A Study on the Influencing Factors and Multiple Driving Paths of Social Integration of Reservoir Resettlers: An Empirical Analysis Based on SEM and fsQCA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Analysis

2.1.1. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

2.1.2. Theory of Social Capital (TSC)

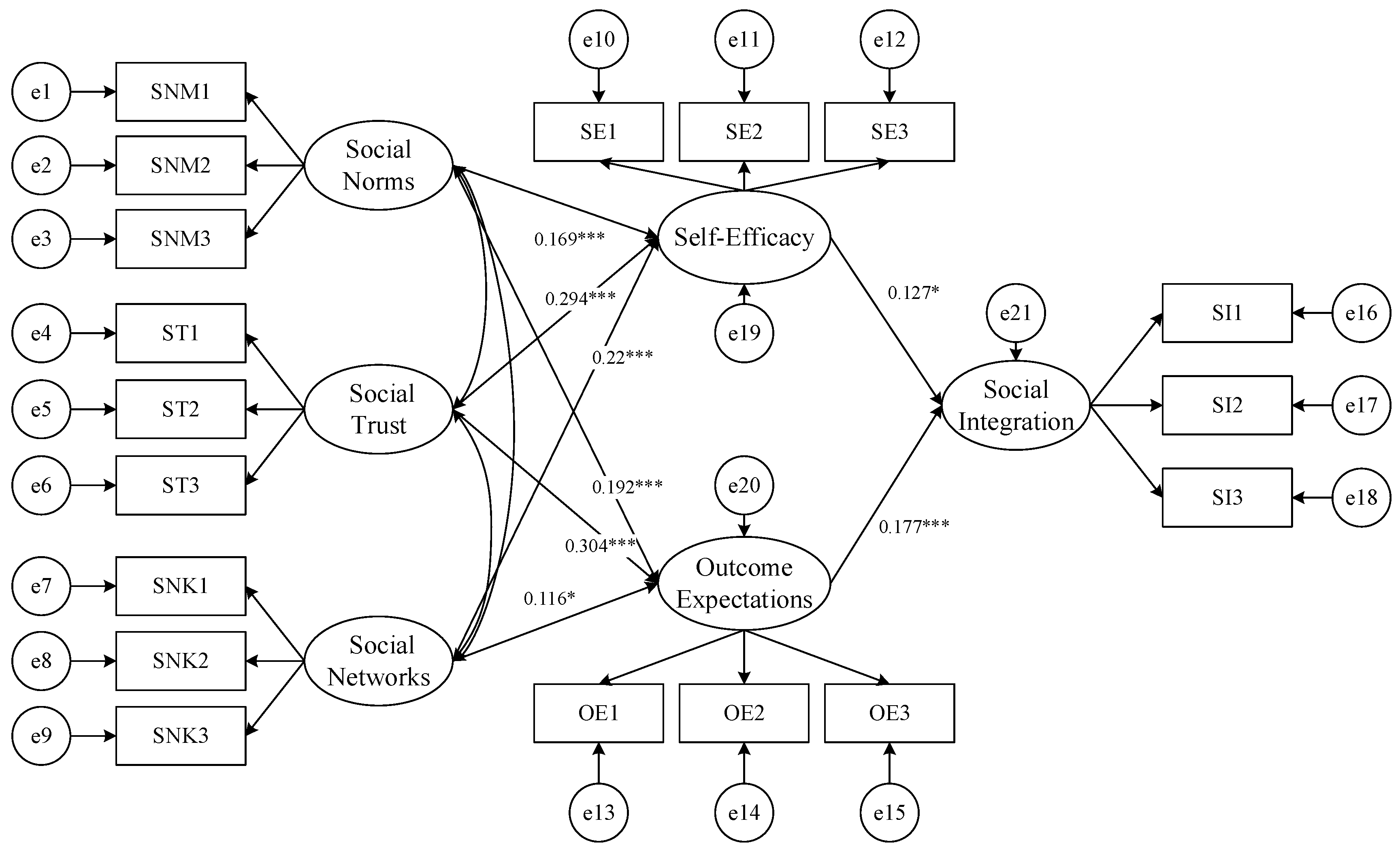

2.2. Research Framework

2.3. Research Hypotheses

2.3.1. Outcome Expectations and Social Integration

2.3.2. Self-Efficacy and Social Integration

2.3.3. Social Norms, Self-Efficacy, and Outcome Expectations

2.3.4. Social Trust, Self-Efficacy and Outcome Expectations

2.3.5. Social Networks, Self-Efficacy, and Outcome Expectations

3. Research Design and Data Collection

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Methodology

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

4.2. SEM

4.3. fsQCA Testing

4.3.1. Data Calibration

4.3.2. Necessity Analysis

4.3.3. Sufficiency Analysis of Condition Configurations

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary

6.2. Recommendations

6.3. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.; Shi, G.; Dong, Y. Effects of the Post-Relocation Support Policy on Livelihood Capital of the Reservoir Resettlers and Its Implications—A Study in Wujiang Sub-Stream of Yangtze River of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xie, J.; Jiao, T.; Su, Z. Research on the Livelihood Capital and Livelihood Strategies of Resettlement in China’s South-to-North Water Diversion Middle Line Project. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1396705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Yang, W.; Yun, J.; Zhang, Y. The Path of Social Integration of Resettlers in Poverty Alleviation Relocation: A Case Study of Dongchuan from Yunnan Plateau Mountainous Areas. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 110, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarenbeek, L. Relational Integration: From Integrating Resettlers to Integrating Social Relations. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2024, 50, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xu, H. Direct and Spillover Effects: How Do Community-Based Organizations Impact the Social Integration of Passive Resettlers? Sustainability 2024, 16, 4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Wang, X. Impact of Social Integration and Government Support on Ecological Imresettlers’ Vulnerability to Poverty. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2023, 30, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Xia, L. Research on Social Integration Structure and Path of Floating Population Based on Structural Equation Model: Evidence from China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Li, Y.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, Z. Community Support as a Driver for Social Integration in Ex-Situ Poverty Alleviation Relocation Communities: A Case Study in China. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, W. The Sustainable Development Assessment of Reservoir Resettlement Based on a BP Neural Network. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, J.-F.; Orange, D.; Habich-Sobiegalla, S.; Nguyen, V.T. Socialist Hydropower Governances Compared: Dams and Resettlement as Experienced by Dai and Thai Societies from the Sino-Vietnamese Borderlands. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Xu, L.; Wang, X. Ecological Compensation for Hydropower Resettlement in a Reservoir Wetland Based on Welfare Change in Tibet, China. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 96, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, Z. Place Attachment in the Ex-Situ Poverty Alleviation Relocation: Evidence from Different Poverty Alleviation Migrant Communities in Guizhou Province, China. Sust. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Z.; Long, D.; Jing, L.; Yang, M.; Wen, X. Ecological Resettlers’ Socio-Spatial Integration in Yinchuan City, China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, Z.; Wang, M.Y.; Huang, J.; Shi, G.; Song, L.; Sun, Z. Study on Social Integration Identification and Characteristics of Resettlers from “Yangtze River to Huaihe River” Project: A Time-Driven Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnside, P. Chinas 3 Gorges Dam—Fatal Project or Step Toward Modernization. World Dev. 1988, 16, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicourel, A.V. Collective Memory, A Fusion of Cognitive Mechanisms and Cultural Processes. Rev. Synth. 