Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Industrial Structure in the Yellow River Basin, China, and Its Impact on the Water Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

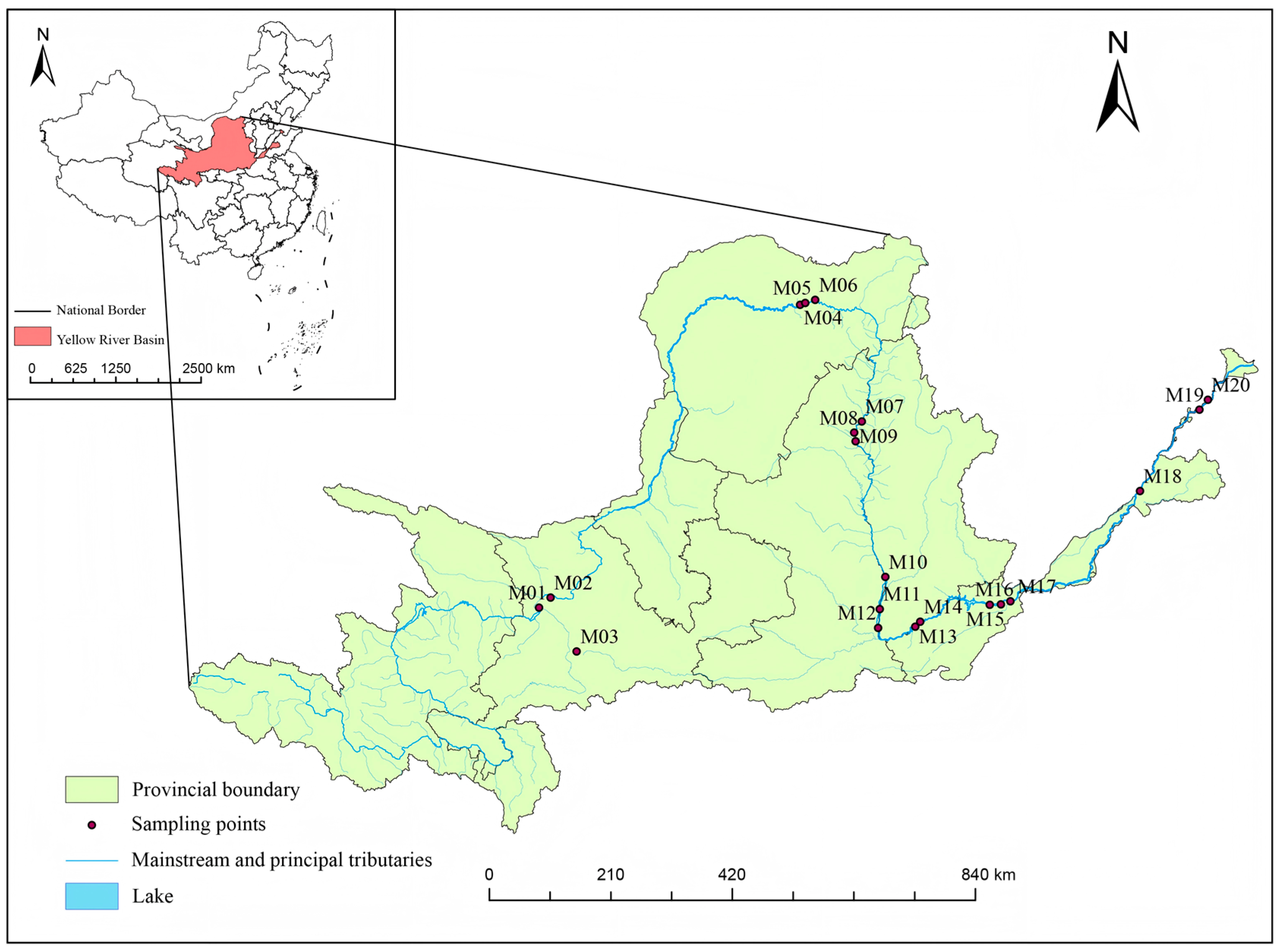

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Sources

2.2. Sample Collection and Analytical Testing

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Analysis of Results

