Abstract

Population aging presents a significant global challenge. In China, the aging of the rural population coincides with inefficient rural homestead utilization. While the Chinese government has enacted policies to address this, their impact remains limited. Utilizing survey data from 403 rural families in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, China, this study applies the binary Logit and mediating effect models to analyze the impact of rural family population aging on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from homesteads with compensation and their compensation preference. Key findings include: (1) Family population aging intensifies farmers’ willingness to withdraw from homesteads, with a stronger preference for non-monetary compensation as aging increases. (2) Regarding the willingness to withdraw with compensation, farmers’ cognition of homestead security value masks the effect by 4.71%, while asset value cognition has no mediating effect. (3) With regard to promoting non-monetary compensation choices, farmers’ homestead asset value cognition fully mediates at 16.01%, but security value cognition is without mediating effect. Based on these findings, it is recommended that the government crafts tailored homestead withdrawal policies considering farmers’ family age structure. Further, efforts should aim at refining farmers’ understanding of homestead values, promoting a blend of non-monetary and monetary compensations.

1. Introduction

As life expectancy increases and population fertility rates decline, populations are aging at an accelerating rate globally [1]. The aging of the population is the inevitable result of demographic transition and an important issue facing human society in the 21st century [2]. Aging can be defined as a dynamic process where the proportion of the elderly population increases within the total population due to a decrease in the number of young people and an increase in the number of elderly people. According to international consensus, when the elderly population over 60 years old accounts for 10% of the total population in a country or region, or the elderly population over 65 years old accounts for 7% of the total population, that country or region is considered an aging society. Referring to the World Population Prospects (2019 Revision) released by the United Nations, from 2000 to 2020, the proportion of the elderly population aged 60 and above increased from 9.9% to 13.5% [3]. Projections suggest that by 2035, the global aging process will continue to advance, and the proportion of people aged 60 and over in the total population will rise to 17.8%. By 2050, the world is predicted to enter a moderately aging society, with the proportion of elderly people aged 60 and overreaching 21.4%. The aging of the population has thus emerged as a major challenge for all countries worldwide. In this context, it is crucial to explore strategies for achieving sustainable economic development.

In parallel with these demographic shifts, the rapid advancement of urbanization has been driving a significant change in the population’s place of residence, from rural to urban areas. This rural depopulation is a global phenomenon, observed in regions like Australia, Japan, Europe, and North America [4]. As per United Nations data, about 56% of the world’s population resided in urban areas by 2021, a proportion projected to reach 61% by 2031. Moreover, the latest State of the World’s Cities 2022 report by UN-HABITAT predicts that the global urban population will swell by 2.2 billion by 2050, raising its share to 68% [5]. This population migration primarily involves the young and middle-aged labor force moving to cities and towns, resulting in accelerated aging of the rural population. This shift has triggered a series of issues. The aging of the rural population directly impacts agricultural production, primarily through a sharp decline in the labor force. This reduction leads to the abandonment of arable land and the downsizing of agriculture. Moreover, this rural aging phenomenon also contributes to the gradual “hollowing out” of villages, reflected in the long-term idleness of numerous rural houses and significant land wastage. In light of today’s food security concerns and rural revitalization efforts, realizing efficient utilization of land resources becomes paramount.

In China, we face the above problems as well. Like many other countries, China’s reform and opening-up in the late 1970s sparked rapid urbanization and industrialization, resulting in a significant migration of rural populations to cities [6]. According to statistics, the rural population dwindled from 790 million to 560 million between 1978 and 2018 [7]. In stark contrast, the total area of homesteads ballooned by 14 million hectares from 1995 to 2014 [8]. As of 2018, China’s idle rate for rural homesteads was at least 20% [9], while China is currently facing a contradiction between the red line of arable land and urban construction land expansion. According to the third national land survey, the total area of national construction land increased by 85,333.3 square kilometers compared to the second survey, marking a growth rate of 26.5%. Concurrently, the cultivated land area decreased by 75,333.3 square kilometers. China’s existing cultivated land spans 1.278 million square kilometers. If the decline continues at this pace, it is projected that within 10 years the area may fall below the set red line of 1.2 million square kilometers, potentially jeopardizing the food security of 1.4 billion Chinese people. In response to this situation, the “Rural Revitalization Strategic Plan (2018–2022)” was formulated and implemented by the central government of China. Meanwhile, the plan has emphasized the need to guide rural collective economic organizations to unleash the potential of collective land and other resources and assets. Thus, the urgent need to revitalize rural idle homesteads and promote intensive and efficient use of rural land resources is evident.

Given this situation, strategies for revitalizing rural homestead resources and unveiling their asset value have become an important facet of China’s rural land system reform. To tackle the above issues, the Chinese central government has rolled out a series of policies aimed at cautiously advancing the reform of the rural homestead system. In 2015, the central government approved 15 counties and cities as pilot sites for this reform, with a focus on exploring mechanisms for voluntary homestead withdrawal with compensation. By 2020, the number of pilot sites had been expanded to 104 counties and cities and three prefecture-level cities. The No. 1 document issued by the Central Government from 2017 to 2023 addresses rural homestead reform and encourages farmers to voluntarily withdraw from the homestead with compensation according to law. Nevertheless, farmers are often reluctant to leave their homesteads, mainly due to worries about the cost of living upon relocating to the city [10]. This reluctance is particularly pronounced in the context of increasing rural aging, as the burden of supporting the elderly has become a significant factor impeding farmers’ withdrawal with compensation from their homesteads [11]. According to the seventh national census data, the proportion of elderly individuals aged 60 and over in rural areas is 23.81%, which is 7.99 percentage points higher than in cities and towns [12]. Compared to a 4.3 percentage point gap in 2015, this difference has grown significantly. As an important security asset of farmers’ families, withdrawal with compensation from the homestead not only involves the property income of farmers, but also is closely related to the old-age security of farmers’ families. The potential impact of rural aging on homestead withdrawal with compensation cannot be overlooked, but current compensation policies seem to pay scant attention to the old-age security of farmers [13]. Therefore, in the face of the practical problems of the increasing aging of the rural population, it is necessary to explore the relationship between the aging of the population and the willingness to withdraw from the homestead and their compensation preference.

Research on population aging originated from the United Kingdom, France, and other leading industrialized countries in Western Europe [14]. As the problem of global population aging becomes increasingly prominent, the related research on aging has been continuously expanded and deepened. Typically, the research mainly involves the impact of population aging on social and economic development [15,16,17], the impact of population aging on medicine [18,19,20], the impact of population aging on the construction of social security systems for the elderly [21,22,23], and research on the evolution trend of population aging [24,25,26,27]. In addition, some Chinese scholars have analyzed the impact of population aging on agricultural production [1,28,29].

