Hydrological Sensitivity to Land-Use and Climate Change in the Asa Watershed, Nigeria

Abstract

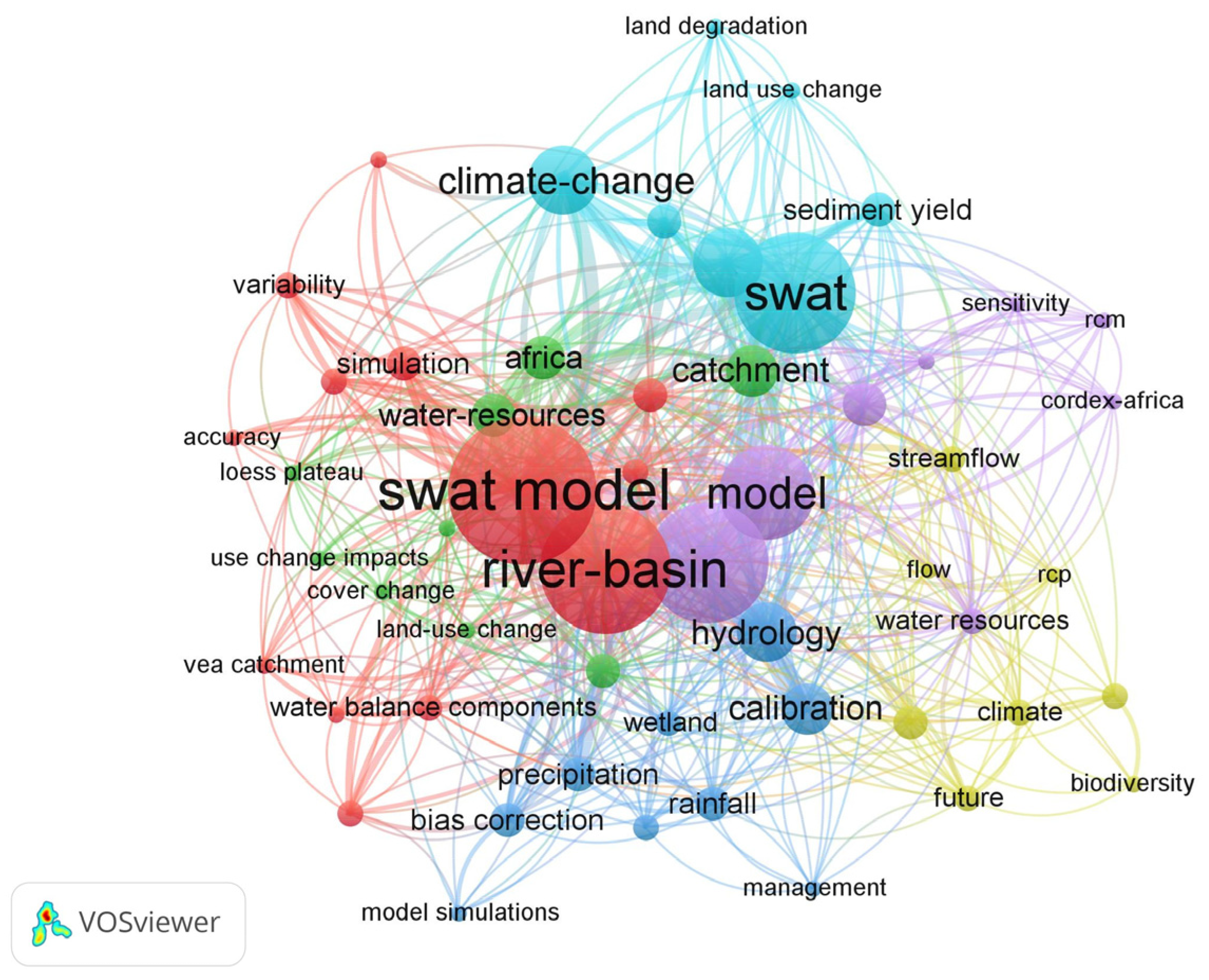

1. Introduction

Water Yield in the Asa Watershed

