Environmental Sustainability of Nanobubble Watering Through Life-Cycle Evidence and Eco-Innovation for Circular Farming Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modeling and Impact Assessment

2.2. Experimental Context and Data Source

2.3. Economic and Business Feasibility Assessment

2.3.1. Assessment Framework

2.3.2. Selection of Evaluation Criteria

2.3.3. Data Collection and Interview Protocol

2.3.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

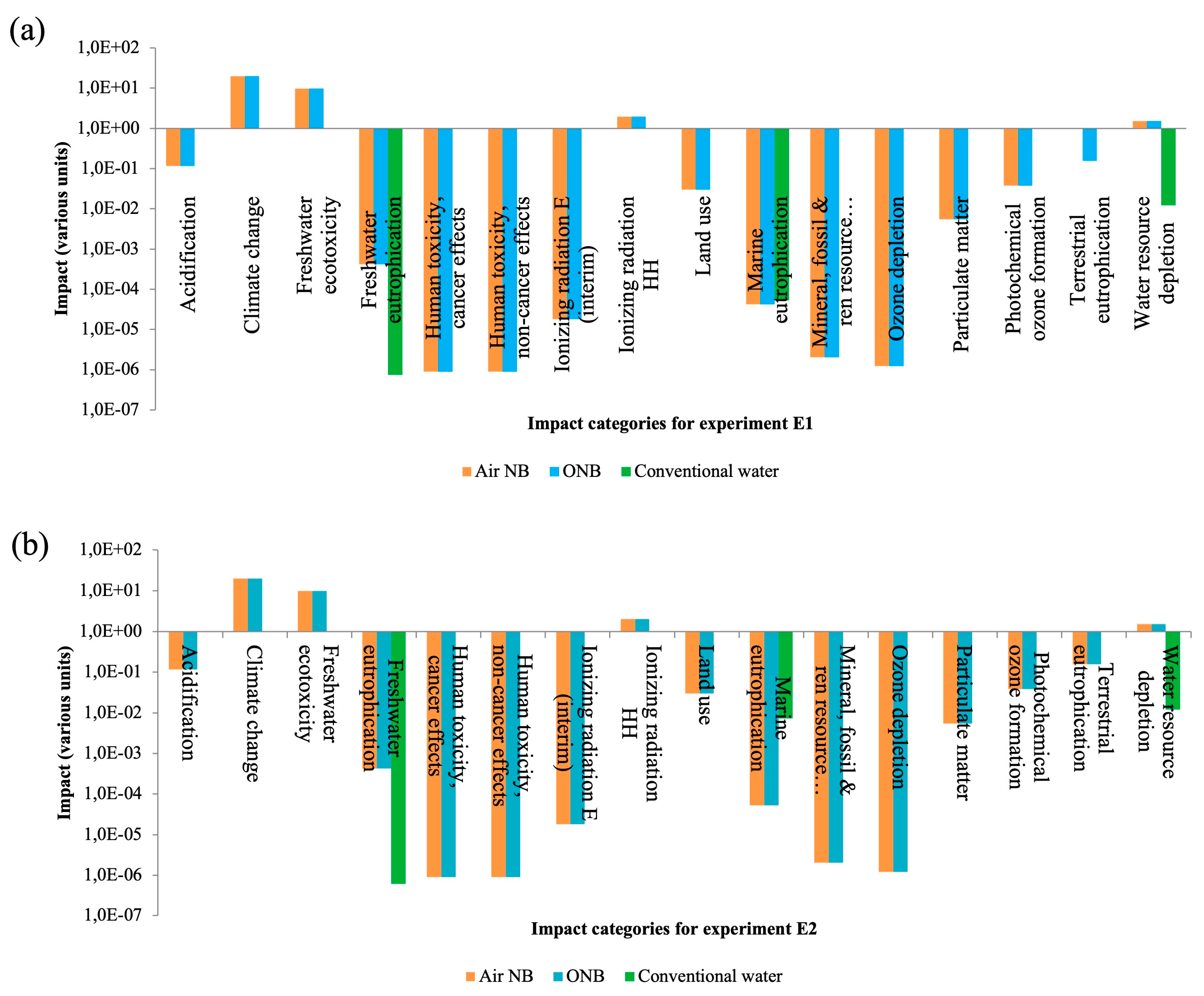

3.1. Energy Intensity and Environmental Performance

3.2. Soil-Type-Dependent Nutrient Trade-Offs

3.3. Expert-Based Feasibility Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Performance of NBSW

4.2. Sustainability Trade-Offs and Policy Relevance of NBSW Watering

5. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Water for Sustainable Food and Agriculture: A Report Produced for the G20 Presidency of Germany; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-92-5-109977-3. [Google Scholar]

