Characterization of a Multi-Diffuser Fine-Bubble Aeration Reactor: Influence of Local Parameters and Hydrodynamics on Oxygen Transfer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Experimental Methodology

2.2.1. Oxygen Transfer

2.2.2. Acoustic Doppler Velocimetry (ADV)

2.2.3. Dual-Tip Conductivity Probe

3. Results and Discussion

- Zone 1 corresponds to the region immediately above each diffuser, where the plume rises freely until, at a given height, it meets its neighbors and thus enters Zone 3. Close to the diffuser, the plume’s behavior resembles that of an isolated plume, but as it ascends, it entrains fluid from Zone 2. This entrainment adds complexity to the flow and causes the plume to diverge from isolated-plume behavior before it reaches Zone 3.

- Zone 2 encompasses the region between diffusers and is characterized by highly complex, oscillatory flow. The upward liquid comes from the lower region of the diffusers and from the tank walls and is entrained into the plume by the motion of the rising bubbles. However, the lateral oscillations of neighboring plumes disrupt this entrainment, rendering the flow chaotic and inducing partial downward recirculation. Time-averaged velocity measurements in many parts of Zone 2 approach zero, reflecting the alternation of upward and downward motions. The close spacing of the diffusers, combined with plume oscillations, imposes a highly turbulent, unsteady flow structure that defies the definition of steady or mean conditions. In the current setup with a high number of diffusers and high diffuser density, recirculation occurs primarily along the walls, and there is little recirculation between the diffusers. However, as the distance between diffusers increases, these recirculation zones become more significant in the downward flows.

- Zone 3 is formed when the plumes have merged and become indistinguishable from one another, creating a homogeneous void fraction region. The liquid rise velocity in this zone decreases due to the increased cross-sectional area of ascent and the reduced number of areas available for downward flow, which hinders recirculation. The behavior in Zone 3 is characterized by a more stable and homogenized state, where recirculation occurs primarily at the peripheries, especially along the walls and corners of the reactor. This transition marks a shift from the chaotic, oscillatory flow seen in Zone 2 to a more steady, uniform flow pattern.

- Zone 4 is the region where liquid descends in areas near the walls. The plumes move away from the walls due to these currents. Some of the ascending bubbles get trapped in this downward flow, causing the floating bubbles observed on the walls. This recirculating flow travels through the area beneath the diffusers and ascends to enter the plume (entrainment).

