The Impacts of Tourism Development on Urban–Rural Integration: An Empirical Study Undertaken in the Yangtze River Delta Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Impact of Tourism Development on the Urban Area and Rural Area

2.2. Tourism Development and URI

3. Research Data and Methods

3.1. Research Region

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Regression Model

3.2.2. Threshold Model

3.2.3. Variable Selection

- (1)

- Dependent variable. URI (uri), as an advanced stage in the development of the urban–rural system, encompasses the integration dynamics, integration process, and integration state. It signifies the convergence of various linkages between urban and rural domains, encompassing population mobility, facility connectivity, public service provision, and land space expansion, which manifests in the realms of population, space, economy, and society [51,52]. URI constitutes the physical spatial connection and social support network between urban and rural areas, adapting to the distinct stages of economic and social development within these regions. Therefore, we constructed an index system to measure the level of URI on the basis of urban–rural linkages. The process begins with sorting out the types of existing urban–rural linkages, and the URI evaluation index system is divided into four dimensions: population mobility, facility connectivity, public service provision, and land space expansion. The selection of indicators follows the principles of data availability, systematization, and representativeness, as shown in Table 1. Among them, the social dimension, educational level, and medical level are strong assurances for the coordinated development of urban and rural areas. Meanwhile, the entropy method was used to calculate index weights and evaluation indices; see reference [53] for the specific calculation procedure.

- (2)

- Core independent variable. Tourism development (td) performs a pivotal task in expediting the pace of URI. To assess tourism’s impact on URI, it is common in scholarly research to employ tourism depth indicators, which are selected based on empirical findings and sound scientific considerations [52,54]. Referring to Shan et al. [55], this study used the ratio of total tourism income to GDP to represent tourism development. Additionally, the ratio of tourist numbers to the whole population size was utilized as an alternative when conducting robustness tests. Tourism income is the economic output of tourism development. The tourism number is the number of tourists and can also be used to mirror the level of tourism development [56]. Thus, we made use of the ratio of tourist numbers to whole population size as an alternative when conducting robustness tests.

- (3)

- Threshold variable. We further assessed how economic expansion affected the development of the tourism industry and URI. Referring to the work of Gan et al. [52], we took the per capita GDP (pgdp) as the threshold variable.

- (4)

- Control variables. Following the previous studies on factors affecting URI, we controlled the influence of trade openness (open), regional investment (inve), government intervention (gov), technology innovation (tech), and industrial structure optimization (ind) [3].

