Tsunami Early Warning Systems: Enhancing Coastal Resilience Through Integrated Risk Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

- Hazard assessment quantifies the probability of flood events based on variables such as earthquake magnitude, ocean bathymetry, and coastal topography.

- Exposure analysis identifies people, infrastructure, and ecosystems located in tsunami-prone zones.

- Vulnerability assessment evaluates the capacity of these elements to resist or recover from inundation, considering factors such as construction standards, governance quality, and community resources.

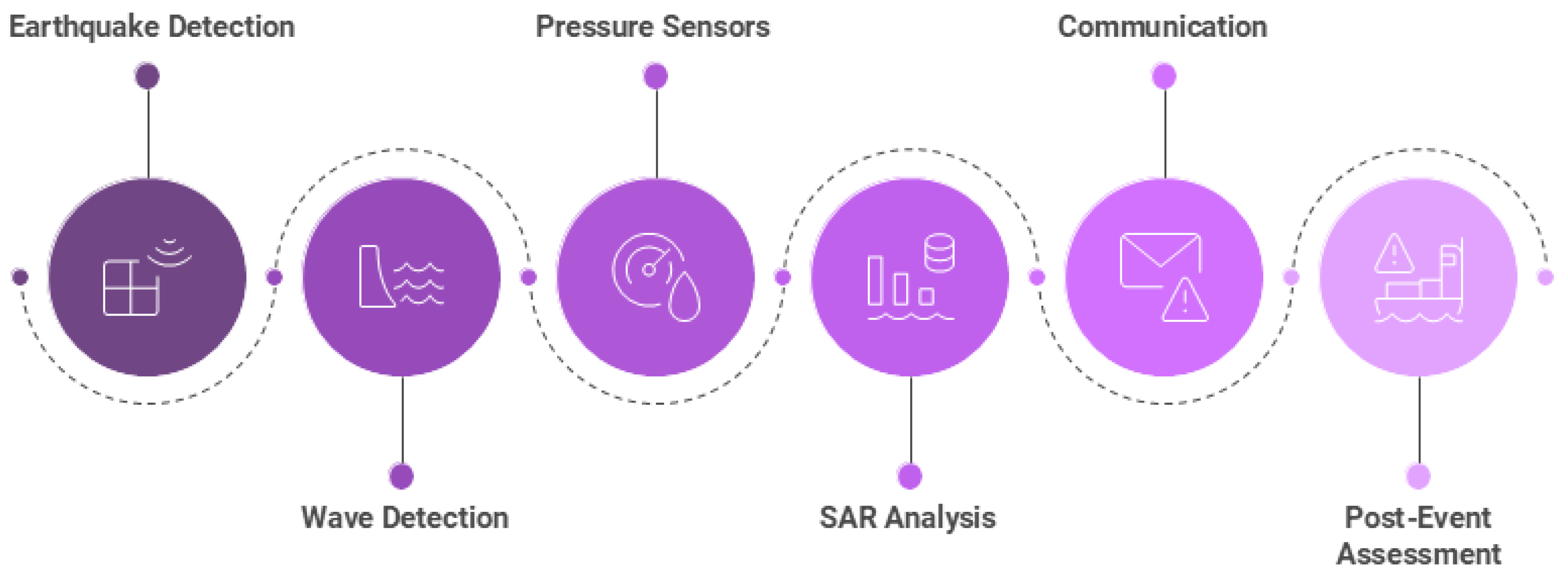

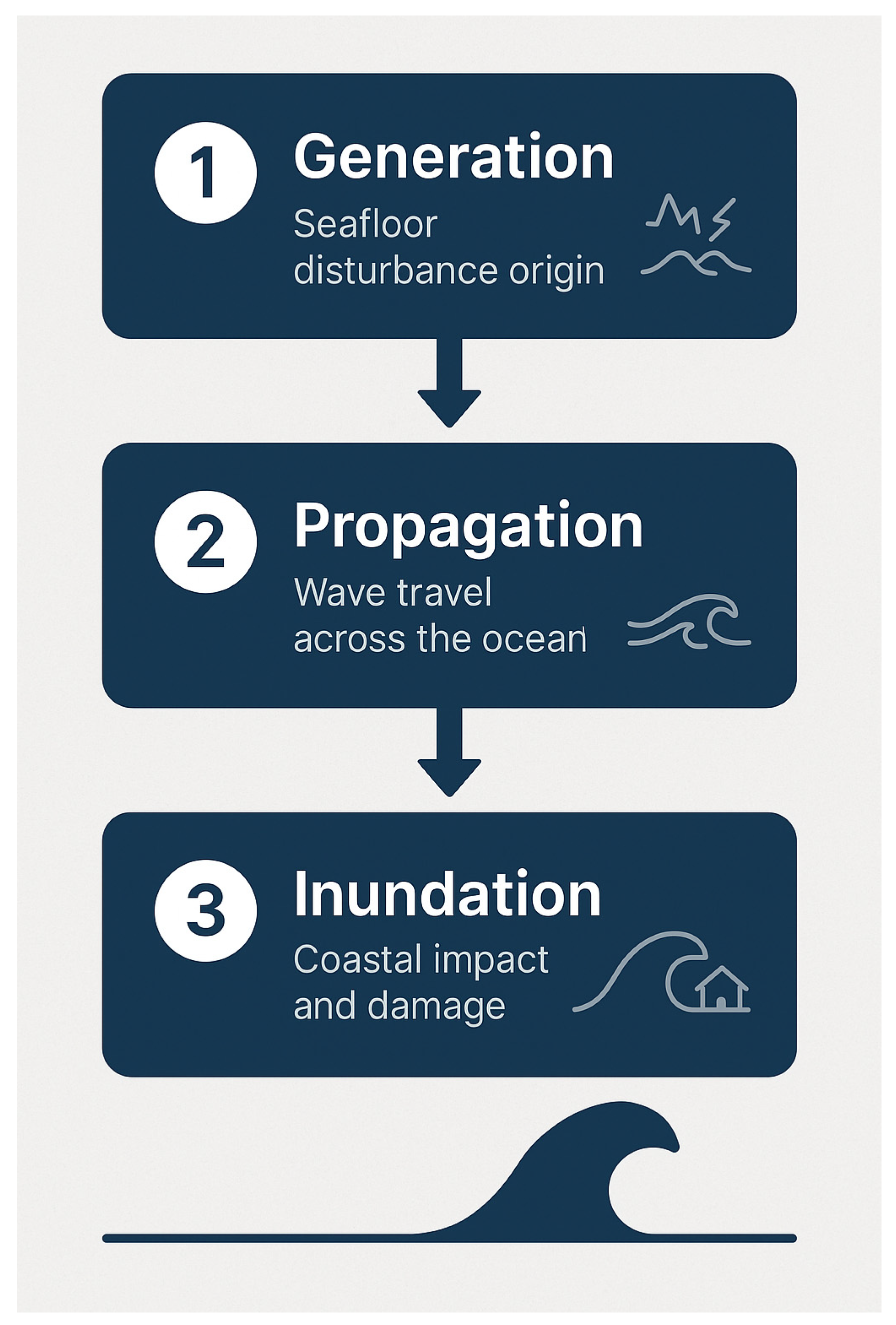

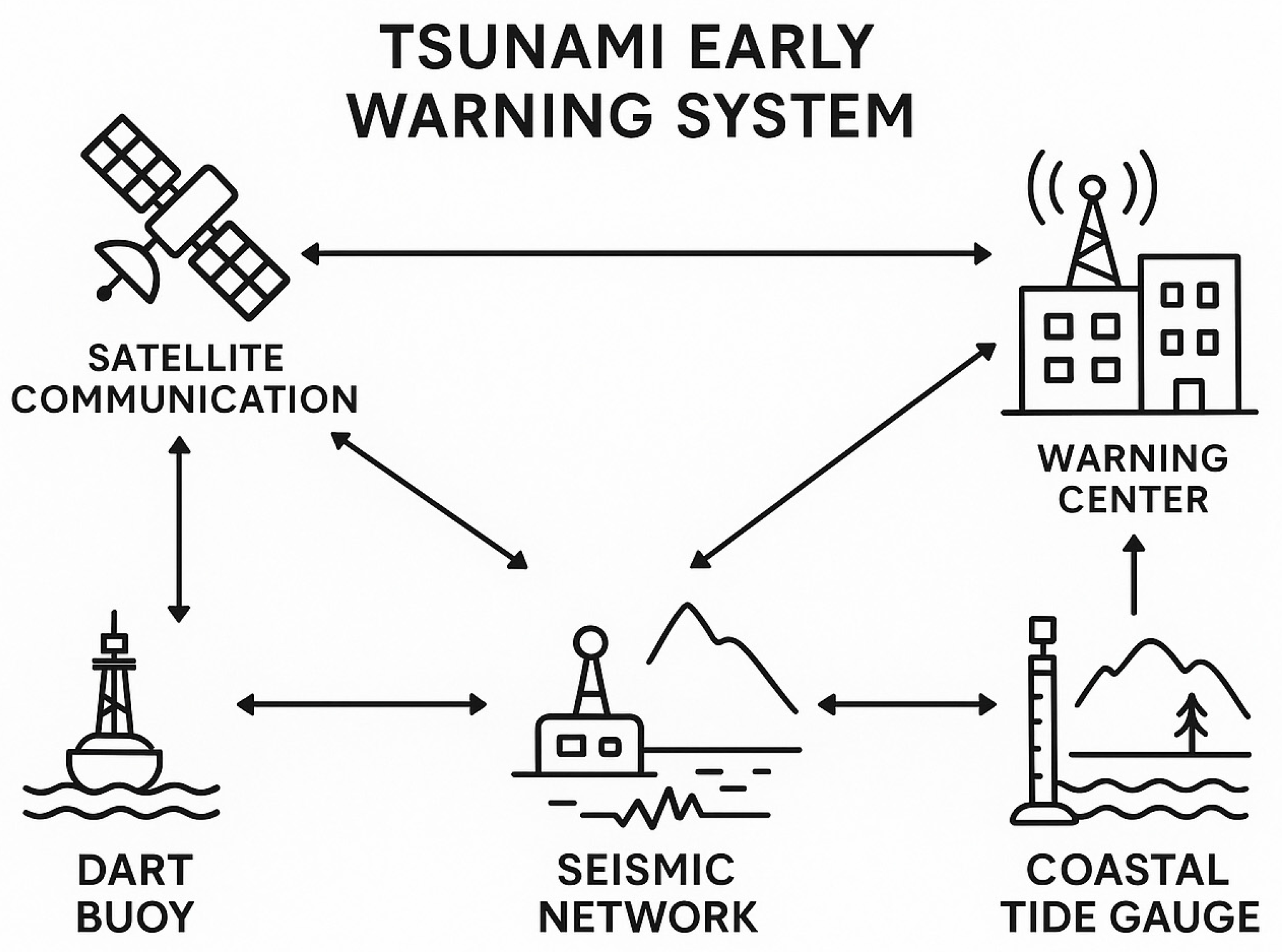

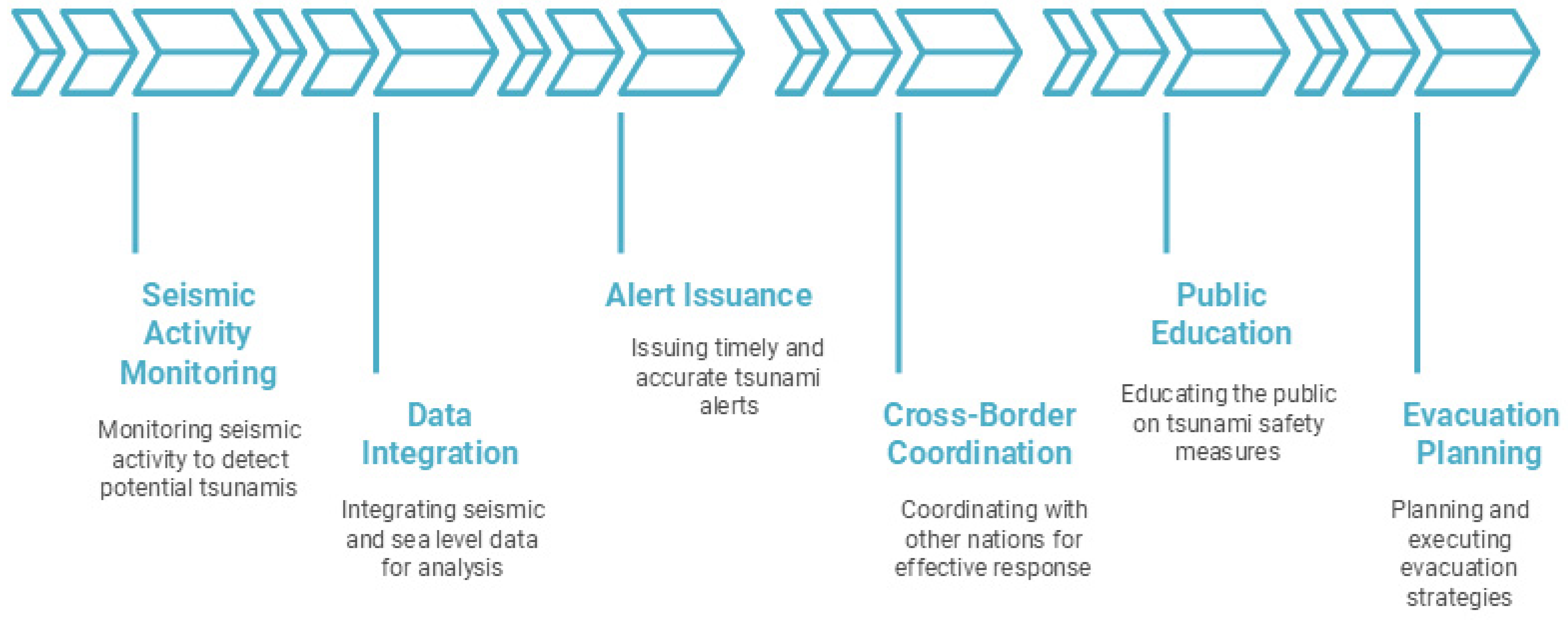

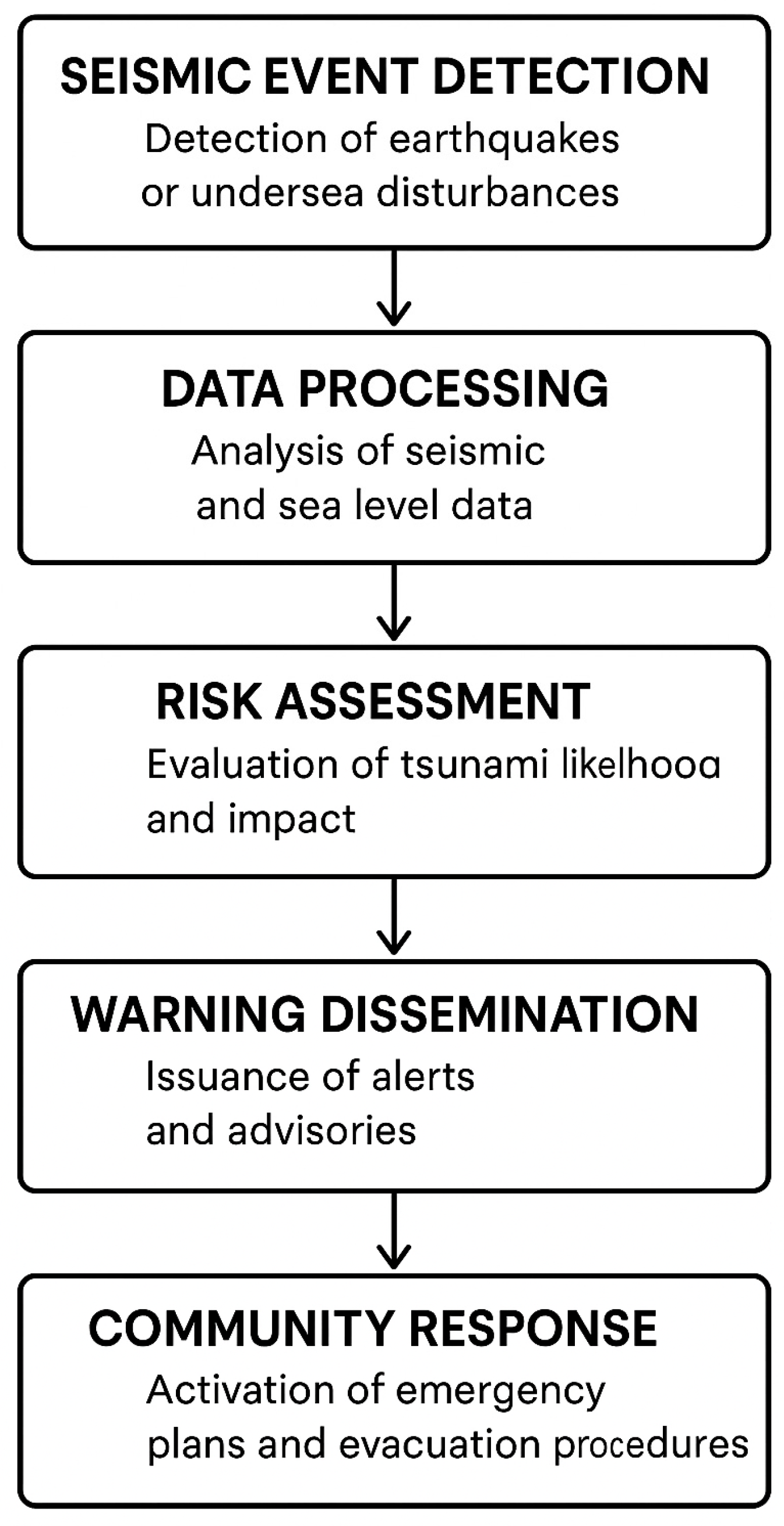

3. Tsunami Early Warning Systems

4. Challenges and Opportunities in Tsunami Early Warning Systems

5. Case Studies and Lessons Learned

6. Discussion

6.1. Significant Research Information

6.2. Practical and Theoretical Implications

6.3. Future Perspectives and Emerging Technologies

6.4. Limitations of the TEWS

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parsi, M.; Akbarpour Jannat, M.R. Tsunami Warning System Using of IoT. J. Ocean. 2020, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, J.; Daba, J.; Karam, H.; Abdallah, J. An Enhanced SAR-Based Tsunami Detection System. Int. J. Electr. Commun. Eng. 2014, 8, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, H. Advances for Tsunami Measurement Technologies and Its Applications. In Tsunami—A Growing Disaster; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rakowsky, N.; Androsov, A.; Fuchs, A.; Harig, S.; Immerz, A.; Danilov, S.; Hiller, W.; Schröter, J. Operational Tsunami Modelling with TsunAWI—Recent Developments and Applications. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 1629–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddock, R. Sensitivity Analysis of the Tsunami Warning Potential. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2003, 79, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A. The Role of IOC-UNESCO in Tsunami Early Warnings. In Tsunamis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 121–124. ISBN 9780123850539. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, E.N.; Mofjeld, H.O.; Titov, V.; Synolakis, C.E.; González, F.I.; Purvis, M.J.; Sharpe, J.E.; Mayberry, G.C.; Robertson, R.E.A. Tsunami: Scientific Frontiers, Mitigation, Forecasting and Policy Implications. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2006, 364, 1989–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, N.; Satake, K.; Cox, D.; Goda, K.; Catalan, P.A.; Ho, T.C.; Imamura, F.; Tomiczek, T.; Lynett, P.; Miyashita, T.; et al. Giant Tsunami Monitoring, Early Warning and Hazard Assessment. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; Suppasri, A.; Latcharote, P.; Otake, T. A Global Assessment of Tsunami Hazards Over the Last 400 Years; International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS): Sendai, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, A.T.; Jay, D.A.; Talke, S.A.; Pan, J. Global Water Level Variability Observed after the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’ Apai Volcanic Tsunami of 2022. Ocean Sci. 2023, 19, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omira, R.; Ramalho, R.S.; Kim, J.; González, P.J.; Kadri, U.; Miranda, J.M.; Carrilho, F.; Baptista, M.A. Global Tonga Tsunami Explained by a Fast-Moving Atmospheric Source. Nature 2022, 609, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate ADAPT Establecimiento de Sistemas de Alerta Rápida. In Sharing Adaptation Knowledge for a Climate-Resilient Europe; Climate-ADAPT: Berlin, Germany, 2025.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) Strategic Framework 2022–2025; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission. Quality Control of In Situ. Sea Level Observations; Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- UN/ISDR Platform for the Promotion of Early Warning (PPEW); UN Secretariat of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN/ISDR). Tercera Conferencia Internacional Sobre Alerta Temprana Del Concepto a La Acción. In Proceedings of the Desarrollo de Sistemas de Alerta Temprana: Lista de Comprobación, Bonn, Germany, 27 March 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Annunziato, A. Tsunami Detection Model for Sea Level Measurement Devices. Geociences 2022, 12, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masante, D.; Barantiev, D.; Destro, E.; Mastronunzio, M.; Paris, S.; Proietti, C.; Salvitti, V.; Santini, M. Multi-Hazard Early Warning System Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System (GDACS); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- García Montano, H.; Maltez Perez, N.J. Modelamientos de Los Parámetros Geofísicos Por Una Fuente Sísmica Capaz de Generar Un Tsunami En La Costa de Pochomil, Nicaragua. Rev. Cient. FAREM-Estelí 2022, 11, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Late Lessons from Early Warnings II—Summary; EEA Report No 1/2013; European Environment Agency (EEA): Copenhagen, Denmark, 22 January 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Meteorológica Mundial (OMM). Organización Meteorológica Mundial, 2021; Organización Meteorológica Mundial, 201521, OMM-N° 1150: Suiza 201521; Organización Meteorológica Mundial (OMM): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-92-63-31150-4. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, M.; Palma, L.; Belli, A.; Sabbatini, L.; Pierleoni, P. Recent Advances in Internet of Things Solutions for Early Warning: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, D.; Venugopal, M.; Roy, D.; Rajendran, K.; Guillas, S.; Dias, F. Uncertainties in the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman Source through Nonlinear Inversion of Tsunami Waves. Proc. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 473, 20170353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamlington, B.D.; Leben, R.R.; Godin, O.A.; Gica, E.; Titov, V.V.; Haines, B.J.; Desai, S.D. Could Satellite Altimetry Have Improved Early Detection and Warning of the 2011 Tohoku Tsunami? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardina, V.; Weinstein, S.; Koyanagi, K. Baseline Assessment of the Importance of Contributions from Regional Seismic Networks to the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center’s Operations. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2020, 91, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinoshima, F.; Oishi, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Furumura, T.; Imamura, F. Early Forecasting of Tsunami Inundation from Tsunami and Geodetic Data with Convolutional Neural Networks. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardi, A.; Bletery, Q.; Rouet-Leduc, B.; Ampuero, J.-P.; Juhel, K. Instantaneous Tracking of Earthquake Growth with Elastogravity Signals. Nature 2022, 606, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrentiev, M.; Lysakov, K.; Marchuk, A.; Oblaukhov, K. Fundamentals of Fast Tsunami Wave Parameter Determination Technology for Hazard Mitigation. Sensors 2022, 22, 7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federación Internacional de Sociedades de la Cruz Roja y de la Media Luna Roja. Sistemas Comunitarios de Alerta Temprana: Principios Rectores. 2012. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/es/publication/sistemas-comunitarios-de-alerta-temprana-principios-rectores (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Schiermeier, Q.; Witze, A. Tsunami Watch. Nature 2009, 462, 968–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmar, A.; Annunziato, A.; Boccardo, P.; Tonolo, F.G.; Wania, A. Tsunami Modeling and Satellite-Based Emergency Mapping: Workflow Integration Opportunities. Geosciences 2019, 9, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, K. Tsunami Warning System with Sea Surface Features Derived from Altimeter Onboard Satellites. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, V.; Ravanelli, M.; Liu, H.; Bortnik, J. Deep Learning Driven Detection of Tsunami Related Internal Gravity: A Path towards Open-Ocean Natural Hazards Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 3750–3755. [Google Scholar]