The vast majority of foreign countries have adopted private ownership of land, thereby focusing foreign scholars’ research on aspects such as farmland conversion and rural land transfer [30,31,32,33]. However, the concept of the rural homestead holds a unique place within the Chinese background. In China, a rural homestead refers to land that is owned by the rural collective, but where individual Chinese citizens hold the right to build houses, by law. The academic community has shown an increasing interest in the complex issue of rural homesteads in China recently. Currently, scholars have conducted extensive theoretical and empirical studies on the matter of homesteads. These studies span a wide range of methodologies and topics. For example, Lu Xiao et al. employed CiteSpace and VOSviewer to perform a visual analysis and mapping of articles in homestead-related fields [34], while Bao et al. utilized the case analysis method to delve into examples of local homestead reform [35]. Su et al. focused on the functional evolution and dynamic mechanism of homesteads, using the comprehensive index model evaluation method [36]. Furthermore, binary logistic models [37,38], structural equation models [39,40,41], and mediating effect models [42,43] are among the most common methodologies that scholars employ to explore farmers’ willingness and behavior regarding withdrawing from rural homesteads from various angles. In terms of content, homestead withdrawal is a hot topic in current research. This topic encompasses several sub-areas, primarily including practical exploration [44], mechanism construction [45], and the behavioral intention associated with compensation for rural homestead withdrawals. Notably, among these, the research focusing on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from their homesteads is the most extensive. Some scholars have identified the fact that farmers’ personal characteristics or family characteristics significantly influence their willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, through field research [46,47,48]. Some scholars also found that ownership consciousness [49] and risk expectation [50] also had an impact on their willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation. These explorations have underscored that a farmer’s decision to withdraw from the homestead with compensation is not solely dictated by objective individual conditions, but also significantly influenced by subjective factors such as individual cognition.

Despite the fact that there are large extensive studies, a significant portion has overlooked the reality of the intensifying issue of rural population aging in China. Only Sun et al. investigated the effects of this demographic shift on the farmers’ behavior regarding the withdrawal with compensation from homesteads [51]. Their findings suggested that the larger the proportion of family members over 60 years old, the stronger the inclination to retain homesteads. Indeed, the interplay between factors such as farmer differentiation [52], their property rights cognition [53], and their willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation comprises a complex mechanism. The farmers’ value cognition of their homestead and local attachment serve as intermediary factors, while intergenerational differences play a regulatory role [54,55]. Previous studies have established that age differentiation can result in variations in individual behavior and cognition and that the farmers’ value cognition of the homestead significantly impacts their willingness to withdraw with compensation [54]. Despite these findings, no research has yet explored the relationship between these three factors. Researchers such as Wang et al., Chen Ming, and Gong et al. have systematically studied how farmers’ heterogeneity impacts their preferences for homestead withdrawal compensation [56,57,58]. Their findings indicate that the heterogeneous characteristics of farmers’ family income differentiation, regional living differences, and urban housing ownership can influence these preferences. Additionally, some scholars have quantitatively analyzed the impact of homestead withdrawal compensation methods and standards from the perspective of farmers’ interaction [59], and farmers’ functional cognition [60]. However, few studies have focused on the relationship between the aging of rural families and farmers’ homestead withdrawal compensation preferences.

Considering the existing gaps in research, this paper integrates the aging of the rural family population, farmers’ value cognition of homesteads, the willingness for homestead withdrawal with compensation, and the compensation preference for homestead withdrawal into a unified analytical framework. Relying on the survey data from 403 rural families in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, China, this study utilizes the binary Logit model and the mediating effect model, based on the theory of neoclassical economics and the theory of cognitive psychology, to empirically analyze the influence and mechanism of rural family aging on the willingness and compensation preference for homestead withdrawal with compensation. Furthermore, this paper explores the role of homestead value cognition throughout this process. This investigation aims to offer a reference for the formulation of homestead withdrawal policies against the backdrop of rural population aging. Meanwhile, China’s experiences with land system reform can provide valuable lessons for other countries, particularly those in the developing world.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical analysis and research hypotheses. Section 3 introduces the data sources, variable selection, and model design. Section 4 presents and analyzes the empirical results. Section 5 describes the discussion. Section 6 gives the conclusions.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Characterization of Age Differentiation

In previous studies, scholars have commonly employed a variety of indicators such as the aging rate, the dependency ratio of the elderly population, the proportion of the child population, and the average age to measure the degree of family aging. Among them, the aging rate is the most commonly used indicator to measure the degree of population aging [61]. In this paper, we adopt the population aging rate of families to measure the degree of population aging within families. Defined as the proportion of the elderly population aged 60 and above in the total population of families, the population aging rate of families effectively illustrates family aging. Therefore, the larger the proportion of the elderly population, the greater the degree of family aging, and vice versa.

2.2. The Direct Impact of Family Population Aging on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from the Homestead with Compensation and Compensation Preference

The essence of farmers’ withdrawal from the homestead is the disposal of homestead assets. According to the theory of neoclassical economics, farmers, acting as “rational economic man”, withdraw from their homesteads with compensation primarily to pursue the maximization of economic interests. Only when the risk associated with withdrawal from the homestead falls within the farmers’ tolerance, and the benefits derived from the withdrawal outweigh the associated costs, will farmers choose to withdraw from the homestead [62].

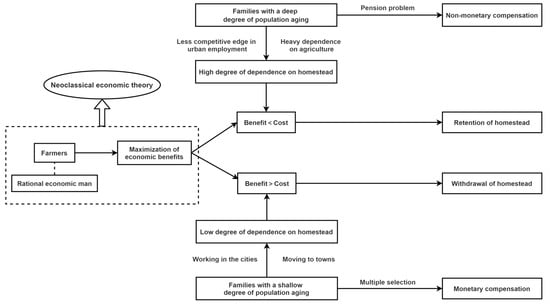

This paper constructs a theoretical analysis framework, as depicted in Figure 1. This paper posits that rural families with a high degree of population aging have less of a competitive edge in urban employment. These families often rely on their homesteads to provide a self-sufficient lifestyle, with their existence and productivity largely dependent on agriculture, which effectively minimizes living costs. Farmers’ daily living expenses tend to surge when they surrender their homesteads. The compensation offered by the government in exchange for relinquishing the homesteads fails to offset the farmers’ long-term livelihood costs. As a result, the benefits derived from surrendering the homesteads are outweighed by the costs incurred, which makes these highly aged rural families more reliant on their homesteads and prone to retain them. In contrast, rural families experiencing a relatively lower degree of population aging tend to carry a smaller family pension burden. Members of these families typically reside in urban areas and towns, exhibiting a lower dependence on their homesteads and incurring fewer costs upon their withdrawal. Simultaneously, the opportunity to monetize their assets through paid withdrawal from homesteads presents itself. The compensation helps alleviate some pressures of urban living for these farmers to a certain extent. The benefits of homestead withdrawal outweigh the costs, leading these families to opt out of their homesteads. The issue of family pensions remains a crucial factor influencing farmers’ choice to withdraw and the type of compensation they choose. Farmers with varying degrees of population aging exhibit different sensitivities toward compensation methods. Farmers experiencing a higher degree of population aging bear the significant burden of providing for the aged. Their desire for stability inclines them towards non-monetary compensations such as housing or social security, which offer basic living security. Thus, they tend to favor non-monetary compensation methods. However, families with a relatively lower degree of population aging often have stable residences in cities and towns, and carry a smaller burden of family pensions. Therefore, they tend to opt for monetary compensation methods, which can provide capital for their multiple future choices. This analysis leads us to our hypotheses:

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework of the Influence of Family Population Aging on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from the Homestead with Compensation and Compensation Preference.

