience, thereby fostering what may be termed placial naturalness—a sense of naturalness embedded in the unique cultural and spatial context of a place [26]. Therefore, biophilic interventions in urban alleys are significant as strategies to sustain place identity while enhancing cultural and ecological resilience.

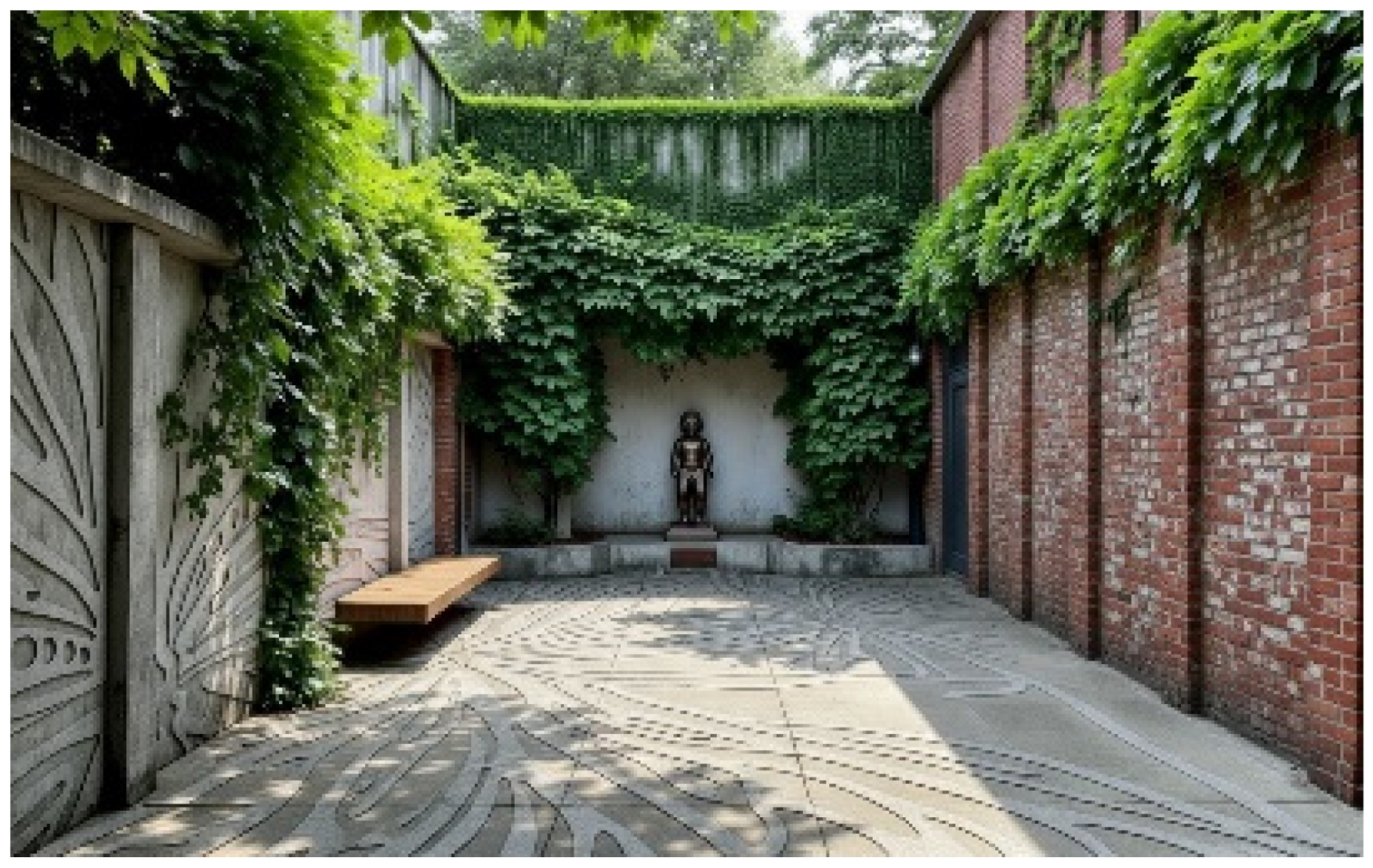

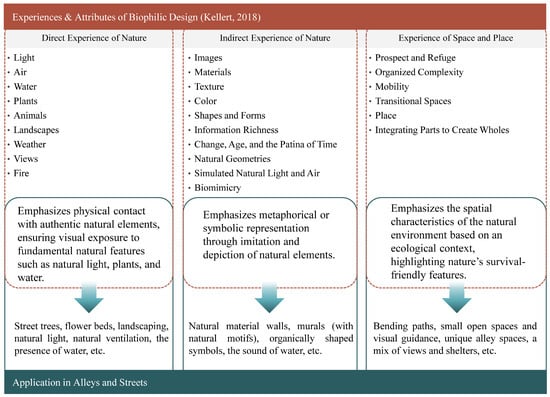

Kellert [8] conceptualized biophilic design within three broad categories of experience, further specified into 25 design attributes (Figure 1). Direct experience of nature involves incorporating actual natural elements, such as street trees, potted plants, or architectural openings that allow natural light to enter alleys. Indirect experience of nature refers to the use of materials, patterns, and colors that mimic natural qualities, including patterned façades, the use of wood or stone, and soundscapes evocative of natural environments. Experience of space and place highlights spatial and cognitive experiences, exemplified by alley curvatures, courtyards, or vantage points that shape one’s engagement with the environment.

Figure 1.

Biophilic design framework and application implications in urban landscape (adapted from Kellert, 2018 [8]).

Biophilic design has been increasingly applied in diverse urban pedestrian spaces, parks, and alleyways as a practical strategy to enhance psychological and emotional resilience. Common approaches include maximizing daylight penetration, increasing greenery, and applying natural materials or patterns. These interventions are associated with a range of positive outcomes, such as emotional stability, attentional restoration, and the facilitation of social interaction [9]. Depending on the spatial context, biophilic design operates in different ways, producing varied effects. Importantly, by introducing narrative, experiential, and memorable qualities, it enables spaces to be recognized as places, thereby mirroring the structural role of place-making factors [15].

This study links Kellert’s three categories and their sub-attributes to the cognitive, emotional, and physical dimensions of place identity in historic-cultural landscapes. Through this conceptual mapping, it seeks to derive context-based strategies for biophilic design. These strategies are subsequently embedded into generative AI prompts, enabling experimental design scenarios that integrate place identity with naturalness and allow for simulation-based exploration.

2.3. LoRA Model and Prompt Framework for Landscape Visualization

Generative image AI has gained attention as a powerful medium that enables the exploration of emotional connections between users and spaces, as well as combinations of landscapes through scenario-based simulations. In particular, diffusion-based AI models [27] are capable of mapping textual prompts to image data, thereby producing high-resolution imagery that facilitates experimental inquiry into diverse design scenarios.

Building on this development, this study employs a Flux-based LoRA model. Flux, a state-of-the-art text-to-image model, performs better than conventional diffusion models due to its efficient memory structure and enhanced visual fidelity [28]. Notably, it excels in rendering contextual details such as texture, light, and spatial depth [28,29], making it particularly suitable for landscapes with layered meanings and embedded place identity, such as historic alleys.

Furthermore, advances in LoRA techniques have further enabled the use of relatively small datasets to train models according to specific user intentions or stylistic requirements [18]. LoRA adapts only a subset of low-rank parameters rather than retraining the entire weight set, thereby enabling efficient learning of specific styles or attributes from small datasets [28]. This advancement allows for the customization of models to reflect localized landscapes or place-specific identities.