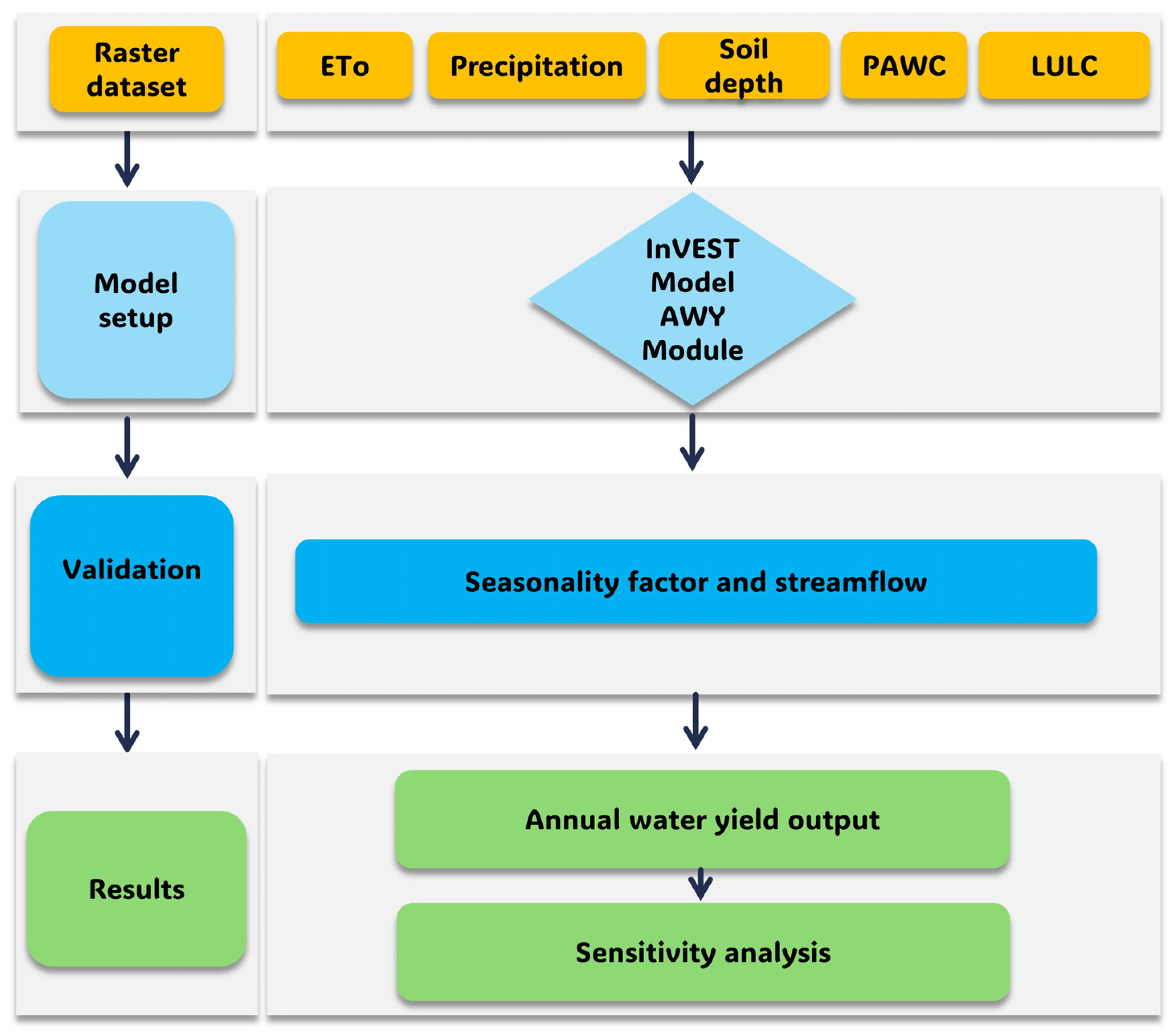

2. Methodology

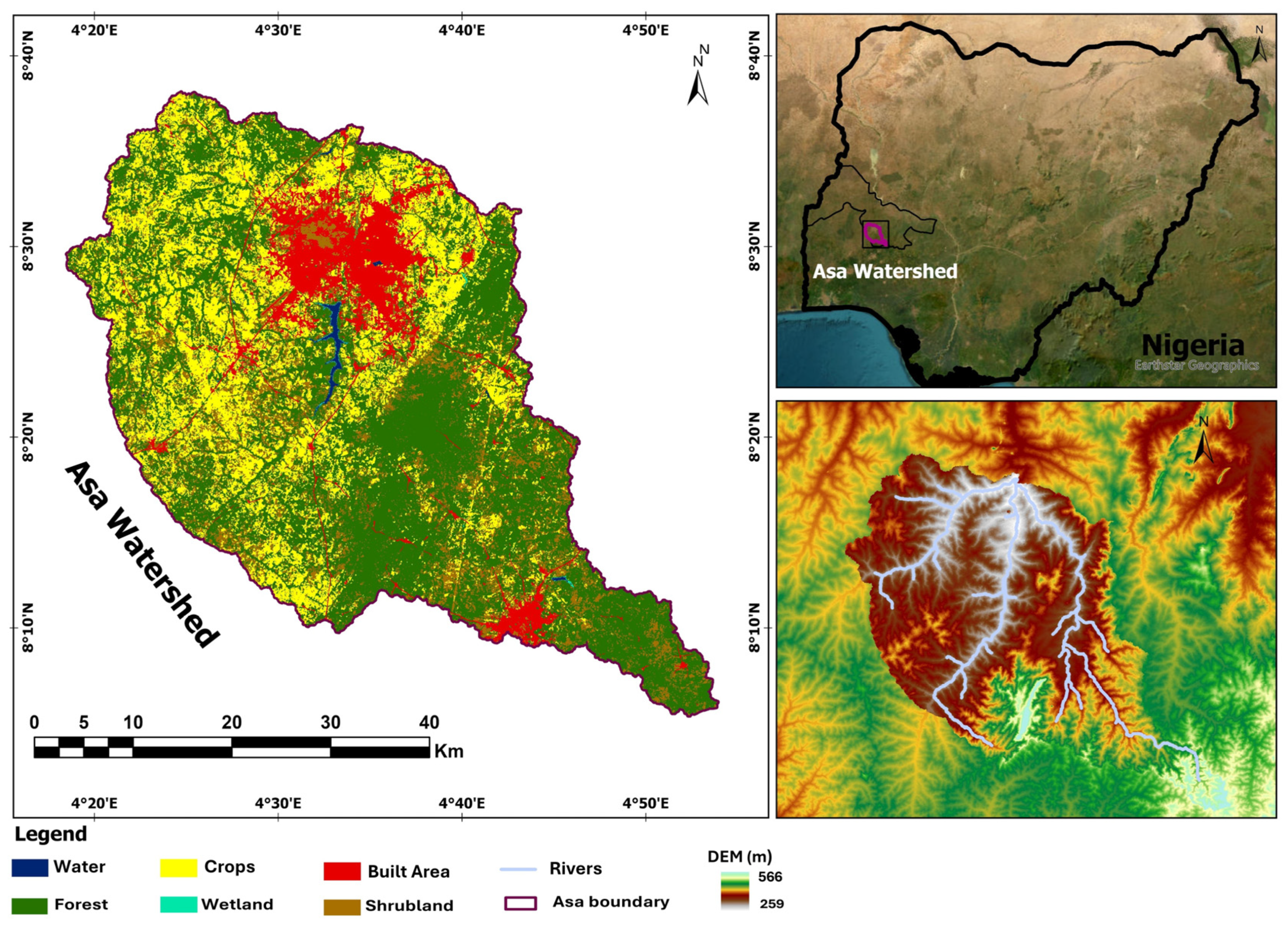

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Modeling Water Yield Dynamics with InVEST

