Abstract

The objective of this study is to examine the process of land-use change through the lens of the preferences of local actors in the Kırcami Agrihood. Our main focus is to investigate whether the decision-making mechanisms used in the Kırcami development plan (i) are carried out in accordance with deliberative democracy and (ii) whether they are true, systematic, and typical tools of deliberative democracy. To do so, in-depth interviews were conducted with local actors, namely residents, investors, and local government, and their preferences and views regarding urban agriculture and the decision-making process were examined through discourses. Our first finding is that very few tools of deliberative democracy are used in the making of the Kırcami development plan, and they are not idealised tools. Our second finding is that less than half of residents and investors participate in these flawed democratic decision-making processes; thus, the transformative power of deliberation does not function in the Kırcami case. Finally, deliberative democratic tools are not incorporated into Turkish legislation at both local and national levels. We conclude that these three issues should be addressed, and genuine tools of deliberative democracy should be used to make the Kırcami development plan more sustainable and legitimate.

1. Introduction

Discussions on the future of cities in the late (post)modern world, identified by globalisation, population growth, and climate change, are generally conducted through the lens of sustainability. This is because the climate crisis facing the world requires the sustainability of cities, which are home to more than half of the world’s population. As a result, the concept of urban sustainability refers to goals such as making cities and human settlements sustainable and resilient and creating self-sustaining cities by ensuring food security [1] (p. 122). The capacity of cities to feed themselves is directly related to their proximity to rural areas, the presence of urban agricultural land, and the level of agricultural production. Recently, with rapid population growth, the rate of urbanisation is also increasing, creating pressure and uncertainty for the future of the rural core and the urban periphery. Urban agriculture, with its positive social, economic, and environmental effects on urban areas, can be seen as one of the outstanding solutions for a sustainable future in such cities with close links to rural activities.

In this sense, some issues have been at the forefront in terms of addressing urban sustainability in the late modern age. The issues of sustainable development of cities and environmental boundaries in urban sprawl occupy a pivotal place in debates over the future of cities [2,3]. The 11th aim of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) designed by the United Nations in 2015 is “sustainable cities and communities”. Under the framework of this goal, urban targets based on various indicators have been set on issues such as climate crisis, food security, and safe neighbourhoods, which are regarded as one of the most important risks in the future [4].

The rapid and uncontrolled urbanisation process leads to a gradual decline in rural areas and an increase in major problems that cities need to face, i.e., food insecurity, ecological deterioration, poverty, and underemployment. As the urban area spreads promptly due to rapid urbanisation, rural areas at the periphery transform and this leads to spatial disconnections between urban areas and their periphery [5] (p. 274). These spatial disconnectivities lead to not only physical changes but also economic and social relations. The starting point of socio-spatial and socio-economic change between the urban periphery and the centre is the change in the form of agricultural production [6].

Urban agriculture therefore emerges as a sustainable solution and an alternative production model to industrial agriculture in terms of the goal of sustainable urbanisation. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), for instance, defines it as a form of production and economy that uses local resources to meet the needs of the growing urban population [7]. It is a system that integrates the economic, ecological, and social structures of the city [8] (p. 190) [9]. Its current and potential advantages, as outlined by Kubi Ackerman and others [8] (p. 192), Jerry Kaufman and Martin Bailkey [10], and Mark Redwood [11] (p. 5), are as follows: It contributes to local development together with the agricultural production process by reducing poverty by creating new employment opportunities, it increases food security by ensuring that everyone in the city has access to local and clean agricultural products, it maintains the biological diversity of the city, it facilitates the reuse of municipal solid waste and organic waste and water sanitisation processes, and it cools down the cities in the face of increasing temperatures due to global warming.

On the other hand, various actors living in highly populated cities might have some divergent preferences on the future development tendencies of urban agricultural lands remaining in the city. Democracy, especially at the local level, thus plays a key role in the political dimension regarding decision-making about the future of urban agriculture, and conflicting preferences of different actors in society are decisive in this formation of change. In democratic societies, decisions to transform urban agricultural lands into a planned region for urban purposes are taken collectively, applying democratic decision-making mechanisms. Divergent decision-making mechanisms can be used by different societies. However, as will be briefly overviewed in this study later, especially at the local level, since the 1950s, thanks to growing pluralism, diversity, and differences, especially in late (post)modern Western liberal democratic societies, both a growing dissatisfaction with representative forms of democracy and an increasing demand for direct citizen involvement in decision-making mechanisms via tools of direct and/or deliberative democracy have been observed (for a succinct review, see [12]).

This has resulted in the widespread idea that all local decisions affecting every individual and group in a society ought to be taken in an inclusive and consensual way through deliberative democratic decision-making mechanisms that will address the preferences of those directly affected by the decision. In other words, it has been claimed that representative democracy is in a crisis of representation, participation, and legitimacy, and therefore, this crisis should be overcome. Deliberative democracy is therefore offered as a solution to this crisis since it regards the source of democratic legitimacy in deliberation itself, emphasises the transformative power of deliberation and communication when conflicting preferences of the actors affected by decisions are taken into account, and is based on an egalitarian and inclusive decision-making process centred on discussion/deliberation. Some of the leading scholars have developed theoretical and normative tenets and assumptions of deliberative democracy and its practical aspects and tools. For instance, John S. Dryzek’s discursive democracy [13] combines participatory democracy, communicative rationality, and critical theory and provides discursive designs to operate deliberative democracy in practice. James S. Fishkin [14] aims to reconcile democracy and deliberation by proposing deliberative opinion polls. While Jürgen Habermas [15] contributes to the theoretical and normative dimension of deliberative democracy by emphasising communicative processes and transformation of the public sphere, Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson [16] propose a practical model of deliberative democracy, focusing especially on moral disagreement, reciprocity, publicity, and accountability.

Accordingly, this study is motivated by recent debates in the scholarly literature and practice on the relationship between urban agriculture, sustainability, and legitimacy of development plans and aims to evaluate the democratic legitimacy of the (non-)sustainable transformation of urban agricultural land into a planned region for urban purposes. Antalya’s Kırcami Region of Turkey is selected as a case study. It is an illustrative example of the urban agricultural area associated with a more than 40-year-long conflictual political and legal process of possible change in urban land use. This paper aims to reveal the preferences of three different actors, namely the inhabitants, investors, and local government, on the future of urban agriculture in the region. In this study, the three actors were interviewed not only about the legitimacy of the decision-making process itself but also asked other questions in order to both reveal the main factors shaping their preferences, interests, and decisions in the (if any) deliberation process and to determine potential factors that may lead them to negotiate and make not only a legitimate but a sustainable plan.

It should be stated in advance that, to the best of our knowledge, this study and the examined case are unique. It is the first scientific study to identify the deficiencies in the democratic decision-making process in a disputed urban agricultural area that has not been solved in terms of planning for a long time and to identify and propose democratic tools to overcome them in a local context. There are, of course, studies in the academic literature that focus on the intersection of urban sustainability, urban agriculture, and urban planning due to the problems and challenges arising as a result of the climate crisis and various social and economic needs (see [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]). There are also some academic works focusing specifically on practical policymaking examples benefiting from the use of deliberative democratic tools in urban planning. For instance, according to the OECD [24] (p. 70), even though they are used at all levels of government, representative deliberative processes have prominently been used locally. More strikingly, urban planning ranks first among the common policy issues addressed through representative deliberation processes in public decision-making processes [24] (p. 75). As for the academic works, two remarkable examples examined institutionalised practices, which are defined and examined clearly in the OECD report. For instance, the use of deliberative democracy by local governments in the Western Australian capital city of Perth (2001–2005) and the regional city of Greater Geraldton (2011–2015) to address complex and wicked sustainability issues provides an alternative to the common understanding of urban change. Through these two examples, Hartz-Karp and Marinova combine complexity and wickedness with integrative thinking and deliberation in order to examine how to deliver better urban solutions in the face of wicked sustainability problems [25,26]. Another example is the deliberation process carried out through citizen assemblies and mini-publics in the Grandview-Woodland neighbourhood in Vancouver, Canada. This is an example of a form of small publicity created against the complexity of the urban planning process and as a result of objections to the 30-year plan of the neighbourhood. At the end of this process, the 30-year plan for the neighbourhood was made through deliberative democracy practices [27].

