Abstract

Studies have shown that natural organic matter can regulate pollutant behavior through multiple pathways; however, research on the environmental behavior of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in typical alkaline calcareous loess soil under the influence of exogenous organic matter remains limited. This study investigated the influence of humic acid (HA), as a representative of natural organic matter, on the sorption behavior of ciprofloxacin (CIP) in sierozem—a typical alkaline calcareous loess soil. Using the batch equilibrium method, we examined how HA affects CIP sorption under various environmental conditions to better understand the environmental fate of VAs in soil–water systems with low organic matrix content. Results showed that CIP sorption onto sierozem involved both fast and slow processes, reaching equilibrium within 2 h, with sorption capacity increasing as HA concentration increased. Kinetic data were well described by the pseudo-second-order model regardless of HA addition, suggesting multiple mechanisms governing CIP sorption, such as chemical sorption reaction, intraparticle diffusion, film diffusion, etc. Sorption decreased with increasing temperature both before and after HA amendment, indicating an exothermic process. Isotherm analysis revealed that both the Linear and Freundlich models provided excellent fits (R2 ≈ 1), implying multilayer sorption dominated by hydrophobic distribution. In ion effect experiments, cations at concentrations above 0.05 mol/L consistently inhibited CIP sorption, with inhibition strength following the order: Mg2+ > K+ > Ca2+ > NH4+, and intensifying with increasing ionic strength. However, HA addition significantly mitigated this inhibition, likely due to complexation between HA’s functional groups (e.g., carboxyl and hydroxyl) and cations, which reduced their competitive effect and enhanced CIP sorption. pH-dependent experiments indicated stronger CIP sorption under acidic conditions. HA addition increased soil acidity, further promoting CIP retention. In summary, HA enhances CIP sorption in sierozem by providing additional sorption sites and modifying soil surface properties. These findings improve our understanding of how exogenous organic matter influences the behavior of emerging contaminants such as antibiotics in soil–water systems, offering valuable insights for environmental risk assessment in semi-arid agricultural regions.

1. Introduction

The extensive use of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in livestock breeding and aquaculture has led to their widespread occurrence as environmental pollutants, drawing increasing attention to their ecological risks and fate, particularly within soil–water systems [1,2]. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics (FQs) are among the most frequently used antibiotics in regions such as China and Europe, applied extensively for animal disease prevention, treatment, and growth promotion [3,4]. However, as animals incompletely metabolize these compounds, 30–90% of administered doses can be excreted into the environment as parent compounds or active metabolites [5]. In China, the common practice of applying manure to improve soil fertility further increases the likelihood of antibiotic entry into soils. Ciprofloxacin (CIP), a typical and widely used fluoroquinolone, exhibits relatively stable chemical properties and contains ionizable functional groups such as a carboxyl group (-COOH), which enhance its potential for complexation with soil components. This interaction reduces its mobility and promotes accumulation in soils, and CIP has been frequently detected in both soil and adjacent water bodies. For example, Shi et al. [6] reported average FQ concentrations in soils around Tianjin exceeding 30 μg/kg—30 times higher than those of macrolide antibiotics (MAs) in the same area.

Once introduced into the soil environment, VAs undergo key environmental processes such as sorption, which strongly influences their transport, transformation, bioavailability, and eventual fate in soil–water systems. As an ionizable compound, the sorption behavior of CIP is regulated by multiple environmental factors. Studies indicate that cations can inhibit CIP sorption by competing for surface sites [7]. Wu et al. [8] demonstrated that the type and charge of interlayer cations in montmorillonites (e.g., Na-, Ca-, and Al-montmorillonite) critically affect CIP sorption. Moreover, variations in pH can alter both the speciation of CIP and the surface properties of soils, further modulating sorption mechanisms. Kong et al. [9] observed decreased CIP sorption with increasing pH, attributing this trend to a shift from electrostatic attraction to repulsion, as well as the enhanced role of hydrogen bonding under acidic conditions. Soil organic matter and clay content are also key factors, with higher levels generally providing more binding sites and enhancing CIP retention. For instance, soils rich in clay and humic acid exhibit stronger sorption capacity for CIP [10].

In real soil–water environments, antibiotics often coexist with other substances, such as humic acid (HA) and various ions. Due to their ionizable nature and multiple functional groups, antibiotics are strongly influenced by such co-existing substances [9]. HA, a common component of soil organic matter, contains abundant functional groups (e.g., -COOH and phenolic -OH) that can interact with both metal ions and organic pollutants. As a macromolecular weak electrolyte carrying a negative charge, the dissociation degree of its functional groups significantly determines its conformational behavior [11]. Studies have shown that HA can regulate pollutant behavior through multiple pathways: (i) acting as a bridge between soil particles and pollutants, (ii) reducing cation loss and moderating competitive sorption, (iii) buffering soil pH, and (iv) increasing soil porosity [12,13,14,15].

Loess, an important alkaline calcareous soil widely distributed in China and other regions, is characterized by low organic matter content and structural vulnerability [16]. These unique physicochemical properties are expected to significantly influence the sorption, migration, and transformation of water-soluble pollutants such as CIP [16]. However, research on the environmental behavior of CIP in such soils—particularly under the influence of exogenous organic matter—remains limited. Several recent studies have investigated the fate of antibiotics in similar loessal soils. For instance, one study employed column leaching experiments to examine the environmental dynamics of CIP and enrofloxacin (ENR) in three loess types following cattle manure application under varying rainfall patterns. The results showed significant sequestration of both antibiotics in the topsoil [16]. Another study systematically explored the sorption–desorption behavior of ENR in loess using integrated kinetic, thermodynamic, and factor-influence experiments [17]. Therefore, investigating the effect of HA on CIP behavior in loess, along with the role of other environmental factors, will help fill critical knowledge gaps regarding the fate of emerging contaminants in soil–water systems and support the control of VAs migration in semi-arid loess agricultural regions.