4. Results

4.1. The Analysis Results of URI

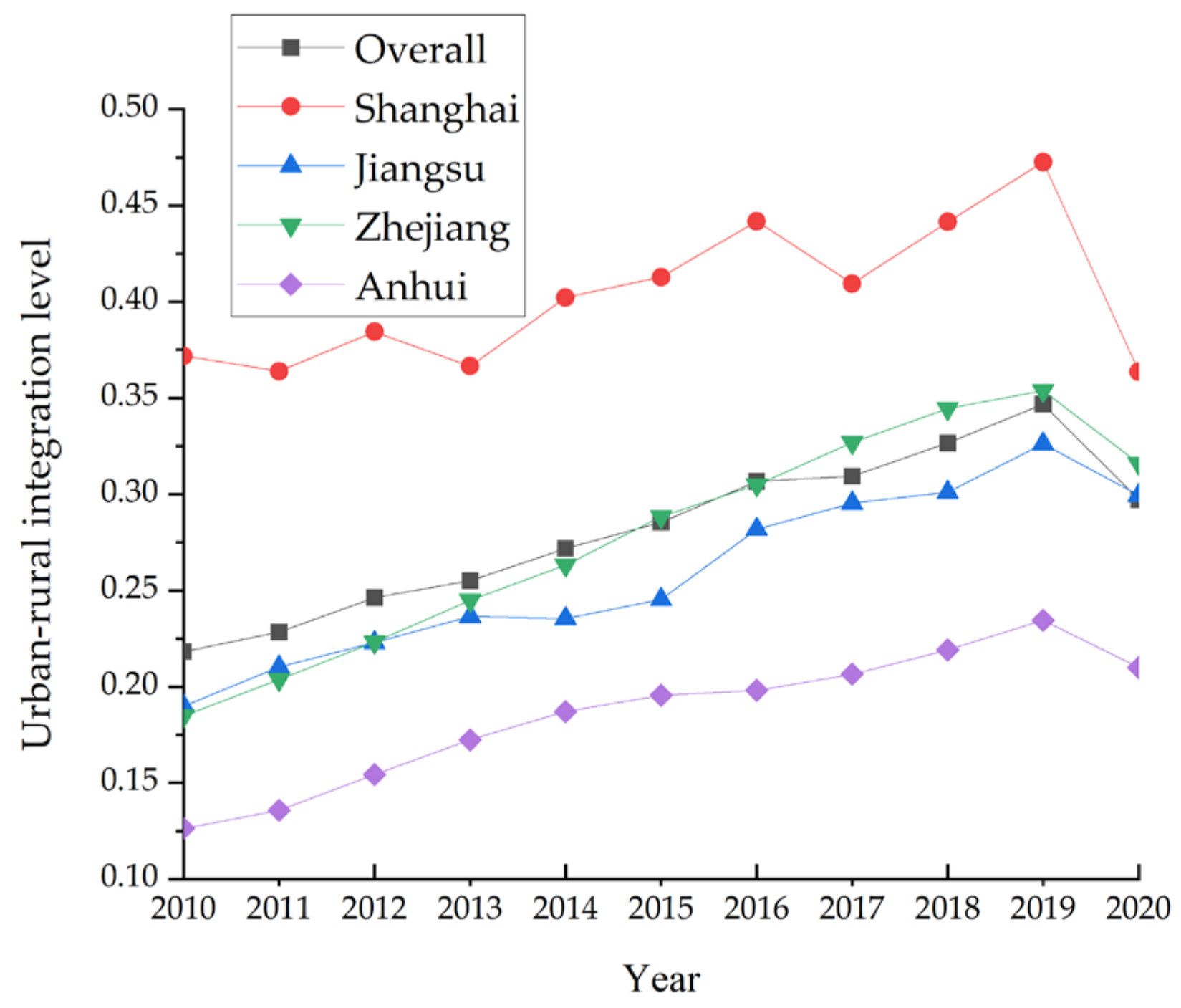

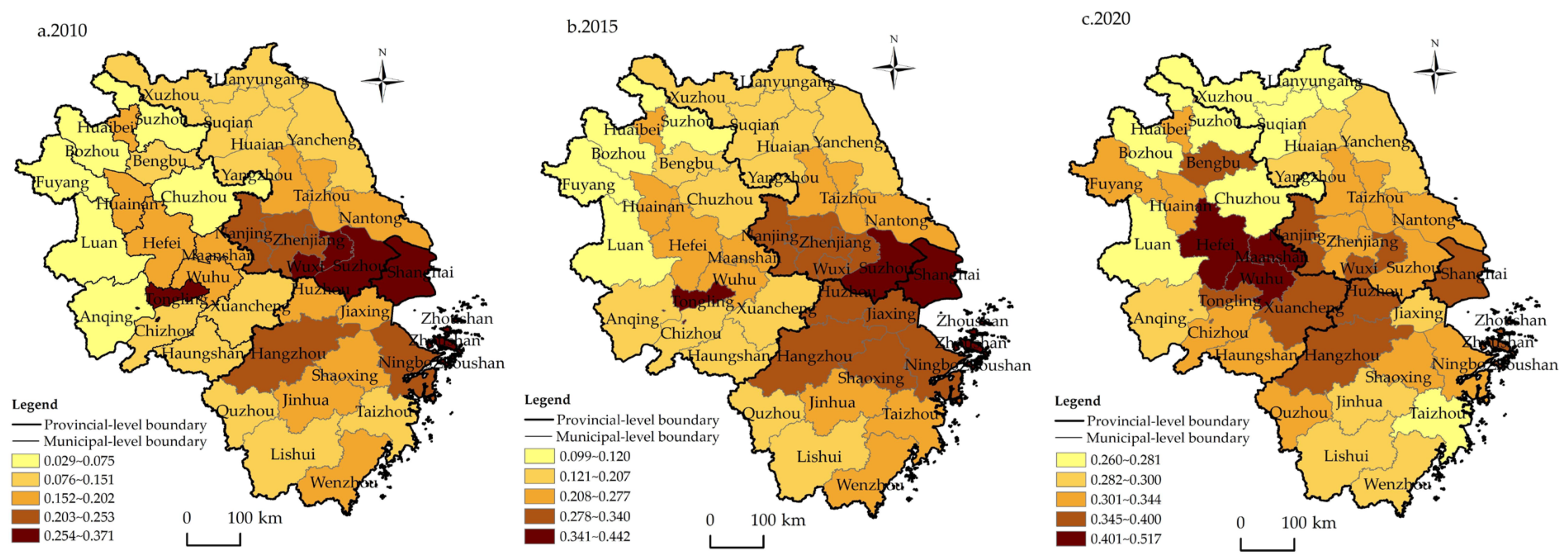

4.1.1. The Evolutionary Characteristics of URI

4.1.2. Spatial Characteristics of the URI

4.2. The Impacts of Tourism Development on URI

4.2.1. Descriptive Analysis and Panel Stationarity Test

4.2.2. Panel Stationarity Test

- (1)