H1:

The aging of the family population inhibits the willingness of farmers to withdraw from the homestead with compensation.

H2:

The aging of the family population promotes farmers to choose non-monetary compensation methods.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Homestead Value Cognition

2.3.1. The Impact of Family Population Aging on the Value Cognition of Homestead

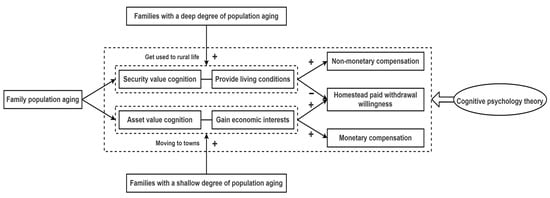

The concept of farmers’ homestead value cognition is established upon the elucidation of perceived value as observed in the marketing field. Perceived value, as understood from an individual’s perspective, enables the customer to assess the value of a product according to their understanding of the product’s functionality, quality, economy, etc. [63]. When speaking about farmers’ value cognition of homesteads, it predominantly refers to the farmers’ holistic evaluation of the multi-functional aspects of a homestead. Reflecting on the current scenario, offering residential and retirement facilities appears to be the most critical function of rural homesteads. Nonetheless, as urbanization rapidly progresses, the function of homestead assets has become increasingly pronounced. There is an observable variance in behavioral cognition among individuals of different ages [54]. This paper creates an analytical framework, as depicted in Figure 2. Families in areas with a pronounced aging population often have a strong demand for homestead security due to their adherence to rural life and lower living costs. As a result, these families possess a deep understanding of the security value of homesteads. When considering asset value cognition, because the realization and security functions of asset functions such as homestead renting, buying, and selling cannot coexist, families with a highly aging population have a weak cognition of this value. For families with a less aged population, a majority of the members gradually transition to urban areas due to reasons such as work and the living environment. Depending primarily on non-agricultural labor in cities for income, they no longer rely on homesteads for survival. This situation leads to a shallow comprehension of the security value of homesteads, shifting their focus towards the value of homestead assets. Therefore, the impact of an aging rural family population on the cognition of homestead value is reflected in the fact that families with a more substantial aging population have a deeper understanding of homestead security functions and a lesser grasp of homestead asset functions. In other words, the aging of the family population positively impacts the cognition of homestead security value and negatively affects the recognition of homestead asset value.

Figure 2.

Theoretical Framework of Family Population Aging Affecting Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from the Homestead with Compensation and Compensation Preference through Farmers’ Cognition of Homestead Value.

2.3.2. Impact of Homestead Value Cognition on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from the Homestead with Compensation

Cognitive psychology theory underscores that cognition is fundamental to intention and behavior, with individuals’ cognition shaping their preferences and thus influencing their decision-making. Consequently, farmers’ value cognition of homesteads is bound to exert a certain degree of influence on their willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation [54]. As farmers age, their economic expenditure patterns and risk tolerance fluctuate, leading to variations in the cognition of homestead security value and asset value at different ages. The security value of a homestead is demonstrated in its ability to provide basic living conditions for farmers and to effectively lower living expenses. Hence, the deeper a farmer’s understanding of the security value of homesteads is, the more likely they are to retain them. On the other hand, the asset value of a homestead is displayed through the potential for descendants to inherit and gain benefits via leasing, selling, or collecting from homesteads. Voluntarily withdrawal from homesteads with compensation is one of the significant methods of realizing this asset value. Therefore, the deeper the farmers’ cognition of the value of homestead assets, the more inclined to withdraw from the homestead with compensation. This analysis leads us to our hypotheses:

H3:

The cognition of homestead security value has a negative mediating effect with regard to family population aging affecting farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation.

H4:

The cognition of homestead asset value has a negative mediating effect with regard to family population aging affecting farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation.

2.3.3. The Impact of Homestead Value Cognition on Farmers’ Homestead Withdrawal Compensation Preference

Individual cognition determines one’s preference, and farmers’ cognition of homestead value is bound to influence their preference for homestead withdrawal compensation. As a “rational economic man“, when farmers choose to withdraw from the homestead, they will choose the compensation method to maximize their interests. The deeper the farmers’ cognition of the value of homestead security, the more they pay attention to the basic living conditions that the homestead can provide. The increase in living costs caused by the withdrawal from the homestead will make them tend to choose non-monetary compensation methods such as replacing it with urban housing that can provide more basic living security. The deeper the farmers’ cognition of the value of the homestead assets, the more they pay attention to the economic value that the homestead can provide. The economic advantages brought by withdrawal from the homestead can provide strong support for improving the quality of urban life and job selection. Therefore, they tend to choose a more flexible distribution of monetized compensation methods such as one-time capital compensation. This analysis leads us to our hypotheses:

H5:

The cognition of homestead security value has a positive mediating effect with regard to family population aging affecting farmers’ homestead withdrawal compensation preference.

H6:

The cognition of homestead asset value has a negative mediating effect with regard to family population aging affecting farmers’ homestead withdrawal compensation preference.