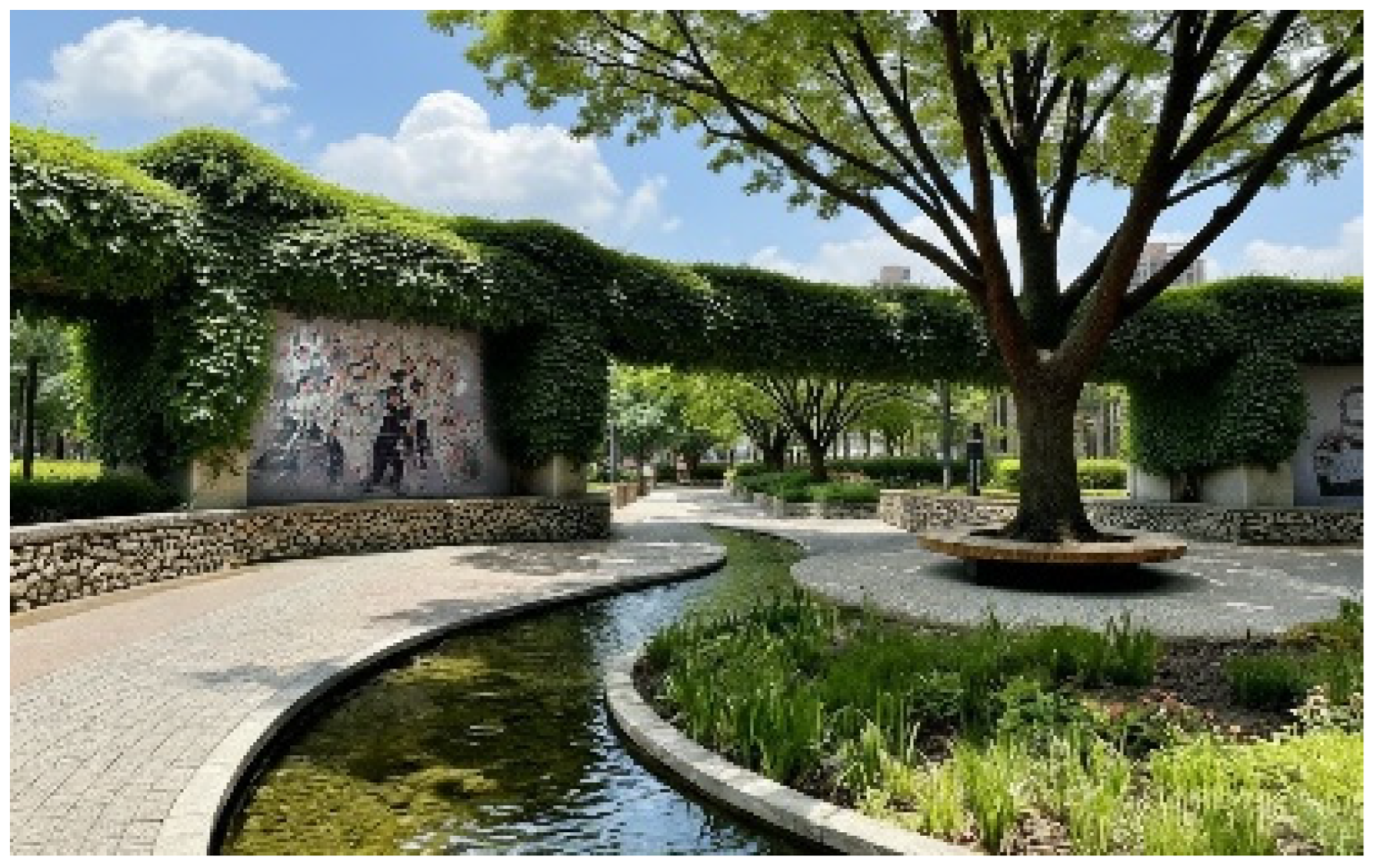

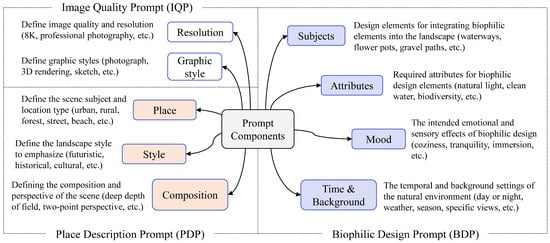

Nevertheless, the quality of generative AI outputs is strongly influenced not only by model architecture but also by the systematic design of prompts. Lee and Park [17], for instance, proposed a biophilic design prompt framework to guide the application of generative AI in architectural and spatial contexts. Drawing on this approach, the present study adapts and structures prompt components for application within urban-landscape contexts, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structured prompt components for applying biophilic design in urban-landscape contexts.

The prompt framework is organized into three main categories. The image quality prompt (IQP) specifies the resolution and representational style of the generated output (e.g., drawing, isometric view, or photographic rendering). The place description prompt (PDP) defines the scene’s fundamental structure by describing place type, spatial context, and the arrangement of objects. Finally, the biophilic design prompt (BDP) integrates natural elements and emotional experiences into the design process by employing key components such as subjects, attributes, mood, and temporal or background settings [17]. The BDP can be operationalized through interactive strategies that link place identity with biophilic design, thereby serving as a structured design tool for generative AI-based simulations.

2.4. Research Gap and Theoretical Linkage

Although place identity and biophilic design have been widely examined in architecture and urban studies, their integration through generative artificial intelligence remains largely unexplored. Previous studies have typically addressed cultural identity and biophilic enhancement separately, lacking methodological frameworks that connect these domains through data-driven visualization. In particular, the application of AI to visually simulate the coexistence of cultural authenticity and ecological resilience has not yet been systematically tested within urban landscape contexts.

To address this gap, the present study proposes an AI-driven framework that integrates place-identity-based analysis with biophilic design strategies through LoRA fine-tuning and structured prompts. This approach operationalizes cultural and ecological values within generative workflows, providing a methodological foundation for participatory and context-sensitive urban regeneration.

3. Methodology

3.1. Classification of Target and Alley Types

This study focuses on the historic alley landscapes of Jung-gu, Daegu, South Korea. Since the Japanese colonial period, Jung-gu has developed as the city’s center of administration, commerce, and religion, resulting in a concentration of modernized urban functions. Today, it still retains numerous alleys where diverse layers of place identity and visual traces coexist.

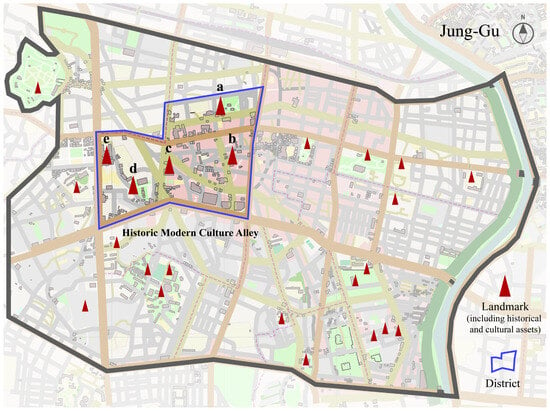

To preserve and utilize these characteristics, the city of Daegu operates the Historical and Cultural Streets Tours, which connect major urban alleys through five designated routes. Among them, this study selects the “Historic Modern Culture Alley” route—an area where cultural and historical landmarks are most concentrated—as the primary research site (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Site map of Jung-gu, Daegu, indicating the “Historic Modern Culture Alley” route and key landmarks (a–e) used to contextualize the four alley typologies. a: Daegu Modern History Museum, b: Yakjeon Jin Alley, c: Gyesan Cathedral, d: 3.1 Independence Movement Stairs, e: Dongsan Missionary Houses.

The study defines the site as a district unit, based on the premise that alleys function not merely as passages but as independent cognitive units with distinctive visual atmospheres and experiential qualities [25]. Within this district, physical and symbolic cues, such as landmarks, make visible the city’s key character.