These three studies, in particular, are important works that have inspired our study. However, these studies and the policy examples they examine do not specifically address the relationship between urban agriculture and urban sustainability as a complex and wicked problem. Moreover, these studies and the policy examples they examine are conducted in established liberal democracies, in states where decisions made using deliberative tools are binding on decision-makers, and where all actors internalise the value and importance of democratic participation.

In this respect, this study, and therefore, the Kırcami example, has global novelty in three respects. First, in terms of deliberative democracy literature, this study proposes that in construction processes related to urban sustainability and urban agriculture, the future expectations and political preferences of all different actors should be collectively included and reconciled in the decision-making process. What makes this study distinctive is that plans made as a result of democratic decision-making processes that do not take into account multi-actorness and bottom-up scaling are top-down and rent-oriented plans where the transformative power of deliberation does not work. In this sense, this study highlights that deliberative democratic tools not only enhance the legitimacy of a development plan for urban agricultural lands but also aim to guarantee more sustainable development plans thanks to their transformative power over conflicting preferences of divergent actors in society.

Second, even though the use of deliberative democracy for better development plans is worked in different cases, this study examines a much more sensitive issue: urban agricultural lands. Kırcami, as an urban agricultural land, is a unique case for some reasons. The area has experienced an increase in both the number of sub-cloth greenhouse areas and agricultural production, even though the area has been planned for urban purposes. While urban agricultural areas are generally located in the city quarter, Kırcami is an unconstructed Agrihood area in the city’s centre, whose development plan problem has not been solved for 40 years. There is no other example similar to Kırcami either in Turkey or elsewhere in the world. Politically, especially compared to Australia and Canada, Turkey is an entrepreneurial state [28,29] that prioritises investors and economic concerns over other actors and issues and does not incorporate deliberative tools in its legislative system; therefore, none of the actors, especially the public, have resources and opportunities to internalise the values of democratic participation. Kırcami is therefore an appropriate case for assessing the legitimacy and nature of the sustainability of a development plan for urban agriculture, referring to the deliberative democratic decision-making mechanisms at the local level. This is mainly because the planning process in the region is totally based on representative democracy, supplemented by the tools of deliberative democracy, which are very few and rarely used. Finally, this study is original in terms of research design. It not only investigates the expectations and political preferences of the residences living/working in the region but also investors and political actors embracing an approach focusing on multi-actorness and bottom-up scaling.

In this sense, by examining individual and collective preferences in the Kırcami area, we try to answer the following research question: whether and to what extent conflicting preferences of different actors are collectively reconciled through deliberative democratic tools to make a sustainable development plan for the region. In particular, it is aimed at answering whether mechanisms used in the decision-making process regarding the Kırcami development plan are performed in line with the basic principles and assumptions of deliberative democracy. In addition, it is also expected to reveal whether they are true, systematic, and typical tools of deliberative democracy/public debate. To do so, we define the discourses of participants in the Kırcami Agrihood from in-depth interviews with local actors, namely residents, investors, and the local government.

To that end, this paper consists of three parts. The first part starts with a brief examination of the changes in agricultural production with rapid urbanisation and theoretical discussions on urban agriculture and deliberative democracy. The second part discusses the case study area, Kırcami-Antalya, based on its locational characteristics, changes in planning decisions, and decisions of annulment by the courts regarding the discussions of opening the area for urban construction purposes that lasted for more than 40 years. In the third part, we present data obtained from in-depth interviews conducted with 30 people living in the Kırcami Region, including 10 people who are investing in the region and two experts from the local government (one from the Muratpaşa Municipality and the other from the Antalya Metropolitan Municipality). This part proceeds with the findings, which are analysed through discourses as a qualitative research design approach. Lastly, the conclusions and future proposals are given.

1.1. The Role of Deliberative Democracy in Making Sustainable and Legitimate Development Plans

The most important goal in the need to continue urban agricultural production as a policy goal and an alternative form of production should be to produce a solution against the climate crisis, global hunger, poverty, housing problems, and rapid urban growth and to create local resilience against these problems. Divergent and conflicting preferences regarding the future of urban agriculture ought to ensure both the reconstruction of space and the functioning of the economic, social, and ecological justice system in the use of resources in order to solve the aforementioned problems, which have a serious risk of increasing in the very near future [30] (p. 150).

In order to make cities more sustainable, divergent and conflicting preferences of actors (such as individuals, groups of people, international organisations, states, non-governmental organisations, local governments, and all related actors) should be considered to make more sustainable development plans. By imagining, expecting, and implementing lands for urban agriculture, it is more possible to create counterstrategies to escape from the possible risks and negative (social and environmental) risks of urban development. At this crucial point, the method of making political decisions regarding the future of urban agriculture is at stake and makes democratic decision-making mechanisms vital tools for reconciling alternative solutions.

1.2. Deliberative Democracy as the (Most) Legitimate Way to Collectively Reconcile Decision Makers’ Preferences on Urban Agriculture

Democracy plays a pivotal role in the political dimension regarding the future of urban agriculture. All local decisions that directly and primarily affect the lives of individuals and groups living in the local community, for instance, urban and development plans, should be taken directly by the actors affected by the decision, using the tools of deliberative democracy (see [24] (p. 73)). According to the OECD [24] (p. 70), even though they are used at all levels of government, representative deliberative processes have prominently been used locally. More strikingly, urban planning ranks first among the common policy issues addressed through representative deliberation processes in public decision-making processes [24] (p. 75).

This demand for more direct democracy is essentially related to the growing dissatisfaction with representative democracy. It is argued that representative democracy has experienced a crisis of representation, participation, and legitimacy, especially after the 1950s. It can be argued that this crisis is more evident when it comes to local policies, particularly urban planning, due to the smaller population and narrower geography (see [31]; for reasons for this crisis, see [32]).

The most obvious reaction to this crisis has been the ontological, theoretical, normative, and empirical changes in democratic decision-making processes. İlhan Tekeli [33] (p. 49–89), for instance, argues that the crisis of representative democracy has led to significant changes in the practice of democracy. These changes have been underpinned by other concomitant changes in ontological assumptions and consequent changes in the nature of decision-making processes and decisions. In this framework, the option of deliberative democracy is one of the leading alternative solution proposals to overcome this crisis by increasing direct, active citizen participation, especially at the local level.

Deliberative democracy attributes the legitimacy of the decisions taken at the end of democratic decision-making processes to the use of deliberation as a tool in these processes. According to this understanding of democracy, it is insufficient to determine citizen preferences through voting and elections by merely “counting heads” [34] (p. 121). The same applies to all kinds of local decisions. Since “preferences, interests, and values are shaped and constrained by the political, social, and economic context in which individuals find themselves” and since “preferences are not exogenous to institutional settings” [35] (p. 52), democratic decision-making is more than an activity focusing on the aggregation of preferences that are taken as given or fixed through elections or political parties [36]. Therefore, in order to overcome the crisis of representative democracy, deliberative democracy brings a new insight by arguing that “talk-centric democratic theory” should replace “voting-centric democratic theory” since the former emphasises “the communicative processes of opinion and will-formation that precede voting” [37] (p. 308). This leads to “a more wide-open and inclusive model of democratic discourse” [38] (p. 4). As Jane Mansbridge et al. [39] (p. 65) note, this process should be “open to all those affected by the decision” and “participants should have equal opportunity to influence the process, have equal resources, and be protected by basic rights”.

In addition to its aforementioned general principles and assumptions, deliberative democracy, in particular, emphasises the transformative power of deliberation (for a succinct review, see [36]). As Iris Young [40] (p. 26) notes, through deliberative public debate, “people often gain new information, learn of different experiences of their collective problems, or find that their own initial opinions are founded on prejudice or ignorance, or that they have misunderstood the relation of their own interests to others”. We can also draw the following conclusion: Individuals’ demands for all kinds of decisions, especially local ones, and the interests they declare based on these demands can be changed and revised through deliberation by being exposed to alternative preferences, interests, and opinions. For instance, when the relationship between development plans and rent is taken into account at the local political level, people can recognise more sustainable non-rent alternatives, such as urban agriculture, and be convinced to adopt these alternatives. In other words, deliberation can have a transformative power that urges actors to prefer sustainability to rent.

