1. Introduction

Food and water are indispensable to human survival and socio-economic development [

1]. Yet the world is facing mounting challenges from food waste and freshwater scarcity [

2,

3]. In 2022, nearly one-fifth of global freshwater was lost in supply chains, while water pollution, inefficient irrigation, and rapid urbanization have intensified water stress; available freshwater is projected to decline substantially by 2030 [

4]. Concurrently, roughly 17% of global food production is wasted annually, imposing significant environmental and economic burdens [

5]. The United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Goals explicitly target reductions in food waste (SDG 2) and the sustainable management of water (SDG 6), highlighting the centrality of food–water interactions to global sustainability agendas [

6].

At the behavioral level, both food-conservation and water-conservation behaviors are recognized as important forms of pro-environmental actions [

7,

8]. Existing studies have primarily examined demographic factors such as gender [

9], age [

10], educational attainment [

11], and income [

12,

13]. In addition, socio-psychological determinants such as knowledge [

14], attitudes [

15], and emotions and external conditions such as public campaigns [

16], infrastructure [

17], and pricing [

18] have also been studied. These investigations commonly draw on frameworks such as the Theory of Planned Behavior [

19] and environmental behavior models, and they apply methods including structural equation modeling [

20] and multiple regression analysis [

21] to identify diverse influence pathways. For instance, Qian et al. [

11] explored the association between awareness campaigns and food waste among Chinese students, while Marlim and Kang [

18] investigated the role of water pricing in reshaping consumers’ water usage patterns. The food system is a major consumer of water, and both production and waste embody a complex water footprint—the direct and indirect volume of water required to produce goods. However, relatively few studies adopt a virtual water or water-footprint perspective to examine how public cognition influences synergistic behavior that conserves both food and water.

Tony Allan introduced the notion of virtual water in 1993 to denote the volume of water used to produce goods and services [

22]. The water-footprint concept was developed subsequently to quantify the total volume of water consumed by a country, region, or individual to support a given standard of living [

23]. These concepts have been widely used to trace water flows across production and trade, and they are increasingly referenced in policy discussions about sustainable supply chains [

24,

25]. However, their application at the consumption stage, particularly in understanding consumer cognition and everyday decision-making, remains limited. This study contends that food waste prevention represents a critical and behaviorally tractable domain in which to examine these links: as a typical consumer-side behavior directly shaped by everyday decision-making, food waste creates an intuitive connection between discarded food and the waste of its embedded virtual water—a relationship that is both direct and conceptually accessible for consumers. This makes it a potent focus for investigating the knowledge–action framework, which posits that awareness of environmental costs (e.g., virtual water in food) can drive corresponding pro-environmental behaviors.

Despite the potential of these concepts to bridge food and water conservation, empirical evidence regarding whether specific cognition of virtual water and water footprint can influence both food-conservation and water-conservation behaviors remains scarce. Few studies have tested whether such cognition can stimulate synergistic behaviors—coordinated actions where conservation in one domain triggers savings in another. This empirical gap matters for two key reasons. First, behavioral synergies can amplify resource savings, yielding outcomes that exceed the sum of isolated actions. If individuals recognize that wasting food also wastes water, they may be more motivated to reduce waste in both domains. Second, insights into the knowledge–action framework can guide integrated interventions that target multiple sustainability goals simultaneously, thereby improving both impact and cost-effectiveness. This framework encompasses the cognitive → behavioral pathways through which environmental knowledge is translated into concrete actions, as well as the mediators and contextual moderators that can create a knowledge–action gap. The lack of empirical evidence is particularly pronounced in emerging economies, where both food and water systems face growing stress. China, home to nearly 40 million university students, represents a strategically important population for environmental education and behavior-change initiatives [

26,

27]. University students are in a formative stage of establishing long-term consumption habits, and their behaviors can be influenced by targeted interventions at a relatively low cost. Although research in Denmark, Poland, and other Western countries has explored conservation behaviors among students [

28,

29], comparable studies in China are limited, especially those applying a virtual water perspective to examine cross-behavioral synergies in food and water conservation.

To address these gaps, this study investigates how virtual water cognition (VWC) influences food-conservation and water-conservation behaviors among Chinese university students, and whether it promotes food–water synergistic cognition (FWSC). Based on a large-scale survey (N = 5853) conducted in China, we employ multiple linear regression, binary logistic regression, and partial least squares structural equation modeling to examine both direct and indirect pathways. Specifically, we aim to (1) profile the prevalence and patterns of food-conservation and water-conservation behaviors among consumers; (2) assess the relationship between VWC and each conservation behavior; (3) explore heterogeneity across demographic and contextual subgroups; and (4) analyze the mechanisms linking VWC, food–water synergistic cognition, food-conservation behavior, and water-conservation behavior. By embedding the virtual water concept into a knowledge–action framework, this study makes three contributions. First, it advances theoretical understanding of the food–water nexus by connecting resource-flow knowledge to multi-domain conservation behaviors, addressing a critical omission in existing literature. Second, it offers empirical evidence from a large, under-researched population in a non-Western context, enriching cross-cultural perspectives on sustainability behaviors. Finally, it provides actionable insights for designing targeted educational strategies and consumer-level interventions that leverage behavioral synergies to enhance food and water resource conservation.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