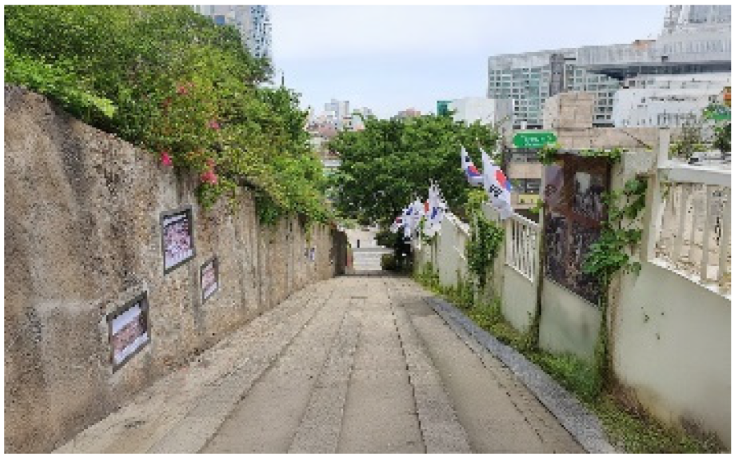

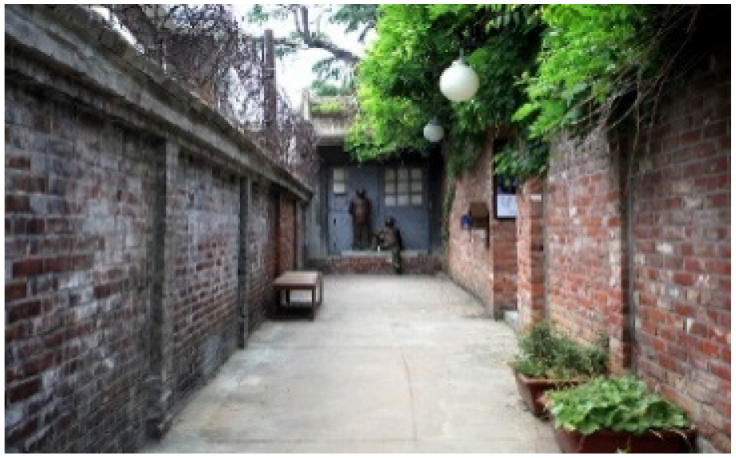

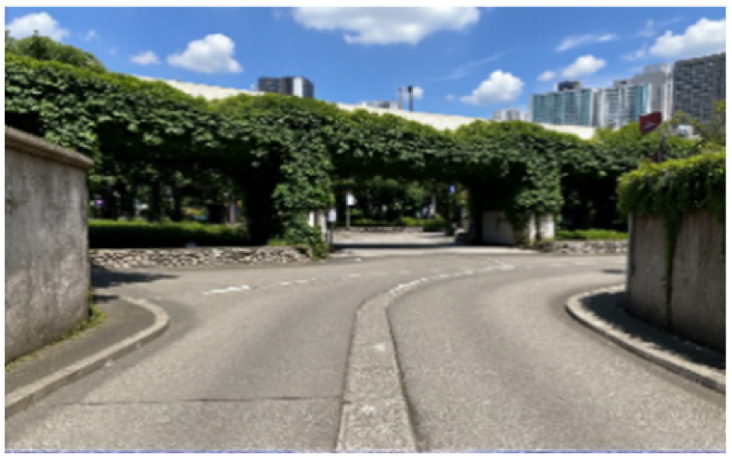

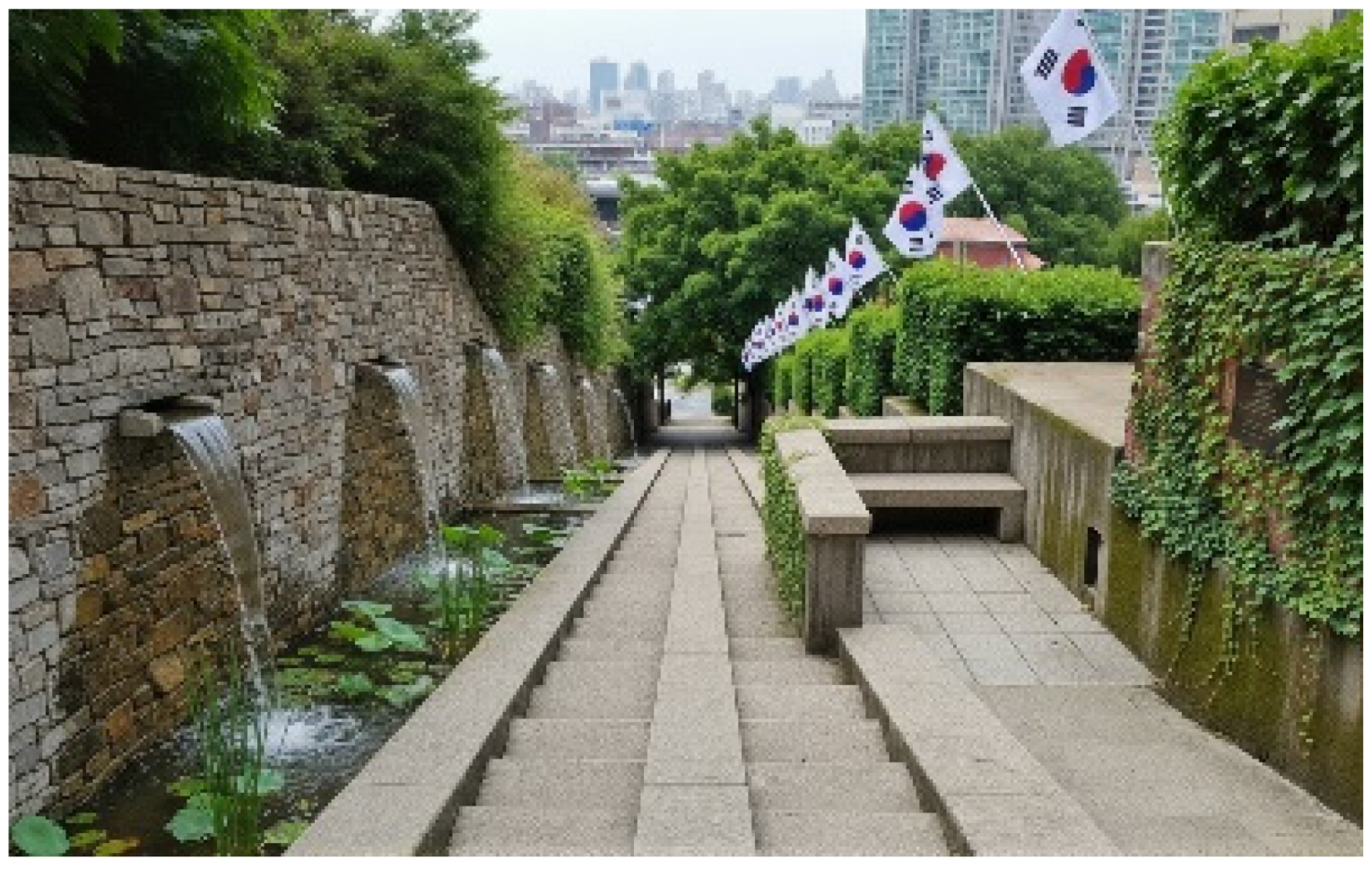

For visual analysis, alley landscapes were further categorized into four types: path, stairs, node, and edge. Stairs, while not included in Lynch’s original framework, were added here due to their distinctive role in vertically connecting routes, reinforcing symbolic meaning, and ensuring functional and visual continuity in historic alleys. Each type is defined as follows:

- Path: The primary circulation axis and cognitive flow of the alley, shaped by its alignment, rhythm, scale, and walking experience. Features such as straightness or curvature, width, and boundary composition directly influence pedestrian perception and movement.

- Stairs: A vertical connector linking horizontal paths, introducing rhythm through gradients and level changes. In historic alleys, stairs often combine with topographic or defensive elements, reinforcing uniqueness while ensuring continuity between upper and lower spaces.