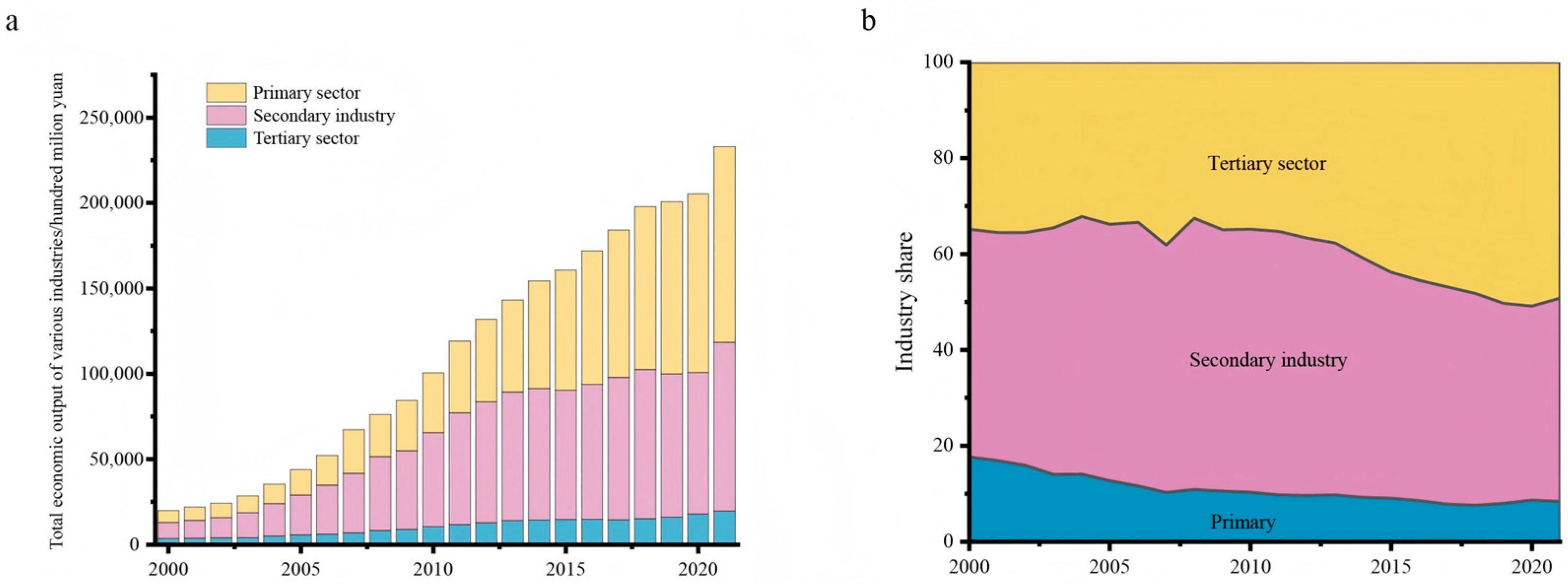

3.1. Characteristics of Industrial Structure Transformation in the Yellow River Basin

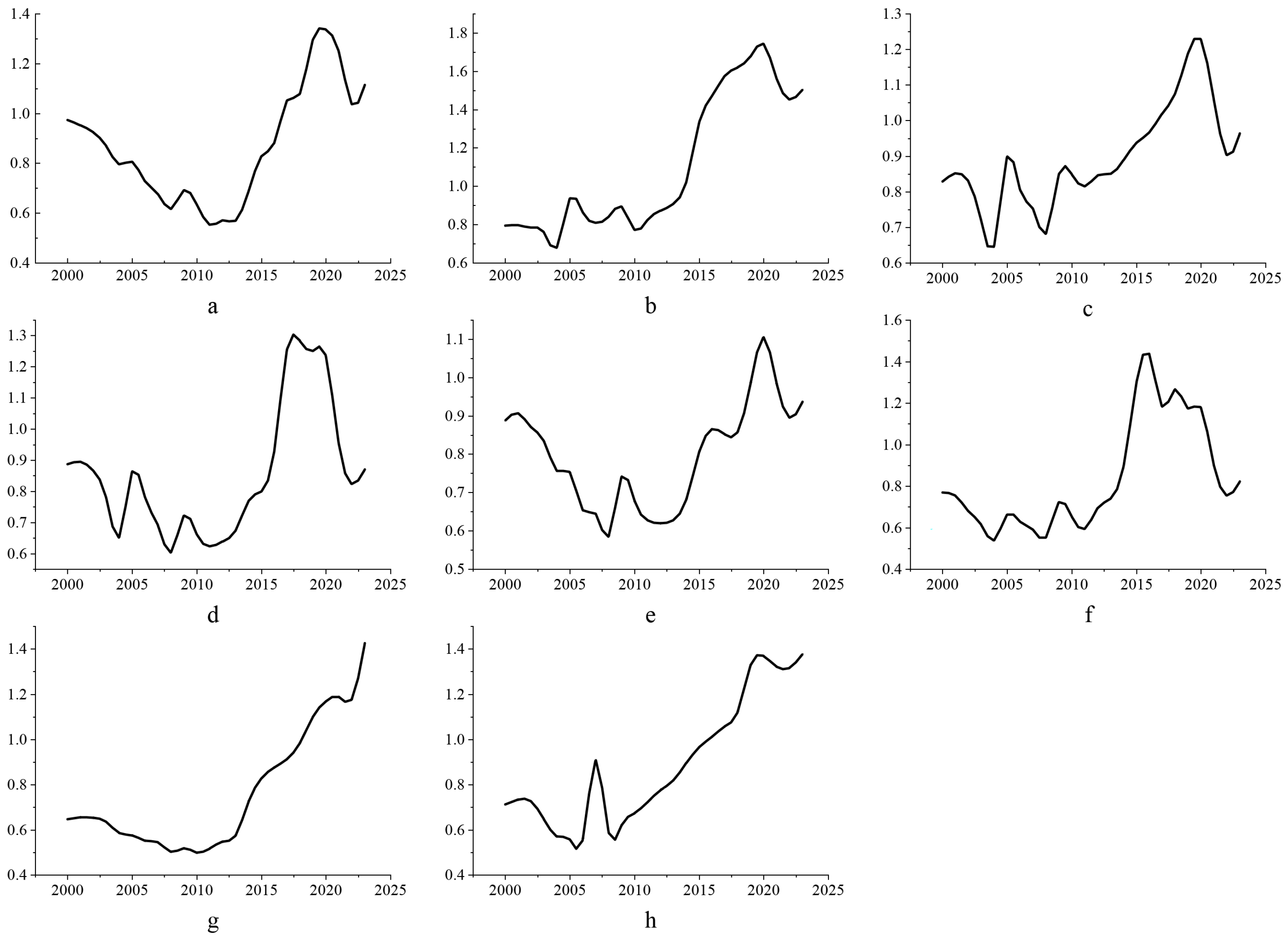