This study conducted a campus-wide online survey from 2021 to 2024 targeting all students at Hohai University, Nanjing, to collect primary data on food-conservation and water-conservation behaviors. Hohai University was selected for three main reasons. First, as a top institution in water-related majors, it offers a wide range of majors related to water resources and the environment, including economics, management, and social sciences. This diversity of majors will reflect the impact of different professional backgrounds on the understanding of resources, thereby enhancing the universality of this study’s conclusions. Second, differences in students’ academic majors provide a natural contrast group—what we refer to as “controlled heterogeneity”—which will help disentangle the effects of individual cognitive awareness from the shared institutional context. Third, Hohai University is located in Jiangsu Province, at the source of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project and in one of China’s major grain-producing regions, presumably giving students heightened awareness of the link between water resources and food security.

The questionnaire comprised two sections. The first collected demographic and contextual information such as gender, educational level (undergraduate/Master’s/doctoral students), academic year, major, hometown region (classified by water availability [abundant/scarce] and agricultural productivity [core/non-core production area]), and type of residence (urban/rural). The second covered three modules: (1) water-conservation behaviors and influencing factors (daily practices and drivers of water-conservation actions), (2) food-conservation behaviors and influencing factors (daily practices and drivers of food-conservation actions), and (3) cognition of the synergy between food conservation and water conservation (including understanding of “virtual water” and “water footprint”, as well as recognition of the link between conserving food and conserving water). All listed conservation behaviors reflected realistic actions that students could take within campus settings, and the knowledge acquisition channels were tailored to students’ common learning modes.

To ensure broad and voluntary participation while minimizing selection bias, the survey was promoted through multiple official university channels (e.g., student associations, campus social media, and university newsletters). Furthermore, the questionnaire was designed to be concise and highly relevant to students’ daily lives, which also contributed to the high engagement rate. A total of 5861 questionnaires were distributed. After removing incomplete or invalid responses (e.g., inconsistent or random answers), 5853 valid responses were retained (valid response rate: 99.86%) for subsequent analyses. The survey did not involve personally identifiable or sensitive information; hence, ethical approval was not required [

30]. Detailed survey items are provided in

Supplementary Material S1.

2.2. Measuring Dependent Variables

Our primary focus is on food-conservation and water-conservation behaviors and their potential synergies. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines food waste as the discarding of food still safe for human consumption at the retail, food service, and consumer stages. In parallel, the Chinese government’s 2019 guidance for universities emphasizes stringent water-conservation measures and the maximization of water-use efficiency in campus management. Drawing on these definitions and the specific campus context—where food and water waste are particularly prevalent—we asked respondents to indicate which of the several specified actions they had taken (multiple responses allowed;

Figure 1;

Table A1). When it comes to conserving food, consumers mainly take direct action, while indirect actions (such as Balanced Meat-Veg, which contributes to food conservation through the optimization of demand-side consumption structures, shifting consumer preferences and ultimately influencing agricultural production systems at the source) are the least popular choice. Similarly, for water-conservation behaviors, direct actions dominated, while both indirect behaviors and the adoption of alternative technologies were the least common. This suggests that consumers tend to prioritize immediate, tangible actions over more indirect strategies for resource conservation.

This study used binary coding: each selected option was coded as 1, and unselected options as 0. To compute aggregate behavior scores, we applied a combined weighting method integrating the entropy method and CRITIC method (equal weighting), summed the weighted items, and standardized the total score (z-score) to mitigate ceiling and clustering effects. This yielded two composite indices: the food-conservation behavior score (FCBS) and the water-conservation behavior score (WCBS). Internal consistency was acceptable, with Cronbach’s α = 0.660 (slightly below the conventional 0.70 threshold but acceptable for behavioral indices). As a complementary measure, we also collected self-reported food-conservation behavior frequency (FCBF) and water-conservation behavior frequency (WCBF). These were single-choice questions with five ordered response levels: never, occasionally, sometimes, often, and very likely.

Table A2 shows the distribution of frequency variables, with the average values for FCBF and WCBF being similar. In subsequent analyses, these frequency measures were treated as ordinal dependent variables. In this study, WCBS and FCBS serve as behavioral score variables, while WCBF and FCBF function as behavioral frequency variables; both are dependent variables.