- Edge: Boundaries or transitional zones, typically formed by high walls, enclosed spaces, or dead ends. In historic alleys, materiality, height differences, and wall textures accentuate the perception of enclosure and openness, directly shaping pedestrian experience.

- Node: Points where paths intersect or visual attention converges, often associated with public spaces or clusters of urban functions. Nodes serve as focal areas for gathering and interaction, enhancing both orientation and place identity.

3.2. Dataset Construction and LoRA Training

To ensure consistency in the training dataset, fieldwork was conducted in May 2025, during the same time window (13:00–15:00), to collect images representing the four alley landscape types. All images were captured at human eye level using an iPhone 13, following three criteria:

- Inclusion of key landmarks and visual cues of the study site;

- Clear representation of the spatial configuration and characteristics of each alley type;

- Variation in viewpoints, orientations, and distances within each type.

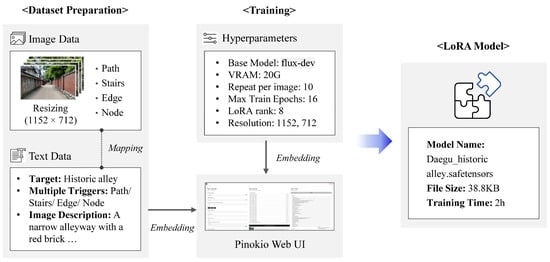

Through this process, a final set of 40 refined images was secured for LoRA model training. All images were preprocessed by resizing to a resolution of 1152 × 712 pixels. Figure 4 illustrates the workflow of the LoRA fine-tuning procedure.

Figure 4.

Workflow of LoRA fine-tuning with the Flux base model, including dataset preparation, captioning with trigger tokens, training stages, and example outputs.

In this study, the preprocessed images were mapped to text captions. Each caption included both a general label (e.g., historic alley) and multiple trigger tokens (e.g., path, node) to distinguish alley landscape types. The use of multi-trigger tokens enhanced the precision and controllability of the fine-tuning process, enabling the trained model to recognize and reproduce subtle structural variations within the same category. This not only improved the model’s sensitivity but also strengthened its ability to generate type-specific images during inference.

Key hyperparameters for fine-tuning were configured using the Pinokio web user interface. To maximize dataset representativeness, potential augmentation techniques were applied, while adopting a conservative configuration: rank = 8, alpha = 16, learning rate = 5 × 10−5, and batch size = 1 with gradient accumulation = 8. Training was performed for 16 epochs, with each image repeated 10 times to ensure data efficiency. These settings effectively balanced variability introduced through augmentation with overfitting control, allowing for stable and reliable model training.

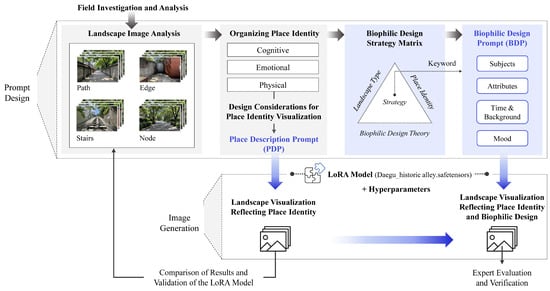

3.3. Prompt Design and AI Image Generation

This study first conducted a field investigation and analysis to classify four alley types—path, stairs, edge, and node. Each spatial characteristic and visual indicator were categorized, and the elements of place identity were systematically organized into cognitive, emotional, and physical dimensions. These served as key considerations for place identity simulation and were incorporated into the construction of the PDP.

In the next step, a biophilic design strategy matrix was developed by aligning the place identity attributes of each alley type with biophilic experience and their sub-attributes. Previous research in architecture and urban planning was referenced to ensure contextual validity. The outcome was a set of keywords linking biophilic design strategies to each alley type. This process addressed a limitation noted in earlier studies [17], in which biophilic prompts often relied on intuition or vague references to natural imagery.

Subsequently, the biophilic design strategies were translated into prompts. Rather than simple keyword lists, these were hierarchically structured around the core components of the BDP (Figure 2). Figure 5 illustrates the workflow for prompt design and image generation.

Figure 5.

Workflow of prompt design and AI image generation.

PDPs and BDPs were combined with the LoRA model to generate alley landscape images that reflect both place identity and biophilic attributes. The image generation process involved two stages. First, PDPs were applied with the LoRA model to create place-identity-based alley images, which were compared with the training dataset to quantitatively evaluate the model’s performance. Second, the validated LoRA model was combined with BDPs to generate place-identity-based images incorporating biophilic interventions. These outputs were then qualitatively assessed through expert evaluation. All image generation and computational processes were conducted on a local PC equipped with an RTX 4090 GPU and 64 GB of memory. Table 1 presents the key parameter settings used for image generation.

Table 1.

Flux configuration settings used for inference.

3.4. Evaluation and Analysis

3.4.1. Image Similarity Evaluation Index

This study generated images using the PDPs derived from the place identity analysis of Daegu’s alley landscapes. Two conditions were compared: (1) images generated using prompts only, and (2) images generated using prompts in combination with the LoRA model. For each alley type, 100 images were generated under each condition, resulting in a total of 800 AI-generated images (400 prompt-only and 400 prompt+LoRA) and 40 ground truth (GT) images collected from fieldwork.

Image quality and similarity were assessed using two complementary metrics: learned perceptual image patch similarity (LPIPS) [30] and fréchet inception distance (FID) [31]. LPIPS measures perceptual distance between individual images by leveraging intermediate feature maps from deep neural networks [30]. In this study, a pre-trained VGG network was used to calculate the perceptual similarity between GT images and the generated images (prompt-only and prompt+LoRA). Lower LPIPS scores indicate smaller perceptual differences, meaning higher visual similarity. Thus, LPIPS served as a key indicator of how faithfully the generated outputs captured the characteristics of real alley landscapes.

FID evaluates differences in feature distributions between two sets of images, providing an index of overall quality and stylistic consistency [31]. Using features extracted from the final pooling layer of a pre-trained Inception-V3 network, FID scores were computed between the GT image set and each generated set. Lower FID scores indicate closer alignment in feature distributions, reflecting that the generated images more accurately reproduced the statistical and structural properties of real alley imagery.

3.4.2. Expert Evaluation

The expert evaluation involved eight professionals selected through purposive sampling based on three criteria: (1) specialization in architecture, landscape architecture, or urban design; (2) at least five years of professional or research experience; and (3) active engagement in spatial visualization or urban regeneration projects. The panel included three architects, three landscape architects, and two urban designers, representing both academic (n = 5) and professional practice (n = 3) backgrounds.

All experts were given a brief orientation on the study’s aims, place identity, and biophilic design framework to establish a shared interpretive basis. They were instructed to assess contextual authenticity and ecological appropriateness rather than aesthetic preference, ensuring consistency across evaluations. We explicitly assumed that participants possessed sufficient professional literacy to evaluate design realism and contextual fit.

The evaluation materials included GT images and AI-generated outputs corresponding to the four alley types. For each type, one GT image and three LoRA-generated images (before/after intervention and one variation) were provided, resulting in a total of 16 images. These were arranged in paired and sequential comparisons to allow experts to intuitively perceive both the preservation and transformation of place identity.

Evaluation indicators were organized into three domains: place identity, biophilic attributes, and the suitability of AI-based simulations. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = very poor, 5 = excellent). In addition to completing itemized evaluations for each image set, the experts were invited to provide open-ended comments. Particular attention was given to collecting qualitative feedback related to the study’s central question—“the balance between preserving place identity and enhancing restorative experiences.” The detailed evaluation framework is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evaluation framework for expert review on AI-based biophilic alley images.

4. Place-Identity-Based Biophilic Design Prompt

4.1. Place Identity Characteristics of Historic Alley Typologies

Table 3 summarizes the place identity of Daegu’s historic alleys by typology. Each alley landscape type reveals distinctive cognitive, emotional, and physical characteristics, which serve as key cues for subsequent visualization and design interventions.