3. Data Sources, Variable Selection, and Model Design

3.1. Data Sources and Sample Description

3.1.1. Data Sources

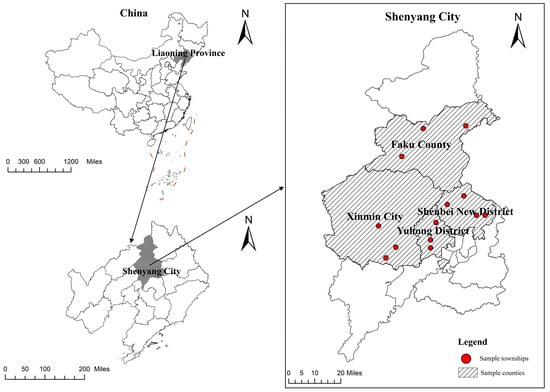

Population aging is an undeniable trend in China. Notably, the northeast region is grappling with the country’s most severe population aging challenges. Data from the seventh national census reveal that the aging rate of Liaoning Province tops the nation at 25.72%, marking it as the province with the most pronounced population aging. A combination of low birth rates and high net migration rates primarily drives the aging issues in the three provinces of Northeast China. A declining economy, widening of regional differences in urbanization level, aggravation of the contradiction between urban and rural areas, and continuous negative growth of population render the rural development of the three provinces of Northeast China volatile [64]. As the capital of Liaoning Province and the largest central city in Northeast China, Shenyang demonstrates outstanding political, economic, and cultural-center functions. This prominence generates a powerful radiative effect and drive, luring the rural population to migrate to urban areas, and leading to a widespread idleness of surrounding rural homesteads. Shenyang (41.20°~43.04° N, 122.42°~123.81° E) is located in the south of Northeast China and the central part of Liaoning Province, which is the center of the Northeast Asian economic circle and the Bohai economic circle (Figure 3). Shenyang spans a total area of 12,860 square kilometers and encompasses 13 county (district) level administrative regions, including 10 municipal districts, one county-level city, and two counties. By the end of 2020, Shenyang housed a permanent population of 9.073 million, consisting of 7.668 million urban dwellers and 1.405 million rural residents, resulting in an urbanization rate of 84.51%. Approximately 600,000 rural homesteads exist within the city, spanning an area of about 568.7 square kilometers. On average, each homestead covers an area of about 836.7 square meters. Roughly 21,000 homesteads remain idle, occupying an area of about 18.2 square kilometers, yielding an idle homestead rate of 3.5%. In 2020, Shenyang was designated as one of the pilot areas for the new round of rural homestead system reform in the country, which has offered a vast number of samples in support of this research. The data of this study are derived from a sample survey of farmers in Shenyang conducted in July 2021. This research adopts a mixed approach of stratified sampling and simple random sampling to select sample farmers. Firstly, in adherence to the principle of far, middle, and near to the county, three streets were randomly selected at three levels. Secondly, following the principle of high, medium, and low homestead idle rates, each street randomly selected three villages within three tiers. Finally, 12 farmers from differing families were randomly chosen from each village. A total of 405 questionnaires were gathered from four districts, 13 streets, and 35 administrative villages. After eliminating the questionnaires with distorted or missing key information, 403 valid questionnaires were secured, boasting an effective rate of 99.51%. The farmer questionnaire survey primarily employed a method of a “one-to-one” interview between the farmer and the investigator. The main contents of the questionnaire encompass the farmers’ family situations, their understanding of homestead value, subjective satisfaction, and so on.

Figure 3.

Study area and location of sample townships.

3.1.2. Sample Description

According to the statistical results of the questionnaire, among the 403 surveyed farmers, farmers aged 60 and over accounted for 53.85%, indicating that the rural aging problem in the surveyed areas is serious. The proportion of the labor force in rural families generally exceeds 0.5, representing 86.35% of the total sample size. The ratio of part-time farmers reaches a substantial 99.26%. In the survey on the willingness of farmers to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, 309 families have indicated their willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, accounting for 76.67% of the total sample. Among them, 164 families chose monetary compensation, accounting for 53.07% of the total number of farmers willing to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, and 145 families chose non-monetary compensation, accounting for 46.93% of the total number of farmers willing to withdraw from the homestead with compensation.

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Explained Variables

In this paper, farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and compensation preferences are selected as explained variables. To gauge the farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead, we designed the questionnaire with the question, “Are you willing to withdraw from your homestead with compensation?” The responses were coded as binary dummy variables: value 1 for willingness to withdraw from their homesteads, and 0 for unwillingness. Similarly, we aimed to understand farmers’ compensation preference for homestead withdrawal by posing the question, “Which withdrawal compensation method are you more inclined to choose?” If farmers lean towards monetary compensation, the response was coded as 1. For a non-monetary compensation preference, we assigned a value of 0.

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

This paper selects the aging degree of the rural family population as the core explanatory variable. Referring to the relevant research, in the empirical study, the proportion of the elderly population in the total population, the average age, the elderly dependency ratio, and other indicators are generally used to measure the degree of aging. Based on the international definition of aging, this paper uses the family population aging rate to characterize the degree of family population aging. The family population aging rate refers to the proportion of the elderly population aged 60 and above in the family compared to the total family population.

3.2.3. Mediator Variables

This paper selects the value cognition of farmers’ homesteads as the mediator variable, which is subdivided into the security value cognition and the asset value cognition. In the survey, farmers’ judgments on the two survey questions of “the homestead can be used to live and reduce the cost of living“ and “the homestead can be left as property to future generations“ were used to refer to their corresponding homestead value cognition [54]. The index adopts a Likert five-point scale, where 1 means “extremely unimportant”, 5 means “extremely important“. The higher the score, the deeper the value cognition of farmers.

3.2.4. Control Variables

Considering other factors that may affect farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and compensation preferences, this paper mainly selects control variables from three aspects: householder characteristics, family characteristics, and farmers’ satisfaction: (1) Variables of householder characteristics including gender, age, and education level; (2) Family characteristic variables including the number of the non-agricultural labor force, the total non-agricultural income, the number of left-behind elderly, and the familiarity of the second generation of farmers with agricultural farming; (3) The satisfaction of farmers including their satisfaction with rural infrastructure, their satisfaction with the rural ecological environment and their satisfaction with the rural living consumption level. The descriptive statistical analysis results of the data with farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and farmers’ compensation preference as the explained variables are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Variable selection and descriptive statistical analysis results.

Table 2.

Variable selection and descriptive statistical analysis results.

3.3. Model Design

3.3.1. Binary Logit Model

The Logit model is also a “logistic regression”, which is a commonly used method for empirical analysis. In this paper, the dependent variables of “farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation” and “which type of compensation is more favored” are assigned to 0 and 1, so the binary Logit model is selected for regression analysis. The model is defined as follows:

In Formula (1), represents the willingness to withdraw or compensation preference of the farmer’s homestead; is the population aging rate of the family; is the control variable; is a constant term; c and are the parameters to be estimated, where the coefficient c is the total effect of the family population aging rate on the willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation or the preference for compensation; is a random error term.

3.3.2. Mediating Effect Model

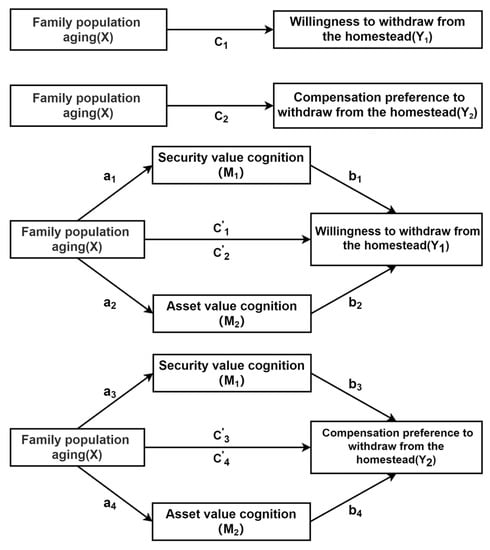

To further investigate whether the population aging rate of families has an impact on the willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and the compensation preference through the cognition of the value of the homestead, this paper adopts the mediation test procedure proposed by Wen et al. [65]. The mediation effect is examined based on the total effect of the family population aging rate on the farmer’s willingness to withdraw with compensation and compensation preferences. The test process is shown in Figure 4, and the specific model is defined as follows:

Figure 4.