- Muenchmeyer, J.; Bindi, D.; Leser, U.; Tilmann, F. The Transformer Earthquake Alerting Model: A New Versatile Approach to earthquake Early Warning. Geophys. J. Int. 2021, 225, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva, J.; Lorito, S.; Volpe, M.; Romano, F.; Tonini, R.; Perfetti, P.; Bernardi, F.; Taroni, M.; Scala, A.; Babeyko, A.; et al. Probabilistic Tsunami Forecasting for Early Warning. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minson, S.E.; Brooks, B.A.; Glennie, C.L.; Murray, J.R.; Langbein, J.O.; Owen, S.E.; Heaton, T.H.; Iannucci, R.A.; Hauser, D.L. Crowdsourced Earthquake Early Warning. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusman, A.; Tanioka, Y.; MacInnes, B.T.; Tsushima, H. A Methodology for Near-Field Tsunami Inundation Forecasting: Application the 2011 Tohoku Tsunami. J. Geophys. Res. Solid. Earth 2014, 119, 8186–8206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, M.; Viroulet, S.; Gylfadottir, S.S.; Fellin, W.; Lovholt, F. Granular Porous Landslide Tsunami Modelling—The 2014 Lake Askja Flank. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.J.; LeVeque, R.J. Towards Adaptive Simulations of Dispersive Tsunami Propagation from an Asteroid Impact. In Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians, Helsinki, Finland, 3–6 July 2022; pp. 5056–5071. [Google Scholar]

- Savastano, G.; Komjathy, A.; Verkhoglyadova, O.; Mazzoni, A.; Crespi, M.; Wei, Y.; Mannucci, A.J. Real-Time Detection of Tsunami Ionospheric Disturbances with a Stand-Alone GNSS Receiver: A Preliminary Feasibility Demonstration. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearnley, C.J.; Dixon, D. Editorial: Early Warning Systems for Pandemics: Lessons Learned from natural Hazards. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirianna, B.; Robert, S.T.; Cinthia, A.; Miguel, A.; Orlando, C.V.; Cisneros, A.; Monica, C.I.; Adama, D.; Leon, L.; Giorgio, M.; et al. Opportunities and Challenges for People-Centered-Hazard Early Warning Systems: Perspectives from the Global South. iScience 2025, 28, 112353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.E.; Lawson, V.R.; Kaiser, L.; Potter, S.H.; Johnston, D. Understanding Mariners’ Tsunami Information Needs and Decision-Making: A Post-Event Case Study of the 2022 Tonga Eruption and Tsunami. iScience 2025, 28, 111801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhruddin, B.; Clark, H.; Robinson, L.; Hieber-Girardet, L. Should I Stay or Should I Go Now? Why Risk Communication Is the Critical in Disaster Risk Reduction. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 8, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, H.; Itatani, T.; Kaganoi, S.; Okamura, A.; Horiike, R.; Yamasaki, M. Needs of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Geographic of Emergency Shelters Suitable for Vulnerable People during A Tsunami. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grezio, A.; Anzidei, M.; Baglione, E.; Brizuela, B.; Di Manna, P.; Selva, J.; Taroni, M.; Tonini, R.; Vecchio, A. Including Sea-Level Rise and Vertical Land Movements in Probabilistic Hazard Assessment for the Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G.; Wang, Z.; Qu, M.; Hu, S. Integrated Optimization of Emergency Evacuation Routing for Dam-Induced Flooding: A Coupled Flood-Road Network Modeling Approach. Appl. Sci. Based 2025, 15, 4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiozaki, D.; Hashimoto, Y. System Development for Tsunami Evacuation Drill Using ICT and Tsunami Simulation Data. J. Disaster Res. 2024, 19, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo Arias, J.; Bronfman, N.C.; Cisternas, P.C.; Repetto, P.B. Hazard Proximity and Risk Perception of Tsunamis in Coastal Cities: Are Able to Identify Their Risk? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massazza, A.; Brewin, C.R.; Joffe, H. Feelings, Thoughts, and Behaviors During Disaster. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Rebelo, F.; He, R.; Noriega, P.; Vilar, E.; Wang, Z. Using virtual reality to explore the effect of multimodal alarms on human emergency evacuation behaviors. Virtual Real. 2025, 29, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Aldrich, D.P. Substitute or Complement? How Social Capital, Age and Socioeconomic Interacted to Impact Mortality in Japan’s 3/11 Tsunami. SSM-Popul. Health 2019, 7, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witvorapong, N.; Muttarak, R.; Pothisiri, W. Social Participation and Disaster Risk Reduction Behaviors in Tsunami Areas. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, F.; Jibiki, Y.; Sasaki, D.; Pelupessy, D.; Zulys, A.; Imamura, F. People’s Response to Potential Natural Hazard-Triggered Technological after a Sudden-Onset Earthquake in Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner-Stephen, P.; Wallace, A.; Hawtin, K.; Al-Nuaimi, G.; Tran, A.; Le Mozo, T.; Lloyd, M. Reducing Cost While Increasing the Resilience & Effectiveness of tsunami Early Warning Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–20 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 487–494. [Google Scholar]