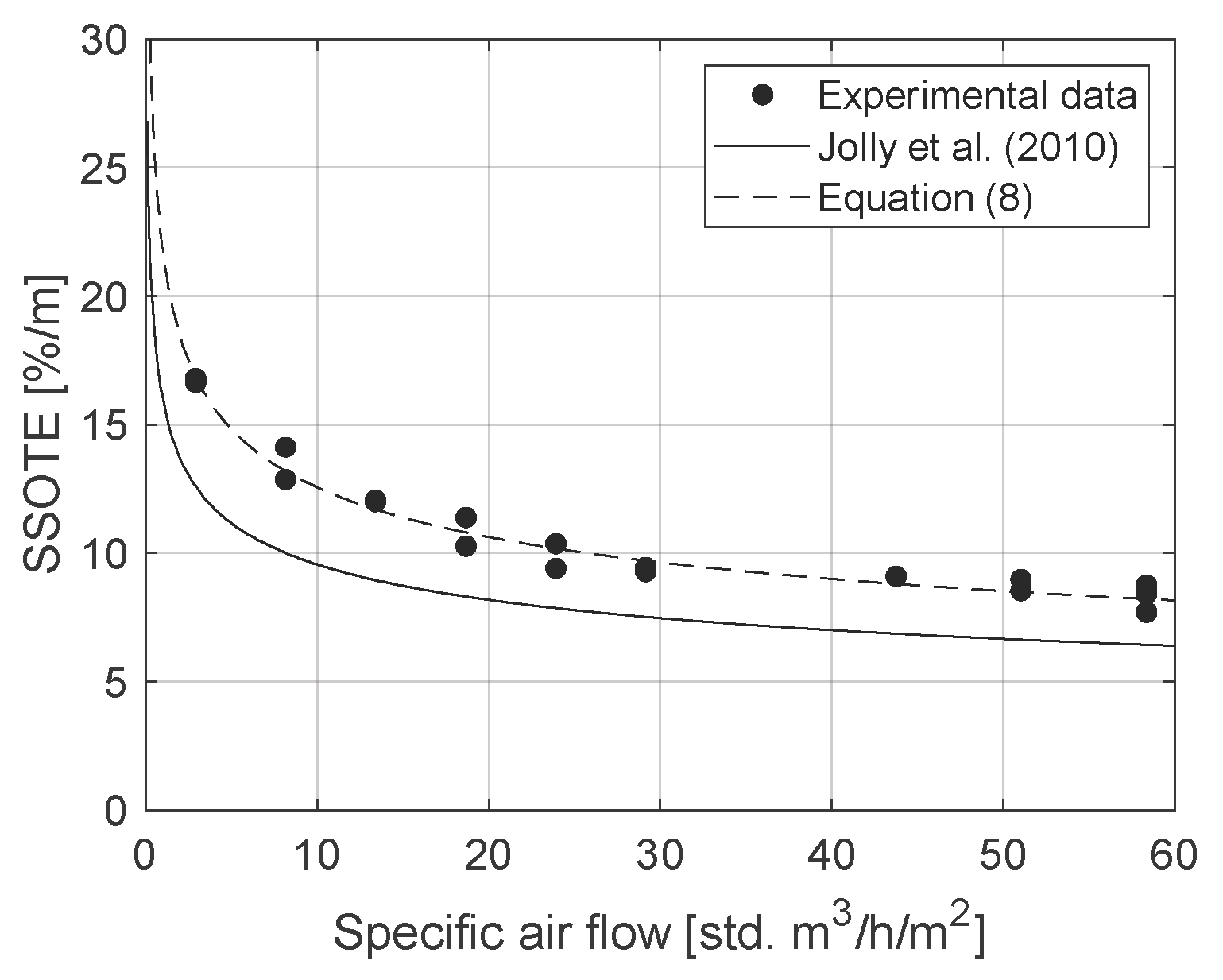

3.1. Oxygen Transfer Results

3.2. Hydrodynamics

3.3. Local Flow Parameters and Their Effect on Mass Transfer

3.3.1. Bubble Interfacial Velocity

3.3.2. Bubble Chord Length

3.3.3. Interfacial Area

- 1.

- Radial integration of the CP’s IAC profiles (RI-CP). The reactor’s average interfacial area () is obtained from the profiles measured with the CP. The integral in Equation (10) is evaluated up to the midpoint between the diffusers ( m). By computing this integral at each height, a mean interfacial area, , is obtained for each vertical position, representing the average interfacial area at that height. Finally, a correction is applied to account for the volume below the diffusers, where the local IAC is zero, yielding the reactor’s average interfacial area (

- 2.

- Using the bubble size and the bubble velocity obtained with CP (Vel-CP). This method assumes that at a given height, all bubbles rise at the same velocity and are the same size, which is consistent with the results obtained in Figure 14 and Figure 16. The values used for this calculation are taken from Figure 15 and Figure 17a. The calculation is based on Equation (11), where is the number of bubbles, is the area of a bubble, and is the volume of the reactor. The IAC is determined as a function of the flow rate (), bubble velocity (), reactor area (), and bubble diameter (), under these assumptions. The bubble diameter used in this calculation is assumed to be the chord length.

- 3.

- Using the bubble size and the void fraction obtained from the variation of the interface height in the reactor. This method (Void-Level) uses Equation (12) [60], which is a variation of the previous expression and has been employed in many earlier studies. In this equation, represents the mean void fraction in the reactor, and is the mean bubble diameter:This method for calculating has been previously tested [61]. In this approach, the void fraction is determined by measuring the increase in the liquid column height, as described by Herrman-Heber et al. [62]. To determine the gas void fraction, Equation (13) is used, which accounts for the relationship between the liquid level without gas injection () and with gas injection (), with the interface height measured using a camera.To verify the consistency of the data trend, the void fraction was fitted using a common correlation between gas flow rate and gas void fraction [63]. The resulting fit, , where is the flow rate (m3/h) and is the void fraction (%), showed excellent agreement with the experimental data, yielding .

