Permeable Pavements: An Integrative Review of Technical and Environmental Contributions to Sustainable Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

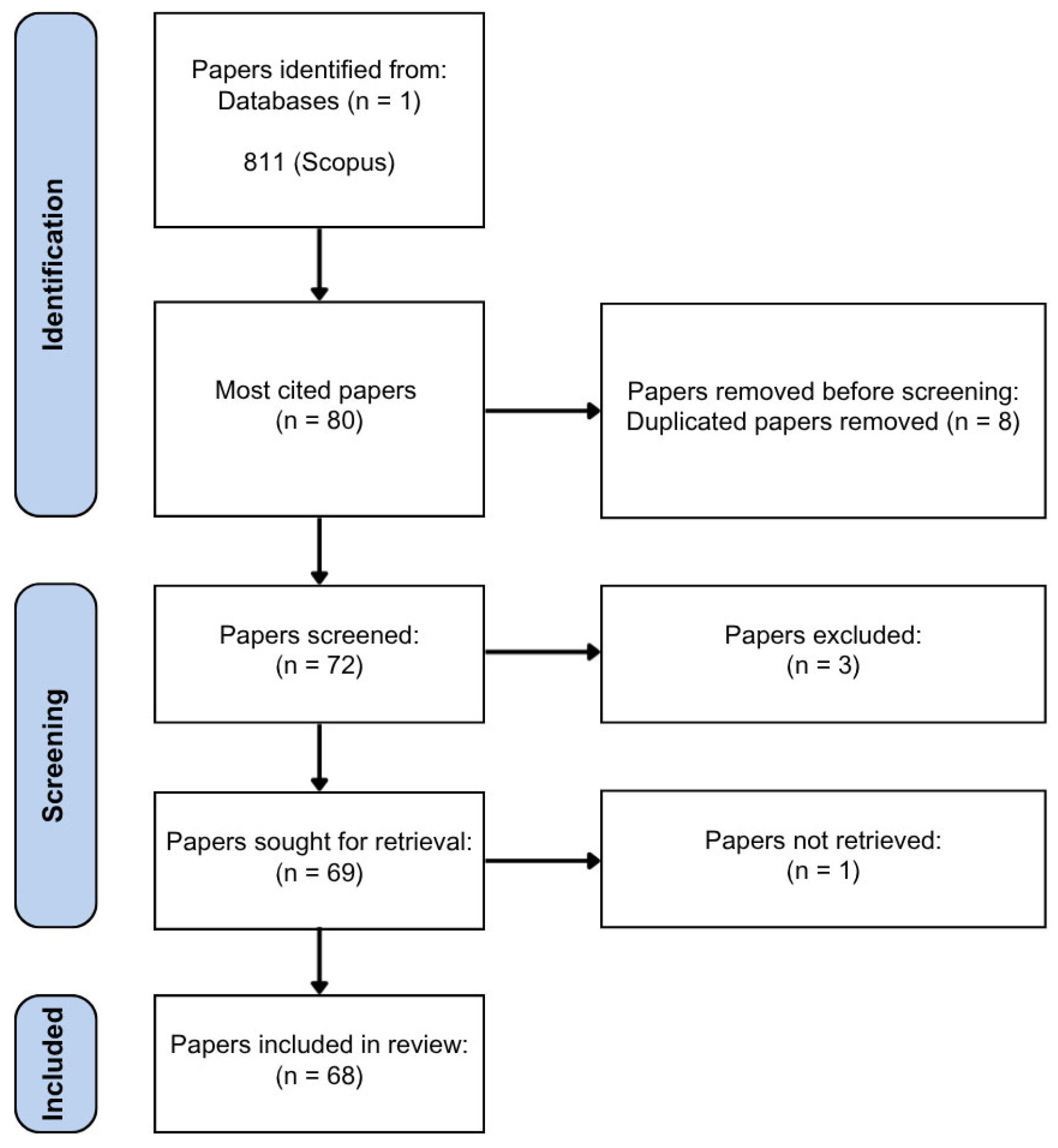

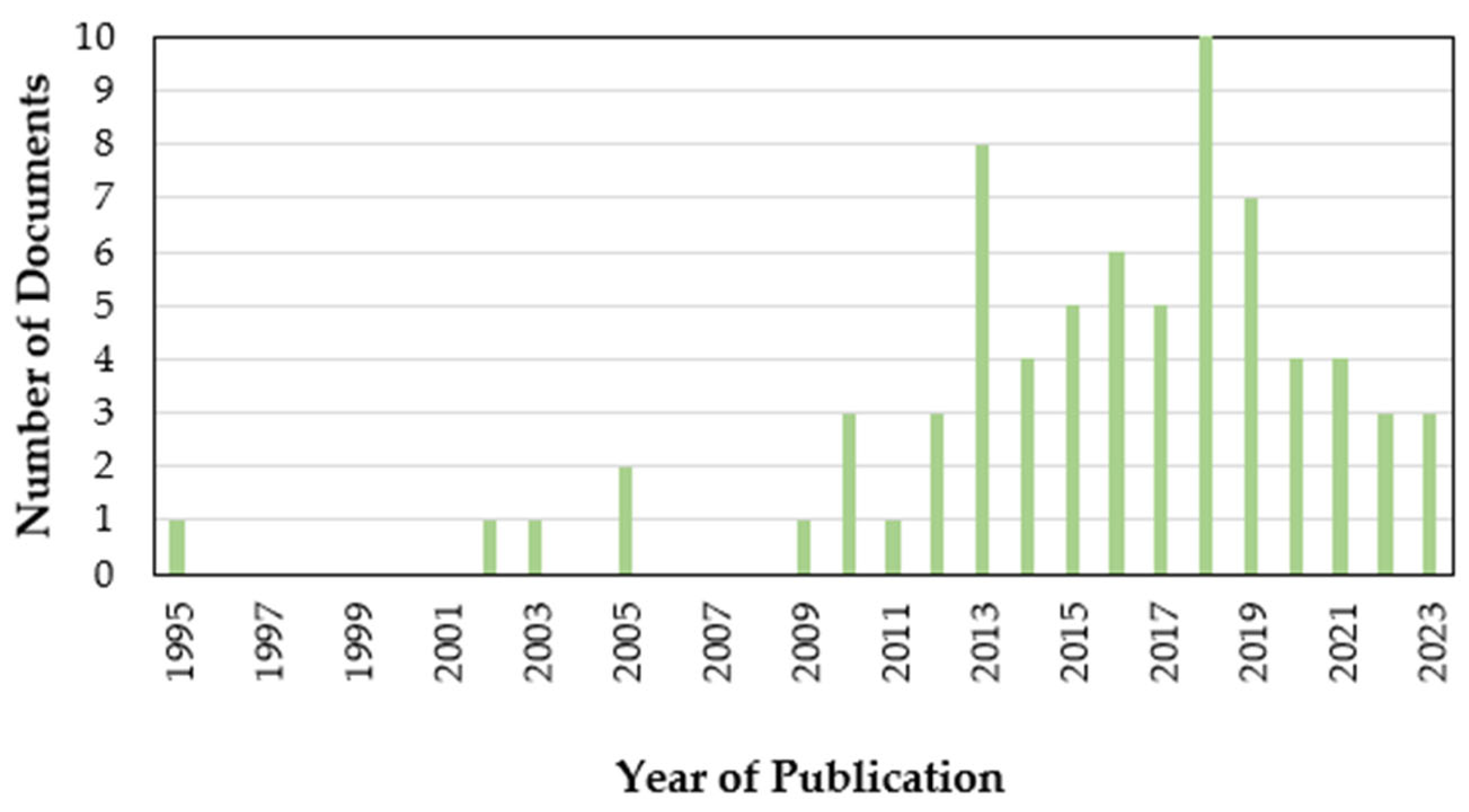

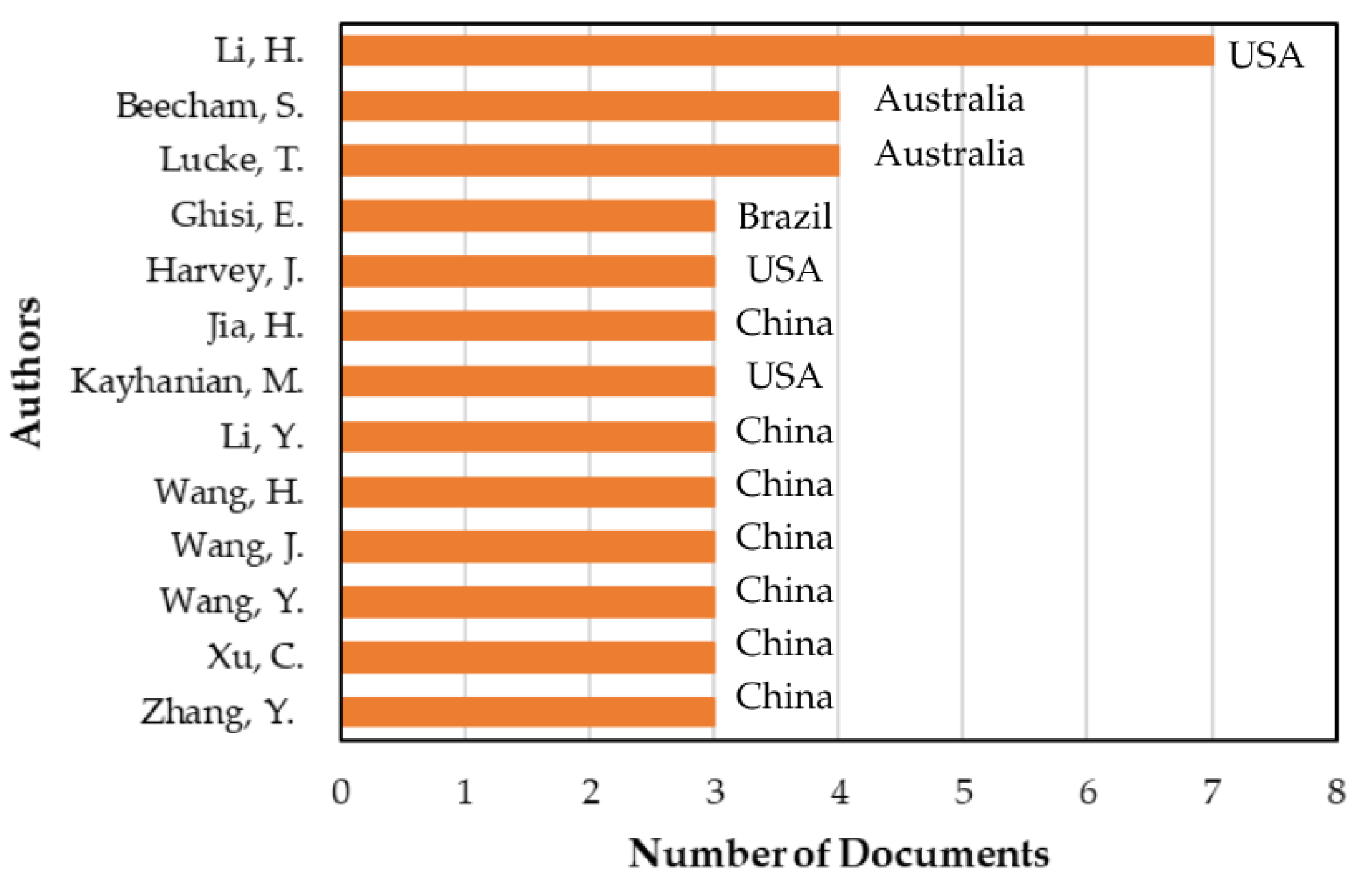

2. Methodology

2.1. Type of Study and Methodological Procedures

2.2. Database

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection and Eligibility Criteria

- Life cycle assessment (LCA);

- Infiltration capacity and pollutant retention;

- Influence on urban heat islands and flooding in urban areas;

- Impact of the climate and the clogging effect on the efficiency of pervious pavements.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Life Cycle Assessment

3.2. Infiltration Capacity and Pollutant Retention

3.2.1. Infiltration

3.2.2. Pollutant Retention

3.3. Influence on Urban Heat Islands and Flooding

3.3.1. Urban Heat Island Mitigation

3.3.2. Urban Flood Mitigation

3.4. Impact of Climate and Clogging on the Efficiency of Pervious Pavements

3.4.1. Impact of Climate

3.4.2. Impact of Clogging

3.5. Gaps and Recommendations for Future Research

3.5.1. Research Gaps

- Methodological Standardisation: A significant heterogeneity exists in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies, particularly regarding the functional units, system boundaries, and environmental impact categories considered. This lack of standardisation makes it difficult to compare results across studies and draw generalised conclusions. Future research should aim to harmonise methodologies to improve the comparability and reliability of LCA outcomes.

- Pollutant Treatment Efficiency: While permeable pavements show high efficiency in removing total suspended solids (TSS) and phosphorus, their capacity to reduce nitrogen-based compounds is limited. This indicates a need for studies focusing on innovative materials or complementary treatment layers to improve nitrogen retention, particularly for urban areas with high nutrient loads.