- Levidow, L.; Zaccaria, D.; Maia, R.; Vivas, E.; Todorovic, M.; Scardigno, A. Improving water-efficient irrigation: Prospects and difficulties of innovative practices. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 146, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.J.; Jin, C.C.; Hu, S.G.; Pan, H.W.; Li, Y.P.; Wang, L.Y. Effect of aerated subsurface drip irrigation on soil ventilation of Solanum purpurei in greenhouse. J. Jiangsu Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2019, 40, 325–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ebina, K.; Shi, K.; Hirao, M.; Hashimoto, J.; Kawato, Y.; Kaneshiro, S.; Morimoto, T.; Koizumi, K.; Yoshikawa, H. Oxygen and air nanobubble water solution promote the growth of plants, fishes, and mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-S.; Han, M.; Kim, T.-I.; Lee, J.-W.; Kwak, D.-H. Effect of nanobubbles for improvement of water quality in freshwater: Flotation model simulation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 241, 116731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, J.; Liao, Z.; Ueda, Y.; Yoshikawa, K.; Zhang, G. Microbubbles for effective cleaning of metal surfaces without chemical agents. Langmuir 2020, 38, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Lyu, T.; Cooper, M.; Pan, G. Reducing arsenic toxicity using the interfacial oxygen nanobubble technology for sediment remediation. Water Res. 2021, 205, 117657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Dai, H.; Zhang, B.; Xiang, W.; Hu, Z.; Hu, J.; Li, P.; Yang, J.; et al. Nanobubbles promote nutrient utilization and plant growth in rice by upregulating nutrient uptake genes and stimulating growth hormone production. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Xi, H.; Zhou, Y. Review of micro-aeration hydrolysis acidification for the pretreatment of toxic and refractory organic wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.J.; Apul, O.G.; Schneider, O.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Westerhoff, P. Nanobubble technologies offer opportunities to improve water treatment. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmalkar, N.; Pacek, A.W.; Barigou, M. On the existence and stability of bulk nanobubbles. Langmuir 2018, 34, 10964–10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyluoglu, M.; Kim, D.; Zaker, Y.; Karanfil, T. Stability of oxygen nanobubbles under freshwater conditions. Water Res. 2021, 206, 117749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Povilaitis, A.; Arablousabet, Y. Transient Effects of Air and Oxygen Nanobubbles on Soil Moisture Retention and Soil-Substance Interactions in Compost-Amended Soil. Water 2025, 17, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission-Joint Research Centre-Institute for Environment and Sustainability. International Reference Life Cycle Data System (ILCD) Handbook-General Guide for Life Cycle Assessment-Detailed Guidance, 1st ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010; EUR 24708 EN; ISBN 978-92-79-19092-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Qin, J.; Duan, W.; Zou, S.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Rosa, L. Global Energy Use and Carbon Emissions from Irrigated Agriculture. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaparatne, S.; Doherty, Z.E.; Magdaleno, A.L.; Matula, E.E.; MacRae, J.D.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Apul, O.G. Effect of Air Nanobubbles on Oxygen Transfer, Oxygen Uptake, and Diversity of Aerobic Microbial Consortium in Activated Sludge Reactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalboussi, N.; Biard, Y.; Pradeleix, L.; Rapaport, A.; Sinfort, C.; Ait-mouheb, N. Life Cycle Assessment as Decision Support Tool for Water Reuse in Agriculture Irrigation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 836, 155486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Brás, I.; Ferreira, M.; Domingos, I.; Ferreira, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Green Space Irrigation Using Treated Wastewater: A Case Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennings, K. Redefining Innovation-Eco-Innovation Research and the Contribution from Ecological Economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J.; Rammer, C.; Rennings, K. Determinants of Eco-Innovations by Type of Environmental Impact-The Role of Regulatory Push/Pull, Technology Push and Market Pull. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 78, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Baleæentis, T.; Streimikiene, D.; Dabkiene, V.; Agnusdei, G.P. Circular Economy in Agriculture: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Grilli, L.; Groppi, A.; Marzano, R. Barriers and Drivers in the Adoption of Advanced Wastewater Treatment Technologies: A Comparative Analysis of Italian Utilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, S69–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Energy of the Republic of Lithuania. Power and Transport Sectors Are Key Areas for Action in Lithuania’s Pursuit of Energy Independence. 2023. Available online: https://enmin.lrv.lt/en/news/power-and-transport-sectors-are-key-areas-for-action-in-lithuanias-pursuit-of-energy-independence (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Aliyeva, K.; Aliyeva, A.; Aliyev, R.; Özdeşer, M. Application of Fuzzy Simple Additive Weighting Method in Group Decision-Making for Capital Investment. Axioms 2023, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, D.; Dias, A.C.; Gabarrell, X.; Arroja, L. Environmental assessment of an urban water system. Water Res. 2013, 47, 4194–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Moussavi, S.; Li, S.; Barutha, P.; Dvorak, B. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Small Water Resource Recovery Facilities: Comparison of Mechanical and Lagoon Systems. Water Res. 2022, 215, 118234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, W.; Zhang, Q.; Mihelcic, J.R. Life cycle environmental and economic implications of small drinking water systems. Water Res. 2018, 143, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission-Joint Research Centre-Institute for Environment and Sustainability. International Reference Life Cycle Data System (ILCD) Handbook: Recommendations for Life Cycle Impact Assessment in the European Context, 1st ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2011; EUR 24571 EN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybaczewska-Błażejowska, M.; Jezierski, D. Comparison of ReCiPe 2016, ILCD 2011, CML-IA baseline and IMPACT 2002+ LCIA methods: A case study based on the electricity consumption mix in Europe. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 1799–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Bastida, F.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Song, P.; Kuang, N.; Li, Y. Nanobubble Oxygenated Water Increases Crop Production via Soil Structure Improvement: The Perspective of Microbially Mediated Effects. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 282, 108263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.-D.; Niu, W.-Q.; Gu, X.-B.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, B.-J.; Zhao, Y. Crop Yield and Water Use Efficiency under Aerated Irrigation: A Meta-Analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 210, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.A.; Islam, T. Oxygenated Nanobubbles as a Sustainable Strategy to Strengthen Plant Health in Controlled Environment Agriculture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Tian, J.; Yan, X.; Yang, Z. Micro-Nano Oxygenated Irrigation Improves the Yield and Quality of Greenhouse Cucumbers Under-Film Drip Irrigation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Cayuela, J.A.; Mérida García, A.; Fernández García, I.; Rodríguez Díaz, J.A. Life Cycle Assessment of Large-Scale Solar Photovoltaic Irrigation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 954, 176813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T.; Wu, S.; Mortimer, R.J.G.; Pan, G. Nanobubble technology in environmental engineering: Revolutionization potential and challenges. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7175–7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arablousabet, Y.; Povilaitis, A. The Impact of Nanobubble Gases in Enhancing Soil Moisture, Nutrient Uptake Efficiency and Plant Growth: A Review. Water 2024, 16, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, E.J.; Richardson, M.D.; Gentimis, T.; McCalla, J.H. Analysis of Nanobubble-Oxygenated Water for Horticultural Applications. HortTechnology 2024, 34, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Ma, L. Micro-/Nanobubble Oxygenation Irrigation Enhances Soil Phosphorus Availability and Yield by Altering Soil Bacterial Community Abundance and Core Microbial Populations. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1497952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, T.; Pan, J.; Zhou, B.; Muhammad, T.; Zhou, C.; Li, Y. Micro-Nano Bubble Water Oxygation: Synergistically Improving Irrigation Water Use Efficiency, Crop Yield and Quality. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Wang, W.; Liang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Pan, H.; Wang, L.; Du, M. Effect of Nano-Bubble Irrigation on the Yield and Greenhouse Gas Warming Potential of Greenhouse Tomatoes. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, J.D.; Del Campo, T.V.; Acuña, A.A. Irrigation Water Treated with Oxygen Nanobubbles Decreases Irrigation Volume While Maintaining Turfgrass Quality in Central Chile. Grasses 2025, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Gao, J.; Liu, C.; Marhaba, T.; Zhang, W. Unveiling the Potential of Nanobubbles in Water: Impacts on Tomato’s Early Growth and Soil Properties. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 903, 166499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M. What Drives Eco-Innovation? A Review of an Emerging Literature. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 19, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terang, B.; Baruah, D.C. Techno-Economic and Environmental Assessment of Solar Photovoltaic, Diesel, and Electric Water Pumps for Irrigation in Assam, India. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizhisseri, M.I.; Sakr, M.; Maraqa, M.; Mohamed, M.M. A Comparative Bench Scale Study of Oxygen Transfer Dynamics Using Micro-Nano Bubbles and Conventional Aeration in Water Treatment Systems. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Doroodmand, M.M.; Nabi Bidhendi, G.; Torabian, A.; Mehrdadi, N. Efficient Wastewater Treatment via Aeration Through a Novel Nanobubble System in Sequence Batch Reactors. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 884353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, W.; Wu, S.; Mortimer, R.J.G.; Pan, G. Nanobubble Aeration Enhanced Wastewater Treatment and Bioenergy Generation in Constructed Wetlands Coupled with Microbial Fuel Cells. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 895, 165131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Peng, L.; Xu, Y.; Song, S.; Xie, G.-J.; Liu, Y.; Ni, B.-J. Optimizing Light Sources for Selective Growth of Purple Bacteria and Efficient Formation of Value-Added Products. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Haq, F.; Kiran, M.; Aziz, T. Circular economy and waste management: Transforming waste into resources for a sustainable future. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 17327–17346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| E1 (SCL Soil) | E2 (SL Soil) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 |