This study uses sierozem, a typical alkaline calcareous soil from Northwest China, as the test soil, and CIP as a representative FQ. Following the OECD Guideline 106, batch equilibrium experiments were conducted to investigate the sorption behavior of CIP in sierozem under the influence of HA. The study aims to clarify the mechanistic role of HA and other environmental factors in the sorption of FQs in sierozem, providing a theoretical basis and practical reference for controlling FQs accumulation in such soils. The findings are expected to offer scientific support for the environmental management and risk assessment of CIP and other VAs, contributing to ecological and agricultural safety in semi-arid loess regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Chemicals

CIP (AR ≥ 98%) was purchased from Shandong Xiya Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Linyi, China. HA, CaCl2·2H2O, KCl, NH4Cl and NaOH were purchased from Guangdong Guanghua Technology Co., Ltd., Shantou, China. MgCl2·6H2O was purchased from Tianjin Guangfu Technology Development Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China. HCl was purchased from Tianjin Fuyu Fine Chemicals Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China. HA (AR ≥ 90.0%) were purchased from Guangdong Guanghua Technology Co., Ltd., Shantou, China, and its chemical formula is C9H9NO6. All chemicals were analytical grade. The structural morphology and physicochemical properties of CIP are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structural morphology and physicochemical properties of CIP.

2.2. Soil Collection and Characterization

Farmland soil samples (0–20 cm depth) were collected from Gaolan County, Gansu Province, China (103°58′08.7″ E, 36°18′26.3″ N). No antibiotic residues were detected in the sampled soil. After collection, the samples were stored in the dark, air-dried, sieved through a 2 mm mesh, and preserved at 4 °C for subsequent use. The physicochemical properties of the soil were characterized as follows [17]: cation exchange capacity (CEC) was determined by cobalt hexamine chloride ([Co(NH3)6]Cl3) extraction–spectrophotometry and measured at 7.11 cmol/kg; soil organic matter (SOM) content was quantified using a JN-QYF Soil Fertilizer Nutrient Rapid Tester (Zhengzhou Jinnong Technology Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China) and found to be 3.16%; soil pH was measured with a PHS-3C pH meter (Shanghai Precision Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and recorded as 8.07; and particle size distribution was analyzed using a Mastersizer 3000 laser particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 3000, Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Nottingham, UK), revealing clay, silt, and sand contents of 2.43%, 76.84%, and 20.73%, respectively. According to the USDA Soil Taxonomy, it’s generally classified as a Calcids.

2.3. Experimental Methods

The sorption kinetics experiment was conducted following the OECD Guideline 106 batch equilibrium method. In brief, sorption experiments were carried out in 50 mL Teflon and plastic tubes placed in a water bath oscillator operated as a completely mixed bath system. All experiments were conducted under natural pH conditions (pH = 8.07), with no artificial adjustment.

2.3.1. Sorption Kinetics Experiment

Forty centrifuge tubes were divided into 10 groups, with 4 tubes in each group. Each tube was filled with (0.5000 ± 0.0005) g of sierozem. Separately, forty colorimetric tubes were also divided into 10 groups, each containing 4 tubes. To each group of colorimetric tubes, 0, 1, 3, and 5 mL of a 100 mg/L CIP solution were added, and the volume was then adjusted to 25 mL using a 0.01 mol/L CaCl2 solution, yielding CIP concentrations of 0, 4, 12, and 20 mg/L. These prepared solutions were subsequently transferred into the corresponding centrifuge tubes containing the soil samples. All tubes were shaken in the dark at 25 °C and 180 r/min for predetermined time intervals (0, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, 240, 360, and 480 min). After shaking, the tubes were centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 15 min. The supernatant was then filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter, and the absorbance of the filtrate was measured at a wavelength of 265 nm using a spectrophotometer. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are presented as the mean values.

2.3.2. Sorption Thermodynamics Experiment

Eight centrifuge tubes were each loaded with (0.5000 ± 0.0005) g of sierozem. Separately, eight colorimetric tubes were prepared, into which 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.5 mL of 100 mg/L CIP solution were added. Each tube was then brought to a final volume of 25 mL using 0.01 mol/L CaCl2 solution, and the resulting solutions were transferred into the corresponding centrifuge tubes. All tubes were shaken in the dark at 25 °C and 180 r/min for 2 h. After shaking, the tubes were centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane, and the absorbance was measured at 265 nm using a spectrophotometer. The same procedure was repeated at 15 °C and 35 °C.

2.3.3. Ion Type and Strength Experiment

Background solutions (0.01 mol/L) of CaCl2, MgCl2, NH4Cl, and KCl were prepared by dissolving the respective crystalline salts in deionized water. Eight centrifuge tubes were each filled with (0.5000 ± 0.0005) g of sierozem. In parallel, eight colorimetric tubes were prepared. Into each colorimetric tube, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.5 mL of 100 mg/L CIP solution (prepared using the corresponding background solution, e.g., CaCl2) were added. The volume in each tube was adjusted to 25 mL using 0.01 mol/L CaCl2 solution, after which the solutions were poured into the centrifuge tubes. The tubes were shaken for 2 h at 25 °C in the dark at 180 r/min, then centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane, and absorbance was measured at 265 nm. The same methodology was applied for concentrations of 0.05 mol/L and 0.1 mol/L, as well as for other ion types and the control group.

2.3.4. Effect of pH on Sorption Behavior

Eight centrifuge tubes were prepared, each containing (0.5000 ± 0.0005) g of sierozem. Eight colorimetric tubes were also prepared, into which 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.5 mL of 100 mg/L CIP solution were added. The volume in each tube was brought to 25 mL using 0.01 mol/L CaCl2 solution. Before adding the CIP solution, 1–2 drops of 36% hydrochloric acid were added to the centrifuge tubes containing sierozem and allowed to react. The solutions from the colorimetric tubes were then transferred into the centrifuge tubes and mixed thoroughly with a glass rod. The pH was measured and adjusted to 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 using HCl or NaOH solutions. The tubes were shaken for 2 h at 25 °C in the dark at 180 r/min, centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 15 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane.