With reference to the essential tenets and assumptions of deliberative democracy that we have tried to provide briefly above, the next section aims to identify what makes a decision-making mechanism a true and typical instrument of deliberative democracy/public political debate when considering the processes of local development plans.

1.3. The Qualities of a True Instrument of Deliberative Democracy

The qualities that make participatory decision-making practice a true deliberative democracy tool can be briefly explained as follows. They should be open and transparent, where all actors affected by a decision have equal opportunities and resources to freely participate and cooperate. True deliberative democracy instruments are not platforms where policies and practices determined by representatives, elites, experts, or other powerful actors are presented to citizens and they are informed before they are implemented, but rather, they are places where decisions on all policies and practices are negotiated. Even if they do not constitute an agora as a practice of direct democracy per se, if the necessary legal and political mechanisms are in place, they are effective instruments where the decisions taken bind public authorities directly and legally/politically compulsorily. Or at least, if they are used as an instrument of deliberative democracy, which is used effectively in representative democracies, there should be various regulations for such a binding character.

Thus, true deliberative democracy tools are not just a means to substitute/complement/strengthen representative democracy but rather practices in which the decisions are taken as a result of a systematic and inclusive real public political debate whose results are at least binding on the decision-making assemblies in various ways. As Jonathan Kuyper and Fabio Wolkenstein [41] (p. 661) point out, not all mini-publics involve systematic deliberation, as mentioned above. In some cases, some deliberative democracy tools may even be used by political actors “for show” in order to give the impression that the decision was taken with the participation of all actors who will be affected by it. For example, Anthony Costello [42] (pp. 1–2, 11, 13) describes the Citizens’ Dialogues on the future of Europe, which took place in Ireland in 2018, as a kind of deliberative democracy tool and as a tokenistic public relations practice in which the lack of elite political will for democratic deliberation and the design structures and quality were weak and the proposals could not influence the decisions rather than a real dialogue and deliberative democracy practice. Based on these dialogues, it can be said that, in particular, the transformation of the meetings into a question-answer routine rather than a discussion environment with a traditional and rigid format [43] (p. 325) is one of the most important problems for them to become an authentic dialogue [44] (p. 20). A true deliberative democratic practice should also be a democratic instrument in which decisions are taken after deliberation and debate and in which these decisions are binding to a certain extent but not as a substitute for representative democracy at a very basic level.

Accordingly, with reference to the afore-sketched conceptual framework and considering the scope of this study, we investigate whether the decision-making process regarding the Kırcami development plan (i) is carried out in accordance with the basic principles and assumptions of deliberative democracy and (ii) whether real and typical tools of deliberative democracy/public debate are used. Before dwelling on this investigation, in the following part, we try to elaborate on the emerging issues of urban agriculture from the perspective of preferences by designing a case study research of an urban transformation area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Area: Antalya Kırcami Agrihood

Antalya is one of the agricultural production centres of Turkey that has developed rapidly since 1980, and its population has accordingly increased considerably due to immigration within and from outside Turkey. This has caused many agricultural lands to be opened to construction. The root cause of this growing immigration is the rapid development of the tourism sector in the city [45] (p. 87). With the rapid development of mass tourism, a tourism-city region that integrates both spatially and economically between the centre and districts of the city has been formed [46] (p. 467), and agricultural lands in coastal settlements have been opened to construction in order to ensure this integrity.

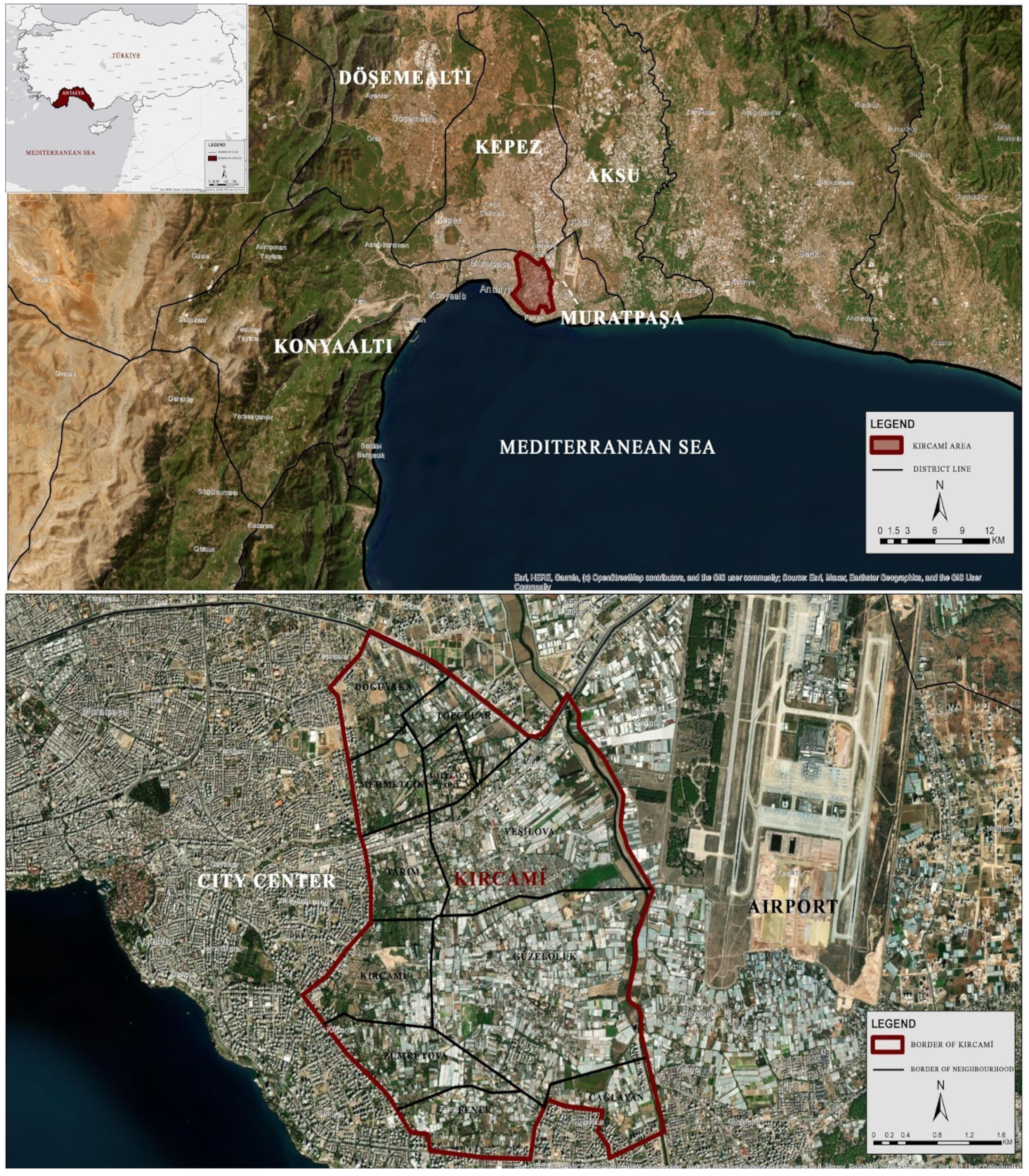

The latitude of the Kırcami Agrihood is 36.873196°, and the longitude is 30.742037°. (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). It covers approximately 1477 hectares between the city centre and Düden Stream/Airport. The Kırcami area comprises all of the Doğuyaka, Topçular, Mehmetçik, Güzeloluk, Zümrütova, Yeşilova, Kırcami, and Alan neighbourhoods and some parts of the Fener and Çağlayan neighbourhoods.

Figure 1.

Location of the Kırcami Region in the Antalya province (created by the authors using Google Earth 2024 data and data from [47]).

Figure 2.

Neighbourhoods in the Kırcami Region (created by the authors using Google Earth 2024 data).

