Experimental Study on Alternating Vacuum–Electroosmosis Treatment for Dredged Sludges

Abstract

1. Introduction

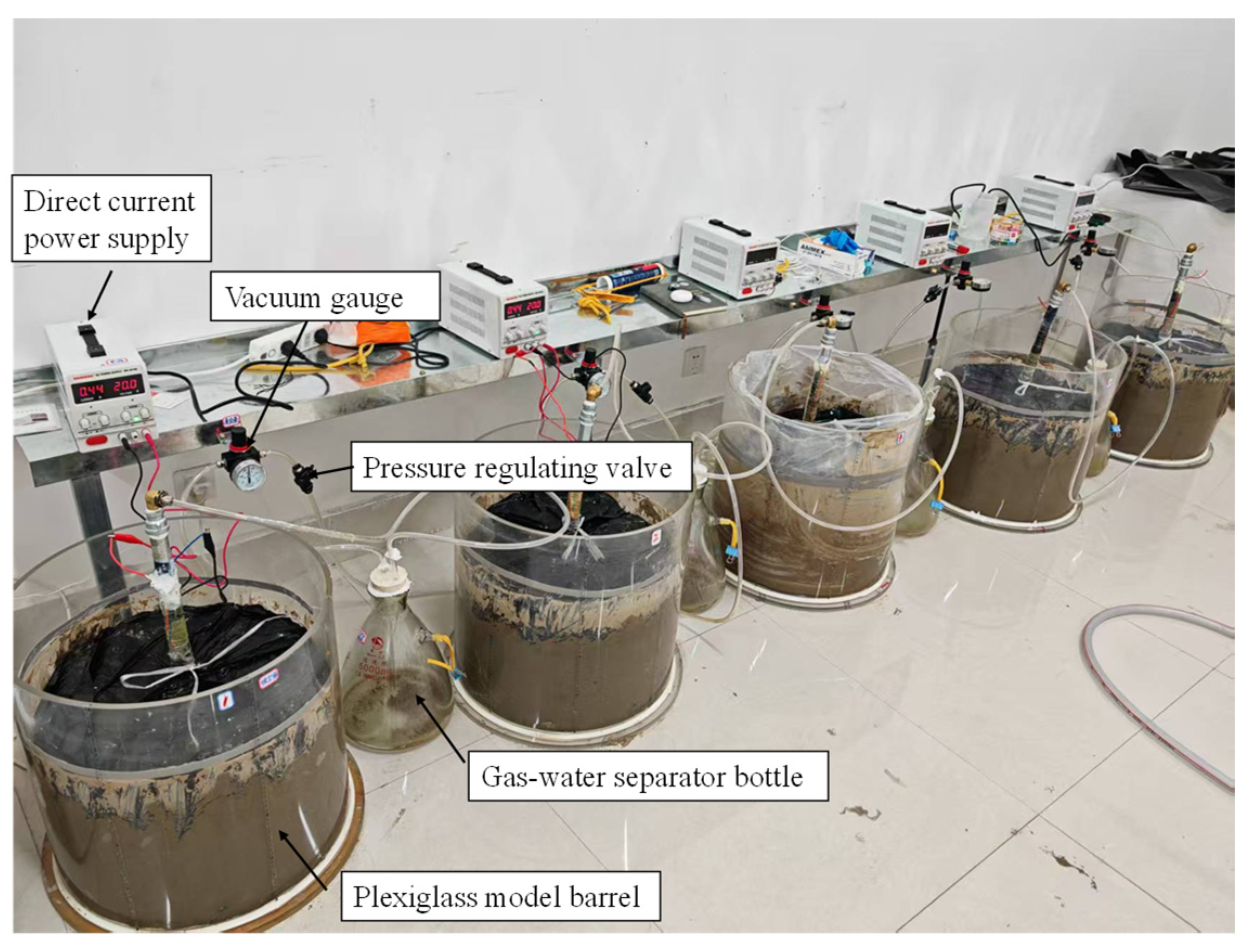

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

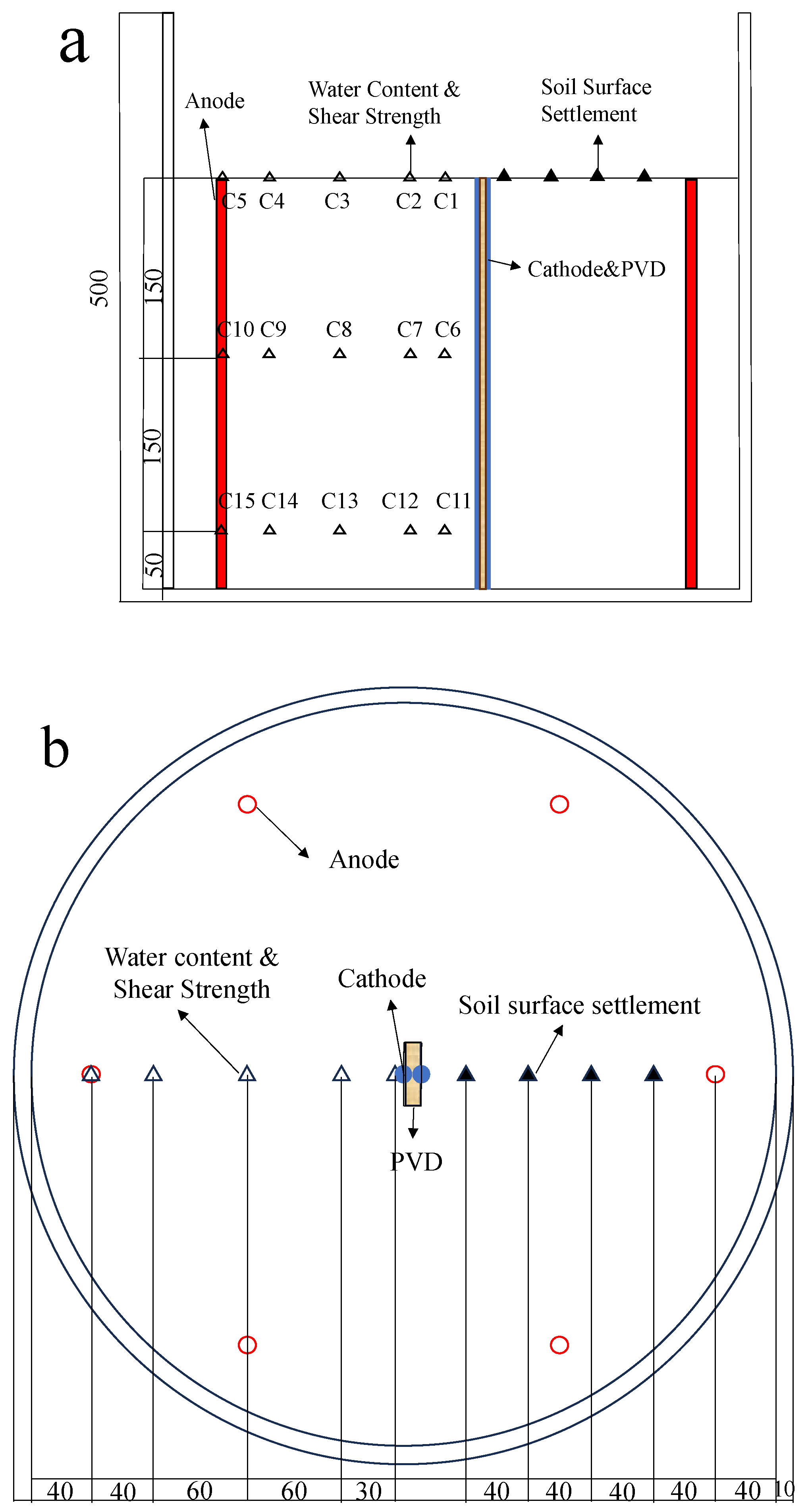

2.2. Methods

3. Results

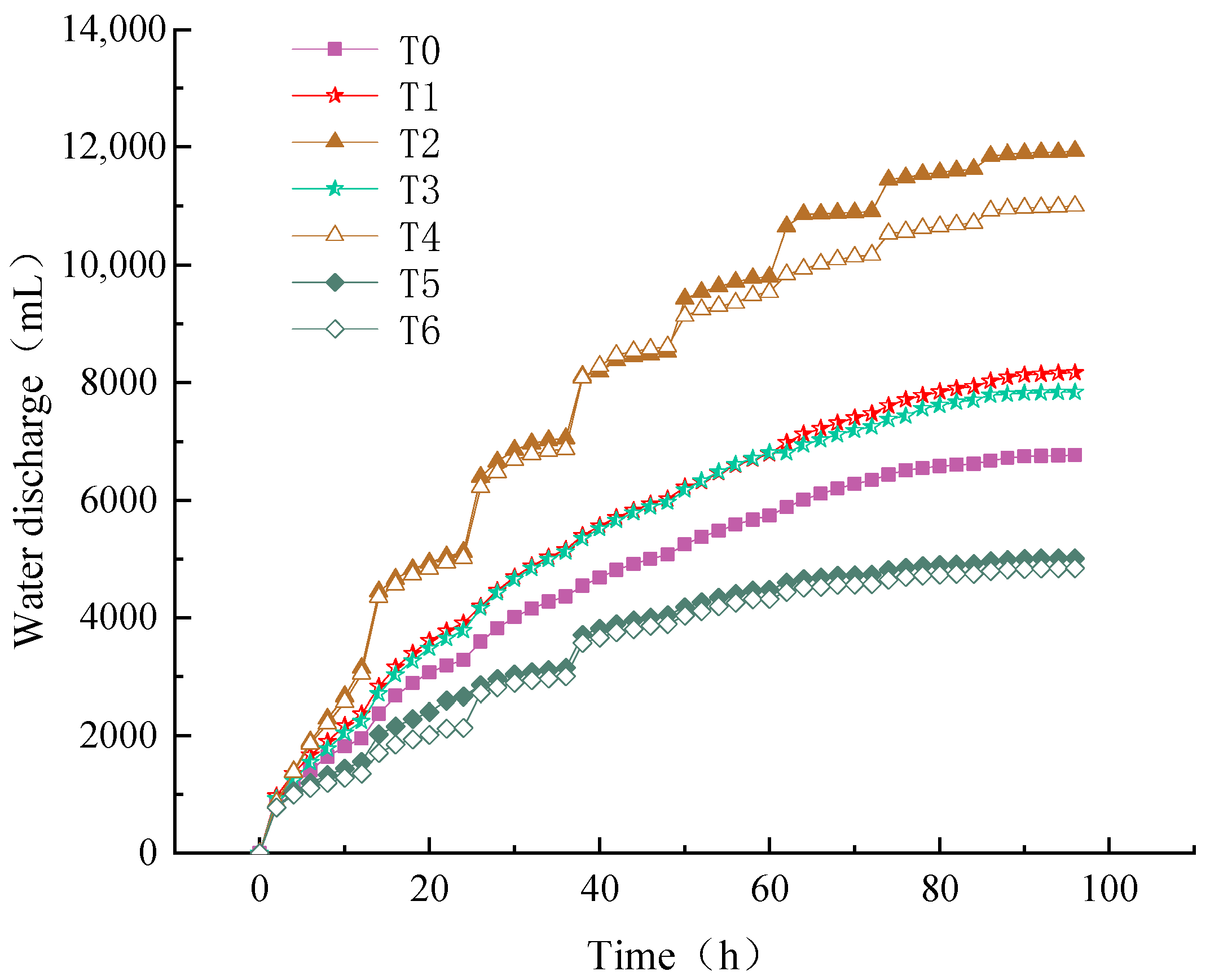

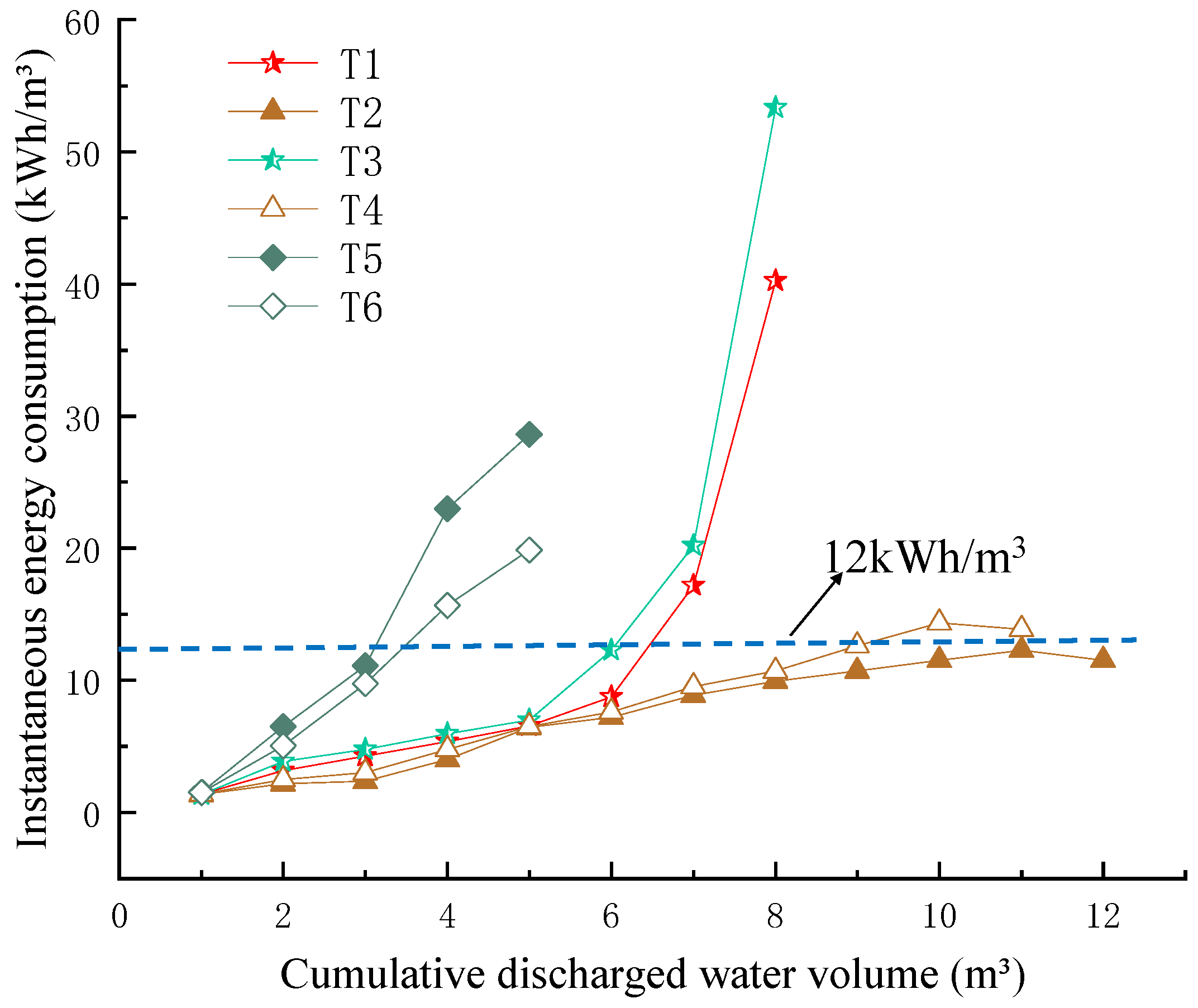

3.1. Cumulative Water Discharge

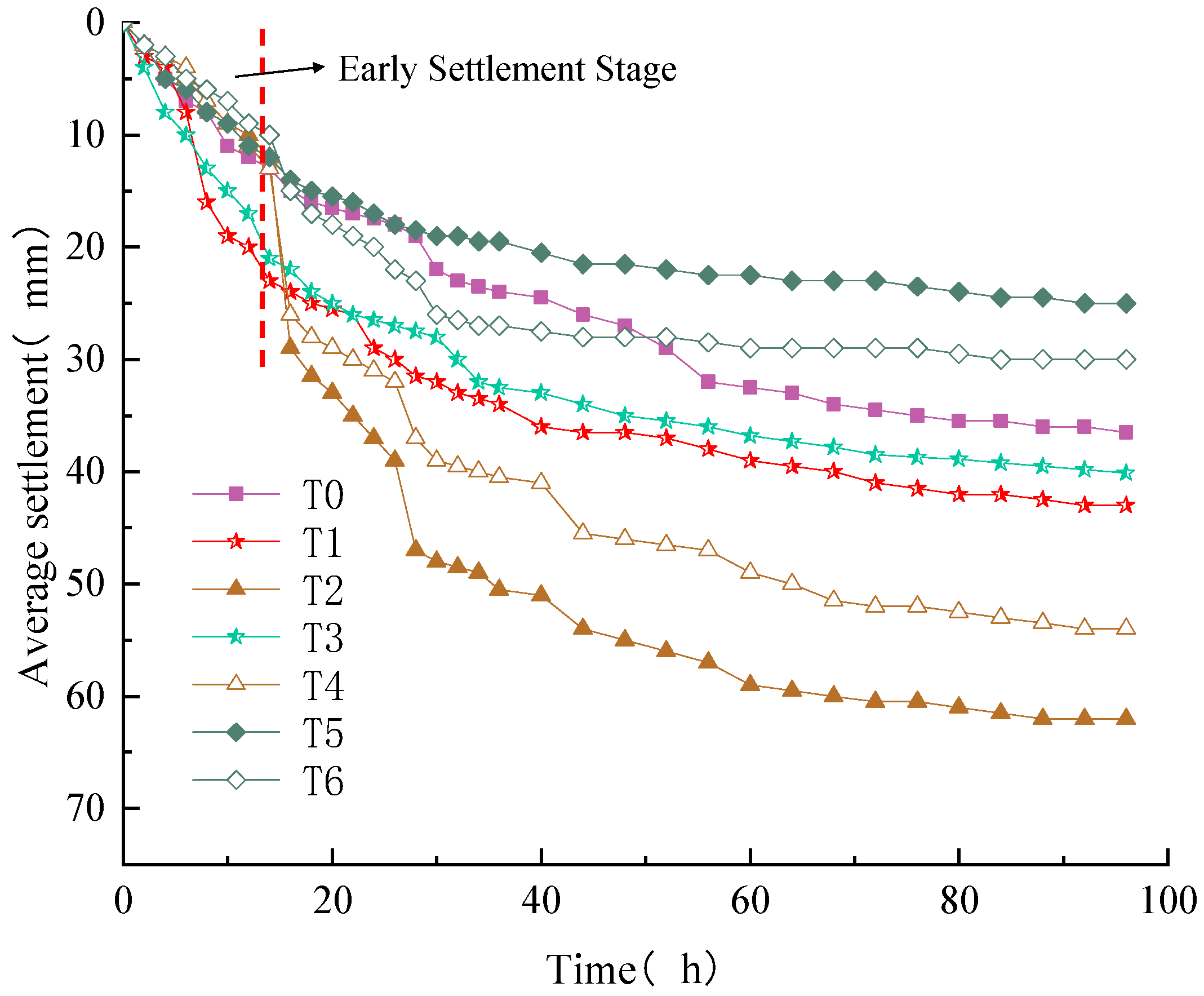

3.2. Surface Settlement

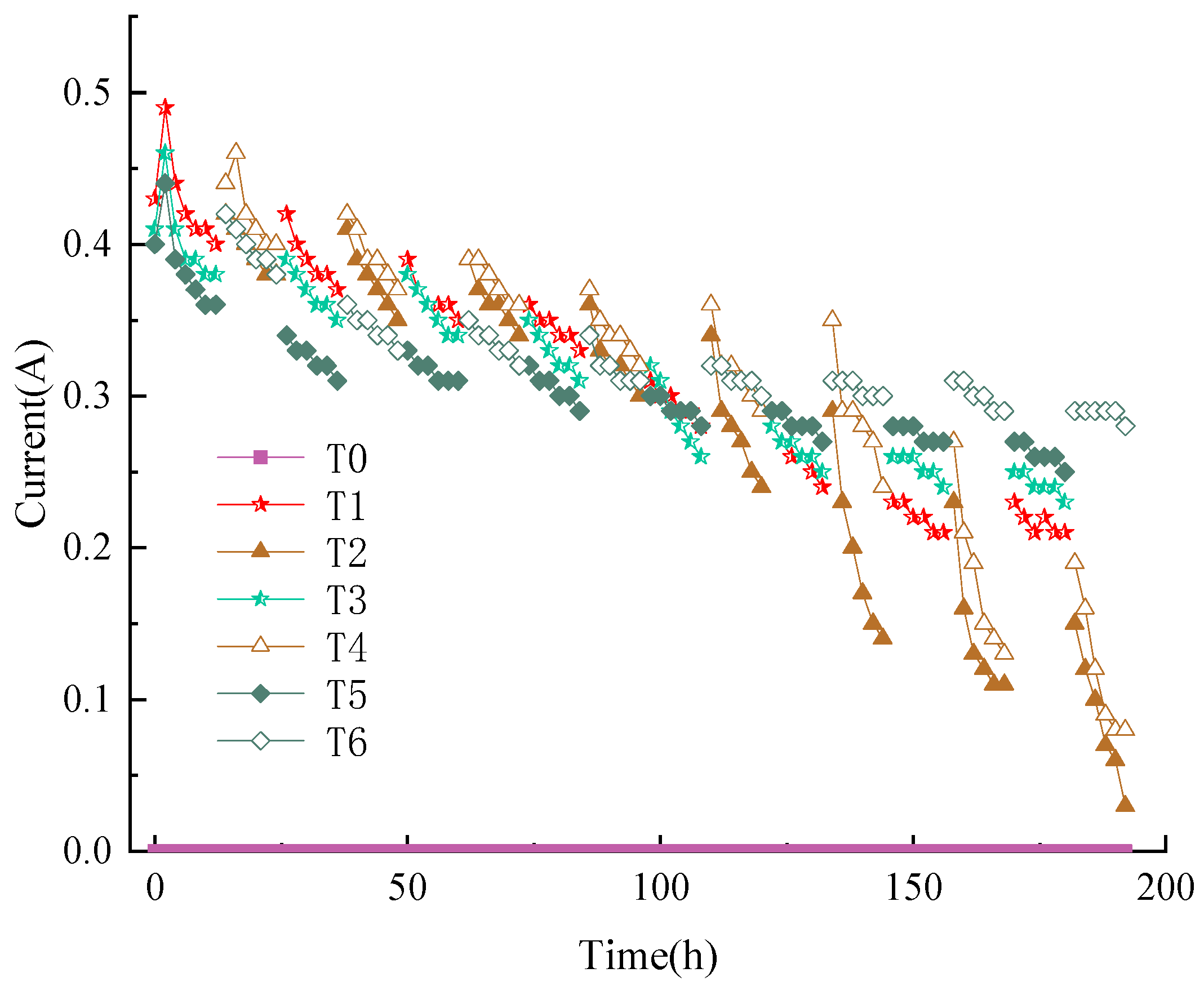

3.3. Soil Electric Current

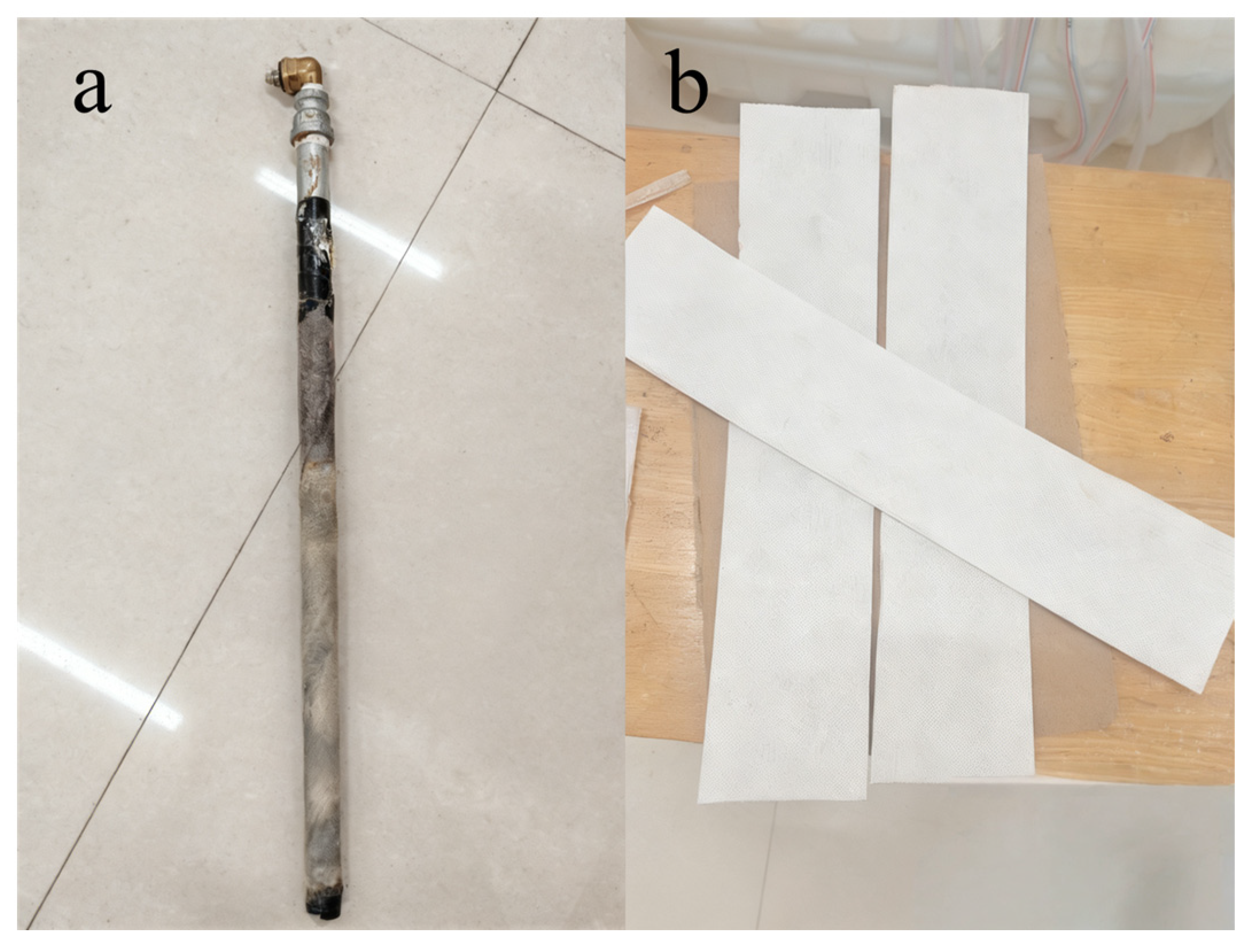

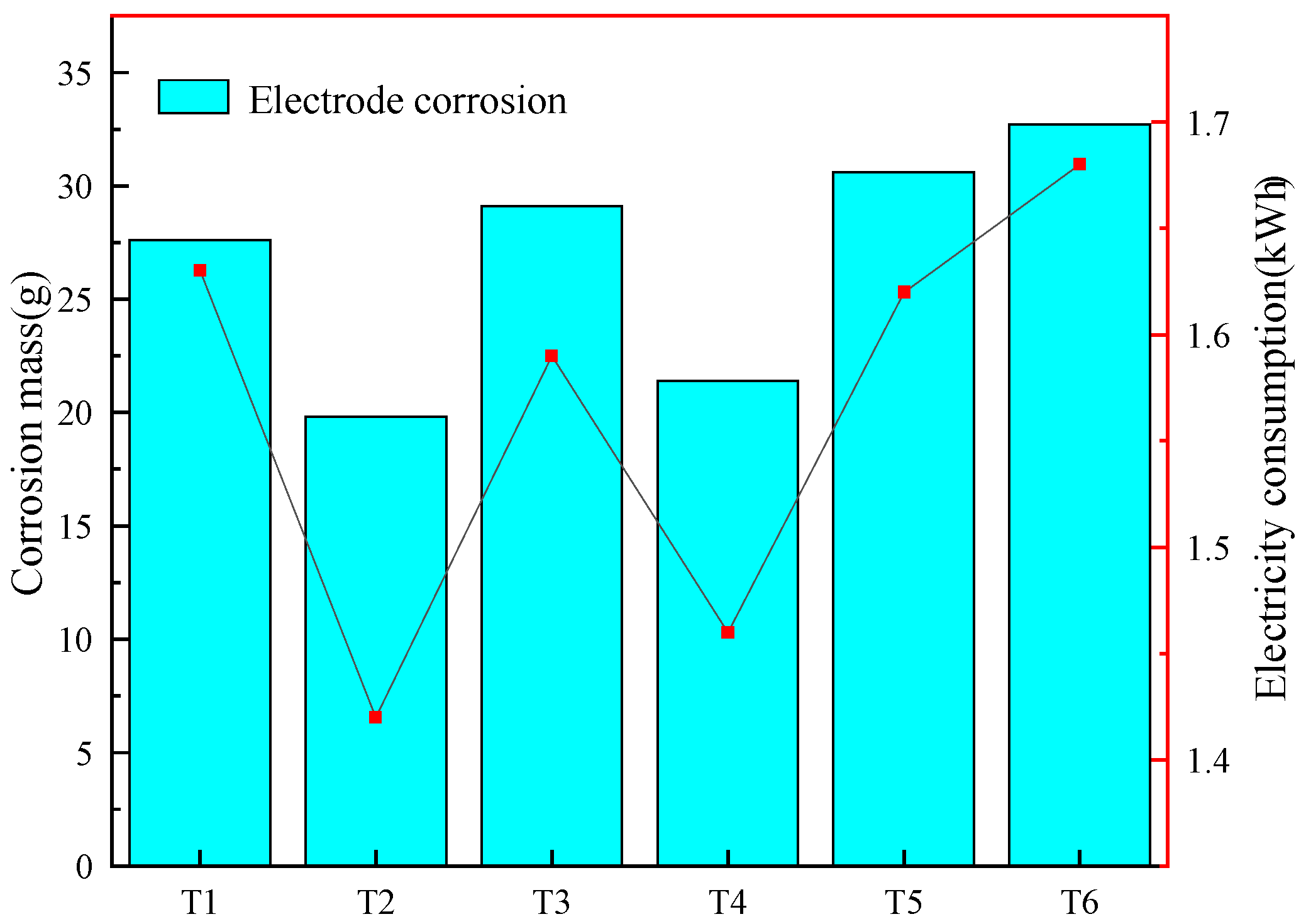

3.4. Electrode Corrosion and Energy Consumption

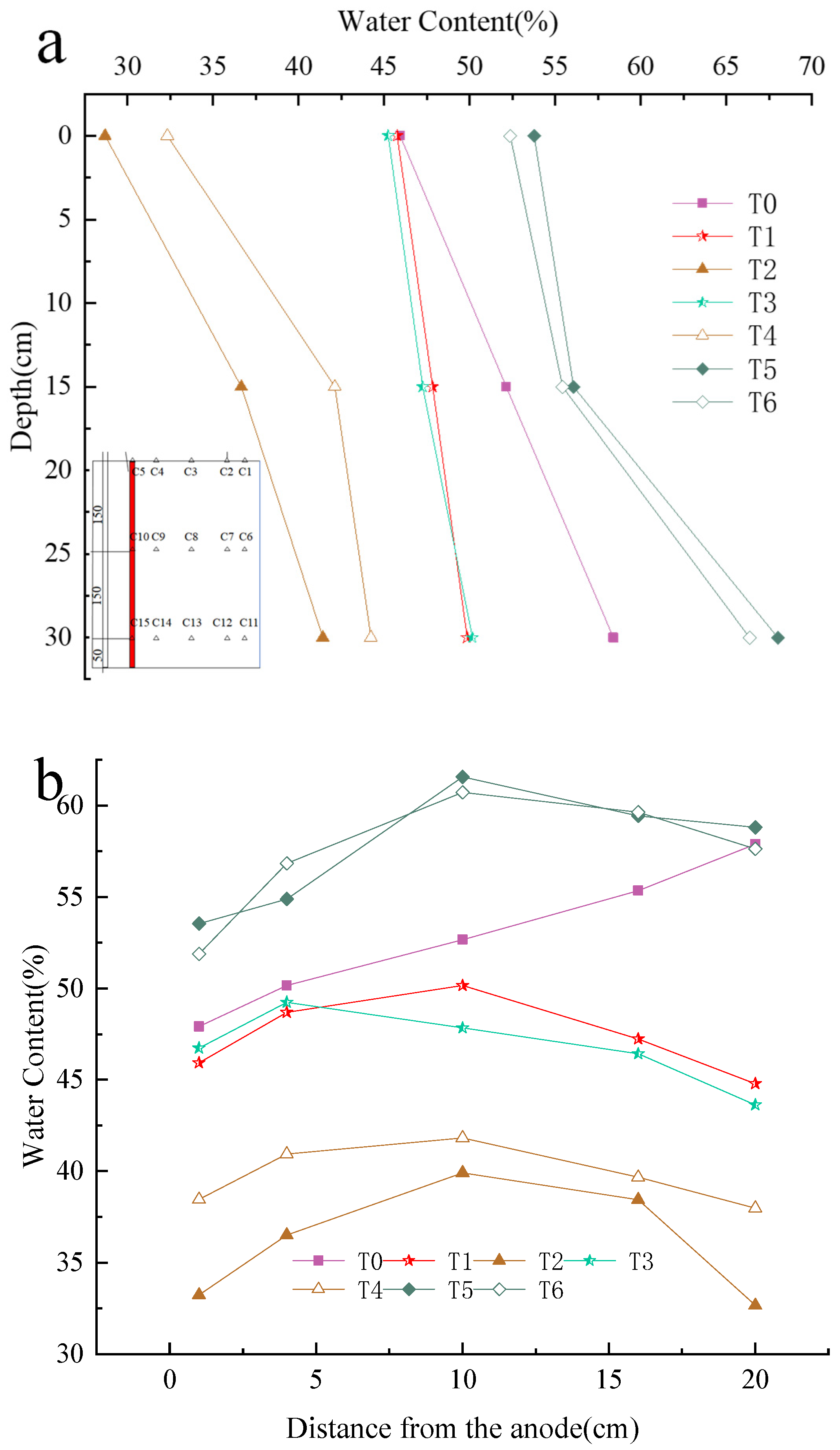

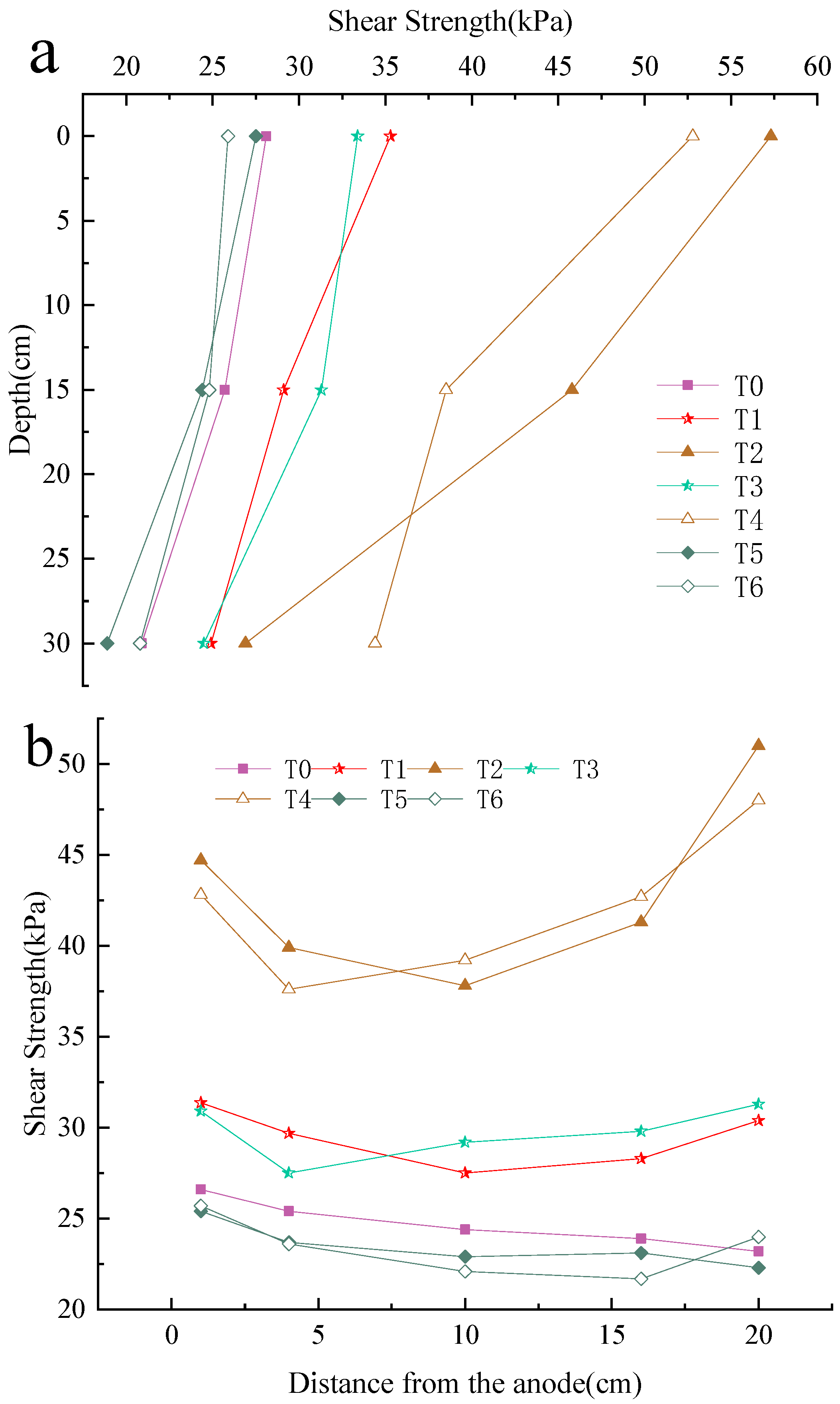

3.5. Water Content and Shear Strength

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Intermittent vacuum preloading (VP) alone showed suboptimal late-stage performance with high energy consumption. While synchronous VP–electroosmosis (EO) marginally improved water discharge but was less effective than alternating VP-EO, which boosted total water discharge by 46.1%. The alternating loading mode thus offers superior energy efficiency and consolidation efficacy for clayey soil reinforcement.

- (2)

- While the synchronous reinforcement method improved initial settlement, its long-term efficiency is limited by the excessive coupled dewatering. This causes slower settlement progression and significant electrode corrosion, making it unsuitable for extended consolidation. In contrast, the alternating method