2.2.1. InVEST Water Yield Model

2.2.2. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.2.3. Calibration and Validation

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Water Yield Drivers

Surrogate Interpretable Analysis

3. Results

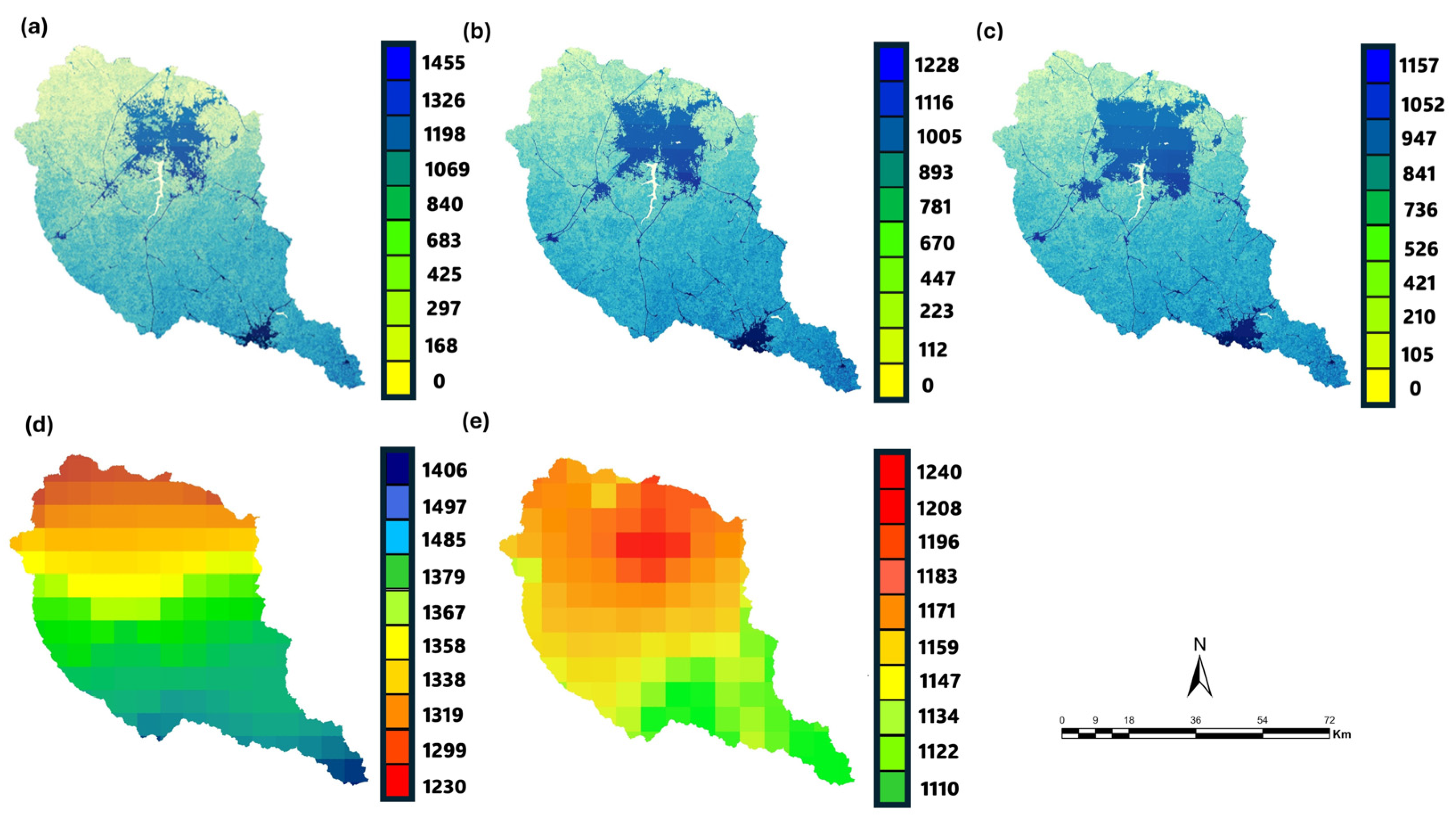

3.1. Spatial Patterns of Annual Water Yield

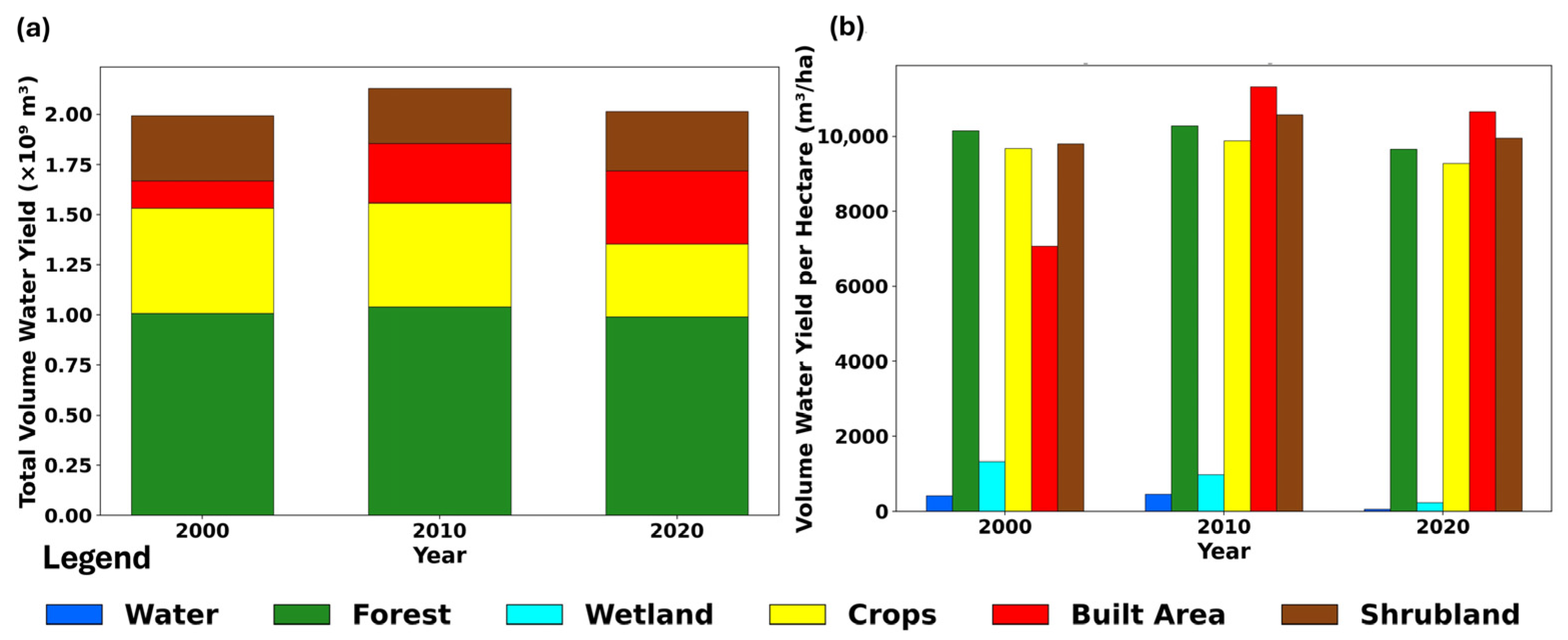

3.2. LULC Transitions and Water Yield Dynamics in the Asa Watershed

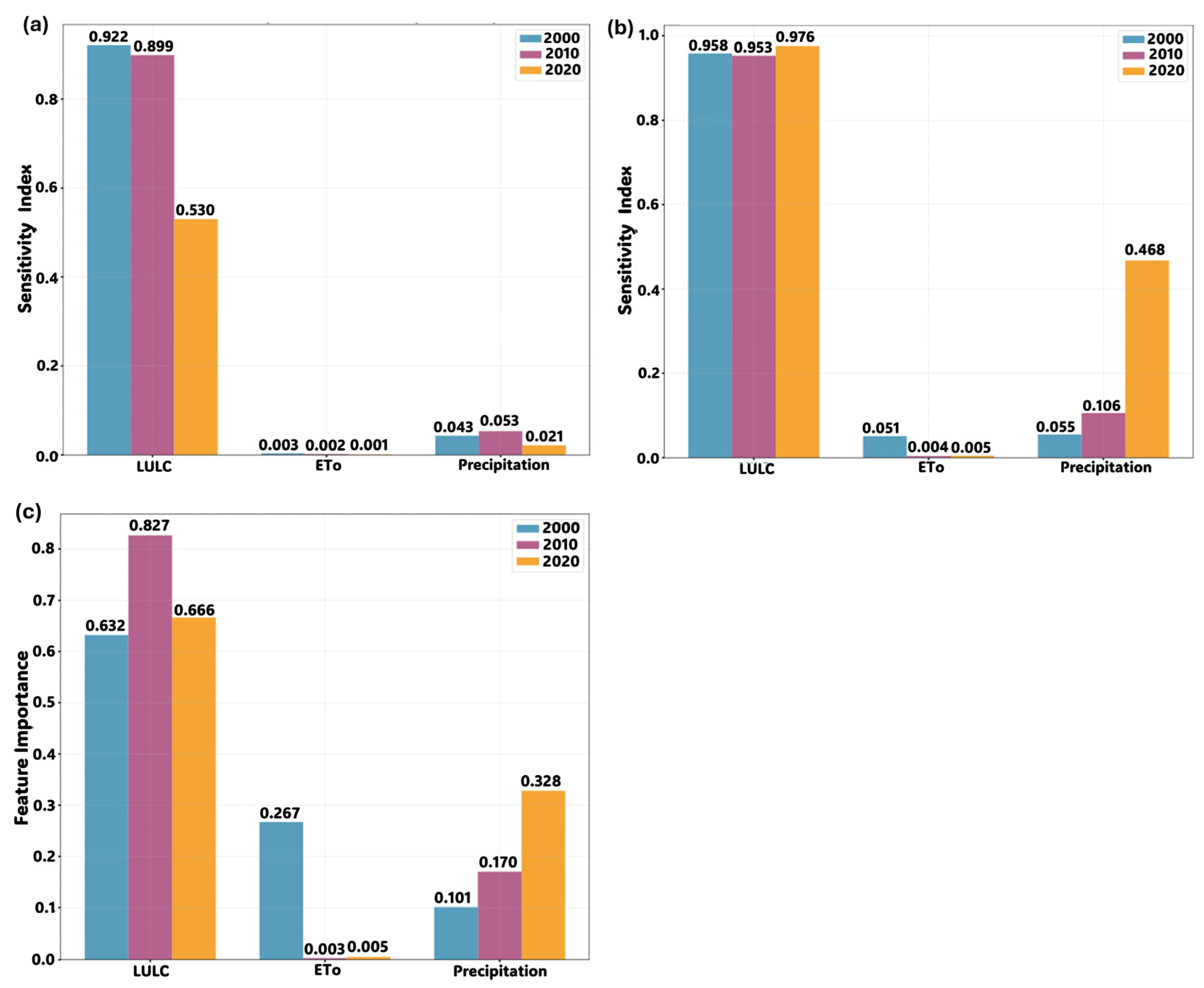

3.3. Evaluating Water Yield Sensitivity to LULC and Climate Variability

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Gradients of Water Yield

4.2. Dynamics of LULC on Water Yield

4.3. Implications of LULC and Climate Variability on Water Yield

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Policy Recommendations

- Establish cost-effective hydrological monitoring networks that integrate rainfall, streamflow, and soil moisture measurements. These networks will enable more accurate calibration and validation of ecohydrological models in data-limited settings.

- Land use planning should incorporate the identified hydrological threshold. This could involve policies to limit the conversion of natural vegetation to impervious surfaces in headwater catchments, which our analysis shows are critical for maintaining the watershed’s buffering capacity.

- Adopt uncertainty-based decision-making frameworks for water resource management. These should explicitly account for model bias and sensitivity analysis when allocating water for domestic, agricultural, and industrial sectors.

- Align regional adaptation strategies with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 6 and 13) by incorporating watershed-scale sensitivity assessments into national and subnational climate resilience policies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Gu, B. The Impacts of Human Activities on Earth Critical Zone. Earth Crit. Zone 2024, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastola, S.; Lee, S.; Shin, Y.; Jung, Y. An Assessment of Environmental Impacts on the Ecosystem Services: Study on the Bagmati Basin of Nepal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehlinger, L.; Misteli, B.; Morant, D.; Juvigny-Khenafou, N.; Cunillera-Montcusí, D.; Chaguaceda, F.; Stamenković, O.; Fahy, J.; Kolář, V.; Halabowski, D.; et al. The Ecological Role of Permanent Ponds in Europe: A Review of Dietary Linkages to Terrestrial Ecosystems via Emerging Insects. Inland Waters 2023, 13, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Ecosystems and Human Well-Being. In Biodiversity Synthesis; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Jiang, H.; Wu, W.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Gao, Y.; Duan, Y.; Ma, G.; Wu, C.; Shao, J. Mapping Global Value of Terrestrial Ecosystem Services by Countries. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 52, 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Sustainability: Four Billion People Facing Severe Water Scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigun, I.A.; Bastola, S.; Choo, I.; Jung, Y. Unraveling Climate-Induced Emissions and Food Security in Africa through Greenhouse Gas and Water Impacts across Development Levels. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Water. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2023: Partnerships and Cooperation for Water; UN Water: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-92-3-100576-3. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, B.; Cabral, P. Water Yield Modelling, Sensitivity Analysis and Validation: A Study for Portugal. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R.D.; Moore, R.D.D.; Redding, T.E.; Spittlehouse, D.L.; Carlyle-Moses, D.E.; Smerdon, B.D. Hydrologic Processes and Watershed Response. In Compendium of Forest Hydrology and Geomorphology in British Columbia; British Columbia Ministry of Forests and Range—Forest Science Program: Victoria, BC, USA, 2010; pp. 133–178. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Chen, R.; Ji, G.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Xu, J. Assessment of Future Water Yield and Water Purification Services in Data Scarce Region of Northwest China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastola, S.; Shakya, B.; Seong, Y.; Kim, B.; Jung, Y. AHP and FAHP-Based Multi-Criteria Analysis for Suitable Dam Location Analysis: A Case Study of the Bagmati Basin, Nepal. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2024, 38, 4209–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahib, I.; Ambarwulan, W.; Rahadiati, A.; Munajati, S.L.; Prihanto, Y.; Suryanta, J.; Turmudi, T.; Nuswantoro, A.C. Assessment of the Impacts of Climate and LULC Changes on the Water Yield in the Citarum River Basin, West Java Province, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayivi, F.; Jha, M.K. Estimation of Water Balance and Water Yield in the Reedy Fork-Buffalo Creek Watershed in North Carolina Using SWAT. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2018, 6, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagstad, K.J.; Ingram, J.C.; Lange, G.M.; Masozera, M.; Ancona, Z.H.; Bana, M.; Kagabo, D.; Musana, B.; Nabahungu, N.L.; Rukundo, E.; et al. Towards Ecosystem Accounts for Rwanda: Tracking 25 Years of Change in Flows and Potential Supply of Ecosystem Services. People Nat. 2020, 2, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhead, J.W.; Stratford, C.; Sharps, K.; Jones, L.; Ziv, G.; Clarke, D.; Oliver, T.H.; Bullock, J.M. Empirical Validation of the InVEST Water Yield Ecosystem Service Model at a National Scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 569, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, J.; Bagstad, K.J.; Balbi, S.; Magrach, A.; Voigt, B.; Athanasiadis, I.; Pascual, M.; Willcock, S.; Villa, F. Towards Globally Customizable Ecosystem Service Models. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, F.; Ceroni, M.; Bagstad, K.; Johnson, G.; Krivov, S. ARIES (ARtificial Intelligence for Ecosystem Services): A New Tool for Ecosystem Services Assessment, Planning, and Valuation. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual BIOECON Conference on Economic Instruments to Enhance the Conservation and Sustainable use of Biodiversity, Venice, Italy, 21–22 September 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, S.; Wang, X.; Melching, C.S.; Feger, K.H. Development and Testing of a Modified SWAT Model Based on Slope Condition and Precipitation Intensity. J. Hydrol. 