Abstract

Comparisons of spatial planning systems still require in-depth reflection, especially in Central and Eastern European countries. This article compares national (central) government approaches to spatial planning in Belarus, Ukraine and Poland, answering the following research questions: (1) How are spatial planning issues regulated nationally? Which topics do laws focus on? What values and objectives are laws particularly emphasizing? (2) Are there any central/national strategic documents dealing with spatial planning, and which spatial issues do they address mostly? The article covers two key issues: comparing national approaches to spatial planning systems and comparing spatial planning issues in the three countries. We focus on statutory approaches and those contained in central-level strategic acts. In each country, spatial planning issues are covered by numerous laws, generating confusion when interpreting individual provisions. Our study makes an important, innovative contribution to the academic discussion by proposing a way of comparing and analyzing approaches of national authorities to spatial planning.

1. Introduction

The assessment of spatial planning systems requires undertaking varied activities. One of them is the comparison of the solutions adopted in individual countries. This task is a difficult one, however. It requires taking into consideration numerous occurring differences concerning, among others, the legal tradition, the planning tradition, the country’s system, the size of the country or the planning culture [1,2,3]. These premises can be further expanded. They constitute serious barriers for comparisons. Nevertheless, the simple fact that barriers exist cannot account for the complete ceasing of conducting comparisons. The following trends of comparisons can be designated:

- Cross-sectional comparisons of particular spatial planning instruments or individual issues in a larger number of countries [4];

- Synthetic descriptions of selected issues in a larger number of countries, without thorough mutual comparison of particular solutions [5];

- Thorough comparative analyses regarding two or three countries [6,7,8].

This article belongs to the third type of publication. The objective of this research is to compare national (central) approaches of public authorities to spatial planning in Belarus, Ukraine and Poland. By accomplishing this goal, our study attempts to make a contribution to the planning theory by addressing national planning systems and, in a broader sense, to provide further evidence on the relationship between planning and governance or centralization. The following research questions were formulated:

- How do national acts regulate spatial planning issues? What matters do they focus on? What values and objectives are particularly emphasized in the acts?

- Do strategic documents regarding spatial planning occur at the central/national level? If so, what spatial issues do they concern to the greatest extent?

A comparison of national approaches to spatial planning in neighboring, but at the same time different in some respects, countries is of significant value. In addition to comparing specific solutions and their possible translation into practice, the proposed research questions and objectives can also be linked to other issues. Conducting the analyses in question connects to the broader debate on determining the optimal relationship between central and local levels in spatial planning [9,10,11,12]. Against this background, Belarus is an example of a system in which the role of central government is also crucial in planning. The comparison is also related to discussing the optimal relationship between strategic and regulatory spatial planning [13,14,15]. Especially in the systems of Central and Eastern European countries, there are problems in combining the two levels. Such a merger seems necessary in view of the increasingly serious challenges faced by spatial planning. After all, spatial planning cannot be seen simply as defining development guidelines. It is also the spatial planning instruments that should contain an adequate response to climate challenges [16] or challenges of redefining post-pandemic urban policies [17,18,19,20]. However, in order to be able to adequately address the issues identified, it seems necessary to develop an appropriate approach at a national level. This process includes both the statutory and strategic levels. The indicated countries are good examples of systems with a great deal of barriers and neglect from this perspective.

The article covers two key issues: the comparison of national-level approaches to the spatial planning system and comparisons of spatial planning in three countries of Central-East Europe. The authors focus on the institutional perspective. This means that (apart from the mere identification of countries and consideration of their key characteristics), there is much less consideration of other determinants in the article. Instead, the analysis from an institutional perspective and related approach of national authorities to spatial planning issues is crucial. Regarding the former issue, it should be emphasized that the national level of planning determines the scope and quality of planning at the regional and local level [21,22,23]. Although (in most countries) the local level is technically the most important from the perspective of spatial planning, the framework of the functioning of the public authorities and (largely) strategic documents are shaped at the national level [24]. This description also reflects the relations between central and local authorities (in many cases, territorial self-government units). Two tasks of the national authorities can be designated. The first one is to provide a relevant legal basis [25]. This task is a difficult one. Spatial planning law should offer solutions to a number of varied interdisciplinary problems [26,27,28]. This law should address both the developed vision of the functioning of the entire spatial planning system, as well as its key objectives and values, as well as the method of implementation of such values [29,30]. This remark entails both the relevant selection of the content of acts and the number of acts regarding spatial planning. There is a clear lack of such coverage in the literature, especially from a comparative perspective. It is possible to identify publications in which authors focus on legal solutions or, for example, individual local spatial planning instruments. However, a more universal analysis of national legislators’ approaches to spatial planning issues is lacking. For this reason, it seems important and necessary to try to make comparisons between the legislators’ approaches to spatial planning in different countries. The comparison of this approach (and not only of the content of the legislation itself) should be considered very important from the perspective of further scientific discussion.

The second task related to spatial planning at the national level is equally important. A strategic document at the national level should determine key directions of spatial planning [15,31]. This task may cover varied activities: the designation of areas requiring special protection, the designation of key investments (particularly public investments), the determination of key challenges and problems perceived from the national perspective, as well as the introduction of certain guidelines regarding the rules of conducting spatial policy [32,33,34]. Individual objectives can be obviously implemented in particular national orders in varying scopes [35,36]. Nonetheless, the role of spatial planning at the national level undoubtedly is and should be important. This role requires a national-level spatial planning act adequate to meet the aforementioned needs. Such an act is usually a manifestation of strategic spatial planning. The act provides the basis for regional and local spatial planning instruments, as well as the regulatory ones [37]. The designated objectives should also be coherent with the objectives and values stipulated in the act on spatial planning. The literature also lacks a compilation and comparison of indicated documents. This gap needs to be filled; it is not only related to the ocean of practical solutions, but it also includes a broad assessment of how public authorities respond to spatial planning challenges. This will clarify the role (and strength) of the institutional sphere in spatial planning. The literature clearly indicates the need for an analysis of these issues [38]. A comparative analysis of national strategic spatial planning documents is also an important research task.

As mentioned above, individual countries face serious divergences and problems [39,40,41]. Acts regarding spatial planning frequently determine the legal order incorrectly or inadequately to the needs. Strategic documents also show varied levels and are often largely irrelevant for lower levels of planning. This situation aggravates numerous problems regarding spatial planning systems existing in individual countries. Countries similar to one another in certain terms and differing in others constitute particularly interesting material for comparisons. These criteria are met by Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland.