This area includes one of the most important agricultural settlements in Antalya, and 7% of the greenhouse areas in Antalya are located here [48] (p. vii). Located in Muratpaşa, the central district of Antalya with the highest population, the Kırcami area still has a rural settlement character, unlike its adjacent neighbourhoods, which have dense housing developments and other urban land uses. Düden Stream is the main source of irrigation for agriculture in the region. The economy of the area is mostly based on greenhouse agricultural production, and mostly green vegetables are produced in the region.

Urban agriculture typologies observed in the Kırcami Agrihood consist of practices of landscaping, hobby gardens, urban and peri-urban gardens, farms, and community gardens. These practices are carried out for purposes of individual/collective consumption, education, and sales. The Kırcami area is at risk of transformation by being covered by dense urban functions (especially dense housing areas) taking place in the centre of Antalya city and should be planned in a more sustainable way to avoid risks to the environment. However, the planning process for the area is problematic and still has not been solved, as discussed below.

When we examined the Kırcami area in Antalya development plans, 1980 seemed to be a turning point in terms of identifying what kind of land use would be planned for Kırcami, whether it would be opened for construction or where it would keep its urban agriculture character. As [48] (pp. 66–94) aptly determined, by examining the planning chronology of Kırcami in a detailed way by dividing the process into 35 different sections, the Kırcami Region was first characterised as a “settlement area with protected agricultural character” in the 1/5000 scaled Master Development Plan of Antalya prepared by Zühtü Can and approved by the Ministry of Development and Housing on 19 February 1980. The Kırcami urban planning area was then incorporated by the UTTA plan into the “urban planning area” in 1996. As a result of this decision, both the Muratpaşa Municipality and the Antalya Metropolitan Municipality started to adopt the approach that the area should be planned for urban purposes. Since 1980, the character of the area has been defined differently in almost every plan. At first, the area was defined as agricultural, then as a residential area with agricultural character, and finally as a settlement area. The region was eventually planned as a business and residential area in the 1/5000 scaled Kırcami Master Development Plan adopted by the Parliament of the Antalya Metropolitan Municipality on 13 January 2014 (the protection of agricultural lands or agricultural production is not mentioned in this plan) and as an urban settlement area in the 1/100,000 scaled Antalya-Burdur-Isparta Plan approved by the Ministry of Environment and Urbanisation on 15 April 2014. Even though the Administrative Courts cancelled the relevant plans in 2016 and 2019, the development problem of Kırcami was considerably solved with the Environmental Regulation Plan, the 1/100,000 scaled development plan, in 2022.

However, nearly all the approved plans have been made to embrace a top-down approach, reflecting the populist political preferences of both the public and politicians or other powerful actors in the process, and have also been the subject of litigation several times due to a lack of consensus among the actors and other legal reasons. In this sense, the legal dispute process regarding the nature of the Kırcami Region, whether it will be opened to construction or if it will be opened and how it will be carried out, refers to a complex process, which has also been going on for more than 40 years. Considering the scope of this study, the latest status of this long legal process can be summarised as follows.

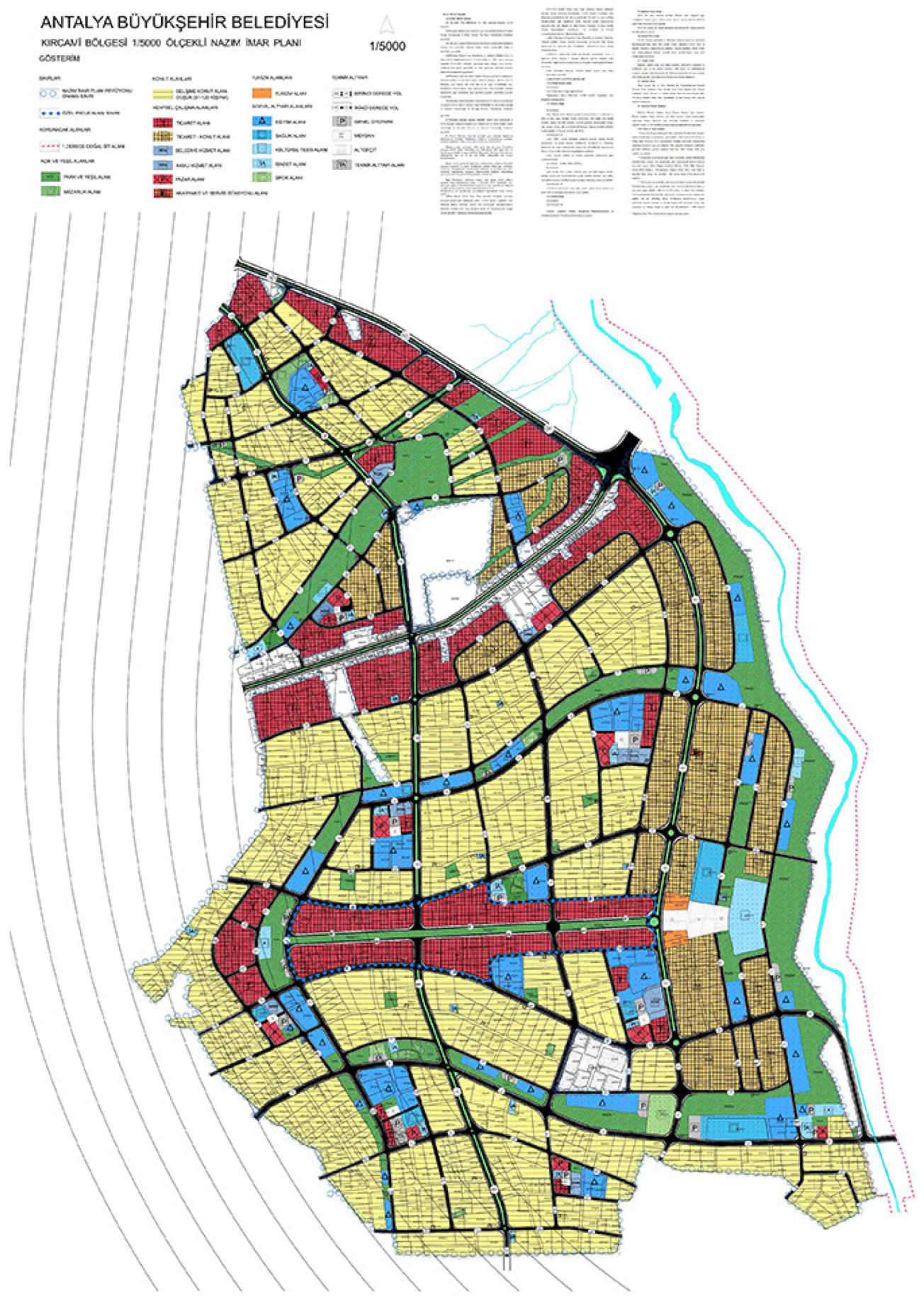

A lawsuit was filed for the cancellation and suspension of execution of the 1/25,000 and 1/5000 scaled Master Plan revisions and amendments [47] (See Figure 3). The lawsuit, which had been pending at the Court of Appeal for a long time, was won in favour of the Antalya Metropolitan Municipality in 2023, and deeds were distributed, developed roads started to be opened, and construction permits were issued. However, after the owners of the parcels filed a lawsuit again, the Antalya 2nd Administrative Court issued a suspension of execution and cancellation decision on 12 April 2023 [49]. The court ruled that there was no compliance with the law, distribution principles, and principles and public interest in the parcellation process subject to the lawsuit [50]. The Mayor of Muratpaşa Municipality notes that the prominent grounds for the objections to the Kırcami Region development plan are as follows: The development plan is not in accordance with the 1/100,000 scaled Environmental Master Plan, the region is not suitable for construction due to its agricultural characteristics, and the Ministry of Interior’s public interest decision [51]. In addition, other technical objections that are frequently voiced are that it is erroneous to make a single parcelisation plan and that the Muratpaşa Municipality has made parcelisation based on the previously invalidated development parcels without returning to the root title deed (see [49]). On the contrary, according to the Muratpaşa Municipality, the 1/5000 scaled Master Development Plan has been prepared in a holistic manner, and this is crucial for ensuring fairness and balanced distribution in the arrangement of the development readjustment share (DRS). According to the municipality, the parcel size requirement is important for the healthy development of Kırcami and this necessitates approaching Kırcami as a whole. In this framework, the municipality asserts that it is not necessary to return to cadastral parcels since there is no error in the DRS calculation of the parcellation plan in Kırcami [52].