2015, 136, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Logic of Practice; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1990; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 300–531. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York City, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 208–253. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Zheng, X.; Sun, Y. Fostering Public Climate Change Discussions from a Social Interaction Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1258150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Qian, Q.K.; Liu, G.; Li, K.; Visscher, H.J.; Fu, X.; Wang, W. Multi-Level Social Capital Effects on Residents: Residents’ Cooperative Behavior in Neighborhood Renewal in China. Land Use Pol. 2025, 148, 107383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.-S. Perceived Social Support Moderates the Relationships between Variables in the Social Cognition Model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 35, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladbury, J.L.; Hinsz, V.B. How the Distribution of Member Expectations Influences Cooperation and Competition in Groups: A Social Relations Model Analysis of Social Dilemmas. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 44, 1502–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.K.; Maleku, A.; Lim, Y.; Kagotho, N.; Scott, J.; Ketchum, M.M. Financial Challenges and Capacity among African Refugees in the Southern USA: A Study of Socio-Demographic Differences. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 1529–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yao, K.; Liu, B.; Wang, F. A Livelihood Resilience Measurement Framework for Dam-Induced Displacement and Resettlement. Water 2020, 12, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannberg, A.; Sjogren, T. Conflicting Identities and Social Pressure: Effects on the Long-Run Evolution of Female Labour Supply. Oxf. Econ. Pap.-New Ser. 2015, 67, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchieri, C.; Dimant, E. Nudging with Care: The Risks and Benefits of Social Information. Public Choice 2022, 191, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwebu, K.L.; Wang, J.; Zifla, E. Can Warnings Curb the Spread of Fake News? The Interplay between Warning, Trust and Confirmation Bias. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 3552–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.S.; Amo, C.E.; Prochnow, T.; Heinrich, K.M. Exploring Social Networks Relative to Various Types of Exercise Self-Efficacy within CrossFit Participants. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 20, 1691–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, R.M.; Colombo, G.B.; Turner, L.; Dunham, Y.; Doyle, D.K.; Roy, E.M.; Giammanco, C.A. The Coevolution of Social Networks and Cognitive Dissonance. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2022, 9, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Du, J.; Yang, K.; Ge, Y.; Ma, Y.; Mao, H.; Xiang, M.; Wu, D. Relationship between Horizontal Collectivism and Social Network Influence among College Students: Mediating Effect of Self-Monitoring and Moderating Effect of Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1424223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, M.J.; Arnkoff, D.B.; Glass, C.R.; Ametrano, R.M.; Smith, J.Z. Expectations. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I.; Edelmann, N.; Haug, N. Defining Digital Transformation: Results from Expert Interviews. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, C.; Shi, G.; Xu, Y.; Mei, X.; Yan, D.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Lowell, Z. From Order to Reorder: Assessment of the Living Environment of Hydropower Resettlement for Just Energy Transition in China. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 5668–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, L.; Brouwer, J.; Jansen, E.; Crayen, C.; Hannover, B. Academic Self-Efficacy, Growth Mindsets, and University Students’ Integration in Academic and Social Support Networks. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 62, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, W.-L.; Yuan, Y.; Pu, X.; Ray, S.; Chen, C.C. Understanding Fintech Continuance: Perspectives from Self-Efficacy and ECT-IS Theories. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 120, 1659–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugert, P.; Greenaway, K.H.; Barth, M.; Büchner, R.; Eisentraut, S.; Fritsche, I. Collective Efficacy Increases Pro-Environmental Intentions through Increasing Self-Efficacy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Kreitewolf, J.; Kronick, R. The Relationship between Wellbeing, Self-Determination, and Resettlement Stress for Asylum-Seeking Mothers Attending an Ecosocial Community-Based Intervention: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongrain, P. With a Little Help from My Friends? The Impact of Social Networks on Citizens’ Forecasting Ability. OEr. J. Polit. Res. 2023, 62, 1320–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, K.; Grolleau, G.; Ibanez, L. Social Norms and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Review of the Evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helferich, M.; Thøgersen, J.; Bergquist, M. Direct and Mediated Impacts of Social Norms on Pro-Environmental Behavior. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 80, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Shi, G.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Y.; Dong, Y. Impact Assessment of the Implementation Effect of the Post-Relocation Support Policies of Rural Reservoir Resettlers’ Livelihoods in Energy Transition. Water 2023, 15, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, M.; Zuo, J.; Bartsch, K. Social Capital and Social Integration after Project-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: Exploring the Impact on Three Life Stages in the Three Gorges Project. Soc. Sci. J. 2023, 60, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sønderskov, K.M.; Dinesen, P.T. Trusting the State, Trusting Each Other? The Effect of Institutional Trust on Social Trust. Polit. Behav. 2016, 38, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilke, O.; Reimann, M.; Cook, K.S. Trust in Social Relations. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 47, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilt, B.; Gerkey, D. Dams and Population Displacement on China’s Upper Mekong River: Implications for Social Capital and Social–Ecological Resilience. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 36, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quetulio-Navarra, M.; Znidarsic, A.; Niehof, A. Gender Perspective on the Social Networks of Household Heads and Community Leaders after Involuntary Resettlement. Gend. Place Cult. 2017, 24, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, W.J.; Wills, J.A.; Jost, J.T.; Tucker, J.A.; Van Bavel, J.J. Emotion Shapes the Diffusion of Moralized Content in Social Networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7313–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, J. Social Capital, Exploitative and Exploratory Innovations: The Mediating Roles of Ego-Network Dynamics. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 126, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Chen, S.; Sun, J. Role of Non-Governmental Organizations in Post-Relocation Support of Reservoir Migrations in China: A Just Transition Perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1339953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Xiao, X.; Lv, Y.; Guan, X.; Wang, W. A Large-Scale Investigation of the Status of Out-Resettlers from the Three Gorges Area Based on the Production-Living-Social Security-Social Integration-Satisfaction Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galesic, M.; Barkoczi, D.; Berdahl, A.M.; Biro, D.; Carbone, G.; Giannoccaro, I.; Goldstone, R.L.; Gonzalez, C.; Kandler, A.; Kao, A.B.; et al. Beyond Collective Intelligence: Collective Adaptation. J. R. Soc. Interface 2023, 20, 20220736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landesmann, M.; Leitner, S.M. Various Domains of Integration of Refugees and Their Interrelationships: A Study of Recent Middle Eastern Refugee Inflows in Austria. Eur. J. Popul. 2025, 41, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragin, C.C.; Strand, S.I. Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis to Study Causal Order—Comment on Caren and Panofsky (2005). Sociol. Methods. Res. 2008, 36, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Strategies for Social Inquiry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 1–350. [Google Scholar]