2.3.5. Sorption Kinetics Experiments at the Presence of HA

Forty centrifuge tubes were divided into 10 groups (4 tubes per group), each containing (0.5000 ± 0.0005) g of sierozem. Forty colorimetric tubes were similarly grouped. Into each group of colorimetric tubes, 0.05, 1, and 3 mL of 5 g/L HA solution were added along with 3 mL of 100 mg/L CIP solution; one tube served as a blank. The total volume was adjusted to 25 mL using 0.01 mol/L CaCl2 solution, and the mixtures were transferred into the corresponding centrifuge tubes. The tubes were shaken in the dark at 25 °C and 180 r/min for predetermined intervals (0, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, 240, 360, 480 min). After shaking, the tubes were centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 15 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and average values are reported.

2.3.6. Sorption Thermodynamics Experiments at the Presence of HA

Eight centrifuge tubes were prepared, each containing (0.5000 ± 0.0005) g of sierozem. Eight colorimetric tubes were also prepared. Into seven of the colorimetric tubes, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.5 mL of 100 mg/L CIP solution were added, along with 3 mL of 5 g/L HA solution; one tube served as a blank. The volume was adjusted to 25 mL using 0.01 mol/L CaCl2 solution, and the solutions were transferred into the centrifuge tubes. The tubes were shaken for 2 h at 25 °C in the dark at 180 r/min, centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 15 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. The same procedure was repeated at 15 °C and 35 °C.

2.3.7. Ion Strength and Type Impact on Sorption at the Presence of HA

Background solutions of CaCl2, MgCl2, NH4Cl, and KCl (0.01 mol/L) were prepared by dissolving the respective crystalline salts in deionized water. Eight centrifuge tubes were prepared, each containing (0.5000 ± 0.0005) g of sierozem. Eight colorimetric tubes were also prepared. Into seven of these tubes, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.5 mL of 100 mg/L CIP solution (prepared using the corresponding background solution, e.g., CaCl2) were added, along with 3 mL of 5 g/L HA solution; one tube served as a blank. The volume was adjusted to 25 mL using 0.01 mol/L CaCl2 solution, and the mixtures were transferred into the centrifuge tubes. The tubes were shaken for 2 h at 25 °C in the dark at 180 r/min, centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 15 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. The same procedure was applied for concentrations of 0.05 mol/L and 0.1 mol/L, as well as for other ion types and the control group.

2.3.8. Effect of pH on Sorption Behavior at the Presence of HA

Eight centrifuge tubes were prepared, each containing (0.5000 ± 0.0005) g of sierozem. Eight colorimetric tubes were also prepared. Into seven of the colorimetric tubes, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.5 mL of 100 mg/L CIP solution were added, along with 3 mL of 5 g/L HA solution; one tube served as a blank. The remaining steps are the same as those in Section 2.3.4.

2.4. Data Processing

To investigate the sorption mechanism of CIP on sierozem before and after the addition of HA, the experimental data were fitted using the pseudo-first-order kinetic model (), pseudo-second-order kinetic model (), and intraparticle diffusion model () [18,19]. In these models, q1 and q2 represent the equilibrium sorption capacity (mg/g), qt denotes the sorption amount at time t (mg/g), K1 and K2 are the rate constants of the pseudo-first-order (min−1) and pseudo-second-order (g/(mg·min)) models, respectively, and KP is the intraparticle diffusion rate constant (mg/(g·min1/2)).

To examine the sorption thermodynamics of CIP on sierozem before and after HA addition, the Freundlich () [20], Langmuir [21], and Linear ( sorption models were applied for fitting. In these models, Cs represents the sorption capacity of sierozem for CIP (mg/g); Ce is the equilibrium concentration of CIP in solution (mg/L); Qmax denotes the maximum sorption capacity of CIP on sierozem (mg/g); KL is the Langmuir sorption constant (L/g); KF and Kd are the sorption constants for the Freundlich and Linear models, respectively; and 1/n is the Freundlich empirical constant. The equilibrium data were initially analyzed using the above models, and subsequent calculations and plotting were performed using Excel and the trial version of Origin.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Kinetic Characteristics of CIP Sorption on Sierozem Before and After Adding HA

Sorption kinetics reflect the relationship between sorption capacity and time, providing insight into the temporal variation in CIP sorption in alkaline calcareous soil. In this study, the batch equilibrium method was employed to examine the sorption behavior of CIP in loess, both before and after the addition of HA. The results are presented in Figure 1a–d. As shown in Figure 1, the sorption process of CIP on sierozem in a single system can be divided into three distinct stages: a rapid sorption phase from 0 to 30 min, a slow sorption phase from 30 min to 2 h, and an equilibrium phase after 2 h. This pattern is consistent with the sorption stages previously described by Liu et al. [22].

Figure 1.

Fitting curves, and intraparticle diffusion fitting curves for the kinetic sorption of CIP on sierozem. (a) Pseudo-first/pseudo-second models fitting curve on sierozem; (b) Intra-diffusion fitting curve on sierozem; (c) Pseudo-first/pseudo-second models fitting curve on sierozem with different HA contents; and (d) Intra-diffusion fitting curve on sierozem with different HA contents.

During the fast sorption stage, over 97% of the equilibrium sorption capacity of CIP on sierozem is attained. At this phase, the pollutant has just entered the soil environment, where abundant sorption sites are available on soil aggregates. The reactions are predominantly physical, with the sorption rate exceeding the desorption rate and relatively low activation energy required. In the slow sorption stage, surface sorption sites become fully occupied, and CIP begins to overcome resistance to enter the internal structure of soil aggregates. The reactions shift toward being more chemical in nature, requiring higher activation energy. Finally, in the sorption equilibrium stage, the change in CIP amount adsorbed by the soil over time becomes negligible.