2.3. Measuring Independent Variables

The key explanatory variable in this study was virtual water cognition (VWC), defined here as domain-specific technical knowledge reflecting familiarity with scientific concepts such as “virtual water” and “water footprint.”. Respondents were asked to self-assess their familiarity with the terms virtual water and water footprint on a five-point scale (very unfamiliar, somewhat familiar, moderately familiar, fairly familiar, fully familiar). These were then combined into a composite VWC index.

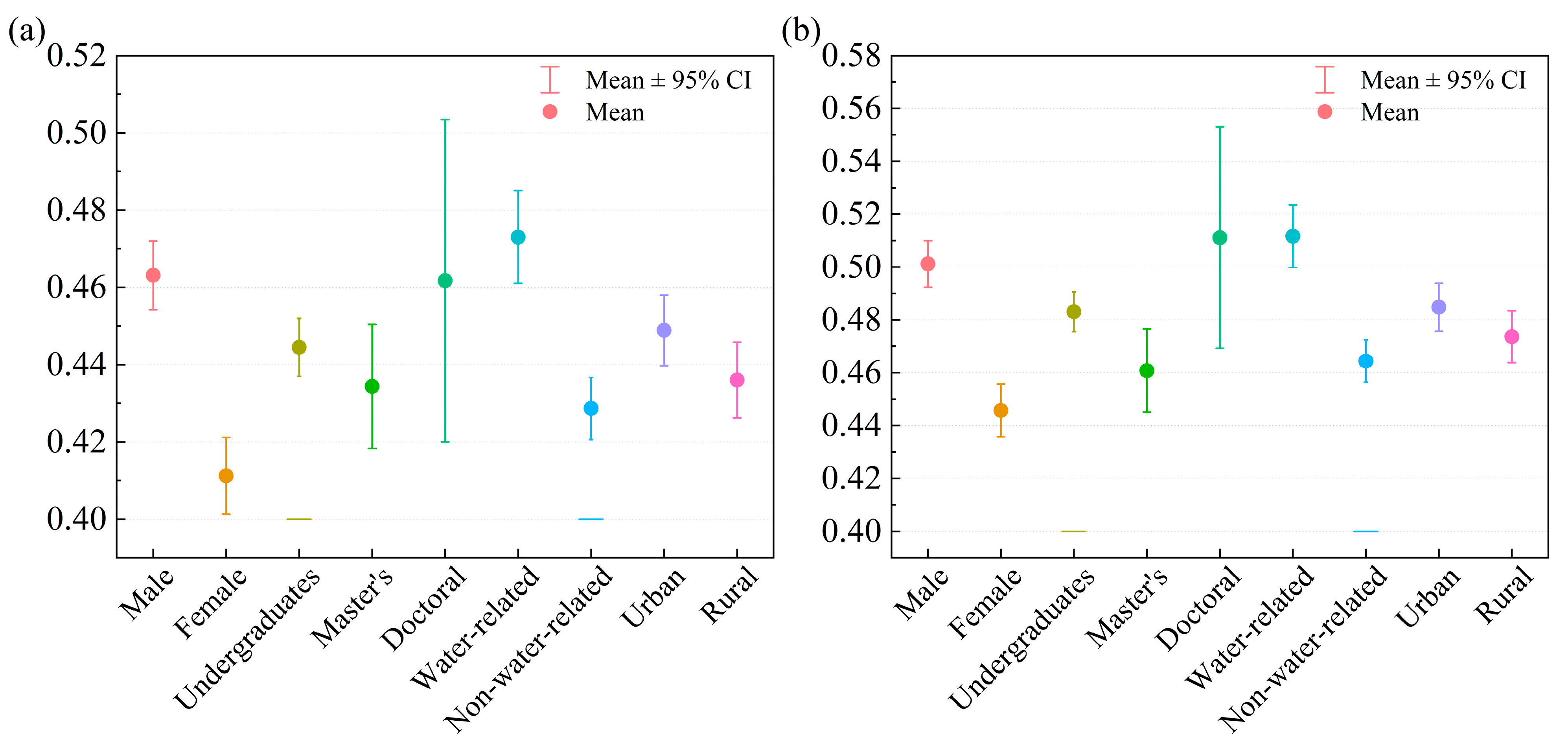

Figure 2 presents the distribution of responses, indicating that overall familiarity was relatively low; on average, students reported slightly greater understanding of water footprint than of virtual water. Familiarity levels varied across subgroups: male students demonstrated higher familiarity with both concepts than females; among the three educational levels, master’s students reported the lowest familiarity; students in water-related majors showed greater understanding of both terms than those in non-water-related fields; and respondents from rural areas exhibited lower cognition compared with their urban counterparts.