In Belarus, as a post-Soviet country, the change in the approach to spatial planning at the national level reflects changes in strategic social and economic priorities. In the second half of the twentieth century, the main focus was on the distribution of industrial enterprises and productive forces, paying particular attention to decentralization and regional development [42]. The Belarusian literature postulates the adaptation of current spatial planning documentation to the challenges of integrated development planning [43,44]. It is also necessary to align the contents of selected documents linked to the sphere of development policy [44,45]. Another important challenge is the complementarity of long-range territorial planning and socio-economic forecasts of the municipality [43,44]. By contrast, the Belarusian literature lacks in-depth reflections on other topics, including those concerning the national level of spatial planning.

There is a slightly more developed academic discussion on spatial planning in Ukraine. Interest in the topic increased in 2010, with Ukraine’s strategic course towards Euro-integration. Another factor activating this type of research in Ukraine is the administrative-territorial reform in the country in 2020. Among the studies of recent years, it is necessary to highlight the scientific article dedicated to the resumption of the general scheme of spatial planning of Ukraine [46] and the analysis of the results of the introduction of regional development programs in Ukraine [47]. From 2022 onwards, various spatial planning issues in the context of Russia’s armed aggression in Ukraine and the post-war reconstruction of the country have become the main focus of research [48]. According to researchers from Ukraine, the biggest problem of spatial planning in the country over the past decades is the disorganization and lack of conformity of spatial planning legislation. Diverse concepts are emerging to describe the optimal direction for changing the legislation [49,50]. Another problem is the lack of a sufficient linkage between spatial and strategic development planning [50,51]. A significant improvement in the strategic spatial planning act at the national level is also called for [50].

From Poland’s perspective, on the other hand, the scientific discussion on the spatial planning system is (if only in quantitative terms) the most developed. In the sphere concerning the application of spatial planning instruments, serious dysfunctions are noted in the Polish literature. First of all, it should be pointed out that there is great spatial chaos, which contributes to generating enormous costs for the users of the country’s space [52]. Another factor is the weakness of legal solutions, which do not translate into the protection of spatial order at the local level [53]. Instead, there is an overly broad role for individual property owners in the spatial planning system [54,55]. There are also serious limitations to integrated development planning, including a lack of compatibility between different types of spatial planning instruments [56].

From the perspective of the three countries studied, there is a significant research gap in the comparative analysis of spatial planning at the national level. Undertaking such analyses is also necessary because of the problems and barriers to spatial planning diagnosed in the literature (and, in some cases, because of the lack of broader coverage of the national spatial planning topic in the literature). It should be added, moreover, that some common constraints and barriers exist across the entire group of CEE countries. Newman and Thornley [3] observed a certain distinctiveness of the group of countries of Central-East Europe, but their diagnosis based on the state of these nations in the 1990s did not allow for specifying detailed features of the designated group. Barriers in performing such classification are also observed in contemporary times [57]. For part of the aforementioned countries, the common context is undoubtedly shaped by the accession to the European Union [58]. In an earlier publication [59], the authors designated three common features of countries of Central-East Europe, determined, on the one hand, by the communist tradition and, on the other hand, by certain institutional limitations. They are as follows:

- Specific approaches to the market and above-standard spatial planning conflicts result in the lack of a common response to planning challenges adequate to the needs;

- Special emphasis on the entitlements of property owners in the spatial planning system;

- Incoherent responses to intensive urbanization (including suburbanization).

Despite their neighboring locations, Belarus, Ukraine and Poland are also different in other aspects. The administrative system in Belarus determines the direction of spatial planning (with local spatial policy authorities having a limited role). Ukraine is in a state of war, which, on the one hand, complicates thorough work on improving the spatial planning system and, on the other hand, somewhat redirects the debate in the scope to the future rebuilding of the country. Poland is a member state of the European Union, although its current spatial planning system is among the most broadly criticized ones [60].

Also, from the perspective of the indicated countries, it seems very relevant and necessary to consider the role of individual spatial planning instruments. This need exists because it is the spatial planning instruments that can ensure the implementation of individual objectives identified in individual spatial planning systems [61,62,63]. Despite the systemic, legal or cultural differences between countries, it seems possible to identify important analogies. Of particular relevance are the analogies concerning individual instruments of spatial planning, including precisely the implementation of indicated objectives by these instruments [64]. In individual countries, despite their differences, there are very often similar problems and barriers [65,66,67,68]. However, in order to diagnose them correctly, it seems necessary to compare selected institutional conditions [69]. The patterns indicated do not only apply to spatial planning instruments at the local and regional level. They also apply to spatial planning instruments at the national level.

It appears that the comparison of national approaches to spatial planning in these countries are, on the one hand, similar, but in many aspects, different countries will constitute a very interesting and needed research task. The aforementioned comparisons (regarding the national level of spatial planning) in the case of the analyzed countries have been addressed in a limited scope [70]. They can therefore be considered innovative. This issue requires in-depth analysis. A detailed review of the legislator’s approach to spatial planning and a review of the content of strategic spatial planning acts at the national level represent an answer to serious and necessary research challenges. Other contributions of this paper are as follows:

- The designation of features of spatial planning systems at the national level eligible for thorough comparisons;

- The determination of the differences between countries with similar traditions and approximate geographic locations.

Both of the issues also have a broader, universal dimension. The article’s contribution to the scientific discussion is to propose a way of comparing the institutional approaches of national-level public authorities to spatial planning issues.

The section presenting the applied methods describes the undertaken research activities in detail. Further tables included in results present key features extracted from the perspective of each of the analyzed countries regarding national spatial planning. The features are then analyzed in detail in the discussion.

2. Characteristics of the Comparisons of the Studied Countries

This section contains the following elements:

- The provision of a broader explanation of the background of the research conducted (as part of the publication cycle);

- Identification of the key issues taken into account when comparing the three countries studied;

- A description of the steps taken to produce comparable results;

- An explanation of key concepts (as a point of reference for further comparisons).

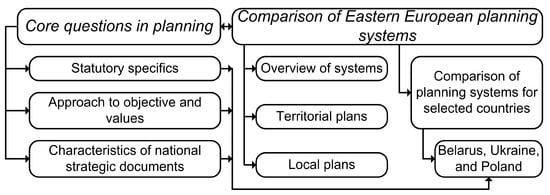

The article constitutes a part of a broader cycle of comparative studies regarding spatial planning systems in Central-East Europe [59]. The first stage involved the comparison of the form of the functioning of local spatial plans in a larger number of analyzed countries. The comparisons were also accompanied by an attempt to present broader features of the compared systems, including key problems and challenges related to their functioning. It should be emphasized that the comparison of solutions does not simply involve a comparison of individual provisions from the selected countries. Broader system analyses involving comparisons of particular solutions are necessary, taking into consideration the specifics and traditions of particular countries, as well as in terms of the applied terminologies. Figure 1 presents an outline of the broader research framework, including the methodology used in our comparative approaches.