- Fiss, P.C. Building Better Causal Theories: A Fuzzy Set Approach to Typologies in Organization Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Immigration, Fertility, and Human Capital: A Model of Economic Decline of the West. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2010, 26, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, K.; Ji, Y. Research on the Relationship between Social Capital and Sustainable Livelihood: Evidences from Reservoir Resettlers in the G Autonomous Prefecture, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1358386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomul, E.; Taslidere, E.; Almış, S.; Açıl, E. The Moderation Effect of Economic, Social and Cultural Status on Mediating Role of Adaptability and Intercultural Sensitivity in the Relationship between Self-Efficacy and Attitudes towards Imresettlers in Türkiye. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 19264–19282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, N.; Shulman, H.C.; McClaran, N. Changing Norms: A Meta-Analytic Integration of Research on Social Norms Appeals. Hum. Commun. Res. 2020, 46, 161–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziller, C.; Schlösser, T.; Schück, K.; Partos, K. Local Ties That Bind: The Role of Perceived Neighborhood Cohesion and Disorder for Imresettlers’ National Identification. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 112, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; He, W.; Kong, Y.; Shen, J.; Yuan, L.; Stephen Ramsey, T. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Water Sustainability of Cities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt Based on the Perspectives of Quantity-Quality-Benefit. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Measurement Indicators | Measurement Items | Measurement Standard | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome expectations (OE) | OE1 | Living locally helps to enjoy better services. | completely disagree = 1; disagree = 2; fairly agree = 3; agree = 4; completely agree = 5 | Ladbury & Hinsz [24] Constantino et al. [33] Mergel et al. [34] Zhao et al. [35] |

| OE2 | Living locally helps increase income. | |||

| OE3 | Adapting to local cultural customs contributes to the improvement of life quality. | |||

| Self-efficacy (SE) | SE1 | I’m confident that I’ll be able to adapt to the local living environment. | Zander et al. [36] Shiau et al. [37] Jugert et al. [38] Wu et al. [39] | |

| SE2 | I believe that I am able to restore my livelihood locally. | |||

| SE3 | I’m confident that I’ll fit in with the local culture and customs. | |||

| Social norms (SNM) | SNM1 | The policies and supporting systems introduced by the government are conducive to the integration of resettlers into local life. | Mongrain [40] Farrow et al. [41] Helferich et al. [42] Liang et al. [43] | |

| SNM2 | Village regulations and civil agreements contribute to harmonious coexistence among villagers. | |||

| SNM3 | Social morality helps reservoir resettlers receive assistance. | |||

| Social trust (ST) | ST1 | Village officials are trustworthy. | Wang et al. [44] Sønderskov & Dinesen [45] Schilke [46] Tilt & Gerkey [47] | |