3.4. Validation of Dual-Tip Conductivity Probes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wagner, M.R.; Pöpel, H.J. Oxygen Transfer and Aeration Efficiency—Influence of Diffuser Submergence, Diffuser Density and Blower Type. Water Sci. Technol. 1998, 38, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Lian, J. Challenges of Precise Aeration Implementation in Conventional Wastewater Treatment Processes: A Review. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 78, 108737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, J.; Remiszewska-Skwarek, A.; Duda, S.; Łagód, G. Aeration Process in Bioreactors as the Main Energy Consumer in a Wastewater Treatment Plant. Review of Solutions and Methods of Process Optimization. Processes 2019, 7, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besagni, G.; Inzoli, F.; Ziegenhein, T. Two-Phase Bubble Columns: A Comprehensive Review. ChemEngineering 2018, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, B.R.; Taylor, G.; Turner, J.S.; Tirner, J.S. Turbulent Gravitational Convection from Maintained and Instantaneous Sources. Math. Phys. Sci. 1956, 234, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cederwall, K.; Ditmars, J.D. Analysis of Air-Bubble Plumes. Coast. Eng. 1974, 14, 2209–2226. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, J.H. Mean Flow in Round Bubble Plumes. J. Fluid Mech. 1983, 133, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socolofsky, S.A.; Crounse, B.C.; Adams, E. Multi-Phase Plumes in Uniform, Stratified, and Flowing Environments. In Environmental Fluid Mechanics: Theories and Applications; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2002; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wüest, A.; Brooks, N.H.; Keck, W.M.; Imboden, D.M. Bubble Plume Modeling for Lake Restoration. Water Resour. Res. 1992, 28, 3235–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Civil Engineers. Measurement of Oxygen Transfer in Clean Water; The Society: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 087262885X. [Google Scholar]