- Alamdar, F.; Kalantari, M.; Rajabifard, A. Understanding the Provision of Multi-Agency Sensor Information in disaster Management: A Case Study on the Australian State of Victoria. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 22, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baytiyeh, H.; Naja, M. Promoting Earthquake Disaster Mitigation in Lebanon through Civic. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2013, 22, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagra, P.; Quintana, C. Disaster Governance for Community Resilience in Coastal Towns: Chilean Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulia, I.E.; Ueda, N.; Miyoshi, T.; Gusman, A.R.; Satake, K. Machine Learning-Based Tsunami Inundation Prediction Derived from offshore Observations. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugondo, R.A.; Machbub, C. P-Wave Detection Using Deep Learning in Time and Frequency Domain for imbalanced Dataset. Helyon 2021, 7, e08605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.S.; Sandeep, S.; Nandhini, D.; Amutha, S. Hybrid Quantum Neural Networks: Harnessing Dressed Quantum Circuits for Enhanced Tsunami Prediction via Earthquake Data Fusion. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2025, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.; Weber, R.; Wilson, K.; Cummins, P. From Offshore to Onshore Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard Assessment via efficient Monte Carlo Sampling. Geophys. J. Int. 2022, 230, 1630–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Konuma, T. Problem of Present Tsunami Warning System Indicated by the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. In Proceedings of the Coastal Engineering, Melbourne, Australia, 18–20 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blackford, M.E. Early Warning Systems for Tsunami—An Overview BT—Early Warning Systems for Natural Disaster Reduction. In Early Warning Systems for Natural Disaster Reduction; Zschau, J., Küppers, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 535–536. ISBN 978-3-642-55903-7. [Google Scholar]

- Register, C.; Escaleras, M. Mitigating Natural Disasters through Collective Action: The Effectiveness of Tsunami Early Warnings. South Econ. J. 2008, 74, 1017–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiba, M.; Ozaki, T. Early Warning for Geological Disasters Earthquake Early Warning and Tsunami Warning of the Japan Meteorological Agency, and Their Performance in the 2011 off the Pacific Coast of Tohoku Earthquake (Mw 9.0); Wenzel, F., Zschau, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-3-642-12233-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sheenu, P. Advance Prediction of Tsunami by Radio Methods. Int. J. Innov. Eng. Technol. (IJIET) 2015, 5, 207–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, G. Risk-Informed Tsunami Warnings. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2018, 456, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necmioglu, O.; Heidarzadeh, M.; Vougioukalakis, G.E.; Selva, J. Landslide Induced Tsunami Hazard at Volcanoes: The Case of Santorini. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2023, 180, 1811–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasa Kumar, T.; Manneela, S. A Review of the Progress, Challenges and Future Trends in Tsunami Early Warning Systems. J. Geol. Soc. India 2021, 97, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, I.; Ghosh, S.; Dash, I.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Review of Tsunami Early Warning System and Coastal Resilience with a Focus on Indian Ocean. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2022, 14, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.G.; Birkland, T.; Wallace, W.A.; Herabat, P. Socio-Technological Systems Integration to Support Tsunami Warning and Evacuation. SSRN Electron. J. 2011, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächter, J.; Babeyko, A.; Fleischer, J.; Haner, R.; Hammitzsch, M.; Kloth, A.; Lendholt, M. Development of Tsunami Early Warning Systems and Future Challenges. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 1923–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reißland, S.; Herrnkind, S.; Guenther, M.; Babeyko, A.; Comoglu, M.; Hammitzsch, M. Experiences Integrating Autonomous Components and Legacy Systems into Tsunami Early Warning Systems. In Proceedings of the General Assembly European Geosciences Union, Vienna, Austria, 22–27 April 2012; p. 10053. [Google Scholar]