Figure 3.

1/5000 scaled implementation plan under revision demanded at the court (Source: [53]). The areas represented by the colours are as follows: red: trade functions; yellow: low-dense housing function; brown: high-dense housing function; green: urban green, parks, etc.; blue: education and health functions, schools, hospitals, etc.; orange: hotel functions; white: military area.

The Antalya Metropolitan Municipality appealed to the Konya Regional Administrative Court against the decision, which was highly resonant in the city and triggered many legal, technical, bureaucratic, and political debates [49]. The Konya 2nd Regional Administrative Court ruled on 4 May 2023 that there was no compliance with the procedural provisions in the suspension of execution decision on the grounds that the expert report was not duly communicated to the parties, that the decision should be cancelled, and that the request for the suspension of execution should be rejected [54]. Even though the court’s decision will re-run the process in favour of the Muratpaşa Municipality and the Antalya Metropolitan Municipality, the decision to reject the request for a suspension of execution due to a procedural deficiency has not eliminated the uncertainties and disputes regarding the development of Kırcami.

It is obvious that recent legal disputes, in particular, focus on the discussion of how the parcelling will be done with rent concerns rather than the political question of how the future of agricultural land and production potentials in the Kırcami Region will be shaped and sustained under the pressure of urbanisation. This is mainly because of the absence or deficiency of using deliberative democratic tools in deciding the future of urban agriculture in the Kırcami Region and therefore, the inefficiency of creating appropriate deliberation platforms to initiate the transformative power of deliberation based on the preferences of parties.

2.2. Design of the Research and Methodology

In designing the research, we first defined our unit of analysis. These are residents, investors, and planners in the case study area. While defining our sample, as can be seen in Table 1, we used secondary data provided by the local municipality showing the size of hectares owned by the residents and investors. According to the data, we defined three big-, small-, and medium-sized landowners. Then, the stratified random sampling method was applied in the selection of landowners according to their parcel size, which is distributed as big (4 investors), medium (3 investors), and small (3 investors) parcels. In total, 5 parcel owners from 27 parcels of big size over 20,000 m2, 3 parcel owners from 206 parcels of medium size between 10,000–20,000 m2, and 22 parcel owners from 166 parcels of small size under 10,000 m2 were interviewed. Table 1 also contains some demographic information and the neighbourhood that participants and residents live in.

Table 1.

In-depth interviews conducted with the residents and investors according to their land size, location, and socio-economic status (created by the authors based on data provided by the local authority).

The in-depth interviews include some of the following types of questions that can only be measured using qualitative research techniques: “Why am I doing urban agriculture now, and if the area is opened to construction, will I have the reason and motivation to do it in the future? Am I satisfied with urban agriculture?”.

We conducted in-depth interviews with 20 participants living/working in the Kırcami Region, 10 investor landowners who do not live in the region, and two experts from local authorities. Interviews were conducted with 20 residents (who are living/working in the area) from all neighbourhoods in the Kırcami Region by using multi-level cluster sampling. The field study was completed for residents when the answers to the questions started to repeat (saturation point). In addition, 2 experts from the local authorities (one urban planner from the Muratpaşa Municipality where Kırcami is located and one urban planner from the Antalya Metropolitan Municipality) were selected to understand whether the planning process of the Kırcami area changes from a local implementing scale authority to a city scale planning authority. Separate multiple-choice and open-ended questions were designed for the three different aforementioned groups: those who live and/or work in the area, own land as investors, and are local experts. Interviews with all three groups of participants were conducted in different settings and conditions for reasons that could not always be controlled. Interviews with residents were conducted face-to-face, alone or with family members present in the participants’ homes or gardens; interviews with investors were conducted face-to-face, alone, or with family members present in the participants’ homes, workplaces, or gardens; and interviews with local experts were conducted face-to-face and alone in the participants’ workplaces. The answers to the questions were audio-recorded by the participants who gave permission, and the answers were analysed using discourses based on the following themes: factors affecting investment and locational choices of themselves and planners of the local authority, such as the current situation of the region, land use, reasons for locational choice, decision-making mechanisms, the status of the implementation plan, participation strategies of local government to the future preferences for the area, and whether settlement strategies are defined in participation or not. We interpreted the background of the discourses in the answers we received from the in-depth interviews with the participants from a critical/realist perspective. As a result of this analysis, we made inference grouping in the tables and results and matched these findings with discussion points.

3. Results

The findings indicate that all three actors have divergent and conflictual preferences for the future of urban agriculture in the Kırcami Agrihood for some similar or diverse reasons. A legitimate and sustainable development plan for deciding upon the nature and quality of urban agriculture in the region can only be performed by developing decision-making mechanisms and using appropriate tools to reconcile their divergent preferences and interests via an inclusive, systematic, and vibrant deliberation for all the reasons provided in this study regarding why institutionalising deliberative processes is valuable and reasonable.

Before discussing the results in a detailed way, it should be noted, as shown in Table 2, that almost all three groups of participants think that the Kırcami development plan is not carried out in a democratic way using deliberative democratic tools. As seen in Table 2, only 25% of residents, 50% of investors, and all local experts state that they participated in democratic decision-making processes. As will be discussed in detail below, the relatively low participation rates and the differences between the groups are due to a lack of information, lack of internalisation of the value and importance of democratic participation, power, and resource asymmetry between actors, etc. In Table 2, the most prominent attitude towards asymmetric power and resource position in influencing the decision-making process is that 75% of residents believe that investors influence and direct the decision-making process in order to realise their own interests.

Table 2.

Number of participants regarding whether the Kırcami development plan is carried out in a democratic way and/or using deliberative democratic tools (created by the authors).

3.1. Preferences and Participation of the Residents (Living/Working) for the Kırcami Area/Plan

We aim to determine the preferences of the residents for the future of urban agriculture in the Kırcami area and to obtain motivations and/or interests behind their political decisions regarding the development plan. Thus, we first aim to reveal why the participants are engaged in urban agriculture in the region. We found that 11 participants are compelled to engage in agriculture due to the fact that the lands were inherited from the family and this business was a family tradition, 5 participants engage in the agricultural sector because they have no other profession, and 4 participants do urban agriculture because they like to do it. Only one participant works as a tradesman in the region. The opinion of a participant (P3) about this is as follows:

“It’s an ancestral business. They say the land they stay on is planned for urban purposes, so we cannot sell it. We cultivate it instead of leaving it empty. I have no other professional knowledge.”

If the participants are satisfied with the agricultural sector, this might potentially affect their decisions regarding urban agriculture. Thus, when the participants were asked whether they are satisfied with the agricultural sector, more than half of the (12) participants stated that they are dissatisfied with the sector, while less than half of them were satisfied due to an increase in their income compared to the previous years. The statement of one participant (P17) regarding the reason for being dissatisfied with the agricultural sector reveals the main reason for dissatisfaction in the region:

“The agriculture sector is a difficult sector. Our yield is very low, input costs are very high. In the face of this, our earnings are low.”

While nine of the participants are engaged in farming, the other participants who are not engaged in farming are still in the agricultural sector in order to obtain additional income. All participants live in Kırcami, and all of them except two people also work in the region. While the amount of land/plot/greenhouse owned by the participants equalling less than 5000 m2 (in total, 13 participants) is involved in local and national-scale agricultural production, the ones owning more than 5000 m2 (7 of them) export agricultural products abroad.