| Water input (L) | 69.75 | 69.75 | 69.75 | 69.75 |

| Electricity (kWh) | 4.58 | 0 | 4.4 | 0 |

| NO3− input (mg) | 420 | 292.5 | 420 | 292.5 |

| PO43− input (mg) | 8.9 | 15.35 | 8.9 | 15.35 |

| K+ input (mg) | 957 | 795 | 957 | 795 |

| Water leached (mL) | 3176 | 5094 | 119 | 4941 |

| NO3− leached (mg) | 295.23 | 525.3 | 26.13 | 2266.2 |

| PO43− leached (mg) | 2.24 | 2.26 | 0 | 1.87 |

| K+ leached (mg) | 58.6 | 95.7 | 0 | 167.4 |

| E1 | E2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact Category | Reference Unit | Air-NB Water Impact Value | ONB Water Impact Value | Conventional Watering Impact Value | Air-NB Water Impact Value | ONB Water Impact Value | Conventional Watering Impact Value |

| Acidification | molc H+ eq | 0.117 | 0.117 | 0 | 0.117 | 0.117 | 0 |

| Climate change | kg CO2 eq | 19.81 | 19.81 | 0 | 19.81 | 19.81 | 0 |

| Freshwater ecotoxicity | CTUe | 9.73 | 9.73 | 0 | 9.73 | 9.73 | 0 |

| Freshwater eutrophication | kg P eq | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 7.458 × 10−7 | 0.00042 | 0.0004 | 6.17 × 10−7 |

| Human toxicity, cancer effects | CTUh | 8.95 × 10−7 | 8.95 × 10−7 | 0 | 8.95 × 10−7 | 8.95 × 10−7 | 0 |

| Human toxicity, non-cancer effects | CTUh | 9.01 × 10−7 | 9.01 × 10−7 | 0 | 9.01075 × 10−7 | 9.010 × 10−7 | 0 |

| Ionizing radiation E (interim) | CTUe | 1.80 × 10−5 | 1.80 × 10−5 | 0 | 1.80 × 10−5 | 1.80 × 10−5 | 0 |

| Ionizing radiation HH | kBq U235 eq | 1.979 | 1.98 | 0 | 1.97 | 1.97 | 0 |

| Land use | kg C deficit | 0.029 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0 |