- Climatic and Environmental Resilience: Few studies address the long-term performance of permeable pavements under varying climatic conditions, including freeze–thaw cycles, extreme rainfall events, and prolonged dry periods. Research is needed to optimise material compositions, layer structures, and drainage designs to enhance durability and hydraulic performance under site-specific conditions.

- Material Innovation: The use of recycled and alternative materials for pavement layers is still emerging. More systematic investigations are required to evaluate long-term environmental benefits, pollutant retention, structural performance, and potential trade-offs associated with their use.

3.5.2. Implementation Gaps

- Economic Barriers: High initial construction costs remain a significant obstacle for widespread adoption, particularly in developing regions. Cost–benefit analyses considering long-term environmental and societal benefits could support broader implementation.

- Maintenance Challenges: Clogging is the main factor compromising infiltration and system performance. Despite the importance of maintenance, there is limited research on cost-effective, environmentally safe, and practical rejuvenation techniques that can be routinely applied in urban areas.

- Integration with Urban Infrastructure: While the benefits of permeable pavements are well-documented, their integration with existing stormwater management systems, urban heat island mitigation strategies, and green infrastructure networks is not fully explored. Design frameworks and guidelines are needed to support planners and engineers in implementing these systems effectively.

3.5.3. Climate Change and Permeable Pavements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN (United Nations). The World at Six Billion; UN: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund). State of World Population 2023: 8 Billion Lives, Infinite Possibilities the Case for Rights and Choices; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UN (United Nations). Global Population Growth and Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IWMI (International Water Management Institute). Water for Food Water for Life: A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture; Earthscan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UN (United Nations). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2018: Nature-Based Solutions for Water; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- NRC (National Research Council). Urban Stormwater Management in the United States; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wheater, H.; Evans, E. Land use, water management and future flood risk. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO (World Meteorological Organization). Integrated Flood Management Tools Series: Urban Flood Management in Changing Climate; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gartland, L. Heat Islands: Understanding and Mitigating Heat in Urban Areas; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hammes, G.; Thives, L.; Ghisi, E. Application of stormwater collected from porous asphalt pavements for non-potable uses in buildings. Environ. Manag. 2018, 222, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIRIA. The Sustainable Drainage Systems (SUDS) Manual; Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA): UK, London, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, T.D.; Shuster, W.; Hunt, W.F.; Ashley, R.; Butler, D.; Arthur, S.; Trowsdale, S.; Barraud, S.; Semadeni-Davies, A.; Bertrand-Krajewski, J.L.; et al. SUDS, LID, BMPs, WSUD and More—The Evolution and Application of Terminology Surrounding Urban Drainage. Urban Water J. 2015, 12, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Grabowiecki, P. Review of Permeable Pavement Systems. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3830–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of State Highways and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). AASHTO Guide for Design of Pavement Structures; AASHTO: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-1-56051-055-0. [Google Scholar]

- EPA NPDES: Stormwater Best Management Practice, Permeable Pavements. Permeable Pavements. 2021; APC. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-11/bmp-permeable-pavements.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- ABNT NBR 16416; Pavimentos Permeáveis de Concreto—Requisitos e Procedimentos. Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015; p. 31. (In Portuguese)