However, when the participants were asked about the disadvantages of urban agriculture in the region, they mentioned the input costs in agricultural production as the source of the problems. In addition, “intermediaries”, which is another controversial issue in urban agricultural areas, were also mentioned among these problems. The views of the participants (P13, P10, P9) on the mentioned disadvantages are as follows:

“Most people here are small producers. The work of small producers is difficult everywhere. Our soil is no longer fertile. This is the most difficult part. That’s why I have to use fertiliser. The price of fertiliser and seeds has increased excessively. There is no need for such a thing in the village.” (P13)

“Huge apartment blocks on one side and greenhouses on the other. Our costs are too high. And we cannot go to the market. We depend on intermediaries. Therefore, the difference between the price sold in the market and the money we receive is very high. We get a quarter of the money you pay for parsley in the market.” (P10)

“The cost is too high. And the middlemen take most of the money. Our share is very small. We cannot go to the market because we cannot find labourers. Wages are high. I sometimes go to work for daily wages to make a living myself. It is very difficult to do agriculture here now.” (P9)

Residents were also interviewed, particularly about the advantages of urban agricultural production in the centre of the city, and the results surprisingly varied between them. Factors such as “proximity to the city centre and wholesale market, the presence of the Düden stream (proximity to the water), and proximity to the market” are seen as the main advantages. The interpretation of these advantages from the producers’ point of view can also facilitate seeing the potential of the city to feed itself [55]. It was also observed that they perform urban agriculture for commercial purposes. The views of the participants who stated that urban agriculture is advantageous are exemplified in the statement of P10:

“Our water is at the bottom. Duden is our lifeblood. We are also close to the wholesale market. If the trader does not buy the goods, we can sell them to the wholesale market.” (P10)

On the contrary, some residents stated that there are no advantages left. P13 stated the following:

“Actually, it doesn’t have much of an advantage. But let’s say water. We have water. We are close to the wholesale market; we are in the city. But the fertility of the soil is gone. We are struggling to produce inefficient soil. What we produce and what we earn are reversing each other. We cannot make savings. Most of the money we earn goes to fertiliser, medicine, and seed. Is this necessary?” (P13)

As can be understood from the findings obtained, the planning attempts of Kırcami play a crucial role in shaping the future preferences of those living or working in the region. When we asked about their expectations from the plan, as summarised in Table 3, we observed that the majority of participants prefer residential land use for their area. Surprisingly, we found that there is a contradiction between the type of land use determined in the area where the residents live in the current plan and land-use type expectations for the area they currently live in. A total of 35% of the residents (seven participants) prefer a residential area with a garden and high green function. Even though the majority wants a planned land use with at least a residential function, only a small minority prefers a commercial area instead of a residential function. These expectations regarding the future of urban agriculture were divergent. Conflicting preferences and short-term, rent and economic interest-oriented expectations, both between the current plan and expectations and in relation to sustainable urban agriculture, can be observed in the Table 3. This stems from the failure to collectively reconcile these preferences with the tools of deliberative democracy, which were also not used in the making of the current construction plan.

Table 3.

The current land use types in the area where the residents live in the current implementation plan and the type of land use they expect from the plan (created by the authors).

In short, the majority of replies from the development plan are “to stay in their own parcels, to solve the problem of fragmented parcels, to have housing, and to have commercial rights under housing”. For instance:

“There would be no objection if there was an implementation plan according to the old title deeds. But the places they moved us to and the fragmentation of the land caused many objections. If it is according to the old title deeds, no one would object. Then we would not lose our neighbourly relations. We would not lose the location of our house. In the current plan, it is the same as me moving to Istanbul or Ankara. I will be in a flat, and I will not know anyone. What is the point if we do not see our neighbours.” (P18)

“I want to stay in my place. If they are going to give me rights, they should give me my rights where I am. Don’t send me 3 kilometres away. I would like the greenery not to be destroyed, and even if they can, I would like the greenhouses to be organised and kept. So what if there are greenhouses in the city? Maybe I’m wrong, but if they do it in an organised way, we can continue our work. For example, I don’t want tall buildings anymore. We became afraid after the earthquake.” (P2)

“Everyone has only one expectation: to stay on their own land. They do not want their land to be fragmented. There is not a lot of fragmentation on my plot, but I would like to stay on a single parcel. I would like to have mixed use, which they call mixed use, residential and commercial.” (P13)

“There is a need for order; that’s true. But I am not sure if high-rise apartment blocks are needed. Let them build infrastructure, build 3–4 storey buildings, keep our green areas, and encourage young people to do agriculture. Young people leave here when they get married. Let them stay; let them cultivate. Everyone should be able to stay in the same place with their neighbours.” (P11)

These answers exemplify how the participants living in the region attach meaning to the space they live in, the way they use the space, and the relationship they establish with natural life. At the same time, they attach an identity to the area since they emphasise that the area is a natural habitat and that they want the continuity of neighbourly relations. Therefore, the conclusion they draw from the planned construction in the region is that natural areas and existing spatial relations will be completely destroyed. This definitely affects their decisions regarding the development plan in the region.

When the participants were asked about their opinions about the planning process in the Kırcami Region, it was paradoxically also seen that there is a decrease in the belief of implementing the discussed plan because the people living in the region do not have enough information about the development plan and the process. The opinions of the participants (P8, P9, and P16) are as follows:

“We have no idea about the development. If they say it will be done in 5 years, we can no longer trust them. They tell us that Kırcami will be planned for construction when their work is done. Then there is none.” (P16)

“I have lost my faith. They make us enthusiastic and then say it has stopped. We look at road excavation in some places. One minute, they are cancelling it. My house is at the bottom of the road. The traffic and noise are too much. I would like this to be solved, but I have no hope. Big landowners always put stones in this business. There is political rent involved.” (P9)

“We have been working on this issue for 40 years. Really, both the people and the administrators are tired. We are happy when the development plan is announced, but then they file a cancellation case. No one has any trust left. This is a bad situation for the administrators. But this will be solved. It has to be solved. Yes, there is an unfair distribution, but the 18 application are like this: This is the law.” (P8)

As for the democratic decision-making mechanisms used in the process of the development plan, it was determined that 15 participants are not involved in the process at all and 5 participants follow the neighbourhood meetings with their own efforts and participate voluntarily, but they do not consider these meetings sufficient and effective. When the reasons for the interviewees to participate in the process were analysed, answers such as “they have no faith in the development plan and they are not given enough information” came to the forefront. In addition, in parallel with their aforementioned statements that they do not want their lands to be fragmented, many participants stated that if there were a participatory process, they would express their intention that they do want their lands to be fragmented through the relevant means. In addition, the participants stated that they are not sufficiently informed about the development process and that the process should be carried out in a transparent manner. The residents of the region emphasised that they do not take part in the participatory processes as a reaction to the politicians dragging the region into uncertainty by making various promises during the election processes. The participants’ views are as follows:

“I’ve only been once, and I got angry. It’s like they didn’t explain it clearly. That’s why I didn’t want to go again. They should have asked us what we wanted. They didn’t. When one of them said “fragmented parcels”, they silenced them.” (P11)

“I attended meetings, neighbourhood meetings. I went to municipal meetings. Not everyone is asked for their opinion; there are those who have more to say. They ask more to educated people (he said “upper mind”). We cannot have a say. 3–5 people make decisions.” (P17)

“They come from the municipality, but their approach is not good. They do not give proper information. There is a lack of information. Participation is already low. I think they misinform the public, and I think the public is provoked against the parties and local administrators. If the local administration had acted a little more transparently, last year’s protests would not have happened. This is a very dangerous situation.” (P4)

“I always go to the meetings. I think the district municipality is making an effort on this issue. It would not have happened without their efforts. The mayor is determined on this issue. But the public is not very knowledgeable. We are primary school graduates. We won’t understand if they come and explain things at a high level. They need to explain one by one. People cannot come here because of work. If necessary, they should go to their fields and tell them.” (P13)

When the opinions of the participants on whether the investors in the region influence the planning process in line with their own interests at the expense of an open and inclusive public political debate were analysed, 15 participants stated that the investors influence and direct the development plan, 1 participant stated that they are unaware about this issue, and 4 participants stated that the investors cannot influence the development plan. The statements of some participants (P19, P18, and P11) who think that investors participate in the planning process are as follows:

“They collect 100 m2–50 m2 plots from everywhere. They are influencing the development process. They will collect the plots and displace us. The land is already fragmented.” (P19)

“Of course it does. Those with 20–30 or even 70–80 hectars of land definitely affect the plan. They usually object to the process.” (P18)

“I’m sure of it. The whole neighbourhood is sure of it. Our own neighbour sold his land to an investor. They were forced to sell it. But we heard that the person they sold it to bought many plots. That’s how they collect land. Of course, they also affect the process.” (P11)

The views of some participants (P15, P8) who think that investors have no influence on this issue and that this process is rather political are as follows:

“How much will they affect it? Maybe they object, but the municipality does not accept it. There is a lot of rent here. I think this has more to do with politics than investors. It gets complicated there.” (P15)

“This situation is much talked about. Of course, those who have a lot of land should have a say. But I don’t think this will be done publicly. The plan is being prepared according to the law. Of course, those who have too much land should get their share.” (P8).