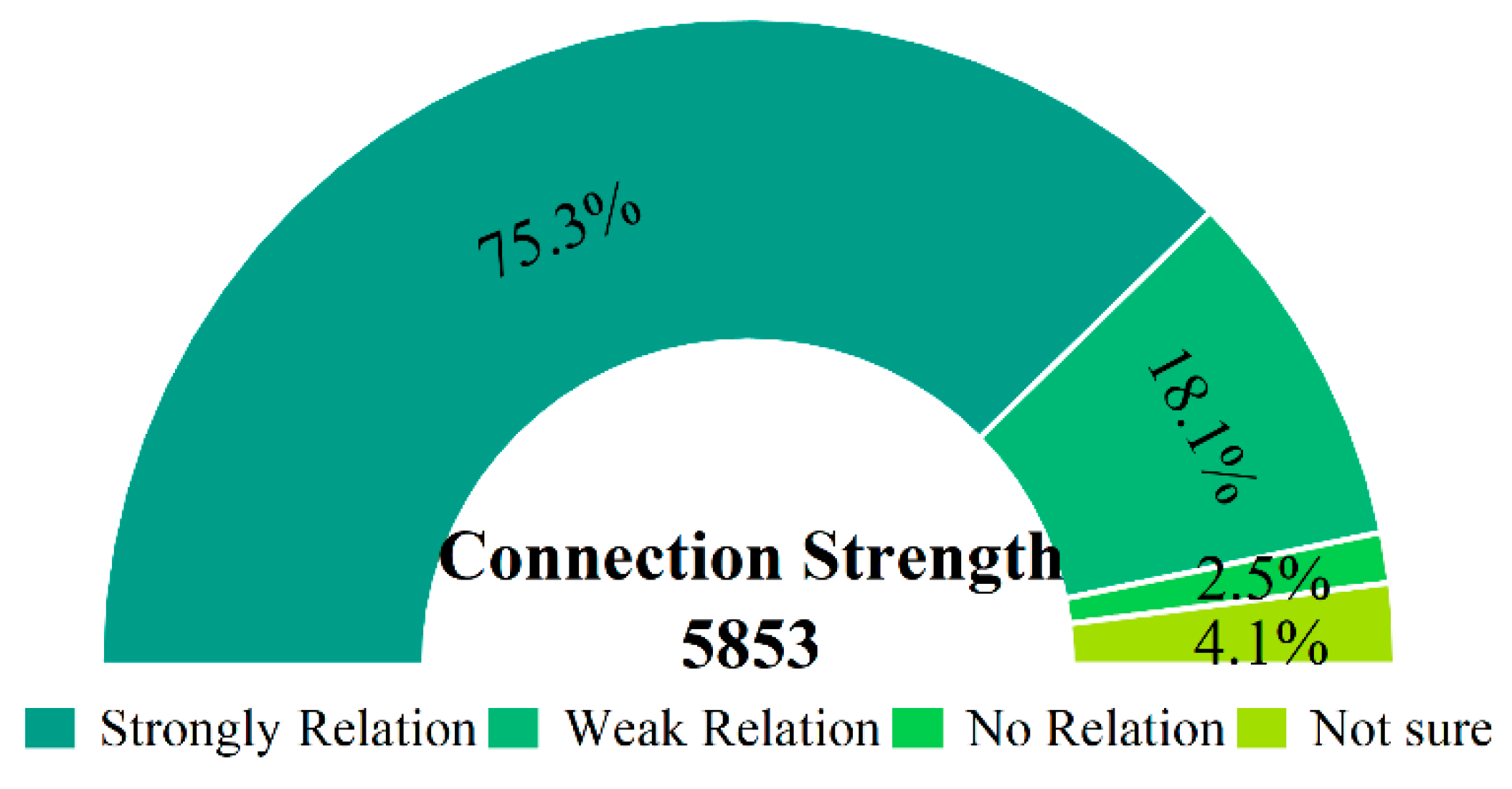

Another explanatory variable was food–water synergistic cognition (FWSC), defined here as contextualized experiential cognition capturing the extent to which individuals perceive and internalize the interdependence between food conservation and water conservation in everyday contexts. FWSC was measured using a scale comprising three items (

Table 1). Respondents were asked three questions: (1) “Is there a relationship between conserving food and conserving water?”; (2) “Is conserving food another way of conserving water?”; and (3) “Can water-conservation campaigns improve public cognition of conserving food?” More than half of respondents indicated that conserving food saves water used in crop cultivation, and approximately 35% recognized that it reduces water use in food production (

Figure A1). Furthermore, over 75% strongly agreed that there is a strong correlation between conserving food and conserving water (

Figure A2). Together, these items capture students’ recognition of the interlinked nature of food and water conservation. To construct a unified FWSC index, responses to each item were first mapped to a 3-point ordinal scale (1–3) reflecting the strength of synergistic cognition, with higher scores indicating stronger cognition (

Table 1). The scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency for an exploratory three-item construct (Cronbach’s α = 0.600), and its measurement properties are fully reported in

Table A11.

Factors influencing students’ food-conservation and water-conservation behaviors are multidimensional. Drawing on prior research of environmental and conservation behaviors, we incorporated six control variables covering individual and regional characteristics to minimize omitted-variable bias. At the demographic level, controls included gender, education level, academic year, and major. At the contextual level, we included home-region classification and urban–rural residence.