Furthermore, the sorption amount of CIP on loess is positively correlated with its concentration. This is attributed to the increased collision probability between CIP molecules and soil aggregates at higher concentrations, which enhances the driving force for sorption. The effect of different initial CIP concentrations is mainly reflected in the variation in the equilibrium sorption capacity of sierozem. As the initial CIP concentration increases from 4 to 20 mg/L, the equilibrium sorption capacity rises from 0.142 to 0.756 mg/g, indicating that within this range, higher CIP concentrations promote sorption by sierozem. It is hypothesized that at low initial concentrations, sufficient sorption sites are available on the soil surface, and low CIP concentrations do not fully occupy these sites. As the concentration increases, the higher molecular dynamics reduce resistance between solid and liquid phases, promote effective collisions between adsorbate and adsorbent, and facilitate binding of CIP to sorption sites, thereby increasing sorption capacity [23].

After the addition of HA, the sorption process of CIP on loess still follows the same three-stage pattern, indicating a consistent mechanism. However, the introduction of HA enhances the sorption capacity of CIP, with the increase proportional to the HA concentration. The sorption amounts increased by 1.13%, 6.16%, and 9.28% at the three HA concentrations tested, respectively. This enhancement may be attributed to HA modifying the soil surface and providing additional hydrophobic sites, facilitating the transition of CIP from the aqueous to the solid phase [24,25]. Moreover, HA can form bridges between pollutants and soil, further promoting sorption. Brigante et al. [26] demonstrated this effect in their study on paraquat sorption on goethite, where the addition of HA significantly improved sorption capacity, approaching 100%. Similarly, Liu et al. [27] reported that HA enhances CIP sorption through hydrogen bonding and ion exchange interactions.

To further investigate the sorption mechanism, the experimental data were fitted using the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order kinetic models, and the intraparticle diffusion model, with the results presented in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, the sorption processes—both with and without HA addition—were better described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, indicating that chemical sorption dominates the process. Previous studies in our laboratory on various pesticides, petroleum hydrocarbons, and antibiotic pollutants have consistently shown that contaminant sorption in soils generally follows pseudo-second-order kinetics. This may be attributed to the presence of channels on soil particle surfaces that allow access to internal sites, where multi-layer sorption occurs, dominated by chemical interactions [28]. When the intraparticle diffusion model was applied to the CIP sorption process before and after HA addition, the fitted line did not pass through the origin, suggesting that intraparticle diffusion is not the sole rate-limiting step. Other mechanisms, such as liquid film diffusion, also contribute to the overall process [9].

Table 2.

Kinetic fitting parameters for the sorption of CIP on sierozem at different concentrations of CIP and 12 mg/L CIP with varying amounts of HA.

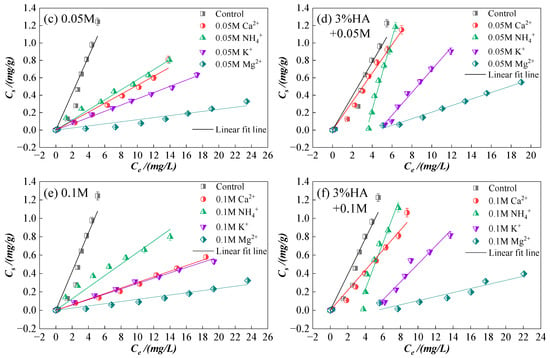

3.2. Thermodynamic Characteristics of CIP Sorption on Sierozem Before and After Adding HA

Thermodynamic experiments reflect the relationship between sorption capacity and temperature, aiming to investigate how the sorption of CIP on alkaline calcareous soil varies with temperature. This relationship also indicates the strength of interaction between the adsorbent and adsorbate. The results are shown in Figure 2a,b. As seen in the figure, in both the presence and absence of 3% HA, the sorption capacity of CIP decreases as the temperature rises from 15 °C to 35 °C—from 1.222 mg/g and 1.324 mg/g to 1.067 mg/g and 1.288 mg/g, respectively. This decline suggests that sierozem exhibits a stronger sorption capacity for CIP at lower temperatures. This behavior can be attributed to the temperature-dependent solubility of CIP: at lower temperatures, CIP is less soluble in water, favoring hydrophobic interactions and enhancing sorption. As temperature increases, solubility improves, weakening hydrophobic interactions and making sorption onto loess particles less favorable [23]. Excessively high temperatures also alter the equilibrium sorption capacity, reducing the number of CIP molecules entering the solid phase at equilibrium and resulting in a negative trend in sorption capacity [29]. Regardless of temperature, however, the addition of HA consistently enhances the sorption of CIP by the soil.

Figure 2.

Thermodynamic model fitting curves of CIP sorption on sierozem. (a) Soil, and (b) Soil with presence of 3% HA.

The Linear, Langmuir, and Freundlich models were applied to fit the sorption data of CIP on sierozem at different temperatures, with the results summarized in Table 3. Both before and after HA addition, the sorption isotherms of CIP on loess were better described by the Freundlich (R2 > 0.949) and Linear models (R2 > 0.895), whereas the Langmuir model exhibited poorer fitting performance. The negative value obtained for the saturated sorption capacity parameter (Qm) further confirms that the Langmuir model is unsuitable for describing CIP sorption on sierozem. This observation aligns with the findings of Conde-Cid et al. [30], who reported that the Freundlich model effectively described pollutant sorption across 63 agricultural soils. Previous studies in our laboratory have also demonstrated that CIP sorption on Northwest loess conforms to both the Freundlich (R2 > 0.960) and Linear (R2 > 0.908) isotherm models [31].