In a nutshell, the following participant’s views depict the decision-making process of the Kırcami development plan, which lacks participatory tools:

“ I was only involved in two meetings, one of which was the meeting attended by the minister in 2019, where symbolic title deeds were distributed. Only the minister spoke there and stated that the planning process would accelerate. No one could ask questions. The second meeting I attended was before the referendum in 2021. No one could ask questions, and those who stated that the plan was unfair were silenced. These meetings are for show, and no democratic process is carried out. It is important to have an equal voice and to answer questions in a language that everyone can understand. But in these meetings, only legal statements and technical statements about planning were used. For this reason, I do not think that a democratic process was carried out” (P20).

3.2. Preferences and Participation of the Investors for the Kırcami Area/Plan

For defining the preferences of investors, as can be seen in Table 1, 10 participants who invest in the Kırcami Region were interviewed according to their land size, location, and socio-economic status. As Table 4 indicates, the investors bought lands in the neighbourhoods of “Güzeloluk, Zümrütova, Kırcami Mahallesi, Yeşilova, Tarım, Mehmetçik, and Topçular” in the Kırcami area. However, when we analysed their residence, half of the investors seem to not be from this area, and they have a higher education level compared to the residents living in the area (see Table 1). It means that half of the investors are investing here just to gain rent and obtain the right to construction land use. Table 4 surprisingly reveals that contrary to the residents, there is an almost complete congruence between the type of land use determined for the investment area in the current plan and the type of land use expected for the plan to give to the investment area. Except for one investor, all investors expect residential and commercial areas from the plan for their lands. This congruence between investors’ expectations and preferences confirms both their short-term, rent, and economic interest-oriented preferences regarding Kırcami and residents’ claim that investors have more power and resources in terms of influencing the planning process in line with their own interests, as shown in Table 1. As we have stated in the findings related to the residents, in addition to many different economic reasons, one of the most important reasons that investors do not exhibit more sustainable preferences for urban agriculture in Kırcami is that the planning process fails to use genuine deliberative democracy tools where all actors can negotiate and transform their conflicting preferences.

Table 4.

Current land use types of investors in their fictions from the plan and additional income sector, the neighbourhood being invested in, the amount of land they own, and their joint or individual investments (created by the authors).

The most important reason for investing in the Kırcami area is rental opportunities. All the participants stated that they invest in the region due to the rental opportunities for the future. The other reason for investment for the ones who were born here is that they grew up in this region and they inherited some of the lands here. While closeness to the city centre, cheap prices, and the belief that they can have a say in the implementation process of the plan are the essential reasons that attract investors to this region, the opportunities for agriculture in the region are among the other important reasons.

It was observed that while the investors are expecting rent from the region, they are also engaged in agricultural production. One participant expressed the reason for continuing agricultural production as follows:

“I continue agriculture because I inherited my land, but I will not make a new agricultural investment. Because this is a region that will undergo development. Investment in agriculture would be irrational.” (I7)

The consensus of the investors about the future of the Kırcami area is that the region cannot be built due to disagreements on the Kırcami development plan. Investors were also asked about their opinions on the current development plan and whether the land use requirements, such as housing density, centres for trade, green spaces, educational facilities, hospitals, etc., in this plan are sufficient and fair. While all the investors stated that the plan is not fair and sufficient, one investor emphasised that the plan is made in accordance with the regulations but that the problem of fragmented parcels must be solved.

Investors were also asked whether they participate in the preparation process of the development plan and what the deficiencies in the decision-making process are. According to the findings, the investors stated that the process for the development plan is not carried out transparently and that the necessary calls and announcements for meetings are not made. Some of the participants stated that they can apply to local administrations and obtain information individually and that they attend the municipal council and neighbourhood meetings. I9, I6, and I7 stated that they can actively participate in the planning process through the “Kırcami Region Development, Beautification, Culture, and Solidarity Association” and that they also attend the municipal council meetings. I8 stated that the planning process is not participatory and that the sources of the deficiencies are as follows:

“The development process was not participatory. The owners of the area were not informed about what kind of plan it would be, and they were not told what advantages this plan would provide to the owners of that area. If they had been told, objections would have been made and lawsuits would have been prevented in the post-planning process. In this plan, I think that even those who have land and live there will make a profit, and if they do business, they can do it by renting other agricultural lands nearby. The real victims will be those who do not own land in that area and do business by renting it.” (I8)

I5 drew attention to the role of civil society organisations in the participation process. His/her comment emphasised that civil society does not play an effective and solidaristic role in the reconstruction process in the Kırcami planning process. I5’s opinions on participation in the development process and the deficiencies in this process are as follows:

“If I see a very unfair situation regarding the development process, I go myself and request information from the municipality. This development issue covers 8 neighbourhoods and there is not even 1 square metre of land without title deeds. There is neither a treasury nor an area without a title deed. Therefore, this process has dragged on for too long. In other neighbourhoods adjacent to this area, there were areas without title deeds, and they were officially plundered. There is no place for them to plunder here, so they cannot move. For example, we have some NGOs; all relevant and irrelevant NGOs are talking about this place according to their minds, which plays into the hands of politicians, and we are left in the middle without asking a single thing to the public. Unless there is a more participatory process where everyone is informed, this will take much longer.” (I5)

One investor (I3), unlike the other participants, believes that the planning process requires an elitist, technical, and bureaucratic process rather than a participatory democratic perspective:

“The municipality has the authority to make development; it doesn’t ask anyone. I don’t think they should ask. They should do it according to the law. It doesn’t end when they ask the citizen. Experts determine things such as urban planners, architects, ground suitability, and population in accordance with the law. The citizen’s request never ends. They will do it directly without asking. The law is clear; the areas of expertise are clear.” (I3)

3.3. Preferences and Participation of the Local Government Officials for the Kırcami Area/Plan

As a final step, in-depth interviews were conducted with experts (urban planners) involved in the local government (one from the Muratpaşa Municipality and the other from the Antalya Metropolitan Municipality) who expressed the views of the third important actor in the development plan process for the Kırcami area.

As a general finding, when the data obtained from the interviews with the experts from the local government were analysed, it was observed that they have a decisive attitude towards the implementation of the current plan. They no longer see urban agriculture as an option for the region, and they believe that the preferences of the actors in the region for the future are mostly rent. Contrary to the answers given by the other two actors regarding the parcellation, it was observed that the local government representatives are not in consensus and that the preferences of the other actors do not coincide with the law.