- Demoyer, C.D.; Schierholz, E.L.; Gulliver, J.S.; Wilhelms, S.C. Impact of Bubble and Free Surface Oxygen Transfer on Diffused Aeration Systems. Water Res. 2003, 37, 1890–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolly, M.; Green, S.; Wallis-Lage, C.; Buchanan, A. Energy Saving in Activated Sludge Plants by the Use of More Efficient Fine Bubble Diffusers. Water Environ. J. 2010, 24, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzardi, I.; Bottino, A.; Capannelli, G.; Pagliero, M.; Costa, C.; Matteucci, D.; Comite, A. Membrane Bubble Aeration Unit: Experimental Study of the Performance in Lab Scale and Full-Scale Systems. J. Memb. Sci. 2023, 685, 121927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F.C.; Marouchos, A.; Bilton, A.M. Experimental Characterization of an Oxygen Transfer Model of a Fine Pore Diffuser Aerator. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 98, 102259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnisch, J.; Schwarz, M.; Wagner, M. Three Decades of Oxygen Transfer Tests in Clean Water in a Pilot Scale Test Tank with Fine-Bubble Diffusers and the Resulting Conclusions for Wwtp Operation. Water Pract. Technol. 2020, 15, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.L. Design Concepts for Activated Sludge Diffused Aeration Systems; University of Kansas: Lawrence, Kansas, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schraa, O.; Rieger, L.; Alex, J. Development of a Model for Activated Sludge Aeration Systems: Linking Air Supply, Distribution, and Demand. Water Sci. Technol. 2017, 75, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillot, S.; Capela-Marsal, S.; Roustan, M.; Héduit, A. Predicting Oxygen Transfer of Fine Bubble Diffused Aeration Systems—Model Issued from Dimensional Analysis. Water Res. 2005, 39, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMoyer, C.D.; Gulliver, J.S.; Wilhelms, S.C. Comparison of Submerged Aerator Effectiveness. Lake Reserv. Manag. 2001, 17, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.; Bellandi, G.; Rehman, U.; Neves, R.; Amerlinck, Y.; Nopens, I. Towards Improved Accuracy in Modeling Aeration Efficiency through Understanding Bubble Size Distribution Dynamics. Water Res. 2018, 131, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanen, A.; Orivuori, P.; Aittamaa, J. Measurements of Local Bubble Size Distributions from Various Flexible Membrane Diffusers. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2006, 45, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popel, H.; Wagner, M. Prediction of Oxygen Transfer Rates from Simple Measurements of Bubble Characteristics. Water Sci. Technol. 1991, 23, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lai, C.C.K.; Socolofsky, S.A. Mean Velocity, Spreading and Entrainment Characteristics of Weak Bubble Plumes in Unstratified and Stationary Water. J. Fluid. Mech. 2019, 874, 102–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, D.G.; Bhaumik, T.; Bergmann, C.; Socolofsky, S.A. Particle Image Velocimetry Measurements of the Mean Flow Characteristics in a Bubble Plume. J. Eng. Mech. 2007, 133, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupsien, D.; Cockx, A.; Liné, A. The Organized Flow Structure of an Oscillating Bubble Plume. AIChE J. 2021, 67, e17334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelen, S.; van Rijsbergen, M.; Birvalski, M.; Bloemhof, F.; Krug, D. In Situ Measurements of Void Fractions and Bubble Size Distributions in Bubble Curtains. Exp. Fluids 2023, 64, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, A.P.S.; Miranda, D.D.E.; Luz, L.M.S.; França, G.F.M. Bubble Plumes and the Coanda Effect. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 2002, 28, 1293–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Xingxing, Y.; Wen, C.; Jiehui, R.; Min, W.; Ting, M.; Lei, L.; Ran, F.; Kun, Y. Effect of Aerated Pore Distribution on Bubble Plume Movement in a Cylindrical Aerated Tank. Rev. Chim. 2020, 71, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, B.; Wu, H.; DiMarco, S.F. Impact of Bubble Size on the Integral Characteristics of Bubble Plumes in Quiescent and Unstratified Water. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2020, 125, 103230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensen, J.; Roig, V. Experimental Study of the Unsteady Structure of a Confined Bubble Plume. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 2001, 27, 1431–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelen, S.; Krug, D. Planar Bubble Plumes from an Array of Nozzles: Measurements and Modelling. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 2024, 174, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockx, A.; Roustan, M.; Line, A.; Hebrard, G. Modelling of Mass Transfer Coefficient KL in Bubble Columns. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1995, 73, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, V.C.; Lafuente, J.; Baeza, J.A. Activated Sludge Model 2d Calibration with Full-Scale WWTP Data: Comparing Model Parameter Identifiability with Influent and Operational Uncertainty. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 37, 1271–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.; Lohrmann, A. Open Water Test of the SonTek Acoustic Doppler Velocimeter. In Proceedings of the IEEE Fifth Working Conference on Current Measurement, St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 7–9 February 1995; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 188–192. [Google Scholar]