| Marine eutrophication | kg N eq | 4.2 × 10−5 | 4.2 × 10−5 | 5.3 × 10−5 | 4.2 × 10−5 | 4.2 × 10−5 | 7.3 × 10−3 |

| Mineral, fossil and ren resource depletion | kg Sb eq | 2.018 × 10−6 | 2.01 × 10−6 | 0 | 2.02 × 10−6 | 2.025 × 10−6 | 0 |

| Ozone depletion | kg CFC-11 eq | 1.219 × 10−6 | 1.21 × 10−6 | 0 | 1.22 × 10−6 | 1.22 × 10−6 | 0 |

| Particulate matter | kg PM2.5 eq | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0 |

| Photochemical ozone formation | kg NMVOC eq | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0 |

| Terrestrial eutrophication | molc N eq | −3.003 | 0.15 | −0.0009243 | 0.15 | 0.16 | −0.0009 |

| Water resource depletion | m3 water eq | 1.53 | 1.53 | 0.012124728 | 1.53 | 1.53 | 0.012 |

| The 9 Criteria Assessed for Each Question | Evaluation Questions | The Results of the Concordance Coefficient Calculation | The Results of the SAW | Expert |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Investment Cost | How would you describe the potential of NB technology for commercial use in agriculture or water management? | W = 0.470267, X2 = 33.85926 X2kr = 15.50731 | ~5.77 | EXP.4 |

| Operational and Maintenance Cost | What is your perception of the initial investment cost for adopting NB systems compared to existing technologies? | W =0.540741, X2 =38.93333 X2kr = 15.50731 | ~5.89 | EXP.3 |

| Market Adoption Potential | How do you assess the operational and maintenance requirements of NB technology? | W = 0.565329, X2 = 40.7037 X2kr = 15.50731 | ~5.93 | EXP.5 |

| Return on Investment (ROI) | How scalable is the technology for broader use (e.g., from laboratory to field level)? | W = 0.473868, X2 = 34.11852 X2kr = 15.50731 | ~5.79 | EXP.9 |

| Scalability and Adaptability | What risks or uncertainties (technical, market, or environmental) might limit adoption? | W = 0.539815, X2 = 38.86667 X2kr = 15.50731 | ~5.93 | EXP.9 |

| Risk and Reliability | How innovative do you consider NB technology to be, compared to other sustainable water-treatment solutions? | W =0.379321, X2 = 27.31111 X2kr = 15.50731 | ~5.67 | EXP.4 |

| Innovation and Competitive Advantage | How could EU green policy or funding programs influence NB technology uptake? | W = 0.471811, X2 = 33.97037 X2kr = 15.50731 | ~5.83 | EXP.7 |

| Environmental Co-Benefits | In your view, what factors could significantly improve the business case for NB technology in the next 5–10 years? | W = 0.628909, X2 = 45.28148 X2kr = 15.50731 | ~5.98 | EXP. 1 |

| Policy and Market Support | What do you see as the biggest barrier preventing NB technology from commercial scale-up? | W = 0.398251, X2 = 28.67407 X2kr = 15.50731 | ~5.68 | EXP.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arablousabet, Y.; Peyravi, B.; Povilaitis, A. Environmental Sustainability of Nanobubble Watering Through Life-Cycle Evidence and Eco-Innovation for Circular Farming Systems. Water 2025, 17, 3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243543

Arablousabet Y, Peyravi B, Povilaitis A. Environmental Sustainability of Nanobubble Watering Through Life-Cycle Evidence and Eco-Innovation for Circular Farming Systems. Water. 2025; 17(24):3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243543

Chicago/Turabian StyleArablousabet, Yeganeh, Bahman Peyravi, and Arvydas Povilaitis. 2025. "Environmental Sustainability of Nanobubble Watering Through Life-Cycle Evidence and Eco-Innovation for Circular Farming Systems" Water 17, no. 24: 3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243543

APA StyleArablousabet, Y., Peyravi, B., & Povilaitis, A. (2025). Environmental Sustainability of Nanobubble Watering Through Life-Cycle Evidence and Eco-Innovation for Circular Farming Systems. Water, 17(24), 3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243543