The experts emphasised that an area in the centre of the city that has not been planned for various reasons has disadvantages in many aspects:

“It’s too bad that a place so close to the city is in this state… Yes, the Kırcami Region has agricultural qualities, but there is now urban pressure, so these are no longer advantages. For this reason, it is necessary to plan to provide these advantages. The people of Kırcami do not want what you call natural life there.” (E2)

Since agricultural production still continues in the region, experts from the local government were asked about the agricultural productivity of the region and whether a planning process that can ensure the continuity of agricultural production in this region can be made. It was revealed that there are some differences of opinion in the answers given by the experts to these questions:

“The level of agricultural productivity of the Kırcami Region is not suitable for growing crops. In addition, agriculture is not a sufficient source of income for the residents. For this reason, the probable income from development is more advantageous for them.” (E1)

“The issue of agricultural productivity is not realistic. There is still production in the region, and it is obviously productive. In order to plan a place, it should not have an agricultural characteristic, but the region has an agricultural characteristic. But there is also urban pressure, and therefore it is necessary to make the plan in the name of the public interest.” (E2)

One of the experts stated that an alternative way for the continuation of agricultural production in the Kırcami Region would be rural planning instead. S/he, however, noted that the preferences of the people living in the region are, on the contrary, not to continue agricultural production. S/he expressed his/her views as follows:

“Rural planning may be an alternative, but the expectations in Kırcami have changed. If you say, Let’s preserve the agricultural quality of the region, you should not make a plan. There is a precedent of 0.80 here, so there should not be large parcels; you cannot do that… The expectation of the people living there is simple: to get houses that they can live in and/or rent out… Urban agriculture is not possible for this area; I think this would never match the expectations there.” (E2)

Experts from the local government were also asked about the advantages of the plan being cancelled after the objections and the reasons for the cancellation, as follows:

“The current cancelled plan was prepared in accordance with the Law and Regulations, integrated with Antalya’s Transportation Master Plan, in terms of urbanisation and in accordance with the Master Plan, as confirmed by the expert report. The plan was insufficient in terms of reinforcement areas.” (E1)

“The plan has no advantages. The plan was already very bad. There is neither climate sensitivity nor disaster sensitivity. The parcellation is over now; if the parcellation was not over, maybe these sensitivities could have been included in the plan. But now the plan will go as it is… The purpose is not to open this area for development, nor is it to make a good plan. This is what the public expects. Citizens are not interested in how correct the plan is for the city.” (E2)

One expert from the district municipality and one from the metropolitan municipality were interviewed to verify whether these two main actors of local governments work in harmony regarding the Kırcami plan. The planning process is carried out by the district municipality in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity; therefore, coordination with the metropolitan municipality is a must in this process. The responses indicate that even though there is cooperation for the realisation of the plan, there is no consensus between the two actors in the background. The views of the experts regarding this process are as follows:

“We believe that both municipalities work in harmony and in coordination in line with the planning hierarchy.” (E1)

“Actually, there is not much consensus. Both institutions carry out procedures for the plan to work. There is a problem with parcellation, and the direct procedure is applied. Because this time there may be accusations, such as that we wanted to do it and they didn’t... The district municipality is firmly against any change in parcellation, but they will have to go back to the root title deed.” (E2)

One of the objections made regarding the development process of the Kırcami area by several NGOs of the city was that the region should not be opened to construction since it has an agricultural area feature. However, in the ongoing process, some experts’ reports claim that the region is no longer agriculturally efficient [51]; so, they prefer no future for agriculture in the area and thereby apply their preferences for future development plans from a more rent-oriented perspective.

Finally, considering the democratic nature of the planning process, there is consensus on the answers regarding the parcellation process. The experts stated that the parcellation process had some handicaps, and they expressed that “the laws and the expectations of the citizens do not coincide” and pointed out that the objections made were related to legal processes. In addition to this, expert E2, who stated that the parcellation process is not transparent, expressed the problem as follows:

“The public did not participate in this plan at all, of course. What concerned the public the most was the parceling. But the parcelling was done and approved behind closed doors. No one knows how it was done. A team should have been established for this, and this team should have had a public relations desk. And the people living in the region should have been asked… When the citizen was given an opportunity to talk to the geomatics engineer, there would have been interaction, but this was not done...The parcellation is also very bad… Honestly, I don’t know whether the parcellation is fair or not, but the plan itself and its construction were made according to the big investor. Large islands were made to minimise the loss. In other words, when we were making this island, we were trying to minimise casualties. There are parcels that are unfairly distributed now, but some of them are definitely technical necessities. I think 5–10% is unfair. In the grounds for the cancellation of the plan, there are certain criteria in the distribution principles, but the general grounds for cancellation are the issue of agricultural quality.” (E2)

While one of the experts stated that the democratic decision-making mechanisms are not very well-handled and -managed, the other argued that participation in the planning process is sufficient in terms of participatory democracy practices.

“Actually, I think those neighbourhood group meetings were a bit of a formality. In the referendum issue, the aim was to gain a political front in public opinion.” (E2)

“The referendum was sufficient in terms of the number of participants. In the development process, a development plan, which ensures the participation of all stakeholders in the city as a whole and locally, was prepared.” (E1)

In the answers given by the local experts to the questions about the justifications of the lawsuits filed against the existing plan, the experts pointed out that the objections were made without creating and providing an alternative plan, and, therefore, these objections were not sufficiently justified. In addition to this, it was also emphasised that although professional chambers are important non-governmental organisations to create these alternatives, they did not work effectively in the decision-making process.

“The Chamber [Chamber of City Planners] has made no contribution to this issue. It has no discourse. In fact, they are making it worse. They talk about cooperation and so on. However, they do not say this plan is wrong; let’s redo this plan; we have such an alternative plan. They file a lawsuit for the cancellation of the plan without presenting an alternative.” (E2)

Despite the aforementioned criticism levelled against civil society organisations, one expert also noted that so many experts from various fields came together and tried to establish a dialogue with local administrations regarding the Kıcami plan and that they intended to cooperate in solving some of the problems in the plan. E2 stated the following:

“We actually formed a team of ‘technical wise people’ in relation to these processes. We worked for days; we tried to put the plan together and correct the plan without changing it. The team included architects, an expert in urban design from Far Eastern countries, and planners. We made preparations and went to a presentation at the district municipality. It was a presentation that included a comparison of Kırcami and other urban spaces known in the world. However, the manager of the district municipality was disturbed by this presentation and did not allow the presentation to be finished. He replied to the presenter in English:

“It’s too late, my friend…”.”

4. Discussion

In light of the findings of this study, five points of discussion should be emphasised. First, as Table 2 indicates and compared to the Perth, Greater Geraldton [25,26], and Grandview-Woodland [27] cases, the level of participation of residents and investors in the democratic decision-making process of the Kırcami development plan is surprisingly very low. Even though the participants’ level of education and democratic awareness are high and the deliberative tools are effectively organised and used enough by the political actors in the Australian and Canadian cases, the data and/or responses of residents and investors in the Kırcami case strikingly indicate that the participants have not internalised the value and significance of democratic participation. This is one of the salient factors that makes Kırcami different. In other words, even if all technical decision-making processes had been carried out completely, the Kırcami planning process could not gain a deliberative democratic character since the participants’ belief in democratic participation is weak and they have not internalised the deliberative democratic culture. In other words, the findings support the fact that Turkey is an entrepreneurial state that prioritises investors and economic concerns over other actors and issues and fails to integrate deliberative tools into its legislative system; thus, none of the actors, particularly the public, have the resources and opportunities to internalise democratic participation principles. This also leads both residents and investors not to exhibit more sustainable preferences for urban agriculture, as shown in Table 3 and Table 4, and the disfunction of the transformative power of deliberation in the Kırcami case. Deficiencies in the democratic decision-making process and the fact that the Kırcami planning process fails to use genuine deliberative democracy tools where all actors can negotiate and transform their conflicting preferences thus prevents the participants from exchanging ideas and revising their own views by being exposed to different demands and expectations and prevents the communication channels from working effectively.

Second, despite their flawed aspects, it is unfair to say that no democratic decision-making process is used in the Kırcami planning process. A referendum was conducted by the local government. On 2 January 2022, a referendum was held on the development plan for 10 neighbourhoods. In the referendum, only those living in the neighbourhoods within the planning boundaries and those registered in the electoral register could vote. In the area with a population of approximately 27,000, 5219 valid votes were cast. A total of 87% of the votes were “yes” [56,57]. It should, however, be noted that even though a referendum is an important tool of direct democracy, referenda can also be used as supplementary tools of representative democracy to respond to the increasing demand for direct citizen involvement in decision-making processes. In other words, instead of regarding direct democracy as the core decision-making mechanism used in making development plans, referenda can be viewed as a secondary/token instrument supporting indirect democracy’s central role in decision-making processes. Leading studies support this claim that referenda and other direct democracy instruments that are not underpinned by deliberative democratic tools “(…) [may] reduce all decisions to simple yes-or-no alternatives” [58] (p. 150). Thus, direct democracy without deliberative aspects and tools may lead to a decrease in the level of discussion among voters. More importantly, in terms of lack of information in decision processes, if voters cannot access effective and sufficient “information shortcuts”, it is possible that “direct democracy may end up producing outcomes that they later regret” [59] (p. 479).