2020, 588, 125098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G.; Moriasi, D.N.; Gassman, P.W.; Abbaspour, K.C.; White, M.J.; Srinivasan, R.; Santhi, C.; Harmel, R.D.; Van Griensven, A.; Van Liew, M.W.; et al. SWAT: Model Use, Calibration, and Validation. Trans. ASABE 2012, 55, 1491–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, M.K.; Hill, R.; Hallegatte, S.; Corral, P.; Brunckhorst, B.; Nguyen, M.; Freije-Rodriguez, S.; Naikal, E. Counting People Exposed to, Vulnerable to, or at High Risk From Climate Shocks: A Methodology; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford Univiersity. Natural Capital Project InVEST®: A Powerful Tool to Map and Value Ecosystem Services; Stanford Univiersity: Stanford, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Hati, J.P.; Acharyya, R.; Pal, I.; Tuladhar, N.; Habel, M. Global Trends in Using the InVEST Model Suite and Related Research: A Systematic Review. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2025, 25, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, F.; Crétaux, J.F.; Grippa, M.; Robert, E.; Trigg, M.; Tshimanga, R.M.; Kitambo, B.; Paris, A.; Carr, A.; Fleischmann, A.S.; et al. Water Resources in Africa Under Global Change: Monitoring Surface Waters from Space; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 44, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Bastola, S.; Cho, J.; Kam, J.; Jung, Y. Assessing the Influence of Climate Change on Multiple Climate Indices in Nepal Using CMIP6 Global Climate Models. Atmos. Res. 2024, 311, 107720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teferi, E.; O’Donnell, G.; Bewket, W.; Zeleke, G.; Walsh, C. Enhancing Hydrometric Monitoring in Ethiopia’s Abbay Basin: A Collaborative Framework for Data-Scarce Africa. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 60, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. World Bank Nigeria: Ensuring Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for All; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Isukuru, E.J.; Opha, J.O.; Isaiah, O.W.; Orovwighose, B.; Emmanuel, S.S. Nigeria’s Water Crisis: Abundant Water, Polluted Reality. Clean. Water 2024, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.O.; Adepoju, B.D.; Ipadeola, A.O.; Omar, D.M.; Alade, A.K.; Salami, I.B. Evaluating Urban Sprawl and Land Consumption Rate in Ilorin Metropolis Using Multitemporal Landsat Imagery. Environ. Technol. Sci. J. 2022, 12, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forests 2022; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 9789251359846. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, A.A. The Impact of Watershed Delineation on Hydrological Processes at Asa River Dam Upstream in Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria. Master’s Thesis, Kwara State University (Nigeria), Malete, Nigeria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Idrees, M.O.; Olateju, S.A.; Omar, D.M.; Babalola, A.; Ahmadu, H.A.; Kalantar, B. Spatial Assessment of Accelerated Surface Runoff and Water Accumulation Potential Areas Using AHP and Data-Driven GIS-Based Approach: The Case of Ilorin Metropolis, Nigeria. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 15877–15895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, H.; Ogunlela, A. Flood Frequency Analysis of Asa River, Ilorin, Nigeria. Int. J. Hydrol. 2024, 8, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeogun, A.G.; Ganiyu, H.O.; Adetoro, A.E.; Idowu, B.S. Effects of Watershed Delineation on the Prediction of Water Quality Parameters in Gaa Akanbi Area, Ilorin. LAUTECH J. Civ. Environ. Stud. 2022, 8, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamutaze, Y.; Kyamanywa, S.; Nabanoga, G.; Singh, B.R.; Lal, R. Climate Change Management Agriculture and Ecosystem Resilience in Sub Saharan Africa Livelihood Pathways Under Changing Climate; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 9783030129736. [Google Scholar]