Mediating effect testing process.

In Formula (2), is the value cognition level of the farmer’s homestead, and coefficient a is the effect of the aging rate of the family population on the value cognition of the farmers’ homestead; in Formula (3), coefficient b is the effect of farmers’ cognition of homestead value on the willingness or compensation preference of homestead paid withdrawal; the coefficient c’ is the direct effect of the family population aging rate on the willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation or the preference for compensation; and are random errors. According to the mediating effect test process proposed by Wen et al. [65], the first test is whether the coefficient c in Formula (1) is significant; secondly, the significance of coefficients a and b in Formulas (2) and (3) is tested in turn, to judge whether the indirect effect ab is significant; finally, if the indirect effect is significant, the c’ significant situation in Formula (3) is judged to be a complete mediating effect or a partial mediating effect. At the same time, it is necessary to compare the direction of ab and c’ symbols. If ab and c’ are the same, the results are explained by the mediating effect. If ab and c’ are different, the results are explained by the masking effect.

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

Considering that there may be multicollinearity among multiple variables, the multicollinearity test is first performed on all explanatory variables. The results show that the VIF values of all explanatory variables are less than 10, and the Mean VIF is less than 2, indicating that there is no multicollinearity among the existing explanatory variables. Then, stata16.0 software is used to empirically test the mechanism of family population aging rate affecting farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead and compensation preference. The regression results of the model are shown in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 3.

Regression results of the total effect of family population aging on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead and compensation preference.

Table 4.

Regression results of the mediating effect mechanism of farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead.

Table 5.

Regression results of the mediating effect mechanism of farmers’ homestead withdrawal compensation preference.

4.1. Total Effect Analysis

The regression results are shown in Table 3. In Model 1, the aging rate of the family population has a significant positive impact on the willingness of farmers to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and the coefficient = 2.072. That is, the higher the level of family population aging rate, the more farmers are inclined to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, invalidating Hypothesis 1. The reason is that since the reform and opening-up, with the increasing advancement of China’s urban and rural policies, the relationship between urban and rural areas has changed significantly, showing a trend from urban-rural division to gradual integration, and the economic links between urban and rural areas have become closer. Economic development has made most of the current rural farmers become part-time farmers. Family income has increased year by year, and farmers’ requirements for quality of life have been increasing. At the same time, young family members tend to settle in cities and towns. The feeling of missing relatives and the inconvenience of leaving their children’s lives lead to the desire of farmers to move to cities and towns to live with their children. The relatively sound infrastructure and developed medical level of the town make it convenient for farmers to provide for the aged while improving the quality of life and improving living conditions. The compensation obtained by withdrawing from the homestead can alleviate the pressure of family pensions to a certain extent. Changes in the external environment have changed the willingness of the elderly population to withdraw from the homestead with compensation. Therefore, the greater the proportion of the elderly population in the family, the more farmers are inclined to withdraw from the homestead with compensation.

In Model 2, the aging rate of the family population has a significant negative impact on the compensation preference of farmers’ homestead paid withdrawal and the coefficient = −0.897. That is, among farmers who have the willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, the greater the aging of the family population, the more farmers tend to choose non-monetary compensation, and Hypothesis 2 is verified. The results of this study confirm the previous theoretical analysis that long-term and stable housing security is more attractive to the elderly population, and the “stability“ mentality makes it more sensitive to non-monetary compensation methods such as housing or social security that can provide basic living security. Therefore, rural families with a large proportion of elderly members tend to choose non-monetary compensation methods.

4.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

4.2.1. The Mediating Effect of Homestead Value Cognition in the Aging of Family Population on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from the Homestead

The regression results are shown in Table 4. In Model 3 the aging rate of the family population has a significant positive impact on the farmers’ cognition of the value of homestead security and the coefficient = 0.372. That is, the higher the aging rate of the family population, the deeper the cognition of the value of homestead security. In Model 5, the farmers’ cognition of homestead security value has a significant negative impact on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead and the coefficient = −0.275. That is, the deeper the cognition of farmers’ security value, the weaker their willingness to withdraw from the homestead. The coefficients and are significant, indicating that the security value cognition plays a mediating role and Hypothesis 3 is verified. At the same time, the direct effect is significant and the coefficient = 2.170, but its symbol is opposite to . Explaining the results according to the masking effect, the proportion of the effect is calculated to be 4.71%. The cognition of farmers’ security value significantly reduces the willingness of farmers to withdraw from the homestead with regard to family population aging rate and willingness to withdraw.

In Model 4, the impact of family population aging rate on farmers’ cognition of homestead asset value is not significant and the coefficient = −0.224. In Model 6, the direct effect is significant and the coefficient = 2.086. The influence coefficient of asset value cognition on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead is 0.077, which is not significant. In summary, it can be seen that Hypothesis 4 is not established, indicating that the aging rate of the family population does not affect the willingness of farmers to withdraw from their homesteads through their cognition of the value of homestead assets.

4.2.2. The Mediating Effect of Homestead Value Cognition in the Aging of Family Population on Farmers’ Homestead Withdrawal Compensation Preference

The regression results are shown in Table 5. In Model 7, the aging rate of the family population has a significant positive impact on the value cognition of the farmers’ homestead security and the coefficient = 0.433. That is, in the families with the willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, the higher the level of the aging rate of the family population, the deeper the farmers’ cognition of the value of homestead security. In Model 9, the direct effect is significant and the coefficient = −1.034, which indicates that the family population aging rate has a significant negative impact on the compensation preference of farmers’ homestead withdrawal. That is, in the families with the willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, the higher the level of family population aging, the more farmers tend to choose the non-monetary compensation method. The influence of security value cognition on the compensation preference of farmers’ homestead withdrawal is not significant and the coefficient = 0.242. The influence coefficient is significant and is not significant. According to the mediating effect test process provided by Wen et al. [65], a Bootstrap method is needed to test . The indirect effect is not significant, that is, the cognition of security value does not play a mediating role, indicating that the aging of the family population does not affect the compensation preference of homestead withdrawal through the cognition of farmers’ security value, and Hypothesis 5 is not established.