Table A3 provides definitions and descriptive statistics for these variables. Among respondents, 61.6% were male and 38.4% were female; 32.7% were enrolled in water-related majors. Academic status was distributed as 79.4% undergraduates, 17.8% master’s students, and 2.8% doctoral students. Geographically, 68.5% came from water-abundant regions (including both core and non-core production areas) and 31.5% from water-scarce regions. The sample also achieved balanced representation across urban and rural areas. This sampling strategy supports a robust analysis of the knowledge–action pathways underpinning food and water conservation.

2.4. Empirical Strategy

The core explanatory variable was VWC, supplemented by FWSC as an additional explanatory variable. The primary dependent variables were the food-conservation behavior score (FCBS) and water-conservation behavior score (WCBS), with corresponding behavioral frequency measures as secondary dependent variables. To examine the relationship between VWC and both conservation behaviors, we specified the following multiple linear regression models for each consumer:

where

and

denote standardized behavior scores,

is the core independent variable,

represents a set of control variables, and

is the error term. Parameters were estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS), with

and

indicating the effect of

on food-conservation and water-conservation behaviors, respectively.

To assess the likelihood of high-frequency conservation behaviors, respondents were classified into two groups—high-frequency (“often” or “very likely”) and low-frequency (“never”, “occasionally”, or “sometimes”)—and binary logistic regression was applied:

where

and

denote the probability of high-frequency engagement. The odds ratio (OR) for

indicates how

influences the likelihood of frequent conservation behaviors.

2.5. Research Hypothesis

Environmental knowledge is a well-established driver of conservation behavior. Empirical evidence consistently shows that individuals with greater environmental knowledge are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors [

31], likely because such knowledge enhances cognition of the environmental consequences of certain actions, strengthens perceived responsibility, and fosters voluntary pro-environmental choices. In the water sector, prior studies have confirmed that water-related knowledge is an important factor in changing water-use habits [

18]. Greater understanding of water scarcity and conservation activities significantly improves attitudes toward water conservation.

VWC, as a specific form of environmental knowledge, emphasizes the hidden water consumption embedded in food production, especially agricultural products. This construct links water resources directly to the food system. We therefore posited that enhancing VWC would not only directly influence food-conservation behavior (FCB) and water-conservation behavior (WCB) but also promote food–water synergistic cognition (FWSC), the recognition that conserving food inherently conserves water, thereby reinforcing both types of behaviors. Based on this logic, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1a: VWC has a significant impact on FCB.

H1b: VWC has a significant impact on WCB.

H2: VWC has a significant impact on FWSC.

H3a: FWSC has a significant impact on FCB.

H3b: FWSC has a significant impact on WCB.

H4: FCB has a significant impact on WCB (i.e., engaging in FCB significantly increases the likelihood of engaging in WCB).

These hypotheses were evaluated through the significance and direction of the corresponding path coefficients in the partial least squares structural equation modeling model, described in

Section 3.4.