- Eteh, D.R.; Japheth, B.R.; Akajiaku, C.U.; Osondu, I.; Mene-Ejegi, O.O.; Nwachukwu, E.M.; Oriasi, M.D.; Omietimi, E.J.; Ayo-Bali, A.E. Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Flood Patterns in Downstream Nigeria Using Machine Learning and Geospatial Techniques (2018–2024); Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 3, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Thiaw, I. Water Resources Modeling in Data-Scarce Watersheds: Contribution of the SWAT Model and the SUFI2 Algorithm to the Study of the Thiokoye River Basin. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2025, 13, 46–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, O.S.; Ayemu, A.I.; Adeyokunnu, A.T.; Ojo, E.O.; Afolabi, L.A. Estimation of Runoff from River Asa Watershed Using SCS Curve Number and Geographic Information System (GIS). Niger. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 6, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeogun, A.G.; Ganiyu, H.O.; Ladokun, L.L.; Ibitoye, B.A. Evaluation of Hydrokinetic Energy Potentials of Selected Rivers in Kwara State, Nigeria. Environ. Eng. Res. 2020, 25, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, O.M.; Ajayi, K.T.; Olayemi, A.B.; Okoh, A.I. Assessment of Water Quality in Asa River (Nigeria) and Its Indigenous Clarias Gariepinus Fish. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 4332–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhaleem, A.; Idowu, A.; Olujobi, A. Investigation of Ground Water Reservoir in ASA and Ilorin West Local Government of Kwara State Using Geographic Information System. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2013, Abuja, Niger, 6–10 May 2013; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, R.; Douglass, J.; Wolny, S.; Arkema, K.; Bernhardt, J.; Bierbower, W.; Chaumont, N.; Denu, D.; Fisher, D.; Glowinski, K.; et al. InVEST 3.8. 7. User’s Guide. In Natural Capital Project; Stanford University: Standford, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Hickel, K.; Dawes, W.R.; Chiew, F.H.S.; Western, A.W.; Briggs, P.R. A Rational Function Approach for Estimating Mean Annual Evapotranspiration. Water Resour. Res. 2004, 40, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budyko, M.I. Climate and Life; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Long, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, D.; Wu, H.; Li, S. Identifying the Drivers of Water Yield Ecosystem Service: A Case Study in the Yangtze River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, I.; Osborn, T.J.; Jones, P.; Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS Monthly High-Resolution Gridded Multivariate Climate Dataset. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. TerraClimate, a High-Resolution Global Dataset of Monthly Climate and Climatic Water Balance from 1958-2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 170191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.; Hansen, M.C.; Pickens, A.; Hernandez-Serna, A.; Tyukavina, A.; Turubanova, S.; Zalles, V.; Li, X.; Khan, A.; Stolle, F.; et al. The Global 2000-2020 Land Cover and Land Use Change Dataset Derived From the Landsat Archive: First Results. Front. Remote Sens. 2022, 3, 856903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T.; De Jesus, J.M.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Gonzalez, M.R.; Kilibarda, M.; Blagotić, A.; Shangguan, W.; Wright, M.N.; Geng, X.; Bauer-Marschallinger, B.; et al. SoilGrids250m: Global Gridded Soil Information Based on Machine Learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Evapotranspiration Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements (FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No.56); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998; Volume 333. [Google Scholar]