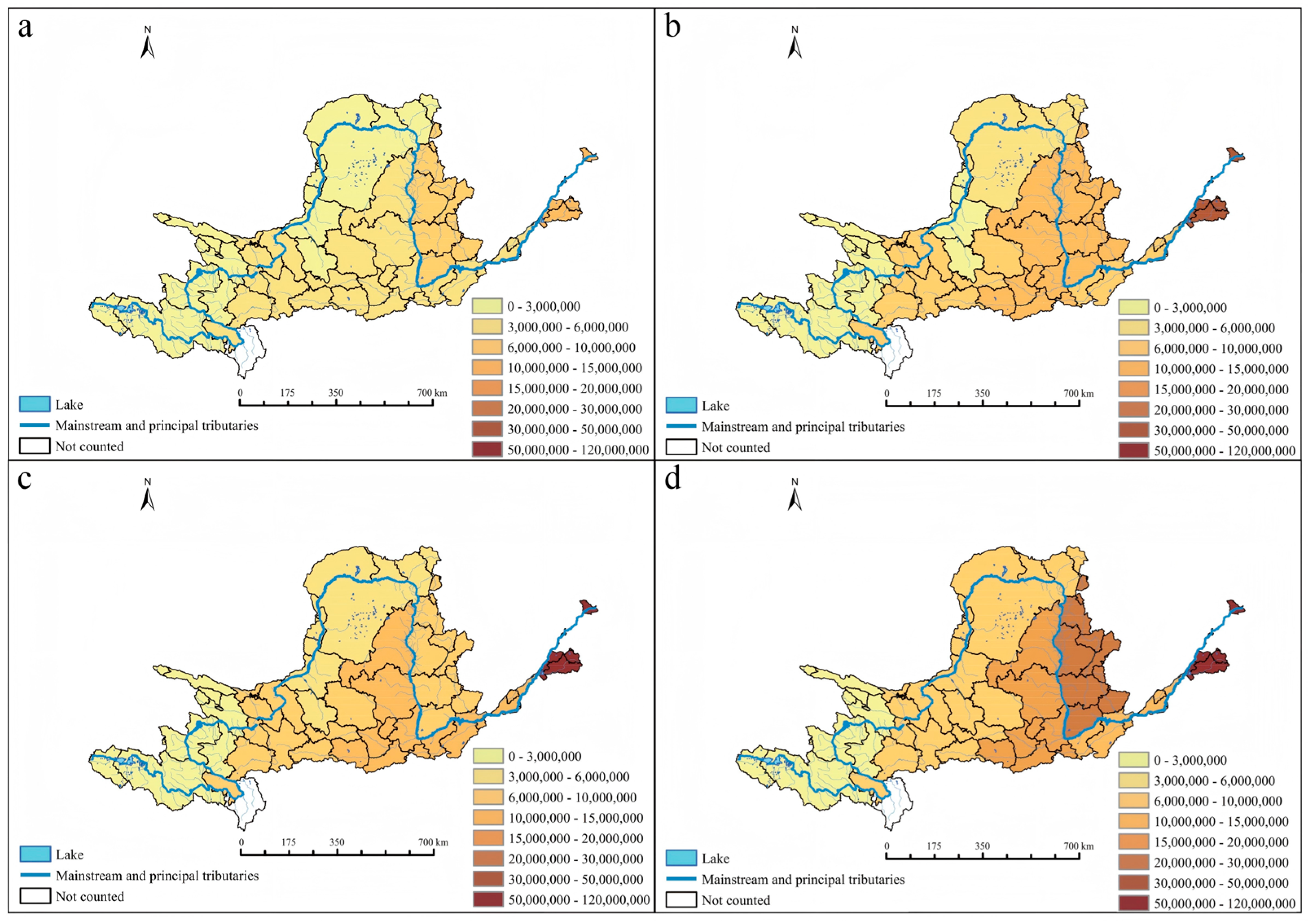

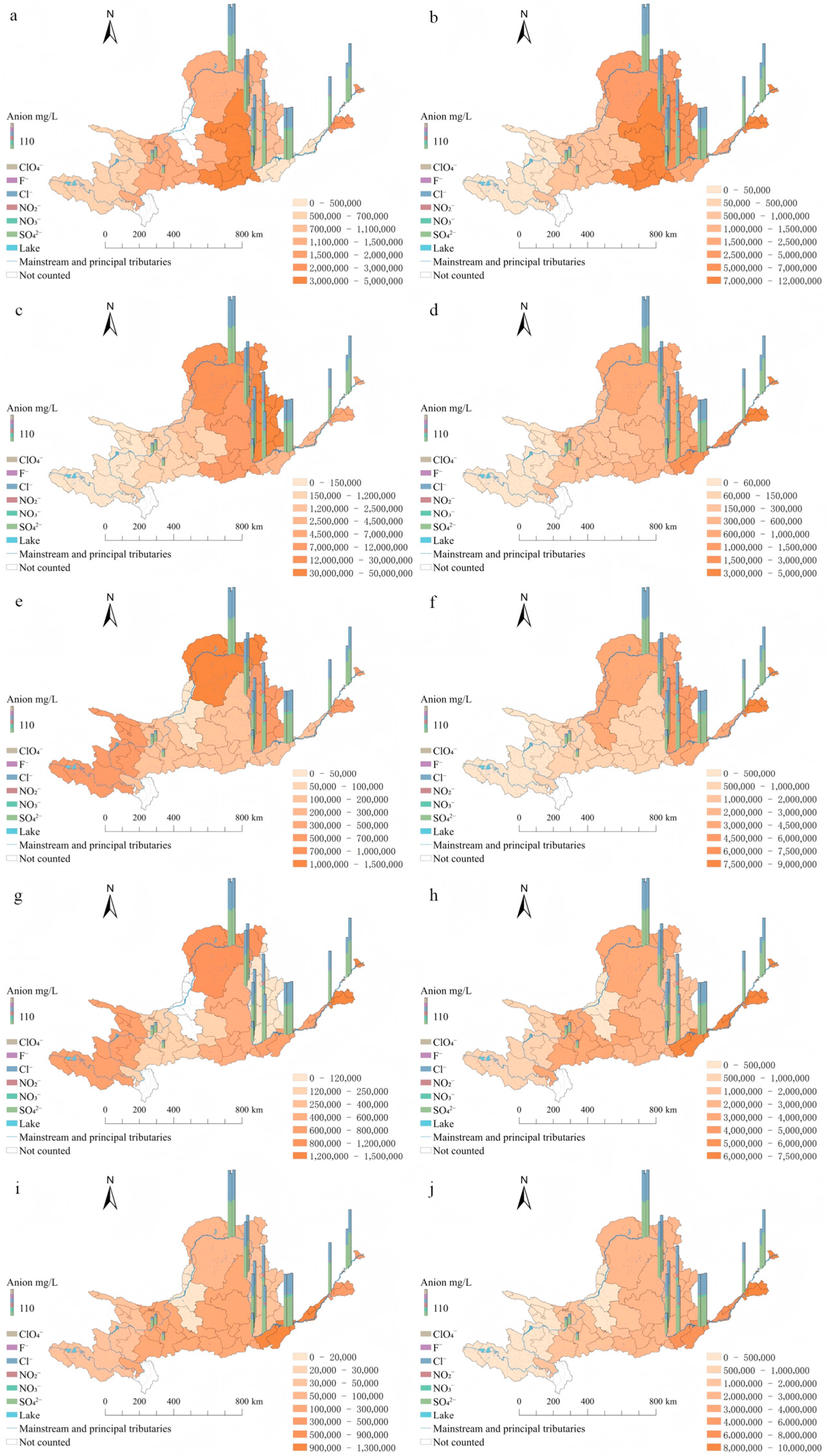

3.2. Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Typical Industries in the Yellow River Basin