- Nikora, V.I.; Goring, D.G. ADV Measurements of Turbulence: Can We Improve Their Interpretation? J. Hydraul. Eng. 1998, 124, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birjandi, A.H.; Bibeau, E.L. Improvement of Acoustic Doppler Velocimetry in Bubbly Flow Measurements as Applied to River Characterization for Kinetic Turbines. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 2011, 37, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goring, D.G.; Nikora, V.I. Despiking Acoustic Doppler Velocimeter Data. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2002, 128, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, I.; Ishii, M.; Serizawa, A. Local Formulation and Measurements of Interfacial Area Concentration in Two-Phase Flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 1986, 12, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, I.; Serizawa, A. Interfacial Area Concentration in Bubbly Flow. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1990, 120, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revankar, S.T.; Ishii, M. Theory and Measurement of Local Interfacial Area Using a Four Sensor Probe in Two-Phase Flow. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1993, 36, 2997–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkach-Navarro, S.; Lahey, R.T.; Drew, D.A.; Meyder, R. Interfacial Area Density, Mean Radius and Number Measurements in Bubbly Two-Phase Flow. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1993, 142, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartellier, A. Post-Treatment for Phase Detection Probes in Non Uniform Two-Phase Flows. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 1999, 25, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.G.; Franc, F.A.; Rosa, E.S. Statistical Method to Calculate Local Interfacial Variables in Two-Phase Bubbly Flows Using Intrusive Crossing Probes. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 2000, 26, 1797–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X. Interfacial Area Measurement and Transport Modeling in Air-Water Two-Phase Flow. Ph.D. Thesis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Fu, X.Y.; Wang, X.; Ishii, M. Study on Interfacial Structures in Slug Flows Using a Miniaturized Four-Sensor Conductivity Probe. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2001, 204, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euh, D.J.; Yun, B.J.; Song, C.H.; Kwon, T.S.; Chung, M.K.; Lee, U.C. Development of the Five-Sensor Conductivity Probe Method for the Measurement of the Interfacial Area Concentration. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2001, 205, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Saito, Y.; Mishima, K.; Nakamura, H. Methodological Improvement of an Intrusive Four-Sensor Probe for the Multi-Dimensional Two-Phase Flow Measurement. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 2005, 31, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.R.; Mishra, R.; Ubbi, K.; Asim, T. Optimal Design of a Four-Sensor Probe System to Measure the Flow Properties of the Dispersed Phase in Bubbly Air-Water Multiphase Flows. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2013, 201, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monrós-Andreu, G. Intrusive Sensors for Two-Phase Flow Measurements. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Jaume I, Castelló, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliara, S.; Felder, S.; Boes, R.M.; Hohermuth, B. Intrusive Effects of Dual-Tip Conductivity Probes on Bubble Measurements in a Wide Velocity Range. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2023, 170, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Fu, X.Y.; Wang, X.; Ishii, M. Development of the Miniaturized Four-Sensor Conductivity Probe and the Signal Processing Scheme. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2000, 43, 4101–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monrós-Andreu, G.; Martinez-Cuenca, R.; Torró, S.; Escrig, J.; Hewakandamby, B.; Chiva, S. Multi-Needle Capacitance Probe for Non-Conductive Two-Phase Flows. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2016, 27, 074004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombardelli, F.A.; Buscaglia, G.C.; Rehmann, C.R.; Rincón, L.E.; García, M.H. Modeling and Scaling of Aeration Bubble Plumes: A Two-Phase Flow Analysis. J. Hydraul. Res. 2007, 45, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Neto, I.E.; Parente, P.A.B. Influence of Mass Transfer on Bubble Plume Hydrodynamics. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2016, 88, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H.B.; List, E.J.; Koh, R.C.Y.; Imberger, J.; Brooks, N.H. Mixing in Inland and Coastal Waters; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0-08-051177-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gresch, M.; Armbruster, M.; Braun, D.; Gujer, W. Effects of Aeration Patterns on the Flow Field in Wastewater Aeration Tanks. Water Res. 2011, 45, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, G.S.; Gent, S.P.; Suess, T.N.; Anderson, G.A. Hydrodynamic and Heat Transfer Effects of Different Sparger Spacings Within a Column Photobioreactor Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. In ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Takagi, S.; Matsumoto, Y. The Effect of Bubble-Induced Liquid Flow on Mass Transfer in Bubble Plumes. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 2009, 35, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, E.; Herrmann-Heber, R.; Reinecke, S.F.; Hampel, U. Bubble Generation by Micro-Orifices with Application on Activated Sludge Wastewater Treatment. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2019, 143, 107511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van’t Riet, K.; Tramper, J. Basic Bioreactor Design, 1st ed.; CRC Press: New York, MY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Díaz, D.; Navaza, J.M.; Sanjurjo, B. Interfacial Area Evaluation in a Bubble Column in the Presence of a Surface-Active Substance. Comparison of Methods. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 144, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Heber, R.; Oleshova, M.; Reinecke, S.F.; Meier, M.; Taş, S.; Hampel, U.; Lerch, A. Population Balance Modeling-Assisted Prediction of Oxygen Mass Transfer Coefficients with Optical Measurements. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 64, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.T.; Kelkar, B.G.; Godbole, S.P.; Deckwer, W.-D. Design Parameters Column Reactors Estimations for Bubble olumn Reactors. AIChE J. 1982, 28, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higbie, R. The Rate of Absorption of a Pure Gas into a Still Liquid during Short Periods of Exposure. Trans. AIChE 1935, 31, 365–389. [Google Scholar]