Table 3.

Classification of alley landscape types and their place identity dimensions.

The path type combines linear pedestrian flows with tree canopies and traditional stone or brick walls, producing a clear sense of orientation and stability. Pedestrians experience a steady rhythm and protective enclosure, where consistent walking widths and boundary materials embed local identity and everyday memory.

The stairs type embodies the interplay of vertical transitions and historical context. The act of ascending and descending generates both anticipation and accomplishment, while rough stone textures and shifting shadows intensify embodied immersion. Stairs, often tied to Daegu’s modern history, mediate collective memories associated with historical events.

The edge type represents transitional zones between openness and enclosure. High walls, textured façades, and contrasts of light and shadow accentuate spatial shifts, evoking salience and distinctiveness. Edges thus function as thresholds that transform the atmosphere and sensory perception of alleys.

The node type emerges where paths intersect and people gather, reinforcing both spatial orientation and communal exchange. Through openness and a sense of hospitality, nodes invite lingering, while central trees or sculptures provide symbolic meaning and enhance collective identity.

These typological distinctions serve as critical cues for visualization and design applications, offering a foundation to preserve historic place identity while accommodating new biophilic and regenerative interventions.

4.2. Biophilic Design Strategy Matrix

Table 4 presents a biophilic design strategy matrix for the four alley types in Daegu’s historic district, combining the three layers of place identity with biophilic design attributes. This matrix illustrates which attributes function as critical cues for each type and how specific design interventions can enhance restorative experience and place attachment.

Table 4.

Place-identity–based biophilic design strategy matrix for four alley types.

The path type is characterized by linear pedestrian flows, tree canopies, and the rhythm of boundary walls. Introducing seasonal vegetation along tree lines and walls, together with permeable paving and groundcover, provides pedestrians with both clear orientation and a sense of protection. This strategy moves beyond simple wayfinding by fostering continuous interaction with nature and promoting restorative walking experiences [11,40].

The stairs type reflects the overlap of vertical transitions and historical context. Variations in stair height and wall elevation create sequential vantage points, while green walls and aquatic planting zones enhance visual and ecological diversity. These interventions allow pedestrians to experience both discovery and accomplishment during movement, generating immersive place experiences linked to historical meaning [15,36].

The edge type represents transitional zones where enclosure meets openness. Contrasts of textured walls, climbing vegetation, and dynamic light–shadow patterns emphasize spatial thresholds and produce a heightened sense of distinctiveness. At the same time, vertical greening and habitat provision strengthen ecological diversity and maintain continuity of the historic landscape [9,39].

The node type serves as a center of gathering and exchange. By integrating small resting areas, water features, permeable surfaces, and green infrastructure, nodes are transformed into restorative plazas. These spaces mediate social interaction and collective memory, reinforcing place attachment and enhancing community vitality [13,35].

Although the four types differ in their specific characteristics, several shared principles emerge: (1) visual integration of natural elements, (2) utilization of light and seasonality, (3) preservation of historic materials and textures, and (4) reinforcement of social place identity. Natural elements such as trees, vines, and water features provide orientation and restorative qualities; light and seasonal change reveal spatial dynamism; traditional materials sustain historical authenticity while combining with ecological interventions; and community-oriented devices enhance social attachment.

These strategies provide practical guidelines for urban landscape design that respect historical and cultural contexts while integrating human–nature experiences. Furthermore, the matrix informs generative AI–based biophilic simulation prompts, enabling exploration of restorative and ecological urban visions grounded in historic place identity.

4.3. Prompt Mapping for Biophilic Design Application

Structuring abstract design intentions into executable textual input components is a crucial step to ensure both reproducibility and contextual sensitivity in simulations. Based on the biophilic design strategy matrix, this study developed a structured prompt set (Table 5) to simulate alley landscapes that integrate place identity and biophilic attributes.

Table 5.

Biophilic design prompts (BDP) for generating alley images based on place identity, structured by subject, attributes, time & background, and mood per typology.

Trigger words serve as mediating prompts within the trained LoRA model, specifying alley landscape types and generating their corresponding visual characteristics. The BDP is systematized into four core components—subject, attributes, time & background, and mood—which explicitly embed the cognitive, emotional, and physical layers of place identity. This approach moves beyond a mere listing of keywords by establishing a hierarchical language system that enables generative AI to reflect spatial and cultural cues in a more nuanced manner. For instance, in the path type, “straight path” and “continuity of fence height” express cognitive clarity, while “tree canopy” and “dappled afternoon light” convey emotional protection. Each component is thus mapped to capture the biophilic design subject, attributes, spatiotemporal conditions, and sensory experiences.

Furthermore, the BDPs proposed in this study are not designed as isolated components but rather as interdependent elements that collectively reinforce the expression of place identity. Users can selectively emphasize particular biophilic attributes depending on context—for example, highlighting patterns of light and shadow in one scenario, or emphasizing vegetation networks and water features in another—allowing for comparative analysis across results. Such adaptability demonstrates that the BDP framework functions not only as a visualization tool but also as a platform for participatory design and experimental inquiry.

Ultimately, the structured prompt provides a direct operational linkage between the conceptual strategies of the biophilic design matrix and the generative execution of the AI workflow. By embedding layered attributes into prompt grammar, the framework supports image generation that is both consistent and flexible, thereby enabling subsequent quantitative and qualitative evaluation.

Detailed prompt templates and caption examples used in this process are summarized in Section 5.1 and Section 5.3, illustrating how the structured prompts (PDP, BDP, and IQP) were applied within the AI workflow to generate contextually and visually coherent alley images.

5. AI-Generated Alley Images Results and Evaluation

5.1. Training Stability and Visual Comparison of LoRA-Generated Images

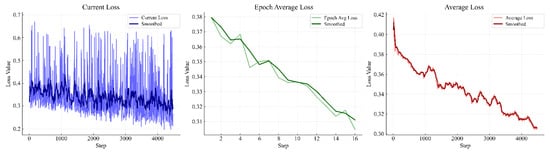

Figure 6 presents the loss curves of the LoRA model trained on images of Daegu’s historic alleys. The average loss, current loss, and epoch-averaged loss all exhibit a steady decline as training progresses, indicating that the model learned the visual and structural characteristics of the alley dataset stably, without excessive oscillation or overfitting. In particular, the stabilization of loss values after several epochs suggests that the LoRA adaptation converged to an optimal state capable of effectively representing alley landscape types such as path, stairs, edge, and node.

Figure 6.

Training loss curves of the LoRA model. The figure shows the current loss, epoch average loss, and average loss across training steps, demonstrating convergence and stability of the model.

Table 6 compares image generation results with and without LoRA training. The PDPs were developed from keywords derived through the place identity analysis of alley types, incorporating simulation considerations and type-specific trigger words. The IQPs consisted of essential terms to ensure the production of high-quality landscape images.

Table 6.

Comparison of place-identity-based image generation results by alley landscape type.

Outputs generated by the prompt-only condition generally lacked contextual fidelity, failing to adequately reflect the distinctive visual characteristics of Daegu’s historic alleys. In contrast, prompt+LoRA-based outputs demonstrated strong alignment with the intended alley types. For example, the path type faithfully preserved the rhythm of stone and brick boundary walls, while the stairs type captured not only the texture and rhythm of steps but also historical details such as the national flags and commemorative plaques. The edge type highlighted tall boundary walls and transitional effects, whereas the node type represented symbolic landmarks and open community spaces.

These results provide a strong foundation for subsequent quantitative evaluations and for applying biophilic design prompts.