4. Discussion

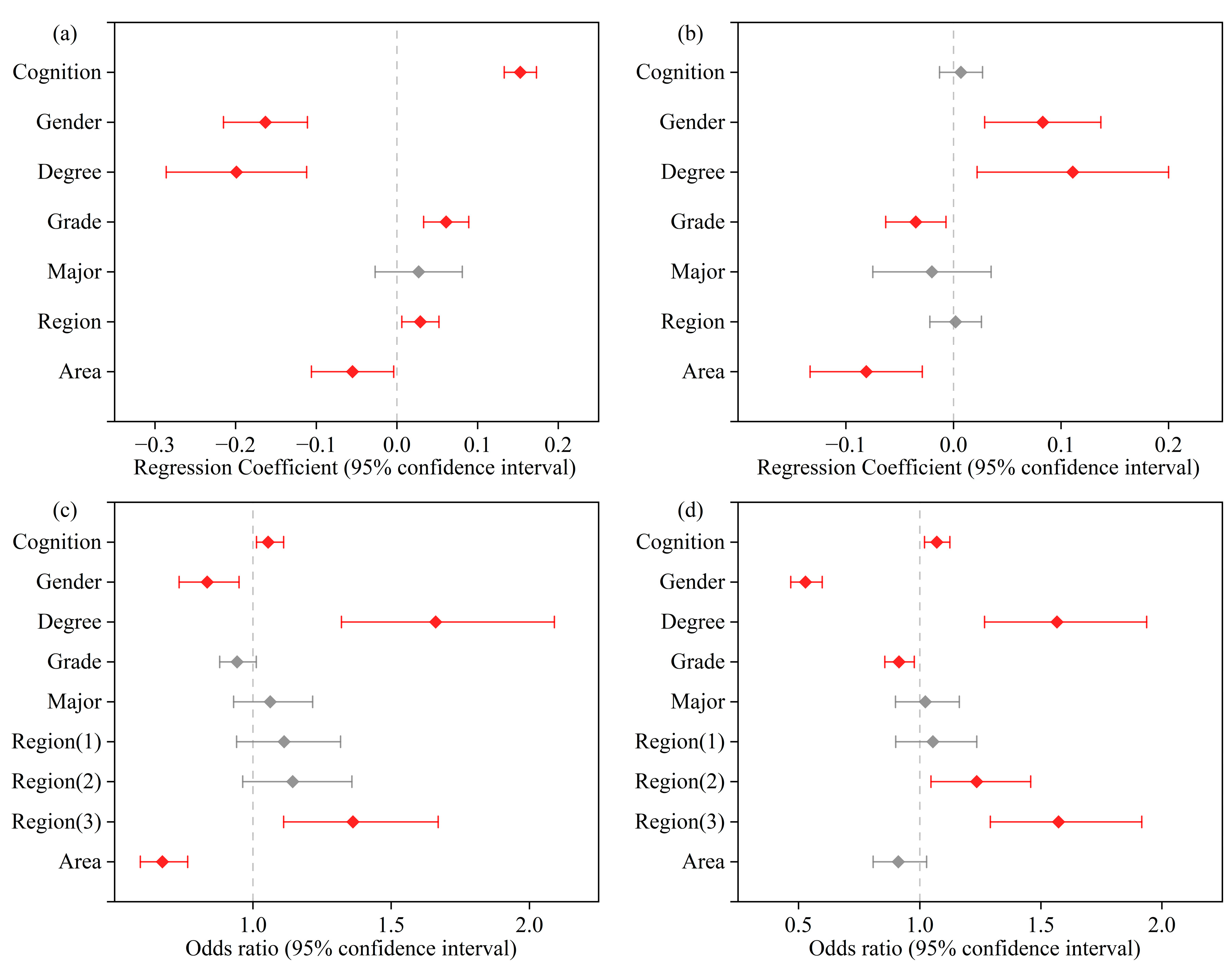

Our findings both align with and diverge from the existing literature on environmental cognition and behavior. Consistent with prior studies [

45,

46], we found that virtual water cognition (VWC) and food–water synergistic cognition (FWSC) positively influence conservation behaviors, supporting the knowledge–action framework. However, unlike studies that assume a straightforward knowledge–attitude pathway [

47], we found that VWC did not significantly enhance FWSC (β = 0.006,

p = 0.758). This indicates a clear knowledge–action gap: technical understanding of virtual water does not automatically translate into experiential cognition that triggers behavioral change. This divergence underscores the need to distinguish between domain-specific technical knowledge and contextualized experiential cognition, an empirical connection that has rarely been made in previous virtual water or water-footprint studies. Our study thus contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how different types of cognition operate within the knowledge–action framework.

4.1. Cognitive Pathways to Food and Water Conservation

Our findings demonstrate that both VWC and perceived FWSC exert positive effects on conservation behaviors, aligning with the knowledge–action framework widely recognized in environmental psychology and behavioral economics. Cognition of virtual water and water footprints constitutes an integral component of environmental knowledge. Enhancing such cognition can strengthen environmental literacy and normative beliefs, thereby increasing perceived behavioral control over water conservation and fostering stronger intentions and practices. This is consistent with previous research [

48]. However, VWC had no statistically significant effect on FCBS. This may be because the concepts of virtual water and water footprints are abstract and not strongly anchored to individuals’ everyday dietary habits, making it difficult for such knowledge to translate directly into tangible food-conservation actions. This suggests that simply increasing technical knowledge of virtual water is unlikely to change young people’s food consumption patterns. Instead, more contextualized and experience-based educational interventions are needed [

49], particularly those that link abstract concepts to relatable scenarios in daily life.

In this study, FWSC was conceptualized as a potential mediator between VWC and conservation behaviors. Yet the hypothesized mediating role was not supported, as the assumed positive relationship between VWC and FWSC was rejected. The unusually weak association between these constructs may be attributable to differences in measurement approaches: VWC focused on understanding technical terminology, while FWSC assessed perceived linkages between everyday practices and resource conservation—perceptions that require less technical expertise. This discrepancy reflected a typical knowledge–action gap: individuals may possess technical environmental knowledge without necessarily perceiving or valuing its cross-domain implications. The inherent abstract nature of the virtual water concept and systemic cognitive barriers may remain uncovered. Moreover, FWSC appeared to depend more on lived experience than on abstract knowledge. Individuals who actively engaged in both food-conservation and water-conservation practices were more likely to recognize their interconnection, suggesting that practical engagement, rather than conceptual familiarity alone, drives synergistic cognition. In knowledge–action terms, VWC captured an abstract understanding of the hidden water content in goods, whereas FWSC entailed an experiential and situational appreciation of how conserving one resource benefits another. Abstract knowledge is prone to dilution without situational cues, whereas concrete, context-embedded cognition is more likely to trigger habitual conservation behaviors.