- Catalán, P.; Gubler, A.; Cañas, J.; Zúñiga, C.; Zelaya, C.; Pizarro, L.; Valdes, C.; Mena, R.; Toledo, E.; Cienfuegos, R. Design and Operational Implementation of the Integrated Tsunami Forecast and Warning System in Chile (SIPAT). Coast. Eng. J. 2020, 62, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatenoux, B.; Peduzzi, P. Impacts from the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami: Analysing the Potential Protecting Role of Environmental Features. Nat. Hazards 2007, 40, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. User Workshop of the Copernicus Emergency Management Service—Summary Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Villagra, P.; Herrmann, M.G.; Quintana, C.; Sepúlveda, R.D. Community Resilience to Tsunamis along the Southeastern Pacific: A Multivariate Approach Incorporating Physical, Environmental, and Social Indicators. Nat. Hazards 2017, 88, 1087–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalal, D. A Conceptual Framework for Evaluating Tsunami Resilience. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 56, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskin, J.; Wang, Y.M. Fifty-Year Resilience Strategies for Coastal Communities at Risk for Tsunamis. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, D. Coastal Resilience: New Perspectives of Spatial and Productive Development for the Chilean Caletas Exposed to Tsunami Risk. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 18, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadian, S.D.; Khadijah, U.L.S.; Saepudin, E.; Budiono, A.; Yuliawati, A.K. Community Participation In Tsunami Early Warning System In Pangandaran. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Earth Hazard And disasterDisaster Mitigation (ISEDM), Bandung, Indonesia, 11–12 October 2016; Meilano, I., Zulfakriza, Eds.; AMER INST PHYSICS: Melville, Australia, 2017; Volume 1857. [Google Scholar]

- Pamuji, A.K.; Retno Susilorini, R.M.I.; Ismail, A.; Amasto, A.H. The Effectiveness of Mobile Application of Earthquake and Tsunami Early Warning System in Community Based Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 2979–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumy, D.; McBride, S.; von Hillebrandt-Andrade, C.; Kohler, M.; Orcutt, J.; Kodaira, S.; Moran, K.; McNamara, D.; Hori, T.; Vanacore, E.; et al. Long-Term Ocean Observing Coupled with Community Engagement Improves Tsunami Early Warning. Oceanography 2021, 34, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Goda, K. Hazard and Risk-Based Tsunami Early Warning Algorithms for Ocean Bottom Sensor S-Net System in Tohoku, Japan, Using Sequential Multiple Linear Regression. Geosciences 2022, 12, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, A.R.; Bayindir, C.; Ozaydin, F.; Altintas, A.A. The Predictability of the 30 October 2020 İzmir-Samos Tsunami Hydrodynamics and Enhancement of Its Early Warning Time by LSTM Deep Learning Network. Water 2023, 15, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Technological and Scientific Limitations | Integration with Risk Management | Socioeconomic Factors | Real-Time Data and AI Advances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Precision and DataPrecision & Data | Uncertain offshore seismic and pressure data; sea level sensors often the only viable option in regions lacking DART buoys | Delayed or ambiguous evacuation instructions if detection is incomplete | Unequal access to official alerts and local calibration limitations | Automated multi-sensor fusion, including tide gauges, improves confirmation speed and geographic specificity |

| Modeling Challenges | Non-linear tsunami dynamics hard to model | Static inundation maps limit adaptive response | Limited capacity for high-resolution modeling | Real-time data assimilation updates forecasts |

| Sensor Reliability | Offshore sensors face failure, latency, biofouling | Warning content must fit local context | Community trust and social networks matter | Edge computing lowers detection latency |

| Emerging Technologies | GNSS, radar, ionosphere still limited operationally | Dynamic evacuation routing needs reliable networks | Digital divide limits alert reach | IoT and 5G enable dense coastal sensing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perez-Rodriguez, F.-J.; Otero-Mateo, M.; Batista, M.; Ramirez-Peña, M. Tsunami Early Warning Systems: Enhancing Coastal Resilience Through Integrated Risk Management. Water 2025, 17, 3489. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243489

Perez-Rodriguez F-J, Otero-Mateo M, Batista M, Ramirez-Peña M. Tsunami Early Warning Systems: Enhancing Coastal Resilience Through Integrated Risk Management. Water. 2025; 17(24):3489. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243489

Chicago/Turabian StylePerez-Rodriguez, Francisco-Javier, Manuel Otero-Mateo, Moises Batista, and Magdalena Ramirez-Peña. 2025. "Tsunami Early Warning Systems: Enhancing Coastal Resilience Through Integrated Risk Management" Water 17, no. 24: 3489. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243489

APA StylePerez-Rodriguez, F.-J., Otero-Mateo, M., Batista, M., & Ramirez-Peña, M. (2025). Tsunami Early Warning Systems: Enhancing Coastal Resilience Through Integrated Risk Management. Water, 17(24), 3489. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243489