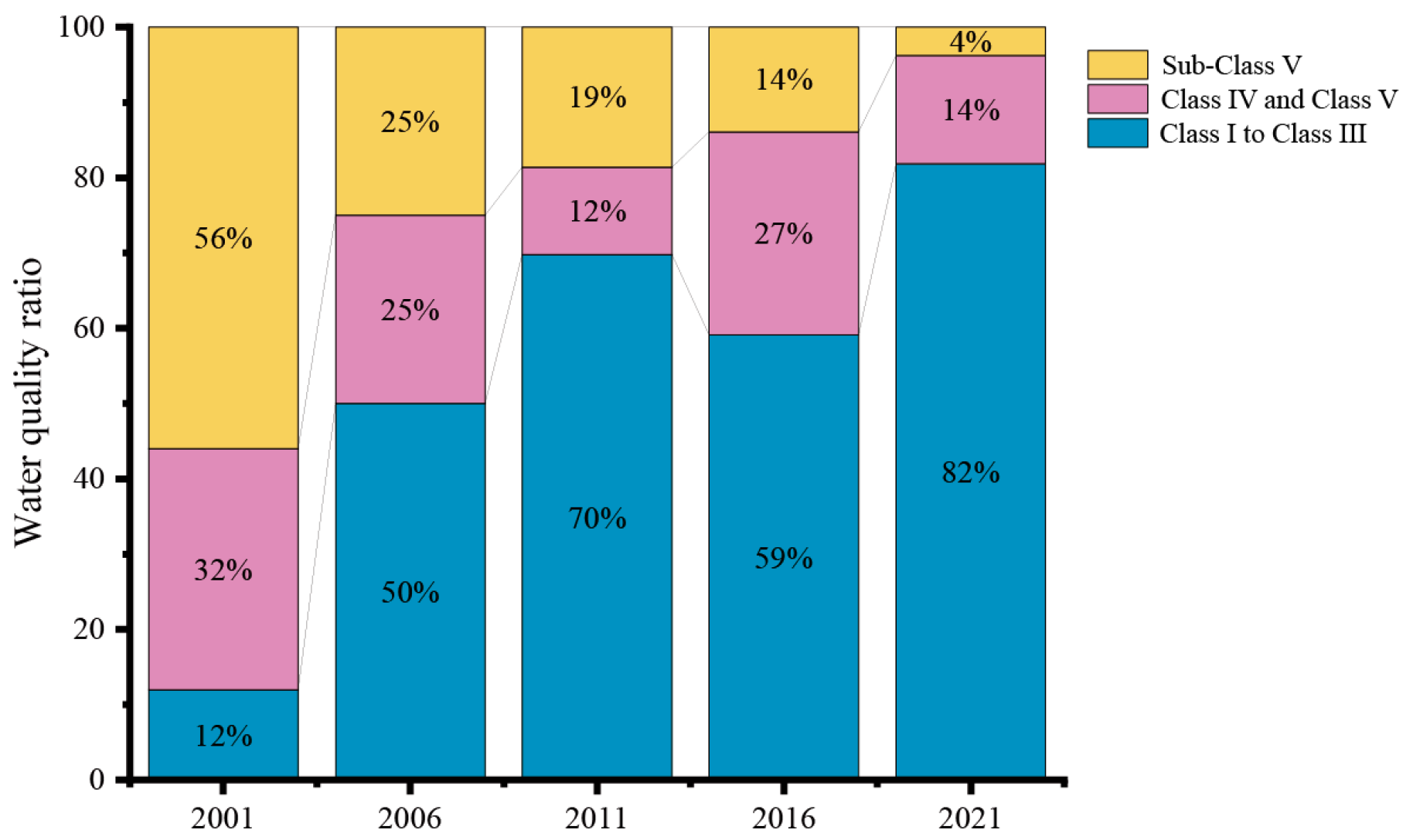

3.3. Historical Characteristics of Water Quality Changes in the Yellow River Basin

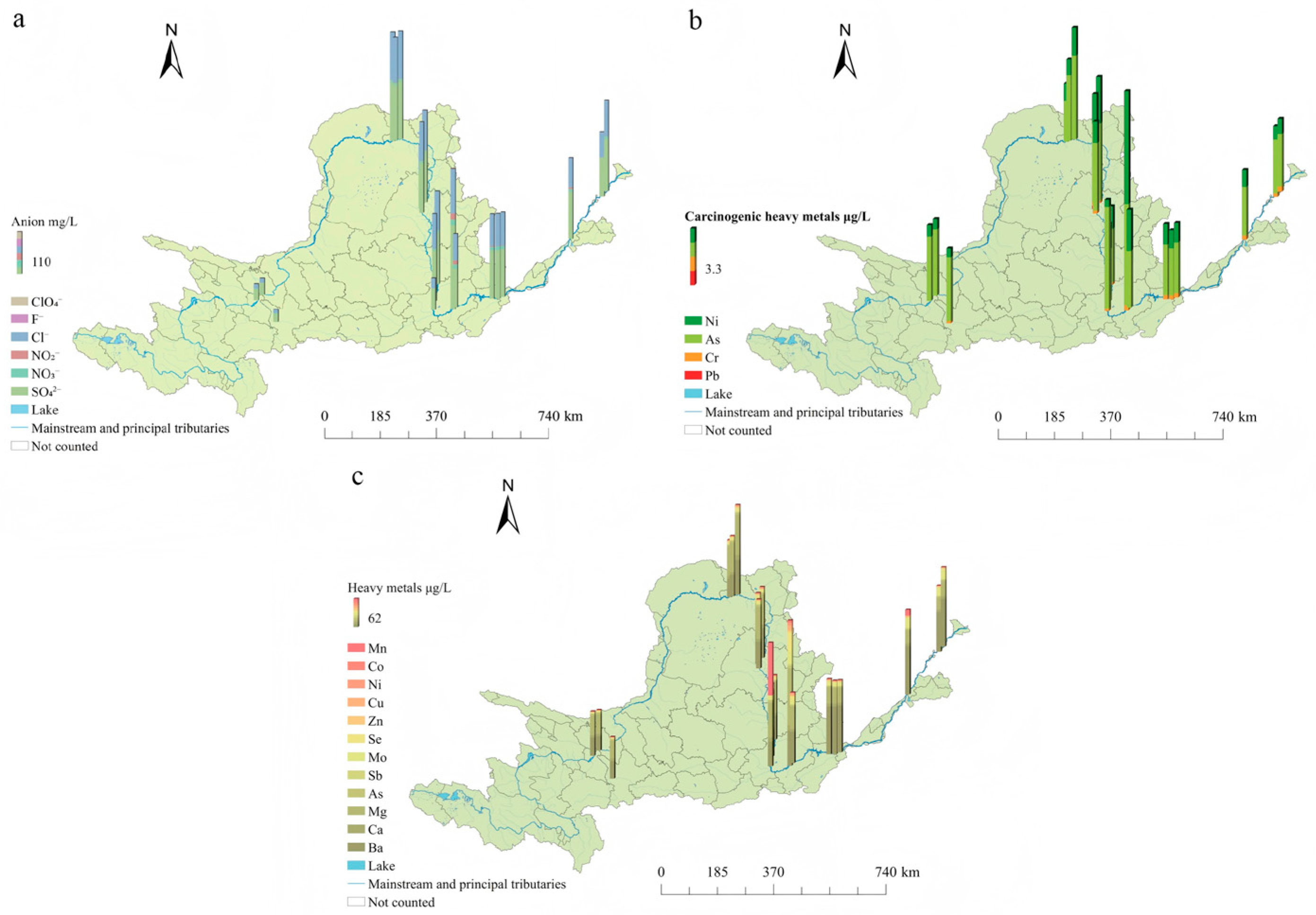

3.4. Current Distribution Status and Pollution Characteristics of Anions and Heavy Metals in Water Bodies at Cross-Sections Along the Main Course of the Yellow River

4. Discussion

4.1. Historical Characteristics of Industrial Structure Changes in the Yellow River Basin and Their Impact on the Water Environment

4.2. Spatial Characteristics of Industrial Structure Changes in the Yellow River Basin and Their Impact on the Water Environment

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, G.G.; Liu, S.L. Is technological innovation the effective way to achieve the “double dividend” of environmental protection industrial upgrading? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 18541–18556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.J.; Ma, C.B.; Xie, R. Structural Innovation Efficiency Effects of Environmental Regulation: Evidence from China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Pilot. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 75, 741–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-P.; Fu, B.-J.; Wang, K.-B.; Zhao, M.M.; Ma, J.-F.; Wu, J.-H.; Xu, C.; Liu, W.-G.; Wang, H. Sustainable development in the Yellow River Basin: Issues strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, H.R. Economic growth industrial structure nitrogen oxide emissions reduction prediction in China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, H.; Chang, M. Exploring the complex relationship between industrial upgrading energy eco-efficiency in river basin cities: Acase study of the Yellow River Basin in China. Energy 2024, 312, 133498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.S.; Li, W. Review on the connotation Evaluation Path of Industrial High Quality Development in the Yellow River Basin. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Renewable Energy Environmental Protection (ICREEP), Shenzhen, China, 23–25 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk, M.; Yuksel, Y.E. Energy structure of Turkey for sustainable development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.X. Dwindling regional environmental pollution through industrial structure adjustment higher education development. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Z.N. Analysis of Water Resources Stress Its Driving Factors of the Yelow River Basin. Yellow River 2022, 44, 77–83, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Tao, W.; Shen, Z. Improving high-quality development with environmental regulation industrial structure in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; An, W.; Shi, Y.L.; Yang, M. Perchlorate occurrence sub-basin contribution risk hotspots for drinking water sources in China based on industrial agglomeration method. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.M.; Ma, W.R.; Chen, Q.W. Does Regional Development Policy Promote Industrial Structure Upgrading? Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB3838-2002; Environmental quality standards for surface water. State Environmental Protection Administration: Beijing, China, 2002.