- Collins, K.A.; Hunt, W.F.; Hathaway, J.M. Hydrologic Comparison of Four Types of Permeable Pavement and Standard Asphalt in Eastern North Carolina. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2008, 13, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interpave Guide to the Design, Construction and Maintenance of Concrete Block Permeable Pavements. 2010. Available online: https://www.paving.org.uk/documents/cppave.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Yong, C.F.; McCarthy, D.T.; Deletic, A. Predicting Physical Clogging of Porous and Permeable Pavements. J. Hydrol. 2013, 481, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollok, L.; Spierling, S.; Endres, H.-J.; Grote, U. Social Life Cycle Assessments: A Review on Past Development, Advances and Methodological Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattebo, B.O.; Booth, D.B. Long-Term Stormwater Quantity and Quality Performance of Permeable Pavement Systems. Water Res. 2003, 37, 4369–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Kubilay, A.; Derome, D.; Carmeliet, J. The use of permeable and reflective pavements as a potential strategy for urban heat island mitigation. Urban Clim. 2020, 31, 100534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.O. Desempenho de Pavimentos Permeáveis Como Medida Mitigadora Da Impermeabilização Do Solo Urbano. Ph.D. Thesis, Escola Politécnica da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2011. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, P.; Tucci, C.; Goldenfum, J. Avaliação da eficiência dos pavimentos permeáveis na redução de escoamento superficial. Rev. Bras. De Recur. Hídricos 2000, 5, 21–29. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Elsevier Scopus. Expertly Curated Abstract & Citation Database; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sprouse, C.E.; Hoover, C.; Obritsch, O.; Thomazin, H. Advancing Pervious Pavements through Nomenclature, Standards, and Holistic Green Design. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, H. Life-cycle assessment and multi-criteria performance evaluation of pervious concrete pavement with fly ash. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 177, 105969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Integrated life cycle assessment of permeable pavement: Model development and case study. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 85, 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, L.; Ghisi, E.; Thives, L. Permeable pavements life cycle assessment: A literature review. Water 2018, 10, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, L.; Ghisi, E.; Severis, R. Environmental assessment of a permeable pavement system used to harvest stormwater for non-potable water uses in a building. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 141087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Oeser, M. The environmental impact evaluation on the application of permeable pavement based on life cycle analysis. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.; Bradford, A.; Abbassi, B. Cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment (LCA) of low-impact-development (LID) technologies in southern Ontario. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi, A.; Coupe, S. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and life cycle costing (LCC) of road drainage systems for sustainability evaluation: Quantifying the contribution of different life cycle phases. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, C.; Yin, D.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y.; Jia, H. Environmental and economic cost-benefit comparison of sponge city construction in different urban functional regions. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiolo, M.; Carini, M.; Capano, G.; Piro, P. Synthetic sustainability index (SSI) based on life cycle assessment approach of low impact development in the Mediterranean area. Cogent Eng. 2017, 4, 1410272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Kaloush, K.; Shacat, J. Cool pavements for urban heat island mitigation: A synthetic review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Chui, T. Evaluating the life cycle net benefit of low impact development in a city. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Abdelhady, A.; Harvey, J. Initial evaluation methodology and case studies for life cycle impact of permeability of permeable pavements. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 7, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Rao, Q.; Li, J.; Keat Tan, S. Optimization of integrating life cycle cost and systematic resilience for grey-green stormwater infrastructure. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 90, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S.; Farioli, F.; Zamagni, A. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment in the Context of Sustainability Science Progress (Part 2). Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinée, J.B.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Zamagni, A.; Masoni, P.; Buonamici, R.; Ekvall, T.; Rydberg, T. Life Cycle Assessment: Past, Present, and Future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R.; Johnson, G.T.; Steyn, D.G.; Watson, I.D. Simulation of Surface Urban Heat Islands under ‘Ideal’ Conditions at Night Part 2: Diagnosis of Causation. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1991, 56, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, R.A.; Leung, D.Y.C. On the Heating Environment in Street Canyon. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2011, 11, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valinski, N.A.; Chandler, D.G. Infiltration performance of engineered surfaces commonly used for distributed stormwater management. Environ. Manag. 2015, 160, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Imteaz, M.A.; Arulrajah, A.; Piratheepan, J.; Disfani, M.M. Recycled construction and demolition materials in permeable pavement systems: Geotechnical and hydraulic characteristics. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, F.; Lucke, T.; Beecham, S. Effect of age of permeable pavements on their infiltration function. Clean-Soil Air Water 2014, 42, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, M.; Kakuturu, S.; Ballock, C.; Spence, J.; Wanielista, M. Effect of rejuvenation methods on the infiltration rates of pervious concrete pavements. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2010, 15, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierkes, C.; Kuhlmann, L.; Kandasamy, J.; Angelis, G. Pollution retention capability and maintenance of permeable pavements. Glob. Solut. Urban Drain. 2002, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Valeo, C.; He, J.; Chu, A. Three types of permeable pavements in cold climates: Hydraulic and environmental performance. J. Environ. Eng. 2016, 142, 04016025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Valeri, V.C.; Marchioni, M.; Sañudo-Fontaneda, L.A.; Giustozzi, F.; Becciu, G. Laboratory assessment of the infiltration capacity reduction in clogged porous mixture surfaces. Sustainability 2016, 8, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, F.; Lucke, T.; van de Giesen, N.; van de Ven, F. Evaluating the infiltration performance of eight dutch permeable pavements using a new full-scale infiltration testing method. Water 2014, 6, 2070–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghmanesh, M.; Beecham, S. A review of permeable pavement clogging investigations and recommended maintenance regimes. Water 2018, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseen, R.M.; Ballestero, T.P.; Houle, J.J.; Briggs, J.F.; Houle, K.M. Water quality and hydrologic performance of a porous asphalt pavement as a storm-water treatment strategy in a cold climate. J. Environ. Eng. 2012, 138, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugin, M.; Marchioni, M.; Becciu, G.; Giustozzi, F.; Toraldo, E.; Andrés-Valeri, V.C. Clogging potential evaluation of porous mixture surfaces used in permeable pavement systems. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Hernandez, J.; Castro-Fresno, D.; Fernández-Barrera, A.H.; Vega-Zamanillo, Á. Characterization of Infiltration Capacity of Permeable Pavements with Porous Asphalt Surface Using Cantabrian Fixed Infiltrometer. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2012, 17, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruppu, U.; Rahman, A.; Rahman, M.A. Permeable pavement as a stormwater best management practice: A review and discussion. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Delkash, M.; Tajrishy, M. Evaluation of permeable pavement responses to urban surface runoff. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 187, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Meng, Q.; Tan, K.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Experimental investigation on the influence of evaporative cooling of permeable pavements on outdoor thermal environment. Build. Environ. 2018, 140, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; He, Y.; Hiller, J.E.; Mei, G. A new water-retaining paver block for reducing runoff and cooling pavement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Wang, J.; Xiao, F. Sponge city strategy and application of pavement materials in sponge city. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 127022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Using cool pavements as a mitigation strategy to fight urban heat island—A review of the actual developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y. A review on the development of cool pavements to mitigate urban heat island effect. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempihar, J.; Pourshams-Manzouri, T.; Kaloush, K.; Rodezno, M. Porous asphalt pavement temperature effects for urban heat Island analysis. Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 1, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidimitriou, A.; Yannas, S. Street Canyon Design and Improvement Potential for Urban Open Spaces; the Influence of Canyon Aspect Ratio and Orientation on Microclimate and Outdoor Comfort. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 33, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz-Gäal, L.P.; Pezzuto, C.C.; de Carvalho, M.F.H.; Mota, L.T.M. Urban Geometry and the Microclimate of Street Canyons in Tropical Climate. Build. Environ. 2020, 169, 106547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimimoshaver, M.; Khalvandi, R.; Khalvandi, M. The Effect of Urban Morphology on Heat Accumulation in Urban Street Canyons and Mitigation Approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 73, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husni, E.; Prayoga, G.A.; Tamba, J.D.; Retnowati, Y.; Fauzandi, F.I.; Yusuf, R.; Yahya, B.N. Microclimate Investigation of Vehicular Traffic on the Urban Heat Island through IoT-Based Device. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremeac, B.; Bousquet, P.; de Munck, C.; Pigeon, G.; Masson, V.; Marchadier, C.; Merchat, M.; Poeuf, P.; Meunier, F. Influence of Air Conditioning Management on Heat Island in Paris Air Street Temperatures. Appl. Energy 2012, 95, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.K. Porous Pavements in North America: Experience and Importance Revêtements Poreux En Amérique Du Nord: Expérience et Importance. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Sustainable Techniques and Strategies for Urban Water Management, Lyon, France, 27 June–1 July 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Boogaard, F.; Lucke, T. Long-Term Infiltration Performance Evaluation of Dutch Permeable Pavements Using the Full-Scale Infiltration Method. Water 2019, 11, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Fabender, S.; Wang, D.; Oeser, M. Development of a sustainable pervious pavement material using recycled ceramic aggregate and bio-based polyurethane binder. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Harvey, J.T.; Holland, T.J.; Kayhanian, M. The use of reflective and permeable pavements as a potential practice for heat island mitigation and stormwater management. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 015023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, G.; Šimůnek, J.; Piro, P. A comprehensive numerical analysis of the hydraulic behavior of a permeable pavement. J. Hydrol. 2016, 540, 1146–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Ding, X.; Shao, W. Integrated assessments of green infrastructure for flood mitigation to support robust decision-making for sponge city construction in an urbanized watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Wang, X.C.; Ren, N.; Li, G.; Ding, J.; Liang, H. Implementation of a specific urban water management—Sponge City. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaram, C.; Giacomoni, M.H.; Prakash Khedun, C.; Holmes, H.; Ryan, A.; Saour, W.; Zechman, E.M. Simulation of combined best management practices and low impact development for sustainable stormwater management. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2010, 46, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullaney, J.; Lucke, T. Practical review of pervious pavement designs. Clean-Soil Air Water 2014, 42, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lawluvy, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yap, P. Low Impact Development (LID) practices: A review on recent developments, challenges and prospects. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adresi, M.; Yamani, A.; Karimaei Tabarestani, M.; Rooholamini, H. A comprehensive review on pervious concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 407, 133308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Kayhanian, M.; Harvey, J.T. Comparative field permeability measurement of permeable pavements using ASTM C1701 and NCAT permeameter methods. Environ. Manag. 2013, 118, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kozak, J.; Hundal, L.; Cox, A.; Zhang, H.; Granato, T. In-situ infiltration performance of different permeable pavements in a employee used parking lot—A four-year study. Environ. Manag. 2016, 167, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, C.L.; Comino-Mateos, L. In-situ hydraulic performance of a permeable pavement sustainable urban drainage system. Water Environ. J. 2003, 17, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Volume 18, pp. 433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Nazeri Tahroudi, M. Comprehensive Global Assessment of Precipitation Trend and Pattern Variability Considering Their Distribution Dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Life Cycle Stage | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Raw material acquisition/Production | Extraction and processing of constituent materials (aggregates, cement, asphalt, etc.) | [27,28] |