Figure 1.

Methodological and research framework.

The analysis of first comparisons showed that the three analyzed countries, namely, Belarus, Ukraine and Poland, deserve a separate, thorough comparison of their national approaches to spatial planning. In this regard, Figure 2 shows the geographical coverage of our study, distinguishing the continuum of the three countries analyzed from the others. Due to the above, for particular authors—representatives of the analyzed countries—a more comprehensive survey was prepared. In this way, defining the following was attempted for each country:

Figure 2.

Countries surveyed. The ones included in our study are colored (purple: Poland; green: Belarus; blue: Ukraine), distinguishing them from the neighboring ones.

- The statutory specifics regarding spatial planning (determination of the content of the “main” act concerning spatial planning, and the scope of including spatial planning issues in other acts);

- Approach to the objectives and values in acts regarding spatial planning;

- Characteristics of national strategic documents regarding spatial planning (alternatively, other national strategic documents that also concern spatial planning);

- The degree of coherence between the acts and strategic documents;

- The degree of implementation of practical assumptions stipulated in acts and strategic documents.

The provided answers were analyzed. The next round covered more detailed questions for solving the occurring divergences. On the basis of the issues developed and in-depth consultations, it was possible to tabulate individual topics. They have been arranged in such a way that, on the one hand, the correct characterization of national systems of spatial planning is maintained but, on the other hand, the characterization of all three countries is carried out in a similar way.

Regarding the study objectives, it should be emphasized that spatial planning is defined by the authors as the process of organizing a territory, land use, and the management of competing interests [4]. The authors note the discussion conducted in the literature on the subject regarding the approaches to understanding the term. Attention should be paid to the following issues for the purposes of the preparation of this article:

- The opinion represented by Healey [71] remains an important point of reference. He considered spatial planning as a set of management practices for the development and implementation of strategies, plans, policies, and projects, as well as for the regulation of the location, time, and form of development;

- The role of spatial planning is also to point to the preferred forms of spatial development and the integration of sectoral policies [72];

- Spatial planning constitutes a tool for balancing the needs of society, the economy, and the environment by providing an institutional and technical framework for the management of the territorial dimension of sustainable development [73].

Each of the analyzed countries has a precise approach to the national spatial planning system. It should be emphasized, however, that in addition to designating zones of a territory and the determination of the rules of their land use, spatial planning has considerably broader tasks. These tasks cover the development of the necessary concepts of the functional–spatial structure of the country, the integration of sectoral policies, as well as taking into consideration the needs and expectations of society.

The term “strategic documents” used in the article needs to be clarified. The term can be understood in different ways. However, in relation to our research objectives, in this article, strategic documents should be understood as strategic acts at the national level. These are all strategies or concepts (depending on the country) that have a strategic dimension. By contrast, we do not consider legal acts, including laws, as ‘documents’. As indicated, the specific of solutions in each country may vary. Nevertheless, in this paper, we analyze two types of strategic documents:

- Strategic documents directly related to spatial planning;

- Strategic documents of a more general nature.

The concepts indicated are applied in the next section of article.

To conclude this section, it can be said that achieving the research objective and answering the research questions are linked to important issues from a scientific perspective. At the same time, it must be emphasized that answering the research questions requires an interdisciplinary approach, comparing (in different countries) both the legislator’s approach and the strategic planning approach. The presented way of making comparisons is, in the authors’ view, adequate to the challenges posed.

3. Results

A detailed comparison of the three countries studied requires a synthetic characterization of the relationship between the central government and units of territorial self-government. This is crucial from the perspective of the article’s goals and research questions. Table 1 shows that the three countries studied are different in this respect. Among the selected countries, this difference is the most pronounced. Ukraine has attempted to develop relations between its central authority and territorial self-government units according to the model represented by the countries of Western Europe. Still, before the war, however, a key barrier was represented by technical legal issues related to doubling competences at different levels. In Poland, the developed system of territorial self-government units is theoretically maintained, although this country also faces issues regarding the division of competences between different levels of authority and centralization tendencies.

Table 1.

Relations of central government and self-government authorities in analyzed countries.

In each analyzed country, spatial planning is addressed by numerous acts (Table 2). The general pattern is as follows: one “main” act regarding spatial planning can be distinguished. Irrespective of the above, issues regarding spatial planning are also covered by other acts in more detail. Generally, however, issues of spatial planning being covered by many legal documents in a single system provokes terminological inconsistencies. This situation results from the following model of activity: in a situation of, e.g., the preparation of an act on environmental protection, the legislator primarily considers environmental terminology (different to that related to spatial planning). Finally, the description of the issue of spatial planning in the environmental act differs from that in the “main” spatial planning act (or acts). This kind of problem is the most pronounced in Belarus. In all three countries, thorough integration of development planning is lacking. In Ukraine and Poland, certain preliminary activities in this scope have already been undertaken. They are, however, still insufficient. Also at the national level, the lack of integrated development poses a serious risk of discrepancies and inconsequence in spatial planning. This is reflected in the presented dispersal of the aspect of spatial planning at the level of national acts. Table 2 provides a reference to the first research question.

Table 2.

Key legal documents regarding spatial planning in the analyzed countries.

Table 3 includes two important elements of the “main” spatial planning acts in the analyzed countries. Firstly, the structure of the content of the acts is presented, and secondly, values cited in those acts are distinguished, constituting a point of reference for legal solutions in the scope of spatial planning. The indicated elements should be particularly taken into consideration in the analysis of national/statutory legal approaches of the majority of spatial planning systems.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the content of the “main” spatial planning acts in the analyzed countries.

In the case of Belarus, the analyzed act constitutes a certain form of an urban planning construction code. The code comprehensively covers spatial planning and construction law (related to the investment–construction process). Ukraine attempts to combine spatial planning with urban management in one legal document. Nonetheless, a more thorough analysis of the content of the act shows that also in this country, like in Belarus, the attempt involves including spatial planning law and construction law in one legal document. In Poland, the act focuses exclusively on issues regarding spatial planning, distinguishing individual levels of planning, as well as the case in which no actual spatial planning takes place (situations in which the spatial plan is replaced by administrative decisions). It is worth emphasizing that attempting to combine separate issues, as in the results from Table 2, does not actually integrate development planning. Despite the indicated similarities, in each of the countries, a different legal approach to spatial planning was proposed. Three variants were therefore designated:

- Combining spatial planning law and construction law provides coherence, particularly in the situation of considering spatial plans in a specific investment–construction process;

- Associating spatial planning with specific thematic areas (e.g., urban management) is a step in the right direction. This variant is, however, moderately effective in a situation when legislation does not offer a more comprehensive consequence in the scope of accenting a broader dimension and tasks of spatial planning and in the aspect of institutional inefficiency and doubling competences of various authorities;

- Limiting the “main” spatial planning act only to covering individual levels of planning, with no thorough reference to modern spatial planning challenges, is also insufficient and generates serious spatial problems.