exhibited moderate initial settlement but achieved stepwise improvement with late-stage electroosmosis integration. It resulted in 44.19% higher surface settlement and superior consolidation efficiency than the synchronous reinforcement method.

- (3)

- The alternating loading mode induces soil ion redistribution, resulting in a post-reconnection current exceeding pre-interruption levels. Furthermore, this method mitigates terminal-stage current decay, thereby sustaining drainage efficiency throughout the consolidation process.

- (4)

- Compared to integral plastic drainage boards, perforated metal drainage boards exhibited enhanced efficiency in late-stage drainage and reduced anode corrosion by 39.4%. This performance improvement stems from optimized electrochemical stability and reduced polarization resistance during sustained consolidation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VP | vacuum preloading |

| EO | electroosmosis |

| PVD | prefabricated vertical drains |

| DC | direct current |

References

- Chen, Q.; Ran, F.; Wei, Q.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Fan, C. A review on dewatering of dredged sediment in water bodies by flocculation processes. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Feng, J.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, D.; Gong, M. Amendment of Dredged Sediment from a Contaminated Lake and Assessment of Suitability as a Planting Medium for Urban Greening. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2024, 41, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Labianca, C.; Chen, L.; De Gisi, S.; Notarnicola, M.; Guo, B.; Sun, J.; Ding, S.; Wang, L. Sustainable ex-situ remediation of contaminated sediment: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffon, P.; Uijttewaal, W.S.J.; Valero, D.; Franca, M.J. Evolution of Erosion and Deposition Induced by an Impinging Jet to Manage Sediment. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR038657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Song, D.B.; Yin, Z.Y.; Yin, J.H.; Chen, W.B. Novel Combined Grid PHD–PVD Vacuum Preloading Method for Treatment of Blow-Filled Slurry: Large-Scale Physical Model Test. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2025, 151, 04025090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-J.; Li, P.-L.; Li, A.; Yin, J.-H.; Song, D.-B. New simple method for calculating large-strain consolidation settlement of layered soft soils with horizontal drains and vacuum preloading with comparison to test data. Geotext. Geomembr. 2024, 52, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Amoudry, L.O.; Souza, A.J.; Rees, J. Fate and pathways of dredged estuarine sediment spoil in response to variable sediment size and baroclinic coastal circulation. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 149, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.H.; Chen, W.B.; Wu, P.C.; Leung, A.Y.F.; Yin, Z.Y.; Cheung, C.K.W.; Wong, A.H.K. Field study of a sustainable land reclamation approach using dredged marine sediment improved by horizontal drains under vacuum preloading. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2024, 150, 04024114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; You, N.; Chen, C.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, Y. The positive role of phosphogypsum in dredged sediment solidified with alkali-activated slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 442, 137627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; Ni, J.; Wang, Y. Hydro-mechanical behaviour of straw fiber-reinforced cemented dredged sediment at high water content. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 3530–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lu, H.; Li, Z. Effect of precursor element composition on compressive strength of alkali-activated dredged sediment. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.J.; Yue, Z.X.; Wang, Z.J.; Huang, Q.; Yang, X.L. Optimization and mechanism of the novel eco-friendly additives for solidification and stabilization of dredged sediment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 25964–25977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, S.; Wang, P.; Hu, X.; Geng, X.; Hai, J.; Jin, J.; Jiang, Z.; Ye, Q.; Chen, Z. Effect of the pressurized duration on improving dredged slurry with air booster vacuum preloading. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2020, 38, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G. Synergistic influence of lime and straw on dredged sludge reinforcement under vacuum preloading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 421, 135642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Toma, A.; Bo, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, H. Reinforcement effect of the stepped-alternating vacuum preloading method on dredged fills. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 04023272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, R. Experimental study on the improvement of sludge by vacuum preloading-stepped electroosmosis method with prefabricated horizontal drain. Geotext. Geomembr. 2024, 52, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Tu, J.; Wang, X.; Diao, H.; Ge, Q. Design Method and Verification of Electroosmosis-Vacuum Preloading Method for Sand-Interlayered Soft Foundation. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1929842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, R.; Cai, Y.; Fu, H.; Li, X.; Hu, X. Vacuum preloading and electroosmosis consolidation of dredged slurry pre-treated with flocculants. Eng. Geol. 2018, 246, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, B.; Qi, C.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Min, F. Influence of composite flocculants on electrokinetic properties and electroosmotic vacuum preloading behavior of sludge. Dry. Technol. 2024, 42, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yao, K.; Yang, C.; Liang, M. Improvement of soft clay by vacuum preloading incorporated with electroosmosis using electric vertical drains. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2021, 39, 1339–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fu, H.; Liu, F.