| ST2 | Local residents are trustworthy. | |||

| ST3 | Relatives and friends are trustworthy. | |||

| Social network (SNK) | SNK1 | The number of visits to relatives and friends during the Spring Festival | Five categories of actual data, from lowest to highest, 1–5, are assigned as follows: 0 = 1; 1–5 = 2; 6–10 = 3; 11–15 = 4; 16 and above = 5. | Quetulio-Navarra et al. [48] Brady et al. [49] Yan & Guan [50] Hong et al. [51] |

| SNK2 | The likelihood of receiving help from relatives and friends when encountering difficulties | definitely impossible = 1; impossible = 2; possible = 3; probable = 4; totally probable = 5 | ||

| SNK3 | Relationships with relatives and friends | extremely distant = 1; distant = 2; fairly close = 3; close = 4; extremely close = 5 | ||

| Social integration (SI) | SI1 | Satisfaction with local infrastructure | completely disagree = 1; disagree = 2; fairly agree = 3; agree = 4; completely agree = 5 | Shangguan et al. [14] Peng et al. [52] Galesic et al. [53] Landesmann & Leitner [54] |

| SI2 | The average annual household income | Five categories of actual data, from lowest to highest, 1–5, are assigned as follows: Less than ¥20,000 = 1; ¥20,000–40,000 = 2; ¥50,000–60,000 = 3; ¥70,000–80,000 = 4; Above ¥80,000 = 5. | ||

| SI3 | The degree of familiarity with local customs and traditions | completely unfamiliar = 1; unfamiliar = 2; fairly familiar = 3; familiar = 4; completely familiar = 5 |

| Collection Methods | Primary Sources | Detailed Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| In-depth interviews | Officials of the county resettlement management bureau, staff of resettlement areas, and representatives of resettlers | The interviews were conducted in three stages, covering the core content of the questionnaire. A total of 12 resettlement officials were interviewed (including 3 heads of the county resettlement bureau), 9 community workers, and representatives of 25 resettled families (including young and middle-aged individuals as well as the elderly). Additionally, 6 heads of social organizations were interviewed. The interviews were transcribed into approximately 58,000 words. |

| Questionnaire survey | Reservoir relocation families and local residents | The study utilized stratified random sampling in resettlement areas under the post-resettlement support evaluation project, with cross-validation to guarantee data reliability. |

| Non-participant observation | Public activities in resettlement communities, and daily interaction scenarios | Through longitudinal participatory observation, the research team documented migrant integration processes by engaging with 27 community events (e.g., deliberative meetings, cultural celebrations, vocational workshops), systematically recording ethnographic data in field journals. |

| Internal documents | County resettlement management bureau, resettlement community committee, and social organizations | (1) Policy documents: including The 14th Five-Year Plan for Post-Resettlement Support of Reservoir Migrants and other related support policies; (2) Administrative archives: including livelihood records of resettlement households and community assistance documentation; (3) Meeting minutes: Including thematic meetings like “resettlers’ integration progress conference” and “interdepartmental coordination sessions”. |

| External public information | Government official website, academic databases, and media reports | (1) Policy texts: provincial resettlement regulations and central government policies on reservoir resettlement support; (2) Research reports: social integration assessment studies published by universities and think tanks; (3) Media coverage: in-depth case studies of resettlers in mainstream news outlets. |

| Variables | Measurement Indicators | SFL | Overall Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE | OE1 | 0.88 | 3.901 | 1.22 |

| OE2 | 0.78 | |||

| OE3 | 0.779 | |||

| SE | SE1 | 0.921 | 4.127 | 1.064 |

| SE2 | 0.805 | |||

| SE3 | 0.768 | |||

| SNM | SNM1 | 0.942 | 4.097 | 1.113 |

| SNM2 | 0.793 | |||

| SNM3 | 0.78 | |||

| ST | ST1 | 0.917 | 3.819 | 1.131 |

| ST2 | 0.776 | |||

| ST3 | 0.772 | |||

| SNK | SNK1 | 0.944 | 4.146 | 1.067 |

| SNK2 | 0.771 | |||

| SNK3 | 0.77 | |||

| SI | SI1 | 0.924 | 3.935 | 1.195 |

| SI2 | 0.826 | |||

| SI3 | 0.837 |

| Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | OE | SE | SNM | ST | SNK | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE | 0.876 | 0.8548 | 0.6632 | 0.814 | |||||