- GB5749-2022; Standard for drinking water quality. State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Wang, G.; Sun, X. Resource endowment industrial structure green development of the Yellow River Basin. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zuo, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Z. Evaluation prediction of the level of high-quality development: Acase study of the Yellow River Basin China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuan, J. Research on ecological quality restoration of fragile mining areas in the Yellow River Basin—The case of Xiegou coal mine. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 174, 113426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, X.; Lei, H. Analysis of the spatial association network structure of water-intensive utilization efficiency its driving factors in the Yellow River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 158, 111400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, Q.; Cai, Y. Optimizing the industrial structure of a watershed in association with economic–environmental consideration: An inexact fuzzy multi-objective programming model. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 42, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Duan, Q.; Huang, L.; Bi, J. Areview of soil heavy metal pollution from industrial agricultural regions in China: Pollution risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Sun, H.; Peng, T.; Ding, W.; Liu, B.; Liu, Q. Comprehensive evaluation of environmental availability pollution level leaching heavy metals behavior in non-ferrous metal tailings. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Guo, Z.; Gao, C.; You, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, T. Mechanisms pollution characteristics of heavy metal flow in China’s non-ferrous metal industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 515, 145791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.Y.; Pang, Q.H.; Zhang, L.N.; Zhou, W.M. Coupling Path Identification Spatial Governance of Advanced Industrial Structure Ecological Efficiency in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2021, 41, 116–125, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Peng, C.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Xiao, X. Heavy metals in soils around non-ferrous smelteries in China: Status health risks control measures. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 282, 117038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhang, L. Coupling Coordination Situation Driving Factors of Social Economy Eco-environment in Yellow River Basin. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 41, 240–249. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.M.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, H.M.; Li, D.; Duan, Y.; Han, Z. Research on the spatial correlation drivers of industrial agglomeration pollution discharge in the Yellow River Basin. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1004343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Shao, Y.S. Impact Mechanisms of Carbon Emissions Industrial Structure Environmental Regulations in the Yellow River Basin. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2022, 31, 5693–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.K.; Chen, K.H.; Wang, Q.J.; Zhang, Y.J.; Qu, X.H.; Zhang, M.F.; Ma, H.T. Current Status Challenges Policy Recommendations for Industrial Development in the Yellow River Basin. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2024, 39, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, F.J.; Miao, C.H.; Hu, Z.Q. Industrial Structural Transformation in the Yellow River Basin Its Response to Spatial Agglomeration Patterns. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Li, T.S.; Zhai, Z.Y. Spatial-temporal differentiation of high-quality industrial development level in the Yellow River Basin based on ecological total factor productivity. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, R.; Yan, H. System-dynamics modeling for exploring the impact of industrial-structure adjustment on the water quality of the river network in the Yangtze Delta Area. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, H.S.; Opulencia, M.J.C.; Afra, A.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Abdullaev, D.; Majdi, A.; Taherian, M.; Ekrami, H.A.; Mohammadi, M.J. Source toxicity carcinogenic health risk assessment of heavy metals. Rev. Environ. Health 2024, 39, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Amaya, E.; Gil, F.; Murcia, M.; Llop, S.; Casas, M.; Vrijheid, M.; Lertxundi, A.; Irizar, A.; Fernández-Tardón, G.; et al. Placental metal concentrations birth outcomes: The Environment Childhood (INMA) project. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Liu, R.; Dietrich, K.N.; Reponen, T.; Xie, C.; Sucharew, H.; Huo, X.; et al. Birth outcomes associated with maternal exposure to metals from informal electronic waste recycling in Guiyu China. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Bobb, J.F.; Claus Henn, B.; Gennings, C.; Schnaas, L.; Tellez-Rojo, M.; Bellinger, D.; Arora, M.; Wright, R.O.; Coull, B.A. Bayesian varying coefficient kernel machine regression to assess neurodevelopmental trajectories associated with exposure to complex mixtures. Stat. Med. 2018, 37, 4680–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wu, X.; Mao, G.; Zhao, T.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, L.; Wu, X. Neurological effects of subchronic exposure to dioctyl phthalate (DOP), lead, and arsenic, individual mixtures in immature mice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 9247–9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.; Maurya, S.K.; Khare, P.; Srivastava, A.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Characterization of Developmental Neurotoxicity of As Cd Pb Mixture: Synergistic Action of Metal Mixture in Glial Neuronal Functions. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 118, 586–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Xie, J.; Zhang, S.; Yin, G.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bo, D.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Feng, C.; et al. Lead cadmium arsenic mercury combined exposure disrupted synaptic homeostasis through activating the Snk-SPARpathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 163, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, P.; Saravanan, V.; Rajeshkannan, R.; Arnica, G.; Rajasimman, M.; Baskar, G.; Pugazhendhi, A. Comprehensive review on toxic heavy metals in the aquatic system: Sources identification treatment strategies health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy metals: Toxicity human health effects. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaynab, M.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Ameen, A.; Sharif, Y.; Ali, L.; Fatima, M.; Khan, K.A.; Li, S. Health environmental effects of heavy metals. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Xiao, B.H.; Ali, M.U.; Xiao, P.; Zhao, P.; Wang, H.; Bibi, S. Heavy metals pollution from smelting activities: Athreat to soil groundwater. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 274, 116189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Wang, T.; Liu, L.L.; Bai, L. AStudy on the Spatiotemporal Patterns of Industrial Wastewater Pollutant Discharges in the Liao River Basin. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2010, 19, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.X.; Feng, C.D. Research on the Measurement of High-quality Development of Resource-based Cities in the Yellow River Basin. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 37, 20–26, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Li, L. Efficiency evaluation policy analysis of industrial wastewater control in China. Energies 2017, 10, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Output Value Unit: % | 1 | 1.020 | 1.027 | 1.053 | 1.127 | 1.171 | 1.217 | 1.362 | 1.644 | 1.981 | 2.550 |