- Bojer, A.K.; Abshare, M.W.; Mesfin, F.; Al-Quraishi, A.M.F. Assessing Climate and Land Use Impacts on Surface Water Yield Using Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, e0169748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, B.; Manjunatha, B.R. Impacts of Land-Use Change on the Hydrology of Lake Tana Basin, Upper Blue Nile River Basin, Ethiopia. Glob. Chall. 2022, 6, 2200041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwed, M.; Karg, G.; Pińskwar, I.; Radziejewski, M.; Graczyk, D.; Kȩdziora, A.; Kundzewicz, Z.W. Climate Change and Its Effect on Agriculture, Water Resources and Human Health Sectors in Poland. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Fu, Y.; Hao, F.; Hu, Q. InVEST Model-Based Estimation of Water Yield in North China and Its Sensitivities to Climate Variables. Water 2020, 12, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, N.H.; Tran, V.N. Robust Uncertainty Analysis of a Process-Based Model for Runoff and Soil Erosion Simulations Using Surrogate Modeling: A Synthetic Study. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2025, 39, 2929–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svitelman, V.; Saveleva, E.; Neuvazhaev, G. Comparison of Feature Importance Measures and Variance-Based Indices for Sensitivity Analysis: Case Study of Radioactive Waste Disposal Flow and Transport Model. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2024, 39, 4827–4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Tarantola, S. On the Relative Importance of Input Factors in Mathematical Models: Safety Assessment for Nuclear Waste Disposal. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2002, 97, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Mukhopadhyay, T.; Belarbi, M.O.; Li, L. Random Forest-Based Surrogates for Transforming the Behavioral Predictions of Laminated Composite Plates and Shells from FSDT to Elasticity Solutions. Compos. Struct. 2023, 309, 116756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Wisser, D.; Barry, B.; Fowe, T.; Aduna, A. Hydrological Predictions for Small Ungauged Watersheds in the Sudanian Zone of the Volta Basin in West Africa. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2015, 4, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speth, P.; Christoph, M.; Diekkrüger, B.; Bollig, M.; Fink, B.A.H.; Goldbach, H.; Heckelei, T.; Menz, G.; Reichert, B.; RöSSLER, M. Impacts of Global Change on the Hydrological Cycle in West and Northwest Africa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 9783642129568. [Google Scholar]