- Benchmark regression

- (2)

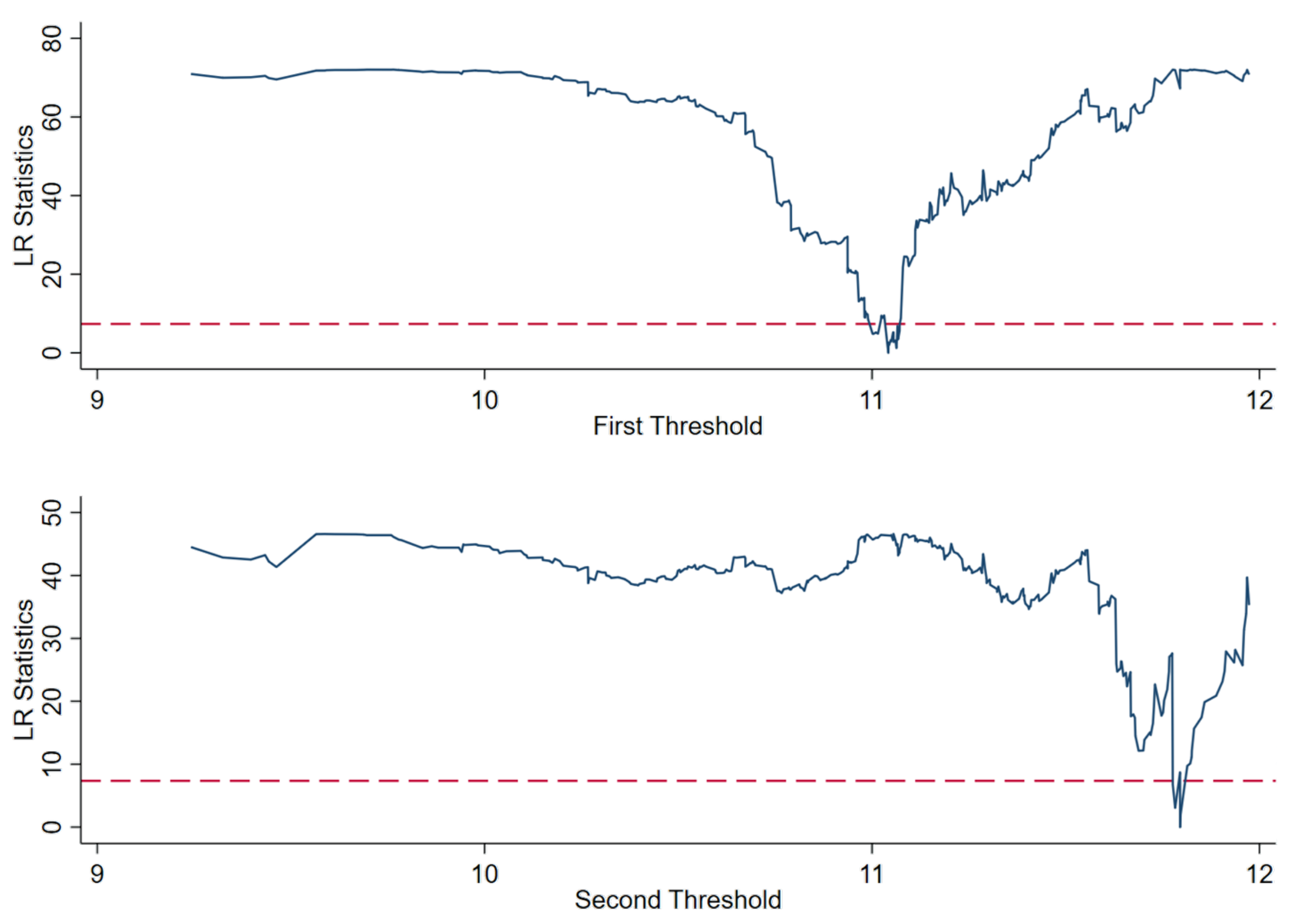

- Threshold effect test

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Regression Results

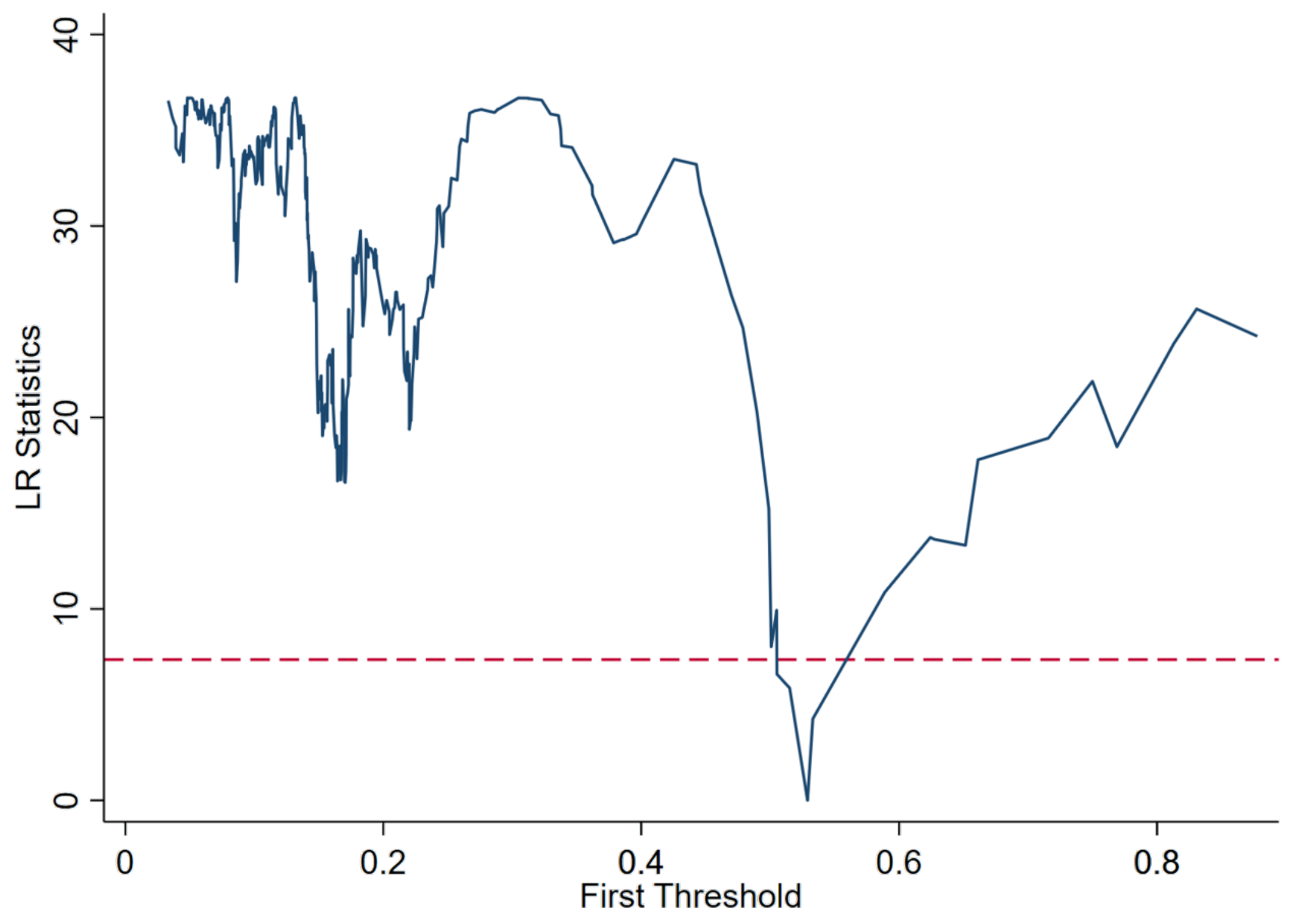

4.3.2. Threshold Test

4.3.3. Effect of Tourism Development on URI at Different Stages

4.3.4. Robustness Tests

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J. The effects of tourism on income inequality: A meta-analysis of econometrics studies. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z. Strategies of landscape planning in peri-urban rural tourism: A comparison between two villages in China. Land 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Tourism and rural income inequality: Empirical evidence for China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.G. An integrative framework for urban tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 926–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanescu, B.-C.; Stoleriu, O.M.; Munteanu, A.; Iatu, C. The impact of tourism on sustainable development of rural areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. Urban-rural migration, tourism entrepreneurs and rural restructuring in Spain. Tour. Geogr. 2002, 4, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Nolan, R.; Dollman, J.; Coffee, N. Neighbourhood environmental attributes associated with walking in South Australian adults: Differences between urban and rural areas. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Qiu, H.; Lam, C.F. Urbanization impacts on regional tourism development: A case study in China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, R.; Chen, M.-H.; Su, C.-H.; Zhi, Y.; Xi, J. Effects of rural revitalization on rural tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuts, B. Tourism and urban economic growth: A panel analysis of German cities. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Liu, M.; Ye, Y. Measuring the degree of balance between urban and tourism development: An analytical approach using cellular data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. Residents’ perceptions of the impact of cultural tourism on urban Development: The case of Gwangju, Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 15, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Hong, T.; Zhang, H. Tourism spatial spillover effects and urban economic growth. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsouris, A.; Gidarakou, I.; Grava, F.; Michailidis, A. The phantom of (agri)tourism and agriculture symbiosis? A Greek case study. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 12, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R. The role of tourism in poverty reduction: An empirical assessment. Tour. Econ. 2014, 20, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Li, X.; Chen, W.; Tan, H.; Luo, L.; Xu, X. Tourists’ digital footprint: The spatial patterns and development models of rural tourism flows network in Guilin, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 1336–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M. Effectiveness of social media marketing on enhancing performance: Evidence from a casual-dining restaurant setting. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Tang, J.; Dombrosky, J.M. Coupling relationship of tourism urbanization and rural revitalization: A case study of Zhangjiajie, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, J.M.; Nijkamp, P.; Petrick, J.F. Threshold effect of tourism density on urban livability: A modeling study on Chinese cities. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2023, 70, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Nijkamp, P.; Huang, X.; Lin, D. Urban livability and tourism development in China: Analysis of sustainable development by means of spatial panel data. Habitat Int. 2017, 68, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Clarke, N.; Hracs, B.J. Urban-rural mobilities: The case of China’s rural tourism makers. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 95, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liao, H.; Qiu, J.; Liu, Y. Characteristics of spatiotemporal variations and driving factors of land use for rural tourism in areas that eliminated poverty. Land 2023, 12, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, R.; Suardi, S.; Ji, C.; Hanyu, Z. Is urbanization the link in the tourism–poverty nexus? Case study of China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3357–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Du, L.; Tian, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Sustainability of rural tourism in poverty reduction: Evidence from panel data of 15 underdeveloped counties in Anhui Province, China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossou, T.A.M.; Ndomandji Kambaye, E.; Bekun, F.V.; Eoulam, A.O. Exploring the linkage between tourism, governance quality, and poverty reduction in Latin America. Tour. Econ. 2023, 29, 210–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S. Rural poverty, toursm and spatial heterogeneity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, J. Pro-poor tourism as a strategy to fight rural poverty: A critique. J. Agrar. Change 2015, 15, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Wang, H.; Quan, Q.; Xu, J. Rurality and rural tourism development in China. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dou, X.; Li, J.; Cai, L.A. Analyzing government role in rural tourism development: An empirical investigation from China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, G.; Liu, H. Analysis of the impact of tourism development on the urban-rural income gap: Evidence from 248 prefecture-level cities in China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ling, L.; Huang, Z. Tourism migrant workers: The internal integration from urban to rural destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Shekari, F.; Mohammadi, Z.; Azizi, F.; Ziaee, M. World heritage tourism triggers urban-rural reverse migration and social change. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swidynska, N.; Witkowska-Dabrowska, M. Indicators of the tourist attractiveness of urban-rural communes and sustainability of peripheral areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Nijkamp, P.; Lin, D. Urban-rural imbalance and tourism-led growth in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 64, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, S. International trade in services and inequalities: Empirical evaluation and role of tourism services. Tour. Econ. 2016, 23, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Luo, M.; Jin, M.; Cheng, S.K.; Li, K.X. Urban-rural income disparity and inbound tourism: Spatial evidence from China. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 1231–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cai, J.; Sliuzas, R. Agro-tourism enterprises as a form of multi-functional urban agriculture for peri-urban development in China. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Roldan, J.L.; Jaafar, M.; Ramayah, T. Factors influencing residents’ perceptions toward tourism development: Differences across rural and urban world heritage sites. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 760–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladkin, A.; Mooney, S.; Solnet, D.; Baum, T.; Robinson, R.; Yan, H. A review of research into tourism work and employment: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism work and employment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2023, 100, 103554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A new style of urbanization in China: Transformation of urban rural communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, J.M.D.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Linking blue carbon ecosystems with sustainable tourism: Dichotomy of urban-rural local perspectives from the Philippines. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 45, 101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Liao, P.