| year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Nominal Output Value Unit: % | 2.756 | 3.048 | 3.444 | 3.936 | 4.493 | 4.557 | 4.816 | 5.269 | 5.838 | 6.501 | 6.797 |

| 2000 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper–middle reaches | 0.832 | 0.819 | 0.699 | 0.825 | 0.761 | 0.762 | 0.799 | 0.919 | 1.188 | 1.345 | 1.511 | 1.203 |

| Middle reaches | 0.841 | 0.794 | 0.641 | 0.683 | 0.582 | 0.663 | 0.649 | 0.770 | 1.014 | 1.081 | 1.160 | 0.829 |

| Middle–lower reaches | 0.690 | 0.700 | 0.577 | 0.560 | 0.555 | 0.608 | 0.687 | 0.833 | 0.961 | 1.071 | 1.280 | 1.260 |

| Sampling Points | City | F− | NO2− | NO3− | Se |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M5 | Baotou City | — | 1.46 | — | — |

| M6 | Baotou City | — | 1.20 | — | — |

| M13 | Sanmenxia City | 1.09 | 15.09 | 14.87 | 0.04 |

| M14 | Sanmenxia City | — | 9.50 | 10.56 | — |

| M15 | Luoyang City | — | 3.54 | — | — |

| M16 | Luoyang City | — | 1.49 | — | — |

| M17 | Gongyi City | — | 1.31 | — | — |

| M18 | Taian City | — | 3.97 | — | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Q.; Wang, K.; Bing, X.; Jiang, J.; He, S.; Song, Q.; Cui, F.; Zhu, Y. Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Industrial Structure in the Yellow River Basin, China, and Its Impact on the Water Environment. Water 2025, 17, 3326. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223326

Zhou Q, Wang K, Bing X, Jiang J, He S, Song Q, Cui F, Zhu Y. Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Industrial Structure in the Yellow River Basin, China, and Its Impact on the Water Environment. Water. 2025; 17(22):3326. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223326

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Qihao, Kuo Wang, Xiaojie Bing, Juan Jiang, Sailan He, Qingshuai Song, Fangxi Cui, and Yuanrong Zhu. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Industrial Structure in the Yellow River Basin, China, and Its Impact on the Water Environment" Water 17, no. 22: 3326. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223326

APA StyleZhou, Q., Wang, K., Bing, X., Jiang, J., He, S., Song, Q., Cui, F., & Zhu, Y. (2025). Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Industrial Structure in the Yellow River Basin, China, and Its Impact on the Water Environment. Water, 17(22), 3326. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223326