Table 3.

Thermodynamic fitting parameters for CIP sorption on sierozem and sierozem with 3% HA.

The Freundlich model describes a non-ideal sorption state characterized by heterogeneous multi-layer adsorption. The nonlinear index (n) and the sorption coefficient (KF) can be used to evaluate the sorption capacity of CIP on sierozem [32]. The KF value reflects the affinity of sierozem for CIP, with higher values indicating stronger sorption capacity. The n value describes the nonlinearity of the sorption process: when n is close to 1, the process approaches ideal behavior, where sorption increases proportionally with concentration; if n < 1, strong nonlinearity is observed, meaning the sorption rate lags behind the increase in contaminant concentration; if n > 1, the sorption process is facilitated, with the sorption rate increasing faster than the contaminant concentration. According to the fitting results, both in the single system and the HA-amended system, the KF values are highest at 15 °C, indicating reduced mobility of CIP in sierozem at low temperatures and a greater tendency to persist in the soil, thereby increasing contamination risks. As temperature increases, KF values decrease in both systems, suggesting that elevated temperatures weaken the sorption capacity of sierozem for CIP. In contrast, all n values obtained in this study are below 1, which differs from the findings of Jiang et al. [33], who reported n values for CIP in loess exceeding 1 with rising temperature. This discrepancy further confirms that the presence of HA alters the sorption behavior in the soil.

The sorption affinity constant (Kd) was also calculated to assess the temperature dependence of the process. As temperature increased, Kd values in both systems slightly decreased, indicating that the sorption of CIP on sierozem is an exothermic process. The Kd value is commonly used to describe the migration potential and bioavailability of a substance and serves as an indicator of soil sorption capacity. A higher Kd value corresponds to more pollutants being adsorbed onto the soil matrix, whereas a lower value implies a greater proportion remains in the solution. The observed decrease in Kd with increasing temperature further confirms that higher temperatures enhance CIP solubility, weaken hydrophobic interactions, and reduce the affinity of CIP for loess particles. Some studies also suggest that rising temperatures cause soil organic matter to transition from a rigid glassy state to a flexible rubbery state, effectively reducing the content of functional organic matter and making it more difficult for CIP to adsorb onto loess surfaces, thereby decreasing sorption [23].

Notably, the Kd values in the HA-amended system were consistently higher than those in the single system, indicating that HA significantly enhances the sorption affinity of soil for CIP. However, the Kd values obtained in this study were considerably lower than those reported by Cui et al. [34] for paddy soils and by Gao et al. [35] for kaolin, both of which have higher organic matter contents. This comparison suggests that the sorption capacity of sierozem for CIP is substantially weaker than that of paddy soils and kaolin, further underscoring the key role of organic matter in the soil’s ability to retain pollutants. Collectively, these analyses demonstrate the sorption process of CIP on sierozem is governed by multiple mechanisms rather than a single dominant factor.

3.3. Effect of Ion Type and Strength on CIP Sorption on Sierozem Before and After HA Addition

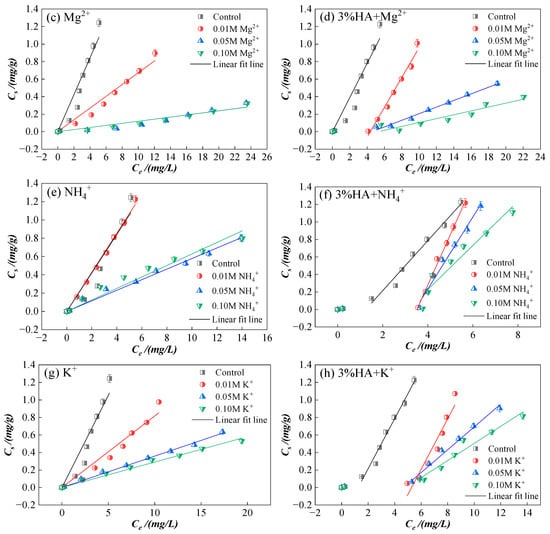

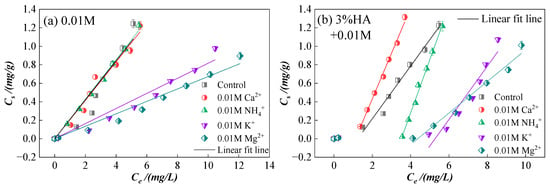

Variations in ion type and ionic strength can affect the interactions between adsorbates and adsorbents. Generally, changes in ionic strength affect both electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. Electrolyte ions may alter sorption behavior through multiple mechanisms: ion exchange with adsorbate ions, salting-out or salting-in effects, modification of macromolecular adsorbate size in solution, or formation of ion pairs with adsorbate ions [36]. To examine how different ion types and strengths affect CIP sorption on sierozem, both before and after HA addition, a systematic study was conducted. The results are presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Sorption isotherms of CIP on sierozem under different ion strengths in the single system and after adding 3% HA. (a) Effect of the different strengths of Ca2+; (b) At the presence of HA under different strengths of Ca2+; (c) Effect of the different strengths of Mg2+; (d) At the presence of HA under different strengths of Mg2+; (e)Effect of the different strengths of NH4+; (f) At the presence of HA under different strengths of NH4+; (g) Effect of the different strengths of K+; (h) At the presence of HA under different strengths of K+.

Figure 4.

Sorption isotherms of CIP on sierozem under the different ions in the single system and after adding 3% HA. (a) Under 0.01 M with different ions; (b) At the presence of HA under different ions with 0.01 M; (c) Under 0.05 M with different ions; (d) At the presence of HA under different ions with 0.05 M; (e) Under 0.1 M with different ions; (f) At the presence of HA under different ions with 0.1 M.