In Model 8,the influence of the aging rate of the family population on the cognition of the value of farmers’ homestead assets is significant and the coefficient = −0.433. This shows that the aging rate of the family population has a significant negative impact on the cognition of the value of farmers’ homestead assets. That is, in the families with the willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, the higher the aging level of the family population, the shallower the cognition of the value of farmers’ homestead assets. In Model 10, the influence of asset value cognition on farmers’ homestead withdrawal compensation preference is significant and the coefficient = 0.288. This shows that farmers’ asset value cognition has a significant positive impact on farmers’ homestead withdrawal compensation preference, that is, the deeper the farmers’ asset value cognition is, the more likely they are to choose the monetary compensation method. The coefficients and are significant, indicating that asset value cognition plays a mediating role and Hypothesis 6 is verified. At the same time, the direct effect is not significant and the coefficient = −0.779. Therefore, the value cognition of farmers’ homestead assets plays a complete mediating role in the influence of family population aging on the compensation preference of farmers’ homestead exit. The mediating effect is calculated to be 16.01%. An aging family population enhances the willingness of farmers to choose non-monetary compensation by inhibiting the value cognition of farmers’ assets. The results of this study also confirm the previous theoretical analysis, that is, rural households with a large proportion of elderly members have a heavy burden of old-age care, and old-age security is in the primary position. Therefore, the shallower the farmers’ awareness of the value of homestead assets, the more inclined they are to choose non-monetary compensation methods that can provide basic living security.

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Replace the Core Explanatory Variable

With the advancement of medical standards, the average life expectancy has gradually increased, so the aging age limit will be further tightened. In this section, the proportion of the elderly population over 65 years old is used as the basis for the division of population aging, to verify the impact of family population aging on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead and their compensation preferences. Based on this, Logit regression and mediating effect are used for regression analysis. The empirical results are as shown in Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8. The results are basically consistent with the results of the population aging model based on the standard statistic of 60 years old, indicating that the stability of the model results is good.

Table 6.

Regression results of the total effect of family population aging on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead and compensation preference.

Table 7.

Regression results of the mediating effect mechanism of farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead.

Table 8.

Regression results of the mediating effect mechanism of farmers’ homestead withdrawal compensation preference.

4.3.2. Replacement Model

Since the willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and the compensation preference in this study are two-category variables, the core explanatory variable and control variables are kept unchanged, and the Logit model is replaced with the Probit model for regression analysis to further test the robustness of the model. According to the analysis, the regression results are consistent with the above results in terms of significance and coefficient symbol, which verifies the reliability of the above conclusions. In view of the limitation of space, it is not repeated here.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Existing Studies on Homesteads

The aging of the population has become an inexorable trend in societal development. In the face of rapidly accelerating urbanization and the increasingly severe aging of the rural population, exploring how the aging of the family population affects farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and their compensation preferences is crucial. Such an exploration will help the efficient use of homesteads and promote rural revitalization. This paper empirically analyzes the impact of rural family population aging on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and their preference for withdrawal compensation and the mechanism of homestead value cognition. Based on our test results, it was observed that aging in rural families significantly increased the farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation. Interestingly, this finding contradicts the results of research by Sun et al. [51]. We hypothesize that the possible reason for this discrepancy is that, with economic development and improvements in living standards, the elderly’s attitude towards their homesteads has evolved. Older farmers often find it difficult to carry out high-intensity agricultural labor, so even the elderly with local support are gradually inclined to withdraw from the homestead and choose to live in cities or towns with a higher quality of life. In general, there is a complex mechanism linking the aging of the family population with farmers’ willingness to withdraw from their homesteads. Understanding this mechanism requires a multifaceted approach that takes into account diverse influencing factors. In terms of compensation preference, we found that the greater the aging of the rural family population, the more inclined they are to opt for non-monetary compensation. This is similar to the findings of Wang et al. [56], who suggest that older farmers are more willing to accept resettlement as a form of compensation. Although we conducted separate studies on families and individuals, both of them reveal that the elderly and young people have different life needs and expectations, reflecting the significance of life security for the elderly population. With regard to mediating effect analysis, the method we used is consistent with that of Xie et al. [42]. Both studies employ the causal step method proposed by Baron and Kenny [66], which is effective for testing mediating effects. Unlike Shi et al. [6], who concentrates on the direct impact of farmers’ policy cognition on their willingness to withdraw from homesteads, we integrate cognitive psychology theory into our mediating effect analysis. This allows us to reveal both the role of farmers’ value cognition of homesteads as a mediator and the underlying psychological mechanisms affecting their withdrawal willingness and compensation preferences. It can be seen that farmers’ cognition of homestead value will have a certain degree of influence on their willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and compensation preference, which will provide important enlightenment for the formulation of homestead withdrawal policy.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the research findings, considering the increasingly aging rural population, this paper proposes the following policy recommendations to enhance farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation: (1) Differentiated compensation policies for homesteads should be devised, aligning with the age structure of farmers’ families. A key aspect of this should be developing and improving the social old-age security system for families that withdraw from their homesteads. Having a well-structured security system is crucial to encouraging farmers’ compensated homestead withdrawal. Policies must prioritize farmers’ interests, ensuring basic security for their housing and economic conditions. It is crucial to acknowledge that highly aged rural families pay greater attention to the security value of homesteads. Thus, public service systems like pensions and healthcare should be further enhanced, improving the quality of life and retirement benefits of the elderly. The provision of diverse employment conditions for farmers withdrawing from homesteads should be promoted to stimulate their employment and income, reducing their pension burdens. The legitimate land rights of urban-settled farmers should be protected, encouraging lawful, voluntary homestead transfers. At present, the majority of Chinese farmers do not have a high-level social security system. Therefore, the current rural homestead reform should not be hasty. (2) Circulation of information resources should be strengthened to guide farmers towards reasonable cognition of homestead value. Relevant departments should routinely organize village officials to explain homestead withdrawal policies to farmers and use the Internet to publicize successful homestead withdrawal cases, helping farmers make more rational decisions. Additionally, establishing and perfecting the mechanisms and systems of compensated homestead withdrawal is a significant prerequisite for promoting such withdrawals. Hence, the government should formulate a stable and legally effective mechanism for compensated homestead withdrawal, standardize transparency in farmers’ participation in the withdrawal process, and prevent conflicts of interest and withdrawal concerns due to policy changes, thereby enhancing the efficiency of compensated homestead withdrawal. (3) In designing the homestead withdrawal compensation scheme, the combination of non-monetary and monetary compensations should be considered, catering to farmers’ diverse needs. The diversity and complexity of different farmers’ homesteads and variations in family economic conditions should be recognized. Compensation methods and standards that meet the actual needs of heterogeneous farmers should be established. Throughout the compensated homestead withdrawal process, farmers’ interests should be effectively protected, solving the living needs and development needs of farmers after they withdraw from the homestead, and ensuring housing, livelihood sources, and old-age security for those who withdraw from their homesteads.