-T. The effect of tourism on teleconnected ecosystem services and urban sustainability: An emergy approach. Ecol. Model. 2021, 439, 109343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Ma, P.; Wang, W. Urban-rural income gap and air pollution: A stumbling block or stepping stone. Environ. Impact Asses. 2022, 94, 106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L. Forecast without historical data: Objective tourist volume forecast model for newly developed rural tourism areas of China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, A.; Arbache, J.S.; Sinclair, M.T.; Teles, V. Tourism and poverty relief. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Geng, Y. Fiscal decentralization, urban-rural income gap, and tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarębski, P.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Oklevik, O. Tourism investment gaps in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Ritchie, B.W.; Benckendorff, P.J.; Bao, J. Emotional responses toward Tourism Performing Arts Development: A comparison of urban and rural residents in China. Tour Manag. 2019, 70, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hou, G. Analysis on the spatial-temporal evolution characteristics and spatial network structure of tourism eco-efficiency in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.-g.; Xu, K.; Duan, K. Investigating the intention to participate in environmental governance during urban-rural integrated development process in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 128, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Chen, H.; Xia, F. Toward improved land elements for urban-rural integration: A cell concept of an urban-rural mixed community. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Wang, K.; Voda, M.; Ye, J.; Chen, L. Analysis on the impact of technological innovation on tourism development: The case of Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration in China. Tour. Econ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, Q. Study on spatial-temporal evolution characteristics and restrictive factors of urban-rural integration in Northeast China from 2000 to 2019. Land 2022, 11, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, H.; Weng, L. Transformation of rural space under the impact of tourism: The case of Xiamen, China. Land 2022, 11, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Ren, Z. Does tourism development and renewable energy consumption drive high quality economic development? Resour. Policy 2023, 80, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Zhang, D. Does tourism promote economic growth in Chinese ethnic minority areas? A nonlinear perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, P.; Dwyer, L.; Spurr, R. Is Australian tourism suffering Dutch Disease? Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; He, J.; Yang, H. Population ageing, financial deepening and economic growth: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Duignan, M. Progress in tourism management: Is urban tourism a paradoxical research domain? Progress since 2011 and prospects for the future. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.; Abrahams, R. Mediating urban transition through rural tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wei, Y.D.; Huang, X.; Chen, B. Economic transition, spatial development and urban land use efficiency in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Xu, D. Spatial econometric analysis of cultural tourism development quality in the Yangtze River Delta. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juschten, M.; Hössinger, R. Out of the city—but how and where? A mode-destination choice model for urban–rural tourism trips in Austria. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Indicator | Calculation Method | Data Sources | Weights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Spatial agglomeration | Rate of urbanization (%) | Data from the “statistical bulletin of national economic and social development of each city report”, 2010 to 2020. | 0.096 |