| Transport | Transport of materials to the construction site | [28,29] |

| Construction/Implementation | Pavement installation | [28,30] |

| Use | Performance during use, including interaction with vehicles and the environment | [28,29,31] |

| Maintenance and rehabilitation | Activities related to the repair, cleaning, and refurbishment of the pavement | [28] |

| End of life/Disposal | Demolition and disposal or recycling of pavement materials | [27,29,30] |

| Method for Measuring Infiltration Capacity | Papers That Use the Method | |

|---|---|---|

| References | Percentage | |

| Single and double ring infiltrometers | [46,47,49,51,53] | 50% |

| Permeameter | [50,54] | 20% |

| Drip-infiltrometer | [48] | 10% |

| Cantabrian fixed infiltrometer | [55] | 10% |

| Automated mini disc infiltrometer | [44] | 10% |

| Paper | Infiltration Capacity (mm/h) | Local | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porous Asphalt | Porous Concrete | ||

| Valinski and Chandler [44] | 192.00 | 145.80 | Syracuse, NY, USA |

| Huang et al. [49] | 43.767 | 112.886 | Calgary, AB, Canada |

| Roseen et al. [53] | 14.90–26.90 | - | Durham, NH, USA |

| Paper | Permeable Pavement Material Type | Removal Efficiency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSS | TN | TP | ||

| Rahman et al. [45] | Recycled concrete aggregate | 87.0 | 37.4 | 40.4 |

| Crushed brick | 90.00 | 40.0 | 51.1 | |

| Reclaimed asphalt pavement | 83.4 | 61.8 | 70.2 | |

| Huang et al. [49] | Porous asphalt | 89.6–93.2 | 19.4–37.6 | 74.6–84.4 |

| Porous concrete | 90.6–94.6 | 15.0–34.2 | 75.0–84.0 | |

| Permeable interlocking pavers | 86.9–94.3 | 2.9–40.0 | 74.9–81.9 | |

| Hammes et al. [10] | Porous asphalt with a sand layer | 92.0 | - | 23.0 |

| Porous asphalt without a sand layer | 83.0 | - | 58.0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franco, E.; Ghisi, E.; Vaz, I.C.M.; Thives, L.P. Permeable Pavements: An Integrative Review of Technical and Environmental Contributions to Sustainable Cities. Water 2025, 17, 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223323

Franco E, Ghisi E, Vaz ICM, Thives LP. Permeable Pavements: An Integrative Review of Technical and Environmental Contributions to Sustainable Cities. Water. 2025; 17(22):3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223323

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranco, Eric, Enedir Ghisi, Igor Catão Martins Vaz, and Liseane Padilha Thives. 2025. "Permeable Pavements: An Integrative Review of Technical and Environmental Contributions to Sustainable Cities" Water 17, no. 22: 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223323

APA StyleFranco, E., Ghisi, E., Vaz, I. C. M., & Thives, L. P. (2025). Permeable Pavements: An Integrative Review of Technical and Environmental Contributions to Sustainable Cities. Water, 17(22), 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223323