5.3. Research Contributions and Limitations

Under the background of population aging, this paper delves into the impact of family population aging on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation and their compensation preference. This paper extends the existing research on the withdrawal with compensation of farmers’ homesteads and introduces a novel perspective on compensation related to farmers’ homestead withdrawal. Additionally, it enriches the literature in the field of population aging. While offering valuable insights to the academic realm, it serves as a crucial reference in motivating farmers to withdraw from their homesteads, aiding the development of rural revitalization policies, and crafting a social security system tailored for the elderly. A detailed exploration of the various modes and preferences concerning withdrawal compensation reflects the real needs and expectations of farmers in the face of aging challenges, which helps to ensure that policies and measures are more practical and humane. Internationally, in the context of an aging population around the world, this paper not only provides a reference for China, but also provides unique insights and experiences for other developing countries or countries with similar situations. However, it is worth pointing that our sample is mainly from Shenyang City, Liaoning Province, China, which means that the sample area is relatively single. In the future, with the gradual deepening of the reform of China ‘s homestead system, the team will further expand the research scope and sample size, consider incorporating samples from other regions of China to test the results of this study, and analyze the regional differences in farmers’ willingness to withdraw from rural homesteads. Simultaneously, the team will investigate other factors that might influence the connection between population aging and farmers’ willingness to withdraw from homesteads, delving deeper into the underlying dynamics between them.