5.2. Quantitative Evaluation of Image Fidelity and Structural Similarity

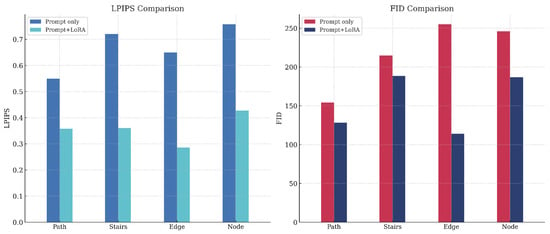

To evaluate whether the LoRA model effectively captured the place identity of the four alley types, quantitative analyses were conducted using LPIPS and FID (Figure 7). Detailed numerical results for each alley type, including mean ± SD and effect sizes, are provided in Table A1 (Appendix A), which further confirms the substantial improvements achieved through LoRA fine-tuning.

Figure 7.

Comparison of LPIPS and FID between prompt-only and prompt+LoRA across four typologies; lower scores indicate better perceptual and distributional alignment with GT images.

The results consistently showed lower LPIPS scores for LoRA-based outputs across all types, indicating better perceptual alignment with the GT images. Since LPIPS reflects human-perceived visual similarity, this suggests that LoRA training did not merely refine textures and forms but also internalized subtle contextual elements such as patterns of light and shadow, temporal traces of materials, and symbolic cues. This finding is particularly meaningful given that place identity is rooted less in geometric accuracy and more in experiential and perceptual authenticity.

The FID scores further confirmed these results. Lower FID values for LoRA-based outputs demonstrated that the statistical feature distributions of generated images became more closely aligned with those of the real dataset. This indicates that LoRA captured not only individual attributes but also the overall diversity and contextual richness of alley scenes. Distributional fidelity is essential to prevent generative outputs from becoming homogenized while preserving contextual variability.

Taken together, these results show that the LoRA-based approach improved both image-level perceptual similarity and dataset-level statistical fidelity. This dual improvement underscores the reliability and validity of the proposed method, providing a solid foundation for the subsequent application of biophilic design prompts and expert evaluations.

5.3. Generative Results Integrating Place Identity and Biophilic Design

This section reports the outcomes of integrating the BDP with the validated LoRA model. The analysis investigates whether structured prompts can embed ecological attributes without undermining the historical and cultural identity of the four alley types. The generative results of place-identity-based biophilic design interventions are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Examples of LoRA+BDP-driven generations by typology, showing prompts and resulting images that embed ecological attributes while preserving identity.

The analysis shows that the BDP maintained contextual fidelity while enhancing the restorative dimensions of the generated images. For the path type, climbing vines along walls, seasonal vegetation, and light filtered through tree canopies enriched the sense of linear perspective. While preserving the historic rhythm of fences and tiled roofs, the images conveyed continuity and calmness, reinforcing both clarity and restorative qualities.

For the stairs type, vine planting, sound-buffering trees, and water features—such as cascades and channels along stone retaining walls—softened the rigid geometric form of stairs. These elements introduced visual and auditory stimuli derived from vegetation and water, creating a more immersive and dynamic atmosphere. Mid-landing spaces for outlook and rest further highlighted the prospect-and-refuge qualities of biophilic design, balancing anticipation and ecological richness.

The edge type was transformed through vertical greening, rain gardens, and patterned paving, softening its closed boundary into a semi-open transitional space. Serving as a distinctive place where historical traces coexist with ecological renewal, the edge type offered new emotional experiences by integrating heritage markers with environmental functions.

The node type emphasized symbolic and communal functions by integrating canopy shading, communal seating, water channels, and permeable paving. The central plaza evolved into a space of both cultural symbolism and biophilic coherence, where ecological forms and water features were combined to highlight collective identity and restorative capacity.

In summary, restorative experiences diverged between linear spaces (path/stairs) and nodal spaces (edge/node). Linear spaces primarily strengthened individual cognitive stability and bodily immersion, while nodal spaces reinforced emotional attachment and communal identity. These results demonstrate that AI-based simulation not only translates place identity into design cues but also explores how such cues interact to generate new forms of restorative experience.

5.4. Expert Evaluation of Place-Identity-Based Biophilic Design

An expert evaluation was conducted to assess the generated alley images. Internal consistency was examined using Cronbach’s α [41], and inter-rater agreement was tested using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) based on a two-way random-effects model with absolute agreement [42].

The results showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.83) and high inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.86), indicating satisfactory agreement among the eight experts. These findings confirm that the expert assessments were statistically consistent and dependable. A summary of the expert evaluation results for place identity and biophilic design is provided in Table 8.

Table 8.

Summary of expert evaluation results.

Overall, LoRA+BDP images received consistently positive assessments, with most items scoring above 4.0 on average. Particularly high ratings were observed for physical place identity (4.10 ± 0.80) and biophilic design effectiveness (4.22 ± 0.79), indicating that experts considered the outputs to be both materially authentic and ecologically enriched.

By type, path and node received the most favorable evaluations. These types effectively integrated vegetation, daylight, and communal features, thereby reinforcing both cognitive clarity and emotional bonding, while also highlighting symbolic meaning. The stairs type was positively evaluated for physical realism and rhythmic immersion, with mid-landing viewpoints and water features contributing to memorable spatial qualities. However, its biophilic fidelity was rated comparatively lower, likely due to structural constraints of stair spaces limiting design variability. This limitation, however, represents a potential area for refinement through more sophisticated prompt design and model improvement. In contrast, the edge type scored highest in biophilic fidelity (4.25 ± 0.89) but lowest in emotional place identity (3.58 ± 0.74). Experts noted that the closed boundary conditions tended to encourage overly dense application of biophilic elements, suggesting the need for additional training on appropriate proportionality between spatial scale and design attributes.

Across categories, emotional place identity received relatively lower scores (3.98 ± 0.86) but still remained above average. Experts emphasized that the emotional dimension is inherently the most challenging for AI to capture; nevertheless, the results demonstrated meaningful representation and significant potential for future enhancement. Iterative refinement of prompt design and model training was considered key to improving these outcomes further.

Experts also underscored the practical applicability of LoRA+BDP results. The “AI applicability” item was rated at 4.06 ± 0.76, suggesting that the generated images hold stable utility beyond specific alley types. Beyond quantitative scores, experts highlighted the usefulness of these images as visual negotiation tools in early-stage design exploration, participatory workshops, and educational settings. Although not a substitute for detailed design drawings, the outputs were recognized as valuable tools for stimulating creativity, visualizing alternatives, and facilitating stakeholder communication.

6. Discussion

6.1. Reproducing Place Identity Through LoRA Training

The LoRA fine-tuning in this study showed that generative AI can reproduce the cultural and spatial attributes that constitute the place identity of historic alleys. Unlike prompt-only outputs, which tended to produce generic images lacking contextual specificity, LoRA-based outputs consistently retained typological cues that reflect the multi-layered characteristics of the urban fabric. This indicates that fine-tuning functions as a methodological device capable of embedding local knowledge into the data-driven generative process.

The LoRA-generated images accurately represented both the physical and symbolic dimensions of place identity. Physical attributes—such as the rhythm of stone and brick walls, stair textures, and boundary forms—were faithfully reproduced, while cognitive and relational cues—such as transitional edges and communal landmarks—were also expressed. This suggests that LoRA internalized not only surface visual patterns but also the underlying structural logics sustaining each type. As a result, the model produced outputs aligned not only with external resemblance but also with the cognitive and cultural dimensions of place identity.

Quantitative metrics further supported these findings: lower LPIPS values and improved FID scores indicated greater perceptual and statistical consistency with GT images. These outcomes are consistent with recent empirical studies reporting that context-aware fine-tuning enhances perceptual realism and the retention of typological cues in architectural or heritage imagery. For instance, LoRA-based adaptations have improved the cultural specificity and visual fidelity of place-dependent subjects [28], while identity-oriented generation studies show that tailoring models to local data reduces generic outputs and strengthens contextual alignment [20].

Taken together, LoRA fine-tuning provides a robust methodological foundation for adapting generative AI to urban-heritage contexts. By stably reproducing place-identity cues, LoRA establishes the conditions necessary for integrating biophilic design prompts and verifying applicability in design practice.