These findings underscored the need for multi-faceted educational approaches that bridge professional knowledge with lived experiences—integrating scenario-based learning, personal relevance framing, and embodied experiences—to turn abstract concepts into actionable mental models. Beyond their practical value, these results contribute to theoretical debates in environmental cognition by showing that domain-specific VWC and cross-domain FWSC are related but distinct cognitive constructs, each independently influencing behavior. This conceptual distinction challenges the assumption that technical literacy alone is sufficient to generate complex, synergistic conservation behaviors and provides a foundation for refining behavioral models of the food–water nexus.

4.2. Behavioral Spillover and the Mediating Role of Food-Conservation Behaviors (FCBs)

Building on the cognitive pathways identified in

Section 4.1, our analysis further confirmed a significant positive spillover effect of food-conservation behavior on water-conservation behavior, providing empirical support for H4. From the behavioral spillover perspective, engaging in one pro-environmental action can increase the likelihood of performing another related behavior. In our context, individuals who frequently practiced food conservation were also more inclined to adopt water-conservation measures. This linkage may be reinforced by both self-identity and social norms: food-conservation reinforces an individual’s self-perception as a “conserver,” while prevailing societal expectations regarding resource conservation can prompt the adoption of additional, complementary pro-environmental actions.

Further evidence from the Food–Water Behavioral Synergy Model highlighted the pivotal role of food-conservation behavior as a complementary mediator linking both VWC and FWSC to water-conservation behavior. Specifically, VWC and FWSC not only directly enhanced water-conservation practices but also indirectly did so by fostering food-conservation actions. When individuals experienced, through their own behavior, the tangible connection between food and water resources—essentially perceiving “the water embedded in food”—their willingness to conserve water was reinforced. This process amplified the influence of environmental knowledge on actual water-conservation practices, illustrating the bridging role of food-conservation behavior in converting environmental cognition into tangible conservation outcomes.

These findings suggest that promoting food-conservation practices should be seen not only as a valuable conservation goal but also as a strategic mechanism for accelerating the knowledge–action conversion process. For young people in particular, strengthening food-conservation habits offers an effective entry point for fostering broader, synergistic resource conservation behaviors. This mechanism-focused evidence provides a direct basis for the targeted policy and practical recommendations discussed in

Section 4.3.

4.3. Policy and Practical Implications

The empirical insights from

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2 point to the need for targeted, context-sensitive strategies that simultaneously enhance environmental cognition and leverage behavioral spillovers. Accordingly, we propose three interrelated recommendations.

First, virtual water and water-footprint concepts should be deeply integrated into both formal and informal education systems, utilizing concrete cases and practical activities to bridge the cognitive gap and overcome cognitive barriers. The benchmark regression indicates that VWC effectively promotes water-conservation and food-conservation behaviors. However, the Food–Water Behavioral Synergy Model reveals that VWC does not automatically translate into FWSC. This suggests that while students grasp the concept, they fail to establish connections in their daily lives. Concurrently, as shown in the analysis of knowledge acquisition pathways for food- and water-conservation behaviors (

Figure A4), institutional–educational and social–normative channels together account for nearly 90% of all knowledge acquisition pathways, whereas experiential–contextual pathways contribute the least. Specifically, dedicated modules within environmental science, geography, or even general education courses should not only explain the concept of virtual water but also employ concrete, impactful examples (e.g., producing one kilogram of beef requires approximately 15,500 L of water [

50]) to make hidden water usage visible and connect it to everyday choices. In addition, designing scenario-based exercises, such as calculating a meal’s “water footprint” or launching a “Week-long Water-Saving Diet Challenge”, which enable students to establish direct connections between VWC and behaviors through sustained practical activities, effectively breaking down cognitive barriers. Schools, households, and government departments should collaborate to foster a culture of conservation. Education authorities can integrate food–water-conservation content into curriculum standards; communities can organize workshops to disseminate knowledge to families, creating a broader societal atmosphere of resource conservation. Individual actions should be understood within the larger context of the food–water nexus.