As shown in Figure 3, for the same ion type at varying concentrations, higher ion concentrations correspond to lower CIP sorption on sierozem. This observation aligns with previous studies indicating that increased ionic strength compresses the electric double layer [37], thereby weakening electrostatic interactions between adsorbate and adsorbent. Under high ionic strength, counterions accumulate near oppositely charged sorption sites, partially neutralizing site charges and reducing electrostatic attraction. When electrostatic attraction dominates between adsorbent and adsorbate, increased ionic strength generally suppresses sorption; conversely, when electrostatic repulsion prevails, higher ionic strength may enhance sorption [38]. In this study, elevated ionic strength consistently reduced CIP sorption on sierozem. The addition of 3% HA increased CIP sorption compared to the system without HA, further confirming that HA promotes CIP retention in sierozem. Beyond the mechanisms previously discussed, Murphy et al. [39] reported that HA-amended soils exhibit higher sorption of organic pollutants under low ionic strength conditions, as the more “open” HA structure at low ionic strength facilitates pollutant uptake [40].

Figure 4 illustrates that at low concentration (0.01 mol/L), Ca2+ and NH4+ have minimal impact on CIP sorption, even slightly promoting it, whereas Mg2+ and K+ inhibit sorption, with the inhibitory effect following the order: Mg2+ > K+. At higher concentrations (>0.05 mol/L), all ions inhibit CIP sorption, with inhibition strengthening as cation concentration increases. The overall inhibition order is: Mg2+ > K+ > Ca2+ > NH4+. This trend differs from the findings of Yang et al. [41], likely due to differences in antibiotic structure and local environmental conditions. The initial promotion of sorption by low concentrations of Ca2+ and NH4+ may be attributed to cation bridging. However, as ion concentration increases, enhanced electrostatic interactions in the system reduce the collision frequency between sierozem and CIP, thereby decreasing sorption [23]. Compared to Ca2+, NH4+ undergoes hydrolysis to release H+, promoting acidic conditions that favor the presence of CIP as CIP+ cations. These cations then participate in cation exchange with the soil surface, enhancing sorption. Divalent cations such as Ca2+ carry more charge than monovalent NH4+, leading to stronger electrostatic interactions with the soil and reduced accessibility of CIP to sorption sites. K+, with its higher solubility and more uniform distribution in aqueous solution, may exert a stronger inhibitory effect even at low concentrations. In contrast, Ca2+ has lower solubility and less uniform distribution, potentially diminishing its relative impact. At low concentrations, K+ may enhance inhibition by compressing the soil surface double layer. As K+ concentration increases, it competes more effectively with CIP for negatively charged sites. Mg2+, with its smaller ionic radius (72 pm vs. 138 pm for K+) and higher charge density, binds more strongly to soil colloids and plays a more significant role in both inhibiting CIP sorption and promoting soil aggregation compared to K+ [23,42].

Following the addition of HA, except for the Ca2+ treatment group—where HA consistently and significantly alleviates the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ on CIP sorption—the other ions exhibit a distinct trend: the sorption affinity constant (Kd) initially decreases and then increases sharply. This pattern suggests that these ions can bind to carboxyl and hydroxyl groups on the HA surface, thereby reducing the effective ion concentration in solution and subsequently enhancing CIP sorption by sierozem [43]. Compared to other ions, Ca2+ binds more rapidly and readily with HA. In contrast, other ions must first compete with HA for sorption sites on the soil surface before undergoing modification through interaction with HA functional groups.

At low ionic strength (0.01 mol/L), NH4+ exhibits a stronger inhibitory effect compared to Ca2+. However, as the ionic strength increases (>0.05 mol/L), the relative effects of NH4+ and Ca2+ are reversed. This shift may be attributed to the fact that at low concentrations, both HA and NH4+ carry net charges—HA being predominantly negative and NH4+ positive—leading to charge neutralization on the soil particle surface. Functional groups in HA, such as -COOH and -OH, can also compete with NH4+ for sorption sites. Tomza-Marciniak et al. [44] similarly observed that HA competes with NH4+ via its functional groups, influencing NH4+ behavior in soil. As ionic strength rises, HA becomes saturated through interaction with excess NH4+, and a fraction of NH4+ begins to exert a slight promotive effect. In contrast, Ca2+, as noted earlier, becomes surrounded by counterions at high ionic strength, partially neutralizing sorption site charges and weakening electrostatic interactions between the adsorbent and adsorbate. Consequently, the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ exceeds that of NH4+ under these conditions.

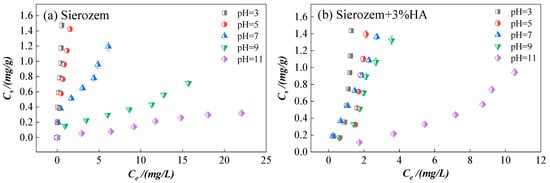

3.4. Effect of pH on CIP Sorption on Sierozem Before and After Adding HA

Changes in solution pH within the sorption system influence not only the surface charge and charge density of the soil but also significantly alter the speciation of CIP, thereby affecting its sorption behavior. As an ionizable compound, CIP exhibits different molecular forms under varying pH conditions (Table 1). This study examines changes in CIP sorption on sierozem at 25 °C across different pH levels, both with and without HA addition. As shown in Figure 5, the influence of pH on CIP sorption is consistent in both systems. When pH increased from 3 to 11, the sorption capacity of CIP on sierozem decreased markedly from 1.472 mg/g and 1.436 mg/g to 0.318 mg/g and 0.944 mg/g, respectively, indicating a clear trend of declining sorption with increasing pH.

Figure 5.

Sorption of CIP on sierozem at different pH levels. (a) Sierozem; (b) Addition of 3% HA + Sierozem.