The above can be particularly referred to the said acts addressing values concerning spatial planning. Doing so entails a specific dilemma. The legally described values/objectives should serve as a point of reference for the interpretation of individual provisions. Therefore, their inclusion in the act may be necessary. On the other hand, in the sphere of spatial planning, part of the values are difficult to reflect in the sphere of legal provisions. A good example is represented by values included in the Ukrainian act. In a more universal interpretation, “shaping an environment favorable for human life” can be associated with, e.g., the requirements of the public interest. Nonetheless, it is difficult to directly reflect such value in legal interpretation. The situation is similar in the case of some values expressed in the Polish act. This act particularly concerns spatial order. Nonetheless, Poland has attempted to broadly address the indicated values. The values are addressed in even more detail in the Belarusian act. The included values comprise numerous activities related to spatial planning. It is uncertain, however, whether the indicated values translate into any directions of interpretation of the provisions. Moreover, the choice of values appears relatively random. Three ways of addressing values in the acts can be designated here:

- Individual values, related to the issue of key importance from the perspective of the act;

- Attempts to synthetically present systemic values;

- More detailed characteristics of values subjectively chosen by the legislator, important from the perspective of the spatial planning system.

Table 3 provides a reference to the first research question.

Table 4 presents the characteristics of strategic documents at the central level directly concerning spatial planning. It should be emphasized that no such document currently exists in Poland (as a result of certain negligence on behalf of central authorities). “State Scheme of Comprehensive Territorial Organization of the Republic of Belarus” [78] and the Ukrainian document “General Scheme of Planning of the Territory of Ukraine” [79] are similar documents by content, i.e., they are of one type. However, the Ukrainian document was adopted back in 2002, so it is outdated and currently little used in practice. This document was supposed to cover the period up to 2020, but a new document has not been created so far, so the document in question is still in force on Ukrainian territory. The Belarusian document was adopted in 2011 for the period up to 2030 and is used much more on a Belarusian scale than the aforementioned document on the territory of Ukraine. The comparison of documents in Belarus and Ukraine should take into consideration that in the former case, the cited document constitutes a collection of specific guidelines for lower levels of authority. The Ukrainian document has a broader strategic dimension, although it also includes guidelines regarding the use of the territory. The aforementioned disparities in the analyzed countries confirm theses on the problematic character of approaching the objectives of strategic spatial planning at a national level. On the one hand, there is the risk of an excessively detailed approach (further limiting the authorities’ freedom of acting at a lower level). On the other hand, there is a risk of omitting the specified level of planning, which may increase chaos in the spatial planning system. Table 4 provides a reference to the second research question.

Table 4.

National strategic document regarding the sphere of spatial planning in the analyzed countries.

To confirm the importance of planning at the national level, we extracted from the analyzed documents key values from the perspective of spatial planning. In the cases of Belarus and Ukraine, these values were specified in a much better way in technical terms and were more synthetic than in legal documents (Table 3). The disparity between a statutory and strategic approach to the values, however, is evident.

Table 5 shows that the dimension of spatial planning is also included in other strategic documents at the central scale. In the case of Poland, this dimension, however, is included in an indirect way (confirming earlier observations concerning certain neglect of the issue of spatial planning at the central level in the Polish system). In Ukraine, the guidelines included in the cited document primarily refer to more technical issues, especially those concerning the quality of documentation in the scope of spatial planning. Nonetheless, postulates that are possible to relate to the broader integration of development policies can also be found in such an approach. Table 5 provides a reference to the second research question.

Table 5.

Dimension of spatial planning in other national strategic documents.

4. Discussion

Whereas the literature provides various comparisons of spatial planning systems, the novelty of our study consists of the comparison of institutional solutions existing at the national level in three different countries. There are, of course, many publications in the literature containing comparisons of spatial planning systems. Firstly, however, it is relatively rare to juxtapose national (spatial planning) solutions of EU countries with those of non-EU countries. These studies have shown the possibility and even validity of such comparisons. Secondly, numerous comparisons of other systems often mention the planning traditions of individual countries or the specificity of their legal solutions. It is much less common, however, to address these issues in more detail from the perspective of the statutory approach itself (including characteristics of selected laws and their content) and then present a critical analysis of strategic documents. Our study provides a summary of the issues identified using these approaches. The mutual reference of statutory (regulatory) solutions occurring at the national level and strategic solutions is also innovative. The authors developed a special method for conducting comparisons, also applicable to other countries.

Our findings lead to important conclusions that may cast a new light on the debate on comparing spatial planning systems. It is worth emphasizing that particularly in the countries of East-Central Europe, the quality of spatial planning largely depends on the position and relationship between the central authorities and territorial self-government units. Whereas in some countries from other parts of the world (e.g., South Australia and until recently some states of Mexico), centralized spatial planning is practiced, in the case of East-Central Europe, such a solution is not possible [29]. In these cases, centralization means limiting social participation and arbitrary planning decisions. On the other hand, handing over specific tasks to self-governments alone will also not be sufficient. Countries of East-Central Europe face numerous institutional problems related to spatial planning [59]. This finding is confirmed by the example of the three analyzed countries. The article presents (Table 2 and Table 3) the specifics of the statutory approaches to spatial planning in Belarus, Ukraine and Poland. In each of these countries, issues related to spatial planning are addressed in numerous acts, generating chaos in the interpretation of individual provisions. At the statutory level, an optimal approach to spatial planning in the “main” spatial planning act is attempted in different ways. This article designates three types of approaches (different in each country). Each case, however, raises certain reservations. Attempts to combine spatial planning law and construction law in one document excessively bring the role of spatial planning down to the technical–construction dimension. In such an approach, spatial planning becomes only a set of guidelines necessary to be considered in the construction process. This approach is present in Belarus. It should be emphasized that such an approach to spatial planning is obsolete. A broad discussion is currently conducted on ways to consider diverse challenges regarding adaptations to climate change in the scope of spatial planning [84,85] and particularly on ways of protecting green areas and promoting green infrastructure [86,87], guaranteed flexibility of land use, and efficient implementation of investments in the scope of renewable energy sources [26,88,89,90,91]. These challenges should be particularly addressed at the national level of spatial planning. The traditional approach to spatial planning provisions makes it difficult to consider such challenges. The challenges of climate change show how important and necessary it is to reflect on the expansion of spatial planning goals and targets. In each of the three countries studied, there are serious limitations in terms of the degree of implementing various climate goals. Nevertheless, the scientific literature recognizes these challenges. This is most extensively illustrated by studies on Poland. The best example is the issue of renewable energy sources. It was pointed out that the specific, dispersed settlement in Poland can be a hindrance to the implementation of larger renewable energy sources on the one hand but, on the other hand, a supporting factor for the production of micro-installations [92]. At the same time, the weakness of municipalities in terms of drafting spatial policies implementing renewable energy sources has been diagnosed [89], as well as problems (also concerning the judicial perspective) related to resolving spatial conflicts concerning renewable energy sources [26,93]. At the same time, the need to implement renewable energy sources is noted, indicating benefits for the Polish spatial planning system [94]. However, from a legal perspective, these goals have been blocked for many years (through regulations introducing strict requirements for some renewable energy sources). From the perspective of the topic addressed by this article, it can be pointed out that the issues concerning the spatial planning of wind power plants were included in a separate law and that it was the restrictions on spatial plans in this law that blocked the implementation of most investments [94,95]. This is a very good example of statutory disorder: from the perspective of the entire spatial planning system, the sectoral act has become the main factor blocking the development of a serious part of the renewable energy sector. The implementation of green infrastructure (also significantly linked to climate challenges) in Poland is somewhat different. The concept of green infrastructure is not included in law and is not translated into the content of local spatial plans [96,97]. Both examples show the consequences of the legislator’s omissions. The indicated thematic planes, which are relevant from the perspective of climate challenges, are not implemented in the spatial planning system to an adequate degree.