| SE | 0.868 | 0.8719 | 0.6954 | 0.257 | 0.834 | ||||

| SNM | 0.875 | 0.8784 | 0.7082 | 0.402 | 0.311 | 0.842 | |||

| ST | 0.863 | 0.8634 | 0.6797 | 0.451 | 0.43 | 0.384 | 0.824 | ||

| SNK | 0.865 | 0.8701 | 0.6928 | 0.385 | 0.37 | 0.411 | 0.429 | 0.832 | |

| SI | 0.904 | 0.8976 | 0.7455 | 0.082 | 0.144 | 0.004 | 0.019 | 0.016 | 0.863 |

| Fitting Coefficient | Statistics | Optimality Criterion Values | Fit Situation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square value | 175.623 | - | |

| DF | 124 | - | |

| Chi-square/DF | 1.416 | <3 | excellent |

| GFI | 0.964 | >0.9 | excellent |

| AGFI | 0.951 | >0.9 | excellent |

| RMSEA | 0.028 | <0.08 | excellent |

| CFI | 0.991 | >0.9 | excellent |

| TLI | 0.989 | >0.9 | excellent |

| Paths | std. | UnStd. | S.E. | C.R. | p | Established or Not |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy→social integration | 0.127 | 0.145 | 0.058 | 2.526 | 0.012 | established |

| Outcome expectations→social integration | 0.177 | 0.25 | 0.069 | −3.621 | *** | established |

| Social norms→self-efficacy | 0.169 | 0.152 | 0.046 | 3.326 | *** | established |

| Social norms→outcome expectations | 0.192 | 0.141 | 0.037 | −3.757 | *** | established |

| Social trust→self-efficacy | 0.294 | 0.306 | 0.054 | 5.714 | *** | established |

| Social trust→outcome expectations | 0.304 | 0.255 | 0.043 | −5.87 | *** | established |

| Social networks→self-efficacy | 0.22 | 0.218 | 0.049 | 4.416 | *** | established |

| Social networks→outcome expectations | 0.116 | 0.093 | 0.039 | 2.399 | 0.016 | established |

| Condition Variables | Outcome Variables | Condition Variables | Outcome Variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | ||

| OE | 0.749 | 0.641 | ~OE | 0.492 | 0.750 |

| SE | 0.767 | 0.695 | ~SE | 0.514 | 0.713 |

| SNM | 0.820 | 0.669 | ~SNM | 0.429 | 0.719 |

| ST | 0.777 | 0.702 | ~ST | 0.495 | 0.689 |

| SNK | 0.868 | 0.678 | ~SNK | 0.382 | 0.702 |

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | |

| SE | ● | ⬤ | |||

| SNM | ● | ⬤ | |||

| ST | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ||

| SNK | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | |

| Consistency | 0.861 | 0.864 | 0.889 | 0.909 | 0.864 |

| Raw coverage | 0.329 | 0.359 | 0.362 | 0.240 | 0.349 |

| Unique coverage | 0.018 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.107 |

| Solution consistency | 0.834 | ||||

| Solution coverage | 0.540 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diao, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Su, Z. A Study on the Influencing Factors and Multiple Driving Paths of Social Integration of Reservoir Resettlers: An Empirical Analysis Based on SEM and fsQCA. Water 2025, 17, 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17071073

Diao L, Chen J, Chen J, Su Z. A Study on the Influencing Factors and Multiple Driving Paths of Social Integration of Reservoir Resettlers: An Empirical Analysis Based on SEM and fsQCA. Water. 2025; 17(7):1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17071073

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiao, Lili, Jiachuan Chen, Jihao Chen, and Zhaoxian Su. 2025. "A Study on the Influencing Factors and Multiple Driving Paths of Social Integration of Reservoir Resettlers: An Empirical Analysis Based on SEM and fsQCA" Water 17, no. 7: 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17071073

APA StyleDiao, L., Chen, J., Chen, J., & Su, Z. (2025). A Study on the Influencing Factors and Multiple Driving Paths of Social Integration of Reservoir Resettlers: An Empirical Analysis Based on SEM and fsQCA. Water, 17(7), 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17071073