This behavior can be explained by the pH-dependent speciation of CIP and the corresponding changes in soil surface properties. At pH = 3, CIP exists predominantly in its cationic form (–NH2+), while the soil surface is largely negatively charged. Under acidic conditions, the protonated amino group of CIP interacts with negatively charged π-systems on the soil surface through π-π electron–donor–acceptor (EDA) interactions, leading to substantial sorption onto soil particles. The slightly lower sorption observed in the HA-amended system compared to the HA-free system may be attributed to the tendency of cationic CIP to interact preferentially with HA, as reported in previous studies [45]. As pH increases from 3 to 9, CIP transitions to a zwitterionic form, carrying both positive and negative charges while remaining electrically neutral overall [46]. The proportion of cationic CIP decreases significantly, weakening electrostatic attraction. Consequently, the sorption mechanism shifts from ion exchange and electrostatic interactions toward hydrophobic partitioning. The sorption capacity of CIP decreases from 1.472 mg/g and 1.436 mg/g to 0.713 mg/g and 1.322 mg/g in the respective systems. In this zwitterionic state, sorption is governed by relatively weak interactions such as cation-π bonding, π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding, or hydrophobic effects. Notably, CIP± exhibits stronger hydrophobicity than its cationic form [46,47]. At pH = 11, CIP exists primarily in its anionic form. With almost no cations available to interact with the negatively charged soil surface, sorption capacity drops to only 0.318 mg/g and 0.944 mg/g in the two systems. Overall, as pH increases from 3 to 11, the sorption capacity of CIP on sierozem consistently decreases. This inverse relationship between soil antibiotic sorption and pH has also been documented by Zhang et al. [48].

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the effect and mechanism of humic acid (HA) on ciprofloxacin (CIP) sorption in loess soil. The sorption process of CIP on sierozem was identified as a composite process controlled by multiple mechanisms, exhibiting both rapid and slow sorption stages before reaching equilibrium within 2 h. The introduction of HA significantly enhanced CIP sorption, primarily through three interrelated mechanisms: forming molecular bridges between pollutants and soil particles, modifying soil surface properties, and providing additional hydrophobic sites that facilitate CIP transition from the aqueous to solid phase. Furthermore, HA promoted CIP sorption via hydrogen bonding and ion exchange interactions. Temperature exerted a crucial influence on the sorption process by modulating CIP solubility. Elevated temperature increased CIP solubility, weakened hydrophobic interactions, and consequently reduced sorption efficiency on loess particles. Ionic strength also played a significant role, with higher concentrations increasingly inhibiting CIP sorption according to the order: Mg2+ > K+ > Ca2+ > NH4+. This inhibition pattern resulted from the complex interplay of ion exchange, cation bridging, ionic solubility, charge density, and electrostatic interactions.