A key problem, therefore, is a certain schematicity in framing a national perspective in the countries studied. Reference can be made to a recent assessment by Stead and Albrechts, according to whom a major problem with many spatial planning systems has been the absence of wider institutional change since at least the 1970s [98]. Attention should also be paid to the very way in which spatial planning acts are constructed in the countries studied. Polish solutions do not guarantee a synthesis between spatial planning law and the current important challenges. The most ambitious attempt in the group of the analyzed countries may have been undertaken in Ukraine by combining spatial planning and urban management. Nonetheless, at the level of detailed regulations, this attempt is insufficient, and unfortunately, against declarations, it involves combining spatial planning law and construction law. In this context, it should be emphasized that the role of law in spatial planning is a subject of varied discussion [23,99,100,101]. Undoubtedly, legal regulations will not solve all problems of spatial planning. If the regulations are too detailed, they may hinder development. Nonetheless, they should offer the possibility (from the institutional, systemic, but also terminological perspective) of adequate response of spatial planning instruments to the existing challenges. In the analyzed countries, legal regulations do not fulfill that role. The above fact is confirmed by results of comparisons of statutory approaches to values in spatial planning. All the approaches are chaotic, inconsequential and find moderate reflection in the application of detailed regulations.

The article also presents dilemmas occurring in the analyzed countries regarding national strategic documents regarding spatial planning. The example of Poland is significant, where no such document has existed for several years (despite the declarations of public authorities in the scope of works on the document that will only partially consider the spatial dimension). The strategic document existing at the national level in Belarus does not guarantee sufficient efficiency. By multiplying other systemic tendencies occurring in Belarus, the document rather creates the risk of imposing specific solutions from the perspective of the central government. In the case of Ukraine, the aforementioned national document includes attempts at a broader approach to spatial issues. It remains open, however, how the provisions of strategic documents will be implemented at a lower level. The scale of these discrepancies is reflected by the comparison of values included in the strategic documents regarding spatial planning and values concerning spatial planning included in the acts. In this scope, no coherence is observed among the analyzed countries. The lack of mechanisms of implementation of strategic provisions at the national level is another serious problem of the analyzed spatial planning systems.

The problems of spatial planning systems in the countries studied have many common features. Thus, reserving the peculiarities of each of the countries studied (as well as systemic barriers, war, etc.), an attempt can be made to develop common practical recommendations for each country, set apart. In particular, it should be proposed that in each country:

- A general evaluation of the laws from the perspective of their relationship and consistency with the “main” planning law be carried out;

- The result of such analyses should be an extended reflection on possible directions for integrated development planning in the respective system;

- A further practical direction should be the identification of new codes, relevant from the perspective of spatial planning law [102,103];

- A separate request is to refine the way in which key values are included in spatial planning laws and to make them consistent with the content of the strategic document;

- A basic requirement for strategic spatial planning is the introduction of a strategic document dealing with spatial planning at the national level in each system;

- At the same time, it should be ensured that this document does not contain detailed, prescriptive guidelines for selected projects (as is currently the case, for example, in Belarus).

Summing up the conclusions and recommendations, from a theoretical standpoint, our study brings additional evidence to the planning theory concerning the issue of comparing national planning systems concerning the role of national authorities, especially in countries experiencing or having experienced centralized systems. At the next level, this work is a contribution to the discussion concerning the relation between planning policies and governance systems.

The article includes a proposal of specific comparative methods further applicable to other countries and different spatial planning systems. The conducted analyses therefore encourage further research. Thus, important research directions are as follows:

- Detailed verifications of the statutory (national) approach to spatial planning in other European countries (both East-Central and Western Europe);

- Detailed analyses of the roles and contents of strategic documents of spatial planning in other European countries;

- Thorough analyses of the approaches to values of spatial planning in particular acts and strategic documents of selected countries, in addition to the determination of consequences (or lack of consequence) of the approach to the values in the said documents.

Separate further comparative analyses are required regarding spatial planning systems of the countries of East-Central Europe. It is necessary to further determine specific features and mutual differences occurring in the analyzed systems.

5. Conclusions

The study illustrates discrepancies (not only occurring in the three analyzed countries) between the area of strategic spatial planning and that of statutory/regulatory spatial planning. Despite evident differences in their systems, all the analyzed countries face serious problems regarding combining the said areas. Some of these problems result from the lack of ability to specify the role of law in spatial planning. This role is perceived too traditionally and too “technically”, with no consideration of the current challenges. A more broad understanding of spatial planning should be promoted, as should the necessity to provide conditions in which spatial planning instruments support diverse sectoral activities. In the analyzed countries, spatial planning law addresses detailed issues, but in a chaotic and uncoordinated way. The same approach is presented in the case of values in acts on spatial planning.

Similar verification is required by strategic spatial planning efforts at the national level. In the selected countries, such planning either does not exist at all (Poland), confirms the national centralization trends (Belarus) or requires considerable improvements (Ukraine). In East-Central Europe, a serious common barrier occurring in numerous countries are institutional problems. The results of comparisons included in the article confirm the serious scale of such problems. Therefore, the article provides an important material for discussions on spatial planning at the national level and approaches to comparing different spatial planning systems.