- Frössling, N. The Evaporation of Falling Drops. Gerlands Beitr. Geophys. 1938, 52, 170–216. [Google Scholar]

- Clift, R.; Grace, J.R.; Weber, M.E. Bubbles, Drops, and Particles; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; ISBN 012176950X. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, H. Particle/Fluid Transport Processes. Prog. Chem. Eng. 1979, 17, 61–99. [Google Scholar]

) and the plume half-width (

) and the plume half-width ( ) for (a) 10 m3/h, (b) 20 m3/h, and (c) 40 m3/h.

) for (a) 10 m3/h, (b) 20 m3/h, and (c) 40 m3/h.

) and the plume half-width (

) and the plume half-width ( ) for (a) 10 m3/h, (b) 20 m3/h, and (c) 40 m3/h.

) for (a) 10 m3/h, (b) 20 m3/h, and (c) 40 m3/h.

| Code | Name | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| F-01 | Air source | = 8 bar |

| F-02 | = 200 bar | |

| FC-01 & FV-01 | Flow meter controller (Bronkhorst EL-FLOW F-203AV) | Accuracy ±0.5% RD plus ±0.1% FS |

| PG-01 | Pressure sensor | Range Accuracy |

| SOV-0X | Solenoid valve (SMC EVT317) | = 9 bar |

| TG-01 | Temperature sensor (NTC) | Range Accuracy |

| F-02 | REACT-UJI Reactor | Capacity |

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Pit dimensions | 1.3 × 1.3 | m2 |

| Water depth | 1.2 | m |

| Diffuser depth | 1.15 | m |

| Diffuser diameter | 0.23 | m |

| Released gas | Atmospheric air | — |

| Water density (20 °C) | 998 | Kg m−3 |

| Water temperature | 15–20 | °C |

| Water conductivity | 1040 | S/cm |

| Total gas flow rates | {10, 20, 40} | Nm3/h |

| Flow Rates | R2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 10 m3/h | 0.05 | 0.892 |

| 20 m3/h | 0.15 | 0.991 |

| 40 m3/h | 0.18 | 0.971 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prades-Mateu, O.; Monrós-Andreu, G.; Trifi, D.; Luis-Gómez, J.; Torró, S.; Martínez-Cuenca, R.; Chiva, S. Characterization of a Multi-Diffuser Fine-Bubble Aeration Reactor: Influence of Local Parameters and Hydrodynamics on Oxygen Transfer. Water 2025, 17, 3448. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243448

Prades-Mateu O, Monrós-Andreu G, Trifi D, Luis-Gómez J, Torró S, Martínez-Cuenca R, Chiva S. Characterization of a Multi-Diffuser Fine-Bubble Aeration Reactor: Influence of Local Parameters and Hydrodynamics on Oxygen Transfer. Water. 2025; 17(24):3448. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243448

Chicago/Turabian StylePrades-Mateu, Oscar, Guillem Monrós-Andreu, Delia Trifi, Jaume Luis-Gómez, Salvador Torró, Raúl Martínez-Cuenca, and Sergio Chiva. 2025. "Characterization of a Multi-Diffuser Fine-Bubble Aeration Reactor: Influence of Local Parameters and Hydrodynamics on Oxygen Transfer" Water 17, no. 24: 3448. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243448

APA StylePrades-Mateu, O., Monrós-Andreu, G., Trifi, D., Luis-Gómez, J., Torró, S., Martínez-Cuenca, R., & Chiva, S. (2025). Characterization of a Multi-Diffuser Fine-Bubble Aeration Reactor: Influence of Local Parameters and Hydrodynamics on Oxygen Transfer. Water, 17(24), 3448. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243448