| Society | Education levels | The ratio of students to teachers in urban general secondary schools and in rural general secondary schools (%) | Data from the China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook, 2011 to 2021. | 0.073 |

| Medical levels | The ratio of the number of doctors per 1000 people in urban areas to the number of doctors per 1000 people in rural areas (%) | Data from the China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook, 2011 to 2021. | 0.138 | |

| Space | Traffic accessibility | The proportion of road mileage to land area (km/km2) | Data from the China City Statistical Yearbook, 2011 to 2021. | 0.418 |

| Information accessibility | The number of subscribers with access to Internet broadband per 10,000 people (households/million people) | Data from the Zhejiang Statistical Yearbook, Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook, Anhui Statistical Yearbook, and Shanghai Statistical Yearbook, 2011 to 2021. | 0.243 | |

| Economy | Income levels | The ratio of urban per capita disposable earnings to rural per capita disposable profits (%) | Data from the Zhejiang Statistical Yearbook, Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook, Anhui Statistical Yearbook, and Shanghai Statistical Yearbook, 2011 to 2021. | 0.004 |

| Consumption levels | The ratio of urban per capita consumption expenditure to rural per capita consumption expenditure (%) | Data from the Zhejiang Statistical Yearbook, Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook, Anhui Statistical Yearbook, and Shanghai Statistical Yearbook, 2011 to 2021. | 0.028 |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | Skewness | Kurtosis | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| uri | 0.246 | 0.095 | 0.029 | 0.517 | 0.279 | 2.688 | — |

| td | 0.187 | 0.175 | 0.029 | 1.067 | 2.907 | 12.225 | 1.06 |

| lnopen | 29.38 | 31.56 | 1.364 | 201.037 | 2.081 | 8.068 | 1.58 |

| lninve | 0.757 | 0.26 | 0.001 | 1.468 | 0.251 | 2.695 | 1.53 |

| lngov | 1.729 | 1.028 | 0.262 | 14.576 | 4.774 | 55.658 | 1.50 |

| lntech | 0.36 | 0.236 | 0.021 | 2.14 | 2.327 | 13.231 | 1.39 |

| lnind | 0.438 | 0.085 | 0.233 | 0.731 | 0.315 | 3.706 | 1.05 |

| lnpgdp | 10.954 | 0.622 | 9.112 | 12.201 | −0.474 | 2.789 | 2.41 |

| uri | td | lnopen | lninve | lngov | lntech | lnind | lnpgdp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| uri | — | |||||||