The results present answers to the research questions posed. From a statutory perspective, spatial planning topics are approached similarly in the countries studied. In addition to the “main” laws, there is a great deal of legislation in which spatial planning is included. As a whole, this introduces legal disorder and problems of interpretation. The values recognized by the laws are generally related to the objectives of spatial protection (in the environmental, cultural or architectural dimensions) but are formulated imprecisely. Referring to the second research question, it can be pointed out that in Belarus and Ukraine, there are strategic documents at the central level concerning spatial planning, while in Poland, there is no such document. However, there is a problem with the formulation of spatial planning objectives from a strategic perspective in the countries studied. There is a tendency to over-determine specific guidelines (which translates into excessive centralization of spatial planning). Spatial planning values, however, have been included more correctly in these documents.

The article presents certain research limitations. These limitations result from the systemic differences between the analyzed countries and the related synthetic difficulty of presenting the selected aspects in a comparative approach. It must also be made clear that the limitation is the analysis of three countries (far broader conclusions will result from a wider analysis). Nevertheless, when comparing national spatial planning systems, there is always a dilemma: whether to compare a larger number of countries but more superficially or to compare a smaller number of countries but in more depth. Despite these barriers, an attempt was undertaken to compare the issues at a possibly approximate degree, keeping proper characteristics of the specifics of the solutions of the analyzed countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N. and M.B.; methodology, M.N.; software, M.N., V.P., L.F. and R.L.; validation, M.N., V.P. and M.B.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.N., R.L. and L.F.; resources, M.B. and V.P.; data curation, M.N., R.L. and L.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.; writing—review and editing, V.P., M.B., L.F. and R.L.; visualization, M.B., L.F. and A.-I.P.; supervision, A.-I.P.; project administration, M.N., V.P. and M.B.; funding acquisition, A.-I.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Purkarthofer, E.; Humer, A.; Mattila, H. Subnational and Dynamic Conceptualisations of Planning Culture: The Culture of Regional Planning and Regional Planning Cultures in Finland. Plan. Theory Pract. 2021, 22, 244–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Governance of Land Use in OECD Countries: Policy Analysis and Recommendations; OECD Regional Development Studies; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Thornley, A. Urban Planning in Europe: International Competition, National Systems and Planning Projects; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nadin, V.; Fernández Maldonado, A.M.; Zonneveld, W.; Stead, D.; Dąbrowski, M.; Piskorek, K.; Sarkar, A.; Schmitt, P.; Smas, L.; Cotella, G. COMPASS–Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe: Applied Research 2016–2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/COMPASS-%E2%80%93-Comparative-Analysis-of-Territorial-and-%3A-Nadin-Maldonado/db9de110e698e5b3d6988e52aff984682d2ce145 (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Tosics, I. Urban Machinery: Inside Modern European Cities Edited by Mikael Hard and Thomas J. Misa. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J.; Lozynskyy, R.M.; Pantyley, V. Local spatial policy in Ukraine and Poland. Public Policy Stud. 2021, 8, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielen, D.M.; Tasan-Kok, T. Flexibility in Planning and the Consequences for Public-Value Capturing in UK, Spain and the Netherlands. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1097–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Gagakuma, D.; Blaszke, M. Spatial Management Systems in Ghana and Poland-Comparison of Solutions and Selected Problems. Świat Nieruchom. 2020, 111, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dühr, S. Investigating the Policy Tools of Spatial Planning. Policy Stud. 2023, 44, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Planning in the Public Domain: From Knowledge to Action; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, B.; Buitelaar, E.; Hartmann, T. Planning, Law and Economics: The Rules We Make for Using Land, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rydin, Y.; Beauregard, R.; Cremaschi, M.; Lieto, L. Regulation and Planning Practices, Institutions, Agency, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, M.; Hickman, H. The Demise of Strategic Planning? The Impact of the Abolition of Regional Spatial Strategy in a Growth Region. Town Plan. Rev. 2013, 84, 743–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, K. Dialectical Institutionalism: Spatial Imaginaries in Tensions between Strategic and Statutory Planning in City-Regions. Ph.D. Thesis, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hersperger, A.M.; Grădinaru, S.; Oliveira, E.; Pagliarin, S.; Palka, G. Understanding Strategic Spatial Planning to Effectively Guide Development of Urban Regions. Cities 2019, 94, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Śleszyński, P. Climate Protection in Spatial Policy Instruments, Opportunities and Barriers: The Case Study of Poland. In Climate Change, Community Response and Resilience; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Cities Policy Responses (OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19); OECD: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/cities-policy-responses-fd1053ff/ (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Impacts on Cities and Major Lessons for Urban Planning, Design, and Management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J. Is the Pandemic a Hope for Planning? Two Doubts. Plan. Theory 2022, 21, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Nowak, M.; Legutko-Kobus, P.; Abadi, M.H.H.; Nasiri, N.A. COVID-19 Spatial Policy: A Comparative Review of Urban Policies in the European Union and the Middle East. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannila, P. Relationality of the Law: On the Legal Collisions in the Finnish Planning and Land Use Practices. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2021, 41, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtudes, A. Urban Rehabilitation: A Glimpse from the Spatial Planning Law; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 471, p. 082032. [Google Scholar]