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, J. Influence of electroosmosis activation time on vacuum electroosmosis consolidation of a dredged slurry. Can. Geotech. J. 2018, 55, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, M.; Li, L.; Wu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Mei, G. Analytical solution for radial consolidation of combined electroosmotic, vacuum, and surcharge preloading considering smear effects. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 04024141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, R.; Fu, H.; Wang, J.; Cai, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhou, J.; Hai, J. Slurry improvement by vacuum preloading and electroosmosis. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Geotech. Eng. 2019, 172, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Deng, A. Modelling combined electroosmosis–vacuum–surcharge preloading consolidation considering large-scale deformation. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 109, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Feng, J.; Qiu, C.; Wu, J. Two-dimensional consolidation theory of vacuum preloading combined with electroosmosis considering the distribution of soil voltage. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 2020, 57, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Wang, Y. Theoretical and experimental study on the consolidation of soil with continuous drainage boundary under electroosmosis–surcharge preloading. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Qiu, C.; Li, Y.; Shi, W.; Rui, X. An analytical solution for two-dimensional vacuum preloading combined with electroosmosis consolidation using EKG electrodes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Fu, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, R.; Lou, X.; Jin, Y.; Yuan, W. Vacuum preloading combined with intermittent electroosmosis for dredged slurry strengthening. Geotech. Test. J. 2020, 43, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Gao, M.; Yu, X. Dewatering effect of vacuum preloading incorporated with electroosmosis in different ways. Dry. Technol. 2017, 35, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Yuan, G.; Wang, J. Experimental study on dredged slurry improvement by vacuum preloading combined with intermittent electroosmotic. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2021, 43, 1–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50123-2019; Standard for Geotechnical Testing Method. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Zhang, H.; Tu, C.; He, C. Study on sustainable sludge utilization via the combination of electroosmotic vacuum preloading and polyacrylamide flocculation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.; Booker, J. The effect of increasing strength with depth on the bearing capacity of clays. Geotechnique 1973, 23, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massri, M.; Newson, T. Numerical investigation of the bearing capacity of ring foundations on inhomogeneous clay. In Proceedings of the Canadian Geotechnical Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1–4 October 2017; pp. 526–1079. [Google Scholar]