6.2. Integrating Biophilic Strategies Through Structured BDP

This study reconceptualized place identity not only as a set of physical features to be preserved but as design cues translatable into biophilic attributes. The structured BDP provided a systematic framework for embedding ecological qualities into alley typologies while reinforcing their cultural and spatial identities.

Results showed distinct effects: path emphasized continuity and clarity through vegetation and light; stairs deepened immersion with vertical greening and water features; edge transformed rigid boundaries into interpretive spaces with greenery and light gradients; and node highlighted symbolism and communal identity through green and water elements. These findings demonstrate that linear spaces (path, stairs) primarily strengthen individual clarity and immersion, while nodal spaces (edge, node) reinforce emotional attachment and collective identity.

These typology-specific patterns are consistent with empirical findings in biophilic and restorative urban design research. Previous studies have shown that vegetation, natural lighting, and visual openness enhance orientation, attentional focus, and perceived safety in linear environments such as streets and corridors [40,43,44]. In contrast, water features, tree canopies, and small plazas have been empirically linked to greater social interaction, emotional bonding, and collective memory formation at nodal urban spaces [45,46]. Furthermore, research on material texture and rhythmic light–shadow variation indicates that such sensory attributes foster perceptual coherence and restorative experiences by mediating visual complexity and natural pattern recognition [15,47]. Collectively, these empirical insights support the present study’s findings that biophilic attributes embedded in different alley typologies can simultaneously reinforce cognitive clarity and affective attachment within culturally significant environments.

Building upon these empirical implications, the proposed BDP framework extends such evidence into a generative design context, offering a practical means to simulate and evaluate biophilic interventions through AI. The methodological value of the BDP lies in its modularity and adaptability. Prompts can simulate seasonal variation or emphasize specific design variables, enabling generative AI to function not as a static visualization tool but as an experimental platform for testing biophilic interventions under varying contextual conditions.

6.3. Evaluating Reliability and Applicability of AI-Generated Images

In terms of effectiveness, consistent improvements in LPIPS and FID confirmed that LoRA-based images enhanced both perceptual authenticity and statistical fidelity. Experts also rated AI applicability positively (4.06 ± 0.76), suggesting that the proposed approach can serve as a practical tool in early design exploration. Notably, LoRA+BDP images not only reproduced historic alley features but also introduced biophilic attributes without undermining cultural specificity. Path and node types excelled in cognitive clarity and communal symbolism, stairs in physical realism and immersive experience, and edge type in biophilic fidelity. These results indicate that generative AI can strengthen historic and cultural identity by enriching spatial variation and experiential depth.

Nevertheless, several limitations were observed. Experts highlighted the restricted expression of emotional place identity, reflecting the inherent difficulty of reproducing affective resonance, symbolic associations, and personal memories through static imagery. Because emotional identity is closely tied to lived experience, future work should integrate 3D simulation and immersive technologies to better convey spatial presence. Furthermore, the reliance of generative AI on training data and prompt design introduces risks of visual oversimplification and cultural misrepresentation. If uncritically adopted as design output, such results may distort both research and practice. To address these issues, four measures are proposed:

- (1)

- Expand multi-city and multicultural datasets to mitigate contextual bias.

- (2)

- Present multiple alternative scenarios in parallel to avoid overreliance on single outcomes.

- (3)

- Incorporate expert and citizen feedback loops to critically validate AI-generated results.

- (4)

- Ensure transparency in data sources and prompt design, enhancing trust and accountability in interpretation.

In sum, generative AI demonstrates clear potential as an exploratory tool for biophilic alley design grounded in place identity, enabling typology-specific strategies. However, its application requires contextual validation and critical interpretation, particularly to overcome limitations in representing emotional and symbolic dimensions. Accordingly, LoRA+BDP simulation should be viewed as a mediating platform that balances identity preservation with restorative design interventions in urban regeneration, offering essential insights for the responsible integration of AI into architectural practice.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Contributions and Novelty

This study contributes to both theoretical and practical domains at the intersection of place identity, biophilic design, and generative AI.

Theoretically, three methodological innovations are proposed. First, LoRA fine-tuning was shown to effectively reproduce typological cues of place identity, capturing not only material realism but also symbolic resonance beyond mere visual similarity. Second, the study proposed a structured BDP framework that translates conceptual design strategies into modular prompt components, systematically embedding ecological attributes into AI simulations. Third, by integrating quantitative similarity indices with expert evaluation, a multi-layered verification framework was established, enhancing the reliability of generative outputs and offering a transferable methodology for future studies. Collectively, these contributions position generative AI as a third pathway for urban regeneration—beyond the dichotomy between physical preservation and modern intervention—by enabling a simulated balance between identity conservation and restorative design.

Practically, the study demonstrates the potential of AI-generated alley images as decision-support and participatory tools for design and planning. The framework provides a visual and analytical basis for testing design alternatives in heritage-sensitive contexts, helping practitioners communicate design intentions and evaluate ecological and cultural trade-offs. The findings are applicable not only to Daegu’s historic alleys but also to similar neighborhoods undergoing regeneration, where cultural heritage must coexist with ecological enrichment. Typology-specific insights further reveal differentiated spatial values: path enhances legibility and continuity, stairs support immersive sequential experiences, edge transforms rigid boundaries into ecologically enriched transitional spaces, and node reinforces symbolism and communal identity.

Overall, this study presents a novel attempt to position generative AI as both a methodological and practical platform that harmonizes cultural specificity with biophilic strategies. By linking theoretical constructs with design experimentation, it establishes a foundation for applying generative AI in heritage-sensitive urban regeneration and for guiding future interdisciplinary approaches that connect artificial intelligence, ecological design, and cultural heritage conservation.

7.2. Practical Implications for Urban Planning and Design

This study provides practical implications for urban planners, architects, and designers seeking to integrate cultural heritage and ecological resilience in regeneration projects. The proposed LoRA+BDP framework provides a structured workflow that allows rapid generation of design alternatives prior to physical implementation, supporting visualization of options that preserve historic identity while introducing biophilic attributes such as vegetation, light, and water features.

First, AI-generated images can serve as decision-support tools in feasibility studies and early-stage design reviews, allowing planners to assess spatial coherence, environmental compatibility, and contextual continuity prior to detailed design.

Second, these visualizations facilitate participatory communication, helping citizens and non-experts intuitively understand complex spatial ideas during workshops and consultations, thereby improving transparency and inclusiveness in the decision-making process.

Finally, municipal authorities can employ the framework to support heritage-sensitive policies, using visual evidence to evaluate ecological and cultural impacts and prioritize sustainable interventions. Through these applications, generative AI can evolve from a visualization tool into a platform for collaborative and evidence-based urban regeneration.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study was exploratory in nature, with several limitations. First, there were constraints in both the dataset and the evaluation scope. LoRA fine-tuning was conducted using a limited dataset composed of Daegu’s alleys image, and expert evaluation was based on a relatively small sample. These limitations inevitably reduced the diversity of visual patterns and professional perspectives represented in the results, which may have influenced the generalizability of the findings. Accordingly, the study should be regarded as an exploratory experiment rather than a fully generalizable application. Nevertheless, its primary contribution lies in demonstrating how generative AI can be structured to integrate place identity and biophilic design within historic-alley contexts, thereby providing a methodological foundation for larger-scale research. Future work should expand to multi-city datasets and involve broader, more diverse groups of experts to capture cross-context variability.

Second, the broader application of AI-based approaches to other heritage contexts presents additional challenges. Architectural heritage varies significantly across regions in spatial typology, materiality, symbolism, and cultural meaning. Consequently, a model fine-tuned on a specific urban or cultural dataset—such as Daegu’s historic alleys—may not accurately represent sites shaped by different historical, climatic, or aesthetic conditions. Such contextual dependency could lead to representational bias in generative outputs, particularly in color, ornamentation, or symbolic interpretation. To ensure contextual validity, future research should incorporate region-specific datasets, collaborative validation with local experts, and comparative experiments across multiple heritage environments. These efforts would strengthen both the adaptability and reliability of AI-driven heritage-design methodologies.