| td | 0.120 ** | — | ||||||

| lnopen | 0.478 *** | 0.001 | — | |||||

| lninve | 0.275 *** | 0.183 *** | −0.534 *** | — | ||||

| lngov | −0.558 *** | 0.080 * | −0.350 *** | 0.273 *** | — | |||

| lntech | 0.577 *** | −0.075 * | 0.249 *** | −0.056 | −0.501 *** | — | ||

| lnind | 0.146 *** | −0.053 | 0.182 *** | −0.139 *** | −0.178 *** | 0.082 * | — | |

| lnpgdp | 0.764 *** | 0.054 | 0.513 *** | −0.370 *** | −0.609 *** | 0.560 *** | 0.175 *** | — |

| Variable | LLC Test | IPS Test | Fisher−ADF Test | PP Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| uri | −4.274 *** | −2.638 *** | −7.274 *** | 169.306 *** |

| td | −2.315 ** | −2.105 ** | −5.454 *** | 217.639 *** |

| lnopen | −5.233 *** | −1.769 ** | −5.948 *** | 1393.397 *** |

| lninve | −8.810 *** | −3.397 *** | −5.324 *** | 779.423 *** |

| lngov | −54.111 *** | −11.039 *** | −4.124 *** | 529.452 *** |

| lntech | −3.506 *** | −1.941 ** | −2.256 *** | 453.392 *** |

| lnind | −31.827 *** | −6.241 *** | −6.624 *** | 438.026 *** |

| lnpgdp | −3.100 *** | −1.844 *** | −1.404 * | 194.246 *** |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| td | 0.318 *** (7.92) | 0.285 *** (7.37) | 0.242 *** (6.08) | 0.280 *** (7.70) | 0.270 *** (9.05) | 0.269 *** (8.97) |

| lnopen | −0.001 *** (−6.39) | −0.001 * (−6.58) | −0.001 *** (−7.40) | −0.0009 *** (−6.82) | −0.0001 ** (−6.80) | |

| lninve | 0.077 ** (3.67) | 0.090 *** (4.73) | 0.058 *** (3.66) | 0.059 *** (3.68) | ||

| lngov | −0.028 *** (−9.49) | −0.011 *** (−4.20) | −0.011 * (−4.22) | |||

| lntech | 0.200 *** (14.02) | 0.200 *** (14.00) | ||||

| lnind | −0.015 (−0.48) | |||||

| _cons | 0.186 | 0.227 | 0.177 | 0.210 | 0.126 | 0.057 |

| sigma_u | 0.090 | 0.112 | 0.122 | 0.113 | 0.095 | 0.096 |

| sigma_e | 0.057 | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.048 | 0.039 | 0.039 |

| Threshold Variable | Number | F Value | p-Value | Threshold Critical | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 5% | 10% | ||||

| td | Single | 91.13 | 0.040 | 50.879 | 35.678 | 28.534 |

| lnpgdp | Single | 99.61 | 0.000 | 48.221 | 38.791 | 33.541 |

| Double | 98.71 | 0.010 | 43.626 | 32.463 | 25.7 | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| td ≤ 0.528 | 0.436 *** (10.740) | — |

| td > 0.528 | 0.270 *** (9.380) | — |

| lnpgdp ≤ 11.042 | — | 0.183 *** (6.380) |

| 11.042 < lnpgdp ≤ 11.795 | — | 0.375 *** (12.470) |

| lnpgdp > 11.795 | — | 0.713 *** (6.080) |

| lnopen | −0.001 *** (−6.840) | −0.001 *** (−4.550) |

| lnfund | 0.035 *** (2.220) | 0.063 *** (4.380) |

| lngov | −0.028 *** (−4.770) | −0.012 *** (−4.810) |

| lntech | 0.189 *** (13.660) | 0.168 *** (12.730) |

| lnind | −0.013 (−0.420) | 0.027 (0.357) |

| _cons | 0.130 *** (7.110) | 0.108 *** (6.080) |

| R2 | 0.612 | 0.662 |

| F statistics | 91.13 | 98.71 |

| Variables | General City | High−Grade City | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| td | 0.256 *** 8.68 | — | — | 1.043 *** | — |

| (3.85) | |||||

| lnopen | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** |

| (−3.59) | −2.92) | (−3.66) | (−3.59) | (−3.33) | |

| lninve | 0.058 *** | 0.059 *** | 0.037 ** | −0.160 * | −0.118 *** |

| (3.51) | 3.86) | (2.25) | (−1.88) | −1.59) | |

| lngov | −0.009 *** | −0.009 *** | −0.010 *** | −0.151 * | −0.116 |

| (−3.37) | (−3.75) | (−3.93) | (−1.68) | −1.44) | |

| lntech | 0.227 *** | 0.189 *** | 0.214 *** | 0.081 * | 0.088 ** 2.42) |

| (12.43) | (10.61) | (12.07) | (1.98) | ||

| lnind | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.004 | (−0.01 | 0.071 |