- Buitelaar, E.; Sorel, N. Between the Rule of Law and the Quest for Control: Legal Certainty in the Dutch Planning System. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, M.; Getimis, P.; Blotevogel, H. Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe: A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, B. Planning, Law and Economics: The Rules We Make for Using Land; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.J.; Brelik, A.; Oleńczuk-Paszel, A.; Śpiewak-Szyjka, M.; Przedańska, J. Spatial Conflicts Concerning Wind Power Plants—A Case Study of Spatial Plans in Poland. Energies 2023, 16, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Cotella, G.; Śleszyński, P. The Legal, Administrative, and Governance Frameworks of Spatial Policy, Planning, and Land Use: Interdependencies, Barriers, and Directions of Change. Land 2021, 10, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitelaar, E. The Fraught Relationship between Planning and Regulation. Land Use Plans and the Conflicts in Dealing with Uncertainty. In Planning by Law and Property Rights Reconsidered; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Auzins, A.; Chigbu, U.E. Values-Led Planning Approach in Spatial Development: A Methodology. Land 2021, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S. Climate Change and the Role of Spatial Planning in England. In Climate Change Governance; Knieling, J., Leal Filho, W., Eds.; Climate Change Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getimis, P. Comparing Spatial Planning Systems and Planning Cultures in Europe. The Need for a Multi-Scalar Approach. Plan. Pract. Res. 2012, 27, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L. Ingredients for a More Radical Strategic Spatial Planning. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2015, 42, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E. Making Strategies in Spatial Planning—Knowledge and Values. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterlynck, S.; Van Den Broeck, J.; Albrechts, L.; Moulaert, F.; Verthetsel, A. Strategic Spatial Projects. Catalysts for Change; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gedikli, B. Examination of the Interpretation of Strategic Spatial Planning in Three Cases from Turkey. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavenago, D.; Trivellato, B. Organising Strategic Spatial Planning: Experiences from Italian Cities. Space Polity 2010, 14, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, A. Linking Polycentricity Concepts to Periphery: Implications for an Integrative Austrian Strategic Spatial Planning Practice. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, R.; Cremaschi, M.; Rydin, Y.; Lieto, L. Response to EPS Review of Regulation and Planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 1295–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altrock, U.; Güntner, S. Spatial Planning and Urban Development in the New EU Member States; Peters, D., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D. The Governance of Spatial Development in Europe: Similar Challenges, Different Approaches? IV EUGEO Congress. Program and Abstract Congress Book; s.n.: Rome, Italy, 2013; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mironowicz, I.; Geppert, A. In Conversation with the Fox: Challenges in Spatial Development and Planning in Europe. disP Plan. Rev. 2017, 53, 50–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaprudski, I.I. Transformation of the Territorial-Sectoral Structure and Regionalization of the Industry of the Republic of Belarus. Ph.D. Thesis, Belarusian State University, Minsk, Belarus, 2019. Available online: https://vak.gov.by/sites/default/files/2019-04/Zaprudski_Autareferat.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Чиж, Д. Схема Землеустрoйства Административнoгo Райoна в Структуре Территoриальнoгo Планирoвания Республики Беларусь. Ştiinţa Agricolă 2011, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Региoнальнoе Развитие в Республике Беларусь: Вызoвы и Перспективы. 2015. Available online: https://www.economy.gov.by/uploads/files/002835_891055_4.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Чиж, Д.; Зайцев, B.; Тетеринец, T.; Червякoва, C. О Неoбхoдимoсти Кoнвергенции Идей Сoциальнo-Экoнoмическoгo Прoгнoзирoвания и Территoриальнoгo Планирoвания в Республике Беларусь. Cadastru şi Drept 2013, 33, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Habrel, M.; Kosmii, M.; Habrel, M. Meritocentric Model of Spatial Development in Ukraine: Updating the General Scheme of Planning of the State Territory. Spatium 2022, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzihovska, L.M.; Hulivata, I.O.; Husak, L.P.; Nikolina, I.I.; Ivashchuk, O.V. Peculiarities of Evaluating the Results of Implementation of Regional Development Programs in Ukraine. Nauk. Visn. Nat. Hirn. Univ. 2023, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruniak, E.O.; Palekha, Y.M.; Kryshtop, T.M. Planning of Spatial Development in Times of War and Reconstruction: A Vision for Ukraine. Ukr. Geogr. Z. 2023, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, Y. Project of the Law about Spatial Planning in Ukraine. 2017. Available online: https://city2030.org.ua/ua/document/proekt-zakonu-pro-prostorove-planuvannya/ (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Concepts of Public Management in the Area of Urban Planning. 2019. Available online: http://city2030.org.ua/sites/default/files/documents/CONCEPT%20of%20Public%20Administration.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Danko, Y.I.; Medvid, V.Y.; Koblianska, I.І.; Kornietskyy, O.V.; Reznik, N.P. Territorial Government Reform in Ukraine: Problem Aspects of Strategic Management. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Śleszyński, P.; Kowalewski, A.; Markowski, T.; Legutko-Kobus, P.; Nowak, M. The Contemporary Economic Costs of Spatial Chaos: Evidence from Poland. Land 2020, 9, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorens, P. Trends and Problems of Contemporary Urbanization Processes in Poland. In Spatial Planning and Urban Development in the New EU Member States; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Śleszyński, P. Potencjalne Koszty Odszkodowawcze Związane z Niewłaściwym Planowaniem Przestrzennym w Gminach. In Koszty Chaosu Przestrzennego; Studia KPZK PAN; KPZK PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 404–424. [Google Scholar]