Third, this study primarily focused on visual fidelity and typological cues, while cognitive and emotional dimensions of place identity were interpreted mainly through visual representation. As experts noted, affective resonance and symbolic association remain domains that are difficult for AI to replicate. Future studies should employ multi-modal approaches—such as participant narratives, community-based feedback, and physiological indicators—to complement and capture these intangible layers.

Fourth, although the structured BDP framework was effective in embedding ecological attributes, the simulations were static and scenario-based. The absence of temporal or interactive variation constrained the analysis of how users might experience environmental changes over time. Future research should therefore integrate parametric variations—such as seasonal transitions, diurnal lighting differences, and gradual transformations of vegetation and water features—to enhance both robustness and design-decision support.

Finally, the potential risks and ethical issues associated with generative AI must remain a focus of continued attention. Dataset bias, intellectual property concerns over generated images, and the possibility of cultural misrepresentation highlight the need for interpretive safeguards. Establishing transparent protocols for data sourcing, prompt design, and stakeholder participation will be essential to the responsible integration of AI into heritage-sensitive design contexts.

Although the study was methodologically confined to image-based simulations rather than physical implementations, it nonetheless yields valuable insights into the digital transformation of urban design processes, particularly in the pre-assessment of design outcomes and the anticipation of community responses. The directions proposed herein can further advance both the methodological maturity of generative AI and its practical applicability to urban regeneration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.-J.L. and S.-J.P.; Methodology, E.-J.L. and S.-J.P.; Validation, E.-J.L.; Investigation, E.-J.L.; Data Curation, E.-J.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, E.-J.L.; Writing—review and editing, S.-J.P.; Visualization, E.-J.L.; Supervision, S.-J.P.; Project Administration, S.-J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (Grant No. RS-2023-00275564) and the Korean Government (MSIT) (Grant No. RS-2021-NR058648).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

LPIPS and FID results for each alley type and effect size.

Table A1.

LPIPS and FID results for each alley type and effect size.

| Alley Type | Condition | LPIPS | FID | Cohen’s d (LPIPS) | Cohen’s d (FID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Prompt-only | 0.55 ± 0.15 | 154.17 ± 8.5 | 1.3 | 3.1 |

| Prompt+LoRA | 0.36 ± 0.14 | 128.12 ± 7.4 | |||

| Stairs | Prompt-only | 0.72 ± 0.16 | 214.72 ± 9.6 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| Prompt+LoRA | 0.36 ± 0.15 | 188.62 ± 8.9 | |||

| Edge | Prompt-only | 0.65 ± 0.05 | 255.01 ± 10.2 | 3.4 | 12.6 |

| Prompt+LoRA | 0.29 ± 0.14 | 114.02 ± 8.1 | |||

| Node | Prompt-only | 0.76 ± 0.16 | 245.84 ± 9.8 | 2.2 | 5.9 |

| Prompt+LoRA | 0.43 ± 0.14 | 186.89 ± 8.5 | |||

| Average | Prompt-only | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 217.94 ± 9.5 | 2.3 (avg.) | 6.2 (avg.) |

| Prompt+LoRA | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 154.91 ± 8.2 |

Notes: Quantitative comparison of image similarity metrics (LPIPS and FID) between prompt-only and prompt+LoRA conditions for each alley type. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Both metrics showed large effect sizes (Cohen’s d > 1 in all cases), indicating that LoRA fine-tuning significantly improved perceptual and statistical similarity to ground-truth images.

References

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past is a Foreign Country–Revisited; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H. A Study on Urban Regeneration and Creating Place Assets in Daegu Modern Alleyway. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Daegu Metropolitan City Jung-Gu: Historical and Cultural Street Tours. Available online: https://www.jung.daegu.kr/new/english/pages/tour/page.html?mc=5038 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Ujang, N.; Zakariya, K. The notion of place, place meaning and identity in urban regeneration. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernawati, J. Dimensions underlying place identity for sustainable urban development. MATTER Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 3, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.; Heerwagen, J.; Mador, P. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Beatley, T. Handbook of Biophilic City Planning & Design; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Y. Remedies from nature: Exploring the moderating mechanisms of natural landscape features on emotions and perceived restoration in urban parks. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1502240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, W.D.; Ryan, C.O.; Clancy, J.O. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health & Well-Being in the Built Environment; Terrapin Bright Green, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict, M.A.; McMahon, E.T. Green Infrastructure: Linking Landscapes and Communities; Island press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.J.; Park, S.J. A Structured Prompt Framework for AI-Generated Biophilic Architectural Spaces. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Ruiz, I. Artificial intelligence may affect diversity: Architecture and cultural context reflected through ChatGPT, Midjourney, and Google Maps. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.M.; Chen, J.; Kang, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Duarte, F.; Ratti, C. Place identity: A generative AI’s perspective. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raagmaa, G. Regional identity in regional development and Planning1. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Region and place: Regional identity in question. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 27, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groote, P.; Haartsen, T. The Communication of Heritage: Creating Place Identities. The Routledge Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, F.; Gou, Z.; Lau, S.S.-Y.; Lau, S.-K.; Chung, K.-H.; Zhang, J. From biophilic design to biophilic urbanism: Stakeholders’ perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Feng, Y.; Wang, R.; Jung, J. Enhancing the digital inheritance and development of Chinese intangible cultural heritage paper-cutting through stable diffusion LoRA models. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batifol, S.; Blattmann, A.; Boesel, F.; Consul, S.; Diagne, C.; Dockhorn, T.; English, J.; English, Z.; Esser, P.; Kulal, S. FLUX. 1 Kontext: Flow Matching for In-Context Image Generation and Editing in Latent Space. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.15742. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Obukhov, A.; Krasnyanskiy, M. Quality assessment method for GAN based on modified metrics inception score and Fréchet inception distance. In Proceedings of the Computational Methods in Systems and Software, Konstanz, Germany, 23–25 September 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-J.; Park, S.-J. Biophilic Experience-Based Residential Hybrid Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, A.; Desha, C.; Hargroves, K.; Newman, P. Informing healthy building design with biophilic urbanism design principles: A review and synthesis of current knowledge and research. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Healthy Buildings, Brisbane, Australia, 8–12 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.J.; Park, S.J. Toward the Biophilic Residential Regeneration for the Green New Deal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Beatley, T.; Boyer, H. Resilient Cities: Responding to Peak Oil and Climate Change; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.O.; Browning, W.D.; Clancy, J.O.; Andrews, S.L.; Kallianpurkar, N.B. Biophilic design patterns: Emerging nature-based parameters for health and well-being in the built environment. ArchNet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2014, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G.; Newman, P. Green infrastructure and biophilic urbanism as tools for integrating resource efficient and ecological cities. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Africa, J.; Heerwagen, J.; Loftness, V.; Ryan Balagtas, C. Biophilic design and climate change: Performance parameters for health. Front. Built Environ. 2019, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennessen, C.M.; Cimprich, B. Views to nature: Effects on attention. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Chang, C.-Y.; Sullivan, W.C. A dose of nature: Tree cover, stress reduction, and gender differences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 132, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H.; Saeidi-Rizi, F.; McAnirlin, O.; Yoon, H.; Pei, Y. The role of methodological choices in the effects of experimental exposure to simulated natural landscapes on human health and cognitive performance: A systematic review. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 687–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Smith, A.; Humphryes, K.; Pahl, S.; Snelling, D.; Depledge, M. Blue space: The importance of water for preference, affect, and restorativeness ratings of natural and built scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y.; Van den Berg, A. Is love for green in our genes? A critical analysis of evolutionary assumptions in restorative environments research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).