This research provides novel insights into the unique facilitating role of HA in antibiotic sorption within low-organic-matter loess systems, contrasting with its typical inhibitory effects in organic-rich soils. The findings establish a quantitative framework linking critical environmental factors (temperature, ionic composition, pH) with CIP sorption behavior, offering fundamental data for predicting antibiotic fate in arid and semi-arid regions. The elucidated mechanisms of mineral–HA–pollutant interactions contribute significantly to developing targeted remediation strategies for antibiotic-contaminated soils in cold, dryland agricultural systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Q.; Validation, Y.Y.; Formal analysis, Y.Y. and Z.G.; Investigation, Y.W.; Resources, Y.W. and L.Z.; Data curation, Y.Y.; Writing—original draft, C.Q.; Writing—review & editing, Y.J.; Visualization, L.Z. and Z.G.; Supervision, Y.J.; Project administration, Y.J.; Funding acquisition, Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 21966020.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the financial supporting of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21966020).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Zang, J.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, F.; Jiang, L.; Xing, X.; Wang, N.; Fu, C. Antibiotic residues of drinking-water and its human exposure risk assessment in rural Eastern China. Water Res. 2023, 236, 119940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Ho, K.W.K.; Ying, G.G.; Deng, W.J. Veterinary antibiotics in food, drinking water, and the urine of preschool children in Hong Kong. Environ. Int. 2017, 108, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, K.; Xu, P.; Ok, Y.; Jones, D.L.; Zou, J. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in agricultural soils: A systematic analysis. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Dong, Y.H.; Wang, H. Residues of veterinary antibiotics in manures from feedlot livestock in eight provinces of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Ye, B.; Wang, L. Antibiotics in soil and water in China–a systematic review and source analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Cai, Y. Investigation of fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides and macrolides in long-term wastewater irrigation soil in Tianjin, China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012, 89, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wei, Q.; Farooq, U.; Lu, T.; Chen, W.; Qi, Z. The mechanisms involved into the inhibitory effects of ionic liquids chemistry on adsorption performance of ciprofloxacin onto inorganic minerals. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 648, 129422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, Z.; Hong, H. Influence of types and charges of exchangeable cations on ciprofloxacin sorption by montmorillonite. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2012, 27, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, G.; Ma, F.; Wu, Y. Sorption of ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin on alkaline cropland soil in semiarid regions: Roles of pH, ionic strength, and ion type. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasket, A.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Krzmarzick, M.; Gustafson, E.; Deng, S. Clay content played a key role governing sorption of ciprofloxacin in soil. Front. Soil Sci. 2022, 2, 814924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standal, S.H.; Blokhus, A.M.; Haavik, J.; Skauge, A.; Barth, T. Partition coefficients and interfacial activity for polar components in oil/water model systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1999, 212, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, E.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Aar, G.; Argin, S. Humic + Fulvic acid mitigated Cd adverse effects on plant growth, physiology and biochemical properties of garden cress. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Shan, Y.; Nie, W.; Sun, Y.; Su, L.; Mu, W.; Qu, Z.; Yang, T. Humic acid improves water retention, maize growth, water use efficiency and economic benefits in coastal saline-alkali soils. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 309, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandra, B.; Tall, A.; Vitková, J.; Procházka, M.; Šurda, P. Effect of humic amendment on selected hydrophysical properties of sandy and clayey soils. Water 2024, 16, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, I.; Kodaolu, B.; Audette, Y.; DS Smith, D.S.; Longstaffe, J. Acid–base properties of humic acid from soils amended with different organic amendments over 17 years in a long-term soil experiment. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2025, 89, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Nan, Z.; Kong, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Y. Enhanced adsorption and leaching behavior of fuoroquinolone antibiotics in soil amended with cattle manure under varying rainfall condition. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Jia, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C.; Yao, Y.; Wu, Y. Mineral-driven sorption and irreversible sequestration of enrofloxacin in arid loess: Mechanistic insights for sustainable antibiotic management. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.; McKay, G. The kinetics of sorption of basic dyes from aqueous solution by sphagnum moss peat. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1998, 76, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.J., Jr.; Morris, J. Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. J. Sanit. Eng. Div. 1963, 89, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Über die Adsorption in Lösungen. Z. Phys. Chem. 1906, 57, 385–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; He, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Diao, J.; Wu, Y. Adsorption and retention capacity and influencing factors of tylosin on loess. Res. Environ. Sci. 2024, 37, 2006–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Liang, X.; Yuan, L.; Nan, Z.; Deng, X.; Wu, Y.; Ma, F.; Diao, J. Effect of livestock manure on chlortetracycline sorption behaviour and mechanism in agricultural soil in Northwest China. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 415, 129020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J. Preparation, Physicochemical Properties of Humic Acid/Chitosan/Silica Aerogel Composite Adsorbent and Its Application in the Adsorption of Deltamethrin. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Ya’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Cheng, J.; Jing, J.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, A. Effect of humic acid on ciprofloxacin removal by magnetic multifunctional resins. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigante, M.; Zanini, G.; Avena, M. Effect of humic acids on the adsorption of paraquat by goethite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 184, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Liu, Y.; Meng, W.; Zheng, B. Adsorption of sulfamethoxazole (SMZ) and ciprofloxacin (CIP) by humic acid (HA): Characteristics and mechanism. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 50449–50458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, A.; İnci, İ.; Baylan, N. A comparative adsorption study with various adsorbents for the removal of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride from water. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2019, 230, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Guan, L.; Kong, Y.; Jing, Z. Adsorption properties of phosphorus in water by modified activated carbon coated with LDHs. Appl. Chem. Ind. 2024, 53, 574–578. [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Cid, M.; Fernández-Calviño, D.; Nóvoa-Muñoz, J.C.; Fernández-Calvinho, D.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E.; Fernández-Sanjurjo, M.J. Experimental data and model prediction of tetracycline adsorption and desorption in agricultural soils. Environ. Res. 2019, 177, 108607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Yuan, L. Adsorption mechanism and influencing factors of ciprofloxacin on loess. China Environ. Sci. 2019, 39, 4262–4269. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L.P.; Yuan, X.X.; Liang, J.Y.; Guan, S.; Du, H. Adsorption characteristics and simulation of metazosulfuron in soils. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2022, 24, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatello, J.J.; Xing, B. Mechanisms of slow sorption of organic chemicals to natural particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wang, S.P. Adsorption characteristics of ciprofloxacin in ustic cambosols. Environ. Sci. 2012, 33, 2895–2900. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P.; Mo, C.H.; Li, Y.W.; Wu, X.L.; Zou, X.; Huang, X.D. Preliminary study on the adsorption of quinolones to kaolin. Environ. Sci. 2011, 32, 1740–1744. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H. Research progress on mechanisms about the effect of ionic strength on adsorption. Environ. Chem. 2010, 29, 997–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, D.; Liao, P.; Yuan, S. Effects of ionic strength and cationic type on humic acid facilitated transport of tetracycline in porous media. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 284, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.M.; Zachara, J.M.; Smith, S.C.; Phillips, J.L.; Wietsma, T.W. Interaction of hydrophobic organic compounds with mineral-bound humic substances. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1994, 28, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.Y. Effect of straw-bentonite-polyacrylamide composites on nitrogen adsorption of sandy soil. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2012, 28, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Kong, W.; Wang, W.; Wu, Y. Study on the adsorption process and mechanism of oxytetracycline in different loess: Roles of soil characteristics and influencing factors. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, J.; Liu, L.; Tan, W.; Hao, R.; Qiu, G. Catalytic oxidation and adsorption of Cr (III) on iron-manganese nodules under oxide conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 122166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xia, Y.; Yuan, L.; Xia, K.; Jiang, Y.; Li, N.; He, X. Molecular dynamics simulation of the interaction between common metal ions and humic acids. Water 2020, 12, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomza-Marciniak, A.; Pilarczyk, B.; Drozd, R.; Pilarczy, R.; Juszczak-Czasnojć, M.; Havryliak, V.; Podlasińska, J.; Udała, J. Selenium and mercury concentrations, Se: Hg molar ratios and their effect on the antioxidant system in wild mammals. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 322, 121234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristilde, L.; Sposito, G. Binding of ciprofloxacin by humic substances: A molecular dynamics study. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifmand, M.; Sepehr, E.; Rasouli-Sadaghiani, M.H.; Asri-Rezaei, S.; Rengel, Z. Antibiotics pollutants in agricultural soil: Kinetic, sorption, and thermodynamic of ciprofloxacin. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłosińska-Szmurło, E.; Pluciński, F.A.; Grudzień, M.; Betlejewska-Kielak, K.; Biernacka, J.; Mazurek, A.P. Experimental and theoretical studies on the molecular properties of ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, pefloxacin, sparfloxacin, and gatifloxacin in determining bioavailability. J. Biol. Phys. 2014, 40, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, C.; Dang, Z.; Huang, W. Sorption of tylosin on agricultural soils. Soil Sci. 2011, 176, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).