6. Conclusions

Based on the survey data of 403 rural families in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, China, this paper employs the binary Logit model and the mediating effect model to empirically analyze the impact and mechanism of rural family aging on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, and their compensation preference. The study’s findings are as follows: (1) The aging of the family population significantly increases farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation. Furthermore, the greater the family population’s aging, the more inclined farmers are to opt for non-monetary compensation methods. (2) With regard to family population aging to promoting withdrawal willingness from the homestead with compensation, farmers’ cognition of the security value of the homestead presents a masking effect of 4.71%. This effect indirectly suppresses farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead with compensation, whereas the farmers’ cognition of the asset value of the homestead does not have a mediating effect. (3) With regard to family population aging towards promoting farmers’ non-monetary compensation choices for the homestead, farmers’ cognition of the value of homestead assets plays a fully mediating role with a magnitude of 16.01%. This significantly boosts farmers’ inclination to choose non-monetary compensation, yet there is no mediating effect on the farmers’ cognition of the homestead’s security value. According to the characteristics of different farmer groups, measures such as cultivating farmers’ reasonable cognition of the value of the homestead and formulating differentiated compensation policies for homestead withdrawal can be taken to enhance farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the homestead.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G.; data curation, Y.H.; funding acquisition, H.G.; methodology, H.G. and Y.H.; project administration, H.G.; resources, F.Q.; software, Y.H. and Y.W.; supervision, H.G.; validation, Y.H.; writing—original draft, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, H.G., Y.H., and B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Research Foundation of Liaoning Province (Grant No. WSNZK202002), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant Nos 2020T130433 and 2018M631824) and the Liaoning Province Social Science Foundation (Grant No. L19CGL009).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ren, C.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Diao, Y.; Shen, S.; Reis, S.; Li, W.; Xu, J.; Gu, B. Ageing Threatens Sustainability of Smallholder Farming in China. Nature 2023, 616, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H. Trends of Population Aging in China and the World as a Whole. Sci. Res. Aging 2021, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- World Population Prospects 2019. Population Division. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/news/world-population-prospects-2019-0 (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Chen, Y.; Ni, X.; Liang, Y. The Influence of External Environment Factors on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: Evidence from Wuhan and Suizhou City in Central China. Land 2022, 11, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World’s Cities 2022 Report by UN-HABITAT. Available online: https://news.un.org/zh/story/2022/06/1105282 (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Shi, R.; Hou, L.; Jia, B.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X.; Hou, X. Effect of Policy Cognition on the Intention of Villagers’ Withdrawal from Rural Homesteads. Land 2022, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Jiang, J.; Yu, C.; Rodenbiker, J.; Jiang, Y. The Endowment Effect Accompanying Villagers’ Withdrawal from Rural Homesteads: Field Evidence from Chengdu, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xu, A.; Liu, L.; Deng, O.; Zeng, M.; Ling, J.; Wei, Y. Understanding Rural Housing Abandonment in China’s Rapid Urbanization. Habitat Int. 2017, 67, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Tian, Y.; Zou, Y. A Novel Framework for Rural Homestead Land Transfer under Collective Ownership in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shi, H.; Wang, M.; Feng, Z. Different Resource Endowment, Rural Housing Land Registry and Rural Housing Land Circulation: A Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Observations from Hubei. Chin. Rural Econ. 2018, 05, 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. Regional Difference and Influencing Factors of Population Aging in China. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. Sci. Ed. 2017, 6, 94–102+151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Report of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: From the Seventh Census Data, the Five Characteristics of China’s Population Aging. Available online: https://hbsjzxh.hebtu.edu.cn/a/2021/12/30/5C53D8497A9B48889B43BF0DBCB74101.html (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Liu, Q. On price forming mechanism for peasants’ homestead-land-use-right exit. China Popul. Environ. 2017, 27, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Ma, F. Spatial distribution and trends of the aging of population in Guangzhou. Geogr. Res. 2007, 26, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D.E.; Chatterji, S.; Kowal, P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; McKee, M.; Rechel, B.; Rosenberg, L.; Smith, J.P. Macroeconomic Implications of Population Ageing and Selected Policy Responses. Lancet 2015, 385, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Lv, L.; Failler, P. The Impact of Population Aging on Economic Growth: A Case Study on China. AIMS Math. 2023, 8, 10468–10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, H. Exploring the Spatial-Temporal Distribution and Evolution of Population Aging and Social-Economic Indicators in China. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.A.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Moran, A.E.; Barber, R.; Nguyen, G.; Feigin, V.L.; Naghavi, M.; Mensah, G.A.; Murray, C.J.L. Demographic and Epidemiologic Drivers of Global Cardiovascular Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, M.; Devi, W.P.; McGonigle, I. Generational Medicine in Singapore: A National Biobank for a Greying Nation. East Asian Sci. Technol. Soc. Int. J. 2023, 17, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlich, J.; Orlu, M.; Mair, A.; Stegemann, S.; Van Riet-Nales, D. Age-Related Medicine. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall, T.M.; Gallo, P.D.; Chakrabarti, R.; West, T.; Semilla, A.P.; Storm, M.V. An Aging Population and Growing Disease Burden Will Require ALarge And Specialized Health Care Workforce By 2025. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 2013–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, A.E.; Gomes, B.; Etkind, S.N.; Verne, J.; Murtagh, F.E.; Evans, C.J.; Higginson, I.J. What Is the Impact of Population Ageing on the Future Provision of End-of-Life Care? Population-Based Projections of Place of Death. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, F.; Furuse, J. Treatments for Elderly Cancer Patients and Reforms to Social Security Systems in Japan. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 27, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, N.; Brown, D.L. Rural Ageing in the United States: Trends and Contexts. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Global Population Ageing from 1960 to 2017. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Han, H. Spatiotemporal Dynamic Characteristics and Causes of China’s Population Aging from 2000 to 2020. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.; Gao, Y. Influencing Factors Analysis and Development Trend Prediction of Population Aging in Wuhan Based on TTCCA and MLRA-ARIMA. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 5533–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Du, S.; Fu, Z. The Impact of Rural Population Aging on Farmers’ Cleaner Production Behavior: Evidence from Five Provinces of the North China Plain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Liang, H.; Shi, W. Rural Population Aging, Capital Deepening, and Agricultural Labor Productivity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skog, K.L.; Steinnes, M. How Do Centrality, Population Growth and Urban Sprawl Impact Farmland Conversion in Norway? Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowski-Lindsay, M.; Butler, B.J.; Kittredge, D.B. The Future of Family Forests in the USA: Near-Term Intentions to Sell or Transfer. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keswell, M.; Carter, M.R. Poverty and Land Redistribution. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Laliberté, L.; Swallow, B.; Jeffrey, S. Impacts of Fragmentation and Neighbor Influences on Farmland Conversion: A Case Study of the Edmonton-Calgary Corridor, Canada. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Peng, W.; Huang, X.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q. Homestead Management in China from the “Separation of Two Rights” to the “Separation of Three Rights”: Visualization and Analysis of Hot Topics and Trends by Mapping Knowledge Domains of Academic Papers in China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Ye, C.; Xun, H.; Han, L.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, L. Promoting Common Prosperity by Tripartite Entitlement System of Rural ResidentialLand: A Case Study of Xiangshan County, Zhejiang Province. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Su, K.; Wu, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, H.; Yang, Q. The Functional Evolution and Dynamic Mechanism of Rural Homesteads under the Background of Socioeconomic Transition: An Empirical Study on Macro- and Microscales in China. Land 2022, 11, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Fu, C.; Kong, S.; Du, J.; Li, W. Citizenship Ability, Homestead Utility, and Rural Homestead Transfer of “Amphibious” Farmers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Chen, J.; Gao, J.; Li, M.; Wang, J. What Role(s) Do Village Committees Play in the Withdrawal from Rural Homesteads? Evidence from Sichuan Province in Western China. Land 2020, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, L. Does Cognition Matter? Applying the Push-pull-mooring Model to Chinese Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 2355–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Vanclay, F.; Yu, J. Post-Resettlement Support Policies, Psychological Factors, and Farmers’ Homestead Exit Intention and Behavior. Land 2022, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, J.; Lo, K.; Huang, S. Withdrawal Intention of Farmers from Vacant Rural Homesteads and Its Influencing Mechanism in Northeast China: A Case Study of Jilin Province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ke, S.; Li, X. Psychological Resilience and Farmers’ Homestead Withdrawal: Evidence from Traditional Agricultural Regions in China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Jiang, C.; Meng, L. Leaving the Homestead: Examining the Role of Relative Deprivation, Social Trust, and Urban Integration among Rural Farmers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Yan, Z.; Peng, D.; Liang, H. Research on the Practice and Optimization of Rural Homestead Exiting. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2018, 57, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Jiang, G.; Ma, W.; Zhou, D.; Qu, Y.; Yang, Y. Social Security or Profitability? Understanding Multifunction of Rural Housing Land from Farmers’ Needs: Spatial Differentiation and Formation Mechanism—Based on a Survey of 613 Typical Farmers in Pinggu District. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Yuan, L.; Lu, M. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Farmers’ Homestead Revitalization Intention from the Perspective of Social Capital. Land 2023, 12, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Z. Influencing Factors of Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: A Survey in Zhejiang, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Jiang, Q. Land Arrangements for Rural–Urban Migrant Workers in China: Findings from Jiangsu Province. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Liu, L. Ownership Consciousness, Resource Endowment and Homestead Withdrawal Intention. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 03, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, S.; He, J. Risk Expectation, Social Network and Farmers’ Behavior of Rural Residential Land Exit: Based on 626 Rural Households’ Samples in Jinzhai County, Anhui Province. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Zhao, K.; He, J. The Rural Population Aging, Social Trust and Farmers’ Behavior of Quitting Rural Residential Land: 614 Farmers’ Samples in Jinzhai County, Anhui Province. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. Sci. Ed. 2019, 5, 137–145+173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yu, C.; Jiang, J.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Farmer Differentiation, Generational Differences and Farmers’ Behaviors to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: Evidence from Chengdu, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 103, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C. Influence of Peasants’ Cognition of Homestead’s Property Rights on Their Willingness to Return Rural Homestead An Empirical Analysis Based on Survey Data of 1413 Rural Households in 6 Counties of Anhui Province. China Rural Surv. 2013, 1, 21–33+90–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Yuan, K.; Chen, Y.; Mei, Y.; Wang, Z. Effect of farmer differentiation and generational differences on their willingness to exit rural residential land: Analysis of intermediary effect based on the cognition of the homestead value. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 1680–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, B.; Zheng, W. Homeland Attachment, Urban Integration and Rural-urban Migrants’ Willingness to Withdraw Rural Residential Land: A Survey in Xiamen, Fujian Province. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Luo, D. Farmers’ Diverse Willingness to Accept Rural Residential Land Exit and Its Impact Factors. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Compensation preference and heterogeneity sources of homestead withdrawal of farming households: Based on choice experiment method. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Lin, M. The influence of farmers’ heterogeneity characteristics on the preference of homestead exit compensation: Based on the survey data of Dazu and Fuling. Rural Econ. 2019, 2, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Influence of farming household interactions on rural homestead withdrawal compensation from the perspective of social network. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 1440–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, X. The impacts of functional cognition on farmers’ compensation expectation of transferring rural residential land: From the perspective of family life cycle. Res. Agric. Mod. 2021, 42, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Connotation, Value and Evolution: Review of and Reflections on Aging Rate. Sci. Res. Aging 2021, 9, 15–22+44. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Song, G.; Sun, X. Does Labor Migration Affect Rural Land Transfer? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, S.; Yuan, S.; Shen, T.; Tang, Y. Multi-functional Recognition and Spatial Differentiation of Rural Residential Land: A Case of Typical Rural Area Analysis in Jiaxing, Yiwu and Taishun. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, S. Spatio-temporal Pattern and Mechanism of Coordinated Development of “Population–Land–Industry–Money” in Rural Areas of Three Provinces in Northeast China. Growth Chang 2022, 53, 1333–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).