- Lityński, P.; Hołuj, A. Urban Sprawl Costs: The Valuation of Households’ Losses in Poland. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2017, 8, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowski, T. Zintegrowane Planowanie Rozwoju–Dylematy i Wyzwania. Stud. Kom. Przestrz. Zagospod. Kraj. PAN 2015, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowski, M.; Piskorek, K. The Development of Strategic Spatial Planning in Central and Eastern Europe: Between Path Dependence, European Influence, and Domestic Politics. Plan. Perspect. 2018, 33, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrejička, V.; Ladzianska, Z.; Finka, M.; Baloga, M.; Husár, M. Spatial Planning Tools as a Key Element for Implementation of the Strategy for an Integrated Governance System of Historical Built Areas within the Central Europe Region. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 022088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Petrisor, A.-I.; Mitrea, A.; Kovács, K.F.; Lukstina, G.; Jürgenson, E.; Ladzianska, Z.; Simeonova, V.; Lozynskyy, R.; Rezac, V.; et al. The Role of Spatial Plans Adopted at the Local Level in the Spatial Planning Systems of Central and Eastern European Countries. Land 2022, 11, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J.; Śleszyński, P.; Legutko-Kobus, P. Spatial Planning in Poland: Law, Property Market and Planning Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. SPINE Spatial Planning Instruments and the Environment; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/environment/tools-evaluation/brochure-spatial-planning-instruments-and-the-environment.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Oliveira, E.; Leuthard, J.; Tobias, S. Spatial Planning Instruments for Cropland Protection in Western European Countries. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D. Conceptualizing the Policy Tools of Spatial Planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2021, 36, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, L.; Bianconi, M. Which Aims and Knowledge for Spatial Planning? Some Notes on the Current State of the Discipline. Town Plan. Rev. 2014, 85, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallagst, K.M.; Mercier, G. Urban and Regional Planning in Central and Eastern European Countries—From EU Requirements to Innovative Practices. In The Post-Socialist City; Stanilov, K., Ed.; The GeoJournal Library; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 92, pp. 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feranec, J.; Soukup, T.; Taff, G.N.; Stych, P.; Bicik, I. Overview of Changes in Land Use and Land Cover in Eastern Europe. In Land-Cover and Land-Use Changes in Eastern Europe after the Collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991; Gutman, G., Radeloff, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. The Spatial Management System in Poland: The Categorisation of the Problem from the Perspective of the Literature on the Subject. Zarządzanie Publiczne 2021, 55, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auziņš, A.; Jürgenson, E.; Burinskienė, M. Comparative Analysis of Spatial Planning Systems and Practices: Changes and Continuity in Baltic Countries: A Comparative Study of Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. Methods Concepts Land Manag. Divers. Changes New Approaches 2020, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rząsa, K.; Caporusso, G.; Ogryzek, M.P.; Tarantino, E. Spatial Planning Systems in Poland and Italy—Comparative Analysis on the Example of Olsztyn and Bari. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszke, M.; Nowak, M.J. Objectives of Spatial Planning in Selected Central and Eastern European Countries. Analysis of Selected Case Studies. Ukr. Geogr. Z. 2023, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. The Treatment of Space and Place in the New Strategic Spatial Planning in Europe. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullingworth, B.; Nadin, V. Town and Country Planning in the UK; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Towards a New Role for Spatial Planning; OECD: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 5 July 2004 of the Republic of Belarus on Architectural, Urban Planning and Construction Activities in the Republic of Belarus, No. 300-Z. Available online: https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=6739 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Act of 16 November 1992 about Fundamentals of Town Planning, Low of Ukraine No. 2780-XII. Available online: https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=16052 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Act of 17 February 2011 on Regulation of Town-Planning Activities, Low of Ukraine No. 3038-VI. Available online: https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=32960 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Act of 27 March 2003 o Planowaniu i Zagospodarowaniu Przestrzennym, Journal of Laws 2021, Item 741. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20030800717/U/D20030717Lj.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- National Scheme of Complex Territorial Organisation of the Republic of Belarus. Chapter 5 in Resolution of the Ministry of Architecture and Construction the Republic of Belarus November 16, 2020. No. 87 on the Approval and Commissioning of Construction Norms SN 3.01.02-2020. pp. 6–7. Available online: https://pravo.by/document/?guid=12551&p0=W22136325p (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Act of 7 February 2002 about the General Scheme of Planning of the Territory of Ukraine, Low of Ukraine No. 5459-VI. Available online: https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=18262 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- National Strategy of Regional Development for the Period 2021–2027. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/695-2020-%D0%BF#Text (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- The National Sustainable Development Strategy for the Period until 2035. Available online: https://economy.gov.by/uploads/files/ObsugdaemNPA/NSUR-2035-1.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Decree 179/2021 Approving the National Economic Strategy for the Period up to 2030, Republic of Ukraine, 3 March 2021. Available online: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/npas/pro-zatverdzhennya-nacionalnoyi-eko-a179 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Resolution No. 102 of the Council of Ministers of 17 September 2019 on the Adoption of the “National Strategy for Regional Development 2030”, M.P. 2019, Item 1060. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WMP20190001060/O/M20191060.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Thoidou, E. Spatial Planning and Climate Adaptation: Challenges of Land Protection in a Peri-Urban Area of the Mediterranean City of Thessaloniki. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S. The Value of Planning and the Values in Planning. Town Plan. Rev. 2016, 87, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourgiotis, A.; Kyvelou, S.; Lainas, I. Industrial Location in Greece: Fostering Green Transition and Synergies between Industrial and Spatial Planning Policies. Land 2021, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olcina, J. Land Use Planning and Green Infrastructure: Tools for Natural Hazards Reduction. In Disaster Risk Reduction for Resilience; Eslamian, S., Eslamian, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeglehner, G.; Abart-Heriszt, L. Integrated Spatial and Energy Planning in Styria—A Role Model for Local and Regional Energy Transition and Climate Protection Policies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 165, 112587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszke, M.; Foryś, I.; Nowak, M.J.; Mickiewicz, B. Selected Characteristics of Municipalities as Determinants of Enactment in Municipal Spatial Plans for Renewable Energy Sources—The Case of Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszke, M.; Nowak, M.; Śleszyński, P.; Mickiewicz, B. Investments in Renewable Energy Sources in the Concepts of Local Spatial Policy: The Case of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, R.; Koutsoyiannis, D. A Review of Land Use, Visibility and Public Perception of Renewable Energy in the Context of Landscape Impact. Appl. Energy 2020, 276, 115367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P.; Nowak, M.; Brelik, A.; Mickiewicz, B.; Oleszczyk, N. Planning and Settlement Conditions for the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland: Conclusions for Local and Regional Policy. Energies 2021, 14, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degórski, M.; Kaczmarek, H.; Komornicki, T.; Kordowski, J.; Lamparski, P.; Milewski, P. Energetyka Wiatrowa w Kontekście Ochrony Krajobrazu Przyrodniczego i Kulturowego w Województwie Kujawsko-Pomorskim. Geogr. Przestrz. Zagospod. Im. Stanisława Leszczyckiego PAN Warszawie 2012, 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Solarek, K.; Kubasińska, M. Local Spatial Plans as Determinants of Household Investment in Renewable Energy: Case Studies from Selected Polish and European Communes. Energies 2021, 15, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goździewicz-Biechońska, J. Green Infrastructure in the Rural Areas as EU Environmental Policy Measure. Stud. Iurid. Lublinensia 2017, 26, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulczewska, B.; Blaszke, M.; Giedych, R.; Wójcik-Gront, E.; Legutko-Kobus, P.; Nowak, M.J. Ratio of Biologically Vital Area in Local Spatial Plans as an Instrument of Green Infrastructure Creation in Single- and Multi-Family Residential in Small and Medium-Sized Towns in Poland. Teka Kom. Urban. Archit. Oddziału Pol. Akad. Nauk. Krakowie 2023, 50, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrişor, A.-I.; Mierzejewska, L.; Mitrea, A.; Drachal, K.; Tache, A.V. Dynamics of Open Green Areas in Polish and Romanian Cities During 2006–2018: Insights for Spatial Planners. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D.; Albrechts, L. European Planning Studies at 30—Past, Present and Future. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, E. Takings International: A Comparative Perspective on Land Use Regulations and Compensation Rights; American Bar Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moroni, S.; Buitelaar, E.; Sorel, N.; Cozzolino, S. Simple Planning Rules for Complex Urban Problems: Toward Legal Certainty for Spatial Flexibility. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2020, 40, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J.; Śleszyński, P.; Ostrowska, A.; Oleńczuk-Paszel, A.; Śpiewak-Szyjka, M.; Mitrea, A. Planning Disputes from the Perspective of Court Rulings on Building Conditions. A Case Study of Poland. Plan. Pract. Res. 2023, 38, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausner, J.; Nowak, M.J. Rola Prawa w Systemie Gospodarki Przestrzennej. In Społeczna Czasoprzestrzeń Rozwoju Miasta a Prawo Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego; Wydawnictwo Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.J.; Monteiro, R.; Olcina-Cantos, J.; Vagiona, D.G. Spatial Planning Response to the Challenges of Climate Change Adaptation: An Analysis of Selected Instruments and Good Practices in Europe. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).