| (4.38) | (0.31) | (0.01) | (−0.14) | 1.09) | |

| lnpgdp ≤ 11.031 | — | 0.183 *** | — | — | — |

| 6.23 | |||||

| lnpgdp > 11.031 | — | 0.358 *** | — | — | — |

| 11.53 | |||||

| td ≤ 0.528 | — | — | 0.411 *** | — | — |

| 10.16 | |||||

| td > 0.528 | — | — | 0.261 *** | — | — |

| 9.22 | |||||

| lnpgdp ≤ 11.719 | — | — | — | — | 0.767 *** |

| 3.08 | |||||

| lnpgdp > 11.719 | — | — | — | — | 1.063 *** |

| 4.41 | |||||

| _cons | 0.091 | 0.094 | 0.092 | 0.441 | 0.347 |

| sigma_u | 0.077 | 0.06 | 0.074 | 0.069 | 0.058 |

| sigma_e | 0.038 | 0.036 | 0.037 | 0.042 | 0.037 |

| R2 | 0.583 | 0.6379 | 0.6162 | 0.669 | 0.742 |

| F statistics | 77.84 | 83.82 | 76.38 | 21.61 | 25.98 |

| City Type | Threshold Variable | Number | Threshold Value | p-Value | F Value | Threshold Critical | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 5% | 10% | ||||||

| Ordinary cities | td | Single | 0.528 | 0.080 | 31.370 | 57.651 | 38.509 | 29.66 |

| lnpgdp | Single | 11.031 | 0.006 | 67.070 | 55.017 | 37.514 | 30.916 | |

| High-grade cities | lnpgdp | Single | 11.719 | 0.040 | 18.780 | 25.505 | 17.797 | 14.743 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2010–2014 | 2015–2020 | |

| td | 0.330 ** (8.87) | 0.104 ** (2.10) |

| lnopen | −0.001 ** (−2.49) | −0.0006 *** (−3.82) |

| lninve | 0.079 *** (5.73) | −0.020 (−0.88) |

| lngov | −0.003 (−1.88) | −0.022 *** (−3.93) |

| lntech | 0.169 *** (6.15) | 0.135 *** (6.87) |

| lnind | 0.020 (0.76) | 0.035 (0.76) |

| cons | 0.057 *** (3.22) | 0.261 *** (8.10) |

| sigma_u | 0.094 | 0.069 |

| sigma_e | 0.017 | 0.035 |

| R−squared | 0.614 | 0.495 |

| Model | FE | FE |

| Variable | FE | System GMM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| L. lnurd | — | — | 0.826 *** (25.22) |

| lntist | 0.001 *** (8.11) | — | — |

| td | — | 0.368 *** (12.79) | 0.100 ** (2.67) |

| lnopen | −0.0008 (−6.16) | −0.0009 *** (−7.67) | 0.001 *** (3.00) |

| lninve | 0.091 *** (5.82) | 0.047 *** (3.09) | 0.013 (0.42) |

| lngov | −0.009 *** (−3.44) | −0.002 (−0.89) | −0.138 *** (−2.29) |

| lntech | 1.902 *** (13.02) | 0.130 *** (5.90) | 0.138 *** (3.42) |

| lnind | −0.011 (−0.34) | −0.003 (−0.12) | 0.477 *** (6.61) |

| _cons | 0.129 *** (6.61) | 0.121 *** (6.84) | — |

| sigma_u | 0.080 | 0.114 | — |

| sigma_e | 0.040 | 0.034 | — |

| R2 | 0.566 | 0.565 | — |

| AR(1) | — | — | 0.016 |

| AR(2) | — | — | 0.696 |

| Hansen | — | — | 0.594 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, J.; Wang, K.; Gan, C.; Ma, X. The Impacts of Tourism Development on Urban–Rural Integration: An Empirical Study Undertaken in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Land 2023, 12, 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071365

Tan J, Wang K, Gan C, Ma X. The Impacts of Tourism Development on Urban–Rural Integration: An Empirical Study Undertaken in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Land. 2023; 12(7):1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071365

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Jiaxin, Kai Wang, Chang Gan, and Xuefeng Ma. 2023. "The Impacts of Tourism Development on Urban–Rural Integration: An Empirical Study Undertaken in the Yangtze River Delta Region" Land 12, no. 7: 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071365

APA StyleTan, J., Wang, K., Gan, C., & Ma, X. (2023). The Impacts of Tourism Development on Urban–Rural Integration: An Empirical Study Undertaken in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Land, 12(7), 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071365