| Specific Gravity | Hydraulic Conductivity/(cm·s−1) | Water Content/% | Liquid Limit/% | Plastic Limit/% | Particle Size Distribution/% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.005 | 0.005~0.05 | 0.05~0.1 | |||||

| 2.72 | 2.54 × 10−7 | 69.7 | 38.6 | 21.3 | 18.9 | 49.61 | 31.49 |

| Category | Performance Indicators | Unit | Range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrator | Thickness | mm | 4.0 ± 0.2 | / |

| Width | mm | 100 ± 3 | / | |

| Failure tensile strength | kN/10 cm | ≥1.3 | Percentage elongation 10% | |

| Water Discharge Capacity | cm3/s | ≥25 | Lateral pressure 350 kPa | |

| Filter membrane | Dry tensile strength | N/cm | ≥25 | Percentage elongation 10% |

| Wet tensile strength | N/cm | ≥20 | Percentage elongation 15%, waterlogging 24 h | |

| Hydraulic conductivity | cm/s | 5.0 × 10−4 | Waterlogging 24 h | |

| Equivalent opening size | um | 75 | According to the O98 standard | |

| Material | Filter membrane | / | / | Nonwoven polyester chemicals, Hydrophilic material |

| Core | / | / | Olypropylene, Polyethylene |

| Test Groups | Voltage/V | Vertical Drainage Body | Vacuum Degree/kPa | Vacuum Loading Mode | Electroosmosis Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | / | Integrated drainage board | 80 | Turn on the pump 12 h Turn off the pump 12 h | / |

| T1 | 20 | Perforated metal drainage pipe | 80 | Power on while turning on the pump | |

| T2 | 20 | 80 | Power on while turning off the pump | ||

| T3 | 20 | Integrated drainage board | 80 | Power on while turning on the pump | |

| T4 | 20 | 80 | Power on while turning off the pump | ||

| T5 | 20 | 50 | Power on while turning on the pump | ||

| T6 | 20 | 50 | Power on while turning off the pump |

| Source | Sum of Squares (SS) | Degrees of Freedom (df) | Mean Square (MS) | F-Value | p-Value | F Critical (Fcrit) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 9.81 × 1008 | 6 | 1.63 × 1008 | 28.89 | 7.64 × 10−28 | 2.13 |

| Within Groups | 1.90 × 1009 | 336 | 5.66 × 1006 | / | / | / |

| Total | 2.89 × 1009 | 342 | / | / | / | / |

| Source | Sum of Squares (SS) | Degrees of Freedom (df) | Mean Square (MS) | F-Value | p-Value | F Critical (Fcrit) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 6271.52 | 6 | 1045.25 | 20.6 | 1.78 × 10−15 | 2.19 |

| Within Groups | 4973.27 | 98 | 50.75 | / | / | / |

| Total | 11,244.79 | 104 | / | / | / | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Du, C.; Yang, Y.; Dong, X.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, P. Experimental Study on Alternating Vacuum–Electroosmosis Treatment for Dredged Sludges. Water 2025, 17, 3499. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243499

Wang J, Wu Y, Du C, Yang Y, Dong X, Yang S, Wang J, Zhang P. Experimental Study on Alternating Vacuum–Electroosmosis Treatment for Dredged Sludges. Water. 2025; 17(24):3499. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243499

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiangfeng, Yifeng Wu, Chunxue Du, Yang Yang, Xinhua Dong, Shen Yang, Jifeng Wang, and Pei Zhang. 2025. "Experimental Study on Alternating Vacuum–Electroosmosis Treatment for Dredged Sludges" Water 17, no. 24: 3499. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243499

APA StyleWang, J., Wu, Y., Du, C., Yang, Y., Dong, X., Yang, S., Wang, J., & Zhang, P. (2025). Experimental Study on Alternating Vacuum–Electroosmosis Treatment for Dredged Sludges. Water, 17(24), 3499. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243499