Second, differentiated communication and intervention strategies targeting key subgroups and geographic characteristics should be developed. Heterogeneity analysis indicates that VWC influences behavior differently across demographic characteristics and regions. For instance, VWC exerts a greater impact on male water-conservation behaviors while significantly affecting female water-conservation behaviors; it primarily enhances water-conservation behavior scores among water-related majors, whereas it broadly stimulates both behaviors among non-water-related majors. In water-scarce regions, VWC exhibits stronger behavioral conversion effects. During implementation, we must tailor programs to audience characteristics. For males and females: male outreach can emphasize technical, equipment, and infrastructure-based water conservation (e.g., recommending water-efficient appliances); female outreach can focus on daily consumption behaviors, such as meal planning and the direct water-conservation effects of reducing food waste. Regarding majors: For water-related majors, VWC education should deepen and supplement their specialized knowledge. For non-water-related majors, VWC should serve as universal environmental literacy education, emphasizing its importance through short videos and social media to inspire broad environmental behaviors. For regions: In water-scarce areas, information dissemination should closely align with local water stress realities and agricultural irrigation contexts, incorporating experiential learning to reinforce the connection between resource scarcity and behavior. In urban areas, existing initiatives like the “Clean Plate Campaign” can be leveraged to embed the concept of virtual water, enhancing promotion on social media platforms.

Finally, water-footprint labeling should be introduced in food-service settings, employing behavioral nudges to promote synergistic behaviors. The Food–Water Behavioral Synergy Model confirms that food-conservation behavior (FCB) strongly promotes water-conservation behavior (WCB) (H4), demonstrating significant behavioral spillover effects. Simultaneously, our survey indicates that over 60% of respondents believe water footprint labels would influence their food-conservation behavior. Specifically, pilot intuitive water-footprint labels (e.g., using water droplet counts, color coding, or specific liter measurements) to indicate a food item’s virtual water content in university cafeterias, restaurants, or food packaging. This measure can break information barriers at minimal cost, making abstract VWC visible and actionable while reinforcing FWSC, rendering the principle “water conservation through food conservation” tangible. Leveraging behavioral spillover effects, this approach indirectly and efficiently promotes water conservation by encouraging dietary choices, creating a virtuous cycle of behavioral synergy.

Collectively, these measures emphasize concreteness, contextualization, and subgroup sensitivity as essential components for narrowing the knowledge–action gap and leveraging positive behavioral spillovers. When integrated, they provide a coherent framework for translating environmental cognition into sustained, synergistic conservation behaviors.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers valuable insights, several limitations must be acknowledged to contextualize the findings and guide future inquiry.

First, virtual water cognition exhibits sample bias. The disproportionately high proportion of students majoring in water-related majors (32.7%) may have elevated overall virtual water cognition levels and potentially amplified the observed correlations. Consequently, the reported impact effects may represent an upper bound estimate. Future research should actively validate these relationships across more heterogeneous populations, including diverse age groups, educational backgrounds, income levels, and geographic regions. This will help determine the boundary conditions of our model and enhance the external validity of our conclusions, thereby improving the generalizability of our findings.

Second, this study examines the concepts of virtual water and water footprint solely from the perspective of preventing food waste, without delving into other dimensions. While this choice was strategic, it also imposed conceptual boundaries. This limitation restricts a comprehensive understanding of virtual water-driven sustainable behaviors. Future research should integrate other dimensions of virtual water studies, such as dietary choice optimization, water use in production chains, and cross-regional virtual water flows. This approach will provide a more holistic understanding of consumer behavior, complementing the current focus on waste reduction.

Third, methodological limitations warrant consideration. The reliance on self-reported measures for conservation behaviors may introduce social desirability bias, and the cross-sectional design precludes definitive causal inferences. As previously noted, the relationships may evolve over time and be influenced by unmeasured variables like social norms or economic factors. In the future, research should combine cross-sectional surveys with longitudinal tracking (capturing the temporal dynamics of VWC and behaviors) and objective measurements (such as smart water meter data and food waste audits) to enhance validity. Experimental designs (such as testing virtual water education interventions) can further clarify causal relationships.

5. Conclusions

Food conservation is crucial for achieving water-conservation consumption and maintaining global food–water security. Based on a questionnaire survey of 5853 Chinese university students, this study constructed the Food–Water Behavioral Synergy Model, which is embedded within the knowledge–action framework, to examine the impact of virtual water cognition (VWC) on food-conservation behavior (FCB) and water-conservation behavior (WCB) and to explore how behavioral spillovers link these domains. The results indicated that both VWC and food–water synergistic cognition (FWSC) directly enhance FCB and WCB, consistent with the knowledge–action framework. Importantly, VWC and FWSC were not significantly associated (H2: β = 0.006, p = 0.758), providing direct empirical evidence of a knowledge–action gap: technical awareness alone does not reliably generate the cross-domain experiential cognition required for synergistic action. FCB was found to have a strong direct effect on WCB (β = 0.498, p < 0.001) and to mediate the indirect pathways through which VWC and FWSC influence WCB. Daily food-conservation practices thus act as a practical bridge between knowledge and water-conservation actions.

By distinguishing domain-specific technical knowledge from contextualized synergistic cognition, this study demonstrated that within the knowledge–action framework, behavioral spillovers can operationalize cognition into broader resource-conservation outcomes. Practically, the findings suggested that priority should be given to making “virtual water” tangible in everyday food choices to facilitate the translation of awareness into sustainable, synergistic behavior.