- Descroix, L.; Mahé, G.; Lebel, T.; Favreau, G.; Galle, S.; Gautier, E.; Olivry, J.C.; Albergel, J.; Amogu, O.; Cappelaere, B.; et al. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Hydrological Regimes around the Boundaries between Sahelian and Sudanian Areas of West Africa: A Synthesis. J. Hydrol. 2009, 375, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togbévi, Q.F.; Sintondji, L.O. Hydrological Response to Land Use and Land Cover Changes in a Tropical West African Catchment (Couffo, Benin). AIMS Geosci. 2021, 7, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Entekhabi, D.; Castelli, F.; Chua, L. Hydrologic Response of a Tropical Watershed to Urbanization. J. Hydrol. 2014, 517, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, S.A.; Odunuga, S.; Fasona, M. Spatial Appraisal of Seasonal Water Yield of the Sokoto-Rima Basin. Sak. Univ. J. Sci. 2021, 25, 950–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achugbu, I.C.; Olufayo, A.A.; Balogun, I.A.; Dudhia, J.; McAllister, M.; Adefisan, E.A.; Naabil, E. Potential Effects of Land Use Land Cover Change on Streamflow over the Sokoto Rima River Basin. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awotwi, A.; Annor, T.; Anornu, G.K.; Quaye-Ballard, J.A.; Agyekum, J.; Ampadu, B.; Nti, I.K.; Gyampo, M.A.; Boakye, E. Climate Change Impact on Streamflow in a Tropical Basin of Ghana, West Africa. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 34, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsekpor, J.T.; Greve, K.; Yamba, E.I. Streamflow Forecasting Using Machine Learning for Flood Management and Mitigation in the White Volta Basin of Ghana. Environ. Chall. 2025, 20, 101181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, H.M.; Kura, A.L. Hydrological Response to Land Use/Land Cover Changes in Ethiopian Basins: A Review. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2024, 69, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Rong, L.; Wei, W. Impacts of Land Use/Cover Change on Water Balance by Using the SWAT Model in a Typical Loess Hilly Watershed of China. Geogr. Sustain. 2023, 4, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agumagu, O.O.; Marchant, R.; Stringer, L.C. Land Use and Land Cover Change Dynamics in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria from 1986 to 2024. Land 2025, 14, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriola, E.O.; Bamidele, I.O.; Oriola, E. Impact of Cropping Systems on Soil Properties in Derived Savanna Ecological Zone of Kwara State, Nigeria. Conflu. J. Environ. Stud. 2012, 7, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel, L.A.; Mulligan, M.; Scatena, F.N. Hydrometeorology of Tropical Montane Cloud Forests: Emerging Patterns. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 465–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measho, S.; Chen, B.; Pellikka, P.; Trisurat, Y.; Guo, L.; Sun, S.; Zhang, H. Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Associated Impacts on Water Yield Availability and Variations in the Mereb-Gash River Basin in the Horn of Africa. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2020, 125, e2020JG005632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, I.A.; Adeyewa, D.Z.; Balogun, A.A.; Morakinyo, T.E. Analysis of Urban Expansion and Land Use/ Land Cover Changes in Abeokuta, Nigeria Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System Techniques. J. Geogr. Reg. Plan. 2024, 4, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.O.; Yusuf, A.; Mokhtar, E.S.; Yao, K. Urban Flood Susceptibility Mapping in Ilorin, Nigeria, Using GIS and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 5779–5791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solihu, H.; Bilewu, S.O. Assessment of Anthropogenic Activities Impacts on the Water Quality of Asa River: A Case Study of Amilengbe Area, Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria. Environ. Chall. 2022, 7, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, E.; Wendling, V.; Panthou, G.; Dubas, O.; Vandervaere, J.-P.; Hector, B.; Favreau, G.; Cohard, J.-M.; Pierre, C.; Descroix, L.; et al. Hydrological Regime Shifts in Sahelian Watersheds: An Investigation with a Simple Dynamical Model Driven by Annual Precipitation. EGUsphere 2025, 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewole, A.O.; Eludoyin, A.O.; Chirima, G.J.; Newete, S.W. Field-Scale Variability and Dynamics of Soil Moisture in Southwestern Nigeria. Discov. Soil 2024, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input | Source | Resolution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | Pre | CRU TS 4.06 | 55 km |

| Reference Evapotranspiration | ETo | TerraClimate | 4 km |

| Root Depth, Plant available water content | RDp, PAWC | ISRIC | 250 m |

| Land use/Land cover | LULC | GLAD Land Cover | 30 m |

| Watershed Boundary | SRTM DEM (USGS) | 30 m | |

| Streamflow Data | Nigeria Hydrological Services Agency (NIHSA) | 20 years (2001–2020) | |

| Crop Coefficients | Kc | FAO Crop Water Requirements Guidelines | Class-dependent |

| S/N | Climate Data Period | LULC Reference Year | Denotation | Mean Rainfall (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1991–2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 1373 |

| 2 | 2001–2010 | 2010 | 2010 | 1331 |

| 3 | 2011–2020 | 2020 | 2020 | 1266 |

| LULC_desc | Lucode | LULC_veg | Kc | Root_Depth (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 1 | 0 | 1.05 | 1 |

| Forest | 2 | 1 | 0.80 | 1500 |

| Wetland | 4 | 0 | 1.00 | 1200 |

| Crops | 5 | 1 | 0.95 | 800 |

| Built Area | 7 | 0 | 0.15 | 300 |

| Shrubland | 11 | 1 | 0.70 | 1000 |

| Year | Simulated AWY (Million m3) | Observed Streamflow (Million m3) |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 1990 | 3214 |

| 2010 | 2130 | 3482 |

| 2020 | 2020 | 3499 |

| LULC/Year | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | WY/Pixel (mm) | Area (ha) | WY/Pixel (mm) | Area (ha) | WY/Pixel (mm) | |

| Water | 791.92 | 41.72 | 919.89 | 46.40 | 885.12 | 7.02 |

| Forest | 99,195.50 | 1014.78 | 101,190.84 | 1027.87 | 102,707.31 | 965.00 |

| Wetland | 218.65 | 133.6 | 96.04 | 98.12 | 105.15 | 22.90 |

| Crops | 54,237.84 | 967.29 | 52,449.75 | 988.04 | 38,971.75 | 928.62 |

| Built Area | 19,370.63 | 707.28 | 26,130.81 | 1132.57 | 34,284.76 | 1066.15 |

| Shrubland | 33,044.42 | 980.48 | 26,046.85 | 1057.8 | 29,880.11 | 995.93 |

| Year | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 0.976 | 17.3 | 4.5 |

| 2010 | 0.985 | 11.1 | 8.5 |

| 2020 | 0.965 | 11.3 | 8.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adigun, I.A.; Bastola, S.; Kim, B.; Kim, C.Y.; Jung, Y. Hydrological Sensitivity to Land-Use and Climate Change in the Asa Watershed, Nigeria. Water 2025, 17, 3477. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243477

Adigun IA, Bastola S, Kim B, Kim CY, Jung Y. Hydrological Sensitivity to Land-Use and Climate Change in the Asa Watershed, Nigeria. Water. 2025; 17(24):3477. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243477

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdigun, Ismail Adebayo, Shiksha Bastola, Beomgu Kim, Chi Young Kim, and Younghun Jung. 2025. "Hydrological Sensitivity to Land-Use and Climate Change in the Asa Watershed, Nigeria" Water 17, no. 24: 3477. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243477

APA StyleAdigun, I. A., Bastola, S., Kim, B., Kim, C. Y., & Jung, Y. (2025). Hydrological Sensitivity to Land-Use and Climate Change in the Asa Watershed, Nigeria. Water, 17(24), 3477. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243477